CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Therapeutic Development

This article provides a detailed overview of the current landscape of CRISPR-Cas9 delivery systems, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a detailed overview of the current landscape of CRISPR-Cas9 delivery systems, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of CRISPR cargo and cellular uptake, explores viral and non-viral delivery methodologies with clinical applications, addresses key challenges in efficiency and safety with troubleshooting strategies, and presents comparative data from recent studies to validate method selection. The scope extends from basic mechanisms to advanced innovations and clinical trial updates, offering a practical framework for optimizing delivery strategies in both research and therapeutic contexts.

The Building Blocks: Understanding CRISPR-Cas9 Cargo and Cellular Entry

The CRISPR-Cas9 system requires the delivery of two key components into the nucleus of a target cell: the Cas nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA). The format in which these components are delivered—collectively referred to as the "cargo"—significantly influences the efficiency, specificity, and safety of genome editing. The three primary cargo options are DNA, mRNA, and the pre-assembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex [1] [2]. The choice of cargo is inextricably linked to the selection of a delivery method and directly impacts critical experimental outcomes, including editing efficiency, off-target effects, and cellular toxicity. This application note provides a comparative analysis of these three cargo formats and details standardized protocols for their use in CRISPR research.

Comparative Analysis of Cargo Formats

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of DNA, mRNA, and RNP cargo formats.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of CRISPR-Cas9 Cargo Formats

| Characteristic | DNA (Plasmid) | mRNA | Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cargo Composition | Plasmid encoding Cas9 and gRNA [2] | mRNA for Cas9 translation + separate gRNA [1] | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein + gRNA [1] |

| Mechanism of Action | Requires nuclear entry, transcription, and translation [3] | Requires cytoplasmic translation and nuclear entry [1] | Direct nuclear activity; no transcription/translation needed [4] |

| Onset of Editing Activity | Slow (24-72 hours) [3] | Moderate (12-48 hours) | Very Fast (hours) [4] [3] |

| Editing Efficiency | Variable, can be lower [3] | Moderate to High | Consistently High [4] [3] |

| Off-Target Effects | Higher (prolonged expression) [3] | Moderate | Lower (transient activity) [4] [3] |

| Cytotoxicity | Higher (transfection stress, immune activation) [3] | Moderate (immune activation possible) | Lower [3] |

| Risk of Genomic Integration | Yes (random plasmid integration) [3] | No | No [3] |

| Ease of Use | Simple cloning and production | Requires in vitro transcription | Requires protein purification; simple complexing |

| Ideal Application | Stable cell line generation, long-term expression studies | In vivo delivery via LNPs [5] | Knockouts in primary and sensitive cells, clinical applications [4] |

Detailed Cargo Delivery Protocols

Protocol: Plasmid DNA Transfection via Lipofection

This protocol is suitable for delivering all-in-one CRISPR plasmids to immortalized cell lines (e.g., HEK293T) using lipid-based transfection reagents.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- All-in-one CRISPR Plasmid: A single plasmid vector expressing both Cas9 and the target-specific gRNA [2].

- Lipofection Reagent: A cationic lipid formulation that complexes with DNA to facilitate cellular uptake.

- Opti-MEM Reduced-Serum Medium: Used to dilute the DNA and lipofection reagent.

- Appropriate Cell Culture Media: For maintaining the target cells.

Procedure:

- Day 1: Cell Seeding. Seed an appropriate number of cells into a multi-well plate to achieve 70-90% confluency at the time of transfection (24 hours later).

- Day 2: Transfection Complex Formation.

- Dilute 1-2 µg of the all-in-one CRISPR plasmid in 50-100 µL of Opti-MEM.

- Mix the lipofection reagent gently and dilute the recommended amount (e.g., 2-5 µL) in an equal volume of Opti-MEM (50-100 µL). Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Combine the diluted DNA and diluted lipofection reagent. Mix gently and incubate for 15-20 minutes at room temperature to allow DNA-lipid complexes to form.

- Transfection. Add the complex mixture dropwise to the cells in complete media. Gently swirl the plate to ensure even distribution.

- Day 3: Post-transfection. 4-6 hours after transfection, replace the media with fresh complete media to reduce cytotoxicity.

- Analysis. Analyze editing efficiency 48-72 hours post-transfection via genomic DNA extraction, PCR amplification of the target locus, and sequencing (e.g., T7 Endonuclease I assay or NGS).

Protocol: mRNA and RNP Delivery via Electroporation

Electroporation is highly effective for delivering mRNA and RNP cargoes, especially in hard-to-transfect cells like primary T cells and stem cells [4] [6].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cas9 mRNA + synthetic gRNA OR Pre-complexed Cas9 RNP: For RNP, complex purified Cas9 protein with synthetic gRNA at a molar ratio of 1:1.2 to 1:1.5 and incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes before electroporation [4].

- Electroporation Buffer: A cell-type-specific, low-conductivity buffer.

- Electroporation Cuvettes/Plates: Compatible with the electroporator.

- Pre-warmed Complete Media.

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation. Harvest and wash the target cells (e.g., primary human T cells). Resuspend the cell pellet in the electroporation buffer at a concentration of 1-10 x 10^6 cells/mL.

- Cargo Loading. For a 100 µL reaction, mix 10-20 µg of Cas9 mRNA with 5-10 µg of synthetic gRNA, or the pre-complexed RNP (e.g., 5-20 µM final concentration), with the cell suspension.

- Electroporation.

- Transfer the cell-cargo mixture to an electroporation cuvette.

- Electroporate using a cell-type-optimized waveform (e.g., Square Wave) and parameters. A typical starting condition for T cells is 500V, 2ms, 1 pulse.

- Immediately after the pulse, add pre-warmed media to the cuvette and transfer the cells to a culture plate.

- Recovery and Analysis. Culture the cells and assess viability and editing efficiency after 3-5 days. Editing from RNP can be detected as early as 24 hours post-electroporation.

The workflow and key cellular mechanisms for each cargo format are illustrated below.

Advanced RNP Delivery Strategy

A cutting-edge strategy for RNP delivery involves the use of engineered Extracellular Vesicles (EVs). A 2025 study detailed a modular system for efficient EV-mediated RNP delivery [7].

Mechanism: EV-producing cells (e.g., HEK293T) are engineered to express a fusion protein. This protein consists of:

- MS2 Coat Protein (MCP): An RNA-binding module.

- PhoCl Linker: A UV-light-cleavable protein domain.

- CD63 Transmembrane Domain: A protein that directs the fusion to localize in EVs. Simultaneously, MS2 RNA aptamers are incorporated into the tetraloop and stemloop 2 of the sgRNA. During EV biogenesis, the MCP-fusion protein inside the EV binds with high affinity to the MS2-tagged sgRNA, which is already complexed with Cas9 protein, thereby loading the RNP into the EV [7]. Upon isolation and administration to target cells, exposure to UV light cleaves the PhoCl linker, releasing the RNP complex for efficient genome editing.

Table 2: Key Reagents for EV-Mediated RNP Delivery

| Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| MCP-PhoCl-CD63 Plasmid | Expression vector for the EV-loading fusion protein [7] |

| MS2-Modified sgRNA | sgRNA engineered with MS2 aptamers for high-affinity loading [7] |

| Purified Cas9 Protein | Wild-type or variant Cas9 nuclease |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) | System for efficient EV isolation and concentration [7] |

Concluding Remarks

The selection of CRISPR cargo is a critical determinant of experimental and therapeutic success. DNA plasmids are simple but associated with higher off-target effects and toxicity. mRNA offers a transient profile suitable for in vivo delivery, while RNP complexes provide the highest specificity and efficiency for a wide range of in vitro and ex vivo applications, particularly in clinically relevant primary cells. The ongoing development of advanced delivery platforms, such as engineered extracellular vesicles and optimized lipid nanoparticles, continues to enhance the utility and reach of each cargo format, paving the way for more precise and effective genome editing.

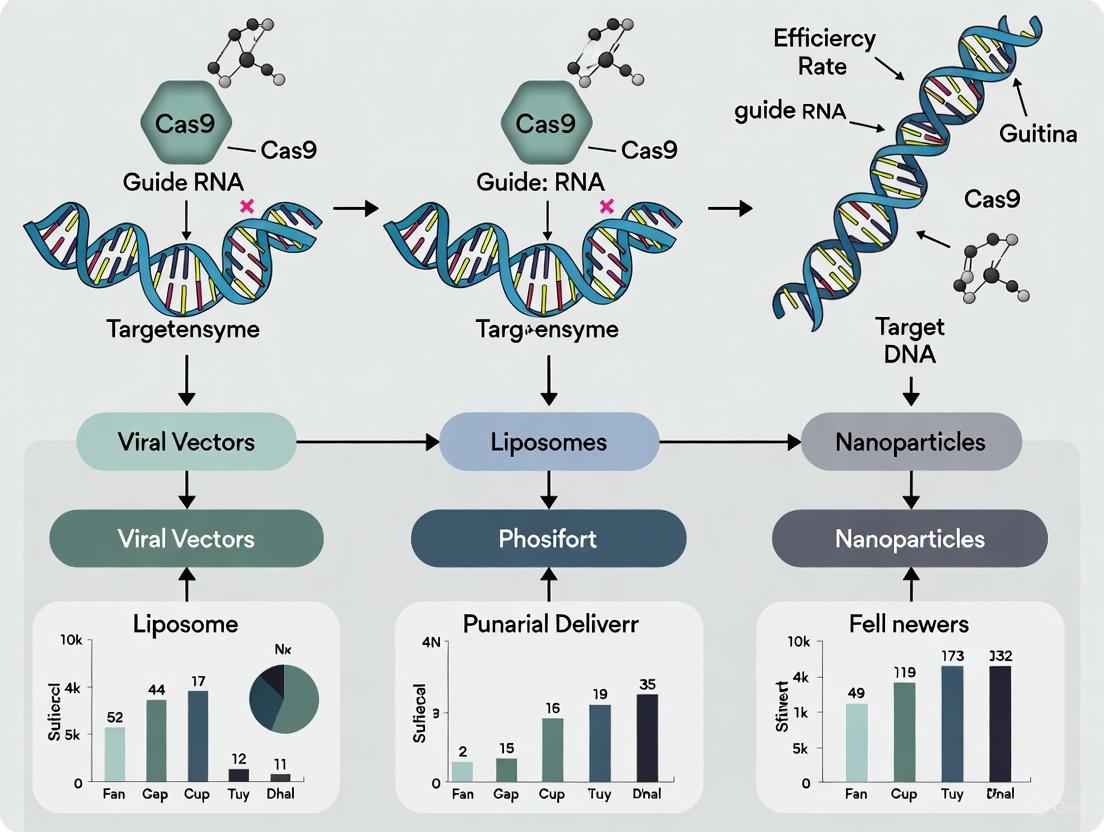

The therapeutic application of the CRISPR-Cas9 system is fundamentally constrained by the challenge of delivering its molecular components into the nucleus of target cells. The efficiency, specificity, and safety of genome editing are directly governed by the cellular uptake mechanisms employed by the delivery vehicle [8] [9]. These vehicles must navigate multiple biological barriers, including the cell membrane, endosomal entrapment, and for non-viral methods, the nuclear envelope, to successfully deliver their cargo [1] [10]. Understanding the distinct entry pathways and intracellular trafficking of these vectors is therefore critical for optimizing CRISPR-based therapies. This application note details the cellular uptake mechanisms of the primary vehicle classes—viral vectors, lipid nanoparticles, and extracellular vesicles—within the context of CRISPR-Cas9 delivery, providing researchers with a mechanistic framework for selection and protocol design.

Vehicle-Specific Uptake Mechanisms and Intracellular Trafficking

The journey of a CRISPR delivery vehicle from the extracellular space to the nucleus involves a series of highly coordinated steps. The initial entry mechanism dictates the subsequent intracellular pathway and ultimately, the editing outcome.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Cellular Uptake and Editing Efficiencies

| Delivery Vehicle | Primary Uptake Mechanism | Editing Efficiency (Reported Ranges) | Key Intracellular Processing Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis [1] | Varies by serotype and target cell; used in multiple clinical trials (e.g., EDIT-101) [11] | Endosomal escape, endosomal acidification triggers conformational change, nuclear import of single-stranded vector genome [1] [11] |

| Lentivirus (LV) | Receptor-mediated endocytosis (e.g., via VSV-G pseudotyping) [12] | High in immune cells; 30-70% transduction efficiency in clinical CAR-T manufacturing [12] | Reverse transcription in the cytoplasm, import of pre-integration complex into the nucleus, integration into host genome [1] [12] |

| Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) | Endocytosis (multiple pathways, including clathrin-mediated) [1] [13] | Efficient in liver; >90% protein reduction in hATTR trial [5] | Endosomal encapsulation, endosomal escape via ionization of lipids, cargo release into the cytoplasm [1] [8] |

| Extracellular Vesicle (EV) | Membrane fusion or endocytosis [7] [9] | Demonstrated efficient endogenous gene editing (e.g., CCR5) [7] | Cargo release into the cytoplasm via fusion or endosomal escape; avoids lysosomal degradation [7] [10] |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental pathways these vehicles take to enter cells and deliver their CRISPR cargo.

Viral Vector Uptake and Processing

Viral vectors are engineered to exploit naturally evolved mechanisms for efficient cellular entry.

Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs) first bind to primary receptors (e.g., HGFR for AAV2) and co-receptors (e.g., αVβ5 integrin) on the cell surface. This binding triggers clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Inside the resulting endosome, the acidic environment triggers conformational changes in the viral capsid, leading to endosomal escape. The viral single-stranded DNA genome is then imported into the nucleus [1] [11]. A key advantage is their episomal persistence, which avoids insertional mutagenesis but can also lead to transient expression depending on the cell type [1].

Lentiviral Vectors (LVs), often pseudotyped with the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus G-glycoprotein (VSV-G), enter primarily through receptor-mediated endocytosis. The VSV-G protein binds ubiquitously to LDL receptors on the target cell. Following endocytosis, the viral envelope fuses with the endosomal membrane in an acidification-dependent process, releasing the viral core into the cytoplasm. Here, the viral RNA is reverse-transcribed into DNA, forming a pre-integration complex that is actively transported into the nucleus via the nuclear pore complex. A defining feature of LVs is their ability to integrate the transgene into the host genome, enabling long-term expression—a critical feature for durable CAR-T cell therapies [1] [12].

Non-Viral Vector Uptake and Processing

Non-viral vectors offer advantages in safety and manufacturability, with uptake mechanisms that are primarily endocytic.

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) interact with the cell membrane through electrostatic and apolar interactions, leading to engulfment via endocytosis. A critical step for LNP success is endosomal escape. Modern LNPs contain ionizable cationic lipids that are neutral at physiological pH but become positively charged in the acidic endosome. These protonated lipids can disrupt the endosomal membrane, facilitating the release of the CRISPR payload (e.g., RNP, mRNA) into the cytoplasm before the endosome matures into a degradative lysosome [1] [13]. The intrinsic liver tropism of systemically administered LNPs has been effectively leveraged in clinical trials for liver-specific diseases like hATTR and HAE [5].

Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) are natural lipid nanoparticles that can enter cells through multiple routes. They can engage in direct membrane fusion, releasing their cargo directly into the cytosol, thereby bypassing endosomal entrapment entirely. Alternatively, they can enter via endocytosis [7] [9]. Their native composition provides innate biocompatibility and reduces immunogenicity. Recent engineering strategies, such as fusing RNA-binding domains (e.g., MS2 coat protein) to EV-enriched tetraspanins (e.g., CD63), have significantly improved the loading efficiency of Cas9 RNP complexes, enabling robust gene editing [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Analyzing LNP Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking

This protocol outlines the steps to track the cellular uptake and endosomal escape of LNPs delivering CRISPR RNP in vitro, using HeLa cells as a model system. The methodology is adapted from recent research on RNP-MITO-Porter systems [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for LNP Uptake and Trafficking Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 RNP Complex | Active CRISPR editing machinery. | Pre-complexe Cas9 protein with fluorescently labeled sgRNA (e.g., Cy5). |

| Ionizable Lipid LNPs | Delivery vehicle. | Formulated with ionizable lipid (e.g., DOPE), phospholipid, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid [13]. |

| HeLa Cell Line | Model adherent cell line. | Easy to culture and transfert; used extensively in uptake studies [13]. |

| LysoTracker Deep Red | Fluorescent dye labeling acidic organelles (lysosomes). | Used to assess co-localization and endosomal escape. |

| DMEM Growth Medium | Cell culture maintenance. | Supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. |

| Confocal Microscopy | High-resolution imaging of intracellular trafficking. | Equipped with lasers for DAPI, FITC, Cy5, and far-red channels. |

| Flow Cytometer | Quantitative analysis of cellular uptake. | Measures fluorescence intensity in thousands of cells. |

| 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cell fixation. | Preserves cellular structures for imaging. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

LNP Formulation and Characterization:

- Formulate LNPs encapsulating Cy5-labeled RNP using a microfluidic device. The aqueous phase contains the RNP in HEPES buffer, while the organic phase contains the lipid mix in ethanol. Rapid mixing in the device promotes self-assembly into particles [13].

- Characterize the resulting LNP suspension using dynamic light scattering (DLS) to ensure a homogeneous particle size (e.g., ~70 nm) and a positive zeta potential, which aids in cellular interaction [13].

Cell Seeding and Preparation:

- Seed HeLa cells in glass-bottom imaging dishes at a density of 1.5 x 10^5 cells per dish in complete DMEM growth medium.

- Incubate the cells at 37°C and 5% CO₂ for 24 hours to achieve 60-70% confluency at the time of treatment.

LNP Treatment and Live-Cell Staining:

- Replace the culture medium with a fresh, pre-warmed medium.

- Add the formulated RNP-LNPs to the cells at a predetermined optimal concentration.

- Incubate for 4 hours at 37°C to allow for uptake and trafficking.

- One hour before the end of the incubation, add LysoTracker Deep Red to the culture medium at a recommended working concentration to stain acidic compartments.

Sample Fixation and Preparation:

- After incubation, carefully aspirate the medium and wash the cells three times with PBS to remove any non-internalized LNPs.

- Fix the cells by adding 4% PFA for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash again with PBS and add an anti-fade mounting medium containing DAPI to stain the nuclei.

Image Acquisition and Analysis via Confocal Microscopy:

- Image the cells using a confocal laser scanning microscope.

- Use the following channels: DAPI (nucleus, blue), FITC/GFP (optional other marker, green), Cy5 (RNP-LNPs, red), and far-red (LysoTracker, magenta).

- Acquire Z-stack images to capture the 3D distribution of the signal within the cells.

- To analyze endosomal escape, quantify the degree of co-localization between the Cy5 signal (RNP) and the LysoTracker signal (acidic endosomes/lysosomes) using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ with JaCoP plugin). A decrease in the Pearson's correlation coefficient over time indicates successful endosomal escape of the RNP cargo.

Quantitative Uptake Measurement via Flow Cytometry:

- In parallel, seed and treat HeLa cells in a standard 6-well plate under identical conditions.

- After the 4-hour incubation and PBS washes, trypsinize the cells, collect them in centrifuge tubes, and resuspend in flow cytometry buffer.

- Analyze the cells using a flow cytometer, detecting the Cy5 fluorescence. The geometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the treated cells, compared to untreated controls, provides a quantitative measure of LNP uptake.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagent Solutions for Studying Cellular Uptake

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Uptake Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Inhibitors | Chlorpromazine (clathrin-mediated endocytosis), Dynasore (dynamin), Filipin (caveolae-mediated endocytosis), Amiloride (macropinocytosis) [1] [10] | To delineate the primary endocytic pathway by selectively inhibiting specific mechanisms. |

| Fluorescent Labels | Cy5, FITC, Rhodamine (for labeling sgRNA, proteins, or lipids); Lipophilic dyes (e.g., DiI, DiO) [7] [13] | To visually track the vehicle and/or cargo throughout the uptake and intracellular trafficking process via microscopy and flow cytometry. |

| Endo/Lysosomal Markers | LysoTracker (acidic compartments), antibodies against LAMP1 or Rab proteins (early/late endosomes) [13] | To identify and track the progression of vesicles through the endosomal-lysosomal system and assess escape. |

| Engineered Cell Lines | Cells stably expressing fluorescently tagged organelle markers (e.g., GFP-Rab5 for early endosomes) | To enable live-cell imaging of cargo trafficking in real-time within defined intracellular compartments. |

Efficient intracellular delivery of the CRISPR-Cas9 system represents one of the most significant challenges in therapeutic genome editing. The success of any CRISPR-based experiment or therapy fundamentally depends on overcoming three interconnected delivery hurdles: the physical size limitations of the cargo, its stability within the cellular environment, and the ultimate requirement for nuclear access to enact genetic changes. This application note examines these critical parameters, providing a structured analysis and practical protocols to guide researchers in selecting and optimizing CRISPR delivery strategies for cell-based research and drug development.

Quantitative Analysis of CRISPR Delivery Cargo

The form in which CRISPR components are delivered significantly impacts editing efficiency, specificity, and potential cytotoxicity. The primary cargo configurations each present distinct advantages and challenges related to size, stability, and functionality.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of CRISPR-Cas9 Cargo Configurations

| Cargo Form | Typical Size | Stability Considerations | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Plasmid | ~9-12 kb (for SpCas9) | Variable expression; prolonged activity increases off-target risk [1] | Simplicity of cloning and production; long-term expression | Cytotoxicity; variable editing efficiency; immunogenicity [1] |

| mRNA + gRNA | ~4.5 kb (SpCas9 mRNA) | mRNA susceptible to degradation; requires chemical modifications for stability [1] [14] | Transient expression; reduced off-target effects compared to plasmids | Requires nuclear export for translation; immunogenic potential |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | ~160 kDa (SpCas9 protein) | Immediate activity; rapid degradation minimizes off-target effects [1] [7] | Highest precision; minimal off-target effects; immediate activity [1] | More complex delivery due to large size and charge; limited time window for editing |

The cargo size directly influences the selection of an appropriate delivery vehicle, particularly when considering viral vectors with fixed payload capacities.

Table 2: Cargo Size Compatibility with Viral Delivery Vectors

| Viral Vector | Payload Capacity | Compatibility with CRISPR Cargo | Strategies for Large Cargos |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | ~4.7 kb [1] | Too small for full SpCas9 (∼4.2 kb); requires dual-AAV systems or smaller Cas variants [1] | Use of smaller Cas enzymes (e.g., Cas12a, SaCas9); split-intein systems; separate delivery of Cas and gRNA [1] |

| Adenoviral Vectors (AdVs) | Up to 36 kb [1] | Readily accommodates Cas9, gRNA, and donor DNA templates | Minimal size constraints; suitable for large multi-component systems |

| Lentiviral Vectors (LVs) | ~8 kb | Can package most single CRISPR components | Suitable for Cas9 ORF delivery; used extensively for ex vivo editing (e.g., CAR-T cells) |

Cargo Stability and Nuclear Access Requirements

Beyond size considerations, cargo stability and nuclear translocation are critical determinants of editing success. The journey from extracellular delivery to functional nuclear activity presents multiple biological barriers.

Biological Barrier Navigation for CRISPR Cargo

The diagram above illustrates the sequential challenges CRISPR cargo must overcome from delivery to functional nuclear activity. Each barrier demands specific consideration during experimental design:

Endosomal Escape: Lipid-based nanoparticles (LNPs) and cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) must facilitate escape before cargo degradation in lysosomal pathways [1]. The endosomal entrapment remains a primary cause of failed delivery for non-viral methods.

Cytoplasmic Stability: mRNA is particularly vulnerable to cytoplasmic nucleases, while RNP complexes benefit from immediate functionality without additional processing steps. Chemical modifications to mRNA (e.g., pseudouridine) can enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity [14].

Nuclear Membrane Translocation: The nuclear pore complex restricts passive diffusion of molecules larger than ~40 kDa. DNA plasmids require nuclear envelope breakdown during cell division for efficient access, while RNPs and mRNA-derived Cas9 depend on nuclear localization signals (NLS) for active transport [1]. This makes RNP delivery particularly challenging in non-dividing cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPOR Web Tool | Guide RNA design and off-target prediction [15] | Selecting optimal gRNAs with high on-target and low off-target activity |

| MS2-MCP Loading System | Modular RNP loading into extracellular vesicles [7] | EV-mediated delivery using RNA-binding domains and aptamers |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Encapsulation and delivery of nucleic acids or proteins [1] | in vivo delivery of CRISPR components; clinically validated platform |

| UV-Cleavable Linker (PhoCl) | Controlled cargo release post-delivery [7] | Light-activated release of CRISPR machinery from delivery vehicles |

| eGFP-to-BFP Reporter System | Rapid assessment of editing outcomes [16] | Quantifying HDR vs. NHEJ repair outcomes via fluorescence conversion |

| Selective Organ Targeting (SORT) LNPs | Tissue-specific nanoparticle delivery [1] | Targeted delivery to lung, spleen, and liver tissues |

Detailed Protocol: EV-Mediated RNP Delivery Using MS2-MCP System

This protocol details a modular strategy for extracellular vesicle-mediated CRISPR-Cas9 RNP delivery, leveraging MS2 coat protein (MCP) fusion constructs and MS2 aptamer-modified sgRNAs for efficient loading and targeted release [7].

Materials and Reagents

- Plasmid constructs: MCP-CD63 fusion, Cas9 expression vector, MS2-sgRNA expression vector

- HEK293T cells (or other appropriate packaging cell line)

- Cell culture media and transfection reagent (e.g., PEI, lipofectamine)

- Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) system

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) columns

- OptiPrep density gradient medium

- Anti-CD63, anti-CD9 antibodies for immunocapture

- UV light source (365 nm) for PhoCl cleavage

Procedure

Day 1: Cell Seeding and Transfection

- Seed HEK293T cells in appropriate culture vessels at 60-70% confluence.

- Prepare transfection mixture containing three plasmid constructs:

- MCP-CD63 fusion construct (for EV loading)

- Cas9 or variant (e.g., ABE8e, dCas9-VPR) expression vector

- MS2-sgRNA expression vector with aptamers incorporated in tetraloop and stemloop 2

- Transfect cells using preferred transfection method and incubate for 48 hours.

Day 3: EV Isolation and Purification

- Collect cell culture supernatant and remove cells and debris by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 30 minutes.

- Concentrate the supernatant using Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) with a 100-500 kDa molecular weight cutoff membrane.

- Further purify EVs by Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) using commercially available columns (e.g., qEVoriginal).

- Characterize EV preparation by:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) for size distribution and concentration

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for morphological assessment

- Western blot for EV markers (CD63, ALIX, TSG101) and absence of contaminants (Calnexin)

Day 3: EV Loading Validation

- Verify Cas9 RNP loading by Western blot comparing EVs with and without MCP-CD63 expression.

- Quantify sgRNA loading efficiency using digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) or qPCR.

- Confirm EV association through OptiPrep density gradient centrifugation - Cas9 should co-localize with EV markers in specific density fractions (1.10-1.18 g/mL).

Day 4: Target Cell Transduction and UV Activation

- Incubate isolated EVs with target cells for 24 hours.

- Expose cells to UV light (365 nm, optimized duration) to cleave the PhoCl linker and release Cas9 RNP cargo.

- Allow cells to recover for 24-72 hours before assessing editing efficiency.

Expected Outcomes and Troubleshooting

- Successful EV loading should yield ≥50-fold enrichment of Cas9 and sgRNA in EVs from MCP-CD63 expressing cells versus controls [7].

- Low loading efficiency may indicate issues with MCP-MS2 interaction - verify aptamer incorporation in sgRNA and MCP fusion protein expression.

- Poor editing in target cells may require optimization of EV:cell ratio or UV exposure conditions for efficient cargo release.

The interdependent considerations of cargo size, stability, and nuclear access requirements form the foundation of successful CRISPR-Cas9 experimental design. By matching cargo configuration to appropriate delivery vehicles and acknowledging the biological barriers to nuclear delivery, researchers can significantly enhance editing efficiency while minimizing off-target effects. The protocols and analytical frameworks provided here offer a structured approach to navigating these complex decisions, ultimately supporting the development of more reliable and reproducible CRISPR-based research and therapeutic applications.

The transformative potential of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in therapeutic applications is fundamentally constrained by a single, multifaceted challenge: the safe, efficient, and specific delivery of its molecular components into target cells. This dilemma, often termed "the delivery problem," represents the critical bottleneck in translating laboratory success into clinical breakthroughs [8] [9]. The core of this challenge lies in balancing three interdependent properties—Efficiency, the successful delivery and editing activity in a high percentage of target cells; Specificity, the minimization of off-target effects at unintended genomic sites; and Safety, the avoidance of immunogenic responses and long-term toxicities [17] [1]. These three properties form a "Delivery Triad" where optimizing one often compromises another. For instance, viral vectors can provide high efficiency but may raise safety concerns due to immunogenicity and long-term persistence, while physical methods are transient but can suffer from low efficiency and poor specificity [1]. This document provides a structured analysis of CRISPR-Cas9 delivery strategies through the lens of this triad, offering application notes and detailed protocols to guide researchers in making informed decisions for their experimental and therapeutic designs.

Cargo Types: The Foundation of the Editing Experiment

The form in which CRISPR-Cas9 components are delivered—the cargo—profoundly influences the outcome of a gene-editing experiment by directly affecting the triad's balance. The three primary cargo types offer distinct trade-offs between editing duration, off-target risk, and complexity of delivery [8] [18] [1].

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 Cargo Types

| Cargo Type | Components Delivered | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Impact on Triad |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA (pDNA) | DNA plasmid encoding Cas9 and gRNA [8] [1]. | Simple design, low-cost production, sustained expression [8] [18]. | Risk of genomic integration, prolonged Cas9 expression increasing off-target effects, cytotoxicity, large size [8] [18] [1]. | Safety: MediumSpecificity: LowEfficiency: Medium |

| Messenger RNA (mRNA) | mRNA for Cas9 + separate gRNA [8] [1]. | Rapid editing, transient activity, reduced off-target effects, no risk of genomic integration [8] [18]. | Instability, strong immune response, requires nuclear entry for activity, lower efficiency in some systems [8] [18]. | Safety: LowSpecificity: HighEfficiency: Medium |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and gRNA [8] [1]. | Highest specificity, immediate activity, shortest persistence, minimal off-target effects [8] [18]. | Difficult and expensive to manufacture, challenging in vivo delivery, lack of efficient delivery vectors in vivo [8] [18]. | Safety: HighSpecificity: HighEfficiency: Low |

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making pathway for selecting the most appropriate cargo type based on the experimental goals and constraints related to the Delivery Triad.

Delivery Vehicles: Navigating Biological Barriers

The vehicle is as critical as the cargo, determining how CRISPR components traverse biological barriers to reach the nucleus. Vehicles are broadly classified into viral, non-viral, and physical methods, each with distinct implications for the Delivery Triad [8] [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Major CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Vehicles

| Delivery Vehicle | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Ideal Cargo | Impact on Triad |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Non-pathogenic virus; delivers genetic cargo without genome integration [18] [1]. | Low immunogenicity, high transduction efficiency, proven clinical success [18] [1]. | Limited packaging capacity (~4.7 kb), potential for long-term expression, pre-existing immunity in populations [18] [1]. | DNA, gRNA alone [1] | Safety: MediumSpecificity: MediumEfficiency: High |

| Lentivirus (LV) | Retrovirus that integrates into the host genome [18] [1]. | Large cargo capacity, infects dividing and non-dividing cells, stable long-term expression [1]. | Integration raises oncogenic risk, more severe off-target potential, complex safety profile [18] [1]. | DNA [1] | Safety: LowSpecificity: LowEfficiency: High |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Synthetic lipid vesicles encapsulating cargo; fuse with cell membrane [8] [1]. | Low immunogenicity, tunable organ targeting (e.g., liver), FDA-approved for mRNA, suitable for redosing [8] [18] [5]. | Endosomal entrapment and degradation, primarily liver-tropic with current formulations [8] [1]. | mRNA, RNP, DNA [8] [1] | Safety: HighSpecificity: MediumEfficiency: Medium |

| Electroporation | Electrical pulse creates temporary pores in cell membrane for cargo entry [8]. | High efficiency for hard-to-transfect cells (e.g., stem cells), direct delivery, clinical validation (CASGEVY) [8] [5]. | Mostly restricted to ex vivo use, can impact cell viability [8] [1]. | RNP, mRNA, DNA [8] | Safety: HighSpecificity: MediumEfficiency: High |

A landmark demonstration of balancing the delivery triad is the first FDA-approved CRISPR therapy, CASGEVY. It successfully employs electroporation for the ex vivo delivery of RNP complexes into patient hematopoietic stem cells. This strategy maximizes specificity and safety (via RNP's transient activity) while achieving high efficiency in a clinically challenging cell type, offering a curative treatment for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia [8] [5].

Application Note: An Integrated Workflow for In Vivo Liver Editing

The following workflow diagram and protocol detail a methodology for efficient in vivo gene editing, leveraging the high liver tropism of certain delivery vehicles.

Protocol: Systemic Administration of LNP-mRNA for Liver Gene Knockdown

This protocol is adapted from successful clinical trials for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR), where a single dose of LNP-mRNA achieved ~90% reduction of the disease-related TTR protein [5].

Materials & Reagents

- CRISPR-mRNA: Codon-optimized mRNA encoding SpCas9 or a high-fidelity variant, purified and sterile.

- sgRNA: Synthetic single-guide RNA targeting the gene of interest, HPLC-purified.

- LNP Formulation: Ionizable lipid (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA), phospholipid, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid for nanoparticle self-assembly.

- Animal Model: Adult mice (e.g., C57BL/6).

- Delivery Equipment: Syringe and needle for IV injection (e.g., via tail vein).

- Analytical Tools: ELISA kit for target protein quantification, NGS platform for off-target analysis.

Procedure

- LNP Formulation: Formulate CRISPR-mRNA and sgRNA into LNPs using a microfluidic mixer. The aqueous phase containing the mRNA/gRNA is mixed with the ethanol phase containing dissolved lipids at a specific flow rate ratio to form stable, monodisperse particles. Dialyze the formulated LNPs against a sterile buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4) to remove residual ethanol. Sterile-filter the final product through a 0.22 µm filter.

- Quality Control: Characterize the LNPs for particle size (targeting 70-100 nm), polydispersity index (PDI < 0.2), and mRNA encapsulation efficiency (>90%) using dynamic light scattering (DLS) and Ribogreen assays.

- Systemic Administration: Calculate the dose based on mRNA (e.g., 1-3 mg/kg). Gently warm the animal to dilate the tail vein. Slowly inject the LNP formulation intravenously via the tail vein. Monitor the animal for any acute adverse reactions.

- Efficacy Assessment: At defined timepoints post-injection (e.g., 7, 14, 28 days), collect blood samples via retro-orbital bleeding or terminal cardiac puncture. Isolate serum and quantify the level of the target protein using a validated ELISA.

- Specificity & Safety Profiling: At the study endpoint, harvest the liver and other potential off-target organs. Extract genomic DNA. Use unbiased methods like GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq to comprehensively profile potential off-target sites. Sequence the on-target locus to determine the indel percentage.

Protocol: Rapid Screening of Gene Editing Outcomes via eGFP Disruption

This protocol provides a cell-based method for the high-throughput, quantitative assessment of delivery efficiency and DNA repair outcomes, enabling rapid iteration and optimization of delivery parameters [16].

Materials & Reagents

- Cell Line: HEK293T or other readily transfectable mammalian cell line.

- Lentiviral Vector: Plasmid for producing lentivirus encoding eGFP.

- CRISPR Components: Pre-designed sgRNA targeting the eGFP sequence and Cas9 (as pDNA, mRNA, or RNP).

- Transfection Reagent: Lipofectamine 2000 or similar for pDNA/mRNA delivery; or electroporation kit for RNP delivery.

- Instrumentation: Flow cytometer.

Procedure

- Generate eGFP-Expressing Cell Line: Produce lentiviral particles by co-transfecting HEK293T cells with the eGFP transfer plasmid and packaging plasmids (psPAX2, pMD2.G). Harvest the virus-containing supernatant, filter it, and transduce your target cell line. Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to select a pure population of eGFP-positive cells.

- Transfection with CRISPR Components: Seed eGFP-positive cells in a multi-well plate. Transfect the cells with the Cas9/sgRNA constructs using a method appropriate for your cargo (e.g., lipofection for pDNA/mRNA, electroporation for RNP). Include a non-targeting sgRNA as a negative control.

- Incubation and Harvest: Incubate the cells for 48-72 hours to allow for gene editing and turnover of the existing eGFP protein.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Harvest the cells, wash with PBS, and resuspend in a FACS-compatible buffer. Analyze the cells using a flow cytometer. Measure the fluorescence in the FITC (green) channel to detect eGFP loss and other channels (e.g., Pacific Blue) to detect potential BFP conversion if using a specific donor template [16].

- Data Interpretation: The percentage of cells that have lost eGFP fluorescence (FITC-negative) corresponds to the total gene editing efficiency, primarily resulting from NHEJ-induced indels. A shift to a blue fluorescence profile indicates successful HDR.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Key Considerations for the Delivery Triad |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Engineered Cas9 protein with reduced off-target activity [17]. | Directly enhances Specificity and Safety by minimizing unintended edits, potentially at a small cost to on-target Efficiency. |

| Selective Organ Targeting (SORT) LNPs | Engineered LNPs that modify natural tropism to target organs beyond the liver (e.g., spleen, lungs) [1]. | Dramatically improves Specificity by directing cargo to desired tissues, thereby improving therapeutic Efficiency and reducing off-target Safety risks. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) | Engineered viral capsids lacking viral genetic material; delivers functional Cas9-gRNA RNP complexes [18] [1]. | Improves Safety profile versus viral vectors (non-integrating, transient). Can enhance Efficiency of RNP delivery in vivo while maintaining high Specificity. |

| Base and Prime Editors | "CRISPR 2.0" systems that chemically alter a single base or search-and-replace a sequence without creating DSBs [17] [19]. | Major Safety and Specificity advancement by avoiding DSB-related genotoxicity and reducing off-target effects. Broadens therapeutic applications. |

| Unbiased Off-Target Assays | Methods like GUIDE-seq and CIRCLE-seq to genome-widely identify potential off-target sites [17]. | Critical for empirically measuring Specificity and validating the Safety profile of a chosen gRNA and delivery method. |

Navigating the Delivery Triad requires a strategic and balanced approach, where the choice of cargo, vehicle, and experimental protocol is dictated by the specific therapeutic or research goal. No single solution is universally superior; rather, the optimal strategy is context-dependent. The ongoing clinical success of ex vivo RNP delivery for hematopoietic diseases and in vivo LNP-mRNA delivery for liver-specific targets provides a robust framework and proof-of-concept for future therapies [5]. As the field progresses, emerging technologies—including novel capsids for targeted viral delivery, refined non-viral nanoparticles for systemic tissue targeting, and cleavage-free editing systems—are poised to further refine this balance, expanding the reach of CRISPR-based medicines to a broader array of genetic disorders [17] [1] [19].

Delivery in Action: Viral, Non-Viral, and Physical Methodologies

The efficacy of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing is profoundly influenced by the delivery system used to introduce its components into target cells. Viral vectors, including adeno-associated virus (AAV), lentivirus (LV), and adenovirus (AdV), have emerged as leading vehicles for this purpose, each offering distinct advantages and challenges. Their performance directly impacts critical factors such as editing efficiency, specificity, and therapeutic safety [8] [20]. Within the context of a broader thesis on delivery methods for CRISPR-Cas9, this document provides detailed application notes and standardized protocols for employing these viral vectors in a research setting, supporting the development of next-generation gene therapies.

Comparative Analysis of Major Viral Vector Systems

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of AAV, lentiviral, and adenoviral vectors to guide appropriate selection for research applications.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Viral Vectors for CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery

| Feature | Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Lentivirus (LV) | Adenovirus (AdV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Packaging Capacity | <4.7 kb [11] [1] [21] | ~8 kb [1] | Up to 36 kb [1] |

| Integration Profile | Predominantly episomal; non-integrating [21] | Integrates into host genome [1] | Non-integrating [1] |

| Transgene Expression Duration | Long-term (can persist for years) [11] | Long-term (stable expression) [1] | Transient [1] |

| Tropism & Specificity | High; serotype-dependent tissue tropism [11] [21] | Broad; can be pseudotyped to alter tropism [1] | Broad; can be modified for specificity [1] |

| Immunogenicity | Low; mild immune response [11] [1] | Moderate; HIV backbone raises safety concerns [1] | High; can trigger strong immune responses [1] |

| CRISPR Cargo Format | DNA (requires compact Cas versions or dual vectors) [11] | DNA (integrating) [1] | DNA (non-integrating) [1] |

Application Notes

Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vectors

AAV vectors are a premier choice for in vivo gene therapy due to their excellent safety profile and sustained transgene expression [11]. A significant challenge is their limited packaging capacity (~4.7 kb), which is insufficient for the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9). Researchers have developed ingenious strategies to overcome this:

- Compact Cas Orthologs: Employing smaller Cas proteins, such as Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9, ~3.2 kb) or the even smaller Cas12f, allows for packaging of the entire CRISPR machinery into a single "all-in-one" vector [11] [22].

- Dual-Vector Systems: For larger nucleases, the Cas9 and guide RNA (gRNA) can be split across two separate AAV vectors. While this necessitates co-infection of the same cell, strategies like intein-mediated trans-splicing can reconstitute the full protein [11].

AAV serotype selection is critical as it dictates tissue tropism. For example, AAV5 is effective for retinal delivery (as in the clinical trial EDIT-101 for Leber Congenital Amaurosis), while AAV9 exhibits strong tropism for the liver and central nervous system [11] [21].

Lentiviral Vectors (LVs)

Lentiviral vectors are exceptional for ex vivo applications and functional genomics screens due to their ability to stably integrate into the host genome, including non-dividing cells [1]. This makes them ideal for creating stable cell lines for long-term gene expression studies. A primary safety consideration is the potential for insertional mutagenesis due to random integration, though the use of integrase-deficient LVs (IDLVs) can provide transient expression and mitigate this risk [23]. Their relatively large packaging capacity (~8 kb) easily accommodates SpCas9 and multiple gRNAs, enabling complex multiplexed editing experiments [1].

Adenoviral Vectors (AdVs)

Adenoviral vectors feature a very large packaging capacity (up to 36 kb), making them one of the few viral platforms capable of delivering SpCas9, multiple gRNAs, and even a donor DNA template for homology-directed repair (HDR) within a single particle [1]. They are non-integrating and provide high-level, transient transgene expression, which is advantageous for reducing long-term off-target effects. However, their high immunogenicity can trigger robust inflammatory responses, which may be a liability for therapeutic in vivo applications but can be harnessed for vaccine development [1].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing CRISPR Editing Outcomes via eGFP-to-BFP Conversion

This protocol provides a high-throughput method to screen and quantify the efficiency of different CRISPR delivery systems by measuring the conversion of enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP) to Blue Fluorescent Protein (BFP) in a cell population [16].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for eGFP-to-BFP Assay

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| eGFP-Expressing Cell Line | Target cells providing a visual readout for editing. Can be generated via lentiviral transduction. |

| CRISPR Delivery System | Viral vectors (AAV, LV, AdV) or non-viral methods containing Cas9 and anti-eGFP gRNA. |

| Anti-eGFP gRNA | Guide RNA designed to target the eGFP sequence for cleavage. |

| HDR Donor Template | DNA template encoding BFP mutation with homology arms for precise repair. |

| Flow Cytometer | Instrument for quantifying the percentages of eGFP-positive and BFP-positive cells. |

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Generate or obtain a stably transduced cell line with uniform, high-level eGFP expression.

- Transfection/Transduction: Deliver the CRISPR-Cas9 components (as plasmid DNA, mRNA, or RNP) along with the HDR donor template using your chosen method (e.g., viral transduction).

- For viral delivery, transduce cells at an appropriate multiplicity of infection (MOI) determined by pilot experiments.

- Incubation: Culture the cells for 3-7 days to allow for genome editing and expression of the BFP phenotype.

- Harvesting and Analysis: Harvest the cells and analyze them using a flow cytometer.

- Measure fluorescence: Detect eGFP (excitation ~488 nm, emission ~510 nm) and BFP (excitation ~405 nm, emission ~450 nm).

- Data Interpretation:

- Knockout Efficiency: Calculate the percentage of cells that have lost eGFP fluorescence (eGFP-negative), indicating indels from NHEJ repair.

- HDR Efficiency: Calculate the percentage of cells that have gained BFP fluorescence (BFP-positive), indicating precise HDR-mediated editing.

Protocol: In Vivo Gene Editing Using AAV Vectors

This protocol outlines the key steps for performing in vivo genome editing in a mouse model using AAV vectors, a common approach for preclinical therapeutic studies [11].

Procedure:

- Vector Design and Production:

- Select Cas Ortholog: Choose a nuclease compatible with AAV packaging (e.g., SaCas9) if using an all-in-one system. Alternatively, design dual vectors for larger nucleases.

- Clone Components: Clone the expression cassettes for the Cas nuclease and gRNA(s) into the AAV vector backbone, ensuring they are flanked by inverted terminal repeats (ITRs).

- Package and Purify: Produce recombinant AAV particles using a triple-transfection system in HEK293T cells and purify via ultracentrifugation or chromatography.

- In Vivo Delivery:

- Administration Route: Choose based on target tissue (e.g., systemic intravenous injection for liver editing, subretinal injection for retinal editing).

- Dosage: Titrate the vector dose (e.g., (1 \times 10^{11} - 1 \times 10^{13}) vector genomes per animal) based on pilot studies and literature.

- Validation and Analysis:

- Harvest Tissues: After a suitable period (e.g., 2-4 weeks), harvest the target tissues.

- Assess Editing: Use next-generation sequencing (NGS) or T7E1 assay to quantify indel frequencies at the target locus.

- Evaluate Phenotype: Perform functional assays (e.g., immunohistochemistry, behavioral tests, biomarker analysis) to assess the physiological outcome.

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision-making pathway for selecting and applying viral vectors in a CRISPR-Cas9 research project.

The clinical success of Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) in mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines has catalyzed their rapid adoption as a premier delivery platform for CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. LNPs provide a solution to one of the most significant challenges in therapeutic genome editing: the safe and efficient transport of CRISPR components into target cells. This document details the application of LNP technology for CRISPR delivery, providing a comparative analysis of cargo formats, step-by-step experimental protocols, and an overview of the current clinical landscape to aid researchers in transitioning this technology from concept to bench.

LNP Fundamentals and Mechanism of Action

LNPs are sophisticated, multi-component systems whose function is dictated by their precise composition.

1.1 Core Components: A standard LNP formulation for nucleic acid delivery includes four key lipids [24]:

- Ionizable Lipids: The most critical component (e.g., ALC-0315, SM-102). They are neutral at physiological pH but acquire a positive charge in acidic environments, enabling efficient mRNA encapsulation during formulation and facilitating endosomal escape post-cell entry [25] [26].

- Phospholipids: Helper lipids (e.g., DSPC) that contribute to the bilayer structure and stability of the particle.

- Cholesterol: A structural lipid that integrates into the LNP membrane, enhancing stability and facilitating cellular uptake.

- PEG-lipids: Located on the LNP surface, these lipids control particle size, prevent aggregation during storage and circulation, and modulate in vivo pharmacokinetics [24] [27].

1.2 Mechanism of Intracellular Delivery: The journey of an LNP from administration to protein expression or gene editing involves a defined cascade [28]:

- Cellular Uptake: LNPs are internalized by cells via endocytosis.

- Endosomal Trafficking: The LNP is encapsulated within an endosome, which acidifies as it matures.

- Endosomal Escape: The acidic environment of the endosome protonates the ionizable lipids, inducing a structural transition from an inverse micellar to an inverse hexagonal phase. This transition disrupts the endosomal membrane, releasing the nucleic acid payload into the cytoplasm [25].

- Payload Function: For CRISPR applications, the released mRNA is translated into the Cas9 protein, which complexes with the gRNA to form the active editing machinery.

The diagram below illustrates this key mechanism of endosomal escape.

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR Cargo Formats for LNP Delivery

CRISPR-Cas9 components can be delivered via LNPs in different formats, primarily as mRNA/sgRNA or as a pre-complexed Ribonucleoprotein (RNP). The choice of cargo significantly impacts editing efficiency, kinetics, and safety. A summary of the quantitative differences is provided in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of LNP-Mediated CRISPR Cargo Formats [29] [30]

| Feature | mRNA/sgRNA | Cas9 RNP |

|---|---|---|

| Editing Efficiency (in vivo) | Up to 60% knockout in hepatocytes [30] | Minimal editing detected in mouse liver [30] |

| Onset of Action | Delayed (requires translation) | Immediate |

| Duration of Activity | Transient (hours to days) | Very short (hours) |

| Risk of Off-Target Effects | Moderate (prolonged Cas9 expression) | Lower (transient activity) |

| Particle Size | Smaller (~80 nm) [30] | Larger |

| Biodistribution (Systemic) | Primarily liver | Liver, spleen, and lungs [30] |

| Payload Protection | Better protection from nucleases [30] | Potentially less stable |

Protocols for LNP Formulation and Testing

This section provides detailed methodologies for formulating and evaluating LNPs for CRISPR delivery.

3.1 LNP Formulation via Ethanol Injection

- Principle: Lipids dissolved in an organic phase are rapidly mixed with an aqueous phase containing the nucleic acid payload, leading to spontaneous nanoparticle formation [26].

- Materials:

- Ionizable lipid, phospholipid, cholesterol, PEG-lipid

- Anhydrous ethanol

- CRISPR payload: mRNA, sgRNA, or Cas9 RNP complex in citrate buffer (pH 4.0)

- Microfluidic mixer or tangential flow filtration system

- Dialysis cassettes and PBS (pH 7.4)

- Procedure:

- Dissolve the lipid mixture (e.g., 50:10:38.5:1.5 molar ratio of ionizable lipid:DSPC:cholesterol:PEG-lipid) in ethanol to a final concentration of 10-20 mg/mL total lipids [26].

- Prepare the aqueous phase by dissolving the CRISPR payload in a citrate buffer (e.g., 25 mM, pH 4.0). An N/P ratio (moles of amine in lipid to moles of phosphate in nucleic acid) of 3:1 to 6:1 is typically optimal [26] [30].

- Rapidly mix the ethanolic lipid solution and the aqueous nucleic acid solution using a microfluidic device at a fixed flow rate (e.g., 1:3 volumetric ratio) to form LNPs.

- Immediately dialyze the formed LNPs against a large volume of PBS (pH 7.4) for at least 4 hours at 4°C to remove ethanol and balance the pH.

- Sterile-filter the final LNP formulation (0.22 µm pore size) and store at 4°C for short-term use or at -80°C for long-term storage with cryoprotectants like sucrose.

3.2 Protocol for In Vitro Gene Editing in Adherent Cell Lines

- Principle: LNPs are used to transfert cells in culture, and editing efficiency is quantified by analyzing target genomic DNA.

- Materials:

- Adherent cell line (e.g., HEK293T, HEPA 1-6) [30]

- Complete cell culture medium

- LNP formulation (from Protocol 3.1)

- Opti-MEM or similar serum-free medium

- Genomic DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents and T7 Endonuclease I or tracking of indels by decomposition (TIDE) analysis reagents

- Procedure:

- Seed cells in a 24-well plate at a density of 1-2 x 10^5 cells/well and incubate for 24 hours to reach 60-80% confluency.

- Dilute the LNP formulation in Opti-MEM to the desired concentration.

- Remove the growth medium from the cells, wash with PBS, and add the LNP-Opti-MEM mixture.

- Incubate for 4-6 hours, then replace the transfection medium with fresh complete medium.

- Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection and extract genomic DNA.

- Amplify the target genomic locus by PCR and analyze the PCR products using the T7E1 assay or Sanger sequencing followed by TIDE analysis to quantify indel percentages [29].

The workflow for this in vitro protocol is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of LNP-based CRISPR delivery requires a suite of specialized reagents and equipment.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for LNP-CRISPR Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipid | pH-responsive lipid critical for encapsulation and endosomal escape. | ALC-0315, SM-102, ALC-0307 [24] |

| Cas9 mRNA | Template for in vivo production of the Cas9 nuclease. | Modified nucleotides for enhanced stability and reduced immunogenicity [27]. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Guides Cas9 to the specific genomic target. | Synthetic sgRNA with phosphorothioate bonds for improved nuclease resistance [29]. |

| Microfluidic Mixer | Instrument for controlled, rapid mixing of lipid and aqueous phases to form uniform LNPs. | NanoAssemblr, Mikro-Technik mixing chips. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Instrument for measuring LNP particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential. | Malvern Zetasizer. |

| T7 Endonuclease I Assay | Kit for detecting and quantifying CRISPR-induced indels at the target site. | New England Biolabs T7E1 kit. |

Clinical Translation and Future Directions

LNP-mediated CRISPR delivery has moved from proof-of-concept to clinical reality, demonstrating therapeutic potential in human trials.

5.1 Clinical Trial Highlights:

- hATTR Amyloidosis: Intellia Therapeutics' NTLA-2001, an LNP delivering CRISPR components targeting the TTR gene, achieved ~90% reduction in disease-causing protein levels after a single intravenous infusion, establishing a benchmark for in vivo gene editing [5].

- Personalized In Vivo Therapy: A landmark case in 2025 reported the development of a bespoke LNP-CRISPR therapy for an infant with CPS1 deficiency. The therapy was developed and administered within six months, and the patient safely received multiple doses, showing significant clinical improvement and establishing a regulatory precedent for rapid, personalized genomic medicine [5] [24].

5.2 Emerging Innovations and Challenges:

- Liver Tropism: A primary challenge is the inherent liver tropism of current LNPs. Research is actively focused on Selective Organ Targeting (SORT) molecules, which, when incorporated into LNPs, can redirect them to tissues like the lungs, spleen, and heart [24].

- Dosing Regimens: The low immunogenicity of LNPs enables re-dosing, a significant advantage over viral vectors. Clinical trials have successfully administered multiple LNP doses to enhance therapeutic effect, paving the way for "dosing to effect" paradigms [5] [24].

- Payload Capacity and Efficiency: Innovations like metal-ion-mediated mRNA enrichment (e.g., using Mn²⁺ to pre-condense mRNA) are being explored to double the payload capacity of LNPs, which could improve efficacy and reduce lipid-related toxicity [27].

LNPs have successfully pivoted from their foundational role in vaccines to becoming a versatile and powerful platform for CRISPR-Cas9 delivery. Their proven efficacy in clinical trials, combined with the flexibility for re-dosing and a favorable safety profile, positions them at the forefront of in vivo gene editing. Ongoing research aimed at overcoming challenges in tissue-specific targeting and payload optimization will further solidify LNPs as an indispensable tool in the development of next-generation genetic therapeutics.

The successful application of the CRISPR-Cas9 system in genetic research and therapeutic development is fundamentally dependent on the efficient delivery of its molecular components into target cells. Among the various strategies available, physical delivery methods—namely electroporation, microinjection, and magnetofection—offer distinct advantages and challenges. These techniques facilitate the direct introduction of CRISPR cargoes (plasmid DNA, mRNA, or ribonucleoprotein complexes) by temporarily disrupting cellular membranes or using physical forces to bypass them. This application note provides a comparative analysis of these three physical methods, summarizes key quantitative performance data in structured tables, and outlines detailed experimental protocols to assist researchers in selecting and optimizing these techniques for their specific CRISPR-Cas9 applications.

Physical delivery methods function by creating transient physical disruptions in the cell membrane or utilizing force to directly propel cargo into cells, thereby avoiding many of the biological barriers associated with viral and non-viral chemical methods [31] [8]. These techniques are particularly valuable for hard-to-transfect cells, such as primary cells and stem cells, and for applications requiring high precision and minimal extraneous material. The choice of physical method significantly impacts key outcome metrics including editing efficiency, cell viability, and experimental throughput. Furthermore, the format of the CRISPR cargo—whether as plasmid DNA, mRNA, or preassembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes—interacts with the delivery method to determine final editing success [32]. RNP delivery is often favored for its rapid activity and reduced off-target effects, as the complex is active immediately upon entry and quickly degraded [32].

Comparative Analysis and Performance Data

The table below provides a direct comparison of the three primary physical delivery methods across several critical parameters, offering a guide for initial method selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Physical CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Methods

| Parameter | Electroporation | Microinjection | Magnetofection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Electrical pulses create temporary pores in cell membrane [8]. | Fine needle mechanically injects cargo directly into cytoplasm or nucleus [32]. | Magnetic force pulls nucleic acid-coated nanoparticles into cells [29]. |

| Cargo Compatibility | DNA, mRNA, RNP [32]. | DNA, mRNA, RNP [32]. | RNP (e.g., complexed with SPIONs) [29]. |

| Typical Editing Efficiency | Very High (Up to 95% in amenable cell lines) [29]. | High (e.g., ~40% in HepG2 cells) [8]. | Variable (Can be limited by post-entry barriers despite efficient uptake) [29]. |

| Cell Viability | Variable; can be low under high-efficiency parameters [29]. | Low; technically demanding and damaging to cells [32]. | Generally high biocompatibility [29]. |

| Throughput | High (can process millions of cells). | Very Low (single-cell level). | Moderate to High. |

| Key Advantages | High efficiency, works on a broad range of cell types [32]. | Precise control over delivered dose, large cargo capacity [32]. | Low cytotoxicity, potential for targeted delivery with magnetic fields [29]. |

| Key Limitations | Can be damaging to cells, requires optimization of pulse parameters [29] [32]. | Technically demanding, low throughput, requires specialized equipment [32]. | Editing efficiency may not correlate with uptake; requires specialized nanoparticles [29]. |

The following table summarizes specific experimental data from published studies, illustrating how performance varies with specific protocols and cell types.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Data from Representative Studies

| Delivery Method | Cell Type/Model | Cargo Format | Key Parameters | Reported Editing Efficiency | Cell Viability / Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electroporation | SaB-1 (Sea Bream) Cell Line | RNP (3 µM, synthetic sgRNA) | 1800 V, 20 ms, 2 pulses | Up to 95% | ~20% survival | [29] |

| Electroporation | DLB-1 (Sea Bass) Cell Line | RNP (3 µM) | 1700 V, 20 ms, 2 pulses | ~28% | Sharply reduced viability | [29] |

| Electroporation | HSPCs (Human) | RNP (CASGEVY ex vivo therapy) | Not Specified | Up to 90% indels | N/A | [8] |

| Electroporation | Mouse Zygotes | RNP | Not Specified | Highly Efficient | N/A | [8] |

| Microinjection | HepG2 Cells | Not Specified (GFP reporter) | Not Specified | ~40% | N/A | [8] |

| Magnetofection | DLB-1 & SaB-1 Cell Lines | RNP with SPIONs@Gelatin | Not Specified | No detectable editing | Efficient uptake, highlighting post-entry barriers | [29] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for RNP Delivery via Electroporation

This protocol is adapted from a study achieving high editing efficiency in marine fish cell lines and is applicable to many mammalian cell types [29].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Complex: Purified Cas9 protein complexed with synthetic, chemically modified sgRNA (e.g., from Synthego) at a 3 µM final concentration [29].

- Electroporation Buffer: Opti-MEM or cell line-specific electroporation buffer.

- Cell Culture Media: Standard growth media supplemented with serum.

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest and count the target cells. Centrifuge and wash the cell pellet twice with electroporation buffer to remove all traces of serum and antibiotics. Resuspend the cells at a high concentration (e.g., 1-5 x 10^6 cells/mL) in the electroporation buffer.

- RNP Complex Formation: Pre-complex the recombinant Cas9 protein with the sgRNA at a molar ratio of 1:1.2 to 1:2 (Cas9:sgRNA). Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to allow for RNP formation.

- Electroporation Setup: Combine the cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complexes in an electroporation cuvette. Gently mix by pipetting. The final RNP concentration is typically 2-5 µM [29].

- Pulse Delivery: Place the cuvette in the electroporator and deliver the electrical pulse. Critical: Parameters must be optimized for each cell type. Example conditions from the literature include:

- Post-Electroporation Recovery: Immediately after pulsing, transfer the cells from the cuvette into a pre-warmed culture plate containing complete medium. Incubate the cells at standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2).

- Analysis: Assess editing efficiency via T7E1 assay, TIDE analysis, or NGS 48-72 hours post-electroporation. Cell viability can be determined 24 hours post-delivery using a trypan blue exclusion assay.

Protocol for Microinjection

This protocol outlines the general workflow for delivering CRISPR components via microinjection, commonly used for zygotes and single-cell applications [32] [8].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Injection Sample: CRISPR cargo (e.g., Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA, or pre-assembled RNP) in a nuclease-free injection buffer.

- Holding Pipette and Injection Needle: Specialized glass capillaries.

- Microinjection System: Comprising an inverted microscope, a micromanipulator, and a microinjector.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the injection mixture. For RNP delivery, combine Cas9 protein and sgRNA at a high concentration (e.g., 100-500 ng/µL) in an appropriate injection buffer and incubate prior to loading.

- Cell Immobilization: Secure the target cell (e.g., a zygote) using a holding pipette under the microscope.

- Needle Insertion: Carefully advance the injection needle through the zona pellucida (if present) and the cell membrane into the cytoplasm or pronucleus.

- Cargo Delivery: Apply a brief positive pressure pulse to expel a precise volume of the CRISPR cargo. A visible slight swelling of the cell indicates successful delivery.

- Needle Retraction: Gently retract the injection needle.

- Post-Injection Culture and Analysis: Wash the injected cells and transfer them to a culture medium for recovery and further development. Genotype the resulting embryos or cells to determine editing efficiency.

Protocol for Magnetofection

This protocol describes the use of magnetic nanoparticles, such as gelatin-coated SPIONs, for the delivery of CRISPR RNP complexes [29].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Magnetic Nanoparticles: Gelatin-coated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPIONs@Gelatin) [29].

- RNP Complex: Pre-assembled Cas9-sgRNA RNP.

- Magnetofection Reagent: A commercial reagent or protocol for conjugating RNPs to nanoparticles.

- Platform Magnet: A magnet designed to create a magnetic field across the culture vessel.

Methodology:

- RNP-Nanoparticle Complex Formation: Conjugate the pre-assembled RNP complexes to the surface of the magnetic nanoparticles according to the manufacturer's instructions. This may involve incubating the two components together to allow for electrostatic or covalent binding.

- Cell Preparation: Seed and culture the target cells in a multi-well plate until they reach 50-70% confluency.

- Transfection: Add the RNP-nanoparticle complexes directly to the cell culture medium. Gently swirl the plate to ensure even distribution.

- Magnetic Field Application: Place the culture plate on a platform magnet for a specified period (typically 15-30 minutes) to draw the magnetic particles onto the cell surface.

- Incubation and Analysis: Remove the plate from the magnet and continue incubating the cells under standard conditions. Analyze editing efficiency and cellular uptake after 48-72 hours. Note that efficient cellular uptake does not always guarantee successful gene editing, as post-entry barriers can be a significant limitation [29].

Workflow and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the key decision-making process for selecting and implementing a physical delivery method for CRISPR-Cas9.

Decision Workflow for Physical CRISPR Delivery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Physical Delivery

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic sgRNA | Chemically modified guide RNA for enhanced stability and reduced immunogenicity. | Outperformed in vitro transcribed (IVT) sgRNA, achieving up to 95% editing in electroporation [29]. |

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | High-purity, endotoxin-free nuclease for forming RNP complexes. | Essential for RNP-based delivery in electroporation and microinjection [32]. |

| Electroporation System | Instrument that delivers controlled electrical pulses to cells (e.g., Neon, Amaxa). | Must be compatible with cuvettes or strips for the cell type being used. |

| Microinjection System | Comprises a microscope, micromanipulator, and microinjector for precise delivery. | Used for pronuclear or cytoplasmic injection in zygotes and large cells [32]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (SPIONs) | Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, often coated (e.g., with gelatin), for magnetofection. | Used to deliver RNP complexes; enables efficient uptake but may face post-entry barriers [29]. |

| Platform Magnet | Creates a magnetic field to pull nanoparticle complexes onto cultured cells. | Critical for achieving localized and efficient delivery in magnetofection protocols. |

Electroporation, microinjection, and magnetofection are powerful physical methods for delivering the CRISPR-Cas9 system, each with a unique profile of efficiency, viability, and applicability. Electroporation stands out for high-throughput and high-efficiency editing, microinjection for unparalleled precision in single-cell applications, and magnetofection for its potential for high viability and targeted delivery. The choice of method is not one-size-fits-all and must be informed by the target cell type, the desired cargo format, and the specific experimental goals. As the field of gene editing advances, continued optimization of these physical protocols will be crucial for unlocking the full potential of CRISPR-based research and therapies.

The therapeutic potential of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing is fundamentally constrained by the availability of safe and efficient delivery vehicles. Viral vectors, while efficient, raise concerns regarding immunogenicity, cargo limitations, and long-term persistence. Consequently, extracellular vesicles (EVs) and virus-like particles (VLPs) have emerged as promising non-viral platforms that combine favorable delivery characteristics with enhanced safety profiles [33] [9]. This application note details the latest protocols and quantitative performance data for EV and VLP-mediated CRISPR-Cas9 delivery, providing researchers with practical methodologies for implementing these platforms in gene editing applications.

EVs are biological nanoparticles that play a key role in intercellular communication, while VLPs are engineered nanostructures that mimic viral architecture without containing viral genetic material [7] [34]. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of recently developed EV and VLP platforms for CRISPR-Cas9 delivery.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Recent EV and VLP Platforms for CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery

| Platform & Study | Cargo Type | Loading Strategy | Target Application | Editing Efficiency (Key Metric) | Notable Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modular EV [7] | Cas9 RNP, ABE8e, dCas9-VPR | MS2 aptamer/MCP fusion to CD63 + UV-cleavable linker | Genetic engineering & transcriptional regulation | ~270-fold increase in sgRNA loading | Modular; applicable to multiple Cas9 variants |

| ARMMs [35] | Cas9 RNP | Direct ARRDC1-Cas9 fusion | APP gene editing in neuronal cells (Alzheimer's model) | Significant reduction in amyloid peptides | Efficient packaging and budding |

| Myristoylated-EV [36] | Cas9 RNP | N-myristoylation of Cas9 protein | Androgen receptor silencing in prostate cancer | Attenuated cancer cell proliferation | Enhanced RNP encapsulation |

| RIDE VLP [33] | Cas9 RNP | Engineered enveloped VLP | Ocular & Huntington's disease models | Robust, localized editing in immune-privileged sites | Cell-selective targeting; low immunogenicity |

| SFV-based VLP [37] | mRNA, Protein, RNP | Fusion to truncated capsid protein | Broad in vitro delivery (including hard-to-transfect cells) | Dose-dependent indel formation | Programmable tropism; large cargo capacity (~10 kb) |

| eVLPs for wet AMD [38] | Cas9 RNP (anti-VEGFA) | MMLVgag–3xNES–Cas9 fusion | Vegfa knockout in mouse retinal pigment epithelium | Up to 99% indel in vitro; 16.7% in vivo | Efficient RNP delivery to retinal tissue |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the general experimental process for developing and utilizing these platforms, from initial engineering to functional validation.

Detailed Protocols for EV-Mediated CRISPR Delivery

Modular EV Platform via Aptamer-Based Loading

This protocol describes a versatile strategy for loading Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes into EVs using high-affinity RNA aptamers, allowing for the delivery of various CRISPR effectors without direct fusion to EV membrane proteins [7].

Key Reagents:

- Plasmids: Expression vectors for MCP-CD63 fusion protein, Cas9 (or variants), and MS2-sgRNA.

- Cells: HEK293T cells for EV production.

- Buffers: Standard cell culture and purification buffers.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Producer Cell Transfection: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with plasmids expressing the MCP-CD63 loading construct, the desired Cas9 variant, and the MS2-sgRNA using a standard transfection reagent. The MS2 aptamers are incorporated into the tetraloop and second stem-loop of the sgRNA.

- EV Biogenesis and Loading: Incubate cells for 48 hours to allow for intracellular RNP formation and loading into budding EVs via the MCP-MS2 interaction.

- EV Harvest and Purification: Collect conditioned media and isolate EVs using a two-step purification process:

- Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) to concentrate the vesicles.

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) to separate EVs from protein contaminants.

- Cargo Release Activation (Optional): For constructs containing a UV-cleavable linker (e.g., PhoCl), expose isolated EVs to UV light to release the RNP cargo from the EV membrane upon internalization.

- Validation: Confirm EV isolation and Cas9 loading via Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA), Western Blot (for CD63, ALIX, TSG101, and Cas9), and qPCR/ddPCR for sgRNA quantification.

Typical Results: This method yields EVs with a mode size of ~75 nm and demonstrates a significant enrichment of Cas9 protein (~270-fold increase in sgRNA) compared to controls without the MCP-CD63 construct [7].

ARMMs for Neuronal Gene Editing

This protocol utilizes Arrestin Domain-Containing Protein 1-Mediated Microvesicles (ARMMs) for packaging and delivering CRISPR-Cas9, showing high efficiency in editing neuronal cells [35].

Key Reagents:

- Plasmids: Expression vectors for ARRDC1-Cas9 fusion (full-length or shortened sARRDC1) and VSV-G.

- Cells: Appropriate producer cell line (e.g., HEK293T) and target neuronal cells (e.g., for APP gene editing).

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Fusion Construct Design: Generate fusion constructs where Cas9 is directly fused to the C-terminus of ARRDC1 (or sARRDC1). Co-express VSV-G to enhance ARMMs budding and Cas9 encapsulation.

- Particle Production: Transfect producer cells with the ARRDC1-Cas9 and VSV-G plasmids.

- ARMMs Collection and Purification: Collect particles from the conditioned media 48-72 hours post-transfection and purify using standard EV isolation techniques.

- Target Cell Transduction: Apply purified ARMMs to target neuronal cells (e.g., for APP gene editing in an Alzheimer's model).