CRISPR Screening in Mammalian Cells: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of CRISPR screening technologies in mammalian systems, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

CRISPR Screening in Mammalian Cells: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of CRISPR screening technologies in mammalian systems, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of CRISPR-Cas9 systems and screening modalities (CRISPRko, CRISPRi, CRISPRa), explores methodological approaches including pooled versus arrayed screens and functional assays, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for challenging cell models, and validates findings through comparative analysis with orthogonal technologies and advanced bioinformatics. The content synthesizes current advancements to equip researchers with practical knowledge for designing robust screening campaigns that accelerate therapeutic discovery.

Understanding CRISPR Screening: Core Principles and System Selection

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) system represents a transformative technology derived from a prokaryotic adaptive immune system. In bacteria, this mechanism detects and eliminates foreign genetic elements by integrating short sequences from invading viruses into the host genome, which then guide Cas nucleases to cleave homologous viral DNA upon re-infection [1]. Scientists have repurposed this two-component system—consisting of a guide RNA (gRNA) and a Cas nuclease—into a versatile genome engineering tool that has rapidly surpassed earlier technologies like zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) due to its simplicity, scalability, and adaptability [1]. This application note details the core mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas9 and provides detailed protocols for its application in mammalian genome editing, framed within the context of CRISPR screening for functional genomics.

Core Mechanisms and System Components

Molecular Machinery of CRISPR-Cas9

The engineered CRISPR system requires two fundamental components: a CRISPR-associated endonuclease (most commonly Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes) and a guide RNA (gRNA or sgRNA). The gRNA is a short synthetic RNA composed of a constant scaffold sequence necessary for Cas-binding and a user-defined ~20-nucleotide spacer sequence that specifies the genomic target through complementary base-pairing [1]. The ability to redirect the Cas nuclease to any genomic locus simply by modifying the targeting sequence within the gRNA constitutes the foundational simplicity and power of the technology [1].

The genomic target for Cas9 can be any ~20 nucleotide DNA sequence, provided it meets two essential conditions: 1) the sequence is unique compared to the rest of the genome to minimize off-target effects, and 2) the target is present immediately adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [1]. For the commonly used SpCas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where 'N' is any nucleotide. This requirement ensures the nuclease distinguishes between self and non-self DNA in its native bacterial context [1] [2].

The mechanism proceeds through several critical steps. First, the gRNA and Cas9 protein form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. gRNA binding induces a conformational change in Cas9, shifting it into an active DNA-binding configuration [1]. As Cas9 scans the genome, the spacer sequence of the gRNA attempts to anneal to potential DNA targets. The seed sequence (8–10 bases at the 3' end of the gRNA targeting sequence) initiates annealing to the target DNA; if perfect complementarity exists in this region, annealing continues in a 3' to 5' direction [1]. Upon successful recognition of a target sequence followed by the correct PAM, Cas9 undergoes a second conformational change that activates its nuclease domains (RuvC and HNH), which cleave opposite strands of the target DNA. This results in a double-strand break (DSB) located ~3–4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [1].

DNA Repair Pathways and Editing Outcomes

Cellular repair of the CRISPR-induced DSB occurs primarily through two endogenous pathways, each yielding distinct genetic outcomes:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An efficient but error-prone repair pathway that directly ligates break ends without a homologous template. NHEJ frequently introduces small insertion or deletion mutations (indels) at the DSB site. When targeted to open reading frames, these indels often cause frameshift mutations leading to premature stop codons, effectively disrupting gene function and generating knockouts [1] [2].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A less efficient but high-fidelity pathway that uses a homologous DNA template to accurately repair the break. By co-delivering a designed donor DNA template with sequence homology to the target region, researchers can harness HDR to introduce precise genetic modifications, including specific nucleotide changes or insertion of reporter genes [2].

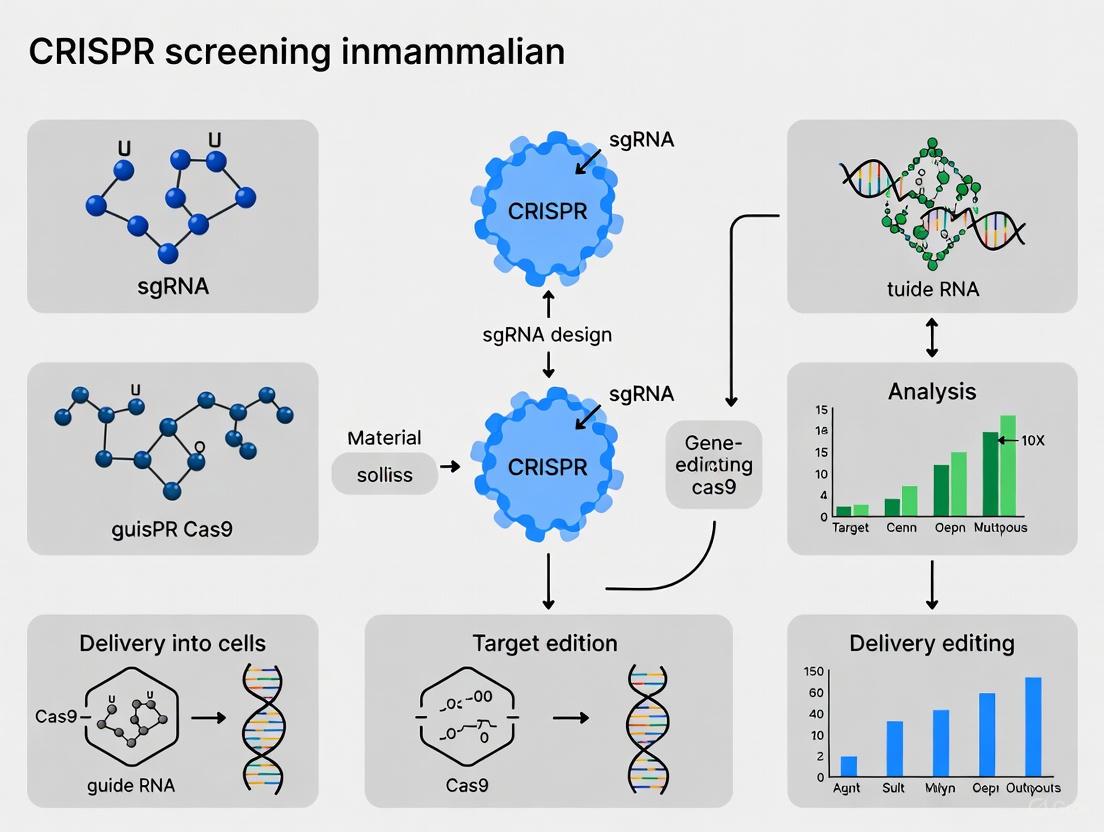

Figure 1: Core CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism. The Cas9 enzyme and guide RNA form a ribonucleoprotein complex that creates a double-strand break at DNA targets adjacent to a PAM sequence. Cellular repair pathways then generate either knockout or precise editing outcomes.

Advanced CRISPR Tool Development

Engineered Cas Variants for Enhanced Functionality

The native SpCas9 system has been extensively engineered to overcome limitations in specificity, targeting range, and functionality, yielding specialized variants for advanced applications:

High-Fidelity Cas9s were developed to reduce off-target effects while maintaining robust on-target activity. These include eSpCas9(1.1) (weakened interactions with non-target DNA strand), SpCas9-HF1 (disrupted interactions with DNA phosphate backbone), HypaCas9 (increased proofreading), evoCas9, and Sniper-Cas9 [1].

PAM-Flexible Cas9s address the constraint imposed by the NGG PAM requirement. Variants like xCas9 (recognizes NG, GAA, and GAT PAMs), SpCas9-NG (NG PAM), SpG (NGN PAM), and SpRY (NRN/NYN PAM) significantly expand the targetable genomic landscape [1].

Specialized Function Cas Enzymes enable diverse applications beyond simple DSB generation. Catalytically inactive "dead" Cas9 (dCas9), created through D10A and H840A mutations, binds DNA without cleavage and serves as a programmable DNA-binding platform for fusing effector domains including transcriptional activators, repressors, epigenetic modifiers, and base editors [1]. Cas9 nickase (Cas9n), a D10A mutant with one active nuclease domain, generates single-strand breaks rather than DSBs and can be used in paired configurations to enhance specificity [1].

Table 1: Engineered Cas9 Variants and Their Applications

| Cas Variant | Key Properties | Primary Applications | PAM Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type SpCas9 | Standard nuclease activity, NGG PAM | Gene knockout, screening | NGG |

| High-Fidelity (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) | Reduced off-target effects | Therapeutic applications, sensitive genetic screens | NGG |

| PAM-Flexible (e.g., xCas9) | Expanded targeting range | Targeting gene deserts, precise editing | NG, GAA, GAT |

| Cas9 Nickase (nCas9) | Single-strand DNA nicking | Paired nicking for enhanced specificity | NGG |

| dCas9 | Catalytically inactive | Transcriptional regulation, epigenome editing | NGG |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Different nuclease architecture, T-rich PAM | Multiplexed editing, AT-rich targets | TTTN |

CRISPR Screening Platforms

The scalability of gRNA design has enabled genome-wide CRISPR screening, an powerful approach for unbiased functional genomics. In pooled screening formats, libraries containing thousands to hundreds of thousands of gRNAs are delivered to populations of cells, followed by selection pressures and high-throughput sequencing to identify gRNAs that become enriched or depleted under specific conditions [3] [4]. Recent advances have extended this technology from in vitro models to in vivo contexts, enabling genetic dissection in physiologically relevant environments [3].

Key considerations for genome-wide screening include achieving sufficient library coverage (traditionally 250× coverage per sgRNA), ensuring efficient delivery to target cells, and implementing appropriate phenotypic selections [3]. For in vivo screens, delivery remains a significant challenge, with lentiviral vectors, adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), and non-viral methods like transposon systems each offering distinct advantages and limitations for different tissue types [3].

Figure 2: Genome-wide CRISPR Screening Workflow. The process involves designing a comprehensive sgRNA library, delivering it to target cells, applying phenotypic selection, and identifying hits through next-generation sequencing.

Application Notes: Genome-Wide Screening in Primary Human NK Cells

Experimental Platform and Workflow

The PreCiSE platform enables genome-wide CRISPR screening in primary human natural killer (NK) cells, overcoming previous technical challenges in editing these difficult-to-transfect immune cells [5]. The optimized protocol involves:

Primary Human NK Cell Isolation and Expansion: NK cells are isolated from cord blood and expanded with engineered universal antigen-expressing feeder cells (uAPCs) plus IL-2 (200 IU/ml) [5].

Retroviral Library Delivery: A genome-wide sgRNA library (77,736 sgRNAs targeting 19,281 genes with 500 non-targeting controls) is delivered via retroviral transduction at low multiplicity of infection (MOI) to ensure single-copy integration [5].

Cas9 Protein Electroporation: Cells are electroporated with Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes to ensure efficient editing while minimizing persistent Cas9 expression that could increase off-target effects [5].

Functional Validation: Successful editing is confirmed through targeted ablation of the NK cell surface marker PTPRC (CD45), achieving 90.1% ± 0.1% loss of CD45 expression versus 0% in Cas9 mock-electroporated controls [5].

Phenotypic Selection: Edited NK cells undergo three sequential challenges with pancreatic cancer cells (Capan-1) at an effector-to-target ratio of 1:1 to model tumor-induced dysfunction, with phenotypic assessment via CD107a (LAMP1) degranulation marker expression and spectral flow cytometry [5].

Key Findings and Therapeutic Implications

This screening approach identified several critical regulators of NK cell antitumor activity. Transcription factor screening targeting 1,632 TFs with 11,364 unique guides revealed PRDM1 (Blimp-1) and RUNX3 as key transcriptional regulators that suppress NK cell proliferation and antitumor response [5]. Genome-wide screening further identified MED12, ARIH2, and CCNC as critical checkpoints whose ablation significantly improved NK cell antitumor activity against multiple treatment-refractory human cancers both in vitro and in vivo [5].

Mechanistically, ablation of these targets enhanced both innate and CAR-mediated NK cell function through improved metabolic fitness, increased proinflammatory cytokine secretion, and expansion of cytotoxic NK cell subsets [5]. Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of patient samples confirmed elevated PRDM1 and RUNX3 expression in tumor-infiltrating NK cells compared to healthy donors, validating their clinical relevance as potential therapeutic targets [5].

Essential Protocols for Mammalian Genome Editing

sgRNA Design and Validation

Successful genome editing begins with careful sgRNA design, which largely determines both on-target efficiency and off-target specificity [2]. The following protocol outlines best practices:

Target Site Selection: Identify 20-nucleotide target sequences immediately 5' of an NGG PAM sequence using established bioinformatic tools (e.g., CHOPCHOP, CRISPR Design Tool). Prioritize targets with high predicted on-target activity scores and minimal off-target potential based on seed sequence uniqueness [2].

Specificity Considerations: Select target sequences with minimal homology to other genomic regions, especially in the seed region (8-12 bases proximal to PAM). Mismatches in this region most effectively reduce off-target cleavage [1].

Experimental Validation: For critical applications, validate sgRNA efficiency using in vitro cleavage assays prior to cellular experiments. Clone sgRNA into expression vectors, transcribe in vitro, incubate with Cas9 protein and target DNA plasmid, and assess cleavage efficiency by gel electrophoresis [2].

Vector Selection: For knockout screens, clone validated sgRNAs into lentiviral vectors enabling co-expression with Cas9 and selection markers. For therapeutic applications, consider high-fidelity Cas9 variants to minimize off-target effects [1] [2].

CRISPR Delivery Methods for Mammalian Cells

Table 2: Comparison of CRISPR Delivery Methods

| Delivery Method | Targetable Cell Types | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral Vectors | Dividing cells, some primary cells (hepatocytes, CNS with injection) | Stable sgRNA integration, large packaging capacity (8-10 kb) | Difficult for most extrahepatic sites, insertional mutagenesis risk |

| AAV Vectors | Liver, CNS, T cells, muscle, broader tropism | Low immunogenicity, clinical experience | Small packaging capacity (5-6 kb), episomal (transient without transposon) |

| Electroporation (RNP) | Primary immune cells, stem cells, difficult-to-transfect cells | Rapid editing, reduced off-targets, no vector DNA | Limited to ex vivo applications, optimization required |

| Hydrodynamic Injection + Transposon | Hepatocytes in vivo | Efficient liver delivery, stable expression | Limited to hepatic delivery, requires specialized equipment |

Protocol: Pooled CRISPR Screening in Primary Human Cells

This protocol adapts the PreCiSE platform for genome-wide screening in primary human immune cells [5]:

Day 1: Cell Preparation

- Isolate primary NK cells from cord blood or peripheral blood.

- Begin expansion using irradiated uAPCs at 1:1 ratio in complete media supplemented with IL-2 (200 IU/ml).

- Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

Day 5: Library Transduction

- Harvest expanded NK cells, count, and assess viability (>90% required).

- Transduce cells with retroviral sgRNA library at MOI <0.3 to ensure single integration events.

- Centrifuge at 1000 × g for 90 minutes at 32°C (spinoculation).

- Resuspend in fresh media with IL-2 and return to incubator.

Day 6: Cas9 Electroporation

- Harvest transduced cells and electroporate with Cas9 RNP complex using optimized pulse codes.

- Include non-electroporated controls to assess transduction efficiency.

- Recover cells in pre-warmed media with IL-2.

Day 7: Selection and Expansion

- Begin puromycin selection (concentration optimized for cell type) to eliminate non-transduced cells.

- Continue expansion with uAPCs and IL-2.

- Monitor viability and cell counts daily.

Days 14-28: Phenotypic Selection

- Subject edited cells to relevant biological challenge (e.g., tumor cell co-culture, cytokine deprivation, drug treatment).

- For exhaustion models, perform sequential tumor challenges at 1:1 effector:target ratio.

- Harvest cells for genomic DNA extraction and flow cytometry analysis at multiple time points.

Sample Processing and Sequencing

- Extract genomic DNA using silica column-based methods.

- Amplify integrated sgRNA sequences with barcoded primers for multiplexing.

- Perform next-generation sequencing (Illumina platform recommended).

- Analyze sequencing data using established pipelines (MAGeCK, PinAPL-Py) to identify significantly enriched or depleted sgRNAs.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Systems | SpCas9, HiFi Cas9, dCas9-VP64, dCas9-KRAB | Core nuclease function; high-fidelity variants reduce off-targets; dCas9 fusions for transcriptional regulation |

| Delivery Vehicles | VSVG-pseudotyped lentivirus, AAV6/8/9, electroporation equipment | Introduce CRISPR components into target cells; choice depends on cell type and application |

| sgRNA Libraries | Genome-wide (Brunello, GeCKO), focused (kinase, TF), custom libraries | Collections of sgRNAs for specific screening applications; include non-targeting controls |

| Cell Culture Reagents | IL-2 for NK cells, recombinant cytokines, uAPCs, serum-free media | Support growth and function of primary cells during screening |

| Selection Agents | Puromycin, blasticidin, fluorescent markers (GFP) | Enumerate for successfully transduced cells |

| Analysis Tools | NGS platforms, flow cytometers, bioinformatics software (MAGeCK) | Assess editing efficiency and screen outcomes |

Safety Considerations and Technical Challenges

Despite its transformative potential, CRISPR-Cas9 technology presents important safety considerations that must be addressed, particularly for clinical applications. Beyond well-documented off-target effects at sites with sequence similarity to the intended target, recent studies reveal more substantial concerns regarding on-target structural variations [6]. These include large kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions, chromosomal translocations, and other complex rearrangements that may escape detection by standard short-read sequencing methods [6].

Particular concern arises from strategies to enhance homology-directed repair efficiency through inhibition of DNA-PKcs, a key NHEJ pathway component. The DNA-PKcs inhibitor AZD7648, while promoting HDR, has been shown to dramatically increase frequencies of megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations—in some cases by thousand-fold [6]. These findings highlight the complex trade-offs between editing efficiency and genomic integrity, emphasizing the need for comprehensive genotoxicity assessment in therapeutic development.

Figure 3: CRISPR Safety Considerations. Beyond intended edits, CRISPR can induce various unintended structural variations. Some enhancement strategies exacerbate these risks, necessitating appropriate mitigation approaches.

Risk mitigation strategies include using high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., HiFi Cas9), paired nickase systems, and implementing comprehensive genomic integrity assessment methods capable of detecting large structural variations (e.g., CAST-Seq, LAM-HTGTS) [6]. For therapeutic applications, careful consideration should be given to whether HDR enhancement is truly necessary, as selective advantages of corrected cells or moderate editing efficiencies may suffice for clinical benefit without introducing unnecessary genotoxic risk [6].

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has evolved from a bacterial immune mechanism into an extraordinarily versatile platform for mammalian genome engineering. Its application in large-scale screening approaches continues to reveal novel biological insights and therapeutic targets across diverse cellular contexts and disease states. The protocols and application notes detailed here provide a framework for implementing these technologies while acknowledging both their transformative potential and important technical limitations. As the field advances, continued refinement of editing specificity, delivery efficiency, and safety assessment will further expand the research and therapeutic applications of this powerful technology.

Class 2 CRISPR systems, characterized by their single effector protein, have revolutionized genetic engineering and functional genomics. Within this class, Type II (Cas9) and Type V (Cas12) systems have become indispensable tools for unraveling gene function in mammalian cells [7]. Their programmability and precision have made them particularly valuable for pooled genetic screens, enabling the systematic identification of genes involved in health, disease, and therapeutic response [8]. The core innovation lies in the RNA-guided nature of these effectors; a customizable guide RNA (gRNA) directs the Cas protein to a specific genomic locus or nucleic acid sequence for cleavage or binding. This review details the molecular architectures, comparative capabilities, and practical application of these systems within the context of modern CRISPR screening, providing a foundational resource for researchers embarking on functional genetic studies.

Molecular Mechanisms and System Comparisons

Core Mechanisms of Cas9 and Cas12

The Type II CRISPR system, centered on the Cas9 protein, functions as a bilobed structure composed of a recognition (REC) lobe and a nuclease (NUC) lobe [7]. Its activity requires two nuclease domains: the HNH domain, which cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the guide RNA, and the RuvC domain, which cleaves the non-complementary strand [7]. This results in a blunt-ended double-strand break (DSB) three nucleotides upstream of the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), which for the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 is a 5'-NGG-3' sequence [7]. The system relies on a single guide RNA (sgRNA) that fuses the functions of the endogenous crRNA and tracrRNA.

In contrast, Type V effectors like Cas12a (also known as Cpf1) possess a single RuvC-like nuclease domain responsible for cleaving both DNA strands [9]. This results in a staggered double-strand break with a 5' overhang [9]. A key differentiator of Cas12a is its PAM requirement; it typically recognizes a 5'-TTTN-3' PAM, which is richer in adenine and thymine compared to the GC-rich Cas9 PAM [9] [10]. Furthermore, upon recognizing and cleaving its target double-stranded DNA (cis-cleavage), Cas12a exhibits transient collateral activity, non-specifically cleaving surrounding single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) [9]. This trans-cleavage activity is the foundation for many diagnostic applications.

Comparative Analysis of Class 2 CRISPR Systems

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of Cas9 and Cas12, highlighting their distinctions and respective advantages.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Type II (Cas9) and Type V (Cas12) CRISPR Systems

| Feature | Type II (Cas9) | Type V (Cas12a) |

|---|---|---|

| Effector Protein | Cas9 | Cas12a (Cpf1), Cas12f1 |

| PAM Sequence | 5'-NGG-3' (GC-rich) [7] | 5'-TTTN-3' (AT-rich) [9] [10] |

| Guide RNA | Single guide RNA (sgRNA) [7] | CRISPR RNA (crRNA) [9] |

| Cleavage Mechanism | Dual HNH & RuvC domains [7] | Single RuvC domain [9] |

| Cleavage Pattern | Blunt ends [7] | Staggered ends with 5' overhang [9] |

| Collateral Activity | No | Yes (ssDNA trans-cleavage) [9] |

| Primary Screening Applications | Gene knockout (CRISPRn), Interference (CRISPRi), Activation (CRISPRa) [8] | Gene knockout, diagnostics (e.g., DETECTR) [9] [10] |

Recent studies have further expanded the CRISPR toolbox. For instance, the much smaller size of Cas12f1 (half the size of Cas9) facilitates easier delivery, while CRISPR-Cas3 has been shown to achieve high eradication efficiency of antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial models, though its application in mammalian cells is less common [10].

Application Notes for CRISPR Screening in Mammalian Cells

CRISPR Knockout (CRISPRn), Interference (CRISPRi), and Activation (CRISPRa)

Beyond simple knockout screens, modified CRISPR systems allow for reversible and tunable control of gene expression, which is invaluable for dissecting gene function.

- CRISPRn (Nuclease): The wild-type Cas9 introduces DSBs, which are repaired by error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), often resulting in frameshift mutations and gene knockout [8]. This is ideal for identifying essential genes and loss-of-function phenotypes.

- CRISPRi (Interference): A catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) is fused to repressive domains like the KRAB domain. This complex binds to the promoter or coding region of a target gene without cutting the DNA, recruiting chromatin-modifying proteins to silence transcription [8]. CRISPRi is highly specific and reversible, making it suitable for studying essential genes.

- CRISPRa (Activation): The same dCas9 is fused to transcriptional activators (e.g., VP64, p65, Rta) to recruit RNA polymerase and co-activators, leading to targeted gene overexpression [8]. Advanced systems like the SunTag or SAM use scaffold strategies to recruit multiple activator molecules, significantly potentiating gene expression [8].

Pooled CRISPR Screening Workflow

Pooled CRISPR screens are a powerful, unbiased method for discovering genes involved in a biological process of interest across the entire genome.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Pooled CRISPR Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Library | Pooled collection of lentiviral transfer plasmids, each encoding a unique sgRNA. | Genome-wide libraries typically contain 4-6 sgRNAs per gene and require high coverage (e.g., 250x per sgRNA) [3]. |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Delivery vehicle for stably integrating the sgRNA and Cas transgene into the host cell genome. | Often pseudotyped with VSVG glycoprotein; crucial for achieving high infection efficiency [8] [3]. |

| Cas9-Expressing Cells | Mammalian cell line engineered to constitutively or inducibly express the Cas9 nuclease. | Using stable cell lines simplifies screening by reducing the number of genetic elements to deliver [3]. |

| Selection Antibiotics | To select for successfully transduced cells. | e.g., Puromycin, Blasticidin. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platform | To quantify sgRNA abundance before and after selection. | Determines which sgRNAs are enriched or depleted under selective pressure [8]. |

The generalized workflow for a pooled negative selection (drop-out) screen is as follows:

Step 1: Library Design and Cloning. A pooled sgRNA library is designed, typically targeting each gene with multiple sgRNAs to ensure robustness. The library is cloned into a lentiviral transfer plasmid [8] [4]. Step 2: Lentivirus Production. The plasmid library is used to produce lentiviral particles in a packaging cell line (e.g., HEK293T). Step 3: Cell Transduction. A culture of Cas9-expressing mammalian cells is transduced with the lentiviral library at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive only one sgRNA. Cells are then selected with antibiotics to generate a representationally stable screening pool [8]. Step 4: Phenotypic Selection. The pooled cell population is divided and subjected to a biological challenge (e.g., drug treatment, viral infection) over multiple generations. A reference sample is harvested at the start (T0), and the experimental group is harvested after the challenge (T-final) [8] [4]. Step 5: Sequencing and Quantification. Genomic DNA is extracted from both T0 and T-final populations. The integrated sgRNA sequences are PCR-amplified and quantified via NGS to determine the relative abundance of each sgRNA [8]. Step 6: Bioinformatic Analysis. Depletion or enrichment of specific sgRNAs in the T-final sample relative to T0 is calculated using specialized tools (e.g., MAGeCK). Statistically significant hits indicate genes that confer sensitivity or resistance to the applied challenge [4].

Detailed Protocol: A Pooled CRISPR-KO Screen for Drug Resistance Genes

This protocol outlines the steps to identify genetic modifiers of sensitivity to a drug-like compound in a human cell line, a common application in chemical biology and drug target discovery [8].

Pre-Screen Preparation

- Cell Line: Obtain a human cancer cell line (e.g., K562, A375) expressing Cas9 under a constitutive promoter.

- sgRNA Library: Select a genome-wide CRISPR knockout library (e.g., Brunello or Brie library).

- Reagents: Prepare DMEM or RPMI-1640 culture media, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin, polybrene (8 µg/mL), puromycin, and the drug compound of interest.

Screen Execution

- Library Transduction:

- Day 0: Seed 200 million Cas9-expressing cells in a large flask.

- Day 1: Replace medium with fresh medium containing 8 µg/mL polybrene. Add the lentiviral sgRNA library at an MOI of 0.3, ensuring >500x coverage of the library (e.g., for a 100,000 sgRNA library, transduce at least 50 million cells). Mix gently and culture for 24 hours.

- Selection of Transduced Cells:

- Day 3: Replace the medium with fresh medium containing the appropriate selection antibiotic (e.g., 2 µg/mL puromycin). Continue selection for 5-7 days until >90% of non-transduced control cells are dead.

- Phenotypic Challenge:

- Day 10: Harvest the pooled, selected cells. Count the cells and split into two arms:

- Control Arm: Culture cells in standard medium. Harvest 50 million cells as the T0 reference point. Continue culturing the rest, maintaining a minimum of 500x library coverage at all times.

- Treatment Arm: Culture cells in medium containing the IC50-IC80 concentration of the drug compound. Culture both arms for 3-4 weeks, passaging cells every 2-3 days to maintain log-phase growth.

- Day 10: Harvest the pooled, selected cells. Count the cells and split into two arms:

- Sample Harvest and Sequencing:

- After ~14 population doublings, harvest 50 million cells from both the Control and Treatment arms. Extract genomic DNA using a maxi-prep kit. Perform a two-step PCR to amplify the integrated sgRNA cassettes from the genomic DNA and attach Illumina sequencing adapters and barcodes. Pool the PCR products and perform NGS on an Illumina platform to a depth of 5-10 million reads per sample.

Post-Screen Analysis

- sgRNA Count Quantification: Use a tool like

MAGeCK countto align the NGS reads to the library reference and generate a count table for each sgRNA in the T0, final Control, and final Treatment samples. - Hit Identification: Run

MAGeCK testto compare sgRNA abundances between the Treatment and Control arms. Genes enriched in the Treatment arm (with multiple sgRNAs showing significant positive scores) are resistance hits, suggesting their knockout confers survival advantage. Genes depleted in the Treatment arm are sensitivity hits, suggesting they are essential for survival under drug pressure [8] [4]. - Validation: Top candidate genes must be validated using individual sgRNAs in a low-throughput format and orthogonal assays (e.g., Western blot, RT-qPCR) to confirm the phenotype.

The strategic application of Class 2 CRISPR systems, particularly Cas9 and Cas12, has fundamentally advanced our capacity for functional genomic screening in mammalian cells. The choice between systems depends on the experimental goal: Cas9-based knockout, interference, and activation screens remain the gold standard for probing gene function, while Cas12 variants offer advantages in diagnostics and specific targeting contexts. As the field progresses, the integration of artificial intelligence for guide RNA design and outcome prediction, alongside improvements in delivery technologies like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), is poised to further enhance the efficiency, precision, and safety of these powerful tools [11] [12]. By following the detailed protocols and understanding the comparative strengths outlined in this article, researchers can effectively leverage these systems to uncover novel biological mechanisms and therapeutic targets.

CRISPR-based screening technologies have revolutionized functional genomics in mammalian cells, providing researchers with a powerful toolkit to systematically interrogate gene function. While the foundational CRISPR-Cas9 system enables permanent gene knockout, advanced derivatives known as CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) offer sophisticated temporal control over gene expression. CRISPRi achieves targeted gene repression without altering the DNA sequence, whereas CRISPRa enables precise transcriptional activation. These three modalities—Knockout (ko), Interference (i), and Activation (a)—each possess distinct mechanisms and applications that make them uniquely suited for different biological questions in basic research and drug discovery. This article delineates the operational principles, experimental protocols, and practical considerations for implementing these technologies in genetic screens, providing a comprehensive resource for scientists engaged in mammalian cell research.

Molecular Mechanisms and Comparative Profiles

The functional diversity of CRISPR screening modalities stems from engineered variations of the core CRISPR-Cas9 system, primarily through modifications to the Cas9 nuclease and its associated effector domains.

CRISPR Knockout (CRISPRko) utilizes the wild-type Cas9 nuclease, which creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) in the DNA at sites specified by the guide RNA (gRNA). These breaks are primarily repaired by the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, often resulting in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the open reading frame and lead to permanent gene knockout [1].

CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) employs a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9), which lacks nuclease activity but retains DNA-binding capability. When targeted to a gene's promoter region, dCas9 alone can cause steric hindrance, blocking transcription. For more potent repression in mammalian cells, dCas9 is typically fused to a transcriptional repressor domain, such as the Krüppel associated box (KRAB), which recruits additional proteins to silence gene expression [13].

CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa) also uses dCas9 but is fused to transcriptional activator domains, such as VP64, p65, or the SunTag system. When guided to a gene's promoter or enhancer region, this complex recruits the cellular transcription machinery to drive gene expression, often achieving supra-physiological levels [13].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of these three modalities.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of CRISPR Screening Modalities

| Feature | CRISPR Knockout (ko) | CRISPR Interference (i) | CRISPR Activation (a) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Type | Wild-type (active nuclease) | dCas9 (catalytically dead) | dCas9 (catalytically dead) |

| Core Mechanism | DNA cleavage → NHEJ repair → Indels | Steric hindrance + recruitment of repressors | Recruitment of transcriptional activators |

| Genetic Outcome | Permanent gene knockout | Reversible gene knockdown | Tunable gene overexpression |

| Key Effector Domain | N/A | KRAB | VP64, p65, SunTag |

| Effect on Essential Genes | Lethal, precluding study | Enables study of hypomorphic phenotypes | Can reveal oncogenic potential |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanisms of action for each modality.

Experimental Protocols for Screening

Executing a successful CRISPR screen requires meticulous planning, from library design to data analysis. The following protocol outlines the key steps for a pooled negative selection screen to identify genes essential for cell growth, a common application for CRISPRko.

Workflow for a Pooled CRISPRko Screen

- Library Selection and Design: Choose a genome-wide or sub-library of sgRNAs targeting your genes of interest. A typical library uses 4-10 sgRNAs per gene, plus non-targeting control sgRNAs [14] [15]. The library is cloned into a lentiviral backbone.

- Lentiviral Production: Produce lentivirus containing the pooled sgRNA library in HEK293T cells. Determine the viral titer.

- Cell Transduction and Selection: Transduce your target mammalian cells (e.g., K562, HeLa) at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI ~0.3-0.5) to ensure most cells receive only one sgRNA. Select transduced cells with antibiotics (e.g., puromycin) for 5-7 days. This is the "Day 0" or "T0" timepoint.

- Screen Propagation and Harvest: Split the cell population into replicates and continue culturing for 2-4 weeks (e.g., Day 21, "T21") to allow depletion of cells carrying sgRNAs targeting essential genes.

- Genomic DNA (gDNA) Extraction and Sequencing: Harvest cells at T0 and T21. Extract gDNA and perform PCR amplification of the integrated sgRNA sequences using primers compatible with Illumina sequencing.

- Data Analysis: Sequence the PCR products and count the reads for each sgRNA. Use specialized algorithms (e.g., MAGeCK, casTLE) to compare sgRNA abundance between T0 and T21, identifying sgRNAs (and their target genes) that are significantly depleted or enriched [14] [16].

The workflow is visualized in the diagram below.

Critical Parameters for CRISPRi/a Screens

While the overall workflow for CRISPRi and CRISPRa screens is similar to CRISPRko, key differences must be considered:

- Cell Line Engineering: Stable cell lines expressing dCas9-KRAB (for CRISPRi) or dCas9-activator (for CRISPRa) must be generated and validated prior to the screen [16] [13].

- gRNA Design: sgRNAs for CRISPRi/a must be designed to bind to the promoter or transcriptional start site of the target gene, rather than the coding exon. This requires accurate annotation of promoter regions [13].

- Controls: Include non-targeting gRNAs and gRNAs targeting known essential and non-essential genes as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Performance and Application Data

The choice between CRISPRko, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa is dictated by the biological question. A systematic comparison revealed that CRISPRko and RNAi (a knockdown technology conceptually similar to CRISPRi) can identify distinct sets of essential genes, suggesting they reveal different aspects of biology [14]. Combining data from both knockout and knockdown/activation screens provides a more robust and comprehensive understanding of gene function.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance and Primary Applications

| Screening Modality | Typical Efficiency/Effect | Key Strengths | Ideal Screening Contexts |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRko | High knockout efficiency; Indels via NHEJ [1] | Permanent loss-of-function; Identifies fitness genes; Well-established analysis | Genome-wide loss-of-function; Identification of essential genes [14] |

| CRISPRi | Strong repression (up to 80-99%) with dCas9-KRAB [13] | Reversible; Tunable knockdown; Fewer off-targets vs. RNAi; Studies essential genes | Functional dissection of essential genes; Drug target validation [13] |

| CRISPRa | Strong activation with multi-domain systems (e.g., SunTag) [13] | Endogenous gene overexpression; Gain-of-function studies | Identifying drivers of drug resistance; Oncogene screening [15] [13] |

Case Study: Dual CRISPRko/CRISPRa Screen for Drug Resistance

A powerful application of these technologies is elucidating mechanisms of drug resistance. A 2020 study employed dual genome-wide CRISPR knockout and CRISPR activation screens to identify genes that regulate cellular resistance to ATR inhibitors (ATRi) in cancer cells [15].

- The CRISPRko screen identified genes whose loss confers resistance (e.g., MED12, KNTC1), potentially by disrupting pathways that promote cell death in response to ATR inhibition.

- The parallel CRISPRa screen identified genes whose overexpression drives resistance, pointing to potential mechanisms like enhanced DNA repair or suppression of apoptosis.

This dual approach provided a comprehensive landscape of genetic determinants of ATRi resistance, highlighting how KO and A screens can reveal complementary biological insights within the same study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of CRISPR screens relies on a core set of high-quality reagents. The following table lists essential components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function and Critical Notes |

|---|---|

| sgRNA Library | Pooled collection of guide RNAs; Critical for specificity. Arrayed synthetic libraries are recommended for high editing efficiency and low off-targets [17]. |

| Cas9 Enzyme | Wild-type for KO; Catalytically dead (dCas9) for i/a. High-fidelity variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) reduce off-target effects [1]. |

| Lentiviral Packaging System | For efficient delivery of CRISPR components into mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T cells, psPAX2, pMD2.G plasmids). |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Optimized media and supplements for the target mammalian cell line; Puromycin for selection post-transduction. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platform | For quantifying sgRNA abundance from genomic DNA of screen samples. Essential for deconvoluting results [18]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | Tools like MAGeCK [16] and casTLE [14] for statistical analysis of sgRNA enrichment/depletion. |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Even well-designed screens can face challenges. Below are common issues and recommended solutions.

Table 4: Common Technical Challenges and Solutions

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Screen Performance / Low Signal | Low viral titer; Ineffective delivery; Insensitive cell line. | Re-titer virus; Optimize delivery method (e.g., electroporation); Use a cell line with robust fitness phenotypes. |

| High False Positive/Negative Rate | Ineffective sgRNAs; Poor library coverage; Off-target effects. | Use validated library designs with multiple sgRNAs/gene; Maintain >500x library coverage during screening; Use bioinformatic tools to filter out common off-targets [1]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Modalities | Fundamental biological differences (knockout vs. knockdown); Technology-specific artifacts. | Combine data using statistical frameworks like casTLE [14]; Validate key hits with orthogonal assays (e.g., cDNA rescue). |

| Low Editing/Efficiency (CRISPRi/a) | Poor dCas9 expression; Inaccessible chromatin at target; Suboptimal gRNA design. | Validate dCas9 and effector expression; Use ATAC-seq data to inform target site selection; Design gRNAs to target nucleosome-free regions [13]. |

A significant consideration is the inherent heterogeneity in screening technologies. For example, a CRISPRko screen can generate a mixture of true knockouts, heterozygotes, and wild-type cells due to variable editing outcomes, which can influence the observed phenotype [14]. Acknowledging and accounting for this variability during data interpretation is crucial.

CRISPR-Cas9 has revolutionized functional genomics, enabling systematic perturbation of genes to uncover their functions in health and disease. For researchers and drug development professionals applying CRISPR screening in mammalian cells, a thorough understanding of three foundational components is critical: the design of guide RNAs (gRNAs), the constraints imposed by Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) requirements, and the decisive role of cellular DNA repair pathways. The PAM, a short DNA sequence adjacent to the target site, is an absolute requirement for Cas nuclease activity and serves as a recognition signal that licenses the Cas complex to cleave DNA [19] [20]. Following cleavage, cellular repair pathways—primarily non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR)—determine the mutational outcome, leading to either gene knockouts or precise edits [21]. This application note details the essential protocols and design principles for successful CRISPR screen design and analysis, framed within the context of mammalian cell research for drug target discovery.

Core Principles: PAM Sequences and Cellular Repair Pathways

The Critical Role of the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM)

The PAM is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) located directly adjacent to the DNA region targeted for cleavage by the CRISPR-Cas system. Its primary function is to allow the Cas nuclease to distinguish between self and non-self DNA, preventing the bacterial CRISPR system from attacking its own genome [19]. From a practical standpoint, the PAM is indispensable for CRISPR experiments because Cas nucleases will only interrogate a potential target site if the correct PAM is present. The Cas nuclease destabilizes the adjacent DNA sequence, allowing the guide RNA to pair with the matching target DNA [20]. The specific PAM sequence requirement depends entirely on the Cas nuclease used. For the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" can be any nucleotide base [19] [20]. This requirement means that every potential target site in the genome must be followed by a GG dinucleotide.

DNA Repair Pathways Determine Editing Outcomes

Once the Cas nuclease creates a double-strand break (DSB), the cell's innate DNA repair machinery takes over. The outcome of a CRISPR experiment is therefore dictated by which repair pathway is activated [21]. The two primary pathways are:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): This is the cell's dominant and error-prone repair pathway. NHEJ directly ligates the broken DNA ends, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels). When these indels occur within a protein-coding exon, they can cause frameshift mutations that lead to premature stop codons and effectively knock out the gene [22] [21]. NHEJ is the basis for most CRISPR knockout (CRISPRko) screens.

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): This is a more precise, but less frequent, pathway that functions in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle. HDR uses a DNA template—either a sister chromatid or an exogenously supplied donor DNA template—to repair the break accurately. In CRISPR experiments, researchers can co-deliver a designed donor template to direct specific edits, such as inserting a therapeutic gene or introducing a specific point mutation, in a process known as knock-in [21].

Table 1: Overview of DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR Genome Editing

| Pathway | Mechanism | Templates Required | Primary Outcome | Common CRISPR Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Direct ligation of broken ends | None | Error-prone, creates indels | Gene knockout (CRISPRko) |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | Uses homologous sequence as a template | Donor DNA template (endogenous or exogenous) | Precise edits | Gene knock-in, specific point mutations |

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision point after a Cas-induced double-strand break and the two primary repair pathways that determine the experimental outcome.

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR Screening

Protocol: A Workflow for Pooled CRISPR Knockout Screening

This protocol outlines the key steps for performing a pooled CRISPR knockout screen in mammalian cells to identify genes essential for cell viability or drug resistance, a common application in drug target discovery [22] [21].

gRNA Library Design and Cloning:

- Design: Select a genome-wide or focused gRNA library. Each gene is typically targeted by 4-6 gRNAs to ensure statistical robustness. The gRNA sequence (usually 20 nt) is designed to target an early exon of the gene and must be immediately 5' to a compatible PAM sequence (e.g., NGG for SpCas9) [19] [22].

- Cloning: The pooled oligonucleotide library is synthesized and cloned into a lentiviral gRNA expression vector. The vector also contains a selection marker (e.g., puromycin resistance).

Lentivirus Production and Cell Line Preparation:

- Virus Production: The lentiviral plasmid library is transfected into a packaging cell line (e.g., HEK293T) to produce lentiviral particles containing the gRNA library.

- Cell Line: A mammalian cell line (e.g., HeLa, HL-60) that stably expresses the Cas9 nuclease is generated or obtained. The Cas9 can be constitutively expressed or induced.

Library Transduction and Selection:

- Transduction: The target cells are transduced with the lentiviral library at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive only one gRNA. This achieves a coverage of 500-1000 cells per gRNA to maintain library representation.

- Selection: Cells are selected with an antibiotic (e.g., puromycin) for 3-5 days to eliminate untransduced cells, creating a stable pool of mutant cells.

Phenotypic Selection and Analysis:

- Experimental Arms: The selected cell pool is split into two groups: a control arm and a treatment arm (e.g., exposed to a drug candidate).

- Time Point: Cells are passaged for 2-3 weeks to allow for phenotypic enrichment (depletion of essential genes or enrichment of resistance genes).

- Genomic DNA (gDNA) Extraction: gDNA is extracted from both control and treatment populations at the end point.

Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Amplification and Sequencing: The integrated gRNA sequences are amplified from the gDNA by PCR and prepared for next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Analysis: NGS reads are aligned to the library reference. gRNA abundance is quantified and compared between treatment and control groups using specialized algorithms (e.g., MAGeCK) to identify significantly depleted or enriched gRNAs and their target genes [22].

The overall workflow for a typical pooled CRISPR screen, from library design to hit identification, is summarized below.

Protocol: Assessing Editing Outcomes with an eGFP-to-BFP Conversion Assay

This protocol provides a method to rapidly quantify and distinguish between NHEJ and HDR outcomes in a cell population, which is crucial for optimizing knock-in efficiency [23].

Generation of eGFP-Positive Reporter Cell Line:

- A mammalian cell line (e.g., HEK293) is stably transduced with a lentiviral construct expressing enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP). A clonal population with high, uniform eGFP expression is selected.

Design and Transfection of CRISPR Reagents:

- gRNA and Donor Template: Design a gRNA to target a region within the eGFP gene. Co-design a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) donor template encoding the mutations to convert eGFP to Blue Fluorescent Protein (BFP). The donor must contain homologous arms flanking the Cas9 cut site.

- Transfection: Transfect the eGFP-positive cells with the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex (Cas9 protein + gRNA) along with the ssODN donor template using a method suitable for the cell line (e.g., electroporation).

Cell Handling and Fluorescence Measurement:

- Incubation: Culture the transfected cells for 5-7 days to allow for expression of the edited protein.

- Flow Cytometry (FACS): Analyze the cells using a flow cytometer. Measure fluorescence in the FITC (green) and Pacific Blue (blue) channels.

Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- HDR Efficiency: The percentage of BFP-positive cells (successful HDR) is calculated from the total live cell population.

- NHEJ Efficiency: The percentage of eGFP-negative (non-fluorescent) cells indicates a successful knockout via NHEJ, provided the edits disrupt the eGFP reading frame.

- Editing Success: The remaining eGFP-positive, BFP-negative cells represent unedited cells or cells with in-frame NHEJ repairs that did not disrupt fluorescence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful execution of CRISPR screens relies on a suite of specialized reagents and computational tools for design, analysis, and validation.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Screening

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Products / Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease | Engineered endonuclease that creates DSB at target site. | SpCas9 (NGG PAM), SaCas9 (NNGRRT PAM), Cas12a/Cpf1 (TTTV PAM), High-fidelity variants (e.g., Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9) [19] [20] |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Synthetic RNA that directs Cas nuclease to specific genomic locus. | Chemically modified synthetic sgRNA (increases stability and efficiency), crRNA:tracrRNA complexes [20] |

| Lentiviral Vector | Efficient delivery system for gRNA library into mammalian cells. | Plasmids with U6 promoter for gRNA expression, antibiotic resistance markers (e.g., puromycin) |

| Donor Template | Provides homologous sequence for HDR-mediated precise editing. | Single-stranded ODNs (ssODNs), double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) donors with homology arms |

| Analysis Software | Computational tool to analyze NGS or Sanger data from editing experiments. | ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) for Sanger data, MAGeCK for NGS screen data [24] [22] |

Table 3: Key Bioinformatics Tools for CRISPR Screen Data Analysis

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Methodology | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAGeCK | Identifies enriched/depleted genes from CRISPR screens | Robust Rank Aggregation (RRA) on sgRNA counts [22] | Genome-wide dropout/sorting screens |

| BAGEL | Identifies essential genes using a Bayesian framework | Compares sgRNA abundance to a reference set of essential genes [22] | CRISPRko viability screens |

| ICE | Quantifies editing efficiency and indel profiles from Sanger data | Compares sequencing traces from edited vs. control samples [24] | Validation of editing in individual clones |

| CRISPhieRmix | Integrates multiple screens to improve hit identification | Hierarchical mixture model [22] | Meta-analysis of screening data |

| scMAGeCK | Links gene perturbations to transcriptomic phenotypes in single cells | RRA or linear regression on single-cell RNA-seq data [22] | Single-cell CRISPR screens (Perturb-seq) |

Advanced Applications: Expanding the Scope of CRISPR Screens

The core CRISPR-Cas9 system has been engineered to enable a diverse range of screening modalities beyond simple gene knockouts, greatly enhancing its utility in functional genomics and drug discovery [22] [21].

CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi): This system uses a catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) fused to a transcriptional repressor domain like KRAB. dCas9 binds to the DNA without cutting it, and KRAB silences the target gene. CRISPRi is ideal for studying essential genes, as it is reversible and creates hypomorphic rather than null alleles. It is also the preferred method for targeting non-coding elements like enhancers and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [22] [21].

CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa): This gain-of-function approach uses dCas9 fused to strong transcriptional activators (e.g., VP64, p65, SAM complex). By targeting the dCas9-activator to gene promoters, researchers can overexpress genes of interest. CRISPRa screens are powerful for identifying genes that confer drug resistance or that can rescue a disease phenotype [22] [21].

Single-Cell CRISPR Screens: Technologies like Perturb-seq and CROP-seq combine pooled CRISPR screening with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). This allows researchers to not only identify which genes are essential for a phenotype but also to observe the full transcriptomic consequences of each perturbation in individual cells, uncovering underlying regulatory networks [22].

Table 4: Overview of Advanced CRISPR Screening Modalities

| Screening Type | Core Machinery | Primary Genetic Effect | Key Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Knockout (CRISPRko) | Wild-type Cas9 | Permanent gene disruption via indels | Identify essential genes and drug targets [22] |

| CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) | dCas9-KRAB fusion | Reversible gene knockdown | Study essential genes and regulatory elements [22] [21] |

| CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa) | dCas9-activator fusion | Gene overexpression | Identify genes conferring resistance or therapeutic benefit [22] [21] |

| Single-Cell CRISPR Screens | Cas9 + scRNA-seq | Gene knockout with transcriptomic readout | Uncover gene networks and cellular heterogeneity in response to perturbation [22] |

Mastering the principles of guide RNA design, PAM requirements, and cellular repair pathways is fundamental to designing and executing successful CRISPR screens in mammalian cells. The continued diversification of Cas nucleases with novel PAM specificities expands the targetable genome, while sophisticated protocols and analytical tools enable precise dissection of gene function at scale. For researchers in drug development, these methodologies provide a powerful pipeline for the systematic identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets, accelerating the journey from gene discovery to clinical application. As CRISPR screening technologies evolve towards higher resolution in single cells and more physiologically relevant model systems, their impact on functional genomics and target discovery will only continue to grow.

The field of functional genomics has undergone a revolutionary transformation over the past decade, marked by a fundamental transition from RNA interference (RNAi)-based technologies to CRISPR-Cas9-based systems. This evolution has redefined our approach to understanding gene function, enabling unprecedented precision and scalability in genetic screening. Functional genomics aims to bridge the critical gap between genetic information and biological function by systematically perturbing genes and analyzing resulting phenotypic changes [25]. While RNAi technology provided the first scalable method for loss-of-function studies in mammalian cells, its limitations prompted the development of more robust approaches. The emergence of CRISPR-Cas9 as a programmable genome-editing tool has addressed many of these challenges, offering permanent gene disruption, higher specificity, and greater versatility in experimental design [26] [14]. This shift has been particularly transformative for drug discovery and therapeutic target identification, allowing researchers to systematically identify essential genes and drug-gene interactions with enhanced confidence and reproducibility [27]. The historical progression from RNAi to CRISPR represents not merely a technological improvement but a fundamental paradigm shift in how we interrogate gene function at scale.

Historical Background: From RNAi to CRISPR

The Era of RNA Interference (RNAi)

RNA interference emerged in the early 2000s as the first high-throughput technology for gene silencing in mammalian cells. The technology leverages a conserved endogenous pathway where introduced double-stranded RNAs trigger sequence-specific degradation of complementary mRNA molecules [26]. Several RNAi reagents were developed, including short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs), which could be delivered via viral transduction to achieve stable gene knockdown [26]. This approach enabled genome-scale loss-of-function screens that identified genes involved in various biological processes and disease states. The major advantages of RNAi included its ability to achieve partial knockdowns (potentially revealing phenotypes for essential genes) and its applicability to large-scale screening. However, significant limitations emerged: incomplete gene knockdown due to variable reagent efficiency, extensive off-target effects through miRNA-like deregulation, and high rates of false positives and false negatives that complicated data interpretation [26] [14]. These constraints highlighted the need for more precise and reliable perturbation technologies.

The CRISPR Revolution

The discovery of the CRISPR-Cas9 system and its development into a genome-editing tool marked the beginning of a new era in functional genomics. The natural CRISPR system, first characterized by Francisco Mojica in the 1990s [28], functions as an adaptive immune system in bacteria. Key discoveries followed, including Alexander Bolotin's identification of Cas9 and the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) in 2005 [28], and the seminal 2012 publications by Charpentier, Doudna, and Siksnys demonstrating that Cas9 could be programmed with a single guide RNA to create targeted double-strand breaks in DNA [28]. The transformative potential for eukaryotic cells was realized in January 2013, when Feng Zhang and George Church's laboratories simultaneously reported successful genome editing in human and mouse cells [28]. Unlike RNAi, which reduces gene expression at the mRNA level, CRISPR-Cas9 introduces permanent changes to the DNA sequence itself, typically resulting in complete gene knockout through frameshift mutations [26]. This fundamental difference in mechanism underlies CRISPR's advantages in consistency, potency, and specificity for functional genomic applications.

Comparative Performance: RNAi versus CRISPR

Table 1: Systematic comparison of RNAi and CRISPR-Cas9 screening technologies

| Feature | RNAi | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | mRNA degradation/translational inhibition | DNA double-strand breaks → indels → frameshifts |

| Molecular Effect | Gene knockdown (partial reduction) | Gene knockout (complete disruption) |

| Target Specificity | Moderate (off-targets via seed matches) | High (requires perfect complementarity) |

| Phenotype Strength | Variable, dose-dependent | Typically strong, binary |

| Screening Reproducibility | Moderate | High |

| Technical Validation Rate | ~30-60% | ~70-90% |

| Essential Gene Detection | Identifies ~60% at 1% FPR | Identifies ~60% at 1% FPR |

| Additional Hits | ~3,100 genes at 10% FPR | ~4,500 genes at 10% FPR |

| Overlap Between Technologies | ~1,200 genes identified in both | ~1,200 genes identified in both |

| Primary Applications | Loss-of-function studies, drug target ID | Knockout, activation, inhibition, base editing |

Direct comparative studies reveal both complementary and distinct characteristics of each technology. In parallel screens conducted in the K562 chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line, both RNAi and CRISPR showed similar precision in detecting essential genes (AUC >0.90), with each identifying approximately 60% of gold standard essential genes at a 1% false positive rate [14]. However, each technology also identified thousands of unique hits not detected by the other, suggesting they may capture different biological aspects [14]. Notably, CRISPR screens identified electron transport chain genes as essential, while RNAi screens uniquely detected chaperonin-containing T-complex subunits [14]. This differential enrichment of biological processes highlights how each technology can reveal distinct genetic vulnerabilities. Statistical frameworks like casTLE (Cas9 high-Throughput maximum Likelihood Estimator) that combine data from both technologies have demonstrated improved performance in essential gene identification, achieving AUC of 0.98 and recovering >85% of gold standard essential genes at ~1% FPR [14].

CRISPR-Based Screening Approaches: Technical Advances

Diverse CRISPR Screening Modalities

The core CRISPR-Cas9 system has been extensively engineered to enable diverse screening applications beyond simple gene knockouts. The catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) variant, generated by mutating the RuvC and HNH nuclease domains, retains DNA-binding capability without creating double-strand breaks [21]. This foundational modification has enabled the development of multiple screening modalities:

CRISPR Knockout (CRISPRko): Uses wild-type Cas9 to create double-strand breaks, resulting in frameshift mutations and gene knockout through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair [22]. This approach is preferred for complete gene inactivation and essential gene identification.

CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi): Employes dCas9 fused to transcriptional repressors like KRAB (Krüppel-associated box) to block transcription initiation or elongation, achieving reversible gene silencing without DNA damage [22] [21]. This method is valuable for studying essential genes and non-coding elements.

CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa): Utilizes dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators such as VP64, VP64-p65-Rta (VPR), or synergistic activation mediator (SAM) to enhance gene expression [22] [21]. This enables gain-of-function screens that complement loss-of-function approaches.

More recently, base editors and prime editors have further expanded the CRISPR screening toolbox. Base editors enable precise single-nucleotide changes without double-strand breaks, while prime editors allow targeted insertions, deletions, and all possible base-to-base conversions [25]. These technologies have enabled variant-focused screens that functionally annotate single-nucleotide variants of unknown significance, as demonstrated by Kim and colleagues, who used prime-editor tiling arrays to identify EGFR variants conferring drug resistance [21].

Advanced Screening Readouts and Applications

Early CRISPR screens primarily relied on cell viability or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) as readouts, but recent advances have dramatically diversified the phenotypic measurements possible. The integration of CRISPR with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies like Perturb-seq, CRISP-seq, and CROP-seq enables high-resolution assessment of transcriptomic changes resulting from genetic perturbations [22] [21]. This approach allows simultaneous analysis of hundreds of individual genetic perturbations and their effects on global gene expression patterns in complex cell populations.

Perturbomics represents a systematic functional genomics approach that annotates genes based on phenotypic changes induced by CRISPR-mediated perturbations [21]. This method has been successfully applied to identify novel therapeutic targets for cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders. For example, CRISPR screens have identified genes whose modulation sensitizes cancer cells to targeted therapies, reveals mechanisms of drug resistance, and uncovers vulnerabilities in specific genetic backgrounds [21] [27].

Table 2: Bioinformatics tools for CRISPR screen data analysis

| Tool Name | Year | Statistical Method | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAGeCK | 2014 | Negative binomial distribution + Robust Rank Aggregation | CRISPRko screens | First specialized workflow, widely adopted |

| MAGeCK-VISPR | 2015 | Negative binomial + Maximum likelihood estimation | CRISPR chemogenetic screens | Integrated workflow with QC visualization |

| BAGEL | 2016 | Reference gene set distribution + Bayes factor | Essential gene identification | Bayesian framework for essentiality |

| CRISPhieRmix | 2018 | Hierarchical mixture model | CRISPRi/a screens | Expectation-maximization algorithm |

| JACKS | 2019 | Bayesian hierarchical modeling | Multiplexed screens | Improved quantification of guide activity |

| DrugZ | 2019 | Normal distribution + Sum z-score | CRISPR drug-gene interactions | Identifies drug resistance/sensitivity genes |

| scMAGeCK | 2020 | RRA/Linear regression | Single-cell CRISPR screens | Links perturbations to transcriptomes |

| SCEPTRE | 2020 | Negative binomial regression | Single-cell perturbation screens | Handers low multiplicity of infection |

Experimental Protocols: From RNAi to CRISPR Screening

Protocol: Genome-scale RNAi Screening

Principle: This protocol uses lentiviral-delivered shRNA libraries to achieve stable gene knockdown in mammalian cells, followed by phenotypic selection and sequencing-based quantification of shRNA abundance.

Materials:

- shRNA Library: Arrayed or pooled shRNA library (e.g., 5-10 shRNAs per gene)

- Cell Line: Appropriate mammalian cell line for biological question

- Lentiviral Packaging System: For library delivery

- Selection Antibiotics: For stable cell line selection

- Next-Generation Sequencing Platform: For shRNA quantification

Procedure:

- Library Amplification and Validation: Amplify shRNA library plasmid DNA and sequence validate to ensure representation.

- Lentivirus Production: Package shRNA library into lentiviral particles using HEK293T cells and concentration determination.

- Cell Infection: Infect target cells at low MOI (0.3-0.5) to ensure single integration events.

- Selection: Apply puromycin selection (or other appropriate antibiotic) for 3-7 days to establish stable knockdown pools.

- Phenotypic Application: Split cells into treatment and control arms (e.g., drug treatment vs. DMSO control).

- Harvesting: Collect cells at multiple time points (typically day 0, day 7, day 14).

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Isolve high-quality genomic DNA from all samples.

- shRNA Amplification and Sequencing: PCR amplify shRNA inserts from genomic DNA and sequence using NGS.

- Data Analysis: Process sequencing data to quantify shRNA abundance changes between conditions.

Critical Considerations:

- Maintain ≥500 cells per shRNA throughout selection to prevent library bottlenecking

- Include biological replicates to ensure reproducibility

- Use non-targeting shRNA controls for normalization

- Account for seed-based off-target effects in data interpretation

Protocol: Pooled CRISPR Knockout Screening

Principle: This protocol uses lentiviral-delivered sgRNA libraries with Cas9-expressing cells to generate gene knockouts, followed by phenotypic selection and NGS-based quantification of sgRNA abundance.

Materials:

- sgRNA Library: Pooled sgRNA library (e.g., 4-10 sgRNAs per gene)

- Cas9-Expressing Cell Line: Stable Cas9-expressing cells or wild-type cells with Cas9 delivery

- Lentiviral Packaging System: For sgRNA library delivery

- Selection Antibiotics: For stable cell selection

- Next-Generation Sequencing Platform: For sgRNA quantification

- MAGeCK Software: For computational analysis

Procedure:

- Library Amplification: Transform and amplify sgRNA library plasmid DNA in electrocompetent E. coli to maintain diversity.

- Lentivirus Production: Package sgRNA library into lentiviral particles using HEK293T cells, then titer and concentrate.

- Cell Infection: Infect Cas9-expressing cells at MOI of 0.3-0.5 to ensure single sgRNA integration.

- Selection: Apply puromycin selection for 3-7 days to establish stable sgRNA expression.

- Reference Sample Collection: Harvest 50-100 million cells as Day 0 reference time point.

- Phenotypic Application: Split remaining cells into experimental arms and apply selection pressure for 14-21 days.

- Endpoint Harvesting: Collect surviving cells at experimental endpoint.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from all samples (Day 0 and endpoint).

- sgRNA Amplification and Sequencing: PCR amplify sgRNA cassettes from genomic DNA with barcoded primers for multiplexed NGS.

- Data Analysis: Process FASTQ files through MAGeCK pipeline to identify significantly enriched/depleted sgRNAs and genes.

Critical Considerations:

- Maintain ≥500 cells per sgRNA throughout screen (≥1000x library coverage)

- Include non-targeting control sgRNAs for normalization

- Validate Cas9 activity and editing efficiency before screening

- Perform Western blot or T7E1 assay to confirm knockout efficiency for hit genes

Protocol: CRISPR Screen Data Analysis with MAGeCK

Principle: This computational protocol uses the MAGeCK workflow to identify significantly enriched or depleted genes from CRISPR screen sequencing data.

Materials:

- Computing Resources: Linux/server environment with sufficient memory and storage

- FASTQ Files: Raw sequencing files from screen samples

- sgRNA Library Annotation File: Tab-delimited file mapping sgRNAs to genes

- Sample Metadata: File describing experimental conditions and replicates

Procedure:

- Quality Control and Read Counting:

Quality Assessment:

Differential Analysis:

Visualization and Downstream Analysis:

Critical Considerations:

- Use negative control sgRNAs for normalization when available

- Check read count distribution and sgRNA dropout rates

- Validate top hits using orthogonal approaches (e.g., individual knockouts)

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis on significant hits

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential research reagents for CRISPR-based functional genomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | Wild-type SpCas9, SaCas9, Cpf1 | Induce double-strand breaks for gene knockout |

| CRISPR Effector Domains | dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-VPR, dCas9-p300 | Transcriptional repression/activation or epigenetic modification |

| sgRNA Libraries | Genome-wide knockout (Brunello), CRISPRi v2, SAM | Target specific gene sets at scale with optimized sgRNAs |

| Delivery Systems | Lentiviral, AAV, lipid nanoparticles | Introduce CRISPR components into target cells |

| Cell Lines | Cas9-expressing lines (e.g., HEK293T-Cas9), iPSCs | Provide cellular context for screening with stable Cas9 expression |

| Selection Markers | Puromycin, blasticidin, fluorescent proteins | Enrich for successfully transduced cells |

| Sequencing Reagents | Illumina sequencing primers, barcoded adapters | Amplify and sequence sgRNA representations |

| Analysis Software | MAGeCK, BAGEL, PinAPL-Py | Identify significantly enriched/depleted genes from screen data |

| Validation Reagents | siRNA, antibodies, qPCR assays | Confirm screen hits using orthogonal methods |

The evolution from RNAi to CRISPR-based functional genomics represents one of the most significant technological transitions in modern biology. While RNAi established the foundation for systematic loss-of-function screening in mammalian cells, CRISPR technologies have addressed many of its limitations through more complete gene disruption, higher specificity, and greater versatility [14] [27]. The development of diverse CRISPR modalities—including knockout, interference, activation, base editing, and prime editing—has created an expansive toolkit for functional genomics that enables both loss-of-function and gain-of-function studies at unprecedented scale [25] [21].

Current challenges in CRISPR screening include minimizing off-target effects, improving in vivo delivery, and handling the computational complexity of large-scale screening data [29] [27]. Future directions point toward more physiologically relevant screening systems, including organoid-based models, single-cell multi-omics readouts, and in vivo screening approaches [21] [27]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with CRISPR screening data holds promise for predicting gene function and genetic interactions [27]. As these technologies continue to mature, CRISPR-based functional genomics will play an increasingly central role in therapeutic target identification, drug discovery, and precision medicine, ultimately accelerating our understanding of gene function in health and disease.

Executing Successful Screens: From Library Design to Phenotypic Readouts

In the field of functional genomics, CRISPR screening has emerged as a powerful methodology for unbiased identification of genes involved in biological processes and disease pathologies. The foundation of any successful CRISPR screen lies in the careful design of the guide RNA (gRNA) library, which determines the scope and precision of genetic perturbations. Library design strategies have evolved to encompass three primary categories: genome-wide libraries for comprehensive discovery, focused libraries for investigating specific pathways, and custom libraries for tailored experimental needs. The strategic selection and design of these libraries are critical for researchers aiming to elucidate gene function and identify novel therapeutic targets in mammalian cells [30] [21].

The versatility of CRISPR-Cas systems has enabled the development of diverse perturbation modalities beyond simple gene knockout, including transcriptional activation (CRISPRa), interference (CRISPRi), and epigenetic silencing (CRISPRoff). Each modality requires specialized library design considerations to maximize perturbation efficacy while minimizing off-target effects. This application note outlines key principles, design parameters, and practical protocols for implementing these library strategies within the context of mammalian cell research and drug discovery pipelines [31] [21].

Library Types and Applications

Genome-Wide Libraries

Genome-wide CRISPR libraries are designed to target every known gene in an organism, enabling unbiased discovery of genes involved in biological processes without prior assumptions about gene function. These libraries provide the most comprehensive approach for functional genetic screening but require significant experimental resources and computational infrastructure.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Genome-Wide Library Design

| Parameter | Typical Specification | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | All protein-coding genes (~19,000-20,000 human genes) | Non-coding RNAs and regulatory elements can be included |

| gRNAs per Gene | 4-10 | Increased numbers improve statistical confidence and knockout efficiency |

| Library Size | ~75,000-100,000 gRNAs | Varies with gRNA density and additional non-targeting controls |

| Control gRNAs | 100-1,000 non-targeting gRNAs | Essential for benchmarking background noise and normalization |

| Coverage Requirement | 250-500x per gRNA | Minimum 250x coverage recommended for robust statistical power |

Recent advances in genome-wide library design have addressed previous limitations through innovative approaches such as quadruple-guide RNA (qgRNA) vectors, where four distinct gRNAs targeting the same gene are combined in a single construct. This multi-guide approach significantly enhances perturbation efficacy, with reported ablation efficiencies of 75-99% for gene knockout and 76-92% for epigenetic silencing experiments [31]. The ALPA (automated liquid-phase assembly) cloning method enables high-throughput construction of these arrayed qgRNA libraries, facilitating the systematic perturbation of 19,000-22,000 human protein-coding genes with minimal recombination artifacts [31].