CRISPR Genome Editing: A Foundational Guide for Research and Therapeutic Development

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to CRISPR genome editing for researchers and drug development professionals.

CRISPR Genome Editing: A Foundational Guide for Research and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to CRISPR genome editing for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational concepts, from the core mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas9 to advanced base and prime editing systems. The guide explores diverse methodological applications in both basic research and clinical trials, addresses key troubleshooting challenges like off-target effects and delivery, and offers a comparative analysis of validation techniques. By synthesizing current research and clinical progress, this resource aims to equip new researchers with the knowledge to effectively implement and validate CRISPR technologies in their work.

The CRISPR Revolution: From Bacterial Immunity to Programmable Gene Editing

The ability to precisely modify the genome represents one of the most transformative advancements in modern biology, enabling researchers to investigate gene function, model diseases, and develop innovative therapies for genetic disorders [1]. The evolution of genome editing platforms—from early programmable nucleases to the current CRISPR-dominated landscape—has progressively democratized access to precision genetic engineering. This evolution began with protein-engineered systems like zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), which established the feasibility of targeted DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) but required complex design processes [1] [2]. The discovery of CRISPR-Cas systems marked a revolutionary turning point, shifting the paradigm from protein-based to RNA-guided targeting and making genome editing more accessible, cost-effective, and versatile than ever before [1] [2]. This technical guide provides new researchers with a comprehensive overview of these core platforms, their mechanisms, applications, and experimental considerations within the context of contemporary biomedical research.

Historical Background of Genome Editing Techniques

Meganucleases

Meganucleases, also known as homing endonucleases, were among the earliest classes of programmable nucleases used in genome editing [2]. These naturally occurring enzymes recognize large DNA target sequences (14-40 base pairs) and induce site-specific DSBs [2]. While they exhibit high specificity and minimal off-target activity, their historical limitation has been the difficulty of reprogramming target specificity, though recent engineering advances by companies like Precision BioSciences have addressed this challenge [2].

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs)

ZFNs emerged as the first generation of programmable nucleases, combining a zinc finger DNA-binding domain with the FokI restriction endonuclease domain [2]. Each zinc finger motif recognizes a specific DNA triplet, and multiple fingers are assembled to target longer sequences [1] [2]. A significant limitation of ZFNs is their context-dependent binding, where the activity of individual fingers can be influenced by their neighbors, making design complex and often requiring extensive optimization [3]. The construction of ZFN expression plasmids for a new target could take several months, limiting their widespread adoption [2].

Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs)

TALENs represented a significant advancement in design flexibility, utilizing TALE proteins from the plant pathogen Xanthomonas [2]. Each TALE repeat recognizes a single nucleotide through repeat-variable di-residues (RVDs), with specific RVD codes (NG for T, NI for A, HD for C, and NN for G) enabling more straightforward target recognition compared to ZFNs [2]. While TALENs offered improved design simplicity and higher success rates, their large size and challenging delivery, particularly via viral vectors, remained significant limitations [2].

Mechanism of Action: A Comparative Analysis

Fundamental DNA Recognition Mechanisms

Each genome editing platform operates through distinct DNA recognition and cleavage mechanisms:

- ZFNs: Use protein-DNA interactions where zinc finger domains recognize DNA triplets. The FokI nuclease domain must dimerize to become active, requiring two ZFN monomers binding to opposite DNA strands with proper orientation and spacing [2].

- TALENs: Similarly rely on protein-DNA interactions but with a simpler one-repeat-to-one-nucleotide recognition code. Like ZFNs, TALENs also use the FokI nuclease that requires dimerization for activity [2].

- CRISPR-Cas9: Utilizes RNA-DNA base pairing where a guide RNA (gRNA) directs the Cas9 nuclease to complementary DNA sequences. The system requires a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site for recognition [2] [3].

DNA Repair Pathways

All three platforms create double-strand breaks (DSBs) that are repaired by endogenous cellular mechanisms [2]:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair pathway that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels), frequently leading to gene knockouts [1] [2].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair mechanism that uses a DNA template to facilitate accurate gene corrections or insertions, though this pathway occurs less frequently than NHEJ [1] [2].

DNA Repair Pathways Following Genome Editing. This diagram illustrates the two primary cellular repair mechanisms activated after a double-strand break is introduced by genome editing tools. NHEJ typically results in gene knockouts, while HDR enables precise edits using a donor template.

Technical Comparison of Genome Editing Platforms

The following tables provide a comprehensive technical and practical comparison of the three major genome editing platforms, highlighting their key characteristics and relative advantages for research applications.

Table 1: Molecular Characteristics and Performance Metrics

| Feature | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recognition | Protein-based (Zinc fingers) | Protein-based (TALE repeats) | RNA-based (Guide RNA) |

| Nuclease | FokI | FokI | Cas9 |

| Target Specificity | High (12-18 bp per monomer) | High (14-20 bp per monomer) | Moderate to High (20 bp + PAM) |

| Recognition Code | Complex (DNA triplet per finger) | Simple (1 nucleotide per repeat) | Simple (Watson-Crick base pairing) |

| Off-Target Effects | Lower than CRISPR | Lower than CRISPR | Higher (but improving with new variants) |

| PAM Requirement | No | No | Yes (NGG for SpCas9) |

| Typical Editing Efficiency | Variable (context-dependent) | High (>90% in some studies) | High (often >70%) |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited | Limited | High (multiple gRNAs) |

Data compiled from [1] [2] [3]

Table 2: Practical Research Considerations

| Parameter | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Complexity | High (requires expert knowledge) | Moderate (modular but repetitive) | Low (simple gRNA design) |

| Design Timeline | ~1 month | ~1 month | Within a week |

| Cost | High | Medium | Low |

| Delivery Method | Primarily plasmid vectors | Primarily plasmid vectors | Multiple options (viral, LNP, etc.) |

| Scalability | Limited | Limited | High (ideal for high-throughput) |

| Accessibility | Low (proprietary platforms) | Moderate | High (widely accessible) |

| Time for Stable Cell Line | Months | Months | Weeks |

| Best Applications | High-precision therapeutic edits | Validated high-specificity edits | Functional genomics, screening, therapeutics |

Data compiled from [1] [2] [3]

CRISPR-Cas Systems: A Technical Revolution

Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has become the most widely utilized genome editing platform due to its straightforward design, low cost, high efficiency, and short experimental cycle [2]. The system consists of two key components: the Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) that combines CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) into a single molecule [3]. The gRNA directs Cas9 to complementary DNA sequences adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), which for the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) is "NGG" [3]. Upon binding, Cas9 creates a blunt-ended double-strand break 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM site [2].

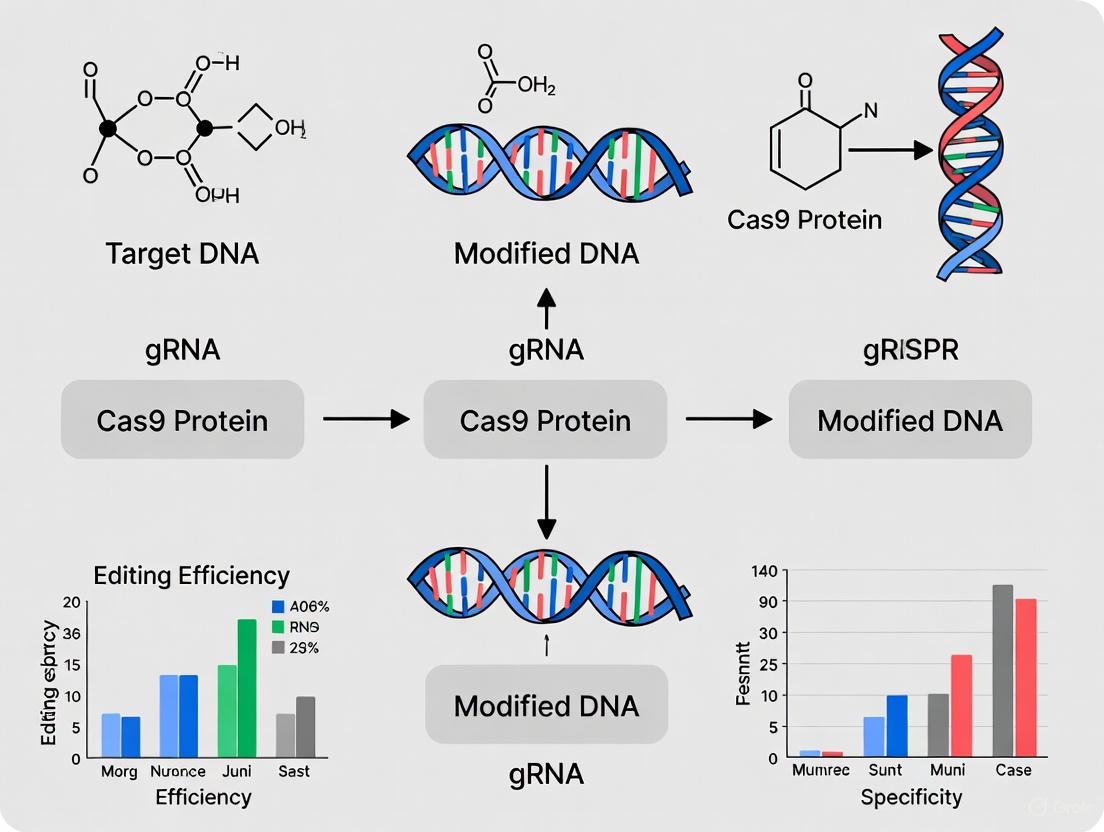

CRISPR-Cas9 Target Recognition and Cleavage. This diagram shows the CRISPR-Cas9 complex, where the guide RNA directs the Cas9 protein to a specific DNA sequence adjacent to a PAM sequence, resulting in a double-strand break.

CRISPR Screening and Functional Genomics

One of CRISPR's most significant advantages is its scalability for high-throughput functional genomics screens. CRISPR screening enables researchers to systematically knock out or activate genes across the entire genome to identify essential genes, uncover novel drug targets, and optimize combination therapy strategies [1]. Crown Bioscience and other organizations leverage CRISPR screening to accelerate drug discovery, enabling loss-of-function and gain-of-function studies at an unprecedented scale [1].

Advanced CRISPR Technologies

The CRISPR toolkit has expanded significantly beyond the standard Cas9 system:

- Base Editing: Allows single-nucleotide changes without creating DSBs, reducing off-target risks [1] [4]. Companies like Beam Therapeutics are leveraging base editing for therapeutic applications like sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia [5].

- Prime Editing: Capable of introducing complex edits without DSBs, expanding CRISPR's therapeutic potential [1] [4]. Recent studies have successfully used prime editing to correct pathogenic mutations in inherited retinal diseases [6].

- Epigenetic Editing: Systems like those developed by Chroma Medicine (now nChroma Bio) modify gene expression without changing DNA sequences by writing or erasing epigenetic marks [5].

- Compact Cas Variants: Proteins like Cas12, Cas13, and CasΦ from companies like Mammoth Biosciences offer smaller sizes for improved delivery and new applications like RNA targeting [1] [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General Workflow for Genome Editing Experiments

A standard genome editing experiment follows these key steps:

- Target Selection: Identify specific genomic target site considering accessibility, chromatin state, and potential off-target sites.

- Design and Synthesis: Create ZFNs/TALENs or gRNAs using appropriate design tools and algorithms.

- Delivery: Introduce editing components into target cells using appropriate methods (see Section 6.2).

- Validation: Confirm editing efficiency and specificity using sequencing and functional assays.

- Analysis: Assess phenotypic outcomes and potential off-target effects.

Delivery Methods

Efficient delivery of editing components remains a critical challenge:

- Viral Vectors: Lentiviruses and adenoviruses can package CRISPR components, though size limitations exist for larger nucleases [1].

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): Particularly effective for in vivo delivery, especially to the liver. Successfully used in clinical trials for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) and hereditary angioedema (HAE) [7] [5].

- Electroporation: Effective for ex vivo editing of hematopoietic stem cells and immune cells.

- AAV Vectors: Useful for in vivo gene therapy but limited by packaging capacity.

Recent advances have demonstrated the potential for redosing with LNP-delivered CRISPR therapies, as they don't trigger the same immune responses as viral vectors [7].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The following table outlines essential reagents and their applications in genome editing research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Genome Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleases | SpCas9, SaCas9, FokI | Core editing enzymes that create double-strand breaks |

| Guide RNAs | Synthetic crRNA/tracrRNA, sgRNA | Target recognition molecules for CRISPR systems |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lentivirus, AAV, Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Vectors for introducing editing components into cells |

| Design Tools | CRISPR-GPT, various web tools | AI-assisted design of gRNAs and experimental planning |

| Editing Enhancers | NHEJ inhibitors, HDR enhancers | Small molecules that improve editing efficiency and precision |

| Detection Assays | T7E1, TIDE, NGS-based methods | Methods to quantify editing efficiency and off-target effects |

| Cell Culture Media | GMP-grade media, stem cell media | Specialized formulations for maintaining edited cells |

Data compiled from [1] [2] [8]

Applications and Current Landscape

Therapeutic Applications

Genome editing technologies have demonstrated remarkable success in clinical applications:

- CRISPR Therapeutics: The first FDA-approved CRISPR-based medicine, Casgevy, treats sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia [7]. Intellia Therapeutics has shown promising results with in vivo CRISPR treatments for hATTR and HAE, achieving over 90% reduction in disease-related proteins [7] [5].

- Traditional Methods: ZFNs and TALENs continue to find applications in specific therapeutic areas. Cellectis has reported promising Phase 1 results for lasme-cel, an allogeneic CAR-T therapy likely developed using TALEN-based gene editing [6].

- Novel Applications: Companies like Eligo Bioscience are pioneering microbiome editing using CRISPR to target specific bacterial populations without disrupting the overall microbiome balance [5].

Agricultural and Industrial Applications

In agriculture, genome editing technologies have been deployed to develop crops with improved yield, disease resistance, and environmental resilience [3]. CRISPR-Cas9 has emerged as the most promising tool for agricultural applications due to its scalability and user-friendly design, potentially addressing food security challenges for a growing global population [3].

Research and Drug Discovery

Beyond direct therapeutics, genome editing platforms have become indispensable tools for basic research and drug discovery. CRISPR screening enables systematic functional genomics studies, while engineered cell lines and animal models provide robust platforms for target validation and compound screening [1].

Future Directions and Innovations

The genome editing field continues to evolve rapidly with several promising developments:

- AI Integration: Tools like CRISPR-GPT from Stanford Medicine use artificial intelligence to assist researchers in designing experiments, predicting off-target effects, and troubleshooting design flaws, potentially accelerating therapeutic development [8].

- Improved Delivery Systems: Ongoing research focuses on developing novel delivery methods, including cell-specific LNPs and improved viral vectors, to expand the range of treatable tissues beyond the liver [7] [6].

- Enhanced Specificity: New engineered Cas variants with improved fidelity and reduced off-target effects are continuously being developed [1] [4].

- Expanded Applications: The combination of genome editing with other technologies like organ-on-chip models provides more clinically relevant preclinical testing platforms [6].

The evolution of genome editing platforms from ZFNs and TALENs to CRISPR systems has transformed molecular biology and therapeutic development. While traditional methods maintain relevance for specific high-precision applications requiring validated edits, CRISPR has emerged as the dominant platform due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and versatility. For new researchers entering the field, understanding the comparative advantages, limitations, and appropriate applications of each platform is essential for designing successful experiments. As the technology continues to advance with improvements in specificity, delivery, and AI-assisted design, genome editing is poised to drive further innovations across biomedical research, therapeutic development, and agricultural biotechnology.

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) system is an adaptive immune mechanism found in bacteria and archaea that provides protection against invading viruses and foreign genetic material [9] [10]. This natural defense system has been repurposed as a revolutionary genome-editing technology that enables precise manipulation of DNA sequences in virtually any organism [11] [12]. The CRISPR-Cas9 system has transformed biomedical research and therapeutic development due to its simplicity, efficiency, and programmability compared to previous gene-editing tools like zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) [13] [14].

At its core, the CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two fundamental components: the Cas9 endonuclease, which creates double-strand breaks in DNA, and a guide RNA (gRNA), which directs Cas9 to a specific genomic location [13] [15]. The system functions with remarkable precision by leveraging the complementary base-pairing rules of nucleic acids, allowing researchers to target specific DNA sequences simply by redesigning the gRNA [10] [16]. This technical guide will explore the core mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas9, focusing on the structure and function of gRNA, the critical role of Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sites, and the molecular events leading to double-strand break creation and repair.

The Guide RNA (gRNA): Molecular Address for Target Recognition

Structure and Components of gRNA

The guide RNA serves as the targeting mechanism of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, providing specificity through complementary base pairing. In its engineered form for laboratory applications, the gRNA is typically implemented as a single guide RNA (sgRNA) that combines two naturally occurring RNA molecules into a single construct [15]. The sgRNA consists of:

- crRNA (CRISPR RNA) component: A 17-20 nucleotide sequence that is complementary to the target DNA region and provides targeting specificity through Watson-Crick base pairing [13] [15].

- tracrRNA (trans-activating crRNA) component: A scaffold sequence that facilitates binding to the Cas9 protein and is essential for Cas9-mediated cleavage activity [15].

- Linker loop: A synthetic component that connects the crRNA and tracrRNA into a single molecular entity in engineered sgRNAs [15].

The gRNA forms a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex with the Cas9 enzyme through interactions between the tracrRNA scaffold and surface-exposed, positively-charged grooves on Cas9 [13]. This binding induces a conformational change in Cas9, shifting it into an active DNA-binding configuration while leaving the spacer region of the gRNA free to interact with target DNA [13].

gRNA Design Considerations

Effective gRNA design is critical for successful CRISPR experiments, impacting both on-target efficiency and off-target effects. Key design parameters include:

- Specificity: The target sequence should be unique within the genome to minimize off-target effects [13]. Bioinformatics tools are essential for identifying specific targets.

- GC Content: Optimal GC content should range between 40-80% to ensure sufficient stability without excessive nonspecific binding [15].

- Seed Sequence: The 8-10 bases at the 3' end of the gRNA targeting sequence (adjacent to the PAM) are particularly critical for target recognition and cleavage efficiency [13].

- Length: For commonly used SpCas9, gRNA targeting sequences typically range from 17-23 nucleotides [15].

Table 1: gRNA Design Parameters and Recommendations

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 17-23 nucleotides | Balances specificity and efficiency |

| GC Content | 40-80% | Ensures appropriate stability and binding affinity |

| Seed Sequence | 8-10 bases at 3' end | Critical for initial recognition and cleavage efficiency |

| Specificity | Unique in genome | Minimizes off-target effects |

Several computational tools have been developed to facilitate optimal gRNA design, including CHOPCHOP, CRISPRscan, and Synthego's design tool, which incorporate these parameters to predict gRNA efficiency and specificity [15].

Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): The Self vs. Non-Self Discriminator

PAM Recognition and Function

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a short, conserved DNA sequence adjacent to the target site (protospacer) that is essential for Cas9-mediated cleavage [9] [14]. The PAM sequence plays a critical role in the natural bacterial immune system by enabling discrimination between "self" and "non-self" DNA, preventing autoimmunity by ensuring that the CRISPR locus itself is not targeted [9] [13]. The PAM is not part of the bacterial host genome but is located next to the protospacer region in invading DNA [14].

For the most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), the canonical PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" represents any nucleotide base [13] [14]. The Cas9 enzyme will not bind or cleave target DNA if this PAM sequence is not present immediately downstream of the target sequence [14]. The PAM is recognized directly by the Cas9 protein, not by the gRNA, and this recognition is essential for initiating the DNA unwinding that allows gRNA to hybridize with the target DNA [9].

PAM-Dependent Target Activation

The mechanism of PAM recognition and subsequent target activation involves several coordinated steps:

- Initial Scanning: Cas9 surveillance complexes efficiently scan DNA sequences for PAM recognition [9].

- PAM Binding: Once Cas9 binds the PAM sequence, it undergoes conformational changes that facilitate DNA unwinding [9].

- Seed Sequence Interrogation: The seed sequence near the PAM is checked for complementarity with the gRNA spacer [9].

- R-loop Formation: If seed sequence matching occurs, the gRNA continues to anneal to the target DNA, forming a triple-stranded R-loop structure [9].

- Cas9 Activation: Complete hybridization induces another conformational change in Cas9, activating its nuclease domains [13].

The stringency of PAM recognition varies among different CRISPR-Cas systems and between the adaptation and interference stages, leading to proposals to classify PAM elements as spacer acquisition motifs (SAMs) and target interference motifs (TIMs) [9].

PAM Sequences for Different Cas Enzymes

Different Cas enzymes recognize distinct PAM sequences, which determines their targeting range and applications. The following table summarizes PAM sequences for several commonly used Cas enzymes:

Table 2: PAM Sequences for Different Cas Enzymes

| Cas Enzyme | Source Organism | PAM Sequence | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 5'-NGG-3' | Most widely used; abundant PAM |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | 5'-NNGRR(N)-3' | Smaller size for viral delivery |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Acidaminococcus spp. | 5'-TTTV-3' | Staggered DNA cuts; simpler gRNA |

| Cas12a Ultra | Engineered | 5'-TTTN-3' | Enhanced activity; TTTT may work with reduced potency |

| AsCas12f | Axidibacillus sulfuroxidans | Varies | Compact size (one-third of SpCas9) for AAV delivery |

The PAM requirement represents a significant constraint in CRISPR targeting, inspiring the development of engineered Cas variants with altered PAM specificities, such as xCas9 (recognizes NG, GAA, and GAT), SpCas9-NG (recognizes NG), SpG (recognizes NGN), and SpRY (recognizes NRN/NYN) [13] [12].

Double-Strand Break Creation and DNA Repair Mechanisms

Molecular Mechanism of DNA Cleavage

Upon successful PAM recognition and target binding, Cas9 undergoes a final conformational change that activates its nuclease domains to create a double-strand break (DSB) in the target DNA [13]. The Cas9 enzyme contains two distinct nuclease domains:

- HNH Domain: Cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the gRNA (target strand)

- RuvC Domain: Cleaves the non-complementary DNA strand (non-target strand)

These coordinated cleavage events result in a blunt-ended DSB located approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [13]. The precision of this cleavage is determined by the gRNA-DNA complementarity, particularly in the seed sequence adjacent to the PAM [13].

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Target Recognition and Cleavage Mechanism

DNA Repair Pathways

Cells employ two primary pathways to repair CRISPR-induced DSBs, each with distinct molecular mechanisms and outcomes:

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

NHEJ is the dominant and more efficient repair pathway in most cells, particularly in non-dividing cells [13]. This pathway directly ligates the broken DNA ends without requiring a repair template, making it error-prone and frequently resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site [17] [13]. These indels can disrupt the open reading frame of the targeted gene, causing frameshift mutations and premature stop codons that effectively knock out gene function [13]. The error-prone nature of NHEJ is leveraged in knockout experiments to generate loss-of-function mutations.

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

HDR is a less efficient but high-fidelity repair pathway that requires a homologous DNA template to accurately repair the break [13]. This pathway is more active in dividing cells and during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle [12]. In CRISPR applications, researchers can supply an exogenous donor DNA template with homology arms flanking the desired modification, enabling precise gene editing such as nucleotide substitutions, gene insertions, or gene corrections [17] [12].

Diagram 2: DNA Repair Pathways After CRISPR-Cas9 Cleavage

Advanced CRISPR Editing Systems

To overcome limitations of standard CRISPR-Cas9 editing, particularly the reliance on error-prone NHEJ, researchers have developed advanced engineered systems:

- Base Editing: Uses modified Cas9 (nCas9 or dCas9) fused to a deaminase enzyme to directly convert one DNA base to another (C-to-T or A-to-G) without creating DSBs [12].

- Prime Editing: Employs nCas9 fused to an engineered reverse transcriptase and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) to copy edited genetic information directly into the target site, enabling precise changes without DSBs [12].

- CRISPR Interference/Activation (CRISPRi/CRISPRa): Utilizes catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional repressors or activators to modulate gene expression without altering DNA sequence [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow for Gene Knockout

A standard protocol for generating gene knockouts using CRISPR-Cas9 involves the following key steps:

gRNA Design and Selection:

- Identify target sequences (20 nucleotides) adjacent to PAM sites (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) within the gene of interest

- Use design tools (CHOPCHOP, CRISPRscan, Synthego) to minimize off-target effects

- Select 2-4 gRNAs for testing to ensure at least one efficient guide

gRNA Delivery Format Selection:

- Choose between plasmid-expressed sgRNA, in vitro transcribed (IVT) sgRNA, or synthetic sgRNA based on experimental needs

- Synthetic sgRNA typically offers highest efficiency and consistency [15]

Cas9 Delivery:

- Select appropriate Cas9 variant (wildtype, high-fidelity, etc.)

- Choose delivery method: plasmid DNA, mRNA, or recombinant protein

Co-delivery of gRNA and Cas9:

- Transferd cells with gRNA and Cas9 using appropriate method (lipofection, electroporation, viral delivery)

- For RNP delivery, pre-complex purified Cas9 protein with gRNA before delivery

Validation and Analysis:

- Assess editing efficiency 48-72 hours post-delivery (genomic DNA extraction, T7E1 assay, TIDE analysis, or NGS)

- Clone edited cells and screen for homozygous knockouts

- Validate knockout at protein level (Western blot, immunofluorescence)

- Confirm phenotype through functional assays

PAM Identification Methods

Several experimental approaches have been developed to identify functional PAM sequences for various CRISPR-Cas systems:

- Plasmid Depletion Assays: A randomized DNA library is inserted adjacent to a target sequence within a plasmid that is transformed into a host with an active CRISPR-Cas system. Plasmids with inactive PAM sequences are retained and identified via next-generation sequencing [9].

- PAM-SCANR (PAM Screen Achieved by NOT-gate Repression): Uses a catalytically dead Cas9 variant (dCas9) added to a target library. Successful binding to a functional PAM represses GFP expression, enabling identification of functional PAM motifs through FACS sorting and sequencing [9].

- In Vitro Cleavage Selection: Involves cleavage of target DNA libraries with multiple PAM sequences followed by sequencing of enriched cleavage products or remaining uncleaved targets [9].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Computational alignment of protospacers from phage genomes to identify conserved PAM elements using tools like CRISPRFinder and CRISPRTarget [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Enzymes | SpCas9 (Wildtype), HiFi Cas9, eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9 | Creates DSBs; high-fidelity variants reduce off-target effects |

| Specialized Cas Variants | Cas9 nickase (Cas9n), dCas9, Base editors, Prime editors | Specific applications; nicking, gene regulation, precise editing |

| gRNA Formats | Plasmid-expressed sgRNA, IVT sgRNA, Synthetic sgRNA | Targets Cas9 to specific genomic loci; synthetic offers highest efficiency |

| Delivery Systems | Lipofection reagents, Electroporation systems, AAV vectors, Lentiviral vectors | Introduces CRISPR components into cells |

| Detection & Validation | T7E1 assay kits, Next-generation sequencing, Antibodies for Western blot | Confirms editing efficiency and functional knockout |

| Cell Culture | Selection antibiotics, Culture media, Transfection enhancers | Maintains cells and improves editing efficiency |

The core mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9—comprising gRNA-mediated targeting, PAM recognition, and DSB creation—represents a powerful technological platform that has revolutionized genetic engineering. The simplicity of reprogramming targeting specificity through gRNA design, combined with the precision of Cas9-mediated cleavage, has enabled diverse applications from basic research to clinical therapies. Understanding the molecular details of these core mechanisms is essential for researchers to design effective experiments, troubleshoot issues, and develop novel CRISPR-based applications. As CRISPR technology continues to evolve with the development of more precise editing systems and improved delivery methods, its impact on biological research and therapeutic development will undoubtedly expand, offering new opportunities to address previously intractable genetic diseases and biological questions.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic research by providing an unprecedented ability to edit genomic DNA with precision and simplicity. This technology, derived from a bacterial adaptive immune system, functions as programmable molecular scissors that can induce double-strand breaks (DSBs) at specific locations in the genome [18] [19]. However, the CRISPR-Cas9 machinery itself does not perform the genetic modification; rather, it creates a targeted DSB that activates the cell's endogenous DNA repair mechanisms [20] [21]. The outcome of genome editing is ultimately determined by which of these cellular pathways repairs the break.

Two primary DNA repair pathways compete to repair CRISPR-induced DSBs: Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [22] [18]. These pathways have distinct mechanisms, efficiencies, and outcomes, making them suitable for different research applications. Understanding how to harness these pathways is fundamental for researchers aiming to perform specific genetic modifications, from simple gene knockouts to precise nucleotide substitutions. The strategic selection between NHEJ and HDR enables a wide range of applications, including gene function studies, disease modeling, and therapeutic development [22] [18].

DNA Repair Mechanism Fundamentals

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): The Quick Fixer

NHEJ is the cell's primary and most efficient mechanism for repairing DSBs throughout most of the cell cycle [20]. This pathway functions by directly ligating the broken DNA ends together without requiring a template. While this process is fast and efficient, its template-independent nature makes it error-prone, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair site [20] [21].

The error-prone characteristic of NHEJ is precisely what makes it particularly valuable for gene knockout studies. When these indels occur within the coding sequence of a gene, they can disrupt the reading frame, leading to premature stop codons and effectively inactivating the gene [18] [20]. The efficiency of NHEJ is notably high because it is active in approximately 90% of the cell cycle and does not depend on a homologous donor template [18].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): The Precision Pathway

In contrast to NHEJ, HDR is a precise repair mechanism that requires a homologous DNA template to accurately repair the DSB [22] [20]. This pathway utilizes either the sister chromatid (naturally available during S and G2 phases of the cell cycle) or an exogenously supplied donor template containing homologous sequences flanking the desired edit [18] [23].

HDR's template-dependent nature allows researchers to introduce specific genetic modifications, including point mutations, sequence insertions, or gene replacements, with high precision [22] [21]. To leverage HDR for genome editing, scientists design a donor DNA template that contains the desired modification flanked by homology arms—sequences that match the regions surrounding the DSB. This template guides the repair process, resulting in the precise incorporation of the genetic change into the genome [20] [21]. However, HDR is generally less efficient than NHEJ because it is restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle where homologous DNA is naturally available [18] [23].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of NHEJ and HDR Pathways

| Characteristic | NHEJ | HDR |

|---|---|---|

| Repair Template | Not required | Required (donor DNA with homology arms) |

| Efficiency | High (active in ~90% of cell cycle) | Low (restricted to S/G2 phases) |

| Precision | Error-prone (generates indels) | Precise (faithfully copies template) |

| Primary Application | Gene knockouts | Gene knockins, precise edits |

| Key Limitation | Introduces random mutations | Low efficiency compared to NHEJ |

| Cell Cycle Dependence | Active throughout cell cycle | Primarily in S and G2 phases |

Strategic Pathway Selection for Research Goals

Application-Based Decision Framework

Choosing between NHEJ and HDR depends primarily on the specific research objective. The following guidelines help researchers align their experimental design with the appropriate DNA repair pathway:

Use NHEJ for Gene Knockouts: When the goal is to disrupt gene function through frameshift mutations or premature stop codons, NHEJ is the preferred pathway. Its high efficiency makes it ideal for creating loss-of-function mutations in various model organisms [20] [21]. For knockout experiments, researchers need Cas9 nuclease (delivered as protein or plasmid), single guide RNAs (sgRNA) complexed with Cas9, and PCR primers for edit validation [20].

Use HDR for Precise Genetic Modifications: When the research requires precise edits—including gene knockins, point mutations, or the introduction of specific sequences such as fluorescent protein tags—HDR is the necessary approach [20] [21]. Successful HDR editing requires Cas9-sgRNA complexes and a carefully designed donor template with appropriate homology arms [22].

Quantitative Comparison of Editing Outcomes

Table 2: Experimental Planning Guide for NHEJ vs. HDR Applications

| Experimental Parameter | NHEJ-Based Editing | HDR-Based Editing |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Research Goal | Gene disruption/knockout | Precise editing/knockin |

| Essential Reagents | Cas9 nuclease, sgRNA | Cas9 nuclease, sgRNA, donor template |

| Template Design | Not applicable | Critical (homology arms: 0.8-1kb for dsDNA; 30-90nt for ssODN) |

| Typical Efficiency | High (varies by cell type) | Low to moderate (varies by cell type and locus) |

| Validation Approach | INDEL detection (T7E1, TIDE, sequencing) | Specific modification confirmation (PCR, sequencing) |

| Common Challenges | Off-target effects | Low efficiency, random integration |

| Optimal Cell State | Proliferating or non-dividing cells | Actively dividing cells (S/G2 phase) |

Advanced HDR Enhancement Methodologies

Overcoming Efficiency Limitations

The naturally lower efficiency of HDR compared to NHEJ has prompted the development of sophisticated strategies to enhance precise editing outcomes. These methodologies focus on shifting the cellular repair balance toward HDR:

Cell Cycle Synchronization: Since HDR is naturally restricted to S and G2 phases, synchronizing cells to these phases can significantly improve HDR efficiency. This can be achieved through chemical treatments such as thymidine-aphidicolin block or serum starvation and refeeding [18].

NHEJ Pathway Inhibition: Suppressing key NHEJ factors through chemical inhibitors or RNA interference can reduce competition with HDR. Small molecule inhibitors targeting DNA-PKcs (e.g., NU7441, KU0060648), 53BP1, or Ligase IV have shown promise in enhancing HDR efficiency [24]. However, recent studies indicate that some NHEJ inhibitors, particularly DNA-PKcs inhibitors, may increase the risk of large structural variations and chromosomal translocations, requiring careful evaluation of this approach [25].

Engineered HDR Promoters: Genetic engineering approaches have identified and enhanced natural HDR factors. For instance, expression of an engineered RAD18 variant (e18) has been shown to stimulate CRISPR-mediated HDR by suppressing the localization of the NHEJ-promoting factor 53BP1 to DSBs [24]. Similarly, dominant-negative 53BP1 mutants and Cas9-CtIP fusions have demonstrated improved HDR outcomes across multiple cell types [24].

Donor Template Design and Delivery

Optimizing the donor template is crucial for successful HDR experiments:

Template Format Selection: Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) are ideal for introducing point mutations or short tags, while double-stranded DNA donors (with 0.8-1kb homology arms) are better suited for larger insertions [24].

Homology Arm Length: For ssODN templates, 30-90 nucleotide homology arms typically provide optimal results, while dsDNA templates require longer homology arms (0.8-1kb) for efficient recombination [24].

Strategic Placement: Positioning the desired edit as close as possible to the Cas9 cleavage site significantly improves incorporation efficiency, as resection extends asymmetrically from the break [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Genome Editing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks at target sites | Can be delivered as protein, mRNA, or plasmid; quality affects efficiency |

| Guide RNA (sgRNA) | Targets Cas9 to specific genomic loci | Design critical for specificity; can be synthesized or transcribed in vitro |

| Donor Template | Provides homologous sequence for HDR | Format (ssODN vs. dsDNA) depends on edit size; homology arms essential |

| NHEJ Inhibitors | Shifts repair balance toward HDR | Chemical inhibitors (e.g., SCR7) or genetic approaches (e.g., dn53BP1) |

| HDR Enhancers | Promotes homologous recombination | Engineered factors (e.g., e18, RAD52) improve precise editing efficiency |

| Delivery Vehicle | Introduces editing components into cells | Viral vectors, electroporation, lipofection, or microinjection |

Emerging Safety Considerations and Future Directions

As CRISPR technologies advance toward clinical applications, understanding and mitigating potential risks becomes increasingly important. Recent studies have revealed that CRISPR editing can induce not only small indels but also large structural variations (SVs), including chromosomal translocations and megabase-scale deletions [25]. These unintended genomic alterations raise substantial safety concerns for therapeutic applications.

Notably, some HDR-enhancing strategies, particularly those involving DNA-PKcs inhibitors, have been associated with exacerbated genomic aberrations, including increased frequencies of large deletions and chromosomal translocations [25]. These findings highlight the complex trade-offs between editing efficiency and genomic integrity that researchers must consider when designing experiments.

Future directions in the field include the development of more refined precision editing tools, such as base editors and prime editors, which can modify DNA without creating DSBs, thereby potentially reducing unwanted genomic alterations [26] [25]. Additionally, improved analytical methods that can detect large structural variations are becoming essential for comprehensive evaluation of editing outcomes [25].

Visualizing DNA Repair Pathways and Experimental Workflows

DNA Repair Pathway Selection Following CRISPR-Induced DNA Break

Experimental Workflow for Pathway Selection and Optimization

The discovery of the CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering, enabling targeted genome modification across diverse cell types and organisms. While Cas9 facilitates gene disruption via double-strand breaks (DSBs), its reliance on error-prone repair pathways can lead to undesirable outcomes such as insertions/deletions (indels) and chromosomal rearrangements. This review details the mechanisms, applications, and methodologies of two advanced precision gene editors that overcome these limitations: base editing and prime editing. These technologies allow for precise nucleotide changes without requiring DSBs or donor DNA templates, significantly expanding the therapeutic potential of CRISPR-based technologies for correcting pathogenic genetic variants.

Traditional CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing operates by inducing a site-specific double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA, which is subsequently repaired by the cell's endogenous repair mechanisms. The two primary repair pathways are non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), an error-prone process that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the target gene, and homology-directed repair (HDR), which can incorporate a donor DNA template to achieve precise edits [18]. However, the efficiency of HDR is typically low, especially in non-dividing cells, and the concurrent activity of NHEJ often results in a high frequency of indels at the target site [27].

A significant proportion of human genetic diseases are caused by single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), accounting for an estimated 58% of known pathogenic genetic variants [28]. Correcting these point mutations requires a level of precision that is challenging to achieve with standard Cas9. Furthermore, the generation of DSBs carries an inherent risk of chromosomal abnormalities and genotoxicity. These limitations have driven the development of newer, more precise editing tools that can directly rewrite genetic information without creating DSBs, namely base editing and prime editing [29] [27].

Base Editing

Mechanism of Action

Base editing is a CRISPR-based technology that directly converts one DNA base into another at a target genomic locus without making a DSB. A base editor is a fusion protein consisting of a catalytically impaired Cas protein (such as a nickase, nCas9, or dead Cas9, dCas9) and a deaminase enzyme [28] [30]. The complex is guided to a specific DNA sequence by a guide RNA (gRNA). Once bound, the Cas protein partially unwinds the DNA, creating an R-loop that exposes a single-stranded DNA region to the deaminase. The deaminase then chemically modifies a specific base within a defined "editing window" [30].

There are two primary classes of base editors:

Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs): These editors use a cytidine deaminase (e.g., APOBEC1) to convert cytosine (C) into uracil (U). The cell's DNA replication and repair machinery then interpret this U as a thymine (T), ultimately effecting a C•G to T•A base pair conversion. To prevent the cell's base excision repair (BER) pathway from reversing this change, CBEs are often fused with a uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) [28] [30]. The first CBE, BE3, was developed in 2016 [28].

Adenine Base Editors (ABEs): ABEs perform an A•T to G•C conversion. Since no natural DNA adenine deaminase was known, researchers engineered one from the E. coli tRNA adenosine deaminase (TadA). This engineered TadA deaminates adenine (A) to inosine (I), which is read as guanine (G) by DNA polymerases. ABEs typically function as heterodimers, incorporating both a wild-type and an engineered TadA monomer for optimal efficiency [28] [30]. The first ABE, ABE7.10, was reported in 2017 [28].

The use of a Cas9 nickase (nCas9) that cuts the non-edited DNA strand further improves editing efficiency by directing the cellular mismatch repair system to preferentially replace the non-edited base, thereby favoring the incorporation of the new base [30].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of a cytosine base editor (CBE):

Base Editing Mechanism (CBE)

Experimental Protocol for Base Editing

A typical workflow for a base editing experiment in mammalian cells is outlined below.

Step 1: gRNA Design and Cloning

- Design gRNAs so that the target base is positioned within the editing window of the base editor (typically nucleotides 4-8 for SpCas9-based editors, counting from the PAM-distal end) [28].

- Select the appropriate base editor: Choose a CBE (e.g., BE4max) for C-to-T edits or an ABE (e.g., ABE8e) for A-to-G edits, considering the specific PAM requirements of the Cas variant used.

- Clone the selected gRNA sequence into a plasmid vector that will express the gRNA in your target cells.

Step 2: Delivery of Base Editing Components

- Transfect or transduce the target cells with the base editor and gRNA constructs. Common delivery methods include:

- Plasmid Transfection: Co-transfect a plasmid expressing the base editor with a plasmid expressing the gRNA.

- mRNA/gRNA Electroporation: Deliver in vitro transcribed mRNA encoding the base editor along with synthetic gRNA via electroporation for more transient expression.

- Viral Delivery: Use lentiviral or adenoviral vectors (AdV) for harder-to-transfect cells. Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are challenging for full-length base editors due to packaging size constraints but can be used with dual-vector systems or smaller Cas orthologs [27].

Step 3: Analysis of Editing Outcomes

- Harvest genomic DNA from treated cells 48-72 hours post-delivery.

- Amplify the target genomic region by PCR.

- Sequence the PCR amplicons using Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing (NGS) to quantify editing efficiency and assess purity (the proportion of desired edits versus bystander edits within the window).

- Analyze for potential off-target effects using methods like whole-genome sequencing or targeted sequencing of sites nominated by in silico prediction tools [31].

Research Reagent Solutions for Base Editing

The table below lists essential reagents required for a base editing experiment.

| Research Reagent | Function & Description |

|---|---|

| Base Editor Plasmid | Expresses the fusion protein (e.g., nCas9-deaminase-UGI for CBE). Available from nonprofit repositories (Addgene) or commercial suppliers [28]. |

| gRNA Expression Plasmid | A vector containing the U6 promoter for expression of the sgRNA. The gRNA sequence is cloned into this plasmid. |

| Delivery Reagents | Chemical transfection reagents (e.g., lipofection), electroporation kits, or viral packaging systems (lentivirus, AdV) for introducing constructs into cells. |

| Target Cell Line | The mammalian cell line intended for editing (e.g., HEK293T, primary T cells, iPSCs). |

| PCR & NGS Reagents | Primers for amplifying the target locus, PCR master mix, and kits for preparing NGS libraries to analyze editing outcomes. |

Prime Editing

Mechanism of Action

Prime editing is a "search-and-replace" genome editing technology that can mediate all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, without requiring DSBs or donor DNA templates [32] [33]. A prime editor is a fusion protein consisting of a Cas9 nickase (H840A) and an engineered reverse transcriptase (RT) [32] [34]. The system is guided by a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA), which both specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit.

The multi-step mechanism of prime editing is as follows:

- Targeting and Nicking: The prime editor complex binds to the target DNA site as directed by the spacer sequence of the pegRNA. The Cas9 nickase nicks the DNA strand containing the PAM sequence (the "PAM strand") [34].

- Hybridization and Reverse Transcription: The 3' end of the nicked DNA strand hybridizes with the primer binding site (PBS) on the pegRNA. The reverse transcriptase then uses the RT template sequence of the pegRNA to synthesize a new DNA flap containing the desired edit(s) [32] [33].

- Flap Resolution and Incorporation: Cellular enzymes resolve the resulting DNA structure, which features a 5' flap (the original, unedited sequence) and a 3' flap (the newly synthesized, edited sequence). The cell preferentially incorporates the 3' edited flap [34].

- Repair of the Complementary Strand: The edited strand now contains the new sequence, while the complementary strand remains unedited, creating a heteroduplex. To permanently install the edit, a second nicking sgRNA can be supplied (in the PE3/PE3b systems) to nick the non-edited strand. This encourages the cell's mismatch repair system to use the edited strand as a template, resulting in a stable, fully edited DNA duplex [32] [33].

The following diagram illustrates this multi-step process:

Prime Editing Mechanism

Experimental Protocol for Prime Editing

Implementing prime editing requires careful optimization of several components. A standard protocol is described below.

Step 1: pegRNA Design and Cloning

- Design the pegRNA spacer sequence to bind the target site. The PAM sequence must be present on the strand that will be nicked.

- Design the RT template sequence to be ~10-16 nucleotides long and include the desired edit(s) in the center. The template must also include downstream homology to facilitate flap alignment.

- Design the PBS sequence to be ~8-15 nucleotides long, with a melting temperature (Tm) of approximately 30°C, to ensure efficient primer binding [33] [34].

- Clone the pegRNA sequence into an appropriate expression vector. Consider using engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) with 3' RNA structural motifs to enhance stability and increase editing efficiency [33].

Step 2: Delivery of Prime Editing Components

- Co-deliver the prime editor and pegRNA expression constructs into target cells. Given the large size of the PE and the pegRNA, efficient delivery is a key challenge.

- Plasmid Transfection: Suitable for easily transfected cell lines.

- mRNA/pegRNA Electroporation: Delivering PE as mRNA and pegRNA as synthetic RNA can improve efficiency and reduce off-target effects in primary cells.

- Viral Delivery: Lentiviral vectors can be used, but AAVs require splitting the system due to size constraints (e.g., using dual AAVs or smaller Cas orthologs) [34].

- For higher efficiency (PE3 system), co-deliver a second sgRNA expression construct designed to nick the non-edited strand after the initial edit is installed [32].

Step 3: Analysis and Optimization

- Analyze editing efficiency as described for base editing (PCR followed by Sanger sequencing or NGS).

- Optimize the system if efficiency is low. This can involve testing pegRNAs with different PBS lengths and RT template designs, using epegRNAs, or employing advanced PE systems like PE4 or PE5, which incorporate a dominant-negative mismatch repair protein (MLH1dn) to temporarily inhibit MMR and boost efficiency [33].

Research Reagent Solutions for Prime Editing

The table below lists essential reagents for a prime editing experiment.

| Research Reagent | Function & Description |

|---|---|

| Prime Editor Plasmid | Expresses the fusion protein (nCas9-Reverse Transcriptase). Common versions include PE2, PEmax, PE4, and PE5 [33]. |

| pegRNA Expression Plasmid | A vector for expressing the complex pegRNA. The pegRNA sequence (spacer, scaffold, PBS, RT template) is cloned into this plasmid. |

| sgRNA Plasmid (for PE3) | For the PE3 system, a second plasmid expressing a standard sgRNA to nick the non-edited strand. |

| Delivery Reagents | Electroporation systems (e.g., Neon, Amaxa) or chemical transfection reagents optimized for large mRNA/RNA or plasmid DNA. |

| Target Cell Line | The cell type for editing; efficiency can vary significantly between cell lines. |

| Sequencing & Analysis Tools | NGS platforms and bioinformatics pipelines for deep sequencing to assess precise editing outcomes and indel byproducts. |

Comparative Analysis of Advanced Editing Systems

The table below provides a direct comparison of the capabilities and characteristics of Cas9, base editing, and prime editing.

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 (HDR) | Base Editing | Prime Editing |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Cleavage | Double-strand break (DSB) | Single-strand nick (or no cut) | Single-strand nick |

| Typical Editing Outcome | Insertions, deletions (NHEJ); precise edits with donor (HDR) | Point mutations: C>G, G>A (CBE); T>C, A>G (ABE) | All 12 base substitutions, small insertions, small deletions |

| Efficiency of Precise Edit | Low (HDR typically <10%) | Moderate to high | Variable; often lower than base editing |

| DSB-Related Byproducts | High (indels, translocations) | Very low | Low |

| Donor DNA Template Required | Yes (for HDR) | No | No (the pegRNA acts as the template) |

| Editing Window / PAM Constraint | Constrained by PAM location | Constrained by editing window (~4-8 bp) and PAM | Less constrained; edits can be >30 bp from PAM |

| Bystander Edits | Not applicable | Possible (edits of same base type in window) | No (edits are specific to the RT template design) |

| Therapeutic Potential | Moderate (limited by HDR efficiency) | High for specific SNVs (therapies in clinical trials) | Very high (can address ~89% of known pathogenic SNVs) |

Base editing and prime editing represent significant leaps forward in the field of precision genome editing. By moving beyond the requirement for double-strand breaks, these technologies offer a safer and more precise means of correcting disease-causing mutations. Base editors provide a highly efficient solution for specific transition mutations, while prime editors offer unparalleled versatility in the types of edits they can introduce. Ongoing research focuses on improving the efficiency, delivery, and specificity of these tools. As these technologies continue to mature, they hold immense promise for developing transformative therapies for a wide spectrum of genetic diseases, paving the way for a new era in genetic medicine.

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) systems represent a revolutionary genome engineering technology derived from bacterial adaptive immune systems. These systems protect bacteria from invading viruses by storing snippets of viral DNA in their own genomes, which then serve as guides to recognize and cleave matching foreign DNA sequences upon re-exposure. Scientists have harnessed this natural system to create a programmable genome editing tool that enables precise modification of DNA sequences in virtually any organism. The core CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two fundamental components: a Cas nuclease that functions as molecular scissors to cut DNA, and a guide RNA (gRNA) that directs the nuclease to a specific genomic target sequence. This simple yet powerful architecture has democratized genome editing, making what was once a complex, specialized technique accessible to researchers across biological disciplines.

The transformative potential of CRISPR technology extends far beyond basic research into therapeutic applications for genetic diseases. Before CRISPR, gene editing approaches like zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) required researchers to design and generate custom protein pairs for every genomic target, a process that was both time-consuming and expensive. CRISPR's comparative simplicity—where changing target specificity only requires designing a new RNA guide sequence—has dramatically accelerated the pace of biological research and therapeutic development. This technical overview traces the key milestones from the initial discovery of CRISPR mechanisms to the first FDA-approved CRISPR therapy, providing new researchers with essential context for understanding this rapidly evolving field.

Historical Development of CRISPR Technology

The development of CRISPR from a curious genetic sequence to a precision genome editing tool spans several decades of international scientific discovery. This timeline highlights the key breakthroughs that enabled the current CRISPR revolution.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in CRISPR Development

| Year | Key Discovery | Lead Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Unusual repetitive DNA sequences observed | Japanese researchers (Osaka University) | First documented discovery of what would later be recognized as CRISPR [35] |

| 2000-2005 | CRISPR characterized as bacterial immune system | Francisco Mojica, Alexander Bolotin | Recognition of CRISPR as adaptive immunity with spacers derived from foreign DNA [36] [37] |

| 2007 | Experimental demonstration of adaptive immunity | Philippe Horvath (Danisco) | First experimental proof that CRISPR provides resistance against viruses in bacteria [36] [37] |

| 2011 | tracrRNA discovery | Emmanuelle Charpentier | Identification of trans-activating CRISPR RNA essential for Cas9 function [36] |

| 2012 | CRISPR-Cas9 as programmable gene editing system | Charpentier & Doudna; Siksnys | Biochemical characterization demonstrating reprogrammable DNA cleavage [36] [35] |

| 2013 | First eukaryotic genome editing | Feng Zhang; George Church | Adaptation of CRISPR-Cas9 for use in human and mouse cells [36] [37] |

The initial discovery phase (1987-2007) began with the identification of unusual repetitive DNA structures in prokaryotes. Francisco Mojica at the University of Alicante played a pivotal role in recognizing these sequences as a distinct class present across diverse microorganisms and hypothesizing their function in microbial immunity. Between 2005-2007, multiple research groups independently established that these CRISPR sequences indeed functioned as an adaptive immune system, with Alexander Bolotin discovering the Cas9 protein and its associated PAM sequence, and Philippe Horvath providing the first experimental demonstration in Streptococcus thermophilus.

The tool development phase (2011-2013) transformed this bacterial immunity system into a programmable genome editing technology. The critical discovery of tracrRNA by Emmanuelle Charpentier in 2011 completed our understanding of the natural Cas9 complex. In 2012, teams led by Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, along with Virginijus Siksnys, concurrently published papers demonstrating how the system could be engineered for programmable DNA cleavage. Their work showed that the crRNA and tracrRNA could be fused into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), dramatically simplifying the system for practical applications. The following year, teams led by Feng Zhang and George Church independently published the first demonstrations of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in eukaryotic cells, establishing the technology as a transformative tool for genetic research and therapeutic development.

Core CRISPR Mechanism and Methodology

Molecular Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

The CRISPR-Cas9 system requires two fundamental molecular components for targeted DNA modification. First, the Cas9 endonuclease serves as the executive component that creates double-strand breaks in DNA. The most commonly used Cas9 enzyme is derived from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), which contains two nuclease domains: HNH, which cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the guide RNA, and RuvC, which cleaves the non-complementary strand. Second, the guide RNA (gRNA) provides the targeting specificity through complementary base pairing. The gRNA is a chimeric RNA molecule comprising a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) component that contains the ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence complementary to the target DNA, and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) that serves as a scaffolding backbone for Cas9 binding.

A critical requirement for Cas9 recognition and cleavage is the presence of a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence immediately adjacent to the target site. For SpCas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" represents any nucleotide. The PAM is not part of the guide RNA target sequence but is essential for Cas9 activation. Upon encountering a PAM sequence, Cas9 undergoes a conformational change that enables DNA unwinding and subsequent RNA-DNA hybridization. If the guide RNA sequence demonstrates sufficient complementarity to the target DNA, particularly in the 8-12 base "seed sequence" proximal to the PAM, Cas9 activates its nuclease domains to create a blunt-ended double-strand break approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence.

DNA Repair Mechanisms and Editing Outcomes

The cellular response to CRISPR-induced double-strand breaks determines the final editing outcome. Cells primarily utilize two distinct DNA repair pathways:

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): This dominant repair pathway in most mammalian cells directly ligates the broken DNA ends without a template. NHEJ is error-prone, frequently resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site. When these indels occur within protein-coding sequences, they often produce frameshift mutations that disrupt the open reading frame, leading to premature stop codons and effective gene knockout. NHEJ is highly efficient and suitable for gene disruption applications.

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): This pathway uses a homologous DNA template to precisely repair the break. By providing an exogenous donor template with homologous arms flanking the desired modification, researchers can harness HDR to introduce specific sequence changes, including point mutations, gene insertions, or reporter tags. HDR occurs at significantly lower frequencies than NHEJ and is cell cycle-dependent, primarily occurring in the S and G2 phases, making precise genome editing more challenging.

Experimental Workflow for CRISPR Genome Editing

A standard CRISPR experiment follows a systematic workflow encompassing design, editing, and analysis phases:

Design Phase: Researchers identify target genomic loci and design gRNA sequences using specialized bioinformatics tools. Optimal gRNAs demonstrate perfect complementarity to the intended target while minimizing similarity to off-target sites elsewhere in the genome. Computational algorithms help predict gRNA efficiency and specificity, with considerations for GC content, position within the gene, and absence of polymorphic nucleotides in the target sequence.

Editing Phase: The CRISPR components are delivered to target cells using appropriate methods. For most in vitro applications, plasmid DNA encoding both Cas9 and gRNA sequences is transfected into cells. For more sensitive primary cells or in vivo applications, Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes can be directly delivered, reducing off-target effects and enabling faster editing. The choice of delivery method depends on cell type, efficiency requirements, and application.

Analysis Phase: Editing efficiency is validated using various molecular techniques. The T7 Endonuclease I assay or Surveyor assay detects mismatched DNA heteroduplexes formed between wild-type and edited sequences. For precise quantification of editing rates, next-generation sequencing provides the most comprehensive analysis, revealing the spectrum of induced mutations and potential off-target events.

The Path to Clinical Application

First FDA-Approved CRISPR Therapy: Casgevy

In December 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel), marking a historic milestone as the first CRISPR-based gene therapy to receive regulatory authorization [38]. Developed through collaboration between Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR Therapeutics, Casgevy is approved for treating sickle cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia (TBT) in patients 12 years and older.

Casgevy employs an ex vivo approach where a patient's own hematopoietic stem cells are collected and genetically modified outside the body. Using CRISPR-Cas9, the BCL11A gene is precisely edited at its erythroid-specific enhancer region. BCL11A encodes a transcriptional repressor that normally suppresses fetal hemoglobin (HbF) production after birth. By disrupting this repressor, the edited stem cells produce elevated levels of HbF, which does not sickle and can effectively compensate for the defective adult hemoglobin in SCD patients [38].

The approval was based on compelling clinical trial results. In the pivotal trial for sickle cell disease, 29 of 31 evaluable patients (93.5%) achieved freedom from severe vaso-occlusive crises for at least 12 consecutive months during the 24-month follow-up period. All treated patients achieved successful engraftment with no instances of graft failure or rejection. The safety profile was manageable, with the most common side effects including low levels of platelets and white blood cells, mouth sores, nausea, musculoskeletal pain, abdominal pain, vomiting, febrile neutropenia, headache, and itching [38].

Table 2: Clinical Trial Results for FDA-Approved CRISPR Therapies

| Therapy | Indication | Trial Design | Efficacy Results | Common Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casgevy | Sickle Cell Disease | Single-arm, multi-center trial (44 patients) | 29/31 (93.5%) free from severe vaso-occlusive crises for ≥12 months | Thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, stomatitis, nausea, musculoskeletal pain |

| Casgevy | Transfusion-Dependent Beta Thalassemia | Single-arm, multi-center trial | Significant reduction or elimination of transfusion requirements | Similar to SCD profile |

| Lyfgenia | Sickle Cell Disease | Single-arm, 24-month multicenter study (32 patients) | 28/32 (88%) achieved complete resolution of vaso-occlusive events | Stomatitis, cytopenias, febrile neutropenia; includes boxed warning for hematologic malignancy |

Concurrently, the FDA approved Lyfgenia (lovotibeglogene autotemcel), a lentiviral vector-based gene therapy that modifies a patient's hematopoietic stem cells to produce HbAT87Q, a gene-therapy-derived hemoglobin that functions similarly to normal adult hemoglobin but with reduced sickling potential [38]. Both therapies represent significant advances in the treatment of hemoglobinopathies, offering potentially curative options for conditions that were previously managed only symptomatically.

Expanding Clinical Applications

The success of Casgevy has accelerated clinical development of CRISPR therapies across diverse disease areas. Notable advances include:

Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (hATTR): Intellia Therapeutics has pioneered the first systemic in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 therapy administered intravenously. Unlike ex vivo approaches, this treatment uses lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) to deliver CRISPR components directly to liver cells, reducing production of the misfolded transthyretin (TTR) protein that causes disease. Clinical trials demonstrated rapid, deep (∼90%), and sustained reduction in TTR protein levels with a favorable safety profile [7].

Hereditary Angioedema (HAE): Using similar LNP delivery technology, Intellia is testing a CRISPR therapy that reduces levels of kallikrein, a key mediator of inflammatory attacks in HAE. Phase I/II results showed an 86% reduction in kallikrein and significant reduction in the number of attacks, with 8 of 11 participants in the high-dose group attack-free during the 16-week study period [7].

Oncology Applications: CRISPR-based approaches are advancing cancer immunotherapy, particularly allogeneic CAR-T cell therapies. CRISPR Therapeutics has developed CTX112, an allogeneic CAR T-product targeting CD19+ B-cell malignancies, which incorporates edits designed to evade the immune system, enhance potency, and reduce T-cell exhaustion. Preliminary data show strong efficacy with a tolerable safety profile, earning the therapy RMAT (Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy) designation from the FDA [39].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful CRISPR experimentation requires carefully selected molecular tools and reagents. The following table outlines essential components for designing and implementing CRISPR studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nucleases | SpCas9, SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9, Cas12a (Cpf1) | DNA cleavage; high-fidelity variants reduce off-target effects; different PAM specificities |

| Guide RNA Vectors | U6-promoter driven sgRNA plasmids, tRNA-gRNA arrays | gRNA expression; multiplexed targeting approaches |

| Delivery Systems | Lentiviral particles, electroporation, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) | Introduction of CRISPR components into cells; choice depends on cell type and application |

| Validation Tools | T7E1 assay, Surveyor assay, NGS platforms | Assessment of editing efficiency and specificity |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Cytokines, selection antibiotics, serum-free media | Maintenance and expansion of edited cells, particularly for stem cell applications |

The selection of appropriate Cas enzyme variants is critical for experimental success. While wild-type SpCas9 remains widely used, high-fidelity variants like HypaCas9 and eSpCas9(1.1) offer reduced off-target editing while maintaining robust on-target activity. For specialized applications, Cas12a provides alternative PAM requirements and staggered DNA cuts beneficial for certain editing approaches. Guide RNA design has been streamlined through bioinformatics platforms that predict on-target efficiency and potential off-target sites, with algorithms continually improving through machine learning approaches.

Delivery method optimization depends on the target cell type and application. Plasmid transfection works well for easily transfectable cell lines, while lentiviral transduction provides efficient delivery for difficult-to-transfect primary cells. For the highest editing efficiency with minimal off-target effects, preassembled Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes delivered via electroporation have emerged as the gold standard for clinical applications. Recent advances in lipid nanoparticle (LNP) technology have enabled efficient in vivo delivery, expanding CRISPR applications to direct therapeutic interventions.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The CRISPR field continues to evolve rapidly with several emerging trends shaping future research and clinical applications. Artificial intelligence is playing an increasingly important role in experimental design, with tools like CRISPR-GPT—an AI copilot developed at Stanford Medicine—helping researchers generate optimized designs, analyze data, and troubleshoot experiments [8]. This AI assistance is particularly valuable for flattening the learning curve for new researchers and accelerating the therapeutic development timeline.

Delivery technologies represent another area of intense innovation. While viral vectors remain important for ex vivo applications, non-viral delivery methods—particularly lipid nanoparticles (LNPs)—have demonstrated remarkable success for in vivo therapies. The ability to administer multiple doses of LNP-encapsulated CRISPR components without triggering significant immune responses represents a significant advantage over viral delivery methods [7]. Researchers are also developing novel LNPs with tropism for organs beyond the liver, which would dramatically expand the treatable disease spectrum.

The clinical landscape for CRISPR therapies continues to broaden beyond monogenic diseases. Cardiovascular applications are showing particular promise, with therapies targeting angiopoietin-related protein 3 (ANGPTL3) for hypercholesterolemia and LPA for elevated lipoprotein(a) advancing through clinical trials [39]. These programs demonstrate the potential of CRISPR to address common polygenic conditions with significant public health impact. Additionally, the successful development of a personalized CRISPR treatment for an infant with CPS1 deficiency—from design to delivery in just six months—establishes a precedent for rapid development of bespoke therapies for ultra-rare genetic disorders [7].

Despite these promising developments, challenges remain in the CRISPR therapeutic landscape. Manufacturing complexities, reimbursement strategies for high-cost therapies, and ensuring equitable access represent significant hurdles. Additionally, the field continues to navigate appropriate safety safeguards, particularly for in vivo applications. However, the unprecedented pace of innovation in CRISPR technology suggests these challenges will likely be addressed as the field matures, potentially ushering in a new era of genetic medicine with CRISPR at its core.

CRISPR in Action: Research and Therapeutic Applications from Bench to Bedside

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) system, originally identified as a bacterial immune mechanism, has emerged as a revolutionary tool for precision genome editing in cancer research [40]. This technology enables researchers to target specific genetic mutations that drive tumor growth and manipulate immune cell functions to enhance anticancer activity. The core mechanism involves a Cas nuclease directed by a guide RNA (gRNA) to recognize and cleave specific DNA sequences via Watson-Crick base pairing, creating double-strand breaks (DSBs) that activate cellular DNA repair pathways [25]. The system's precision, efficiency, and programmability have transformed oncology research, allowing for the functional interrogation of cancer genomes and the development of innovative therapies that were not possible with earlier gene-editing technologies like zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) [41] [42].

Cancer is fundamentally a genetic disease caused by accumulated mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. CRISPR technology provides an unprecedented ability to model these mutations, study their functional consequences, and develop targeted interventions [43]. The application of CRISPR in oncology spans multiple domains: identifying genetic dependencies through genome-wide screens, creating precise cellular and animal models of tumorigenesis, developing engineered immune cells for immunotherapy, and directly targeting cancer-driving genes [42]. This technical guide explores the core mechanisms of CRISPR systems and their specific applications in inactivating oncogenes and enhancing cancer immunotherapies, providing both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for researchers entering this rapidly advancing field.

Molecular Mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas Systems

Core Components and Mechanisms

The CRISPR-Cas system operates through a relatively simple yet powerful mechanism comprising two core components: the Cas nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA). The gRNA is a synthetic RNA chimera that combines the functions of the naturally occurring crRNA (CRISPR RNA) and tracrRNA (trans-activating crRNA) [42]. The crRNA segment contains a 20-base pair spacer sequence that is complementary to the target DNA, enabling precise recognition through base pairing, while the tracrRNA serves as a scaffold that facilitates the binding of the crRNA to the Cas protein [40]. The Cas nuclease-gRNA complex scans the genome for protospacer adjacent motifs (PAMs), short DNA sequences adjacent to the target site that are essential for recognition. Once the complex identifies a matching sequence with the correct PAM, the Cas nuclease induces a double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA [25].