CRISPR Gene Editing: Principles, Applications, and Optimization for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to CRISPR gene-editing technology, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

CRISPR Gene Editing: Principles, Applications, and Optimization for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to CRISPR gene-editing technology, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of CRISPR-Cas systems, from its origins as a bacterial immune mechanism to its function as a programmable DNA-editing tool. The content explores advanced methodological applications in functional genomics and therapy development, details practical strategies for troubleshooting common challenges like off-target effects and editing efficiency, and offers a comparative analysis with traditional gene-editing platforms. The goal is to equip scientists with both the theoretical understanding and practical knowledge needed to effectively implement CRISPR in research and translational medicine.

The CRISPR Revolution: From Bacterial Immunity to a Programmable Genome Editor

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and their CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins function as a sophisticated adaptive immune system in prokaryotes, enabling bacteria and archaea to defend themselves against invasive genetic elements such as viruses and plasmids [1]. This defense system provides a genetic record of past infections, allowing the host to recognize and eliminate recurring threats with remarkable sequence specificity [2]. The discovery that single-celled organisms possess an adaptive, heritable immune system has fundamentally transformed our understanding of microbe-virus interactions and was later repurposed to revolutionize genetic engineering [1].

The CRISPR-Cas system is characterized by specific DNA loci consisting of short, repetitive sequences interspersed with unique "spacer" sequences derived from previous invaders [1]. These loci are accompanied by Cas genes that encode the protein machinery for system function. Comparative genomic analyses reveal that approximately 40% of sequenced bacteria and over 80% of archaea possess at least one CRISPR-Cas system [1], highlighting its widespread importance in prokaryotic biology.

Molecular Mechanism of CRISPR Adaptive Immunity

The adaptive immune function of CRISPR-Cas systems operates through three distinct, sequential stages: adaptation, expression, and interference. These stages work in concert to provide a dynamic defense mechanism that can adapt to new threats and mount targeted responses against recurrent infections.

Stage 1: Adaptation - Capturing Genetic Memories

The adaptation phase, also called spacer acquisition, represents the immunological memory formation stage where the system captures molecular signatures of invading genetic elements. During this stage, specialized Cas proteins, primarily the Cas1-Cas2 integrase complex, recognize and process foreign DNA from invading viruses or plasmids into short fragments called protospacers [1]. This complex then catalyzes the integration of these protospacers as new spacers into the CRISPR array within the host genome [3] [1]. The CRISPR array thereby accumulates a chronological record of infection events, serving as a genetic memory bank.

Recent research has elucidated that bacteria preferentially acquire spacers from viruses in a dormant state (lysogeny) rather than during active replication [2]. During this "viral nap," bacteria have increased opportunity to integrate viral DNA fragments, effectively "vaccinating" themselves against future infections [2]. This spacer acquisition mechanism represents a sophisticated form of molecular immunity, where the host organism adapts to its pathogenic environment at the genetic level.

Stage 2: Expression - Generating Targeting Molecules

In the expression stage, the CRISPR locus undergoes transcription, producing a long precursor CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA) [1]. This precursor is then processed by Cas proteins into short, mature crRNAs, each containing a single spacer sequence that serves as a guide for target recognition [4] [1]. In certain systems, such as Type II, a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) facilitates crRNA maturation [3]. Each mature crRNA assembles with one or more Cas proteins to form an effector complex, programming it for specific target recognition in the subsequent interference stage.

Stage 3: Interference - Neutralizing Invaders

The final interference stage represents the execution of immune function, where crRNA-guided effector complexes patrol the cell seeking complementary nucleic acid sequences from invading genetic elements [1]. Upon recognizing a target sequence matching its spacer, the effector complex initiates cleavage, leading to degradation of the invading DNA or RNA [4]. Most DNA-targeting systems require recognition of a short protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) flanking the target sequence, which helps distinguish self from non-self DNA and prevents autoimmunity [1]. This destruction neutralizes the threat, completing the adaptive immune response.

Classification of CRISPR-Cas Systems

CRISPR-Cas systems exhibit considerable diversity, leading to their formal classification into types and subtypes based on their genetic architecture, Cas protein composition, and mechanistic features. The following table summarizes the current classification framework based on the most recent comprehensive analysis.

Table 1: Updated Classification of CRISPR-Cas Systems (2025)

| Class | Type | Signature Protein | Target Molecule | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (Multi-subunit effector complexes) | I | Cas3 | DNA | Multi-protein cascade complex with separate nuclease [5] [1] |

| III | Cas10 | DNA/RNA | Involves cyclic oligoadenylate (cOA) signaling; targets both nucleic acids [5] | |

| IV | CasDinG (Csf1) | DNA | Variable adaptation modules; some variants cleave DNA [5] | |

| VII | Cas14 | RNA | Metall-β-lactamase (β-CASP) effector nuclease; targets RNA [5] | |

| Class 2 (Single-protein effectors) | II | Cas9 | DNA | Uses tracrRNA; requires NGG PAM; most widely used in biotechnology [3] [4] |

| V | Cas12 | DNA | Single RuvC-like nuclease domain; targets DNA [4] | |

| VI | Cas13 | RNA | Targets RNA rather than DNA; used in diagnostic applications [4] |

The classification continues to expand with ongoing discovery, with the most recent update identifying 2 classes, 7 types, and 46 subtypes, compared to 6 types and 33 subtypes in the previous classification five years ago [5]. This diversity reflects the evolutionary arms race between prokaryotes and their viral predators across different ecological niches.

Experimental Approaches for Studying CRISPR Function

Research into CRISPR-Cas systems employs sophisticated experimental approaches to elucidate molecular mechanisms and explore system functionalities. The following methodology represents a contemporary approach for investigating spacer acquisition dynamics.

Protocol: Investigating Spacer Acquisition from Lysogenic Phages

Background: This protocol is adapted from recent research published in Cell Host & Microbe that examined how bacteria preferentially acquire spacers from dormant viruses [2]. The methodology enables precise analysis of CRISPR adaptation dynamics under controlled infection conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Bacterial strain: Streptococcus pyogenes or other CRISPR-containing species

- Phage variants: Wild-type (capable of lysogeny) and genetically engineered mutants locked in lytic cycle

- Growth media: Appropriate sterile liquid and solid media for host strain

- Selection agents: Antibiotics for maintaining selective pressure if needed

- Molecular biology reagents: PCR components, primers, DNA sequencing reagents

- CRISPR array analysis tools: Sequencing primers targeting CRISPR locus flanks

Procedure:

- Culture preparation: Grow separate bacterial cultures to mid-logarithmic phase in appropriate liquid media.

- Phage infection: Infect experimental groups with wild-type phages (capable of lysogeny) and control groups with engineered phages (locked in lytic cycle) at equivalent multiplicity of infection (MOI).

- Recovery and selection: Allow infection to proceed for predetermined duration, then plate surviving cells on solid media to obtain isolated colonies.

- Genetic analysis: a. Ispace genomic DNA from multiple individual colonies for each condition. b. Amplify CRISPR loci using PCR with primers flanking the array. c. Sequence amplified products using Sanger or next-generation sequencing.

- Spacer identification: Bioinformatically identify newly acquired spacers by comparing to uninfected control sequences.

- Spacer source mapping: Align acquired spacer sequences to both phage and host genomes to determine origins.

- Functional validation: Challenge spacer-carrying bacteria with the same phages to evaluate immune protection.

Key considerations: Maintain appropriate controls throughout, including uninfected bacteria and isogenic bacterial strains differing only in CRISPR status. Standardize culture conditions and infection parameters across experiments to ensure reproducibility.

Signaling Pathways in Type III Systems

Type III CRISPR-Cas systems employ sophisticated signaling pathways that extend beyond direct target cleavage. These systems can initiate a generalized antiviral response through secondary messenger signaling.

Diagram 1: Type III CRISPR-Cas Antiviral Response

Some recently identified type III subtypes (III-G and III-H) show reductive evolution, where the polymerase/cyclase domain of Cas10 is inactivated, resulting in loss of cOA signaling capability while retaining DNA targeting function [5]. This reflects the dynamic evolutionary landscape of CRISPR-Cas systems.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The following table catalogs key reagents and materials essential for conducting experimental research on native CRISPR-Cas systems, particularly for studying their adaptive immune functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Native CRISPR-Cas Systems

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Examples/Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Cas1-Cas2 complex | Study of spacer acquisition mechanism | In vitro assays for protospacer integration [1] |

| Bacteriophage libraries | Sources of protospacers for adaptation studies | Investigating spacer acquisition preferences [2] |

| crRNA/tracrRNA molecules | RNA components for effector complex formation | Studying interference stage mechanisms [3] |

| Type III CRISPR systems | Research on cOA signaling pathways | Analyzing secondary messenger antiviral responses [5] |

| High-throughput screening platforms | Characterization of CAST system variants | Measuring activity and specificity of CRISPR-associated transposons [6] |

| Cas protein variants | Engineering enhanced specificity and activity | V-K CAST mutagenesis for improved genome editing [6] |

| Protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) libraries | Understanding target recognition constraints | Determining sequence requirements for interference [1] |

The CRISPR-Cas system represents a remarkable example of sophisticated adaptive immunity in prokaryotic organisms. Its three-stage mechanism—adaptation, expression, and interference—provides bacteria and archaea with a heritable, sequence-specific defense system against mobile genetic elements. The substantial diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems, now classified into 2 classes, 7 types, and 46 subtypes, reflects continuous evolutionary innovation in host-pathogen conflicts. Ongoing research continues to reveal new dimensions of these systems, from molecular details of spacer acquisition to signaling-mediated antiviral responses. This foundational understanding of CRISPR biology not only advances our knowledge of microbial immunity but also provides the essential framework for developing transformative biotechnological applications.

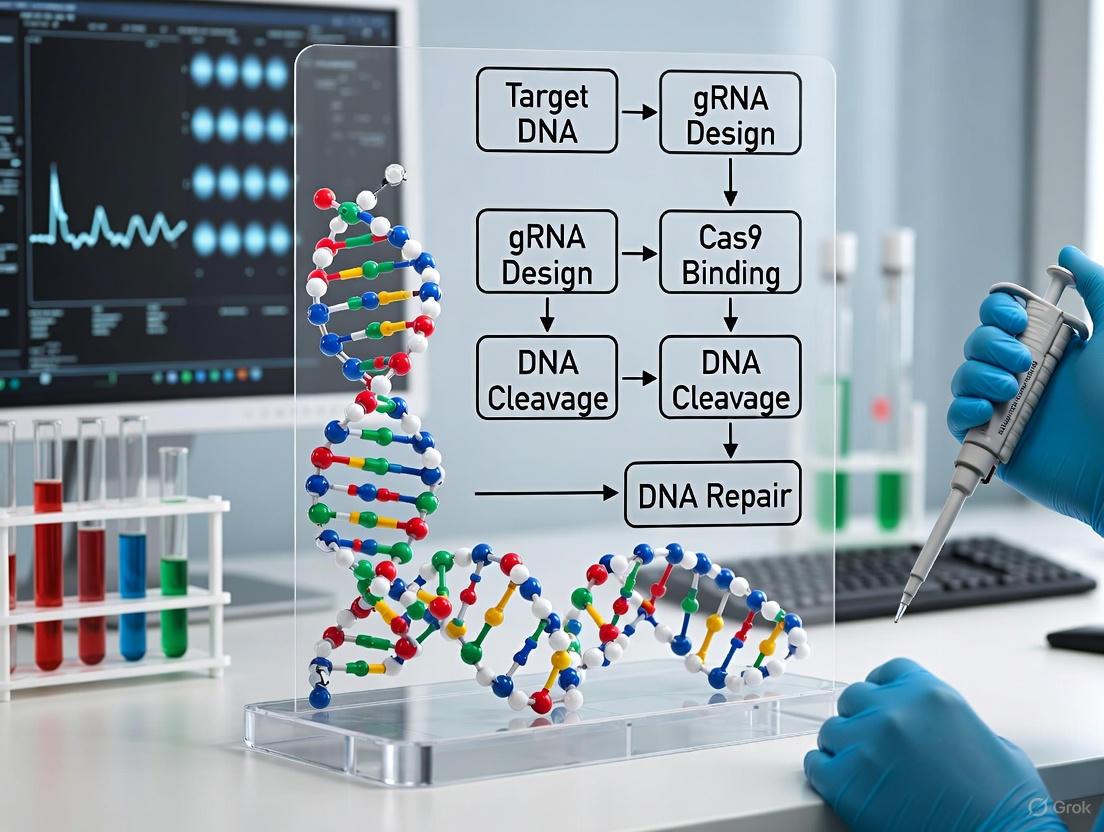

The CRISPR-associated (Cas) protein and guide RNA (gRNA) represent a revolutionary two-component system for precise genome editing. Derived from an adaptive immune system in bacteria, this duo functions as a programmable molecular machine that can be directed to specific locations in a genome to introduce double-stranded breaks in DNA [7] [8]. The core innovation lies in the separation of functions: the Cas protein serves as a nonspecific endonuclease engine, while the gRNA provides the targeting specificity through Watson-Crick base pairing [9] [8]. This modularity has enabled researchers to rapidly adopt and adapt the technology across diverse biological systems, from basic research to therapeutic development. The most extensively characterized system originates from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), which has become the foundational tool for most CRISPR applications [7] [9].

Structural Architecture of the Cas-gRNA Complex

The Cas9 protein exhibits a bilobed architecture composed of two primary lobes: a recognition lobe (REC) and a nuclease lobe (NUC) [7]. These lobes form a positively charged groove at their interface that accommodates the negatively charged sgRNA:DNA heteroduplex during target recognition and cleavage [7].

Table 1: Domain Architecture of S. pyogenes Cas9

| Lobe | Domain/Region | Residue Range | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition (REC) | Bridge Helix | 60-93 | Structural element connecting REC domains |

| REC1 | 94-179, 308-713 | Major interaction site for sgRNA and DNA | |

| REC2 | 180-307 | Non-essential α-helical bundle (can be partially deleted) | |

| Nuclease (NUC) | RuvC Domain | 1-59, 718-769, 909-1098 | Cleaves non-target DNA strand (split into I, II, III motifs) |

| HNH Domain | 775-908 | Cleaves target DNA strand complementary to gRNA | |

| PAM-Interacting (PI) | 1099-1368 | Recognizes protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence |

The REC lobe is predominantly responsible for binding both the sgRNA and the target DNA, while the NUC lobe contains the catalytic centers for DNA cleavage and the domain responsible for recognizing the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) [7]. The HNH domain, which cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the gRNA, exhibits significant conformational flexibility, which may be crucial for its catalytic activity [7].

Figure 1: Structural organization of the Cas9 protein and its core components. The protein comprises two primary lobes that form a groove for nucleic acid binding.

Composition and Structure of the Guide RNA

The guide RNA exists in multiple formats, with the single guide RNA (sgRNA) being the most common for research applications. The sgRNA is a chimeric RNA molecule created by fusing two natural RNA components: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) [9] [10].

Table 2: Components of the Single Guide RNA (sgRNA)

| Component | Length | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| crRNA segment | 17-23 nt | Target recognition via complementarity | 5' end; defines targeting specificity |

| Linker loop | Variable | Connects crRNA and tracrRNA | Synthetic tetra-loop in engineered systems |

| tracrRNA scaffold | ~65 nt | Cas9 protein binding | Forms core duplex RNA structure |

The crRNA portion contains the customizable 17-20 nucleotide "spacer" sequence that determines DNA targeting specificity through complementarity, while the tracrRNA portion serves as a binding scaffold for the Cas9 protein [9] [8]. This synthetic fusion simplifies the experimental system from three components (Cas9, crRNA, tracrRNA) to two components (Cas9, sgRNA), significantly enhancing its utility for genetic engineering [10].

Functional Mechanism of DNA Targeting and Cleavage

Target Recognition and Activation Cycle

The Cas9-sgRNA complex employs a sophisticated multi-step mechanism to locate and cleave its DNA target. The process begins with PAM recognition, followed by DNA melting, seed sequence annealing, and culminating in double-strand break formation.

Figure 2: Functional workflow of Cas9-sgRNA complex in DNA target recognition and cleavage.

The PAM sequence, typically 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9, serves as an essential binding signal that must be present immediately adjacent to the target sequence [8]. This requirement prevents the CRISPR system from targeting the bacterial genome's own CRISPR arrays. Once the PAM is recognized, the Cas9 protein unwinds the DNA duplex, allowing the seed region (positions 8-10 at the 3' end of the gRNA targeting sequence) to initiate pairing with the target DNA [8]. If sufficient complementarity exists, complete heteroduplex formation occurs, triggering conformational changes that activate the nuclease domains [7].

DNA Cleavage Mechanism

Upon successful target recognition, the Cas9 enzyme introduces a double-strand break (DSB) in the target DNA through the coordinated activity of its two nuclease domains:

- The RuvC domain cleaves the non-complementary DNA strand

- The HNH domain cleaves the complementary DNA strand that is base-paired with the gRNA [7]

This cleavage occurs approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence, resulting in a blunt-ended double-strand break [8]. The cell then repairs this break through either the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, often resulting in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, or the precise homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway when a repair template is provided [8].

Design Principles for Optimal gRNA Performance

Sequence-Based Design Considerations

Effective gRNA design is critical for successful genome editing experiments. Key sequence characteristics significantly impact both on-target efficiency and off-target specificity.

Table 3: Key Parameters for Effective gRNA Design

| Parameter | Optimal Range/Value | Impact on Activity | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC Content | 40-80% (ideal: 40-60%) | High GC increases stability but may reduce activity | Overly stable gRNA:DNA duplexes impair cleavage [10] |

| Seed Region GC | Moderate (avoid extremes) | Critical for target recognition | Mismatches in seed region (positions 8-10) abolish cleavage [8] |

| Position 20 | Guanosine (G) preferred | Enhanced cleavage efficiency | Adjacent to PAM; G improves initiation [11] |

| Repetitive Bases | Avoid GGGG, UUU stretches | Prevents synthesis issues and structural problems | G-quadruplex formation; UUU acts as Pol III terminator [10] |

Structural Considerations and gRNA Accessibility

Beyond sequence composition, the secondary structure of the gRNA itself plays a crucial role in determining functionality. Structural accessibility, particularly at the 3' end of the guide sequence (positions 18-20), is a hallmark of highly active sgRNAs [10]. Nucleotides in this seed region must remain unpaired and accessible for efficient target recognition. Inactive gRNAs often form internal hairpin structures where the 3' end of the guide sequence pairs with nucleotides in the tracrRNA scaffold (positions 51-53), creating an extended stem-loop that prevents target DNA binding [11] [10].

Thermodynamic analyses reveal that non-functional guide sequences have significantly higher self-folding free energy (ΔG = -3.1) compared to functional ones (ΔG = -1.9), indicating greater propensity to form internal secondary structures that impair function [10]. Similarly, the stability of the gRNA:DNA heteroduplex affects activity, with non-functional guides forming more stable duplexes (ΔG = -17.2) than functional ones (ΔG = -15.7) [10].

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR-Cas9 Workflows

Protocol 1: Mammalian Cell Genome Editing Using Plasmid-Based Delivery

This standard protocol enables robust gene knockout in human cell lines through NHEJ-mediated repair.

Materials Required:

- Cas9 expression plasmid (e.g., pX458, Addgene #48138)

- sgRNA expression vector or oligos for cloning

- Target cell line (e.g., HEK293T, HeLa)

- Transfection reagent (e.g., Lipofectamine 3000)

- Antibiotics for selection (e.g., puromycin)

- Lysis buffer for genomic DNA extraction

- PCR reagents for amplification of target locus

- Gel electrophoresis equipment or T7 Endonuclease I for mutation detection

- Sequencing primers for validation

Methodology:

- sgRNA Design: Select 20-nucleotide target sequence adjacent to 5'-NGG-3' PAM using design tools (CHOPCHOP, Synthego). Verify specificity via BLAST against relevant genome.

- Cloning: Anneal and phosphorylate oligos encoding sgRNA target, ligate into BbsI-digested Cas9 plasmid. Transform competent E. coli, screen colonies by PCR/sequencing.

- Cell Transfection: Plate 2×10^5 cells/well in 6-well plate 24h before transfection. Transfect with 2μg plasmid DNA using appropriate transfection reagent per manufacturer's protocol.

- Selection/Enrichment: Apply puromycin (1-5μg/mL) 48h post-transfection for 72h (for pX458) or sort GFP-positive cells by FACS.

- Analysis: Harvest cells 5-7 days post-transfection. Extract genomic DNA, amplify target locus by PCR (300-500bp product). Detect indels via T7E1 assay (5-10% agarose gel) or Sanger sequencing with TIDE decomposition analysis.

- Validation: Clone PCR products into TA vector, transform bacteria, sequence 20+ colonies to determine precise editing efficiency and mutation spectrum.

Troubleshooting:

- Low efficiency: Optimize sgRNA design, verify Cas9/sgRNA expression, test alternative transfection methods

- High toxicity: Reduce DNA amount, use inducible Cas9 system, employ Cas9 nickase pairs

- Off-target effects: Use truncated sgRNAs, high-fidelity Cas9 variants, validate potential off-target sites

Protocol 2: In Vitro Cleavage Assay for gRNA Validation

This biochemical approach directly tests sgRNA activity before cell-based experiments, saving time and resources.

Materials Required:

- Purified Cas9 protein (commercial or recombinant)

- In vitro transcribed or synthetic sgRNA

- Target DNA substrate (PCR-amplified genomic region or plasmid)

- Nuclease-free buffer components

- Agarose gel electrophoresis system

- DNA staining dye (e.g., SYBR Safe)

Methodology:

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation: Incubate 100nM Cas9 with 120nM sgRNA in reaction buffer (20mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150mM KCl, 10mM MgCl₂, 5% glycerol) for 10min at 37°C.

- Cleavage Reaction: Add 10nM target DNA substrate to RNP complex, incubate at 37°C for 1h in thermal cycler.

- Reaction Termination: Add Proteinase K (0.5mg/mL) with 0.1% SDS, incubate 15min at 56°C.

- Analysis: Resolve cleavage products on 2% agarose gel, stain with DNA dye, visualize under UV light. Quantify band intensity using ImageJ software.

- Kinetic Analysis (Optional): Perform time-course experiments (0-120min) with aliquots taken at intervals to determine cleavage rate.

Expected Results: Successful cleavage produces two DNA fragments from a single substrate. Calculate cleavage efficiency as percentage of cleaved DNA relative to total DNA. Compare EC₅₀ values (Cas9 concentration for half-maximal cleavage) between different sgRNAs [11].

Advanced Engineering and Specificity Enhancements

Engineered Cas9 Variants for Improved Specificity

Wild-type SpCas9 can tolerate mismatches between the gRNA and target DNA, leading to potential off-target effects. Several engineered high-fidelity Cas9 variants have been developed to address this limitation.

Table 4: Engineered Cas9 Variants with Enhanced Specificity

| Variant | Mutations | Mechanism of Action | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| eSpCas9(1.1) | K848A, K1003A, R1060A | Weakenes non-target strand interactions | Reduced off-target cleavage while maintaining on-target activity |

| SpCas9-HF1 | N497A, R661A, Q695A, Q926A | Disrupts interactions with DNA phosphate backbone | High-fidelity editing with minimal off-target effects |

| HypaCas9 | N692A, M694A, Q695A, H698A | Enhances proofreading and mismatch discrimination | Improved specificity while maintaining robust on-target editing |

| evoCas9 | M495V, Y515N, K526E, R661Q | Decreased off-target effects through directed evolution | High-fidelity applications in therapeutic development |

| Sniper-Cas9 | F539S, M763I, K890N | Reduced off-target activity with truncated gRNAs | Compatible with 17-18nt gRNAs for enhanced specificity |

These high-fidelity variants typically achieve reduced off-target activity by introducing mutations that weaken Cas9's interactions with the DNA backbone or enhance its ability to discriminate against mismatched targets [8]. While some variants exhibit reduced on-target activity, they provide significantly improved specificity profiles for applications where off-target editing is a major concern.

Alternative Cas Enzymes and Expanding Targeting Range

Beyond SpCas9, numerous alternative Cas enzymes with distinct properties have been characterized and employed for specialized applications:

- SaCas9: From Staphylococcus aureus, recognizes 5'-NNGRR(N)-3' PAM, smaller size for AAV delivery

- Cas12a (Cpf1): Creates staggered DNA cuts, requires only crRNA (no tracrRNA), processes its own CRISPR array

- Cas13: RNA-targeting enzyme for transcriptome engineering and diagnostics

- Engineered PAM-flexible variants: xCas9 and SpCas9-NG recognize NG PAMs, SpRY recognizes NRN/NYN PAMs [8]

These alternatives expand the targeting range of CRISPR systems and enable new applications beyond DNA editing, including RNA targeting, base editing, and epigenetic modification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Systems | pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro (PX459), pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458) | Provides Cas9 and sgRNA expression with selection marker | Plasmid format enables stable integration and long-term expression |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1 plasmids | Reduces off-target effects while maintaining on-target activity | Critical for therapeutic applications and sensitive genetic screens |

| sgRNA Synthesis | Synthetic sgRNA, IVT sgRNA kits, sgRNA expression vectors | Delivers targeting component | Synthetic sgRNA offers highest purity and consistency [9] |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lipofectamine 3000, Lentiviral particles, Electroporation systems | Introduces CRISPR components into cells | Choice depends on cell type: chemical (easy), viral (efficient), electroporation (challenging cells) |

| Detection & Validation | T7 Endonuclease I, Surveyor Mutation Detection Kit, Tracking Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) | Identifies successful genome editing | T7E1 for quick assessment; sequencing for precise characterization |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CHOPCHOP, CRISPRscan, Cas-OFFinder, Synthego Design Tool | Designs sgRNAs and predicts off-target sites | Web-based tools streamline design process and improve success rates [12] |

The Cas protein and guide RNA represent one of the most transformative duos in modern molecular biology. Their modular nature - with Cas providing the catalytic engine and gRNA conferring targeting specificity - has democratized genome engineering across biological disciplines. Understanding the structural basis of their interaction, the mechanistic details of DNA recognition and cleavage, and the principles governing gRNA design is fundamental to harnessing their full potential. As the field advances with engineered variants offering enhanced specificity and novel Cas enzymes expanding the targeting landscape, this core technology continues to evolve, offering increasingly sophisticated tools for basic research and therapeutic development. Proper implementation requires careful attention to gRNA design, appropriate controls for specificity validation, and selection of optimal Cas variants for each application.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic research and therapeutic development by providing unprecedented control over genomic manipulation. At the core of this technology lies a fundamental process: the creation of programmed DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). These breaks serve as the initiating event that enables virtually all subsequent genome engineering outcomes, from simple gene knockouts to precise nucleotide substitutions. The molecular scissors analogy aptly describes the Cas9 endonuclease, which precisely targets and cleaves DNA at user-defined locations [13] [8]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a thorough understanding of DSB creation mechanisms is essential for designing effective experiments and anticipating potential cellular responses, including unintended recombination events and repair pathway choices that impact experimental outcomes and therapeutic safety [13].

This technical guide examines the molecular mechanisms underlying CRISPR-induced DSBs, the resulting cellular repair pathways, and practical experimental considerations for controlling editing outcomes. We present this information within the context of basic CRISPR principles, providing a foundation for researchers to design more precise and efficient genome editing experiments.

Molecular Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 Induced DNA Cleavage

The Core CRISPR-Cas9 Complex

The CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two fundamental components: a Cas9 endonuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) [8]. The gRNA is a short synthetic RNA composed of a scaffold sequence necessary for Cas-binding and a user-defined ∼20-nucleotide spacer that defines the genomic target to be modified [8]. The ability to change the genomic target of the Cas enzyme by simply changing the target sequence present in the gRNA makes CRISPR highly scalable compared to previous genome engineering technologies [8].

The Cas9 enzyme originates from microbial adaptive immune systems and functions as a programmable DNA endonuclease. The most commonly used variant is SpCas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes [8]. Cas9 undergoes significant conformational changes during its operation: gRNA binding induces a shift into an active, DNA-binding configuration, with the spacer region of the gRNA left free to interact with target DNA [8].

Target Recognition and Cleavage Dynamics

Cas9 recognizes target DNA sequences through a two-step verification process. First, the enzyme identifies a specific protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site [8]. For SpCas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" represents any nucleotide [8]. This PAM requirement is a critical consideration in gRNA design, as an NGG sequence must be positioned correctly near the target site.

Once Cas9 binds a putative DNA target, the seed sequence (8–10 bases at the 3' end of the gRNA targeting sequence) begins to anneal to the target DNA [8]. If the seed and target DNA sequences match, the gRNA continues to anneal to the target DNA in a 3' to 5' direction [8]. The location of any potential mismatches significantly impacts cleavage efficiency—mismatches between the target sequence in the 3' seed sequence inhibit target cleavage, while mismatches toward the 5' end distal to the PAM often permit target cleavage [8].

Upon successful target binding, Cas9 undergoes a second conformational change where its nuclease domains, RuvC and HNH, cleave opposite strands of the target DNA [8]. This results in a double-strand break within the target DNA, located ∼3–4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [8]. The HNH domain cleaves the complementary strand, while the RuvC domain cleaves the non-complementary strand, generating a blunt-ended DSB [8].

Figure 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Target Recognition and Cleavage Mechanism. The process initiates with PAM recognition, followed by seed sequence annealing, full gRNA hybridization, Cas9 conformational change, and culminating in RuvC and HNH nuclease domain activation to create a blunt-ended double-strand break.

Comparison of Cas Nucleases and Their Cleavage Properties

While Cas9 remains the most widely used enzyme, several other Cas nucleases offer distinct properties, particularly regarding their PAM requirements and cleavage patterns. Cas12a (Cpf1), for example, recognizes T-rich PAM sequences located at the 5' end of the target and creates staggered ends with 5' overhangs, unlike the blunt ends produced by Cas9 [14]. Additionally, Cas12a requires only a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) for activity, while Cas9 requires both crRNA and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Cas Nuclease Properties for DSB Creation

| Property | Cas9 | Cas12a (Cpf1) | Cas9 Nickase (D10A) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAM Sequence | 3'-NGG-5' | 5'-TTN-3' | 3'-NGG-5' |

| Cleavage Pattern | Blunt ends | Staggered ends (5' overhangs) | Single-strand nick |

| gRNA Requirement | crRNA + tracrRNA | crRNA only | crRNA + tracrRNA |

| Active Nuclease Domains | RuvC & HNH | Single RuvC-like | HNH only (RuvC inactivated) |

| DSB Formation | Single enzyme | Single enzyme | Requires two nickases in close proximity |

Cellular Repair Pathways for Double-Strand Breaks

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

The efficient but error-prone non-homologous end joining pathway represents the primary repair mechanism for DSBs in most mammalian cells [8]. This pathway directly ligates the broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template [8]. While efficient in repairing DSBs, NHEJ frequently introduces small nucleotide insertions or deletions (indels) at the DSB site [8]. A population of cells expressing Cas9 and a gRNA will therefore result in a diverse array of mutations [8].

In most CRISPR applications, NHEJ gives rise to small indels in the target DNA that result in amino acid deletions, insertions, or frameshift mutations leading to premature stop codons within the open reading frame (ORF) of the targeted gene [8]. The ideal result is a loss-of-function mutation within the targeted gene, making NHEJ the preferred pathway for gene knockout experiments [8].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

The less efficient but high-fidelity homology-directed repair pathway relies on copying DNA from a matching template to accurately repair or fill in the missing sequence [8]. HDR is more commonly used for precision edits where specific nucleotide changes are required [8]. This pathway is active primarily during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle when sister chromatids are available as templates [13].

For refined and precise genome editing purposes, HDR is harnessed to copy a specific DNA template (single-stranded or double-stranded) into the target site [13]. The HDR pathway requires a donor template with homologous sequences flanking the target site, which serves as a repair template [8]. While HDR offers greater precision, its lower efficiency compared to NHEJ presents a significant challenge for researchers attempting to introduce specific edits.

DNA Resection: The Critical Decision Point

DNA resection represents a universal process in genome maintenance where one strand of DNA is degraded, leaving the other strand intact [15]. This sometimes highly processive degradation is critical for many forms of DNA damage repair, replication-coupled repair, and meiotic recombination [15]. The resection process must be tightly regulated to prevent genome instability and promote faithful and accurate repair [15].

Resection at DSBs is initiated by the combined action of the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) complex with its cofactor CtIP and represents one of the first control steps directing repair toward HDR [15]. Following short-range DNA resection, the MRN complex recruits a large molecular machine called the resectosome, a complex comprising a helicase (BLM or WRN), a nuclease (EXO1 or DNA2), and the ssDNA-binding protein replication protein A (RPA) [15]. Whereas short-range DNA resection ranges from tens to hundreds of nucleotides, long-range DNA resection can resect up to 3.5 kb from the DNA break in humans [15].

Figure 2: DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways. Following DSB creation, cells initiate repair through competing pathways. Limited resection directs repair toward error-prone NHEJ, while extensive resection enables high-fidelity HDR using the resectosome complex.

Advanced CRISPR Systems for Controlled DSB Creation

Engineered Cas Variants for Enhanced Specificity

Wild-type Cas9 produces DSBs at both intended and unintended (off-target) sites, posing significant challenges for therapeutic applications. To address this limitation, researchers have developed several engineered Cas9 variants with enhanced specificity:

- High-Fidelity Cas9 (hfCas9): eSpCas9(1.1) weakens interactions between the HNH/RuvC groove and the non-target DNA strand; SpCas9-HF1 disrupts Cas9's interactions with the DNA phosphate backbone; HypaCas9 increases Cas9 proofreading and discrimination [8].

- PAM-Flexible Cas9: xCas9 and SpCas9-NG recognize NG PAMs; SpG recognizes NGN PAMs; SpRY recognizes NRN and NYN PAMs, greatly expanding targeting range [8].

- Cas9 Nickase (Cas9n): A D10A mutant of SpCas9 with one active nuclease domain that generates single-strand breaks rather than DSBs [8]. Using paired nickases (dual nicking) increases specificity as two off-target nicks are unlikely to occur close enough to generate a DSB [8].

DSB-Independent CRISPR Systems

Recent advances have developed CRISPR systems that modify DNA without creating DSBs, addressing safety concerns associated with DSB repair:

- Base Editing: Utilizes a catalytically impaired Cas protein (dCas9 or nickase) fused to a DNA deaminase enzyme to directly convert one base pair to another without DSBs [16]. Cytidine Base Editors (CBEs) convert C•G to T•A, while Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) convert A•T to G•C [16].

- Prime Editing: Employs a Cas9 nickase fused to reverse transcriptase and a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) to directly write new genetic information into a target DNA site without DSBs [16]. This system can achieve all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, plus small insertions and deletions [16].

- CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi): Uses catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) to bind target DNA without cleavage, blocking transcription and reversibly repressing gene expression [17] [16]. When fused to transcriptional repressor domains like KRAB, CRISPRi can achieve potent gene silencing [17].

Table 2: Comparison of CRISPR Editing Platforms and Their DNA Modification Approaches

| Editing Platform | DSB Formation | Primary Repair Pathway | Editing Outcomes | Therapeutic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Nuclease | Yes | NHEJ/HDR | Indels, precise edits with donor | Gene knockouts, gene correction |

| Base Editing | No | DNA mismatch repair | Point mutations | Correcting point mutations causing disease |

| Prime Editing | No | DNA repair synthesis | All 12 base changes, small indels | Precise editing without donor templates |

| CRISPRi/a | No | N/A | Gene expression modulation | Gene regulation without DNA sequence change |

Experimental Considerations and Methodologies

Designing and Validating CRISPR Experiments

Successful CRISPR editing requires careful experimental design and validation. When designing gRNAs, researchers should select target sequences with perfect homology to the target DNA and minimal homology elsewhere in the genome to reduce off-target effects [8]. Various online tools are available to help select optimized gRNAs for specific applications [8].

For HDR-based editing, researchers must design donor templates with sufficient homology arms flanking the desired edit. Studies suggest that asymmetric homology arms with longer 5' arms may improve HDR efficiency in some systems. Additionally, timing Cas9 expression with cell cycle phases when HDR is active (S/G2) can improve precise editing efficiency.

Analyzing Editing Outcomes

Validating CRISPR editing is a critical step in any genome engineering experiment. Several methods are available to assess CRISPR editing efficiency:

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): The gold standard for analyzing CRISPR editing outcomes, providing comprehensive view of indels generated with high sensitivity [18]. Best suited for large-scale studies with bioinformatics support.

- Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE): Uses Sanger sequencing data to determine relative abundance and levels of indels [18]. Highly comparable to NGS (R² = 0.96) but more accessible for smaller labs.

- Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE): An older decomposition method using Sanger sequencing data to estimate relative abundance of insertions or deletions [18]. Limited primarily to detecting +1 insertions.

- T7 Endonuclease 1 (T7E1) Assay: A non-sequencing based method that detects mismatched DNA heteroduplexes [18]. Least expensive but provides no sequence-level information.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for CRISPR DSB Research

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Vector | Expresses Cas9 endonuclease in target cells | Choose between wild-type, nickase, or dead Cas9 depending on application |

| Guide RNA Cloning Vector | Expresses sequence-specific gRNA | Enables multiplexing with multiple gRNAs for complex edits |

| Donor Template | Provides homology for HDR repair | Single-stranded or double-stranded DNA with homology arms |

| Delivery Method | Introduces CRISPR components into cells | Viral (lentiviral, AAV), electroporation, or transfection methods |

| Validation Primers | Amplify target locus for analysis | Design to flank cut site by 100-300bp for optimal resolution |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Comprehensive analysis of editing outcomes | Provides deepest analysis but requires bioinformatics expertise |

Unintended Consequences and Safety Considerations

Chromosomal Rearrangements and Recombination Events

CRISPR-induced DSBs may trigger unintended genetic consequences beyond small indels. Studies in Drosophila demonstrate that Cas9-mediated editing events frequently result in germline-transmitted exchange of chromosome arms—often without indels [13]. These recombination events occurred in up to 39% of detected CRISPR events, even on chromosomes that normally exhibit no native recombination activity [13].

Such findings highlight an unforeseen risk of using CRISPR-Cas9 for therapeutic intervention, as large-scale chromosomal rearrangements could have significant pathological consequences [13]. The ability of CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce several concurrent DSBs at defined positions has been leveraged to engineer tumor-associated chromosomal translocations resembling those observed in cancers [13].

Mitigating Off-Target Effects

Several strategies have been developed to minimize off-target editing:

- High-Fidelity Cas Variants: eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, and HypaCas9 exhibit reduced off-target activity while maintaining robust on-target editing [8].

- Dual Nickase Approach: Using two Cas9 nickases with offset gRNAs requires both gRNAs to bind in close proximity to generate a DSB, dramatically increasing specificity [8].

- Computational gRNA Design: Careful gRNA selection to avoid sequences with high similarity to other genomic regions reduces off-target potential [8].

- Truncated gRNAs: Using shorter gRNAs (17-18 nt instead of 20 nt) can increase specificity, though with potential reduction in on-target efficiency [8].

- RIGS (Reference-based In silico Genome Screening): In silico methods to predict and avoid gRNAs with potential off-target sites [19].

The creation of programmed double-strand breaks represents the foundational mechanism underlying CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Understanding the molecular details of DSB formation, cellular repair pathways, and potential unintended consequences enables researchers to design safer and more effective experiments. As CRISPR technologies evolve toward DSB-free editing systems like base editing and prime editing, the fundamental principles of target recognition and DNA modification remain essential knowledge for researchers and therapeutic developers. The continued refinement of CRISPR systems promises to enhance both the precision and safety of genome engineering for basic research and clinical applications.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic research by providing scientists with unprecedented precision in genome editing. However, the CRISPR-Cas9 enzyme itself functions merely as a pair of "molecular scissors" that creates a specific double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA [20]. The actual genetic modification occurs through the cell's endogenous DNA Damage Repair (DDR) pathways, which are activated to join the two cut ends [20] [21]. These pathways are essential for maintaining genomic integrity across all organisms and represent a collection of intracellular mechanisms that sense DNA damage, alert the cell to its presence, and prompt repair [20]. For researchers aiming to leverage CRISPR technology, understanding how to harness two key competing repair pathways—Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)—is fundamental to achieving specific editing outcomes, whether for gene knockouts, precise point mutations, or gene knockins [20] [21].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of NHEJ and HDR Pathways

| Feature | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) |

|---|---|---|

| Template Requirement | No template required; uses broken ends [20] | Requires homologous donor template (e.g., sister chromatid, ssODN, plasmid) [20] [22] |

| Primary Mechanism | Direct ligation of DNA ends [23] | Uses homologous sequence as a template for accurate repair [22] |

| Fidelity | Error-prone; often results in small insertions or deletions (INDELs) [20] [21] | High-fidelity and precise [22] |

| Cell Cycle Phase | Active throughout all cell cycle phases [23] | Primarily active in S and G2 phases [20] [24] |

| Primary Application in CRISPR | Gene knockouts (disruption of gene function) [20] [21] | Gene knockins, precise point mutations, inserting fluorescent tags [20] [21] [23] |

| Typical Efficiency | High efficiency (fast and predominant pathway) [20] [24] | Low to moderate efficiency (requires competing with NHEJ) [23] [24] |

DNA Repair Pathway Mechanisms

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): The Quick Fix

NHEJ is a faster, more efficient repair pathway that operates by quickly rejoining the broken DNA ends without the need for a homologous template [20]. This speed comes at the cost of precision, as the process often leads to small insertions or deletions (INDELs) at the repair site [20] [21]. The term "non-homologous" refers to the fact that the two broken ends are indiscriminately ligated back together with minimal reference to the original DNA sequence [20]. The mechanism initiates with the Ku heterodimer (Ku70/Ku80) recognizing and binding to the DSB ends [23]. This Ku-DNA complex then recruits other core NHEJ factors, including the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) and the endonuclease Artemis, which may process the DNA ends [23]. Finally, the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex catalyzes the ligation of the DNA ends, often resulting in the characteristic INDEL mutations [23]. While these errors are undesirable in many contexts, they are ideal for gene knockout studies where the goal is to disrupt a gene's function by introducing frameshift mutations or premature stop codons [20].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): Precision Engineering

In contrast to NHEJ, HDR is a precise DNA repair mechanism that utilizes a homologous DNA sequence as a template to accurately repair the DSB [21] [22]. This template can be a sister chromatid, a donor plasmid, or a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) [21] [22]. The HDR process involves several key steps: first, the 5' ends at the break site are resected by nucleases to create 3' single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs [22]. This ssDNA then invades a homologous donor template—a step facilitated by recombinase enzymes—and uses the homologous regions as a blueprint for repair synthesis [22]. There are several sub-pathways of HDR, including Synthesis-Dependent Strand Annealing (SDSA) and Double-Strand Break Repair (DSBR), which ultimately resolve to complete the repair with high fidelity [22]. Because this pathway allows researchers to introduce specific sequences provided by an exogenous donor template, it is the foundation for precise genetic modifications such as gene knockins, point mutations, and the creation of transgenic models [20] [21] [23].

Diagram 1: Competitive DSB Repair Pathways. Following a CRISPR-induced break, cells can repair the damage via the faster, error-prone NHEJ pathway or the precise, template-dependent HDR pathway. The presence of an exogenous donor template is required for HDR.

Experimental Design for Pathway-Specific Editing

Strategic Selection for Genetic Outcomes

Choosing between NHEJ and HDR is dictated by the ultimate experimental goal. NHEJ is the preferred pathway when the objective is to disrupt a gene's function, creating a knockout [20] [21]. The INDELs introduced by NHEJ frequently cause frameshift mutations that lead to premature stop codons, effectively inactivating the gene [20]. This approach is invaluable for loss-of-function studies. Conversely, HDR is indispensable when precision is required [21]. It enables the introduction of specific nucleotide changes, the insertion of reporter genes like GFP for protein localization studies, or the creation of disease-associated point mutations in model organisms [20] [21] [23]. Achieving HDR requires co-delivering a donor template alongside the CRISPR-Cas9 components. The design of this template is critical: for small edits (1-50 bp), single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) with 30-50 base homology arms are standard [22]. For larger insertions, such as fluorescent proteins or selection cassettes, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) plasmids with longer homology arms (500-1000 bp) are typically used [22]. A key consideration in donor design is to disrupt the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) or the guide RNA binding site to prevent repeated cleavage of successfully edited alleles by Cas9 [22].

Methodologies to Modulate Repair Pathway Balance

A significant challenge in CRISPR editing is that NHEJ is the dominant and more efficient pathway in most eukaryotic cells, often outcompeting HDR [20] [24]. Consequently, researchers have developed strategies to coax cells toward HDR for more precise edits. One common approach is to inhibit the NHEJ pathway chemically or genetically. This can be achieved by using small molecule inhibitors targeting key NHEJ proteins, such as DNA-PKcs inhibitors, or through siRNA-mediated knockdown of factors like Ku70/80 [23]. An alternative strategy is to synchronize cells in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, where HDR is naturally more active [24]. Furthermore, the timing of Cas9 and donor template delivery can be optimized; some studies suggest delivering the donor template before the CRISPR machinery to increase its availability at the time of the DSB [23]. Finally, using Cas9 nickases—mutants that cut only one DNA strand—can also promote HDR. By using a pair of nickases to create a DSB with overhangs or by nicking near the intended edit site in the presence of a donor template, the frequency of HDR can be improved while reducing NHEJ-associated indels [23].

Table 2: Reagent Kits and Solutions for NHEJ and HDR Workflows

| Research Reagent | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Engineered nuclease that creates DSBs at genomic targets specified by a gRNA [25]. | Essential for initiating both NHEJ and HDR repair pathways [20]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | A synthetic RNA complex that directs Cas9 to a specific genomic locus [25]. | Determines the target site for CRISPR cutting; can be produced via in vitro transcription or chemical synthesis [25]. |

| ssODN Donor Template | A single-stranded DNA oligo containing the desired edit, flanked by homology arms [22]. | Used as a repair template for HDR to introduce small, precise edits (e.g., point mutations) [22]. |

| dsDNA Donor Plasmid | A double-stranded DNA plasmid containing the insertion sequence flanked by long homology arms [22]. | Used as a repair template for HDR to insert large sequences (e.g., fluorescent protein genes) [22]. |

| NHEJ Inhibitors (e.g., DNA-PKcs inhibitors) | Small molecules that chemically inhibit key proteins in the NHEJ pathway [23]. | Used to suppress the error-prone NHEJ pathway and increase the relative efficiency of HDR [23]. |

| Cas9 Nickase | A mutant Cas9 (e.g., D10A) that nicks only one DNA strand instead of creating a DSB [23]. | Using a pair of nickases can reduce off-target effects and promote HDR by creating staggered breaks [23]. |

Advanced Applications and Clinical Translation

The fundamental principles of harnessing NHEJ and HDR are driving the next generation of gene therapies and biomedical research. In clinical trials, both pathways are being exploited for therapeutic benefit. A landmark example is Casgevy, the first FDA-approved CRISPR-based medicine for sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia, which leverages CRISPR-mediated editing to disrupt (via NHEJ-like mechanisms) the BCL11A gene to reactivate fetal hemoglobin [26]. Meanwhile, HDR-based strategies are advancing toward the clinic for correcting specific pathogenic mutations. In 2025, a historic milestone was achieved with the development of a personalized in vivo CRISPR therapy for an infant with CPS1 deficiency, which was developed, approved, and delivered in just six months [26]. This case serves as a proof-of-concept for on-demand gene-editing therapies for rare genetic diseases. Furthermore, companies like Intellia Therapeutics are demonstrating the success of in vivo HDR-based therapies for diseases like hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR), where a single intravenous infusion of CRISPR-LNPs (lipid nanoparticles) leads to a deep and sustained reduction of the disease-related protein in the liver [26]. Beyond traditional CRISPR knockouts, newer modalities like base editing and prime editing are being developed to achieve precise changes without requiring a DSB, thereby bypassing the inherent competition between NHEJ and HDR and potentially increasing safety and efficiency [27] [28].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Pathway Selection. A decision tree guiding researchers from experimental goal to the appropriate repair pathway strategy and subsequent validation methods.

The conscious application of the NHEJ and HDR DNA repair pathways is a cornerstone of effective CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. NHEJ offers a straightforward and efficient method for gene disruption, while HDR provides the precision necessary for sophisticated genetic modeling and therapeutic correction. The ongoing development of strategies to bias the cellular repair machinery toward HDR, such as NHEJ inhibition and cell cycle manipulation, coupled with advances in delivery systems like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), is continuously enhancing the efficacy and expanding the applications of precision editing [26] [23]. As the field progresses, the integration of these fundamental principles with emerging technologies—including AI-powered design tools like CRISPR-GPT and next-generation base editors—promises to further accelerate the development of life-saving genetic therapies and deepen our understanding of biological systems [29] [28]. For researchers, a firm grasp of these cellular repair pathways remains indispensable for translating the cutting potential of CRISPR into meaningful and predictable genetic outcomes.

The discovery of the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas system has revolutionized genetic engineering, offering an unprecedented ability to manipulate nucleic acids with high precision. While the CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) from Streptococcus pyogenes has been the workhorse of genome editing, it represents only one facet of a diverse molecular ecosystem [30]. This review moves beyond the familiar Cas9 to explore the expanding universe of other Cas effectors—particularly Cas12 and Cas13—that have emerged as powerful tools with distinct functionalities. Framed within the broader principles of CRISPR research, this technical guide examines the unique mechanisms, applications, and experimental protocols for these alternative Cas proteins, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to leverage these systems for advanced genetic manipulation.

The classification of CRISPR-Cas systems into two classes based on effector complex architecture provides crucial context for understanding these molecular tools. Class 1 systems (types I, III, and IV) utilize multi-protein effector complexes, while Class 2 systems (types II, V, and VI) employ single effector proteins like Cas9, Cas12, and Cas13 [31] [32]. It is within Class 2 that we find the proteins of focus for this review: Cas12 (type V) for DNA targeting and Cas13 (type VI) for RNA targeting, each offering unique advantages that complement and in some cases surpass the capabilities of Cas9 [33].

Classification and Basic Mechanisms

CRISPR-Cas systems function as adaptive immune systems in prokaryotes, providing sequence-specific protection against foreign genetic elements. This adaptive immunity operates through three distinct stages: adaptation, where short DNA fragments from invaders (protospacers) are integrated into the host CRISPR array; expression, involving transcription of the CRISPR array into precursor CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA) and its processing into mature crRNAs; and interference, where crRNA-guided Cas effector complexes recognize and cleave complementary nucleic acids [31] [32]. This fundamental mechanism forms the foundation for all CRISPR-based technologies, with variations occurring in the specific components and pathways utilized by different Cas proteins.

Classification of Cas Proteins

Table 1: Classification and Key Characteristics of Major Class 2 CRISPR-Cas Effectors

| Effector Protein | CRISPR Type | Class | Target Nucleic Acid | Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) | Cleavage Pattern | Key Domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 | II | 2 | dsDNA | 5'-NGG-3' (SpCas9) | Blunt ends | RuvC, HNH |

| Cas12 | V | 2 | dsDNA/ssDNA | 5'-TTN-3' (FnCas12a) | Staggered ends | RuvC-only |

| Cas13 | VI | 2 | RNA | Protospacer Flanking Site (PFS) | RNA cleavage | HEPN |

The classification of Cas proteins reveals their evolutionary relationships and functional capabilities. Cas12 effectors (type V) differ significantly from Cas9 in both structure and mechanism. Unlike Cas9, which requires two nuclease domains (HNH and RuvC) for DNA cleavage, Cas12 proteins utilize a single RuvC domain to cleave both DNA strands, resulting in staggered ends rather than blunt cuts [34] [33]. This structural simplification presents potential advantages for certain applications. Furthermore, Cas12 recognizes distinct T-rich PAM sequences (e.g., 5'-TTN-3'), significantly expanding the targeting range beyond the G-rich PAMs required by SpCas9 [33].

Cas13 effectors represent a fundamentally different class of CRISPR tools as they exclusively target RNA rather than DNA [32]. Cas13 proteins contain two Higher Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes Nucleotide-binding (HEPN) domains responsible for RNA cleavage activity [33]. A unique feature of Cas13 is its collateral activity—upon recognition and cleavage of its target RNA, the protein becomes a promiscuous RNase that non-specifically degrades surrounding RNA molecules [32] [33]. This activity, while potentially a limitation for therapeutic applications, has been harnessed for highly sensitive diagnostic platforms.

Cas12 Family: DNA-Targeting Effectors

Mechanism of Action

Cas12 effectors operate through a distinct mechanism from Cas9. Upon recognition of a target DNA sequence adjacent to a compatible PAM, Cas12 undergoes conformational changes that position its single RuvC domain for sequential cleavage of both DNA strands [33]. The resulting staggered double-strand breaks typically feature 5-8 nucleotide overhangs, unlike the blunt ends produced by Cas9 [34]. This cleavage pattern can be advantageous for certain genome engineering applications where staggered ends potentially enhance homology-directed repair.

Another remarkable property of Cas12 is its trans-cleavage activity. After recognizing and cleaving its target DNA, Cas12 exhibits nonspecific single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) cleavage activity [33]. This activated state persists beyond the initial target recognition, enabling continuous degradation of surrounding ssDNA molecules. This collateral effect has been creatively harnessed for diagnostic applications, forming the basis for sensitive DNA detection platforms.

Subtypes and Applications

The Cas12 family includes several subtypes with distinct characteristics:

Cas12a (Cpf1): The most extensively characterized Cas12 variant, capable of processing its own crRNA arrays without requiring tracrRNA [33]. This feature enables simpler multiplexing approaches where multiple guide sequences can be expressed from a single transcript.

Cas12b: Significantly smaller than Cas9 and Cas12a, making it potentially more suitable for viral delivery [33]. Early versions required elevated temperatures for optimal activity, but engineered variants now function efficiently at mammalian physiological temperatures.

Cas12i and Cas12j: More recently discovered variants with compact sizes that show promise for therapeutic applications due to their high specificity and minimal off-target effects [33].

Table 2: Comparison of Cas12 Subtypes and Their Research Applications

| Cas12 Subtype | Size (aa) | PAM Requirement | crRNA Processing | Key Applications | Advantages for Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | ~1300 | 5'-TTN-3' | Autonomous | Genome editing, multiplexed targeting, DNA detection | Simplified multiplexing, staggered cuts for HDR |

| Cas12b | ~1100 | 5'-TTN-3' | Requires RNase | In vivo editing, viral delivery | Small size for AAV packaging, high specificity |

| Cas12i | ~1000 | 5'-TTN-3' | Autonomous | Therapeutic genome editing | High fidelity, minimal off-target effects |

| Cas12j (CasΦ) | ~700-800 | 5'-TTN-3' | Autonomous | Compact delivery, basic research | Ultra-small size, novel phylogenetic origin |

Cas13 Family: RNA-Targeting Effectors

Mechanism of Action

Cas13 represents a paradigm shift in CRISPR technology as the first well-characterized system to specifically target RNA molecules rather than DNA [32]. Cas13 effectors are guided by a single crRNA to complementary RNA sequences and cleave their targets using two HEPN domains that form the active RNase site [33]. Upon target recognition and cleavage, Cas13 undergoes a conformational change that activates its nonspecific collateral RNase activity, leading to degradation of nearby non-target RNA molecules [32] [33].

The Cas13 family includes multiple subtypes (VI-A through VI-D) with variations in crRNA handling and targeting requirements [32]. Unlike DNA-targeting Cas proteins that require specific PAM sequences, Cas13 recognition depends on protospacer flanking sites (PFS) with slight biases toward certain nucleotides but generally less restriction than DNA-targeting systems [32] [33].

Subtypes and Research Utilities

The Cas13 family has been classified into several subtypes with distinct properties:

Cas13a (C2c2): The first characterized RNA-targeting Cas protein, capable of processing pre-crRNA and exhibiting strong collateral activity in bacterial systems [33].

Cas13b: Often found in conjunction with accessory proteins that may modulate its activity, offering potential regulatory control mechanisms [32].

Cas13d: The most compact variant (~930 amino acids), making it suitable for viral delivery and enabling efficient RNA knockdown in eukaryotic cells without significant collateral effects [33].

The primary research applications of Cas13 leverage its programmable RNA-binding capability. These include: Transcript knockdown as an alternative to RNAi with potentially higher specificity; Live RNA imaging using catalytically inactive dCas13 fused to fluorescent proteins; RNA base editing through fusion with adenosine deaminases (e.g., ADAR2) for precise A-to-I conversions; and Nucleic acid detection utilizing the collateral activity for signal amplification in diagnostic platforms [34] [33].

Comparative Analysis and Selection Guide

Functional Comparison

Understanding the distinct properties of Cas9, Cas12, and Cas13 is crucial for selecting the appropriate tool for specific research goals. The following comparative analysis highlights key functional differences:

Table 3: Functional Comparison of Cas9, Cas12, and Cas13 Effectors

| Parameter | Cas9 | Cas12 | Cas13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Target | dsDNA | dsDNA/ssDNA | RNA |

| Cleavage Pattern | Blunt ends | Staggered ends | RNA fragments |

| Guide RNA | tracrRNA + crRNA | crRNA only | crRNA only |

| crRNA Processing | Requires RNase III | Autonomous | Autonomous |

| Collateral Activity | No | ssDNA cleavage after activation | RNA cleavage after activation |

| PAM/PFS Requirement | 5'-NGG-3' (SpCas9) | 5'-TTN-3' (Cas12a) | Minimal, preference for 3' nucleotide |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Moderate (with engineering) | High (natural crRNA array) | High (natural crRNA array) |

| Therapeutic Applications | Ex vivo cell therapy, gene disruption | Gene editing, DNA detection | RNA knockdown, RNA editing, diagnostics |

Selection Guidelines for Research Applications

Choosing the appropriate Cas protein depends on the specific research objectives:

For permanent DNA modification: Cas9 remains the standard for many applications, while Cas12 offers advantages for multiplexed editing or when targeting T-rich genomic regions.

For transient transcriptional modulation: Cas13 provides a powerful platform for knocking down RNA without altering the genome, ideal for therapeutic applications where temporary effects are desirable.

For diagnostic applications: Both Cas12 and Cas13 excel in nucleic acid detection due to their collateral activities, with Cas12 used for DNA targets and Cas13 for RNA targets.

For viral delivery: Compact variants like Cas12j and Cas13d offer advantages due to their smaller size, enabling packaging into adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors with larger cargo capacities.

Experimental Design and Protocols

General Workflow for Cas12 Genome Editing

The experimental pipeline for Cas12-mediated genome editing shares similarities with Cas9 protocols but requires consideration of its unique properties:

Target Selection: Identify target sites with appropriate PAM sequences (typically 5'-TTN-3' for Cas12a). Verify specificity using in silico prediction tools to minimize off-target effects.

Guide RNA Design: Design crRNAs with ~20-24 nucleotide spacer sequences. For multiplexed editing, design crRNA arrays with direct repeats separating individual spacer sequences.

Delivery System Preparation:

- For plasmid-based delivery: Clone crRNA expression cassettes into appropriate vectors. Cas12 expression can be driven by constitutive (e.g., EF1α) or inducible promoters.

- For ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery: In vitro transcribe crRNA and purify Cas12 protein. Complex at molar ratios of 1:2 to 1:4 (protein:RNA) for 10-30 minutes before delivery.

Delivery into Target Cells:

- For mammalian cells: Use electroporation for RNP delivery or lipid-based transfection for plasmid DNA.

- For primary cells: Optimized RNP delivery typically yields highest editing efficiency with minimal toxicity.

Validation and Analysis:

- Assess editing efficiency 48-72 hours post-delivery using T7E1 assay, TIDE analysis, or next-generation sequencing.

- Evaluate potential off-target effects at predicted sites using targeted sequencing.

Protocol for Cas13-Mediated RNA Knockdown

Cas13 enables programmable RNA knockdown without genomic alteration. The following protocol outlines key steps for implementing this technology:

Target Selection: Identify accessible regions within target transcripts using RNA accessibility prediction tools or empirical testing. Avoid highly structured regions if possible.

crRNA Design: Design crRNAs with spacer sequences complementary to the target RNA. Include 28-30 nucleotides for optimal activity with most Cas13 orthologs.

Expression System Selection:

- For transient expression: Use plasmid vectors with RNA polymerase III promoters (U6) for crRNA expression and polymerase II promoters for Cas13 expression.

- For stable expression: Integrate Cas13 expression cassette into safe-harbor loci (e.g., AAVS1) and deliver crRNAs via viral vectors.

Delivery Optimization:

- For in vitro applications: Transfect plasmid DNA or in vitro transcribed components using lipid-based reagents.

- For in vivo applications: Utilize AAV vectors (serotypes vary by tissue tropism) for delivery of compact Cas13 variants like Cas13d.

Efficiency Validation:

- Quantify knockdown efficiency 24-96 hours post-delivery using RT-qPCR, RNA-seq, or western blot (if protein reduction is measured).

- Monitor potential collateral effects by examining housekeeping gene expression levels.

Phenotypic Assessment:

- Evaluate functional consequences of knockdown using cell-based assays relevant to the target pathway.

- For therapeutic applications, assess rescue of disease-associated phenotypes.

Diagnostic Assay Development with Cas12 and Cas13

The collateral activities of Cas12 and Cas13 have been harnessed for highly sensitive diagnostic platforms. The general workflow for developing such assays includes:

Sample Preparation: Extract nucleic acids from biological samples. For RNA targets, include a reverse transcription step.

Target Amplification: Implement isothermal amplification (e.g., RPA, LAMP) to increase target abundance. This step enhances detection sensitivity to attomolar or zeptomolar levels.

Cas Detection Reaction:

- Program the Cas protein (Cas12 for DNA, Cas13 for RNA) with target-specific crRNAs.

- Include reporter molecules (e.g., fluorescently labeled ssDNA/RNA oligonucleotides) that will be cleaved upon Cas activation.

- Incubate at optimal temperature (typically 37°C) for 30-90 minutes.

Signal Detection:

- Use fluorimeters for quantitative measurements.

- Alternatively, employ lateral flow strips for visual readouts suitable for point-of-care applications.

Validation: Compare with established detection methods (e.g., PCR) to determine sensitivity and specificity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Cas12 and Cas13 Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Plasmids | Cas12a/pCAG, Cas13d/U6-gRNA | Protein and guide RNA expression | Choose promoters based on cell type (U6 for crRNA, CAG/EF1α for Cas) |

| Purified Proteins | Recombinant Cas12a, Cas13d | For RNP delivery | Higher specificity, reduced off-target effects compared to plasmid delivery |

| Synthetic crRNAs | Chemically synthesized spacers | Guide RNA for target recognition | Can include modified nucleotides for enhanced stability |

| Detection Reporters | FQ-reporters (ssDNA/RNA) | For collateral activity detection | Essential for diagnostic applications and activity validation |

| Amplification Reagents | RPA/LAMP kits | Pre-amplification for diagnostics | Enables high sensitivity in detection assays |

| Delivery Tools | Electroporation systems, Lipofectamine | Introducing components into cells | RNP delivery preferred for primary cells |

| Validation Kits | T7E1, TIDE, NGS libraries | Editing efficiency quantification | NGS provides most comprehensive analysis |

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

The unique properties of Cas12 and Cas13 proteins have enabled applications beyond traditional genome editing:

Therapeutic Development: Cas13 shows exceptional promise for treating RNA-based diseases. In a landmark 2025 case, researchers developed a personalized in vivo CRISPR therapy for an infant with CPS1 deficiency using LNP-delivered Cas13, demonstrating the potential for rapid development of treatments for rare genetic disorders [26]. Intellia Therapeutics has advanced Cas13-based therapies for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) and hereditary angioedema (HAE) into clinical trials, showing sustained reduction of disease-related proteins in patients [26].

Diagnostic Platforms: The collateral activities of Cas12 and Cas13 form the foundation of revolutionary diagnostic tools. The DNA Endonuclease-Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter (DETECTR) system utilizing Cas12a enables attomolar-level DNA detection, while the Specific High-sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter UnLOCKing (SHERLOCK) platform based on Cas13 achieves zeptomolar sensitivity for RNA targets [35] [33]. These systems have been deployed for detecting pathogens including SARS-CoV-2 with point-of-care applicability [35].

Advanced Research Tools: Engineered catalytically inactive versions of these proteins (dCas12, dCas13) serve as programmable DNA- and RNA-binding platforms for applications including base editing, epigenetic modification, live-cell imaging, and transcript tracking [34]. Fusion proteins combining dCas13 with adenosine deaminases (ADAR) enable precise RNA base editing without permanent genomic changes [34].

The future of CRISPR technology beyond Cas9 will likely see increased specialization of Cas proteins for particular applications, enhanced by engineering efforts to improve specificity, efficiency, and delivery. The integration of artificial intelligence tools like CRISPR-GPT is already accelerating experimental design and optimization, potentially reducing development timelines for new therapies [29]. As our understanding of these diverse molecular machines deepens, their impact on basic research and therapeutic development will continue to expand, offering new avenues for manipulating biological systems with unprecedented precision.

Visual Guide to Cas12 and Cas13 Mechanisms

From Bench to Bedside: CRISPR Workflows and Therapeutic Applications

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic research and therapeutic development by providing a precise and programmable method for genome editing. At the heart of this technology lies the guide RNA (gRNA), a short nucleic acid sequence that directs the Cas nuclease to specific genomic targets. The effectiveness of CRISPR experiments hinges on the design of highly functional gRNAs that maximize on-target efficiency while minimizing off-target effects. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles of gRNA design, key parameters for optimization, bioinformatics tools for selection, and experimental methodologies for validation. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, including the application of artificial intelligence in editor design, this review provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for developing effective gRNA strategies within the broader context of CRISPR gene editing research.

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) system functions as an adaptive immune mechanism in bacteria and archaea, but has been repurposed as a powerful genome-editing tool in molecular biology [36]. The CRISPR-Cas9 system fundamentally consists of the Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) that directs it to a specific DNA sequence [37]. The simplicity of this system, compared to previous gene-editing technologies like TALENs or ZFNs, has accelerated its adoption across research and therapeutic applications [36].

The gRNA is a synthetic fusion of two natural RNA components: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) containing the 20-nucleotide spacer sequence that determines targeting specificity through Watson-Crick base pairing, and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) which provides a structural scaffold for Cas9 binding [36]. When these two elements are combined into a single guide RNA (sgRNA), they form a functional complex that directs Cas9 to create double-strand breaks in target DNA [36]. This break occurs approximately 3 base pairs upstream of a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), a short DNA sequence adjacent to the target site that is essential for recognition by the Cas nuclease [37]. For the most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" represents any nucleotide [38].

The fundamental goal in gRNA design is to select a 20-nucleotide target sequence immediately upstream of a PAM site that is unique within the genome and possesses optimal characteristics for high editing efficiency and minimal off-target activity [37]. The design process must also consider the specific application (e.g., gene knockout, knock-in, activation, or inhibition) as optimal parameters differ based on experimental goals [39] [40]. As CRISPR technology continues to evolve, proper gRNA design remains the critical determinant of experimental success across basic research and therapeutic development.

Key Parameters for Effective gRNA Design

On-Target Efficiency

On-target efficiency refers to the predicted editing effectiveness of a gRNA at its intended target site. Various algorithms have been developed to predict gRNA on-target efficiency based on large-scale experimental data. The following table summarizes the major scoring methods and their applications: