Controlled Vocabulary Annotation for Scientific Data: Enhancing Discovery, Interoperability, and Reproducibility in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to controlled vocabulary annotation for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Controlled Vocabulary Annotation for Scientific Data: Enhancing Discovery, Interoperability, and Reproducibility in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to controlled vocabulary annotation for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental role of standardized terminologies in making scientific data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR). The content covers foundational principles, modern AI-enhanced implementation methodologies, strategies for overcoming common challenges, and comparative validation of approaches. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging standards, this resource empowers scientific teams to build robust data annotation strategies that accelerate discovery and enhance collaboration across the biomedical research landscape.

What Are Controlled Vocabularies and Why Are They Essential for Scientific Data?

FAQ: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

FAQ: What is a controlled vocabulary and why is it critical for research data? A controlled vocabulary is a standardized set of terms used to ensure consistent labeling and categorization of data. It is critical for research because it enables data to be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR). In scientific research, precise and consistent implementation is the cornerstone of reproducibility. Using inconsistent or ambiguous terms for data labels is a major source of error when attempting to replicate studies [1].

FAQ: What is the practical difference between a Business Glossary and a Data Dictionary? While both are part of a robust data governance framework, they serve different audiences and purposes, as detailed in the table below [2].

Table: Comparison of Business Glossary and Data Dictionary

| Feature | Business Glossary | Data Dictionary |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Audience | Business users across all functions | Technical users, data engineers, scientists |

| Content Focus | Business concepts and definitions, organizational consensus on terms | Technical documentation of data, including field names, types, and business rules |

| Purpose | Single authoritative source for business terms; aids onboarding and consensus-building | Detailed documentation for database and system design, data transformation |

Troubleshooting: Our research team is struggling with variable names. How can a controlled vocabulary help? A common issue is the use of ambiguous or inconsistent variable names across different datasets or team members. Implementing a controlled vocabulary for variable naming embeds metadata directly into the column name, providing immediate context [1].

Table: Example of a Controlled Vocabulary for Variable Naming [1]

| Variable Name | Description | Component Breakdown |

|---|---|---|

labs_eGFR_baseline_ind |

Indicator for whether a patient had an eGFR lab test during the baseline period. | labs (domain), eGFR (measure), baseline (timing), ind (data type: indicator) |

labs_eGFR_baseline_median_value |

The median value of the eGFR test during the baseline period. | Adds median_value (statistic and unit) |

Troubleshooting: We implemented a vocabulary, but queries are still difficult. What's wrong?

If your variable names lack a consistent structure, querying data subsets becomes complex. A well-defined vocabulary enables the use of regular expressions for efficient data querying, validation, and report generation. For example, to find all baseline lab variables, a simple pattern like .*_baseline_.* can be used [1].

FAQ: What are ontologies and how do they relate to simpler vocabularies? Ontologies are a more complex and powerful form of controlled vocabulary. They not only define a set of terms but also specify the rich logical relationships between those terms. This transforms human-readable data into machine-actionable formats, which is a key technique for enhancing data reusability and research reproducibility [3]. Simple word lists control terminology, while taxonomies add a hierarchical "is-a" structure (e.g., "a cat is a mammal"). Ontologies go further, defining various relationships like "part-of" or "located-in," enabling sophisticated computational reasoning.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Controlled Vocabulary

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for implementing a controlled vocabulary within a research project to improve data annotation consistency.

1. Definition and Scope

- Objective: To define a standardized naming schema for all variables in the [Project Name] dataset.

- Governance: Identify a lead data steward responsible for maintaining the vocabulary.

- Tools: The vocabulary will be documented in a shared [Excel Sheet/Google Sheet/Data Catalog Tool].

2. Vocabulary Schema Design

Design a structured format for all variable names. A recommended format is: [Domain]_[Measurement]_[Timing]_[Type].

- Domain: The broad category of the data (e.g.,

labs,vitals,demofor demographics). - Measurement: The specific metric (e.g.,

eGFR,systolic_bp,age). - Timing: The relevant time period (e.g.,

baseline,followup_1,screening). - Type: The data type or statistic (e.g.,

indfor indicator,mean_value,count,catfor category).

3. Application and Validation

- Application: Apply the new naming schema to all variables in the dataset. This can be done during data wrangling in R or Python.

- Programmatic Validation: Write scripts to validate data against the vocabulary's rules. For example, check that all

_valuevariables are numeric and non-negative [1].

4. Maintenance and Versioning

- Version Control: Track changes to the vocabulary schema using a system like Git.

- Change Management: Establish a process for proposing and reviewing new terms to ensure consistency is maintained as the project evolves.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Controlled Vocabulary and Data Annotation Work

| Item / Solution | Function |

|---|---|

| Data Catalog Tool | Acts as a bridge between business glossaries and data dictionaries; provides an organized inventory of data assets to help users locate datasets quickly [2]. |

| Ontology Management Software | Specialized tools for creating, editing, and managing complex ontologies, supporting the definition of logical relationships between terms. |

| Business Glossary Software | A repository for business terms and definitions, serving as a single authoritative source to build consensus within an organization [2]. |

| Semantic Annotation Tools | Software that automates the process of tagging data with terms from ontologies and controlled vocabularies, making data machine-actionable [3]. |

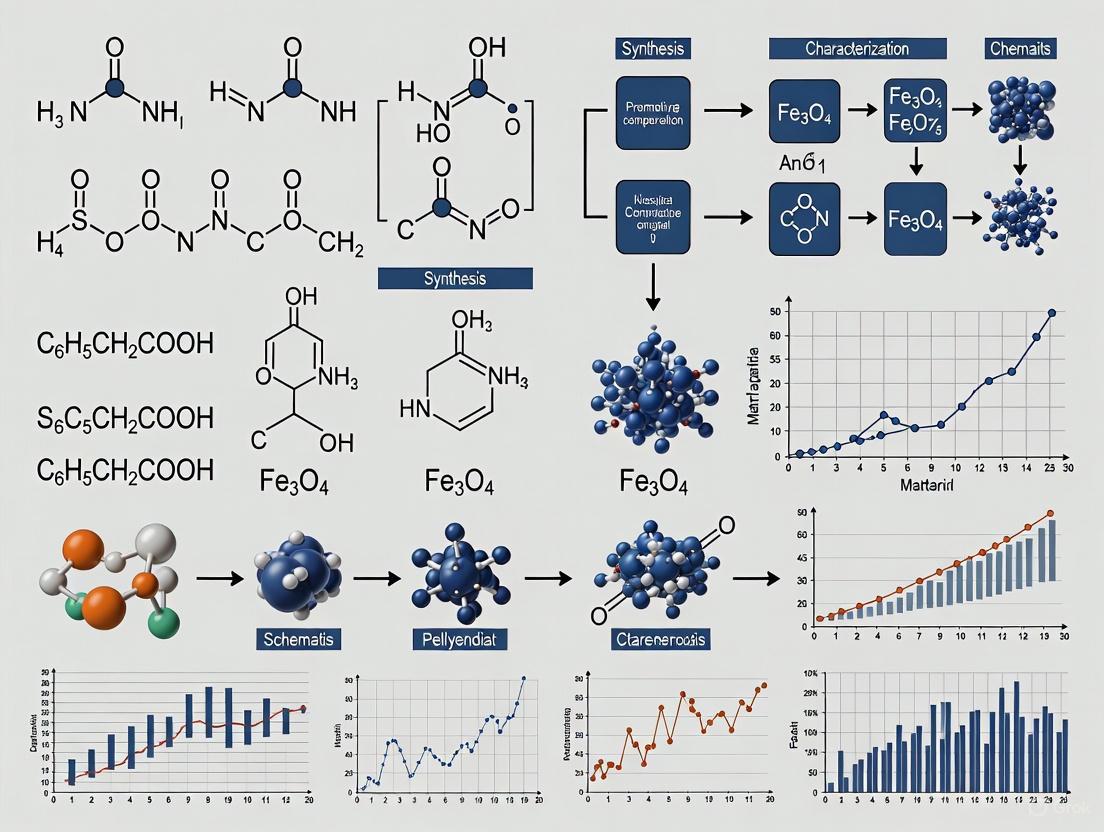

Workflow Visualization

Controlled Vocabulary Implementation Workflow

Controlled Vocabulary Evolution

Ambiguity in scientific terminology is a critical, often overlooked, problem that undermines data reproducibility, interoperability, and clarity in communication. Controlled vocabulary annotation directly addresses this by tagging scientific data with standardized, unambiguous terms, transforming human-readable information into a machine-actionable format [3]. This practice is foundational for robust data management and reliable research outcomes.

FAQs: Understanding Ambiguity and Controlled Vocabularies

What is a controlled vocabulary in scientific research?

A controlled vocabulary is a standardized set of terms and definitions used to consistently label and categorize data. It involves using a defined schema to label variables in a dataset systematically. This practice embeds metadata directly into variable names, providing immediate context and enhancing data clarity [1]. For example, a variable name like labs_eGFR_baseline_median_value immediately conveys the domain (labs), the specific test (eGFR), the time period (baseline), the statistical operation (median), and the data type (value) [1].

Why is terminology ambiguity a critical problem?

Ambiguity occurs when a single word or phrase can be interpreted in multiple ways, leading to miscommunication and errors in data interpretation.

- Impaired Reproducibility: The crux of reproducibility lies in the precise and consistent implementation of original work. Ambiguous variable names or methodology descriptions make it nearly impossible to replicate studies accurately [1].

- Barriers in Data Integration and Normalization: In clinical text analysis, mapping concept mentions to standardized vocabularies is fundamental. A single phrase can refer to multiple concepts; for example, the word "cold" could refer to a low temperature or the common cold. This ambiguity complicates efforts to use data for applications like clinical trial recruitment or pharmacovigilance [4].

- Clinical and Diagnostic Uncertainty: In fields like cancer surveillance, the use of "ambiguous terminology" in reports—such as "compatible with," "suggestive of," or "rule out"—creates significant challenges for data abstractors in determining reportable cancer cases and can affect the accuracy of critical metrics [5].

How does controlled vocabulary annotation solve this?

Controlled vocabulary annotation acts as a disambiguation layer. It forces consistency across a project, allowing both researchers and computer systems to understand precisely what each data point represents.

- Enhances Machine Actionability: Semantic annotation transforms human-readable data into machine-actionable formats, which is crucial for data reusability and research reproducibility [3].

- Streamlines Workflows: With consistently named variables, tasks like creating summary tables, modeling, and generating data dictionaries become more straightforward. Techniques like regular expressions can efficiently query subsets of data for validation and reporting [1].

- Improves Interoperability: By mapping diverse terms to a canonical concept within resources like the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS), controlled vocabularies allow different systems and research groups to share and compare data reliably [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Experimental Ambiguity in Your Data

This guide addresses the high-level process of diagnosing and fixing problems stemming from unclear or inconsistent terminology in your research data and protocols.

Problem Identified: Your experimental results are inconsistent or cannot be reproduced by your team. You suspect the cause is inconsistent labeling of variables, reagents, or processes.

List All Possible Explanations

- Variable Naming Inconsistency: The same concept is labeled differently across datasets or over time (e.g.,

patient_age,Age,age_at_baseline). - Protocol Documentation Gaps: Critical experimental details (e.g., reagent concentrations, incubation times) are described using vague or non-standardized language.

- Unclear Data Provenance: The origin or processing steps for a dataset are not clearly documented, leading to uncertainty about what the data represents.

- Variable Naming Inconsistency: The same concept is labeled differently across datasets or over time (e.g.,

Collect the Data

- Audit Your Data and Metadata: Review all variable names, data dictionaries, and lab notebook entries for the project. Identify terms with multiple synonyms or unclear definitions.

- Check Against Standards: Consult existing controlled vocabularies (e.g., SNOMED CT for clinical terms, RxNorm for drugs) to see if standardized terms are available for your field [4].

- Review Controls: Examine if the appropriate positive and negative controls were used and are clearly labeled in the dataset [6] [7].

Eliminate Explanations Based on your audit, you can eliminate explanations that are not the cause. For instance, if you find all protocol steps are meticulously documented with standardized terms, you can eliminate that as a source of error.

Check with Experimentation (Implement a Solution)

- Design and Implement a Mini-Vocabulary: For your project, define a short list of approved terms for common concepts. For example, decide to use

labs_eGFR_baseline_median_valueconsistently and retire other variants [1]. - Re-analyze Data: Process your dataset using the newly defined vocabulary. Does this resolve inconsistencies in data grouping or analysis?

- Design and Implement a Mini-Vocabulary: For your project, define a short list of approved terms for common concepts. For example, decide to use

Identify the Cause The cause of the ambiguity is the lack of a governing naming convention. The solution is to formally adopt and document a controlled vocabulary for all future work and to retroactively update existing datasets where feasible [1].

The diagram below outlines this logical troubleshooting workflow.

Guide 2: Troubleshooting a Failed PCR via Controlled Vocabulary

This guide applies a structured, terminologically-aware approach to a common lab problem.

Problem Identified: No PCR product is detected on the agarose gel. The DNA ladder is visible, so the gel electrophoresis system is functional [6].

List All Possible Explanations The possible causes are each reaction component:

Taq Polymerase,MgCl2,Buffer,dNTPs,Primers_F,Primers_R,DNA_Template. Also consider equipment (Thermocycler) and procedure (Thermocycler_Protocol) [6].Collect the Data

- Controls: Check if the

Positive_Control(a known working DNA template) produced a band. If not, the problem is likely with the core reagents or equipment [6]. - Storage and Conditions: Confirm the

PCR_Kit_Lothas not expired and was stored at the correctStorage_Tempof -20°C [6]. - Procedure: Compare your documented

Protocol_Stepsagainst the manufacturer's instructions. Note any deviations inAnnealing_TemporCycle_Count[6].

- Controls: Check if the

Eliminate Explanations If the

Positive_Controlworked and the kit was valid and stored correctly, you can eliminate the core reagents (Taq Polymerase,Buffer,MgCl2,dNTPs) as the cause. If theThermocycler_Protocolwas followed exactly, eliminate the procedure.Check with Experimentation Design an experiment to test the remaining explanations:

Primers_F,Primers_R, andDNA_Template.- Run the

DNA_Templateon a gel to check for degradation and measure itsConcentration_ng_ul[6]. - Test a new batch of primers.

- Run the

Identify the Cause The experimentation reveals the

DNA_Templateconcentration was too low. The solution is to use a template with a higherConcentration_ng_ulin the next reaction [6].

The following workflow visualizes this PCR troubleshooting process.

Quantitative Data on Ambiguity in Medical Concepts

Understanding the scope of the problem is key. The following table summarizes findings from an analysis of ambiguity in benchmark clinical concept normalization datasets, which map text to standardized codes [4].

Table 1: Ambiguity in Clinical Concept Normalization Datasets

| Metric | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset Ambiguity | <15% of strings were ambiguous within the datasets [4]. | Existing datasets poorly represent the true scale of ambiguity, limiting model training. |

| UMLS Potential Ambiguity | Over 50% of strings were ambiguous when checked against the full UMLS [4]. | Real-world clinical text contains widespread ambiguity, highlighting the need for robust normalization. |

| Dataset Overlap | Only 2% to 36% of strings were common between any two datasets [4]. | Lack of generalization across datasets; evaluation on multiple sources is necessary. |

| Annotation Inconsistency | ~40% of strings common to multiple datasets were annotated with different concepts [4]. | Highlights subjective interpretation and the critical need for consistent, vocabulary-driven annotation. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Data Annotation & Troubleshooting

| Item / Resource | Function | Role in Overcoming Ambiguity |

|---|---|---|

| Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) | A large-scale knowledge resource that integrates over 140 biomedical vocabularies [4]. | Provides the canonical set of concepts and terms (CUIs) to which natural language phrases are mapped during normalization, resolving synonymy and ambiguity [4]. |

| Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) | A comprehensive, international clinical healthcare terminology [4]. | Serves as a core controlled vocabulary within the UMLS for encoding clinical findings, procedures, and diseases. |

| RxNorm | A standardized nomenclature for clinical drugs [4]. | Provides controlled names and unique identifiers for medicines, ensuring unambiguous communication about drug data. |

| Data Management Plan (DMP) | A formal document outlining how data will be handled during and after a research project. | Serves as the ideal place to define and commit to using specific controlled vocabularies for the project from the outset [3]. |

| Positive Control | A sample known to produce a positive result, used to validate an experimental protocol [6]. | Functions as a practical "ground truth" in troubleshooting, helping to isolate ambiguous failure points (e.g., if the positive control fails, the problem is systemic). |

Definitions and Core Characteristics

The table below defines the four key types of controlled vocabularies and their primary roles in organizing knowledge [8] [9].

| Vocabulary Type | Core Definition | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject Headings [9] | A carefully selected list of words and phrases used to tag units of information for retrieval [9]. | Describing whole books or documents in library catalogs [9]. | - Often uses pre-coordinated terms (e.g., "Children and terrorism")- Traditionally developed for card catalogs, may use indirect order [9]. |

| Thesauri [8] [9] | An extension of taxonomy that adds the ability to make other statements about subjects [8]. | Providing a structured network of concepts for indexing and retrieval [9]. | - Features hierarchical, associative, and equivalence relationships- Includes "Broader Term," "Narrower Term," and "Related Term" [9]. |

| Taxonomies [8] | The science of classification, referring to the classification of things or concepts, often with hierarchical relationships [8]. | Organizing concepts or entities into a hierarchical structure [8]. | - Primarily focuses on hierarchical parent-child relationships (e.g., "Shirt" is a narrower concept of "Clothing") [8]. |

| Ontologies [8] | A formal, machine-readable definition of a set of terms and the relationships between them within a specific domain [8]. | Enabling knowledge representation and complex reasoning for computers [8]. | - Defines classes, properties, and relationships between concepts- Semantically rigorous, allowing for formal logic and inference [8]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs

1. What is the fundamental difference between a taxonomy and an ontology? The core difference lies in their purpose and complexity. A taxonomy is primarily a knowledge organization system focused on classifying concepts into a hierarchy (e.g., "Shirt" is a type of "Clothing") [8]. An ontology is a knowledge representation system that not only defines concepts but also formally specifies the properties and complex relationships between them in a way a computer can understand and reason with [8].

2. When should we use a thesaurus instead of a simple list of subject headings? A thesaurus is more powerful than subject headings when you need to capture relationships beyond simple categorization. While subject headings are excellent for labeling whole documents, a thesaurus allows you to create a web of connections using "Broader Term" (BT), "Narrower Term" (NT), and "Related Term" (RT), which can significantly improve the discovery of related information during research [9].

3. What are the main advantages of using any controlled vocabulary? Controlled vocabularies dramatically improve the precision of information retrieval by solving problems inherent in natural language [9]. They:

- Control synonyms by establishing a single preferred term (e.g., using "Automobile" instead of "Car") [9].

- Eliminate ambiguity in homographs by using qualifiers (e.g., "Pool (Game)" vs. "Pool (Swimming)") [9].

- Ensure consistency in tagging and describing information across a system or organization [9].

4. What is a potential downside of a controlled vocabulary that our team should be aware of? The main risk is unsatisfactory recall, where the system fails to retrieve relevant documents because the indexer used a different term than the one the searcher is using. This can happen if a concept is only a secondary focus of a document and not tagged, or if the searcher is unfamiliar with the specific preferred term mandated by the vocabulary [9].

5. How can we make our existing taxonomy usable by machines for the Semantic Web? The standard solution is to port your existing Knowledge Organization Scheme (KOS) using the Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS), a Semantic Web standard [8]. SKOS provides a model for expressing the basic structure and content of your taxonomy, thesaurus, or subject headings in a machine-readable format (RDF), allowing concepts, labels, and relationships to be published and understood on the web [8].

Experimental Protocol: Porting a Taxonomy to the Semantic Web with SKOS

This protocol outlines the methodology for converting a hierarchical taxonomy into a machine-readable format using SKOS, enabling its integration into the Semantic Web [8].

1. Objective To transform a traditional taxonomy into a formal, machine-understandable representation using the Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS), facilitating enhanced data interoperability and discovery in scientific data research [8].

2. Materials and Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Source Taxonomy | The existing hierarchy of concepts to be converted. |

| SKOS Vocabulary | The set of semantic web terms (e.g., skos:Concept, skos:prefLabel) used to define the model [8]. |

| RDF Serialization Tool | Software or library that outputs the final model in an RDF syntax like Turtle or RDF/XML. |

| Validation Service | A tool (e.g., an RDF validator) to check the syntactic and semantic correctness of the generated SKOS output. |

3. Step-by-Step Methodology

- Step 1: Concept Identification: Map each term in your source taxonomy to an instance of

skos:Concept[8]. - Step 2: Labeling: Assign human-readable labels to each concept. Use

skos:prefLabelfor the preferred term andskos:altLabelfor any synonyms or alternative terms [8]. - Step 3: Hierarchical Linking: Establish the hierarchical relationships from your original taxonomy using

skos:broaderandskos:narrowerproperties. For example, linkex:Shirtto a broader conceptex:Clothingusingskos:broader[8]. - Step 4: Associative Linking (Optional): Add non-hierarchical, associative relationships between related concepts using the

skos:relatedproperty (e.g., relatingex:Shirttoex:Pants) [8]. - Step 5: Serialization & Validation: Output the completed model in a standard RDF format and use a validation service to check for errors.

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the logical process and outputs for creating different types of controlled vocabularies, from simple to complex.

Controlled Vocabulary Development Workflow

Controlled vocabularies are structured, predefined lists of terms used to annotate and categorize scientific data. By ensuring that all researchers describe the same concept, entity, or observation using identical terminology, they form the bedrock of semantic interoperability—the ability of different systems to exchange data with unambiguous, shared meaning [10] [11]. In the context of scientific data research, adopting controlled vocabularies is not merely a matter of organization; it is a critical methodology that directly enhances research outcomes by improving precision, ensuring consistency, and enabling interoperability across diverse experimental systems and data sources [12] [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary data quality challenge that controlled vocabularies address? The primary challenge is semantic inconsistency, where the same concept is referred to by different names (e.g., "heart attack," "myocardial infarction," "MI") across different datasets or research groups. This inconsistency makes data aggregation, sharing, and automated analysis difficult and error-prone [10] [12]. Controlled vocabularies enforce the use of a single, standardized term for each concept, directly improving data conformance, consistency, and credibility [10].

2. How do controlled vocabularies contribute to the FAIR data principles? Controlled vocabularies are fundamental to achieving the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) principles [10] [11]. They make data more:

- Findable and Interoperable: Standardized terms act as consistent metadata, making data easier to discover and combine.

- Reusable: The unambiguous meaning provided by the vocabulary ensures data can be accurately understood and reused in future studies, even by different research teams [10].

3. Our research involves complex, multi-disciplinary data. Can a single vocabulary cover all our needs? It is uncommon for a single vocabulary to cover all needs of a complex project. The modern approach does not rely on a single universal vocabulary but instead uses federated vocabulary services that allow you to access and map terms from multiple, domain-specific vocabularies (e.g., SNOMED CT for clinical terms, GO for gene ontology) [11]. This approach supports diversity of domains while fostering reuse and interoperability [11].

4. What is the difference between a controlled vocabulary, an ontology, and a knowledge graph? These are related but distinct semantic technologies, often working together [10]:

- Controlled Vocabulary: A predefined list of standardized terms, like a dictionary (e.g., SNOMED CT) [10].

- Ontology: Defines not only the terms but also the formal relationships between them (e.g., "isa," "partof"), creating a richer data model [10].

- Knowledge Graph: A large-scale, interconnected network of real-world entities and their relationships, often built using ontologies and vocabularies as a foundation [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Data Entry Compromising Analysis

Symptoms

- Inability to merge datasets from different project teams due to terminology mismatches.

- Low precision in search results within your data repository.

- "False negative" findings in data analysis because the same entity is labeled differently.

Solution: Implement a Standardized Annotation Protocol

- Vocabulary Selection: Identify and select established, community-approved controlled vocabularies relevant to your field (e.g., SNOMED CT for clinical data, HGNC for gene names) [10] [12].

- System Integration: Integrate these vocabularies directly into your Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) or Data Management System. This can be done via dropdown menus, auto-suggestion features, or by linking to a dedicated vocabulary service [11].

- Researcher Training: Mandate training on the use of the selected vocabularies for all personnel involved in data annotation.

- Automated Quality Checks: Implement scripts or use data quality tools to periodically scan datasets for non-conforming terms and flag them for correction [10].

Problem: Achieving Semantic Interoperability with External Collaborators

Symptoms

- Significant manual effort required to map and align data structures before collaborative analysis can begin.

- Inability to leverage shared data for advanced analytics or AI initiatives due to semantic heterogeneity [12].

Solution: Adopt Interoperability Standards and Services

- Utilize Standardized APIs: Employ standard data exchange formats like HL7 FHIR alongside controlled vocabularies like SNOMED CT to ensure both structural and semantic interoperability [10] [12].

- Leverage a Vocabulary Service: Use a standards-compliant vocabulary service to access and resolve terms. Such a service allows collaborators to dynamically discover, access, and use the same set of terms, ensuring consistent interpretation [11].

- Formalize with Ontologies: For complex data relationships, develop or adopt an ontology to formally define the relationships between your data concepts, moving beyond simple terminology lists to enable automated reasoning [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key digital "reagents" and methodologies essential for implementing controlled vocabulary-based research.

| Item Name | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Controlled Vocabulary (e.g., SNOMED CT) | The foundational "reagent" that provides the standardized set of terms for annotating data, ensuring all researchers use the same label for the same concept [10]. |

| Ontology (e.g., Gene Ontology) | Provides a structured framework that defines relationships between concepts, enabling more sophisticated data integration and analysis than a simple vocabulary [10]. |

| Vocabulary Service | A digital service that provides programmatic access (via API) to controlled vocabularies and ontologies, making them discoverable, accessible, and usable across different systems [11]. |

| Semantic Web Technologies (e.g., RDF, OWL) | A set of W3C standards that provide the technical framework for representing and interlinking data in a machine-interpretable way, using vocabularies and ontologies [10] [11]. |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | A technology used to extract structured information (e.g., vocabulary terms) from unstructured text, such as clinical notes or published literature, facilitating the retrospective annotation of existing data [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: Methodology for Assessing Data Quality Improvement via Controlled Vocabulary Implementation

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the improvement in data conformance, consistency, and portability after the implementation of a controlled vocabulary for clinical phenotype annotation.

1. Materials and Software

- Datasets: Two pre-existing, heterogeneous clinical datasets (Dataset A, Dataset B) describing patient phenotypes with free-text entries.

- Controlled Vocabulary: Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO).

- Tools: A vocabulary service API [11]; data profiling and quality assessment software.

2. Procedure

- Step 1 (Baseline Measurement): Profile both Dataset A and Dataset B. Calculate baseline metrics for:

- Conformance: Percentage of phenotype terms that do not match any term in the HPO.

- Consistency: Number of unique strings used to describe the same phenotypic concept across both datasets.

- Portability: Manually estimate the analyst hours required to successfully map and merge the phenotype data from both datasets for a joint analysis.

- Step 2 (Intervention): Develop and execute an annotation pipeline that uses the HPO via a vocabulary service API to standardize all phenotype terms in both datasets. Non-matching terms are flagged for manual curation.

- Step 3 (Post-Intervention Measurement): Re-calculate the same metrics from Step 1 on the newly standardized datasets.

- Step 4 (Analysis): Compare pre- and post-intervention metrics to quantify improvement.

3. Anticipated Results The following table summarizes the expected quantitative outcomes of the experiment.

| Data Quality Indicator | Baseline Measurement (Pre-Vocabulary) | Post-Intervention Measurement | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conformance | 45% non-conforming terms | 5% non-conforming terms | +40% |

| Consistency | 22 unique strings for "short stature" | 1 unique string (HP:0004322) | +95% |

| Portability | 40 analyst hours for data merge | 2 analyst hours for data merge | +95% |

� Workflow Visualization

Controlled Vocabulary Annotation Workflow

This diagram illustrates the experimental protocol for implementing a controlled vocabulary, showing the flow from raw data to standardized, FAIR data.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary levels of data fusion in biomedical research, and how do I choose? Data fusion occurs at three main levels, each with distinct advantages and implementation requirements [13] [14]. Data-level fusion (early fusion) combines raw data directly, requiring precise spatial and temporal alignment but preserving maximal information. Feature-level fusion integrates features extracted from each modality, reducing dimensionality while maintaining complementary information. Decision-level fusion (late fusion) combines outputs from separate model decisions, offering flexibility when data cannot be directly aligned. Choose based on your data compatibility, computational resources, and analysis goals.

Q2: How can controlled vocabularies improve my multimodal data fusion outcomes? Controlled vocabularies provide standardized, organized arrangements of terms and concepts that enable consistent data description across modalities [15]. By applying these standardized terms to your metadata, you significantly enhance data discoverability, enable cross-study meta-analyses, reduce integration errors from terminology inconsistencies, and improve machine learning model training through unambiguous labeling. Common biomedical examples include SNOMED CT for clinical terms and GO (Gene Ontology) for molecular functions.

Q3: What are common pitfalls in experimental design for multimodal fusion studies? Researchers frequently encounter these issues: Data misalignment from different spatial resolutions or sampling rates; Missing modalities creating incomplete datasets; Batch effects introducing technical variations across data collection sessions; Inadequate sample sizes for robust multimodal model training; and Ignoring modality-specific noise characteristics during preprocessing.

Q4: Which deep learning architectures are most effective for fusing heterogeneous biomedical data? Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) excel with image data [14], while Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) effectively model sequential data like physiological signals. For complex multimodal integration, attention mechanisms help models focus on relevant features across modalities [14], and graph neural networks effectively represent relationships between heterogeneous data points [14]. Hybrid architectures combining these approaches often deliver optimal performance.

Q5: How do I handle missing modalities in my fusion experiments? Several strategies exist: Imputation techniques estimate missing values using statistical methods or generative models; Multi-task learning designs models that can operate with flexible input combinations; Transfer learning leverages knowledge from complete modalities; and Specific architectural designs like dropout during training can make models more robust to missing inputs.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Cross-Modality Alignment

Symptoms: Models fail to converge, performance worse than single-modality baselines, inconsistent feature mapping.

Solution:

- Preprocessing Alignment: Apply spatial co-registration for imaging data and temporal synchronization for time-series data [13]

- Feature Normalization: Standardize features across modalities using z-score normalization or modality-specific scaling

- Intermediate Representation Learning: Employ shared embedding spaces to align modalities in a common latent space

- Validation: Implement correlation analysis between modality-specific features to verify alignment quality

Problem: Model Interpretability Challenges

Symptoms: Inability to determine which modalities drive predictions, limited clinical adoption, difficulty validating biological plausibility.

Solution:

- Attention Visualization: Implement and visualize attention weights across modalities to identify influential inputs [14]

- Feature Importance Scoring: Calculate SHAP or LIME values for each modality's contribution

- Ablation Studies: Systematically remove modalities and measure performance impact

- Hierarchical Explanation: Generate explanations at data, feature, and decision levels for comprehensive interpretability

Problem: Handling Diverse Data Scales and Formats

Symptoms: Preprocessing pipelines failing, memory overflow, model bias toward high-resolution modalities.

Solution:

- Unified Data Representation: Convert all data to tensor format with standardized dimension handling

- Multi-Scale Architecture: Design models with branches accommodating different input resolutions

- Modality-Specific Encoders: Use separate feature extractors tailored to each data type before fusion

- Balanced Loss Functions: Implement weighted loss terms to prevent dominance of any single modality

Data Fusion Method Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Data Fusion Approaches in Biomedical Research

| Fusion Level | Data Requirements | Common Algorithms | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data-Level | Precise spatial/temporal alignment [13] | Wavelet transforms, CNN with multiple inputs [13] | Maximizes information preservation, enables subtle pattern detection | Sensitive to noise and misalignment, computationally intensive |

| Feature-Level | Feature extraction from each modality [13] | Support Vector Machines, Neural Networks, Principal Component Analysis [13] | Reduces dimensionality, handles some modality heterogeneity | Risk of information loss during feature extraction |

| Decision-Level | Independent model development per modality [13] | Random Forests, Voting classifiers, Bayesian fusion [13] | Flexible to implement, robust to missing data | May miss cross-modality correlations |

Table 2: Biomedical Data Types and Their Fusion Applications

| Data Modality | Characteristics | Common Applications | Fusion Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Imaging (CT, MRI, PET) [13] | High spatial information, structural data | Tumor detection, anatomical mapping [13] | Requires spatial co-registration, resolution matching |

| Genomic Data | High-dimensional, molecular-level information | Cancer subtyping, biomarker discovery [14] | Needs integration with phenotypic data, dimensionality reduction |

| Clinical Text | Unstructured, expert knowledge | Disease diagnosis, treatment planning [14] | Requires NLP processing, entity recognition |

| Physiological Signals | Temporal, continuous monitoring | Patient monitoring, disease progression [14] | Needs temporal alignment, handling of different sampling rates |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Feature-Level Fusion for Multi-Omics Integration

Purpose: Integrate genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data for comprehensive biological profiling.

Materials:

- Multi-omics dataset with matched samples

- High-performance computing environment

- Python with scikit-learn, PyTorch, or TensorFlow

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize each omics dataset separately using quantile normalization

- Feature Reduction: Apply Principal Component Analysis to each modality, retaining components explaining 95% variance

- Feature Concatenation: Combine resulting features into unified representation

- Model Training: Implement neural network with cross-modal attention mechanisms

- Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation and external validation cohorts

Troubleshooting: If model performance plateaus, consider non-linear fusion methods or address batch effects with Combat normalization.

Protocol 2: Image-Spectra Fusion for Tissue Classification

Purpose: Combine histological images with spectroscopic data for improved tissue pathology classification.

Materials:

- Paired histology images and Raman spectra from same tissue samples [13]

- Co-registration software

- Computational resources for deep learning

Procedure:

- Spatial Alignment: Co-register spectral acquisition points with image regions [13]

- Feature Extraction:

- Extract image features using pre-trained CNN (ResNet-50)

- Extract spectral features using 1D CNN or spectral decomposition

- Feature Fusion: Implement intermediate fusion with cross-modality attention

- Classification: Train multilayer perceptron on fused features

- Interpretation: Generate attention maps to identify discriminative regions

Troubleshooting: For poor alignment, implement landmark-based registration or iterative closest point algorithms.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Biomedical Data Fusion Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Data Fusion Experiments

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Data Fusion |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Imaging Modalities [13] | MRI, CT, PET, SPECT [13] | Provide structural, functional, and molecular information for complementary characterization |

| Molecular Profiling Technologies | MALDI-IMS, Raman Spectroscopy [13] | Enable molecular-level analysis with spatial information for correlation with imaging |

| Data Processing Frameworks | Python, R, MATLAB | Provide ecosystems for implementing fusion algorithms and preprocessing pipelines |

| Deep Learning Architectures [14] | CNNs, RNNs, Attention Mechanisms, GNNs [14] | Enable automatic feature learning and complex multimodal integration |

| Controlled Vocabularies [15] | SNOMED CT, Gene Ontology, MeSH [15] | Standardize terminology for consistent data annotation and cross-study integration |

| Fusion-Specific Software | Early, late, and hybrid fusion toolkits | Provide implemented algorithms and evaluation metrics for fusion experiments |

Implementing Effective Annotation: A Step-by-Step Guide for Research Data

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Vocabulary Selection Issues

Issue 1: Retrieving Too Many Irrelevant Results

Problem: Your searches are returning numerous off-topic or irrelevant documents, making it difficult to find specific research data.

Explanation: This is a classic precision problem, often caused by the inherent ambiguity of natural language in scientific literature. The same term can have multiple meanings across different sub-disciplines [9]. For example, a term like "conduction" could refer to electrical conduction in materials science or nerve conduction in biology.

Solution:

- Step 1: Identify the preferred term in your target vocabulary for your specific concept.

- Step 2: Apply vocabulary filters or subject headings in your database search.

- Step 3: Use subheadings or qualifiers to narrow the scope. For instance, in MeSH, you can use "/metabolism" or "/adverse effects" to focus your search [9].

Example: Instead of searching for pool which could mean a swimming pool, a game, or a data pool, use a qualified term like swimming pool or data pool as defined in your controlled vocabulary [9].

Issue 2: Missing Key Relevant Literature

Problem: Your searches are failing to retrieve known relevant papers or datasets, indicating poor recall.

Explanation: This occurs when different authors use varying terminology for the same concept, or when indexers apply different terms than those you're searching for [9]. New or interdisciplinary research may not yet have established terminology in the vocabulary.

Solution:

- Step 1: Identify all synonyms and related terms for your concept.

- Step 2: Consult the vocabulary's syndetic structure (broader, narrower, and related terms).

- Step 3: Use multiple search strategies combining controlled vocabulary and free-text terms [9].

Example: When searching for "heart attack" in MeSH, you would need to use the preferred term "Myocardial Infarction" but also include common synonyms in a comprehensive search.

Issue 3: Vocabulary Doesn't Cover New Concepts

Problem: Your cutting-edge research area uses terminology not yet incorporated into established vocabularies.

Explanation: Controlled vocabularies require regular updates and may lag behind rapidly evolving fields. This is particularly challenging in interdisciplinary research [9] [16].

Solution:

- Step 1: Document the gap and identify the closest available terms.

- Step 2: Use free-text terms in combination with controlled vocabulary.

- Step 3: Contact the vocabulary maintainers to suggest new terms [16].

- Step 4: For local implementations, consider extending the vocabulary while maintaining compatibility with core standards [16].

Issue 4: Inconsistent Annotation Across Research Teams

Problem: Different team members are annotating similar data with different vocabulary terms, reducing findability and interoperability.

Explanation: Without clear annotation guidelines and training, subjective interpretations of both data and vocabulary terms can lead to inconsistent tagging [9].

Solution:

- Step 1: Develop and document explicit annotation protocols.

- Step 2: Conduct regular training and inter-annotator agreement checks.

- Step 3: Implement quality control processes to review annotations.

- Step 4: Use computational tools that suggest consistent terms based on context [17].

Issue 5: Integrating Data Across Multiple Vocabularies

Problem: You need to work with data annotated using different vocabulary systems, creating integration challenges.

Explanation: Different vocabularies may have overlapping but not identical coverage, different levels of specificity, and different structural principles [16].

Solution:

- Step 1: Map terms between vocabularies using established crosswalks where available.

- Step 2: Consider using upper-level ontologies or intermediate frameworks like the PMD Core Ontology that can bridge multiple domain-specific vocabularies [16].

- Step 3: Implement a federated approach that preserves original annotations while enabling cross-vocabulary search.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the fundamental difference between a controlled vocabulary and a simple list of keywords?

A: A controlled vocabulary is a carefully selected list of terms where each concept has one preferred term (solving synonym problems), and homographs are distinguished with qualifiers (e.g., "Pool (swimming)" vs. "Pool (game)"). This reduces ambiguity and ensures consistency, unlike unstructured keywords which suffer from natural language variations [9].

Q: How do I decide between using a subject headings system like MeSH versus a thesaurus for my research domain?

A: The choice depends on your specific needs. Subject heading systems like MeSH are typically broader in scope and use more pre-coordination (combining concepts into single headings), while thesauri tend to be more specialized and use singular direct terms with rich syndetic structure (broader, narrower, and related terms). Consider your domain specificity and whether you need detailed hierarchical relationships [9].

Q: What are the limitations of controlled vocabularies that I should be aware of?

A: The main limitations include: potential unsatisfactory recall if indexers don't tag relevant concepts; vocabulary obsolescence in fast-moving fields; indexing exhaustivity variations; and the cost and expertise required for maintenance and proper use. They work best when combined with free-text searching for comprehensive retrieval [9].

Q: How can I assess whether a particular controlled vocabulary is well-maintained and suitable for long-term research projects?

A: Look for evidence of regular updates, clear versioning, an active governance process with community input, published editorial policies, and examples of successful implementation in similar research contexts. Community-driven curation, as seen in the PMD Core Ontology for materials science, is a positive indicator [16].

Q: What should I do if my highly specialized research area lacks an appropriate controlled vocabulary?

A: Start by documenting your terminology needs and surveying existing related vocabularies for potential extension. Consider developing a lightweight local vocabulary while aligning with broader standards where possible. Engage with relevant research communities to build consensus around terminology, following models like the International Materials Resource Registries working group [17].

Domain-Specific Vocabulary Standards Comparison

Table 1: Major Domain-Specific Vocabulary Standards and Their Applications

| Vocabulary Standard | Primary Domain | Scope & Specificity | Maintenance Authority | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) [9] | Medicine, Life Sciences, Drug Development | Broad coverage of biomedical topics | U.S. National Library of Medicine | Extensive synonym control, well-established hierarchy, wide adoption |

| Materials Science Vocabulary (IMRR) [17] | Materials Science & Engineering | Domain-specific terminology | RDA IMRR Working Group | Addresses domain-specific ambiguity, supports data discovery |

| COAR (Connecting Repositories) | Research Repository Networks | Resource types, repository operations | COAR Community | Focused on interoperability between repository systems |

| PMD Core Ontology [16] | Materials Science & Engineering | Mid-level ontology bridging general and specific concepts | Platform MaterialDigital Consortium | Bridges semantic gaps, enables FAIR data principles, community-driven |

Table 2: Technical Characteristics of Vocabulary Systems

| Characteristic | Subject Headings (e.g., MeSH) | Thesauri | Ontologies (e.g., PMDco) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Term Structure | Often pre-coordinated phrases | Mostly single terms | Complex concepts with relationships |

| Semantic Relationships | Basic hierarchy & related terms | BT, NT, RT relationships | Rich formal relationships & axioms |

| Primary Use Case | Document cataloging & retrieval | Indexing & information retrieval | Semantic interoperability & AI processing |

| Complexity of Implementation | Moderate | Moderate to High | High |

| Flexibility & Extensibility | Lower | Moderate | Higher |

Experimental Protocol: Vocabulary Implementation and Testing

Methodology for Controlled Vocabulary Assessment

Objective: Systematically evaluate and implement domain-specific controlled vocabularies for scientific data annotation.

Materials Needed:

- Access to candidate vocabulary standards

- Representative sample of research data/documents

- Annotation software or tools

- Data management system

Procedure:

Requirements Analysis Phase

- Identify core concepts and relationships in your research domain

- Map existing terminology and synonyms used by research team

- Define use cases for vocabulary implementation (search, integration, etc.)

Vocabulary Evaluation Phase

- Assess coverage of domain concepts in candidate vocabularies

- Evaluate structural compatibility with your data models

- Check for machine-readable formats and API availability

- Review maintenance history and community adoption

Pilot Implementation Phase

- Select a representative subset of data for pilot annotation

- Train annotators on vocabulary principles and specific terms

- Establish inter-annotator agreement metrics

- Annotate pilot dataset using selected vocabulary

Performance Assessment Phase

- Conduct precision and recall tests using sample queries

- Compare retrieval effectiveness against baseline keyword search

- Gather user feedback on usability and comprehension

- Identify gaps and implementation challenges

Refinement and Deployment Phase

- Develop local extensions if needed, documenting deviations

- Create usage guidelines and training materials

- Implement quality control processes

- Plan for ongoing vocabulary maintenance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Vocabulary Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Vocabulary Management Systems | Create, edit, and maintain controlled vocabularies | Developing local extensions to standard vocabularies |

| Annotation Platforms | Apply vocabulary terms to research data | Consistent tagging of experimental data and publications |

| Crosswalk Tools | Map terms between different vocabulary systems | Data integration across research groups using different standards |

| APIs and Web Services | Programmatic access to vocabulary content | Building vocabulary-aware applications and search interfaces |

| Lineage Tracking Tools | Document vocabulary evolution and term changes | Maintaining consistency in long-term research projects |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Vocabulary Selection Decision Process

Diagram 2: Data Annotation Workflow Using Controlled Vocabulary

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Data Curation Workflow Issues

Q: How can I handle inconsistent data formats from different sources during curation? A: Implement a standardized data curation workflow that includes steps for format checking and normalization. Use tools like KNIME to build workflows that automatically retrieve chemical data (e.g., SMILES strings), check their correctness, and curate them into consistent, ready-to-use datasets. This process transforms raw data into structured, context-rich collections ready for analysis [18] [19].

Q: What is the best way to manage large volumes of unstructured data for scientific research? A: Apply intelligent data curation to bring order to unstructured chaos through extensive metadata and data intelligence. This involves organizing, filtering, and preparing datasets across distributed storage environments. For genomic sequences or research data, curation links datasets through key-value metadata pairs and automates retention and compliance procedures [19].

Q: How can I ensure my curated datasets remain lean and valuable over time? A: Establish curation policies and search-based rules that consistently eliminate duplicates, obsolete, and low-value files while surfacing the datasets that truly matter. This maintains governance and control while ensuring compliance, auditability, and traceability across all data environments [19].

Automated Tagging & Annotation Challenges

Q: My automated tagging system is producing inconsistent labels. How can I improve accuracy? A: Define clear annotation guidelines that specify exactly what to label, how to label it, and what each label means. Provide clear labeling instructions that reduce confusion and ensure consistency across annotators and automated systems. Implement regular quality checks where a second annotator or quality manager verifies the annotations [20] [21].

Q: What are the most common pitfalls in developing automated tagging systems for scientific data? A: The main challenges include managing large datasets, ensuring data reliability and consistency, managing data privacy concerns, preventing algorithmic bias, and controlling costs. Solutions involve using tools with batch processing capabilities, setting clear guidelines, implementing data protection compliance, training annotators to recognize bias, and clearly defining project scope for cost management [20].

Q: How granular should my automated tagging be for scientific data? A: Annotation granularity should be tailored to your project's specific needs. Determine whether you need broad categories or very specific labels, and avoid over-labeling if unnecessary. For example, in an e-commerce dataset, you might label items as "clothing" or use more granular labels like "t-shirts" or "sweaters" depending on your research requirements [20].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

Protocol 1: Standardized QSAR Model Development

This protocol implements a standard procedure to develop Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship models using freely available workflows [18].

Table 1: QSAR Model Development Workflow

| Step | Process | Tools/Methods | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Data Retrieval | Retrieve chemical data (SMILES) from web sources | Raw chemical dataset |

| 2 | Data Curation | Check chemical correctness and prepare consistent datasets | Curated, ready-to-use datasets |

| 3 | Descriptor Calculation | Calculate and select chemical descriptors | Molecular descriptors |

| 4 | Model Training | Implement six machine learning methods for classification | Initial QSAR models |

| 5 | Hyperparameter Tuning | Optimize model parameters using systematic approaches | Tuned model architectures |

| 6 | Validation | Handle data unbalancing and validate model performance | Validated predictive models |

Data Annotation Workflow for AI/ML

Protocol 2: High-Quality Data Annotation Pipeline

This methodology ensures accurate, consistent labeled data for training AI models in scientific research contexts [20] [21].

Table 2: Data Annotation Quality Control Measures

| Quality Control Measure | Implementation Method | Frequency | Success Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annotation Guidelines | Define clear labeling instructions with examples | Project initiation | 95% annotator comprehension |

| Annotator Training | Provide thorough training on labeling standards | Pre-project & quarterly | >90% accuracy on test sets |

| Quality Checking | Second annotator verification process | Every 100 samples | <5% error rate |

| Feedback Loops | Regular feedback on annotation accuracy | Weekly review sessions | 10% monthly improvement |

| Bias Prevention | Diverse annotator teams & balanced datasets | Dataset construction | <2% demographic bias |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Data Curation & Annotation Workflows

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| KNIME Analytics Platform | Builds automated data curation workflows | Retrieving and curating chemical data for QSAR models [18] |

| Data Annotation Tools (e.g., Picsellia, LabelBox) | Provides AI-assisted labeling capabilities | Creating high-quality training data for AI models across multiple domains [20] |

| Diskover Data Curation Platform | Organizes unstructured data through metadata enrichment | Transforming raw data into structured, context-rich collections for AI/BI pipelines [19] |

| Gold Datasets | Reference standard for model validation | Testing model output accuracy against expert-annotated benchmarks [21] |

| Semantic Annotation Tools | Assigns metadata to text for NLP understanding | Helping machine learning models understand meaning and intent in scientific text [21] |

Workflow Visualization Diagrams

Diagram 1: Data Curation to Automated Tagging

Diagram 2: Annotation Project Workflow

Leveraging AI and Machine Learning for Scalable Annotation

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: What are the most common causes of poor model performance despite extensive data annotation, and how can they be diagnosed?

Poor model performance often stems from issues in the training data rather than the model architecture. The primary causes and diagnostic methods are [21] [22]:

- Low Annotation Quality: Inconsistent or inaccurate labels confuse the model. Diagnose this by measuring Inter-Annotator Agreement (IAA), where multiple annotators label the same data sample; a low agreement rate indicates unclear guidelines or inconsistent application [22] [23].

- Biased Training Data: The dataset does not represent the real-world scenario, causing the model to underperform on specific data types. Diagnose this by visualizing data distribution to spot under-represented classes or biases [24] [21].

- Inadequate Data Curation: The dataset contains redundant or irrelevant samples. Use data curation platforms (like Lightly) that employ active learning to select the most valuable data points for annotation, filtering out redundancies [24].

FAQ 2: Our annotation throughput is too slow for project deadlines. What automation features should we prioritize to accelerate labeling without sacrificing quality?

Prioritize platforms and tools that offer the following automation features [24] [25] [23]:

- AI-Assisted Labeling: Use pre-trained models (e.g., SAM-2 for images, GPT-4o for text) to perform automatic pre-labeling. Human annotators then only need to verify and correct these suggestions, which can increase productivity several times over [24] [22].

- Smart Data Curation: Implement tools that automatically filter, sort, and select the most valuable data points from large datasets for prioritization in the annotation queue, reducing time spent on low-value samples [24].

- Interpolation for Video: For video data, use tools that automate annotation between keyframes. Annotators label an object in a few frames, and the AI interpolates its position across the entire sequence [21] [25].

FAQ 3: How can we ensure consistency and quality when multiple annotators (including domain experts and crowdworkers) are working on the same project?

Maintaining quality with a distributed team requires a structured process [22] [23]:

- Create Detailed Annotation Guidelines: Develop a "gold standard" with crystal clear instructions, numerous examples, and defined approaches for edge cases. This is the project's "constitution" [22] [23].

- Implement a Multi-Stage QA Process: Use a consensus model where the same data sample is independently labeled by several annotators. Divergent samples are sent to a senior reviewer for a final decision [22].

- Use a Unified Annotation Platform: Employ a platform that supports role-based access, centralized guideline management, and built-in quality metrics (like IAA tracking) to ensure all annotators work from the same source of truth [24] [25].

FAQ 4: For a new controlled vocabulary project, what is the recommended step-by-step protocol to establish a foundational annotated dataset?

The following experimental protocol ensures a high-quality foundation [22] [23]:

- Step 1: Define Scope and Guidelines. Clearly define the controlled vocabulary and create exhaustive annotation guidelines with examples for each term, including how to handle ambiguous cases.

- Step 2: Start Small and Calibrate. Begin with a small pilot dataset (e.g., 100-200 samples). Have all annotators label this set and measure IAA. Use disagreements to refine the guidelines and calibrate the team.

- Step 3: Annotate with Quality Gates. Begin full-scale annotation using a platform that supports a review workflow. Every annotation should be reviewed by a different team member. Maintain a high IAA threshold (e.g., >90%) for the dataset.

- Step 4: Iterate and Expand. Use the initial curated dataset to train a preliminary model. Use model-assisted labeling and active learning to identify and prioritize the most valuable data points for the next annotation cycle.

FAQ 5: What are the trade-offs between using open-source versus commercial annotation platforms for a sensitive, domain-specific research project?

The choice depends on the project's specific needs for security, customization, and support [23]:

| Feature | Open-Source Platforms (e.g., CVAT, Doccano) | Commercial Platforms (e.g., Encord, Labelbox, Labellerr) |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | Free to use and modify. | Subscription or license fee. |

| Data Security | Self-hosted option offers full control (on-premise). | Enterprise-grade security & compliance (SOC2, HIPAA); often cloud-based [24]. |

| Customization | High; code can be modified for specific use cases. | Limited; dependent on vendor's feature set. |

| Support & Features | Relies on community forums; limited features for complex tasks. | Dedicated technical support; wide range of features and integrations [24] [25]. |

| Best For | Projects with strong technical expertise, specific custom needs, and on-premise security requirements. | Projects requiring security compliance, user-friendliness, complex workflows, and reliable support. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Inter-Annotator Agreement (IAA) for Quality Control

Objective: To quantify the consistency and reliability of annotations across multiple annotators [22]. Materials: A representative sample of the dataset (50-100 items), detailed annotation guidelines, 3+ annotators. Methodology:

- Preparation: Select a random data sample and ensure all annotators are trained on the guidelines.

- Annotation: Each annotator independently labels the entire sample.

- Calculation: Use a statistical measure appropriate for your data:

- Cohen's Kappa (for 2 annotators) or Fleiss' Kappa (for 3+ annotators) is suitable for categorical labels [22].

- Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) is used for continuous measurements.

- Analysis: A Kappa value > 0.8 indicates excellent agreement, 0.6-0.8 substantial, and < 0.6 indicates a need for guideline refinement and re-calibration [22].

Protocol 2: Implementing an Active Learning Loop for Efficient Annotation

Objective: To strategically select the most informative data points for annotation, maximizing model performance while minimizing labeling cost [24] [23]. Materials: A large pool of unlabeled data, an annotation platform, a base model. Methodology:

- Initial Model Training: Train a model on a small, initially labeled dataset.

- Inference and Uncertainty Sampling: Use the model to make predictions on the unlabeled pool. Identify data points where the model is most uncertain (e.g., highest entropy in predicted probabilities).

- Priority Annotation: Send these uncertain, high-value data points for human annotation.

- Model Retraining: Retrain the model with the newly annotated data.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 until the model reaches the desired performance level, creating an efficient, iterative annotation workflow.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, iterative workflow of a modern, AI-assisted data annotation pipeline.

AI-Assisted Scalable Annotation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential tools and platforms for building a scalable annotation pipeline for scientific data [24] [25] [23]:

| Item Name | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Encord | A unified platform for scalable annotation of multimodal data (images, video, DICOM), offering AI-assisted labeling and model evaluation tools, ideal for complex computer vision and medical AI tasks [24]. |

| Labellerr | An AI-powered platform providing automation features and customizable workflows for annotating images, video, and text, supporting collaborative annotation and robust quality control [24] [25]. |

| Lightly | A data curation tool that uses self-supervised and active learning to intelligently select the most valuable data from large datasets for annotation, reducing redundant labeling effort [24]. |

| CVAT | An open-source, web-based tool for annotating images and videos. It supports multiple annotation types and offers algorithmic assistance, suitable for training computer vision models [24] [25]. |

| Roboflow | A platform focused on building computer vision applications, providing tools for data curation, labeling, model training, and deployment [24]. |

| Scale AI / Labelbox | Commercial platforms that provide a complete environment for managing annotation workflows, including intuitive interfaces, quality control metrics, and AI-assisted labeling capabilities [25] [22]. |

| Prodigy | An AI-assisted, scriptable annotation tool for training NLP models, designed for efficient, model-in-the-loop data labeling [25]. |

| Amazon SageMaker Ground Truth | A data labeling service that provides built-in workflows for common labeling tasks and access to a workforce, while also supporting custom workflows [23]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs

Q1: My retrieval system provides irrelevant chunks of text, leading to poor LLM responses. How can I improve accuracy?

A: This is often caused by a suboptimal chunking strategy that breaks apart semantically coherent ideas. Implement a hierarchical chunking approach.

- Problem: Simple chunking by token count can split sentences and concepts mid-thought.

- Solution: Use semantic chunking that ensures each chunk represents a complete idea or logical unit [26]. Structure your documents into a hierarchy (e.g., Document → Topics → Sections → Paragraphs) [26]. During retrieval, the system can first identify a relevant parent node (like a section) and then drill down to the most specific child node or chunk, preserving context [26].

Q2: I am hitting the context window limit of my LLM when providing source documents. How can I provide sufficient context more efficiently?

A: Utilize a hierarchical index to provide summarized context instead of full, verbose chunks.

- Problem: Feeding multiple long documents into the context window is inefficient and often impossible.

- Solution: Index your documents with a structure that includes contextual summaries at parent levels (e.g., a chapter summary) [26]. When a query is processed, the system can first retrieve a high-level summary of a relevant section to provide the LLM with broad context, and then supplement it with only the most critical, fine-grained chunks for detail, drastically reducing token usage [26].

Q3: My vector database searches are slow as my dataset has grown massively. What optimization strategies can I use?

A: This requires optimizing your indexing strategy within the vector database.

- Problem: A brute-force search across millions of vectors is computationally expensive.

- Solution: Implement advanced indexing strategies in your vector database [27]. Two common methods are:

- HNSW (Hierarchical Navigable Small World) Graphs: Ideal for a balance between high query speed and accuracy, perfect for real-time applications [27].

- IVF (Inverted File Index): Efficient for high-dimensional data, it clusters the data and only searches the most promising clusters, improving speed [27]. The choice depends on your specific need for speed versus accuracy.

Q4: How can I make my AI agent's decision-making process more transparent and explainable?

A: Implement a task-category oriented memory system.

- Problem: Storing all experiences in a single, flat memory pool makes it hard to understand why certain decisions are made.

- Solution: As the EHC agent framework demonstrates, you can classify successful and failed experiences (or document chunks) into predefined, mutually exclusive categories [28]. When a query is processed, the system can report which category of information it is drawing from. This classification improves the agent's understanding of task types and makes its retrieval process more transparent and easier to debug [28].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Hierarchical RAG System

This protocol details the methodology for constructing a RAG system with a hierarchical document index, as conceptualized in the cited literature [26].

Preprocessing and Hierarchical Chunking

- Input: Raw documents (e.g., PDFs, text files).

- Procedure:

- Clean the text by removing extraneous formatting and symbols.

- Split documents logically into a hierarchy. A suggested structure is Parent Nodes (e.g., Document Titles, Chapter Headings) and Child Nodes (e.g., Sections, Paragraphs) [26].

- Chunk the child nodes into the smallest retrievable units using semantic chunking, which ensures each chunk contains a complete thought or idea, rather than using a fixed token count [26].

- Output: A set of text nodes with preserved parent-child relationships.

Embedding Generation and Index Construction

- Input: Hierarchically structured text nodes.

- Procedure:

- Generate Embeddings: Use a pre-trained embedding model (e.g.,

all-MiniLM-L6-v2[26]) to convert every node (parent summaries, child nodes, and chunks) into vector embeddings. - Build Index: Store all embeddings in a vector database (e.g., FAISS, ChromaDB). The index should store metadata linking child chunks to their parent nodes.

- Create Summary Embeddings: For each parent node, generate a summary of its content and create an embedding for that summary to facilitate top-level retrieval [26].

- Generate Embeddings: Use a pre-trained embedding model (e.g.,

- Output: A hierarchically indexed vector store.

Dynamic Query and Retrieval Workflow

- Input: User query.

- Procedure:

- Top-Down Retrieval: The system first calculates the similarity between the query embedding and the embeddings of high-level parent nodes (or their summaries) [26].

- Drill-Down Refinement: For the most similar parent nodes, the system then searches through their associated child nodes and chunks to find the most granular and relevant information.

- Contextualized Response Generation: The retrieved parent-level context and child-level details are synthesized by the LLM to generate a final, grounded response [26].

- Output: A relevant, context-aware answer from the LLM.

Hierarchical RAG Retrieval Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key software tools and components essential for building a system for AI-enhanced indexing with hierarchical embeddings.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

Sentence Transformers (e.g., all-MiniLM-L6-v2) |

A Python library used to generate dense vector embeddings (numerical representations) of text chunks. These embeddings capture semantic meaning for similarity-based retrieval [26]. |

| Vector Database (e.g., FAISS, ChromaDB, Pinecone) | A specialized database optimized for storing and performing fast similarity searches on high-dimensional vector embeddings, which is the core of retrieval operations [26] [27]. |

| Hierarchical Indexing Framework (e.g., LlamaIndex) | A data framework that acts as a bridge between raw documents and LLMs. It helps structure data into searchable hierarchical indexes (vector, keyword, summary-based) to efficiently locate relevant information [29]. |

| LLM API/Endpoint (e.g., GPT, Falcon-7B) | The large language model that receives the retrieved context and query, and synthesizes them to generate a coherent, final answer for the user [27]. |

| Controlled Vocabulary | A predefined set of standardized terms used to annotate and categorize data. This enhances reproducibility, enables efficient data validation, and can be used to classify experiences or document types within a memory system [1] [3]. |

The table below consolidates key performance metrics and findings from the analysis of hierarchical indexing and AI in related fields.

| Metric / Finding | Description / Value | Context / Source |

|---|---|---|

| AI Drug Discovery Success Rate | 80-90% in Phase I trials [30] | Compared to 40-65% for traditional methods, highlighting AI's potential to reduce attrition. |

| Traditional Drug Development Cost | Exceeds $2 billion [30] | Establishes the high cost baseline that AI-driven efficiencies aim to address. |

| Traditional Drug Development Timeline | Over a decade [30] | Highlights the significant time savings AI can potentially enable. |

| Indexing Strategy: HNSW | Balances high query speed and accuracy [27] | Recommended for real-time search applications and recommendation systems. |

| Indexing Strategy: IVF | Efficient for high-dimensional data [27] | Recommended for scalable search environments by clustering data to narrow searches. |

Integration with Research Pipelines and Data Repositories

Troubleshooting Guides

Pipeline Failure: Diagnosis and Resolution

Q: Our research pipeline has failed in production. What is a systematic process to diagnose the root cause?

A: Follow this methodical troubleshooting process to minimize downtime and data corruption [31]:

- Start with the Logs: Review error messages and logs from your orchestration or processing tools (e.g., Airflow, Databricks, AWS Glue). Logs help pinpoint the nature and location of the failure [31].

- Investigate Common Culprits: Examine these frequent causes [31]:

- Expired Credentials: API keys, secrets, or access tokens.

- Recent Changes: Code deployments, schema modifications, or configuration updates.

- Resource Constraints: Insufficient memory, disk space, or compute capacity.

- Connectivity Issues: Network failures or firewall blocks.

- Data Quality Issues: Corrupt, missing, or unexpectedly formatted source data.

- Isolate the Failure Point: Determine which stage of your data architecture (e.g., Bronze, Silver, Gold medallion layers) is affected. Saving data at each stage enables targeted debugging and reprocessing [31].

- Test and Validate: Reproduce the issue in a test environment. Run unit and integration tests on transformation logic to catch errors [31].

- Handle Transient Issues: For temporary problems (e.g., network timeouts), a simple pipeline rerun may suffice, but monitor for recurring patterns [31].

Q: How can I troubleshoot API-related failures that impact data landing in the bronze layer?