Contamination Correction in Microbiome Research: A Comprehensive Guide from Prevention to Validation

This article provides a systematic framework for addressing contamination in microbiome studies, a critical challenge that disproportionately impacts low-biomass samples and can compromise research validity.

Contamination Correction in Microbiome Research: A Comprehensive Guide from Prevention to Validation

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for addressing contamination in microbiome studies, a critical challenge that disproportionately impacts low-biomass samples and can compromise research validity. It covers foundational concepts of contamination sources and their impact on data integrity, best-practice protocols for experimental design and contamination prevention, advanced computational tools and strategies for contamination detection and removal, and robust methods for result validation and comparative analysis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current consensus recommendations and cutting-edge methodologies to enhance the rigor and reproducibility of microbiome research in biomedical and clinical contexts.

Understanding Contamination: Sources, Impacts, and Risks in Microbiome Analysis

Why is contamination a particularly critical issue in microbiome research?

Contamination is a critical issue because the presence of external microbial DNA can severely distort the true composition of a sample's microbial community. This is especially problematic in low-biomass samples (those containing minimal microbial material), where the contaminating "noise" can be equal to or greater than the authentic biological "signal" [1].

In these samples, even small amounts of contaminating DNA introduced during sampling or processing can lead to false positives, making it appear that microbes are present in environments that are actually sterile or nearly sterile. This can, at best, cast doubt on study quality and, at worst, contribute to incorrect conclusions that misinform clinical and research applications [1]. High-profile debates regarding the existence of microbiomes in environments like the human placenta, brain, and some tumors have often stemmed from unresolved contamination issues [1].

Contamination can be introduced at virtually every stage of a microbiome study, from sample collection to data generation. The table below summarizes the primary sources.

Table: Common Sources of Contamination in Microbiome Studies

| Stage of Workflow | Specific Contamination Sources |

|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Human operators, sampling equipment, collection vessels, ambient air, adjacent environments (e.g., skin during a blood draw) [1] [2] |

| Sample Processing & Storage | Laboratory surfaces, plasticware, glassware, DNA extraction kits, and other molecular biology reagents [1] [3] |

| Downstream Analysis | Cross-contamination between samples during plate setup (well-to-well leakage), and index hopping during sequencing [1] |

Which sample types are most vulnerable to contamination?

Samples with low microbial biomass are most susceptible. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between sample type, biomass, and contamination risk.

What are the best practices for preventing contamination during sample collection?

Prevention is the most effective strategy for managing contamination. Key practices include:

- Decontaminate Equipment: Use single-use, DNA-free collection vessels where possible. For re-usable equipment, decontaminate with 80% ethanol (to kill cells) followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution like sodium hypochlorite (bleach) to remove trace DNA [1].

- Use Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear gloves, masks, and clean suits or lab coats to limit contamination from skin, hair, or aerosols generated by breathing [1].

- Collect and Process Controls: Always include negative controls, such as an empty collection vessel, a swab of the air, or an aliquot of the preservation solution used. These controls are processed alongside your real samples to identify the contaminating sequences [1] [3].

What experimental protocols are used to control for contamination?

Robust experimental design includes specific protocols to identify and account for contamination. Two critical protocols are detailed below.

Protocol 1: Including and Processing Negative Controls

Purpose: To identify DNA contaminants derived from reagents, kits, and the laboratory environment [1] [3].

Methodology:

- Type of Controls: Prepare multiple types of controls, such as "no-sample" blanks (only lysis buffer), "mock" extractions (with no sample), and sampling controls (e.g., a swab of a sterile surface) [1] [4].

- Parallel Processing: These controls must be included from the point of collection and carried through every downstream step identically to the biological samples, including DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing [1].

- Analysis: During bioinformatic processing, use software tools like

decontam(an R package) to statistically identify and remove contaminating sequences that are more prevalent in negative controls than in true samples [4].

Protocol 2: Rigorous Sample Collection for Low-Biomass Fluids (e.g., Urine)

Purpose: To obtain a sample that accurately represents the urobiome while minimizing contamination from the urethra, genitals, and skin [2] [4].

Methodology:

- Sample Type and Volume: Differentiate between "urinary bladder" samples (collected via catheterization) and "urogenital" samples (voided). For voided samples, a larger volume (≥ 3.0 mL) is recommended for more consistent microbial profiling [2] [4].

- Collection: Use sterile collection cups. For voided samples, collect mid-stream urine. Process samples immediately or store at -80°C within 6 hours of collection [4].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge samples at 4°C and 20,000 × g for 30 minutes. Discard the supernatant and use the pellet for DNA extraction [4].

- Host DNA Depletion: For samples with high host cell shedding, consider using DNA extraction kits with host depletion steps (e.g., QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit) to increase the proportion of microbial reads in shotgun metagenomic sequencing [4].

How can I visualize the complete workflow for contamination-aware microbiome research?

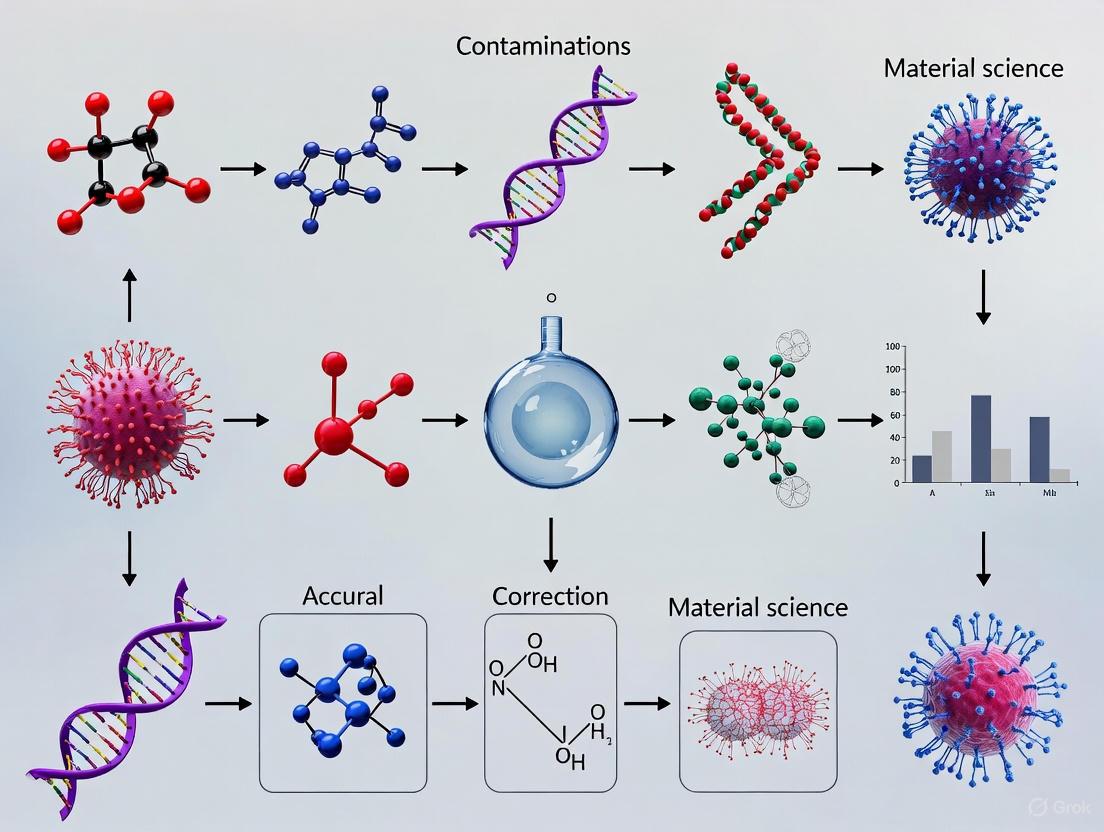

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow that integrates contamination prevention and control at every stage.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Contamination Control

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) | Degrades contaminating DNA on surfaces and equipment [1]. | Critical for decontaminating non-disposable tools. Must be used after ethanol treatment. |

| DNA-Free Collection Vessels | Pre-packaged, sterile containers for sample collection [1]. | Prevents introduction of contaminants at the source. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Gloves, masks, and clean suits to limit operator-derived contamination [1]. | A simple and cost-effective first line of defense. |

| AssayAssure / OMNIgene·GUT | Preservative buffers to stabilize microbial community at room temperature [2]. | Crucial for field collection or when immediate freezing is not possible. |

| Host Depletion Kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit) | Selectively degrades host (e.g., human/animal) DNA to enrich for microbial DNA [4]. | Vital for low-biomass, high-host-DNA samples (e.g., urine, tissue). |

| Decontam Software Package | A statistical tool to identify and remove contaminating sequences post-sequencing [4]. | Requires properly sequenced negative controls to function effectively. |

In microbiome research, contamination is not just an inconvenience—it is a critical methodological challenge that can compromise data integrity and lead to spurious conclusions. This is particularly true for low-biomass samples where the target DNA signal can be easily overwhelmed by contaminant noise. This guide addresses the major contamination sources and provides practical solutions for researchers seeking to maintain sample purity throughout their experimental workflows.

Contamination can be introduced at virtually every stage of microbiome research, from sample collection to data analysis. The table below summarizes the four primary sources and their characteristics.

Table 1: Major Contamination Sources in Microbiome Research

| Contamination Source | Description | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reagents & Kits | Microbial DNA present in DNA extraction kits, purification kits, and molecular-grade water [5]. | Distinct "kitome" profiles vary by brand and manufacturing lot; common contaminants include species of Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Sphingomonas [1] [5]. |

| Human Operators | Microbial cells and DNA shed from researchers' skin, hair, and aerosols generated by breathing or talking [1]. | Skin-associated bacteria (e.g., Staphylococcus, Propionibacterium); contamination risk increases with improper personal protective equipment (PPE) use [1] [6]. |

| Equipment & Surfaces | Microbial reservoirs on sampling tools, laboratory benches, and analytical instruments [7] [8]. | Washing machine drums and seals [7]; microscope stages and sample storage containers [8]; non-sterile collection tubes and vessels [1]. |

| Cross-Contamination | Transfer of DNA or sequence reads between samples during processing or sequencing [1] [5]. | Well-to-well leakage during PCR setup [1]; "index hopping" in multiplexed sequencing runs [5]; transfer between samples in shared equipment (e.g., washing machines) [7]. |

The relationships between these contamination sources and the sample are visualized below.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our negative controls consistently show bacterial DNA from our DNA extraction kits. How should we handle this data? Background DNA in reagents is a known issue, especially for low-biomass samples [5]. It is crucial to:

- Profile the Contamination: Include multiple extraction blanks (reagents only) in every sequencing run to define the "kitome" for your specific reagent lot [5].

- Informatic Removal: Use bioinformatics tools like Decontam, which can identify and remove contaminant sequences based on their higher prevalence in low-concentration samples and negative controls [5].

- Demand Transparency: Request that manufacturers provide comprehensive background microbiota data for each reagent lot [5].

Q2: We observe sporadic contamination across sample plates with no clear source. What should we investigate? Sporadic contamination often points to cross-contamination or environmental sources.

- Check for Well-to-Well Leakage: Ensure proper sealing of plates during centrifugation and PCR. Review pipetting techniques to prevent aerosol generation [1].

- Audit Laboratory Surfaces: Swab equipment surfaces (e.g., microscope stages, vial holders) and the interior of equipment used for sample storage to identify environmental reservoirs [8].

- Verify Personnel Practices: Ensure that gloves are worn and changed frequently, and that PPE (lab coats, masks) is used correctly to minimize human-derived contamination [1].

Q3: Are there quantitative data on contamination levels from common sources? Yes, recent studies have quantified contamination from various sources, providing a benchmark for evaluating your own contamination risk.

Table 2: Quantitative Data on Microbial Contamination from Recent Studies

| Source | Quantitative Finding | Context & Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Household Washing Machines | Avg. bacterial count: 6.50 ± 2.46 Log₁₀/swab (front-load); 3.79 ± 1.73 Log₁₀/swab (top-load) [7]. | Surface swabs from 10 household machines; higher moisture retention in front-load machines leads to significantly higher microbial loads [7]. |

| DNA Extraction Reagents | Significant batch-to-batch variability in background microbiota profiles [5]. | Metagenomic sequencing of extraction blanks from four commercial reagent brands; contamination profiles were distinct between brands and different lots of the same brand [5]. |

| Laboratory Environment | Airborne spore concentrations range from 100 to 10,000 spores per cubic meter [8]. | General measurement of environmental contaminants; even seemingly clean labs can harbor thousands of potential contaminants [8]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Contamination Monitoring with Extraction and Sampling Blanks

Purpose: To identify and account for contaminants introduced from reagents, the sampling environment, and collection materials [1] [9].

Materials:

- Sterile, DNA-free water (e.g., 0.1µm filtered molecular-grade water) [5].

- Same DNA extraction kits and reagents used for actual samples.

- Sterile swabs and sample collection vessels.

Procedure:

- Extraction Blanks: For each batch of extractions, include at least one control where sterile water is used as the input instead of a sample. Process it identically through the entire DNA extraction and library preparation workflow [5].

- Sampling Blanks (Field Controls): During sample collection, expose a sterile swab or leave a collection vessel open to the air in the sampling environment. For clinical sampling, swab the decontaminated skin of the operator or patient before the procedure [1].

- Processing: Sequence these control samples alongside your actual samples.

- Analysis: Compare the microbial profiles of your samples to the blanks. Sequences prevalent in blanks are likely contaminants and should be treated with caution or removed computationally [5].

Protocol for Surface Decontamination of Sampling Equipment

Purpose: To eliminate microbial cells and trace DNA from equipment and tools that contact samples [1].

Materials:

- 80% ethanol solution.

- DNA-degrading solution (e.g., fresh 0.5-1% sodium hypochlorite (bleach) solution or commercial DNA removal products).

- UV-C light sterilizing cabinet (optional).

- Autoclave.

Procedure:

- Initial Cleaning: Physically clean surfaces to remove debris.

- Ethanol Treatment: Wipe down tools and surfaces with 80% ethanol to kill contaminating organisms. Allow to air dry [1].

- DNA Degradation: Treat with a DNA-degrading solution like sodium hypochlorite to remove residual trace DNA. Note: Bleach is corrosive; ensure compatibility with equipment and allow for proper rinsing with DNA-free water if needed [1].

- Sterilization (where applicable): For heat-resistant tools, autoclave at 121°C for 15-20 minutes is the gold standard [8].

- UV Treatment (alternative): For surfaces and heat-sensitive equipment, UV-C light exposure for 15-30 minutes can be effective [1] [8].

The following workflow integrates these control and decontamination strategies into a complete sample handling process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Contamination Control

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Molecular-Grade Water | DNA-free water used for preparing solutions and as input for extraction blanks. It is analyzed for the absence of nucleases and bioburden [5]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control | A defined mock community of bacterial strains. Serves as an in-situ positive control for extraction and sequencing efficiency, helping to distinguish true signal from contamination [5]. |

| Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) | A potent DNA-degrading agent. Used to remove trace DNA from surfaces and equipment after ethanol treatment. Critical for eliminating "sterile but DNA-positive" contamination [1]. |

| HEPA Filter/Laminar Flow Hood | Provides a sterile, particle-free air environment for sample processing. Reduces the introduction of airborne contaminants and environmental spores [8]. |

| Unique Dual Indexed Primers | Primers with unique dual indices for sequencing. Significantly reduce the risk of misassigned reads (index hopping) between samples during multiplexed sequencing runs [9]. |

Low-biomass microbiome samples, which contain minimal microbial DNA, present unique challenges for researchers. These samples, including certain human tissues (blood, urine, skin), and specific environments (treated drinking water, hyper-arid soils), are vulnerable to contamination and technical artifacts that can compromise data integrity. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate the unique vulnerabilities of low-biomass samples and implement robust contamination correction protocols.

FAQs: Understanding the Core Challenges

1. What makes a sample "low-biomass," and why is this problematic? Low-biomass samples contain very low levels of microbial DNA, often approaching the detection limits of standard sequencing methods [1]. This includes samples from sterile sites, certain human tissues (respiratory tract, fetal tissues, blood), and environments like treated drinking water or hyper-arid soils [1] [10]. The problem is proportional: in high-biomass samples (like stool), contaminant DNA is a small fraction of the total signal. In low-biomass samples, however, even tiny amounts of contaminating DNA from reagents, kits, or the laboratory environment can constitute most or all of the sequenced material, leading to spurious results and incorrect conclusions [11] [3].

2. What are the most common sources of contamination? Contamination can be introduced at every stage of research, from sample collection to data analysis. Key sources include:

- Human operators: Microbial cells and DNA from skin, hair, or aerosols generated by breathing or talking [1].

- Sampling equipment: Collection vessels, swabs, and tools that haven't been properly decontaminated [1] [2].

- Laboratory reagents and kits: DNA extraction kits, PCR master mixes, and water often contain trace microbial DNA [11] [12].

- Cross-contamination between samples: Also known as "well-to-well" contamination, where DNA leaks between adjacent samples during plate-based DNA extraction or library preparation [12].

3. Beyond contamination, what other biases affect low-biomass studies?

- Technical Artifacts: Low-biomass samples are more susceptible to technical biases like over-amplification during PCR, which can skew community profiles [11].

- Confounding Factors: In human studies, factors like age, diet, antibiotic use, and geography can influence the microbiome and must be accounted for in the study design [3]. In animal studies, cage effects—where co-housed animals share microbiota—are a major confounder [3].

- DNA Extraction Variability: Different DNA extraction methods, and even different batches of the same kit, can introduce significant variation and impact downstream results [3] [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Preventing Contamination During Sample Collection & Handling

Problem: Samples are contaminated during collection, storage, or transport, leading to unreliable data.

Solution: Implement a contamination-aware sampling design.

- Decontaminate Equipment: Use single-use, DNA-free collection tools. Reusable equipment should be decontaminated with 80% ethanol (to kill cells) followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution like bleach or UV-C light (to remove DNA remnants) [1].

- Use Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Operators should wear gloves, masks, cleansuits, and other PPE to minimize the introduction of human-associated contaminants [1].

- Collect and Process Controls: Always include field and sampling controls. These can be empty collection vessels, swabs of the air, or aliquots of preservation solution processed alongside your samples. They are essential for identifying the source and extent of contamination [1].

Table: Essential Controls for Low-Biomass Studies

| Control Type | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Controls | DNA-free water or blank swabs taken through all processing steps. | Identifies contaminants from reagents, kits, and the laboratory environment. |

| Field Blanks | Sterile collection containers opened and closed at the sampling site. | Detects contamination from the air and sampling environment. |

| Positive Controls | Mock microbial communities with known composition. | Verifies that the entire workflow, from DNA extraction to sequencing, is functioning correctly. |

Guide 2: Mitigating Cross-Contamination in the Lab

Problem: "Well-to-well" or cross-contamination during DNA extraction and library preparation causes samples to appear similar to their neighbors on a processing plate.

Solution: Optimize wet-lab procedures to minimize sample-to-sample transfer.

- Randomize Samples: Do not group low-biomass samples together or near high-biomass samples on extraction plates. Randomize their positions to prevent systematic bias [12].

- Choose Extraction Methods Wisely: Plate-based extraction methods tend to have higher rates of well-to-well contamination than manual, single-tube methods. Consider the trade-offs between throughput and contamination risk [12].

- Include Blank Wells: When using plate-based methods, leave blank wells (filled with water) between samples, especially those with very different biomass levels. This acts as a physical buffer and helps monitor cross-contamination [12].

Guide 3: Designing a Robust Experimental Workflow

A well-designed experimental workflow is critical for generating reliable data from low-biomass samples. The following diagram outlines the key stages and the specific vulnerabilities to address at each step.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow highlighting contamination vulnerabilities at each stage.

Guide 4: Selecting and Optimizing Wet-Lab Protocols

Problem: Inappropriate choice of DNA extraction method, storage conditions, or sequencing approach leads to biased or low-yield results.

Solution: Standardize protocols based on best practices for low-biomass samples.

- DNA Extraction: Different DNA isolation kits can yield varying amounts of DNA and affect taxa composition. While total DNA concentration may differ, studies show that with proper controls, different kits can still produce comparable sequencing depths for the 16S rRNA gene [2]. Use a single kit batch for an entire study to minimize variation [3].

- Sample Storage: Immediate freezing at -80°C is the gold standard. When this is not feasible (e.g., field collection), preservative buffers like OMNIgene·GUT or AssayAssure can maintain microbial composition at room temperature for a limited time, though their effectiveness varies [2]. Refrigeration at 4°C can also be a viable short-term option for some sample types [2].

- Sequencing and Primer Selection:

- 16S rRNA Sequencing: The choice of hypervariable region (e.g., V1V2, V3V4, V4) can influence results. For urinary microbiota, primers targeting the V1V2 region have been shown to provide better species richness compared to V4, which may underestimate diversity [2].

- Shotgun Metagenomics: This approach sequences all DNA in a sample, providing superior taxonomic resolution and functional information, but requires sufficient DNA yield and careful handling of host DNA contamination [11] [13].

Table: Comparison of Common Microbiome Analysis Techniques

| Method | Target | Advantages | Limitations | Best for Low-Biomass? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing | A single marker gene (e.g., 16S in bacteria) | Cost-effective; well-established protocols; good for taxonomy. | Limited resolution; primer bias; cannot assess function. | Use with stringent controls and optimized primers [13] [2]. |

| Shotgun Metagenomics | All genomic DNA in a sample | Higher taxonomic resolution; reveals functional potential. | More expensive; computationally intensive; high host DNA can be problematic. | Powerful if sufficient DNA is obtained; can reveal novel pathogens [11] [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Biomass Research

| Item | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Decontamination Solutions (e.g., bleach, UV-C light) | To remove contaminating DNA from surfaces and equipment. | Sterility (killing cells) is not the same as being DNA-free. DNA removal requires specific treatments [1]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) (gloves, masks, cleansuits) | Creates a barrier between the researcher and the sample to prevent contamination from human skin, hair, and aerosols [1]. | The level of PPE should be commensurate with the sample's biomass; low-biomass samples require more stringent protection. |

| Preservative Buffers (e.g., OMNIgene·GUT, AssayAssure) | Stabilizes microbial DNA in samples that cannot be immediately frozen, allowing for storage and transport at ambient temperatures [2]. | Effectiveness varies by sample type and preservative. May influence the detection of certain bacterial taxa. |

| DNA/RNA-Free Water and Reagents | Used in DNA extraction and PCR to minimize the introduction of external microbial DNA. | A critical source of contamination; should be sourced from reputable suppliers and tested via negative controls [12]. |

| Mock Microbial Communities | Serve as positive controls by providing a known mixture of microbial DNA to verify the accuracy and performance of the entire analytical workflow [3]. | Allows researchers to quantify technical variability and detect biases introduced during sample processing. |

Successfully navigating the low-biomass challenge requires a paradigm shift from standard microbiome practices. It demands rigorous contamination prevention at every stage, from experimental design and sample collection to data analysis and reporting. By adopting the guidelines, troubleshooting strategies, and best practices outlined in this technical support center—such as the meticulous use of controls, careful protocol selection, and awareness of cross-contamination risks—researchers can significantly improve the reliability and reproducibility of their findings in these vulnerable sample types.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary consequences of contamination in microbiome research? Contamination undermines every aspect of microbiome science. Scientifically, it can lead to false discoveries and spurious associations, distorting our understanding of microbial ecology [1]. Clinically, this can result in incorrect conclusions about disease etiology, misguide therapeutic development, and compromise patient diagnostics [1] [14]. In diagnostics, contamination can cause false positives/negatives, reduce test accuracy, and ultimately erode trust in microbiome-based clinical tools [14].

Q2: Which types of samples are most vulnerable to contamination? Samples with low microbial biomass are at greatest risk because the contaminant DNA can constitute most or even all of the detected signal [1] [3]. Such samples include:

- Human tissues/fluids: Urine [4], fetal tissues [1], blood [1], breast milk [1], and the respiratory tract [1].

- Environmental samples: The atmosphere, hyper-arid soils, treated drinking water, and the deep subsurface [1].

Q3: How can I identify contamination in my dataset?

The most effective strategy is the consistent use and sequencing of negative controls (e.g., empty collection vessels, swabs exposed to lab air, aliquots of sterile preservation solution) alongside your biological samples [1] [15]. These controls should undergo the exact same processing pipeline. Bioinformatic tools like decontam can then use the data from these controls to identify and remove putative contaminant sequences from your dataset [4].

Q4: What are the best practices for preventing contamination during sample collection?

- Decontaminate equipment: Use single-use, DNA-free collection tools. Reusable equipment should be decontaminated with 80% ethanol followed by a DNA-degrading solution like sodium hypochlorite (bleach) [1].

- Use Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear gloves, masks, and clean suits to minimize contamination from the researcher [1].

- Collect sampling controls: Actively sample potential contamination sources (e.g., air, preservation solution, PPE surfaces) to identify the profile of contaminants [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Irreproducible Results in Low-Biomass Samples

Potential Cause: The dominant signal in your data comes from contaminating DNA introduced during sampling or laboratory processing, rather than the sample itself [1] [15].

Solution: Implement a Rigorous Contamination Control Protocol

- Design Phase: Plan for multiple negative controls (e.g., kit reagents, swab blanks) to be processed in parallel with your biological samples [1] [3].

- Collection Phase:

- Processing Phase:

- Use dedicated workspace and equipment for low-biomass work, if possible.

- Include a well-characterized positive control (mock microbial community) to assess bias and efficiency in DNA extraction and amplification [15].

- Analysis Phase:

Problem: High Levels of Host DNA Overwhelm Microbial Signals in Metagenomic Sequencing

Potential Cause: Samples like saliva, urine, or tissue biopsies contain a high burden of host cells, making it cost-prohibitive to sequence deeply enough to recover sufficient microbial reads [16] [4].

Solution: Employ Host DNA Depletion Methods Several commercial kits can enrich microbial DNA by selectively removing host DNA. The following table summarizes methods evaluated in a recent study on canine urine (a relevant model for human low-biomass samples) [4]:

| Method / Kit Name | Principle of Action | Key Findings from Comparative Studies |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit | Selective lysis of human/host cells followed by enzymatic degradation of the released DNA. | In a urine model, this kit yielded the greatest microbial diversity and maximized metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) recovery [4]. |

| NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit | Uses a protein (MBD2-Fc) that binds to methylated CpG sites, which are common in host DNA but rare in microbes. The bound host DNA is then removed magnetically [16]. | Effectively depletes host DNA; shown to retain microbial diversity in saliva samples without significant bias for most taxa [16]. |

| Molzym MolYsis | Selective lysis of human cells and enzymatic degradation of DNA, followed by microbial cell lysis. | Evaluated in host-spiked urine samples; performance can vary, and optimization for specific sample types is recommended [4]. |

| Zymo HostZERO | Proprietary chemistry designed to deplete host DNA while preserving microbial DNA. | One of several methods available; comparative studies suggest that individual sample variation (e.g., by patient/dog) can be a stronger driver of profile differences than the kit itself [4]. |

Problem: Sequencing Biases are Skewing the Quantification of Bacterial Communities

Potential Cause: The use of different 16S rRNA gene regions, sequencing platforms, or DNA polymerases can introduce systematic biases, causing certain species to be consistently over- or under-represented [17] [15].

Solution: Use a Reference-Based Bias Correction Model

- Create a Mock Community: Use a defined mix of known bacterial species at predetermined ratios.

- Sequence the Mock: Process the mock community alongside your samples using your standard NGS protocol.

- Quantify with ddPCR: Use droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) with specific gene assays (e.g., targeting the rpoB gene) to establish the true, absolute abundance of each species in the mock community [17].

- Calculate and Apply Correction Factors: By comparing the ddPCR results (true ratio) to the NGS results (observed ratio), you can calculate a PCR efficiency value for each species. These efficiencies form a "bias index" that can be applied to correct biased data from real samples, significantly improving accuracy [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Defined Mock Microbial Communities (e.g., from ZymoResearch, BEI Resources, ATCC) | Serve as positive controls for validating DNA extraction efficiency, assessing PCR/sequencing bias, and optimizing bioinformatics parameters [15]. |

| DNA Decontamination Solutions (e.g., Sodium Hypochlorite, UV-C light, DNA-ExitusPlus) | Used to decontaminate work surfaces and reusable equipment to destroy contaminating DNA [1]. |

| Host Depletion Kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit, NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit) | Selectively remove host DNA from samples rich in human cells (e.g., saliva, urine, tissue) to enrich for microbial DNA and improve sequencing efficiency [4] [16]. |

| Inhibitor Removal Technology (included in many DNA extraction kits) | Removes humic acids, bile salts, and other compounds from complex samples (e.g., stool) that can inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions like PCR [4]. |

Visual Workflow: Consequences and Control of Contamination

The following diagram illustrates the pathways through which contamination enters the research workflow and its cascading consequences, while also highlighting key control points.

Best Practices in Experimental Design and Contamination Prevention

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why are pre-sampling strategies so critical in microbiome research? Contamination is an inevitable challenge in DNA-based sequencing. In high-biomass samples (like stool), the true microbial "signal" is strong enough that contaminant "noise" has a minimal impact. However, in low-biomass samples (such as tissue, blood, or water), contaminants can make up a large proportion of the sequenced DNA, leading to false positives and completely misleading results [1] [10]. Proper pre-sampling strategies are the first and most crucial line of defense to ensure data integrity.

FAQ 2: Our lab uses ethanol to sterilize equipment. Is this sufficient? No, ethanol alone is not sufficient. While ethanol is effective at killing viable contaminating cells, it does not effectively remove persistent environmental DNA. After ethanol treatment, cell-free DNA can remain on surfaces and contaminate your samples. A two-step process is recommended: decontaminate with 80% ethanol to kill organisms, followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution (e.g., sodium hypochlorite/bleach, UV-C irradiation, or commercial DNA removal solutions) to destroy residual DNA [1].

FAQ 3: What is the most common source of human-derived contamination during sampling? The researchers themselves are a primary source. Contamination can come from skin cells, hair, and aerosol droplets generated from breathing or talking [1]. This is why appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is a fundamental barrier method, not just for safety but for sample purity.

FAQ 4: We always include negative controls. Why do we still get contamination? A common issue is cross-contamination or "well-to-well leakage," where DNA from biological samples leaks into adjacent control samples during processing steps on a plate [18] [19]. This can introduce genuine sample DNA into your controls, making decontamination computationally very challenging. Ensuring proper plate layout and using computational tools designed to handle leakage can mitigate this.

FAQ 5: How can we verify that our decontamination protocols are effective? The effectiveness of your entire workflow—from sampling to processing—should be validated by including and sequencing multiple types of negative controls (e.g., empty collection vessels, swabs of the air, aliquots of preservation solutions) [1]. If these controls show minimal microbial DNA, your protocols are likely effective. If controls show high biomass or specific patterns, it indicates a breach in your decontamination or barrier methods.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Consistent detection of common laboratory contaminants (e.g., Pseudomonas, Bacillus) across samples.

- Potential Cause: Reagent contamination or improperly decontaminated sampling equipment.

- Solutions:

- Treat Reagents: Use DNA-free reagents. If not available, consider treating reagents with UV irradiation or DNase to degrade contaminating DNA [20].

- Enhance Equipment Sterilization: Move beyond ethanol-only cleaning. Implement a two-step decontamination: clean with 80% ethanol, followed by a DNA-removal step using a validated method like 1-3% sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or commercial DNA degradation solutions [1].

- Include Controls: Always process blank reagent controls through the entire DNA extraction and sequencing workflow to identify the contaminant profile of your kits [20] [18].

Problem: High levels of human skin bacteria (e.g., Cutibacterium, Staphylococcus) in samples.

- Potential Cause: Inadequate use of personal protective equipment (PPE) or sample exposure to the laboratory environment.

- Solutions:

- Enforce PPE Protocol: Ensure all personnel are wearing appropriate PPE, including gloves, masks, goggles, and clean lab coats or coveralls. Gloves should be decontaminated with ethanol and/or changed frequently, and should not touch any surface before sample collection [1] [2].

- Minimize Handling: Handle samples as little as possible and within a controlled environment, such as a laminar flow hood, to create a physical barrier between the sample and the room air [1].

- Environmental Controls: Swab benches, hoods, and other surfaces to monitor the laboratory's background contaminant load.

Problem: High variability in negative controls processed in the same batch.

- Potential Cause: Well-to-well leakage during plate-based steps in DNA extraction or PCR setup.

- Solutions:

- Optimize Plate Layout: Strategically place negative controls on the plate, physically separating them from high-biomass samples. Do not place them adjacent to each other [18].

- Seal Plates Properly: Use high-quality, properly sealing plate foils to prevent aerosol cross-contamination between wells.

- Use Advanced Bioinformatics: Employ decontamination algorithms like

SCRuBthat can explicitly model and correct for well-to-well leakage by using the spatial location of samples on the plate [18] [19].

Problem: Discrepant results and poor reproducibility between different laboratories.

- Potential Cause: Lack of standardized, detailed protocols for sample collection and pre-processing.

- Solutions:

- Protocol Standardization: Develop and adhere to a single, detailed protocol with specified part numbers for labware and equipment. Using shared, annotated video protocols can ensure consistency across users and labs [21] [22].

- Centralize Reagents: Where possible, have a central organizing lab distribute key reagents (e.g., synthetic communities, growth media) to all participating labs to minimize batch-to-batch variation [21].

- Harmonize Metadata: Collect and report a standardized set of clinical and experimental metadata (e.g., sample collection method, storage conditions, antibiotic usage) to allow for proper comparison and interpretation of results [2] [23].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Essential Materials for Pre-Sampling Decontamination and Barrier Methods

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) | A potent DNA-degrading agent used to remove contaminating environmental DNA from surfaces and equipment after initial cleaning with ethanol [1]. |

| UV-C Light Source | Used to sterilize surfaces, plasticware, and even some reagents by damaging microbial DNA. Effective for decontaminating workstations and tools [1]. |

| Commercial DNA Removal Solutions | Ready-to-use solutions specifically formulated to degrade DNA. Often used as a more consistent and safer alternative to bleach for delicate equipment [1]. |

| Single-Use, DNA-Free Collection Kits | Pre-sterilized swabs, collection tubes, and containers that eliminate the need for decontamination and ensure no contaminating DNA is introduced at the point of sampling [1] [2]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Gloves, masks, goggles, and cleanroom suits act as a physical barrier to prevent contamination of samples from the researcher's skin, hair, and breath [1]. |

| Laminar Flow Hood / Biosafety Cabinet | Provides a sterile, HEPA-filtered air workstation to protect samples from environmental aerosols and particles during processing [1]. |

| Sample Preservation Buffers | Solutions like AssayAssure or OMNIgene·GUT that stabilize microbial DNA at room temperature or 4°C when immediate freezing at -80°C is not feasible [2]. |

Experimental Workflow for Pre-Sampling Contamination Control

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive, multi-stage workflow for preventing contamination, from initial planning to sample verification.

Diagram: Contamination Control Workflow. This workflow outlines the four key phases for ensuring sample integrity, from initial preparation to final verification.

Table: Types and Purposes of Essential Negative Controls

| Control Type | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Equipment/Reagent Blank | An empty collection tube or an aliquot of the sterile preservation/processing solution taken through the entire workflow [1]. | Identifies contaminants introduced from collection materials, reagents, and DNA extraction kits [20] [18]. |

| Environmental Swab | A swab of the air in the sampling environment, the PPE of the researcher, or the sampling bench surface [1]. | Characterizes the background contaminant load of the sampling and processing environment. |

| Process Control | For specific procedures, this can include drilling fluid (in subsurface sampling) or a swab of maternal skin (in fetal tissue sampling) [1]. | Accounts for contamination from specific, non-sample materials that contact the specimen. |

| Sample-Sample Control | A "mock" sample used to track cross-contamination between samples during processing, crucial for identifying well-to-well leakage [18]. | Helps identify and computationally correct for spillover between samples on a processing plate. |

FAQs on Contamination Prevention

Contamination can be introduced at virtually every stage of research, from sample collection to sequencing. The primary sources include:

- Laboratory Reagents and Kits: DNA extraction kits and PCR reagents are frequent culprits, containing trace amounts of microbial DNA that become significant in low-biomass samples [24].

- Sampling Equipment & Personnel: Non-sterile equipment, gloves, and exposure to the researcher's skin, clothing, or aerosols can introduce contaminants [1] [24].

- Cross-Contamination: During processing in 96-well plates, well-to-well leakage is a major problem due to shared seals and minimal separation between wells [25].

- The Laboratory Environment: Contaminants are present in the air and on laboratory surfaces [24].

Why are low-biomass samples particularly vulnerable?

In low-biomass samples (e.g., tissue, blood, water), the amount of target microbial DNA is very small. Contaminating DNA from reagents or the environment can therefore constitute a large proportion—sometimes even the majority—of the sequenced DNA, leading to spurious results and incorrect biological conclusions [24] [1]. High-biomass samples like fecal samples are less susceptible because the target DNA signal overwhelms the contaminant noise [1].

What are the best practices for sample collection to minimize contamination?

A contamination-informed sampling design is critical [1]. Key practices include:

- Using Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear gloves, masks, and clean suits to limit contact between samples and contamination from personnel [1].

- Decontaminating Equipment: Use single-use, DNA-free collection vessels. Reusable equipment should be decontaminated with ethanol to kill organisms, followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution like bleach to remove residual DNA [1].

- Including Controls: Collect field blanks (e.g., an empty collection vessel, a swab exposed to the air) and process them alongside your samples to identify contaminants introduced during collection and handling [1].

How can I prevent cross-contamination during DNA extraction in 96-well plates?

Well-to-well contamination in standard 96-well plates is a significant issue. Mitigation strategies include:

- The Matrix Tube Method: Replace 96-well plates with single, barcoded tubes for sample lysis. This eliminates the shared seal and reduces well-to-well contamination dramatically, from 19% to 2% in one study [25].

- Sample Randomization: Avoid processing high-biomass and low-biomass samples on the same plate. Randomize samples across plates to ensure technical variables are not confounded with biological groups [24] [25].

What should I do if my negative controls show contamination?

Contamination in controls must be addressed before drawing biological conclusions.

- Bioinformatic Removal: Use computational tools to identify and remove taxa that are also present in your negative controls from the entire dataset [24].

- Re-evaluate Results: If contaminant operational taxonomic units (OTUs) are driving the clustering patterns in your analysis (e.g., in principal coordinate analysis), the biological interpretation is likely flawed and requires re-processing with a different kit or more stringent controls [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Unexpected microbial taxa are dominant in low-biomass samples

Potential Cause: Contamination from laboratory reagents or cross-contamination from other samples is overwhelming the low signal. Solutions:

- Check Your Controls: Compare the taxa in your samples to those in your negative (blank) extraction controls. Shared taxa are likely contaminants [24] [1].

- Review Lab Protocols: Ensure you are using a DNA extraction kit known for low contamination, such as the MoBio kit used by the Human Microbiome Project [24]. For plate-based extractions, consider switching to a single-tube method like the Matrix Tube approach [25].

- Re-process Samples: If possible, re-extract DNA using a different batch of kits or a different kit altogether to see if the contaminant profile changes [24].

Issue: Samples cluster by extraction batch or sequencing run, not by biological group

Potential Cause: Batch effects are technically introduced variation that can confound biological signals. Solutions:

- Randomize Samples: Ensure samples from different biological groups (e.g., case and control) are randomly distributed across DNA extraction batches, PCR batches, and sequencing runs [24].

- Include Controls in Every Batch: Process negative controls in every extraction and PCR batch to identify batch-specific contaminants [1].

- Statistical Correction: In analysis, test whether experimental variables (like batch) correlate strongly with the major principal components. If they do, the batch effect is likely driving the results [24].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Using Negative Controls and a Culture Dilution Series to Monitor Contamination

This protocol, based on the work of Salter et al., helps characterize the contamination profile of your lab workflow [24].

Methodology:

- Prepare Samples: Create a series of five 10-fold dilutions of a pure bacterial culture (e.g., Salmonella bongori) that is not a common contaminant.

- Include Controls: Alongside the dilutions, process multiple negative controls containing ultrapure water.

- Parallel Processing: Extract DNA and perform 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the dilution series and controls simultaneously using your standard protocol.

- Analysis: Compare the sequences from the dilution series, the pure culture, and the negative controls. As the biomass decreases (higher dilution), contaminants from the extraction kit and reagents will become increasingly dominant in the sequence data.

Protocol: The Matrix Method for Reducing Well-to-Well Contamination

This high-throughput method uses barcoded single tubes instead of 96-well plates to minimize cross-contamination during extraction [25].

Workflow:

- Sample Collection: Collect samples directly into pre-barcoded Matrix Tubes.

- Stabilization and Metabolite Extraction: Add 95% (vol/vol) ethanol to the tube to stabilize the microbial community and act as a solvent for metabolites. Shake and centrifuge.

- Transfer Metabolite Extract: Transfer the supernatant (metabolite extract) to a new plate for LC-MS/MS analysis.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Proceed with the standard nucleic acid extraction protocol from the pellet remaining in the original Matrix Tube.

The following diagram illustrates this workflow:

Matrix Method Workflow for Paired Analyses

Quantitative Data on Contamination

Table 1: Comparison of Contamination in Plate vs. Matrix Tube Extraction Methods Data adapted from a study comparing the MagMAX plate-based method and the Matrix Tube method, measuring 16S rRNA gene levels in negative controls via qPCR [25].

| Method | Total Blanks | Contaminated Blanks | Contamination Rate | Average Contamination Concentration (ng/µL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 96-Well Plate | 672 | 128 | 19% | 0.21 |

| Matrix Tubes | 672 | 14 | 2% | 0.026 |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Prevention

| Item | Function in Contamination Control |

|---|---|

| DNA Decontamination Solution (e.g., bleach) | Degrades contaminating DNA on surfaces and equipment that cannot be autoclaved. Essential after ethanol decontamination to remove DNA traces [1]. |

| Pre-sterilized, DNA-free Swabs & Collection Tubes | Single-use items that prevent the introduction of contaminants during the initial sample collection [1]. |

| Ethanol (95% vol/vol) | Used to stabilize microbial communities at the point of collection and serves as a solvent for simultaneous metabolite extraction, as in the Matrix Method [25]. |

| Ultrapure Water | Serves as a critical negative control during DNA extraction and PCR to identify contaminants originating from reagents and the laboratory environment [24]. |

| Barcoded Matrix Tubes | Single tubes that replace 96-well plates for sample collection and lysis, significantly reducing the risk of well-to-well cross-contamination while maintaining high throughput [25]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are controls especially critical in low microbial biomass studies? In low microbial biomass samples (e.g., from blood, placenta, or drinking water), the amount of target microbial DNA is very small. Consequently, contaminant DNA from reagents, kits, or the laboratory environment can make up a large portion, or even all, of the sequenced DNA, making true biological signal difficult to distinguish from noise [26] [1]. Without proper controls, these contaminants can be misinterpreted as authentic microbiota, leading to spurious results and incorrect conclusions [3].

Q2: What is the minimum number of controls I should include in my study? The exact number depends on the study scale, but the consensus is to include multiple negative controls. At least one negative control should be included for each unique DNA extraction batch and for each kit lot used [1]. For large studies, including multiple negative controls across different processing batches is essential to account for technical variability and identify contamination patterns [15] [3].

Q3: My negative controls have detectable microbial DNA. Does this invalidate my experiment? Not necessarily. The presence of microbial DNA in negative controls is common. The key is to use this information to informatically identify and remove contaminating sequences from your biological samples during data analysis [1] [19]. If the contamination level in your controls is very high, it may overwhelm the signal in low-biomass samples, and the experiment may need to be repeated with stricter contamination mitigation protocols [26].

Q4: How do I choose between different decontamination software tools? The choice depends on your study design and research goal.

- If your goal is to estimate the original composition of your samples as closely as possible and you have well-location data to account for well-to-well leakage, a tool like SCRuB (available via the

micRocleanR package) is recommended [19]. - If your primary goal is strict removal of contaminant features for biomarker discovery and you have multiple sample batches, the Biomarker Identification pipeline in the

micRocleanpackage may be more appropriate [19]. - Always use the Filtering Loss (FL) statistic or similar metrics to quantify the impact of decontamination and avoid over-filtering your data [19].

Q5: Can I use a commercially available mock community as a positive control for any microbiome study? While commercial mock communities (e.g., from ZymoResearch, BEI, or ATCC) are excellent resources, their validity must be considered. They often contain only bacteria and fungi, so they may not be fully representative if your study focuses on archaea, viruses, or other eukaryotes [15]. It is crucial to verify that the positive control is relevant for the specific environment you are investigating.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Results Across Sample Batches

Symptoms: Microbial profiles vary significantly between processing batches, making biological interpretation difficult. Potential Causes:

- Different lots of DNA extraction kits, which can have varying contaminant backgrounds [3].

- Minor protocol deviations between technicians or over time.

- Well-to-well cross-contamination during library preparation [1]. Solutions:

- Prevention: Use the same lot of DNA extraction kits for the entire study if possible. Implement standardized, written protocols and train all personnel. Use plate maps that space out high-biomass and low-biomass samples to reduce cross-contamination risk [1].

- Correction: Include at least one negative control per extraction batch. Use decontamination tools like

microDeconorSCRuBthat can model and subtract cross-contamination based on negative controls and sample well locations [19].

Issue 2: Mock Community Results Do Not Match Expected Composition

Symptoms: When sequencing a positive control mock community, the relative abundances of the known species are skewed, or some species are missing. Potential Causes:

- DNA extraction bias: Some bacterial cells are more difficult to lyse than others (e.g., Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative) [15].

- PCR amplification bias: Primers may not bind equally to all 16S rRNA gene variants, and organisms with high-GC content may amplify less efficiently [15] [27].

- Bioinformatic errors: Clustering sequences into OTUs or ASVs can lump distinct species together or split a single species into multiple features [15]. Solutions:

- Wet-lab: Use a mock community that is appropriate for your study system. For amplicon sequencing, consider using a pre-extracted DNA mock community to isolate PCR and sequencing biases from DNA extraction biases [15].

- Bioinformatic: Use the known composition of the mock community to optimize bioinformatics parameters, such as the similarity threshold for clustering [15]. This helps ensure your pipeline recovers the expected community structure as accurately as possible.

Issue 3: Suspected Contamination in Low-Biomass Samples

Symptoms: Low-biomass samples have similar microbial profiles to your negative controls, or you detect taxa commonly identified as contaminants (e.g., Delftia, Burkholderia). Potential Causes:

- Contaminant DNA from reagents, kits, or the laboratory environment is comprising most of the DNA in your samples [26] [1]. Solutions:

- Re-analysis: Use a control-based decontamination method. The

decontampackage in R, for example, can identify contaminants as features that are more abundant in low-concentration samples or that are present in negative controls [19]. - Validation: If a specific signal is critical, try to validate it with an independent method that does not involve DNA amplification, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [1].

- Future Prevention: Adopt strict contamination mitigation practices during sampling (e.g., using PPE, decontaminating equipment with bleach) and DNA extraction (e.g., in a UV hood, using DNA-free reagents) [1].

Table 1: Types and Applications of Negative Controls

| Control Type | Description | Purpose | When to Include |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Control | A blank tube containing only molecular grade water or buffer that undergoes the entire DNA extraction and library preparation process. | Identifies contaminants derived from DNA extraction kits, laboratory reagents, and the library preparation workflow. | For every batch of DNA extractions [1]. |

| Sampling Control | A sterile swab or sample collection container exposed to the air during sampling or an aliquot of sterile preservation solution. | Identifies contaminants introduced from the sampling equipment, preservatives, or the sampling environment. | During field collection or clinical sampling [1]. |

| Equipment Control | A swab of surfaces, gloves, or PPE used during sampling or laboratory work. | Monitors specific contamination sources from equipment or personnel. | When validating a new sampling protocol or when a contamination source is suspected [1]. |

Table 2: Commercially Available Mock Communities for Positive Controls

| Source | Composition | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZymoResearch | Defined mixture of bacteria and fungi. | Pre-extracted DNA or cellular material available; well-characterized. | Does not include archaea or viruses; may not be representative of all environments [15]. |

| BEI Resources | Defined synthetic bacterial communities. | Developed as a standardized resource for the research community. | Primarily bacterial; may not cover full phylogenetic diversity of your samples [15]. |

| ATCC | Mock microbial communities. | Includes both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including pathogens. | Similar limitations regarding archaea, viruses, and eukaryotes [15]. |

| Custom Made | Researcher-defined mixture of cultured strains. | Can be tailored to a specific environment (e.g., include archaea). | Requires significant effort to culture, mix, and standardize; not as readily comparable across labs [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Comprehensive Negative Control Strategy

This protocol outlines the steps for integrating negative controls from sample collection to data analysis, based on recent consensus guidelines [1].

- Planning: Before sampling, identify all potential sources of contamination (e.g., human operators, sampling equipment, reagents). Prepare sterile, DNA-free collection vessels and decontaminate any re-usable equipment with 80% ethanol followed by a DNA-degrading solution like bleach or UV-C irradiation.

- Sampling:

- Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves, mask, and clean suit to minimize human-derived contamination.

- Collect sampling controls: expose a sterile swab to the air for the duration of sampling, and include an empty collection vessel.

- DNA Extraction and Sequencing:

- Include a process control (e.g., blank of molecular grade water) for every batch of DNA extractions, and certainly for each new kit lot.

- If using a 96-well plate, position negative controls in a way that helps identify well-to-well cross-contamination (e.g., scattered across the plate).

- Data Analysis:

- Sequence all controls alongside your biological samples.

- Use the sequencing data from the negative controls with a decontamination tool (e.g.,

decontam,SCRuB, ormicRoclean) to identify and remove contaminating sequences from your biological dataset.

Protocol 2: Using a Mock Community to Validate Your Workflow

This protocol describes how to use a positive control mock community to benchmark your entire wet-lab and computational pipeline [15] [27].

- Selection: Choose a commercially available mock community that best reflects the microbial composition you expect in your samples. If studying a unique environment, consider creating a custom mock community.

- Integration: Treat the mock community exactly like a biological sample. Include it in the same DNA extraction batch, library preparation, and sequencing run.

- Analysis:

- Process the mock community data through your standard bioinformatics pipeline.

- Compare the final taxonomic profile generated by your pipeline to the known, expected composition of the mock community.

- Benchmarking:

- Calculate metrics like sensitivity (were all expected species detected?) and specificity (were any unexpected species detected?).

- Assess quantitative accuracy: How well do the relative abundances in your results match the known proportions? Significant skewing may indicate PCR bias or issues with DNA extraction efficiency.

- Use these results to optimize bioinformatics parameters and identify potential biases in your wet-lab methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Contamination Control

| Item | Function | Example/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Decontamination Solution | To destroy contaminating DNA on surfaces and equipment. | Sodium hypochlorite (bleach), DNA-ExitusPlus, DNA-Zap [1]. |

| Sterile, DNA-Free Consumables | To collect and store samples without introducing contaminants. | Pre-sterilized swabs, filter units, and collection tubes (e.g., from ThermoFisher, Qiagen) [1]. |

| Certified DNA-Free Water | For use as a process negative control and for preparing molecular biology reagents. | Molecular Biology Grade Water (e.g., from Invitrogen, Qiagen) [3]. |

| Commercial Mock Community | To serve as a positive control for validating the entire workflow from DNA extraction to sequencing and bioinformatics. | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard, ATCC MSA-1000 [15]. |

| UV PCR Workstation | To provide a sterile environment for setting up PCR reactions, preventing cross-contamination between samples and from ambient air. | Laminar flow cabinets with UV light. |

| Decontamination Software | To statistically identify and remove contaminating sequences from microbiome data post-sequencing. | R packages: decontam, micRoclean, SCRuB [19]. |

Experimental Workflow for Control Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for incorporating both negative and positive controls throughout a microbiome study, from design to data interpretation.

In microbiome research, particularly in low-biomass studies, contaminating DNA from laboratory reagents and kits—collectively known as the "kitome"—poses a significant challenge for accurate result interpretation. These contaminants can originate from DNA extraction kits, library preparation reagents, and even molecular-grade water, potentially leading to false-positive results and erroneous conclusions. This technical support center provides comprehensive troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers identify, prevent, and correct for kitome and reagent contamination in their experiments.

FAQ: Understanding Kitome Contamination

What is "kitome" contamination and why is it problematic for microbiome studies?

Kitome contamination refers to the microbial DNA present in laboratory reagents and consumables used for DNA extraction and library preparation [5]. This is particularly problematic for low-biomass samples (such as human tissues, blood, or environmental samples with minimal microbial content) because the contaminant DNA can constitute a substantial proportion of the final sequencing data, potentially leading to incorrect taxonomic assignments and false discoveries [1]. Studies have shown distinct background microbiota profiles between different reagent brands, with some containing common pathogenic species that could significantly affect clinical interpretation [5].

How much variability exists in contamination between different reagent lots?

Significant lot-to-lot variability has been documented in commercial DNA extraction reagents [5]. Research has demonstrated that background contamination patterns vary substantially between different manufacturing lots of the same brand, emphasizing the importance of lot-specific microbiota profiling rather than assuming consistency within a product line [5]. This variability necessitates that researchers characterize negative controls for each new reagent lot they receive.

What types of contaminants are commonly found in sequencing reagents?

Common contaminants include bacterial DNA from taxa that persist in manufacturing environments, such as Comamonadaceae, Burkholderiaceae, and Pseudomonadaceae [5]. These microorganisms can survive in low-nutrient conditions and resist standard sterilization procedures. The specific contaminant profile depends on the reagent type, brand, and manufacturing lot.

Is there a consistent blood microbiome in healthy individuals?

Recent evidence suggests there is no consistent core microbiome endogenous to human blood [5]. Analysis of blood samples from healthy individuals showed no detectable microbial species in 84% of subjects, with the remainder having only transient and sporadic microbial presence, likely representing translocation of commensals from other body sites rather than a resident blood microbiome [5]. This finding reinforces the importance of using extraction blanks as negative controls in clinical metagenomic testing of sterile liquid biopsy samples.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Addressing Contamination

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background microbiota in low-biomass samples | Contaminating DNA in extraction reagents or kits | Include extraction blanks with molecular-grade water as input; use computational decontamination tools like Decontam [5] |

| Lot-to-lot variability in background signal | Differences in manufacturing processes between reagent lots | Perform lot-specific microbiota profiling; request contamination profiles from manufacturers [5] |

| Adapter dimers in final library | Excess adapters ligating together during library prep | Perform additional clean-up steps; optimize size selection procedures; use electrophoresis to detect dimers [28] [29] |

| False-positive pathogen detection | Reagents containing DNA from pathogenic species | Maintain database of reagent-specific contaminant profiles; validate findings with independent methods [5] |

| Cross-contamination between samples | Well-to-well leakage or aerosol contamination during processing | Use physical barriers between samples; include negative controls throughout workflow; consider automated extraction [1] |

| DNA carryover from previous experiments | Contaminated laboratory equipment or surfaces | Implement strict cleaning protocols with DNA removal solutions; use UV irradiation [1] |

Table 2: Quality Control Checkpoints in NGS Library Preparation

| Checkpoint | Parameters to Assess | Recommended Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Material | Quantity, purity, integrity | Fluorometric quantification (Qubit), spectrophotometry (A260/A280), electrophoresis [28] |

| Fragmentation | Fragment size distribution | Electrophoresis (Bioanalyzer, TapeStation) [28] [30] |

| Adapter Ligation | Ligation efficiency, adapter dimer formation | Electrophoresis, qPCR [28] [30] |

| Amplified Library | Library complexity, amplification bias | Fluorometry, qPCR, electrophoresis [28] |

| Final Pooled Library | Molar concentration, adapter dimer presence | qPCR, electrophoresis [28] [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Control

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Negative Control Strategy

- Extraction Blanks: Process molecular-grade water alongside samples using the same DNA extraction kit [5]

- Library Preparation Controls: Include negative controls during library preparation steps

- Sampling Controls: Collect and process controls from potential contamination sources (empty collection vessels, air swabs) [1]

- Processing: Subject all controls to the exact same procedures as experimental samples

- Sequencing: Sequence controls in the same run as experimental samples to account for run-specific contaminants

Protocol 2: Reagent Contamination Profiling

- Test New Reagent Lots: Before processing valuable samples, characterize the contamination profile of new reagent lots

- Multiple Replicates: Process at least three replicates of extraction blanks for each reagent lot [5]

- Sequencing Depth: Sequence negative controls to sufficient depth to detect low-abundance contaminants

- Documentation: Maintain a laboratory-specific database of contaminant profiles for each reagent lot

- Quality Threshold: Establish maximum acceptable contamination levels for different sample types

Contamination Control Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for preventing and identifying contamination throughout the DNA extraction and library preparation process:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular-grade Water | Negative control input for extraction blanks | Use 0.1µm filtered, DNA-free certified; test different lots [5] |

| ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control | Positive control for extraction efficiency | Consists of Imtechella halotolerans and Allobacillus halotolerans; distinguishes true signal from contamination [5] |

| DNA Removal Solutions | Surface decontamination | Sodium hypochlorite (bleach), commercial DNA degradation solutions [1] |

| Automated Electrophoresis | Library QC and adapter dimer detection | Bioanalyzer, TapeStation systems; identify adapter dimers at ~70-90bp [28] [29] |

| Computational Decontamination Tools | Bioinformatics contamination removal | Decontam, microDecon, SourceTracker; use frequency or prevalence-based methods [5] |

| UV Sterilization Cabinet | Equipment decontamination | Effective for destroying contaminating DNA on surfaces [1] |

Effective management of kitome and reagent contamination requires a multifaceted approach spanning experimental design, wet-lab practices, and computational analysis. By implementing the systematic contamination control strategies outlined in this guide—including comprehensive negative controls, reagent lot testing, and appropriate bioinformatic corrections—researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their microbiome studies, particularly when working with low-biomass samples.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Contamination Control

What are the most critical points for contamination control in low-biomass microbiome studies?

Contamination control is paramount in low-biomass microbiome studies (e.g., certain human tissues, atmosphere, treated drinking water) because the target microbial DNA signal can be easily overwhelmed by contaminant "noise" [1]. Key control points include:

- Sample Collection: Use single-use, DNA-free consumables and decontaminate all equipment and surfaces with solutions like 80% ethanol followed by a nucleic acid degrading agent (e.g., bleach) [1] [31].

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Researchers should wear appropriate PPE (gloves, masks, cleansuits) to minimize the introduction of human-derived contaminants [1].

- Laboratory Workflow: Establish a unidirectional workflow from pre- to post-PCR areas, use dedicated equipment, and perform work within a biological safety cabinet [31].

- Comprehensive Controls: Always include multiple types of negative controls (e.g., sampling blanks, extraction blanks, no-template PCR controls) processed alongside your samples to identify contaminant sources [1] [32] [31].

How can I prevent cross-contamination between samples during nucleic acid extraction in a high-throughput setting?

The prevalent use of 96-well plates for extractions poses a significant risk of well-to-well contamination due to shared seals and minimal separation between wells [33] [25]. To mitigate this:

- Alternative Methods: Consider using single-tube systems, such as the Matrix Method which employs barcoded individual tubes, to significantly reduce well-to-well contamination compared to conventional 96-well plates [33] [25].

- Plate Handling: If using plates, avoid processing samples with vastly different microbial biomasses next to each other. Randomize sample locations across plates and be mindful of seal removal direction, as contamination often patterns correlate with technician handedness [33] [25].

- Regular Decontamination: Regularly clean and decontaminate laboratory equipment, including pipettes, which can be a source of aerosol contamination [34].

What are the best practices for managing reagents and consumables to minimize contamination?

Reagents, kits, and plastic consumables are common sources of contaminant DNA [1] [32].

- Source Selection: Purchase reagents certified to be DNA-free whenever possible.

- Quality Control: Test reagents beforehand using qPCR or sequencing to assess their inherent contamination profile [31].

- Handling and Storage: Aliquot bulk reagents into smaller, single-use volumes to reduce repeated exposure and contamination risk. Pre-treat plasticware and glassware with UV-C irradiation or autoclaving before use [1] [31].

My negative controls show contamination after PCR/sequencing. What should I do?

Contamination in negative controls indicates that contaminant DNA was introduced during the experimental process.

- Investigate the Source: Review your process to identify where the contamination was introduced. Check reagent lots, equipment cleanliness, and technique.

- Re-process if Necessary: If the level of contamination is high and would significantly impact your sample results, the experiment may need to be repeated with fresh reagents and stricter contamination controls.

- Bioinformatic Removal: In some cases, contaminants identified in the negative controls can be removed bioinformatically from the sample data. However, this is a corrective measure, and proactive prevention is always preferable [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Consistent Low-Level Contamination Across Many Samples

| Potential Cause | Recommended Action | Preventive Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Contaminated reagents or kits [32] | Test all new reagent lots with a negative control (e.g., water) before using on precious samples. | Switch to a different brand of kit or use reagents certified as DNA-free. |

| Contaminated laboratory environment or equipment [35] | Decontaminate workspaces, biosafety cabinets, and equipment with DNA-degrading solutions (e.g., 10% bleach) and UV irradiation [31]. | Implement regular, scheduled cleaning and decontamination of all shared equipment and workspaces. |

| Improper technician technique [36] | Re-train staff on proper aseptic technique, including the use of filter tips and careful handling to avoid aerosol generation [34]. | Use appropriate PPE and maintain a unidirectional workflow from "clean" to "dirty" areas. |

Problem: Well-to-Well Contamination in 96-Well Plates

| Observation | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Contamination follows a specific pattern on the plate (e.g., along one side) [25]. | Liquid splash or aerosol transfer during seal removal or plate handling. | Change the orientation or direction of seal removal. Use plates with greater well separation or switch to a single-tube system like the Matrix Method [33] [25]. |

| High contamination in blanks adjacent to high-biomass samples. | Cross-contamination from samples with high microbial biomass. | Avoid placing high- and low-biomass samples adjacent to each other. Randomize sample placement across the plate [33]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Contamination Sporadic and Unpredictable

| Step to Investigate | Checklist |

|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Was PPE worn and changed between samples? Were sampling devices sterile and single-use? [1] |

| Reagents & Consumables | Were new, single-use aliquots of reagents used? Were tubes/plates UV-irradiated before use? [31] |

| Controls | Were the appropriate negative controls (field, extraction, PCR) included and did they also show sporadic contamination? |

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Mitigation

Detailed Protocol: The Matrix Method for High-Throughput Processing

This protocol is designed to minimize well-to-well contamination during sample accession and nucleic acid extraction [33] [25].

1. Principle: To use individual barcoded tubes for sample collection and processing, thereby eliminating the shared-seal design of 96-well plates that leads to cross-contamination.

2. Materials:

- Barcoded Matrix Tubes (e.g., Thermo Fisher, #3741)

- 95% (vol/vol) ethanol

- MagMAX Microbiome Ultra Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (or similar, omitting the lysis bead plate)

- Centrifuge and vortexer

- Multichannel pipette

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Sample Accession. Transfer samples directly into pre-barcoded Matrix Tubes.

- Step 2: Stabilization and Metabolite Extraction. Add 95% ethanol to the tubes to stabilize the microbial community and act as a solvent for metabolites. Shake the samples.

- Step 3: Phase Separation. Centrifuge the tubes to separate the mixture.