Conquering Contamination: A Comprehensive Guide to Addressing Low Microbial Biomass in NGS Samples

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of low microbial biomass samples presents a significant challenge in biomedical research, where contaminating DNA can critically distort results and lead to spurious conclusions.

Conquering Contamination: A Comprehensive Guide to Addressing Low Microbial Biomass in NGS Samples

Abstract

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of low microbial biomass samples presents a significant challenge in biomedical research, where contaminating DNA can critically distort results and lead to spurious conclusions. This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a current and exhaustive framework for navigating these challenges. We first explore the foundational principles defining low-biomass environments and their unique vulnerabilities. The guide then details state-of-the-art methodological approaches, from sample collection to host DNA depletion, followed by a thorough troubleshooting and optimization section for mitigating contamination. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of validation strategies and sequencing technologies, offering a clear pathway for ensuring data integrity and advancing reliable microbiome science in clinical and research settings.

The Low-Biomass Challenge: Defining the Problem and Its Critical Impact on NGS Data

What Constitutes a Low Microbial Biomass Environment? Key Examples from Clinical and Environmental Settings

Definition and Key Challenges

A low microbial biomass environment contains minimal levels of microorganisms, approaching the limits of detection for standard DNA-based sequencing methods. In these settings, the target microbial DNA "signal" can be dwarfed by contaminating "noise," making studies particularly challenging [1].

The primary challenge is the proportional impact of contamination. Even small amounts of external microbial DNA can drastically skew results and lead to incorrect conclusions. This is a critical concern in fields from clinical diagnostics to environmental science [1].

Table: Key Challenges in Low Microbial Biomass Research

| Challenge | Impact on Research | Common Sources |

|---|---|---|

| High Contaminant-to-Signal Ratio | Contaminant DNA can overwhelm the true microbial signal, leading to spurious findings [1]. | Human operators, laboratory reagents ("kitome"), sampling equipment, cross-contamination between samples [1] [2]. |

| Interference from Host DNA | In host-associated samples, over 95% of sequenced DNA can be host-derived, vastly reducing sequencing efficiency for the target microbiome [3]. | Host cells in clinical samples (e.g., milk, blood) [3]. |

| Presence of "Relic DNA" | DNA from dead or damaged cells can be detected, providing an inaccurate picture of the living, active microbial community [4]. | Dead microbial cells in the sample [4]. |

Key Examples of Low Microbial Biomass Environments

Low microbial biomass environments are found in diverse clinical and environmental settings. The table below summarizes key examples identified from the literature.

Table: Examples of Low Microbial Biomass Environments

| Environment | Specific Examples | Key Characteristics / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical & Host-Associated | Human tissues & fluids: Fetal tissues, meconium, blood, respiratory tract, breast milk [1] [3]. | Despite often having high host DNA, microbial load is very low. The existence of a resident microbiome in some tissues (e.g., placenta) is debated due to contamination concerns [1]. |

| Human saliva | While often considered high-biomass, live microbial load can fluctuate by orders of magnitude and the percentage of living cells can range from nearly 0% to 100% [4]. | |

| Indoor & Built Environments | Cleanrooms (e.g., NASA spacecraft assembly facilities), hospital operating rooms [2]. | Surfaces are intentionally kept ultra-clean, resulting in ultra-low biomass [2]. |

| Indoor air / Bioaerosols | Air is a low-biomass environment compared to soil or water; human emission is a primary source [5]. | |

| Natural Environments | Atmosphere, hyper-arid soils, dry permafrost, deep subsurface, ice cores, treated drinking water [1]. | Conditions are often extreme (e.g., low water availability, nutrient scarcity), limiting microbial life [1]. |

| Laboratory-Created | Mock microbial communities | Artificially assembled communities used for method validation and optimization [6]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: General Workflow for Low-Biomass Studies

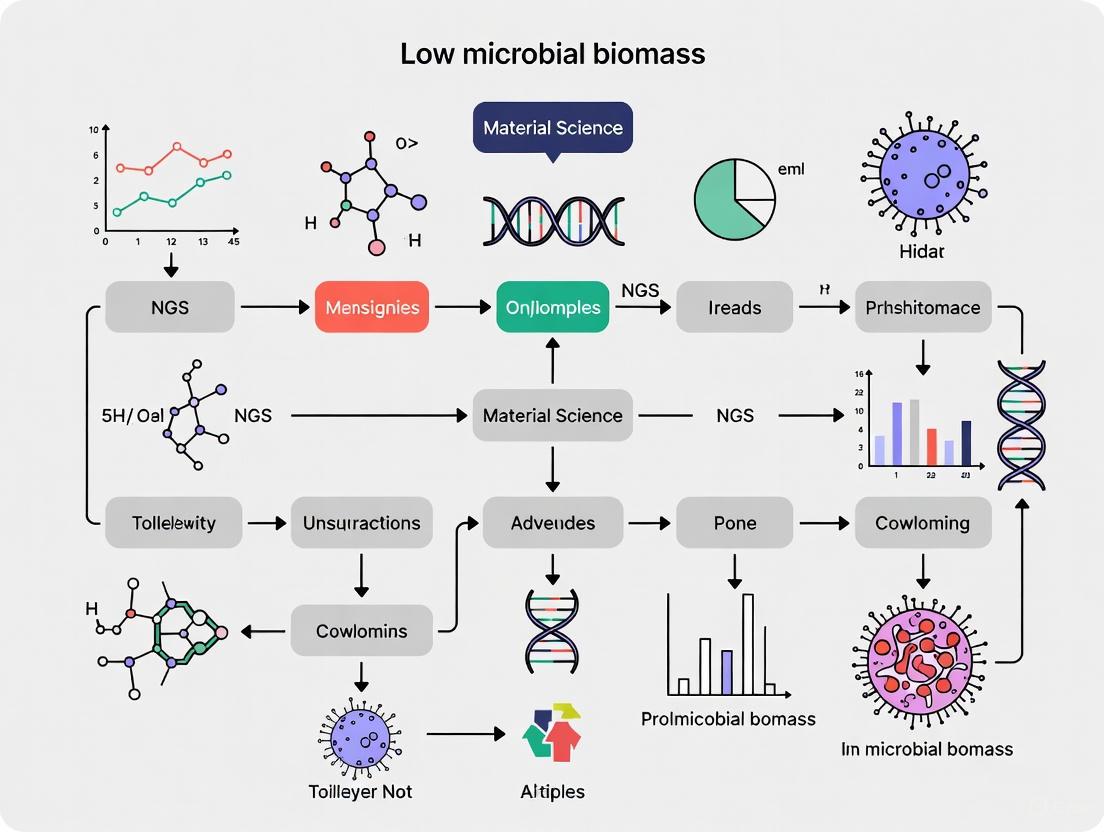

The following diagram outlines the core considerations for a robust low-biomass study, from sampling to data analysis.

A. Sample Collection and Handling

- Decontaminate Equipment: Surfaces and tools should be decontaminated with 80% ethanol followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution (e.g., bleach, UV-C light) to remove both viable cells and residual DNA [1].

- Use Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Operators should wear gloves, masks, and cleansuits to minimize contamination from skin, hair, or aerosols [1].

- Incorporate Rigorous Controls: Collect multiple negative controls, such as:

B. Laboratory Processing to Enhance Microbial Signal

- Host DNA Depletion: For samples with high host DNA, like milk, use commercial kits (e.g., MolYsis complete5) to enzymatically degrade host cells before DNA extraction. One study increased the percentage of microbial reads from ~9% to ~38% in milk samples using this technique [3].

- Removal of "Relic DNA" with PMA: To profile only living microbes, treat samples with propidium monoazide (PMA) before DNA extraction. PMA penetrates only membrane-compromised (dead) cells and covalently binds their DNA, preventing its amplification. This is crucial in samples like saliva where the percentage of live cells can be highly variable [4].

Protocol 2: Rapid Nanopore Sequencing for Ultra-Low Biomass Surfaces

This protocol is adapted from cleanroom studies for situations requiring rapid on-site results [2].

- Sample Collection: Use a high-efficiency sampler like the Squeegee-Aspirator for Large Sampling Areas (SALSA) to collect microbes from a large surface area (e.g., 1 m²) into a sterile tube.

- Concentration: Concentrate the collected liquid sample (e.g., using an InnovaPrep CP-150 concentrator with a hollow fiber tip) to a low elution volume (e.g., 150 µL).

- DNA Extraction and Modified Library Prep: Extract DNA and use a modified version of Oxford Nanopore's Rapid PCR Barcoding kit, potentially adding carrier DNA or increasing PCR cycles to enable sequencing from ultra-low inputs (<10 pg).

- Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence on a portable nanopore device (e.g., MinION). During bioinformatic analysis, critically compare results from the sample against all negative control sequences to filter contaminants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Kits for Low-Biomass Research

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MolYsis complete5 Kit | Selective lysis of human/animal cells and degradation of the released DNA [3]. | Host-associated samples (e.g., milk, tissue) to increase the proportion of microbial reads in shotgun metagenomics [3]. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | Dye that selectively binds DNA in dead cells with compromised membranes, blocking its PCR amplification [4]. | Distinguishing viable vs. non-viable microbial communities in samples like saliva, sputum, or environmental surfaces [4]. |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit | Depletes host DNA background to enrich for microbial DNA [7]. | Shotgun metagenomic sequencing of host-associated samples where host DNA dominates [7]. |

| Zymo Quick-16S Kit | Standardized kit for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing to minimize inter-study variability [7]. | Targeted community profiling for labs seeking a standardized, commercial solution [7]. |

| RiboFree rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from total RNA samples [7]. | Metatranscriptomic studies to increase the sequencing coverage of messenger RNA (mRNA) and improve the view of functional activity [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My negative controls show microbial growth. Are my samples useless?

Not necessarily. The purpose of controls is to identify contaminants. If the contaminant signal in your controls is significantly lower than in your samples, you can use bioinformatic tools (e.g., decontam) to subtract background noise. However, if signals in samples are indistinguishable from controls, the data cannot be trusted [1] [2]. Reporting the results of all controls is mandatory.

Q2: When should I use 16S rRNA sequencing vs. shotgun metagenomics for low-biomass samples?

- 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing: More targeted and often more sensitive for detecting low-abundance taxa because it focuses on a single gene. However, it is highly susceptible to contamination from reagents and cannot reliably distinguish living from dead cells without PMA treatment [4] [7].

- Shotgun Metagenomics: Provides a broader picture of community function and taxonomy but is more expensive. The high proportion of host or contaminant DNA can make it inefficient. It is best used after host DNA depletion [3] [7]. The choice depends on your research question and available budget.

Q3: What is the single most important practice for low-biomass research? The consistent and extensive use of negative controls throughout the entire workflow—from sample collection to sequencing. This is non-negotiable for identifying contamination sources and correctly interpreting your data [1] [2].

Q4: How can I tell if a published study on a low-biomass environment is reliable? Look for evidence of rigorous contamination control. A reliable study should explicitly mention:

- The types and number of negative controls used.

- Steps taken during sampling and DNA extraction to minimize contamination (e.g., use of PPE, DNA-free reagents).

- How contaminant sequences were handled bioinformatically. Studies that fail to report these details should be treated with skepticism [1].

FAQs: Understanding the Core Challenge

What is a "low-biomass" sample, and why is it particularly vulnerable? A low-microbial-biomass environment contains minimal microbial cells, making target DNA a small component of the total genetic material analyzed. Examples include certain human tissues (respiratory tract, blood, placenta), treated drinking water, hyper-arid soils, and the deep subsurface [1]. In these samples, the actual microbial signal is exceptionally faint. Consequently, even tiny amounts of contaminating DNA from reagents, kits, or the laboratory environment can constitute a large proportion—sometimes over 80%—of the final sequencing data, overwhelming the true biological signal [8] [1].

What are the primary sources of contamination in these studies? Contamination can be categorized as follows:

- External Contamination: DNA originating from outside the sample. Key sources include DNA extraction kits and laboratory reagents (often called the "kitome"), sampling equipment, personnel, and the laboratory environment itself [9] [10] [1].

- Internal Contamination (Cross-Contamination): This involves the transfer of DNA between samples processed concurrently, also known as well-to-well leakage or the "splashome" [11] [1]. This can occur during DNA extraction or library preparation on multi-well plates.

- Host DNA Misclassification: In metagenomic studies of host-associated samples (e.g., tumor tissue), the vast majority of sequenced DNA is from the host. If not properly accounted for, this host DNA can be misclassified as microbial during bioinformatic analysis, generating noise and potential false signals [11].

How can I tell if my dataset is affected by contamination? Several analytical indicators suggest contamination is impacting your results:

- Inflated Diversity: The presence of an unexpectedly high number of microbial taxa, especially those not typically associated with the sampled environment [8].

- Unexpected Taxa: Detection of common laboratory contaminants (e.g., Delftia acidovorans, Achromobacter xylosoxidans) or taxa typically found in other body sites or environments in high abundance [12] [13].

- Inverse Correlation with Biomass: A strong inverse relationship between the abundance of certain taxa and the total microbial DNA concentration in the sample is a key indicator of contaminant behavior [13].

Troubleshooting Guides: From Collection to Computation

Guide 1: Designing a Contamination-Aware Study

A robust experimental design is the first and most critical line of defense.

- Avoid Batch Confounding: Ensure your groups of interest (e.g., case vs. control) are distributed across all processing batches (DNA extraction, library prep, sequencing runs). Do not process all samples from one group in a single batch, as any batch-specific contamination or bias will be indistinguishable from a true biological signal [11].

- Incorporate Comprehensive Controls: It is essential to include various control samples to profile contaminating DNA. The table below outlines key control types [1] [11].

| Control Type | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Extraction Control | An empty tube or tube with molecular-grade water taken through the DNA extraction process. | Identifies contaminants from extraction kits and reagents [10] [1]. |

| Sampling/Field Control | A swab exposed to the air during sampling, or an aliquot of preservation solution. | Identifies contaminants introduced during the sample collection process [1]. |

| Library Preparation Control | A no-template control taken through the library preparation process. | Identifies contaminants from library prep kits and enzymes [11]. |

| Mock Microbial Community | A defined mix of known microorganisms. | Serves as a positive control to evaluate the fidelity of your entire workflow, including the extent of contamination and cross-contamination [8]. |

- Minimize Well-to-Well Leakage: When using 96-well plates, avoid placing high-biomass samples (like stool) adjacent to low-biomass samples. Include blank wells between samples if possible, and use liquid handling robots with care to prevent splashing [11].

Guide 2: Wet-Lab Best Practices to Minimize Contamination

Implement strict laboratory protocols to reduce the introduction of contaminants.

- Decontaminate Equipment: Use single-use, DNA-free consumables where possible. Reusable equipment should be decontaminated with 80% ethanol (to kill cells) followed by a DNA-degrading solution (e.g., dilute bleach or UV-C irradiation) to remove residual DNA [1].

- Use Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear gloves, lab coats, and, for very low-biomass samples, masks and hair nets to reduce contamination from personnel [1].

- Use Ultraclean Reagents: Select molecular biology reagents that are certified DNA-free. Be aware that contaminants can vary significantly between different brands and even between different lots of the same brand of DNA extraction kits [9].

- Optimize PCR Cycles: In library preparation, avoid excessive PCR cycles, as over-amplification can exacerbate the detection of contaminating DNA and create artifacts. Use tools like the iconPCR to dynamically adjust cycles based on input DNA [14].

Guide 3: Computational Decontamination Strategies

After sequencing, computational tools are essential to identify and remove contaminant sequences.

- Tool Selection: Several tools are available, each with different strengths and requirements.

- Implementation: The following workflow outlines a general approach to computational decontamination, integrating common tools and steps.

The table below compares some commonly used computational tools.

| Tool | Method | Key Requirement | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decontam [8] [13] | Frequency-based (inverse correlation with DNA concentration) and/or prevalence-based (more common in controls). | DNA concentration metrics and/or negative control samples. | Standardized workflows where negative controls are available. |

| Squeegee [12] | De novo; identifies taxa shared across samples from distinct ecological niches processed in the same lab/kit. | Multiple samples from different environments (e.g., different body sites). | When negative controls are unavailable for a dataset. |

| SourceTracker [8] | Bayesian approach to estimate the proportion of a sample that comes from a "contaminant source". | Pre-defined "source" environments (like your negative controls) and "sink" (experimental) samples. | When you have well-characterized contamination sources. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Degrading Reagents (e.g., dilute bleach, DNA-ExitusPlus) | To remove contaminating DNA from surfaces and reusable equipment [1]. | Critical for pre-treating work surfaces and non-disposable tools. |

| Molecular Grade Water | Used in blank controls and to prepare solutions. | Must be certified DNA-free. Filtering through a 0.1 µm filter is recommended [9]. |

| DNA/RNA Spike-in Controls (e.g., ERCC, ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in) | Added to the sample to quantitatively monitor extraction efficiency, sequencing depth, and for contaminant quantification [13]. | Allows for precise quantification of contaminant mass and helps establish a minimum usable input mass. |

| Mock Microbial Communities | Defined mixes of known microorganisms from a recognized supplier (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS, ATCC). | Serves as an essential positive control to benchmark your entire workflow and evaluate the success of decontamination [8]. |

| Ultraclean DNA Extraction Kits | Kits designed for low-biomass inputs, often with protocols to minimize reagent contamination. | Request background contamination profiles from the manufacturer for each specific lot [9]. |

In next-generation sequencing (NGS), particularly for low microbial biomass samples, contamination is not a mere inconvenience—it is a critical failure point that can compromise the entire study. Low-biomass samples, which include certain human tissues, atmospheric samples, and treated drinking water, are especially vulnerable because the contaminant DNA can dramatically outweigh the target signal, leading to spurious results [1]. This guide identifies the major sources of contamination and provides actionable protocols to mitigate them, ensuring the integrity of your sequencing data.

FAQ: Identifying and Troubleshooting Contamination

FAQ 1: My NGS results show high levels of unexpected microbial reads. What are the most likely sources?

Unexpected microbial reads often originate from contamination introduced at various stages of the workflow. The following table outlines the primary sources and their identifying signatures.

Table 1: Major Contamination Sources and Their Identifiers

| Contamination Source | Common Contaminants | Typical Failure Signals in NGS Data |

|---|---|---|

| Reagents & Kits | Bacteria from ultrapure water systems (e.g., Bradyrhizobium), kit-derived DNA [15] | Detection of specific contaminant genera (e.g., Bradyrhizobium) across multiple unrelated samples; background in negative controls [15] |

| Sampling Equipment | Microbes from non-sterile containers, swabs, or fluids [1] | Microbiome profile reflects skin flora or environmental microbes; tracers from drilling fluids appear in samples [1] |

| Laboratory Environment | Airborne fungal spores (e.g., Aspergillus), settled dust, aerosol droplets from talking/coughing [16] [1] | Detection of fungal spores or skin bacteria in samples; inconsistencies correlated with sampling location or operator [16] |

| Human Operators | Human skin cells, hair, and saliva [1] | Significant human DNA in samples; microbial profile dominated by human skin flora [1] |

FAQ 2: My negative controls are positive for adapter dimers. What went wrong during library prep and how can I fix it?

A sharp peak at ~70-90 bp in your Bioanalyzer electropherogram indicates adapter dimers, a common ligation failure. The root cause is often an inefficient cleanup step following adapter ligation.

- Root Cause: Incomplete removal of excess free adapters after the ligation reaction due to an incorrect bead-to-sample ratio or overly aggressive purification leading to sample loss [17].

- Corrective Action:

- Re-optimize cleanup: Use solid phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) magnetic bead technology. Precisely calibrate the bead-to-sample ratio to ensure efficient binding of the target fragments and removal of small adapter artifacts [18] [19]. For example, the NucleoMag NGS Clean-up and Size Select kit allows for tailored size selection with high recovery rates of ≥80% [19].

- Re-purify: If adapter dimers are present, re-purify the library using a double-sided size selection protocol to exclude the small dimer peaks [17] [19].

- Verify quantification: Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) over UV absorbance for accurate quantification of usable library material, as absorbance can overestimate concentration by counting adapter artifacts [17].

FAQ 3: I am observing cross-contamination between samples in a high-throughput run. How can this be prevented?

Cross-contamination, or the transfer of DNA between samples, significantly increases false-positive variant calls and distorts heteroplasmy measurements in mtDNA sequencing [20].

- Root Cause: Well-to-well leakage during liquid handling, aerosol generation during pipetting, or using the same equipment for multiple samples without proper decontamination [1].

- Corrective Action:

- Adopt a double-barcode strategy: Implement a unique dual-indexing (UDI) approach. A study demonstrated that while a single barcode led to cross-contamination levels of up to 17.7%, a double barcode-based strategy effectively eliminated it [20].

- Automate sample preparation: Integrated automated liquid handlers minimize human handling errors and provide a closed system, substantially reducing the risk of cross-contamination and improving reproducibility [21].

- Enforce rigorous decontamination: For manual workflows, decontaminate surfaces and equipment with 80% ethanol followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution (e.g., dilute bleach) to remove viable cells and trace DNA [1].

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Control

Protocol for Low-Biomass Sample Collection

This protocol is designed to minimize contamination during the initial sampling of low-biomass environments [1].

- Step 1: Decontaminate all equipment. Use single-use, DNA-free collection vessels where possible. Reusable equipment must be decontaminated with 80% ethanol to kill organisms, followed by a DNA-removal solution (e.g., 1-3% sodium hypochlorite) to destroy residual DNA. Note that autoclaving kills cells but does not fully remove persistent DNA [1].

- Step 2: Use appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). Operators must wear gloves, masks, clean suits, and hair covers. Gloves should be decontaminated with ethanol and nucleic acid removal solution before handling the sample and changed frequently [1].

- Step 3: Collect comprehensive negative controls. Essential controls include [1]:

- An empty collection vessel.

- A swab exposed to the air in the sampling environment.

- An aliquot of the preservation solution used.

- Swabs of the PPE or sampling surfaces.

- Step 4: Minimize sample handling. Samples should not be exposed to the environment more than necessary and should be transferred to sterile containers and sealed immediately.

Protocol for Routine Laboratory Cleaning and Equipment Maintenance

Preventing contamination requires consistent cleaning of the laboratory environment and instrumentation [22] [1].

- Step 1: Clean NGS wash cartridges. After each sequencing run, wash cartridges should be thoroughly rinsed with warm water. If mold or discoloration is observed, clean the wells with a 1-3% bleach solution and a brush, followed by at least three rinses with deionized water to prevent residual bleach from causing clustering issues. The cartridge should be air-dried upside down [22].

- Step 2: Decontaminate work surfaces. Before and after NGS library preparation, clean benches and equipment with 80% ethanol followed by a DNA degradation solution. UV-C irradiation of hoods and surfaces can also be used to sterilize the area [1].

- Step 3: Validate air handling systems. Periodically monitor air handling systems (e.g., HEPA filters) to ensure they meet performance specifications and do not become a source of particulate or microbial contamination [16].

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points for managing contamination risks throughout the NGS workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials crucial for effective contamination control in NGS workflows for low-biomass research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Product/Technology | Primary Function | Key Application in Contamination Control |

|---|---|---|

| SPRI Magnetic Beads (e.g., MagMAX Pure Bind [18], NucleoMag NGS Clean-up [19]) | DNA cleanup and size selection | Precisely removes adapter dimers and other unwanted small fragments after enzymatic reactions; enables high-recovery, reproducible purification. |

| Double Barcode Kits (Unique Dual Indexes) [20] | Sample multiplexing and identification | Computational demultiplexing effectively identifies and eliminates sequence reads resulting from cross-contamination between samples. |

| DNA Removal Solutions (e.g., 1-3% Sodium Hypochlorite) [22] [1] | Surface and equipment decontamination | Degrades persistent trace DNA on work surfaces, tools, and reusable labware that ethanol and autoclaving cannot remove. |

| Automated Liquid Handling Systems (e.g., Dispendix I.DOT, KingFisher Systems) [18] [21] | Library preparation and purification | Minimizes human error and variation, reduces aerosol-based cross-contamination, and ensures high reproducibility in high-throughput workflows. |

The Critical Challenge of Contamination in Low Biomass NGS

In low microbial biomass research, where the target microbial signal is very faint, even minute levels of contamination can lead to catastrophic misinterpretations. Contaminating DNA, which can originate from reagents, laboratory environments, or sample cross-contamination, becomes a significant portion of the sequenced material, potentially masquerading as genuine biological signal [23]. This is particularly problematic in studies of low-biomass environments like certain human tissues (e.g., placenta, blood, brain), atmospheric samples, and ultra-dry soils [23]. The consequences are severe: false positives can lead to erroneous claims about microbial communities associated with diseases, while false negatives can obscure true pathogenic signals. For instance, controversies surrounding the existence of a "placental microbiome" have been largely attributed to inadequate contamination controls, highlighting how false discoveries can misdirect entire research fields [23]. In a clinical context, this can translate to misdiagnosis, inappropriate treatment, and ultimately, patient harm.

FAQs: Addressing Key Researcher Concerns

Q1: How can I determine if my low-biomass NGS data is compromised by contamination? A: Several indicators suggest contamination:

- High Abundance of Common Contaminants: Unexpectedly high proportions of taxa commonly found in reagents or laboratory environments (e.g., Pseudomonas, Ralstonia) are a major red flag [23].

- Negative Control Correlation: If the microbial profile of your experimental samples closely resembles that of your negative controls (e.g., extraction blanks), contamination is likely dominant [23].

- Inconsistent Biological Replicates: High variability between technical or biological replicates from the same source can indicate stochastic contamination.

- Unexpected Taxonomic Profiles: Findings that contradict established biological knowledge (e.g., aerobic bacteria in anoxic environments) should be treated with suspicion.

Q2: What is the minimum number of negative controls needed per experiment? A: While the ideal number can vary, a robust guideline is to include at least one negative control for every four to six experimental samples throughout the entire workflow, from sample collection to sequencing [23]. These controls must be processed simultaneously and identically to the actual samples.

Q3: Can bioinformatics tools completely remove contamination after sequencing? A: No. Bioinformatics decontamination methods are useful but have limitations. They can help identify and subtract signals associated with common contaminants, but they cannot reliably distinguish contaminant DNA from genuine, low-abundance native DNA in heavily contaminated samples [23]. The primary strategy must be proactive prevention during the experimental workflow.

Q4: How does sample cross-contamination specifically lead to misinformed clinical interpretations? A: In clinical NGS, especially for applications like cancer screening using liquid biopsy, tumor-derived DNA in blood can be present at very low levels (<0.1%) [24]. Cross-contamination from a sample with a high viral load or a high tumor burden can introduce false-positive signals into a negative sample. This could lead to a false cancer diagnosis, incorrect pathogen identification, or unnecessary and invasive follow-up testing for a patient [24] [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving High Contamination in Negative Controls

Problem: Negative controls (e.g., water blanks) show high DNA concentrations or diverse microbial communities upon sequencing.

Investigation and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Interpretation & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify Contaminants | Taxonomically classify the sequences in the control. | If common lab/environmental genera (e.g., Pseudomonas, Ralstonia) are found, the source is likely reagents or the lab environment [23]. |

| 2. Trace the Source | Compare the contaminant profile to your experimental samples and records of reagent lots. | A batch-specific pattern points to a contaminated reagent. A persistent lab-wide pattern points to the environment or shared equipment [23]. |

| 3. Implement Solutions | - Use new, certified DNA-free reagent lots.- Decontaminate workspaces with UV irradiation and DNA-degrading solutions.- Use dedicated, filtered pipette tips and consumables [23]. |

Guide 2: Addressing Suspected Sample Cross-Contamination

Problem: Unexpected genetic variants or sample mix-ups are detected, which is critical for clinical reproducibility.

Investigation and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Interpretation & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Confirm Sample Identity | Check for discrepancies between expected and observed sample gender or known genotypes. | This is a fundamental溯源质控 (traceability QC) step to catch sample swaps [26]. |

| 2. Use Specialized Detection | Employ a bioinformatic method to detect cross-sample contamination. For example, analyze allele frequency patterns at selected Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) sites [27] [24]. | Methods exist that can detect contamination levels as low as 0.005% by analyzing SNPs with specific properties (e.g., population frequency between 0.3-0.7, A/T mutations) [24]. |

| 3. Improve Wet-Lab Practices | - Strictly limit sample tube opening times.- Use physical barriers between samples.- Decontamate lab surfaces and equipment frequently between sample handlings [23] [28]. |

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Control

Protocol 1: A Comprehensive Workflow for Low-Biomass Sample Processing

This protocol is designed to minimize contamination from start to finish.

1. Sample Collection:

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear gloves, mask, protective eyewear, and a clean lab coat or disposable sleeves to minimize human-derived contamination [23].

- Equipment: Use sterile, DNA-free consumables. Pre-treat equipment with 80% ethanol and DNA degradation solutions. Note that "sterile" does not automatically mean "DNA-free" [23].

- Controls: Collect field and process blanks (e.g., empty collection tubes, swabs of the air) alongside experimental samples [23].

2. Nucleic Acid Extraction and Library Construction:

- Laboratory Design: Perform pre-PCR steps (sample prep, DNA extraction) in a physically separated, dedicated clean area from post-PCR steps (library amplification). Establish a unidirectional workflow [23].

- Reagent Quality Control: Use certified nucleic-acid-free reagents and consumables. Aliquot reagents to minimize repeated exposure. Pre-treat plasticware with UV-C irradiation [23].

- Control Setup: In every batch, include:

3. Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Bioinformatic Decontamination: Use tools to subtract sequences identified in your negative controls from your experimental samples.

- Quantitative Assessment: Report the abundance and identity of species found in negative controls alongside results from experimental samples to provide context [23].

Protocol 2: In Silico Detection of Sample Cross-Contamination Using SNP Data

This bioinformatic method is adapted from patent literature for detecting low-level cross-contamination [27] [24].

1. SNP Site Selection:

- Frequency Filter (S1): Select SNP sites with a frequency between 0.3 and 0.7 in the target population. This ensures the sites are informative [24].

- Mutation Direction Filter (S2): Focus on SNP sites with a mutation direction of A→T or T→A. This is particularly useful for maintaining clarity in bisulfite-converted sequencing data [24].

- Genomic Context Filter (S3): Exclude SNP sites located within repetitive genomic regions to ensure unique mapping of sequencing reads [24].

- Distance Filter (S4): Select SNP sites that are physically separated from each other by a minimum distance (e.g., >1 Mb) to ensure independent allele measurements [24].

2. Calculation of Sample Contamination Status:

- Allelic Ratio (AR) Analysis: For each selected SNP site in a sample, calculate the allelic ratio, which is the ratio of the number of reads supporting the mutant allele to the total number of reads at that site [24].

- Contamination Index: An algorithm analyzes the distribution of AR values across all selected SNP sites. A shift in this distribution from the expected bimodal pattern (for pure samples) towards intermediate values indicates the presence of DNA from more than one individual, i.e., contamination [24]. The level of contamination can be quantified based on the degree of this shift.

Table 1: Common Contamination Sources and Their Potential Impacts

| Contamination Source | Example | Potential False Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Reagents & Kits | Bacterial DNA in extraction kits | False presence of specific bacteria (e.g., Prevotella) in a sterile site [23]. |

| Laboratory Environment | Airborne dust, lab surfaces, equipment | False association of environmental bacteria with a disease state (e.g., soil bacteria in a placental sample) [23]. |

| Human Handling | Skin cells, saliva aerosol | Misinterpretation of human microbiome based on handler's DNA instead of sample's DNA [23]. |

| Sample Cross-Contamination | Splashing between wells, tube carryover | False positive in clinical diagnostics (e.g., misdiagnosis of infection or cancer) [24] [25]. |

| Sequencing Index Hopping | Misassignment of reads between samples during multiplexing | Inflated diversity measures, incorrect species abundance estimates [23]. |

Table 2: Key Analytical and Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Solution / Reagent | Function in Contamination Control |

|---|---|

| Certified DNA-free Water & Reagents | Provides a baseline with minimal exogenous DNA, reducing background noise in sequencing data [23]. |

| UV Sterilization Cabinet | Degrades contaminating DNA on the surface of plastic consumables (tubes, tips) and liquid reagents before use [23]. |

| DNA Degradation Solutions | Used to decontaminate lab surfaces and equipment, destroying residual DNA that UV might not eliminate [23]. |

| Ultra-clean Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Specifically designed and certified for low-biomass applications, minimizing reagent-derived bacterial DNA [23]. |

| Bioinformatic Decontamination Tools (e.g., Decontam) | Statistically identifies and removes contaminating sequences from feature tables based on their prevalence in negative controls [23]. |

| SNP-based Contamination Detection Algorithm | Uses intrinsic genetic variants to computationally detect and estimate the level of cross-sample contamination [24]. |

Workflow Visualization: Contamination in the NGS Pipeline

Best Practices in Practice: A Step-by-Step Workflow from Sample Collection to Sequencing

A technical support guide for ensuring the integrity of low microbial biomass NGS research.

In the field of low microbial biomass research for Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), the prevention of contamination is not merely a best practice—it is the foundation upon which reliable data is built. Effective pre-sampling decontamination of equipment and surfaces is crucial to avoid the introduction of exogenous DNA that can compromise your results. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to help you navigate these critical procedures.

FAQs: Core Principles of Decontamination

Q1: What is the difference between sterilization and DNA removal in this context?

- Sterilization aims to eliminate all viable microorganisms, thereby preventing biological activity and replication.

- DNA Removal focuses on the physical or chemical destruction of contaminating DNA molecules, regardless of whether the source organism is alive or dead. For sensitive NGS applications, particularly with low microbial biomass samples, the removal of detectable DNA is often the more critical objective, as even non-viable microbial cells can shed DNA that is subsequently amplified and sequenced [30].

Q2: Why is pre-sampling decontamination especially critical for low microbial biomass NGS research? Modern sequencing techniques are exceptionally sensitive and can detect DNA from just a few cells [30]. In low microbial biomass samples (e.g., tissue, blood, or certain environmental samples), the signal from contaminating DNA can easily overwhelm or mask the true target signal, leading to false positives and erroneous conclusions [31] [30]. Contamination can originate from laboratory surfaces, tools, gloves, and even the air [31].

Q3: Which decontamination method is the most effective? No single method is perfect for all situations, and efficacy can vary based on the surface material and the nature of the contaminant (e.g., cell-free DNA vs. DNA within cells). The table below summarizes the DNA removal efficiency of various cleaning strategies tested on different surfaces.

Table: Efficiency of Cleaning Strategies for DNA Removal

| Cleaning Agent | Surface | Contaminant Type | DNA Recovery Post-Cleaning | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) | Plastic, Metal, Wood | Cell-free DNA | Maximum of 0.3% recovered [30] | One of the most effective agents for destroying cell-free DNA. |

| DNA-ExitusPlus IF | Lab surfaces & equipment | Applied gDNA | Near total elimination [31] | Highly effective; increasing incubation time from 10 to 15 minutes improved results. |

| Trigene | Plastic, Metal, Wood | Cell-free DNA | Maximum of 0.3% recovered [30] | Performed equally well as sodium hypochlorite on all tested surfaces. |

| 1% Virkon | Plastic, Metal, Wood | Whole Blood (cell-contained DNA) | Maximum of 0.8% recovered [30] | The most efficient strategy for decontaminating blood from all three surfaces. |

| 70% Ethanol | Plastic, Metal, Wood | Cell-free DNA | Up to 52% recovered on plastic [30] | Not recommended as a standalone DNA decontamination agent; poor DNA removal. |

| UV Radiation (20 min) | Plastic, Metal, Wood | Cell-free DNA | Significant recovery on plastic and wood [30] | Variable and surface-dependent; inefficient on plastic and wood, better on metal. |

Q4: Are common laboratory disinfectants like ethanol sufficient for DNA removal? No. Studies conclusively show that 70-85% ethanol is not effective for reliable DNA destruction [31] [30]. While excellent for general disinfection, it leaves a substantial proportion of DNA intact, making it unsuitable for critical NGS pre-sampling decontamination where trace DNA is a concern.

Experimental Protocols for Decontamination

Protocol A: Surface Decontamination with DNA-ExitusPlus IF

This protocol is adapted from a study comparing DNA sterilization procedures in forensic labs [31].

1. Application of Contaminant (Control)

- Apply genomic DNA (e.g., ~20 ng/µL) to a clean, designated test surface and allow it to dry for 15 minutes.

- Using a duplicate cotton swab, swab a portion of the applied DNA area as a pre-treatment control.

2. Decontamination Procedure

- Spray or apply DNA-ExitusPlus IF (or a comparable commercial DNA decontaminant) thoroughly to cover the contaminated area.

- Incubate for 15 minutes. The study found that increasing the incubation time from 10 to 15 minutes enhanced decontamination efficiency [31].

- After incubation, wipe the area clean with a dust-free paper or swab.

3. Post-Treatment Swabbing and Analysis

- Use a fresh duplicate cotton swab to sample the decontaminated area.

- Extract DNA from both the pre- and post-treatment swabs.

- Quantify the recovered DNA using a sensitive method like real-time PCR to confirm the reduction in DNA quantity [31].

Protocol B: Decontamination of Benchtop Equipment with Sodium Hypochlorite

This protocol is based on the evaluation of cleaning strategies for DNA removal [30].

1. Preparation of Decontaminant

- Use a freshly diluted sodium hypochlorite solution (e.g., 0.4% - 0.54% final concentration). Note that the concentration of available chlorine decreases over time, so stored dilutions are less effective [30].

2. Application and Wiping

- Administer the solution to the artificially contaminated surface using a calibrated spray bottle for consistent coverage.

- Wipe the area in three circular movements to ensure full contact with all surfaces.

- Allow the area to dry completely (approximately 120 minutes).

3. Verification of Efficiency

- Swab the entire cleaned area with a cotton swab moistened in 0.9% sodium chloride.

- Extract and quantify the residual DNA. Efficient strategies should recover less than 1% of the originally deposited DNA [30].

Troubleshooting Common Decontamination Issues

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Decontamination Protocols

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background DNA in NGS Controls | Ineffective decontamination of reusable equipment or work surfaces. | Transition from ethanol to a proven DNA-destroying agent like sodium hypochlorite or DNA-ExitusPlus IF. Increase contact time as per protocol [31] [30]. |

| Inconsistent Decontamination Across Lab | Variable application techniques and incubation times between personnel. | Standardize protocols: use calibrated spray bottles, timers, and detailed work instructions for all staff. |

| Corrosion of Metal Equipment | Repeated use of high-concentration bleach on sensitive instruments. | For metal surfaces where bleach is unsuitable, validate an alternative like DNA-ExitusPlus IF or Trigene. Always ensure adequate rinsing if recommended by the manufacturer. |

| PCR Inhibition Downstream | Residual decontaminant carried over into samples. | After decontaminating surfaces that will contact samples directly (e.g., pipettors), ensure a final rinse with DNA-free water and complete drying. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for DNA Decontamination

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-ExitusPlus IF | Commercial DNA decontamination solution designed to degrade DNA. | Highly effective; requires a defined incubation time (e.g., 15 min). Ready-to-use formulation [31]. |

| Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) | Oxidizes and breaks down DNA molecules. | Highly effective and low-cost; must be freshly diluted for reliable results. Can be corrosive and degrade with storage [30]. |

| Trigene | Commercial disinfectant and cleaner. | Shown to be highly effective against cell-free DNA on multiple surfaces [30]. |

| 1% Virkon | Broad-spectrum disinfectant powder. | Particularly effective for decontaminating whole blood from various surfaces [30]. |

| UV Light | Causes DNA damage (strand breaks) through irradiation. | Efficacy is highly variable and surface-dependent; should not be relied upon as a sole method, especially for plastic and wood [30]. |

Workflow: Selecting a Decontamination Strategy

This decision diagram helps you select an appropriate decontamination method based on your specific equipment and contamination concerns.

For any feedback or corrections on this technical support guide, please contact the designated technical support lead at your institution.

FAQs: PPE and Contamination Control in Low Biomass NGS

Q1: Why is PPE considered a critical component in sample collection for low microbial biomass NGS studies?

PPE acts as a fundamental physical barrier, serving as the last line of defense to prevent the introduction of contaminating nucleic acids from researchers into sensitive samples [32]. In low microbial biomass research, where the target genetic material is minimal, even trace contamination from human skin, hair, or saliva can overwhelm the true signal, leading to false positives and compromising data integrity [33]. Proper PPE use is therefore not just for personal safety but is essential for data accuracy.

Q2: What constitutes "basic laboratory PPE" for handling samples destined for NGS?

The primary pieces of basic PPE for laboratories include long pants, closed-toe shoes, a lab coat, and safety glasses [32]. Gloves should be added to this outfit to prevent skin contact and contamination [32]. For the highest protection against common incidents, consider modern, multihazard lab coats that offer both flame resistance and chemical splash protection [32].

Q3: What are the most common sources of amplicon contamination, and how can PPE help manage them?

Amplicon contamination, generated during PCR at very high copy numbers, is a significant risk [34]. Common sources include thermocyclers, pipettes, bench surfaces, and even less obvious items like doorknobs, laboratory calculators, and reagent bottles [34]. PPE helps manage this by acting as a containent barrier. Furthermore, a strict protocol of changing the full set of PPE, including gloves sterilized frequently with 70% ethanol, when moving between different laboratory areas (e.g., from pre- to post-PCR) is crucial to prevent the spread of amplicons [34].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Contamination in Low Biomass Workflows

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Consistent detection of human or environmental microbial sequences in negative controls. | Inadequate PPE; contaminated gloves or lab coats transferring contaminant DNA. | Implement a strict PPE protocol: wear dedicated lab coats and gloves, and change gloves when moving between workflows or after touching non-sterile surfaces [34] [35]. |

| High levels of specific amplicon sequences (e.g., from a previous PCR) in control samples. | Cross-contamination from amplicon aerosols carried on PPE or skin. | Decontaminate laboratory surfaces with 0.5% sodium hypochlorite and 75% ethanol [34]. Ensure unidirectional workflow and change PPE when moving from post-PCR to pre-PCR areas [34]. |

| Low sequencing library complexity or high levels of chimeric reads. | Inefficient library construction, potentially exacerbated by contaminated reagents or surfaces. | Use sterile equipment and aseptic techniques during sample collection and library prep [35]. Employ A-tailing of PCR products to reduce chimera formation and use magnetic bead-based clean-up to remove unwanted fragments [36]. |

| Fluctuating or inconsistent contamination levels on specific surfaces (e.g., freezer handles, benches). | Persistent environmental amplicon colonization and ineffective decontamination. | Implement a rigorous, routine environmental decontamination strategy twice daily for several weeks. Include a DNase decontamination reagent in the cleaning routine to fully eliminate persistent amplicons [34]. |

Experimental Data: Evidence of Contamination and Decontamination Efficacy

The following data, compiled from studies on laboratory contamination, illustrates the prevalence of contaminating nucleic acids and the effectiveness of systematic decontamination protocols.

Table 1: Sources and Levels of Environmental Amplicon Contamination Identified by qPCR [34]

| Contaminated Surface/Item | Cycle Threshold (Ct) Value Range (Indicator of Contamination Level) |

|---|---|

| Thermocyclers | Ct < 37 (High titer) |

| Pipettes | Ct < 37 (High titer) |

| Bench Surfaces | Ct < 37 (High titer) |

| Doorknobs | Ct < 37 (High titer) |

| Laboratory Calculator | Ct < 37 (High titer) |

| PCR Cabinets | Ct < 37 (High titer) |

Table 2: Effectiveness of a 5-Week Systematic Decontamination Strategy [34]

| Week | Observation |

|---|---|

| 1-3 | High levels of amplicon contamination detected on multiple surfaces. |

| 4 | Contamination persisted on 4 out of 19 swabbed surfaces. |

| 5 | After incorporating a DNase decontamination reagent, amplicons were eliminated from all swabbed surfaces. |

Workflow: Integrating PPE and Physical Barriers in Sample Collection

The following diagram outlines the integrated workflow for proper sample collection, emphasizing the critical points for PPE application and physical barrier usage to ensure sample integrity for low biomass NGS.

Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Effective Decontamination and Sample Integrity

| Item | Function in Contamination Control |

|---|---|

| 70-75% Ethanol | Used for disinfecting work surfaces and sterilizing gloves. It is effective against many contaminants and evaporates cleanly [34] [35]. |

| 0.5% Sodium Hypochlorite | A freshly prepared bleach solution is highly effective for decontaminating laboratory surfaces and immersing racks to destroy contaminating nucleic acids [34]. |

| DNA Decontamination Reagent | A specific commercial reagent (often containing DNase) used to eliminate DNA contamination from laboratory equipment like pipettes and thermocyclers [34]. |

| Sterile Flocked Swabs | Used for environmental monitoring and sample collection. Their design allows for high sample elution, making them effective for detecting contamination [33]. |

| Barcoded Adapters | Molecular barcodes added during NGS library preparation allow multiple samples to be pooled and sequenced simultaneously while tracking them computationally, helping identify cross-sample contamination [37]. |

FAQs: The Role of Controls in Low Biomass Research

What are the essential types of controls for low biomass NGS studies?

In low microbial biomass research, where contaminating DNA can easily overwhelm the true biological signal, implementing a panel of controls is non-negotiable. The essential controls are:

- Negative Controls (or Extraction Blanks): These contain only the DNA extraction reagents and are processed alongside your experimental samples. They identify contaminating DNA introduced from your kits, laboratory environment, and reagents [1] [9].

- Sampling Controls: These account for contamination introduced during the sample collection process. Examples include an empty collection vessel, a swab exposed to the air in the sampling environment, or an aliquot of the preservation solution [1].

- Mock Communities (Positive Controls): These are samples containing a known mixture and quantity of microbial cells or DNA. They are vital for verifying that your entire workflow—from DNA extraction to sequencing and bioinformatics—is functioning correctly and without bias, especially for detecting low-abundance taxa [38].

Why am I detecting microbial signal in my negative controls?

Detecting microbial DNA in negative controls is a common challenge and indicates the presence of background contamination. Key sources and solutions include:

- Reagent "Kitome": Your DNA extraction and library preparation kits themselves are a major source of microbial DNA. This "kitome" profile varies by brand and, critically, by manufacturing lot [9].

- Laboratory Environment: Contamination can come from the lab environment, equipment, and personnel [1] [39].

- Cross-Contamination: DNA can transfer between samples during processing. One study found that using ethanol to clean scissors between processing dried blood spots was insufficient and led to cross-contamination, whereas using DNase prevented it [40].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Increase Decontamination Rigor: Move beyond ethanol. Decontaminate surfaces and tools with a DNA-degrading solution like sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or commercially available DNA removal solutions [1].

- Profile Your Reagents: Include extraction blanks for every new lot of DNA extraction kits you use, as the contaminant profile can vary significantly [9].

- Use Computational Tools: Employ bioinformatics tools like Decontam, which can statistically identify and remove contaminating sequences found in your negative controls from your experimental data [9].

My positive control and negative control show similar results. What went wrong?

If your positive control (e.g., a mock community) and negative control yield similar outputs, this indicates a severe failure in your experiment [39].

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Amplicon Contamination: This is a likely culprit, especially in PCR-based methods like 16S amplicon sequencing. Trace amounts of amplified DNA from previous experiments can contaminate your reagents and workspace.

- Inadequate Workspace Separation: Maintain physically separated pre- and post-PCR workstations. The pre-PCR area should be a dedicated clean room with positive airflow, if possible [39].

- Degraded Control Material: If the RNA or DNA in your positive control is degraded, it will not amplify properly, leading to low yield that resembles a negative control. Always prepare fresh dilutions of control material and use RNase/DNase-free reagents and plastics [39].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Scenarios and Solutions

| Problem Scenario | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High diversity in negative controls ("kitome") | Contaminating DNA in extraction kits/reagents [9] | - Use multiple negative controls per kit lot.- Apply bioinformatic decontamination (e.g., Decontam) [9]. |

| Low biomass samples show bias (e.g., toward one taxon) | Technical bias of method in low-biomass regime [38] | - Validate with a dilution series of a mock community.- Consider shifting from 16S to shallow metagenomics [38]. |

| Signal detected in blank swab controls | Contamination during sample collection [1] | - Implement stricter sampling protocols: use sterile, single-use equipment; wear full PPE (gloves, mask, coveralls) [1]. |

| Cross-contamination between samples | Inadequate decontamination of reusable tools [40] | - Clean tools with DNase solution instead of just ethanol or water between samples [40]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Profiling Background Contamination in DNA Extraction Kits

This protocol helps you characterize the "kitome" of your specific reagent lots, which is essential for accurate interpretation of low biomass data [9].

Materials:

- DNA extraction kits from different brands or lots.

- Molecular Biology Grade (MBG) water, confirmed DNA-free.

- (Optional) ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control I.

Procedure:

- For each DNA extraction kit brand and lot you plan to use, set up extraction blanks in triplicate.

- Use MBG water as the input material and follow the manufacturer's extraction protocol without deviation.

- Process these blanks through the entire downstream workflow, including library preparation and sequencing, alongside your experimental samples.

- Sequence the resulting libraries (e.g., using Illumina MiSeq or NovaSeq platforms).

Data Interpretation:

- The resulting microbial profile from the extraction blank is the contaminant background for that specific kit and lot.

- Use this profile to inform computational decontamination. Any sequence found in your experimental samples that matches a contaminant in the blank is suspect [9].

Setting Abundance Thresholds Using Mock Communities

This method uses a dilution series of a mock community to establish data-driven thresholds for filtering out low-level contamination [38].

Procedure:

- Create a mock community with a known number of cells (e.g., 10^5-10^8 CFUs/mL) and prepare a dilution series.

- Process the dilution series using your standard NGS workflow.

- In the data from your most diluted sample, identify the relative abundance threshold that retains all expected input species while removing the maximum number of non-input (contaminant) taxa.

- Apply this sample-specific threshold to your entire dataset. A taxon must be above this threshold in a given sample to be retained.

This method is superior to using a fixed threshold because it dynamically accounts for the fact that contamination has a larger proportional impact in lower biomass samples [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Low Biomass Research |

|---|---|

| DNA Removal Solutions (e.g., sodium hypochlorite, commercial DNA Zap solutions) | Degrades contaminating environmental DNA on surfaces and equipment; more effective than ethanol alone [1]. |

| DNase I | An enzyme that digests DNA; used to decontaminate reusable tools like scissors to prevent sample-to-sample cross-contamination [40]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control I (or similar) | A defined microbial community added to a sample as an internal positive control to monitor extraction and sequencing efficiency [9]. |

| Micronbrane DEVIN Microbial DNA Enrichment Kit | An example of a commercial kit designed for microbial DNA extraction, often from challenging samples [9]. |

| Unison Ultralow DNA NGS Library Preparation Kit | A library prep kit designed for minimal input DNA, helping to reduce background in low biomass applications [9]. |

NGS Experimental Workflow with Critical Control Points

Contamination Troubleshooting Logic

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) offers a powerful, hypothesis-free approach for infectious disease diagnostics and microbiome research. However, a significant obstacle, especially in low-microbial-biomass clinical samples, is the overwhelming abundance of host-derived nucleic acids, which can constitute over 99% of the sequenced material. This excess host DNA consumes valuable sequencing capacity and severely obscures the microbial signal, leading to reduced sensitivity and potential diagnostic failures [41] [42] [43]. Host DNA depletion strategies are thus critical for enhancing the detection of pathogens. These methods are broadly categorized into pre-extraction and post-extraction techniques, each with distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations. This guide provides a technical overview and troubleshooting resource for implementing these methods within a research or clinical framework focused on challenging sample types.

FAQs: Method Selection and Performance

1. What is the fundamental difference between pre-extraction and post-extraction host depletion methods?

- Pre-extraction methods physically separate or lyse host cells before DNA is extracted from the entire sample. They target intact microbial cells or cell-free DNA.

- Post-extraction methods remove host DNA after total DNA (host and microbial) has been extracted from the sample, typically by exploiting biochemical differences like methylation patterns.

2. Which method is most effective for respiratory samples like BALF or sputum?

Pre-extraction methods are generally more effective for respiratory samples, which are characterized by very high host DNA content. A 2024 benchmark study on frozen respiratory samples found:

- Commercial Kits: The HostZERO and MolYsis kits significantly reduced host DNA proportion and increased microbial reads by 10 to 100-fold in Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) and sputum samples [42].

- Saponin-based Methods: A 2025 study noted that saponin lysis followed by nuclease digestion (S_ase) was one of the most effective methods for host removal from BALF samples [41].

- Post-extraction Warning: The same 2025 study reported that post-extraction methods like the NEBNext kit demonstrated poor performance in removing host DNA from respiratory samples [41].

3. How do host depletion methods impact the representation of the microbial community?

Most host depletion methods can introduce taxonomic bias, as some microbial cells may be more susceptible to lysis or loss during processing. Key findings include:

- Biomass Reduction: All methods can significantly reduce total bacterial DNA biomass, with some methods retaining less than 31% of the original bacterial load [41].

- Taxonomic Shifts: Specific commensals and pathogens, such as Prevotella spp. and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, can be significantly diminished by certain depletion protocols [41].

- Altered Composition: One study found that host depletion did not majorly change the community structure for BAL and nasal samples but did decrease the proportion of Gram-negative bacteria in sputum from people with cystic fibrosis [42]. It is crucial to validate methods using mock microbial communities.

4. What are the common points of failure when working with host-depleted samples, and how can they be mitigated?

The primary challenge is the very low amount of microbial DNA remaining after host depletion, which can lead to library preparation failure.

- Challenge: Standard library prep protocols adapted from whole-genome sequencing are often unreliable with DNA inputs below 10 ng, which is common after host depletion [45].

- Solution: Use library prep kits specifically designed for ultralow DNA inputs. One benchmarking study demonstrated that specialized kits (e.g., Unison Ultralow DNA NGS Library Prep Kit) maintained taxonomic accuracy and replicate consistency down to 1 ng input, whereas standard kits exhibited significant amplification bias [45].

Performance Data and Method Comparisons

Table 1: Comparison of Host Depletion Method Performance Across Clinical Sample Types

| Method Category | Specific Method | Key Principle | Best For Sample Type | Host Depletion Efficiency | Microbial DNA Retention | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-extraction | Saponin + Nuclease (S_ase) [41] | Lyses mammalian cells; digests DNA | BALF | High (to 0.01% of original) | Moderate | Potential taxonomic bias |

| Pre-extraction | HostZERO Kit [42] | Selective host cell lysis | Sputum, Nasal Swabs | High (73.6% decrease in nasal) | Moderate | Library prep failure in some BALF |

| Pre-extraction | QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit [41] [42] | Differential lysis | Nasal Swabs | High (75.4% decrease in nasal) | High in OP samples | - |

| Pre-extraction | ZISC Filtration [44] | Filters host cells; passes microbes | Whole Blood (Sepsis) | >99% WBC removal | High (10x microbial read increase) | Not for cell-free DNA |

| Pre-extraction | F_ase (Filter + Nuclease) [41] | Filters & digests host DNA | BALF | High (65.6-fold ↑ microbial reads) | Balanced performance | - |

| Post-extraction | NEBNext Microbiome Enrichment [41] [44] | Binds methylated host DNA | (Generally poor performance on respiratory samples) | Low | Varies | Inefficient for high-host content samples |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Library prep failure after host depletion | Input DNA concentration too low or undetectable | Use a library prep kit validated for ultralow-input DNA (e.g., down to 0.1 ng) [45]. |

| Low microbial read count after host depletion | Inefficient host removal; method not suited to sample type | Switch to a more effective pre-extraction method (e.g., for BALF, use S_ase or HostZERO) [41] [42]. |

| Skewed microbial community profile | Taxonomic bias from the depletion method; uneven lysis | Validate the protocol with a mock microbial community that includes species with different cell wall structures [41]. |

| High contamination in negatives | Introduction of contaminants during multi-step process | Include negative controls at all stages (reagent-only, extraction); use solutions with agar to improve yield and reduce relative contaminant abundance [46]. |

| Poor yield from frozen samples | Loss of microbial viability or DNA integrity from freezing | Add a cryoprotectant like glycerol before freezing to preserve Gram-negative bacteria viability [41] [42]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Host Depletion for Respiratory Samples using a Saponin-Based Method

This protocol is adapted from methods benchmarked in recent studies [41].

Principle: Saponin lyses mammalian cells (which lack tough cell walls), releasing host DNA. Subsequent nuclease digestion degrades the exposed DNA, while intact microbial cells are protected.

Materials:

- Clinical sample (e.g., BALF, sputum)

- Saponin stock solution

- DNase I or similar nuclease

- Proteinase K

- Centrifuge and refrigerated microcentrifuge

- Lysis buffer appropriate for downstream DNA extraction kit

Workflow:

Key Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge the liquid sample to pellet cells. Resuspend the pellet in a suitable buffer.

- Host Cell Lysis: Add saponin to a final concentration of 0.025% (optimized from tested ranges of 0.025%-0.50% [41]). Mix thoroughly and incubate at room temperature for 15-30 minutes.

- Nuclease Digestion: Add the nuclease enzyme according to the manufacturer's instructions and incubate to digest free DNA.

- Termination & Washing: Add a stop solution (e.g., EDTA for DNase) and centrifuge to pellet the intact microbial cells. Carefully remove the supernatant containing digested host DNA.

- DNA Extraction: Wash the pellet and proceed with a robust microbial DNA extraction method, such as enzymatic lysis or a commercial kit.

Protocol 2: Host Depletion for Blood Samples using ZISC-based Filtration

This protocol is based on a novel filtration device validated for sepsis diagnostics [44].

Principle: A zwitterionic interface coating on a filter binds and retains host leukocytes while allowing bacteria and viruses to pass through unimpeded, effectively enriching the microbial content in the filtrate.

Materials:

- Whole blood sample (3-13 mL)

- Novel ZISC-based fractionation filter (e.g., "Devin" from Micronbrane)

- Syringe

- Collection tube

- Reagents for genomic DNA extraction from the filtrate

Workflow:

Key Steps:

- Setup: Transfer a defined volume of whole blood (e.g., 4 mL) into a syringe and securely attach the ZISC filter.

- Filtration: Gently depress the syringe plunger to pass the blood through the filter into a sterile collection tube. Avoid excessive force.

- Processing: The filtrate now contains enriched microbial cells and is ready for DNA extraction. For gDNA-based mNGS, centrifuge the filtrate at high speed (e.g., 16,000g) to pellet microbial cells, then extract DNA from the pellet [44].

- Note: This method is suitable for genomic DNA-based workflows but is not applicable to cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis from plasma.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Kits

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Host DNA Depletion

| Product Name | Provider | Function/Basic Principle | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit | Zymo Research | Pre-extraction; selective lysis of host cells. | Effective on sputum and nasal swabs; may have high library prep failure rate for very low biomass BALF [42]. |

| QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit | Qiagen | Pre-extraction; differential lysis and filtration. | Shows high bacterial retention in oropharyngeal (OP) samples [41]. |

| MolYsis Basic Kit | Molzym | Pre-extraction; selective lysis of human cells. | Effective on sputum, reducing host DNA by ~70% [42]. |

| NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit | New England Biolabs | Post-extraction; binds CpG-methylated host DNA. | Shows poor performance on respiratory samples; use is not recommended for these types [41] [44]. |

| Unison Ultralow DNA NGS Library Prep Kit | Micronbrane | Library preparation for low-input DNA. | Critical for downstream success; maintains taxonomic fidelity with inputs as low as 1 ng [45]. |

| Novel ZISC-based Filtration Device | Micronbrane | Pre-extraction; physical filtration of host white blood cells. | Designed for whole blood; enables gDNA-based mNGS for sepsis with >10x enrichment of microbial reads [44]. |

| Agar-containing Solution (AgST) | In-house preparation | Improves DNA recovery; acts as a co-precipitant. | Useful for maximizing yield from extremely low-biomass specimens like skin swabs [46]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: For low-biomass respiratory samples, should I prioritize the high accuracy of short-read sequencing or the species-level resolution of long-read sequencing?

The choice depends heavily on your primary research objective.

- Choose short-read sequencing (e.g., Illumina) when your goal is a broad, cost-effective microbial survey to understand overall community structure and diversity at the genus level. Its high accuracy (>99.9%) is ideal for detecting a wide range of taxa in complex communities [47] [48].

- Choose long-read sequencing (e.g., Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) when you require species-level or even strain-level identification. The ability to sequence the entire 16S rRNA gene (~1,500 bp) provides much finer taxonomic resolution, which is crucial for identifying specific pathogens or closely related microbial groups [47] [48].

Recent studies on respiratory microbiomes have found that while Illumina may capture greater species richness, Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) provides superior resolution for dominant species. Note that each technology has specific biases; ONT may overrepresent certain taxa like Klebsiella, while Illumina might better capture others like Prevotella [48].

FAQ 2: What is the biggest challenge when preparing sequencing libraries from low-biomass samples, and how can it be mitigated?

The most significant challenge is the low concentration of input DNA and the ever-present risk of contamination from reagents or the laboratory environment ("kitome") [2].

Mitigation strategies include:

- High-Efficiency Extraction: Use extraction protocols specifically validated for low-biomass samples, such as the NAxtra magnetic nanoparticle protocol, which is automatable and provides high-quality nucleic acids quickly [49].

- Sample Concentration: Employ concentration techniques like liquid filtering (e.g., hollow fiber concentration) or SpeedVac concentration after extraction [2].

- Increased PCR Cycles: Modifying protocols like the Oxford Nanopore Rapid PCR Barcoding kit by increasing the number of PCR cycles can help amplify the low quantity of DNA to a sufficient level for library preparation [2].

- Rigorous Controls: Processing multiple negative controls (e.g., sterile water, reagent blanks) in parallel with your samples is non-negotiable. This allows for the identification and bioinformatic subtraction of contaminating sequences during analysis [2].

FAQ 3: My long-read data from a low-biomass sample has a high error rate. How can I improve its accuracy?

While the raw read accuracy of long-read technologies has improved significantly, several wet-lab and bioinformatic strategies can further enhance data quality:

- Use HiFi Reads: For PacBio systems, use the Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) mode to generate HiFi reads. This method sequences the same DNA molecule multiple times, producing reads with accuracies exceeding 99.9% [50] [51].

- Optimize Base-Calling: For Oxford Nanopore data, use the most advanced base-calling models available, such as the High Accuracy (HAC) model, which improves base-calling precision [48].

- Hybrid Assembly: Combine your long-read data with short-read Illumina data. The short reads, with their very high per-base accuracy, can be used to polish and correct errors in the long-read assembly, resulting in a highly accurate final genome [52]. One study on a mock viral community found that a hybrid Illumina-Nanopore assembly reduced error rates to levels comparable with short-read-only assemblies [52].

FAQ 4: Is portable, on-site sequencing a feasible option for low-biomass studies?

Yes, portable sequencing is becoming a reality and offers a powerful tool for rapid, on-site analysis. The portability and real-time data generation of devices like the Oxford Nanopore MinION make them highly suitable for remote settings or during infectious disease outbreaks [47] [2].

A proof-of-concept study demonstrated a complete workflow for sequencing ultra-low biomass samples from cleanroom surfaces in under 24 hours using a portable nanopore sequencer [2]. This approach is invaluable for rapid pathogen identification and microbial monitoring. However, it requires careful on-site protocols to manage contamination risks and may currently involve a trade-off between speed and the highest possible sequencing depth.

Sequencing Platform Comparison for Low-Biomass Research

The table below summarizes the core technical differences between the major sequencing platform types to guide your selection.

| Aspect | Short-Read (e.g., Illumina) | Long-Read (Oxford Nanopore) | Long-Read (PacBio HiFi) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Read Length | 50-600 bases [47] [51] | 20 bp -> 1 Mb+ [50] [51] | 500 - 20,000+ bases [50] |

| Key Strength | High base accuracy (>99.9%); Cost-effective per base [47] [48] | Portability; Real-time data; Full-length 16S sequencing [47] [48] | Very high accuracy (Q30+) with long reads [50] [51] |

| Key Weakness | Limited resolution for repetitive regions and complex genomes [47] | Historically higher error rates, though improving [48] [52] | Higher instrument cost; requires more DNA input [47] [50] |

| Best for Biomass-Limited | Broad taxonomic surveys (genus-level); Maximizing species richness detection [48] | Rapid, on-site analysis; Species-level resolution where portability is key [47] [2] | High-resolution metagenomics and genome assembly when sample quality permits [47] |

Experimental Protocol: NAxtra Nucleic Acid Extraction for Low-Biomass Respiratory Samples

This protocol, adapted from a peer-reviewed pilot study, is designed for high-throughput, cost-effective nucleic acid extraction from low-microbial biomass respiratory samples like nasopharyngeal aspirates and nasal swabs [49].

1. Sample Collection and Input

- Collect nasopharyngeal aspirate, nasal swab, or saliva samples using standard clinical procedures.

- Use a sample input volume of 100 µL for the extraction process [49].

2. Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Kit: NAxtra nucleic acid extraction kit (Lybe Scientific).

- Automation Platform: Perform the extraction on an automated liquid handling workstation, such as a Tecan Fluent or a KingFisher Flex system. Automation increases throughput and reduces cross-contamination risk.

- Procedure: Follow the manufacturer's instructions. The process can be completed in as little as 14 minutes for 96 samples on a KingFisher system [49].

3. Protocol Modification for Low Biomass

- Critical Step: To increase the final DNA concentration for downstream sequencing, decrease the elution buffer volume from the standard 100 µL to 80 µL [49].

4. Quality Control

- Quantify the double-stranded DNA concentration in the eluate using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit 3.0 with the dsDNA HS Assay Kit) [49].

- Proceed to library preparation (e.g., 16S rRNA gene amplification) using 2 µL of the DNA eluate as input [49].

Workflow Diagram: Platform Selection for Low-Biomass Samples

The following diagram outlines a logical decision pathway for selecting a sequencing platform based on your research goals and sample constraints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Kits

| Item | Function | Application in Low-Biomass Research |

|---|---|---|

| NAxtra Nucleic Acid Kit [49] | Magnetic nanoparticle-based extraction of DNA/RNA | Fast, automatable, and cost-effective protocol for respiratory samples. |

| SALSA Sampler [2] | Surface sampling device using squeegee-aspiration | High-efficiency collection from large surface areas, bypassing swab absorption. |

| InnovaPrep CP Concentrator [2] | Hollow fiber filter to concentrate dilute liquid samples | Concentrates samples post-collection to increase analyte concentration for sequencing. |