Comparative Validation of Machine Learning Algorithms for Material Property Prediction: A 2025 Benchmarking Guide

This article provides a comprehensive, comparative analysis of machine learning (ML) algorithms for predicting material properties, a critical task in accelerating material discovery and design.

Comparative Validation of Machine Learning Algorithms for Material Property Prediction: A 2025 Benchmarking Guide

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, comparative analysis of machine learning (ML) algorithms for predicting material properties, a critical task in accelerating material discovery and design. Tailored for researchers and scientists, we explore the foundational ML models used in materials informatics, detail their methodological application to key properties like tensile strength and phase stability, and address critical troubleshooting aspects such as dataset redundancy and small-data challenges. A core focus is the objective validation of algorithm performance across diverse material classes, including metallic glasses and high-entropy alloys, offering a clear, evidence-based guide for selecting and optimizing ML strategies to replace traditional trial-and-error approaches.

The Foundations of Machine Learning in Materials Informatics

The integration of machine learning (ML) into materials science has catalyzed a paradigm shift from traditional, labor-intensive discovery processes towards data-driven, predictive research. This transition addresses a critical challenge: conventional material research and development typically spans 10–20 years, requiring significant resources and extensive experimentation [1]. ML technologies offer benefits of low cost, high efficiency, and shorter development cycles by rapidly identifying complex, non-linear relationships between material composition, processing parameters, microstructure, and resulting properties [1] [2].

The application of ML in materials science has grown exponentially, with studies applying ML to materials science increasing at a rate of approximately 1.67 times per year over the past decade [3]. This growth is fueled by the recognition that ML can navigate the vast chemical and structural space of possible materials more efficiently than traditional computational methods like density functional theory (DFT), which provide high accuracy but are computationally expensive and often restricted to small systems [4] [5].

This guide provides a comparative validation of core ML algorithms for material property prediction, offering researchers a structured framework for selecting appropriate methodologies based on specific research objectives, data constraints, and target material properties.

Core Machine Learning Algorithms: Principles and Applications

Machine learning algorithms in materials science are broadly categorized based on their learning mechanisms. Understanding these categories is essential for selecting the appropriate tool for a given predictive task.

Supervised Learning: This approach uses labeled datasets to train models that map input features to known outputs. It is the most widely used paradigm in materials informatics, predominantly applied to classification tasks (e.g., identifying crystal phases) and regression tasks (e.g., predicting formation energy or mechanical strength) [6] [2]. The effectiveness of supervised learning relies heavily on the quality and quantity of labeled data.

Unsupervised Learning: This approach uncovers hidden patterns, groupings, or intrinsic structures within unlabeled datasets. It is particularly valuable for exploratory data analysis, such as identifying novel material classes or clustering materials with similar characteristics without predefined labels [6].

Semi-Supervised & Self-Supervised Learning: These emerging paradigms leverage a small amount of labeled data alongside large pools of unlabeled data. They are especially useful in materials science where obtaining labeled data through experiment or simulation is expensive and time-consuming [6].

Reinforcement Learning: This involves training algorithms to make a sequence of decisions by interacting with an environment to maximize cumulative rewards. While less common in property prediction, it shows promise in areas like optimizing synthesis processes [6].

Table 1: Overview of Core Machine Learning Algorithms in Materials Science

| Algorithm | Category | Primary Use Cases in Materials Science | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear & Logistic Regression | Supervised | Predicting continuous properties (Young's modulus), binary classification [6] [2] | Simple, interpretable, efficient with linear relationships [6] |

| Decision Trees | Supervised | Classification and regression tasks, modeling business rules, risk assessment [6] | Handles numerical/categorical data, highly interpretable [6] |

| Random Forest | Supervised | Property prediction (formation energy, band gap), credit scoring, product recommendation [3] [6] | Reduces overfitting via ensemble learning, robust with high-dimensional data [6] [2] |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Supervised | Bioinformatics, image recognition, text categorization [6] [2] | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, versatile with kernel functions [6] |

| Gradient Boosting Machines (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost) | Supervised | Top performer in predictive modeling competitions, finance, marketing analytics [6] | High predictive accuracy, sequential error correction [6] |

| Neural Networks (NN) & Deep Learning (DL) | Supervised/Unsupervised | Graph Neural Networks for crystal properties, CNNs for image-based microstructure analysis [3] [7] [2] | Captures complex non-linear relationships, automatic feature extraction from raw data [2] |

Comparative Performance Analysis for Material Property Prediction

Evaluating the performance of ML algorithms requires careful consideration of the specific prediction task, data representation, and most importantly, rigorous dataset splitting protocols to avoid overestimation of performance.

Performance in Crystal Property Prediction

For fundamental electronic and energetic properties, different algorithms exhibit varying strengths. A dramatic 7-fold error reduction was observed when moving from feature-based conventional ML (e.g., Random Forest, SVR) to Graph Neural Network (GNN) techniques on the matbench benchmark for formation enthalpy prediction [3]. GNNs, which directly operate on the atomic graph structure of a crystal, have demonstrated capabilities to predict formation energies, band gaps, and elastic moduli of crystals with accuracy that can rival or even surpass DFT calculations on benchmark datasets [5].

However, these reported high accuracies must be interpreted cautiously. Studies have shown that dataset redundancy—where training and test sets contain highly similar materials due to historical "tinkering" in material design—can lead to significant overestimation of model performance when using random splits [5]. When redundancy control algorithms like MD-HIT are applied, prediction performances on test sets tend to be lower but better reflect the models' true extrapolation capability [5].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Algorithms for Key Prediction Tasks

| Prediction Task | Algorithm Examples | Reported Performance (with caveats) | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy/Enthalpy | Random Forest [3], Graph Neural Networks [3] [5] | GNNs achieved 7x lower error than conventional ML on matbench [3]. MAE of 0.064 eV/atom reported (context of dataset redundancy) [5]. | Dataset redundancy can inflate performance metrics. GNNs show superior performance but require more data and computation [5]. |

| Band Gap Prediction | Conventional ML (Composition-based) [5], Graph Neural Networks [5] | Accurate prediction reported using composition alone, especially for thermodynamically stable compounds [5]. | Performance is often overestimated due to redundant samples in standard datasets [5]. |

| Mechanical Properties of Composites | Regression Neural Network [8], SVM, Random Forest [2] [8] | Regression Neural Network achieved R² = 1, RMSE = 34.385, MAE = 19.829 for laminate stress-strain prediction [8]. | Neural networks can offer extreme speed (0.6s vs. 34.5s for FE simulation) but require sufficient training data [8]. |

Addressing the Small Data Challenge

A significant reality in materials science is that many research groups work with small data, where the sample size is limited. This creates challenges including model overfitting, underfitting, and imbalanced data [9]. Solutions to this dilemma operate at multiple levels:

- Data Source Level: Extracting data from publications, constructing specialized material databases, and employing high-throughput computations and experiments [9].

- Algorithm Level: Using modeling algorithms robust to small data and techniques for imbalanced learning [9].

- ML Strategy Level: Implementing active learning and transfer learning to maximize the value of limited data [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Workflow for ML-Based Material Property Prediction

A robust workflow is essential for developing reliable ML models in materials science. The process typically involves several interconnected stages [9]:

Data Collection: The foundation of any ML project. Data can be sourced from published literature, materials databases (e.g., Materials Project, OQMD), lab experiments, or first-principles calculations [9]. The target variable (property) and relevant descriptors (features) must be defined.

Feature Engineering: This critical step involves preparing and optimizing the input features for modeling [9]. It includes:

- Feature Preprocessing: Handling missing values, and normalizing or standardizing data to unify metrics [9].

- Feature Selection & Dimensionality Reduction: Removing redundant descriptors or reorganizing them into a lower-dimensional space using methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to improve model performance and avoid the "curse of dimensionality" [9].

Model Selection and Evaluation: Choosing an algorithm based on the problem type (regression/classification), data size, and complexity. Models must be evaluated using rigorous validation schemes that account for dataset redundancy, such as cluster-based cross-validation, to ensure realistic performance estimates [5] [9].

Model Application: Using the trained and validated model to predict properties of new, unknown materials or to guide experimental synthesis efforts [9].

Critical Experimental Consideration: Controlling Dataset Redundancy

A key methodological advancement is the recognition that standard random splitting of material datasets leads to over-optimistic performance estimates. The MD-HIT algorithm was developed to address this by controlling redundancy in material datasets, ensuring no two samples in the training and test sets are overly similar [5]. Using such tools provides a more objective evaluation of a model's true prediction capability, especially for extrapolation to novel material classes [5]. The "leave-one-cluster-out" cross-validation (LOCO CV) is another method that provides a more objective evaluation of a model's extrapolation performance [5].

Beyond algorithms, a successful ML project in materials science relies on a suite of data, software, and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to ML Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project [1] [5] [7] | Data Repository | Provides computed properties for over 150,000 inorganic compounds and crystal structures. | Source of training data for predicting formation energy, band gaps, and other electronic properties. |

| OQMD [1] [5] | Data Repository | Open Quantum Materials Database containing DFT-calculated thermodynamic and structural properties. | Large-scale dataset for training and benchmarking ML models for material stability and properties. |

| MD-HIT [5] | Software Tool | Algorithm for redundancy control in material datasets before splitting into training/test sets. | Critical for objective model evaluation; prevents overestimation of predictive performance. |

| VASP [7] | Simulation Software | First-principles quantum mechanics package using Density Functional Theory (DFT). | Generates high-fidelity training data (e.g., electronic charge density, formation energies). |

| Electronic Charge Density [7] | Physically-Grounded Descriptor | Real-space distribution of electrons, uniquely determined by the external potential (Hohenberg-Kohn theorem). | Used as a universal input descriptor for predicting diverse material properties from a single source. |

| Matminer [5] | Software Library | Python library for data mining and feature extraction from materials data. | Facilitates feature engineering by generating a wide array of composition and structure-based descriptors. |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores that there is no single "best" machine learning algorithm for all material property prediction tasks. The selection hinges on multiple factors, including the property of interest, data volume and quality, material representation (descriptor), and computational resources.

While classical algorithms like Random Forest and SVM remain dominant and highly effective for many tasks, particularly with smaller or tabular datasets [3] [2], neural networks, especially Graph Neural Networks, have shown remarkable performance in capturing complex structure-property relationships in crystals, albeit with greater data and computational demands [3] [5]. The most promising future direction lies in the development of hybrid models that integrate physical principles with data-driven ML approaches, offering both speed and interpretability [10].

Progress in this field will be accelerated by prioritizing modular AI systems, standardized FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data, and cross-disciplinary collaboration [10]. By carefully selecting algorithms based on the problem context and employing rigorous experimental protocols—especially those that control for dataset redundancy—researchers can fully leverage machine learning to accelerate the discovery and development of next-generation materials.

The discovery and development of new materials are fundamental to technological progress, spanning industries from aerospace to energy storage. Traditional methods relying on experimental trial-and-error or computationally intensive ab initio calculations have created bottlenecks in this innovation pipeline. In response, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative tool, enabling the rapid prediction of material properties and accelerating the design of novel substances. This guide provides a comparative validation of ML algorithms, objectively assessing their performance in predicting three critical classes of material properties: tensile strength, formation energy, and phase stability. We summarize quantitative performance data, detail experimental methodologies, and visualize the logical frameworks that underpin this rapidly advancing field, offering researchers a clear overview of the current prediction landscape.

Comparative Performance of ML Algorithms for Property Prediction

The efficacy of machine learning varies significantly depending on the target material property, the available data, and the chosen algorithm. The following tables provide a structured comparison of model performance across different prediction tasks, based on recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Performance of ML Algorithms for Tensile Strength Prediction

| Material System | ML Algorithm | Performance Metrics | Key Input Features | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (NFRP) Composites | Random Forest (RF) | R² = 0.92, MAE = 1.64 | Epoxy content, density, elastic modulus, curing agent, resin consumption | [11] |

| NFRP Composites | Gradient Boosting | Not Specified (2nd best after RF) | Matrix-filler ratio, surface density | [11] |

| NFRP Composites | XGBoost | Not Specified | Same as above | [11] |

| NFRP Composites | Polynomial Regression | Not Specified | Same as above | [11] |

| Nano-engineered Concrete | Hybrid Ensemble Model (HEM) | Best performance in K-fold CV | Water-cement ratio, curing time, nano-clay, basalt fiber, superplasticizer | [12] |

| Nano-engineered Concrete | Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Second-best performance | Cement content, fine/coarse aggregates, carbon nanotubes | [12] |

Table 2: Performance of ML and AI Models for Formation Energy and Phase Stability

| Prediction Task | Model/Method | Performance Metrics | Key Input/Descriptors | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy (from structure & composition) | AI/Deep Transfer Learning (IRNet) | MAE = 0.064 eV/atom (on experimental test) | Materials structure and composition | [13] |

| Formation Energy | DFT-Computations (OQMD, Materials Project) | MAE = 0.078 - 0.133 eV/atom (vs. experiment) | First-principles calculations | [13] |

| Phase Stability (High-Entropy Ceramics) | Ab Initio Free Energy Model | Agrees with available experimental data | Free energy terms from first-principles | [14] |

| Phase Stability (High-Entropy Ceramics) | Descriptor-based (EFA, DEED) | Relies on empirical correlation thresholds | Enthalpy distribution, entropy descriptor | [14] |

| Phase Diagrams (Alloys) | ML Interatomic Potentials (Grace Model) | Good agreement with VASP & experiment | Structure, composition | [15] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Predicting Tensile Strength of Novel Composites

A study on Natural Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (NFRP) composites provides a reproducible, data-driven framework for tensile strength prediction. The methodology involved several key stages [11]:

- Dataset Curation: Utilizing publicly available datasets containing parameters such as epoxy group content, density, elastic modulus, curing agent amount, resin consumption, surface density, and matrix–filler ratio.

- Feature Selection: Systematically removing weakly correlated features to enhance model accuracy and interpretability, a step noted as an improvement over prior works.

- Model Training and Validation: Five regression algorithms—Polynomial Regression, Bagging Regression, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Gradient Boosting—were trained and evaluated using five-fold cross-validation.

- Performance Evaluation: Models were judged using standard error metrics, including the Coefficient of Determination (R²) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE).

Achieving Experimental-Level Formation Energy Prediction

A significant challenge in materials informatics is that models trained on Density Functional Theory (DFT) data inherit its inherent discrepancies from experimental ground truth. One groundbreaking protocol demonstrated how to surpass DFT-level accuracy [13]:

- Leveraging Deep Transfer Learning: A deep neural network (IRNet) was first pre-trained on a large source domain of DFT-computed data from databases like the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) and Materials Project (MP). This allowed the model to learn a rich set of domain-specific features from material structures and compositions.

- Fine-Tuning on Experimental Data: The pre-trained model was then fine-tuned on a smaller, more accurate target domain of experimental formation energy observations.

- Hold-out Test Validation: The final model was evaluated on an experimental hold-out test set containing 137 entries, where it achieved a lower MAE than DFT computations themselves.

Physics-Based vs. Descriptor-Based Phase Stability Prediction

For high-entropy ceramics, phase stability prediction has historically relied on descriptor-based methods. A comparative protocol highlights a shift towards physics-based models [14]:

- Descriptor-Based Approach: Methods like the Entropy Forming Ability (EFA) and the disordered enthalpy–entropy descriptor (DEED) calculate descriptors from ab initio calculations. These descriptors are empirically correlated with phase stability, and their threshold values for stability are determined self-consistently from existing experiments.

- Physics-Based Free Energy Model: This approach directly calculates the Gibbs free energy, ΔG = ΔH - TΔS, for the high-entropy phase relative to competing phases.

- ΔH (Enthalpy): Calculated using DFT with respect to the most stable competing phases on the convex hull from materials databases.

- ΔS (Entropy): Calculated using the ideal mixing approximation.

- Experimental Synthesis and Validation: The predictions of the free energy model were validated against available literature data. In one case of disagreement, a new sample was synthesized via arc-melting and characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD) to confirm the model's accuracy [14].

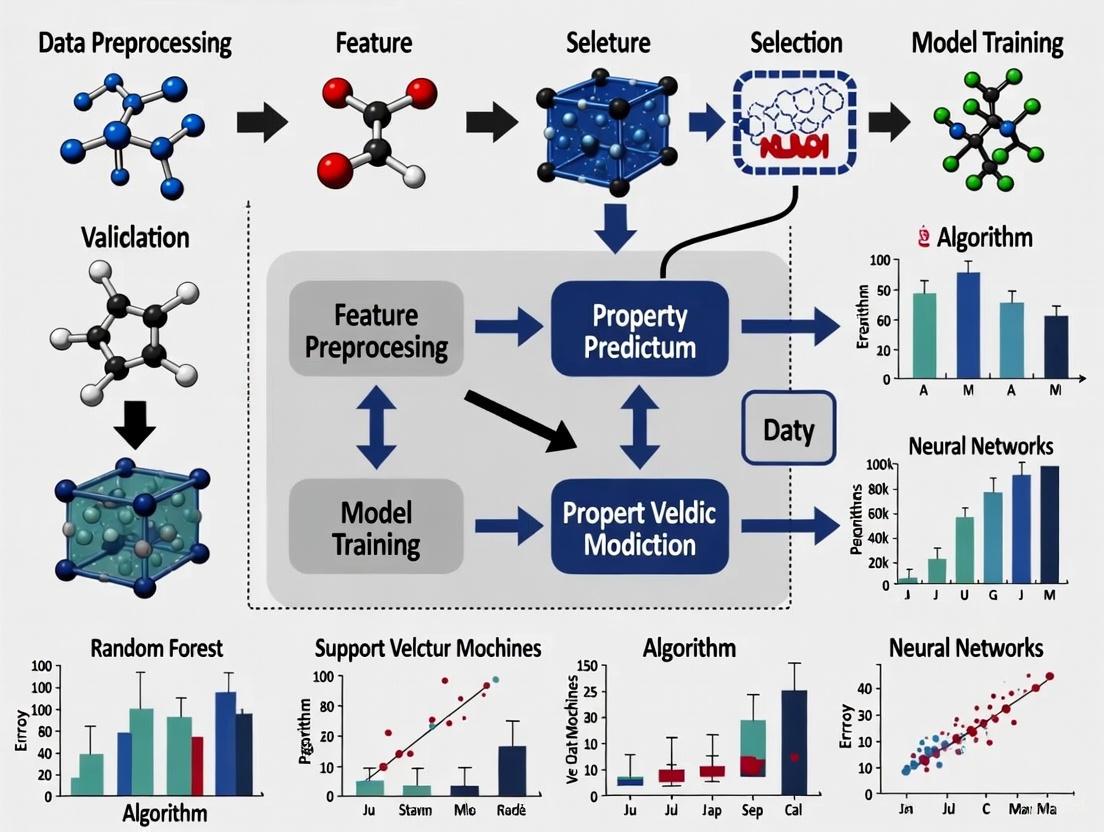

Visualization of Workflows and Logical Frameworks

ML Property Prediction and Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for developing and validating ML models for material property prediction, integrating common elements from the cited studies.

ML Workflow for Material Property Prediction

Algorithm Performance Comparison Framework

This diagram outlines a logical framework for comparing and benchmarking different types of algorithms, from traditional to modern ML approaches, based on their application to specific property prediction tasks.

Algorithm Performance by Prediction Task

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

In the context of computational materials science, "research reagents" refer to the essential software, datasets, and computational tools that enable predictive modeling.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for ML-Based Material Prediction

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) | Database | Source of DFT-computed formation energies and other properties for training ML models. | [13] |

| Materials Project (MP) | Database | A repository of inorganic compounds and their computed properties for high-throughput materials analysis. | [13] [16] |

| VASP (Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package) | Software | Performs first-principles DFT calculations to generate accurate training data and validate model predictions. | [13] [14] [15] |

| ATAT (Alloy Theoretic Automated Toolkit) | Software | Used for generating special quasirandom structures (SQS) and building cluster expansions for alloy phase stability analysis. | [14] [15] |

| MD-HIT | Algorithm | Controls dataset redundancy by ensuring similarity among samples is below a threshold, preventing overestimated performance. | [5] |

| IRNet | Model Architecture | A deep neural network used for predicting formation energy from material structure and composition. | [13] |

| Grace, CHGNet, SevenNet | Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | ML-based force fields that bridge quantum-mechanical accuracy with the efficiency needed for large-scale thermodynamic modeling. | [15] |

Critical Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, the field must overcome several challenges to realize the full potential of ML in materials discovery. A primary issue is dataset redundancy and overestimation of model performance. Materials databases often contain many highly similar structures due to historical "tinkering" in material design. When datasets are split randomly for validation, this redundancy leads to information leakage and over-optimistic performance metrics that do not reflect a model's true power to predict genuinely novel materials [5]. New evaluation methods like k-fold-m-step forward cross-validation (kmFCV) have been proposed to more rigorously assess a model's "explorative power" for outlier discovery [16]. Furthermore, models that perform well in interpolation often fail at out-of-distribution (OOD) extrapolation, which is critical for discovering materials with properties outside the range of known data [5]. Future efforts will likely focus on developing more robust, explainable, and generalizable models that can reliably guide the synthesis of new materials with targeted properties.

The rapid advancement of machine learning (ML) has revolutionized materials science, enabling the prediction of material properties, the discovery of novel compounds, and the optimization of material structures with unprecedented speed [17]. However, the accuracy, generalizability, and ultimate success of any ML model in materials property prediction are fundamentally constrained by the quality, quantity, and characteristics of the underlying training data [5] [18]. The materials informatics community now recognizes that sophisticated algorithms alone cannot overcome the limitations of poorly curated datasets. This comparative guide examines the foundational datasets and data-centric methodologies that drive reliable ML predictions, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate data resources and implementing best practices for data management in their computational materials research.

Major Public Databases for Materials Property Prediction

Table 1: Major Public Databases for Materials Property Prediction

| Database Name | Data Size | Key Properties | Primary Features | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project (MP) | >130,000 entries | Formation energy, band gap, elastic moduli [19] | Crystal structures, computed properties [17] | Contains redundant materials due to historical tinkering approach [5] |

| Alexandria | >5 million calculations | Multiple DFT-calculated properties [18] | DFT calculations for periodic compounds | Open database; enables training on large, consistent datasets [18] |

| Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) | 304,433+ entries | Formation energy, stability [20] | Computational database focusing on material stability | Used in pretraining pipelines like Roost [20] |

| Matbench | 408,065+ data points across tasks [20] | Diverse properties from multiple sources | Curated benchmarking suite | Standardized evaluation for ML models [21] |

| AFLOW | Varies by property | Band gap, bulk modulus, Debye temperature, thermal properties [21] | High-throughput computational data | Contains properties from automated calculations [21] |

Dataset Characteristics Impacting Model Performance

The performance of ML models in materials property prediction is significantly influenced by several key dataset characteristics that researchers must consider during experimental design:

Data Redundancy: Materials databases often contain many highly similar materials due to historical "tinkering" approaches in material design [5]. For example, the Materials Project database contains numerous perovskite cubic structures similar to SrTiO₃ [5]. This redundancy causes random splitting of datasets to yield over-optimistic performance estimates, as models effectively perform interpolation rather than true prediction [5].

Data Scarcity: For many material properties, limited data availability poses significant challenges. Examples include GW-computed band gaps for approximately 80 crystals, lattice thermal conductivity for about 101 compounds, and vibrational properties for around 1,245 materials [19]. This scarcity necessitates specialized approaches like feature selection, transfer learning, and multi-task learning [19] [22].

Data Quality and Physical Relevance: Recent research demonstrates that training data informed by physical principles (such as lattice vibrations or phonons) consistently outperforms randomly generated datasets, even with fewer data points [23]. Physically informed models prioritize chemically meaningful bonds and demonstrate enhanced predictive accuracy [23].

Experimental Protocols for Data-Centric ML in Materials Science

The MODNet Framework for Limited Data Scenarios

The Materials Optimal Descriptor Network (MODNet) represents a sophisticated approach to addressing data scarcity through feature selection and joint learning [19]. The experimental protocol involves:

Feature Representation: Raw crystal structures are transformed into physically meaningful descriptors using the matminer package, which covers elemental, structural, and site-related features grounded in physical and chemical intuition [19].

Feature Selection Process: MODNet employs a relevance-redundancy (RR) selection algorithm based on Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) [19]. The process begins by selecting the feature with the highest NMI with the target variable. Subsequent features are chosen using the RR score:

RR(f) = NMI(f,y) / [max(NMI(f,f_s))^p + c], wherepandcare hyperparameters that balance relevance and redundancy [19].Joint-Learning Architecture: MODNet uses a tree-like neural network architecture where initial layers are shared across multiple properties, and specialized branches handle specific properties. This approach enables knowledge transfer between related properties, effectively increasing the virtual dataset size [19].

MD-HIT for Dataset Redundancy Control

The MD-HIT algorithm addresses dataset redundancy through a systematic protocol [5]:

Problem Identification: The method first identifies that random splitting of materials datasets leads to overestimated performance because highly similar materials may appear in both training and test sets [5].

Redundancy Reduction: MD-HIT applies similarity thresholds to ensure no two materials in the training and test sets exceed a structural or compositional similarity threshold, analogous to CD-HIT used in bioinformatics for protein sequence analysis [5].

Performance Evaluation: Models are evaluated on truly distinct materials, providing a more realistic assessment of predictive capability, particularly for out-of-distribution samples [5].

Ensemble of Experts for Severe Data Scarcity

For extreme data limitation scenarios, the Ensemble of Experts (EE) approach provides a robust methodology [22]:

Expert Pretraining: Multiple "expert" models are first pretrained on large, high-quality datasets for different but physically related properties [22].

Fingerprint Generation: These experts generate molecular fingerprints that encapsulate essential chemical information, using tokenized SMILES strings to enhance chemical structure interpretation compared to traditional one-hot encoding [22].

Transfer Learning: The pretrained knowledge is transferred to predict complex target properties (e.g., glass transition temperature Tg or Flory-Huggins parameter χ) even with very limited training data (as few as 20 samples) [22].

Data Ecosystem for Material Property Prediction

Comparative Analysis of Data-Driven Methodologies

Performance Across Data Scarcity Conditions

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Data-Centric ML Approaches

| Methodology | Optimal Data Scenario | Key Advantages | Reported Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MODNet | Small to medium datasets (hundreds to thousands of samples) | Feature selection reduces dimensionality; joint learning enables multi-property prediction [19] | Predicts vibrational entropy at 305K with MAE of 0.009 meV/K/atom (4x lower than previous studies) [19] | Requires careful feature engineering; performance plateaus with very large datasets |

| Ensemble of Experts (EE) | Severe data scarcity (as few as 20 samples) [22] | Leverages transfer learning from related properties; tokenized SMILES improve chemical interpretation [22] | Significantly outperforms standard ANNs under severe data scarcity; better generalization across molecular structures [22] | Dependent on availability of relevant pretraining data; complex implementation |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Large datasets (>100,000 samples) [18] | Automatically learns material representations from structure; high accuracy with sufficient data [18] | Error decreases monotonically with training data size; generally more accurate than composition-based methods [18] | Performance saturates for some architectures; requires structural information |

| E2T (Extrapolative Episodic Training) | Out-of-distribution prediction [24] | Specifically designed for extrapolation beyond training distribution; meta-learning approach [24] | Improves extrapolative precision by 1.8× for materials and 1.5× for molecules [21] | Complex training regimen; requires careful task design |

Addressing Dataset Redundancy: A Comparative Study

The critical issue of dataset redundancy and its impact on model evaluation merits particular attention. Studies demonstrate that when MD-HIT is applied to reduce redundancy in composition- and structure-based formation energy and band gap prediction problems, models show relatively lower performance on test sets compared to evaluations with high redundancy, but these metrics better reflect true predictive capability [5]. This phenomenon explains why models achieving seemingly DFT-level accuracy (e.g., MAE of 0.064 eV/atom for formation energy) on randomly split test sets often fail to maintain this performance on truly novel material families [5]. Leave-one-cluster-out cross-validation (LOCO CV) provides a more rigorous evaluation framework, revealing that current ML models struggle significantly with generalization from training clusters to distinct test clusters [5].

Dataset Splitting Impact on Model Evaluation

Key Computational Tools and Datasets

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Materials Informatics

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| matminer | Feature generation library | Provides physically meaningful material descriptors [19] | Feature engineering for traditional ML models |

| MD-HIT | Data preprocessing algorithm | Controls dataset redundancy by ensuring similarity thresholds [5] | Preparing robust train/test splits for model evaluation |

| Roost | Structure-agnostic model | Predicts properties from stoichiometry alone [20] | High-throughput screening when crystal structures are unavailable |

| Barlow Twins Framework | Self-supervised learning method | Pretrains models without labeled data [20] | Leveraging unlabeled data to improve downstream task performance |

| Magpie Fingerprint | Fixed-length descriptor | Engineered material representation based on elemental properties [20] | Baseline features for composition-based property prediction |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that strategic data management is equally important as algorithmic sophistication in materials informatics. The most successful approaches combine physically informed data curation with methodologies specifically designed to address fundamental challenges like data scarcity, redundancy, and distribution shifts. Researchers should select datasets and methodologies aligned with their specific prediction goals: MODNet for limited datasets with multiple related properties, Ensemble of Experts for extreme data scarcity, Graph Neural Networks for data-rich scenarios with available structural information, and E2T for extrapolative prediction tasks. As the field evolves, emerging strategies like self-supervised pretraining and physically informed data generation promise to further enhance data efficiency, ultimately accelerating the discovery of novel materials with tailored functionalities.

Selecting the right machine learning algorithm is a cornerstone of successful materials science research. The choice between simpler models like Linear Regression and more complex architectures like Neural Networks can significantly impact the accuracy, interpretability, and computational cost of your property predictions. This guide provides a comparative validation of these algorithms to inform researchers and development professionals in their experimental design.

The foundational models for material property prediction span a spectrum from simple, interpretable statistical methods to complex, non-linear learning systems.

Linear Regression (LR) models a linear relationship between input variables (e.g., material composition, processing parameters) and a target property (e.g., formation energy, band gap). It is often extended to Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) for handling multiple features [25]. The model assumes that the target variable ( y ) can be expressed as a linear combination of the input features ( xn ), as shown in the equation ( {\text{y}} = {\text{w}}{0} + {\text{w}}{{1}} {\text{x}}{{1}} + \cdots + {\text{w}}{{\text{n}}} {\text{x}}{{\text{n}}} ), where ( w ) represents the coefficients [25]. Its simplicity, computational efficiency, and high interpretability make it a strong baseline model.

Random Forest Regression (RFR) is an ensemble method that constructs a multitude of decision trees during training and outputs the average prediction of the individual trees [25]. This technique is robust against overfitting and is particularly effective at capturing complex, non-linear relationships and interactions between input variables without requiring extensive feature scaling [25] [17].

Neural Networks (NNs), especially Deep Learning architectures, are highly flexible models composed of interconnected layers of neurons. They learn hierarchical representations of data, making them powerful for capturing intricate patterns in high-dimensional spaces [25] [17]. Specific types like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) excel with sequential data, while Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are increasingly used for crystal structure data [25] [17]. A fundamental neural network layer without non-linear activation functions is essentially a multiple linear regression [26].

Performance Comparison in Material Property Prediction

Experimental data from published studies consistently demonstrates a trade-off between model complexity and predictive performance. The following table summarizes quantitative comparisons for predicting various material properties.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ML Algorithms in Materials Science

| Material Property | Algorithm | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Ozone Concentration [25] | Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) | R²: 0.8902, RMSE: 24.91, MAE: 19.16 | Outperformed other models with 81.44% prediction accuracy. |

| Linear Regression (LR) | Details not provided in context | Simpler modeling technique, outperformed by Neural Networks. | |

| Random Forest Regression (RFR) | Details not provided in context | Robust ensemble technique, outperformed by Neural Networks. | |

| Formation Energy & Band Gap [5] | Various ML Models (with random split) | Reported high R² | Performance is often overestimated due to dataset redundancy. |

| Various ML Models (with redundancy control) | Relatively lower performance | Better reflects the model's true extrapolation capability. | |

| Biochemical/Chemical Oxygen Demand [27] | Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | RMSE: 25.1 mg/L (BOD), r: 0.83 | Performance was better than the MLR model. |

| Multivariate Linear Regression (MLR) | RMSE: 49.4 mg/L (COD), r: 0.81 | Performance was worse than the ANN model. | |

| Bulk Modulus, Shear Modulus [28] | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | High accuracy for Bulk Modulus | Emerged as particularly effective. |

| Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) | Strong performance across various properties | Demonstrated robust performance as an ensemble method. |

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Validation

A rigorous comparison of algorithms requires a standardized experimental protocol to ensure fair and reproducible results. The following workflow outlines a typical process for benchmarking models in material property prediction.

Diagram 1: Algorithm benchmarking workflow.

Data Sourcing and Pre-processing

The initial phase involves curating a high-quality dataset, which forms the foundation for all subsequent modeling.

- Data Collection: Utilize large-scale materials databases such as the Materials Project, AFLOW, and the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) [5] [29]. These provide computed properties like formation energy and band gap for thousands of inorganic compounds.

- Data Cleaning: Address inconsistencies, missing values, and noise in the raw data. Common techniques include:

- Critical Consideration - Redundancy Control: Materials databases often contain many highly similar structures due to historical "tinkering" in material design. A random train-test split on such data leads to over-optimistic performance estimates and poor generalization. Employ algorithms like MD-HIT to create non-redundant benchmark datasets, ensuring a more realistic evaluation of a model's true predictive capability, especially for out-of-distribution samples [5].

Feature Engineering and Dataset Splitting

This stage prepares the clean data for the learning algorithms.

- Feature Engineering: Transform raw material representations (e.g., chemical composition, crystal structure) into numerical descriptors. This can be done via:

- Manual Feature Selection: Using domain knowledge to select features like electronic properties (band gap, electron affinity) or crystal features (radial distribution functions) [29].

- Automated Feature Engineering: Leveraging the model itself to learn relevant representations, as seen in Graph Neural Networks that automatically extract features from crystal graphs [17].

- Dataset Splitting: Divide the dataset into training, validation, and test sets. To properly evaluate extrapolation performance, use methods like:

Model Training and Performance Evaluation

The core of the experimental protocol where algorithms are built and assessed.

- Model Training: Train a diverse set of algorithms on the pre-processed training data. This typically includes:

- Performance Evaluation: Quantify model performance on the held-out test set using standard metrics:

Table 2: Essential Tools and Datasets for Material Property Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Project [29] | Database | Provides computed properties (formation energy, band gap) for over 150,000 materials for training models. |

| AFLOW [21] [29] | Database | A large repository of calculated material compounds and properties for high-throughput screening. |

| Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) [5] [29] | Database | Contains DFT-calculated thermodynamic and structural properties of more than a million materials. |

| MD-HIT [5] | Algorithm | Controls dataset redundancy to avoid overestimated performance and improve model generalizability. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [17] | Algorithm | Directly learns material representations from crystal structure data for highly accurate property prediction. |

| Bilinear Transduction [21] | Algorithm | A transductive method that improves extrapolation precision for predicting out-of-distribution property values. |

Decision Framework and Special Considerations

The choice of algorithm is not one-size-fits-all; it depends on the project's specific goals, constraints, and data characteristics. The following decision pathway provides a logical framework for selection.

Diagram 2: Algorithm selection guide.

Navigating the Accuracy vs. Interpretability Trade-off

The core trade-off in algorithm selection often lies between predictive accuracy and model interpretability.

- Prioritize Interpretability with Linear Models: If the research goal is to understand the fundamental physical relationship between a few key variables (e.g., the effect of temperature and pressure on a property), or if the dataset is small, Linear Regression is the most suitable choice. Its coefficients provide direct, quantifiable insights into feature importance [25] [26].

- Balance Complexity and Performance with Ensemble Methods: Random Forest offers a strong middle ground. It provides better accuracy than linear models for complex, non-linear relationships and can output feature importance scores, though its internal mechanics are less transparent than a linear model [25] [28].

- Maximize Accuracy with Neural Networks: When the primary objective is maximum predictive accuracy for a complex problem (e.g., predicting properties from raw crystal structures) and a large amount of data is available, Neural Networks (particularly GNNs and RNNs) are the state-of-the-art [25] [17]. However, they function as "black boxes" and require significant computational resources.

The Critical Challenge of Out-of-Distribution Prediction

A key challenge in materials discovery is identifying materials with exceptional, out-of-distribution (OOD) properties.

- The Problem: Models trained for interpolation often fail at extrapolation. A model accurate for predicting average band gaps may perform poorly when searching for materials with ultra-high or ultra-low band gaps [5] [21].

- Solutions and Specialized Algorithms:

- Rigorous Dataset Splitting: As noted in the experimental protocol, using methods like LOCO CV is essential for a truthful evaluation of OOD performance [5].

- Advanced Architectures: New methods like Bilinear Transduction are specifically designed for OOD extrapolation. This approach learns how property values change as a function of material differences, improving precision in identifying high-performing candidates by up to 1.8x for materials [21].

The journey from Linear Regression to Neural Networks is one of increasing model capacity and complexity. This guide demonstrates that while advanced neural networks often achieve superior predictive accuracy, the optimal algorithm is context-dependent. For interpretable insights from small datasets, Linear Regression remains a powerful tool. For robust handling of non-linear relationships, Random Forest is an excellent choice. Finally, for large-scale, complex prediction tasks where accuracy is paramount, Neural Networks are currently unmatched. The emerging focus on overcoming dataset redundancy and improving out-of-distribution prediction will undoubtedly shape the next generation of algorithms, further empowering researchers in the accelerated discovery of new materials.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Material Property Prediction

Ensemble machine learning methods have emerged as superior tools for predicting the tensile strength of composite materials, offering significant advantages over traditional experimental methods and single-model algorithms. This comparative analysis synthesizes findings from recent peer-reviewed studies (2024-2025) that systematically evaluated multiple ensemble approaches including Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, XGBoost, and stacked ensembles. The consensus across research indicates that ensemble methods consistently achieve R² values exceeding 0.90 for tensile strength prediction, dramatically reducing computational time from hours to seconds while maintaining high accuracy. Random Forest emerges as the most consistently high-performing algorithm across multiple composite systems, though optimal algorithm selection depends on specific composite characteristics and dataset size.

Performance Benchmarking of Ensemble Methods

Experimental data from recent studies demonstrate the clear performance advantages of ensemble methods over conventional approaches and single models for tensile strength prediction in various composite systems.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ML Algorithms for Tensile Strength Prediction

| Composite System | Best Algorithm | R² Score | MAE | RMSE | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (NFRP) | Random Forest | 0.92 | 1.64 | - | [11] |

| Hybrid PP (Flax/Basalt/Rice Husk) | Stacked Ensemble (SVR+XGBoost) | 0.907 | - | 1.569 MPa | [30] |

| Hybrid Natural Fiber Composites | Random Forest | 0.968 | - | - | [31] |

| CFRP Composites | Random Forest | 0.966 (Flexural) | - | - | [32] |

Table 2: Computational Efficiency Comparison

| Methodology | Simulation/Prediction Time | Speed Improvement | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Finite Element Analysis | 34.5 seconds | 1x (Baseline) | Composite laminates [8] |

| Regression Neural Network | 0.6 seconds | 57.5x | Composite laminates [8] |

| Machine Learning Model | 0.5 seconds | 3600x | Composite mechanical properties [32] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The foundational step across all studies involves systematic data collection and preprocessing to ensure model reliability:

Data Sources: Experimental datasets are generated through standardized mechanical testing (e.g., ASTM D638) with sample sizes typically ranging from n=65 to n=62 specimens [30] [32]. Additional data is sourced from molecular dynamics simulations with classical interatomic potentials and finite element modeling [33] [34].

Feature Selection: Input parameters commonly include material composition (fiber type, matrix type, weight percentages), structural parameters (layer orientation, fiber volume fraction), and processing conditions (manufacturing pressure, curing parameters) [11] [32]. Feature importance analysis reveals that fiber content and interfacial bonding parameters typically dominate predictive models.

Data Preprocessing: Studies consistently apply preprocessing techniques including Savitzky-Golay denoising for signal smoothing, feature standardization (StandardScaler), and five-fold or ten-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting [33] [30]. For image-based microstructural data, convolutional neural networks utilize raw microstructure images with minimal preprocessing [34].

Algorithm Implementation and Training

The implementation of ensemble methods follows rigorous optimization protocols:

Hyperparameter Tuning: Studies employ systematic hyperparameter optimization using Grid Search [33] or Optuna framework [30] with cross-validation to identify optimal model configurations.

Ensemble Architectures: Three primary ensemble architectures are implemented: (1) Bagging (Random Forest), (2) Boosting (Gradient Boosting, XGBoost, AdaBoost), and (3) Stacking (linear combination of multiple algorithms) [11] [33] [30].

Validation Methodology: Studies implement k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5 or k=10) with strict separation of training and testing sets to ensure generalizability. Performance metrics including R², MAE, RMSE, and computational time are systematically reported [11] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Table 3: Critical Research Tools for Ensemble Prediction of Composite Properties

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function/Application | Representative Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | Scikit-Learn | Implementation of ensemble algorithms (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) | Regression tree ensembles for carbon allotropes [33] |

| MATLAB R2024 | Neural network implementation and simulation | Regression Neural Network for composite laminates [8] | |

| XGBoost Library | Optimized gradient boosting implementation | Stacked ensembles for hybrid PP composites [30] | |

| Simulation & Analysis | DIGIMAT-VA Software | Composite laminate behavior simulation | Generating training data for ML models [8] |

| LAMMPS | Molecular dynamics simulations | Calculating formation energy and elastic constants [33] | |

| Finite Element Analysis | Virtual testing of composite performance | Generating ground truth data for CNN training [34] | |

| Optimization Tools | Optuna Framework | Hyperparameter tuning for ML models | Optimizing SVR and XGBoost parameters [30] |

| SHAP Analysis | Model interpretability and feature importance | Explaining compressive strength predictions [35] |

Comparative Algorithm Performance Analysis

Performance Across Composite Systems

The efficacy of ensemble methods extends across diverse composite material systems:

Natural Fiber Composites: Random Forest achieves exceptional prediction accuracy (R² = 0.92) for tensile strength of natural fiber-reinforced polymer composites, successfully capturing complex interactions between epoxy group content, density, elastic modulus, curing parameters, and matrix-filler ratio [11]. Feature importance analysis reveals that matrix-filler ratio and elastic modulus are the most significant predictors.

Hybrid Polymer Composites: Stacked ensemble approaches combining Support Vector Regression (SVR) and XGBoost with a linear meta-learner demonstrate superior performance (R² = 0.907) for predicting tensile strength of hybrid polypropylene composites reinforced with flax, basalt, and rice husk powder [30]. This approach effectively captures nonlinear interactions between the three reinforcement types.

CFRP Composites: For carbon fiber reinforced polymers, Random Forest achieves outstanding accuracy (R² = 0.966) in predicting flexural strength based on features including carbon nanotube volume fraction, interlayer volume fraction, glass transition temperature, and manufacturing pressure [32].

Interpretation and Explainability

Advanced ensemble methods incorporate explainability features to bridge the gap between prediction and physical understanding:

SHAP Analysis: Shapley Additive exPlanations quantitatively assess feature importance, revealing that fiber content and interfacial bonding parameters typically dominate tensile strength predictions [35]. For rubberized concrete, SHAP analysis identified waste tyre rubber content as the most influential factor with a mean SHAP value of 3.83, significantly higher than other factors [35].

Feature Attribution: Convolutional Neural Networks with Integrated Gradients identify critical microstructural features (fiber arrangement, matrix distribution) that influence composite performance, enabling engineers to verify that models learn physically meaningful patterns [34].

Ensemble machine learning methods, particularly Random Forest and strategically stacked ensembles, establish a new paradigm for efficient and accurate prediction of tensile strength in composite materials. The consistently high performance (R² > 0.90) across diverse composite systems, coupled with dramatic reductions in computational time (up to 3600x faster than finite element analysis), positions these methods as transformative tools for composite design and development. The integration of explainable AI techniques further enhances the utility of these approaches by providing physical insights into feature-property relationships. Future advancements will likely focus on expanding multi-property prediction frameworks, integrating real-time manufacturing data, and developing more sophisticated transfer learning approaches to accelerate the development of next-generation composite materials.

The discovery and development of advanced metallic alloys are crucial for technological progress in aerospace, electronics, and energy sectors. Traditional alloy design, which relies on a single principal element with minor additions, is increasingly reaching its performance limits. In recent years, two innovative classes of materials have emerged as promising alternatives: metallic glasses (MGs), also known as amorphous metals, and high-entropy alloys (HEAs) [36].

Metallic glasses are characterized by their non-crystalline, amorphous atomic structure, which results from rapid solidification that prevents atomic ordering. This unique structure confers exceptional properties, including high strength, excellent corrosion resistance, and superior elasticity [37] [38]. The global metallic glasses market, valued at approximately USD 1.9 billion in 2025, reflects their growing industrial importance, with projections reaching USD 3.0-3.6 billion by 2032-2035 [37] [38].

High-entropy alloys represent a paradigm shift in alloy design, comprising multiple principal elements (typically five or more) in near-equiatomic proportions. This multi-principal element approach leads to high configurational entropy and unique phenomena such as severe lattice distortion, sluggish diffusion, and the "cocktail effect" [39] [36]. These characteristics enable exceptional mechanical properties, thermal stability, and corrosion resistance, particularly at elevated temperatures. The global HEA market, valued at USD 1.2 billion in 2024, is expected to reach USD 2.4 billion by 2034 [39].

However, the vast compositional space of these multi-component materials makes traditional trial-and-error discovery approaches impractical. The exploration of MGs and HEAs has thus become a fertile ground for the application of machine learning (ML) techniques, which can efficiently navigate complex compositional spaces and accelerate the prediction of material properties [3] [40] [41]. This case study provides a comparative analysis of ML approaches for forecasting the properties of metallic glasses and high-entropy alloys, examining their respective challenges, methodological frameworks, and performance.

Machine Learning Applications in Metallic Glass Discovery

Prediction Targets and Data Characteristics

The primary prediction target for metallic glasses is the Glass-Forming Ability (GFA), which quantifies an alloy's tendency to form an amorphous structure upon cooling. The most common experimental measure of GFA is the critical casting diameter (Dmax), which represents the maximum thickness that can be solidified without crystallization [41]. Other relevant targets include thermal properties such as glass transition temperature (Tg) and crystallization temperature (Tx).

ML models for metallic glasses typically utilize features derived from several categories [41]:

- Elemental Composition: Molar or atomic fractions of constituent elements

- Thermophysical Properties: Calculated using methods like CALPHAD, including liquidus temperature (Tliq), solidus temperature (Tsol), enthalpy of mixing (ΔHmix), and entropy of melting (ΔSmelt)

- Elemental Descriptors: Features generated by software like Magpie, which computes average elemental properties based on composition

A significant challenge in MG informatics is the limited availability of high-quality experimental data, which constrains the complexity and generalizability of ML models [41].

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Feature-Based GFA Prediction

A representative study by Mastropietro et al. focused on predicting the critical casting diameter (Dmax) of Fe-based metallic glasses using an a priori approach, where predictions are made using only data available prior to synthesis [41]. The experimental protocol involved:

- Data Collection: Compiling a dataset of Fe-based BMG compositions and their corresponding experimentally measured Dmax values from literature.

- Feature Engineering: Creating three distinct feature sets:

- DS1: Molar fractions of alloying elements

- DS2: Thermophysical quantities calculated via CALPHAD method using Thermo-Calc software with the TCHEA3 database

- DS3: Magpie-derived compositional features

- Model Training and Validation: Implementing multiple ML algorithms including Support Vector Machines (SVM), XGBoost, and ensemble methods, evaluated using leave-one-out cross-validation.

- Data Augmentation: Applying the PADRE (PAirwise Difference REgression) method to augment the limited training data and improve model performance.

The best-performing model was an ensemble combining SVM and XGBoost trained on thermophysical and Magpie features, achieving an R² score of 0.69 and MAE of 0.69 for Dmax prediction [41].

Image-Based Spectral Prediction

A groundbreaking approach to MG discovery treats X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra as images, leveraging deep learning models designed for image generation [40]. The experimental workflow comprises:

- Data Acquisition: Synthesizing combinatorial alloy libraries using magnetron co-sputtering and collecting XRD spectra with laboratory diffractometers.

- Data Preprocessing: Subtracting substrate signals, restricting 2θ or q values to a consistent range, normalizing intensities, and standardizing data length through linear interpolation.

- Model Architecture: Implementing a continuous conditional generative adversarial network (ccGAN) incorporating:

- A generator that uses random noise and chemical composition as continuous conditional input to produce synthetic XRD spectra

- A discriminator that evaluates both the quality of generated spectra and the correspondence between compositions and spectra

- Model Training: Training the ccGAN on experimental XRD data, with performance quantified using mean squared error (MSE) between generated and experimental spectra.

This approach demonstrated remarkable data efficiency, achieving accurate spectral generation with as few as 20 training spectra for ternary systems and approximately 100 spectra for quaternary systems [40]. The following diagram illustrates this image-based spectral prediction workflow:

Performance and Limitations

Feature-based ML models for GFA prediction typically achieve test R² values of 0.6-0.7, with better performance for alloys with moderate Dmax values [41]. The image-based approach using ccGAN demonstrates high fidelity in spectral generation, with mean squared error as low as 20 when trained on sufficient data [40].

Key limitations in MG prediction include:

- Data Scarcity: Limited experimental data for complex multi-component systems

- Extrapolation Challenges: Poor performance for alloys with very high GFA (large Dmax)

- Feature Representation: Difficulty in capturing complex many-body interactions using weighted averages of elemental properties [40]

Machine Learning Applications in High-Entropy Alloy Development

Prediction Targets and Data Characteristics

For high-entropy alloys, ML prediction targets focus predominantly on mechanical and thermal properties critical for high-performance applications:

- High-Temperature Strength: Yield strength and specific strength at elevated temperatures

- Creep Resistance: Ability to withstand deformation under mechanical stress at high temperatures

- Oxidation Resistance: Formation of stable oxide layers protecting against degradation

- Phase Stability: Maintenance of desired phase structure under thermal exposure

HEA datasets often incorporate features derived from [39] [36]:

- Alloy Composition: Elemental categories including 3D transition metals, refractory metals, and light metals

- Microstructural Characteristics: Phase composition (FCC, BCC, B2, L12), grain size, and precipitate distribution

- Manufacturing Parameters: Processing methods including casting, powder metallurgy, and additive manufacturing techniques

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Property Prediction via Classical ML

Research on HEAs frequently employs classical machine learning methods for property prediction:

- Data Collection: Compiling datasets from experimental literature and high-throughput computational studies, particularly using density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

- Feature Selection: Utilizing elemental properties (electronegativity, atomic radius, valence electron concentration) and thermodynamic parameters (mixing enthalpy, entropy).

- Model Implementation: Applying algorithms including Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, and neural networks.

- Performance Validation: Using cross-validation and comparison with experimental measurements.

Studies have demonstrated that ML models can successfully predict formation energies, phase selection, and mechanical properties of HEAs. Graph neural network techniques have shown particular promise, achieving a 7-fold reduction in prediction error for formation enthalpy compared to feature-based methods using conventional ML [3].

Additive Manufacturing Integration

The combination of ML with additive manufacturing (AM) represents an emerging frontier in HEA research [39]:

- Process Optimization: Using ML to optimize AM parameters (laser power, scan speed, powder characteristics) for HEA fabrication.

- Microstructure Prediction: Predicting grain morphology and phase distribution in AM-processed HEAs.

- Property Mapping: Correlating process parameters with final mechanical properties.

Performance and Limitations

The performance of ML models for HEA prediction varies significantly with data quality and feature selection. For formation energy prediction, graph neural networks have demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional descriptor-based approaches [3].

Key challenges in HEA informatics include:

- Complex Property Relationships: Non-linear interactions between multiple principal elements

- Processing-Structure Links: Difficulties in capturing the relationship between manufacturing parameters and final properties

- Data Integration: Combining computational and experimental data from diverse sources

Comparative Analysis of ML Approaches

Algorithm Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of different ML algorithms applied to metallic glasses and high-entropy alloys:

Table 1: Machine Learning Algorithm Performance for Material Property Prediction

| Algorithm | Best Suited Applications | Strengths | Limitations | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Classification and regression with moderate-sized datasets [42] | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; memory efficient | Sensitive to parameter tuning; poor performance with noisy data | Test R² ~0.60 for Fe-based BMG Dmax prediction [41] |

| XGBoost | Tabular data with non-linear relationships [41] | Handles missing values; prevents overfitting | Limited extrapolation capability; computationally intensive | Test R² ~0.63 for Fe-based BMG Dmax prediction [41] |

| Random Forests | Datasets with high variability and small effect sizes [42] | Robust to outliers; provides feature importance | Can overfit with noisy data; less interpretable | Superior to kNN for variable data with small effect sizes [42] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Materials with structural or compositional graphs [3] | Captures complex structural relationships | High computational requirements; complex implementation | 7x error reduction for formation enthalpy vs. conventional ML [3] |

| Generative Adversarial Networks | Spectral data and image-based material representation [40] | Generates high-fidelity synthetic data; enables exploration of vast compositional spaces | Training instability; mode collapse issues | MSE ~20 for XRD spectrum generation with 100 training samples [40] |

Experimental Data and Workflow Comparison

The experimental protocols and data requirements differ significantly between metallic glass and HEA prediction:

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Experimental Protocols for Metallic Glasses and High-Entropy Alloys

| Aspect | Metallic Glasses | High-Entropy Alloys |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Prediction Targets | Glass-forming ability (GFA), critical casting diameter (Dmax), thermal properties [41] | Mechanical properties (strength, ductility), phase stability, oxidation resistance [39] [36] |

| Key Experimental Metrics | XRD amorphous structure confirmation, thermal analysis (Tg, Tx) [40] | Tensile/compressive testing, creep resistance, oxidation kinetics [36] |

| Common Features | Composition, thermophysical properties (Tliq, ΔHmix), Magpie descriptors [41] | Composition, elemental properties, processing parameters, phase structure [39] |

| Data Acquisition Methods | Combinatorial sputtering, rapid solidification, thermal analysis [40] | Arc melting, additive manufacturing, mechanical testing, DFT calculations [39] [36] |

| Characterization Techniques | XRD, DSC, TEM [40] | SEM, TEM, XRD, mechanical testing, oxidation testing [36] |

| Primary Challenges | Limited GFA data, extrapolation to high Dmax [41] | Complex composition-property relationships, processing variability [39] |

Cross-Cutting Challenges and Emerging Solutions

Both fields face several common challenges in ML application:

Data Quality and Quantity: The limited availability of high-quality, standardized experimental data remains a significant constraint. Potential solutions include:

- Development of standardized data reporting formats

- Implementation of federated learning approaches across multiple institutions

- Enhanced data augmentation techniques like PADRE [41]

Feature Representation: Effective representation of material composition and structure is crucial for model performance. Promising approaches include:

- Graph-based representations capturing atomic interactions

- Spectral representations treating experimental data as images [40]

- Hierarchical features capturing multi-scale material characteristics

Model Interpretability: The "black box" nature of complex ML models limits physical insights. Solutions include:

- Implementation of explainable AI techniques

- Integration of domain knowledge through physics-informed neural networks

- Feature importance analysis to identify key predictive parameters

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental workflows for metallic glass and HEA development require specialized materials, software, and characterization tools. The following table details key research reagents and their functions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metallic Glass and HEA Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Elements | Zr, Fe, Ti, Cu, Ni, Co, Cr, Al, Nb, Mo, Ta, W [37] [39] [38] | Principal constituents for alloy formation | Fundamental to both MG and HEA composition design |

| Specialized Software | Thermo-Calc (with TCHEA database), Magpie descriptor generator [41] | Thermodynamic calculations, feature generation | Critical for feature engineering in ML workflows |

| ML Frameworks | XGBoost, Scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch [41] [42] | Implementation of ML algorithms and neural networks | Core infrastructure for predictive modeling |

| Characterization Tools | XRD, DSC, SEM/TEM, mechanical testing systems [40] [36] | Structural, thermal, and mechanical characterization | Essential for experimental validation of predictions |

| Manufacturing Equipment | Arc melters, magnetron sputtering systems, 3D printers [39] [40] | Alloy synthesis and sample preparation | Enables experimental fabrication of predicted compositions |

| Computational Resources | DFT codes, molecular dynamics simulations [3] [36] | First-principles property calculation | Generates training data and validates predictions |

Integrated Workflow for ML-Driven Material Discovery

The most effective approaches combine elements from both metallic glass and HEA methodologies. The following diagram presents an integrated workflow for ML-driven discovery of advanced metallic materials:

This integrated workflow highlights the iterative nature of ML-driven material discovery, where experimental validation continuously refines and improves predictive models.

This comparative analysis demonstrates that machine learning has become an indispensable tool for accelerating the discovery and development of both metallic glasses and high-entropy alloys. While these material classes present distinct prediction challenges and require specialized methodological approaches, they share common ground in their reliance on ML to navigate vast compositional spaces.

For metallic glasses, the primary focus remains on predicting glass-forming ability, with innovative approaches like image-based spectral prediction offering promising avenues for enhanced efficiency. For high-entropy alloys, the emphasis lies on optimizing mechanical and thermal properties for extreme environment applications, with growing integration of additive manufacturing processes.

The continued advancement of ML applications in materials science will likely depend on addressing cross-cutting challenges related to data quality, feature representation, and model interpretability. As these fields mature, we anticipate increased convergence of methodologies, with transfer learning approaches enabling knowledge sharing between metallic glass and HEA research domains. The integration of physical principles into ML frameworks, along with the development of more sophisticated multi-scale modeling approaches, will further enhance the predictive power and practical utility of these computational tools.

Ultimately, the synergistic combination of machine learning, computational modeling, and targeted experimental validation represents the most promising path forward for unlocking the full potential of advanced metallic materials, enabling accelerated development of next-generation alloys with tailored properties for specific technological applications.

The accurate prediction of material properties through machine learning (ML) hinges on one critical step: the effective numerical representation of the material's structure and composition. These representations, known as descriptors, serve as the fundamental input for ML models, creating a bridge between the physical world of materials and the computational realm of artificial intelligence. The choice of descriptor significantly influences the model's predictive accuracy, interpretability, and ability to generalize to new, unknown materials. This guide provides a comparative analysis of prevalent descriptor methodologies, evaluating their performance, underlying experimental protocols, and applicability within material property prediction research.

Material descriptors can be broadly categorized as either feature-based (hand-engineered) or learned representations. The table below compares several key descriptors used in modern materials informatics.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Material Descriptor Types

| Descriptor Name | Type | Input Information | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) [43] | Feature-based | Atomic structure & species | High accuracy, incorporates structural symmetry, physics-inspired | Computationally intensive, requires precise atomic coordinates |

| Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) [43] | Feature-based | Atomic structure | High predictive accuracy, body-order expansion | Complex mathematical formulation |

| Atom Centered Symmetry Functions (ACSF) [43] | Feature-based | Local atomic environments | Suitable for neural network potentials, invariant to rotations/translations | May require optimization of function parameters |

| Graph Descriptors [43] [5] | Feature-based / Learned | Crystal structure as a graph | Naturally represents crystal structures, intuitive for periodic systems | Performance can vary; simpler versions may be less accurate |

| Structural Fingerprints (CNA, CSP) [43] | Feature-based | Local atomic structure | Simple, fast to compute, good for classification of atomic environments | Lower predictive accuracy for complex property prediction [43] |

| Stoichiometric Features [21] | Feature-based | Chemical formula only | Simple, does not require structural data, fast to compute | Limited by lack of structural information, may hinder accuracy |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [3] [5] | Learned | Crystal structure as a graph | State-of-the-art accuracy on many tasks, learns features directly from data | "Black-box" nature, requires large datasets, computationally intensive to train |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

The ultimate test for any descriptor is its performance in predicting material properties. The following table summarizes quantitative results from benchmark studies, highlighting the relative effectiveness of different approaches.

Table 2: Experimental Performance of Different Descriptors for Grain Boundary Energy Prediction [43]

| Descriptor | Best Model | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [mJ/m²] | R² Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOAP | LinearRegression | 3.89 | 0.99 |

| ACE | MLPRegression | 4.85 | 0.99 |

| Strain Functional (SF) | MLPRegression | 5.70 | 0.98 |

| ACSF | LinearRegression | 11.44 | 0.92 |

| Graph (graph2vec) | MLPRegression | 22.41 | 0.69 |

| Common Neighbor Analysis (CNA) | LinearRegression | 25.45 | 0.60 |

| Centrosymmetry Parameter (CSP) | LinearRegression | 26.15 | 0.58 |

A broader view of descriptor evolution is seen in formation energy prediction. One analysis noted a dramatic 7-fold reduction in error when moving from feature-based methods using conventional ML to graph neural network techniques [3]. This underscores the significant performance gains possible with advanced, learned representations.

The Critical Issue of Dataset Redundancy and Extrapolation

When evaluating performance data, it is crucial to consider dataset redundancy. Materials databases often contain many highly similar structures, which can lead to over-optimistic performance metrics when models are tested on random splits of data [5]. This is because the model is merely interpolating between similar training examples.

The true challenge lies in extrapolation, or predicting properties for materials that are genuinely novel and structurally different from those in the training set. Performance often drops significantly in such out-of-distribution (OOD) scenarios [21] [5]. For instance, a transductive method called Bilinear Transduction has been developed to improve OOD extrapolation, showing a 1.8x improvement in extrapolative precision for materials and a 3x boost in the recall of high-performing candidates compared to standard methods [21].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows