Chromatin Accessibility and gRNA Efficiency: A Foundational Guide for CRISPR Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how local chromatin accessibility fundamentally influences the efficiency of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing.

Chromatin Accessibility and gRNA Efficiency: A Foundational Guide for CRISPR Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how local chromatin accessibility fundamentally influences the efficiency of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational evidence, explores advanced single-cell methodologies for screening, offers practical strategies for optimizing gRNA design and delivery, and compares validation techniques for assessing editing outcomes. By integrating the latest research, this guide serves as a critical resource for improving experimental success rates in both basic research and therapeutic development, ultimately enabling more reliable and efficient genome engineering.

The Chromatin Barrier: How DNA Packaging Governs CRISPR-Cas9 Access

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is chromatin accessibility and why is it important for CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing?

Chromatin accessibility refers to the physical permissibility of nuclear macromolecules to contact chromatinized DNA. It is primarily determined by the distribution and occupancy of nucleosomes, which are the basic structural units of chromatin consisting of DNA wrapped around a histone core [1] [2]. The genome can be divided into two main types of regions based on this property:

- Open Chromatin (Euchromatin): Characterized by less nucleosome occupancy, these regions are more accessible to DNA-binding proteins. Active regulatory elements like enhancers and promoters are typically found in these open regions [1] [2].

- Closed Chromatin (Heterochromatin): These regions are more compressed, with dense nucleosome packing that restricts access to the DNA [1].

For CRISPR-Cas9, this distinction is critical because the Cas9-sgRNA complex must physically access the target DNA sequence to perform its editing function. Numerous studies have confirmed that gene editing is more efficient in open, euchromatic regions than in closed, heterochromatic regions [3] [4] [5]. When a target site is buried within a nucleosome or located in heterochromatin, the ability of Cas9 to bind and cleave the DNA is significantly reduced [3] [4].

Q2: What experimental methods can I use to profile chromatin accessibility in my cell type?

Several high-throughput methods have been developed to profile chromatin accessibility genome-wide. The table below summarizes the most commonly used techniques.

Table 1: Methods for Profiling Chromatin Accessibility

| Method | Core Principle | Key Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing) | Uses a hyperactive Tn5 transposase to simultaneously fragment and tag accessible DNA with sequencing adapters. | Fast, high signal-to-noise ratio, requires very few cells (compatible with single-cell protocols). | [1] [6] |

| DNase-seq (DNase I hypersensitive sites sequencing) | Relies on the enzyme DNase I to cleave accessible regions of the genome. | Well-established; effectively maps hyper-accessible regions like enhancers and promoters. | [1] [6] |

| MNase-seq (Micrococcal Nuclease sequencing) | Uses MNase to digest DNA, with a preference for linker DNA between nucleosomes. Can map both nucleosome positions and accessible regions depending on enzyme dosage. | Can define nucleosome positioning and occupancy; has a known cleavage bias based on DNA sequence. | [7] [1] |

| FAIRE-seq (Formaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements) | Based on the differential solubility of cross-linked chromatin after sonication; accessible DNA is enriched in the supernatant. | Nuclease-free method. | [1] [6] |

Q3: My gRNA has high predicted efficiency in silico, but editing in cells is poor. Could chromatin accessibility be the issue?

Yes, this is a common experimental hurdle. Computational tools for gRNA design primarily consider sequence composition and specificity, but often do not fully account for the local chromatin environment of the target cell type [7] [5]. A gRNA targeting a sequence with high GC content or one that forms strong secondary structures may already have reduced efficiency [3] [4]. If that target is also located in a nucleosome-dense or heterochromatic region, the editing efficiency can be further diminished to near-undetectable levels [5]. Therefore, it is highly recommended to consult chromatin accessibility data (e.g., from ATAC-seq or DNase-seq) from a relevant cell type or tissue when designing your gRNAs.

Troubleshooting Guide: Low CRISPR-Cas9 Editing Efficiency

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Editing Efficiency Related to Chromatin Context

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solutions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low mutation rate at multiple targets within a gene. | Target gene is located in a transcriptionally silent, heterochromatic region with low inherent accessibility. | 1. Consult chromatin maps: Check available ATAC-seq/DNase-seq data for your cell type to select gRNAs in accessible regions.2. Use chromatin-modulating agents: Co-deliver CRISPR with small molecule inhibitors of histone deacetylases (HDACs) or DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) to open chromatin.3. Target permissive domains: If possible, design gRNAs for essential exons located in more permissive chromatin domains. | [3] [7] [8] |

| High variation in efficiency between gRNAs targeting the same genomic locus. | Local nucleosome occupancy or specific histone modifications are blocking access for some gRNAs but not others. | 1. Use nucleosome positioning data: If available, use MNase-seq data to avoid gRNA targets where the PAM site is directly within a well-positioned nucleosome.2. Test multiple gRNAs: Always design and empirically test 3-4 gRNAs per target to identify one with high activity.3. Employ engineered Cas9 variants: Use high-fidelity or eSpCas9 variants, which have been shown in some studies to have different interactions with chromatin. | [3] [7] [4] |

| Efficient editing in cell line A, but no editing in cell line B for the same gRNA. | Differences in the epigenetic landscape and chromatin accessibility between the two cell lines. | 1. Validate accessibility: Profile or find existing chromatin accessibility data for the specific target site in the recalcitrant cell line (cell line B).2. Employ transcriptional activators: Fuse a transcriptional activation domain (e.g., VP64) to a nuclease-deficient dCas9 and target it near your cutting site to help open the chromatin.3. Use histone acetyltransferase activators: Co-treatment with compounds like YF-2 can increase global chromatin accessibility and boost Cas9 editing efficiency. | [3] [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Chromatin Effects

Protocol 1: Co-Treatment with Chromatin-Modulating Agents

This protocol outlines a pharmacological approach to increase chromatin accessibility and potentially improve CRISPR editing efficiency [8].

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a solution of your chromatin-modulating agent. A common example is the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor Trichostatin A (TSA), typically used at concentrations ranging from 50 nM to 500 nM.

- Cell Transfection: Deliver the CRISPR-Cas9 components (e.g., Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein complex or plasmid) into your target cells using your standard method (e.g., electroporation, lipofection).

- Drug Application: Approximately 4-6 hours post-transfection, add the prepared chromatin-modulating agent to the cell culture medium.

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate the cells for 24-72 hours. Then, harvest the cells and assess editing efficiency using your preferred method (e.g., T7E1 assay, TIDE analysis, or next-generation sequencing).

Protocol 2: Validating Chromatin Accessibility by ATAC-seq

This is a simplified overview of the ATAC-seq workflow to generate genome-wide accessibility profiles for your cell type of interest [1] [6].

- Nuclei Isolation: Harvest and wash your cells. Lyse the cell membrane using a mild detergent to isolate intact nuclei. Critical step: avoid over-lysis which can damage nuclei.

- Tagmentation: Resuspend the nuclei in a buffer containing the Tn5 transposase. The Tn5 enzyme will simultaneously cut accessible DNA and insert sequencing adapters into these regions. The reaction is incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- DNA Purification: Purify the tagmented DNA using a standard DNA clean-up kit (e.g., SPRI beads).

- PCR Amplification & Sequencing: Amplify the purified DNA with primers complementary to the adapters to create the sequencing library. The library is then sequenced on a high-throughput platform.

- Data Analysis: The resulting sequencing reads are aligned to the reference genome. Accessible regions are identified as genomic loci with a high density of aligned reads.

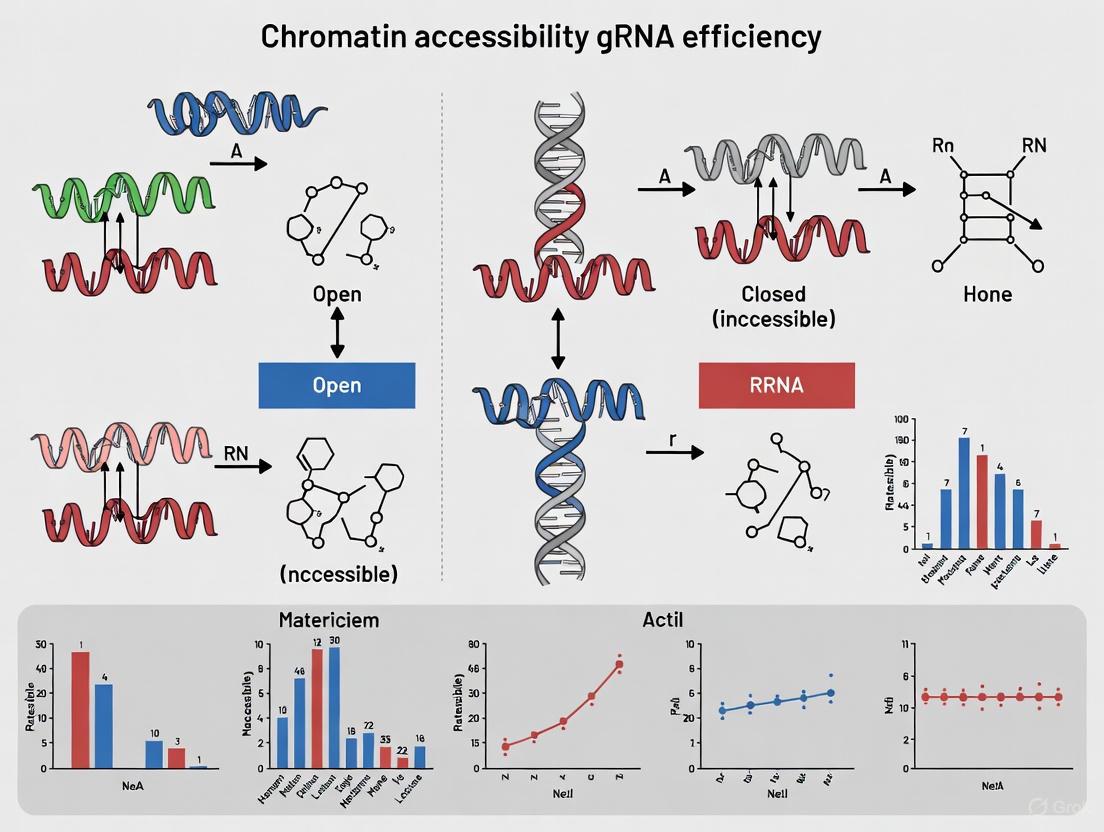

Signaling Pathways and Logical Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between chromatin states and their impact on the CRISPR-Cas9 editing workflow, highlighting potential intervention points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Chromatin and CRISPR Efficiency

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Tn5 Transposase | The core enzyme used in ATAC-seq to tag accessible genomic DNA with sequencing adapters. | Generating genome-wide chromatin accessibility maps from your experimental cell line [1] [6]. |

| HDAC Inhibitors (e.g., Trichostatin A - TSA) | Small molecules that inhibit histone deacetylases, leading to increased histone acetylation and a more open chromatin state. | Co-treatment with CRISPR-Cas9 to improve editing efficiency at refractory heterochromatic targets [8]. |

| dCas9-Activator Fusions (e.g., dCas9-VP64) | A nuclease-deficient Cas9 fused to a transcriptional activation domain. | Targeted chromatin opening at a specific genomic locus by recruiting transcriptional machinery to the site [8] [9]. |

| Engineered Chromatin Remodeling Proteins (E-ChRPs) | Designed proteins that can be programmed to reposition nucleosomes to a specific genomic location. | A research tool for precisely controlling nucleosome positioning to directly study its impact on Cas9 efficiency [9]. |

| Nucleosome Positioning Data (MNase-seq) | Sequencing data that maps the precise locations and occupancy of nucleosomes across the genome. | In silico screening of gRNA targets to avoid designing guides where the PAM site is occluded by a nucleosome [7] [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Does heterochromatin really affect my CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency? Yes, numerous studies have confirmed that heterochromatin (condensed, transcriptionally inactive DNA) can significantly impede CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis. The compact structure physically hinders the access and binding of the Cas9 complex to its target DNA site. Research using imprinted genes as an internal control showed that repressed maternal alleles had up to 7-fold fewer mutations than active paternal alleles when Cas9 exposure was brief or its intracellular concentration was low [10]. Another study reported that TALEN editors could be up to five times more efficient than Cas9 in heterochromatin regions [11].

2. Does chromatin state affect the final outcome or just the speed of editing? Evidence suggests it primarily affects the kinetics, not the final endpoint, of mutagenesis. While heterochromatin slows down the initial rate of cleavage, given sufficient time and high enough levels of Cas9, the mutation frequencies on active and repressed alleles can become similar. The outcome of DNA repair (the spectrum of insertions, deletions, or efficiency of homology-directed repair) appears largely unaffected by the initial chromatin state [10].

3. Are some genome editors better than others for heterochromatic targets? Yes. TALEN has been shown to outperform Cas9 when editing heterochromatin target sites. Single-molecule imaging reveals that Cas9 tends to get encumbered by prolonged local searches on non-specific sites within heterochromatin, reducing its efficiency. TALEN does not face this same limitation to the same degree, making it a more effective choice for these hard-to-reach regions [11].

4. How can I measure the chromatin accessibility of my target site? Several established methods can profile chromatin accessibility genome-wide. The table below summarizes key techniques [1].

Table: Key Methods for Profiling Chromatin Accessibility

| Method | Description | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| ATAC-seq | Uses the Tn5 transposase to cut and tag accessible DNA regions. | Fast, highly sensitive, works with single cells. |

| DNase-seq | Relies on the DNase I enzyme to digest accessible DNA. | Well-established; biases towards hyper-accessible sites like promoters. |

| MNase-seq | Uses Micrococcal Nuclease to digest unprotected DNA. Maps nucleosome positions. | Can map both accessible regions and nucleosome occupancy; has sequence bias. |

| FAIRE-seq | Isoles nucleosome-depleted DNA based on differential solubility after fixation and sonication. | Nuclease-free approach. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Editing Efficiency in Heterochromatic Regions

Problem: Consistently low mutation rates in a target site suspected to be in a heterochromatic region.

Solution: A multi-pronged strategy involving target site re-assessment, experimental optimization, and the use of alternative tools is recommended.

Table: Quantitative Evidence of Heterochromatin Impact on Cas9

| Experimental System | Quantitative Finding | Key Parameter | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (Imprinted Genes) | Up to 7-fold reduction in mutagenesis on repressed alleles. | Low Cas9 concentration, brief exposure. | [10] |

| Live-Cell Imaging in Mammalian Cells | TALEN editing efficiency was up to 5-fold higher than Cas9 in heterochromatin. | Direct comparison in constrained chromatin. | [11] |

| HEK293T, HeLa, and Human Fibroblasts | Editing was consistently more efficient in euchromatin than heterochromatin. | Chromatin accessibility measured by DNase-seq. | [3] |

Actionable Steps:

- Verify Chromatin Status: Use public databases like the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) to find DNase-seq or ATAC-seq data for your cell type. This will confirm if your target site is in an inaccessible region [5].

- Optimize Delivery and Dosage:

- Use modified, synthetic guide RNAs (with 2’-O-methyl modifications) to improve stability and efficiency [12].

- Deliver pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) via electroporation. This ensures high intracellular concentration and can reduce off-target effects [12].

- Consider using a strong, cell-type-appropriate promoter (e.g., EF1α, CAG, or a synthetic promoter) to drive high Cas9 expression, helping to overcome the chromatin barrier [10].

- Consider Alternative Editors: If Cas9 continues to fail, switch to TALEN for that specific target, as it is less hindered by heterochromatin [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Reagents for Studying Chromatin Effects on Genome Editing

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Cas9-gRNA RNP Complex | Direct delivery of editing machinery; improves kinetics and reduces toxicity. |

| Modified sgRNAs | Chemically synthesized guides with stability modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl) to enhance editing efficiency. |

| Chromatin Modifying Enzymes | Enzymes like DNase I (for DNase-seq) or Tn5 transposase (for ATAC-seq) to probe DNA accessibility. |

| dCas9 Fusion Proteins | Catalytically "dead" Cas9 fused to effector domains to manipulate or mark chromatin without cutting DNA. |

| TALEN Plasmids | An alternative nuclease system that can be used when Cas9 efficiency is low due to chromatin. |

Experimental Deep Dive: Key Supporting Protocols

1. Protocol: Quantifying Allelic Editing Bias in Imprinted Genes

This method, derived from a key study, uses the natural epigenetic differences in imprinted genes to isolate the effect of chromatin [10].

- Principle: In a diploid cell, the maternal and paternal alleles of an imprinted gene have identical DNA sequences but distinct chromatin states (e.g., one euchromatic and active, the other heterochromatic and silenced). Any difference in editing efficiency between the alleles can be unequivocally attributed to epigenetics.

- Workflow:

- Cell Line Selection: Use F1 hybrid mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) from reciprocal crosses (e.g., C57BL/6J and JF1 strains) to have genetic markers (SNPs) that distinguish maternal and paternal alleles.

- Transfection: Co-transfect cells with a Cas9/sgRNA expression plasmid (e.g., pX459) and a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) donor template.

- Selection and Harvest: Select transfected cells (e.g., with puromycin) and harvest as a pool ~96 hours post-transfection.

- Amplification and Sequencing: PCR-amplify the target region from genomic DNA and perform deep sequencing (e.g., Illumina).

- Allele-Specific Analysis: Use the known SNPs to bioinformatically separate sequencing reads into maternal and paternal alleles. Calculate the frequency and spectrum of mutations on each allele independently.

The diagram below illustrates this experimental logic and workflow.

2. Protocol: Live-Cell Single-Molecule Imaging of Editor Search Dynamics

This technique visualizes how genome-editing proteins like Cas9 and TALEN move and search for their targets in different chromatin environments [11].

- Principle: Fuse a halo-tag to a nuclease-deficient editor (dCas9 or TALE). Label it with a bright, cell-permeable fluorescent dye (e.g., JF549) for single-molecule tracking in live mammalian cells.

- Workflow:

- Design and Labeling: Design TALE or dCas9 proteins targeting euchromatic (e.g., CFTR gene) or heterochromatic (e.g., repetitive Alu elements) regions. Express the halo-tagged proteins in cells and label them with the fluorescent dye.

- Microscopy under Two Conditions:

- Short Exposure (10-20 ms): Captures fast diffusion kinetics, distinguishing between global search (fast diffusion/hopping) and local search (slow diffusion/sliding).

- Long Exposure (500 ms): Blurs out fast-moving molecules, allowing visualization and tracking of only the DNA-bound proteins to measure their residence times.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate diffusion coefficients from short-exposure trajectories.

- Fit residence time histograms from long-exposure movies to a two-component exponential decay model to determine the lifetimes of non-specifically and specifically bound molecules.

The following diagram visualizes the search behaviors and analysis methods.

The Role of Active Transcription in Stimulating Cas9 Activity and Release

Within the nucleus, the efficiency of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing is not solely determined by the guide RNA (gRNA) sequence. The local chromatin environment presents a significant physical and regulatory barrier. Chromatin, the complex of DNA and proteins, exists in various states of compaction. Heterochromatin, a tightly packed form, can impede Cas9 access to its target DNA sequence, while active transcription is associated with a more open chromatin configuration and has been shown to directly stimulate DNA cleavage by Cas9 [13]. This guide addresses common challenges and questions researchers face when considering the impact of transcription and chromatin state on their CRISPR experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

FAQ: Why does the same gRNA have different editing efficiencies in different cell types?

- Cause: The primary cause is often differences in the chromatin accessibility and transcriptional status of the target locus between cell types. A locus that is actively transcribed in one cell line may be silent and packaged into heterochromatin in another [14] [13].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Consult Epigenomic Maps: Before designing experiments, check publicly available chromatin accessibility data (e.g., from ATAC-seq or DNase-seq) for your specific cell type. Targeting regions confirmed to be in open chromatin will yield more predictable results [14].

- Measure Local Chromatin: If no data exists, consider performing a pilot assay to measure accessibility at your target site.

- Design Multiple gRNAs: If possible, design several gRNAs targeting the same gene but in different genomic regions (e.g, promoter, intron, exon) to increase the likelihood of one residing in an accessible locus.

FAQ: My in vitro cleavage assay works perfectly, but editing fails in my cellular model. Why?

- Cause: In vitro assays use purified, protein-free DNA, while cellular DNA is packaged into chromatin. Nucleosomes, the basic units of chromatin, can completely block Cas9 access to DNA, as demonstrated in cell-free assays [13].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Chromatin State: Confirm that your target site is not located in a nucleosome-dense region. Nucleosome positioning data can help with this.

- Time Your Experiment: For ex vivo editing of primary cells (like T cells), the chromatin landscape can change with activation status. Electroporation of Cas9-RNP complexes is often most effective shortly after cell stimulation when the genome is more receptive [14].

- Consider Epigenetic Pretreatment: In some cases, pretreatment with cytokines like IL-7 has been shown to enhance gene-editing efficiency in unstimulated T cells, potentially by altering chromatin accessibility [14].

FAQ: How does active transcription directly influence the Cas9 enzyme mechanism?

- Cause: Recent evidence suggests that active transcription does more than just open chromatin. The act of transcription itself can directly stimulate DNA cleavage by influencing Cas9 release rates [13].

- Explanation & Solution: The passage of RNA polymerase along the DNA template can act as a "molecular motor" that actively displaces Cas9 from the DNA after cleavage, facilitating enzyme turnover. This effect is strand-specific. To leverage this, if the target strand is known, design gRNAs so that the non-target strand is the same as the transcribed strand, potentially allowing the transcription machinery to aid in Cas9 dissociation [13].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Transcription Impact

Protocol 1: Correlating Endogenous Editing with Transcription Status

This protocol outlines how to determine if the transcriptional activity of a locus affects Cas9 editing efficiency in your cell model.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Isogenic Cell Lines | Clonal cell lines derived from a single progenitor, ensuring genetic identity and minimizing variability. |

| dCas9-Expresssing Line | A cell line stably expressing catalytically "dead" Cas9, used to measure binding accessibility without cleavage. |

| ATAC-seq Kit | A kit to perform Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing, which maps open chromatin regions genome-wide. |

| gRNA Design Tool (e.g., CRISPRon) | An AI-based tool to predict gRNA on-target activity based on sequence, helping to control for sequence-intrinsic effects [15] [16]. |

| RT-qPCR Reagents | Reagents for Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR to measure mRNA levels and quantify transcriptional activity at the target locus. |

Methodology:

- Cell Line Selection: Obtain two isogenic cell lines where your gene of interest is either actively transcribed or silenced.

- gRNA Design & Transfection: Design a panel of 3-5 high-scoring gRNAs (using a tool like CRISPRon [16]) targeting the same locus. Transfert each gRNA with Cas9 into both cell lines.

- Efficiency Quantification: 72 hours post-transfection, harvest genomic DNA and use targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) to quantify the indel percentage at the target site for each gRNA-cell line combination.

- Chromatin & Transcription Assessment:

- Perform ATAC-seq on both cell lines to map genome-wide chromatin accessibility.

- Use RT-qPCR to measure the baseline mRNA expression level of your target gene in both cell lines.

- (Optional) Use dCas9 ChIP-qPCR in a stable cell line to directly measure Cas9 binding efficiency at the target site in both transcriptional states.

- Data Analysis: Correlate the measured indel percentages with the transcriptional activity (mRNA level) and chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq signal) at the target site.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening of gRNA Efficiency

This method uses a pooled gRNA library to systematically evaluate how chromatin features and sequence context govern editing outcomes.

Methodology:

- Library Design: Clone a pooled library of thousands of gRNAs into a lentiviral vector. The library should include gRNAs targeting genomic sites with diverse epigenetic contexts [16].

- Viral Transduction: Transduce your target cells (e.g., HEK293T) with the lentiviral gRNA library at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive only one gRNA.

- Editing & Enrichment: Allow sufficient time (e.g., 8-10 days) for Cas9 editing and enrichment of edited cells, often facilitated by a selectable marker on the vector [16].

- Sequencing & Analysis: Harvest genomic DNA and perform deep sequencing of the target sites. The resulting indel frequency for each gRNA is its measured on-target activity.

- Integration with Epigenetic Data: Integrate the gRNA efficiency data with cell-type-specific epigenetic data (e.g., ATAC-seq, histone modification ChIP-seq). This allows you to build a model that predicts efficiency based on both sequence and chromatin features [14].

The workflow for this high-throughput approach is summarized in the following diagram:

Data Presentation: Quantitative Impact of Chromatin

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from research on how chromatin state and transcription influence Cas9 activity.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Chromatin State on CRISPR-Cas9 Efficiency

| Experimental Observation | Quantitative Impact / Correlation | Experimental Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatin Accessibility | Positive correlation (R values vary by cell type) | ATAC-seq signal vs. measured indel percentage in human T cells. | [14] |

| Active Transcription | Directly stimulates cleavage; strand-specific effect on Cas9 release. | Observation from controlled allele-specific studies. | [13] |

| Nucleosome Occupancy | Can completely block Cas9 access in vitro; major hurdle in vivo. | Cell-free cleavage assays with reconstituted nucleosomes. | [13] |

| DNA Methylation (CpG) | Does not directly hinder Cas9 binding or cleavage. | In vitro cleavage assays comparing methylated vs. unmethylated DNA substrates. | [13] |

| gRNA Efficiency Prediction | Model performance (Spearman's R) improved by adding epigenetic features. | Combining sequence-based prediction with ATAC-seq data in T cells. | [14] |

Visualization of the Core Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the proposed mechanistic relationship between active transcription and enhanced Cas9 activity and release, which is central to troubleshooting the issues described in the FAQs.

This technical support center provides guidance for researchers investigating how temporal chromatin states impact genome editing efficiency. Chromatin modifications are dynamic regulators of DNA accessibility, directly influencing the efficacy of CRISPR-based systems [17]. A thorough understanding of these states is crucial for predicting and optimizing guide RNA (gRNA) performance in diverse cellular contexts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are chromatin states and why are they important for genome editing? Chromatin states are combinatorial patterns of histone modifications (e.g., methylation, acetylation) that functionally annotate the genome into regions such as active promoters, enhancers, and repressed heterochromatin [18]. These states determine the physical openness or compactness of chromatin, thereby controlling the accessibility of the DNA strand to editors like Cas9. Inaccessible, closed chromatin is a major cause of low editing efficiency [17].

How can I identify the chromatin state of my target locus? You must use computational tools to analyze existing epigenomic data (e.g., ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq) for your cell type.

- ChromHMM is the most widely used tool for this purpose. It uses a multivariate hidden Markov model to segment the genome into discrete states based on histone mark data [19] [18].

- Alternative Tools: Other tools like Segway or EpiCSeg may offer advantages for specific data types, such as direct read count modeling [19]. Procedure:

- Obtain epigenomic datasets (e.g., from ENCODE or Roadmap Epigenomics) for your specific cell type.

- Run ChromHMM to learn the chromatin state model for your cell type.

- Annotate your target genomic region with the learned states to determine if it resides in an open (active) or closed (repressed) chromatin context.

My gRNA has high predicted on-target efficiency but performs poorly in my experiment. Could chromatin be the cause? Yes, this is a common issue. Computational on-target scores often do not fully account for the local chromatin environment.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Annotate Chromatin State: As described above, check the chromatin state of your target site.

- Correlate with Accessibility: Use ATAC-seq or DNase-seq data to confirm the physical accessibility of the region. A low signal suggests closed chromatin.

- Design Alternative gRNAs: If the target is in closed chromatin, design new gRNAs that target nearby regions in open chromatin, even if their raw efficiency score is slightly lower.

- Use Chromatin Modulators: Consider co-delivering chromatin-modulating agents, such as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, to transiently open the chromatin structure at your target site.

Are there computational tools that incorporate chromatin data into gRNA design? While most standard gRNA design tools focus on sequence-based rules for on-target and off-target activity, the chromatin context must be assessed separately. The recommended workflow is to first use chromatin state maps to select a target region that is accessible, and then use tools like CRISPick or CRISPOR to design the specific gRNA sequence within that region [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Editing Efficiency in a Closed Chromatin Region

Issue: Your target site is confirmed to be in a repressed chromatin state (e.g., marked by H3K9me2/3 or H3K27me3), leading to poor Cas9 binding and cutting.

Solution 1: Epigenome Editing Pre-conditioning A powerful strategy is to use epigenome editing to open the chromatin before introducing the editing machinery.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Select an Activator: Use a programmable editor (e.g., dCas9 fused to the p300 core domain for H3K27ac deposition) to install an activating histone mark at the target site [17].

- Pre-treat Cells: Transfert cells with the dCas9-activator and a specific gRNA targeting your locus.

- Wait for Chromatin Remodeling: Incubate for 24-48 hours to allow for stable establishment of the active chromatin mark.

- Perform Main Edit: Introduce the active Cas9 nuclease and your therapeutic gRNA. The pre-conditioned, more open chromatin should yield higher editing efficiency.

Solution 2: Co-delivery with Chromatin-opening Agents For a simpler approach, co-deliver chemical inhibitors of chromatin-repressing enzymes.

- Reagents: HDAC inhibitors (e.g., Sodium Butyrate, Trichostatin A) or DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (e.g., 5-Azacytidine).

- Procedure: Treat cells with a low, non-toxic concentration of the inhibitor 24 hours before and during the CRISPR editing transfection. Titrate the concentration carefully, as high doses can cause widespread epigenetic dysregulation and cell toxicity.

Problem: High Cell Toxicity During Epigenome Editing

Issue: Over-expression of powerful chromatin modifiers, especially transcriptional activators like p300, can lead to significant cell death and indirect transcriptional changes [17].

Mitigation Strategies:

- Use Inducible Systems: Use a doxycycline (DOX)-inducible system to control the timing and duration of epigenome editor expression, limiting prolonged exposure [17].

- Titrate Expression: Use a lower concentration of the inducer (e.g., 20-fold lower DOX for p300) to reduce expression levels to a functional but less toxic range [17].

- Catalytic Domains: Use only the catalytic domain (CD) of the chromatin modifier, fused to dCas9, rather than the full-length protein. This minimizes non-catalytic, confounding effects that can contribute to toxicity [17].

Chromatin State Analysis Tools and Data

The table below summarizes key computational tools for chromatin state discovery and annotation, which are essential for planning your experiments [19].

| Tool | Modeling Strategy | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChromHMM | Multivariate HMM + EM | Fast, interpretable, widely adopted | Standard, cell type-specific chromatin segmentation [19] [18]. |

| TreeHMM | Tree-structured HMM | Models lineage relationships among cell types | Analyzing related cell types with a known developmental hierarchy [19]. |

| GATE | Graph-aware HMM | Integrates spatial proximity data (e.g., Hi-C) | Accounting for 3D chromatin structure in state annotation [19]. |

| EpiCSeg | HMM + Count data | Uses actual ChIP-seq read counts instead of binarization | More accurate modeling of weak/moderate histone signals [19]. |

| Chromswitch | Peak-based clustering | Uses ChIP-seq peaks and statistical summaries | Comparing chromatin states in a specific genomic region across conditions [18]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents used in advanced epigenome editing studies, which can be integrated into your troubleshooting workflows [17].

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| dCas9GCN4 System | Programmable scaffold that amplifies effector recruitment via GCN4 motif array [17]. |

| CDscFV Effectors | Catalytic domains of chromatin writers (e.g., for H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K9me2) fused to scFV. Isolates the function of the mark itself [17]. |

| mut-CDscFV | Catalytic point mutants of effectors. Critical controls to confirm phenotypic effects are due to chromatin mark deposition and not just protein tethering [17]. |

| Doxycycline (DOX)-Inducible System | Allows dynamic control of epigenome editor expression, mitigating toxicity and enabling memory studies [17]. |

| CUT&RUN-qPCR | A low-background method to quantitatively validate the deposition of chromatin marks at the target locus after editing [17]. |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Workflow for Editing in Dynamic Chromatin

Modular Epigenome Editing Platform

FAQs: Core Concepts and Experimental Design

Q1: What is the fundamental relationship between ATAC-seq signals and CRISPR gRNA efficiency? Research consistently shows a positive correlation between chromatin accessibility and gRNA efficiency. Genomic regions with higher ATAC-seq signals, indicating more open chromatin, generally enable more efficient CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. This relationship has been validated across multiple systems, including human T cells and zebrafish embryos [14] [7] [3].

Q2: Why does chromatin accessibility impact CRISPR editing efficiency? Chromatin accessibility reflects how "open" or "closed" a genomic region is. In closed chromatin (heterochromatin), DNA is tightly wrapped around nucleosomes and less accessible to CRISPR machinery, reducing editing efficiency. In open chromatin (euchromatin), the Cas9-gRNA complex can more easily bind target DNA sequences, resulting in higher efficiency [3] [5].

Q3: Can I design efficient gRNAs for targets in epigenetically closed regions? Yes. While closed regions typically show reduced efficiency, studies demonstrate that designing two gRNAs targeting adjacent regions in closed chromatin can improve gene-editing outcomes. Pretreating cells with cytokines like IL-7 can also enhance efficiency in these challenging contexts [14].

Q4: My ATAC-seq data shows low TSS enrichment. How does this affect gRNA design? Low TSS (Transcription Start Site) enrichment suggests poor signal-to-noise ratio or suboptimal library preparation. This can compromise the reliability of chromatin accessibility data for gRNA prediction. A TSS enrichment score below 6 is a warning sign; you should optimize your ATAC-seq protocol before using the data to inform gRNA design [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting ATAC-seq Data Quality for gRNA Prediction

Poor ATAC-seq data quality is a primary source of failed gRNA efficiency predictions.

Problem: Strange ATAC-seq fragment size distribution.

- Expected: Clear peaks at ~50 bp (nucleosome-free), ~200 bp, and ~400 bp [21].

- Symptom: Missing or unclear nucleosomal patterning.

- Solution:

- Check for over-tagmentation, which can digest chromatin excessively and mask nucleosomal features [21].

- Verify cell viability and ensure no DNA degradation occurred during sample preparation.

- Optimize transposition reaction time and input cell number.

Problem: Low correlation between predicted and actual gRNA efficiency.

- Symptom: gRNAs selected using ATAC-seq data perform poorly in editing assays.

- Solution:

- Combine epigenetic data with sequence-based prediction tools. Using ATAC-seq data alone is insufficient; integration with algorithms significantly improves performance [14].

- Ensure ATAC-seq data is from a relevant cell type, as chromatin states are cell-specific [14].

- For critical experiments, validate chromatin accessibility at the target locus by examining ATAC-seq signal tracks in a genome browser.

Problem: Peaks called in ATAC-seq data do not agree with biological expectation.

Troubleshooting Low gRNA Efficiency Despite High Chromatin Accessibility

- Problem: gRNA targets an open chromatin region but editing efficiency remains low.

- Solution:

- Investigate gRNA secondary structure. The guide sequence itself can form secondary structures that inhibit its function, independent of chromatin context [3].

- Verify sequence-based features. Ensure the gRNA follows established sequence rules (e.g., preference for guanine at positions -1 and -2 upstream of the PAM) [7].

- Check for genetic variation. Ensure no SNPs or indels in the target sequence are preventing gRNA binding.

- Solution:

Table 1: Summary of Key Studies on ATAC-seq and gRNA Efficiency Correlation

| Study System | Key Finding | Quantitative Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human T Cells | Combining ATAC-seq with prediction tools improves gRNA design. | Significantly improved gene-editing efficiency over sequence-based tools alone. | [14] |

| Zebrafish Embryos | Chromatin accessibility positively correlates with CRISPR/Cas9 efficiency. | Open chromatin regions showed higher mutation rates in F0 embryos. | [7] |

| HEK293T, HeLa, Human Fibroblasts | Gene editing is more efficient in euchromatin vs. heterochromatin. | Confirmed in multiple human cell types. | [3] |

| Computational Analysis (GUIDE-seq) | Correlation between sequence and cleavage frequency is altered by DNA accessibility. | Abolished in less accessible regions. | [5] |

Table 2: Performance of Different gRNA Prediction Models Incorporating Chromatin Data

| Prediction Model | Features Used | Correlation Coefficient | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CINDEL | Hand-crafted features | 0.61 | [23] |

| DeepCpf1 | One-hot encoding + Chromatin Accessibility | 0.71 | [23] |

| Cas-FM (RNA-FM) | Pretrained RNA foundation model embedding | 0.76 | [23] |

| Cas-FM-CA (RNA-FM) | Foundation model + Chromatin Accessibility | 0.78 | [23] |

Experimental Protocols

Key Materials:

- Primary human T cells (e.g., from PBMCs)

- Tn5 transposase (commercially available)

- RPMI-1640 culture medium with IL-2 (100 IU/ml)

- NEPA 21 electroporator

- Equipment for standard molecular biology and sequencing

Methodology:

- T Cell Culture and Stimulation: Stimulate human PBMCs with mitomycin C-treated K562 cells expressing anti-CD3 scFv and CD80.

- Nuclei Preparation and Transposition: Lyse cells to isolate nuclei. Incubate nuclei with the Tn5 transposase to simultaneously fragment and tag accessible DNA with adapters.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Purify transposed DNA and amplify via PCR to create sequencing libraries. Perform paired-end sequencing on an Illumina platform.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment: Trim adapters and align reads to the reference genome (e.g., hg38) using Bowtie2 [14].

- Peak Calling: Identify regions of significant chromatin accessibility using MACS2 [14].

- Data Integration: Overlay potential gRNA target sequences with ATAC-seq peaks. Prioritize gRNAs that bind within accessible regions.

Key Materials:

- Designed gRNAs targeting adjacent sites

- Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 system (IDT)

- Recombinant IL-7 (10 ng/ml)

Methodology:

- Dual gRNA Design: For a target in a closed chromatin region, design two gRNAs that bind to closely spaced adjacent sites.

- Cell Pretreatment: For unstimulated T cells, pretreat with IL-7 (10 ng/ml) to enhance basal editing efficiency.

- RNP Complex Electroporation: Form ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes by combining Cas9 nuclease with the two annealed gRNAs. Introduce the RNP complexes into T cells via electroporation.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

Workflow for ATAC-seq Guided gRNA Design

ATAC-seq Data Troubleshooting for gRNA Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperactive Tn5 Transposase | Enzymatic tagmentation of open chromatin for ATAC-seq library prep. | Commercially available (e.g., Illumina Nextera). |

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 System | Pre-complexed Cas9-gRNA RNP for highly efficient editing in primary cells. | Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) [14]. |

| Recombinant IL-7 | Cytokine pretreatment to enhance gene-editing efficiency in unstimulated/naïve T cells [14]. | PeproTech [14]. |

| NEPA 21 Electroporator | Efficient delivery of RNP complexes into hard-to-transfect cells like primary T cells [14]. | Nepa Gene [14]. |

| ENCODE Blacklist Regions | Genomic regions with anomalous signals; should be filtered out during ATAC-seq analysis [24]. | ENCODE Consortium [24]. |

| MACS2 | Standard peak calling software for identifying accessible chromatin regions from ATAC-seq data [14] [24]. | Open-source tool. |

| Bowtie2 / BWA-MEM | Sequence aligners for mapping ATAC-seq reads to a reference genome [24]. | Open-source tools. |

Mapping the Epigenome: Advanced Tools to Link Perturbations and Chromatin State

Core Concepts and FAQs

What are single-cell CRISPR screens with epigenetic readouts?

These are advanced functional genomics methods that combine multiplexed CRISPR perturbations with single-cell epigenomic profiling. Unlike traditional screens that measure survival or surface markers, these techniques directly link genetic perturbations to changes in the chromatin landscape within individual cells, revealing how specific genes regulate epigenetic states [25] [26].

How do chromatin accessibility and structure impact CRISPR editing efficiency?

Chromatin accessibility significantly influences Cas9 cutting efficiency. Multiple studies demonstrate that closed, silenced chromatin states inhibit Cas9 binding and editing, while open chromatin regions permit more efficient editing [3] [27] [5].

Table: Experimental Evidence of Chromatin Impact on CRISPR Efficiency

| Chromatin State | Effect on Editing Efficiency | Experimental System | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterochromatin (Closed) | Reduced by ~30-40% at most target sites [27] | HEK293T inducible silencing system | Editing efficiency negatively correlated with repressive histone mark H3K27me3 [27] |

| Euchromatin (Open) | Higher efficiency [3] | HEK293T, HeLa, and human fibroblasts | Editing more efficient in euchromatin versus heterochromatin [3] |

| Variable Accessibility | Abolished correlation between sequence match and cleavage in less accessible regions [5] | GUIDE-seq and CIRCLE-seq computational analysis | DNA accessibility modulates the relationship between guide-target complementarity and cleavage frequency [5] |

Why do different sgRNAs targeting the same gene show variable performance?

Variability arises from both sgRNA-intrinsic properties and local chromatin context:

- sgRNA sequence determinants: The secondary structure formation of the guide RNA itself affects Cas9 activity [3].

- Chromatin environment: Even different target sites within the same gene locus can experience varying levels of chromatin compaction, leading to divergent editing outcomes [27].

- Best practice: Design 3-4 sgRNAs per gene to mitigate the impact of individual sgRNA performance variability [28].

What are the solutions for low signal-to-noise in epigenetic CRISPR screens?

- Increase selection pressure: For negative screens where the goal is to identify essential genes, applying stronger selective pressure can enhance the depletion signal of effective sgRNAs [28].

- Ensure sufficient cell coverage: Plan for approximately 100 cells per perturbed gene to achieve adequate statistical power for detecting chromatin accessibility changes [29].

- Verify chromatin perturbation: Include positive control sgRNAs targeting known epigenetic regulators and confirm expected chromatin changes at their target loci [25] [26].

How can I determine if my single-cell epigenetic CRISPR screen was successful?

- Positive control validation: Include well-validated positive-control sgRNAs (e.g., targeting known chromatin regulators). Successful perturbation should recapitulate expected chromatin accessibility changes [28] [26].

- Data quality metrics: Assess single-cell library complexity, percentage of reads in peaks, and fragment size distribution, which should resemble high-quality bulk ATAC-seq data [25].

- Phenotypic concordance: Verify that perturbations of known factors produce the expected chromatin phenotypes (e.g., SPI1/PU.1 perturbation reduces accessibility at its motif sites) [25].

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Perturb-ATAC Workflow

The Perturb-ATAC method enables simultaneous detection of CRISPR guide RNAs and genome-wide chromatin accessibility profiling in single cells [25] [26].

Protocol Steps:

- Single-cell capture: Cells are captured in microfluidic chambers (e.g., Fluidigm IFC) and lysed [25].

- Tagmentation: Genomic DNA is fragmented and tagged with sequencing adapters using the Tn5 transposase, which preferentially targets open chromatin regions [25].

- sgRNA detection: CRISPR sgRNAs or their identifying barcodes (GBCs) are reverse transcribed using target-specific primers within each reaction chamber [25].

- Whole-cell amplification: All contents from each chamber are amplified by PCR [25].

- Library separation: sgRNA and ATAC amplicons are separately amplified with cell-specific barcoded primers, then pooled for sequencing [25].

- Multi-modal analysis: Sequencing data is processed to assign chromatin accessibility profiles to specific genetic perturbations in individual cells [25].

CROP-seq for Single-Cell Transcriptional and Perturbation Profiling

While primarily for transcriptome analysis, CROP-seq principles are adaptable to epigenetic readouts and address key design considerations [30].

Table: Comparison of Single-Cell CRISPR Screening Approaches

| Feature | Perturb-ATAC [25] [26] | CROP-seq [30] | 10x Genomics 5' Screening [29] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Readout | Chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) | Gene expression (RNA-seq) | Gene expression + surface proteins |

| sgRNA Detection | Guide barcode reverse transcription | Polyadenylated sgRNA transcript | Direct capture of guide sequence |

| Key Advantage | Direct measurement of TF binding, nucleosome positioning | No viral recombination concerns | Compatible with existing libraries; multiomic capacity |

| Compatibility | Custom CRISPRi/CRISPRko libraries | Requires modified vector (CROPseq-Guide-Puro) | Works with most existing Cas9 libraries |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Single-Cell Epigenetic CRISPR Screens

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Modified sgRNA Vectors | Expresses guide RNA in detectable format for single-cell assays | CROPseq-Guide-Puro [30], Perturb-ATAC GBC vectors [25] |

| Tn5 Transposase | Fragments and tags accessible genomic DNA for ATAC-seq | Hyperactive Tn5 [25] |

| Chromatin State Model Systems | Controls for chromatin effects on editing | Doxycycline-inducible Gal4EED system [27] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Analyzes single-cell multi-modal perturbation data | MAGeCK [28], SCENIC [31] |

| Validated Epigenetic Regulators | Positive controls for screening | SRCAP, KAT5 (identified in fibrosis screen) [31] |

Advanced Troubleshooting: Addressing Complex Scenarios

Interpreting epistatic relationships between chromatin regulators

Combinatorial Perturb-ATAC can reveal how multiple epigenetic regulators interact hierarchically:

- Experimental design: Perform pairwise co-deletion of transcription factors or chromatin modifiers and measure the resulting chromatin accessibility landscape [25] [26].

- Analysis approach: Identify synergistic (greater than additive) or antagonistic effects on chromatin accessibility at shared regulatory elements [26].

- Biological insight: Genomic co-localization of transcription factors often predicts synergistic interactions in chromatin regulation [26].

Optimizing for specific chromatin phenotypes

When screening for regulators of specific epigenetic states:

- FACS enrichment: Sort cells based on chromatin accessibility reporters or specific histone modifications before single-cell library preparation [28].

- Trajectory analysis: In developmental systems, order cells along differentiation trajectories and identify perturbations that disrupt normal chromatin state progression [26].

- Motif analysis: Compute differential transcription factor motif accessibility across perturbations to infer regulatory hierarchies [25].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

This section provides solutions to common issues encountered during CRISPR-sciATAC experiments, helping researchers achieve high-quality data on how genetic perturbations alter the epigenetic landscape.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common CRISPR-sciATAC Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low single-cell recovery or capture rate | Nuclear envelope integrity compromised during processing [32] | Optimize fixation and lysis conditions to preserve nuclear envelope [33] [32] |

| Low gRNA detection/assignment rate | Inefficient capture of gRNA sequences; low gRNA transcript abundance [34] | Use a custom, easy-to-purify transposase [33] [32]; Flank lentiviral sgRNA with pre-integrated Nextera adapters [34] |

| High species collision rate (in control experiments) | Inefficient single-cell barcoding or nuclear partitioning [33] | Use a unique, easy-to-purify transposase and optimize combinatorial indexing steps [33] |

| Variable chromatin accessibility profiles for the same gRNA | Biological variability or insufficient cell count [33] | Ensure adequate cell numbers per perturbation; Downsampling analysis shows some perturbations (e.g., EZH2) need only ~5 cells, while others (e.g., TET2) may need ~225 [33] |

| No cleavage band or low editing efficiency | Chromatin inaccessibility at target site; gRNA secondary structure [3] [5] | Design gRNAs targeting accessible regions (euchromatin) [3]; Check for and avoid gRNA sequences prone to secondary structure formation [3] |

| Unexpected cell proliferation phenotypes | Targeting essential genes or genes affecting growth [33] | Perform early-timepoint bulk gRNA amplification to distinguish essential gene drop-out from technical capture failure [33] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core innovation of CRISPR-sciATAC compared to previous methods?

CRISPR-sciATAC is a novel integrative platform that combines pooled CRISPR screening with single-cell combinatorial indexing ATAC-seq (sciATAC-seq). Its key innovation is the ability to simultaneously capture CRISPR guide RNAs (gRNAs) and genome-wide chromatin accessibility profiles from tens of thousands of single cells in a single, scalable experiment. This creates a direct causal link between a genetic perturbation and its consequent changes in genome-wide chromatin organization within a uniform genetic background [33] [32] [35].

Q2: How does chromatin accessibility directly impact CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing efficiency?

Research confirms that CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing is significantly more efficient in euchromatin (open, accessible DNA) than in heterochromatin (closed, inaccessible DNA). The level of DNA accessibility at the target locus is a major cellular factor that influences cleavage efficiency. Furthermore, the secondary structure of the gRNA sequence itself is an independent determinant of Cas9 activity [3] [5].

Q3: My single-cell data shows high variability after a perturbation. Is this technical noise or biological reality?

It can be both. Technical noise should be minimized by optimizing protocols. However, CRISPR-sciATAC has revealed that the loss of certain chromatin modifiers can intrinsically increase cell-to-cell variability in chromatin accessibility. For example, disrupting the TET2 gene creates more variable chromatin states than non-targeting controls, requiring more single cells (~225) to accurately represent the population average. In contrast, perturbations like EZH2 loss show consistent changes with as few as 5 cells [33].

Q4: Can I use CRISPR-sciATAC to study nucleosome positioning, not just accessibility?

Yes. Beyond measuring accessibility, CRISPR-sciATAC is equipped with computational methods to map dynamic movements of nucleosomes. For instance, knocking out ARID1A led to tighter nucleosome spacing and reduced accessibility at specific transcription factor binding sites, demonstrating the method's power to reveal nucleosome-level reorganization [33] [32].

Q5: What is the throughput and cost advantage of CRISPR-sciATAC over similar methods like Perturb-ATAC?

CRISPR-sciATAC is designed for high throughput and lower cost. It does not require microfluidic devices for single-cell isolation. In contrast, methods like Perturb-ATAC need multiple runs on a Fluidigm C1 to process about 96 cells per run. CRISPR-sciATAC can process up to ~30,000 cells in a single study. One analysis showed that Perturb-ATAC cost about $9.80 per cell, whereas the Spear-ATAC method (a similar droplet-based approach) reduced the cost to about $0.46 per cell [33] [34].

Essential Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Core CRISPR-sciATAC Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in the CRISPR-sciATAC protocol, from cell preparation to sequencing.

Detailed Protocol: From Library Design to Data Generation

gRNA Library Design & Cloning:

- Design multiple gRNAs (typically 3-5) per target gene to ensure robust results [36].

- Clone gRNA sequences into a lentiviral vector (e.g., CROP-seq vector) where the gRNA is embedded within a longer RNA Polymerase II transcript for co-expression with the perturbation [33].

- Include a sufficient number of non-targeting control gRNAs (e.g., 3-5) for baseline comparison [33].

Cell Preparation & Transduction:

- Use a cell line expressing Cas9 (e.g., K562-Cas9 for knockout screens or K562-dCas9-KRAB for CRISPRi screens) [33] [34].

- Transduce cells with the lentiviral gRNA library at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI < 0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single gRNA [36].

- Apply antibiotic selection (e.g., puromycin) for several days to enrich for successfully transduced cells [33] [37].

Nuclei Preparation & Combinatorial Indexing:

- After about 7-10 days of selection, harvest and fix cells. Gently lyse cells to isolate intact nuclei, being careful to preserve the nuclear envelope [33] [32].

- Distribute nuclei across a 96-well plate. In each well, perform tagmentation using a hyperactive Tn5 transposase (e.g., the unique, easy-to-purify transposase from Vibrio parahemolyticus mentioned in the study). This step simultaneously fragments accessible DNA and adds well-specific barcode #1 [33].

- Perform in situ reverse transcription to capture the gRNA sequences and tag them with the same well-specific barcode #1 [33].

Library Construction & Sequencing:

- Pool all nuclei and then redistribute them into a new 96-well plate.

- In each new well, perform a PCR reaction to add a second barcode (barcode #2) to both the ATAC fragments and the gRNA sequences. The combination of barcode #1 and barcode #2 creates a unique "cell barcode" for each single cell [33].

- Perform a final PCR to add sequencing adapters.

- Sequence the final library using paired-end sequencing on an Illumina platform to capture both the chromatin accessibility fragments and the gRNA sequences [33].

The Impact of Chromatin on Editing: A Conceptual Diagram

The diagram below visualizes the relationship between chromatin state and CRISPR-Cas9 efficiency, a key concept underlying the need for assays like CRISPR-sciATAC.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for CRISPR-sciATAC

| Item | Function / Role in the Experiment | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperactive Tn5 Transposase | Fragments accessible chromatin and simultaneously adds sequencing adapters. The heart of ATAC-seq. | A unique, easy-to-purify transposase from Vibrio parahemolyticus was developed for CRISPR-sciATAC [33] [32]. |

| Lentiviral gRNA Library | Delivers genetic perturbations (knockout, CRISPRi/a) into a pool of cells. | Use a vector like the CROP-seq vector, which allows gRNA capture as part of a Pol II transcript [33]. Include controls. |

| Cas9-Expressing Cell Line | Provides the nuclease (or inactive variant) for targeted genomic perturbation. | K562 leukemia cells were used in the foundational study [33]. Can be adapted to other cell lines relevant to your research. |

| Combinatorial Indexing Primers | Unique barcodes added in two rounds to tag fragments from individual cells. | Critical for pooling and splitting nuclei to achieve high-throughput single-cell resolution [33]. |

| DNase I or MNase | (For validation) Confirms chromatin accessibility patterns from ATAC-seq independently. | Used in parallel methods (e.g., DNase-seq) by ENCODE to map open chromatin [5]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Process raw sequencing data, assign gRNAs to cells, call accessibility peaks, and identify differential accessibility. | Custom computational methods were developed for mapping nucleosome positioning and TF dynamics [33] [32]. |

Spear-ATAC (Single-cell perturbations with an accessibility read-out using scATAC-seq) represents a significant methodological advancement that enables high-throughput single-cell chromatin accessibility CRISPR screening. This innovative approach allows researchers to simultaneously capture single-guide RNA (sgRNA) sequences and chromatin accessibility profiles from thousands of individual cells in parallel, providing unprecedented resolution for studying epigenetic responses to regulatory perturbations [34] [38].

This technology addresses a critical gap in functional genomics by enabling the assessment of how transcription factor perturbations affect chromatin states at single-cell resolution. Unlike previous methods limited to 96 cells per run, Spear-ATAC can process up to 80,000 nuclei in a single 10x Genomics Chromium Controller run, dramatically reducing costs from $9.80 per cell to just $0.46 per cell while increasing throughput [34]. This breakthrough is particularly valuable for cancer research, where understanding heterogeneous regulatory networks can reveal mechanisms driving oncogenesis and potential therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Spear-ATAC Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Product/Sequence | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral Vector | BstXI/BlpI-flanked sgRNA construct with Nextera adapters [39] | Ensures sgRNA detection independent of local chromatin accessibility |

| Specialized Oligos | oSP1735, oSP2053 (/Bio/), MCB1672 [39] | Enables exponential amplification of sgRNA fragments alongside linear ATAC-seq amplification |

| Cell Line | K562;dCas9-KRAB cells [34] | Provides inducible CRISPRi platform for transcription factor knockdown |

| Transposase | Hyperactive Tn5 [34] | Fragments open chromatin regions for sequencing library preparation |

| Barcoded Beads | 10x Gel Beads with nucleus-specific barcodes [38] | Enables single-cell partitioning and barcoding in GEMs |

| Sequencing Primers | Illumina Nextera Read 1/Read 2, i7 Sample Index Plate [39] | Facilitates library amplification and multiplexed sequencing |

Technical FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

sgRNA Detection Issues

Q: What can cause low sgRNA detection rates in Spear-ATAC experiments?

Low sgRNA detection typically stems from suboptimal amplification or capture efficiency. The Spear-ATAC protocol addresses this through several key modifications:

- Solution: Implement the specialized oligo system with biotin-tagged primers during targeted sgRNA amplification to enrich specific fragments while minimizing background from scATAC-seq reads [34].

- Solution: Increase in-GEM linear amplification cycles from 12 to 15, which subsequently adds three rounds of exponential sgRNA amplification without compromising scATAC-seq quality [34].

- Solution: Flank lentiviral sgRNA spacers with pre-integrated Nextera Read1 and Read2 adapters to ensure amplification regardless of local chromatin context, improving sgRNA detection by approximately 4-fold [34].

- Troubleshooting Note: Consistently low detection across all samples may indicate issues with the reverse oligo specific to the sgRNA backbone, which should be verified for sequence accuracy.

Q: How specific are sgRNA-to-cell assignments in Spear-ATAC?

The original Spear-ATAC publication demonstrated high assignment specificity (>80%), with 48% of captured nuclei (3,045 of 6,390) successfully linked to their corresponding sgRNA in a pilot experiment targeting GATA1 and GATA2 [34]. Specificity can be confirmed through:

- UMAP visualization clearly distinguishing cells harboring different sgRNAs

- Expected chromatin accessibility changes at target transcription factor binding sites

- Validation using multiple sgRNAs targeting the same gene yielding consistent profiles

Experimental Design Considerations

Q: What factors influence CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency in chromatin context?

Chromatin accessibility significantly impacts CRISPR-Cas9 efficiency, which is particularly relevant for Spear-ATAC studies investigating epigenetic regulation:

- Chromatin State: Editing is more efficient in euchromatin than heterochromatin [3]. Closed, polycomb-mediated chromatin can reduce Cas9 binding and editing efficiency by 30-40% at certain target sites [27].

- gRNA Secondary Structure: Guide sequence self-folding can impede Cas9 binding and reduce cleavage activity [3] [40].

- Binding Free Energy: Optimal CRISPR-Cas9 activity occurs within a narrow binding free energy range that excludes extremely weak or strong bindings [40].

- PAM Context: Local Cas9 "sliding" on overlapping PAM sequences can either increase (upstream PAM) or decrease (downstream PAM) editing efficiency by approximately 12% [40].

Q: What timepoints are appropriate for assessing dynamic epigenetic responses?

Spear-ATAC enables temporal monitoring of epigenetic changes. The original study profiled responses at 3, 6, 9, and 21 days post-knockdown [34]. Selection of timepoints should consider:

- Early responses (3-6 days): Direct effects on transcription factor binding and immediate chromatin changes

- Intermediate responses (9 days): Stabilized regulatory network adaptations

- Late responses (21 days): Cell fate decisions and potential population selection effects

Protocol Optimization

Q: How can I optimize nuclei preparation for Spear-ATAC?

Proper nuclei preparation is critical for success:

- Isolation Method: Use gentle detergent-based lysis to preserve nuclear membrane integrity while removing cytoplasmic components

- Quality Control: Assess nuclei integrity and concentration before transposition using fluorescence-based counting methods

- Transposition Optimization: Titrate Tn5 enzyme concentration to balance fragment length distribution and library complexity

- Storage Considerations: Process fresh nuclei when possible; if necessary, flash-freeze in appropriate cryopreservation media

Q: What sequencing depth is recommended for Spear-ATAC libraries?

While the original publication doesn't specify exact sequencing metrics, based on standard scATAC-seq recommendations and the additional sgRNA reads:

- Target 25,000-50,000 read pairs per cell for chromatin accessibility profiling

- Ensure sufficient coverage for sgRNA detection (typically requiring less sequencing depth)

- Include additional cycles to fully sequence sgRNA barcodes and spacer regions

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Spear-ATAC experimental workflow highlighting key protocol modifications.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Performance Comparison Between Spear-ATAC and Alternative Methods

| Performance Metric | Spear-ATAC | Perturb-ATAC (Previous Method) | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cells per Run | Up to 80,000 nuclei [34] | 96 cells per run [34] | ~833x |

| Cost per Cell | $0.46 [34] | $9.80 [34] | ~21x reduction |

| sgRNA Detection | ~40-fold increase vs standard scATAC-seq [34] | Baseline | 40x |

| Cell-sgRNA Assignments | 48% of captured nuclei (3,045/6,390) [34] | Requires multiple batches | Single run sufficient |

| Run Time | 7 minutes on 10x Controller [34] | 4 hours per 96 cells on Fluidigm C1 [34] | ~34x faster |

| Multiplexing Capacity | 414 sgRNA knock-down populations in 104,592 cells [34] | Limited by throughput | Massive parallelization |

Application Example: GATA1 Perturbation Analysis

The foundational Spear-ATAC study demonstrated the technology's power through GATA1 perturbation in K562 leukemia cells, revealing how chromatin accessibility changes drive lineage decisions:

Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Engineering: K562 cells expressing dCas9-KRAB were transduced with lentiviral sgRNAs targeting GATA1 (3 guides), GATA2 (3 guides), and non-targeting controls (3 guides) [34]

- Culture Duration: Cells were expanded for 6 days post-transduction to allow epigenetic remodeling

- Cell Sorting: sgRNA+ cells were isolated using FACS before nuclei preparation

- Spear-ATAC Processing: Following the optimized protocol with modified amplification conditions

- Bioinformatic Analysis: sgRNA assignment followed by differential accessibility testing using chromVAR for motif deviation scores [34]

Key Findings:

- GATA1 knockdown identified 14,262 peaks (14.76%) increasing and 14,026 peaks (14.52%) decreasing in accessibility [34]

- Decreased accessibility regions were enriched for erythroid-specific genes, while increased accessibility regions associated with megakaryocyte-specific genes [34] [38]

- This suggested GATA1 knockdown pushes erythro-megakaryocytic progenitors toward megakaryocyte lineage, explaining clinical observations in GATA1 deficiency disorders [34]

Advanced Experimental Applications

Temporal Dynamics Assessment

Spear-ATAC enables unprecedented monitoring of epigenetic changes over time. The scalability of the method allows researchers to profile the same perturbation across multiple timepoints to distinguish direct regulatory effects from secondary adaptations:

Protocol for Timecourse Experiments:

- Introduce sgRNA library into target cells and collect samples at 3, 6, 9, and 21 days post-transduction

- Process all samples using standardized Spear-ATAC conditions

- Analyze both sgRNA representation (proliferation effects) and chromatin accessibility changes

- Construct temporal regulatory networks showing how perturbations propagate through epigenetic landscapes

Chromatin Accessibility Impact on gRNA Efficiency

Understanding how chromatin context affects CRISPR efficiency is fundamental for interpreting Spear-ATAC results and designing effective sgRNAs:

Diagram 2: Relationship between chromatin accessibility and CRISPR-Cas9 efficiency, with potential optimization strategies.

Spear-ATAC represents a transformative methodology that enables high-throughput functional epigenomics by linking CRISPR-mediated perturbations to chromatin accessibility outcomes at single-cell resolution. The technical solutions embedded in this protocol—including specialized adapter designs, optimized amplification conditions, and efficient sgRNA capture strategies—address previous limitations in scale and cost that hindered comprehensive epigenetic screening.

For researchers investigating gene regulatory networks in cancer and developmental systems, Spear-ATAC provides an unprecedented window into how transcription factor perturbations reshape the epigenetic landscape. The technology's compatibility with temporal analysis further enables dissection of direct versus indirect regulatory effects, offering powerful insights for both basic biology and therapeutic development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary factors that cause variations in gRNA efficiency in my CRISPR screens? gRNA efficiency is influenced by a combination of sequence-specific features, structural elements, and cellular context. Key factors include:

- Sequence Features: Nucleotide composition is critical; for example, adenine (A) counts and specific dinucleotides (AG, CA) are associated with higher efficiency, while excessive guanine (G) or uracil (U) counts and poly-N sequences (e.g., GGGG) are detrimental [41]. The presence of specific nucleotides at certain positions also matters; a 'G' in position 20 of the gRNA and a 'C' in the PAM (CGG) are associated with higher efficiency, while a 'T' in the PAM (TGG) is inefficient [41].

- gRNA Secondary Structure: The formation of secondary structures in the gRNA sequence itself can inhibit its function. Stable structures with low minimum folding energies (MFE < -7.5 kcal/mol) are unfavorable for Cas9 activity [3] [16].

- Chromatin Accessibility: This is a major determinant. Gene editing is consistently more efficient in open chromatin (euchromatin) compared to closed, silenced chromatin (heterochromatin) [3] [27]. In K562 cells, knocking down the transcription factor GATA1 in closed chromatin regions led to a significant reduction in editing efficiency [27].

FAQ 2: My screen in K562 cells identified a transcription factor hit. How can I distinguish its direct regulatory targets from indirect effects? To map direct regulatory targets, you need a method that can simultaneously capture the perturbation and a readout of the direct epigenetic consequences. The Spear-ATAC method is designed for this purpose [34]. It combines pooled CRISPR perturbations with single-cell ATAC-seq, allowing you to:

- Link individual sgRNAs to the chromatin accessibility profile of the cell in which it was expressed.

- Unbiasedly identify changes in transcription factor (TF) motif accessibility specific to your TF perturbation.

- Identify direct binding sites, as a TF's direct targets will show the most immediate and significant changes in accessibility upon its knockdown. For example, GATA1 knockdown in K562 cells directly decreased accessibility at peaks containing the GATA motif [34].

FAQ 3: Why do my validation experiments fail to replicate the strong phenotype from my primary CRISPR screen in K562 cells? This common issue often stems from poor gRNA efficiency or specificity during validation.

- Solution: Always use a state-of-the-art deep learning tool like CRISPRon for gRNA design. These models, trained on large-scale gRNA activity datasets, provide significantly more accurate predictions of on-target efficiency than older tools [16].

- Best Practice: For critical validation experiments, use synthetic sgRNAs in a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) format for delivery. This format enables the highest editing efficiencies and the most reproducible results, minimizing false negatives [42].

FAQ 4: How does chromatin state not only affect efficiency but also the outcome of Cas9 editing? Evidence suggests that closed chromatin does more than just reduce the frequency of indels; it can also alter the spectrum of mutations. One study found that while the types of mutations (primarily small deletions) were similar in open and closed chromatin, the frequency and range of affected nucleotides were higher in open chromatin. However, the most common mutation (a 1-bp deletion) was the same in both states, indicating that the fundamental mechanism of repair is not changed, but the accessibility influences the efficiency of the process [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Editing Efficiency in Heterochromatic Regions

Issue: Your target site is located in a region with low chromatin accessibility, leading to poor Cas9 binding and editing.

Solutions:

- Predict and Avoid: Before experimentation, use chromatin accessibility data (e.g., from public ATAC-seq or DNase-seq datasets for K562 cells) to inform your gRNA design. Prioritize targets in open chromatin regions.

- Modulate Chromatin State:

- Protocol: Co-express chromatin-modulating proteins with your CRISPR components. For example, co-deliver a plasmid encoding a transcriptional activator or a histone demethylase specific to your target region.

- Rationale: Artificially opening the chromatin landscape can restore editing efficiency. Research has shown that artificial reversal of a silenced state restores Cas9-mediated editing [27].

- Considerations: This approach adds complexity and requires careful controls to ensure the modulator itself does not cause confounding phenotypic effects.

Problem: High Off-Target Effects in Genome-Wide Screens

Issue: Your screen results have an unacceptably high number of false positives, likely due to gRNAs with low specificity.

Solutions:

- Optimize gRNA Design:

- Use modern prediction tools (e.g., CRISPRon) that incorporate both on-target efficiency and off-target specificity scores during the design phase [16].

- Avoid gRNAs with significant homology to multiple genomic sites, even with 1-2 mismatches.

- Use High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Employ engineered Cas9 nucleases (e.g., eSpCas9(1.1)) that have been designed to reduce off-target cleavage while maintaining high on-target activity. One study found that eSpCas9(1.1) showed editing efficiency advantages in heterochromatin, though the main challenge remained chromatin accessibility itself [3].

- Utilize RNP Delivery: Delivering pre-complexed, synthetic sgRNAs with Cas9 protein (RNP format) reduces the time the nuclease is active in the cell, which can decrease off-target effects compared to plasmid-based delivery [42].

The tables below summarize key quantitative findings from research on factors affecting CRISPR screen outcomes in K562 and other cell models.

Table 1: Impact of Chromatin State on Cas9 Editing Efficiency

| Chromatin State | Experimental System | Effect on Editing Efficiency | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fully Silenced (Closed) | GAL4EED HEK293 Model [27] | Significant reduction (editing undetectable near TSS) | Editing at TSS-proximal sites dropped from 7.5-55.1% in open chromatin to below detection limits in closed chromatin. |

| Partially Silenced | GAL4EED HEK293 Model [27] | Moderate reduction | Editing efficiency was intermediate between open and fully silenced states. |

| Open (Euchromatin) | Multiple cell lines (HEK293T, HeLa, fibroblasts) [3] | Highly efficient | Gene editing is consistently more efficient in euchromatin compared to heterochromatin. |

Table 2: Key Sequence and Structural Features Influencing gRNA Efficiency [41] [16]

| Feature Category | Associated with Higher Efficiency | Associated with Lower Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide Content | High 'A' count; Specific dinucleotides (AG, CA, AC, UA) | High 'U' and 'G' count; Poly-N sequences (e.g., GGGG); Specific dinucleotides (UU, GC) |

| Positional Nucleotides | 'G' at position 20; 'A' at position 20; 'C' in PAM (CGG) | 'C' at position 20; 'U' at positions 17-20; 'T' in PAM (TGG) |