Building the Future of Materials Science: A Guide to Data Infrastructure for Research and Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the development, application, and challenges of modern materials data infrastructure.

Building the Future of Materials Science: A Guide to Data Infrastructure for Research and Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the development, application, and challenges of modern materials data infrastructure. Aimed at researchers and development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of systems like HTEM-DB and Kadi4Mat, details methodological workflows for data collection and analysis, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies for data heterogeneity and standards, and examines validation frameworks such as the JARVIS-Leaderboard. By synthesizing insights from academia, government, and industry, this guide serves as a roadmap for leveraging robust data infrastructure to accelerate innovation in materials science and its applications in fields like drug development.

The Pillars of Progress: Exploring the Core Concepts of Materials Data Infrastructure

Modern Materials Data Infrastructure (MDI) represents a fundamental shift from traditional, static data repositories towards a dynamic, interconnected ecosystem designed to accelerate innovation in materials science and engineering. The U.S. National Science Foundation identifies MDI as crucial for advancing materials discovery, enabling data to be used as input for modeling, as a medium for knowledge discovery, and as evidence for validating predictive theories [1]. This infrastructure encompasses the software, hardware, and data standards necessary to enable the discovery, access, and use of materials science and engineering data, going far beyond simple storage to become an active component of the research lifecycle itself [1].

The transformation toward this modern infrastructure is driven by three key factors: improvements in AI-driven solutions leveraged from other sectors, significant advancements in data infrastructures, and growing awareness of the need to keep pace with accelerating innovation cycles [2]. As the field of materials informatics continues to expand—projected to grow at a CAGR of 9.0% through 2035—the development of robust MDI has become not just advantageous but essential for maintaining competitive advantage in materials research and development [2].

Core Components of a Modern MDI

A modern Materials Data Infrastructure comprises several integrated components that work in concert to support the entire research data lifecycle. These elements transform raw data into actionable knowledge through systematic organization and accessibility.

Distributed Data Repositories

Unlike centralized archives, modern MDI employs a federated architecture of highly distributed repositories that house materials data generated by both experiments and calculations [1]. This distributed approach allows specialized communities to maintain control and quality over their respective data domains while ensuring interoperability through shared standards and protocols. The infrastructure should allow online access to materials data to provide information quickly and easily, supporting diverse research needs across institutional and geographical boundaries [1].

Community-Developed Standards

Interoperability represents a cornerstone of effective MDI, achieved through community-developed standards that provide the format, metadata, data types, criteria for data inclusion and retirement, and protocols necessary for seamless data transfer [1]. These standards encompass:

- Data Format Standards: Ensuring consistent structure and organization of materials data

- Metadata Schemas: Capturing essential experimental context and parameters

- Ontologies and Taxonomies: Enabling semantic interoperability across domains

- Data Quality Guidelines: Establishing criteria for data fitness for purpose

Data Integration and Workflow Tools

Modern MDI includes methods for capturing data, incorporating these methods into existing workflows, and developing and sharing workflows themselves [1]. This component focuses on the practical integration of infrastructure into daily research practices, including:

- Electronic Laboratory Notebooks (ELNs) and Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) that serve as data capture points [2]

- Automated data pipelines that streamline the flow from instrumentation to repositories

- Workflow management systems that enable the reproduction and adaptation of analytical processes

- APIs and integration frameworks that connect disparate tools and systems

Table 1: Core Components of Modern Materials Data Infrastructure

| Component Category | Key Functions | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Data Storage & Access | Distributed repository management, Data discovery, Access control | Online data portals, Federated search, Authentication systems |

| Standards & Interoperability | Data formatting, Metadata specification, Vocabulary control | Community-developed schemas, Open data formats, Materials ontologies |

| Research Tools & Integration | Data capture, Workflow management, Analysis integration | ELN/LIMS software, Computational workflows, API frameworks |

Quantitative Framework for MDI Assessment

Evaluating the effectiveness and maturity of Materials Data Infrastructure requires both quantitative metrics and qualitative assessment frameworks. The strategic value of MDI investments can be measured through their impact on research efficiency, data reuse potential, and acceleration of discovery cycles.

Performance Metrics for MDI Implementation

The table below outlines key quantitative indicators for assessing MDI performance across multiple dimensions, from data accessibility to research impact. These metrics help organizations track progress and identify areas for infrastructure improvement.

Table 2: Materials Data Infrastructure Assessment Metrics

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Target Values |

|---|---|---|

| Data Accessibility | Time to discover relevant datasets, Percentage of data with structured metadata, API response time | <5 minutes for discovery, >90% with metadata, <2 second API response |

| Data Quality | Compliance with community standards, Completeness of metadata, Error rates in datasets | >95% standards compliance, >85% metadata completeness, <1% error rate |

| Research Impact | Reduction in experiment repetition, Time to materials development, Data citation rates | >40% reduction in repetition, >50% faster development, Increasing citations |

| Interoperability | Number of integrated tools, Successful data exchanges, Cross-repository queries | >10 integrated tools, >95% successful exchange, Cross-repository capability |

Materials Informatics Market Context

The growing importance of MDI is reflected in market projections for materials informatics, which relies fundamentally on robust data infrastructure. The global market for external provision of materials informatics services is forecast to grow at 9.0% CAGR, reaching significant market value by 2034 [2]. This growth underscores the strategic importance of MDI as an enabling foundation for data-centric materials research approaches.

Experimental Protocols for MDI Implementation

Implementing an effective Materials Data Infrastructure requires systematic approaches to data capture, management, and sharing. The following protocols provide detailed methodologies for establishing MDI components within research organizations.

Protocol 1: Materials Data Capture and Metadata Annotation

Objective: To standardize the capture of experimental materials data with sufficient metadata to enable reuse and reproducibility.

Materials and Reagents:

- Electronic Laboratory Notebook (ELN) system with customized materials science templates

- Standardized metadata schema (e.g., MODA - Materials Omni Data Annotation)

- Unique identifier system for samples and experiments

- Automated data capture interfaces for instrumentation

Procedure:

- Sample Registration: Assign a unique, persistent identifier to each new material sample using the institutional identifier system. Record core sample characteristics including composition, synthesis method, and date of creation.

- Experimental Design Documentation: Using the ELN template, document the hypothesis, experimental objectives, and controlled variables before commencing experimentation.

- Instrumentation Setup: Configure automated data capture from analytical instruments where possible, ensuring instrument calibration data is recorded simultaneously.

- Metadata Annotation: Upon data generation, annotate datasets using the standardized metadata schema, capturing:

- Experimental conditions and parameters

- Instrument specifications and settings

- Data processing methods applied

- Personnel and institutional information

- Quality Validation: Perform automated quality checks on captured data using predefined validation rules for completeness and format compliance.

- Repository Submission: Submit validated data and metadata to the appropriate institutional or community repository, obtaining a persistent dataset identifier.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If metadata completeness falls below 85%, review annotation interface design and provide additional researcher training

- For instrument integration challenges, implement intermediate data transformation scripts to convert proprietary formats to standard representations

- If data reuse rates remain low, conduct interviews with researchers to identify metadata gaps or usability issues

Protocol 2: Cross-Repository Data Federation and Integration

Objective: To enable seamless discovery and access to materials data across distributed repositories through standardized federation protocols.

Materials and Reagents:

- Repository federation middleware

- Common API specifications (e.g., Materials API - MAPI)

- Authentication and authorization infrastructure

- Distributed query optimization engine

Procedure:

- Repository Registration: Register each participating repository in the federation registry, specifying available data domains, access policies, and technical capabilities.

- Standard API Implementation: Implement common API specifications across all participating repositories, ensuring consistent response formats and error handling.

- Metadata Harmonization: Map repository-specific metadata schemas to a common core schema to enable cross-repository searching while preserving domain-specific extensions.

- Query Federation Setup: Configure the distributed query engine to decompose cross-repository queries into individual repository queries with appropriate optimization.

- Result Integration: Implement result aggregation and ranking algorithms to present unified results from multiple repositories.

- Access Control Integration: Establish trust relationships between identity providers and service providers to enable seamless authentication across repository boundaries.

Validation Methods:

- Execute test queries spanning multiple repositories and verify result completeness

- Measure response times for distributed versus local queries and optimize as needed

- Validate that access controls are properly enforced across federation boundaries

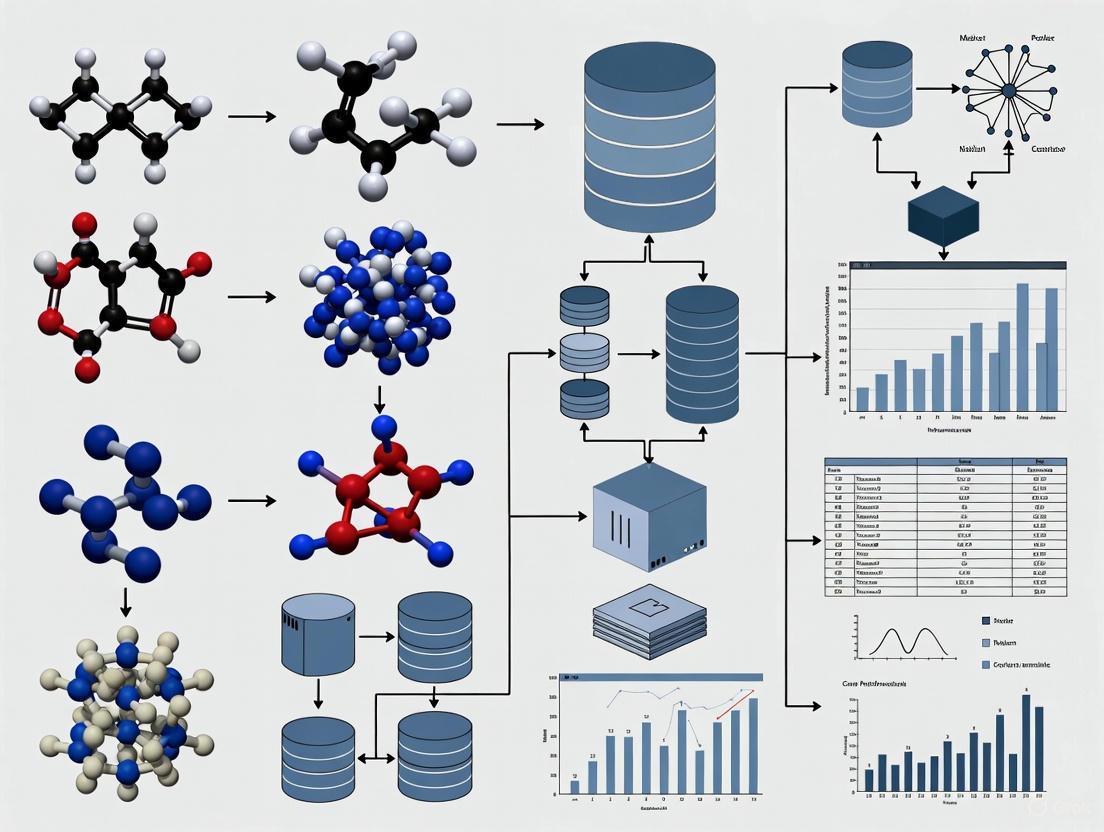

Visualization Framework for MDI

The following diagrams illustrate key relationships, workflows, and architectural patterns in modern Materials Data Infrastructure, created using DOT language with specified color palette and contrast requirements.

MDI Component Architecture

Materials Data Lifecycle Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of modern Materials Data Infrastructure requires both technical components and human processes. The following table details key solutions and their functions in establishing effective MDI.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Materials Data Infrastructure

| Solution Category | Specific Tools/Components | Function in MDI |

|---|---|---|

| Data Management Platforms | ELN/LIMS with materials extensions, Repository software, Data governance tools | Capture experimental context, Manage data lifecycle, Enforce policies |

| Interoperability Standards | Community metadata schemas, Data exchange formats, Materials ontologies | Enable data integration, Facilitate cross-domain discovery, Support semantic reasoning |

| Analysis & AI Tools | Machine learning frameworks, Materials-specific algorithms, Visualization packages | Extract insights from data, Build predictive models, Enable interactive exploration |

| Integration Middleware | API gateways, Repository federation tools, Identity management systems | Connect disparate systems, Enable cross-repository search, Manage access control |

Modern Materials Data Infrastructure represents a transformative approach to managing the complex data ecosystems of contemporary materials research. By moving beyond simple repositories to create integrated, standards-based infrastructures that support the entire research lifecycle, organizations can significantly accelerate materials discovery and development. The implementation of such infrastructure requires careful attention to both technical components and cultural factors, including the development of shared standards, distributed repository architectures, and researcher-centered tools.

As the materials informatics field continues to evolve—projected to grow substantially in the coming years—the organizations that invest in robust, flexible MDI will be best positioned to leverage emerging opportunities in AI, automation, and data-driven discovery [2]. The protocols, metrics, and architectures outlined in this document provide a foundation for building this critical research infrastructure, enabling materials scientists to fully harness the power of their data for innovation.

Within the paradigm of the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI), the development of robust materials data infrastructures has become a cornerstone for accelerating discovery and innovation [3]. These infrastructures are essential for transitioning from traditional, siloed research methods to a data-driven, collaborative model that embraces the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) [4] [5]. This application note details the operational frameworks, experimental protocols, and practical implementations of two exemplary systems that exemplify this transition: Kadi4Mat, a generic virtual research environment, and the High-Throughput Experimental Materials Database (HTEM-DB), a specialized repository for combinatorial data. By examining these systems in action, we provide a blueprint for the research community on deploying infrastructures that effectively manage the entire research data lifecycle, from acquisition and analysis to publication and reuse.

Kadi4Mat: A Unified Virtual Research Environment

Kadi4Mat (Karlsruhe Data Infrastructure for Materials Sciences) is an open-source virtual research environment designed to support researchers throughout the entire research process [4] [5]. Its primary objective is to combine the features of an Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) with those of a research data repository, creating a seamless workflow from data generation to publication.

The infrastructure is logically divided into two core components: the repository, which focuses on the management and exchange of data (especially "warm data" that is yet to be fully analysed), and the ELN, which facilitates the automated and documented execution of heterogeneous workflows for data analysis, visualization, and transformation [4] [5]. Kadi4Mat is architected as a web- and desktop-based system, offering both a graphical user interface and a programmatic API, thus catering to diverse user preferences and automation needs [4]. A key design philosophy is its generic nature, which, although originally developed for materials science, allows for adaptation to other research disciplines [4] [5].

HTEM-DB: A Domain-Specific Repository for Combinatorial Workflows

The High-Throughput Experimental Materials Database (HTEM-DB) is a public repository for inorganic thin-film materials data generated from combinatorial experiments at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) [6] [7] [8]. It serves as the endpoint for a specialized Research Data Infrastructure (RDI), a suite of custom data tools that collect, process, and store experimental data and metadata [7] [8]. The goal of HTEM-DB and its underlying RDI is to establish a structured pipeline for high-throughput data, making valuable experimental data accessible for future data-driven studies, including machine learning [6] [8]. This system is a prime example of a domain-specific infrastructure built to support a particular class of experimental methods, thereby aggregating and preserving high-quality datasets for the broader research community.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Kadi4Mat and HTEM-DB

| Feature | Kadi4Mat | HTEM-DB / NREL RDI |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Generic virtual research environment (VRE) combining ELN and repository [5] | Specialized repository for inorganic thin-film materials from combinatorial experiments [7] |

| Core Components | Repository component & ELN component with workflow automation [4] | Custom data tools forming a Research Data Infrastructure (RDI) [8] |

| Architecture | Web-based & desktop-based; GUI and API [4] | Integrated data tools pipeline connected to experimental instruments [7] |

| Key Application | Management and analysis of any research data; FAIR RDM [5] | Aggregation and sharing of high-throughput experimental data for machine learning [6] |

| Licensing | Open Source (Apache 2.0) [4] | Not Specified in Sources |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Executing a Reproducible Machine Learning Workflow in Kadi4Mat

The following protocol details the process of setting up and running a reproducible machine learning workflow for the virtual characterization of solid electrolyte interphases (SEI) within the Kadi4Mat environment, as demonstrated in associated research [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for the ML Workflow in Kadi4Mat

| Item / Tool | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| KadiStudio | A tool within the Kadi ecosystem for data organization, processing, and analysis [5]. |

| Variational AutoEncoder (VAE) | A neural network architecture used to learn descriptive, data-driven representations (latent space) of the SEI configurations [5]. |

| Property Regressor (prVAE) | An integrated component that trains the VAE's latent space to correlate with target physical properties of the SEI [5]. |

| Kinetic Monte Carlo (KMC) Simulation Data | Provides the physical and stochastic attributes of SEI configurations, serving as the foundational dataset for training [5]. |

| RDM-Assisted Workflows | Workflows that leverage the Research Data Management infrastructure to automatically create knowledge graphs linking data provenance [5]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Ingestion and Structuring:

- Initiate a new project in the Kadi4Mat ELN component using KadiStudio.

- Import the raw SEI configuration data generated from Kinetic Monte Carlo simulations into the project. This data includes physiochemical properties such as thickness, porosity, density, and volume fraction.

- Use Kadi4Mat's data management features to structure and annotate the dataset with relevant metadata, ensuring compliance with FAIR principles.

Workflow Design and Configuration:

- In the Kadi4Mat graphical node editor, define the machine learning workflow. The key steps are outlined in the diagram below.

- Add a data preprocessing node to clean and normalize the KMC simulation data.

- Configure the core model node, a Variational AutoEncoder with an integrated property regressor (prVAE). The objective is for the VAE to learn a compressed, data-driven representation (latent space) of the SEI structures, while the regressor ensures this representation is predictive of the target physical properties.

Model Training and Execution:

- Parameterize the workflow nodes, specifying hyperparameters for the prVAE (e.g., learning rate, latent space dimension).

- Initiate the workflow execution via Kadi4Mat's process manager. The system will handle the execution of the defined steps, potentially leveraging integrated computing infrastructure.

- The prVAE model is trained to minimize reconstruction loss of the SEI configurations and the error in predicting the physical properties from the latent space.

Analysis and Knowledge Graph Generation:

- Upon completion, the workflow outputs the trained model and analysis results back into the Kadi4Mat repository.

- Automatically, the RDM-assisted workflow generates a knowledge graph that records the provenance, linking the raw KMC data, the specific prVAE model architecture and hyperparameters, and the final results [5].

- Analyze the latent space of the trained VAE to investigate how the observable SEI characteristics affect the learned data-driven characteristics.

Protocol 2: Data Acquisition and Curation in the HTEM-DB Framework

This protocol describes the end-to-end process of generating, processing, and publishing high-throughput experimental materials data, as implemented by the Research Data Infrastructure (RDI) at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) that feeds into the HTEM-DB [7] [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for the HTEM-DB Data Pipeline

| Item / Tool | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Combinatorial Deposition System | A high-throughput instrument for synthesizing thin-film materials libraries with varied composition gradients [7]. |

| Characterization Tools (e.g., XRD, XRF) | Instruments (e.g., X-ray Diffraction, X-ray Fluorescence) used to rapidly characterize the structure and composition of the materials libraries [7]. |

| Custom Data Parsers | Software tools within the RDI that automatically extract and standardize raw data and metadata from experimental instruments [7] [8]. |

| HTEM-DB Repository | The public-facing endpoint repository that stores the processed, curated, and published datasets for community access [6] [7]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

High-Throughput Experimentation:

- Utilize a combinatorial deposition system to synthesize a library of inorganic thin-film samples. This process systematically varies precursor concentrations or deposition parameters across a substrate to create a wide array of compositions in a single experiment.

- Employ high-throughput characterization tools, such as X-ray Diffraction (XRD) and X-ray Fluorescence (XRF), to rapidly collect structural and compositional data from the synthesized materials library.

Automated Data Collection and Processing:

- The custom RDI tools are integrated with the combinatorial and characterization instruments. Upon experiment completion, data parsers automatically collect the raw data output and associated experimental metadata.

- The RDI processes this data, which includes converting proprietary instrument formats into standardized, machine-readable data formats and performing initial calculations or data validation.

Data Curation and Internal Storage:

- Processed data and comprehensive metadata are stored in an internal, structured data store within the RDI. This step involves linking all related data files and their metadata to ensure data integrity and context.

- Researchers can access and perform preliminary analysis on this curated data internally before public release.

Publication to Public Repository:

- Once the data is verified and ready for public access, it is transferred from the internal RDI to the public HTEM-DB repository.

- The HTEM-DB serves as the permanent, public access point for the dataset, making it findable and accessible to the wider research community. This final step maximizes the data's usefulness for future machine learning and data-driven studies.

Technical Specifications and Data Outputs

The value of a research data infrastructure is ultimately demonstrated by the quality, scale, and accessibility of the data and analyses it supports. The following tables quantify the outputs of the JARVIS infrastructure (a comparable large-scale system) and the Kadi4Mat platform.

Table 4: Quantitative Data Output of the JARVIS Infrastructure (as of 2020) [3]

| JARVIS Component | Scope | Key Calculated Properties |

|---|---|---|

| JARVIS-DFT | ≈40,000 materials | ≈1 million properties including formation energies, bandgaps (GGA and meta-GGA), elastic constants, piezoelectric constants, dielectric constants, exfoliation energies, and spectroscopic limited maximum efficiency (SLME) [3]. |

| JARVIS-FF | ≈500 materials; ≈110 force-fields | Properties for force-field validation: bulk modulus, defect formation energies, and phonons [3]. |

| JARVIS-ML | ≈25 ML models | Models for predicting material properties such as formation energies, bandgaps, and dielectric constants using Classical Force-field Inspired Descriptors (CFID) [3]. |

Table 5: Application-Based Outputs from Kadi4Mat Use Cases

| Research Application | Implemented Workflow / Analysis | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| ML-assisted Design of Experiments | Bayesian optimization workflow to guide the synthesis of solid-state electrolytes by varying precursor concentrations, sintering temperature, and holding time [5]. | Discovery of a sample with high ionic conductivity after fewer experimental iterations, demonstrating accelerated materials discovery [5]. |

| Enhancing Spectral Data Analysis | Machine learning (logistic regression) workflow to classify material components and identify key ions from Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) data [5]. | Accurate prediction of new sample compositions, simplifying the analysis of complex characterization data [5]. |

The Critical Role of Metadata and FAIR Principles

The exponential growth of data in materials science presents both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges for research and drug development. With global data creation expected to surpass 390 zettabytes by 2028, the scientific community faces a critical bottleneck in managing, sharing, and extracting value from complex materials data [9]. The FAIR Guiding Principles—Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—represent a transformative framework for enhancing data utility in materials database infrastructure development [9] [10].

Originally formalized in 2016 through a seminal publication in Scientific Data, these principles emerged from the need to optimize data reuse by both humans and computational systems [9] [11]. For materials researchers and drug development professionals, implementing FAIR principles addresses fundamental challenges in data fragmentation, reproducibility, and integration across multi-modal datasets encompassing genomic sequences, imaging data, and clinical trials [11]. This application note provides detailed protocols and frameworks for implementing FAIR principles within materials science research contexts, enabling robust data management practices that accelerate innovation.

Core Principles and Definitions

The FAIR Framework

The FAIR principles establish a comprehensive set of guidelines for scientific data management and stewardship, with particular emphasis on machine-actionability [10]. The core components are:

- Findable: Data and metadata should be easily discoverable by both humans and computers through assignment of persistent identifiers and rich, searchable metadata [9] [10].

- Accessible: Once identified, data should be retrievable using standardized, open protocols that support authentication and authorization where necessary [11] [10].

- Interoperable: Data must be structured using formal, accessible, shared languages and vocabularies to enable integration with other datasets and analytical tools [9] [10].

- Reusable: Data should be richly described with accurate attributes, clear usage licenses, and detailed provenance to enable replication and combination in new contexts [11] [10].

A key differentiator of FAIR principles is their focus on machine-actionability—the capacity of computational systems to autonomously find, access, interoperate, and reuse data with minimal human intervention [10]. This capability is increasingly critical as research datasets grow in scale and complexity beyond human processing capabilities.

Key Terminology

Table: Essential FAIR Implementation Terminology

| Term | Definition | Relevance to Materials Science |

|---|---|---|

| Machine-actionable | Capability of computational systems to operate on data with minimal human intervention [10] | Enables high-throughput screening and AI-driven materials discovery |

| Persistent Identifier | Globally unique and permanent identifier (e.g., DOI, Handle) for digital objects [10] | Ensures permanent access to materials characterization data and protocols |

| Metadata | Descriptive information about data, providing context and meaning [9] [10] | Critical for documenting experimental conditions, parameters, and methodologies |

| Provenance | Information about entities, activities, and people involved in producing data [10] | Tracks materials synthesis pathways and processing history for reproducibility |

| Interoperability | Ability of data or tools from different sources to integrate with minimal effort [10] | Enables cross-domain research integrating chemical, physical, and biological data |

Quantitative Framework for FAIR Implementation

FAIR Principles Specification

Table: Detailed FAIR Principles Breakdown with Implementation Metrics

| Principle | Component | Technical Specification | Implementation Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Findable | F1: Persistent Identifiers | Globally unique identifiers (DOI, UUID) assigned to all datasets [10] | 100% identifier assignment rate; 0% identifier decay |

| F2: Rich Metadata | Domain-specific metadata schemas with required and optional fields [9] | Minimum 15 descriptive elements per dataset | |

| F3: Identifier Inclusion | Metadata explicitly includes identifier of described data [10] | 100% metadata-record linkage verification | |

| F4: Searchable Resources | Registration in indexed, searchable repositories [10] | Indexing in ≥3 disciplinary search engines | |

| Accessible | A1: Retrievable Protocol | Standardized communications protocol (HTTP, FTP) [10] | Protocol availability ≥99.5%; maximum 2-second retrieval latency |

| A1.1: Open Protocol | Protocol open, free, universally implementable [10] | No proprietary barriers; documented API | |

| A1.2: Authentication | Authentication/authorization procedure where necessary [10] | Role-based access control with OAuth 2.0 compliance | |

| A2: Metadata Access | Metadata remains accessible even when data unavailable [10] | 100% metadata preservation independent of data status | |

| Interoperable | I1: Knowledge Representation | Formal, accessible, shared language for representation [10] | Use of RDF, JSON-LD, or domain-specific standardized formats |

| I2: FAIR Vocabularies | Vocabularies that follow FAIR principles [12] | ≥90% terms mapped to community-approved ontologies | |

| I3: Qualified References | Qualified references to other (meta)data [10] | Minimum contextual relationships documented per dataset | |

| Reusable | R1: Rich Attributes | Plurality of accurate, relevant attributes [10] | Minimum 10 provenance elements; complete methodology documentation |

| R1.1: Usage License | Clear, accessible data usage license [9] [10] | 100% license assignment; machine-readable license formatting | |

| R1.2: Detailed Provenance | Association with detailed provenance [10] | Complete workflow documentation from materials synthesis to characterization | |

| R1.3: Community Standards | Meeting domain-relevant community standards [10] | Compliance with ≥2 materials science metadata standards |

Implementation Metrics and Benchmarks

Recent studies indicate that systematic implementation of FAIR principles can reduce data discovery and processing time by up to 60%, while improving research reproducibility metrics by 45% [11]. The Oxford Drug Discovery Institute demonstrated that FAIR data implementation reduced gene evaluation time for Alzheimer's drug discovery from several weeks to just a few days [11]. Furthermore, researchers accessing FAIR genomic data from the UK Biobank and Mexico City Prospective Study achieved false positive rates of less than 1 in 50 subjects tested, highlighting the significant impact on data quality and reliability [11].

Experimental Protocols for FAIR Implementation

Protocol 1: FAIRification of Legacy Materials Data

Objective: Transform existing materials datasets into FAIR-compliant resources to enhance discoverability, interoperability, and reuse potential.

Materials and Equipment:

- Source materials datasets (structural, compositional, property data)

- Metadata extraction tools (OpenRefine, METS)

- Domain ontologies (ChEBI, NanoParticle Ontology, Materials Ontology)

- Repository platform (Dataverse, FigShare, institutional repository)

- Persistent identifier service (DataCite, EZID)

Procedure:

Data Inventory and Assessment

- Catalog all existing datasets with current format, size, and structure documentation

- Assess metadata completeness against domain-specific standards

- Identify gaps in documentation and provenance information

Identifier Assignment

- Assign persistent identifiers (DOIs) to each discrete dataset

- Ensure identifiers are embedded in both metadata and file headers

- Register identifiers with relevant disciplinary indexes

Metadata Enhancement

- Map existing metadata to community-standard schemas (e.g., Dublin Core, DataCite)

- Enrich with controlled vocabulary terms from domain ontologies

- Add experimental context, methodology, and instrument parameters

Format Standardization

- Convert proprietary formats to open, non-proprietary standards (e.g., CSV instead of Excel, CIF for crystallographic data)

- Ensure machine-readability through structured formatting

- Validate format compatibility with target analysis tools

Provenance Documentation

- Document data lineage from generation through processing stages

- Record all transformations, calculations, and normalization procedures

- Attribute contributions with ORCID identifiers where applicable

Repository Deposition

- Select appropriate disciplinary or general repository

- Upload datasets with complete metadata

- Set appropriate access controls and usage licenses

Validation and Testing

- Verify identifier resolution and metadata retrieval

- Test data access through API endpoints

- Validate interoperability with target analysis platforms

Troubleshooting:

- For heterogeneous data formats, implement intermediate conversion layers

- When domain ontologies are incomplete, extend with local terms mapped to upper-level ontologies

- For large datasets (>1TB), implement scalable storage with parallel access capabilities

Protocol 2: FAIR-Compliant Materials Research Workflow

Objective: Establish an end-to-end FAIR data management process for new materials research projects, from experimental design through data publication.

Materials and Equipment:

- Electronic Laboratory Notebook (ELN) system

- Sample tracking and management system

- Instrument data capture interfaces

- Metadata templates specific to materials characterization techniques

- Data repository with API access

Procedure:

Experimental Design Phase

- Pre-register study design with objectives and methodology

- Create project-specific metadata template incorporating domain standards

- Define data collection protocols with required metadata fields

Sample Preparation Documentation

- Record synthesis methods with complete parameter documentation

- Document precursor materials with source and purity information

- Assign unique sample identifiers linked to experimental conditions

Data Collection and Capture

- Configure instruments to output standardized metadata headers

- Implement automated metadata extraction where feasible

- Associate raw data with instrument calibration and configuration details

Processing and Analysis

- Record all data transformation steps with parameter documentation

- Maintain linkage between raw and processed data versions

- Document analysis algorithms with version and parameter information

Quality Assessment

- Implement automated quality control checks for data completeness

- Validate metadata against required schema elements

- Verify data integrity through checksum validation

Publication and Sharing

- Select appropriate access controls based on data sensitivity

- Apply machine-readable usage license (e.g., Creative Commons)

- Publish to designated repository with complete metadata

Preservation and Sustainability

- Migrate to preservation formats where necessary

- Establish refreshment schedule for storage media

- Monitor identifier persistence and repository stability

Validation:

- Conduct peer review of dataset completeness and documentation

- Test independent researcher ability to understand and reuse data

- Verify computational agent access and interpretation capabilities

Visualization of FAIR Implementation Workflow

FAIR Data Management Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integration of FAIR principles throughout the research data lifecycle, showing how specific FAIR components map to different stages of data management from planning through preservation.

Research Reagent Solutions for FAIR Implementation

Table: Essential Tools and Platforms for FAIR Materials Data Management

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | FAIR Compliance Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Lab Notebooks | RSpace, LabArchives, eLABJournal | Experimental documentation and data capture | Metadata templates, protocol standardization, export to repositories |

| Metadata Management | CEDAR, ISA Framework, OMeta | Structured metadata creation and validation | Ontology integration, standards compliance, template management |

| Persistent Identifiers | DataCite, Crossref, ORCID | Unique identification of data, publications, and researchers | DOI minting, metadata persistence, resolution services |

| Data Repositories | FigShare, Dataverse, Zenodo, Materials Data Facility | Data publication, preservation, and access control | PID assignment, standardized APIs, metadata standards support |

| Ontology Services | BioPortal, OLS, EBI Ontology Lookup Service | Vocabulary management and semantic integration | SKOS/RDF formats, ontology mapping, API access |

| Workflow Management | SnakeMake, Nextflow, Taverna | Computational workflow documentation and execution | Provenance capture, parameter documentation, version control |

| Data Transformation | OpenRefine, Frictionless Data, Pandas | Data cleaning, format conversion, and structure normalization | Format standardization, metadata extraction, quality assessment |

Implementation Case Studies and Best Practices

Successful FAIR Implementation in Research Infrastructures

The AnaEE (Analysis and Experimentation on Ecosystems) Research Infrastructure demonstrates effective FAIR implementation through its focus on semantic interoperability in ecosystem studies [12]. By employing standardized vocabularies and structured metadata templates, AnaEE enables cross-site data integration and analysis, directly supporting the Interoperability and Reusability pillars of FAIR.

Similarly, DANS (Data Archiving and Networked Services) transitioned from a generic repository system (EASY) to discipline-specific "Data Stations" with custom metadata fields and controlled vocabularies [12]. This approach significantly improved metadata quality and interoperability while maintaining FAIR compliance through multiple export formats (DublinCore, DataCite, Schema.org) and Dataverse software implementation.

Best Practices for Materials Science

Early Integration: Incorporate FAIR considerations during experimental design rather than post-hoc implementation [9]. This includes selecting appropriate metadata standards, file formats, and repositories at project inception.

Structured Metadata: Utilize domain-specific metadata standards such as the Materials Metadata Curation Guide or Crystallographic Information Framework (CIF) to ensure consistency and interoperability [9] [10].

Provenance Documentation: Implement comprehensive tracking of materials synthesis parameters, processing conditions, and characterization methodologies to enable replication and validation [10].

Collaborative Stewardship: Engage data stewards with specialized knowledge in data governance and FAIR implementation to navigate technical and organizational challenges [9].

Tool Integration: Leverage computational workflows that automatically capture and structure metadata during data generation, reducing manual entry and improving compliance [13].

The implementation of FAIR principles within materials database infrastructure represents a paradigm shift in research data management, enabling unprecedented levels of data sharing, integration, and reuse. By adopting the protocols, tools, and best practices outlined in this application note, materials researchers and drug development professionals can significantly enhance the value and impact of their data assets. The systematic application of FAIR principles not only addresses immediate challenges in data discovery and interoperability but also establishes a robust foundation for future innovations in AI-driven materials discovery and development. As the research community continues to refine FAIR implementation frameworks, the potential for accelerated discovery and translational application across materials science and drug development will continue to expand.

The acceleration of materials discovery and drug development is critically dependent on the effective integration of experimental and computational data workflows. Fragmented data systems and manual curation processes represent a significant bottleneck, stalling scientific innovation despite soaring research budgets [14]. This challenge is a central focus of current national initiatives, such as the recently launched Genesis Mission, which aims to leverage artificial intelligence (AI) to transform scientific research. This executive order frames the integration of federal datasets, supercomputing resources, and research infrastructure as a national priority "comparable in urgency and ambition to the Manhattan Project" [15]. Concurrently, the commercial adoption of materials informatics (MI)—the application of data-centric approaches to materials science R&D—is accelerating, with the market for external MI services projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.0% through 2035 [2]. This application note provides detailed protocols for building unified data infrastructure, enabling researchers to overcome fragmentation and harness AI for scientific discovery.

Quantitative Landscape of Data-Driven Research

The transition to integrated, data-driven workflows is not merely a technical improvement but a strategic necessity for maintaining competitiveness. The tables below summarize the market trajectory and core advantages of adopting materials informatics.

Table 1: Market Outlook for External Materials Informatics (2025-2035) [2]

| Metric | Value & Forecast | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Forecast Period | 2025 - 2035 | A decade of projected growth and adoption. |

| Market CAGR | 9.0% | Steady and significant expansion of the MI sector. |

| Projected Market Value | US$725 million by 2034 | Indicates a substantial and growing commercial field. |

Table 2: Strategic Advantages of Integrating Informatics into R&D [2]

| Advantage | Description | Impact on R&D Cycle |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Screening | Machine learning (ML) models can rapidly screen vast arrays of candidate materials or compounds based on existing data. | Drastically reduces the initial scoping and hypothesis generation phase. |

| Reduced Experiment Count | AI-driven design of experiments (DoE) pinpoints the most informative tests, minimizing redundant trials. | Shortens the development timeline and reduces resource consumption. |

| Discovery of Novel Relationships | ML algorithms can identify non-intuitive correlations and new materials or relationships hidden in complex, high-dimensional data. | Unlocks new scientific insights and innovation potential beyond human intuition. |

Protocol: Automated Extraction and Curation of Structured Data from Scientific Literature

A foundational step in building a materials database is the automated ingestion of structured information from existing, unstructured scientific literature. This protocol evaluates the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) for this task [16].

3.1. Experimental Principle This methodology assesses the capability of LLMs like GPT-3.5-Turbo, GPT-4, and GPT-4-Turbo to perform two critical information extraction (IE) tasks on materials science documents: Named Entity Recognition (NER) of materials and properties, and Relation Extraction (RE) between these entities. The performance is benchmarked against traditional BERT-based models and rule-based systems [16].

3.2. Research Reagent Solutions

- Source Corpora: SuperMat (focused on superconductor research) and MeasEval (a generic measurement evaluation corpus). These provide the unstructured text for analysis [16].

- Large Language Models (LLMs): GPT-3.5-Turbo, GPT-4, and GPT-4-Turbo. These are the primary tools for zero-shot and few-shot IE [16].

- Baseline Models: Specialized models based on the BERT architecture, fine-tuned on domain-specific data [16].

- Rule-Based Baseline: A system using hand-crafted rules for entity and relationship identification [16].

3.3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Task Definition and Prompt Engineering:

- For NER, the LLM is instructed to identify and classify spans of text into entity classes such as "Material" and "Property". A property is typically a structured measurement (e.g., "critical temperature of 4 K"), while a material may be a chemical formula or a descriptive name [16].

- For RE, the LLM is tasked with identifying and classifying the relationships between the extracted entities (e.g., linking a specific critical temperature value to a specific superconductor material) [16].

- Develop and iteratively refine clear, unambiguous prompts for these tasks.

- Zero-Shot and Few-Shot Evaluation:

- Execute the prompts against the test corpora without providing any examples (zero-shot).

- If performance is suboptimal, provide the model with one to three annotated examples within the prompt (few-shot) to demonstrate the desired output.

- Model Fine-Tuning (For RE Task):

- For relationship extraction, fine-tune a model like GPT-3.5-Turbo on a dataset of annotated examples. This specialized training significantly enhances performance for complex domain-specific reasoning [16].

- Performance Benchmarking:

- Run the same IE tasks using the baseline BERT-based and rule-based models.

- Compare the precision, recall, and F1 scores of all approaches against a manually annotated gold-standard dataset.

- Structured Data Output:

- The final output of a successful extraction run is a structured dataset (e.g., in JSON or CSV format) listing entities and their relationships, ready for ingestion into a materials database.

3.4. Workflow Visualization The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and decision points in the information extraction protocol.

Protocol: Implementing a Closed-Loop AI Experimentation Platform

The integration of automated data extraction with AI-driven prediction and experimental validation creates a powerful, autonomous research workflow. This protocol outlines the steps for establishing such a platform, aligning with the vision of the Genesis Mission's "American Science and Security Platform" [14] [15].

4.1. Experimental Principle This protocol establishes a closed-loop system where computational models guide robotic laboratories to conduct high-throughput experiments. The results from these experiments are then automatically fed back to improve the AI models, creating a continuous, self-optimizing cycle for materials or drug discovery [14] [15].

4.2. Research Reagent Solutions

- AI Modeling Framework: A software platform for training and deploying domain-specific foundation models and other ML algorithms for prediction [15].

- Robotic Laboratory Systems: Automated systems for high-throughput synthesis, processing, and characterization of materials or compounds [14] [2].

- Data Integration Hub: A centralized, secure database (e.g., built on the "American Science and Security Platform" concept) that ingests data from literature, simulations, and experiments, enforcing standardized data schemas [15].

- High-Performance Computing (HPC) Resources: Supercomputers for training large AI models and running complex simulations [14] [15].

4.3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Platform and Data Infrastructure Setup:

- Deploy and integrate the Data Integration Hub with HPC resources.

- Ingest initial datasets from published literature (using Protocol 3.1), internal historical data, and computational simulations (e.g., density functional theory calculations).

- Apply data standardization and curation processes to ensure quality and interoperability.

- Foundation Model Training and Hypothesis Generation:

- Train or fine-tune AI models on the integrated dataset to create predictive models for properties of interest (e.g., ionic conductivity, drug binding affinity).

- Use the trained models to screen vast virtual libraries of candidate materials or molecules.

- Generate a ranked list of the most promising candidates for experimental validation.

- Automated Experimental Validation:

- Translate the top candidate list into machine-readable instructions for robotic laboratory systems.

- Execute high-throughput synthesis and characterization protocols autonomously.

- Data Feedback and Model Retraining:

- Automatically stream the results from the robotic experiments back into the Data Integration Hub.

- Use this new, high-quality data to retrain and refine the AI models, improving their predictive accuracy for the next iteration.

- Iteration and Continuous Learning:

- Repeat the cycle of prediction, experimentation, and feedback until a target material or compound with the desired properties is identified and optimized.

4.4. Workflow Visualization The following diagram maps the integrated, closed-loop workflow, highlighting the synergy between computational and experimental components.

Table 3: Performance Evaluation of LLMs on Information Extraction Tasks [16]

| Task | Best Performing Model | Key Finding | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Named Entity Recognition (NER) | Traditional BERT-based & Rule-Based | LLMs with zero-shot/few-shot prompting failed to outperform specialized baselines. Challenges with complex, domain-specific material definitions. | Use specialized, fine-tuned BERT models or rule-based systems for high-accuracy entity extraction. |

| Relation Extraction (RE) | Fine-tuned GPT-3.5-Turbo | A fine-tuned GPT-3.5-Turbo outperformed all models, including baselines. GPT-4 showed strong few-shot reasoning. | For complex relationship mapping, fine-tuned LLMs are superior. GPT-4 is effective for few-shot prototyping. |

The integration of experimental and computational data workflows is a cornerstone of next-generation scientific discovery. As evidenced by national initiatives and market trends, the strategic implementation of protocols for automated data extraction and closed-loop AI experimentation is critical for accelerating R&D cycles. The data shows that while LLMs possess remarkable relational reasoning capabilities, a hybrid approach leveraging the strengths of both specialized and general-purpose models is currently optimal. By adopting these detailed protocols, research institutions can build the robust database infrastructure necessary to power AI-driven breakthroughs in materials science and drug development.

From Data to Discovery: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

In the field of materials science, the development of robust database infrastructure is critical for accelerating discovery. Automated data curation transforms raw, unstructured information from diverse sources into clean, reliable, and FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) datasets that power machine learning (ML) and data-driven research [17]. High-throughput (HT) experimental and computational workflows generate data at unprecedented scales, making manual curation methods impractical [18] [19]. This document outlines application notes and protocols for implementing automated data curation, drawing from best practices in high-throughput materials science.

The Automated Data Curation Workflow

Automated data curation is a continuous process that ensures long-term data quality and usability. The workflow can be broken down into several interconnected stages, as shown in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: Automated Data Curation Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key stages and their relationships in a robust, cyclical curation pipeline. The dashed line represents the essential feedback loop for continuous quality improvement.

Stage 1: Data Identification & Collection

This initial stage involves sourcing raw data from diverse origins and standardizing its initial format.

- Application Note: In high-throughput materials science, data streams are often generated directly by experimental instruments (e.g., combinatorial thin-film synthesis [18]) or computational workflows (e.g., AiiDA for ab-initio calculations [19]). The goal is to establish automated pipelines that collect this data with minimal manual intervention.

- Protocol:

- Connect to Data Sources: Use APIs or data capture pipelines to pull data from instruments, simulation outputs, or literature sources. For database construction from published literature, an AI-powered workflow can first retrieve relevant articles using LLM-based embeddings and clustering [20].

- Standardize Formats: Enforce consistent file types and resolutions early to prevent downstream pipeline failures. For image data, this may involve standardizing file formats; for tabular data, converting proprietary formats (e.g., .xlsx) to open formats (e.g., .csv) is recommended [21] [17].

Stage 2: Data Cleaning & Validation

This stage focuses on identifying and correcting errors and inconsistencies in the raw data.

- Application Note: Raw inputs often contain duplicates, corrupted files, or mislabeled data that can skew analysis and model training. In computer vision, this may involve detecting and removing near-duplicate images [21]. In computational materials science, automated workflows must check for convergence errors and numerical inaccuracies [19].

- Protocol:

- Profile Data: Perform statistical analysis to understand data distributions and identify anomalies, outliers, and missing values [22].

- Remove Duplicates: Use algorithms to detect and remove redundant or overly similar samples. Tools like LightlyOne can employ diversity selection strategies in an embedding space to ensure a representative and non-redundant dataset [21].

- Handle Errors & Missing Values: Implement rule-based or ML-based methods to correct mislabeled entries, impute missing data, or remove corrupted records.

Stage 3: Data Annotation & Enrichment

Here, raw data is labeled and augmented with additional context to make it usable for ML models.

- Application Note: For materials data, this can involve labeling experimental conditions, assigning property values extracted from text, or generating SMILES notations from chemical structure images using AI/ML models [20]. In vision-language models, curation ensures images are matched with precise, unbiased textual descriptions [21].

- Protocol:

- Automated Extraction: Use Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 to extract materials and their properties from scientific text with high accuracy [20].

- Image Mining: Employ AI/ML tools (e.g., Microsoft Azure's Document Intelligence and Custom Vision) to automatically generate SMILES from chemical structure images in publications [20].

- Establish Guidelines: Create clear, consistent labeling guidelines, even for automated processes, to ensure uniformity and quality.

Stage 4: Data Transformation & Integration

Data from multiple sources is converted into a consistent format and merged into a unified dataset.

- Application Note: A common challenge is harmonizing data from different sources, such as merging two object detection datasets with different labeling schemas or integrating experimental results with computational data [21] [18].

- Protocol:

- Normalize Data: Scale numerical values (e.g., pixel values, energy units) to a common range and unify annotation schemas [21].

- Merge Sources: Integrate multiple datasets by resolving schema conflicts and ensuring semantic consistency across merged data.

- Leverage Open Tools: Use open-source libraries to convert and validate annotation formats (e.g., COCO, YOLO) for interoperability [21].

Stage 5: Metadata Creation & Documentation

Context is added to the dataset to ensure it can be understood and reused.

- Application Note: Metadata is essential for reproducibility and reuse. For an image, this could be the capture device and conditions; for a computational dataset, it includes all input parameters and software versions [21] [19]. Standards like JSON or CVAT XML are often used [21].

- Protocol:

- Generate Metadata Automatically: Capture metadata at the point of data generation (e.g., from instrument logs, workflow provenance systems like AiiDA [19]).

- Create Documentation: Write README files and data dictionaries that explain acronyms, abbreviations, and the meaning of column fields in tabular data [17]. Document all quality control methods applied.

Stage 6: Storage, Publication & Sharing

The curated dataset is stored securely and made accessible to users.

- Application Note: The storage system must be efficient, scalable, and allow for quick retrieval, especially for large volumes of data like video or simulation outputs [21]. Publication should adhere to FAIR principles.

- Protocol:

- Choose Appropriate Storage: Use scalable cloud storage (AWS S3, Azure, GCS) or data warehouses that support large datasets [21].

- Define Access Rules: Implement role-based access controls and audit logging to ensure data security and compliance [22].

- Publish with Provenance: Use repositories that support persistent identifiers (DOIs) and record the data's origin and processing history [17].

Stage 7: Ongoing Maintenance & Monitoring

Data curation is a continuous process that requires regular updates and quality checks.

- Application Note: Models can suffer from "model drift" if the data is not updated to reflect new environments or conditions. Continuous integration of new data is crucial for maintaining model reliability [21].

- Protocol:

- Schedule Periodic Reviews: Regularly re-validate datasets, add new data, and re-annotate as necessary [21].

- Implement Version Control: Use versioning systems to track changes to the dataset over time, ensuring reproducibility and allowing for rollbacks if needed [22].

- Monitor Data Quality: Set up automated checks to monitor for quality degradation in incoming data streams.

Best Practices for AI-Ready Data Curation

For data to be effectively used in AI applications, especially for training machine learning models, specific quality standards must be met.

- Ensure Completeness and Non-Redundancy: Avoid publishing redundant files. All files should have a purpose, and large collections should be accompanied by scripts for subsetting and visualization [17].

- Document the AI/ML Pipeline: For datasets intended to train ML models, document the model used, its performance on the published dataset, and any related research papers in the metadata [17].

- Prioritize Open and Accessible Formats: Use non-proprietary, open data formats (e.g., CSV over Excel, LAS/LAZ for point cloud data) to ensure long-term usability and interoperability [17].

- Automate Rigorously, Oversight Humanely: Prioritize automation for routine tasks (e.g., data collection, basic cleaning) while preserving human oversight for complex decisions requiring domain expertise [22] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key tools and resources that form the backbone of a modern, automated data curation workflow in materials science.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Data Curation

| Tool / Resource Name | Type / Category | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| AiiDA [19] | Workflow Management Platform | Automates multi-step computational workflows (e.g., G0W0 calculations) and stores full data provenance to ensure reproducibility. |

| OpenAI GPT-4 / Embeddings [20] | Large Language Model (LLM) | Extracts structured materials property data from unstructured text in scientific literature and aids in document relevance filtering. |

| ChemDataExtractor [20] | Domain-Specific NLP Toolkit | Extracts chemical information from scientific text using named entity recognition (NER) and rule-based methods. |

| LightlyOne [21] | Data Curation Platform | Uses embeddings and selection strategies to automatically remove duplicates and select diverse, informative data samples for ML. |

| Airbyte [22] | Data Integration Platform | Collects and ingests data from a vast number of sources (600+ connectors) into a centralized system for curation. |

| VASP [19] | Ab-initio Simulation Software | Generates primary computational data (e.g., electron band structures) within high-throughput workflows. |

| Microsoft Azure Document Intelligence [20] | Computer Vision Service | Converts chemical structure images from publications into machine-readable SMILES notations. |

| DesignSafe Data Depot [17] | Data Repository & Tools | Provides a FAIR-compliant platform for publishing, preserving, and visualizing curated materials research data. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Automated Literature Mining for OPV Materials

This protocol details the AI-powered workflow for constructing an organic photovoltaic (OPV) materials database, as validated against a manually curated set of 503 papers [20].

Objective

To automatically construct a database of organic donor materials and their photovoltaic properties from published literature.

Equipment & Reagents

- Computational Environment: Standard computing environment or cloud services (e.g., Microsoft Azure).

- Software & APIs: Access to OpenAI's API (for GPT-4 and embeddings), Microsoft Azure's Document Intelligence and Custom Vision APIs.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Part A: Article Retrieval

- Initial Search: Perform a broad query of scientific publication databases (e.g., via Semantic Scholar, arXiv) using relevant keywords.

- Relevance Filtering: a. Generate text embeddings for each publication's abstract and/or full text using an LLM (e.g., OpenAI's text-embedding model). b. Cluster the embeddings to identify groups of semantically similar papers. c. Use direct LLM queries with structured prompts (e.g., "Does this paper report the performance of an organic photovoltaic device?") on clustered representatives or suspicious outliers to finalize the relevant article list.

Part B: Data Extraction via Text Mining

- Prompt Engineering: Design a precise prompt for the LLM (e.g., GPT-4 Turbo) to extract specific properties.

- Example Prompt Structure: "From the following text, extract the organic donor material's chemical structure, the acceptor material used, the power conversion efficiency (PCE), the open-circuit voltage (Voc), the short-circuit current (Jsc), and the fill factor (FF). Return the results in a structured JSON format."

- Batch Processing: Feed the full text of each relevant article into the LLM with the engineered prompt.

- Output Parsing: Collect the structured JSON outputs from the LLM and compile them into a master table.

Part C: Molecular Structure Extraction via Image Mining

- Identify Figures: Isolate figures and captions from the PDF of the publication.

- Classify Images: Use an image classification model (e.g., Azure Custom Vision) to identify figures that contain chemical structures.

- Extract SMILES: Process the chemical structure images through an image-to-SMILES tool (e.g., using Azure Document Intelligence) to generate machine-readable chemical representations.

Validation

- Compare the automatically extracted data against a pre-existing, manually curated benchmark dataset.

- Calculate accuracy metrics for each extracted property (e.g., PCE, Voc) to quantify performance against the manual standard [20].

The development of a robust materials database infrastructure hinges on the seamless flow of data from its point of origin to a findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) state in dedicated repositories. Electronic Laboratory Notebooks (ELNs) and data repositories are not isolated systems; they form a synergistic workflow that is foundational to modern scientific research, particularly in materials science and drug development. This workflow is crucial for complying with evolving funding agency policies, such as the NIH 2025 Data Management and Sharing Policy, which mandates a robust plan for managing and sharing scientific data [23].

An ELN serves as the digital cradle for research data, capturing experiments, protocols, observations, and results in a structured and secure environment. It facilitates good data management practices, provides data security, supports auditing, and allows for collaboration [24]. The repository, in turn, acts as the long-term, public-facing archive for this curated data, ensuring its preservation, discovery, and reuse by the broader scientific community. The synergy between them transforms raw experimental records into FAIR digital assets [25] [23], directly supporting the goals of materials database infrastructure development.

Protocol: Implementing the ELN-to-Repository Workflow

The following section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for establishing and executing a synergistic workflow between an ELN and a data repository.

Stage 1: Pre-Experiment Planning and ELN Setup

Objective: To configure the ELN and establish project structures before data generation.

ELN Selection and Configuration:

- Select an ELN that aligns with your disciplinary needs (e.g., Kadi4Mat or Chemotion for materials science, Benchling for life sciences) and offers integration capabilities with institutional or public repositories [25] [26] [27]. Considerations should include data security, collaborative features, and metadata management tools [24].

- Define user groups and permissions within the ELN. Ensure the Principal Investigator (PI) has access to all project and notebook entries [24].

- Develop and import standardized templates for repetitive experiments (e.g., "TEM investigation," "sample preparation," "chemical synthesis") to ensure consistent data capture. The use of such structured templates is exemplified in workflows at the Karlsruhe Nano Micro Facility (KNMFi) [25].

Project Organization:

- Establish a new project within the ELN for your research initiative.

- Adhere to lab- or project-defined naming conventions for notebook entries and data files to ensure clarity and searchability [24].

- Create an initial notebook entry detailing the experimental hypothesis, objectives, and funding source information (e.g., NIH grant number) [25].

Stage 2: In-Experiment Data Capture and Management

Objective: To comprehensively document the experimental process and link all relevant data in real-time.

Documentation:

- Use the pre-defined template to document the protocol, materials used (linking to the lab's inventory management system if available), and instrument parameters.

- Record all observations directly into the ELN. For hands-free operation in lab environments, utilize voice input or dedicated tablets [24].

- Embed or link to raw data files (e.g., microscopy images, spectra) directly from the instrument output into the ELN entry. Automated metadata extraction tools can streamline this process for instruments like SEMs and TEMs [25].

Metadata and Provenance:

- Complete all relevant metadata fields within the ELN template, such as authorship, timestamps, and sample history. This structured metadata is critical for making data FAIR at the repository stage [23].

- The ELN will automatically maintain an audit trail and version history, providing a tamper-proof record of all changes and establishing data provenance [23].

Stage 3: Post-Experiment Curation and Repository Submission

Objective: To prepare and transfer curated data and metadata from the ELN to a suitable repository.

Data Curation and Analysis:

- Finalize the notebook entry with results, data analysis, and conclusions. Link to processed data files and visualizations.

- Use tags or keywords within the ELN to improve the searchability of the entry across the entire notebook [24].

Repository Preparation and Submission:

- Data Management and Sharing Plan (DMSP) Compliance: Review the DMSP required by your funding agency (e.g., NIH). The ELN's structured data capture will directly support the commitments outlined in this plan [23].

- Export and Archive: Use the ELN's export functionality to create a complete, archivable record of the experiment. Ensure the ELN allows export in open, non-proprietary formats (e.g., XML, CSV, PNG) to avoid vendor lock-in and ensure long-term accessibility [26].

- Submit to Repository: Transfer the finalized dataset, along with its rich metadata, to an institutional or public repository. Many modern ELNs can integrate with or provide streamlined workflows for submission to repositories like Dataverse or discipline-specific hubs like Chemotion Repository [23] [28]. For interdisciplinary work, solutions like ELNdataBridge can facilitate data exchange between different ELN systems prior to repository submission [28].

Figure 1: A high-level workflow diagram illustrating the synergistic data lifecycle between an Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) and a data repository.

Application Note: A Materials Science Use Case

Title: Implementing a FAIR Data Workflow for a Multi-Technique Materials Characterization Study.

Background: A research group is investigating the microstructure of a novel high-entropy alloy using multiple techniques at a user facility. The goal is to create a comprehensive and linked dataset for publication and inclusion in a materials database.

Methods:

- ELN Setup: The group uses Kadi4Mat as their ELN, leveraging its materials science focus [25]. They utilize a set of "atomistic" templates developed for 'sample preparation general,' 'Focused Ion Beam and Scanning Electron Microscopy,' and 'Transmission Electron Microscopy' [25].

- Sample Tracking: A central record is created in Kadi4Mat for the alloy sample, assigning it a unique identifier.

- Process Documentation: For each step (e.g., FIB milling for TEM sample preparation, TEM investigation), a new record is created in the ELN using the corresponding template. Relevant metadata, including instrument parameters (from automated extraction where possible) and user observations, is recorded [25].

- Data Linking: All records—sample, preparation, experiments—are interlinked within the ELN, creating a knowledge graph that visually represents the process chain and relationships between the data [25].

- Repository Submission: Upon conclusion of the experiment, the interlinked set of records, along with all raw and processed data, is packaged and submitted from Kadi4Mat to a designated materials data repository, ensuring compliance with the FAIR principles.

Results and Discussion: This workflow ensured that all data generated from different instruments and by different researchers was consistently documented and intrinsically linked. The resulting dataset in the repository is not just a collection of files, but a structured, contextualized resource with rich metadata. This makes the data findable, understandable, and reusable for other researchers, thereby accelerating materials discovery and supporting the development of a comprehensive materials database infrastructure.

Table 1: Comparison of Selected ELN Platforms Relevant to Materials Science and Life Sciences

| ELN Platform | Primary Discipline Focus | Key Features | Interoperability & Repository Integration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kadi4Mat [25] | Materials Science | Template-driven records, process chain documentation, knowledge graph generation. | Open-source; part of a broader materials data infrastructure; API-based integration potential. | |

| Chemotion [28] | Chemistry / Materials Science | Chemical structure drawing, inventory management, repository connection. | Open-source; includes a dedicated repository (Chemotion Repository); supports data exchange via ELNdataBridge [28]. | |

| Herbie [28] | Materials Science | Ontology-driven webforms, semantic annotation, REST API. | Open-source; designed for interoperability; successfully integrated with Chemotion via API [28]. | |

| L7 | ESP [27] | Life Sciences | Unified platform with ELN, LIMS, and inventory; workflow orchestration. | Proprietary, integrated platform; emphasizes data contextualization within an enterprise ecosystem. |

| Benchling [27] | Biotechnology / Life Sciences | Molecular biology tools, real-time collaboration. | Proprietary; potential for data lock-in; integration capabilities may require significant configuration. |

Table 2: Common Data Repository Options and Their Alignment with the ELN Workflow

| Repository Type | Examples | Key Characteristics | Relevance to ELN Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional | Harvard Dataverse, University Repositories | Managed by a research institution; often general-purpose. | ELNs may have pre-built or configurable connections for streamlined data submission [24] [23]. |

| Discipline-Specific | Chemotion Repository [28], Protein Data Bank | Curated for a specific research domain; supports standardized metadata. | Highly synergistic; domain-specific ELNs (e.g., Chemotion) may offer direct submission pathways [28]. |

| General-Purpose / Public | Zenodo, Figshare | Broad scope; often assign Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs). | ELN data can be exported and packaged for submission, fulfilling DMSP requirements for public data sharing [23]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Data Workflows

This toolkit outlines key "reagents" – the software and standards – essential for constructing a robust ELN-to-Repository workflow.

Table 3: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for the Digital Workflow

| Item | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Structured Templates (ELN) | Pre-defined forms within the ELN that standardize data entry, ensuring consistency and capturing essential metadata from the outset [25]. |

| API (Application Programming Interface) | Allows different software (e.g., an ELN and a repository) to communicate directly, enabling automation of data transfer and synchronization [28]. |

| Persistent Identifier (PID) | A long-lasting reference to a digital object, such as a DOI (Digital Object Identifier). Assigned by repositories to datasets, it ensures the data remains findable even if its web location changes. |

| RO-Crate | A community-standardized framework for packaging research data with their metadata. It is emerging as a potential standard for data exchange between ELNs and repositories [26] [28]. |

| ELNdataBridge | A server-based solution acting as an interoperability hub, facilitating data exchange between different, disparate ELN platforms (e.g., between Chemotion and Herbie) [28]. |

Figure 2: System architecture for ELN-Repository interoperability, including the role of bridging solutions like ELNdataBridge.

Implementing Analysis and Visualization Tools for Reproducible Research