Beyond Traditional QSPR: How Foundation Models Are Reshaping Predictive Chemistry in Drug Discovery

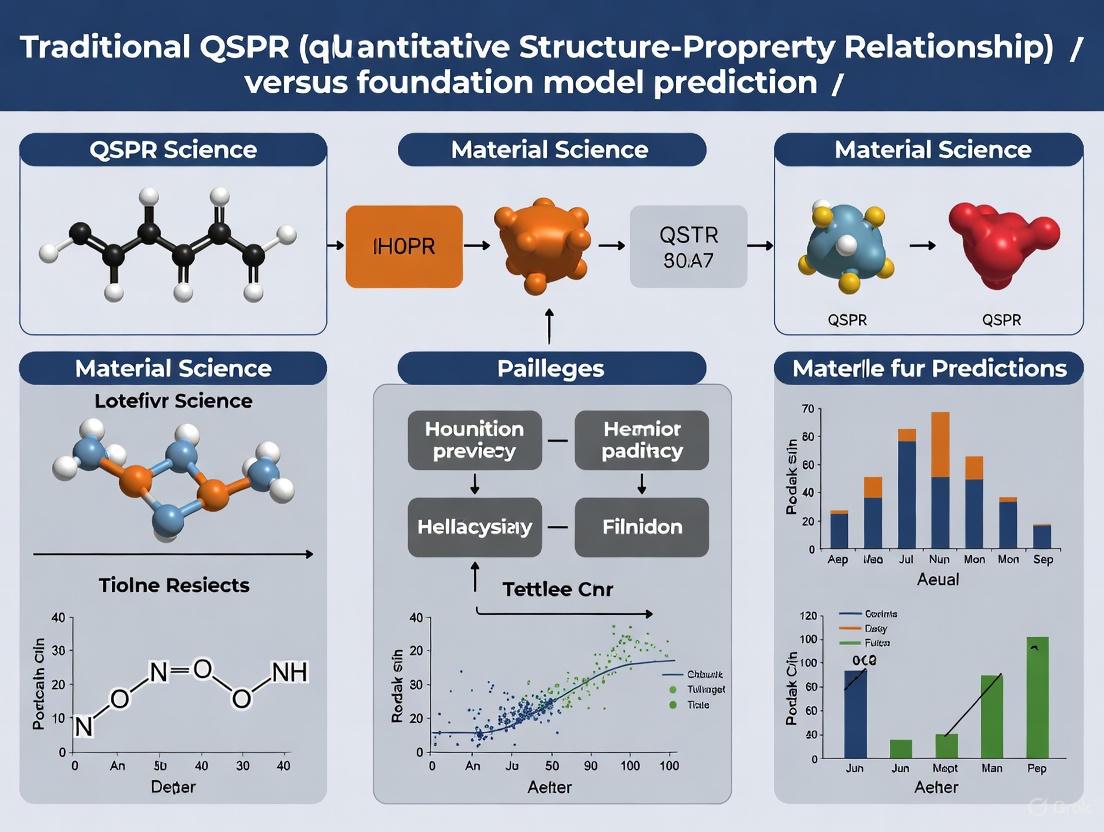

This article explores the evolving paradigm of property prediction in drug discovery, contrasting established Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) methodologies with emerging foundation model approaches.

Beyond Traditional QSPR: How Foundation Models Are Reshaping Predictive Chemistry in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the evolving paradigm of property prediction in drug discovery, contrasting established Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) methodologies with emerging foundation model approaches. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we dissect the foundational principles of descriptor-based QSPR, which relies on predefined molecular descriptors and topological indices to build predictive models. The discussion then progresses to the methodological shift brought by foundation models and advanced machine learning, capable of learning complex representations directly from data. We address critical challenges in both frameworks, including data quality, model interpretability, and overfitting, while providing optimization strategies. Finally, a comparative validation examines the performance, generalizability, and practical applications of both paradigms, concluding with a synthesis of their synergistic potential to accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

The Bedrock of Prediction: Understanding Traditional QSPR and the Rise of Foundation Models

Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling represents a foundational methodology in computational chemistry and drug discovery that establishes mathematical relationships between the chemical structures of compounds and their physicochemical properties or biological activities. The core hypothesis underpinning QSPR is that a compound's molecular structure fundamentally determines its properties and activities—a premise supported by chemical practice where structurally similar compounds often exhibit similar characteristics [1]. For decades, traditional QSPR approaches have served as indispensable tools for predicting molecular properties, optimizing chemical entities, and guiding experimental work, forming a crucial bridge between theoretical chemistry and practical applications in pharmaceutical research, environmental science, and materials development. While contemporary artificial intelligence and foundation models have recently emerged as transformative innovations in pharmaceutical R&D [2], traditional QSPR remains a rigorously validated framework with clearly interpretable mechanistic foundations. This guide examines the core principles, components, and applications of traditional QSPR modeling, providing researchers with a comprehensive understanding of its methodology, performance characteristics, and continuing relevance in the era of modern AI-driven approaches.

Core Components of Traditional QSPR Modeling

Molecular Descriptors: The Fundamental Building Blocks

Molecular descriptors serve as the fundamental quantitative representations of chemical structures in QSPR modeling, translating molecular features into numerical values that can be processed mathematically. These descriptors mathematically encode various aspects of molecular structure and properties, creating a structured numerical profile for each compound [1]. The accuracy and relevance of descriptors directly determine the predictive power and stability of QSPR models [1].

Table 1: Categories and Examples of Molecular Descriptors in Traditional QSPR

| Descriptor Category | Description | Specific Examples | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Describe molecular composition without geometry | Molecular weight, atom counts, bond counts | Basic characterization, drug-likeness filters |

| Topological | Encode molecular connectivity patterns | Molecular connectivity indices, Wiener index | Size and shape characterization for activity prediction |

| Geometrical | Capture 3D spatial characteristics | Molecular volume, surface area, inertia moments | Steric effects in binding interactions |

| Electronic | Quantify electronic distribution | Partial charges, dipole moment, HOMO/LUMO energies | Modeling charge-transfer interactions |

| Physicochemical | Represent bulk property relationships | LogP (lipophilicity), molar refractivity, polarizability | Solubility, permeability, ADMET prediction |

Effective descriptors must satisfy several critical criteria: they must comprehensively represent molecular properties, correlate meaningfully with the target activity, be computationally feasible to calculate, possess distinct chemical interpretability, and demonstrate sufficient sensitivity to capture subtle structural variations [1]. The development and refinement of molecular descriptors has evolved significantly from early easily interpretable physicochemical parameters to thousands of sophisticated descriptors enabled by advances in cheminformatics [1].

Mathematical Models: From Linear Regression to Machine Learning

The mathematical model serves as the functional core of any QSPR framework, providing the algorithmic bridge between molecular descriptors and the target property. The development of QSPR models represents a diverse and continuously evolving field where mathematical and statistical techniques identify empirical relationships between molecular descriptors and target properties [1]. These relationships may be linear or nonlinear, requiring different algorithmic approaches to capture effectively.

Traditional QSPR began with simple linear models, such as the Hansch analysis developed in the 1960s, which predicted biological activity using physicochemical parameters like lipophilicity, electronic properties, and steric effects [1]. These early approaches utilized limited, easily interpretable descriptors and simple linear models, establishing the foundational paradigm for quantitative structure-property modeling. As the field advanced, traditional QSPR incorporated more sophisticated statistical techniques including multiple linear regression (MLR), partial least squares (PLS) regression, and various feature selection methods to enhance prediction accuracy and generalization capability [1].

With increasing computational power and algorithmic sophistication, traditional QSPR progressively integrated machine learning methods that could capture nonlinear relationships without requiring explicit mathematical formulation of the underlying mechanisms. These include support vector machines (SVM), random forests (RF), artificial neural networks (ANN), and k-nearest neighbors (kNN) [3] [4]. The flexibility of these methods to learn complex functional relationships between descriptors and activity significantly expanded the applicability and predictive power of QSPR models [1].

Experimental Protocols and Workflow in Traditional QSPR

Standard QSPR Modeling Workflow

The development of robust QSPR models follows a systematic workflow encompassing data collection, preprocessing, descriptor calculation, model training, validation, and application. The following diagram illustrates this standardized protocol:

Data Collection and Preprocessing Methodology

The foundation of any reliable QSPR model is a high-quality, well-curated dataset. As highlighted in studies of antioxidant activity prediction, data collection typically begins with retrieving experimental values from specialized databases such as the Antioxidant Database (AODB), followed by rigorous filtering based on specific assay parameters and experimental conditions [4]. For PCB partitioning coefficient prediction, researchers compiled experimental polyethylene-water partition coefficients (KPE-w) for 115 polychlorinated biphenyls from multiple literature sources, ensuring consistency by standardizing experimental conditions [3].

Data preprocessing follows a standardized protocol:

- Standardization of Values: Experimental values are converted to consistent units (e.g., molar concentration for IC50 values) and often transformed to negative logarithmic forms (e.g., pIC50) to achieve more Gaussian-like distributions that improve modeling performance [4].

- Structural Curating: Molecular structures are standardized through neutralization of salts, removal of counterions and inorganic elements, elimination of stereochemistry, and canonization of structural representations like Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) [4].

- Duplicate Management: Duplicate compounds are identified using International Chemical Identifier (InChI) and canonical SMILES, with careful assessment of experimental value variance through calculation of coefficient of variation (CV), typically employing a cut-off of 0.1 to remove duplicates with high variability [4].

- Domain Definition: The applicability domain of the model is established to identify structural areas where predictions are reliable, often using approaches like the correlation weight descriptors computed from SMILES representations in Monte Carlo-based QSPR implementations [5].

Descriptor Calculation and Selection Protocols

Descriptor calculation employs specialized software tools that generate thousands of molecular descriptors encoding different chemical properties. The Mordred Python package has emerged as a widely used solution for calculating comprehensive molecular descriptors for QSAR studies [4]. For specific applications, customized descriptor approaches may be implemented, such as the CORAL software that leverages SMILES notations and the Monte Carlo algorithm to compute optimal correlation weight descriptors [5].

Descriptor selection follows stringent statistical protocols to identify the most relevant molecular features while avoiding overfitting. Techniques include:

- Feature Importance Ranking: Algorithms like random forest provide intrinsic feature importance scores that identify descriptors with strongest predictive power [3].

- Correlation Analysis: Highly intercorrelated descriptors are identified and redundant features eliminated to reduce dimensionality [1].

- Mechanistic Interpretation: Selected descriptors should possess chemical interpretability, allowing researchers to understand structural features influencing the target property, such as the identification that chlorine atomic number and ortho-substituted chlorines significantly affect polyethylene-water partition coefficients for PCBs [3].

Model Training and Validation Standards

The OECD QSAR validation principles mandate that reliable models must possess: (1) a defined endpoint, (2) an unambiguous algorithm, (3) a defined domain of applicability, (4) appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity, and (5) a mechanistic interpretation where possible [3].

Standard validation approaches include:

- Data Splitting: Datasets are typically divided into training (for model development), calibration (for parameter optimization), and validation (for predictive assessment) sets, often with multiple random splits to ensure robustness [5] [6].

- Statistical Metrics: Goodness-of-fit is assessed using R² (coefficient of determination), robustness via leave-one-out cross-validation Q², and external predictive performance through Q²ext [3]. Additional metrics include root-mean-square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) [4].

- Experimental Verification: Where possible, predictions are validated through experimental measurement, as demonstrated in PCB partitioning studies where modeling results agreed with experimental values within residuals of ±0.3 log unit [3].

Performance Comparison: Traditional QSPR vs. Modern Approaches

Predictive Performance Across Methodologies

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Traditional QSPR and Machine Learning Methods

| Methodology | R² Range | Application Example | Training Set Size | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | 0.24-0.93 [6] | Antioxidant activity prediction [4] | 303-6069 compounds [6] | High interpretability, simple implementation | Prone to overfitting with limited data [6] |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | 0.24-0.69 [6] | Cyclodextrin complex stability [7] | 303-6069 compounds [6] | Handles multicollinearity, works with many descriptors | Lower predictive accuracy with complex relationships [6] |

| Random Forest (RF) | 0.84-0.94 [6] | PCB partitioning coefficients [3] | 303-6069 compounds [6] | High accuracy, robust to outliers, feature importance | Limited interpretability, computational intensity |

| Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | 0.84-0.94 [6] | Triple-negative breast cancer inhibitors [6] | 303-6069 compounds [6] | Highest accuracy with large datasets, captures complex patterns | "Black box" nature, requires substantial data [8] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 0.919-0.975 [3] | Impact sensitivity of nitro compounds [5] | 404 compounds [5] | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, memory efficient | Parameter sensitivity, limited interpretability |

Comparative studies reveal that machine learning methods generally outperform traditional linear approaches, particularly as dataset complexity increases. In systematic comparisons using the same dataset and descriptors, machine learning methods (DNN and RF) exhibited predicted R² values near 90%, significantly surpassing traditional QSAR methods (PLS and MLR) at 65% with training sets of 6069 compounds [6]. This performance advantage becomes particularly pronounced with smaller training sets, where DNN and RF maintained R² values of 0.84-0.94 with only 303 training compounds, while PLS and MLR dropped to 0.24 from 0.69 [6].

Case Study: Antioxidant Activity Prediction

A comprehensive study developing QSAR models for predicting the antioxidant potential of 1911 chemical substances demonstrates the comparative performance of various algorithms within the traditional QSPR framework. Using the DPPH radical scavenging activity assay data from the AODB database, researchers evaluated multiple machine learning algorithms, finding that Extra Trees models achieved the highest performance (R² = 0.77), followed closely by Gradient Boosting (R² = 0.76) and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (R² = 0.75) [4]. An integrated ensemble method ultimately outperformed all individual models, achieving an R² of 0.78 on the external test set [4]. This case study illustrates how traditional QSPR frameworks successfully incorporate advanced machine learning techniques while maintaining the methodological rigor of validation and interpretation.

Case Study: Impact Sensitivity of Energetic Materials

Research predicting the impact sensitivity of 404 nitroenergetic compounds using the Monte Carlo algorithm implemented in CORAL-2023 software demonstrates the continuing evolution of traditional QSPR approaches [5]. This study developed models using SMILES representations and correlation weight descriptors, comparing four target functions with different statistical benchmarks. The model incorporating both the index of ideality of correlation (IIC) and correlation intensity index (CII) demonstrated superior predictive performance (R²Validation = 0.7821, Q²Validation = 0.7715) [5], illustrating how traditional QSPR methodologies continue to incorporate advanced statistical measures to enhance predictive accuracy while maintaining mechanistic interpretability through correlation weights that identify structural features associated with increased or decreased impact sensitivity.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Traditional QSPR Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL [9], AODB [4], ZINC [8] | Source of chemical structures and experimental bioactivity data | Annotated bioactivity data, standardized structures, quality metrics |

| Descriptor Software | Mordred [4], alvaDesc [3] | Calculate molecular descriptors from chemical structures | Comprehensive descriptor sets, standardization, batch processing |

| QSPR Modeling Platforms | CORAL [5], WEKA, scikit-learn | Implement machine learning algorithms for model development | Monte Carlo optimization, diverse algorithms, validation protocols |

| Validation Tools | Internal Q², external validation, applicability domain | Assess model robustness and predictive power | Statistical metrics, domain definition, reliability estimation |

Traditional QSPR modeling represents a mature, rigorously validated framework for establishing quantitative relationships between molecular structure and chemical properties. Its core components—well-curated datasets, informative molecular descriptors, and appropriate mathematical models—provide a systematic approach to property prediction that maintains strong mechanistic interpretability. While modern deep learning and foundation models demonstrate superior performance in certain applications with large datasets [2] [6], traditional QSPR methods continue to offer significant advantages in scenarios with limited data, requirements for mechanistic interpretation, and established chemical domains. The integration of machine learning algorithms within the traditional QSPR framework has substantially enhanced predictive accuracy while maintaining the methodological rigor that has characterized this field for decades. As computational chemistry advances, traditional QSPR principles provide a foundational understanding that continues to inform the development and interpretation of more complex AI-driven approaches in chemical and pharmaceutical research.

Molecular descriptors are the cornerstone of quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, providing numerical representations of chemical structures that enable the prediction of molecular behavior [10]. These descriptors transform structural information into mathematical values, creating bridges between chemical architecture and experimentally observable properties [11]. For decades, traditional QSPR approaches have relied on expert-crafted descriptors—topological, electronic, and physicochemical—to build predictive models. However, the emergence of foundation models represents a paradigm shift toward data-driven representation learning [12]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these approaches, examining their underlying methodologies, performance characteristics, and applicability to modern drug discovery challenges.

Molecular Descriptors: Categories and Computational Methods

Molecular descriptors are broadly categorized based on the structural features and mathematical approaches used in their calculation. The table below summarizes the primary descriptor classes and their characteristics.

Table 1: Categories of Molecular Descriptors in QSPR/QSAR Research

| Descriptor Category | Basis of Calculation | Representative Examples | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topological Descriptors | Molecular graph connectivity and branching | Wiener index, Zagreb indices, Randić connectivity index [13] [14] [15] | Predicting boiling points, molecular complexity, polar surface area [13] [14] |

| Electronic Descriptors | Electronic distribution and orbital properties | HOMO-LUMO gap, dipole moment, molecular orbital energies [16] | Modeling chemical reactivity, biological activity, intermolecular interactions |

| Physicochemical Descriptors | Bulk physical and chemical properties | logP (octanol-water partition coefficient), molecular weight, solubility parameters [11] | Predicting absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion (ADMET) properties [17] [15] |

| Geometrical Descriptors | 3D molecular shape and size | Molecular surface area, volume, inertia moments, 3D-Wiener index [14] | Analyzing receptor-ligand interactions, steric effects in biological activity |

| Foundation Model Embeddings | Learned representations from pre-training | MolE atomic embeddings, graph neural network representations [12] | Multi-task learning for diverse ADMET endpoints with limited labeled data |

Traditional Descriptor Computation

Traditional descriptor calculation begins with molecular structure representation, typically as a hydrogen-suppressed graph where atoms represent vertices and bonds represent edges [13] [10]. Topological indices are then computed through mathematical operations on these graph representations. For instance, the first Zagreb index (M₁) is calculated as the sum of squares of vertex degrees, while the second Zagreb index (M₂) represents the sum of products of vertex degrees of adjacent atoms [13]. The Hyper Zagreb index extends this concept by squaring the sum of vertex degrees for each edge [13].

Electronic descriptors require quantum chemical calculations, typically employing semi-empirical or density functional theory (DFT) methods to derive properties such as HOMO-LUMO energies, partial atomic charges, and electrostatic potentials [14] [16]. These computations are more resource-intensive than topological descriptor calculation but provide insights into reactivity and intermolecular interactions.

Experimental Protocols: Traditional QSPR vs. Foundation Models

Traditional QSPR Workflow

The traditional QSPR pipeline follows a well-established sequence of steps with rigorous validation requirements:

- Dataset Curation: A set of compounds with experimentally determined properties is assembled. The molecules are typically divided into training (∼70-80%) and external test sets (∼20-30%) [18].

- Descriptor Calculation: Molecular structures are converted into numerical descriptors using software such as DRAGON, PaDEL, or RDKit [16] [11] [18]. This typically generates thousands of potential descriptors.

- Descriptor Pre-selection: Redundant or uninformative descriptors are removed through filtering processes. This includes eliminating constant or near-constant descriptors and applying intercorrelation limits (typically r > 0.95-0.99) to reduce collinearity [18].

- Variable Selection: Feature selection algorithms such as genetic algorithms (GA), stepwise regression, or LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) identify the most relevant descriptor subsets [16] [18]. The genetic algorithm approach typically uses leave-one-out cross-validated R² (Q²LOO) as the objective function with populations of 100 compounds over 100 iterations [18].

- Model Building: Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) with Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) is commonly used to construct the final QSPR model [13] [18]. The model takes the form: Property = A + B × [Descriptor₁] + C × [Descriptor₂] + ...

- Model Validation: Internal validation (cross-validation, bootstrapping) and external validation (test set prediction) are performed. Models must satisfy criteria including Q²LOO > 0.6 and R²test > 0.6 [18]. The applicability domain is defined to identify compounds for which predictions are reliable [19].

Foundation Model Workflow

Foundation models employ a fundamentally different approach based on representation learning:

- Self-Supervised Pretraining: Models like MolE are first trained on large-scale unlabeled molecular datasets (e.g., 842 million compounds from ZINC20 and ExCAPE-DB) [12]. The pretraining task involves masked atom prediction, where 15% of atoms are randomly masked, and the model must predict their atom environments (all atoms within two bonds) based on contextual information [12].

- Supervised Pretraining: A second pretraining phase uses large labeled datasets (∼456,000 compounds) for multi-task learning across various biological endpoints [12].

- Task-Specific Finetuning: The pretrained model is adapted to specific property prediction tasks using smaller, labeled datasets. This involves minimal architectural changes and training on task-specific data [12].

- Inference and Interpretation: The finetuned model predicts properties for new compounds, with attention mechanisms potentially providing insights into important molecular substructures [12].

Diagram 1: Comparison of Traditional QSPR and Foundation Model Workflows

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data

Predictive Accuracy Across ADMET Tasks

Foundation models demonstrate superior performance on complex biological endpoints, particularly when labeled data is limited. The MolE model achieved state-of-the-art performance on 10 of 22 ADMET tasks in the Therapeutic Data Commons (TDC) benchmark, surpassing traditional descriptor-based approaches and specialized graph neural networks [12]. This advantage is most pronounced for endpoints with small datasets (e.g., drug-induced liver injury prediction with only 475 compounds) where traditional QSPR models struggle with generalization [12].

For predicting fundamental physicochemical properties, traditional topological indices remain highly competitive. Studies comparing diverse descriptor types found that classical topological indices such as the Wiener index and Randić connectivity index frequently appear in the best regression models for properties including boiling point, molar volume, and refractive index [14]. The table below summarizes comparative performance data.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Traditional vs. Foundation Model Approaches

| Model Category | Representation | Boiling Point Prediction (R²) | Complex ADMET Prediction | Data Efficiency | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Topological Indices | Molecular graphs | 0.84-0.92 [13] [14] | Limited | Requires ~50+ labeled compounds [18] | High (explicit descriptors) |

| Electronic Descriptors | Quantum chemical properties | 0.79-0.88 [14] | Moderate | Requires ~50+ labeled compounds | Moderate |

| Foundation Models (MolE) | Learned embeddings | Not specifically reported | State-of-the-art on 10/22 TDC tasks [12] | Effective with <500 labeled compounds [12] | Lower (black-box) |

Virtual Screening Performance

The appropriate evaluation metrics differ significantly between traditional QSPR and foundation models, particularly for virtual screening applications. While traditional approaches prioritize balanced accuracy, foundation models optimized for positive predictive value (PPV) demonstrate substantially improved hit rates in virtual screening [19]. Models trained on imbalanced datasets with PPV optimization identified 30% more true positives in the top scoring compounds compared to balanced models, highlighting the practical advantage of this approach for early drug discovery where only limited compounds can be experimentally tested [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Descriptor Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DRAGON | Software | Calculates >4000 molecular descriptors | Traditional QSPR descriptor generation [18] |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit | Molecular descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation | Traditional and modern QSPR, descriptor computation [16] [12] |

| QSARINS | Software | MLR model building with genetic algorithm variable selection | Traditional QSPR model development with validation [18] |

| MolE | Foundation model | Self-supervised molecular representation learning | Transfer learning for ADMET prediction with limited data [12] |

| Therapeutic Data Commons (TDC) | Benchmark platform | Standardized ADMET prediction datasets | Model comparison and validation [12] |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Software | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints | Traditional QSPR descriptor generation [16] |

The evolution of molecular descriptors from expert-defined topological indices to learned representations in foundation models represents a fundamental shift in QSPR methodology. Traditional descriptors maintain their value for predicting straightforward physicochemical properties and offer high interpretability, while foundation models excel at complex biological endpoint prediction, particularly with limited labeled data. The future of molecular property prediction lies not in choosing one approach exclusively, but in strategically applying each methodology according to the specific research context—leveraging traditional descriptors for their interpretability and physical grounding while harnessing foundation models for their predictive power and data efficiency in biologically complex domains. This integrated approach will accelerate drug discovery and materials design by providing researchers with a comprehensive, multi-faceted toolkit for molecular property prediction.

The field of computational chemistry is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from traditional Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) models to AI foundation models for chemical representation. This shift represents a fundamental change in how molecules are represented and how chemical properties are predicted. Traditional QSPR approaches have long relied on hand-crafted molecular descriptors and statistical modeling to establish relationships between molecular structure and properties. While these methods have provided valuable insights, they often struggle with limited generalizability and manual feature engineering requirements [20].

The emergence of foundation models—large-scale neural networks pre-trained on extensive chemical datasets—heralds a new paradigm. These models leverage self-supervised learning to develop generalized molecular representations that can be adapted to diverse downstream tasks with minimal fine-tuning [20] [21]. This transition from specialized, task-specific models to generalized, adaptable representations mirrors similar revolutions in natural language processing and computer vision, offering unprecedented opportunities for accelerating materials discovery and drug development [22] [23].

The Traditional QSPR Paradigm: Foundations and Limitations

Core Principles and Methodologies

Traditional QSPR modeling establishes mathematical relationships between molecular descriptors and target properties using statistical methods. The approach relies on numerical descriptors that encode various chemical, structural, or physicochemical properties of compounds [16]. These descriptors are typically categorized by dimensions:

- 1D descriptors: Molecular weight, atom counts, and other global properties

- 2D descriptors: Topological indices, connectivity fingerprints, and structural patterns

- 3D descriptors: Molecular surface area, volume, and conformer-based properties [16]

Classical QSPR employs statistical techniques including Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS), and Principal Component Regression (PCR) [16]. These methods are valued for their interpretability and computational efficiency, particularly when dealing with congeneric series of compounds with linear structure-property relationships.

Experimental Protocols in Traditional QSPR

The standard workflow for developing traditional QSPR models involves several well-established steps:

Data Collection and Curation: Experimental property data is gathered from databases like DIPPR, containing 1,701+ molecules across diverse chemical families with measured critical temperatures, pressures, acentric factors, and normal boiling points [24].

Descriptor Calculation: Software tools including AlvaDesc, Dragon, RDKit, and Mordred generate 247+ molecular descriptors capturing structural, electronic, and topological features [24]. The Mordred calculator, for instance, can generate over 1,600 descriptors for comprehensive molecular characterization [24].

Feature Selection: Dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), and LASSO identify the most relevant descriptors and mitigate overfitting [16].

Model Training and Validation: Statistical models are built using the selected descriptors, with rigorous validation through metrics including R² (coefficient of determination) and Q² (cross-validated R²) to ensure robustness and predictive capability [16].

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Traditional QSPR Modeling

| Tool Name | Descriptor Types | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlvaDesc [24] [16] | 1D-3D, Quantum Chemical | 5,000+ descriptors, extensive profiling | Drug discovery, toxicology |

| Dragon [24] [16] | 1D-3D, Structural | 5,000+ descriptors, similarity metrics | Pharmaceutical research, materials science |

| RDKit [24] [16] | 2D-3D, Fingerprints | Open-source, cheminformatics platform | Virtual screening, QSAR modeling |

| Mordred [24] | 1D-3D, Topological | 1,600+ descriptors, Python integration | High-throughput screening, property prediction |

Limitations of Traditional Approaches

Despite their widespread adoption, traditional QSPR methods face several critical limitations:

- Manual Feature Engineering: Dependence on expert-crafted descriptors introduces human bias and may overlook subtle but important structural patterns [20] [21].

- Limited Generalizability: Models trained on specific chemical domains often perform poorly when applied to structurally distinct compounds, such as beyond Rule of Five (bRo5) molecules like targeted protein degraders [25].

- Data Scarcity Challenges: Traditional methods require substantial labeled data for each new property, creating bottlenecks in model development [26].

- Inability to Capture Complex Nonlinearities: Simple statistical models struggle with intricate structure-property relationships that require deep hierarchical feature learning [21].

AI Foundation Models: A New Paradigm for Chemical Representation

Theoretical Foundations and Architecture

AI foundation models for chemistry represent a fundamental shift from task-specific modeling to generalized representation learning. These models are defined as "a model that is trained on broad data (generally using self-supervision at scale) that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks" [20]. The core innovation lies in separating representation learning from downstream prediction tasks, enabling the model to develop a fundamental understanding of chemical structure that transfers across diverse applications [20].

Foundation models typically employ transformer architectures that process molecular representations—most commonly SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line-Entry System) strings or molecular graphs—using self-attention mechanisms to capture complex relationships between atomic constituents [27] [23]. Unlike traditional QSPR's fixed descriptors, foundation models generate context-aware embeddings that adaptively represent molecules based on their structural context and the specific prediction task.

Experimental Protocols for Foundation Model Development

The development of chemical foundation models follows a sophisticated multi-stage process:

Large-Scale Pre-training: Models are trained on massive unlabeled molecular datasets (e.g., 2-6 billion molecules from Enamine REALSpace) using self-supervised objectives like Masked Language Modeling (MLM) [23]. For example, the MIST foundation model family employs the Smirk tokenization algorithm, which comprehensively captures nuclear, electronic, and geometric features during pre-training [23].

Tokenization and Representation: Advanced tokenizers process SMILES strings or molecular graphs into discrete tokens that preserve critical chemical information. The Smirk tokenizer developed for MIST models specifically captures stereochemistry, isotopic information, and electronic properties often missed by traditional representations [23].

Transfer Learning and Fine-tuning: Pre-trained models are adapted to specific property prediction tasks using smaller labeled datasets (often containing only hundreds to thousands of examples) [20] [23]. This process typically involves adding task-specific heads and fine-tuning with reduced learning rates.

Multi-task and Multi-modal Learning: Advanced foundation models simultaneously learn multiple properties across different data modalities (text, structure, spectral data), enabling knowledge transfer between related tasks [21] [25].

Diagram 1: Foundation Model Development Workflow

Comparative Performance Analysis: Traditional QSPR vs. Foundation Models

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Chemical Domains

| Model Category | Architecture | Test Domain | Key Performance Metrics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional QSPR (Ensemble ANN) [24] | Mordred descriptors + Bagging | Critical properties (TC, PC, ACEN, NBP) | R² > 0.99 for 1,701 molecules | Limited to descriptor coverage, poor transfer across domains |

| Foundation Model (MIST-1.8B) [23] | Transformer, Smirk tokenization | 400+ property prediction tasks | SOTA across physiology, electrochemistry, quantum chemistry | High computational cost, complex training requirements |

| Global MT Model [25] | MPNN + DNN ensemble | TPD permeability, clearance, CYP inhibition | MAE: 0.33 (LogD), Misclassification: 0.8-8.1% | Requires transfer learning for specialized modalities |

| Graph Neural Network [21] | 3D-aware GNN, pre-training | Molecular property benchmarks | Superior to fingerprints on complex conformational properties | Limited 3D training data, computational intensity |

Application-Specific Performance

Foundation models demonstrate particular advantages in challenging chemical domains:

Targeted Protein Degraders (TPD): For complex modalities like molecular glues and heterobifunctional degraders, foundation models achieve misclassification errors of 0.8-8.1% for critical ADME properties, outperforming traditional models on these structurally novel compounds [25].

Multi-objective Optimization: Models like MIST enable simultaneous optimization of multiple properties across diverse chemical spaces, including electrolyte solvent screening and olfactory perception mapping [23].

Low-Data Regimes: Foundation models fine-tuned with limited labeled data (often <100 examples) frequently match or exceed the performance of traditional models trained on much larger datasets [20] [23].

Table 3: Performance on Challenging Molecular Classes

| Molecular Class | Traditional QSPR Performance | Foundation Model Performance | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beyond Rule of 5 (bRo5) Compounds [25] | Poor generalization, high error rates | MAE: 0.39 (heterobifunctionals) | Transfer learning, structural awareness |

| Organometallics & Isotopes [23] | Limited descriptor coverage | Accurate prediction of isotopic properties | Comprehensive tokenization (Smirk) |

| Energetic Molecules [26] | Moderate accuracy for safety properties | Potential for high-precision prediction | Multi-task learning, inverse design capability |

| Polymer Systems [21] | Treat as ensembles, approximate properties | Graph representations for precise feature capture | Specialized frameworks for macromolecules |

Table 4: Essential Resources for Chemical Foundation Model Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Key Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-training Datasets | Enamine REALSpace [23], PubChem [20], ZINC [20] | Large-scale molecular data for self-supervised learning | Commercial, Public |

| Descriptor Calculators | Mordred [24], RDKit [24] [16], Dragon [16] | Molecular descriptor generation for traditional QSPR | Open-source, Commercial |

| Foundation Models | MIST [23], ChemLLM [22], MatSciBERT [22] | Pre-trained models for transfer learning | Open-source, Commercial |

| Benchmark Suites | MoleculeNet [21], TPD ADME [25] | Standardized evaluation across chemical domains | Public |

| Specialized Tokenizers | Smirk [23], SELFIES [20] | Advanced molecular representation for transformers | Open-source |

| Interpretability Tools | SHAP [16], LIME [28] [16] | Explainable AI for model predictions | Open-source |

The transition from traditional QSPR to AI foundation models represents a paradigm shift in chemical representation and property prediction. While traditional methods continue to offer value for well-defined chemical spaces with abundant labeled data, foundation models provide unprecedented capabilities for generalization across diverse chemical domains, low-data learning, and multi-property optimization.

The future of chemical representation will likely involve hybrid approaches that integrate the interpretability of traditional descriptors with the representational power of foundation models. Emerging techniques in explainable AI (XAI) [28] [16], geometric learning [21], and multi-modal fusion [21] will further enhance our ability to navigate chemical space efficiently. As these models continue to evolve, they promise to accelerate the discovery of novel materials, therapeutics, and sustainable chemical solutions to pressing global challenges.

The journey of a drug molecule from administration to its site of action is governed by a critical sequence of properties, primarily beginning with its solubility and culminating in its bioavailability. Solubility, the ability of a drug to dissolve in a solvent, and bioavailability, the fraction of the administered dose that reaches systemic circulation unchanged, are foundational to a drug's efficacy [29]. It is estimated that between 70% and 90% of new chemical entities (NCEs) in the drug development pipeline are poorly soluble, which directly leads to bioavailability issues and constitutes a major challenge in pharmaceutical development [29]. For decades, the primary approach for predicting these properties relied on Traditional Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) models, which establish mathematical relationships between a molecule's descriptors and its properties [1]. Today, the field is increasingly shifting towards Foundation Models and Advanced AI, which leverage complex architectures like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and ensemble methods to learn directly from molecular structures and large, diverse datasets [30]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two paradigms, examining their methodologies, performance, and practical applications in predicting the key properties that define a drug's scope.

Core Concepts: Solubility and Bioavailability

Defining the Key Properties

- Solubility: This is the ability of a drug to dissolve in a solvent, typically water or physiological fluids, to form a homogenous solution. It is a critical factor influencing absorption, distribution, and bioavailability [29]. Accurate prediction requires distinguishing between different types of solubility, such as:

- Thermodynamic Solubility: The maximum concentration of a compound in solution at equilibrium with its most stable crystalline form, often measured during lead optimization [31].

- Intrinsic Solubility (S0): The aqueous solubility of the uncharged form of a molecule [32].

- Apparent Solubility: The solubility measured in a fixed-pH buffer solution [31].

- Bioavailability: This refers to the fraction of an administered drug that reaches the body's circulatory system unchanged and is therefore able to produce a therapeutic effect. It is directly influenced by a drug's solubility, its stability in the digestive system, and its ability to cross biological barriers [29]. Oral bioavailability (F) is a product of the fraction absorbed (Fa), the fraction escaping gut metabolism (Fg), and the fraction escaping hepatic metabolism (Fh) [33].

The Critical Path from Solubility to Systemic Exposure

The following pathway visualizes the journey of an orally administered drug and the key properties that determine its successful absorption.

Traditional QSPR Workflow and Data Challenges

The QSPR Modeling Process

Traditional QSPR modeling is a structured, multi-step process that relies heavily on expert-curated molecular descriptors. The following diagram outlines the standard workflow for developing a reliable QSPR model, from data collection to deployment.

Experimental Protocols and Data Curation in QSPR

The reliability of any QSPR model is contingent on the quality of the experimental data used for its training. For solubility, the gold standard is the measurement of thermodynamic solubility.

- Shake-Flask Method: The OECD 105 Guideline recommends this method for chemicals with solubility above 10 mg/L. It involves mixing a solute in water until thermodynamic equilibrium is reached between the solid and solvated phases. The phases are then separated by centrifugation or filtration, and the concentration in the filtrate is quantified [31].

- CheqSol Technique: An advanced method for ionizable compounds, CheqSol is an automated titration that adjusts the pH until the solute precipitates or dissolves. The concentration of uncharged species is deduced from the equilibrium point and the compound's pKa [31].

A significant challenge in building general QSPR models is data quality and consistency. Key issues include:

- Systematic Noise: The presence of amorphous solid forms post-measurement can introduce a biased positive error that cannot be overcome by simply adding more data [32].

- Variability in Conditions: Public datasets often mix intrinsic, apparent, and water solubility data without consistent reporting of pH, temperature, or solid-state nature [31].

- Impact of Quality: Studies show that with the same dataset size, high-quality data leads to better model performance. However, models trained on larger datasets with some analytical variability can sometimes match the accuracy of models trained on smaller, cleaner datasets, unless the noise is systematic [32].

Foundation and Advanced AI Models

Modern AI Approaches in Property Prediction

Foundation models in drug discovery shift the paradigm from descriptor-based learning to end-to-end pattern recognition directly from molecular structure.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): These models represent molecules as graphs, with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. GNNs excel at capturing complex molecular interactions and learning features directly from the graph structure, which can be highly informative for predicting properties like solubility and bioavailability [30].

- Ensemble Learning: Methods like Stacking Ensembles combine the predictions of multiple base models (e.g., GNNs, Transformers, Random Forest) to improve overall accuracy and robustness. One study on pharmacokinetic parameters reported that a Stacking Ensemble achieved an R² of 0.92, outperforming individual models [30].

- Advanced Regression Models: In solubility modeling, techniques such as Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), which provides uncertainty estimates, and Multilayer Perceptrons (MLP) are widely used. These are often optimized with algorithms like Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) for hyperparameter tuning to enhance predictive performance [34].

Performance Comparison: Traditional QSPR vs. Advanced AI

The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from various studies, highlighting the evolution of predictive accuracy for solubility and bioavailability-related properties.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Predictive Models for Drug Properties

| Model Type | Specific Model | Predicted Property | Performance Metrics | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional QSPR | Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | NF-κB Inhibitor Activity | Statistical metrics from internal validation | [35] |

| Traditional QSPR | Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | NF-κB Inhibitor Activity | Statistical metrics from internal validation; outperformed MLR | [35] |

| Modern ML | Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | Drug Solubility in SC-CO₂ | R² = 0.99343, MSE = 3.0869E-02 | [36] |

| Modern ML | LASSO Regression | Drug Solubility in SC-CO₂ | R² = 0.90955 | [36] |

| Modern ML | Bayesian Ridge Regression | Drug Solubility in SC-CO₂ | R² = 0.8891 | [36] |

| Foundation AI | Stacking Ensemble | Pharmacokinetics (ADME) | R² = 0.92, MAE = 0.062 | [30] |

| Foundation AI | Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Pharmacokinetics (ADME) | R² = 0.90 | [30] |

| Foundation AI | Transformer | Pharmacokinetics (ADME) | R² = 0.89 | [30] |

| Optimized ML | Ensemble Voting (MLP+GPR) | Clobetasol Propionate Solubility | Superior accuracy vs. individual MLP/GPR models | [34] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

This section details essential materials and computational tools used in experimental and in silico research for assessing solubility and bioavailability.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Solubility and Bioavailability Studies

| Tool / Solution | Function / Application | Relevance to Prediction Models |

|---|---|---|

| PhysioMimix Bioavailability Assay | An in vitro microphysiological system (Gut/Liver-on-a-chip) that recreates intestinal permeability and first-pass metabolism to estimate human oral bioavailability [33]. | Generates high-quality human-relevant data for validating and refining in silico PBPK and AI models. |

| Primary Human RepliGut Cells | Used in co-culture with liver models in the Gut/Liver-on-a-chip system to provide a more physiologically relevant barrier for absorption studies [33]. | Improves the quality of input data for model training, potentially enhancing predictive accuracy for human bioavailability. |

| Chasing Solubility (CheqSol) Assay | An automated titration method for measuring intrinsic and kinetic solubility of ionizable compounds by tracking the pH of equilibrium [31]. | Produces high-quality, thermodynamic solubility data crucial for building reliable QSPR and ML models. |

| Polarized Light Microscopy | Used to characterize the solid-state form (crystalline or amorphous) of a compound post-solubility measurement [32]. | Critical for data curation; identifying amorphous solids helps remove systematic noise from training datasets. |

| RDKit / Mordred | Open-source cheminformatics toolkits for calculating 2D and 3D molecular descriptors from chemical structures [32]. | The primary source of features for traditional QSPR models and as input for some machine learning models. |

| ADMET Predictor | Commercial software for predicting pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties, including log D, which can help identify intrinsic solubility from pH-dependent data [32]. | Used in data processing workflows to curate and label experimental data for model training. |

The evolution from Traditional QSPR to Foundation AI Models represents a significant leap in our ability to accurately predict critical drug properties like solubility and bioavailability. Traditional QSPR models, built on expert-curated molecular descriptors, offer interpretability and remain valuable for well-defined chemical series with high-quality, congeneric data. However, their performance is often limited by the quality and breadth of the training data and the fundamental challenge of descriptor selection [1] [31]. In contrast, Foundation Models and Advanced AI, such as GNNs and ensemble methods, demonstrate superior predictive accuracy by learning complex patterns directly from molecular structures and large, diverse datasets [34] [30].

The choice of approach should be guided by the specific development context. For early-stage discovery involving novel chemical space, AI-driven models provide a powerful tool for rapid and accurate prioritization of drug candidates. For lead optimization within a specific chemical class, well-validated QSPR models with a clearly defined Applicability Domain (AD) can offer valuable, interpretable insights. Ultimately, the future lies in the hybrid use of these tools, where AI models handle high-throughput screening and QSPR principles ensure rigorous validation, all underpinned by the generation of high-quality, physiologically relevant experimental data.

The concept that similar molecules exhibit similar properties is a foundational pillar in chemistry, particularly in the field of drug discovery and materials science [37]. This principle, often termed the "similar property principle," posits that minor structural modifications to a molecule should not drastically alter its biological activity or chemical characteristics [38]. This principle provides the theoretical basis for predictive computational modeling, enabling researchers to forecast properties of novel compounds based on their structural resemblance to molecules with known data [37].

However, this principle has notable exceptions, most prominently "activity cliffs"—situations where structurally similar compounds exhibit significant differences in biological potency [38]. These cliffs present substantial challenges for computational modeling and highlight the nuanced interpretation required when applying similarity concepts [39]. Despite these exceptions, the similarity principle remains fundamentally important, underpinning both traditional Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) studies and modern approaches using foundation models for molecular property prediction [20].

Theoretical Foundation: Defining and Quantifying Molecular Similarity

The Similar Property Principle

The similar property principle was formally articulated by Johnson and Maggiora, stating that "similar compounds have similar properties" [37]. This deceptively simple concept provides the crucial link between molecular structure and observable macroscopic properties, enabling predictive computational approaches across chemical domains. The principle operates on the premise that structural resemblance translates to functional resemblance, whether in biological activity, reactivity, or physical properties.

Mathematical Formalization of Similarity

In practical applications, chemical similarity is typically described as the inverse of distance in molecular descriptor space [37]. This mathematical formalization enables quantitative comparisons between compounds through several approaches:

- Similarity Coefficients: The Tanimoto coefficient (also known as Jaccard similarity) is the most prevalent metric for comparing binary molecular fingerprints, measuring overlap between two fingerprint vectors relative to their union [37] [38].

- Distance Metrics: Various distance measures in multidimensional descriptor space, including Euclidean, Manhattan, and Cosine distances.

- Molecular Kernels: Advanced similarity measures used in machine learning approaches that implicitly compare molecular structures [37].

The Activity Cliff Phenomenon

A significant challenge to the similarity principle emerges through activity cliffs, which occur when structurally similar compounds targeting the same protein exhibit large differences in potency [38]. Mathematically, activity cliffs are defined by the ratio of the difference in activity between two compounds to their distance of separation in a given chemical space [38]. These exceptions to the similarity principle represent particularly rough regions in the structure-property relationship landscape and are difficult to model accurately [39].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Molecular Similarity

| Concept | Definition | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Similar Property Principle | Similar molecules tend to have similar properties [37] | Foundation for predictive modeling and chemical design |

| Molecular Similarity | Inverse of distance in molecular descriptor space [37] | Enables quantitative comparison of molecular structures |

| Activity Cliffs | Structurally similar compounds with large potency differences [38] | Challenge simplistic similarity assumptions; important for model accuracy |

| Similarity Threshold | Tanimoto coefficient >0.85 often indicates high similarity [37] | Practical benchmark for similarity searching, though context-dependent |

Traditional QSPR Approaches: Similarity-Based Empirical Modeling

Fundamental Methodology

Traditional Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling establishes mathematical relationships between molecular descriptors and experimentally measured properties [40]. These approaches directly implement the similarity principle by assuming that structurally related molecules will occupy similar positions in both descriptor space and property space. The QSPR framework has been extensively applied to diverse chemical properties, from physicochemical parameters to biological activities [26] [41].

The general QSPR workflow involves:

- Molecular Structure Representation

- Descriptor Calculation

- Statistical Model Development

- Model Validation and Application

Molecular Representation in Traditional QSPR

Traditional QSPR relies heavily on hand-crafted molecular representations that encode structural information into quantitative descriptors [20]. These representations include:

- Molecular Fingerprints: Binary or count-based vectors representing structural features [38].

- Topological Descriptors: Graph-based indices capturing molecular connectivity patterns.

- Physicochemical Descriptors: Parameters such as logP, molar refractivity, and charge distribution [40].

- Quantum Chemical Descriptors: Electronic properties derived from computational chemistry calculations [40].

Statistical Modeling Approaches

Traditional QSPR employs various statistical methods to correlate descriptors with properties:

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR): One of the earliest and most interpretable QSPR methods, though vulnerable to descriptor correlation [41].

- Partial Least Squares (PLS): Effective for handling correlated descriptors and datasets with more descriptors than compounds [41].

- Genetic Algorithm-Based Methods: GA-MLR combines feature selection with regression to identify optimal descriptor subsets [41].

Experimental Protocols in Traditional QSPR

A typical QSPR protocol for property prediction involves clearly defined steps [40]:

- Dataset Curation: Compiling experimental property data for a diverse set of compounds.

- Descriptor Calculation: Generating molecular descriptors using software such as DRAGON or CODESSA.

- Descriptor Selection: Applying feature selection techniques (e.g., heuristic method, genetic algorithms) to identify relevant descriptors.

- Model Training: Developing regression models using the selected descriptors.

- Model Validation: Assessing predictive performance through cross-validation and external test sets.

- Applicability Domain: Defining the chemical space where the model provides reliable predictions.

Diagram 1: Traditional QSPR modeling workflow based on hand-crafted representations

Modern Approaches: Foundation Models and Learned Representations

The Foundation Model Paradigm

Modern approaches to molecular property prediction have shifted toward foundation models—AI models pretrained on broad data that can be adapted to various downstream tasks [20]. Unlike traditional QSPR's hand-crafted representations, foundation models learn molecular representations directly from data through self-supervision on large unlabeled chemical datasets [20] [39]. This paradigm change represents a significant evolution in how similarity is captured and utilized for property prediction.

Foundation models for chemistry typically follow a two-stage process:

- Pretraining: Learning general molecular representations from large-scale unlabeled data.

- Fine-tuning: Adapting the pretrained model to specific property prediction tasks with limited labeled data.

Molecular Representation in Foundation Models

Modern foundation models employ sophisticated representation learning approaches:

- SMILES-Based Models: Treat molecular structures as text strings using Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System representations, applying natural language processing techniques [20] [39].

- Graph-Based Models: Represent molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, using graph neural networks to learn structural representations [39].

- 3D-Structure Models: Incorporate molecular conformation and spatial information, though these are less common due to data limitations [20].

Architectural Approaches

Foundation models employ various neural network architectures:

- Encoder-Only Models: Focus on understanding and representing input data, generating meaningful representations for further processing [20].

- Decoder-Only Models: Designed to generate new outputs by predicting one token at a time, suitable for molecular generation [20].

- Hybrid Architectures: Combine multiple approaches to leverage different molecular representations.

Experimental Protocols for Foundation Models

The experimental workflow for foundation model-based property prediction differs significantly from traditional QSPR [20] [39]:

- Pretraining Data Collection: Compiling large-scale molecular datasets (e.g., from PubChem, ZINC, ChEMBL) for self-supervised learning.

- Model Pretraining: Training foundation models using objectives like masked token prediction or contrastive learning.

- Task-Specific Fine-tuning: Adapting pretrained models to specific property prediction tasks using limited labeled data.

- Transfer Learning Evaluation: Assessing model performance across multiple chemical tasks to measure generalization capability.

- Interpretation Analysis: Understanding what chemical features the learned representations capture.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional QSPR vs. Foundation Models

Representation Learning Comparison

The fundamental difference between traditional and modern approaches lies in how they handle molecular representation:

Table 2: Comparison of Molecular Representation Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional QSPR | Foundation Models |

|---|---|---|

| Representation Type | Hand-crafted descriptors and fingerprints [20] | Learned representations from data [20] [39] |

| Domain Knowledge | Explicitly encoded by experts [20] | Implicitly learned from data patterns |

| Data Requirements | Smaller labeled datasets [40] | Large unlabeled corpora for pretraining [20] |

| Representation Flexibility | Fixed by predefined feature set | Adapts to specific tasks through fine-tuning |

| Interpretability | High - features have chemical meaning [41] | Lower - often "black box" representations |

Performance and Accuracy Considerations

Recent empirical evaluations reveal a complex performance landscape:

- Competitive Baselines: Surprisingly, traditional fingerprint-based approaches with simple machine learning models remain competitive with foundation models on many benchmark tasks [39].

- Data Efficiency: Foundation models may offer advantages in low-data regimes through transfer learning [20].

- Roughness Performance: Pretrained representations do not necessarily produce smoother structure-property relationship surfaces compared to traditional fingerprints [39].

Roughness Analysis of QSPR Surfaces

The roughness of structure-property relationships—measuring how drastically properties change with small structural modifications—provides important insights into model performance. The Roughness Index (ROGI) metric quantifies this characteristic, with higher values indicating more challenging prediction landscapes [39]. Reformulated as ROGI-XD, this metric enables comparison across different molecular representations.

Recent research demonstrates that foundation models do not produce smoother QSPR surfaces than traditional fingerprints and descriptors [39]. This finding aligns with empirical observations that these advanced models do not consistently outperform simpler baseline approaches on property prediction tasks.

Diagram 2: Foundation model approach with learned representations

Software and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Molecular Property Prediction

| Tool | Type | Key Features | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSPRpred | Open-source Python package | Comprehensive QSPR workflow support, model serialization, multi-task learning [42] | Traditional QSPR, proteochemometric modeling |

| DeepChem | Deep learning library | Diverse featurizers, deep learning models, integration with TensorFlow/PyTorch [42] | Both traditional and deep learning approaches |

| CODESSA | Descriptor calculation | Comprehensive descriptor sets, heuristic method for variable selection [41] | Traditional QSPR with topological descriptors |

| Uni-Mol | Foundation model framework | 3D molecular representations, transfer learning capabilities [42] | Modern foundation model approaches |

- Molecular Fingerprints: Daylight, Morgan (circular), atom pair, and topological fingerprints for structural similarity assessment [38].

- Descriptor Packages: Software for calculating thousands of molecular descriptors encoding structural, topological, and quantum chemical features.

- Pretrained Models: Available foundation models (ChemBERTa, ChemGPT, Molecular Graph Networks) for transfer learning applications [39].

Benchmarking Datasets

- MoleculeNet: Curated benchmark collection for molecular machine learning [39].

- TDC: Therapeutic Data Commons with focused therapeutic benchmarks [39].

- ChEMBL: Large-scale bioactivity database for training and validation [20].

The similarity principle remains fundamentally important across both traditional and modern approaches to molecular property prediction. While foundation models represent a significant methodological evolution, they build upon the same conceptual foundation as traditional QSPR: that structural similarity informs property similarity.

The comparative analysis reveals that neither approach universally dominates; each has distinct strengths and limitations. Traditional QSPR offers interpretability and reliability with smaller datasets, while foundation models provide representation flexibility and potential transfer learning benefits. Recent research suggests that the future may lie in hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both paradigms.

The continued challenge of activity cliffs and rough structure-property landscapes reminds us that the similarity principle has limitations. Future methodological developments should focus on better handling these edge cases while maintaining performance across diverse chemical spaces. As both computational power and chemical datasets grow, the precise implementation of the similarity principle will continue to evolve, but its central role in chemical prediction seems certain to endure.

From Descriptors to Deep Learning: A Practical Guide to Methodologies and Real-World Applications

Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling represents a cornerstone of computational chemistry and drug discovery, applying statistical learning to establish relationships between molecular descriptors and target properties [43]. Despite the emergence of sophisticated foundation models trained on massive chemical datasets, traditional QSPR remains vital for scenarios requiring interpretability, modest dataset sizes, and well-defined molecular domains [20]. Foundation models, while powerful for general-purpose chemical tasks, often function as "black boxes" and may lack the mechanistic interpretability that traditional descriptor-based models provide [2]. This guide details the complete workflow for building traditional QSPR models, objectively compares their performance and characteristics against modern approaches, and provides experimental protocols for key workflow stages.

The Traditional QSPR Workflow: A Detailed Protocol

Data Curation and Standardization

The initial and most critical phase involves rigorous data curation to ensure model reliability. High-throughput screening (HTS) data often contains duplicates, artifacts, and inconsistent structure representations that must be addressed before modeling [44].

Experimental Protocol: Structure Standardization

- Input Preparation: Prepare a tab-delimited file with columns for compound ID, SMILES strings, and the experimental property/activity value [44].

- Automated Curation: Implement automated curation workflows using platforms like KNIME. The workflow should include:

- Structure Standardization: Convert structures to canonical representations using tools like RDKit or Chython, handling aspects like explicit/implicit hydrogens and aromatization [43] [44].

- Filtering: Remove inorganic compounds and mixtures unsuitable for traditional QSPR modeling [44].

- Activity Balancing: For classification models, address imbalanced data via down-sampling. The rational selection method, which selects inactive compounds sharing the descriptor space of actives, is preferred over random selection as it helps define the model's applicability domain [44].

- Output: Generate standardized datasets (

FileName_std.txt) for modeling, with failed structures and warnings logged in separate files for review [44].

Molecular Descriptor Calculation

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations of molecular structures. Traditional QSPR relies on a diverse array of descriptor types, which can be calculated using various software tools.

Experimental Protocol: Descriptor Calculation with DOPtools DOPtools provides a unified Python API for descriptor calculation, integrating multiple sources and ensuring compatibility with machine learning libraries like scikit-learn [43].

- Structure Input: Read and standardize chemical structures in SMILES format using the integrated Chython library [43].

- Descriptor Types:

- Physico-chemical Descriptors: Calculate via the Mordred library, which provides a wide range of 2D and 3D molecular descriptors [43].

- Structural Fingerprints: Generate using RDKit's fingerprinting algorithms [43].

- Custom Fragment Descriptors: Utilize DOPtools' built-in functions to calculate molecular fragments. For reactions, descriptors can be calculated via Condensed Graphs of Reactions (CGRs) or by concatenating descriptors of individual reaction components [43].

- Output: A unified descriptor table ready for machine learning model training [43].

Table 1: Key Software for Descriptor Calculation in Traditional QSPR

| Software Tool | Descriptor Types | Key Features | Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOPtools [43] | Physico-chemical, Structural fingerprints, Molecular fragments, Reaction descriptors (via CGR) | Unified API for scikit-learn, Hyperparameter optimization, Command-line interface | Python library |

| RDKit [43] | Structural fingerprints, Topological descriptors | De facto standard, Open-source | Python library |

| Mordred [43] | Physico-chemical (2D/3D) | Comprehensive descriptor set (>1800 descriptors) | Python library |

| ISIDA [45] | Substructure Molecular Fragment (SMF) descriptors | Based on "sequences" and "augmented atoms" | Standalone software |

| DFT/COSMO [46] | Quantum chemical descriptors (Volume, Acidity, Basicity, Charge asymmetry) | Based on low-cost quantum chemistry | Specialist computational chemistry software |

Model Building and Hyperparameter Optimization

Once descriptors are calculated, machine learning algorithms are trained to predict the target property. Model performance is highly dependent on the optimal selection of algorithm-specific hyperparameters.

Experimental Protocol: Hyperparameter Optimization with DOPtools DOPtools uses the Optuna library for automated hyperparameter optimization, which efficiently searches the parameter space to maximize model performance [43].

- Algorithm Selection: DOPtools provides three major statistical methods out-of-the-box: Support Vector Machine (SVM), XGBoost, and Random Forest (RF) [43].

- Optimization Setup:

- Define the objective function, which typically involves a cross-validated performance metric (e.g., Q²) on the training set.

- Specify the hyperparameter search space for the chosen algorithm (e.g., number of trees in RF, learning rate in XGBoost).

- Optimization Execution: Run the Optuna optimization algorithm, which performs numerous trials, evaluating different hyperparameter combinations to find the best set for the dataset [43].

- Output: A trained model with optimized hyperparameters, ready for validation.

Model Validation and Applicability Domain

Robust validation is essential to ensure the model's predictive power for new chemicals. This involves both internal and external validation techniques, alongside defining the model's applicability domain (AD).

Experimental Protocol: Validation with rm² Metrics

The rm² metrics provide a stricter assessment of predictive ability compared to classical metrics like Q² and R²pred, especially for datasets with a wide range of response values [47].

- Internal Validation: Perform leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation on the training set. Calculate

rm²(LOO)[47]:rm² = r² * (1 - √(r² - r₀²))wherer²is the correlation coefficient between observed and LOO-predicted values with intercept, andr₀²is without intercept. A value ofrm²(LOO) > 0.5is acceptable [47]. - External Validation: Apply the final model to the held-out test set. Calculate

rm²(test)analogously using test set predictions. Similarly,rm²(test) > 0.5indicates a predictive model [47]. - Guideline: The difference between

rm²and its counterpartr'm²(calculated with axes swapped) should be small (< 0.2), providing an additional check of prediction reliability [47].

The following diagram summarizes the complete traditional QSPR workflow, from raw data to a validated predictive model.

Performance Comparison: Traditional QSPR vs. Foundation Models

The choice between traditional QSPR and foundation models depends on the specific research context, data availability, and desired outcomes. The table below provides a structured, objective comparison.

Table 2: Objective Comparison Between Traditional QSPR and Foundation Models

| Feature | Traditional QSPR | Foundation Models |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Modest dataset sizes (often 100s-1000s of compounds) [48] | Massive, broad datasets for pre-training (often millions of compounds) [20] |

| Computational Cost | Lower; feasible on standard workstations [46] | Very high; requires significant GPU resources [20] |

| Interpretability | High; models based on defined descriptors allow mechanistic interpretation [43] [46] | Low; often function as "black boxes" with limited direct interpretability [20] [2] |

| Reaction Modeling | Supported via CGR or descriptor concatenation in tools like DOPtools [43] | Limited; primarily focused on molecular rather than reaction representations [43] |

| Handling of 3D Structure | Explicitly handled by specific 3D descriptors or quantum chemical methods [46] | Often limited to 2D representations (SMILES/SELFIES) due to data availability [20] |

| Performance on Small, Focused Datasets | Generally excellent and reliable [47] | Can be prone to overfitting; may require extensive fine-tuning [20] |

| Automation & CLI Support | High in modern tools (e.g., DOPtools CLI for automatic workflows) [43] | Varies; often requires custom scripting for integration into automated pipelines |

| Representative Tools | DOPtools, RDKit, ISIDA, MOE [43] | Molecular transformers, GPT-based models, BERT-based models [20] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

This section details the key software and computational tools required to implement the traditional QSPR workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Traditional QSPR

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Workflow | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| KNIME Analytics Platform [44] | Workflow Management | Data curation, standardization, and balancing via automated workflows. | Open-source, user-friendly visual interface for building complex data pipelines. |

| DOPtools [43] | Python Library | Unified descriptor calculation, hyperparameter optimization, and model building. | Unified API for scikit-learn, specialized for reaction modeling, includes CLI. |

| RDKit [43] | Cheminformatics Library | Chemical structure handling, standardization, and fingerprint calculation. | De facto open-source standard with extensive functionality and community support. |

| Mordred [43] | Descriptor Calculator | Comprehensive calculation of 2D and 3D molecular descriptors. | Provides over 1800 descriptors, complementing those available in RDKit. |

| Optuna [43] | Python Library | Hyperparameter optimization for machine learning models. | Efficiently automates the search for the best model parameters, integrated in DOPtools. |

| Chython [43] | Cheminformatics Library | Reading and standardizing chemical structures (SMILES) and handling CGRs. | Critical for reaction representation within the DOPtools ecosystem. |

| ADF/COSMO-RS [46] | Quantum Chemistry Software | Calculating quantum chemical descriptors (e.g., volume, acidity, basicity). | Provides theoretically rigorous descriptors for LSER correlations from low-cost DFT calculations. |

Traditional QSPR modeling, powered by modern, automated tools like DOPtools, remains a powerful and indispensable methodology in the computational chemist's arsenal. Its strengths in interpretability, efficiency with modest-sized datasets, and robust validation frameworks make it highly suitable for many practical drug discovery and materials science problems. Foundation models represent a transformative advance for exploring vast chemical spaces but have not rendered traditional QSPR obsolete. Instead, they offer a complementary approach. The choice between them should be guided by the specific problem, data resources, and the need for interpretability versus sheer predictive scope. A hybrid future, where the interpretability of traditional QSPR informs and validates the discoveries of foundation models, appears to be the most promising path forward.