Beyond Keyword Stuffing: A Scientific Writer's Guide to SEO and Discoverability in 2025

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with evidence-based strategies to enhance the online discoverability of their publications without resorting to keyword stuffing.

Beyond Keyword Stuffing: A Scientific Writer's Guide to SEO and Discoverability in 2025

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with evidence-based strategies to enhance the online discoverability of their publications without resorting to keyword stuffing. It covers the foundational risks of poor keyword practices, practical methodologies for natural keyword integration, advanced troubleshooting for optimization, and validation techniques to measure success. By aligning with modern search engine algorithms and user intent, this article empowers authors to increase their research visibility, readership, and potential for citation in an increasingly digital academic landscape.

Why Keyword Stuffing Harms Your Scientific Impact: Risks and Modern Search Realities

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

A: This is a classic symptom of the "discoverability crisis" [1] [2]. When academics search for literature, they use a combination of key terms. If your paper's title, abstract, and keywords lack the most common terminology used in your field, search engines and databases may fail to surface your work in results [1]. The problem is not the quality of your research, but its accessibility to search algorithms and, consequently, to your peers.

- Diagnosis: Compare your paper's title and abstract with 5-10 highly-cited recent papers in your field. Identify key terms and phrases that appear frequently in these works but are missing from yours.

- Solution: Revise your title and abstract to incorporate these missing high-value terms naturally. Ensure the most important keywords appear early in the title and abstract, as some search engines truncate long text [2].

Q: My paper was rejected in part because the title was "misleading." How can I balance accuracy with discoverability?

A: A title must be both descriptive for discoverability and accurate for research integrity [1]. The goal is to frame your specific findings within a broader, appealing context without inflating the scope of your work.

- Diagnosis: Titles that are overly narrow (e.g., including a specific species name) or overly broad (e.g., implying generalizability from a specific case) can reduce a paper's appeal and accuracy [1].

- Solution: Use a structured title format. A creative or broad-scope main title can be paired with a more descriptive subtitle using a colon. This ensures the most important keywords are in the primary title position, which is weighted most heavily by search algorithms [2]. For example, instead of "A Study on P. vitticeps," use "Thermal Tolerance in Reptiles: A Case Study on Pogona vitticeps" [1].

Q: What is "keyword stuffing" in a scientific paper, and how can I avoid it?

A: Keyword stuffing is the practice of excessively repeating key terms in the abstract or keyword list in an unnatural way, akin to a "desperate attempt to trick Google into ranking you higher" [3]. In an academic context, this means forcing in key phrases redundantly, which undermines optimal indexing and readability [1]. A survey of 5,323 studies found that 92% used keywords that were redundant with words already in the title or abstract [1].

- Diagnosis: Read your abstract aloud. If it sounds robotic or repetitive, or if you have used the same key phrase more than twice in a short paragraph, you may be stuffing keywords.

- Solution: Use synonyms and related terminology [3] [4]. Instead of repeating one phrase, use a cluster of related terms that researchers might search for. For a paper on "survival rates," you might also naturally incorporate terms like "mortality," "longevity," or "life-span" [1] [4]. Focus on creating content that is natural and user-focused, not written for an algorithm [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

A: While many journals impose strict word limits, our survey of journals found that authors frequently exhaust abstract word limits, especially those capped under 250 words, suggesting guidelines may be overly restrictive [1]. A longer abstract allows for the natural incorporation of more key terms. Advocate for relaxed abstract limitations where possible, and always use the full word count allotted to comprehensively describe your work and its terminology [1].

Q: Should I use humorous or creative titles for my research papers?

A: While one study found that papers with humorous titles can garner more citations, this approach requires caution [1]. Humour often relies on cultural references that may not be universal and can alienate non-native English speakers or make the paper's subject unclear [1] [2]. If you use a creative title, always pair it with a descriptive subtitle separated by a colon (e.g., "There are no cats in America!: The Sea Voyage as a Representation of Liminal Migration Experiences"). This ensures search engines and readers can immediately identify your topic [2].

Q: How does keyword choice affect my paper's inclusion in meta-analyses and systematic reviews?

A: Directly and significantly. Literature reviews and meta-analyses rely heavily on Boolean searches of large databases using specific key terms from titles, abstracts, and keywords [1] [2]. If your paper does not contain the terminology used in these search strings, it will be absent from the initial result set, making its inclusion in these high-impact syntheses impossible [1] [6]. Using the most common terminology in your field is therefore critical for inclusion in evidence synthesis.

Quantitative Data on the Discoverability Crisis

The following data, synthesized from a survey of 230 journals and 5,323 studies in ecology and evolutionary biology, highlights key challenges in current publishing practices [1].

| Metric | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Abstract Word Limit Exhaustion | Authors frequently use the entire word count, especially under 250-word limits [1] | Suggests restrictive guidelines may hinder the natural inclusion of key terms. |

| Keyword Redundancy | 92% of studies used keywords that were already present in the title or abstract [1] | Indicates widespread suboptimal indexing and a misunderstanding of keyword purpose. |

| Title Length Trend | Titles have been getting longer without significant negative consequences for citation rates [1] | Challenges the notion that shorter titles are always better, though excessively long titles (>20 words) are still discouraged. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing a Manuscript for Discovery

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology to "optimize" a research manuscript for maximum discoverability in academic search engines and databases.

Objective: To systematically integrate high-value, common terminology into a manuscript's title, abstract, and keywords without engaging in keyword stuffing or compromising research integrity.

Materials:

- Draft of your research manuscript.

- Access to a major academic database (e.g., Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar).

- List of 5-10 recent, highly-cited papers in your direct research area.

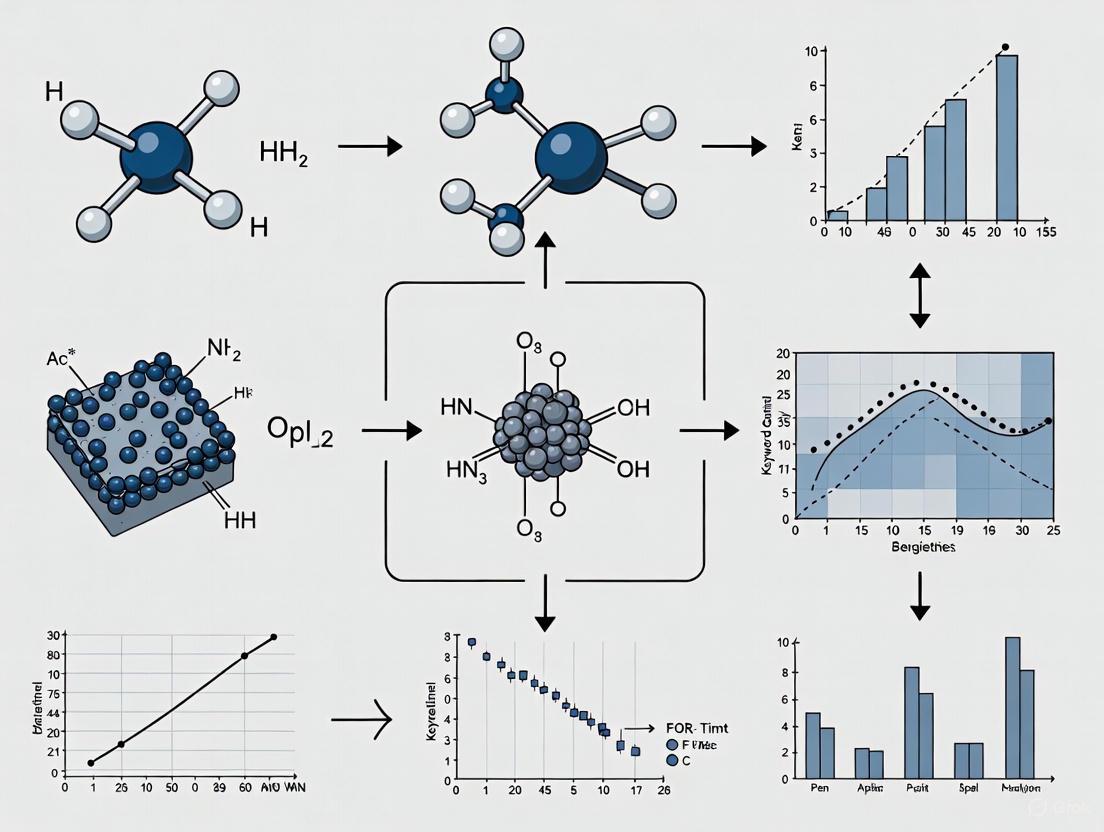

Workflow: The following diagram outlines the core optimization workflow.

Procedure:

- Identification of Benchmark Papers: Compile a list of 5-10 recent (last 5 years), highly-cited papers that are directly related to your research.

- Term Extraction: Analyze the titles, abstracts, and keyword lists of these benchmark papers. Identify the most frequently used nouns, noun phrases, and technical jargon that define the field. Tools like Google Trends can help identify commonly searched terms [3].

- Gap Analysis: Create a table comparing the high-frequency terms from Step 2 against your manuscript's title, abstract, and keywords. Identify key terms that are missing from your manuscript.

- Manuscript Revision:

- Title: Integrate the most important 1-2 missing terms. Place them as early as possible. Consider a main title: subtitle structure if using a creative element [2].

- Abstract: Weave the missing terms naturally into the narrative. Ensure the abstract is descriptive and accurately reflects the paper's content. Adopting a structured abstract format can help ensure all key aspects of the research are covered, naturally incorporating more terminology [1].

- Keywords: Select 5-8 keywords that are not already present in the title. Use this section to capture important concepts, methods, or models that you could not fit naturally into the title or abstract. Include variations like American and British English spellings (e.g., "behavior" and "behaviour") to broaden reach [1].

- Readability and Integrity Check: Read the revised title and abstract aloud. Ensure the language is natural and flows well, and that all claims are accurate and not inflated. The text must be written for humans first and algorithms second [5] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Academic Search Engine Optimization (ASEO)

| Tool / Solution | Function in "Optimization Experiment" |

|---|---|

| Academic Databases (Scopus, Web of Science) | Used to identify benchmark papers and analyze the terminology of high-impact research in your field [1]. |

| Google Scholar | A primary search engine for academics; understanding its indexing helps tailor content for its algorithm, which scans the full text of open access articles [2]. |

| Google Trends / Keyword Tools | Helps identify key terms that are more frequently searched online, providing data on common terminology [1] [3]. |

| Thesaurus / Lexical Resources | Provides variations of essential terms (synonyms) to improve readability and discoverability without keyword stuffing [1] [4]. |

| Structured Abstract Format | A framework for writing abstracts that ensures all key sections (e.g., Background, Methods, Results, Conclusion) are covered, maximizing the natural incorporation of key terms [1]. |

Logical Pathway: The Consequences of Keyword Practices

The following diagram maps the logical relationship between keyword strategies and their ultimate impact on research visibility and impact.

FAQ

What is keyword stuffing in a modern context? Keyword stuffing is the practice of excessively and unnaturally using a specific keyword or phrase in your content in an attempt to manipulate search engine rankings [7]. In 2025, this is not limited to simple repetition but also includes over-optimizing other elements like anchor text, making your content unreadable and harming the user experience [7] [8].

Why is keyword stuffing considered a bad SEO practice? Search engines like Google can now easily recognize keyword-stuffed content [7]. Instead of improving your rankings, this tactic can lead to penalties, causing your site's ranking to drop or for pages to be removed from search results entirely [7] [9] [8]. It also damages your site's credibility and trustworthiness with users [7].

Does keyword stuffing only refer to overusing a primary keyword? No. A prevalent form of modern keyword stuffing is over-optimized anchor text [7] [8]. This occurs when you repeatedly use exact-match keywords as the clickable text in your hyperlinks, which can appear spammy and trigger search engine penalties just like traditional keyword stuffing [7].

How is modern keyword strategy different from keyword stuffing? Modern SEO treats keywords as signals, not rulers [10]. The focus has shifted from exact-match repetition to topically coherent, authoritative, and useful content that addresses user intent [10]. The goal is to answer the user's question or need with relevance and depth, often by semantically enriching content with related terms and synonyms [7] [10].

Diagnostic Guide: Identifying Keyword Stuffing in Your Manuscript

Use the following table to quantitatively assess your text and diagnose potential keyword stuffing.

| Diagnostic Metric | Outdated Practice (Stuffing Indicator) | Modern Best Practice (2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Keyword Density | Main keyword comprises an excessively high percentage of the text [9]. | Main keyword used 3-5 times in 1,500-2,500 words; overall density of 1-2% [9]. |

| Anchor Text Variety | Over-optimized, using exact-match keywords excessively for internal/external links [7]. | A natural, diverse mix of branded, generic, and descriptive anchor text [7]. |

| Content Readability | Text sounds unnatural, robotic, and is written for search engines, not humans [7]. | Content is written naturally, prioritizes readability, and flows conversationally [7] [10]. |

| Topical Coverage | Focuses on a single keyword without exploring related concepts [10]. | Content is enriched with semantic SEO, using synonyms and Latent Semantic Indexing (LSI) keywords [9] [10]. |

| User Intent Alignment | Ignores the "why" behind a search query; content doesn't satisfy user goals [10]. | Content is structured to perfectly match user intent (informational, commercial, transactional, navigational) [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: Remediating and Preventing Keyword Stuffing

Objective: To systematically identify and correct keyword stuffing in a text body, and to establish a workflow for creating content that aligns with modern search engine guidelines.

Materials & Reagents:

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Semantic SEO Analysis Tool (e.g., Clearscope, SurferSEO) | Guides optimization without overloading by suggesting related terms and topics [7]. |

| AI-Assisted Ideation Platform (e.g., ChatGPT) | Generates semantically similar keywords and natural language variations for the target topic [7] [10]. |

| Keyword Research Suite (e.g., SEMrush, Ahrefs) | Identifies relevant topics with search potential and analyzes competitor content for topical coverage [7]. |

| Readability & Grammar Checker | Ensures the final content is grammatically correct and flows naturally for a human audience [7]. |

Methodology:

- Intent-First Topic Ideation: Before writing, define the core topic and the user's search intent. Write a single sentence summarizing the key insight the user should gain, ensuring the content is framed to answer their question from the start [11] [10].

- Semantic Enrichment: Instead of forcing a primary keyword, use your research tools to generate a list of synonyms, related terms, and long-tail question phrases. Integrate these throughout the content to provide context and depth, helping search engines understand the content thematically [7] [9] [10].

- Natural Keyword Integration: Write the content for the user first, focusing on clarity and comprehensiveness. Once the draft is complete, review it and sparingly integrate the primary keyword and its semantic variations only where it feels natural and does not disrupt the flow [7] [9].

- Anchor Text Diversification: Audit all hyperlinks in your content. Ensure the clickable text uses a variety of descriptive, branded, and generic phrases (e.g., "as this study shows," "learn more about our methodology," "Heroic Rankings") rather than repetitive exact-match keywords [7].

- Validation and Readability Check: Read the final text aloud. If it sounds unnatural or repetitive to a human, it will likely be flagged by search engines. Use your readability tools to confirm the text is accessible and clear [7].

Logical Workflow for Keyword Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for integrating keywords into your content without crossing into keyword stuffing territory.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is keyword stuffing? Keyword stuffing is the practice of excessively and unnaturally filling a web page with keywords, or their synonyms, with the primary intent of manipulating a site's search engine rankings. This can be either visible in the content or invisible, where text is hidden from users in the page's HTML or by making it the same color as the background [12].

How do search engines penalize keyword-stuffed content? Search engines apply two main types of penalties [13]:

- Algorithmic Penalties: Applied automatically by algorithms like Panda (targets low-quality, thin content) and Penguin (targets unnatural link profiles). These cause a steady drop in rankings and traffic [13] [14].

- Manual Penalties: Applied after a human reviewer at Google determines your site violates its Webmaster Guidelines. You receive a notification in Google Search Console, and your site may be removed from search results until you fix the issue and submit a reconsideration request [13].

What is a high bounce rate, and why is it a problem? A high bounce rate occurs when visitors leave your website after viewing only one page without any interaction [4]. In the context of keyword stuffing, it's a problem because it signals to search engines that your content is not helpful or relevant to users' queries. This poor user experience can lead to further ranking declines, even without a formal penalty [12].

As a researcher, how can I check my own content for keyword stuffing?

- Read Aloud: Read your text aloud; if it sounds forced or unnatural, it needs revision [4].

- Use Analysis Tools: Tools like Yoast SEO or SEMrush can analyze keyword density and highlight over-optimization [4].

- Leverage Writing Assistants: Tools like Grammarly or the Hemingway Editor can identify repetitive phrasing and improve readability [4].

My site traffic dropped after a core update. Does that mean I was penalized for keyword stuffing? Not necessarily. A drop in rankings after a core update can mean that other sites' content was deemed more relevant and helpful than yours. Google recommends focusing on improving your overall content quality and E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness) rather than assuming a penalty [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Keyword Stuffing Issues

Symptom: Sudden or Gradual Drop in Organic Search Traffic

| Investigation Step | Action & Diagnostic Tool | Key Metric to Check |

|---|---|---|

| Check for Manual Actions | Review Google Search Console for manual action notifications under the "Manual actions" section in the left-hand menu [13]. | Presence of a manual penalty and its stated reason (e.g., "Unnatural links," "Thin content"). |

| Cross-reference Algorithm Updates | Check your traffic drop dates against Google's official algorithm update history [16]. Use resources like Search Engine Land [15]. | Correlation between a confirmed update roll-out date and the start of your traffic decline. |

| Analyze User Behavior | Use Google Analytics to examine behavior flow and engagement metrics for affected pages. | Bounce Rate: A significant increase suggests users aren't finding what they expected. Average Session Duration: A decrease indicates content isn't engaging users [14]. |

Symptom: High Bounce Rates on Key Landing Pages

| Investigation Step | Action & Diagnostic Tool | Key Metric to Check |

|---|---|---|

| Perform a Content Readability Audit | Read the page content aloud. Use tools like the Hemingway App to get a readability score [4]. | Forced or robotic language; overuse of a primary keyword or its variations. |

| Analyze Keyword Density | Use the SEO analysis functionality in tools like Yoast SEO or SEMrush to check the frequency of your target keywords [4]. | While no strict rule exists, a density that feels unnatural (e.g., well over 2-5%) is a red flag [12]. |

| Evaluate Content Structure | Check if the page uses clear headings, bullet points, and tables to break up text and improve scannability [4]. | Large, uninterrupted blocks of text; lack of clear H2/H3 subheadings. |

The following tables consolidate key quantitative data related to search penalties and user engagement metrics.

Table 1: Google Algorithm Updates Targeting Low-Quality Content (2022-2025)

| Update Name | Year | Primary Focus & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Helpful Content Update | 2022-2023 | Systemwide signal promoting people-first content over search-engine-first content. Notably reduced unhelpful content [15]. |

| March 2024 Core Update | 2024 | A complex update that incorporated the helpful content system into Google's core ranking systems. Reduced unhelpful content in search results by 45% [15]. |

| Panda Algorithm | Ongoing | Algorithmic penalty targeting thin, low-quality, or duplicate content [13]. |

| August 2025 Spam Update | 2025 | A global spam update targeting various spam types across all languages [15] [16]. |

Table 2: User Engagement Metrics Indicative of Content Quality Issues

| Metric | Typical Benchmark for Healthy Content | Indicator of Keyword Stuffing/Poor Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Bounce Rate | Varies by industry; lower is generally better. | A bounce rate shooting up to 80-90% is a strong signal that users are immediately rejecting the content [4] [14]. |

| Average Time on Page | Long enough to read the content. | A very short duration (e.g., under 15 seconds) suggests users quickly determined the page was unhelpful [4]. |

| Pages per Session | Higher than 1.0. | Consistently at or near 1.0, indicating no further exploration of the site [17]. |

Experimental Protocols for SEO Analysis

Protocol 1: Quantifying User Engagement and Its Correlation to Content Quality

Objective: To empirically measure user engagement and determine if a page's high bounce rate is correlated with poor content quality, such as keyword stuffing.

Methodology:

- Selection of Test Pages: Identify two sets of pages from the same website: one set suspected of having quality issues (Group A) and one set of high-performing, user-valued pages (Group B).

- Data Collection Period: Monitor traffic and user behavior for a minimum of 30 days to gather sufficient data.

- Instrumentation:

- Implement Google Analytics 4 with enhanced event tracking.

- Install a heatmap tool to record user clicks, scrolling depth, and mouse movements on the selected pages.

- Variables Measured:

- Primary Dependent Variable: Bounce Rate.

- Secondary Dependent Variables: Average Engagement Time, Scroll Depth (percentage of page scrolled).

- Independent Variable: Content quality score (a composite score based on a predefined rubric assessing readability, keyword usage, and comprehensiveness).

Analysis:

- Perform a statistical comparison (e.g., t-test) of the average bounce rates and engagement times between Group A and Group B.

- Analyze heatmaps to visualize where users most frequently click and how far they scroll on Group A pages versus Group B pages.

Protocol 2: A/B Testing for Content Optimization and Ranking Recovery

Objective: To test whether rewriting a penalized or poorly-performing page to eliminate keyword stuffing and improve quality leads to a recovery in search rankings and user engagement.

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: For a chosen underperforming page (the control, Variant A), record its current average ranking position, organic traffic, and bounce rate for 14 days.

- Intervention: Create a new version of the page (Variant B) that implements corrective actions:

- Deployment: Use A/B testing software to split incoming organic traffic evenly between Variant A and Variant B for a period of 30 days.

- Data Collection: Continuously track the ranking, traffic, bounce rate, and conversion rate (if applicable) for both variants.

Analysis:

- Compare the performance metrics of Variant B against the baseline (Variant A).

- A statistically significant improvement in rankings and user engagement for Variant B validates the effectiveness of the content optimization strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following tools are essential for diagnosing and treating issues related to keyword stuffing and search penalties.

Table 3: Essential Tools for SEO Health and Content Analysis

| Research Reagent (Tool) | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Google Search Console | A diagnostic tool that provides critical data on search performance, crawl errors, and manual penalties. Essential for receiving official communications from Google [13]. |

| Google Analytics 4 | Measures user behavior and engagement metrics (bounce rate, session duration). Provides the quantitative data needed to correlate content quality with user satisfaction [17]. |

| Readability Analyzers (e.g., Hemingway App) | Functions as a "microscope" for text, highlighting hard-to-read sentences, adverbs, and passive voice, which are indicators of unnatural writing [4]. |

| SEO Suite (e.g., SEMrush, Ahrefs) | Acts as a "DNA sequencer" for your website's SEO health. Conducts in-depth audits to identify keyword stuffing, thin content, and toxic backlinks [4] [14]. |

| Heatmapping Software (e.g., Hotjar) | Provides a "live cell imaging" view of how users interact with your page, revealing if they engage with content or scroll away quickly [17]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between keyword stuffing, its direct consequences, and the path to recovery.

Understanding Redundant Indexes

In database management, a redundant index is a B-tree index that is a complete prefix, or a leftmost subset, of another existing index [18]. For example, if you have an index on columns (A, B, C), then an index on just (A) or (A, B) is considered redundant. The longer index can already serve any query that the shorter, redundant index would.

Duplicate indexes are a more severe case, where the same columns are indexed multiple times in the same order, such as KEY (A, B) and KEY (A, B) [18]. This provides no performance benefit and only incurs costs.

The Performance Impact of Redundant Indexes

While redundant indexes generally do not directly slow down SELECT query performance, they impose significant hidden costs that undermine overall database efficiency [19]. The core problem lies in the overhead they introduce during data modification operations and resource consumption.

The following table summarizes the key performance impacts:

| Impact Area | Effect of Redundant Indexes |

|---|---|

| Write Performance | Slows down INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE operations, as all indexes on a table must be updated [20] [21]. |

| Disk Utilization | Consumes valuable storage space unnecessarily [20]. |

| Memory Buffer Efficiency | Wastes finite memory buffer space, potentially pushing out useful table or index data and increasing disk I/O [20]. |

| Query Planning | Increases query compilation time, as the optimizer must evaluate more candidate indexes [20] [19]. |

Identifying and Removing Redundant Indexes

Detection Methodology

1. For PostgreSQL Databases:

PostgreSQL provides a statistics view called pg_stat_user_indexes that you can query to find non-unique indexes that have never been scanned [20].

In PostgreSQL 16 and later, you can use the last_idx_scan field to find indexes that haven't been used in a long time [20].

2. For MySQL and SQL Server: While the search results do not provide specific SQL queries for these databases, the general principle remains the same [18]. You can:

- Use dedicated tools, such as the Database Engine Tuning Advisor in SQL Server, to analyze your workload and get index recommendations [21].

- Manually inspect database schemas to look for indexes that are clear prefixes of another.

Removal Protocol

Once you have identified a candidate redundant index, follow this experimental protocol:

Baseline Performance: Before removal, record baseline metrics for the application. Key metrics include:

- Latency of critical

INSERT,UPDATE, andDELETEoperations. - Execution time of important

SELECTqueries that you suspect might be using the index. - Overall database storage size.

- Latency of critical

Execute Removal: Use the

DROP INDEXcommand to remove the redundant index. It is a best practice to perform this operation during a maintenance window.Validate Performance: After removal, re-measure the same metrics from your baseline.

- Expected Result: You should observe improved write performance and reduced storage space without degradation to your critical read queries [20].

- Contingency Plan: If a key query slows down unexpectedly, be prepared to restore the index. In some cases, you may need to modify a remaining index (e.g., by adding an included column) to better cover the query's needs [21].

Visualizing Index Relationships and Impact

The diagram below illustrates how redundant indexes are related to other index types and their primary negative effects on the database system.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Are there any legitimate cases for keeping a redundant index?

Yes, in some scenarios a redundant index can be justified. If the longer index is very wide (e.g., includes a large VARCHAR column) and a frequent query only needs the first column, a smaller redundant index might be more efficient to read [18]. Similarly, if a specific query can be satisfied entirely by a smaller index (a "covering index"), it might be worth keeping for peak read performance, but the trade-off with write overhead must be carefully measured.

Q2: How do redundant indexes affect SELECT query performance? The direct impact is often minimal, as the query optimizer will typically choose the most efficient index available [19]. The primary negative effects are indirect: the increased query compilation time as the optimizer evaluates more options, and the overall system burden from increased write latency and reduced resource efficiency [20].

Q3: What is the difference between a redundant index and a duplicate index?

A duplicate index is an exact copy—the same columns in the same order. It serves no purpose and should always be removed [18]. A redundant index is a leftmost prefix of another index (e.g., (A) is redundant to (A, B)). While the longer index can handle the same queries, there are rare cases where the shorter one might be kept for performance reasons, as noted in the FAQ above [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key solutions and tools for diagnosing and resolving database indexing issues.

| Tool / Solution | Function |

|---|---|

pg_stat_user_indexes View |

A PostgreSQL system view that provides vital statistics on index usage, such as the number of scans, essential for identifying unused indexes [20]. |

| Database Engine Tuning Advisor | A SQL Server tool that analyzes a workload and provides recommendations for creating, dropping, or modifying indexes to optimize performance [21]. |

sys.dm_db_index_usage_stats |

A SQL Server dynamic management view that shows how many times indexes were used for user queries, helping to identify candidates for removal [21]. |

EXPLAIN / EXPLAIN ANALYZE |

PostgreSQL and MySQL commands that show the execution plan of a query, allowing you to verify which indexes are being used and how [20]. |

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, creating effective troubleshooting guides presents a paradox: how to be easily discovered through search without compromising the technical integrity and clarity of the information. The modern solution, aligned with Google's core guidelines, is to shift focus from algorithmic manipulation to genuine user assistance. Keyword stuffing—the practice of overloading content with keywords to manipulate search rankings—is not only an outdated tactic but one that actively harms content quality and user experience [22] [3]. Google's AI-powered systems can now detect such manipulation, leading to ranking penalties or removal from search results [22]. More critically, content created for algorithms rather than people is often frustrating, unnatural to read, and damages the credibility of the author and their institution [3]. This technical support center is designed on the principle that the most sustainable and ethical SEO strategy is to create comprehensive, authoritative, and genuinely helpful content that addresses the specific problems of our scientific audience.

Core Concepts: Understanding the "Why"

What is Keyword Stuffing and Why is it a Problem?

Google officially defines keyword stuffing as "loading webpages with keywords in an attempt to manipulate a website’s ranking" [22]. In a scientific context, this might manifest as unnaturally repeating a specific phrase like "protein quantification assay troubleshooting" numerous times in a short guide, rather than using it purposefully and in context.

The risks are significant [22] [3]:

- Ranking Penalties: Google's AI can detect manipulation and respond with dramatic ranking drops.

- Poor User Experience: Keyword-heavy content reads unnaturally, frustrates users, and undermines trust.

- Lost Credibility and Traffic: Scientists seeking reliable information will quickly leave a site that appears spammy, leading to high bounce rates and diminished authority.

The Modern Alternative: User-First Content and Semantic SEO

The alternative to keyword stuffing is to create content that thoroughly satisfies user intent. This involves:

- Comprehensive Topic Coverage: Address the user's query completely, using a variety of related terms and concepts that naturally arise from the topic [3].

- Natural Language: Write conversationally, as you would explain a concept to a colleague [22].

- Strategic Keyword Use: Place important terms in key locations like titles and headings, but let them enhance, rather than drive, the content [23].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Optimizing Scientific Content for Discovery

Q1: How do I choose the right keywords for my scientific troubleshooting guide without resorting to stuffing?

A: Effective keyword selection is foundational. Follow this experimental protocol:

- Identify Core Concepts: Brainstorm the central topics of your guide (e.g., "Western blot," "background noise," "protocol optimization").

- Analyze Search Intent: Use tools like Google's Keyword Planner or AnswerThePublic to understand what users are searching for and the language they use. Focus on long-tail keywords (longer, more specific phrases) which are easier to use naturally and often have clearer user intent [22] [23]. For example, "reduce non-specific binding Western blot" is more specific and valuable than just "Western blot."

- Prioritize by Relevance and Specificity: Choose keywords that are specific enough to be meaningful but not so niche that no one searches for them. "Coastal habitat" is a better target than the overly broad "ocean" or the too-specific "salt panne zonation" [23].

- Build Keyword Clusters: Organize your keywords into related groups to cover a topic thoroughly. For a guide on "ELISA troubleshooting," a cluster might include "ELISA sensitivity," "assay buffer composition," and "standard curve accuracy" [3]. This helps you create comprehensive content that naturally incorporates related terms.

Q2: What is the optimal way to place keywords in a technical document?

A: Keyword placement should be strategic, not random. The following table summarizes key locations and best practices, framing them as an experimental setup.

Table 1: Experimental Protocol for Strategic Keyword Placement

| Location | Purpose | Best Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Title | To accurately describe content and attract clicks. | Include primary keywords within the first 65 characters [23]. |

| Headings (H1, H2, etc.) | To structure content and signal topic hierarchy. | Use keywords in headings to break up content and signal relevance [3]. |

| First Paragraph | To set context and establish topic relevance. | Naturally introduce the topic and primary keywords early [3]. |

| Body Content | To provide value and comprehensively address the topic. | Use keywords and their synonyms naturally; prioritize readability over frequency [22]. |

| Image Alt Text | To describe images for accessibility and search. | Include relevant keywords when it accurately describes the image [3]. |

Q3: How can I ensure my content is user-first and not algorithm-first?

A: Employ this quality control checklist:

- Read Aloud Test: Read your content aloud. If it sounds robotic or unnatural, revise it [22].

- Question-Focused Design: Structure your content to directly answer the questions your audience is asking [22].

- Value Assessment: Every section should provide actionable, practical value. If a sentence or paragraph exists only to hold a keyword, remove it.

- Synonyms and Related Terms: Use a diverse vocabulary to showcase expertise and help search engines understand context. For example, vary usage between "cell viability assay," "cytotoxicity assay," and "MTT assay" as appropriate [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Common Experimental Roadblocks

Issue: High Background Signal in Immunofluorescence (IF) Staining

This guide demonstrates how to structure a user-centric troubleshooting resource that naturally incorporates key terms and concepts.

1. Problem Definition & Initial Assessment A high background signal, or noise, can obscure specific staining, making data interpretation difficult. This protocol will help you systematically identify and resolve the sources of background fluorescence in your IF experiments.

2. Diagnostic Framework & Resolution Protocol The following workflow outlines a logical, step-by-step process for diagnosing and resolving high background issues. It emphasizes understanding the "why" behind each step, aligning with the goal of educating the user.

Diagram 1: IF High Background Diagnostic Workflow

3. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents used in the troubleshooting process, explaining their function in resolving the experimental issue.

Table 2: Key Reagents for IF Background Troubleshooting

| Reagent | Function/Explanation in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| BSA or Serum | Used as a blocking agent to bind non-specific sites on the tissue sample, preventing antibodies from sticking where they shouldn't. |

| Triton X-100 or Tween-20 | Detergents added to wash buffers to improve penetration and wash away unbound antibodies and reagents, reducing background. |

| Antibody Diluent Buffer | A optimized buffer used to dilute primary and secondary antibodies, often containing protein carriers to stabilize the antibody and reduce non-specific binding. |

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | A common fixative. Inadequate fixation can cause antigen leakage, while over-fixation can mask epitopes, both leading to high background. |

Issue: Low Transfection Efficiency in Mammalian Cell Lines

1. Problem Definition & Initial Assessment Low transfection efficiency results in a small percentage of cells taking up and expressing the foreign nucleic acid, compromising experimental results. This guide addresses common pitfalls.

2. Diagnostic Framework & Resolution Protocol The diagram below maps the logical decision-making process for improving transfection outcomes, from assessing cell health to optimizing reagent use.

Diagram 2: Transfection Optimization Workflow

3. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Transfection Optimization

| Material/Reagent | Function/Explanation in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| Transfection Reagent | A cationic lipid or polymer that forms complexes with nucleic acids, neutralizing their charge and facilitating fusion with the cell membrane. |

| Opti-MEM or Serum-Free Media | Serum can interfere with complex formation; using these media during the transfection process improves efficiency for many reagents. |

| Reporter Plasmid (e.g., GFP) | A positive control plasmid expressing an easily detectable marker (like Green Fluorescent Protein) to quickly assess and optimize efficiency. |

| Cell Counters & Viability Assays | Essential for ensuring cells are seeded at the recommended density and are in a healthy, log-phase growth state for optimal transfection. |

Adhering to Google's guidelines is less about following a rigid set of technical rules and more about embracing a core philosophy: create content for people first [22]. For the scientific community, this means prioritizing clarity, accuracy, and comprehensiveness. By focusing on the real-world problems faced by researchers—such as troubleshooting a failing experiment—and providing detailed, logically structured, and genuinely helpful solutions, your content will naturally satisfy both your users and search engine algorithms. Avoid the shortcut of keyword stuffing, which ultimately undermines scientific communication. Instead, invest in building authoritative resources that earn trust and visibility through their inherent quality and utility.

Writing for Humans and Algorithms: Practical SEO Integration for Manuscripts

In the modern digital research landscape, strategic keyword selection is a fundamental scientific competency. It is the primary mechanism that ensures your work is discoverable, accessible, and impactful within the global scientific community. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, effective keyword use is not about manipulating search algorithms but about precisely mapping your research to the terminology and queries used by your peers. This guide establishes a formal framework for selecting and implementing scientific terms, directly supporting the broader thesis that avoiding keyword stuffing is essential for maintaining the integrity, clarity, and reach of scientific publishing. By adhering to the protocols outlined herein, you will enhance your work's visibility while upholding the highest standards of scholarly communication.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Keyword Selection Issues & Solutions

This section addresses specific, high-priority challenges researchers encounter when selecting keywords for manuscripts, grants, and data repositories.

FAQ 1: How do I choose between a specific chemical compound and a broader drug class name as a keyword?

- Problem: Overly specific terms may limit discoverability, while overly broad terms may drown your work in irrelevant results.

- Solution: Employ a hierarchical strategy. Use the specific compound name (e.g., "ibrutinib") as a primary keyword to ensure precision for experts. Then, incorporate the broader drug class (e.g., "Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor") as a secondary keyword to capture researchers exploring the entire therapeutic class. This approach aligns with modern search engines that understand semantic relationships and user intent [10].

- Protocol: Identify the specific entity in your study. Trace its classification upward through two broader levels (e.g., "pembrolizumab" -> "anti-PD-1 therapy" -> "cancer immunotherapy"). Select one keyword from each level for a balanced profile.

FAQ 2: My research involves a well-known gene or protein with an outdated name. Which should I use?

- Problem: Using obsolete terminology can make your work invisible, even if it is semantically correct.

- Solution: Prioritize official nomenclature as designated by authoritative databases like HGNC (for genes) or UniProt (for proteins). The official symbol (e.g., "EGFR") should be a mandatory keyword. Include commonly used synonyms or previous names (e.g., "HER1", "ERBB1") in a secondary capacity, as fellow researchers might still use these terms in their searches [24].

- Protocol: Consult the relevant authoritative database for your field (e.g., HGNC, UniProt, IUPHAR) to verify the official designation. List the official symbol and name as primary keywords. Add one or two of the most prevalent synonyms as additional keywords.

FAQ 3: How many keywords are optimal, and where should I place them in my manuscript?

- Problem: Insufficient keywords limit reach, while excessive keywords appear spammy and can be penalized by journals and search engines [3].

- Solution: Always first consult the target journal's guidelines, which typically specify a number between 3 and 8 [24]. Do not use words already present in your title [24]. For placement, integrate keywords strategically in high-visibility sections:

- Article Title: The most critical location for primary keywords.

- Abstract: Weave primary and secondary keywords naturally into the narrative.

- Keywords Field: The dedicated section in the manuscript submission system.

- First Paragraph of the Introduction: Reinforce the main topic early.

- Headings and Subheadings: Use to structure content and signal topic shifts [3] [25].

FAQ 4: What is the difference between keyword stuffing and natural keyword integration?

- Problem: A misunderstanding leads to awkward, repetitive text that harms readability and trust [3] [4].

- Solution: Keyword stuffing is the unnatural overuse of a term to manipulate search rank, resulting in text that is robotic and difficult to read [3]. Natural integration focuses on user intent and semantic richness, using synonyms and related terms to create a coherent and authoritative narrative [10] [4]. Search engines' AI-driven algorithms now prioritize user experience and topical authority over simple word frequency [26] [10].

- Protocol: After writing, read your abstract aloud. If it sounds forced or repetitive, revise it. Use a tool like Hemingway Editor to identify hard-to-read sentences often caused by forced keyword placement [4].

Experimental Protocols for Keyword Selection

This section provides a reproducible methodology for identifying and validating optimal scientific keywords.

Protocol A: Systematic Identification of Candidate Keywords

Objective: To generate a comprehensive long-list of potential keywords for a research paper. Materials: Research manuscript, access to key databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, journal-specific keyword tools). Workflow:

- Core Concept Extraction: List the 2-3 irreducible core concepts of your research (e.g., "non-small cell lung cancer," "EGFR mutation," "osimertinib resistance").

- Database Mining:

- Input your core concepts into PubMed's search bar and analyze the "Best Match" and "Most Recent" results for recurring terminology.

- Examine 3-5 recently published papers in your target journal on a similar topic. Analyze their keywords and title phrasing.

- Related Term Expansion:

- Use the "People also ask" and "Related searches" features in standard search engines to discover natural language queries [4].

- Brainstorm abbreviations, acronyms, and common synonyms for each core concept.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this systematic process:

Protocol B: Evaluation and Refinement Using the R-S-U Framework

Objective: To filter the candidate long-list into a final, high-value set of keywords. Materials: Candidate keyword long-list from Protocol A. Framework: Evaluate each candidate term against three criteria [24]:

- Relevance: Does the keyword accurately and directly describe the focus of the paper? View your work from a reader's perspective.

- Specificity: Is the keyword sufficiently precise? Avoid overly broad terms (e.g., "cancer") in favor of specific ones (e.g., "metastatic colorectal cancer").

- Uniqueness: Does the keyword help your paper stand out? Consider including a specific technique, model, or unique compound combination.

The refinement process is a sequential filter, visualized below:

A modern researcher's toolkit includes both conceptual frameworks and digital tools to aid keyword strategy. The following table details essential "research reagent solutions" for keyword optimization.

Table 1: Essential Tools for Scientific Keyword Strategy

| Tool Category & Name | Primary Function | Application in Scientific Publishing |

|---|---|---|

| Keyword Ideation & Validation | ||

| PubMed / Google Scholar [24] | Identify terminology used in high-impact literature. | Discover standard and emerging terms in your field by analyzing abstracts and titles of recent papers. |

| Journal Author Guidelines [24] | Provides mandatory rules for keyword number and format. | Ensure compliance and avoid immediate desk rejection by adhering to specific journal requirements. |

| Semantic Analysis & Optimization | ||

| LowFruits / Semrush [3] [4] | Uncover long-tail keywords and cluster related terms. | Find specific keyword combinations that have high relevance but lower competition. |

| AnswerThePublic [3] [4] | Generates questions related to a seed keyword. | Identify the common questions your research answers, allowing you to integrate this language. |

| Quality Assurance & Readability | ||

| Hemingway Editor [4] | Highlights complex sentences and passive voice. | Ensures keyword integration does not compromise the clarity and readability of your abstract and introduction. |

| Yoast SEO Readability Analysis [4] | Analyzes sentence length and transition words. | Provides a score to help keep your writing accessible, which is a positive signal for modern AI search systems [26]. |

Advanced Techniques: Optimizing for the AI-Driven Search Paradigm

The search landscape is evolving with the global rollout of AI-driven tools like Google's "AI Mode" and "Deep Search," which prioritize semantic understanding and authority [26]. To ensure your research remains visible, you must adopt next-generation practices.

Focus on User Intent and Topical Clusters: Move beyond isolated keywords. Create content that comprehensively covers a topic by building keyword clusters [3]. For a paper on "CAR-T cell therapy," create a cluster including "cytokine release syndrome," "lymphodepletion," "CD19 antigen," and "tumor microenvironment." This demonstrates topical authority to AI systems [3] [10].

Embrace Structured Data and E-E-A-T: AI Overviews and Deep Search heavily favor well-structured, authoritative content. Use clear headings (H2, H3) and bullet points to make your content machine-parsable [10]. Furthermore, explicitly demonstrate E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness) by citing authoritative sources, detailing methodologies, and providing robust author bios with ORCID IDs [26]. This signals to AI that your work is a credible source for synthesis and citation.

The logical relationship between traditional practices and advanced AI-ready techniques is summarized below:

Scientist's Guide to Keyword-Optimized Technical Content

Troubleshooting Common Drug Discovery Assays

Q: My TR-FRET assay shows no signal. What could be wrong? A: The most common reason is incorrect instrument setup, particularly improper emission filter selection. Unlike other fluorescent assays, TR-FRET requires exact filter specifications. Test your microplate reader's TR-FRET setup using existing reagents before beginning experimental work. Ensure you're using the recommended excitation and emission filters specific to your instrument model [27].

Q: Why am I getting different EC50 values between laboratories using the same compound? A: Differences typically originate from variations in stock solution preparation, usually at 1 mM concentrations. Other factors include compound inability to cross cell membranes, cellular export mechanisms, or the compound targeting inactive kinase forms rather than active forms required for activity assays [27].

Q: How should I analyze TR-FRET assay data? A: Calculate an emission ratio by dividing acceptor signal by donor signal (520nm/495nm for Terbium; 665nm/615nm for Europium). This ratiometric approach accounts for pipetting variances and reagent lot-to-lot variability since the donor serves as an internal reference. Ratio values typically appear small (often less than 1.0) because donor counts significantly exceed acceptor counts in TR-FRET [27].

Q: What defines a successful assay window? A: Assess your assay window by dividing the ratio at the top of your curve by the ratio at the bottom. For robust screening, calculate the Z'-factor, which considers both window size and data variability. Assays with Z'-factor >0.5 are suitable for screening. A large window with substantial noise may perform worse than a smaller window with minimal variability [27].

Q: My Z'-LYTE assay shows no window. How do I troubleshoot? A: Determine whether the issue stems from instrument setup or the development reaction by testing controls: preserve 100% phosphopeptide from development reagents (should give lowest ratio) and over-develop substrate with 10-fold higher development reagent (should give highest ratio). Properly developed reactions typically show a 10-fold ratio difference between these controls [27].

WCAG Color Contrast Requirements for Scientific Visualizations

Quantitative Contrast Thresholds

| Text Type | Minimum Ratio (AA) | Enhanced Ratio (AAA) | Font Size Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard text | 4.5:1 | 7:1 | Less than 18pt/24px |

| Large text | 3:1 | 4.5:1 | At least 18pt/24px or 14pt/19px bold |

| Incidental text | No requirement | No requirement | Part of inactive UI, decoration, or not visible |

| Logotypes | No requirement | No requirement | Brand names or logos |

Text must maintain these contrast ratios between foreground and background colors. For graphical elements like charts and diagrams, ensure sufficient contrast between data series and backgrounds. Incidental elements like disabled components or pure decoration are exempt [28] [29] [30].

Accessible Diagram Specification for Scientific Publishing

Assay Troubleshooting Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Drug Discovery

| Reagent Type | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TR-FRET Donors (Tb, Eu) | Energy donors in time-resolved FRET | Requires specific emission filters; serves as internal reference in ratiometric analysis |

| Kinase Substrates | Phosphorylation targets for activity measurement | Must use active kinase forms; binding assays can study inactive forms |

| Development Reagents | Cleave specific peptide substrates | Quality control includes full titration; concentration critical for assay window |

| Z'-LYTE Components | Fluorescent peptide substrates for kinase profiling | Contains 100% phosphopeptide controls and development enzymes |

| Compound Stocks | Small molecule solutions for screening | Typically prepared at 1mM; source of inter-lab variability in EC50 |

Keyword Optimization Framework for Scientific Content

Strategic Keyword Implementation

| Practice | Problematic Approach | Recommended Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Keyword Density | Stuffing keywords in lists or irrelevant contexts | Natural integration with 1-2% density; focus on semantic relevance |

| Terminology | Repeating identical phrases unnaturally | Incorporate synonyms and related terms; use long-tail keyword variations |

| Content Structure | Forcing keywords into every heading | Strategic placement in title, first paragraph, and selective subheadings |

| User Focus | Writing for algorithms over readers | Prioritize comprehensive topic coverage and genuine user value |

| Keyword Research | Targeting only high-volume generic terms | Focus on long-tail phrases, search intent, and question-based queries |

Modern AI systems can detect keyword manipulation through natural language pattern analysis, content quality assessment, and semantic context evaluation. Google's algorithms penalize keyword-stuffed content with ranking reductions or manual penalties, as it provides poor user experience and damages credibility [3] [22].

Create content that addresses researcher questions thoroughly and conversationally, using terminology that supports rather than dominates the scientific narrative. Comprehensive topic coverage naturally incorporates relevant terms without forced optimization [22].

Q1: My abstract keeps getting rejected for being "unstructured" or "lacking key elements." What is the essential structure I must follow?

A: A properly structured abstract must function as a standalone summary of your entire paper. Adhere to this formal structure, typically within a 200-250 word count [31] [32]:

- Background (1-2 sentences): Briefly state the problem or knowledge gap that your research addresses [31].

- Aim/Objective (1 sentence): Clearly articulate the specific goal of your study [32].

- Methods (2-3 sentences): Concisely describe your experimental approach, including key techniques, materials, or data sources [31].

- Results (2-3 sentences): Present your most significant findings, including key quantitative data where appropriate [31].

- Conclusions (1-2 sentences): State the primary take-home message and its implications for your field [31].

Q2: How can I integrate keywords for discoverability without being penalized for "keyword stuffing"?

A: Keyword stuffing, or the excessive repetition of terms, is penalized by modern search algorithms and undermines readability [4] [33]. To optimize naturally:

- Focus on User Intent: Ensure your content answers the questions your target audience is asking [4] [34].

- Use Natural Integration: Write in a conversational tone, using synonyms and related terms that fit the context smoothly [4].

- Strategic Placement: Incorporate the most common and important key terms at the beginning of your abstract and in the title, as some search engines may not display the full text [1].

- Leverage Long-Tail Keywords: Use specific, multi-word phrases (e.g., "CRISPR gene editing in oncology") that are less competitive and often have higher conversion rates [34].

Q3: What are the most common mistakes that lead to a weak abstract?

A: Avoid these frequent errors to enhance your abstract's quality:

- Exceeding Word Limits: Strictly adhere to the journal's word count, usually 250 words or less [1] [35].

- Unnecessary Content: Do not include citations, acronyms (unless defined), or references to figures and tables within the abstract [31] [32].

- Vague Results: Avoid statements like "results were significant." Instead, provide specific data (e.g., "Response rates were 49% vs 30%, respectively; P<0.01") [31].

- Redundant Keywords: Using keywords that already appear in the title or abstract is a common practice that undermines optimal indexing [1].

- Inflated Claims: Ensure your conclusions are scrupulously honest and do not claim more than your data demonstrates [31].

The following data, synthesized from a survey of journals in ecology and evolutionary biology, highlights common practices and issues in abstract writing [1].

Table 1: Analysis of Abstract and Keyword Practices in Scientific Publishing

| Metric | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Abstract Word Exhaustion | Authors frequently exhaust word limits, particularly those capped under 250 words [1] | Suggests current guidelines may be overly restrictive, limiting the dissemination of key findings. |

| Redundant Keyword Usage | 92% of studies used keywords that were already present in the title or abstract [1] | This redundancy undermines optimal indexing in databases and reduces discoverability. |

| Keyword Type Effectiveness | Papers whose abstracts contain more common, frequently used terms tend to have increased citation rates [1] | Emphasizing recognizable key terms significantly augments the findability and impact of an article. |

| Negative Impact of Uncommon Keywords | Using uncommon keywords is negatively correlated with scientific impact [1] | Precise and familiar terms (e.g., "survival" vs. "survivorship") outperform less recognizable counterparts. |

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for crafting a high-impact abstract with integrated, non-stuffed keywords.

Objective: To develop a structured abstract that accurately summarizes research and enhances discoverability through strategic keyword use.

Workflow Overview: The diagram below outlines the core experimental workflow for creating your abstract.

Procedure:

- Write the Abstract Last: Complete the entire manuscript before drafting the abstract to ensure it accurately represents the paper's content [32].

- Identify Core Concepts: Reread your paper and extract the central ideas from each section: purpose, methodology, key results, and conclusions [32].

- Extract Key Findings: Identify the 2-3 most critical results, prioritizing those with quantitative data and the greatest significance to your field [31].

- Draft Abstract Sections: Compose the abstract using the structured format (Background, Aim, Methods, Results, Conclusions) without looking at the original paper to avoid simply copying sentences [32].

- Perform Keyword Audit:

- Tool-Assisted Check: Use SEO or readability tools (e.g., Yoast SEO, Hemingway Editor) to flag potential overuse of specific terms [4].

- Natural Language Review: Read the abstract aloud to ensure the language is fluid and conversational. Would you use the same phrase repeatedly in a conversation with a colleague? If so, revise [4].

- Strategic Placement: Verify that your most important key terms appear early in the abstract and are present in the title where appropriate [1].

- Revise and Refine: Edit your draft by correcting organization, improving transitions, and dropping unnecessary information. Replace overused terms with semantic variations and long-tail keywords [4] [32].

- Final Quality Check: Ensure the abstract is self-contained, adds no new information, and is understandable to a wide academic audience within the word limit [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Digital Tools for Abstract Preparation and Optimization

| Tool / Resource | Function | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Google Scholar | Literature Database | Scrutinize similar studies to identify predominant terminology and common key terms in your field [1]. |

| Google Trends | Search Trend Analysis | Identify key terms that are more frequently searched online, helping to gauge commonality [1]. |

| Readability Analyzers (e.g., Hemingway Editor) | Writing Quality Control | Highlights repeated words, complex sentences, and awkward phrasing to ensure natural, readable language [4]. |

| SEO Suites (e.g., Semrush, Ahrefs) | Content Optimization | Perform on-page SEO audits to spot potential overuse of keywords and suggest semantic variations [4] [36]. |

| Thesaurus | Lexical Resource | Provides variations of essential terms to ensure a variety of relevant search terms can direct readers to your work [1]. |

The practice of keyword stuffing—densely packing content with repetitive, exact-match terms—is an outdated and ineffective SEO strategy that is particularly detrimental in scientific publishing [37]. Modern search engines, powered by advanced artificial intelligence, now prioritize understanding user intent and the contextual meaning of content over simple keyword matching [37]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this evolution necessitates a shift towards Semantic SEO, a strategy that uses synonyms, related concepts, and long-tail keyword variants to align content with the sophisticated search behaviors of a scientific audience. This approach not only enhances organic visibility but also ensures that your troubleshooting guides and FAQs are discoverable by the right experts at their precise point of need, all while maintaining the integrity and natural flow of scientific language.

The following table outlines the core problems with the old keyword-centric approach versus the modern semantic solution:

| Traditional Keyword Stuffing Pitfalls | Modern Semantic SEO Solutions |

|---|---|

| Creates awkward, unnatural content [37] | Prioritizes writing for humans first [37] |

| Fails to match user intent [37] | Focuses on answering complete questions [37] |

| Targets isolated, generic keywords [37] | Builds topic clusters and covers broader subjects [37] |

| Ineffective for voice and conversational search [38] | Optimizes for natural language queries [39] |

Core Concepts: Synonyms and Long-Tail Keywords

The Role of Synonyms in Semantic SEO

Synonyms are the cornerstone of Semantic SEO. Instead of repeating a single term like "quantitative PCR," you incorporate related terms and phrases such as "qPCR protocol," "real-time PCR optimization," or "cycle threshold analysis." This practice, often called Entity SEO or Semantic SEO, signals to search engines that your content provides a comprehensive treatment of the topic [40]. It captures the varied vocabulary used by different researchers—for instance, some may search for "mass spectrometry" while others use "MS analysis" or "mass spec data." By using this natural diversity of language, your content answers more search queries and sounds more authentic to your expert audience.

The Power of Long-Tail Keywords

Long-tail keywords are longer, more specific keyword phrases that visitors are more likely to use when they're closer to a point of decision or using voice search [40]. For example, while a broad head term might be "cell culture," a long-tail variant could be "optimizing HEK293 cell culture media for transient transfection" [38].

These keywords are crucial for scientific content for several reasons, which are summarized in the table below alongside their specific benefits for a technical support center:

| Characteristic of Long-Tail Keywords | Benefit for Scientific SEO | Application in Troubleshooting Guides |

|---|---|---|

| Lower search volume, but higher intent [40] [38] | Attracts highly qualified traffic that is closer to conversion or finding a solution [40] [38]. | A user searching for a specific error code is likely experiencing that issue and needs an immediate fix. |

| Less competition [40] [38] | Easier to achieve a first-page ranking, even for newer websites [40]. | Allows your specific guide to rank quickly without competing with millions of generic results. |

| Reflect natural language and voice search [40] [39] | Captures the growing trend of researchers using conversational queries and voice assistants [40]. | Answers full questions like "Why is my flow cytometry showing high background noise?" |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Semantic SEO for a Technical Support Center

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for developing and optimizing technical support content using Semantic SEO principles.

Phase I: Keyword Research and Strategy Formulation

Objective: To identify the core head terms, semantic synonyms, and target long-tail keywords that will form the foundation of your content strategy.

- Step 1: Identify Core Troubleshooting Concepts. Brainstorm a list of primary techniques, instruments, and reagents relevant to your audience (e.g., "ELISA," "flow cytometer," "PCR master mix").

- Step 2: Mine for Synonyms and Related Terminology.

- Tools: Analyze relevant scientific databases like PubMed and Google Scholar to identify terminology from abstracts and titles of highly-cited papers [41] [39]. Use PubMed's MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) to find standardized terminology [41].

- Method: For each core concept, list synonyms (e.g., "Immunohistochemistry" and "IHC"), acronyms, and related techniques (e.g., for "Western Blot," list "protein immunoblotting," "SDS-PAGE").

- Step 3: Discover Long-Tail Keyword Variations.

- Tools: Use your Google Search Console performance report to find long-tail queries already driving impressions to your site [40]. Use "People also ask" boxes on Google and analyze forums like Reddit or ResearchGate where scientists describe problems in detail [40].

- Method: Formulate specific questions. Transform a core concept like "qPCR amplification" into long-tail questions: "Why is my qPCR amplification efficiency low?", "How to fix high Cq values in qPCR?", "qPCR melt curve shows multiple peaks troubleshooting."

Phase II: Content Optimization and On-Page Implementation

Objective: To strategically integrate the researched keywords into your support content without compromising quality or readability.

- Step 1: Optimize the Title Tag and H1 Heading. Include the primary long-tail question verbatim. For example, the H1 for a guide should be "How to Fix High Background Noise in Flow Cytometry Data" rather than just "Flow Cytometry Troubleshooting."

- Step 2: Structure Content with Hierarchical Headings (H2, H3, etc.). Use headings to break down the problem and solution. Incorporate synonyms and related terms into these subheadings (e.g., an H2 could be "Optimizing Antibody Titration to Reduce Signal Noise").

- Step 3: Write Comprehensive, Natural Answer Content.

- Method: Answer the question thoroughly. Use the full range of identified synonyms and related terms naturally throughout the explanation. For instance, in a guide about "cell viability assay," you might also mention "cytotoxicity," "apoptosis detection," and "metabolic activity measurement" as relevant.

- Avoidance of Keyword Stuffing: The content must read as if written by a scientist for a scientist. Prioritize clarity and accuracy over forced keyword inclusion [37].

Phase III: Technical Implementation and Site Architecture

Objective: To ensure the technical structure of your support center maximizes content discoverability.

- Step 1: Implement FAQ Schema Markup. Use JSON-LD to mark up your question-and-answer content with FAQPage schema. This makes your content eligible for rich results in search, often displaying your Q&A directly in the search results [39].

- Step 2: Create a Topic-Cluster Architecture.

- Method: Instead of a siloed support section, interlink related content. Create a "pillar" page on a broad topic (e.g., "PCR Troubleshooting Guide") and link it to more specific "cluster" pages (e.g., "qPCR Amplification Issues," "Primer-Dimer Formation," "RT-PCR Contamination Problems") [37]. This tells search engines your site is a comprehensive authority on the subject.

The following workflow diagram visualizes the key stages of this experimental protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Experiment

The following table details key reagents and materials used in a common cell biology experiment, such as optimizing a transfection protocol, which is a frequent subject of troubleshooting guides.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation in Experiment |

|---|---|

| HEK293 Cell Line | A robust, fast-growing human embryonic kidney cell line widely used for transient protein expression due to its high transfection efficiency. |

| Plasmid DNA (e.g., pEGFP-N1) | A vector containing the gene of interest (e.g., Green Fluorescent Protein) used to transfer genetic material into the host cells to study protein expression. |

| Lipid-Based Transfection Reagent | Forms liposomes that complex with nucleic acids, facilitating their passage through the cell membrane via endocytosis. |

| Opti-MEM Reduced-Serum Medium | A low-serum medium used during the transfection complex formation and incubation to reduce serum interference and increase transfection efficiency. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Provides essential growth factors, hormones, and lipids for cell growth and health. Used in full growth media before and after the transfection procedure. |

| Antibiotics (e.g., Penicillin-Streptomycin) | Added to cell culture media to prevent bacterial contamination, which is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the experiment over several days. |

| Trypsin-EDTA Solution | A proteolytic enzyme used to detach adherent cells from the culture vessel for subculturing or harvesting post-transfection. |

Data Presentation: Quantitative Impact of Long-Tail Keywords

The strategic value of long-tail keywords is demonstrated by their collective search volume and superior performance metrics compared to head terms. The following tables synthesize quantitative data on this impact.

Table 5.1: Search Volume and Competition Analysis

| Keyword Type | Example | Typical Monthly Search Volume | Ranking Competition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head Term | "CRISPR" | Very High (e.g., 100k+) | Extremely High [40] [38] |

| Supporting Long-Tail | "CRISPR Cas9 applications" | Moderate | Medium-High [38] |

| Topical Long-Tail | "CRISPR off-target effects mitigation" | Low | Low [38] |

Table 5.2: Performance and User Intent Metrics

| Keyword Type | Typical Conversion Rate | Searcher Intent Clarity |

|---|---|---|

| Head Term | Lower | Unclear / Informational [38] |

| Supporting Long-Tail | Moderate | More Specific |

| Topical Long-Tail | Higher | Very Clear / Transactional [40] [38] |

Note: Conversion in a scientific context may refer to downloading a protocol, submitting a support ticket, or accessing a specific technical guide.

Effective Use of Headings (H2, H3) to Signal Content Structure

In scientific publishing, the clear communication of complex information is paramount. Effective use of headings (H2, H3) serves as the structural framework for your documentation, guiding readers through your troubleshooting guides and FAQs with logical precision. This structured approach directly supports the core thesis of avoiding keyword stuffing; by focusing on a clear, hierarchical organization of ideas, you naturally integrate relevant terminology without forced repetition, aligning with modern search algorithms that prioritize context and user intent over mere keyword density [22] [12]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this clarity is not just a convenience—it is a necessity for the accurate and efficient transfer of knowledge.

The Core Principles of Heading Hierarchy

A well-defined heading structure creates a roadmap for your readers, making complex technical documentation scannable and accessible.

Understanding Heading Ranks (H1 to H6)

Headings are defined by their rank, from <h1> (the most important) to <h6> (the least important) [42]. This hierarchy creates a logical flow of information:

- The H1 Tag defines the primary heading on a webpage, equivalent to the main title of a document. It should describe the overall topic and, for the purpose of this structure, you should generally use only one H1 per page [43].

- The H2 Tag defines second-level headings and is used for your main points or sections, effectively breaking your content into digestible chunks [43].

- The H3 Tag defines third-level headings and is used for sub-points that exist under your H2 sections, allowing for further organization of detailed information [43].

The Critical Rule: Maintaining a Logical Hierarchy

The most important rule for headings is to nest them by their rank without skipping levels [42]. An H2 should start a new section, and any H3s should be subsections within that H2. Avoid jumping directly from an H2 to an H4, as this creates a confusing experience for all users.

Best Practices for Structuring Technical Content

Applying technical writing principles to your heading structure enhances clarity and user comprehension.

Organizing Content for Maximum Impact

Your documentation should progress logically from foundational concepts to more advanced ones [44]. Each section should build upon the information presented previously, avoiding abrupt jumps. Before writing, spend time planning the desired structure, ensuring each subsection incrementally contributes to the overall goal of the document [44].

Ensuring Clarity and Conciseness

- Use Simple, Clear Language: Choose simple words and clear language, keeping in mind an audience that may include non-native English speakers [44].

- Aim for One Idea Per Paragraph: Each sentence in a paragraph should logically connect to the one before it, forming a continuous sequence around a single main idea [44].

Optimizing Document Structure and Length

Evaluate your documentation's structure to ensure a logical and balanced hierarchy [44]:

- Avoid "Orphans": If a main section (e.g., an H2) contains only one subsection (a single H3), this indicates a need to reorganize or add content.

- Limit Deep Nesting: Using too many subsections (e.g., many H4s) can be overwhelming. Consider using bulleted lists instead to present key points more effectively.

- Split Large Sections: If a section becomes too extensive, split it into multiple logical subsections to maintain focus and improve navigation.

Integrating Keywords Without Stuffing: An Anti-Spamming Methodology

Modern search engines, powered by AI, understand context and user intent, making keyword stuffing an obsolete and penalized practice [22] [12]. The following workflow provides a methodological approach to integrating keywords naturally within a well-structured document.

Experimental Protocol: Strategic Keyword Integration

This protocol ensures keywords support content structure and user clarity without manipulation.

Objective: To strategically integrate focus keywords into a technical document to signal relevance to search engines while maintaining natural, readable prose for a scientific audience and avoiding keyword stuffing penalties.

Materials: The Scientist's Toolkit for Content Optimization (See Section 4.3).

Methodology:

- Keyword Definition: Identify one primary keyword and 2-4 secondary keywords (including long-tail variations and synonyms) that reflect the core topic and user search intent [22].