Beyond Guesswork: A Scientific Framework for Keyword Recommendation in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to data-driven keyword recommendation methods for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Beyond Guesswork: A Scientific Framework for Keyword Recommendation in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to data-driven keyword recommendation methods for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It bridges the gap between traditional SEO practices and the unique demands of scientific communication. The content covers foundational principles, practical methodologies for application, strategies for optimization, and rigorous validation techniques. By adopting these structured approaches, scientific professionals can enhance the discoverability, impact, and integrity of their research in an era dominated by big data analytics and AI-driven search.

Why Keywords Are the New Building Blocks of Scientific Discovery

FAQs: Keyword Recommendation in Scientific Research

Q1: What is the difference between traditional and modern AI-powered keyword research methods? Traditional methods relied on exact-match keywords and volume-based targeting, which often failed to capture user intent and contextual meaning [1]. Modern, AI-powered approaches use natural language processing (NLP) and Large Language Models (LLMs) to understand semantic intent and context [1] [2]. This shift allows for the automatic generation of relevant keywords from text and the identification of thematic communities within a research field, moving beyond simple word matching to a deeper understanding of content [3] [2].

Q2: How can I generate relevant keywords for a new scientific research paper? A robust, automated methodology involves a systematic, three-step process leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) [2]:

- Input Preparation: Feed the article's title and abstract into an LLM using specifically engineered prompts designed to elicit keyword generation.

- Keyword Generation: The LLM produces a list of potential keywords based on the contextual understanding of your text.

- Semantic Grouping: Compute representation vectors for the generated keywords and group them based on vector similarity to identify core thematic clusters and remove redundancies [2]. Evaluation of this method shows that the choice of LLM (e.g., Mistral) and careful prompt engineering significantly impact the quality and accuracy of the results [2].

Q3: My literature search returns too many irrelevant papers. How can keyword analysis help? Traditional keyword-based searches can be inaccurate because they may miss relevant papers that do not use your exact search terms [4]. A more effective strategy is co-word analysis [3]. This involves:

- Building a keyword co-occurrence network, where words that frequently appear together in article titles are linked [3].

- Using community detection algorithms, like the Louvain modularity algorithm, to segment this network into distinct research communities [3].

- This visually and structurally reveals the main sub-fields within a broader research area, allowing you to focus your literature review on the most relevant community of keywords and their associated papers [3].

Q4: What are the best practices for visualizing keyword network data? Effective data visualization is key to communicating insights from keyword analysis. Follow these core principles [5] [6] [7]:

- Choose the Right Chart: For network relationships, node-link diagrams are standard. For comparing keyword frequency across categories, use bar charts [6].

- Use Color Strategically: Apply color to highlight different keyword communities or to show value intensity. Ensure sufficient color contrast and use accessible palettes to accommodate color vision deficiencies [6].

- Maximize Data-Ink Ratio: Remove unnecessary chart elements like heavy gridlines, 3D effects, and decorative backgrounds to reduce cognitive load and focus attention on the data itself [6].

- Provide Clear Context: Use comprehensive titles, axis labels, and annotations to make the visualization self-explanatory [6].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Keyword-Based Research Trend Analysis

This methodology details how to structurally analyze a research field using keywords extracted from scientific papers [3].

1. Article Collection

- Action: Collect bibliographic data from APIs of scholarly databases (e.g., Crossref, Web of Science) using targeted queries based on device names, mechanisms, or core concepts of the field [3].

- Filtering: Filter document types to include only research papers. Define a relevant publication year range and remove duplicates by comparing article titles [3].

2. Keyword Extraction

- Tool: Utilize an NLP pipeline (e.g., spaCy's

en_core_web_trf, a RoBERTa-based model) for processing [3]. - Process: Tokenize the titles of all collected articles. Then, apply lemmatization to convert tokens to their base form. Use part-of-speech tagging to retain only adjectives, nouns, pronouns, and verbs as candidate keywords [3].

3. Research Structuring

- Network Construction: For each article title, create all possible keyword pairs. Aggregate pairs across all titles to build a co-occurrence matrix. Transform this matrix into a keyword network in a tool like Gephi, where nodes are keywords and edges represent co-occurrence frequency [3].

- Modularization: To simplify the network, select the top representative keywords (e.g., those accounting for 80% of total word frequency using PageRank scores). Apply a community detection algorithm like Louvain modularity to identify distinct keyword communities [3].

Protocol 2: Automated Keyword Generation Using LLMs

This protocol describes a systematic approach for generating keywords for a research article using Large Language Models [2].

1. Data Preparation and Prompt Engineering

- Inputs: Use the title and abstract of the research article as the primary text inputs [2].

- Prompt Strategy: Employ three different, domain-agnostic prompts to instruct the LLM to generate keywords. Using multiple prompts helps ensure a diverse and contextually relevant set of keywords is produced [2].

2. Model Inference and Semantic Grouping

- Generation: Run the prepared prompts through a selected LLM (e.g., Mistral) to obtain a raw list of candidate keywords [2].

- Vectorization and Clustering: Compute representation vectors (embeddings) for each generated keyword. Then, group these keywords based on the similarity of their vectors to identify semantic clusters and reduce redundancy, resulting in a refined, organized final list [2].

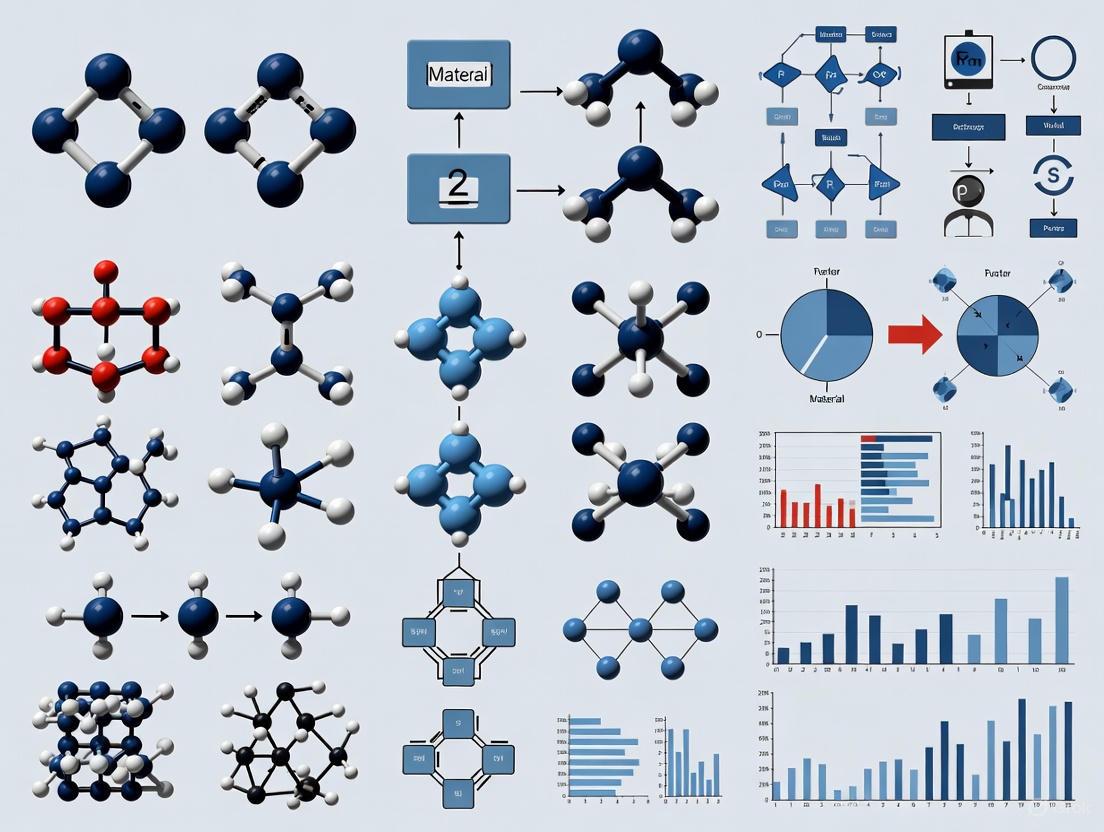

The following workflow diagram illustrates the two primary experimental protocols for keyword analysis and generation:

The table below consolidates key quantitative findings from the referenced experiments on keyword analysis and generation:

| Experiment Focus | Key Metric | Result / Value | Context / Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Trend Analysis [3] | Articles Collected | 12,025 | ReRAM research field, collected via API search [3]. |

| Keywords Extracted | 6,763 | From article titles using NLP pipeline [3]. | |

| Representative Keywords | 516 (Top 80%) | Selected via weighted PageRank score for network analysis [3]. | |

| Keyword Generation with LLMs [2] | Best Performing Model | Mistral | Within a 3-prompt framework for keyword generation [2]. |

| Critical Success Factors | Prompt Engineering & Semantic Grouping | Significant impact on keyword generation accuracy [2]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key software tools and methodologies essential for implementing advanced keyword recommendation methods.

| Tool / Method Name | Primary Function | Application in Keyword Research |

|---|---|---|

| NLP Pipeline (e.g., spaCy) [3] | Natural Language Processing | Tokenizes and lemmatizes text from titles and abstracts to extract candidate keywords [3]. |

| Network Analysis Tool (e.g., Gephi) [3] | Network Visualization & Analysis | Constructs and visualizes keyword co-occurrence networks to identify research communities [3]. |

| Louvain Modularity Algorithm [3] | Community Detection | Segments a keyword network into distinct, thematic clusters (communities) to map research structure [3]. |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) [2] | Text Generation & Understanding | Automates the generation of contextually relevant keywords from a paper's title and abstract [2]. |

| Semantic Vector Grouping [2] | Dimensionality Reduction & Clustering | Groups LLM-generated keywords based on vector similarity to refine lists and identify core themes [2]. |

This final diagram provides a unified view of how the various tools and protocols integrate into a complete keyword analysis system, from data input to final insight.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on the PSPP Framework

FAQ 1: What is the core principle of the PSPP relationship in materials science? The core principle of the Processing-Structure-Property-Performance (PSPP) relationship is that it provides a fundamental framework for understanding and designing materials. It explains that the processing techniques applied to a material dictate its internal structure (from atomic to macro-scale). This structure, in turn, determines the material's properties, which ultimately define its performance in real-world applications [8] [9]. This reciprocity is crucial for developing new materials, as it allows researchers to trace the effect of a change in a process parameter through to the final product's performance.

FAQ 2: My experiments are yielding inconsistent material properties. Where in the PSPP chain should I start troubleshooting? Inconsistent properties often stem from variations in the Processing-to-Structure (P-S) relationship. You should first investigate your processing parameters for stability and repeatability. For instance, in additive manufacturing, small fluctuations in laser power or scan speed can lead to significant changes in the melt pool geometry, causing defects like porosity or lack-of-fusion that adversely affect the microstructure and final properties [10]. Implementing data-driven process monitoring can help establish a more robust link between your process parameters and the resulting structure.

FAQ 3: How can I identify new keywords for a literature search on PSPP relationships for a specific material? To identify relevant keywords, deconstruct the PSPP framework for your material:

- Processing: Include specific techniques (e.g., "laser powder bed fusion," "hot-pressing," "solvent casting") and key parameters (e.g., "scan speed," "annealing temperature").

- Structure: Target microstructural features (e.g., "grain size," "phase distribution," "porosity," "cell structure").

- Property: List the mechanical, thermal, or functional properties of interest (e.g., "yield strength," "degradation rate," "magnetic responsiveness").

- Performance: Define the application context (e.g., "biomedical implant," "cargo transportation," "pollutant removal") [8] [11]. Using these terms in combination will map the research landscape effectively.

FAQ 4: What is a PSPP map or design chart and how is it used? A PSPP design chart is a knowledge graph that visually represents the PSPP relationships for a material system [9] [12]. Factors are classified as Process, Structure, or Property and represented as nodes. The connections between these nodes represent influential relationships—for example, an "annealing" process node connected to a "grain size" structure node, which is then connected to a "strength" property node [9]. This chart intuitively summarizes end-to-end knowledge, shows the effect of processes on properties, and suggests prospective processes to achieve desired properties.

FAQ 5: Can machine learning effectively model PSPP relationships, and what are the data requirements? Yes, machine learning (ML) is increasingly used to model the complex, non-linear PSPP relationships that are difficult to capture with physics-based models alone. For example, Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) has been successfully applied to predict molten pool geometry from process parameters and to forecast mechanical properties like ultimate tensile strength from microstructural data [10] [13]. The primary requirement is a high-quality, well-curated dataset. The main challenges include the large, high-dimensional data space of process parameters and the cost of generating reliable experimental data for training [10].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental PSPP Challenges

The table below outlines common experimental issues within the PSPP framework, their likely causes, and recommended investigative actions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for PSPP Experiments

| Problem Observed | Associated PSPP Link | Potential Root Cause | Corrective Action & Investigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent final performance (e.g., premature failure) | Property-Performance | Property metrics not adequately capturing real-world operating conditions. | Review property testing protocols. Perform failure analysis to link performance failure to a specific property deficit. |

| High variability in measured properties (e.g., strength, degradation rate) | Structure-Property | Inconsistent microstructure or defects (e.g., porosity, variable grain size) [10] [11]. | Characterize the structure (SEM, microscopy) to identify defects. Standardize and tightly control processing parameters. |

| Failure to achieve target structure | Processing-Structure | Unstable or inappropriate processing parameters (e.g., temperature, energy input) [8] [10]. | Use in-situ monitoring (e.g., thermal imaging) to verify process stability. Explore a wider design-of-experiments (DOE) window for parameters. |

| Inability to scale up a successful lab-scale material | All PSPP links | Changes in heat transfer, fluid dynamics, or kinetics at larger scales alter the P-S relationship. | Systematically map the PSPP relationship at pilot scale. Use data-driven surrogates to identify new optimal parameters for scale-up. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Constructing a PSPP Map

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for constructing a PSPP map for a material system, as demonstrated in research on stainless-steel alloys and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) biopolymers [12] [11].

Objective: To systematically gather, organize, and visualize the relationships between processing, structure, properties, and performance for a chosen material.

Materials & Equipment:

- Primary Literature: Access to scientific databases (e.g., Scopus, Web of Science).

- Data Extraction Tool: A spreadsheet application or dedicated data analysis software.

- Visualization Software: Software capable of generating network graphs or flowcharts (e.g., Graphviz, Gephi, yEd).

Methodology:

Define the Material System: Clearly specify the material or material class of interest (e.g., "AlSi10Mg fabricated by Laser Powder Bed Fusion" or "Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) biopolymers").

Literature Review and Data Extraction:

- Conduct a comprehensive literature search using keywords derived from the PSPP framework (see FAQ #3).

- Systematically extract and record the following information from each relevant publication:

- Processing (P) Factors: Specific parameters (e.g.,

Laser Power: 300 W,Scan Speed: 1000 mm/s,Annealing at 500°C for 1h). - Structure (S) Factors: Observed microstructural features (e.g.,

Average Grain Size: 50 µm,Porosity: <0.5%,Cellular Structure Present). - Property (P) Factors: Measured mechanical, physical, or chemical properties (e.g.,

Yield Strength: 250 MPa,Ultimate Tensile Strength: 320 MPa,Degradation Rate in Seawater: 0.1 mg/week). - Performance (P) Metrics: Application context and results (e.g.,

Fatigue Life: 10^6 cycles,Drug Release Efficiency: 85% over 24h,Microplastic Removal Efficiency: 95%).

- Processing (P) Factors: Specific parameters (e.g.,

Data Categorization and Node Creation:

- In your data sheet, categorize every extracted factor into one of the four PSPP stages.

- Each unique factor becomes a node in your future map. For example, "Laser Power," "Grain Size," and "Yield Strength" are all distinct nodes.

Relationship Identification and Edge Creation:

- Analyze the extracted data to identify cause-and-effect relationships between the nodes. These relationships are the edges (connections) in your map.

- A connection is made if a change in one factor is reported to influence another. For example:

Laser Power(Process) →Melt Pool Size(Structure) →Porosity(Structure) →Ultimate Tensile Strength(Property) [10].

Map Assembly and Visualization:

- Input the nodes and edges into your visualization software.

- Use a consistent layout: Process nodes on the left, flowing to Structure, then Property, and finally Performance nodes on the right.

- Use distinct colors or shapes for nodes from different PSPP stages to enhance readability.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for this protocol:

Key Research Reagent Solutions for PSPP Experiments

The table below lists essential materials and tools frequently used in experimental research involving PSPP relationships, particularly in fields like polymer composites and additive manufacturing.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PSPP Investigations

| Item Name | Function / Relevance in PSPP Research |

|---|---|

| Magnetic Fillers (e.g., NdFeB microflakes, Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles) | Serves as a functional filler in Magnetic Polymer Composites (MPCs). Its incorporation and distribution (Structure) directly determine the magnetic responsiveness (Property) of the robot or actuator [8]. |

| Polymer Matrices (e.g., Thermosets, Thermoplastics, PHA biopolymers) | Forms the bulk body of composite materials. The choice of polymer affects processability (Processing) and determines key properties like biodegradation rate (Property) and biocompatibility (Performance) [8] [11]. |

| Metal Alloy Powder (e.g., AlSi10Mg, Stainless Steel) | The primary feedstock in metal Additive Manufacturing. Powder characteristics (size, morphology) and process parameters (Processing) define the resulting microstructure and defects (Structure) [10] [13]. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) Model | A data-driven modeling tool used to establish predictive relationships between process parameters, structural features, and final properties, overcoming the cost of extensive trial-and-error experiments [13]. |

| In-situ Monitoring Tools (e.g., Thermal cameras, High-speed imaging) | Used to capture real-time data during processing (e.g., melt pool characteristics in AM). This links specific process parameters to transient structural formation [10]. |

Visualizing the PSPP Knowledge Extraction Workflow

Modern approaches use Natural Language Processing (NLP) and machine learning to automatically extract PSPP relationships from scientific literature. The following diagram outlines this workflow, which helps in building knowledge graphs and populating PSPP maps from textual data [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Low Recall in Systematic Reviews

Problem: Your systematic literature search is retrieving fewer relevant articles than expected.

Explanation: Low recall often stems from an overly narrow or inconsistent keyword strategy, missing relevant studies that use different terminology.

Investigation and Resolution:

Step 1: Analyze Keyword Comprehensiveness

- Compare your current keyword set against the MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) database and use the "MeSH on Demand" tool to identify potential omissions [14].

- Action: Generate a list of missed MeSH terms and synonyms related to your core concepts.

Step 2: Apply a Structured Keyword Technique

- Implement the Weightage Identified Network of Keywords (WINK) technique [14].

- Action: Use a tool like VOSviewer to create network visualizations of keyword interconnections. Systematically exclude keywords with limited networking strength to your core topics (Q1 and Q2). Build a new search string using the high-weightage keywords identified.

Step 3: Validate and Compare Results

- Execute the new search string and compare the number of eligible articles retrieved against your initial search.

- Action: Benchmark your results. Application of the WINK technique has been shown to yield 69.81% and 26.23% more articles for different research questions compared to conventional keyword approaches [14].

Guide 2: Addressing Inconsistencies in Trend Analysis Data

Problem: Your analysis of research trends using a public data source (e.g., Google Trends) yields inconsistent, non-reproducible results from day to day.

Explanation: Inconsistencies in trend data often arise from the sampling methods used by the data provider. The Search Volume Index (SVI) is a relative measure based on a sample of searches, and this sampling can cause wide variations in daily results [15].

Investigation and Resolution:

Step 1: Identify the Data Source's Limitations

- Recognize that single, un-averaged data extractions from sampled sources are inherently noisy [15].

- Action: Document the specific data source and its known methodology for generating metrics.

Step 2: Implement a Data Averaging Protocol

- To smooth out the noise introduced by sampling, run multiple extractions and average the results [15].

- Action: For a given time period and query, collect the SVI (or equivalent metric) through multiple independent queries. Use the average of these values for your analysis.

Step 3: Correlate Averaging with Search Popularity

- Understand that the required number of averaged extractions to achieve a consistent series is related to the popularity of the search term [15].

- Action: For less popular, niche research terms, plan to average a larger number of extractions to obtain a stable and consistent data series for reliable analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single biggest keyword-related mistake that compromises evidence synthesis?

A1: Relying solely on the intuition and unstructured suggestions of subject experts. While expert knowledge is invaluable, using it alone can introduce selection bias and overlook critical terminology. A hybrid approach that integrates expert insight with systematic, computational methods like the WINK technique significantly enhances search comprehensiveness and objectivity [14].

Q2: Our team uses different keyword sets for the same project, leading to inconsistent results. How can we standardize our approach?

A2: Implement a standardized, step-by-step protocol for keyword selection and search string building. This should include:

- Structured Methodology: Adopt a defined technique such as the 11-step sequential process for building reference lists, which moves from broad searches to precise exclusion [4].

- Network Analysis: Use tools like VOSviewer to visually analyze keyword strength and relationships before finalizing your list [14].

- Documentation: Maintain a shared log of all keywords considered, their MeSH equivalents, and the final Boolean search strings to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

Q3: How is AI changing the landscape of keyword research for scientific literature?

A3: AI is moving keyword research beyond simple term matching to a deeper understanding of semantic intent and context [1]. This is critical as search engines now prioritize user intent. AI-powered tools can:

- Automatically analyze vast amounts of data to identify semantic intent patterns and hidden keyword opportunities [1].

- Shift focus towards long-tail keywords that are more specific and have higher conversion rates in retrieving relevant studies [1].

- Help predict future research trends by identifying emerging correlations between concepts in the scientific literature [3].

Q4: What are the practical consequences of inconsistent online data used in research?

A4: Inconsistency in source data, such as variations in Google Trends SVI, directly undermines the reliability and reproducibility of your analysis. A model of this data-generating process shows that a single extraction can be a distorted representation of the underlying trend. Failing to account for this through proper averaging protocols can lead to flawed interpretations of research popularity or public interest over time [15].

Quantitative Data on Keyword Selection Impact

Table 1: Comparative Article Retrieval from Conventional vs. WINK Method [14]

| Research Question (Q) | Search Strategy | Number of Articles Retrieved | Percentage Increase with WINK |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1: Environmental pollutants & endocrine function | Conventional | 74 | +69.81% |

| WINK Technique | 106 | ||

| Q2: Oral & systemic health relationship | Conventional | 197 | +26.23% |

| WINK Technique | 248 |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Recall: Symptoms and Solutions

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Tool/Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fewer results than expected | Over-reliance on expert terms; missing synonyms | MeSH Database; "MeSH on Demand" [14] | Expanded list of controlled vocabulary terms |

| Results feel irrelevant | Poor keyword interconnection; broad, ambiguous terms | VOSviewer network analysis [14] | A refined, high-weightage keyword list |

| Missing seminal papers | Lack of systematic search structure | 11-step sequential process for reference lists [4] | Comprehensive and methodologically sound literature review |

Experimental Protocol: Applying the WINK Technique

Objective: To systematically select and weight keywords for constructing a comprehensive search string for a systematic review or bibliometric analysis.

Materials:

- Computer with internet access

- PubMed/MEDLINE database access

- VOSviewer software (or similar network analysis tool)

- MeSH on Demand tool

Methodology:

- Initial Keyword Generation: Collaborate with subject experts to draft an initial set of keywords and MeSH terms for the research questions (Q1 and Q2).

- Preliminary Search: Execute a conventional search using these keywords with Boolean operators. Record the number of eligible articles retrieved. Restrict study types and publication years as required for your review [14].

- Computational Analysis: a. Use VOSviewer to generate a network visualization chart based on the initial keyword set and their co-occurrence in the scientific literature [14]. b. Analyze the network to identify keywords with strong interconnections (high weightage) and those with limited networking strength. c. Exclude the low-strength keywords to refine the list.

- Search String Construction: Build a new Boolean search string using the refined, high-weightage MeSH terms and keywords.

- Validation Search: Execute the new search string under the same constraints as the preliminary search.

- Performance Calculation: Compare the number of articles retrieved by the new string against the initial search to calculate the percentage increase in yield [14].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Digital Tools for Robust Keyword and Literature Research

| Tool Name | Function | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| MeSH Database | NLM's controlled vocabulary thesaurus | Provides standardized terms for precise indexing and retrieval of biomedical literature [14]. |

| VOSviewer | Software tool for constructing and visualizing bibliometric networks | Creates network maps of keyword co-occurrence to identify high-weightage terms for the WINK technique [14]. |

| Semrush | Advanced SEO and keyword research platform | Offers granular keyword data, competitive gap analysis, and content optimization for analyzing public and publication trends [16]. |

| Google Keyword Planner | Free tool for keyword ideas and search volume data | Primarily used for forecasting and understanding search popularity in public domains, informing dissemination strategies [16]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is a controlled vocabulary and why is it critical for scientific data retrieval?

A controlled vocabulary is a set of predetermined, standardized terms that describe specific concepts [17]. In scientific databases, subject specialists use these vocabularies to index citations, ensuring consistent tagging of concepts regardless of the terminology used by an author [17]. This is critical because it accounts for spelling variations, acronyms, and synonyms, dramatically enhancing the findability and precision of scientific data retrieval [17] [18].

2. How do 'long-tail' keywords differ from generic keywords in a research context?

Long-tail keywords are longer, more specific keyword phrases, typically made from three to five words or more [19] [20]. While they have lower individual search volume than short, generic keywords, they collectively represent a massive portion of all searches and are less competitive [19] [21]. In research, using a long-tail keyword like "sea surface temperature anomaly Pacific" is akin to a precise experimental probe, fetching highly targeted datasets. In contrast, a generic keyword like "ocean data" is a broad net, resulting in a deluge of less relevant information and higher competition for visibility [19].

3. My dataset is new and unique. Which keyword recommendation method is most robust when high-quality existing metadata is scarce?

When existing metadata is scarce or of poor quality, the direct method of keyword recommendation is more robust [22]. This method recommends keywords by analyzing the abstract text of your target dataset against the definition sentences provided for each term in a controlled vocabulary [22]. It does not rely on similar, pre-existing datasets and is therefore independent of their quality, making it ideal for pioneering research areas [22].

4. How is the rise of AI-powered search impacting the value of long-tail keywords?

AI-powered search is making long-tail keywords more valuable than ever. Search queries are becoming increasingly conversational and detailed, with the average word count in queries triggering AI Overviews growing significantly [20]. Furthermore, AI systems pull from a broader range of sources to build comprehensive answers, meaning websites and data repositories that optimize for specific, detailed long-tail phrases have an increased chance of being cited in these AI-generated responses [20].

Experimental Protocols for Keyword Recommendation

Protocol 1: Implementing the Direct Recommendation Method

This protocol is for annotating a new scientific dataset with keywords from a controlled vocabulary (e.g., GCMD Science Keywords, MeSH) when a high-quality abstract is available [22].

- Objective: To accurately annotate a dataset with relevant keywords from a controlled vocabulary using its definition sentences and the dataset's abstract.

- Materials: The dataset's abstract text; access to the controlled vocabulary with keyword definitions (e.g., MeSH Browser).

- Procedure:

- Text Preparation: Extract the abstract text from your dataset's metadata. Perform standard text preprocessing (e.g., tokenization, removal of stop words, stemming).

- Vocabulary Processing: For each keyword in the controlled vocabulary, preprocess its definition sentence in the same manner.

- Similarity Calculation: Use a model (e.g., continuous bag-of-words) to calculate the semantic similarity between the preprocessed abstract and every preprocessed keyword definition [23] [22].

- Ranking and Selection: Rank all keywords by their similarity score. The top K keywords (e.g., K=100) are presented as recommendations for the data provider to select from [23] [22].

Protocol 2: MeSH Co-occurrence Analysis for Biomarker Research

This protocol uses association analysis on MeSH terms in PubMed to discover molecular mechanisms linking a metabolite and a disease [24].

- Objective: To automatically recommend MeSH terms (k′) that are statistically associated with both a metabolite MeSH term (c) and a disease MeSH term (k).

- Materials: A list of candidate biomarker metabolites; a researcher's known keyword (e.g., a disease name); PubMed MeSH co-occurrence data.

- Procedure:

- Term Mapping: Use the MeSH browser to find the official MeSH IDs for your metabolite (c) and your known keyword/disease (k).

- Association Scoring: For a candidate MeSH term (k′), calculate two association scores: A(c, k′) and A(k′, k) based on their co-occurrence frequency in PubMed articles. Methods like "confidence" can be used [24].

- Connectivity Score: Calculate the connectivity score S(c, k′, k) as the product of the two association scores: S(c, k′, k) = A(c, k′) × A(k′, k) [24].

- Statistical Validation: Establish a null distribution by creating randomized databases. Determine the statistical significance (p-value) and false discovery rate (FDR) for the connectivity score. Retain MeSH terms k′ that meet a significance threshold (e.g., FDR < 0.01) [24].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of a Keyword Recommendation Model [23]

| Metric | Value Achieved |

|---|---|

| Weighted Precision | 0.88 |

| Weighted Recall | 0.76 |

| Weighted F1-Score | 0.82 |

| Recommendation Efficiency | 96.3% |

| Recommendation Precision | 95.8% |

| User Satisfaction Rate | 99.5% |

Table 2: Distribution of Search Query Types [19] [20]

| Keyword Type | Approximate Percentage of All Searches |

|---|---|

| Long-Tail Keywords (Specific phrases) | ~70% |

| Mid-Tail Keywords | ~15-20% |

| Short-Tail/Head Keywords (Generic terms) | ~10-15% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Keyword Recommendation Experiments

| Tool Name | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) | The NLM's controlled vocabulary thesaurus used for indexing articles in PubMed/MEDLINE. Essential for life sciences keyword annotation. | [25] [18] |

| GCMD Science Keywords | A structured vocabulary containing over 3000 keywords for annotating earth science datasets. | [22] |

| WordStream Keyword Tool | A free tool that helps generate a list of long-tail keyword phrases based on an initial seed word. | [19] |

| BrightEdge Data Cube | Keyword technology used to identify relevant, high-traffic keywords for SEO and content optimization. | [20] |

| PubMed Subset & Co-occurrence Data | A curated subset of PubMed, often limited to metabolism-related MeSH terms, used to calculate statistical associations between concepts. | [24] |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Keyword recommendation method selection.

Diagram 2: MeSH co-occurrence analysis workflow.

From Theory to Lab Bench: Practical Keyword Recommendation Frameworks

The KEYWORDS Framework is a structured, 8-step acronym designed to standardize keyword selection for scientific manuscripts in the biomedical field [26]. It addresses a critical yet often-overlooked detail in modern scientific research, where keywords have evolved from simple indexing tools into fundamental building blocks for large-scale data analyses like bibliometrics and machine learning algorithms [26].

This framework ensures that keywords consistently capture the core aspects of a study, creating a more interconnected and easily navigable scientific literature landscape. It enhances the comparability of research, reduces missing data, and facilitates comprehensive Big Data analyses, ultimately leading to more effective evidence synthesis across multiple studies [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Framework Implementation Issues

Problem 1: Difficulty in Differentiating Between "Key Concepts" and "Who" Elements

- Symptoms: Keywords feel redundant or overly broad; low specificity in database searches.

- Solution:

- Preventative Step: Ask, "Is this term the general field (Key Concept) or the specific population/object of study (Who)?"

Problem 2: Selecting Keywords That Are Too Broad or Too Narrow

- Symptoms: Paper is not discovered in searches (too narrow) or is lost among irrelevant results (too broad).

- Solution:

- Use the framework to balance specificity and generality [26].

- Employ standardized terminology like MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) to enhance consistency [26].

- Example: Instead of just "Pain," use "Chronic Pain" (more specific) or "Chronic Pain Patients" (Who) paired with "Qualitative Research" (Research Design) [26].

Problem 3: Applying the Framework to Non-Traditional Study Designs (e.g., Bibliometric Analysis)

- Symptoms: Uncertainty in mapping framework elements to studies without classic laboratory experiments.

- Solution: Adapt the definitions of the categories [26]:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a standardized framework for keyword selection necessary?

Modern research relies heavily on Big Data analyses. When keywords are chosen inconsistently, they become unreliable data points, making it difficult to conduct accurate, large-scale bibliometric or machine learning analyses. A structured framework ensures data integrity and improves the discoverability and interconnectedness of scientific literature [26].

Q2: How many keywords should I select using this framework?

The framework recommends selecting at least eight relevant keywords—one from each of the eight categories represented by the letters in KEYWORDS. This ensures comprehensive coverage of your study's core aspects [26].

Q3: Is the KEYWORDS framework only for experimental biomedical studies?

No. While it is highly suited for experimental studies, observational studies, reviews, and bibliometric analyses, it is also flexible enough to be adapted for various research designs within the biomedical field. However, it may be inappropriate for theoretical, opinion-based, or philosophical articles [26].

Q4: What is the most common mistake to avoid when using this framework?

The most common mistake is creating redundant keywords that do not distinctly map to the different elements of the framework. Careful planning during the initial keyword selection phase is crucial to avoid this and ensure each keyword adds unique, valuable information [27].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing the KEYWORDS Framework

Objective

To systematically apply the KEYWORDS framework for selecting optimal keywords for a biomedical manuscript, thereby maximizing its discoverability and utility for large-scale data analysis.

Methodology

- Deconstruct Your Study: Break down your manuscript into its fundamental components.

- Map to KEYWORDS Categories: For each component, assign it to the most relevant letter of the KEYWORDS acronym as defined below.

- Select the Keyword: Choose the most precise and commonly accepted term for each category.

- Validate and Refine: Check terms against standardized vocabularies like MeSH and ensure a balance between specificity and generality.

The KEYWORDS Acronym: Definitions and Examples

| Letter | Category | Description | Example (Experimental Study) | Example (Bibliometric Analysis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | Key Concepts | Broad research domain/field | Gut Microbiota [26] | Oral Biofilm, Dental Medicine [26] |

| E | Exposure/Intervention | The treatment, variable, or analysis method being studied | Probiotic Supplementation [26] | Network Analysis, Citation Analysis [26] |

| Y | Yield | The expected or measured outcome | Microbiota Composition, Symptom Relief [26] | Citation Impact, Research Trends [26] |

| W | Who | The subject, sample, or problem of interest | Irritable Bowel Syndrome patients [26] | Clinical Trials (as the unit of analysis) [26] |

| O | Objective/Hypothesis | The primary goal or central question of the research | Probiotics Efficacy [26] | H-index, Research Networks [26] |

| R | Research Design | The methodology used in the study | Randomized Controlled Trial [26] | Bibliometrics [26] |

| D | Data Analysis Tools | Software or methods for data analysis | SPSS [26] | VOSviewer [26] |

| S | Setting | The physical or database environment where the research was conducted | Clinical Setting [26] | Web of Science, Scopus [26] |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

KEYWORDS Framework Implementation Workflow

Troubleshooting Keyword Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Resource | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) | A controlled vocabulary thesaurus used for indexing articles in PubMed; using MeSH terms ensures consistency and improves accurate retrieval [26]. |

| Google Keyword Planner | Provides data on search volume and competition for specific terms, useful for understanding common terminology usage [28]. |

| Bibliometric Analysis Software (VOSviewer) | Tool used to map research trends and networks; proper keyword selection is crucial for the accuracy of such analyses [26]. |

| Standard Statistical Packages (SPSS, NVivo, RevMan) | Software for data analysis; including these as keywords (Data Analysis Tools) helps others find studies that used similar methodologies [26]. |

FAQs: Understanding the Core Methodology

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between traditional statistical keyword extraction methods and modern transformer-based approaches?

Traditional methods like YAKE (Yet Another Keyword Extractor) and RAKE are lightweight, unsupervised algorithms that rely on statistical text features such as term frequency and word co-occurrence. They are effective for general use but often fail to grasp domain-specific context. In contrast, modern transformer-based approaches like BERT and fine-tuned Large Language Models (LLMs) use deep learning to understand semantic meaning and contextual relationships within text. This allows them to adapt to the specific terminology and structure of scientific literature, leading to more accurate and relevant keyword extraction, though they require more computational resources and potential fine-tuning [29] [30] [31].

Q2: Why might a pre-trained BERT model perform poorly on my set of materials science abstracts, and how can I improve it?

Pre-trained models like generic BERT are often trained on general-purpose text (e.g., Wikipedia). They struggle with the highly specialized vocabulary and complex entity relationships found in scientific domains like materials science. To improve performance, you must fine-tune the model on a dataset representative of your specific domain. This process involves further training the model on your annotated scientific texts, allowing it to learn the unique language patterns and key concepts relevant to your field [29] [32].

Q3: What is a major challenge with LLMs like GPT-3 for structured information extraction, and how can it be addressed?

A significant challenge is that off-the-shelf LLMs without specific training may output information in an inconsistent or unstructured format, making it difficult to use for building databases. The solution is to fine-tune the LLM on a set of annotated examples (typically 100-500 text passages) where the desired output is formatted in a precise schema, such as a list of JSON objects. This teaches the model not only what to extract but also how to structure it, enabling the automated creation of structured knowledge bases from unstructured text [31].

Q4: When extracting keywords, how can I handle complex, hierarchical relationships between entities (e.g., "La-doped thin film of HfZrO4")?

Conventional Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Relation Extraction (RE) pipeline models often fail to preserve these complex hierarchies. A more flexible approach is to use a fine-tuned LLM for joint NER and RE. Instead of just identifying entities, the model can be trained to output a structured summary (e.g., a JSON object) that captures the composition ("HfZrO4"), the dopant ("La"), and the morphology ("thin film") as an integrated, hierarchical record [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Accuracy in Extracting Domain-Specific Keywords

Problem: Your model is extracting generic words instead of technically relevant keywords from scientific text.

| Solution Step | Description | Relevant Tool/Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Domain Adaptation | Fine-tune a pre-trained model (e.g., BERT) on a labeled dataset from your specific scientific domain to learn its unique vocabulary and context. | BERT, SciBERT [29] |

| 2. Leverage Controlled Vocabularies | For biomedical texts, use ontologies like Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). Find associated terms through co-occurrence analysis to uncover overlooked keywords. | MeSH Co-occurrence Analysis [24] |

| 3. Feature Engineering | For unsupervised models, customize the statistical features (e.g., stopword lists, casing rules) to better align with the conventions of scientific writing. | YAKE, RAKE [30] |

Issue: Model Bias and Inaccurate Sentiment/Topic Analysis

Problem: The extraction or analysis model produces skewed results that do not represent the full spectrum of data.

| Solution Step | Description | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Audit Training Data | Ensure your training dataset is diverse and representative of all the different categories and sub-domains you expect to encounter. | Use stratified sampling during dataset creation. |

| 2. Regular Model Retraining | Periodically retrain your models with new, curated data to adapt to evolving language use and correct for discovered biases. | Schedule quarterly model review and updates. |

| 3. Implement Explainable AI (XAI) | Use frameworks that help you understand why a model made a particular decision, allowing you to identify and correct the source of bias. | Integrated Gradients, LIME [33] |

Issue: Difficulty Processing Multilingual Text or Complex Scientific Jargon

Problem: Direct translation loses nuance, and standard NLP models fail to recognize technical compound terms.

| Solution Step | Description | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Use Multilingual NLP Models | Employ models specifically designed and pre-trained to handle multiple languages and their unique syntactic structures. | Multilingual BERT, XLM-RoBERTa |

| 2. Context-Aware Translation | Apply translation models that are optimized to preserve scientific meaning and technical context, not just literal word-for-word translation. | Domain-specific machine translation APIs |

| 3. Custom Dictionary Integration | Build and integrate a custom dictionary of domain-specific compound terms and jargon into your pre-processing pipeline to ensure they are treated as single units. | Custom tokenization rules in spaCy or NLTK [33] |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Fine-tuning a BERT Model for Educational Text Keyword Extraction

This protocol is based on the "YodkW" model designed for textbook and educational content [29].

- Data Preparation: Collect a dataset of educational texts (e.g., textbook sections, lecture notes) with a corresponding list of key terms provided by the author or a domain expert. This list serves as the ground truth.

- Pre-processing: Clean the text by removing extraneous formatting, images, and tables. Split the text into sentences and tokens.

- Model Selection: Choose a pre-trained BERT model as the base model.

- Fine-tuning: Further train (fine-tune) the BERT model on your educational text dataset. The objective is typically framed as a token classification task, where the model learns to predict which tokens belong to a key concept.

- Evaluation: Evaluate the model's performance by comparing its extracted keywords against the ground truth list using the F1 score, which balances precision and recall [29].

Protocol 2: Implementing an Unsupervised Workflow with YAKE in Spark NLP

This protocol outlines a pipeline for keyword extraction without requiring labeled training data [34] [30].

- Environment Setup: Install Spark NLP and start a Spark session in Python.

- Pipeline Definition: Construct a Spark NLP pipeline with the following stages:

DocumentAssembler: Transforms raw text into a structured 'document' annotation.SentenceDetector: Splits the document into individual sentences.Tokenizer: Breaks sentences down into individual tokens/words.YakeKeywordExtraction: The YAKE algorithm processes the tokens to extract and score keywords [34].

- Execution and Results: Fit the pipeline on your text data. The output will be a list of extracted keywords, each with a score where a lower value indicates a better keyword.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Different Approaches

Table: Summary of Keyword Extraction Methods and Reported Performance

| Method | Type | Key Feature | Domain Tested | Reported Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YodkW (Fine-tuned BERT) [29] | Supervised | Adapts to educational text structure | Educational Textbooks | Improved F1 score vs. traditional algorithms |

| MeSH Co-occurrence Analysis [24] | Association Analysis | Finds connecting terms in literature | Biomedical Research (Metabolomics) | Connectivity Score (S) at FDR < 0.01 |

| LLM (Fine-tuned GPT-3/Llama-2) [31] | Supervised | Extracts complex, hierarchical relationships | Materials Science | Accurate JSON output for structured data |

| YAKE [30] | Unsupervised | Language and domain independent | General Purpose | Keyword score (lower is better) |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Keyword Extraction with Fine-Tuned LLM

Troubleshooting Model Bias Flowchart

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools and Models for Automated Keyword Extraction

| Tool / Model Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| BERT & Transformers [29] | Pre-trained Language Model | Base model for understanding context; can be fine-tuned for specific domains. | Provides deep contextual embeddings, significantly improving relevance. |

| KeyBERT [30] | Python Library | Uses BERT embeddings to create keywords and keyphrases that are most similar to a document. | Simple interface that leverages the power of BERT without requiring fine-tuning. |

| YAKE! [34] [30] | Unsupervised Algorithm | Statistically extracts keywords from a single document. | Fast, unsupervised, and independent of language or domain-specific resources. |

| Python Keyphrase Extraction (pke) [30] | Python Framework | Provides an end-to-end pipeline for keyphrase extraction, allowing for easy customization. | Offers a unified framework for trying multiple unsupervised models. |

| Spark NLP [34] | Natural Language Processing Library | Provides scalable NLP pipelines, including annotators for tokenization, sentence detection, and keyword extraction (e.g., YAKE). | Enables distributed processing of large text corpora, integrating ML and NLP. |

| Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) [24] | Controlled Vocabulary / Thesaurus | A controlled vocabulary used for indexing PubMed articles; can be used for association analysis. | Provides a standardized set of keywords, enabling precise linking of biomedical concepts. |

Mining Scientific Literature and Databases (PubMed, Scopus) for Trend Identification

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is it crucial to use multiple databases like PubMed and Scopus for a comprehensive literature search? Using multiple databases is essential because each indexes a different set of journals and publications. PubMed specializes in biomedical literature, while Scopus offers broader multidisciplinary coverage, including engineering and social sciences. Searching both ensures you capture a more complete set of relevant studies and reduces the risk of missing key research trends [35].

Q2: My initial searches are returning too many irrelevant results. How can I refine my strategy? This is a common issue. You can refine your search by:

- Using Subject Headings: In PubMed, use Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) to search with standardized terminology, which accounts for synonyms and variations in language (e.g., "Hypertension" instead of "High Blood Pressure") [36].

- Applying Field Tags: Restrict your search to specific parts of the citation, such as the title and abstract, using tags like

[tiab][36]. - Leveraging Boolean Operators: Use

ANDto narrow results (requiring all terms to be present) andORto broaden them (including synonyms). UseNOTwith caution to exclude specific concepts [36] [37].

Q3: What is the difference between a keyword search and a MeSH term search in PubMed?

- Keyword Search: Looks for your exact terms in the title, abstract, and other fields. It is literal and does not account for synonyms or related concepts unless you include them [36].

- MeSH Search: Uses a controlled vocabulary of terms assigned by indexers to describe the article's core content. It is conceptual and automatically includes more specific terms in the hierarchy (a feature called "Explode"), making searches more comprehensive and precise [36].

Q4: How can a structured framework help me select effective keywords for my search? A structured framework, such as the KEYWORDS framework, ensures you consider all critical elements of your research, leading to a systematic and consistent keyword selection. This improves the discoverability of your research in large-scale data analyses and helps other researchers find your work more easily. The framework guides you to consider Key concepts, Exposure/Intervention, Yield (outcome), Who (population), and Research Design, among other factors [26].

Q5: A key study I found isn't available in full text. What are my options? Most institutional libraries provide access to full-text articles. Use the "FIND IT @" or similar link provided in the database. If your institution does not have a subscription, you can typically request the article through Interlibrary Loan services, often free of charge for affiliates [36] [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Missed Trends in Search Results

Issue: Your literature mining is failing to identify a consistent or complete research trend, leading to an incomplete understanding of the field.

Solution: Follow this systematic workflow to ensure a comprehensive and reproducible search strategy.

Detailed Steps:

- Pre-Search Planning: Before searching, clearly define your research question and objective. Use a framework like KEYWORDS to map out the essential components of your study [26].

- Select Appropriate Databases: Do not rely on a single source. At a minimum, search both PubMed (for biomedical focus) and Scopus (for multidisciplinary coverage) [35].

- Develop a Robust Search String:

- Use Both MeSH and Keywords: Combine the conceptual power of MeSH terms with the specificity of keyword searches for maximum coverage [36] [37].

- Apply Boolean Logic: Use

ORto group synonyms (e.g.,("heart attack" OR "myocardial infarction")) andANDto link different concepts (e.g.,aspirin AND prevention) [36]. - Employ Syntax Tools: Use quotation marks for phrase searching (e.g.,

"hospital acquired infection") and asterisks*for truncation (e.g.,mobili*finds mobility, mobilization, etc.) [36].

- Iterate and Refine: Analyze the initial results. If the yield is too large, use field tags (e.g.,

[tiab]) or subheadings to focus the search. If it is too small, add more synonyms or remove the least critical concept [36]. - Document and Manage Results: Use citation management software (e.g., EndNote) to organize the retrieved articles. A documented and reproducible search strategy is a critical component of a systematic approach [38].

Problem: Poor Integration of Search Results into a Coherent Analysis

Issue: You have a collection of articles but are struggling to synthesize them into a meaningful trend analysis.

Solution: This problem often stems from a lack of a clear data extraction and analysis plan.

- Define Data to Extract: Before reading, decide what information you need from each paper (e.g., study objective, methodology, data mining techniques used, key findings, conclusions) [39] [38].

- Use a Standardized Form: Create a data extraction form in a spreadsheet or dedicated software to consistently capture information from each study.

- Categorize and Code: Group studies based on common themes, methodologies, or outcomes. For example, you might categorize data mining techniques as "supervised learning," "unsupervised learning," or "natural language processing" [40] [38].

- Visualize and Summarize: Use tables and charts to summarize quantitative data (e.g., frequency of techniques used) and synthesize qualitative findings to articulate the emerging trend [39].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Literature Search for Trend Identification

This protocol outlines a method for identifying trends in a scientific field, such as the use of machine learning for environmental exposure research in diabetes [39].

1. Objective: To systematically identify, evaluate, and synthesize published research on a defined topic to map the evolution of methodologies, focus areas, and findings.

2. Materials and Reagents: Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| PubMed Database | Primary database for biomedical literature; uses MeSH for indexing [36]. |

| Scopus Database | Multidisciplinary abstract and citation database; provides extensive citation analysis [35]. |

| Citation Management Software (e.g., EndNote) | Software for storing, organizing, and formatting bibliographic references [38]. |

| Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist | A tool for assessing the quality and risk of bias in various study designs [38]. |

| Data Extraction Form (e.g., in Excel) | A standardized form for consistently recording data from included studies [39]. |

3. Methodology:

- Search Strategy Design:

- Define the research question using the PICO or KEYWORDS framework [26] [38].

- Identify key search terms, including MeSH terms, keywords, and synonyms.

- Develop the final search string using Boolean operators. For example:

("data mining" OR "machine learning") AND (diabetes) AND ("environmental exposure")[39].

- Literature Screening:

- Execute the search in selected databases (e.g., PubMed, Scopus) and export all results to a citation manager.

- Remove duplicate records.

- Screen titles and abstracts against predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria.

- Retrieve and assess the full text of potentially relevant articles.

- A flowchart, such as the PRISMA diagram, should be used to document this process [39] [38].

- Data Extraction and Synthesis:

- Use the pre-designed data extraction form to collect key information from each included study.

- Categorize studies based on relevant classifications (e.g., type of diabetes, data mining method, category of exposure) [39].

- Perform a qualitative synthesis of findings and, if applicable, a quantitative analysis (e.g., frequency counts of specific methods).

4. Analysis and Visualization:

- Quantitative Analysis: Summarize numerical data, such as the frequency of different data mining techniques or the distribution of studies by country.

- Qualitative Analysis: Thematically analyze the main objectives and conclusions of the studies to identify dominant research streams and gaps [39] [38].

- Outputs: Generate tables and figures (e.g., bar charts, word clouds) to visually represent the extracted data and identified trends [38].

The workflow for this systematic approach, from search to synthesis, is outlined below.

Protocol 2: Applying the KEYWORDS Framework for Systematic Keyword Selection

This protocol provides a step-by-step method for selecting effective keywords to ensure comprehensive literature retrieval and enhance the discoverability of your own research [26].

1. Objective: To generate a standardized and comprehensive set of keywords that fully represent a research study.

2. Methodology: Apply the KEYWORDS framework by selecting at least one term for each of the following categories [26]:

- K - Key Concepts: The central research domain (e.g., "Gut Microbiota").

- E - Exposure/Intervention: The treatment or factor being studied (e.g., "Probiotics").

- Y - Yield: The expected outcome or measurement (e.g., "Symptom Relief").

- W - Who: The subject or sample (e.g., "Irritable Bowel Syndrome").

- O - Objective or Hypothesis: The goal of the study (e.g., "Efficacy").

- R - Research Design: The methodology used (e.g., "Randomized Controlled Trial").

- D - Data Analysis Tools: The software for analysis (e.g., "SPSS").

- S - Setting: The environment or data source (e.g., "Clinical Setting," "PubMed").

3. Analysis: The resulting keywords provide a multi-faceted representation of the study, improving its indexing and retrieval in bibliographic databases and supporting more accurate large-scale data analyses like bibliometric studies [26].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Major Bibliographic Databases for Literature Mining

| Database | Primary Focus | Coverage Highlights | Key Searching Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | Biomedicine, Life Sciences | MEDLINE content (>5,200 journals), PubMed Central, pre-1946 archives [36]. | Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), Automatic Term Mapping, Clinical Queries [36]. |

| Scopus | Multidisciplinary | Over 28,000 current titles, extensive book and conference coverage, strong citation tracking [35]. | CiteScore metrics, advanced citation analysis, includes MEDLINE content [35]. |

| Web of Science | Multidisciplinary (Science, Social Sciences, Arts) | Highly selective coverage of ~12,000 journals, strong historical and book coverage [35]. | Journal Impact Factor, extensive citation analysis, chemical structure searching [35]. |

| Embase | Biomedicine, Pharmacology | Over 8,400 journals, with strong international coverage and unique content not in MEDLINE [35]. | Emtree thesaurus, detailed drug and medical device indexing [35]. |

This table summarizes findings from a review of 50 studies that used data mining to fight epidemics, illustrating how quantitative data from a literature review can be structured [38].

| Category | Classification | Frequency (n=50) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most Addressed Disease | COVID-19 | 44 | 88% |

| Primary Data Mining Technique | Natural Language Processing | 11 | 22% |

| Learning Paradigm | Supervised Learning | 45 | 90% |

| Common Software Used | SPSS | 11 | 22% |

| Common Software Used | R | 10 | 20% |

## FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support section addresses common challenges researchers face when using social media and digital platforms to track emerging scientific discourse for keyword recommendation in scientific data research.

### Platform Selection and Setup

Q1: Which social platforms are most valuable for tracking emerging scientific discourse in 2025?

A: Platform selection should be guided by your specific research domain and target audience. Current evidence indicates:

- Reddit hosts specialized communities (subreddits) where detailed scientific discussions occur. Relevant subreddits include r/medicine (494,000+ members) and r/nursing (931,000+ members) for healthcare professionals [41] [42].

- YouTube remains a primary platform for long-form educational content and analysis of major scientific events [41].

- LinkedIn has gained traction with enhanced video capabilities and serves as a platform for professional dialogue among researchers and HCPs [43] [42].

- Emerging Platforms like Bluesky (24+ million users) and Threads are attracting users seeking alternatives to X (formerly Twitter), though their scientific utility is still evolving [41].

Troubleshooting Tip: If your chosen platform lacks engagement, diversify your investments across multiple platforms to mitigate the risk of platform instability or policy changes [43].

Q2: How do I efficiently monitor multiple platforms without being overwhelmed?

A: Implement a structured monitoring system:

- Utilize social listening tools to continuously monitor healthcare professional (HCP) dialogue and sentiment in real-time [42].

- Establish a platform portfolio aligned with your audience's habits, testing emerging platforms incrementally before significant resource commitment [42].

- Focus on micro-communities where high-value, peer-led scientific discussions occur rather than attempting to monitor all content broadly [42].

### Data Collection and Methodology

Q3: What methodology can I use to systematically extract and analyze keywords from digital discourse?

A: Follow this validated methodology for research structuring [3]:

- Article Collection: Gather bibliographic data using platform APIs (e.g., Crossref, Web of Science) with field-specific search terms, applying filters for document type and publication year.

- Keyword Extraction: Process text (e.g., article titles, post content) using an NLP pipeline (e.g., spaCy's

en_core_web_trf). Use lemmatization to find base word forms and part-of-speech tagging to consider only adjectives, nouns, pronouns, or verbs as keywords [3]. - Research Structuring: Build a keyword co-occurrence matrix, transform it into a network where nodes are keywords and edges represent co-occurrence frequency. Use graph analyzers (e.g., Gephi) and algorithms (e.g., Louvain modularity) to identify keyword communities and representative keywords [3].

Troubleshooting Tip: If keyword extraction yields noisy results, refine your NLP pipeline's stopword list and validate the part-of-speech tagging rules for your specific scientific domain.

Q4: How can I measure engagement quality when analyzing scientific discourse?

A: Move beyond basic metrics by incorporating passive consumption data. Research introduces an Active Engagement (AE) metric that quantifies the fraction of users who take active actions (likes, shares) after being exposed to content [44]. Studies of polarized online debates found that increased active participation correlates more strongly with multimedia content and unreliable news sources than with the producer's ideological stance, suggesting engagement quality is independent of echo chambers [44].

Troubleshooting Tip: If engagement metrics seem inconsistent, analyze both active participation and the characteristics of content (e.g., presence of multimedia, source reliability) that drive such engagement.

### Content Strategy and Optimization

Q5: What types of content drive the most meaningful engagement for scientific topics?

A: Evidence from 2025 indicates several effective formats:

- Video Content: Dominates for capturing attention and fostering connections. YouTube is key for leisure and analysis, while TikTok has become a primary search source for Gen Z for health information [41].

- Long-form Episodic Content: Podcasts and serialized content allow comprehensive topic exploration, valued by healthcare audiences seeking depth [41].

- Authentic Narratives: Patient stories and human experiences counter homogenized AI-generated content, creating deeper emotional connections and engagement [41].

Troubleshooting Tip: If your content lacks resonance, integrate real-time social listening to understand live HCP conversations and emerging concerns, then create content that addresses these timely topics [42].

Q6: How should I approach keyword strategy for discovering emerging scientific trends on social platforms?

A: Modern keyword research must evolve beyond traditional methods:

- Focus on User Intent: Categorize searches by informational, navigational, or transactional intent rather than just keyword volume [45].

- Target Long-tail Keywords: These specific, conversational phrases have lower competition and higher conversion rates, especially valuable for voice search optimization [45].

- Leverage AI-powered Tools: Use natural language processing and machine learning to identify semantic patterns and keyword clusters that may not be evident through manual research [1].

- Target SERP Features: Optimize content for "People Also Ask" boxes and featured snippets by using clear, direct answers in Q&A format [45].

Troubleshooting Tip: If targeting highly competitive keywords, identify "zero-volume" keywords—specific phrases that report low search volume but indicate high user intent and typically have minimal competition [45].

### Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Keyword Network from Digital Discourse

Purpose: To systematically identify and visualize emerging research trends through keyword co-occurrence analysis [3].

Materials:

- Computational environment with Python and spaCy library

- Social media or publication data source

- Graph visualization software (e.g., Gephi)

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Gather scientific text data (publication titles, social media posts) via platform APIs using relevant search terms.

- Text Preprocessing:

- Tokenize text using spaCy's NLP pipeline

- Apply lemmatization to reduce words to base forms

- Filter tokens using Universal Part-of-Speech tagging, retaining only adjectives, nouns, pronouns, and verbs

- Network Construction:

- Identify all possible keyword pairs within each document/post

- Calculate co-occurrence frequencies across the entire dataset

- Build a keyword co-occurrence matrix where cells represent pair frequencies

- Transform matrix into a network graph with keywords as nodes and co-occurrences as edges

- Community Detection:

- Apply the Louvain modularity algorithm to identify keyword communities

- Interpret communities based on keyword semantic relationships

Protocol 2: Measuring Active Engagement in Scientific Discourse

Purpose: To quantify and analyze active user participation in scientific discussions on digital platforms [44].

Materials:

- Social media data with impression metrics

- Computational environment for data analysis

- Statistical analysis software

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Collect social media data that includes both active engagement metrics (likes, shares, comments) and passive consumption metrics (impressions).

- AE Metric Calculation: Compute Active Engagement (AE) as the ratio of active engagements to total impressions: AE = (Total Active Engagements / Total Impressions) × 100.

- Content Characterization: Categorize content by type (multimedia vs. text), source reliability, and topic domain.

- Correlation Analysis: Analyze relationships between AE scores and content characteristics using appropriate statistical methods.

- Platform Comparison: Compare AE distributions across different platforms and community types to identify optimal engagement environments.

Table 1: Social Media Platform Comparison for Scientific Discourse Analysis

| Platform | Key Strengths | Active User Base | Relevance to Scientific Discourse | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialized communities (subreddits) for detailed discussions [41] | 500M+ global users; 267.5M weekly active users [41] | High - dedicated communities for diseases, treatments, and professional exchange [41] | Ideal for hosting AMA sessions; strong peer-to-peer recommendation value [41] [42] | |

| YouTube | Long-form educational content; video analysis of scientific events [41] | 82% of users visit for leisure [41] | Medium-High - preferred for comprehensive topic exploration [41] | Over half of viewers prefer creator analysis to watching actual events [41] |

| Professional networking; enhanced video capabilities [43] | Not specified in results | Medium - growing platform for HCP dialogue and professional content [42] | Micro-communities of clinicians engaging in high-value discussions [42] | |

| TikTok/Short-form Video | Health information discovery for younger audiences [41] | Nearly 40% of young users prefer over Google for searches [41] | Medium - effective for reaching younger healthcare consumers [41] | Platform uncertainty in some markets requires contingency planning [43] |

Table 2: Keyword Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NLP Pipeline (spaCy) | Text tokenization, lemmatization, and part-of-speech tagging [3] | Essential for preprocessing text data before keyword extraction; uses transformer-based models for high accuracy [3] |

| Social Listening Tools | Real-time monitoring of HCP dialogues and sentiment [42] | Provides continuous intelligence on emerging topics and concerns in scientific communities [42] |

| AI-Powered Keyword Research Tools | Identification of semantic patterns and keyword clusters [1] | Uses machine learning to uncover relationships between concepts that may not be evident through manual research [1] |

| Graph Analysis Software (Gephi) | Network visualization and community detection [3] | Enables visualization of keyword relationships and identification of research communities through modularity algorithms [3] |

| Active Engagement Metric | Quantifies ratio of active interactions to passive consumption [44] | Provides more accurate measure of content resonance than engagement counts alone [44] |

### System Architecture Visualization

This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers conducting various types of studies, with a specific focus on selecting effective keywords using a standardized framework to enhance data discoverability and utility in scientific databases.

Keyword Recommendation Framework: The KEYWORDS Methodology

Selecting appropriate keywords is a critical yet often overlooked step in the research process. In the era of Big Data, keywords have evolved beyond simple indexing tools; they are now fundamental for large-scale bibliometric analyses, trend mapping, and machine learning algorithms that identify research connections and predict future directions [26]. A structured approach ensures keywords consistently capture a study's core aspects, making research more discoverable and its data more valuable for secondary analysis.

The KEYWORDS framework provides a systematic method for selecting comprehensive and effective keywords [26]. Its development was inspired by established frameworks like PICO and PRISMA, and it is designed to capture the essential elements of a biomedical study.

The process for applying this framework to any study type is outlined below:

The following table details the eight components of the KEYWORDS framework, which form the basis for the case studies in subsequent sections [26].

Table 1: The KEYWORDS Framework Components

| Framework Letter | Component Represents | Description |

|---|---|---|

| K | Key Concepts | The broad research domain or field of study. |

| E | Exposure/Intervention | The treatment, variable, or agent being studied. |

| Y | Yield | The expected outcome, result, or finding. |

| W | Who | The subject, sample, or problem of interest (e.g., population, cell line). |

| O | Objective/Hypothesis | The primary goal or research question of the study. |

| R | Research Design | The methodology used (e.g., RCT, Qualitative, Bibliometric Analysis). |

| D | Data Analysis Tools | The software or methods used for analysis (e.g., SPSS, NVivo, VOSviewer). |

| S | Setting | The environment where the research was conducted (e.g., clinical, community, database). |

Troubleshooting by Study Type: Case Studies and FAQs

Case Study: Experimental Study

Study Title: Effect of Probiotic Supplementation on Gut Microbiota Composition in Patients with IBS: An RCT

FAQ: Why is my experimental plasmid cloning failing to produce correct constructs?

- Problem: No colonies, satellite colonies, or no positive clones after screening.

- Solution: Follow a systematic troubleshooting guide [46]:

- Design: Use in silico cloning software to verify your strategy and avoid enzymes blocked by methylation.

- Fragments: Check digestion on a gel; optimize PCR primers and conditions for difficult templates.

- Purification: Gel-purify fragments to remove contaminants and quantify DNA concentration accurately.

- Assembly: Use a molar ratio of 1:2 (vector:insert) as a starting point and optimize.

- Transformation: Verify antibiotic efficacy, competent cell quality, and strain. Use different strains (e.g., stbl2) for problematic constructs.

- Screening: Sequence the ligation regions and areas amplified by PCR.

Keyword Recommendations using the KEYWORDS Framework [26]:

| Framework Component | Suggested Keyword |

|---|---|

| Key Concepts | Gut microbiota |

| Exposure/Intervention | Probiotics |

| Yield | Microbiota Composition, Symptom Relief |

| Who | Irritable Bowel Syndrome |

| Objective | Probiotics Efficacy |

| Research Design | Randomized Controlled Trial, Quantitative |

| Data Analysis Tools | SPSS |

| Setting | Clinical Setting |

Case Study: Observational Study

Study Title: Experiences of Living with Chronic Pain: A Qualitative Study of Patient Narratives

FAQ: How can I ensure my qualitative study's keywords reflect its depth and context?