Autonomous Precursor Selection for Materials Synthesis: AI-Driven Strategies for Accelerated Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in automating precursor selection for materials synthesis, a critical bottleneck in the discovery of advanced materials.

Autonomous Precursor Selection for Materials Synthesis: AI-Driven Strategies for Accelerated Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in automating precursor selection for materials synthesis, a critical bottleneck in the discovery of advanced materials. It covers the foundational shift from trial-and-error methods to data-driven approaches, detailing specific algorithms and platforms that leverage thermodynamic data and historical literature. For researchers and drug development professionals, the content provides actionable methodologies for implementation, strategies for troubleshooting synthesis failures, and comparative validation of autonomous systems against traditional techniques. The review synthesizes evidence from recent breakthroughs, including autonomous laboratories, to demonstrate how these technologies are poised to accelerate the design of functional materials for biomedical and clinical applications.

The Paradigm Shift: From Trial-and-Error to AI-Guided Synthesis

Solid-state synthesis is a fundamental method for developing new inorganic materials and technologies. Despite advancements in in situ characterization and computational methods, experiments for new compounds often require testing numerous precursors and conditions, as outcomes remain difficult to predict [1]. The core challenge lies in selecting optimal precursor combinations that successfully lead to a high-purity target material and avoid the formation of stable intermediate byproducts that consume the thermodynamic driving force and prevent the target from forming [1]. This challenge is particularly acute for metastable materials, which are not the most thermodynamically stable under synthesis conditions but are vital for technologies like photovoltaics and structural alloys [1]. Traditionally, precursor selection relies on researcher intuition and heuristics, but the absence of a clear roadmap for novel materials can lead to extensive, unsuccessful experimental iterations [1]. Autonomous experimentation platforms are now emerging to address this complexity, using algorithms to guide and optimize synthesis planning.

Quantitative Challenges in Precursor Selection

The difficulty of precursor selection is quantified by experimental success rates. In a dedicated study involving 188 synthesis experiments targeting YBa₂Cu₃O₆.₅ (YBCO) with a short 4-hour hold time, only 10 experiments (5.3%) yielded pure YBCO without detectable impurities. Another 83 experiments (44.1%) resulted in partial yield of YBCO alongside unwanted byproducts [1]. This underscores that successful synthesis is the exception rather than the rule when precursors are not optimally chosen.

Analysis of text-mined synthesis data from the literature reveals strong dependencies in precursor pair selection, deviating from random chance [2]. For instance, nitrate precursors like Ba(NO₃)₂ and Ce(NO₃)₃ show a high probability of being used together, likely due to compatible properties like solubility [2].

Table 1: Analysis of Synthesis Outcomes for YBCO from 188 Experiments

| Outcome Category | Number of Experiments | Percentage of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Successful Synthesis (Pure YBCO) | 10 | 5.3% |

| Partial Success (YBCO with Impurities) | 83 | 44.1% |

| Failed Synthesis (No YBCO) | 95 | 50.6% |

Autonomous Approaches to Precursor Selection

The ARROWS3 Algorithm

ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) is an algorithm that incorporates physical domain knowledge to automate precursor selection [1]. Its logical workflow is designed to actively learn from experimental outcomes.

ARROWS3 functions through a continuous loop of computation and experimentation [1]:

- Initial Ranking: For a given target material, the algorithm generates a list of stoichiometrically balanced precursor sets. Without prior experimental data, it ranks these sets based on the calculated thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target, as reactions with more negative ΔG values tend to proceed more rapidly [1].

- Experimental Proposal and Analysis: The top-ranked precursor sets are tested across a range of temperatures. Techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) coupled with machine-learned analysis are used to identify the crystalline intermediates formed at different stages, revealing the reaction pathway [1].

- Model Update and Re-ranking: When experiments fail, ARROWS3 learns from the outcomes. It identifies which pairwise reactions led to stable intermediates that consumed the available driving force. The algorithm then updates its model to predict and avoid these intermediates in untested precursor sets, re-ranking them based on the predicted driving force remaining for the target-forming step (ΔG′) [1].

- Validation: This approach was validated on a dataset of 188 YBCO synthesis procedures. ARROWS3 identified all effective precursor sets while requiring substantially fewer experimental iterations compared to black-box optimization methods like Bayesian optimization or genetic algorithms [1].

Machine Learning from Scientific Literature

Another data-driven strategy machines the similarity between materials from vast synthesis databases to recommend precursors. This method mimics the human approach of repurposing recipes for similar, previously synthesized materials [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Autonomous Precursor Selection Strategies

| Feature | ARROWS3 (Physics-Informed) | Literature-Based ML (Data-Driven) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Active learning from experiments; avoids intermediates with low ΔG′ [1] | Machine-learned materials similarity from text-mined literature data [2] |

| Key Input Data | Calculated reaction energies (ΔG), experimental XRD patterns [1] | Database of 29,900+ synthesis recipes from scientific papers [2] |

| Output | Dynamically updated ranking of precursor sets | Recommended precursor sets based on analogues |

| Reported Success Rate | Identified all effective precursors for YBCO with fewer experiments [1] | 82% success rate for 2,654 unseen test targets [2] |

| Advantages | Incorporates thermodynamics; adapts to real experimental results | Captures decades of human heuristic knowledge; scalable |

The workflow involves [2]:

- Knowledge Base Construction: A large dataset of solid-state synthesis recipes is compiled, for example, 33,343 experimental recipes text-mined from 24,304 scientific papers [2].

- Materials Encoding: An encoding neural network (PrecursorSelector) learns to represent a target material as a numerical vector based on its synthesis context, specifically the precursors used to make it. This self-supervised model brings the vector representations of materials with similar precursors closer together in a latent space [2].

- Similarity and Recommendation: For a novel target material, the algorithm queries the knowledge base to find the most similar material based on their encoded vectors. The precursor set from this reference material is then recommended for the new target, effectively repurposing historical heuristic knowledge [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Validating Precursor Selection

The following protocol is adapted from methods used to validate the ARROWS3 algorithm, focusing on the synthesis of YBa₂Cu₃O₆.₅ (YBCO) from oxide and carbonate precursors [1].

Materials and Equipment

- Precursor Powders: Y₂O₃, BaCO₃, CuO.

- Equipment: Mortar and pestle or ball mill, alumina crucibles, tube furnace, X-ray diffractometer (XRD).

Step-by-Step Procedure

Precursor Weighing and Mixing:

- Weigh out the precursor powders in stoichiometric quantities to yield the desired cation ratio for YBCO (Y:Ba:Cu = 1:2:3).

- Transfer the powder mixture to a mortar and pestle or a ball milling jar. Add an appropriate grinding medium (e.g., ethanol) to facilitate mixing.

- Grind or mill for 30-60 minutes to ensure a homogeneous mixture.

Thermal Treatment:

- Transfer the thoroughly mixed powder into an alumina crucible.

- Place the crucible in a tube furnace.

- Heat the sample to a target temperature (e.g., between 800°C and 950°C) in air atmosphere. Use a moderate heating rate (e.g., 5°C/min).

- Hold the sample at the target temperature for a defined period (e.g., 4 to 12 hours). Shorter hold times make the optimization task more challenging by potentially revealing kinetic limitations [1].

Intermediate Analysis:

- After the hold time, remove a small aliquot of the sample from the furnace and allow it to cool.

- Characterize the aliquot using XRD to identify the crystalline phases present. This snapshot of the reaction pathway helps identify stable intermediates that may have formed [1].

Regrinding and Further Heating (Optional):

- Return the remaining sample to the mortar or ball mill and regrind to improve reactant contact and homogeneity.

- Return the reground powder to the furnace for further heating at the same or a higher temperature. This step may be repeated multiple times to drive the reaction to completion.

Final Product Characterization:

- After the final heating cycle, allow the sample to cool to room temperature.

- Perform final XRD analysis to determine the phase purity of the resulting product. The success of the synthesis is quantified by the presence of YBCO peaks and the absence of impurity peaks (e.g., from unreacted BaCO₃ or intermediate phases like Y₂BaCuO₅) [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Solid-State Synthesis

| Item | Function in Synthesis | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oxide Precursors | Provide metal cations in a stable, often refractory form. | Y₂O₃, CuO, TiO₂. Common starting materials for many syntheses [1]. |

| Carbonate Precursors | Source of metal cations; decompose upon heating to release CO₂, which can help drive reactions. | BaCO₃, Li₂CO₃. Decomposition temperature is a key factor in reaction pathway [1]. |

| Nitrate Precursors | Source of metal cations; often have lower decomposition temperatures and can be used in solution-based precursor steps. | Ba(NO₃)₂, Ce(NO₃)₃. Tend to be used together, possibly due to solubility [2]. |

| Alumina Crucibles | Inert containers for holding powder samples during high-temperature reactions. | Withstand temperatures >1000°C; must be chemically inert to the sample. |

| X-Ray Diffractometer (XRD) | Essential characterization tool for identifying crystalline phases in reactants, intermediates, and final products. | Used for in-situ or ex-situ analysis to track reaction progress [1]. |

The Limitations of Traditional Heuristics and Human Intuition

The pursuit of autonomous precursor selection represents a paradigm shift in materials research, moving from experience-driven human decision-making to data-driven, algorithmic discovery. Within this context, a critical examination of traditional heuristics and human intuition reveals significant limitations that hinder the acceleration and scalability of materials synthesis. Heuristics, the efficient mental shortcuts or "rules of thumb" that scientists use to convert complex problems into simpler ones [3], and intuition, the tacit knowledge essential for navigating scientific uncertainties [4], have historically been the bedrock of experimental materials science. However, an increasing body of evidence suggests that these human-centric approaches are fraught with systematic cognitive biases, are difficult to scale or transfer, and are fundamentally constrained by the limited exploration of chemical space in published literature. This application note delineates these limitations through quantitative data analysis, provides experimental protocols for benchmarking human against algorithmic performance, and offers visual frameworks for understanding the transition towards autonomous discovery systems.

Quantitative Analysis of Limitations

The constraints of human intuition and heuristics are not merely theoretical but are demonstrable through quantitative comparisons with artificial intelligence and data-driven algorithms. The tables below summarize key performance metrics across several critical tasks.

Table 1: Performance Comparison in Attribute Inference and Protection Tasks [5]

| Attribute | Task | Human Performance | AI Performance | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (from text) | Inference (Eye Task) | Moderate | High | AI outperformed humans by ~2.5x on differing instances |

| Photo Location | Inference (Eye Task) | Moderate | High | AI outperformed humans by ~2.2x on differing instances |

| Social Network Links | Inference (Eye Task) | Low | Low, but superior | AI outperformed humans by ~1.9x on differing instances |

| All Attributes | Protection (Shield Task) | Near Random | High | Human performance was particularly deficient in privacy protection |

Table 2: Data Limitations in Text-Mined Synthesis Recipes [6]

| Data Characteristic | Solid-State Synthesis Dataset | Solution-Based Synthesis Dataset | Impact on Machine Learning Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (Number of Recipes) | 31,782 | 35,675 | Limited for training robust, generalizable models |

| Veracity (Data Quality) | Low (Only 28% yield a balanced reaction) | Similar Limitations | Propagates errors and limits predictive accuracy |

| Variety (Chemical Diversity) | Constrained by historical research trends | Constrained by historical research trends | Perpetuates anthropogenic and cultural biases |

| Velocity (Data Currency) | Static historical snapshot | Static historical snapshot | Does not dynamically incorporate new knowledge |

Table 3: Performance of Language Models in Synthesis Planning [7]

| Synthesis Task | Metric | Top-Tier LM Performance (e.g., GPT-4) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Recommendation | Top-1 Accuracy | 53.8% | Lower bound, as unreported viable routes may exist |

| Precursor Recommendation | Top-5 Accuracy | 66.1% | More relevant for practical experimental validation |

| Calcination Temperature | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | <126 °C | Matches performance of specialized regression methods |

| Sintering Temperature | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | <126 °C | Matches performance of specialized regression methods |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Benchmarking Human vs. Algorithmic Precursor Selection

Objective: To quantitatively compare the effectiveness of human intuition against machine-learning models in selecting precursors for a target material.

Materials:

- A set of 10-20 novel, computationally predicted materials with no known synthesis reports.

- A control group of materials with known, but non-trivial, synthesis pathways.

- A cohort of experienced materials chemists.

- Machine learning models for precursor recommendation (e.g., a model based on [7] or [6]).

- Access to synthesis and characterization equipment (e.g., furnace, XRD).

Methodology:

- Blinded Precursor Proposal: Present the target materials to both the human cohort and the ML model(s). Humans should propose up to five precursor sets and a synthesis temperature for each target based on their knowledge and intuition. The ML model will generate its own ranked list of precursor suggestions and temperatures.

- Experimental Validation: Execute the top proposed synthesis recipes from both humans and the AI in a controlled laboratory setting (e.g., using an automated platform like the A-Lab [8]).

- Characterization and Success Metric: Characterize the products using X-ray diffraction (XRD). The primary success metric is the yield of the target phase as the majority product (>50%).

- Data Analysis: Compare the success rates of human-proposed recipes versus AI-proposed recipes. Additionally, analyze the nature of failures (e.g., kinetic barriers, precursor volatility) for each group.

Protocol: Interrogating a Text-Mined Database for Anomalous Synthesis Recipes

Objective: To manually analyze a text-mined synthesis database to identify and experimentally validate anomalous recipes that defy conventional heuristic understanding.

Materials:

- A text-mined database of solid-state synthesis recipes (e.g., from [6]).

- Computational resources for calculating reaction energetics (e.g., DFT through the Materials Project).

- Laboratory equipment for solid-state synthesis and XRD.

Methodology:

- Data Filtering: Filter the database for recipes that are statistically uncommon, for instance, those that use precursor combinations or reaction conditions that are rare for the given target material class.

- Thermodynamic Analysis: Compute the reaction energetics for these anomalous recipes using DFT-calculated formation energies. Compare them to the energetics of more conventional synthesis routes.

- Hypothesis Generation: Formulate a mechanistic hypothesis for why the anomalous recipe might be successful despite defying intuition (e.g., it may avoid low-driving-force intermediates).

- Experimental Validation: Design and execute experiments to test the hypothesized mechanism, comparing the performance of the anomalous pathway against the conventional one. The A-Lab's ARROWS³ algorithm provides a framework for this type of active learning [8].

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

From Human-Heuristic to Autonomous Synthesis Workflow

Cognitive Biases in Heuristic Decision-Making

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Resources for Autonomous Precursor Selection Research

| Resource / Solution | Type | Function in Research | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Text-Mined Synthesis Database | Dataset | Provides historical data for training models and identifying trends/anomalies. | Kononova et al. (2019) [6] |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Computational Model | Recalls synthesis conditions from literature; generates synthetic recipes to augment datasets. | GPT-4, Gemini 2.0 [7] |

| Foundation Models for Materials | Computational Model | Learns generalized representations of materials for property prediction and generative design. | [9] |

| Automated Robotic Platform (SDL) | Physical Hardware | Executes synthesis and characterization closed-loop, without human intervention. | The A-Lab [8] |

| Active Learning Algorithm | Software Algorithm | Proposes improved follow-up experiments based on prior outcomes and thermodynamics. | ARROWS³ [8] |

| Ab Initio Phase Stability Database | Dataset | Provides thermodynamic data to assess stability and reaction driving forces. | The Materials Project [8] |

In the pursuit of accelerated materials discovery, autonomous research platforms are transforming how scientists approach synthesis. A critical aspect of this transformation is the development of artificial intelligence (AI) that can intelligently interpret and leverage thermodynamic principles to predict and optimize chemical reactions. For researchers in materials synthesis and drug development, understanding how AI models analyze thermodynamic driving forces and explore complex reaction pathways is fundamental to leveraging these tools effectively. This application note details the core concepts, methodologies, and practical protocols underpinning AI-driven analysis, providing a framework for its application in autonomous precursor selection.

Core Concepts: Thermodynamic Driving Forces and Reaction Pathways

The Role of Thermodynamic Driving Forces

In solid-state materials synthesis, the thermodynamic driving force, typically represented by the negative change in Gibbs free energy (‑ΔG) for a reaction, is a primary indicator of a reaction's feasibility. A larger, more negative ΔG suggests a stronger tendency for the target material to form [1]. However, synthesis outcomes are not determined by the final thermodynamic stability alone. A significant challenge is the formation of stable intermediate phases that consume reactants and exhaust the available driving force before the target product can crystallize [1].

AI algorithms, such as the ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) platform, are designed to navigate this complexity. They do not merely select precursors based on the largest initial ΔG to the target. Instead, they actively learn from experimental data to identify and avoid precursor combinations that lead to these kinetic traps, thereby prioritizing reactions that retain a sufficient driving force (ΔG′) at the final target-forming step [1].

Mapping Reaction Pathways with AI

A reaction pathway describes the stepwise sequence of elementary reactions, involving intermediates and transition states, that connects starting materials to final products. The potential energy surface (PES) is the foundational theoretical construct for understanding these pathways, where reactants, intermediates, and products exist as energy minima, and transition states are first-order saddle points connecting them [10] [11].

AI enhances the exploration of the PES through several advanced approaches:

- Active Learning and Automated Exploration: Tools like ARplorer automate the exploration of reaction pathways by integrating quantum mechanics (QM) and rule-based methodologies. They recursively identify active sites, optimize molecular structures, search for transition states, and perform Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) analysis to confirm the connection between transition states and minima [10].

- Large Language Model (LLM) Guidance: LLMs can be employed to codify chemical logic from literature and databases. This knowledge generates system-specific rules and SMARTS patterns that guide the PES search, filtering out chemically implausible pathways and focusing computational resources on the most promising routes [10].

- Advanced Potential Energy Surfaces: Methods like AIQM2 provide a breakthrough by offering accuracy that approaches the "gold standard" coupled-cluster level at a computational cost orders of magnitude lower than typical Density Functional Theory (DFT). This enables large-scale reaction simulations, including transition state searches and reactive dynamics, that were previously infeasible [11].

AI Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

This section details specific AI algorithms and provides a protocol for their application in autonomous synthesis campaigns.

Key AI Algorithms and Workflows

ARROWS3 for Solid-State Synthesis ARROWS3 is an algorithm specifically designed for autonomous precursor selection in solid-state materials synthesis. Its logical workflow integrates thermodynamic data and experimental feedback [1].

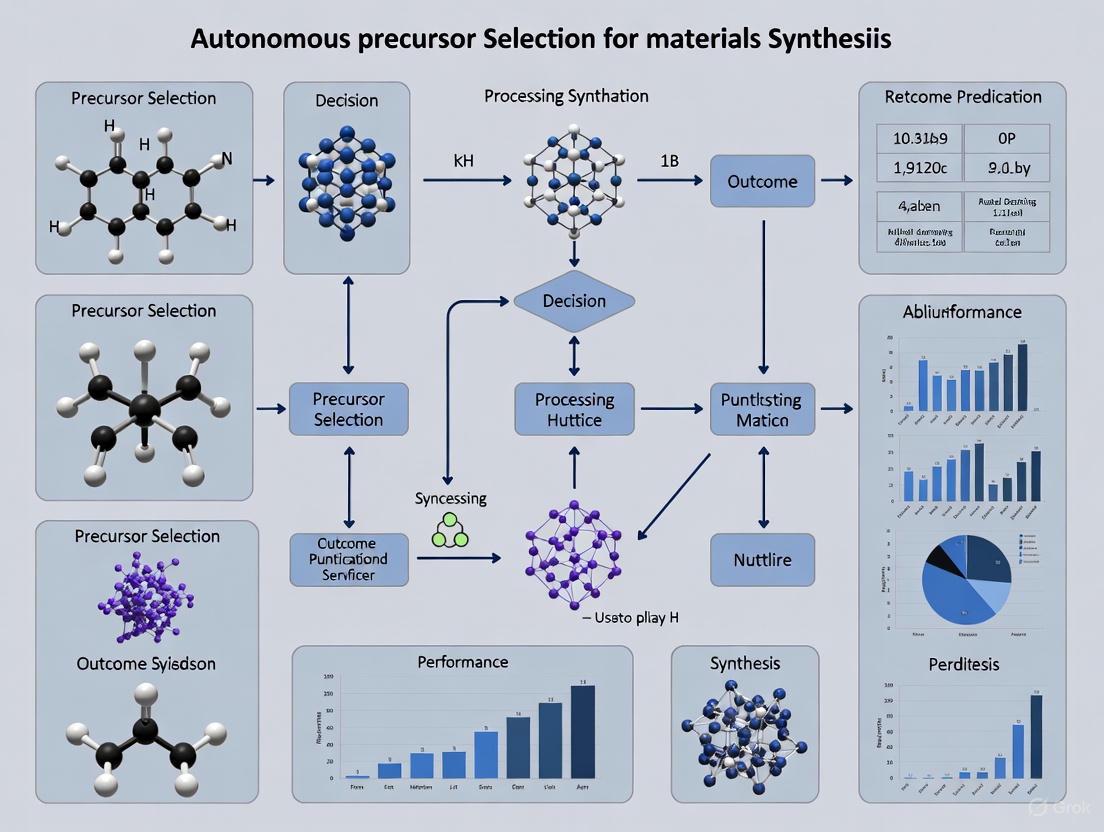

Diagram 1: ARROWS3 autonomous synthesis optimization workflow.

LLM-Guided Pathway Exploration with ARplorer ARplorer represents an advanced methodology for automated reaction pathway exploration, leveraging large language models to incorporate established chemical knowledge [10].

Table 1: Core Components of the ARplorer Program for Pathway Exploration

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Active Site Identification | Identifies atoms and bonds likely to participate in reactions. | Python module (e.g., Pybel) compiles list of active atom pairs from SMILES strings [10]. |

| Transition State Search | Locates first-order saddle points on the PES connecting intermediates. | Combines active-learning sampling with potential energy assessments; uses GFN2-xTB for PES and Gaussian 09 algorithms for search [10]. |

| IRC Analysis | Verifies the transition state correctly connects reactant and product minima. | Follows the reaction path from the TS downhill to confirm it leads to the expected intermediates [10]. |

| LLM-Guided Chemical Logic | Filters unlikely pathways and focuses search based on chemical rules. | Uses LLMs to generate system-specific SMARTS patterns and reaction rules from literature data [10]. |

Application Protocol: Autonomous Synthesis Optimization Campaign

This protocol outlines the steps for using an AI-guided autonomous system, like A-Lab, for solid-state materials synthesis [1] [12].

Objective: To autonomously synthesize a target inorganic material (e.g., YBa₂Cu₃O₆.₅ or a novel metastable phase) by iteratively selecting and testing precursors.

Pre-Experimental Setup

- Target Definition: Specify the composition and crystal structure of the target material.

- Precursor Library: Define a comprehensive library of available solid precursor powders.

- Algorithm Initialization: Configure the AI planner (e.g., ARROWS3) with access to a thermodynamic database (e.g., Materials Project) for initial precursor ranking based on ΔG.

Experimental Cycle

- AI-Driven Experimental Design:

- The AI analyzes the target and proposes a set of precursor combinations and synthesis temperatures for the next iteration.

- In the first iteration, selection is based on the largest initial ΔG to form the target. In subsequent iterations, the selection actively avoids precursors predicted to form stable intermediates.

- Robotic Execution:

- A robotic system automatically weighs, mixes, and pelleted the precursor powders according to the stoichiometric ratios.

- Samples are heated in a furnace under specified conditions (e.g., temperature, atmosphere).

- Automated Characterization and Analysis:

- The synthesized product is automatically transferred for characterization, typically by X-ray Diffraction (XRD).

- A machine learning model (e.g., a convolutional neural network) analyzes the XRD pattern to identify the crystalline phases present, quantifying the yield of the target and any impurity phases.

- Active Learning and Iteration:

- The experimental outcome (success/failure, phases identified) is fed back to the AI algorithm.

- The AI updates its internal model of the reaction network, identifying which pairwise reactions led to undesired intermediates.

- Based on this learning, the algorithm re-ranks all precursor sets, prioritizing those predicted to maximize the remaining driving force (ΔG′) for the target, and the cycle repeats.

Validation: The campaign continues until the target is synthesized with high purity or the experimental budget is exhausted. Successful validation was demonstrated by A-Lab, which synthesized 41 of 58 target materials over 17 days of continuous operation [12].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and experimental "reagents" essential for implementing AI-driven reaction analysis and autonomous synthesis.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Synthesis

| Tool / Material | Type | Function in AI-Driven Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Database (e.g., Materials Project) | Computational Data | Provides initial DFT-calculated reaction energies (ΔG) for precursor ranking and stability assessment [1]. |

| Universal Interatomic Potentials (e.g., AIQM2) | Computational Method | Enables fast, accurate reaction simulations (TS search, dynamics) beyond DFT accuracy, crucial for pathway exploration [11]. |

| Reaction Mechanism Generator (RMG) | Software | Automates the construction of detailed kinetic models by systematically generating possible reaction pathways [13]. |

| Solid Precursor Powders | Experimental Material | The starting materials for solid-state reactions; a diverse and well-characterized library is crucial for AI-driven selection [1] [12]. |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Analytical Technique | The primary characterization method for identifying crystalline phases in synthesis products. Coupled with ML for automated analysis [1] [12]. |

The integration of AI into materials synthesis represents a paradigm shift from intuition-based to data-driven and physics-informed discovery. By interpreting thermodynamic driving forces not as static endpoints but as dynamic quantities that can be consumed by stable intermediates, algorithms like ARROWS3 make intelligent decisions about precursor selection. Furthermore, by leveraging advanced PES exploration tools, LLM-guided chemical logic, and highly accurate force fields, AI can now map complex reaction pathways with unprecedented speed and reliability. These capabilities, when embedded within the closed-loop framework of an autonomous laboratory, create a powerful engine for accelerating the design and synthesis of novel materials and molecules.

The Role of Large-Scale Databases (e.g., Materials Project) in Informing AI Models

Large-scale computational databases have become foundational to modern materials science, serving as the critical data infrastructure that powers artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) models. These repositories, exemplified by the Materials Project, provide systematically computed properties for known and predicted materials, creating the essential training data for AI-driven discovery pipelines [14]. The integration of these databases with AI models has transformed the materials discovery paradigm, enabling the rapid identification of novel materials with tailored properties and accelerating the development of autonomous systems for materials synthesis [15].

Within the specific context of autonomous precursor selection for materials synthesis, these databases provide the thermodynamic and structural knowledge base that AI models leverage to propose viable synthesis pathways. By encoding fundamental materials relationships and stability data, databases like the Materials Project allow AI systems to reason about precursor combinations and reaction intermediates with a level of comprehensiveness unattainable through human intuition alone [15]. This document details the application of these integrated database-AI systems through specific protocols, quantitative benchmarks, and experimental workflows.

Database Foundations for AI Training

Key Large-Scale Materials Databases

Large-scale materials databases provide the structured, high-quality data required for training robust AI models. The table below summarizes the primary databases informing AI development in materials science.

Table 1: Key Large-Scale Materials Databases Informing AI Models

| Database Name | Primary Content | Scale | Key AI Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project | Inorganic crystal structures and properties [15] | Over 150,000 materials [15] | Stability prediction, precursor selection, synthesis planning |

| GNoME Database | Predicted stable crystal structures [16] | 2.2 million new crystals; 380,000 stable materials [16] | Inverse design, crystal structure prediction, materials discovery |

| NanoMine | Polymer nanocomposite experimental data [17] | 2,512 manually curated samples [17] | Polymer composite design, property prediction |

Quantitative Impact on Discovery Rates

The integration of these databases with AI models has dramatically accelerated the pace of materials discovery, as evidenced by recent breakthroughs.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of AI-Database Integration on Discovery Metrics

| Metric | Pre-AI Baseline | With AI-Database Integration | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| New stable materials discovered | ~28,000 materials (cumulative, via computational approaches) [16] | 380,000 stable materials via GNoME [16] | 13.6x |

| Materials discovery rate | Not quantified explicitly | ~800 years of knowledge equivalent [16] | Dramatic acceleration |

| Prediction accuracy | ~50% stability prediction [16] | ~80% stability prediction [16] | 60% relative improvement |

| Experimental success rate | Not explicitly quantified | 71% (41/58 novel compounds) via A-Lab [15] | High validation of predictions |

Experimental Protocols for AI-Driven Materials Discovery

Protocol: Autonomous Synthesis with A-Lab

This protocol details the methodology for autonomous materials synthesis using the A-Lab platform as described in Nature [15]. The workflow integrates computational screening from databases with robotic experimentation.

Materials and Reagents:

- Precursor powders (various inorganic compounds)

- Alumina crucibles

- High-temperature box furnaces (multiple units)

- X-ray diffraction (XRD) sample holders

Procedure:

- Target Identification: Select target materials from stable compounds identified in the Materials Project and cross-referenced with Google DeepMind databases [15]. Filter for air-stable compounds predicted not to react with O₂, CO₂, or H₂O.

- Precursor Selection: Generate up to five initial synthesis recipes using a machine learning model trained on historical synthesis data through natural-language processing of literature [15].

- Temperature Optimization: Determine optimal synthesis temperatures using a secondary ML model trained on heating data from literature [15].

- Robotic Execution:

- Dispensing and Mixing: Use automated stations to dispense and mix precursor powders in stoichiometric ratios.

- Transfer: Transfer mixtures to alumina crucibles using robotic arms.

- Heating: Load crucibles into one of four box furnaces for thermal processing with controlled heating cycles.

- Cooling: Allow samples to cool naturally after synthesis.

- Characterization:

- Grinding: Automatically grind cooled samples into fine powders.

- XRD Analysis: Perform X-ray diffraction to determine phase composition.

- Phase Analysis: Extract phase and weight fractions from XRD patterns using probabilistic ML models trained on experimental structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [15].

- Validation: Confirm identified phases through automated Rietveld refinement.

- Active Learning: If target yield is <50%, employ ARROWS3 active learning algorithm to propose modified synthesis routes based on observed reaction pathways and thermodynamic driving forces [15].

Quality Control:

- Validate ML-identified phases through automated Rietveld refinement [15]

- Cross-reference predicted structures with experimental databases

- Maintain robotic systems through regular calibration checks

Autonomous Synthesis Workflow

Protocol: Data Extraction from Literature Using ChatExtract

This protocol outlines the ChatExtract methodology for extracting accurate materials data from research papers using conversational large language models (LLMs), as published in Nature Communications [18].

Materials and Software:

- Research papers in PDF format

- GPT-4 or similar conversational LLM

- Python environment for automation

- Text preprocessing tools for HTML/XML syntax removal

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Gather relevant research papers through keyword searches.

- Remove HTML/XML syntax and clean text.

- Divide text into individual sentences.

Stage A: Initial Relevance Classification:

- Apply simple relevancy prompt to all sentences: "Does this sentence contain a material property with a value and unit?"

- Weed out sentences classified as negative (non-relevant).

- For positive sentences, construct a passage containing:

- Paper title

- Preceding sentence

- Positive sentence itself

Stage B: Data Extraction:

- Single-Valued Texts: For sentences containing single data points:

- Ask directly for value, unit, and material name.

- Explicitly allow for negative answers if information is missing.

- Multi-Valued Texts: For sentences with multiple data points:

- Determine if multiple values are present.

- Use uncertainty-inducing redundant prompts to verify extractions.

- Ask follow-up questions to confirm relationships between materials, values, and units.

- Single-Valued Texts: For sentences containing single data points:

Validation:

- Enforce strict Yes/No format for verification questions.

- Use redundancy in questioning to overcome hallucinations.

- Maintain conversation history for information retention.

Quality Control:

- Achieves 90.8% precision and 87.7% recall for bulk modulus data [18]

- For critical cooling rates of metallic glasses: 91.6% precision and 83.6% recall [18]

- Multiple verification steps reduce factual inaccuracies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AI-Driven Materials Discovery

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specifications/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| GNoME (Graph Networks for Materials Exploration) | Deep learning tool for predicting stability of new materials [16] | State-of-the-art graph neural network; identifies stable crystal structures |

| A-Lab Robotic Platform | Autonomous synthesis of inorganic powders [15] | Integrated robotics with three stations: preparation, heating, characterization |

| Materials Project Database | Provides computed materials properties for AI training [15] | Contains stability data, formation energies, and crystal structures |

| ChatExtract Framework | Extracts materials data from research literature [18] | Uses conversational LLMs with precision up to 91.6% |

| ARROWS3 Algorithm | Active learning for synthesis route optimization [15] | Integrates ab initio reaction energies with experimental outcomes |

| Probabilistic XRD Analysis | Automated phase identification from diffraction patterns [15] | ML models trained on ICSD data with automated Rietveld refinement |

Integrated Workflow for Autonomous Precursor Selection

The integration of large-scale databases with AI models creates a powerful workflow for autonomous precursor selection, combining computational predictions with experimental validation.

AI-Driven Precursor Selection

Workflow Description:

- Stability Screening: Identify potential target materials using convex hull analysis from databases (e.g., 380,000 stable materials identified by GNoME) [16].

- AI Precursor Selection: Generate initial synthesis recipes using natural language processing models trained on literature data, assessing target "similarity" to known materials [15].

- Thermodynamic Analysis: Evaluate reaction pathways using computed formation energies from databases, prioritizing intermediates with large driving forces (>50 meV/atom) to form targets [15].

- Active Learning Optimization: Refine synthesis routes using observed reaction outcomes, building knowledge of pairwise reactions to avoid intermediates with small driving forces [15].

This integrated approach demonstrates how databases inform AI models at multiple stages, from initial target identification through synthesis optimization, creating a closed-loop autonomous discovery system.

Defining Autonomous Precursor Selection and its Place in the Materials Discovery Pipeline

Autonomous precursor selection represents a paradigm shift in materials synthesis, moving away from traditional reliance on human intuition and literature mining towards algorithmic, data-driven decision-making. This process involves the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and active learning algorithms to automatically select and optimize the solid powder precursors used in the synthesis of inorganic materials, thereby accelerating the discovery and development of novel compounds [14] [8]. The core challenge it addresses is the non-trivial nature of precursor selection, where even for thermodynamically stable materials, only a fraction of possible precursor sets successfully produce the desired target, as evidenced by the A-Lab's experience where just 37% of 355 tested recipes yielded their targets despite a 71% eventual success rate in obtaining the materials themselves [8].

This automation is particularly crucial for closing the gap between computational screening rates and experimental realization of novel materials. Where high-throughput computations can identify thousands of promising candidates, their experimental synthesis traditionally creates a bottleneck that autonomous methods aim to alleviate [8]. The significance of this approach lies in its ability to systematically navigate the complex thermodynamic and kinetic landscape of solid-state reactions, which often involve concerted displacements and interactions among many species over extended distances, making them difficult to model and predict [1].

The ARROWS3 Algorithm: Core Principles and Workflow

Theoretical Foundation

The Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis (ARROWS3) algorithm embodies the cutting edge in autonomous precursor selection. Its design incorporates key physical domain knowledge based on thermodynamics and pairwise reaction analysis, setting it apart from black-box optimization approaches [1]. The algorithm operates on two fundamental hypotheses: first, that solid-state reactions tend to occur between two phases at a time (pairwise reactions), and second, that intermediate phases which leave only a small driving force to form the target material should be avoided, as they often require long reaction times and high temperatures, potentially preventing the target material's formation [1] [8].

ARROWS3 actively learns from experimental outcomes to determine which precursors lead to unfavorable reactions that form highly stable intermediates, preventing the target material's formation. Based on this information, it proposes new experiments using precursors predicted to avoid such intermediates, thereby retaining a larger thermodynamic driving force to form the target [1]. This approach represents a significant advancement over static ranking methods, as it dynamically updates its recommendations based on experimental feedback.

Operational Workflow

The logical flow of ARROWS3 follows a structured sequence that integrates computation, experimentation, and machine learning-driven analysis, creating a closed-loop optimization system as illustrated in the workflow diagram below:

Figure 1: ARROWS3 Autonomous Precursor Selection Workflow

The workflow begins with target material specification, where researchers define the desired composition and structure. The algorithm then generates a comprehensive list of precursor sets that can be stoichiometrically balanced to yield the target's composition. In the absence of experimental data, these precursor sets are initially ranked by their calculated thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target, leveraging formation energies from databases like the Materials Project [1] [8].

Next, the highest-ranked precursors are tested experimentally across a temperature gradient, providing snapshots of the corresponding reaction pathways. The synthesis products are characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), with machine learning models analyzing the patterns to identify intermediate phases that form at each step [1] [8]. ARROWS3 then determines which pairwise reactions led to the formation of each observed intermediate and leverages this information to predict intermediates that will form in precursor sets not yet tested [1].

In subsequent iterations, the algorithm prioritizes precursor sets expected to maintain a large driving force at the target-forming step (ΔG'), even after intermediates have formed. This process continues until the target is successfully obtained with sufficient yield or all available precursor sets are exhausted [1]. Throughout this process, the algorithm continuously builds a database of observed pairwise reactions, which allows the products of some recipes to be inferred without testing, potentially reducing the search space of possible synthesis recipes by up to 80% when many precursor sets react to form the same intermediates [8].

Performance and Validation

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The performance of autonomous precursor selection algorithms has been rigorously validated through experimental implementation. The table below summarizes key quantitative results from validation studies:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Autonomous Precursor Selection Systems

| System/Metric | Target Materials | Success Rate | Experimental Scale | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARROWS3 Validation | YBa₂Cu₃O₆.₅ (YBCO) | Identified all effective routes | 188 synthesis procedures | Required fewer iterations than Bayesian optimization or genetic algorithms | [1] |

| A-Lab Implementation | 58 novel compounds (oxides/phosphates) | 71% (41/58 compounds) | 355 synthesis recipes | 35 obtained via literature-inspired recipes; 6 required active learning optimization | [8] |

| Active Learning Efficacy | 9 targets requiring optimization | 6 obtained after zero initial yield | N/A | Identified routes avoiding low-driving-force intermediates | [8] |

| Search Space Reduction | Various compounds via pairwise analysis | Up to 80% reduction | N/A | Database of observed reactions prevents redundant testing | [8] |

The validation studies demonstrate that ARROWS3 identifies effective precursor sets while requiring substantially fewer experimental iterations compared to black-box optimization methods like Bayesian optimization or genetic algorithms [1]. In the case of YBCO synthesis, from 188 experiments testing 47 different precursor combinations across four temperatures, only 10 produced pure YBCO without detectable impurities, while 83 yielded partial product with byproducts, highlighting the challenging optimization landscape that autonomous methods navigate more efficiently [1].

Case Study: CaFe₂P₂O₉ Synthesis Optimization

A specific example from the A-Lab illustrates the practical impact of autonomous precursor selection. The synthesis of CaFe₂P₂O₉ was optimized by avoiding the formation of FePO₄ and Ca₃(PO₄)₂ as intermediates, which had only a small driving force (8 meV per atom) to form the target. The active learning algorithm identified an alternative synthesis route forming CaFe₃P₃O₁₃ as an intermediate, from which a much larger driving force (77 meV per atom) remained to react with CaO and form CaFe₂P₂O₉, resulting in an approximately 70% increase in target yield [8].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Experimental Workflow

The implementation of autonomous precursor selection follows a standardized experimental workflow that integrates robotic execution with intelligent planning. The diagram below illustrates this integrated materials discovery pipeline:

Figure 2: Integrated Autonomous Materials Discovery Workflow

Detailed Protocol: Solid-State Synthesis with Autonomous Precursor Selection

Objective: To synthesize phase-pure inorganic materials through autonomous selection of optimal solid powder precursors.

Materials and Equipment:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Equipment

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Resources | Materials Project Database, DFT calculations | Provides thermodynamic data for initial precursor ranking | Formation energies for ΔG calculations [1] [8] |

| Precursor Selection Algorithm | ARROWS3 or similar active learning system | Dynamically selects and optimizes precursor sets based on experimental outcomes | Avoids intermediates with small driving force to target [1] |

| Robotics Platform | Automated powder dispensers, mixing stations, robotic arms | Ensures precise, reproducible sample preparation and handling | Three integrated stations for preparation, heating, and characterization [8] |

| Heating Systems | Box furnaces (multiple units recommended) | Enables parallel synthesis at various temperatures | Four box furnaces for simultaneous thermal processing [8] |

| Characterization Tools | X-ray diffractometer with automated sample handling | Provides structural data on synthesis products | XRD with ML analysis for phase identification [1] [8] |

| Analysis Software | ML models for XRD analysis, Rietveld refinement software | Automates phase identification and quantification | Probabilistic ML models trained on ICSD data [8] |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Target Specification and Precursor Generation

- Define the target material by composition and crystal structure.

- Algorithmically generate all possible precursor sets that can be stoichiometrically balanced to yield the target composition.

- In the absence of prior experimental data, rank these precursor sets by their calculated thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target, using formation energies from the Materials Project or similar databases [1].

Literature-Inspired Recipe Proposal (Optional First Pass)

Automated Sample Preparation

- Use automated powder dispensers to accurately weigh and mix precursor powders in the appropriate stoichiometric ratios.

- Transfer homogeneous mixtures into appropriate crucibles (e.g., alumina) using robotic arms [8].

- Implement automated milling or grinding if necessary to ensure sufficient reactivity between precursors.

Robotic Thermal Processing

- Load crucibles into box furnaces using robotic arms.

- Execute heating profiles across a temperature gradient (e.g., 600-900°C) to probe different stages of reaction pathways [1].

- Use appropriate atmosphere control if required by the target material.

- Employ hold times appropriate for the specific system (e.g., 4 hours for initial screening, potentially longer for optimization) [1].

Automated Characterization and Analysis

- After cooling, transfer samples to X-ray diffractometer using robotic arms.

- Grind samples to fine powder if necessary to ensure proper XRD analysis.

- Collect XRD patterns with appropriate parameters for phase identification.

- Use machine learning models trained on experimental structures to identify phases present and their weight fractions [8].

- Confirm ML phase identification with automated Rietveld refinement.

Active Learning and Iteration

- Feed experimental outcomes (successes and failures) back to the active learning algorithm.

- Identify pairwise reactions that led to observed intermediate phases.

- Update the precursor ranking to prioritize sets predicted to avoid intermediates that consume excessive driving force.

- Select new precursor sets that maintain large driving force (ΔG') at the target-forming step.

- Repeat steps 3-6 until target is obtained with sufficient purity or all promising precursor sets are exhausted.

Critical Parameters for Optimization:

- Temperature Range: Must be sufficiently broad to capture different stages of reaction pathways

- Heating Duration: Balanced between reaction completion and experimental throughput

- Precursor Physical Properties: Particle size, morphology, and reactivity that may influence reaction kinetics

- Intermediate Identification: Accurate phase analysis is crucial for informing the algorithm of competing reactions

Integration in the Materials Discovery Pipeline

Autonomous precursor selection represents a critical component in the broader context of autonomous materials discovery, occupying a strategic position between computational screening and final material characterization. The evolution of AI in materials science demonstrates a progression from computational tools to autonomous research partners, with autonomous precursor selection embodying the transition to what has been termed "Agentic Science" [19].

In the A-Lab implementation, autonomous precursor selection functions within a comprehensive workflow that begins with ab initio target identification, proceeds through AI-driven synthesis planning, robotic execution, automated characterization, and active learning-driven iteration [8]. This integration demonstrates how autonomous precursor selection connects to both upstream computational screening and downstream application testing, serving as a crucial bridge that transforms theoretical predictions into tangible materials.

The technology's position in the maturity landscape is reflected in survey data from researchers, which shows that while 26% are comfortable with full automation of scientific workflows, most still prefer human involvement in ideation, hypothesis generation, and complex experimental decisions [20]. This suggests that autonomous precursor selection currently functions most effectively as an augmentation to human expertise rather than a complete replacement, particularly for novel materials systems where domain knowledge and intuition remain valuable.

Technical Requirements and Implementation Considerations

System Architecture Components

Successful implementation of autonomous precursor selection requires integration of several specialized components:

Data Infrastructure: Access to comprehensive thermodynamic databases (e.g., Materials Project) is essential for initial precursor ranking [1] [8]. Additionally, a structured database of observed pairwise reactions enables the system to learn from previous experiments and avoid redundant testing [8].

Algorithmic Capabilities: The core algorithm must combine thermodynamic reasoning with machine learning for both precursor selection and experimental analysis. This includes the ability to calculate reaction energies, predict intermediate formation, and interpret characterization data [1].

Robotic Hardware: Reliable automation of powder handling is particularly challenging due to variations in precursor properties like density, flow behavior, particle size, hardness, and compressibility [8]. Integrated platforms with robotic arms and loosely integrated formulation and characterization units offer flexibility for customized workflows [20].

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Table 3: Implementation Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

| Challenge Category | Specific Challenges | Potential Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Implementation | Powder handling variability, Integration of separate automated steps | Use of flexible robotic arms with modular tooling, Custom end-effector design for powder handling |

| Algorithmic Limitations | Prediction of kinetic barriers, Handling of amorphous phases | Incorporation of heuristic rules from domain experts, Multi-modal characterization to detect amorphous content |

| Data Requirements | Sparse thermochemical data for novel systems, Limited data for kinetic parameters | Transfer learning from related systems, Active learning to prioritize informative experiments |

| Validation and Trust | Ensuring scientific accuracy of AI conclusions, Verification of novel discoveries | Human oversight for novel phenomena, Robust uncertainty quantification in predictions |

Future Directions and Development

The field of autonomous precursor selection continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising directions for advancement. Future systems will likely incorporate more sophisticated multi-objective optimization that balances thermodynamic driving force with practical considerations like precursor cost, availability, and safety [20]. Improved kinetic models that go beyond thermodynamic predictions could further enhance success rates by accounting for reaction rates and barriers.

The integration of large language models and reasoning systems presents another frontier, potentially enabling more sophisticated analogy-based precursor selection and better interpretation of complex experimental outcomes [19]. As these systems mature, we can anticipate greater collaboration between human experts and autonomous systems, with humans focusing on high-level strategy and novel hypothesis generation while algorithms handle the detailed optimization of synthesis parameters [20].

Community-wide efforts to standardize data formats, share datasets including negative results, and develop open-source algorithms will be crucial for accelerating adoption and improving the capabilities of autonomous precursor selection systems [14] [20]. By addressing current challenges in model generalizability, experimental validation, and system integration, autonomous precursor selection is poised to become an increasingly powerful component of the materials discovery pipeline, ultimately reducing the time from materials discovery to commercialization.

AI Tools in Action: Algorithms and Platforms for Autonomous Selection

The synthesis of novel inorganic materials is a fundamental bottleneck in the development of advanced technologies. While computational methods can predict thousands of stable compounds, determining how to synthesize them remains a significant challenge, as convex-hull stability provides no guidance on practical synthesis variables like precursor selection [6]. Natural Language Processing (NLP) has emerged as a transformative technology to bridge this gap by extracting and encoding the collective synthesis knowledge embedded in scientific literature. By converting unstructured text from millions of publications into structured, machine-readable data, NLP enables the development of predictive models that can recommend synthesis pathways for novel target materials, accelerating the transition from materials design to physical realization [21] [2]. This application note details the methodologies, protocols, and practical implementations of NLP for autonomous precursor selection, providing researchers with the tools to leverage historical data for materials synthesis research.

NLP Fundamentals and Data Extraction Pipeline

Natural Language Processing encompasses computer algorithms designed to understand and generate human language. Modern NLP has evolved from handcrafted rules to deep learning approaches, with word embeddings and attention mechanisms enabling models to capture semantic meaning and contextual relationships between words and concepts [21]. In materials science, this capability is crucial for processing the highly specialized terminology and complex descriptions found in synthesis literature.

The foundational step in leveraging historical data is the construction of a structured synthesis database from unstructured text. This process involves multiple stages of text mining and information extraction:

Table 1: Key Stages in NLP Pipeline for Materials Synthesis Data Extraction

| Processing Stage | Primary Function | Techniques/Methods | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Literature Procurement | Identify and access relevant synthesis literature | HTML/XML parsing of publisher databases | Collection of synthesis paragraphs |

| Target/Precursor Extraction | Recognize and classify materials entities | BiLSTM-CRF with |

Annotated targets and precursors |

| Operation Identification | Extract synthesis actions and parameters | Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic modeling [6] | Classified operations (mixing, heating, etc.) |

| Recipe Compilation | Integrate extracted data into structured format | JSON database construction with stoichiometric balancing [6] | Balanced synthesis reactions with parameters |

The extraction of synthesis recipes presents unique challenges, as the same material can serve different roles (target, precursor, or reaction medium) depending on context. Advanced NLP approaches replace all chemical compounds with a universal

Precursor Recommendation Methodologies

Similarity-Based Recommendation Systems

One prominent approach for precursor recommendation leverages machine-learned materials similarity based on synthesis context. This methodology mimics the human approach of consulting precedent synthesis procedures for analogous materials [2]. The process involves:

- Materials Encoding: Training an encoding neural network to create vector representations of materials based on their synthesis contexts, particularly their precursor sets

- Similarity Query: Identifying reference materials with the smallest Euclidean distance to the target material in the encoded vector space

- Recipe Completion: Adapting precursors from the reference material to the target, with conditional prediction of any missing elements [2]

This approach demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in historical validation, achieving at least 82% success rate when proposing five precursor sets for each of 2,654 unseen test target materials [2]. The system captures nuanced chemical relationships, such as the tendency of certain precursor pairs (e.g., nitrates like Ba(NO₃)₂ and Ce(NO₃)₃) to be used together due to properties like solubility and compatibility with solution processing [2].

Autonomous Optimization Algorithms

Beyond static recommendation, autonomous algorithms like ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) implement active learning approaches that iteratively improve precursor selection based on experimental outcomes [1]. The algorithm:

- Initially ranks precursor sets by thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target

- Proposes testing at multiple temperatures to map reaction pathways

- Identifies intermediates using XRD with machine-learned analysis

- Updates precursor rankings to avoid reactions that form highly stable intermediates

- Prioritizes precursor sets that maintain large driving force even after intermediate formation [1]

In benchmark testing, ARROWS3 identified all effective synthesis routes for YBa₂Cu₃O₆.₅ (YBCO) while requiring substantially fewer experimental iterations than black-box optimization methods [1]. This demonstrates the value of incorporating domain knowledge (thermodynamics and pairwise reaction analysis) into optimization algorithms.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Precursor Selection Methods

| Method | Approach | Key Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity-Based Recommendation [2] | Machine-learned materials similarity from text-mined recipes | 82% success rate on 2,654 test materials | Captures human heuristics, interpretable | Limited to historical precedents |

| ARROWS3 Optimization [1] | Active learning with thermodynamic analysis | Identifies all effective precursors with fewer iterations | Adapts to experimental results, handles metastable targets | Requires experimental validation |

| Black-Box Optimization [1] | Generic algorithms without domain knowledge | Requires more iterations to identify effective precursors | General-purpose application | Less efficient for materials synthesis |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Building a Synthesis Knowledge Base from Literature

Purpose: Extract structured synthesis recipes from scientific literature to enable data-driven precursor recommendation.

Materials and Data Sources:

- Full-text permissions from major scientific publishers (Springer, Wiley, Elsevier, RSC, etc.)

- Computational resources for NLP processing (GPU recommended for deep learning models)

- Text annotation tools for manual validation (e.g., Brat Rapid Annotation Tool)

Procedure:

- Literature Collection: Download full-text publications in HTML/XML format published after year 2000 [6]

- Paragraph Identification: Classify paragraphs as synthesis procedures using keyword probability analysis

- Entity Recognition: Implement BiLSTM-CRF model with

token replacement to identify targets and precursors [6] - Operation Extraction: Apply Latent Dirichlet Allocation to cluster synonyms into operation categories (mixing, heating, etc.)

- Stoichiometric Balancing: Compile balanced chemical reactions including atmospheric gasses

- Quality Validation: Manually review random sample of extracted recipes (recommended: 100+ paragraphs)

Validation: In a test of 100 randomly selected solid-state synthesis paragraphs, approximately 70% yielded complete extraction with balanced chemical reactions [6].

Protocol: Implementing Precursor Recommendation for Novel Targets

Purpose: Recommend precursor sets for synthesizing a novel target material using historical data.

Materials:

- Knowledge base of historical synthesis recipes (minimum 10,000 recipes recommended)

- Composition of target material

- Encoding model (e.g., PrecursorSelector encoding [2])

Procedure:

- Encode Target Material: Process target composition through encoding network to generate vector representation

- Similarity Calculation: Compute Euclidean distance between target vector and all materials in knowledge base

- Reference Identification: Select reference material with smallest distance to target

- Precursor Adaptation: Extract precursors from reference material and adjust for target stoichiometry

- Element Completion: If elements are missing, predict additional precursors using conditional probability models

- Ranking: Generate multiple precursor sets (recommended: 5 options) with success probability estimates

Validation: The recommendation strategy achieved 82% success rate when proposing five precursor sets for 2,654 unseen test materials [2].

Visualization of NLP-Driven Synthesis Workflows

NLP-Driven Synthesis Workflow

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Text-Mined Synthesis Databases | Structured knowledge base for training models | 29,900 solid-state recipes [2], 31,782 solid-state and 35,675 solution-based recipes [6] |

| Materials Encoding Models | Convert materials to vector representations for similarity calculation | PrecursorSelector encoding [2], Word2Vec [21] |

| Thermodynamic Data | Calculate driving force for reactions | Materials Project DFT calculations [1] |

| Autonomous Optimization Algorithms | Iteratively improve precursor selection based on experimental outcomes | ARROWS3 [1] |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Advanced information extraction through prompt engineering | GPT, BERT, Falcon [21] |

Critical Considerations and Future Directions

While NLP approaches show significant promise for autonomous precursor selection, several critical considerations must be addressed:

Data Limitations: Text-mined synthesis datasets often suffer from limitations in volume, variety, veracity, and velocity [6]. These limitations stem from both technical extraction challenges and inherent biases in how chemists have historically explored materials spaces.

Ethical Implementation: When applying similar NLP approaches to clinical research recruitment, studies have identified significant gaps in addressing ethical considerations like patient autonomy and equity [22]. Similar ethical reflection should be incorporated into materials science applications.

Domain Adaptation: Pre-trained general language models often lack the specificity required for intricate materials science tasks [21]. Effective implementation typically requires fine-tuning on domain-specific corpora to capture specialized terminology and relationships.

Future advancements will likely involve greater integration of NLP with autonomous research platforms, where recommendation systems are coupled with robotic synthesis and characterization to create fully closed-loop materials discovery systems [2] [1]. As NLP methodologies continue to evolve, particularly with the development of more sophisticated large language models, the capacity to extract nuanced synthesis knowledge from literature will further enhance our ability to predict and optimize precursor selection for novel materials.

The synthesis of novel inorganic solid-state materials is a cornerstone for developing new technologies, from superconductors to advanced battery components. However, the path from a target material's composition to its successful synthesis is often non-trivial, traditionally relying on domain expertise, heuristic rules, and extensive empirical testing. This process is hampered by the formation of stable intermediate phases that consume the thermodynamic driving force, preventing the formation of the desired target material. To address this core challenge in materials science, researchers have developed Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis (ARROWS3), an algorithm designed to automate and optimize the selection of precursors for solid-state synthesis [1] [23].

ARROWS3 represents a significant shift from black-box optimization methods by strategically incorporating physical domain knowledge—specifically, thermodynamic data and pairwise reaction analysis—into an active learning loop [1] [24]. This framework is critical for the development of fully autonomous research platforms, enabling more efficient materials discovery and development, a goal that resonates with professionals in drug development and pharmaceutical research who utilize similar model-informed approaches [8] [25]. This protocol provides a detailed examination of the ARROWS3 framework, its operational mechanisms, experimental validation, and practical implementation guidelines.

Core Principles and Algorithmic Methodology

The ARROWS3 algorithm is built upon the fundamental principle that the selection of precursor materials dictates the reaction pathway and the likelihood of successfully synthesizing a high-purity target material. Its logical flow is designed to mimic the reasoning of an expert chemist, but at a scale and speed enabled by computational power and automation.

Theoretical Foundation

Solid-state synthesis outcomes are profoundly influenced by the competition between the formation of the target phase and the formation of unwanted, often highly stable, intermediate byproducts. These intermediates can consume reactants and reduce the thermodynamic driving force available for the target material's nucleation and growth [1]. ARROWS3 operates on two key hypotheses derived from domain knowledge:

- Pairwise Reactions: Solid-state reactions often proceed through step-by-step transformations involving two phases at a time [1] [8].

- Driving Force Maximization: Intermediate phases that leave only a small driving force (i.e., small change in Gibbs free energy, ΔG) to form the target material should be avoided, as they can halt the reaction or require prohibitively long reaction times and high temperatures [1] [8].

The algorithm's objective is to actively identify and avoid precursor combinations that lead to such unfavorable intermediates, thereby prioritizing synthesis routes that retain a large thermodynamic driving force throughout the reaction pathway.

The ARROWS3 Workflow Logic

The algorithm follows a structured, iterative process that integrates computation, experiment, and learning. The workflow, illustrated in the diagram below, can be broken down into several key stages.

Step 1: Initial Precursor Ranking. Given a target material and a list of potential precursors, ARROWS3 first enumerates all precursor sets that can be stoichiometrically balanced to yield the target's composition. In the absence of prior experimental data, these sets are initially ranked by the thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target directly from the precursors, computed using formation energies from databases like the Materials Project [1] [24]. Precursor sets with the largest (most negative) ΔG are ranked highest, as they are theoretically the most reactive.

Step 2: Experimental Proposal and Execution. The highest-ranked precursor sets are proposed for experimental testing. Crucially, each set is tested across a range of temperatures (e.g., 600°C to 900°C). This provides "snapshots" of the reaction pathway, revealing the sequence of phase formation at different stages [1].

Step 3: Reaction Pathway Analysis. The products from each heating experiment are characterized, typically using X-ray diffraction (XRD). Machine-learning-assisted analysis is then used to identify the crystalline phases present in the product, including any intermediate phases [1] [8]. ARROWS3 uses this data to reconstruct the pairwise reactions that occurred.

Step 4: Active Learning from Outcomes. This is the core learning step. When an experiment fails to produce the target, ARROWS3 identifies which pairwise reactions led to the formation of stable intermediates. It calculates the driving force consumed by these side reactions. This information is stored in a growing database of observed pairwise reactions [8].

Step 5: Re-ranking and Subsequent Proposal. The algorithm then re-evaluates the remaining untested precursor sets. It uses its database of observed reactions to predict whether a given precursor set is likely to form the known, unfavorable intermediates. Precursor sets predicted to avoid these kinetic traps are promoted in the ranking, as they are expected to retain a larger effective driving force (ΔG′) to form the target in the later stages of the reaction [1]. The loop (Steps 2-5) continues until the target is synthesized with sufficient yield or all viable precursor sets are exhausted.

Experimental Validation and Performance

The ARROWS3 framework has been rigorously validated on several experimental datasets, encompassing over 200 distinct synthesis procedures [1] [24]. Its performance has been benchmarked against black-box optimization algorithms like Bayesian optimization and genetic algorithms.

Benchmarking on YBa₂Cu₃O₆.₅ (YBCO)

A comprehensive dataset was built specifically for validating ARROWS3 by testing 47 different precursor combinations in the Y–Ba–Cu–O chemical space at four synthesis temperatures (600–900 °C), resulting in 188 individual experiments [1].

Table 1: Synthesis Outcomes for YBCO from 188 Experiments [1]

| Outcome Category | Number of Experiments | Percentage of Total |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity YBCO (No prominent impurities) | 10 | 5.3% |

| Partial Yield of YBCO (With byproducts) | 83 | 44.1% |

| Failed to Produce YBCO | 95 | 50.5% |

This dataset highlighted the difficulty of synthesis, with only a small fraction of experiments directly leading to high-purity targets under the used conditions (4-hour hold time). In this challenging search space, ARROWS3 demonstrated superior efficiency by identifying all effective precursor sets for YBCO while requiring substantially fewer experimental iterations compared to black-box optimization methods [1].

Synthesis of Metastable Targets

ARROWS3 was also successfully applied to synthesize metastable materials, which are often more sensitive to the selection of precursors and conditions.

- Na₂Te₃Mo₃O₁₆ (NTMO): This compound is metastable with respect to decomposition into Na₂Mo₂O₇, MoTe₂O₇, and TeO₂. ARROWS3 guided the selection of precursors that avoided these stable decomposition products, leading to the successful synthesis of NTMO with high purity [1].

- Triclinic LiTiOPO₄ (t-LTOPO): This polymorph has a tendency to undergo a phase transition to a more stable orthorhombic structure (o-LTOPO). ARROWS3 identified a synthesis route that avoided this transformation, successfully stabilizing the metastable triclinic phase [1].

Integration in an Autonomous Laboratory (A-Lab)

The practical power of ARROWS3 is demonstrated by its integration into the A-Lab, a fully autonomous materials discovery platform. In a landmark study, the A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 of 58 novel target compounds over 17 days of continuous operation [8]. The active-learning cycle of ARROWS3 was responsible for identifying synthesis routes with improved yield for nine of these targets, six of which had zero yield from initial literature-inspired recipes [8]. The algorithm's use of observed pairwise reactions allowed it to reduce the search space of possible synthesis recipes by up to 80% by inferring the products of some recipes without testing them [8].

Table 2: ARROWS3 Performance vs. Black-Box Optimization

| Algorithm Feature | ARROWS3 | Black-Box Optimization (e.g., Bayesian) |

|---|---|---|

| Domain Knowledge | Explicitly incorporated (Thermodynamics, Pairwise reactions) | Not incorporated |

| Handling Discrete Variables | Effective at selecting from categorical precursor choices | Challenging, better suited for continuous parameters |

| Data Efficiency | High; identifies optimal precursors in fewer experiments [1] [24] | Lower; typically requires more experimental iterations |

| Interpretability | High; decisions are based on interpretable physical principles | Low; operates as an opaque "black box" |

| Learning Transfer | Learned pairwise reactions can inform other synthesis targets [8] | Learning is typically specific to the single target |

Detailed Protocols for Implementation

This section provides a detailed methodology for implementing the ARROWS3 framework, either within an automated platform or a traditional laboratory setting.

Protocol 1: Initial Precursor Selection and Ranking

Objective: To generate an initial, thermodynamically informed ranking of precursor sets for a given target material.

Materials and Reagents:

- Target material composition.

- List of candidate precursor compounds (typically common oxides, carbonates, nitrates, etc.).

- Computational access to a thermochemical database (e.g., Materials Project [1] [8]).

Procedure:

- Stoichiometric Enumeration: For the target composition, generate all possible combinations of two or more precursors from the candidate list that can be stoichiometrically balanced to yield the target.

- Free Energy Calculation: For each balanced precursor set, calculate the reaction energy (ΔG) to form the target from the precursors. This is typically done using DFT-calculated formation energies from the Materials Project database at a standard state (e.g., 0 K or 298 K) [1] [24].