Automating Materials Science: Advanced Data Extraction Techniques for Research and Drug Development

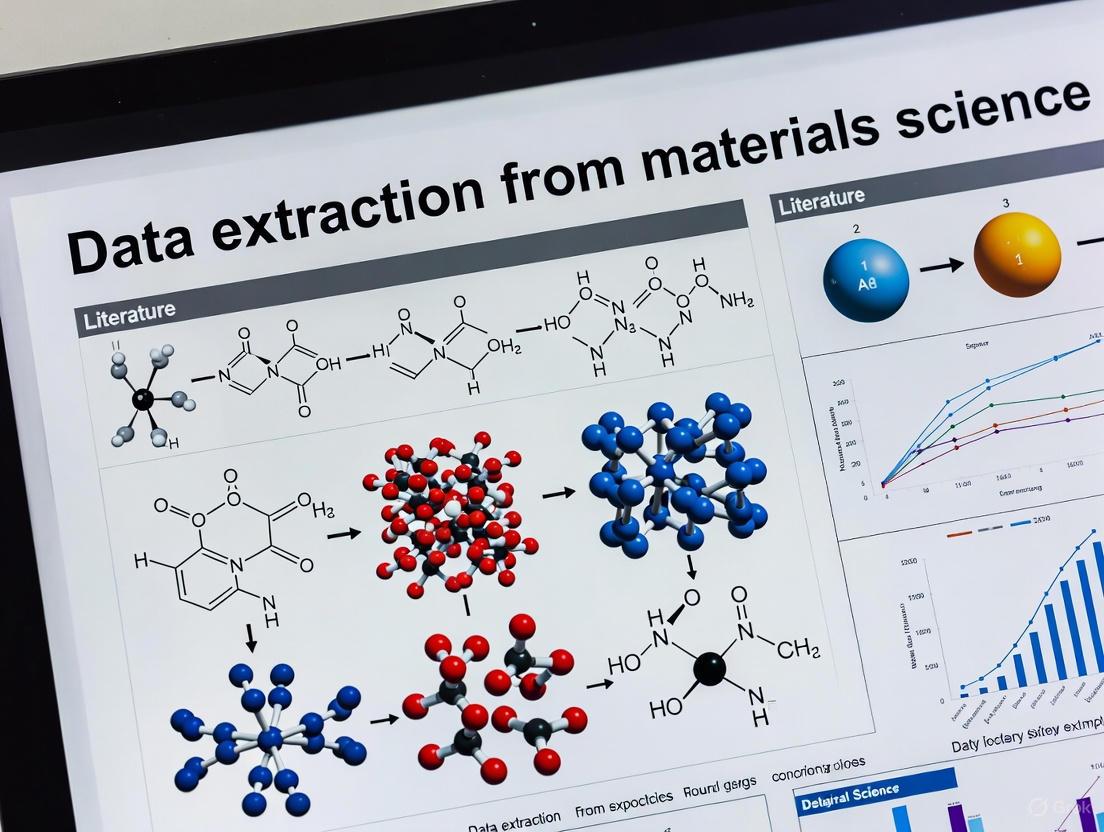

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern data extraction methodologies applied to materials science literature, addressing the critical need for automated, large-scale data collection to fuel informatics and discovery.

Automating Materials Science: Advanced Data Extraction Techniques for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern data extraction methodologies applied to materials science literature, addressing the critical need for automated, large-scale data collection to fuel informatics and discovery. We explore the foundational shift from manual extraction to AI-driven approaches using Large Language Models (LLMs) and specialized Natural Language Processing (NLP) models like MaterialsBERT. The scope encompasses practical methodologies, from building extraction pipelines to optimizing performance and cost. We also address significant challenges including data quality, model hallucination, and integration into existing research workflows, and conclude with a comparative analysis of different extraction frameworks and their validation for generating reliable, research-ready databases.

The Data Imperative: Why Automated Extraction is Revolutionizing Materials Science

The rapid expansion of materials science literature has created a vast repository of knowledge, most of which is locked in unstructured formats like PDFs. This poses a significant bottleneck for data-driven research and materials discovery. Automated information extraction (IE) has emerged as a critical field to transform this unstructured text and tabular data into structured, machine-readable databases, thereby accelerating the development of new materials [1] [2]. In materials science, this task is uniquely complex, requiring the accurate capture of the "materials tetrahedron"—the intricate relationships between a material's composition, structure, properties, and processing conditions [3]. This document outlines the specific challenges, quantifies the performance of current extraction methodologies, and provides detailed application protocols for researchers embarking on data curation projects.

The Materials Science Data Landscape

Information in materials science literature is distributed across both text and tables, each presenting distinct extraction challenges. A manual analysis of papers reveals that different types of data favor different formats, as shown in the table below.

Table 1: Prevalence of Key Data Entities in Materials Science Papers [3]

| Data Entity | Reported in Text | Reported in Tables |

|---|---|---|

| Compositions | 78% | 74% |

| Properties | Information Missing | 82% |

| Processing Conditions | 86% | 18% |

| Testing Methods | 84% | 16% |

| Precursors (Raw Materials) | 80% | 20% |

Note: Percentages exceed 100% because the same information can be reported in both text and tables.

A critical finding is that while compositions are frequently mentioned in text, 85.92% of them are actually housed within tables, which are often the primary source for structured data [3]. This underscores the necessity of developing robust methods for parsing tabular data.

Quantified Challenges in Information Extraction

Challenges in Extracting Data from Tables

Tabular data, while structured in appearance, lacks standardization, making automated extraction difficult. The table below categorizes and quantifies these challenges based on an analysis of 100 composition tables.

Table 2: Key Challenges in Extracting Compositions from Tables [3]

| Challenge Category | Specific Challenge | Frequency of Occurrence | Impact on Extraction (F1 Score) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Table Structure | Multi-Cell, Complete Info (MCC-CI) | 36% | 65.41% |

| Single-Cell, Complete Info (SCC-CI) | 30% | 78.21% | |

| Multi-Cell, Partial Info (MCC-PI) | 24% | 51.66% | |

| Single-Cell, Partial Info (SCC-PI) | 10% | 47.19% | |

| Data Provenance | Presence of Nominal & Experimental Compositions | 3% | Difficult to separate correctly |

| Compositions Inferred from External References | 11 tables (of 100) | IE models fail if data is absent | |

| Material Identification | Composition Inferred from Material IDs | 10% of tables | Failure in 60% of these cases |

Performance of Modern Extraction Tools

Recent advances in Large Language Models (LLMs) have enabled new approaches to these challenges. The following table summarizes the performance of different modern data extraction methods as reported in recent studies.

Table 3: Performance of Automated Data Extraction Methods

| Method / Tool | Domain / Task | Reported Performance Metric | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChatExtract (GPT-4) [4] | Bulk Modulus Data Extraction | Precision: ~91%, Recall: ~88% | 90.8% Precision, 87.7% Recall |

| ChatExtract (GPT-4) [4] | Critical Cooling Rates (Metallic Glasses) | Precision: ~92%, Recall: ~84% | 91.6% Precision, 83.6% Recall |

| GPT-4V (Vision) [5] | Polymer Composites - Composition | Accuracy | 0.910 |

| GPT-4V (Vision) [5] | Polymer Composites - Property Name | F₁ Score | 0.863 |

| GPT-4V (Vision) [5] | Polymer Composites - Property Details (Exact Match) | F₁ Score | 0.419 |

| DiSCoMaT (GNN) [3] | Glass Compositions from Tables (MCC-CI) | F₁ Score | 65.41% |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: ChatExtract for Data from Text

The ChatExtract method utilizes a conversational LLM with a series of engineered prompts to achieve high-precision data extraction from text, minimizing the model's tendency to hallucinate information [4].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Source Documents: A corpus of scientific PDFs relevant to the target material property.

- Text Pre-processing Tool: A tool like

pandocor a Python PDF library (e.g.,PyMuPDF) to remove PDF/HTML/XML syntax and split text into sentences. - Conversational LLM Access: API or web interface access to a powerful conversational LLM such as GPT-4 [4].

- Computing Environment: Standard consumer-grade hardware is sufficient for running the pipeline and managing API calls [1].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Text Preparation: Gather relevant papers and convert them to plain text. Divide the full text of each document into individual sentences.

- Stage A - Initial Relevancy Classification:

- Prompt: Submit each sentence to the LLM with a prompt asking if it contains a numerical value and unit for the specific property of interest (e.g., bulk modulus, critical cooling rate).

- Action: Filter and retain only sentences classified as "positive." This step typically reduces the dataset size by two orders of magnitude (a 1:100 ratio of relevant to irrelevant sentences) [4].

- Passage Construction:

- For each positive sentence, create a text passage that includes the paper's title, the sentence immediately preceding the target sentence, and the target sentence itself. This provides crucial context, such as the material name [4].

- Stage B - Data Extraction:

- Step B1: Single vs. Multiple Value Check: Submit the constructed passage to the LLM to determine if it contains a single data point or multiple data points.

- Step B2 - Single-Value Extraction Path: If single, use direct prompts to extract the

Material,Value, andUnitseparately. Prompts must explicitly allow for a "Not Mentioned" response to discourage guessing [4]. - Step B3 - Multi-Value Extraction Path: If multiple, initiate a series of follow-up prompts. This path uses uncertainty-inducing redundant questioning. For example, after an initial extraction, ask: "I think [Material X] has a value of [Value Y] [Unit Z]. Is this correct?" This forces the model to re-analyze and verify its own extraction, significantly improving accuracy [4].

- Data Output: The final extracted data should be structured into a machine-readable format, such as a CSV file, with columns for Material, Value, and Unit.

Protocol B: Multi-Modal LLM for Data from Tables

This protocol describes a method for extracting sample-level information from tables in PDFs using a multi-modal LLM, which has shown superior performance compared to text-only or OCR-based approaches [5].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Source Documents: PDFs of research papers containing tables with target data (e.g., on polymer composites).

- Table Extraction Tools:

- Multimodal LLM: Access to a vision-enabled LLM such as GPT-4 with Vision (GPT-4V) [5].

- Annotation Platform (for validation): A platform like

Label Studiofor creating ground-truth data, requiring two or more human annotators to ensure accuracy [5].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Dataset and Ground Truth Preparation:

- Select a set of papers relevant to your subdomain (e.g., polymer composites).

- For a subset of tables, have at least two human annotators manually extract the ground truth data. This includes identifying samples and their associated composition data (matrix, filler, fraction, surface treatment) and properties (name, value, conditions) [5].

- Table Digitization (Parallel Input Preparation):

- Image Input (Recommended): Take a high-quality screenshot of the entire table, ensuring the caption is included. The visual format preserves structural cues [5].

- Structured Input (CSV): Use a PDF table extraction tool like

ExtractTableto convert the table into a CSV format. This explicitly encodes the table's structure [5]. - Unstructured Input (OCR Text): Use an OCR tool on the table image to get a plain text version. This method often loses structural information [5].

- LLM Prompting and Execution:

- Provide the LLM with detailed instructions for the Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Relation Extraction (RE) tasks. The prompt should specify the exact entities to find and how to associate them.

- Submit the prepared inputs (image, CSV, or OCR text) to the multimodal LLM. Studies have shown that using the image input directly with GPT-4V yields the highest accuracy [5].

- Data Validation and Structuring:

- Compare the LLM's output against the manually created ground truth.

- Calculate performance metrics such as accuracy and F₁ score to gauge the method's effectiveness for your specific dataset.

- Resolve any discrepancies through adjudication or model refinement.

- Export the final, validated data into a structured database or knowledge graph.

Table 4: Key Resources for Materials Data Extraction and Management

| Resource Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| KnowMat [1] | Extraction Pipeline | An accessible, Flask-based web pipeline using lightweight open-source LLMs (e.g., Llama) to extract key materials information from text and save to CSV. |

| ChatExtract [4] | Extraction Methodology | A prompt-engineering protocol for conversational LLMs (e.g., GPT-4) to achieve high-precision data extraction from text with minimal upfront effort. |

| GPT-4 with Vision (GPT-4V) [5] | Multimodal Model | An LLM capable of processing table images directly, outperforming text-based table extraction methods in accuracy for composition and property data. |

| DiSCoMaT [3] | Specialized IE Model | A graph neural network-based model designed specifically for extracting material compositions from complex table structures in scientific papers. |

| MaterialsMine / NanoMine [5] | Data Repository & KG | A framework and knowledge graph for manually and automatically curating experimental data on polymer composites, enabling querying and analysis. |

| Covidence [6] | Systematic Review Tool | A software platform that facilitates dual-reviewer data extraction during systematic literature reviews, helping to manage and reduce errors. |

| ExtractTable [5] | Table Parser | A commercial tool for converting tabular data in PDFs into structured CSV files, providing a clean input for LLMs. |

The expansion of materials informatics is fundamentally constrained by the availability of high-quality, structured data. Much of the critical information on material properties, synthesis, and performance remains locked within unstructured text, tables, and figures of research publications. Automated data extraction technologies are therefore not merely supportive tools but foundational components that power the entire materials discovery pipeline. By transforming unstructured text into computable data, these methods directly fuel the development of machine learning (ML) models and predictive informatics, enabling the accelerated design of polymers, alloys, and energetic materials [7]. This application note details the core protocols and quantitative performance of advanced data extraction techniques that are central to modern materials research and development.

Automated Data Extraction Protocols & Performance

The transition from manual data curation to automated extraction using Large Language Models (LLMs) represents a paradigm shift. The following protocols and their associated performance metrics demonstrate the viability of these methods for building reliable materials databases.

ChatExtract Protocol for Material Property Triplets

The ChatExtract framework is a state-of-the-art method designed to accurately extract material property triplets—(Material, Value, Unit)—from scientific text using conversational LLMs in a zero-shot setting, requiring no prior model fine-tuning [4].

Experimental Workflow:

- Data Preparation: Research papers are gathered and parsed to remove HTML/XML syntax. The text is then segmented into individual sentences.

- Stage A: Initial Relevancy Classification:

- A prompt is applied to every sentence to classify it as relevant or irrelevant for containing the target property data (value and units). This step filters out the vast majority (~99%) of sentences [4].

- The text passage for analysis is expanded to include three key elements: the paper's title, the sentence preceding the relevant sentence, and the relevant sentence itself. This ensures the material name is captured.

- Stage B: Data Extraction & Verification: This stage uses a series of engineered prompts with specific features to ensure accuracy:

- Feature 1: Single vs. Multi-Valued Text Separation: The LLM first determines if the text contains a single data point or multiple values. Separate extraction paths are used for each, as multi-valued sentences are more prone to errors.

- Feature 2: Explicit Allowance for Missing Data: Prompts explicitly allow for "Not mentioned" responses to discourage the LLM from hallucinating data.

- Feature 3: Uncertainty-Inducing Redundant Prompts: Follow-up questions are designed to introduce doubt, prompting the model to re-analyze the text instead of reinforcing a previous incorrect answer.

- Feature 4: Conversational Information Retention: All prompts are embedded in a single conversation, with the full text passage reiterated each time to leverage the model's context retention.

- Feature 5: Strict Yes/No Format: Verification questions are constrained to Yes/No answers to simplify automated processing.

The entire ChatExtract workflow is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of the ChatExtract Method [4]

| Material Property | Test Dataset Description | Precision (%) | Recall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Modulus | Constrained test dataset | 90.8 | 87.7 |

| Critical Cooling Rates | Metallic glasses (full database construction) | 91.6 | 83.6 |

LLM Framework for Processing-Structure-Property Relationship Extraction

Beyond simple property triplets, a more comprehensive LLM framework has been developed to extract complex Processing-Mechanism-Structure-Mechanism-Property (P-M-S-M-P) relationships, particularly from metallurgy literature [8]. This approach systematically maps the causal links that define a materials system.

Experimental Protocol:

- Multi-Stage Prompting: The framework employs a sequence of specialized prompts to deconstruct the text:

- Prompt 1: Identify and list all key entities: properties, microstructures, processing methods, and mechanisms.

- Prompt 2: Label the source of each piece of information (e.g., "the authors state," "it can be inferred").

- Prompt 3: Integrate the entities into a coherent P-M-S-M-P network, establishing the directional links between them.

- Chart Generation & Refinement: The extracted network is processed into a structured data format (e.g., JSON) and then refined into a human- and machine-readable visual chart for easy interpretation.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of the P-M-S-M-P Extraction Framework [8]

| Extraction Task | Accuracy / Performance Metric |

|---|---|

| Mechanism Extraction | 94% Accuracy |

| Information Source Labeling | 87% Accuracy |

| Human-Machine Readability Index (for Processing, Structure, Property entities) | 97% |

The logical flow of the P-M-S-M-P relationship extraction process is shown in Figure 2.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential "research reagents"—the key software, data, and model components—required to implement the automated data extraction workflows described in this note.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Automated Materials Data Extraction

| Item / Solution | Function & Application | Example Implementations / Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Conversational LLM | Core engine for zero-shot text classification, information extraction, and relationship mapping. Powers the ChatExtract and P-M-S-M-P protocols. | GPT-4, other advanced conversational models [4] [8] |

| Engineered Prompts | Pre-defined, optimized instructions that guide the LLM to perform specific tasks without additional training. Critical for achieving high accuracy. | Relevancy classifiers, single/multi-value discriminators, verification prompts [4] |

| Text Pre-processing Pipeline | Prepares raw document data for LLM analysis by handling format stripping, tokenization, and sentence segmentation. | Custom Python scripts for removing XML/HTML and sentence splitting [4] |

| P-M-S-M-P Framework | A structured schema for representing complex, causal materials knowledge, enabling systematic extraction beyond simple properties. | Defined ontology for metallurgy and materials science [8] |

| Scientific Literature Corpus | The source data; a collection of research papers (PDFs or plain text) from which material data and relationships are to be extracted. | Publisher websites, institutional repositories, PubMed Central, etc. |

The field of materials science generates a vast amount of knowledge, yet a critical bottleneck exists: most of this knowledge remains locked within unstructured text in millions of scientific papers. This creates a significant hurdle for data-driven discovery. The traditional process of manual data extraction is notoriously time-consuming and limits the scale of analysis. Natural Language Processing (NLP), particularly through Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Large Language Models (LLMs), is revolutionizing this landscape by enabling the automated, large-scale transformation of unstructured text into structured, actionable databases. This document outlines the core concepts and provides practical protocols for applying these advanced techniques to materials science documents, framing them within the context of an automated data extraction pipeline for research.

Core Conceptual Frameworks

The Evolution of Natural Language Processing (NLP)

NLP aims to enable computers to understand and generate human language. Its development in materials science has progressed through distinct stages:

- Handcrafted Rules (1950s-): Early systems relied on expert-defined rules, which were rigid and could only solve narrow problems [9].

- Machine Learning (Late 1980s-): Algorithms began learning from annotated text corpora, but required manual feature engineering and faced the "curse of dimensionality" [9].

- Deep Learning (Present): Neural networks like BiLSTM and the Transformer architecture automated feature engineering. This era is defined by the rise of LLMs, which possess remarkable general language abilities [9].

Named Entity Recognition (NER)

NER is a fundamental NLP task that involves identifying and classifying key information (entities) in text into predefined categories. In materials science, this typically includes:

- Inorganic material mentions

- Sample descriptors

- Phase labels

- Material properties and applications

- Synthesis and characterization methods [10]

For example, in the sentence "The synthesized CoFe2O4 nanoparticles exhibited a saturation magnetization of 80 emu/g," a NER model would identify "CoFe2O4" as a material, "nanoparticles" as a sample descriptor, and "saturation magnetization of 80 emu/g" as a property-value-unit triplet.

Large Language Models (LLMs)

LLMs are deep learning models trained on immense volumes of text. Their core working principle is token prediction: given a sequence of input tokens (sub-word units), they predict the most probable subsequent tokens [11]. Trained on diverse knowledge areas, they develop a powerful ability to understand context and generate coherent text. For materials science, this means they can interpret complex chemistry language and textual context with a flexibility that rigid, rule-based systems lack [12]. Two key paradigms for using LLMs are:

- Prompt Engineering: Crafting input instructions to guide the model to perform a specific task without additional training (zero-shot or few-shot learning).

- Fine-Tuning: Further training a pre-trained LLM on a specialized dataset (e.g., materials science text) to enhance its performance on domain-specific tasks.

Quantitative Performance of NLP Techniques in Materials Science

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Different Data Extraction Methods on Materials Science Texts.

| Method / Model | Task Description | Reported Performance Metric | Score | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional NER [10] | Entity recognition from abstracts | F1-score | 87% | Establishes baseline for automated extraction |

| ChatExtract (GPT-4) [4] | Extraction of Material-Value-Unit triplets | Precision | 90.8% | Minimal initial effort; high accuracy |

| Recall | 87.7% | |||

| ChatExtract (GPT-4) [4] | Critical cooling rates for metallic glasses | Precision | 91.6% | Effective for practical database construction |

| Recall | 83.6% | |||

| Open-source LLMs (Qwen3, GLM-4.5) [12] | Extraction of synthesis conditions | Accuracy | >90% | Transparency; cost-effectiveness; data privacy |

| Fine-tuned LLM [12] | Prediction of MOF synthesis routes | Accuracy | 91.0% | Demonstrates predictive capability beyond extraction |

| Fine-tuned LLM [12] | Prediction of synthesisability (generalisation) | Accuracy | 97.8% | Strong generalisation beyond training data scope |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Automated Data Extraction Using a Conversational LLM (ChatExtract)

ChatExtract is a method that uses advanced conversational LLMs with sophisticated prompt engineering to achieve high-quality data extraction with minimal upfront effort [4].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

Data Preparation and Pre-processing

- Input: Gather target scientific papers, typically in PDF or XML/HTML format.

- Text Cleanup: Remove all XML/HTML tags and other non-textual syntax.

- Sentence Segmentation: Split the clean text into individual sentences. This is a standard step in any data extraction pipeline [4].

Stage (A): Initial Relevancy Classification

- Objective: Filter out sentences that do not contain the target data (e.g., Material-Value-Unit triplets), drastically reducing the number of sentences for costly detailed analysis.

- Prompt Engineering: Apply a simple prompt to every sentence to classify it as "relevant" or "irrelevant." In papers pre-filtered by a keyword search, the ratio of relevant to irrelevant sentences can be as high as 1:100, making this step crucial for efficiency [4].

- Context Expansion: For each sentence classified as relevant, create a text passage comprising the paper's title, the preceding sentence, and the target sentence itself. This often captures the material name and improves context.

Stage (B): Data Extraction and Verification

- Single-Value vs. Multi-Value Path: The first prompt in this stage determines if the text passage contains a single data point or multiple data points. This is critical because multi-valued texts are more prone to extraction errors.

- For Single-Value Texts: Use direct prompts to ask separately for the material name, value, and unit. The prompt must explicitly allow for a negative answer (e.g., "not mentioned") to discourage the model from hallucinating data [4].

- For Multi-Value Texts: Employ a rigorous series of follow-up prompts. This strategy includes:

- Uncertainty-Inducing Prompts: Phrasing questions to suggest the model's previous answer might be wrong, encouraging re-analysis instead of confirmation bias.

- Redundant Verification: Asking the same question in different ways to cross-verify the extracted data.

- Strict Yes/No Format: Enforcing a strict format for answers to reduce ambiguity and simplify automated parsing [4].

- Output Structuring: The final prompts encourage the model to output the data in a structured format (e.g., JSON) for easy conversion into a database.

Protocol 2: Fine-Tuning an LLM for Domain-Specific Prediction

This protocol describes how to adapt a general-purpose LLM for specialized tasks, such as predicting material properties or synthesis conditions.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

Dataset Curation

- Objective: Create a high-quality dataset of input-output pairs relevant to the target task.

- Procedure: Using the L2M3 project as an example [12]:

- Input (X): Collect textual descriptions of MOF precursors or rich natural language descriptions containing composition and structural features (e.g., node connectivity, topology).

- Output (Y): Associate these inputs with the corresponding synthesis conditions or property values (e.g., hydrogen storage performance).

- Data Splitting: Split the dataset into training and validation sets (e.g., 85%/15%) for model development and evaluation [12].

Fine-Tuning Execution

- Model Selection: Choose a suitable pre-trained open-source model (e.g., from the Llama, Qwen, or GLM families).

- Efficient Fine-Tuning: Use parameter-efficient methods like Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA). LoRA freezes the pre-trained model weights and injects trainable rank-decomposition matrices into the transformer layers, significantly reducing the number of trainable parameters and computational cost [12].

- Hardware Configuration: The required computational resources depend on the model size. For example, fine-tuning a large model like GLM-4.5-Air may require four AMD Instinct MI250X accelerators, which can be reduced to two with 4-bit quantization at a minor cost to accuracy [12].

Validation and Deployment

- Performance Benchmarking: Evaluate the fine-tuned model on the held-out validation set. Metrics like accuracy or similarity scores are used to compare its performance against baselines, such as closed-source models like GPT-4o [12].

- Application: Deploy the validated model as a "recommender" tool within a research pipeline to suggest synthesis parameters for new precursors or predict properties of unreported materials.

Table 2: Essential Tools, Models, and Datasets for Materials Science Data Extraction Research.

| Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Feature / Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatNexus [13] | Software Suite | Automated collection, processing, and analysis of scientific articles. | Generates ML-ready vector representations and visualizations for materials exploration. |

| MatSci-NLP [14] | Benchmark Dataset | Standardized evaluation of NLP models on materials science tasks. | First comprehensive benchmark; covers property prediction, information extraction, etc. |

| HoneyBee [14] | Domain-Specific LLM | A large language model fine-tuned for materials science. | Achieves state-of-the-art performance on MatSci-NLP; uses automated instruction tuning. |

| MOF-ChemUnity [12] | Extraction Pipeline | Information extraction for Metal-Organic Frameworks. | Links material names to co-reference names and crystal structures, forming a knowledge graph. |

| ChatExtract [4] | Extraction Method | A workflow for accurate data extraction using conversational LLMs. | Requires minimal initial setup; achieves >90% precision/recall with GPT-4. |

| Open-source LLMs (Qwen, GLM) [12] | Foundational Models | General-purpose and fine-tunable models for various tasks. | Commercially competitive; offer transparency, cost-control, and data privacy. |

| L2M3 [12] | Recommender System | Predicts synthesis conditions based on provided precursors. | Demonstrates the predictive power of fine-tuned LLMs within the materials domain. |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Hypothesis Generation: LLMs can move beyond data extraction to generate novel, synergistic materials design hypotheses by integrating scientific principles from diverse sources. For instance, they can propose new high-entropy alloys with superior cryogenic properties or solid electrolytes with enhanced ionic conductivity, ideas that have been validated by subsequent high-impact publications [15].

Multi-Agent Systems: LLMs are increasingly deployed as the central "brain" in autonomous research systems. These LLM agents can plan multi-step procedures, interface with computational tools (e.g., simulation software), and even operate robotic platforms in self-driving labs, closing the loop from hypothesis to experimental validation [12] [16].

Multimodal Data Extraction: Advanced pipelines now use multimodal LLMs that can interpret both text and images. For example, the "ReactionSeek" workflow directly interprets reaction scheme images from publications to extract synthetic pathways, achieving high accuracy and broadening the scope of accessible data [12].

The vast body of knowledge in materials science is embedded within unstructured scientific literature. A significant portion of this knowledge can be structured as simple triplets: a Material, a Property, and a Value [4]. The systematic extraction of these (Material, Property, Value) triplets from research papers is a fundamental step in building structured databases that enable large-scale, data-driven research and the development of predictive models [17]. This process transforms isolated facts reported in text into a structured, computable format, forming the backbone of modern materials informatics.

Traditionally, the extraction of this data has relied on manual curation or partial automation requiring significant domain expertise and upfront effort. The emergence of advanced Large Language Models (LLMs) represents a paradigm shift, offering a pathway to automate this extraction with high accuracy and minimal initial setup [4] [17]. This document outlines the core concepts of these data triplets and provides a detailed protocol for their automated extraction using state-of-the-art conversational LLMs.

Core Concepts and Definitions

The (Material, Property, Value) triplet is a concise representation of a single quantitative material characteristic.

- Material: The substance or compound under investigation. This can range from a simple element (e.g., "steel") to a complex, multi-component system (e.g., "high-entropy alloy AlCoCrFeNi").

- Property: The specific, measurable attribute of the material being reported. Examples include "bulk modulus," "yield strength," "critical cooling rate," and "band gap."

- Value: The numerical measurement of the property, accompanied by its relevant Unit (e.g., "156 GPa," "83.6 %," "4.5 K"). The unit is an indispensable component of a complete data point.

Table of Common Data Triplets in Materials Science

The following table summarizes exemplary triplets to illustrate the concept.

| Material | Property | Value & Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Metallic Glass | Critical cooling rate | 87.7 K/s |

| High-Entropy Alloy | Yield strength | 1.31 GPa |

| Gorilla (Older) | Chest-beating rate | 0.91 beats per 10 h [18] |

| Gorilla (Younger) | Chest-beating rate | 2.22 beats per 10 h [18] |

Experimental Protocol: Automated Triplet Extraction with ChatExtract

The ChatExtract method is a fully automated, zero-shot approach for extracting (Material, Property, Value) triplets from research papers using conversational LLMs and prompt engineering. It achieves high precision and recall (both close to 90% with models like GPT-4) by leveraging a structured conversational workflow to minimize hallucinations and extraction errors [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

This protocol relies on the following key components:

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Conversational LLM (e.g., GPT-4) | The core engine for natural language understanding and data extraction. Its information retention across a conversation is critical. |

| Set of Engineered Prompts | Pre-defined, sequential instructions that guide the LLM through identification, extraction, and verification steps. |

| Python Runtime Environment | For executing the automated workflow, handling API calls to the LLM, and processing input/output texts. |

| Corpus of Research Papers | Input data; PDFs converted to plain text and segmented into sentences or short passages. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The ChatExtract method consists of two main stages. The following diagram outlines the complete, automated workflow.

Stage A: Initial Relevancy Classification

- Input Preparation: Gather research papers and convert them to plain text, removing any XML/HTML syntax. Segment the text into individual sentences [4].

- Relevancy Filtering: Apply a simple prompt to all sentences to classify them as relevant or irrelevant. A relevant sentence is one that contains data for the property of interest (i.e., a value and its units). This step efficiently weeds out the vast majority of sentences (typically a 1:100 ratio of relevant to irrelevant) [4].

- Example Prompt: "Does the following sentence from a materials science paper contain a numerical value and a unit for the property '[PROPERTY NAME]'? Answer only 'Yes' or 'No'. Sentence: '[SENTENCE]'"

- Text Passage Expansion: For each sentence classified as positive, create a short text passage for deeper analysis. This passage consists of three elements: the paper's title, the sentence immediately preceding the target sentence, and the target sentence itself. This expansion helps capture the material name, which is often mentioned outside the immediate target sentence [4].

Stage B: Data Extraction & Verification

This stage uses a series of engineered prompts applied within a single conversational thread with the LLM to maintain context.

- Single vs. Multiple Value Determination: The first prompt in Stage (B) asks the model to determine if the text passage contains a single data value or multiple data values. This is a critical branching point, as the extraction strategy differs for each [4].

- Example Prompt: "Does the following text contain only one single value for the property '[PROPERTY NAME]'? Answer only 'Yes' or 'No'. Text: '[TEXT PASSAGE]'"

- Path 1: Extraction from Single-Value Texts:

- For texts containing a single value, directly ask a series of simple, separate prompts to extract the material name, the numerical value, and the unit.

- Key Feature: Explicitly allow for a negative answer to discourage the model from hallucinating data that isn't present [4].

- Example Prompts:

- "What is the numerical value for the [PROPERTY NAME] in the text? If no value is given, answer 'None'. Text: '[TEXT PASSAGE]'"

- "What is the unit for this value? If no unit is given, answer 'None'. Text: '[TEXT PASSAGE]'"

- "What is the name of the material this value refers to? If no material is named, answer 'None'. Text: '[TEXT PASSAGE]'"

- Path 2: Extraction from Multi-Value Texts:

- Texts with multiple values are more prone to errors. Use a strategy of purposeful redundancy and uncertainty-inducing follow-up prompts [4].

- First, ask the model to extract all data points.

- Then, for each extracted piece of data, ask a follow-up verification question that suggests uncertainty, prompting the model to re-analyze the text instead of reinforcing a previous error.

- Example Verification Prompt: "I think the value X for material Y might be incorrect. Could you double-check if the text actually states this? Answer only 'Yes' or 'No'. Text: '[TEXT PASSAGE]'"

- Output Structuring: Enforce a strict format for the LLM's final answers (e.g., JSON) to simplify automated post-processing into a structured database [4].

Key Technical Features for Success

The high accuracy of the ChatExtract protocol is enabled by several key technical features [4]:

- Information Retention: All prompts are embedded within a single conversation, allowing the LLM to retain context from previous questions and answers.

- Uncertainty-Inducing Redundancy: The use of follow-up questions that introduce doubt forces the model to re-analyze the text, overcoming the tendency to confabulate.

- Structured Yes/No Format: Restricting answers to a binary format for verification questions reduces ambiguity and simplifies automation.

- Explicit Allowance for Missing Data: Prompting the model with options like "If not present, answer 'None'" significantly reduces hallucinations.

The (Material, Property, Value) triplet is a fundamental unit of structured knowledge in materials science. The ChatExtract protocol provides a robust, automated, and transferable method for extracting these triplets from scientific text with minimal initial effort. By leveraging advanced conversational LLMs and sophisticated prompt engineering, this approach enables the rapid construction of high-quality materials databases, accelerating the pace of data-driven materials discovery and design.

The field of materials science is experiencing a data revolution, with the overwhelming majority of materials knowledge published as peer-reviewed scientific literature. This literature contains invaluable information on material compositions, synthesis processes, properties, and performance characteristics. However, this knowledge repository exists primarily in unstructured formats, creating a significant bottleneck for large-scale analysis. The prevalent practice of manually collecting and organizing data from published literature is exceptionally time-consuming and severely limits the efficiency of large-scale data accumulation, creating an urgent need for automated materials information extraction solutions [9].

The challenge is particularly acute in materials science due to the technical specificity of the terminology and the complex, heterogeneous nature of the information presented. Recent progress in natural language processing (NLP) has provided tools for high-quality information extraction, but these tools face significant hurdles when applied to scientific text containing specific technical terminology. While substantial efforts in information retrieval have been made for biomedical publications, materials science text mining methodology is still at the dawn of its development, presenting both challenges and opportunities for researchers in the field [19].

The Technical Framework: NLP and LLMs

The Evolution of Natural Language Processing

Natural Language Processing (NLP) has evolved significantly since its inception in the 1950s, progressing through three distinct developmental stages. The field began with handcrafted rules based on expert knowledge, which could only solve specific, narrowly defined problems. The machine learning era emerged in the late 1980s, leveraging growing volumes of machine-readable data and computing resources, though it faced challenges with sparse data and the curse of dimensionality. The current deep learning era utilizes neural network architectures like bidirectional long short-term memory networks (BiLSTM) and the Transformer model, which forms the core of modern large language models [9].

The fundamental objective of NLP is to enable computers to understand and generate text through two principal tasks: Natural Language Understanding (NLU), which focuses on machine reading comprehension via syntactic and semantic analysis, and Natural Language Generation (NLG), which involves producing phrases, sentences, and paragraphs within a given context [9].

Key Technological Foundations

Several technological breakthroughs have been instrumental in advancing NLP capabilities for scientific text processing:

Word Embeddings: These distributed representations of words enable language models to process sentences and understand underlying concepts. Word embeddings are dense, low-dimensional representations that preserve contextual word similarity, with implementations like Word2Vec and GloVe capturing latent syntactic and semantic similarities among words through global word-word co-occurrence statistics [9].

Attention Mechanism: First introduced in 2017 as an extension to encoder-decoder models, the attention mechanism allows models to focus on relevant parts of the input sequence when processing data, significantly improving performance on complex language tasks [9].

Transformer Architecture: This architecture, characterized by its self-attention mechanism, serves as the fundamental building block for modern large language models (LLMs) and has been employed to solve numerous problems in information extraction and code generation [9].

Large Language Models in Materials Science

The emergence of pre-trained models has ushered in a new era in NLP research and development. Large language models (LLMs) such as Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT), Falcon, and Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) have demonstrated general "intelligence" capabilities through large-scale data, deep neural networks, self and semi-supervised learning, and powerful hardware. In materials science, GPTs offer a novel approach to materials information extraction through prompt engineering, distinct from conventional NLP pipelines [9].

Table: Key Large Language Model Architectures Relevant to Materials Science

| Model Architecture | Key Characteristics | Applications in Materials Science |

|---|---|---|

| Transformer | Self-attention mechanism | Fundamental building block for LLMs |

| BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) | Bidirectional context understanding | Information extraction from scientific text |

| GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) | Generative capabilities | Materials information extraction via prompt engineering |

| Falcon | Open-source LLM | Specialized materials science applications |

Quantitative Analysis of Text Mining Scale and Performance

The scale of the text processing challenge in materials science can be understood through both volume considerations and performance metrics of current extraction methodologies.

Volume and Processing Metrics

Materials informatics represents a rapidly growing field, with the revenue of firms offering MI services forecast to reach US$725 million by 2034, representing a 9.0% compound annual growth rate (CAGR). This growth is driven by increasing recognition of the value of data-centric approaches for materials research and development [20].

Table: Text Mining Performance Metrics in Scientific Literature Processing

| Performance Metric | Current Capability | Target/Advanced Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Concept Extraction Accuracy | Approximately 80% or higher in many cases [21] | Approaching individual human annotator performance [21] |

| Information Extraction Tasks | Named entity recognition, relationship extraction [9] | Autonomous knowledge discovery [9] |

| Critical Error Reduction | Identification of prevalent errors through systematic analysis [21] | Implementation of writing guidelines to minimize processing errors [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Large-Scale Text Processing

Protocol: Automated Materials Data Extraction Pipeline

Objective: To automatically extract structured materials information from unstructured scientific text at scale.

Materials and Methods:

- Document Collection and Preprocessing

- Collect target materials science publications in PDF format through API access to repositories or manual upload.

- Convert PDF documents to plain text using high-fidelity text extraction tools.

- Clean and normalize text through tokenization, sentence segmentation, and removal of non-content elements.

Named Entity Recognition (NER)

- Implement domain-specific NER models to identify materials science entities.

- Utilize pre-trained models (BERT, SciBERT) fine-tuned on materials science corpus.

- Apply conditional random fields (CRF) or deep learning models (BiLSTM) for sequence labeling.

- Target entity types: material compounds, properties, synthesis processes, synthesis parameters, alloy compositions.

Relationship Extraction

- Apply dependency parsing to analyze grammatical structure of sentences.

- Implement rule-based patterns for specific relationship types.

- Utilize supervised learning models to classify relationship types between entities.

- Extract relationships: material-property, process-parameter, composition-property.

Knowledge Base Population

- Map extracted entities to standardized terminologies and ontologies.

- Resolve coreferences within and across documents.

- Normalize numerical values and units to standard representations.

- Store structured information in materials knowledge graph.

Validation:

- Manually annotate gold standard corpus of materials science documents.

- Calculate precision, recall, and F1-score against human annotations.

- Perform cross-validation with existing materials databases.

Protocol: LLM-Powered Information Extraction via Prompt Engineering

Objective: To leverage large language models for materials information extraction through structured prompting.

Materials and Methods:

- Prompt Design

- Develop task-specific prompts with clear instructions and examples.

- Incorporate domain knowledge through few-shot learning examples.

- Structure prompts to output standardized formats (JSON, CSV).

Model Configuration

- Select appropriate LLM (GPT, Claude, or domain-specific models).

- Configure model parameters (temperature, max tokens, top-p).

- Implement error handling for API-based model access.

Output Processing

- Parse structured outputs from model responses.

- Implement validation checks for extracted data.

- Resolve inconsistencies through iterative prompting.

Integration

- Combine LLM extraction with traditional NLP pipelines.

- Implement human-in-the-loop verification for critical data.

- Establish continuous learning from correction feedback.

Visualization of Text Processing Workflows

Materials Science Text Mining Workflow

LLM-Based Extraction Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Materials Science Text Mining

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Text Processing |

|---|---|---|

| NLP Libraries | SpaCy, NLTK, Stanza | Provide foundational NLP capabilities including tokenization, POS tagging, and dependency parsing |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, Hugging Face Transformers | Enable development and fine-tuning of neural network models for sequence labeling and text classification |

| Materials Ontologies | MDO (Materials Design Ontology), ChEBI, CHEMINF | Standardize terminology and enable semantic interoperability across extracted materials data |

| LLM Platforms | OpenAI GPT, Claude, Falcon, BERT variants | Facilitate zero-shot and few-shot information extraction through advanced language understanding |

| Knowledge Graph Systems | Neo4j, Amazon Neptune, Apache Jena | Store and query complex relationships between extracted materials science entities |

| High-Performance Computing | GPU clusters, Cloud computing platforms | Provide computational resources for training and inference with large models and datasets |

Best Practices for Optimized Text Processing

Writing Guidelines for Machine-Readable Research Articles

Based on comprehensive analysis of prevalent errors in automated concept extraction, researchers can enhance the machine-readability of their publications through several straightforward practices:

Clearly associate gene and protein names with species: Automated systems for identifying genes and proteins must determine the species first. Directly stating the species significantly reduces potential for error, especially the first time a gene or protein is mentioned [21].

Supply critical context prominently and in proximity: Like human readers, text-mining systems use surrounding context to resolve ambiguous words and phrases. Context should be provided in the abstract and preferably in the same sentence as ambiguous concept names [21].

Define abbreviations and acronyms: All abbreviations and acronyms should be listed with the corresponding full term the first time they are used to minimize ambiguity [21].

Refer to concepts by name: While descriptive language has value, names provide important advantages for automated tools as they have simpler structure, less variation, and are easier to match against controlled vocabularies [21].

Use one term per concept consistently: Using multiple terms interchangeably without clear indication that they should be considered equivalent can confuse both human readers and text-mining systems [21].

Implementation Considerations for Large-Scale Processing

Successful deployment of text mining systems for materials science requires attention to several critical implementation factors:

Domain Adaptation: Pre-trained NLP models typically perform better on general text than scientific text, necessitating domain adaptation through fine-tuning on materials science corpora [19].

Handling of Numerical Data and Units: Materials science literature contains extensive numerical data with units, requiring specialized processing capabilities for accurate extraction and normalization [9].

Multi-modal Integration: Modern materials research often combines textual information with images, graphs, and tables, requiring integrated approaches that can process multiple information modalities [9].

Scalability and Performance: Processing millions of documents requires distributed computing approaches and efficient algorithms that can scale with growing literature volumes [20].

The efficient processing of millions of journal articles represents both a formidable challenge and tremendous opportunity for accelerating materials discovery. The scale of this problem necessitates automated approaches that can transform unstructured textual information into structured, computable knowledge. Current NLP technologies and emerging LLM capabilities provide powerful tools to address this challenge, though significant work remains to achieve human-level comprehension and reliability. As these technologies continue to mature and domain-specific adaptations improve performance, automated text processing will increasingly become an indispensable component of the materials research infrastructure, enabling more rapid discovery and innovation through comprehensive utilization of the collective knowledge embedded in the scientific literature.

Building Your Pipeline: From LLMs to Specialized Models for Maximum Extraction

The acceleration of materials discovery is heavily dependent on the ability to transform unstructured knowledge from scientific literature into structured, actionable data. Within this context, the selection of an appropriate natural language processing (NLP) model—whether a versatile large language model (LLM) like GPT or LlaMa, or a specialized domain-specific BERT model—becomes a critical strategic decision. This application note provides a comparative analysis of these model families, supported by quantitative benchmarks and detailed experimental protocols, to guide researchers in developing efficient data extraction pipelines for materials science documents.

Model Architectures and Characteristics

Domain-Specific BERT Models (e.g., MaterialsBERT, MatSciBERT) are transformer-based models that undergo continued pre-training on specialized scientific corpora. For instance, MatSciBERT is initialized from SciBERT and further trained on approximately 150,000 materials science papers, yielding a corpus of ~285 million words [22]. This domain-adaptive pre-training allows the model to develop expertise in materials science nomenclature and concepts.

Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT and LlaMa represent a different approach. These are fundamentally autoregressive models trained on massive general-domain corpora through next-token prediction. Their strength lies in their ability to perform tasks through prompt-based instruction following without task-specific fine-tuning. The GPT series has evolved from GPT-3.5 to GPT-4, with the latter demonstrating significantly improved reliability, creativity, and ability to handle nuanced instructions [23].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from a comprehensive study that extracted polymer-property data from ~681,000 full-text articles [24]:

Table 1: Performance comparison of models on polymer data extraction tasks

| Model | Model Type | Key Performance Characteristics | Computational Requirements | Primary Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MaterialsBERT | Domain-specific BERT | Foundation for extracting >1M property records from polymer literature [24] | Lower computational cost for inference [24] | Superior entity recognition in materials science texts [25] [22] |

| GPT-3.5 | Commercial LLM | Effective for data extraction with few-shot learning [24] | Significant monetary costs for API calls [24] | Strong performance without task-specific training [24] |

| LlaMa 2 | Open-source LLM | Competitive performance in extraction tasks [24] | High energy consumption and hardware demands [24] | Transparent, customizable, no data privacy concerns [12] |

Recent benchmarks on data extraction tasks for metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have shown that open-source models like Qwen and GLM can achieve accuracies exceeding 90%, with the largest models reaching 100% on specific extraction tasks [12]. Meanwhile, domain-specific BERT models consistently demonstrate a 1-12% performance improvement over general-purpose BERT models on named entity recognition tasks in materials science [25].

Experimental Protocols for Materials Data Extraction

Two-Stage Filtering Pipeline for LLM Deployment

The following protocol outlines an optimized workflow for extracting materials property data from full-text journal articles using a combination of filtering techniques and extraction models [24]:

Step 1: Corpus Assembly and Pre-processing

- Collect full-text journal articles from authorized publishers (Elsevier, Wiley, Springer Nature, ACS, RSC)

- Identify domain-relevant documents through keyword searching (e.g., "poly" for polymer science)

- Split documents into paragraph-level text units for processing

Step 2: Heuristic Filtering

- Develop property-specific keyword lists for target properties (e.g., "glass transition temperature," "tensile strength")

- Filter paragraphs containing these property mentions or co-referents

- Approximately 11% of paragraphs typically pass this initial filter [24]

Step 3: Named Entity Recognition (NER) Filtering

- Apply a materials-aware NER model (e.g., MaterialsBERT) to identify entities

- Retain only paragraphs containing complete entity sets: material name, property name, property value, and unit

- Approximately 3% of original paragraphs typically contain extractable records [24]

Step 4: Data Extraction

- Apply selected extraction model (BERT-based or LLM) to filtered paragraphs

- For LLMs, use few-shot learning with carefully crafted examples

- Extract and structure property data into standardized format

Step 5: Validation and Data Export

- Implement consistency checks using domain knowledge

- Export structured data to databases or knowledge graphs

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Two-stage filtering pipeline for efficient data extraction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key resources for implementing materials science data extraction pipelines

| Resource | Type | Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Scholar | Database | Public repository of extracted polymer-property data | Available at polymerscholar.org [24] |

| MatSciBERT | Pre-trained Model | Materials domain language model for NER and relation classification | HuggingFace: m3rg-iitd/matscibert [22] |

| MaterialsBERT | Pre-trained Model | NER model derived from PubMedBERT for materials science | Available through referenced publications [24] |

| Open-source LLMs (LlaMa 2/3) | Pre-trained Model | Transparent alternative to commercial LLMs | Available with appropriate licensing [12] |

| MOF-ChemUnity | Extraction Framework | Specialized workflow for MOF information extraction | Code repository available [12] |

The choice between GPT, LlaMa, and domain-specific BERT models depends on several project-specific factors:

Select Domain-Specific BERT Models when:

- The primary task involves named entity recognition from scientific text [25] [22]

- Computational resources or API costs are a significant constraint [24]

- Maximum performance on domain-specific texts is required without extensive prompt engineering [26]

Select Commercial LLMs (GPT series) when:

- Rapid prototyping without task-specific training is preferred [11]

- The extraction task requires complex reasoning across sentences [24]

- Budget allows for API costs and the task benefits from state-of-the-art performance [23]

Select Open-source LLMs (LlaMa series) when:

- Data privacy and reproducibility are primary concerns [12]

- Customization through fine-tuning is required [12]

- The project has computational resources for local deployment [24]

For large-scale extraction projects, a hybrid approach often delivers optimal results. The two-stage filtering protocol described in this document enables researchers to leverage the precision of domain-specific BERT models for candidate identification while utilizing the robust extraction capabilities of LLMs for final processing. This approach maximizes extraction quality while controlling computational costs [24]. As the field evolves, the increasing capability of open-source models presents promising opportunities for more accessible and reproducible materials science data extraction [12].

Protocol 1: The Core ChatExtract Workflow for Automated Data Extraction

1.1 Workflow Overview The ChatExtract methodology is a fully automated, zero-shot approach for extracting materials data from research papers. It leverages advanced conversational Large Language Models (LLMs) through a series of engineered prompts to achieve high-precision data extraction with minimal initial effort and no need for model fine-tuning [4]. The workflow is designed to overcome key limitations of LLMs, such as factual inaccuracies and hallucinations, by implementing purposeful redundancy and uncertainty-inducing questioning within a single, information-retaining conversation [4].

1.2 Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Action: Gather target research papers, remove HTML/XML syntax, and divide the text into individual sentences [4].

- Output: A clean, sentence-segmented corpus of text from the literature.

Step 2: Initial Relevance Classification (Stage A)

- Action: Apply a simple prompt to all sentences to classify them as "relevant" or "irrelevant." A relevant sentence is one that contains the target materials property data (a value and its unit) [4].

- Output: A filtered list of sentences positively identified as containing data, significantly reducing the dataset for further processing.

Step 3: Contextual Passage Assembly

- Action: For each positively classified sentence, assemble a short text passage comprising the paper's title, the sentence preceding the target sentence, and the target sentence itself [4].

- Rationale: This ensures the material's name, often found in the preceding sentence or title, is included for forming complete data triplets [4].

Step 4: Data Extraction and Verification (Stage B)

- Action 4.1: Single vs. Multi-Valued Text Classification: Use a prompt to determine if the passage contains a single data point or multiple values. This dictates the subsequent extraction path [4].

- Action 4.2a: Extraction from Single-Valued Text: For texts with a single value, directly prompt the LLM to extract the

Material,Value, andUnitseparately. Prompts explicitly allow for a negative answer to discourage hallucination [4]. - Action 4.2b: Extraction from Multi-Valued Text: For complex sentences with multiple values, employ a series of follow-up, uncertainty-inducing prompts. These prompts ask the model to re-analyze the text and verify the correctness of extracted data, ensuring accurate correspondence between materials, values, and units [4].

- Output: Extracted data triplets (

Material,Value,Unit) in a structured format.

1.3 Workflow Visualization The following diagram, generated using Graphviz, illustrates the logical flow of the ChatExtract protocol.

Table 1: Key Features of the ChatExtract Stage B Protocol [4]

| Feature | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Path Splitting | Separate processing for single-valued and multi-valued texts. | Optimizes accuracy by applying simpler extraction to single values and rigorous verification to complex sentences. |

| Explicit Negation | Prompts explicitly allow the model to answer that data is missing. | Actively discourages the model from hallucinating or inventing data to fulfill the task. |

| Uncertainty-Inducing Prompts | Use of follow-up questions that suggest previous answers might be incorrect. | Forces the model to re-analyze the text instead of reinforcing a previous, potentially incorrect, extraction. |

| Conversational Retention | All prompts are embedded within a single, continuous conversation with the LLM. | Leverages the model's inherent ability to retain information and context from earlier in the dialogue. |

| Structured Output | Enforcement of a strict Yes/No or predefined format for answers. | Reduces ambiguity in the model's responses and simplifies automated post-processing of the results. |

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation and Performance Benchmarking

2.1 Experimental Setup for Validation To validate the ChatExtract workflow, performance metrics were obtained through tests on established materials science datasets [4]. The protocol for validation is as follows:

- Datasets: The method was tested on a constrained dataset of bulk modulus data and a practical database construction example for critical cooling rates of metallic glasses [4].

- Model: The tests were performed using advanced conversational LLMs, specifically GPT-4 [4].

- Metrics: Precision and Recall were used as the primary metrics for evaluating performance. Precision measures the percentage of correctly extracted data points out of all extracted points, while Recall measures the percentage of correctly extracted data points out of all extractable points in the text [4].

2.2 Quantitative Performance Results Table 2: ChatExtract Performance on Materials Science Data [4]

| Test Dataset | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | Key Challenge Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Modulus Data | 90.8 | 87.7 | Handling of a standard materials property with varied textual contexts. |

| Critical Cooling Rate (Metallic Glasses) | 91.6 | 83.6 | Practical application in building a specialized database from multiple papers. |

2.3 Comparative Analysis Visualization The performance of ChatExtract can be contextualized by its ability to handle different data complexities. The following diagram models the relationship between data complexity and extraction accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for Implementing ChatExtract

| Item | Function in the ChatExtract Workflow |

|---|---|

| Conversational LLM (e.g., GPT-4) | The core "reagent" that performs the language understanding and reasoning. It is pre-trained and used in a zero-shot manner, eliminating the need for fine-tuning [4]. |

| Engineered Prompt Library | A set of pre-defined, tested prompts for relevance classification, value/unit/material extraction, and verification. These are the specific "protocols" that guide the LLM [4]. |

| Text Pre-processing Script | Software to handle the ingestion of PDFs or XML, clean the text, and perform sentence segmentation, preparing the "raw material" for analysis [4]. |

| Python Wrapper Code | Custom code to automate the conversational interaction with the LLM API, manage the workflow logic, and parse the structured outputs into a database [4]. |

| NoSQL Database (e.g., MongoDB) | A flexible database system recommended for storing the final structured data triplets and associated metadata, accommodating the schema-less nature of extracted data [27]. |

The exponential growth of scientific literature presents a formidable challenge for researchers in materials science and drug development, where critical information remains locked within unstructured text. Automated information extraction systems are essential to transform this textual data into structured, actionable knowledge. The Dual-Stage Filtering Pipeline addresses this challenge by integrating the complementary strengths of Heuristic models and Named Entity Recognition (NER) systems. This architecture is specifically designed to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of extracting complex scientific entities—such as material compositions, processing parameters, and microstructure details—from extensive document collections. By deploying a sequential filtering mechanism, the pipeline maximizes throughput while maintaining high precision, making it particularly suited for building large-scale materials databases essential for machine learning and data-driven discovery [28] [9].

In materials science, the relationship between composition, processing, microstructure, and properties is foundational. Traditional single-pass extraction methods often struggle to capture these complex, interdependent relationships accurately. The proposed dual-stage architecture systematically processes documents to first broadly identify potential entities of interest before applying more nuanced, context-aware validation. This approach significantly reduces the computational burden of applying deep, resource-intensive NER models to entire corpora while simultaneously improving the reliability of the final extracted data [28]. The integration of this pipeline into materials informatics workflows enables researchers to rapidly synthesize experimental findings across thousands of publications, accelerating the discovery and optimization of novel functional materials, including those for pharmaceutical applications [9] [29].

Pipeline Architecture and Workflow

The dual-stage filtering architecture operates through a sequential, hierarchical process designed to efficiently sift through large document sets. The workflow ensures that only the most relevant text segments undergo computationally intensive deep learning analysis, optimizing both speed and accuracy.

Stage 1: Heuristic Filtering

The first stage employs rule-based heuristic models to perform coarse-level document triage and information identification. This layer utilizes:

- Pattern Matching: Regular expressions and lexical patterns specific to materials science terminology (e.g., chemical formulas, measurement units) to identify candidate text spans.

- Syntactic Rules: Grammar-based rules that capture common construction patterns for reporting scientific data (e.g., "X was synthesized at Y°C").

- Knowledge-Based Filters: Domain-specific dictionaries and ontologies containing known material names, synthesis methods, and property descriptors [30] [31].

The heuristic stage acts as a high-recall sieve, rapidly identifying text segments containing potential entities of interest while filtering out irrelevant content. This significantly reduces the volume of text that progresses to the more computationally expensive second stage.

Stage 2: Neural NER Processing

The second stage applies sophisticated deep learning models to the candidate text segments identified in Stage 1, performing precise entity recognition and classification:

- Model Architecture: Utilizes a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory network with Conditional Random Fields (BiLSTM-CRF) that effectively captures contextual dependencies in scientific text [31].

- Contextual Embeddings: Incorporates pre-trained word embeddings from scientific corpora (e.g., trained on PubMed abstracts and full-text articles) to enhance domain understanding [31].

- Entity Classification: Precisely classifies and tags entities using the IOB (inside, outside, beginning) format, distinguishing entity types and boundaries with high accuracy [31].

This staged approach creates a synergistic effect where the heuristic model ensures broad coverage while the neural NER model provides precise extraction, together achieving performance superior to either method applied independently.

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow of the dual-stage filtering pipeline:

Dual-Stage Filtering Pipeline Workflow

Experimental Protocols

Data Preparation and Annotation

Implementing the dual-stage filtering pipeline requires meticulous data preparation to ensure optimal model performance:

- Corpus Selection: Utilize established biomedical and materials science corpora including:

- Annotation Scheme: Apply IOB (Inside, Outside, Beginning) tagging format with entity-specific labels (e.g., B-CHEM, I-CHEM, B-DISEASE, I-DISEASE) [31]

- Text Preprocessing: Implement sentence segmentation, tokenization, and part-of-speech tagging using specialized scientific text processing tools [30]

- Embedding Generation: Initialize with domain-specific word embeddings pre-trained on large-scale scientific literature (e.g., 23 million PubMed abstracts) using skip-gram models with 200 dimensions and window size of 5 [31]

Model Training Protocol

The training procedure involves sequential optimization of both pipeline stages:

- Heuristic Model Development:

- Pattern Extraction: Manually curate 500-1,000 representative sentences from target domain to identify common syntactic patterns

- Rule Formulation: Develop context-free grammar rules for materials science expressions

- Dictionary Construction: Compile domain terminologies from established sources (MeSH, ChEBI, Materials Project)

- Recall Optimization: Tune heuristic parameters to achieve >95% recall on development set

- Neural NER Model Training:

- Architecture Configuration: Implement BiLSTM-CRF with 200-dimensional token embeddings and 100-dimensional character embeddings [31]

- Parameter Tuning: Set batch size to 20, dropout rate to 0.5, and utilize stochastic gradient descent with learning rate 0.015 [31]

- Context Window Optimization: Experiment with n-gram window sizes (3,5,7) to capture local context [31]

- Validation: Use 10-fold cross-validation on training corpus to prevent overfitting

- Early Stopping: Monitor performance on development set and halt training after 5 epochs without improvement

Integration and Deployment

The final protocol involves integrating both stages into a unified pipeline:

- API Development: Create RESTful services for each pipeline stage with JSON-based communication

- Processing Orchestration: Implement workflow manager to handle document routing between stages

- Performance Benchmarking: Conduct comparative testing against single-stage baselines (BiLSTM-CRF only, heuristic only)

- Throughput Optimization: Implement batch processing and parallelization for large-scale deployment

Performance Validation and Metrics

Rigorous validation is essential to demonstrate the efficacy of the dual-stage filtering approach compared to traditional single-model extraction systems. Performance is measured using standard information extraction metrics alongside domain-specific evaluation criteria.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes the key performance indicators for evaluating the pipeline's extraction accuracy:

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Information Extraction Pipelines

| Metric | Dual-Stage Pipeline | Single-Stage NER Only | Heuristic Only | Evaluation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | 85.7% [31] | 82.1% [31] | 78.3% [31] | Exact entity match against gold standard |

| Recall | 85.9% [31] | 83.5% [31] | 91.2% [31] | Complete coverage of annotated entities |

| F1-Score | 85.7% [31] | 82.8% [31] | 84.2% [31] | Harmonic mean of precision and recall |

| Throughput | 12.8 docs/sec [28] | 7.2 docs/sec [28] | 24.5 docs/sec [28] | Documents processed per second |

| Tuple Accuracy | 92.3% [28] | 78.6% [28] | 65.2% [28] | Correct extraction of related entity groups |

The dual-stage architecture demonstrates superior performance in balancing accuracy and efficiency, particularly for complex extractions involving interrelated entities (tuples). The heuristic stage's high recall ensures comprehensive candidate generation, while the neural NER stage provides precise classification, resulting in an optimal F1-score exceeding standalone approaches [31].

Materials Science Domain Performance

In specialized materials science applications, the pipeline achieves exceptional results in extracting the complete composition-processing-microstructure-property chain:

Table 2: Performance on Materials Science Extraction Tasks

| Extraction Category | Feature-Level F1 | Tuple-Level F1 | Key Features Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composition | 96.2% [28] | 95.8% [28] | Chemical elements, stoichiometry, doping |

| Processing | 95.7% [28] | 94.3% [28] | Synthesis methods, temperatures, durations |

| Microstructure | 95.0% [28] | 92.4% [28] | Phase identification, grain size, morphology |

| Properties | 96.1% [28] | 95.6% [28] | Mechanical, thermal, electrical properties |

The pipeline's multi-stage design proves particularly advantageous for microstructure information, which is often scattered throughout documents and referenced indirectly. The tuple-level evaluation demonstrates the architecture's capability to maintain contextual relationships between interdependent features, achieving approximately 92-96% accuracy across all materials science categories [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Implementing an effective dual-stage filtering pipeline requires both computational resources and domain knowledge components. The following table details the essential research reagents and computational tools for pipeline development and deployment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Pipeline | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annotation Tools | BRAT [31], Prodigy | Manual corpus annotation | Create gold-standard training data with IOB labels |

| NER Models | BiLSTM-CRF [31], BERT [31] | Entity recognition and classification | Pre-train on scientific corpora for domain adaptation |

| Word Embeddings | PubMed embeddings [31], SciBERT | Semantic representation | 200-dimensional embeddings trained on 23M+ PubMed abstracts |

| Heuristic Resources | Materials ontologies, Regular expressions | Initial candidate generation | Domain-specific patterns for chemical formulas, units |

| Evaluation Frameworks | CoNLL-2003 scorer [31], seqeval | Performance measurement | Precision, recall, F1 for exact and partial matches |

| Processing Libraries | spaCy, NLTK | Text preprocessing | Tokenization, sentence segmentation, POS tagging |

| Domain Corpora | NCBI Disease [31], CDR [31] | Training and testing | 1,500+ articles with chemical/disease annotations |

The toolkit emphasizes components that facilitate domain adaptation, as successful extraction from materials science literature requires specialized resources beyond general-purpose NLP tools. Pre-trained embeddings on scientific corpora are particularly crucial, as they capture the unique semantic relationships in technical literature, significantly improving entity recognition accuracy compared to general domain embeddings [31].

The relationship between pipeline components and performance outcomes can be visualized as follows:

Toolkit Components and Performance Relationships