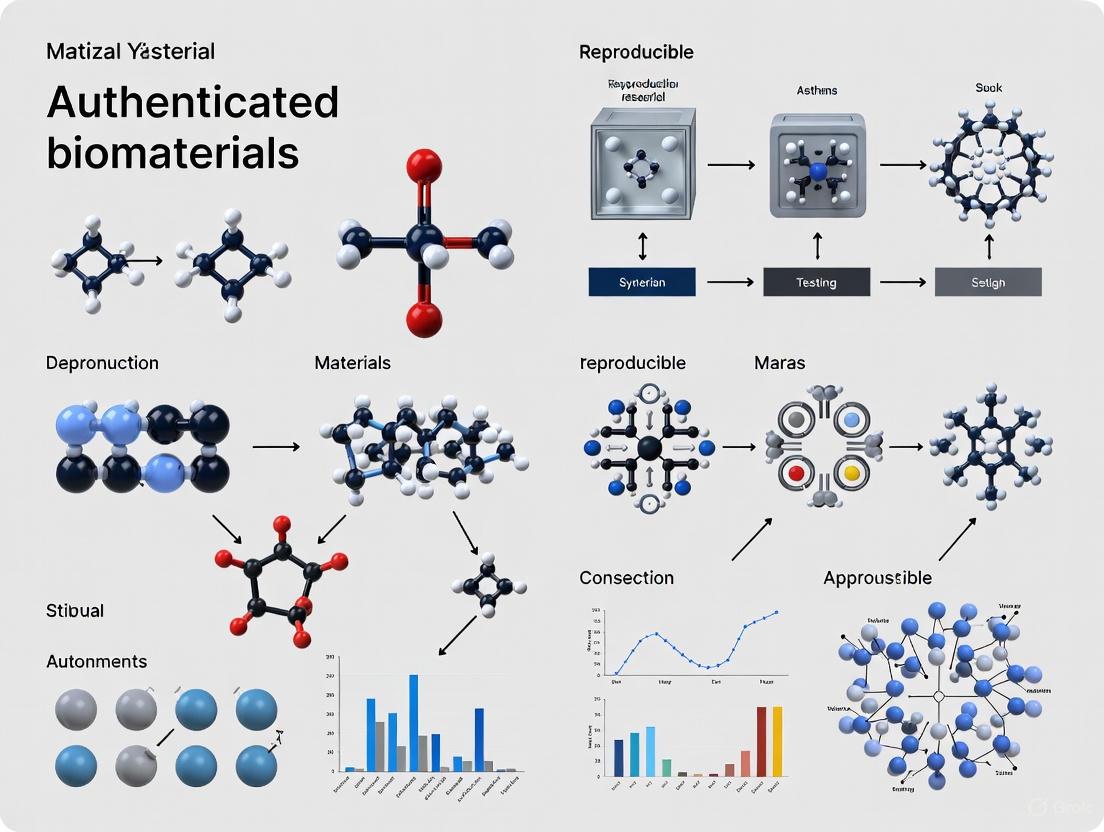

Authenticated Biomaterials: The Foundation of Reproducible Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of biomaterial authentication in ensuring scientific reproducibility.

Authenticated Biomaterials: The Foundation of Reproducible Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of biomaterial authentication in ensuring scientific reproducibility. It explores the foundational need for authentication, details current methodological standards and novel approaches like real-time cell analysis, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, and offers a framework for the comparative validation of new materials. By synthesizing established protocols with emerging 2025 trends, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to enhance the reliability and impact of their biomedical research.

Why Authentication Matters: The Critical Link Between Biomaterial Integrity and Reproducible Science

The integrity of biomedical research relies on the authenticity of fundamental research tools. Unauthenticated biomaterials, particularly cell lines, introduce uncontrolled variables that compromise experimental results, leading to a cascade of irreproducibility that invalidates findings, wastes resources, and misdirects drug development pipelines [1]. Surveys indicate that over 70% of researchers have been unable to reproduce others' experiments, and more than half have failed to reproduce their own work [2] [3]. This article details the quantitative costs of this crisis and provides standardized protocols for cell line authentication to safeguard research validity.

The Scale and Impact of the Problem

Documented Prevalence and Financial Costs

The use of misidentified (MI) or cross-contaminated (CC) cell lines is an endemic problem in biomedical research [1]. The International Cell Line Authentication Committee database lists nearly 500 misidentified human cell lines, a concern for decades [4]. The financial impact is staggering, with one report estimating that $28 billion annually is spent on irreproducible preclinical research in the United States alone [3]. Specific cases highlight the severity; two contaminated cell lines invalidated approximately $700 million in research and 7,000 publications [4].

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Unauthenticated Research Materials

| Documented Issue | Scale of Impact | Financial and Scientific Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Misidentified Human Cell Lines | Nearly 500 cell lines listed in ICLAC database [4] | Wasted research funding, retracted publications, invalidated conclusions [1] [4] |

| Irreproducible Preclinical Research | >50% of studies [3] | Estimated $28 billion per year in the U.S. [3] |

| Specific Contaminated Cell Line Cases | 2 historic cell lines | ~$700M in research and 7,000 publications invalidated [4] |

| Landmark Study Reproducibility (Psychology) | ~39%-64% replication rate [5] | Erosion of public trust, misinformed policy [5] |

| Industry Target Validation (Bayer) | 43 of 67 projects inconsistent [3] | Project termination, wasted R&D investment [3] |

Broader Implications for Drug Development

The reliance on unauthenticated models permeates and disrupts the entire drug development pipeline. A landmark report from Bayer HealthCare revealed that inconsistencies between published data and in-house validation led to the termination of 43 out of 67 target identification projects [3]. Similarly, Amgen scientists successfully confirmed the findings of only 6 out of 53 landmark oncology publications [3]. Such failures misdirect resources, delay therapies, and ultimately increase the cost and risk of bringing new drugs to market.

Standardized Authentication Protocols

Defining Authentication: Identity, Purity, and Phenotype

Cell line authentication is a multi-faceted process that must assess three key properties to ensure a model is valid and fit-for-purpose [1]:

- Identity (Authenticity): Genotypic analysis to establish the original source of a cell line.

- Purity (Contamination): Testing for adventitious organisms (e.g., mycoplasma, bacteria) or cross-contamination with another cell line.

- Phenotype (Characterization): Assessment of complex functional traits resulting from genotype and environment.

The following workflow outlines the critical decision points for authenticating cell lines before use in experimentation.

Core Protocol: Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Profiling for Human Cell Lines

Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling is the internationally recognized standard method for authenticating human cell lines. It is based on regions of DNA containing short, repeating sequences that vary in length between individuals [1] [4].

Experimental Protocol

- Principle: PCR amplification of multiple STR loci, followed by capillary electrophoresis to determine the number of repeats at each locus. The resulting numeric profile is a unique identifier for the cell line [1] [4].

- Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from the cell line using a standardized kit. Ensure a minimum concentration of 1-5 ng/µL.

- PCR Amplification: Using a commercially available STR multiplex kit, amplify 8 core STR loci plus the amelogenin gender marker.

- Fragment Analysis: Separate PCR products by capillary electrophoresis on a genetic analyzer.

- Data Analysis: Software converts electropherogram data into a numeric STR profile for each locus.

- Comparison: Compare the test profile to the STR profile of the reference cell line from a trusted database (e.g., ATCC, DSMZ). A match requires identical alleles at all loci, allowing for minor, defined variations due to genetic drift.

- Quality Control: Include a positive control from a well-characterized cell line. A negative control must be included to rule out contamination.

Protocol for Mouse Cell Line Authentication

The problem of misidentification extends beyond human cell lines. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has patented the first DNA method using specific STR markers to authenticate mouse cell lines [4].

Experimental Protocol

- Principle: Similar to human STR profiling, but uses a panel of 19 mouse-specific STR markers that are highly polymorphic across inbred strains [4].

- Procedure:

- Follow the same core steps for DNA extraction, PCR, and fragment analysis as for human STR profiling, but using mouse-specific primers.

- Compare the resulting STR profile to reference data for the expected mouse strain.

- Note: The Mouse Cell Line Authentication Consortium, established by NIST and ATCC, is working to validate this method and create a public database for mouse cell lines [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Authentication

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| STR Profiling Kit | Multiplex PCR amplification of core STR loci for genotypic identification. | Authenticating human cell lines against reference database profiles [1] [4]. |

| Mouse STR Panel | A set of 19 mouse-specific STR markers for genotyping. | Authenticating mouse cell lines and confirming genetic background [4]. |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kit | Detects mycoplasma contamination via PCR, ELISA, or luminescence. | Routine screening for this common, insidious contaminant that alters cell behavior [1]. |

| Isoenzyme Analysis Kit | Determines species of origin based on electrophoretic mobility of enzymes. | Rapid, low-cost initial check for interspecies cross-contamination. |

| Digital Cell Counter & Viability Analyzer | Provides accurate cell counts and viability metrics. | Standardizing culture conditions and ensuring healthy, representative samples for testing. |

| Reference Cell Lines | Certified authentic cell lines obtained from a reputable biorepository (e.g., ATCC). | Essential positive controls for authentication assays and experimental benchmarking. |

Authenticating cell lines and other critical reagents is not an optional best practice but a fundamental requirement for scientifically valid and economically sustainable research. Implementing the standardized protocols and tools outlined in this application note—particularly STR profiling—is a direct and achievable step toward restoring reproducibility, protecting research investments, and ensuring that drug development pipelines are built upon a foundation of reliable science.

Biomaterial authentication is a critical framework encompassing the standardized processes and techniques used to verify the identity, purity, composition, and biological performance of materials intended for biomedical applications. For the purpose of reproducible research, authentication extends beyond simple identification to include comprehensive characterization that confirms a material's properties remain consistent across batches and performs as intended in biological systems. The scope is broad, covering biological entities like cell lines, natural polymers, and increasingly, synthetic materials including polymers and metallic alloys. This verification is fundamental to ensuring that research findings are reliable, translatable, and reproducible [6] [7].

The crisis of reproducibility in biomedical research, highlighted by large-scale efforts failing to validate dozens of studies, underscores the urgent need for rigorous authentication practices [8]. The core principle is that any resource used to generate research data—whether a biological sample or a engineered material—must be defined and verified with precision. This establishes a foundation of trust and enables the scientific community to build upon previous work accurately. Biobanks, as repositories of biological samples and data, operate on this principle, emphasizing that sharing data and biomaterials, grounded in ethical principles, accelerates innovation and reproducibility [6].

Authentication of Cell Lines

Cell lines are foundational tools in biomedical research, yet they are frequently subject to misidentification, cross-contamination, and genetic drift, compromising data integrity on a global scale.

The Problem of Misidentification

An estimated 18 to 36% of popular cell lines are misidentified, leading to widespread irreproducible results, wasted resources, and retracted publications [9]. Misidentification occurs when a cell line is contaminated or replaced by another, more aggressive line. For example, a 2010 paper in Nature Methods was retracted after it was discovered that the majority of their glioma cell lines had been contaminated with HEK cells [9]. The consequences are far-reaching, potentially misguiding entire research fields and delaying clinical translation [10].

Standards and Mandates

In response, major funding agencies and journals have implemented strict authentication requirements. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) requires regular authentication of key biological resources for grant applications [11]. Prominent publishers, including the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) and Nature Publishing Group, now require or strongly recommend cell line authentication for manuscript submission [10] [9]. The International Journal of Cancer rejects approximately 4% of manuscripts due to severe cell line issues [9].

Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling is the internationally recognized gold standard method for authenticating human cell lines, as detailed in the ANSI/ATCC ASN-0002 consensus standard [10] [11]. This method analyzes highly variable regions of the genome to create a unique genetic fingerprint for each cell line.

Table 1: Cell Line Misidentification Statistics and Impacts

| Aspect | Statistic/Example | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence Rate | 18-36% of popular cell lines are misidentified [9] | High probability of using compromised reagents |

| Publication Impact | ~4% of manuscripts to IJC rejected due to cell line issues [9] | Research dissemination halted |

| Notable Case | Retraction in Nature Methods (2010) due to HEK cell contamination [9] | Invalidated findings and wasted effort |

| Financial Cost | Millions in wasted grant funding and research resources [10] | Inefficient use of scientific funding |

Experimental Protocol: Cell Line Authentication via STR Profiling

This protocol outlines the steps for authenticating human cell lines using the gold-standard STR profiling method, consistent with the requirements of major journals and funding agencies [10] [9] [11].

I. Sample Preparation

- Harvesting Cells: Grow cells to 70-80% confluence. Harvest a sufficient number of cells (e.g., 1-5 x 10^6) to yield high-quality genomic DNA (gDNA). For adherent cells, use a gentle trypsinization method.

- DNA Extraction: Extract gDNA using a commercial kit designed for PCR-based applications. The extracted DNA should have an A260/A280 ratio between 1.7 and 2.0, indicating high purity. DNA can be sourced from fresh/frozen cells, dried cell pellets, or pre-extracted gDNA [9].

II. STR Multiplex PCR

- Reaction Setup: Use a commercial STR profiling kit, such as the GlobalFiler kit, which targets 24 STR loci, including the 13 core loci recommended by the ANSI/ATCC standard plus 11 additional markers for superior discrimination [9].

- Amplification: Perform multiplex PCR according to the manufacturer's instructions. This process simultaneously amplifies the target STR regions in a single reaction, making it cost-effective and efficient.

III. Capillary Electrophoresis and Analysis

- Sequencing: Separate the amplified PCR fragments by size using capillary electrophoresis (e.g., on an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer) [9].

- Genotype Assignment: Use specialized software (e.g., GeneMapper) to analyze the electrophoretogram data and assign specific alleles (genotypes) for each STR locus tested. This generates a unique STR profile for the sample.

IV. Data Interpretation and Reporting

- Profile Comparison: Compare the generated STR profile against a known reference profile from a validated cell bank (like ATCC) or a database. For new lines, compare to a donor sample if available.

- Match Calculation: Software calculates a matching percentage. A match of 80% or higher is typically considered authentic [9].

- Reporting: The final authentication report should include an allele table (the STR profile), a peak plot (electropherogram), and the matching percentage. This certificate is often required for publication and grant submissions.

Authentication of Synthetic Polymers

The authentication of synthetic polymeric biomaterials focuses on confirming their chemical composition, physical structure, and functional properties to ensure batch-to-batch consistency and predictable performance in vivo.

The Authentication Paradigm for Polymers

Unlike cell lines, polymers are not identified by a genetic code but by a set of critical quality attributes (CQAs). These include molecular weight, monomer sequence, crystallinity, and thermal properties. Authentication ensures that these CQAs fall within a specified range that has been correlated with a desired biological outcome, such as controlled drug release or optimal tissue integration [12]. The global polymeric biomaterials market, projected to reach USD 169.88 billion by 2029, underscores the economic and clinical importance of these verified materials [12].

A key challenge is that synthetic polymers, while offering tunable and reproducible mechanical properties, can trigger adverse immune responses if not properly characterized and validated for biocompatibility [12]. Therefore, authentication must include an assessment of purity and the absence of toxic residual catalysts or solvents from the synthesis process.

Key Characterization Methods

Polymer authentication relies on a suite of analytical techniques, each probing different material properties.

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC): Also known as Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), this is the primary method for determining the molecular weight distribution and dispersity (Ð) of a polymer batch, which are critical parameters influencing degradation rate and mechanical strength [12].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: NMR (particularly ^1H and ^13C) is used to confirm chemical structure, monomer composition, and end-group fidelity. It can also quantify copolymer ratios and detect residual monomers [12].

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): DSC measures thermal transitions such as the glass transition temperature (Tg) and melting point (Tm). These properties dictate a polymer's state (rigid vs. rubbery) at physiological temperature and its processing conditions [12].

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: FTIR provides a fingerprint of the chemical functional groups present in the polymer, allowing for rapid identification and detection of major chemical changes or contaminations [12].

- In Vitro Degradation Studies: This involves monitoring changes in mass, molecular weight, and mechanical properties, as well as the pH of the incubation medium (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline) over time to confirm the expected degradation profile [12].

Table 2: Key Analytical Techniques for Polymer Authentication

| Technique | Primary Authentication Parameter | Typical Data Output |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | Molecular Weight (Mw, Mn) & Dispersity (Ð) | Chromatogram, Mw, Mn, Ð |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Chemical Structure & Copolymer Ratio | Spectrum with characteristic peaks |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Glass Transition (Tg) & Melting Point (Tm) | Thermogram with Tg and Tm peaks |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) | Functional Groups & Chemical Bonds | Spectrum with absorption bands |

| In Vitro Degradation Study | Mass Loss & Molecular Weight Change | Degradation profile over time |

Authentication of Metallic Alloys

For metallic biomaterials, authentication verifies composition, microstructure, mechanical properties, and surface characteristics, which are paramount for performance in load-bearing implants like joint replacements and bone plates.

Authentication Parameters for Metallic Alloys

The focus for metallic alloys is on properties that ensure long-term structural integrity and biocompatibility in the harsh physiological environment.

- Elemental Composition: Verification of the alloy's composition (e.g., Ti-6Al-4V, 316L stainless steel) using techniques like Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) or Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS/EDX). This confirms the presence of alloying elements and the absence of toxic impurities [13].

- Microstructure and Phase Analysis: X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) is used to identify the crystalline phases present in the alloy, which directly influence its mechanical strength and corrosion resistance [13].

- Mechanical Property Testing: Authentication includes tensile testing to confirm yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, and modulus of elasticity, ensuring they meet ASTM or ISO standards for specific implant applications [13].

- Surface Characterization and Biofunctionalization: The surface is the interface with biological tissue. Analysis of surface topography (via Atomic Force Microscopy or profilometry), chemistry (via X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy), and the presence of bioactive coatings (e.g., hydroxyapatite) is a crucial part of authentication [13]. Recent advances also focus on bioabsorbable metallic alloys (e.g., based on magnesium or iron), whose authentication must also include controlled corrosion rates [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A curated set of tools and resources is vital for implementing a robust biomaterial authentication strategy.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Biomaterial Authentication

| Tool/Resource | Function in Authentication | Example Providers/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| STR Profiling Kit | Amplifies STR loci for genetic fingerprinting of human cell lines | Thermo Fisher GlobalFiler Kit [9] |

| Reference Databases | Provides standard STR profiles for comparison of cell lines | ATCC, Cellosaurus, ICLAC Table of Misidentified Lines [10] [11] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides standardized materials for calibrating instruments for polymer/metal analysis | National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kit | Detects common bacterial contamination in cell cultures | PCR-based or bioluminescence kits [10] |

| Bioabsorbable Alloy Standards | Provides reference for composition and properties of new-generation metallic implants | ASTM/ISO Standards (e.g., for Mg alloys) [13] |

The need for authenticating biomaterials spans the entire spectrum from biological to synthetic entities. The underlying goal is universal: to ensure that the materials used in research are precisely what they are claimed to be, with defined and consistent properties. This is the bedrock of scientific rigor, reproducibility, and ultimately, successful clinical translation.

Future progress hinges on the development of a more unified framework. This includes leveraging artificial intelligence to mine existing literature and establish clearer, computationally tractable definitions for complex concepts like biocompatibility [7]. Furthermore, the adoption of unique Research Resource Identifiers (RRIDs) for key reagents, including specific polymer formulations and metallic alloys, would enhance traceability and reproducibility across scientific publications [10]. As the field moves towards more complex, smart, and hybrid materials, a comprehensive and standardized approach to authentication will be the key to building trustworthy and translatable biomedical science.

The credibility of biomedical research is fundamentally linked to the integrity of its core reagents. An estimated 50% of biological research data is irreproducible, with a significant portion of this irreproducibility attributed to poor biological materials [14]. The use of misidentified, cross-contaminated, or unauthenticated biomaterials, such as cell lines and microorganisms, remains an endemic problem that invalidates experimental results and wastes invaluable research resources [1] [15]. Regulatory agencies and scientific publishers have responded to this crisis by implementing mandates that require researchers to authenticate key biological resources. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols to help researchers navigate the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines and journal authentication policies, ensuring that their work meets the stringent standards required for reproducible science. Adherence to these policies is no longer a best practice but a fundamental requirement for funding and publication.

NIH Authentication Guidelines

The NIH requires grant applicants to describe methods for ensuring the identity and validity of key biological and/or chemical resources used in the proposed study [16]. This authentication plan must be based on accepted practices in the relevant field and include the frequency of authentication and considerations for stability over long-term use.

- Scope: The plan should focus on established resources that are critical to the proposed project and are known to vary in quality between suppliers or batches. Standard laboratory reagents (e.g., buffers) do not require inclusion [16].

- Objective Evidence: Applicants must provide a plan that demonstrates, through objective evidence, that the resources are what they are claimed to be.

- Page Limit: While no page limit is officially specified, a concise one-page description is typically recommended [16].

Revised NIH Public Access Policy

Effective July 1, 2025, the revised NIH Public Access Policy mandates that all NIH-funded articles accepted for publication on or after this date must be made publicly accessible in PubMed Central (PMC) without embargo upon publication [17].

- Submission Requirement: Authors must submit the Author's Accepted Manuscript (the final peer-reviewed version) to PMC upon its acceptance for publication.

- Immediate Public Access: The manuscript must be made publicly available on PMC without any embargo period starting from the official date of publication [17].

- Compliance Method: Submission to PMC remains free for authors. While publishing open access is an option, it is not required for compliance [17].

Journal Authentication Policies

Leading scientific journals increasingly require experimental data to be generated using authenticated materials. These policies often explicitly reference standards such as the ANSI/ATCC ASN-0002 standard for STR profiling of human cell lines [18].

- Standardization: Journals rely on consensus standards developed by organizations like ATCC, which is an ANSI-accredited Standards Development Organization (SDO) [18].

- Material Authentication: Policies typically mandate authentication of cell lines, microorganisms, and other key biologics upon receipt, at regular intervals during maintenance, and at the start of new projects.

- Reporting: Authors are expected to clearly describe authentication methods and results in their manuscripts, often in the Materials and Methods section.

Quantitative Landscape of the Reproducibility Challenge

The following tables summarize the core quantitative data related to the irreproducibility problem, its financial impact, and the prevalence of poor practices, providing a evidence-based rationale for the mandated policies.

Table 1: The Scope and Financial Impact of Irreproducible Research

| Factor | Statistic | Source / Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Irreproducible Biological Data | ~50% | [14] |

| Researchers Unable to Reproduce Others' Experiments | >70% | [15] |

| Researchers Unable to Reproduce Their Own Experiments | ~60% | [15] |

| Annual Cost of Non-Reproducible Preclinical Research | $28 Billion | [14] [15] |

| Estimated Total Waste in Biomedical Research Expenditure | Up to 85% | [15] |

Table 2: Prevalence and Impact of Unauthenticated Biological Materials

| Problem | Consequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Use of misidentified or cross-contaminated cell lines | Renders scientific conclusions potentially invalid; widespread endemic problem. | [1] [15] |

| Serial passaging of cell lines | Leads to variations in gene expression, growth rate, and phenotype. | [15] |

| Microbial contamination (e.g., Mycoplasma) | Can significantly alter experimental results and outcomes. | [18] [15] |

| Long-term serial passaging of microorganisms | Changes in physiology, virulence, and antibiotic resistance. | [15] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Biomaterial Authentication

Protocol 1: Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Profiling for Human Cell Line Authentication

This protocol is the international gold standard for authenticating human cell lines, as defined by the ANSI/ATCC ASN-0002 standard [18] [1].

I. Principle STR profiling analyzes highly polymorphic regions of DNA containing short, repetitive sequences. PCR amplification of multiple STR loci followed by fragment analysis generates a unique genetic fingerprint for each cell line, which can be compared to reference profiles to confirm identity [1].

II. Materials and Reagents

- DNA Extraction Kit: For genomic DNA isolation (e.g., DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit).

- STR PCR Amplification Kit: Commercially available multiplex kits containing primers for core STR loci (e.g., Promega PowerPlex 16HS or Applied Biosystems AmpFℓSTR Identifiler).

- Thermal Cycler

- Capillary Electrophoresis System (e.g., ABI 3500 Genetic Analyzer)

- Analysis Software (e.g., GeneMapper)

- Reference STR Profiles: Available from repositories like ATCC or the original donor.

III. Step-by-Step Workflow

- DNA Extraction: Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from a cell pellet. Quantify DNA concentration and assess purity (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8).

- PCR Amplification:

- Set up PCR reactions according to the kit's instructions using 1-2 ng of template DNA.

- Cycling conditions: Initial denaturation (95°C for 2 min); followed by 30 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 30 s), annealing (60°C for 30 s), extension (72°C for 90 s); and a final extension (60°C for 45 min).

- Capillary Electrophoresis:

- Dilute the PCR product as recommended.

- Combine with internal size standard and Hi-Di formamide.

- Denature at 95°C for 3 min and snap-cool on ice.

- Load onto the genetic analyzer for fragment separation.

- Data Analysis:

- Use analysis software to determine allele sizes (number of repeats) at each locus.

- Compile the allele calls into the cell line's STR profile.

- Interpretation and Comparison:

- Compare the generated profile to the known reference profile.

- A match requires identical allele calls at all loci. Any discrepancy indicates a misidentification.

- Report the percentage match and the passage number of the tested cells.

Protocol 2: Microbial Authentication and Contamination Screening

This protocol ensures species-level identity and detects common contaminants in cell cultures and microbial strains.

I. Principle Species-level identification is achieved via DNA barcoding using conserved genomic regions like the mitochondrial Cytochrome C Oxidase Subunit 1 (CO1) gene for animal cells or the 16S rRNA gene for bacteria [18]. Contamination from Mycoplasma, Acholeplasma, Spiroplasma, and Ureaplasma is detected via highly sensitive PCR assays [18].

II. Materials and Reagents

- DNA Extraction Kit

- PCR Master Mix

- Species-Specific or Contaminant-Specific Primer Sets

- Gel Electrophoresis Equipment or qPCR System

- Positive Control DNA (for target species/contaminant)

- Negative Control (nuclease-free water)

III. Step-by-Step Workflow

Part A: Species Identification via DNA Barcoding

- DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA.

- PCR Amplification:

- Use universal primers for the CO1 gene (for animal cells) or 16S rRNA gene (for bacteria).

- Perform PCR with standard cycling conditions: Initial denaturation (95°C for 5 min); 35 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 30 s), annealing (50-55°C for 30 s), extension (72°C for 60 s); final extension (72°C for 7 min).

- Sequencing and Analysis:

- Purify PCR products and perform Sanger sequencing.

- Analyze the resulting sequence by comparing it to public databases (e.g., GenBank BLAST) for species-level identification.

Part B: Mycoplasma Detection PCR

- Sample Collection: Use supernatant from cell culture or a direct sample from a microbial culture.

- DNA Extraction.

- PCR Amplification:

- Use a validated primer set that detects over 60 species of Mycoplasma and related genera [18].

- Include a positive control (e.g., M. orale DNA) and a negative control.

- Cycling conditions: Similar to above, with an annealing temperature optimized for the primer set.

- Result Analysis:

- Run PCR products on an agarose gel.

- A band of the expected size in the test sample indicates contamination. Compare to the positive control.

Compliance Workflow: Navigating Mandates from Bench to Publication

The following diagram illustrates the integrated pathway for adhering to authentication mandates throughout the research lifecycle, ensuring compliance with both NIH and journal policies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomaterial Authentication

| Tool / Resource | Function & Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| ATCC Genome Portal (AGP) | Cloud-based database providing high-quality reference genomes from authenticated microbial strains. | ISO 9001-compliant; enables confident bioinformatics analysis and correlation [14]. |

| ATCC Cell Line Land (ACLL) | Reference database for transcriptome (RNA-seq) and exome data from authenticated human and mouse cell lines. | Provides standardized, reference-grade data traceable to physical source materials [14]. |

| STR Profiling Service | Commercial service (e.g., from ATCC) for authenticating human cell lines per the ANSI/ASN-0002 standard. | Provides definitive identity confirmation against a reference database [18]. |

| Mouse STR Profiling Service | Global standard for mouse cell line authentication, developed with NIST. | Addresses the challenge of interspecies cross-contamination and genetic drift [18]. |

| Universal Mycoplasma Detection Kit | PCR-based test to detect over 60 species of common cell culture contaminants. | Provides results in 3-5 days; uses FTA cards for easy sample collection [18]. |

| ANSI/ATCC Standards | Consensus documents (e.g., ASN-0002 for STR profiling) defining authentication methods. | Provide validated, standardized protocols accepted by regulators and publishers [18]. |

Navigating the evolving landscape of NIH and journal mandates is critical for securing funding and achieving publication in high-impact journals. By integrating the detailed protocols and workflows outlined in this document—from rigorous STR profiling and microbial screening to systematic documentation and public access deposition—researchers can systematically address the major sources of irreproducibility. The use of authenticated biomaterials and adherence to these policies are not merely administrative hurdles but are fundamental to conducting rigorous, reliable, and reproducible science that forms a solid foundation for scientific advancement and public trust.

The fields of 3D bioprinting and smart biomaterials represent two of the most transformative frontiers in regenerative medicine and therapeutic discovery. As these technologies advance toward clinical translation, ensuring research reproducibility has become a fundamental requirement rather than a mere technical consideration. An estimated 50% of biological research data is irreproducible, with a significant portion of this irreproducibility linked to problematic biological materials and research methodology [14]. The emergence of complex models—from patient-derived organoids to stimuli-responsive 4D constructs—has heightened the need for robust authentication frameworks that can ensure the fidelity and reliability of these advanced systems [19] [20].

Authentication in this context extends beyond traditional cell line verification to encompass comprehensive characterization of novel biomaterials, bioinks, and the complex multi-cellular environments they support. The scientific community's increasing focus on this issue is reflected in initiatives by major funders like the NIH, which now encourage researchers to describe methods for verifying the identity and purity of biological materials in grant applications [21]. This article details practical protocols and application notes to help researchers integrate rigorous authentication practices into their work with advanced biomaterial systems, thereby enhancing the validity and translational potential of their findings.

Authentication Fundamentals: Principles and Imperatives

The Reproducibility Crisis in Biomedical Research

The reproducibility problem represents a significant challenge across scientific disciplines. A 2016 survey revealed that in biology alone, over 70% of researchers were unable to reproduce other scientists' findings, and approximately 60% could not reproduce their own results [15]. The financial impact is staggering, with estimates suggesting $28 billion per year is spent on non-reproducible preclinical research [15]. This crisis has multiple contributing factors, but the use of unauthenticated or poorly characterized biological materials represents a critical vulnerability in the research workflow [1].

The problem is particularly acute in cell-based research, where misidentified (MI) or cross-contaminated (CC) cell lines remain an endemic issue [1]. Cell lines require constant quality assurance because, as living models, they can change over time through processes such as long-term serial passaging, which can alter gene expression, growth rates, and migration capabilities [15]. Furthermore, contamination by microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, and mycoplasma can compromise experimental outcomes without proper authentication protocols [1].

Defining Authentication for Advanced Biomaterials

In the context of 3D bioprinting and smart biomaterials, authentication encompasses a multi-tiered approach to verification:

- Identity (Authenticity): Analysis of genotype through comparison of DNA profiles to establish the original source of cellular materials. For human cell lines, Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling has emerged as the standard method for confirming identity [1].

- Purity (Contamination): Detection of adventitious organisms (bacteria, fungi, mycoplasma, yeast, viruses) and cross-contamination with other cell lines through a variety of testing methods appropriate to the application [1].

- Phenotype (Characterization): Assessment of complex traits resulting from genotype and environment, including proliferation rates, differentiation capacity, drug sensitivity, and functional properties in 3D environments [1].

- Material Properties Verification: For smart biomaterials, this includes quantification of physical properties such as porosity, stiffness, swelling, degradation, and wettability, which are essential for ensuring scaffold reproducibility and translational relevance [19].

Table 1: Core Authentication Challenges and Solutions in Advanced Biomaterials Research

| Challenge | Impact on Research | Authentication Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Misidentification | Invalidates disease models and therapeutic screening results | STR profiling for human cells; species-specific PCR for others |

| Microbial Contamination | Alters cell behavior and experimental outcomes | Regular mycoplasma testing; sterility verification |

| Phenotypic Drift | Reduces consistency across experiments and between laboratories | Limited passage numbers; functional validation at key endpoints |

| Bioink Batch Variability | Affects printability and biological performance | Pre-printing material characterization; standardized testing protocols |

| 4D Material Response Inconsistency | Compromises dynamic behavior and therapeutic function | Stimuli-response calibration; quantitative characterization |

Authentication in 3D Bioprinting Workflows

Advanced Applications and Authentication Requirements

3D bioprinting has emerged as a leading biofabrication technique for engineering tissues for regenerative medicine and creating microphysiological models for drug screening and personalized medicine [22]. Current research focuses on advanced applications ranging from bone/cartilage organoids to complex tissue interfaces with biochemical heterogeneity [22] [20]. These applications demand sophisticated authentication protocols to ensure their biological relevance and reproducibility.

The construction of bone/cartilage organoids exemplifies the authentication challenges in complex 3D models. These systems require meticulous attention to three vital elements: stem/progenitor cells, ECM-mimetic biomaterials, and fabrication methods [20]. Seed cells including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and embryonic stem cells (ESCs) each present distinct authentication requirements. For example, iPSCs, while offering patient-specific genomic profiles and minimal immunogenicity, face challenges including low reprogramming efficiency, batch variability, and tumorigenic risks that must be addressed through authentication protocols [20].

Protocol: Pre-printing Cell Authentication and Bioink Validation

Objective: To ensure the identity, purity, and functionality of cellular and material components before 3D bioprinting.

Materials:

- Research cell bank (master and working stocks)

- Authentication kits (STR profiling, mycoplasma detection)

- Biomaterial characterization tools (rheometer, FTIR, microscopy)

- Differentiation induction media (lineage-specific)

Procedure:

Cell Identity Verification

- Extract genomic DNA from passage-matched cells (P3-P8 recommended)

- Perform STR profiling using at least 8 core loci for human cells

- Compare resulting DNA profile to reference standards from ATCC or original supplier

- Document all matches/non-matches with percentage similarity

Purity Assessment

- Conduct mycoplasma testing using PCR-based method

- Perform bacterial/fungal culture testing in appropriate media

- For co-culture systems, verify species composition using species-specific PCR

- Document all results with detection thresholds

Bioink Material Characterization

- Quantify bioink rheological properties (viscosity, shear thinning, yield stress)

- Assess mechanical properties (compressive/tensile modulus) of crosslinked samples

- Verify biochemical composition using FTIR or mass spectrometry

- Document batch number and all characterization data

Functional Potency Verification

- For stem cell-containing bioinks, assess differentiation capacity

- Culture samples in lineage-specific induction media (osteogenic, chondrogenic, etc.)

- Quantify differentiation markers (PCR, immunostaining) at defined timepoints

- Compare to positive controls and document differentiation efficiency

Troubleshooting Notes:

- STR profiles with <80% match to reference indicate misidentification – obtain new stock

- Mycoplasma contamination requires elimination treatment and comprehensive re-testing

- Bioinks with significant batch variability require formulation adjustment or rejection

- Poor differentiation capacity may indicate cellular senescence or inappropriate culture conditions

Research Reagent Solutions for 3D Bioprinting

Table 2: Essential Authentication Tools for 3D Bioprinting Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| STR Profiling Kits | Genetic authentication of human cell lines | 8-core loci minimum; compare to reference databases |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kits | Contamination screening | PCR-based for sensitivity; monthly testing recommended |

| ATCC Cell Line Land | Reference transcriptome data | Provides standardized data from authenticated materials |

| Bioink Characterization Kit | Material properties verification | Includes rheology, gelation kinetics, cytotoxicity testing |

| Lineage Differentiation Media | Functional validation of stem cells | Osteogenic, chondrogenic, adipogenic formulations available |

Authentication Strategies for Smart Biomaterials and 4D Systems

The Evolution to 4D Biomaterials

Four-dimensional (4D) printing represents a groundbreaking advancement that introduces the dimension of time into material design and function [23]. While conventional 3D printing creates static biomedical constructs, 4D printing utilizes smart biomaterials that can actively respond to external stimuli—such as temperature, pH, light, or humidity—after fabrication [23]. These materials include shape-memory polymers (SMPs), stimuli-responsive polymers (SRPs), and programmable hydrogels that can undergo reversible or irreversible changes in geometry, stiffness, or porosity in response to physiological cues.

The authentication challenges for 4D systems extend beyond biological components to encompass the material response itself. For example, pH-sensitive polymers containing functional groups that ionize or deionize at specific pH levels must be rigorously characterized for their transformation kinetics and consistency [23]. Similarly, light-responsive materials require verification of their activation thresholds and spatial precision. Without standardized authentication of these dynamic properties, the reproducibility of 4D systems remains compromised.

Protocol: Authentication of Stimuli-Responsive Biomaterials

Objective: To verify the consistent and predictable performance of smart biomaterials under specific environmental cues.

Materials:

- Stimuli-responsive biomaterial (pH-sensitive, thermo-responsive, etc.)

- Environmental control system (pH stat, temperature chamber, light source)

- Real-time monitoring equipment (imaging, sensors)

- Mechanical testing instrumentation

Procedure:

Material Composition Authentication

- Characterize chemical structure using NMR, FTIR, or Raman spectroscopy

- Quantify molecular weight distribution via gel permeation chromatography

- Analyze thermal properties (Tg, Tm) using differential scanning calorimetry

- Document all physicochemical parameters with acceptance criteria

Stimuli-Response Profiling

- Expose material to precise stimulus gradients (pH, temperature, light intensity)

- Quantify response kinetics (transformation rate, lag time, completion time)

- Measure magnitude of response (dimensional change, modulus alteration)

- Establish dose-response relationships for critical parameters

- Document intra-batch and inter-batch variability

Functional Endpoint Verification

- For drug delivery systems: quantify release kinetics under specific stimuli

- For shape-memory materials: measure shape fixation and recovery ratios

- For conductive scaffolds: verify impedance changes under stimulation

- Document performance against pre-established specifications

Biological Response Authentication (for bio-hybrid systems)

- Verify cell viability and functionality during/after material transformation

- Assess inflammatory response in relevant biological models

- Document host integration and tissue remodeling characteristics

Troubleshooting Notes:

- High batch-to-batch variability requires improved synthesis control

- Inconsistent stimuli response may indicate material degradation or formulation issues

- Unpredicted biological responses necessitate additional biocompatibility testing

- Document all deviations from expected performance with root cause analysis

Advanced Tools and Emerging Solutions

Novel Authentication Technologies

The growing recognition of authentication challenges has spurred development of innovative solutions. The ATCC Genome Portal and ATCC Cell Line Land represent significant advances, providing comprehensive genomic data on microbial strains and transcriptome data for human and mouse cell lines [14]. These resources offer reference-grade whole transcriptome data that is authenticated, standard, and traceable to physical source materials, directly addressing gaps in data provenance that contribute to irreproducibility [14].

For complex 3D models, AI-driven data integration is emerging as a powerful tool for enhancing reproducibility. These approaches can optimize culture conditions, analyze large datasets, and minimize batch variability in 3D in vitro models [19]. Similarly, biosensing bioinks such as the IN4MER Bioink platform enable real-time monitoring of multiple analytes and temperature within bioprinted constructs, providing continuous authentication of microenvironment conditions [22].

Integrated Authentication Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive authentication workflow for 3D bioprinting and smart biomaterial research:

Integrated Authentication Workflow for Advanced Biomaterials: This diagram illustrates the essential checkpoints throughout the research process, from initial material sourcing through final documentation, highlighting the continuous nature of authentication in advanced biomaterials research.

Research Reagent Solutions for Smart Biomaterials

Table 3: Authentication Tools for Smart Biomaterials Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stimuli-Response Calibration Kits | Standardized characterization of smart materials | Include reference materials with known response profiles |

| Biosensing Bioinks | Real-time monitoring of microenvironment | Enable continuous authentication of culture conditions |

| Multi-omics Reference Data | Comprehensive molecular profiling | ATCC Genome Portal provides authenticated reference data |

| Mechanical Characterization Tools | Quantification of dynamic material properties | Rheometers with environmental control, DMA instruments |

| Computational Modeling Platforms | Prediction of material behavior | AI-driven optimization of printing parameters and material formulations |

As 3D bioprinting and smart biomaterials continue to advance toward clinical application, robust authentication practices must be integrated throughout the research workflow. The protocols and guidelines presented here provide a framework for establishing these essential practices, from basic cell line verification to complex characterization of 4D material systems. By adopting these standards, researchers can significantly enhance the reproducibility, reliability, and translational potential of their work in these emerging frontiers.

The movement toward improved authentication is ultimately a cultural shift within the scientific community—one that values transparency, standardization, and rigorous verification alongside innovation and discovery. As the field progresses, continued development of standardized materials, reference data, and shared protocols will be essential for realizing the full potential of these transformative technologies in regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

Proven Tools and Techniques: A Practical Guide to Biomaterial Authentication Methods

The credibility of scientific advancement hinges on the principle of reproducibility. It is estimated that 50% of biological research data is irreproducible, with a significant portion of this irreproducibility associated with gaps in data provenance and poor biological materials [14]. The use of unauthenticated or misidentified biomaterials represents a critical failure point, potentially invalidating years of research and conclusions. Within this framework, robust genotypic methods for authentication are not merely best practices but fundamental necessities. Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling for human cell lines and DNA barcoding for species identification have emerged as two gold-standard genotypic techniques. They provide the essential foundation for ensuring the identity and validity of biological resources, thereby directly contributing to the integrity and reproducibility of research, particularly in drug development and biomedical sciences [14] [11] [15].

STR Profiling for Human Cell Line Authentication

Principles and Applications

Short Tandem Repeats (STRs) are regions of the genome where a short DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) is repeated in tandem. Due to their high variability between individuals, STRs serve as a powerful genetic fingerprint. STR profiling analyzes the length polymorphisms at multiple loci to create a unique genotype for a cell line [24]. The primary application of STR profiling in research is the authentication of human cell lines. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) recognize STR profiling as the gold standard method for this purpose [11]. This is crucial for combating issues of misidentification and cross-contamination, which affect approximately 475 cell lines and can render published findings invalid [11] [15]. Furthermore, major funding agencies like the NIH now require authentication of key biological resources as a condition for grant funding, underscoring its importance in rigorous and reproducible science [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following workflow outlines the standard protocol for STR profiling of human cell lines, based on consensus standards and commercially available kits.

- Sample Requirement: The process begins with genomic DNA extracted from a cell pellet or tissue sample. For human cell lines, this typically involves harvesting cells during active growth [11].

- Multiplex PCR Amplification: The DNA is amplified using a multiplex PCR reaction that simultaneously targets the core STR loci. The ANSI/ATCC ASN-0002 standard specifies a minimum of 8 core STR markers (e.g., CSF1PO, D3S1358, D5S818, D7S820, D8S1179, D13S317, D16S539, D18S51, D21S11, FGA, TH01, TPOX, vWA) along with the sex marker Amelogenin (AMEL) [25] [11]. One primer per locus is fluorescently labeled.

- Capillary Electrophoresis: The PCR products are separated by size using capillary electrophoresis. An instrument detects the fluorescent labels, determining the exact length (and thus the number of repeats) of each STR allele [26].

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: The resulting data is analyzed by software that compares the sample's allele sizes to an allelic ladder (containing common alleles for each locus) to assign a genotype. This STR profile is then compared against reference databases, such as those from ATCC or the DSMZ, to confirm identity or detect cross-contamination [11].

Advanced Techniques and Quantitative Data

While fragment analysis is the established method, Massively Parallel Sequencing (MPS) is advancing STR analysis. MPS can reveal sequence variation within the repeat regions themselves, helping characterize variant and null alleles that can cause allele drop-out [27]. Furthermore, the use of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) in MPS-based STR protocols can reduce sequencing errors and stutter ratios dramatically, from approximately 9.5% to 2.1%, enabling the generation of complete profiles from minute DNA quantities as low as 62.5 pg [28]. This is particularly valuable for analyzing complex mixtures.

Table 1: Core STR Loci for Human Cell Line Authentication

| STR Locus | Chromosomal Location | Key Characteristics | Role in Authentication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amelogenin (AMEL) | Xp22.1-22.3, Yp11.2 | Sex-determining marker | Identifies the sex of the cell line source [11] |

| D5S818 | 5q21-31 | Tetranucleotide repeat | One of the 8 core loci for generating unique profile [25] [11] |

| D13S317 | 13q22-31 | Tetranucleotide repeat | One of the 8 core loci for generating unique profile [25] [11] |

| D7S820 | 7q11.21-22 | Tetranucleotide repeat | One of the 8 core loci for generating unique profile [25] [11] |

| D16S539 | 16q24-qter | Tetranucleotide repeat | One of the 8 core loci for generating unique profile [25] [11] |

| vWA | 12p12-pter | Tetranucleotide repeat | Highly polymorphic, high discrimination power [25] |

| FGA | 4q28 | Tetranucleotide repeat | Highly polymorphic, high discrimination power [25] |

| TH01 | 11p15.5 | Tetranucleotide repeat | Less polymorphic, useful for confirming identity [25] |

| TPOX | 2p25.3 | Tetranucleotide repeat | Less polymorphic, useful for confirming identity [25] |

DNA Barcoding for Species Identification

Principles and Applications

DNA barcoding is a molecular technique that uses a short, standardized genetic sequence from a conserved region of the genome to identify an organism at the species level [29]. For animals, the cytochrome c oxidase I (COI)* gene in the mitochondrial genome is the universal barcode region [30] [29]. The primary application is species identification and discovery, which is vital for biodiversity assessment, conservation biology, and ensuring the correct sourcing of biological materials in research [30] [29]. It is particularly powerful for identifying cryptic species, immature life stages, or incomplete specimens where morphological identification is impossible [29]. In the context of authenticated biomaterials, it ensures that research using animal, plant, or microbial tissues is based on correctly identified species, a foundational aspect of reproducible ecological and comparative studies.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The standard DNA barcoding protocol involves a series of wet-lab and computational steps to assign a species identity to an unknown sample.

- Tissue Sampling: A small tissue sample (e.g., muscle, leaf, exoskeleton) is collected from the specimen [29].

- DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification: Genomic DNA is extracted from the tissue. A PCR reaction is performed using universal primers that are designed to amplify the standardized barcode region, such as the ~658 base pair fragment of the COI gene for animals [30] [29].

- Sequencing: The amplified PCR product is purified and sequenced using Sanger sequencing to determine the precise nucleotide sequence [29].

- Data Analysis and Identification: The resulting sequence, the "DNA barcode," is compared against a curated reference database such as the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD). Identification is achieved by finding the closest-matching sequence in the reference library with a high degree of similarity [30] [29]. The quality of the reference database is paramount for an accurate result.

Quantitative Data and Impact

Large-scale DNA barcoding initiatives have built extensive reference libraries, enabling robust species identification. For example, one study for Central European beetles added more than 3500 identified species to BOLD, analyzing 15,948 individuals [30]. The technique is highly efficient, with one analysis showing that over 92% of specimens could be unambiguously assigned to a known species via their barcode sequence, highlighting its power and reliability [30].

Table 2: Standard DNA Barcodes Across Kingdoms

| Kingdom | Standard Barcode Region | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Animals | Cytochrome c Oxidase I (COI) | Species identification, biodiversity monitoring, authentication of animal-derived research materials [30] [29]. |

| Plants | rbcL, matK, ITS2 | Delineation of plant species, which can be difficult with morphology alone; verification of botanical samples. |

| Fungi | Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) | Identification of fungal species, critical for microbiology and environmental studies. |

| Bacteria & Archaea | 16S rRNA | Taxonomic classification of prokaryotes, essential for microbiome and microbial ecology research. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of these genotypic methods depends on access to specific, high-quality reagents and reference materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for STR Profiling and DNA Barcoding

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial STR Kit | Contains pre-optimized primers, master mix, and allelic ladders for multiplex PCR of core STR loci. | STR Profiling [25] [11] |

| Authenticated Reference DNA | Provides a positive control with a known STR profile to validate the entire genotyping process. | STR Profiling [11] |

| Cell Line Database (e.g., ATCC, DSMZ) | Repository of STR profiles for verified cell lines; essential for comparison and authentication. | STR Profiling [11] |

| Universal Barcode Primers | Primer sets designed to amplify the standardized barcode region (e.g., COI) across a wide taxonomic range. | DNA Barcoding [29] |

| Reference Database (e.g., BOLD Systems) | Curated, public repository of known species barcode sequences; the key to identification. | DNA Barcoding [30] [29] |

| High-Quality DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for PCR amplification; critical for success with degraded or low-quantity samples. | Both Methods |

| Capillary Sequencer | Instrument for high-resolution fragment analysis (STRs) or DNA sequencing (barcoding). | Both Methods |

STR profiling and DNA barcoding are indispensable tools in the modern scientist's arsenal for combating the reproducibility crisis. By providing unambiguous genotypic identities for human cell lines and biological species, respectively, these methods establish a foundation of trust in the biomaterials upon which research is built. Adherence to standardized protocols, such as the ANSI/ATCC standard for STR profiling and the use of universal barcode regions, ensures consistency and comparability of data across laboratories. As technologies like MPS with UMIs evolve, these gold-standard methods will become even more sensitive and informative, further strengthening the integrity of biomedical and ecological research and accelerating the pace of reliable discovery.

The advancement of degradable biomaterials, such as magnesium-based alloys, presents a unique challenge for traditional biocompatibility assessment, which often relies on single time-point endpoint assays. These methods can miss critical dynamic cellular responses to the evolving properties of a degrading material. Within the broader thesis context of using authenticated biomaterials for reproducible research, Real-Time Cell Analysis (RTCA) emerges as a powerful tool for dynamic phenotypic and functional assessment. RTCA is a label-free, impedance-based technology that allows for the continuous, non-invasive monitoring of cell populations, providing rich kinetic data on cell behavior that is essential for rigorous and reproducible scientific findings [31].

Reproducibility in life science research is a fundamental pillar of scientific advancement, yet it is frequently undermined by factors such as the use of misidentified or cross-contaminated cell lines and poor experimental practices [15]. Adhering to best practices, including the use of authenticated, low-passage cell lines and robust sharing of data and methodologies, is crucial for generating reliable and verifiable data [15]. This application note details how the xCELLigence RTCA system can be integrated into a framework of research rigor, providing a highly reproducible data set during the drug and biomaterial development process [32]. By offering a window into the real-time dynamics of cell-biomaterial interactions, RTCA moves beyond the snapshot provided by endpoint assays, enabling a more comprehensive and trustworthy evaluation of biocompatibility.

Key Principles and Advantages of the RTCA System

How Impedance-Based Real-Time Cell Analysis Works

The xCELLigence RTCA system operates by measuring electrical impedance across microelectrode sensors integrated into the bottom of specialized culture plates (E-Plates). The core components of the system include the RTCA analyzer unit placed inside a standard CO₂ incubator, a computer with integrated software, and the single-use E-Plates themselves [32]. When cells are not present, an electrical current flows freely through the culture medium. As cells adhere and spread on the electrode surfaces, they impede the current flow in a manner proportional to their biological status. The system applies a weak, non-invasive electrical potential (e.g., ~1 µA current and >10 mV voltage) to the electrodes and measures the resulting impedance [32].

The measured impedance values are automatically processed and converted into a dimensionless parameter called the Cell Index (CI). The CI is a quantitative measure of cellular status, where a value of zero indicates no cell attachment, and increasing positive values reflect greater cell adhesion, spreading, and proliferation. The formula for CI is derived from the relative change in impedance and is calculated as follows:

CI = (Impedance at time point n - Impedance in the absence of cells) / Nominal impedance value. The magnitude of the Cell Index is influenced by several factors, including cell number, cell size, cell-substrate attachment quality, and the degree of cell-cell interactions [32]. When a confluent monolayer is formed, the CI stabilizes, and any subsequent changes can indicate alterations in barrier function, cell health, or morphology in response to a test compound.

Comparative Advantages of RTCA Over Endpoint Assays

The real-time, label-free nature of RTCA provides distinct advantages over conventional endpoint assays, aligning with the need for more reproducible and informative data in biomaterials research.

Table 1: Comparison of RTCA with Traditional Endpoint Cytotoxicity Assays

| Feature | RTCA (Impedance-Based) | Tetrazolium Salt Assays (e.g., MTT) |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Type | Dynamic, continuous, and label-free | Single time-point endpoint; requires a label/dye |

| Temporal Resolution | High-resolution kinetic data | Single data point at assay termination |

| Information Output | Cell proliferation, adhesion, morphology, death, and barrier integrity | Indirect measure of metabolic activity only |

| Assay Workflow | Non-invasive; minimal handling | Invasive; requires cell lysis and/or multiple washing steps |

| Impact on Cell Physiology | Minimal to none; allows for subsequent analysis | Terminates the experiment; can be cytotoxic |

| Data Reproducibility | Highly reproducible, automated monitoring | Subject to variability from incubation timing and manual steps |

| Best Application | Dynamic biocompatibility of degradable materials; kinetic phenotyping | Endpoint metabolic viability screening of static materials |

As shown in Table 1, RTCA enables the fast and easy detection of cell kinetics and quality of attachment in real-time, providing a data-rich profile of a cell population's response [32]. This is particularly valuable for testing degradable biomaterials like magnesium alloys, whose properties and extracts change over time. A 2020 study demonstrated that RTCA results highly matched those from the MTT assay but crucially revealed different dynamic modes of the cytotoxic process that were invisible to the endpoint method [33]. Furthermore, endpoint assays like MTT can be unreliable when testing colored compounds or materials that may interfere with the assay's absorbance readings, a limitation not shared by the impedance-based RTCA [31].

Application Note: Dynamic Biocompatibility Assessment of Magnesium-Based Biomaterial Extracts

Experimental Protocol

This protocol outlines the use of the xCELLigence RTCA SP16 system for evaluating the dynamic cytotoxicity of degradable magnesium (Mg)-based biomaterial extracts, using the well-characterized L929 fibroblast cell line as a model.

1. Preparation of Biomaterial Extracts:

- Prepare extracts of pure Mg and its calcium alloy according to ISO 10993-12 guidelines [33].

- Use different extraction media (e.g., complete cell culture medium, saline) as required.

- Filter-sterilize the extracts using a 0.22 µm filter.

- Measure and record the Mg²⁺ concentration and osmolality of each extract, as these are critical parameters influencing cytotoxicity [33].

2. Cell Seeding and Baseline Monitoring on the RTCA System:

- Harvest and count L929 cells in the logarithmic growth phase.

- Prepare a cell suspension at a density of 5.0 x 10⁴ cells/mL in complete growth medium.

- Background measurement: Add 50 µL of medium alone to the wells of a 16-well E-Plate to obtain a background impedance reading.

- Seed the cells: Add 100 µL of the cell suspension (5,000 cells/well) to the designated wells of the E-Plate. Gently tap the plate to ensure even distribution.

- Place the E-Plate in the RTCA SP16 analyzer within the incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂) and start running the experiment program.

- Monitor the Cell Index every 15 minutes for the first 8-24 hours until the cells enter a stable logarithmic growth phase, indicated by a steadily increasing CI. This establishes a robust, quantitative baseline for each well.

3. Treatment with Biomaterial Extracts and Real-Time Monitoring:

- After the baseline period, carefully remove the E-Plate from the analyzer.

- Prepare treatment media by diluting the Mg-based extracts in complete growth medium at various dilution rates (e.g., 1:2, 1:4, 1:8).

- Aspirate the old medium from the wells and replace it with 150 µL of the respective treatment media. Include untreated control wells (medium change only) and vehicle control wells.

- Return the E-Plate to the RTCA analyzer and continue monitoring the Cell Index every 30 minutes for a further 48-72 hours.

- The software automatically records and graphs the CI in real-time.

4. Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- Normalize the Cell Index data to a specific time point (e.g., the time of treatment) to facilitate direct comparison between wells.

- Analyze the resulting kinetic curves (see Fig. 1 for an example). Key parameters to assess include:

- Slope of CI curve post-treatment: Indicates the rate of proliferation or inhibition.

- Time to CI drop: Indicates the onset of cytotoxicity.

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): Provides a quantitative measure of overall cell health over the entire exposure period.

- Compare the dynamic responses of different extract types and dilution rates to identify concentration-dependent and time-dependent effects.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for RTCA Biocompatibility Assays

| Item | Function in the Assay | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| xCELLigence RTCA SP16 System | Core instrument for automated, real-time impedance monitoring. | Includes analyzer, station, and software [32]. |

| E-Plate 16 (PET) | 16-well plate with integrated gold microelectrodes for cell seeding and monitoring. | Single-use, biosensor-free window for microscopy [32]. |

| Authenticated Cell Lines | Biologically relevant and verified models for testing. | L929 (mouse fibroblast), MG-63 (human osteosarcoma), HUVEC (human umbilical vein endothelial cell) [33]. Use low-passage, authenticated stocks. |

| Cell Culture Medium | Provides nutrients and environment for cell growth. | DMEM or RPMI-1640, supplemented with FBS and antibiotics. |

| Biomaterial Extracts | Test substances whose biocompatibility is being evaluated. | Prepared per ISO 10993-12 from materials like pure Mg or Mg-Ca alloys [33]. |

| Sterile Filtration Unit (0.22 µm) | Ensures sterility of prepared biomaterial extracts before application to cells. | Critical for preventing microbial contamination. |

Expected Results and Data Output

The RTCA system generates kinetic cell response profiles (CIs over time) that reveal the dynamic nature of cell-material interactions. The following diagram illustrates a typical experimental workflow and the resultant data output.

Diagram 1: RTCA experimental workflow for biocompatibility assessment.

When the experiment is complete, the software generates a plot of Cell Index versus Time. A normal, healthy cell population will show a characteristic sigmoidal curve: an initial lag phase as cells adhere, a log phase of rapid proliferation, and a plateau phase as confluence is reached. Treatment with a cytotoxic extract can result in several distinct dynamic patterns [33]:

- Cytostatic Effect: A flattening of the CI curve, indicating a halt in proliferation without cell death.

- Cytotoxic Effect: A sharp decline in CI, indicating cell death and detachment from the electrodes.

- Delayed Cytotoxicity: An initial period of normal growth followed by a later decline, highlighting the kinetic nature of the extract's effect.

Table 3: Quantitative Data Analysis from a Representative RTCA Experiment on Mg Alloy Extracts (Adapted from [33])

| Sample | Dilution Rate | Time to 50% CI Drop (hours) | Maximum CI Inhibition (%) | AUC (0-72h) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (Medium) | - | >72 | 0% | 450 | Normal growth |

| Pure Mg Extract | 1:2 | 18.5 | 95% | 120 | Severe cytotoxicity |

| Pure Mg Extract | 1:4 | 36.0 | 70% | 210 | Moderate cytotoxicity |

| Mg-Ca Alloy Extract | 1:2 | 28.0 | 60% | 290 | Mild cytotoxicity |

| Mg-Ca Alloy Extract | 1:4 | >72 | 15% | 410 | Slight cytostatic effect |

Advanced Protocol: Real-Time Monitoring of Epithelial Barrier Integrity in Caco-2 Cells

Beyond standard cytotoxicity, RTCA is exceptionally suited for monitoring the formation and integrity of cellular barriers, a critical function for modeling intestinal or endothelial permeability.

Protocol Overview:

- Culture Caco-2 cells on the E-Plate 16 at a high density (e.g., 1.0 x 10⁵ cells/well) to encourage monolayer formation.

- Monitor the cells in real-time for 18-21 days. The Cell Index will initially rise as cells proliferate and then stabilize into a high plateau as they become confluent and form tight junctions. This high, stable CI is a functional correlate of the barrier integrity traditionally measured by Trans-Epithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) [32].

- Once the CI plateau is established, treat the monolayer with a pro-inflammatory cytokine like TNF-α or a test compound like L-DOPA to challenge the barrier integrity [32].

- A subsequent drop in the Cell Index indicates a disruption of the tight junctions and a loss of barrier function, which can be quantified in real-time without the invasiveness and variability associated with manual electrode positioning in traditional TEER systems [32].

Real-Time Cell Analysis represents a significant advancement in phenotypic and functional assay technology. By providing continuous, label-free, and highly reproducible kinetic data on cell health, proliferation, and barrier function, it offers a more physiologically relevant and information-rich alternative to endpoint assays. This is particularly critical for the evaluation of degradable biomaterials, whose dynamic interaction with biological systems cannot be fully captured by a single time-point measurement.

When integrated into a rigorous research framework that prioritizes the use of authenticated biomaterials, including verified cell lines and thoroughly characterized materials, RTCA becomes a powerful tool for enhancing scientific reproducibility. Its ability to reveal the dynamic modes of cytotoxicity and subtle changes in cellular function supports the generation of more reliable and translatable data, ultimately accelerating the development of safe and effective biomedical implants and therapies.

This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for novel analytical approaches essential for ensuring the authenticity of biomaterials in reproducible research. Ensuring the identity, purity, and molecular consistency of biological starting materials—from complex botanicals to engineered tissue models—is a foundational prerequisite for generating reliable and translatable scientific data. This guide details practical methodologies for applying omics technologies for deep molecular characterization, chemometric-assisted spectroscopy for rapid authentication, and multi-omics integration for a systems-level view. The protocols are designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to build rigorous quality control into their workflows for biomaterials such as botanical supplements, engineered tissues, and other bio-derived matrices.

Application Note: Single-Cell Omics for Characterizing Engineered Tissue Models

Background and Principle

Advanced 3D engineered tissues, such as bioengineered breast cancer models, are increasingly used for drug screening and disease modeling due to their superior clinical relevance compared to 2D cultures [34]. A critical challenge is their thorough biological validation to ensure they accurately recapitulate the genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic diversity of native tissues and patient tumors [34]. Single-cell omics technologies resolve cellular heterogeneity by profiling individual cells, moving beyond the averaged signals of bulk analyses [35]. This application note outlines the use of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to authenticate and benchmark the cellular composition of a 3D breast cancer model against primary tumor data.

Experimental Protocol

Protocol 1: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of a 3D Bioengineered Breast Cancer Model

- Objective: To characterize cellular heterogeneity, identify distinct cell populations, and benchmark against primary tumor transcriptomic data.

Materials:

- Validated 3D bioengineered breast cancer model (e.g., in a hyaluronan-oxime hydrogel [34])

- Dissociation reagent (e.g., collagenase, trypsin-EDTA)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Cell viability dye (e.g., Propidium Iodide)

- Single-cell RNA sequencing platform (e.g., 10X Genomics Chromium)

- Appropriate scRNA-seq reagent kit (e.g., Chromium Single Cell 3' Reagent Kits)

Procedure:

- Model Dissociation: Gently dissociate the 3D model into a single-cell suspension using a optimized enzymatic protocol to maximize cell viability and minimize stress-induced transcriptional changes.

- Cell Quality Control: Filter the cell suspension through a flow cytometry-compatible strainer. Assess cell viability and count using a hemocytometer with a viability dye or an automated cell counter. Target a viability of >90%.

- Single-Cell Partitioning and Library Preparation: Using the 10X Genomics Chromium Controller, partition approximately 10,000 viable cells into nanoliter-scale droplets with barcoded beads according to the manufacturer's instructions [35]. Perform reverse transcription, cDNA amplification, and library construction as per the kit protocol.

- Sequencing: Pool the constructed libraries and sequence on an Illumina platform to a recommended depth (e.g., 50,000 reads per cell).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Data Processing: Use the 10X Genomics

Cell Rangerpipeline for demultiplexing, barcode processing, and alignment to the human reference genome (GRCh38). - Quality Control: Filter out cells with low unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts, high mitochondrial gene percentage, or an outlier number of detected genes.