Atomic and Crystalline Structure of Materials: Advanced Characterization for Biomedical Innovation

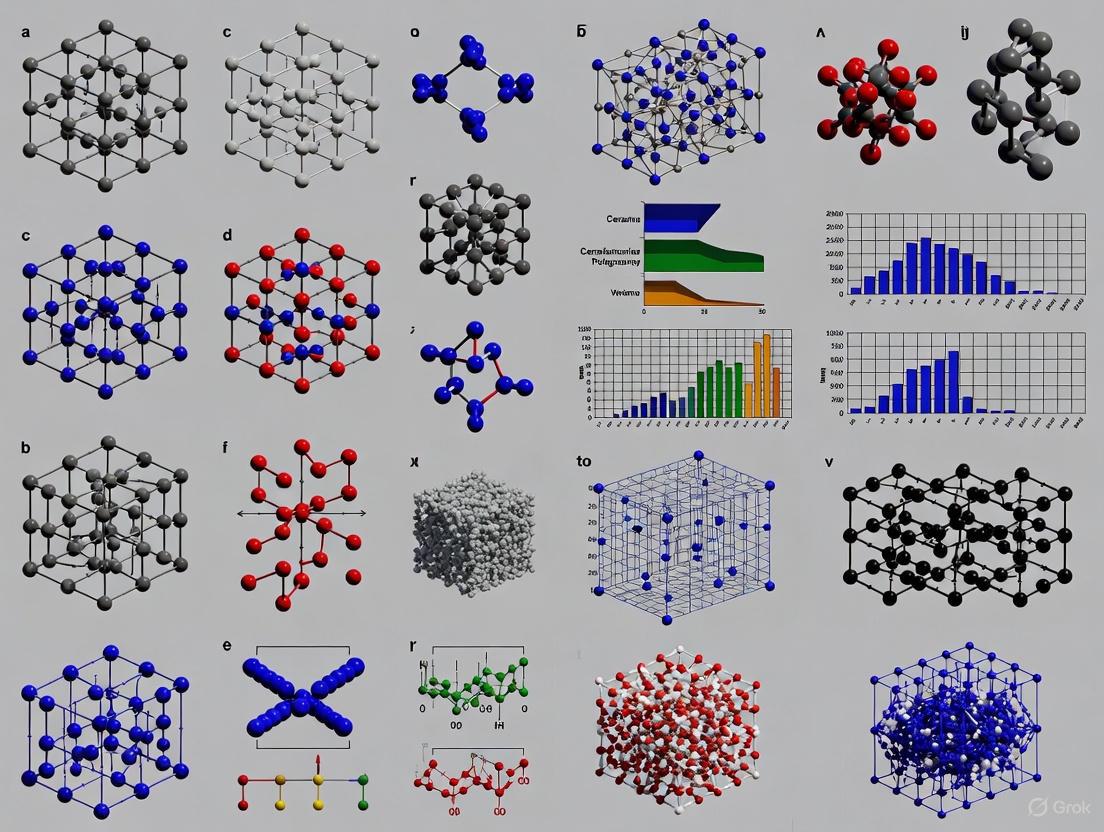

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the pivotal role atomic and crystalline structure plays in determining material properties, with a specific focus on applications in pharmaceutical and biomedical research.

Atomic and Crystalline Structure of Materials: Advanced Characterization for Biomedical Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the pivotal role atomic and crystalline structure plays in determining material properties, with a specific focus on applications in pharmaceutical and biomedical research. It explores foundational concepts of crystallinity, from classic Wigner crystals to modern quasicrystals, and details cutting-edge characterization methodologies, including AI-enhanced X-ray diffraction and super-resolution microscopy. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting in material analysis and offers a comparative validation of techniques, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to leverage atomic-scale insights for advancing drug formulation, delivery, and novel therapeutic material design.

The Atomic Blueprint: How Crystal Structure Dictates Material Behavior and Properties

Fundamental Principles of Atomic Arrangement in Crystals

A crystalline solid is characterized by a highly ordered, repeating arrangement of its constituent particles—atoms, ions, or molecules. This long-range order results from the repetitive, three-dimensional patterning of these components, forming what is known as a crystal lattice [1] [2]. The smallest repeating unit that fully captures the symmetry and structure of the entire crystal is the unit cell [1]. By translating the unit cell along its principal axes in three-dimensional space, the entire crystal lattice is constructed [2]. The geometry of the unit cell is described by six lattice parameters: the lengths of its edges (a, b, c) and the angles between them (α, β, γ) [2].

Table 1: The Seven Crystal Systems and Their Lattice Parameters

| Crystal System | Axial Lengths | Axial Angles | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cubic | a = b = c | α = β = γ = 90° | CsCl, NaCl |

| Tetragonal | a = b ≠ c | α = β = γ = 90° | White Tin, TiO₂ (Rutile) |

| Orthorhombic | a ≠ b ≠ c | α = β = γ = 90° | Sulfur, BaSO₄ |

| Rhombohedral (Trigonal) | a = b = c | α = β = γ ≠ 90° | Calcite (CaCO₃), Quartz |

| Hexagonal | a = b ≠ c | α = β = 90°, γ = 120° | Zinc, Cadmium |

| Monoclinic | a ≠ b ≠ c | α = γ = 90°, β ≠ 90° | Sucrose, Gypsum |

| Triclinic | a ≠ b ≠ c | α ≠ β ≠ γ ≠ 90° | K₂Cr₂O₇, CuSO₄ |

Unit Cell Geometry and Crystal Systems

There are seven fundamentally different kinds of unit cells, or crystal systems, which are distinguished by the relative lengths of their edges and the angles between them [1]. These systems form the foundation for classifying all crystalline materials and are summarized in Table 1. The inherent symmetry of a crystal, described by its space group, is a critical defining property. All crystals possess translational symmetry, and many also have additional symmetry elements like rotational axes or mirror planes [2]. The arrangement of atoms within the unit cell and the overall crystal symmetry are paramount in determining a material's physical properties, including its cleavage, electronic band structure, and optical transparency [2].

Atomic Packing and Cubic Crystal Structures

Cubic unit cells are among the simplest to visualize and understand. There are three primary types of cubic lattices, which differ in the positions of the atoms within the cell [1]:

- Simple Cubic (SC): Atoms are located only at the eight corners of the cube.

- Body-Centered Cubic (BCC): In addition to the corner atoms, a single atom is situated at the very center of the cube.

- Face-Centered Cubic (FCC): Atoms are located at the eight corners and at the center of each of the six faces of the cube.

The coordination number, which is the number of nearest neighbor atoms surrounding a given atom, varies with the lattice type. Similarly, the atomic packing factor, the fraction of volume in the crystal structure occupied by constituent particles, is different for each structure. The arrangement of atoms into these dense planes and directions significantly influences material properties such as plastic deformation and cleavage [2].

Crystallographic Planes, Directions, and the Miller Index

To describe the orientation of planes and directions within a crystal lattice, crystallographers use the Miller index notation [2]. This system uses a set of three integers (h, k, ℓ) enclosed in parentheses (hkl) to denote a specific family of planes. These indices are proportional to the reciprocals of the fractional intercepts the plane makes with the crystallographic axes. The perpendicular spacing between adjacent (hkl) lattice planes, known as the interplanar spacing (d), is crucial in diffraction studies and is calculated differently for each crystal system.

Table 2: Interplanar Spacing (d) Formulas for Major Crystal Systems

| Crystal System | Formula for 1/d² |

|---|---|

| Cubic | (h² + k² + ℓ²) / a² |

| Tetragonal | (h² + k²)/a² + ℓ²/c² |

| Hexagonal | (4/3)((h² + hk + k²)/a²) + ℓ²/c² |

| Orthorhombic | h²/a² + k²/b² + ℓ²/c² |

| Monoclinic | (h²/a² + k²sin²β/b² + ℓ²/c² - 2hℓcosβ/(ac)) csc²β |

For directions in a crystal, a similar notation [uvw] is used, representing a vector in the direction ua + vb + wc, where a, b, and c are the lattice vectors. Due to symmetry, certain families of planes or directions are equivalent; these are denoted with curly braces {hkl} for planes and angle brackets

Advanced Characterization and Analysis Protocols

Modern materials research relies on advanced techniques to quantitatively analyze crystal structures and compositions at the atomic scale.

Quantitative Elemental Analysis at Atomic Scale

The integration of Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) with High-Angle Annular Dark Field (HAADF) imaging and Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) allows for precise characterization of elemental substitution in mixed crystals [3]. This approach was effectively used to analyze the distribution of Lu and Gd in mixed-vanadate LuxGd1-xVO4 single crystals [3].

Experimental Protocol: Quantitative Elemental Analysis [3]

- Crystal Growth: Grow high-quality mixed vanadate crystals (e.g., LuxGd1-xVO4) using the Czochralski method.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a TEM sample via Focused Ion Beam (FIB) thinning.

- Microscopy & Spectroscopy:

- Acquire high-resolution atomic images along specific crystal orientations (e.g., [100], [111]) using HAADF-STEM.

- Collect simultaneous EDS and EELS spectra to obtain chemical information.

- Data Analysis:

- Analyze the EELS fine structure to differentiate between similar elements (e.g., Lu and Gd).

- Quantify the Lu/Gd ratio by integrating core-loss peaks in the EELS spectra.

- Confirm a uniform and random distribution of elements by combining EELS data with EDS mapping.

Quantum Crystallographic Refinement Protocol

Quantum crystallography refines X-ray diffraction data to achieve accuracy comparable to neutron diffraction, providing access to the complete electronic structure of a compound [4]. A general protocol for quantum crystallographic refinement is as follows.

Experimental Protocol: Quantum Crystallographic Refinement [4]

- Data Collection: Measure a standard test crystal (e.g., YLID - 2-dimethylsulfuranylidene-1,3-indanedione) on a single-crystal diffractometer.

- Initial Processing:

- Solve the crystal structure using a direct methods program (e.g., ShelxT).

- Perform an initial refinement with an Independent Atom Model (IAM) using a least-squares program (e.g., ShelxL).

- Data Merging: Use the refinement program to output a merged HKL file of structure factor magnitudes, corrected for anomalous dispersion and extinction.

- Quantum Refinement: Subject the data to one or more quantum crystallographic refinement techniques:

- Hirshfeld Atom Refinement (HAR): Refines atomic positions and displacement parameters using aspherical atomic form factors from quantum-mechanical calculations.

- Multipole Model (MM): Models the experimental electron density using a multipole expansion.

- X-ray Constrained Wavefunction (XCW) Fitting: Fits a wavefunction to the experimental X-ray data.

- Validation & Deposition: Analyze the total electron-density distribution and refined parameters for quality assessment. Deposit the final structure and structure factors in a public database (e.g., Cambridge Structural Database).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Crystallographic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| YLID Test Crystal (2-dimethylsulfuranylidene-1,3-indanedione) | Standard sample for calibrating and testing single-crystal X-ray diffractometers [4]. | Hardware validation and protocol development in quantum crystallography [4]. |

| Rare-Earth Vanadates (RVO₄, R=Y, Lu, Gd, etc.) | Important laser host materials; mixed crystals (e.g., LuxGd1-xVO4) enable study of elemental substitution [3]. | Investigating how doping concentration affects thermal, optical, and laser properties [3]. |

| Organic Molecular Crystals (from CSD) | Diverse benchmark structures for computational studies and machine learning datasets [5]. | Creating large-scale datasets (e.g., OE62) for validating computational methods and predicting molecular properties [5]. |

| High-Purity Metal Salts (e.g., NaKC₄H₄O₆·4H₂O) | Used for growing single crystals of materials like Rochelle salt, an early-discovered ferroelectric [6]. | Studying ferroelectricity and piezoelectric effects in non-centrosymmetric crystals [6]. |

| Silica Gel / Alumina | Stationary phase for purification via column chromatography [4]. | Purifying synthetic products (e.g., YLID) prior to crystal growth [4]. |

| Crystallization Solvents (e.g., Acetone, Acetonitrile) | Medium for recrystallization to obtain high-quality single crystals [4]. | Growing single crystals with natural faces for high-resolution diffraction studies [4]. |

The classical definition of a crystal, as a solid with a periodically repeating atomic structure, has been a cornerstone of materials science. However, this definition was fundamentally challenged and expanded by the discovery of quasicrystals—solids that possess long-range order but lack translational periodicity [7] [8]. Unlike conventional crystals, whose atoms are arranged in repeating unit cells, the atomic patterns in quasicrystals never exactly repeat themselves [9]. This paradoxical nature, which once seemed "impossible" to scientists, forces a re-evaluation of the atomic and crystalline structure of materials and opens new avenues for designing solids with novel properties [8] [10]. The study of quasicrystals is not merely an academic curiosity; it is pushing the boundaries of materials research, with potential implications for fields ranging from aerospace engineering to spintronics and drug development.

Fundamental Principles and Historical Context

Defining the "Impossible" Crystal

Quasicrystals inhabit a unique structural space between perfectly ordered crystals and completely disordered amorphous solids, such as glass [7] [8]. Their defining characteristic is the possession of "forbidden" symmetries—such as five-fold, ten-fold, or twelve-fold rotational symmetry—that are impossible in periodic crystals [7] [11]. For example, a quasicrystal with five-fold symmetry can be rotated by 72 degrees (360/5) and appear identical, a property that precludes a repeating unit cell because pentagons cannot tile a plane without gaps or overlaps [8] [11].

The never-repeating pattern arises from an irrational number, often the golden ratio (φ ≈ 1.618), at the heart of its construction [11]. Mathematically, these structures can be described by quasiperiodic tilings, such as the famous Penrose tiling, which use two or more tile shapes to cover a plane infinitely without periodicity [8] [11].

A Paradigm-Shifting Discovery

The existence of quasicrystals was first demonstrated by Dan Shechtman in 1982 while studying rapidly cooled alloys of aluminum and manganese [9] [7]. His observation of a diffraction pattern with "ten-fold???" symmetry, noted in his lab journal, directly contradicted the established rules of crystallography [7]. The discovery was so revolutionary that it faced intense initial skepticism before ultimately leading to the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011 [9] [7].

Simultaneously, theoretical physicist Paul Steinhardt independently hypothesized the existence of structures with five-fold symmetry, later coining the term "quasicrystal" [7] [8]. His quest to find natural quasicrystals led to the discovery of icosahedrite and decagonite in mineral samples from the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia, proving they are not solely human-made artifacts [7].

Table 1: Key Differences Between Crystals and Quasicrystals

| Feature | Traditional Crystals | Quasicrystals |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Arrangement | Periodic and repeating | Aperiodic and non-repeating |

| Unit Cell | Defined, repeating unit | No repeating unit cell |

| Allowed Rotational Symmetries | Two-fold, three-fold, four-fold, six-fold | Five-fold, ten-fold, twelve-fold |

| Mathematical Basis | Periodic tiling | Quasiperiodic tiling (e.g., Penrose) |

Methodologies for Quasicrystal Synthesis and Analysis

The unique structure of quasicrystals necessitates advanced and often specialized techniques for their synthesis and characterization. The following experimental protocols are central to the field.

Synthesis via Additive Manufacturing

Metal 3D printing, or powder bed fusion, has emerged as a powerful method for creating quasicrystalline phases in alloys. The extreme thermal conditions of the process are conducive to forming these metastable structures [9].

Protocol: Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Aluminum Alloys

- Powder Preparation: A fine powder of a pre-alloyed material, such as an aluminum-zirconium (Al-Zr) alloy, is prepared. Zirconium acts as a crack-suppressing agent [9].

- Layer Deposition: A recoating blade spreads a thin layer (typically tens of micrometers) of the metal powder evenly over a build platform [9].

- Laser Melting: A high-power laser scans the powder bed according to a pre-programmed path, selectively melting the powder particles. The laser must raise the temperature far beyond aluminum's melting point (past its boiling point of 2,470 °C) to create the necessary rapid melting and solidification dynamics [9].

- Layer Repetition: The build platform is lowered, a new layer of powder is applied, and the laser melting process repeats, building the part layer-by-layer [9].

- Post-Processing: The resulting component, which contains quasicrystalline phases, is removed from the powder bed and may undergo heat treatment to stabilize the microstructure [9].

Atomic-Scale Characterization via Electron Microscopy

Identifying quasicrystals requires resolving atomic-scale structures, typically achieved through Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM).

Protocol: Identifying Quasicrystals in TEM

- Sample Preparation: A thin foil or sliver of the alloy is prepared via focused ion beam (FIB) milling to achieve electron transparency [9].

- Imaging and Diffraction: The sample is placed in the TEM and subjected to a high-energy electron beam.

- Symmetry Analysis: The key step is tilting the crystal and obtaining selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns from multiple zone axes. The researcher looks for the telltale signature of five-fold rotational symmetry in the diffraction pattern [9].

- Confirmation: To confirm a quasicrystal, the pattern must also exhibit two-fold and three-fold symmetry from different orientations, proving the existence of an icosahedral phase [9].

Computational Stability Analysis via "Nanoscooping"

A longstanding challenge has been explaining the thermodynamic stability of quasicrystals using quantum-mechanical methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT), which traditionally relies on periodic structures [8] [10]. A recent breakthrough protocol circumvented this limitation.

Protocol: DFT Stability Calculation for Aperiodic Structures

- Nanoparticle Extraction ("Nanoscooping"): From a larger, known quasicrystalline model, multiple clusters of atoms of increasing size (e.g., from 24 to 740 atoms) are digitally "scooped out" [8] [10].

- Energy Calculation: For each nanoparticle, the total energy is calculated using DFT. Because the nanoparticle has a finite size and a defined surface, this calculation is feasible without assuming periodicity [10].

- Extrapolation: The computed energies are plotted against nanoparticle size. The relationship between energy, volume, and surface area allows researchers to extrapolate the energy of the bulk, infinite quasicrystal [8] [10].

- Stability Assessment: The extrapolated energy is compared to the energies of other possible crystalline forms of the same elements. If the quasicrystal's energy is lower, it is confirmed as the stable, ground-state phase [10].

Diagram 1: Workflow for computational stability analysis.

Key Research Findings and Data

Recent research has yielded significant insights into the stability, properties, and potential applications of quasicrystals, moving them from laboratory curiosities toward usable materials.

Mechanical and Functional Properties

Quasicrystals exhibit a unique combination of properties stemming from their hybrid structure. They are typically hard, brittle, and possess low surface energy, making them suitable for use as reinforcing phases or non-stick coatings [9] [7] [8]. Electrically, they are poor conductors, often behaving more like semiconductors, though recent work with twisted graphene layers has demonstrated the possibility of inducing superconductivity in quasicrystalline systems [7].

A pivotal 2025 study from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) demonstrated that quasicrystals can directly enhance mechanical strength. In a 3D-printed aluminum alloy, the quasicrystalline phases acted as obstacles within the material, preventing the atomic-scale slip that causes deformation in perfect crystals, thereby increasing the overall strength of the metal [9].

Groundbreaking Magnetic and Stability Discoveries

The year 2025 has been particularly fruitful, with several landmark publications.

- Discovery of Antiferromagnetism: Researchers at Tokyo University of Science reported the first definitive observation of antiferromagnetic order in a gold-indium-europium (Au-In-Eu) icosahedral quasicrystal [12]. This was a surprise because antiferromagnetism, where magnetic moments alternate in a regular pattern, was thought to be incompatible with non-repeating structures. The magnetic transition was observed at 6.5 Kelvin using neutron diffraction, opening a new field of quasiperiodic antiferromagnets with potential in spintronics [12].

- Proof of Thermodynamic Stability: Using the "nanoscooping" DFT method, a team from the University of Michigan provided the first quantum-mechanical evidence that certain quasicrystals (e.g., Scandium-Zinc and Ytterbium-Cadmium alloys) are enthalpy-stabilized [10]. This means their structure represents a low-energy ground state, not a frozen metastable state like glass, fundamentally explaining why they can form and persist [10].

Table 2: Summary of Recent Key Discoveries in Quasicrystal Research (2025)

| Discovery | Material System | Key Finding | Potential Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antiferromagnetic Order [12] | Au-In-Eu iQC | Long-range magnetic order at 6.5 K | Spintronic devices, magnetic refrigeration |

| Strength Enhancement [9] | 3D-printed Al-Zr alloy | Quasicrystals impede dislocation slip | High-strength, lightweight aerospace components |

| Thermodynamic Stability [10] | Sc-Zn, Yb-Cd alloys | Quasicrystal is the enthalpy-stabilized ground state | Guides design of new stable quasicrystals |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Progress in quasicrystal research relies on a specific set of materials and computational tools. The following table details key resources used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Quasicrystal Experimentation

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Aluminum-Zirconium (Al-Zr) Alloy Powder | Feedstock for powder-bed fusion; Zr prevents cracking during 3D printing, allowing quasicrystal formation [9]. |

| Scandium-Zinc (Sc-Zn) & Ytterbium-Cadmium (Yb-Cd) Alloys | Model systems for computational and experimental studies of stable quasicrystalline phases [10]. |

| Gold-Indium-Europium (Au-In-Eu) Alloy | The first icosahedral quasicrystal system demonstrated to host long-range antiferromagnetic order [12]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Code | Quantum-mechanical simulation software used to calculate electronic structure and total energy of configurations [8] [10] [13]. |

| Exascale Computing Resources | High-performance computing (HPC) systems essential for performing massive DFT calculations on aperiodic structures [8]. |

The study of quasicrystals has evolved from confronting a scientific "impossibility" to establishing a vibrant and forward-looking field within materials research. The recent demonstrations of their thermodynamic stability, their role in enhancing mechanical strength in additive manufacturing, and the discovery of previously unseen properties like antiferromagnetism underscore their scientific and technological relevance [9] [12] [10].

Future research will likely focus on intentionally designing quasicrystals for specific applications, moving beyond the serendipitous discoveries of the past [9]. The integration of generative artificial intelligence and machine learning for crystal structure prediction presents a promising path for discovering new quasicrystalline compositions [14] [13]. Furthermore, scaling up synthesis methods, such as the new technique using micrometer-scale Dynabeads to model atomic assembly, will be crucial for industrial application [8]. As these unique non-repeating patterns continue to spill their secrets, they are poised to enable a new generation of materials with tailored properties for advanced technologies in electronics, energy, and aerospace.

The exploration of quantum phases of matter represents a central frontier in condensed matter physics, offering profound implications for our understanding of atomic and crystalline structure in materials research. The behavior of electrons, the fundamental carriers of electricity, transitions from familiar independent-particle motion to complex collective phenomena under specific conditions of density, temperature, and interaction strength. When electron-electron repulsive interactions dominate over kinetic energy, electrons can spontaneously organize into exotic quantum phases with unique structural and electronic properties. These phases include the long-theorized Wigner crystal, where electrons arrange into a regular lattice, and newly discovered states like the 'pinball' phase, which exhibits hybrid solid-liquid characteristics [15] [16].

The study of these correlated electron systems provides crucial insights into the fundamental principles governing quantum matter. From a materials research perspective, understanding and controlling these phases opens pathways to revolutionary technologies, including quantum computing, novel superconductors, and ultra-efficient electronic devices. This technical guide examines the theoretical foundation, experimental realization, and characterization methodologies for Wigner crystals and related quantum phases, framing them within the broader context of crystalline structure research and its applications to advanced material design [15] [17].

Theoretical Foundation: From Wigner's Prediction to Generalized Electron Crystals

The Original Wigner Crystal Concept

In 1934, Eugene Wigner made the revolutionary prediction that electrons could spontaneously crystallize into a regular lattice under specific conditions [16] [18]. This counterintuitive concept proposed that despite their identical negative charges, electrons could form an ordered quantum solid when their mutual Coulomb repulsion dominates over their kinetic energy. Wigner theorized that at low densities and extremely cold temperatures, electrons would become localized in a crystalline arrangement, now known as a Wigner crystal, rather than zipping independently through a material [16].

The formation condition can be understood through a dimensionless parameter, the Wigner-Seitz radius (rs), defined as the ratio of the average inter-electron spacing to the Bohr radius. Quantum Monte Carlo simulations indicate that the uniform electron gas crystallizes at rs ≈ 106 in three-dimensional systems and r_s ≈ 31 in two-dimensional systems [18]. In this regime, the potential energy from Coulomb repulsions significantly exceeds the kinetic energy, forcing electrons into an ordered lattice that minimizes the total energy. The resulting structure typically forms a triangular lattice in 2D and a body-centered cubic (bcc) lattice in 3D, independent of the underlying atomic lattice of the host material [18].

Evolution to Generalized Wigner Crystals and Molecular Phases

Recent theoretical and experimental advances have revealed that Wigner's original concept represents just one manifestation of a broader class of electron correlation-driven crystals. Generalized Wigner crystals exhibit different crystalline shapes, including stripes and honeycomb arrangements, beyond the triangular lattice predicted for traditional Wigner crystals [15]. These variations emerge when additional quantum effects and confinement potentials influence the electron organization.

A significant development came with the prediction and subsequent observation of Wigner molecular crystals, where artificial "molecules" composed of two or more electrons form highly ordered patterns within a superlattice [19]. Unlike the honeycomb arrangement of conventional Wigner crystals, these molecular crystals demonstrate how fine-tuning quantum confinement and electron interactions can produce diverse quantum phases with potentially tunable properties for materials design [19].

Experimental Breakthroughs and Direct Visualization

Historical Challenges and Technical Hurdles

For nearly 90 years after Wigner's prediction, direct experimental confirmation of electron crystals remained elusive because quantum fluctuations often disrupt crystalline order [16] [18]. Early experiments in the 1970s created "classical" electron crystals by spraying electrons on helium surfaces, but these electrons were too far apart to exhibit quantum-cohesive behavior [16]. Subsequent studies through the 1980s and 1990s provided indirect evidence through electronic transport measurements in semiconductor structures under magnetic fields, but these could not conclusively prove crystallization [16].

The primary challenges included:

- Material imperfections that could trap electrons, creating false signatures of crystallization

- The delicate nature of electron crystals, easily destroyed by measurement probes

- The difficulty of distinguishing between self-organized Wigner crystals and electron patterns induced by external potentials [16]

Direct Imaging of Wigner Crystals

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) Breakthroughs

Two independent research breakthroughs in 2024 successfully visualized Wigner crystals directly using advanced scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). The Princeton University team led by Ali Yazdani achieved the first direct imaging by creating exceptionally clean graphene samples cooled to a fraction of a degree above absolute zero [16]. Their approach used Bernal-stacked bilayer graphene (BLG) with applied perpendicular magnetic fields to create a two-dimensional electron system where tuning electron density triggered spontaneous crystallization [16].

Key observations from these experiments revealed:

- A triangular lattice configuration of electrons

- The crystal's lattice constant could be continuously tuned with electron density

- Significant quantum zero-point motion of electrons, covering about one-third the distance between neighbors despite their crystalline arrangement

- Crystal stability over an unexpectedly long range, contrary to prior assumptions [16]

Simultaneously, Berkeley Lab researchers captured images of a related quantum phase—the Wigner molecular crystal—in a twisted tungsten disulfide (tWS₂) moiré superlattice [19]. They overcame the technical hurdle of the STM tip destroying delicate electron configurations by minimizing the electric field from the tip. At a 58-degree twist angle between WS₂ layers, each 10-nanometer-wide unit cell confined two or three electrons, which formed an array of moiré electron molecules throughout the superlattice [19].

The 'Pinball' Phase: A Hybrid Quantum State

Building on these discoveries, physicists at Florida State University identified a previously unknown quantum phase dubbed the "pinball phase" or "quantum pinball phase" [15]. This hybrid state emerges during the transition between generalized Wigner crystals and electron liquids, where some electrons remain locked in fixed lattice positions while others move freely throughout the material [15].

In this unique state, the system exhibits both insulating and conducting behavior simultaneously. The stationary electrons maintain the crystalline framework, while the mobile electrons "bounce" between these fixed sites like pinballs, creating a dynamic quantum system with mixed characteristics [15]. This discovery provides crucial insights into how quantum phase transitions occur in strongly correlated electron systems and suggests new pathways for controlling electronic properties in advanced materials.

Methodologies: Experimental Protocols and Characterization Techniques

Sample Fabrication and Material Systems

Advanced material synthesis has been crucial for realizing and studying Wigner crystal phases. The table below summarizes key material systems and their roles in quantum phase research.

Table: Key Material Systems for Wigner Crystal Studies

| Material System | Structure and Properties | Role in Quantum Phase Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bernal-stacked Bilayer Graphene (BLG) | Two graphene layers in specific alignment; encapsulated in hBN | Provides ultra-clean 2D electron system with tunable density; enables direct imaging of Wigner crystals [16] |

| Twisted Tungsten Disulfide (tWS₂) | Bilayer WS₂ with ~58° twist angle; forms moiré superlattice | Creates periodic potential for confining electrons; enables Wigner molecular crystal formation [19] |

| Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (e.g., 1T-TaS₂) | Layered van der Waals materials with large r_s values | Hosts deeply correlated electron states; charge density waves with Wigner crystal characteristics [18] |

| Hexagonal Boron Nitride (hBN) | Atomically flat, insulating 2D material | Used as encapsulation layer to protect graphene and preserve electronic quality [16] [20] |

Experimental Characterization Techniques

Multiple advanced techniques have been employed to detect and characterize Wigner crystals and related quantum phases.

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) Protocol

The direct visualization of Wigner crystals requires meticulous STM methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Mechanically exfoliate and stack graphene layers between hBN flakes in an inert environment to create atomically clean interfaces without imperfections [16]

- Cooling and Stabilization: Cool samples to ultra-low temperatures (~10 mK) using dilution refrigerators to freeze thermal fluctuations [16] [20]

- Magnetic Field Application: Apply perpendicular magnetic fields (up to 14 T) to quench electron kinetic energy and enhance correlation effects [16] [20]

- Density Tuning: Use gate electrodes to continuously tune electron density in the 2D layer while monitoring with STM [16]

- Low-Impact Imaging: Minimize STM tip electric field to prevent disruption of delicate electron configurations [19]

- Data Acquisition: Map electron positions with atomic resolution; analyze lattice structure and quantum fluctuations [16]

Transport and Noise Measurement Protocols

Electronic transport measurements provide complementary evidence of Wigner crystallization:

- Low-Frequency Noise Spectroscopy: Measure current fluctuations in the frequency domain; enhanced noise at specific frequencies indicates depinning and sliding of electron crystals [20]

- Nonlinear Transport Measurements: Apply DC bias currents and measure voltage response; nonlinear behavior suggests collective electron motion [20]

- Temperature-Dependent Resistance: Track resistance changes with temperature; insulating behavior (dR/dT < 0) at low temperatures suggests electron localization [20]

Computational and Theoretical Methods

Theoretical investigations employ sophisticated numerical approaches:

- Exact Diagonalization: Powerful numerical technique for studying quantum Hamiltonians of small systems [15]

- Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG): Tensor network method for handling large quantum systems by compressing information [15]

- Quantum Monte Carlo Simulations: Stochastic approaches for calculating ground state properties of many-body systems [18]

Diagram: The integrated experimental and theoretical workflow for discovering and characterizing quantum electron phases, showing how theoretical predictions lead to material design, sample preparation, and multiple characterization approaches that collectively validate new quantum states.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Essential Research Materials for Quantum Phase Experiments

| Material/Reagent | Specifications | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Graphene | Bernal-stacked bilayer; >1mm² flake size; minimal defects | Primary platform for 2D electron system with tunable density and correlations [16] |

| Hexagonal Boron Nitride (hBN) | 10-50nm thickness; atomically flat surface | Encapsulation layer for electronic isolation and surface protection [16] [20] |

| Graphite Gates | 5-20nm thickness; patterned electrodes | Creates tunable electric fields for density control in 2D systems [20] |

| Transition Metal Dichalcogenides | WS₂, MoSe₂; specific twist angles | Forms moiré superlattices for confining electrons [19] [18] |

| Cryogenic Fluids | Liquid helium; dilution refrigerator compatible | Enables ultra-low temperature environments (<1K) for quantum phase stabilization [16] |

| STM Tips | Platinum-iridium or tungsten; atomically sharp | Scanning probe microscopy for direct visualization of electron arrangements [19] [16] |

Phase Diagrams and Quantum Transitions

Tuning Parameters and Phase Boundaries

The formation of Wigner crystals and related quantum phases depends critically on several external parameters that can be systematically tuned in experiments. The table below summarizes the key "quantum knobs" and their effects on phase transitions.

Table: Quantum Parameters for Phase Control

| Tuning Parameter | Experimental Control | Effect on Electron Phases |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Density (n) | Gate voltage application | Low densities favor Wigner crystallization; higher densities lead to melting into electron liquid [16] |

| Magnetic Field (B) | Perpendicular magnetic field (0-14 T) | Quenches kinetic energy via Landau quantization; enhances correlation effects [16] [20] |

| Temperature (T) | Cryogenic cooling (≥10 mK) | Thermal energy melts quantum crystals; low temperatures stabilize ordered phases [16] [20] |

| Moiré Potential | Twist angle in heterostructures | Creates artificial periodic confinement for electrons; enables molecular crystals [19] |

| Electric Displacement Field (D) | Dual-gate voltage application | Tunes layer polarization and electronic band structure [20] |

Characteristic Signatures of Quantum Phases

Different quantum phases exhibit distinct experimental signatures that enable their identification:

- Wigner Crystal Phase: Insulating behavior (resistance increases as temperature decreases); triangular lattice in direct imaging; nonlinear current-voltage response; noise signatures from depinning and sliding [16] [20]

- Wigner Molecular Crystal: Highly ordered pattern of electron molecules in moiré superlattices; each molecule contains 2-3 electrons [19]

- Pinball Phase: Coexistence of insulating and conducting behavior; some electrons fixed while others move freely; appears at intermediate densities during crystal-liquid transitions [15]

- Electron Liquid Phase: Metallic conduction; linear current-voltage response; no spatial ordering of electrons [15]

Diagram: Quantum phase transitions in two-dimensional electron systems, showing how electron density and the application of moiré potentials drive transitions between different quantum states, including the recently discovered pinball phase that emerges between Wigner crystals and electron liquids.

Implications for Materials Research and Applications

Fundamental Insights into Quantum Matter

The experimental realization and characterization of Wigner crystals and related phases represent landmark achievements in condensed matter physics, providing:

- Direct validation of a 90-year-old theoretical prediction about collective quantum behavior [16]

- New understanding of the competition between kinetic energy and electron interactions in quantum systems [15]

- Insights into quantum melting processes, where solids transition to liquids through novel intermediate phases [15]

- Experimental platforms for studying fundamental quantum phenomena like zero-point motion in crystalline systems [16]

Potential Technological Applications

The controlled manipulation of quantum electron phases holds significant promise for advanced technologies:

- Quantum Computing: Stable electron crystals could provide platforms for robust qubits with reduced decoherence; the pinball phase offers insights into controlling quantum state hybridization [15]

- Advanced Electronics: Tunable quantum phases in 2D materials could enable novel switching elements and transistors with exceptional efficiency [17]

- Quantum Sensing: The exquisite sensitivity of electron crystals to external perturbations could be harnessed for ultra-sensitive detectors [17]

- Energy Applications: Nonlinear electronic responses in these systems show potential for quantum energy harvesting devices [17]

The discovery and characterization of Wigner crystals, molecular variants, and the pinball phase represent transformative developments in quantum materials research. These findings not only validate long-standing theoretical predictions but also open expansive new frontiers for controlling and harnessing quantum phenomena in advanced materials. As research progresses toward room-temperature stabilization and three-dimensional systems, these quantum phases may fundamentally transform materials design paradigms across electronics, computing, and sensing technologies.

The Critical Link Between Crystal Structure and Physicochemical Properties in Pharmaceuticals

In the realm of drug development, the atomic and crystalline structure of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is not merely a structural attribute but a fundamental determinant of its therapeutic efficacy and manufacturability. The ability of a single API to exist in multiple crystalline forms, known as polymorphism, presents both challenges and opportunities for pharmaceutical scientists [21]. The selection of an appropriate solid form is critical, as it directly influences key pharmaceutical properties including solubility, stability, dissolution rate, bioavailability, and mechanical behavior during manufacturing [22] [21]. The notorious case of ritonavir in the 1990s, where a late-appearing polymorph necessitated product reformulation, underscores the vital importance of comprehensive solid-form understanding and control in pharmaceutical development [21]. This whitepaper examines the fundamental relationships between crystal structure and pharmaceutical properties, detailing contemporary methodologies for analysis, prediction, and optimization to de-risk drug development and enhance clinical performance.

Solid Forms and Their Pharmaceutical Implications

The solid-state landscape of an API encompasses a variety of forms, each with distinct structural features and property implications. Understanding this landscape is essential for rational formulation design.

Polymorphism and Crystal Habit

Polymorphs are different crystalline forms of the same pure substance, sharing identical chemical composition but differing in molecular packing (packing polymorphism) or molecular conformation (conformational polymorphism) [23]. These variations arise from differences in crystallization conditions such as solvent, temperature, and supersaturation [22]. The crystal habit refers to the external morphology of a crystal, which is influenced by the relative growth rates of different crystal faces. Different habits (e.g., needles, plates, prisms) of the same polymorph can significantly impact filterability, flowability, compactability, and punch sticking behavior during manufacturing [22].

Table 1: Classification of Pharmaceutical Solid Forms and Their Property Implications

| Solid Form | Structural Definition | Key Property Influences | Common Characterization Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphs | Different crystal structures of the same API | Stability, solubility, melting point, bioavailability | PXRD, DSC, SCXRD, ssNMR |

| Solvates/Hydrates | Crystal structures incorporating solvent/water molecules | Solubility, dissolution rate, hygroscopicity, stability | TGA, DVS, PXRD |

| Salts | Ionic complexes of ionizable APIs with counterions | Solubility, dissolution rate, stability, bioavailability | PXRD, DSC, dissolution testing |

| Cocrystals | Multi-component crystals with API and coformer(s) in defined stoichiometry | Solubility, stability, mechanical properties, bioavailability | SCXRD, PXRD, FTIR, DSC |

| Amorphous Solids | Disordered, non-crystalline arrangements | Enhanced solubility and dissolution, physical instability | PXRD, DSC, DVS |

Multicomponent Crystal Forms

Pharmaceutical cocrystals represent an increasingly important class of multicomponent solids consisting of an API and one or more pharmaceutically acceptable coformers in a definite stoichiometric ratio, connected by non-covalent bonds [24]. Unlike salts, cocrystals typically form between non-ionized components. Drug-drug cocrystals, where both components are APIs, offer particular promise for combination therapies by enabling synchronized release profiles and overcoming solubility differences between drugs [24]. For example, the temozolomide-myricetin cocrystal successfully diminished the solubility difference between the two drugs from approximately 280-fold to just 4.5-fold, optimizing their release characteristics for synergistic anti-glioma therapy [24].

Analytical Techniques for Solid-State Characterization

A comprehensive analytical strategy is essential for complete solid-form characterization, combining structural, thermal, and spectroscopic methods.

Structural and Morphological Analysis

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) remains the gold standard for definitive crystal structure determination, providing atomic-level insight into molecular packing, hydrogen bonding, and conformational details [24]. For powder samples, Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) serves as a fingerprinting technique for polymorph identification and quantification [24]. Solid-state Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (ssNMR) spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful complementary technique, particularly for structures that prove challenging for diffraction methods or for studying amorphous phases [25]. Recent advances in NMR crystallography enable complete structure determination of powdered solids at natural isotopic abundance, overcoming previous limitations in analyzing pharmaceutical powders [25].

For crystal morphology analysis, the CSD-Particle software suite predicts particle shape and surface facets, providing insights into parameters such as hydrogen-bond donors and acceptors, surface chemistry, charge distributions, and full interaction maps (FIMs) [26]. These parameters help researchers understand critical particle properties including wettability, stickiness, tabletability, and flow characteristics [26].

Thermal and Gravimetric Analysis

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) measures weight changes as a function of temperature, identifying desolvation, decomposition events, and hydrate stability [24]. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) detects thermal events such as melting points, glass transitions, and polymorphic transformations, providing crucial information about form stability and purity [24]. Dynamic Vapor Sorption (DVS) quantifies moisture uptake under controlled humidity conditions, essential for understanding hygroscopicity and physical stability during storage [24].

Table 2: Key Analytical Techniques for Solid-State Characterization of APIs

| Technique Category | Specific Techniques | Information Obtained | Experimental Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Analysis | SCXRD, PXRD | Crystal structure, polymorph identity, phase purity | Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å), typically 5-40° 2θ range for PXRD |

| Thermal Analysis | DSC, TGA | Melting point, polymorphic transitions, desolvation, decomposition | Typically 10°C/min heating rate under nitrogen atmosphere (50 mL/min) |

| Spectroscopic Analysis | FTIR, ssNMR | Molecular interactions, conformational details, hydrogen bonding | KBr pellet method for FTIR; magic-angle spinning for ssNMR |

| Surface & Morphological Analysis | CSD-Particle, DVS | Surface chemistry, hydrophilicity, crystal habit, hygroscopicity | Water probe for FIMoS analysis; 0-90% RH for DVS |

Computational Prediction and High-Throughput Screening

Advanced computational and experimental screening methods have revolutionized solid-form development, enabling more comprehensive and efficient exploration of the solid-state landscape.

Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP)

Computational polymorph prediction has made significant advances, now serving as a powerful complement to experimental screening for de-risking polymorphic changes during drug development [23]. Modern CSP methods integrate novel systematic crystal packing search algorithms with machine learning force fields in a hierarchical crystal energy ranking scheme [23]. Large-scale validation on diverse datasets demonstrates that these methods can not only reproduce experimentally known polymorphs but also suggest new low-energy polymorphs yet to be discovered, identifying potential risks to development [23]. A recent robust CSP method was validated on 66 molecules with 137 experimentally known polymorphic forms, correctly predicting all known polymorphs and ranking them among the top candidate structures [23].

Figure 1: Workflow for Hierarchical Crystal Structure Prediction

High-Throughput Experimental Screening

Encapsulated Nanodroplet Crystallisation (ENaCt) represents a breakthrough in high-throughput co-crystal discovery, enabling the rapid screening of vast experimental landscapes with minimal sample consumption [27]. This nanoscale approach facilitates access to binary, ternary, and even quaternary co-crystals through thousands of parallelized experiments exploring solvent, encapsulating oil, and stoichiometric variables [27]. In one demonstration, HTP ENaCt screening identified 18 possible binary co-crystal combinations of 3 small molecules and 6 co-formers through 3456 individual experiments, including 10 novel binary co-crystal structures [27]. When extended to higher-order co-crystal discovery, the method successfully identified ternary and quaternary co-crystals from 13,056 individual experiments, yielding 54 co-crystal structures in total [27].

Case Studies: Structural Modification for Property Enhancement

Case Study 1: Temozolomide-Myricetin Drug-Drug Cocrystal

A novel drug-drug cocrystal containing temozolomide (TMZ) and myricetin (MYR) in a 2:1:4 stoichiometry (2TMZ/MYR·4H2O) was developed to optimize the properties of both anti-glioma agents [24]. Crystal structure analysis revealed that the cocrystal lattice contains two TMZ molecules, one MYR molecule, and four water molecules, linked by hydrogen bonding interactions to form a three-dimensional network [24].

Experimental Protocol: The cocrystal was prepared via slurry and solvent evaporation techniques. For slurry conversion, TMZ (0.4 mmol, 77.6 mg) and MYR·H2O (0.2 mmol, 63.6 mg) were suspended in 1 mL of water and stirred at 500 rpm for 12 hours. The resulting solid was filtered and dried under vacuum for 48 hours, yielding the cocrystal in 92.07% yield [24].

Property Enhancement: The cocrystal hydrate exhibited favorable stability and tabletability compared to pure TMZ. Dissolution studies demonstrated that the maximum solubility of MYR in the cocrystal (176.4 μg/mL) was approximately 6.6 times higher than that of pure MYR·H2O (26.9 μg/mL), while the solubility of TMZ from the cocrystal (786.7 μg/mL) was remarkably lower than that of pure TMZ (7519.8 μg/mL) [24]. This balanced the solubility difference between the two drugs from ~280-fold to ~4.5-fold, potentially optimizing their simultaneous absorption [24].

Case Study 2: Cannabigerol Cocrystals with Enhanced Dissolution

Cannabigerol (CBG), a bioactive cannabinoid, presents formulation challenges due to its thermally unstable solid form with low solubility and needle habit [26]. Cocrystal screening yielded two promising forms: one with piperazine and another with tetramethylpirazine (the latter existing in three polymorphic forms), both in a 1:1 ratio [26].

Experimental Protocol: Comprehensive crystallization screening was conducted using 14 solvents and 2 solvent mixtures at room temperature with various pharmaceutically acceptable coformers. The resulting solid forms were characterized by PXRD, NMR, DSC, TGA, and intrinsic dissolution rate analysis [26].

Surface Analysis and Dissolution Correlation: Crystal structures were solved using SCXRD and compared with pure CBG. Comprehensive surface analysis using CSD-Particle revealed that while surface attachment energy and rugosity showed insignificant effects on dissolution, the concentration of unsatisfied hydrogen-bond donors displayed a positive correlation [26]. Two parameters showed very strong correlation to dissolution rate: the propensity for interactions with water molecules (determined by the maximum range in the full interaction maps on the surface for the water probe) and the difference in positive and negative electrostatic charges [26]. These predictive parameters offer significant utility in pharmaceutical development for anticipating dissolution behavior from structural data.

Figure 2: Cocrystal Engineering for Property Enhancement

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Solid-State Pharmaceutical Research

| Reagent/Material Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Solvents | Butanone, acetic acid, methanol, water | Media for crystal growth and polymorph screening | Purity >95% recommended; mixture screening enhances diversity |

| Coformers | Piperazine, tetramethylpirazine, amino acids, caffeine | Cocrystal formation with APIs | Pharmaceutically acceptable; diverse functional groups |

| Analytical Standards | Silicon for PXRD calibration, indium for DSC calibration | Instrument calibration and method validation | Certified reference materials ensure accuracy |

| Spectroscopic Materials | KBr for FTIR pellets, deuterated solvents for NMR | Sample preparation for spectroscopic analysis | Anhydrous grade essential for moisture-sensitive compounds |

| Encapsulation Materials | Fluorinated oils for ENaCt | Nanodroplet formation in high-throughput screening | Immiscible with crystallization solvents |

The critical link between crystal structure and physicochemical properties represents a fundamental principle in pharmaceutical development that bridges atomic-level arrangement and macroscopic product performance. Through strategic solid-form selection and engineering, including polymorphism control and cocrystal design, pharmaceutical scientists can significantly enhance API properties while derisking development. The ongoing integration of computational prediction with high-throughput experimental screening creates a powerful paradigm for comprehensive solid-form landscape assessment. As characterization technologies advance, particularly in surface analysis and NMR crystallography, our ability to understand and exploit structure-property relationships continues to grow, ultimately enabling the development of safer, more effective pharmaceutical products with optimized clinical performance.

Unveiling the Unseen: Advanced Techniques for Atomic-Scale Material Characterization

The determination of atomic and crystalline structures represents a fundamental pillar of materials research, driving innovations across pharmaceuticals, energy storage, and advanced materials design. For decades, X-ray diffraction (XRD) has served as the cornerstone technique for elucidating crystal structures with atomic resolution. However, traditional XRD analysis faces significant limitations when applied to nanocrystalline materials and powder samples, where structural information is obscured by overlapping peaks, preferred orientation effects, and limited crystallite size. These challenges are particularly pronounced in pharmaceutical development, where many active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and complex molecular compounds form only nanocrystals or exist solely in powder form, making them inaccessible to single-crystal XRD analysis [28].

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) technologies is now revolutionizing this landscape. By integrating physics-aware algorithms with experimental data, researchers can overcome traditional limitations in nanocrystal structure determination. This technical guide examines the cutting-edge methodologies, performance benchmarks, and experimental protocols that are transforming XRD into a powerful tool for atomic-scale structure determination from the most challenging nanocrystalline samples, thereby accelerating materials discovery and drug development workflows.

The AI Revolution in XRD Analysis

From Traditional Methods to Intelligent Systems

Traditional XRD analysis of nanocrystals and powder samples has relied heavily on the Rietveld refinement method, a powerful but labor-intensive approach that requires substantial expertise and manual intervention [29] [28]. This method involves iterative fitting of theoretical models to experimental data, a process that becomes increasingly challenging with complex multi-phase samples, nanoscale materials, and systems with subtle structural features. The fundamental limitation of conventional analysis stems from the information loss inherent in powder XRD patterns, where three-dimensional structural information is collapsed into a one-dimensional diffraction profile with overlapping peaks and ambiguous intensities [28].

The integration of AI and ML has introduced paradigm-shifting capabilities to this field:

- Deep learning architectures can learn joint structural distributions from experimentally stable crystals and their corresponding XRD patterns, enabling direct mapping between diffraction data and atomic arrangements [28]

- Generative models can produce atomically accurate structures that are subsequently refined against experimental XRD data, effectively solving the inverse problem of structure determination [28]

- Adaptive XRD approaches leverage real-time ML analysis to steer measurements toward the most informative regions, optimizing data collection for specific phase identification tasks [30]

Key AI Architectures for Nanocrystal Structure Determination

End-to-End Structure Determination Networks

The PXRDGen framework represents a breakthrough in end-to-end neural networks for crystal structure determination from powder XRD data. This system integrates three specialized modules that work in concert to achieve unprecedented accuracy [28]:

- Pre-trained XRD Encoder (PXE) Module: Utilizes contrastive learning to align the latent space of XRD patterns with crystal structures, with Transformer-based architectures achieving 92.42% top-10 hit rates for pattern-structure matching [28]

- Crystal Structure Generation (CSG) Module: Employs diffusion or flow-based generative models to produce candidate structures conditioned on XRD features and chemical formulas

- Rietveld Refinement (RR) Module: Performs automated refinement of generated structures against experimental XRD data

This integrated approach demonstrates remarkable performance, achieving 96% matching rates with ground-truth structures when using 20 generated samples on the MP-20 dataset of inorganic materials [28].

Autonomous and Adaptive XRD Systems

Machine learning algorithms have been successfully coupled with physical diffractometers to create closed-loop systems that integrate data collection and analysis. The adaptive XRD methodology employs a convolutional neural network (XRD-AutoAnalyzer) that not only identifies crystalline phases but also quantifies its own prediction confidence. This capability enables the system to make autonomous decisions about measurement parameters [30]:

- Selective resampling of specific 2θ regions where increased resolution will maximally improve classification confidence

- Dynamic expansion of scan ranges to capture additional distinguishing peaks

- Real-time steering of measurements toward features that improve model confidence, significantly enhancing detection of trace phases and short-lived intermediates

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI-Driven XRD Methods

| Method | Architecture | Key Innovation | Reported Accuracy | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PXRDGen [28] | Transformer encoder + diffusion/flow generator | End-to-end structure determination | 96% match rate (MP-20 dataset) | Powder nanocrystals |

| Adaptive XRD [30] | CNN + confidence estimation | Autonomous measurement steering | >50% confidence with 60% less scan time | Multi-phase mixtures |

| AutoMapper [31] | Optimization-based neural network | Domain knowledge integration | Robust performance across 3 oxide systems | Combinatorial libraries |

| XRD-AutoAnalyzer [30] | Ensemble classification | Phase identification from partial patterns | Accurate detection of trace phases (<5%) | In situ reaction monitoring |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Structure Determination Accuracy

The most significant benchmark for AI-powered XRD is its accuracy in determining crystal structures from powder diffraction data. The PXRDGen system has demonstrated remarkable performance on the MP-20 dataset, which contains experimentally stable inorganic materials with 20 or fewer atoms per primitive cell [28]:

- 82% matching rate with a single generated sample for valid compounds

- 96% matching rate when using 20 generated samples

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) generally less than 0.01, approaching the precision limits of traditional Rietveld refinement

These results indicate that AI-driven methods can achieve atomic-level accuracy competitive with established refinement techniques while operating orders of magnitude faster—seconds versus hours or days for conventional analysis [28].

Measurement Efficiency and Trace Phase Detection

Adaptive XRD methods have shown dramatic improvements in measurement efficiency while maintaining or enhancing detection capabilities. In comparative studies, ML-guided approaches achieved confident phase identification with 60% less scan time compared to conventional measurements [30]. This efficiency gain is particularly valuable for time-sensitive experiments, such as in situ monitoring of solid-state reactions where transient intermediate phases form and evolve rapidly.

For pharmaceutical applications, the enhanced sensitivity of AI-powered XRD enables detection of trace impurity phases present at concentrations below 5%, a critical capability for polymorph screening and quality control of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [30]. The integration of domain knowledge and thermodynamic constraints further ensures that identified structures are chemically reasonable, not just mathematically plausible [31].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics for AI-Powered XRD

| Performance Metric | Traditional XRD | AI-Powered XRD | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure solution time | Hours to days [28] | Seconds to minutes [28] | 10-100x |

| Trace phase detection limit | ~5-10% [30] | <5% [30] | 2x sensitivity |

| Multi-phase identification confidence | Manual interpretation | >50% autonomous confidence [30] | Quantitative metrics |

| Data collection efficiency | Fixed protocols | 60% reduction in scan time [30] | 2.5x more efficient |

| Light element detection | Challenging | Accurate hydrogen/lithium positioning [28] | Enhanced capability |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Autonomous Phase Mapping in Combinatorial Libraries

High-throughput materials discovery relies on efficient analysis of combinatorial libraries containing hundreds to thousands of compositionally varying samples. The AutoMapper workflow provides a robust protocol for automated phase mapping that integrates domain knowledge at multiple stages [31]:

Candidate Phase Identification

- Collect relevant candidate phases from crystallographic databases (ICDD, ICSD)

- Apply thermodynamic filtering to eliminate unstable phases (energy above hull >100 meV/atom)

- Group duplicate entries with similar compositions and diffraction patterns

Domain-Knowledge Integration

- Encode crystallographic constraints, composition consistency, and entropy regularization into loss function

- Incorporate texture information and polarization effects for accurate intensity calculation

- Utilize iterative fitting prioritizing samples with simpler phase compositions first

Validation and Refinement

- Cross-reference solutions with first-principles thermodynamic data

- Ensure chemical reasonableness of identified phase assemblages

- Provide texture information for major phases

This approach has been successfully applied to diverse oxide systems (V-Nb-Mn-O, Bi-Cu-V-O, Li-Sr-Al-O), correctly identifying complex phase relationships including the presence of α-Mn₂V₂O₇ and β-Mn₂V₂O₇ phases that were missed in previous analyses [31].

Adaptive XRD Measurement Protocol

For real-time steering of XRD measurements, the following protocol enables autonomous phase identification optimized for speed and confidence [30]:

Initial Rapid Scan

- Perform fast scan over 2θ = 10-60° with standard resolution

- Input pattern to XRD-AutoAnalyzer for preliminary phase prediction

- Calculate confidence metrics for all suspected phases

Confidence Evaluation

- If confidence >50% for all phases, terminate measurement

- If confidence <50%, proceed to targeted resampling

Selective Resampling

- Calculate Class Activation Maps (CAMs) for the two most probable phases

- Identify 2θ regions where CAM difference exceeds threshold (typically 25%)

- Rescan identified regions with increased resolution (slower scan rate)

Range Expansion (if needed)

- If confidence remains low after resampling, expand angular range in +10° increments

- Update predictions after each expansion using ensemble methods

- Continue until confidence threshold reached or maximum angle (140°) attained

This protocol has proven particularly effective for capturing short-lived intermediate phases during in situ reaction monitoring, where measurement speed is critical for observing transient species [30].

End-to-End Structure Determination with PXRDGen

For determining unknown crystal structures from powder XRD data, the PXRDGen framework provides a comprehensive protocol [28]:

Data Preprocessing

- Acquire high-quality PXRD pattern with appropriate signal-to-noise ratio

- Perform background correction and peak identification

- Extract chemical composition information

Contrastive Learning Alignment

- Utilize pre-trained XRD encoder to map diffraction pattern to latent space

- Align pattern representation with crystal structure features

- Generate conditional information for structure generation

Crystal Structure Generation

- Initialize with unit cell parameters from indexing or CellNet prediction

- Generate candidate structures using diffusion or flow-based models conditioned on XRD features

- Produce multiple candidate structures (typically 20) for evaluation

Automated Rietveld Refinement

- Refine generated structures against experimental XRD data

- Optimize atomic positions, thermal parameters, and preferred orientation

- Select structure with best fit to experimental pattern

This protocol has demonstrated particular effectiveness in addressing long-standing challenges in PXRD analysis, including accurate localization of light atoms (hydrogen, lithium) and differentiation of neighboring elements in the periodic table [28].

Computational Frameworks and Databases

Successful implementation of AI-powered XRD analysis requires access to specialized computational resources and data repositories:

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for AI-Powered XRD

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function in AI-XRD Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallographic Databases | ICDD, ICSD, Crystallography Open Database [31] | Source of candidate structures for phase identification and training data |

| Thermodynamic Data | Materials Project, OQMD [31] | Filtering of plausible phases based on thermodynamic stability |

| AI/ML Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch [28] | Implementation of deep learning models for structure determination |

| Specialized XRD Software | DIFFRAC.SUITE [32] | Automated measurement control and data collection |

| Generative Models | PXRDGen, DiffCSP, FlowMM [28] | Crystal structure generation from XRD patterns |

| High-Performance Computing | GPU clusters, cloud computing | Training and inference for compute-intensive models |

Experimental Infrastructure

The hardware foundation for AI-powered XRD studies includes both conventional and specialized instrumentation:

- Automated Diffractometers: Modern systems like the Bruker D8 and D6 series feature robotic sample changers and automated alignment capabilities, enabling high-throughput data collection [32]

- Synchrotron Beamlines: Provide high-brilliance X-ray sources for rapid data collection, particularly valuable for time-resolved studies and weakly scattering samples [31]

- In Situ Cells: Specialized sample environments for monitoring reactions under realistic conditions (temperature, pressure, gas atmosphere) [30]

- Portable XRD Systems: Handheld and desktop systems for field applications and rapid screening [33]

Integration with Materials Research Workflows

Closing the Materials Discovery Loop

AI-powered XRD represents a critical component in autonomous materials research platforms, enabling rapid structural characterization that informs subsequent experimental decisions. This capability is particularly valuable in combinatorial materials science, where composition-spread libraries can contain hundreds of distinct samples requiring efficient structural analysis [31]. The integration of XRD with robotic synthesis and property measurement systems creates closed-loop workflows that dramatically accelerate the discovery and optimization of new materials.

In pharmaceutical research, AI-enhanced XRD enables rapid polymorph screening and structure validation of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), many of which form nanocrystals or exist only in powder form [28]. The ability to determine complete molecular structures from powder data addresses a critical bottleneck in drug development, particularly for compounds that resist single-crystal growth.

Future Outlook and Emerging Capabilities

The field of AI-powered XRD is evolving rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future development:

- Increased Automation: End-to-end systems that integrate sample handling, data collection, and analysis with minimal human intervention [32]

- Multi-Modal Learning: Integration of XRD data with complementary characterization techniques (electron microscopy, spectroscopy) for comprehensive structural analysis [31]

- Explainable AI: Development of interpretable ML models that provide physical insights alongside structural solutions [30]

- Edge Computing: Deployment of lightweight ML models on portable XRD instruments for real-time analysis in field settings [33]

- Open Data Initiatives: Growing emphasis on data sharing and standardization to enable cross-study meta-analysis and model training [29]

As these capabilities mature, AI-powered XRD is poised to become an indispensable tool for researchers across materials science, chemistry, and pharmaceutical development, enabling atomic-level insights from increasingly complex and challenging sample systems. The integration of physical principles with data-driven approaches represents a powerful paradigm for advancing our understanding of crystalline materials and accelerating the development of new technologies.

For over a century, the diffraction limit of light has constrained optical microscopy, preventing the direct visualization of features smaller than approximately half the wavelength of light used for imaging. This fundamental barrier has profound implications for atomic and crystalline structure research, where scientists require nanoscale resolution to elucidate structure-property relationships in materials. While electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction—including powder diffraction for nanocrystalline materials—have been essential tools for atomic-scale analysis [34] [9], they often require specific sample conditions, vacuum environments, or extensive sample preparation that limits live observation and dynamic studies. The emergence of super-resolution optical microscopy techniques, particularly those enhanced by computational imaging, now provides unprecedented opportunities to bridge the gap between macroscopic observation and atomic-scale analysis, offering live imaging capabilities under ambient conditions for materials research.

The integration of advanced computational methods with optical microscopy has catalyzed a paradigm shift in nanoscale imaging. By combining photon statistics, structured illumination, and sophisticated algorithms, these techniques now enable researchers to overcome traditional optical limits while maintaining compatibility with diverse sample environments. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and applications of super-resolution optical microscopy with a specific focus on its relevance to materials characterization, particularly for investigating crystalline structures, defects, and nanoscale material properties that underlie macroscopic material behavior.

Fundamental Principles of Super-Resolution Microscopy

The Optical Diffraction Limit and Its Implications

The diffraction limit, formally described by Ernst Abbe in 1873, establishes that the minimum resolvable distance between two points in an optical microscope is approximately λ/2NA, where λ is the wavelength of light and NA is the numerical aperture of the objective lens. For visible light (λ ≈ 400-700 nm), this translates to a practical resolution limit of about 200-350 nm. This constraint has historically prevented optical microscopy from directly imaging nanoscale features critical to materials science, including crystal grain boundaries, dislocation networks, quantum dot assemblies, and the heterogeneous structure of advanced functional materials. While techniques such as X-ray diffraction and electron microscopy provide atomic-resolution structural information [34] [35], they cannot easily capture dynamic processes in functioning materials or devices.

Computational Approaches to Breaking the Diffraction Barrier

Computational super-resolution techniques overcome the diffraction barrier by exploiting additional information beyond what is directly captured in a conventional image. This can include temporal fluctuations of emitters, structured illumination patterns, or statistical properties of detected photons. The underlying principle involves acquiring a series of images containing complementary information and applying specialized algorithms to reconstruct a higher-resolution image. These methods effectively "deconvolve" the point spread function (PSF) of the optical system while incorporating additional physical constraints or prior knowledge about the sample, resulting in a final image with resolution beyond the classical diffraction limit [36] [37] [38].

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Super-Resolution Techniques

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Resolution Enhancement | Key Applications in Materials Science |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPI (Super-resolution Panoramic Integration) | Multifocal optical rescaling with synchronized line-scan readout | 2× resolution enhancement (~120 nm) [36] | High-throughput screening of crystalline powders, composite material analysis |

| QSIPS (Quantum Super-resolution Imaging by Photon Statistics) | Photon statistics measurement and cumulant analysis | Enhancement scaling with √j, where j is the highest-order central moments [38] | Quantum dot characterization, single-photon emitter mapping in 2D materials |

| Image Phase Alignment Super-sampling | Computational integration of multiple image phases | 2.71× resolution improvement [37] | Semiconductor defect analysis, thin-film quality control |

| SOFI (Super-resolution Optical Fluctuation Imaging) | Analysis of temporal fluorescence fluctuations | Limited enhancement in low-light conditions [38] | Nanoparticle tracking, dynamic process monitoring in materials |

Key Super-Resolution Techniques for Materials Research

Super-resolution Panoramic Integration (SPI)

Technical Principles and Implementation

SPI represents an advanced on-the-fly microscopy technique that enables instantaneous generation of sub-diffraction images concurrently with scalable, high-throughput screening. The method leverages multifocal optical rescaling, high-content sample sweeping, and synchronized line-scan readout while preserving minimal post-processing requirements. In practice, SPI incorporates concentrically aligned microlens arrays in both illumination and detection paths, contracting point-spread functions by a factor of √2, thus surpassing the diffraction limit without significant photon loss. The system employs a time-delay integration (TDI) sensor that synchronizes line-scan readout with corresponding sample motion, enabling full-specimen capture and instant formation of super-resolved images as samples are continuously introduced through the field of view [36].

For materials science applications, SPI's implementation of non-iterative rapid Wiener-Butterworth (WB) deconvolution provides an additional √2× enhancement in resolution, obtaining the full 2× improvement consistent with standard structured illumination techniques. This processing offers approximately 40-fold faster computation compared to traditional Richardson-Lucy deconvolution, reducing processing time to as little as 10 ms, making it particularly advantageous for high-throughput material analysis where large sample areas must be characterized efficiently [36].

Experimental Protocol for SPI

Sample Preparation: For material analysis, disperse powder samples or thin sections on standard glass slides. For nanocrystalline materials, use appropriate mounting media that preserves structural integrity.

System Configuration:

- Employ an epi-fluorescence microscope (e.g., Nikon Eclipse Ti2-U) equipped with a 100×, 1.45 NA oil immersion objective

- Configure concentrically aligned microlens arrays in both illumination and detection paths

- Calibrate TDI sensor synchronization with sample stage motion

Image Acquisition:

- Set illumination appropriate for the sample type (typically 488 nm or 561 nm laser lines)

- Implement continuous sample sweeping at optimized velocity (typically achieving 1.84 mm²/s)

- Synchronize line-scan readout (exceeding 10 kHz line rate) with sample motion

Image Reconstruction:

- Apply instantaneous TDI readout for initial image formation

- Implement non-iterative rapid WB deconvolution for additional resolution enhancement

- Validate resolution using fluorescent point emitters or reference nanostructures

Data Analysis:

- Quantify resolution using Fourier ring correlation or similar metrics

- For crystalline materials, analyze particle size distribution, defect density, and spatial organization