AI Foundation Models for Materials Discovery: Current State, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of foundation models (FMs) and their transformative impact on materials discovery.

AI Foundation Models for Materials Discovery: Current State, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of foundation models (FMs) and their transformative impact on materials discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles of these large-scale AI systems, their specific methodologies and applications in property prediction and molecular generation, the critical challenges and optimization strategies for real-world use, and a comparative analysis of their performance and validation. By synthesizing the current state of the art, this review aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to leverage FMs for accelerating the development of new materials, from battery components to therapeutic molecules.

What Are Foundation Models and How Are They Reshaping Materials Science?

The field of artificial intelligence has undergone a revolutionary transformation in its approach to scientific discovery, particularly in domains such as materials science. This evolution represents a fundamental shift from hand-crafted symbolic representations to data-driven learned representations [1]. Early expert systems in scientific research relied on human-engineered knowledge representations that captured domain-specific rules and relationships. While these systems incorporated valuable prior knowledge, they eventually revealed limitations in scalability and adaptability to complex, high-dimensional scientific problems [1]. The paradigm began to shift with the growing availability of computational resources, particularly GPUs, and the emergence of deep learning approaches that could learn representations directly from data [1]. This transition set the stage for the most significant breakthrough: the invention of the transformer architecture in 2017, which enabled the development of foundation models that are now reshaping the scientific discovery process [1] [2].

Within materials discovery, this evolution has proven particularly impactful. The nuanced task of identifying and developing new materials with specific properties has traditionally relied on expert intuition, expensive simulations, and trial-and-error experimentation [3]. The application of foundation models—models trained on broad data that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks—is now accelerating this process through rapid property prediction, inverse design, and synthesis planning [1] [2]. This whitepaper examines the technical journey from expert systems to transformers, with a focused analysis of how foundation models are transforming the current state of materials discovery research.

Historical Perspective: From Expert Systems to Learned Representations

The Era of Expert Systems and Hand-Crafted Features

Early AI systems for scientific applications were dominated by expert systems that operated on hand-crafted symbolic representations [1]. These systems encoded human knowledge through carefully designed rules and features, which served as an effective solution for limited data environments. In materials science, this approach manifested in manually constructed descriptors based on domain knowledge, such as elemental properties, structural characteristics, and process parameters [4]. The strength of this approach lay in its ability to incorporate substantial prior scientific knowledge and provide interpretable results. For instance, materials experts developed quantitative descriptors like the "tolerance factor" for identifying topological semimetals in square-net compounds, building on chemical intuition and structural understanding [3].

However, these systems faced significant limitations. The process of manual feature engineering was time-consuming, required deep domain expertise, and often failed to capture the complex, non-linear relationships inherent in materials behavior [1] [4]. Furthermore, the explicit inclusion of human biases in feature design constrained the potential for discovering novel patterns and materials outside established scientific paradigms. As materials datasets grew in size and complexity, these limitations became increasingly apparent, creating the need for more automated, scalable approaches to representation learning [1].

The Rise of Data-Driven Approaches and Deep Learning

The expansion of materials databases and increased computational capabilities facilitated a shift toward data-driven representation learning [1] [4]. Deep learning approaches began to automatically learn relevant features and patterns directly from data, reducing the reliance on manual feature engineering. This transition aligned with the growing emphasis on high-throughput computation and experimentation within the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) framework, which sought to accelerate materials development through computational tools, experimental facilities, and digital data [4].

The workflow of materials machine learning evolved to encompass data collection, feature engineering, model selection and evaluation, and model application [4]. During this period, feature engineering remained an essential component, but the focus shifted toward automated descriptor selection and dimensionality reduction techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) [4]. The Sure Independence Screening Sparsifying Operator (SISSO) method emerged as a powerful approach for feature transformation and selection in materials science applications [4].

Table 1: Evolution of AI Approaches in Materials Science

| Era | Primary Approach | Key Technologies | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert Systems | Hand-crafted symbolic representations | Domain-knowledge descriptors, Rule-based systems | High interpretability, Incorporates prior knowledge | Scalability issues, Human bias, Limited discovery potential |

| Early Machine Learning | Automated feature engineering with traditional ML | PCA, LDA, SISSO, Feature selection algorithms | Reduced manual feature engineering, Handles larger datasets | Limited to available descriptors, Still requires significant feature engineering |

| Deep Learning | Learned representations from data | Neural networks, Graph neural networks | Automatic feature learning, Handles complex patterns | Large data requirements, Limited interpretability |

| Foundation Models | Transfer learning with self-supervision | Transformer architectures, Large language models | Generalizable representations, Few-shot learning, Multi-task capability | Computational intensity, Data quality dependencies |

Despite these advances, the materials science domain continued to face the fundamental challenge of small data [4]. Unlike domains such as image recognition or natural language processing, materials data often remains limited due to the high cost of experimental validation and computational simulation. This constraint necessitated specialized approaches for small data machine learning, including transfer learning, active learning, and data augmentation techniques [4].

The Transformer Revolution and Foundation Models

Architectural Foundations: Transformer Mechanisms

The transformer architecture, introduced in 2017, represents the pivotal innovation that enabled the modern era of foundation models [1]. Its core innovation lies in the self-attention mechanism, which allows the model to weigh the importance of different parts of the input sequence when processing each element. This architecture fundamentally differs from previous sequence models by enabling parallel processing of entire sequences and capturing long-range dependencies more effectively than recurrent neural networks [1].

The original transformer architecture encompassed both encoding and decoding components, but subsequent developments have seen the emergence of specialized encoder-only and decoder-only architectures [1]. Encoder-only models, such as those based on the Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) architecture, focus on understanding and representing input data, generating meaningful representations for further processing or predictions [1]. Decoder-only models, exemplified by the Generative Pretrained Transformer (GPT) family, specialize in generating new outputs by predicting and producing one token at a time based on given input and previously generated tokens [1].

Foundation Models: Definition and Capabilities

Foundation models are defined as "models that are trained on broad data (generally using self-supervision at scale) that can be adapted (e.g., fine-tuned) to a wide range of downstream tasks" [1]. These models typically follow a two-stage development process: unsupervised pre-training on large amounts of unlabeled data followed by task-specific fine-tuning with typically smaller labeled datasets [1]. An optional alignment process further refines model outputs to align with user preferences, such as generating chemically valid molecular structures with improved synthesizability in materials science applications [1].

The power of foundation models lies in their transfer learning capabilities—the knowledge gained during pre-training on diverse datasets can be efficiently applied to specialized scientific domains with limited task-specific data [1]. This approach has proven particularly valuable in materials science, where high-quality labeled data is often scarce and expensive to acquire [4]. The separation of representation learning from downstream tasks enables researchers to leverage general-purpose models trained on massive chemical databases and adapt them to specific property prediction, molecular generation, or synthesis planning tasks [1].

Table 2: Foundation Model Types and Their Applications in Materials Discovery

| Model Type | Architecture | Primary Function | Materials Science Applications | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Only | BERT-based | Understanding and representing input data | Property prediction, Materials classification | Chemical BERT, MatBERT |

| Decoder-Only | GPT-based | Generating sequential outputs | Molecular generation, Synthesis route planning | ChemGPT, MatGPT |

| Encoder-Decoder | Original Transformer | Sequence-to-sequence tasks | Reaction prediction, Materials transformation | Molecular transformer models |

Foundation Models in Materials Discovery: Current State Assessment

Data Extraction and Curation

The effectiveness of foundation models in materials discovery hinges on the availability of large-scale, high-quality datasets [1]. Chemical databases such as PubChem, ZINC, and ChEMBL provide valuable structured information commonly used to train chemical foundation models [1]. However, these sources often face limitations in scope, accessibility due to licensing restrictions, dataset size, and potential biases in data sourcing [1].

A significant volume of materials information exists within scientific literature, patents, and reports, necessitating advanced data extraction techniques [1]. Traditional approaches have focused on text-based extraction using named entity recognition (NER), but modern methods increasingly leverage multimodal learning to integrate information from text, tables, images, and molecular structures [1]. For instance, Vision Transformers and Graph Neural Networks can identify molecular structures from images in scientific documents, while specialized algorithms like Plot2Spectra can extract data points from spectroscopy plots in literature [1].

The data extraction process typically focuses on two primary problems: identifying materials themselves (entity recognition) and associating described properties with these materials (relationship extraction) [1]. Recent advances in large language models have significantly improved the accuracy of schema-based extraction for property association [1]. This comprehensive data curation pipeline enables the construction of the extensive, high-quality datasets necessary for effective foundation model training in materials science.

Property Prediction

Property prediction from structure represents a core application of foundation models in materials discovery [1]. Traditional methods range from highly approximate quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) methods to computationally expensive physics-based simulations [1]. Foundation models offer a powerful alternative by creating predictive capabilities based on transferable core components, enabling more efficient data-driven inverse design [1].

Most current property prediction models utilize 2D molecular representations such as SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) or SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings), which can lead to the omission of critical 3D conformational information [1]. This bias toward 2D representations stems largely from the greater availability of large-scale datasets for these formats, with resources like ZINC and ChEMBL offering datasets of approximately 10^9 molecules—a scale not readily available for 3D structural data [1]. Inorganic solids, such as crystals, represent an exception where property prediction models more commonly leverage 3D structures through graph-based or primitive cell feature representations [1].

Encoder-only models based on the BERT architecture currently dominate the property prediction landscape, although GPT-based architectures are gaining prevalence [1]. The reuse of core models and architectural components represents a significant strength of the foundation model approach, enabling efficient knowledge transfer across related tasks and reducing the computational resources required for specialized applications [1].

Generative Design and Synthesis Planning

Beyond property prediction, foundation models enable the generative design of novel materials and synthesis pathways [2]. Decoder-only models, specialized for output generation, can propose new molecular structures with desired properties by predicting sequences in chemical notation systems like SMILES or SELFIES [1]. This capability facilitates inverse design—starting from desired properties and generating candidate structures that exhibit those properties [2].

In synthesis planning, foundation models support reaction optimization and the prediction of synthetic pathways [2]. These models can leverage knowledge from extensive chemical reaction databases to propose feasible synthesis routes for novel materials, significantly reducing the experimental trial-and-error typically required [2]. The integration of foundation models with autonomous laboratories creates a closed-loop discovery system where models propose candidate materials, robotic systems execute synthesis and characterization, and experimental results feedback to refine the models [2].

Case Study: ME-AI Framework for Topological Materials

The Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence (ME-AI) framework exemplifies the powerful synergy between human expertise and foundation models [3]. This approach translates experimental intuition into quantitative descriptors extracted from curated, measurement-based data [3]. In a landmark study, researchers applied ME-AI to 879 square-net compounds described using 12 experimental features, training a Dirichlet-based Gaussian process model with a chemistry-aware kernel [3].

The framework successfully reproduced established expert rules for identifying topological semimetals (TSMs) and revealed hypervalency as a decisive chemical lever in these systems [3]. Remarkably, a model trained exclusively on square-net TSM data correctly classified topological insulators in rocksalt structures, demonstrating unexpected transferability [3]. This case highlights how foundation models can embed expert knowledge, offer interpretable criteria, and guide targeted synthesis, accelerating materials discovery across diverse chemical families [3].

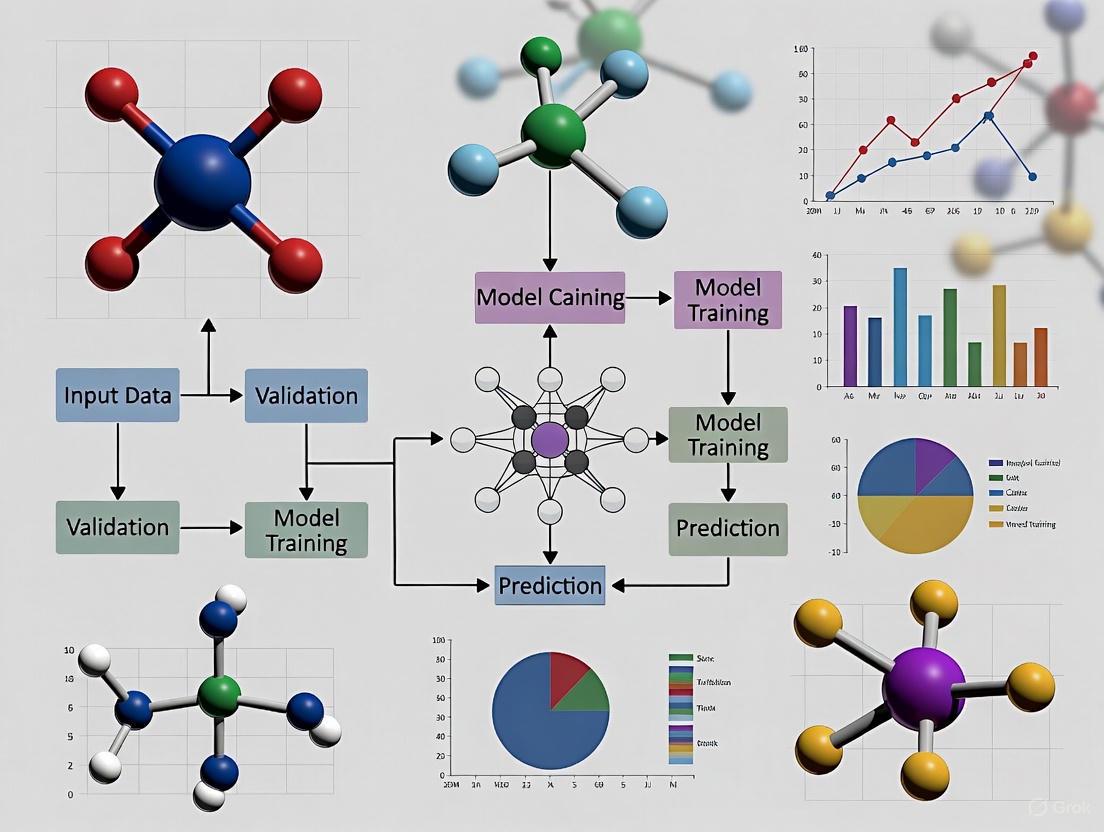

Diagram 1: ME-AI workflow for materials discovery

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Collection and Curation Protocols

Effective application of foundation models in materials discovery requires rigorous data collection and curation protocols. The ME-AI framework exemplifies best practices through its meticulous approach to dataset construction [3]. Researchers curated a dataset of 879 square-net compounds from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), focusing on compounds belonging to the 2D-centered square-net class across multiple structure types including PbFCl, ZrSiS, PrOI, Cu2Sb, and related variants [3].

The expert labeling process represents a critical component of data curation, where domain knowledge is systematically encoded into the dataset [3]. When experimental or computational band structure was available (56% of the database), materials were labeled through visual comparison to a square-net tight-binding model band structure [3]. For alloys (38% of the database), chemical logic was applied based on labels of parent materials, while stoichiometric compounds without available band structure information (6%) were labeled through cation substitution logic [3]. This multi-faceted labeling approach ensures comprehensive knowledge capture while maintaining scientific rigor.

Feature Engineering and Descriptor Selection

Feature engineering for materials foundation models involves selecting optimal descriptor subsets from original features through preprocessing, selection, dimensionality reduction, and combination [4]. The ME-AI framework employed 12 primary features (PFs) categorized as atomistic or structural descriptors [3]. Atomistic features included electron affinity, Pauling electronegativity, valence electron count, and estimated face-centered cubic lattice parameter of the square-net element [3]. Structural features encompassed crystallographic characteristic distances (dsq and dnn) [3].

To handle the challenge of small data, the ME-AI implementation utilized a Gaussian process (GP) model with a Dirichlet-based kernel specifically designed for materials applications [3]. This approach outperformed simpler dimensional reduction techniques like principal component analysis (PCA), which failed to incorporate prior knowledge of labels, and avoided the overfitting risks associated with neural networks on small datasets [3]. The chemistry-aware kernel enabled effective learning from limited examples while maintaining interpretability—a crucial consideration for scientific discovery.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Materials Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application in Materials Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | PubChem, ZINC, ChEMBL | Provide structured chemical information | Training data for foundation models, Reference information for validation |

| Materials Databases | ICSD, Materials Project | Curated materials data with properties | Source of training examples, Benchmarking model performance |

| Feature Generation Tools | Dragon, PaDEL, RDkit | Generate molecular descriptors | Convert structural information to machine-readable features |

| Specialized Extraction Tools | Plot2Spectra, DePlot | Extract data from literature figures | Convert graphical data into structured formats for model training |

| Representation Formats | SMILES, SELFIES | Text-based molecular representations | Standardized inputs for molecular foundation models |

Model Training and Validation Framework

The ME-AI case study demonstrates a sophisticated training and validation approach tailored for small data environments [3]. The Dirichlet-based Gaussian process model incorporated a chemistry-aware kernel that embedded domain knowledge directly into the learning process [3]. This design enabled the model to not only reproduce known structural descriptors (the "tolerance factor") but also identify new emergent descriptors, including one aligned with classical chemical concepts of hypervalency and the Zintl line [3].

Validation extended beyond conventional cross-validation to include cross-family generalization tests [3]. Remarkably, the model trained exclusively on square-net topological semimetal data successfully classified topological insulators within rocksalt structures, demonstrating unexpected transferability across material families [3]. This rigorous validation approach provides a template for assessing the real-world utility of foundation models in materials discovery, particularly their ability to generalize beyond their immediate training data.

Diagram 2: Multimodal data extraction pipeline

Future Directions and Challenges

Technical Challenges and Limitations

Despite significant progress, foundation models for materials discovery face several persistent challenges. The small data problem remains a fundamental constraint, as materials data acquisition continues to require high experimental or computational costs [4]. Most materials machine learning still operates in the small data regime, necessitating specialized approaches such as transfer learning, active learning, and data augmentation [4].

Model interpretability and explainability present another significant challenge [2]. While foundation models offer powerful predictive capabilities, understanding the underlying reasoning behind their predictions is crucial for scientific acceptance and insight generation [2]. The development of explainable AI techniques tailored for materials science applications is essential for building trust in model predictions and extracting new scientific understanding from these models [2].

Data quality and standardization issues also persist across materials databases [2]. Discrepancies in naming conventions, ambiguous property descriptions, and inconsistent experimental conditions can propagate errors into downstream models [1]. Furthermore, the predominance of 2D molecular representations in current foundation models limits their ability to capture critical 3D structural information that often determines material properties and behavior [1].

Emerging Opportunities and Research Frontiers

The integration of foundation models with autonomous laboratories represents a particularly promising direction for future research [2]. This combination enables closed-loop discovery systems where models propose candidate materials, robotic systems execute synthesis and characterization, and experimental results feedback to refine the models in real time [2]. Such systems have the potential to dramatically accelerate the materials development cycle while reducing human effort and resource consumption.

The development of multimodal foundation models capable of processing diverse data types—including text, images, spectra, and structural information—will significantly enhance materials discovery capabilities [1]. These models can integrate information from scientific literature, experimental characterization data, and computational simulations to develop more comprehensive materials representations [1]. Advances in transfer learning will further enable knowledge acquired from data-rich chemical domains to be applied to specialized materials families with limited data [4].

Finally, the incorporation of physical principles and constraints directly into foundation models represents an important frontier for improving model accuracy and scientific consistency [2]. Hybrid approaches that combine data-driven learning with physics-based modeling can leverage the strengths of both paradigms, enabling more robust predictions that adhere to fundamental scientific laws [2]. This alignment of data-driven innovation with physical knowledge will be essential for realizing the full potential of foundation models in scientific discovery.

The evolution from expert systems to transformer-based foundation models represents a paradigm shift in how artificial intelligence is applied to scientific discovery, particularly in the field of materials science. This journey has transitioned from human-engineered representations to data-driven learned representations, culminating in models that can transfer knowledge across diverse tasks and domains. Foundation models are now demonstrating significant impact across the materials discovery pipeline—from data extraction and property prediction to generative design and synthesis planning.

The current state of research reveals both impressive capabilities and persistent challenges. While foundation models enable more efficient and accelerated materials discovery, issues of data scarcity, model interpretability, and integration with physical principles remain active research areas. The continuing evolution of these technologies, particularly through integration with autonomous experimentation and multimodal learning, promises to further transform the scientific discovery process. By aligning computational innovation with practical experimental implementation, foundation models are poised to turn autonomous materials discovery into a powerful engine for scientific and technological advancement.

Foundation models have emerged as a transformative paradigm in artificial intelligence, achieving state-of-the-art performance across natural language processing, computer vision, and increasingly, scientific domains including materials science [5]. These models are characterized by a two-stage lifecycle: pre-training, where models learn general, high-capacity representations from massive and diverse datasets, and adaptation (including fine-tuning), where these representations are specialized for specific tasks, domains, or modalities [5]. In the context of materials discovery, foundation models leverage the growing abundance of materials data to accelerate the prediction of material properties, guide synthesis planning, and ultimately enable the inverse design of novel materials with targeted characteristics [2] [6].

The adoption of foundation models represents a shift from traditional, narrowly-focused machine learning approaches to more generalized, multi-purpose models that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks in computational and experimental materials science. This guide provides a technical examination of the core concepts of foundation models—pre-training, fine-tuning, and adaptation—within the current research landscape of materials discovery, complete with experimental methodologies, data presentation, and visualization to equip researchers with the knowledge to leverage these powerful tools.

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is a Foundation Model?

A foundation model is defined as "a model trained on broad data (generally using self-supervision at scale) that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks" [7]. This adaptation occurs primarily through two mechanisms:

- Prompting (in-context learning): The model's behavior and capabilities are influenced through specific inputs, while its weights (parameters) remain unchanged.

- Fine-tuning: The model's weights are modified through additional training on task-specific data, resulting in a new model artifact specialized for particular applications [7].

While transformer-based generative models currently dominate this category, the "foundational" aspect refers not to a specific architecture, but to the model's broad applicability across diverse tasks [7].

The Three Pillars: Pre-training, Fine-tuning, and Adaptation

Table: Core Components of Foundation Models

| Component | Definition | Primary Objective | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | Initial training phase on broad, unlabeled data using self-supervised learning | Learn general, transferable representations of the input space | Massive, diverse datasets (e.g., extensive materials databases) |

| Fine-tuning | Subsequent training phase on smaller, task-specific labeled datasets | Specialize the model for particular applications or domains | Curated, labeled datasets for target tasks |

| Adaptation | Broader process of making a model suitable for specific tasks, including fine-tuning and prompting | Achieve optimal performance on target applications with minimal computational cost | Varies by method; can include labeled data or well-crafted prompts |

In materials science, this paradigm enables models to learn fundamental principles from large-scale computational and experimental databases, then specialize for specific prediction tasks such as identifying topological materials or optimizing synthesis pathways [3] [6].

Foundation Models for Materials Discovery: Current Research Landscape

The application of foundation models in materials science is rapidly advancing, driven by growing materials databases and the need to accelerate discovery cycles. Current research demonstrates several promising directions:

Multimodal Learning for Materials

The Multimodal Learning for Materials (MultiMat) framework represents a cutting-edge approach, training foundation models by aligning multiple modalities of materials data in a shared latent space [6]. This framework incorporates:

- Crystal structure encoded using graph neural networks (GNNs)

- Density of states (DOS) encoded via Transformer architectures

- Charge density processed with 3D-CNNs

- Textual descriptions of crystals generated by tools like Robocrystallographer [6]

This multimodal approach enables more robust material representations that can be transferred to various downstream tasks, including property prediction and novel material discovery through latent space similarity searches [6].

Integrating Expert Knowledge

Beyond data-driven approaches, frameworks like Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence (ME-AI) demonstrate how expert intuition can be formalized within machine learning systems [3]. By curating experimental datasets based on domain knowledge and using chemistry-aware kernels in Gaussian process models, ME-AI successfully identified hypervalency as a decisive chemical lever in topological semimetals while recovering known expert-derived structural descriptors [3].

Self-Driving Laboratories

Foundation models are increasingly deployed in autonomous experimentation systems. Recent advances in self-driving labs have demonstrated techniques that collect at least 10 times more data than previous approaches through dynamic flow experiments, where chemical mixtures are continuously varied and monitored in real-time [8]. This creates a "full movie of the reaction" rather than single snapshots, dramatically accelerating materials discovery while reducing chemical consumption and waste [8].

Table: Quantitative Performance of AI-Driven Materials Discovery Approaches

| Method/Platform | Data Efficiency | Key Performance Metric | Application Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| MultiMat Framework [6] | Leverages multi-modal pre-training | State-of-the-art property prediction; interpretable emergent features | General crystalline materials |

| ME-AI [3] | 879 compounds with 12 experimental features | Identifies hypervalency descriptor; transfers across structure types | Topological semimetals and insulators |

| Dynamic Flow Self-Driving Labs [8] | 10x more data than steady-state systems | Identifies optimal materials on first try post-training; reduces time and chemical consumption | Colloidal quantum dots (CdSe) |

| Materials Project Synthesizability [9] | Large-scale computational screening | Predicts synthesizability via energy window analysis; validates against known materials | Battery, solar, and structural materials |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multimodal Pre-training Protocol (MultiMat)

The MultiMat framework employs a sophisticated pre-training methodology adapted from contrastive learning approaches:

Data Curation and Modalities:

- Source data from the Materials Project database [6] [9]

- Four core modalities: crystal structure, density of states (DOS), charge density, and textual descriptions

- Textual descriptions generated automatically using Robocrystallographer [6]

Encoder Architectures:

- Crystal structure: PotNet (a state-of-the-art Graph Neural Network)

- DOS: Transformer-based encoder

- Charge density: 3D-CNN architecture

- Text: Frozen MatBERT model (materials-specific BERT) [6]

Training Procedure:

- Modality encoders trained to project different views of the same material to nearby points in a shared latent space

- Contrastive loss function encourages alignment of embeddings from the same material while separating embeddings from different materials

- Pre-training is self-supervised, requiring no manual labeling of materials [6]

Expert-in-the-Loop Training Protocol (ME-AI)

The ME-AI framework integrates materials expertise directly into the training process:

Data Curation:

- Curate 879 square-net compounds from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD)

- Define 12 primary features including electron affinity, electronegativity, valence electron count, and structural parameters [3]

Expert Labeling:

- 56% of database labeled through visual comparison of band structure to tight-binding models

- 38% labeled using chemical logic and parent material relationships

- 6% labeled via stoichiometric relationships and cation substitution logic [3]

Model Architecture and Training:

- Dirichlet-based Gaussian process model with chemistry-aware kernel

- Model trained to reproduce expert-derived "tolerance factor" while discovering new descriptors

- Validation through transfer learning to topological insulators in rocksalt structures [3]

Self-Driving Lab Implementation

Autonomous materials discovery employs foundation models within robotic experimentation platforms:

Hardware Configuration:

- Continuous flow reactors with microfluidic channels

- Real-time in situ characterization sensors

- Automated precursor mixing and delivery systems [8]

Software and AI Infrastructure:

- Machine learning algorithms that predict next experiments based on streaming data

- Dynamic flow experiments that continuously vary chemical mixtures

- Data collection at 0.5-second intervals (vs. hourly in traditional approaches) [8]

Workflow Optimization:

- Traditional steady-state: System idle during reactions (up to 1 hour per experiment)

- Dynamic flow: Continuous operation with real-time characterization

- Result: 10x data acquisition efficiency and reduced chemical consumption [8]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for Foundation Model Research in Materials Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function/Role | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Databases | Materials Project [9], ICSD [3] | Source of computed and experimental materials data; training corpus for pre-training | Public API (Materials Project), Licensed Access (ICSD) |

| Computational Resources | NERSC, Lawrencium, Savio [9] | High-performance computing for large-scale pre-training and materials simulations | Institutional allocation, DOE funding |

| Encoder Architectures | PotNet [6], Transformers [6], 3D-CNN [6] | Network designs for processing specific material modalities (crystal structures, spectra, density) | Open-source implementations |

| Benchmarking Platforms | AI4Mat Workshop [10] | Community standards and challenges for evaluating materials foundation models | Conference participation, open submissions |

| Autonomous Lab Hardware | Continuous flow reactors [8] | Robotic platforms for experimental validation and data generation | Custom fabrication, specialized equipment |

Future Directions and Challenges

As foundation models for materials discovery mature, several critical challenges and opportunities emerge:

Data Quality and Standardization: The field requires improved data standards, especially for experimental results, including both positive and negative outcomes to avoid bias in training data [2].

Explainability and Interpretability: While foundation models offer strong predictive performance, enhancing their transparency and physical interpretability remains crucial for scientific adoption [2] [6].

Bridging Computational and Experimental Gaps: Methods for predicting synthesizability, like the "synthesizability skyline" approach that calculates energy windows for viable materials, are essential for translating virtual discoveries to laboratory realization [9].

Sustainability and Efficiency: The computational intensity of pre-training large models drives innovation in application-specific semiconductors and energy-efficient AI, with sustainability becoming a key consideration in model development [11].

The integration of foundation models with autonomous laboratories creates a powerful feedback loop where AI not only predicts materials but also designs and interprets experiments, accelerating the entire discovery pipeline from computational prediction to synthesized material [2] [8]. This synergy between AI and experimentation promises to transform materials science from a largely empirical discipline to a more predictive and engineered field.

In the evolving landscape of artificial intelligence for scientific discovery, foundation models have emerged as powerful tools capable of accelerating research across diverse domains, including materials science and drug development [1]. These models, trained on broad data, can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks, offering unprecedented capabilities for property prediction, molecular generation, and synthesis planning [1]. The architectural choice between encoder-only and decoder-only models represents a fundamental decision point in designing AI systems for scientific applications, with each paradigm offering distinct advantages and limitations for specific research workflows [12].

This technical guide examines the core architectural differences between encoder-only and decoder-only models within the context of materials discovery research. We explore their theoretical foundations, practical implementations, performance characteristics, and emerging hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both architectures to address complex scientific challenges.

Core Architectural Frameworks

Foundational Concepts and Self-Attention Mechanism

At the heart of both encoder-only and decoder-only models lies the transformer architecture, which revolutionized natural language processing and has since been adapted for scientific data [13]. The key innovation is the self-attention mechanism, which allows the model to weigh the importance of different elements in a sequence when processing each element [13].

Self-attention operates through three vectors derived from each token's embedding: Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V). The mechanism calculates attention scores by taking the dot product of a token's Query vector with the Key vectors of all tokens, applies softmax to normalize these scores into probabilities, and computes a weighted sum of Value vectors based on these probabilities [13]. This process enables the model to capture contextual relationships across the entire input sequence, a capability crucial for understanding complex scientific data.

Multi-head attention extends this concept by employing multiple parallel attention mechanisms, allowing the model to capture different types of relationships and patterns within the sequence [13]. The outputs from all attention heads are concatenated and linearly transformed to produce a comprehensive, nuanced representation of the input.

Encoder-Only Architecture

Encoder-only models specialize in understanding and encoding input sequences into rich contextual representations [13]. These models process input data through a stack of identical layers, each containing two sub-layers: multi-head self-attention and position-wise feedforward neural networks [1] [13].

The self-attention mechanism in encoder-only models is typically bidirectional, meaning each token can attend to all other tokens in the sequence in both directions [13]. This comprehensive contextual understanding makes encoder-only models particularly valuable for scientific tasks that require deep analysis of input data, such as property prediction from molecular structure or spectral interpretation [1].

A prominent example of encoder-only mastery is BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), which introduced bidirectional self-attention to consider both left and right contexts when encoding tokens [13]. In materials science, encoder-only models based on the BERT architecture have been widely applied to property prediction tasks [1].

Decoder-Only Architecture

Decoder-only models excel at autoregressive generation, predicting each token in a sequence based on the preceding tokens [12] [13]. These models employ masked self-attention, which ensures each token can only attend to previous tokens in the sequence, preventing information leakage from future tokens during generation [12].

The autoregressive nature of decoder-only models makes them ideally suited for tasks that involve sequential generation, such as designing novel molecular structures or planning synthesis routes [1] [13]. These models generate outputs token by token, maintaining coherence and context throughout the sequence by using the "right shift" phenomenon, where generated tokens are fed back as input for subsequent steps [13].

The GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) series represents the most celebrated examples of decoder-only models, demonstrating exceptional prowess in generative tasks [13]. In scientific domains, decoder-only architectures are increasingly employed for molecular generation and other creative design tasks [1].

Table 1: Core Architectural Differences Between Encoder-Only and Decoder-Only Models

| Feature | Encoder-Only Models | Decoder-Only Models |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Understanding and encoding input sequences [13] | Autoregressive generation of output sequences [13] |

| Attention Mechanism | Bidirectional self-attention (all tokens attend to all tokens) [13] | Masked self-attention (tokens attend only to previous tokens) [12] [13] |

| Typical Architecture | Stack of encoder layers with self-attention and feedforward networks [1] | Stack of decoder layers with masked self-attention and feedforward networks [1] |

| Key Strength | Rich contextual understanding of input data [13] | Coherent sequential generation [13] |

| Common Examples | BERT and its variants [1] [13] | GPT series, LLaMA [12] |

Diagram 1: Encoder-only vs. decoder-only architecture workflow comparison. Encoder-only models process entire input sequences to create contextual representations, while decoder-only models generate outputs sequentially using masked attention.

Application in Materials Discovery

Task-Specific Model Selection

The choice between encoder-only and decoder-only architectures in materials discovery depends heavily on the specific research task and data characteristics. Each architecture brings distinct capabilities that align with different stages of the materials research pipeline.

Encoder-only models demonstrate exceptional performance in analytical tasks that require comprehensive understanding of input data [1]. These include property prediction from molecular structure, spectral interpretation, and materials classification [1]. Their bidirectional attention mechanism enables them to capture complex relationships within material structures, which is crucial for predicting properties that emerge from intricate atomic interactions [1]. For inorganic solids and crystals, encoder-only models often leverage graph-based representations or primitive cell features to incorporate 3D structural information [1].

Decoder-only models excel in generative and design-oriented tasks [1]. Their autoregressive nature makes them ideal for molecular generation, where they can propose novel structures with desired properties token by token [1] [13]. In synthesis planning, decoder-only models can generate step-by-step reaction pathways or experimental procedures [1]. Recent advances have also demonstrated their utility in generating crystalline materials with specific symmetry constraints, though this presents unique challenges due to the periodic nature and strict symmetry requirements of crystals [14].

Table 2: Application of Encoder-Only and Decoder-Only Models in Materials Discovery

| Task Category | Encoder-Only Applications | Decoder-Only Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Property Prediction | Predicting material properties from structure [1], Spectral analysis [15] | Limited use for direct property prediction |

| Materials Generation | Limited generative capability | De novo molecular design [1], Crystal structure generation [14] |

| Synthesis Planning | Reaction condition prediction [1] | Step-by-step synthesis generation [1] |

| Data Extraction | Named entity recognition from literature [1], Molecular structure identification from images [1] | Limited extraction capabilities |

| Multi-scale Modeling | Property prediction across scales [15] | Limited application |

Performance and Efficiency Considerations

When deploying encoder-only and decoder-only models for materials discovery, researchers must consider several performance and efficiency factors. Encoder-only models typically demonstrate higher computational efficiency for tasks that don't require generation, as they process the entire input sequence in parallel during inference [12]. However, their bidirectional attention mechanism requires full visibility of the input sequence, which can limit their applicability to streaming data or real-time generation scenarios.

Decoder-only models face unique efficiency challenges due to their autoregressive nature [12]. As they generate output one token at a time, with each step depending on the previous outputs, inference can become computationally intensive for long sequences. However, recent optimizations have improved their practicality for research applications. Knowledge distillation techniques have been successfully applied to compress large, complex neural networks into smaller, faster models that maintain performance while reducing computational requirements [14].

The emerging paradigm of generalist materials intelligence represents a significant shift in how AI systems are applied to materials research [14]. These systems, powered by large language models (typically decoder-only), can interact with both computational and experimental data to reason, plan, and interact with scientific text, figures, and equations, functioning as autonomous research agents [14].

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Encoder-Only Protocol for Property Prediction

Objective: Predict material properties (e.g., conductivity, stability) from molecular structure using an encoder-only architecture.

Materials and Data Representation:

- Input Representation: Molecular structures encoded as SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings or SELFIES (SELF-referencing Embedded Strings) representations [1] [16]. For crystalline materials, use graph-based representations or primitive cell features to capture 3D periodicity [1].

- Training Data: Large-scale datasets such as ZINC (∼109 molecules) or ChEMBL for organic molecules; Materials Project database for inorganic crystals [1].

- Preprocessing: Tokenize input sequences using appropriate tokenizers (e.g., byte-pair encoding for SMILES). Apply data augmentation through SMILES enumeration or rotational/translational invariance for 3D structures.

Methodology:

- Model Architecture: Implement a BERT-like encoder-only model with multiple transformer encoder layers [1]. Each layer should include multi-head self-attention with bidirectional context and position-wise feedforward networks.

- Pre-training Phase: Train the model using masked language modeling objective on unlabeled molecular data [1]. Randomly mask 15% of input tokens and train the model to predict them based on surrounding context.

- Fine-tuning Phase: Adapt the pre-trained model to specific property prediction tasks using labeled datasets [1]. Add task-specific output layers (e.g., regression heads for continuous properties, classification heads for categorical properties).

- Alignment (Optional): Refine model outputs to align with scientific principles through reinforcement learning or constraint incorporation [1].

Validation: Evaluate model performance using hold-out test sets with relevant metrics (MAE, RMSE for regression; accuracy, F1-score for classification). Compare predictions against experimental data or high-fidelity computational results (e.g., DFT calculations) [16].

Decoder-Only Protocol for Molecular Generation

Objective: Generate novel molecular structures with target properties using a decoder-only architecture.

Materials and Data Representation:

- Input Representation: Use SMILES or SELFIES strings for molecular representation [16]. For conditional generation, prepend property descriptors or target conditions to the input sequence.

- Training Data: Curated datasets of known molecules with associated properties (e.g., PubChem, ZINC, ChEMBL) [1].

- Constraint Handling: Implement tools like SCIGEN (Structural Constraint Integration in GENerative model) to enforce geometric constraints during generation for specific material classes [17].

Methodology:

- Model Architecture: Implement a GPT-like decoder-only model with masked self-attention layers [1] [13]. Each layer should allow tokens to attend only to previous positions in the sequence.

- Pre-training Phase: Train the model using causal language modeling objective on large corpora of molecular representations [1]. The model learns to predict the next token in sequences of molecular structures.

- Conditional Fine-tuning: Fine-tune the pre-trained model for property-specific generation using reinforcement learning or guided generation techniques [1]. Incorporate physics-based constraints or synthetic accessibility filters during training.

- Generation Process: Use autoregressive decoding (e.g., beam search, nucleus sampling) to generate novel molecular structures token by token [13]. Start with a prompt indicating desired properties or structural constraints.

Validation: Assess generated structures for validity (chemical validity, stability), novelty (distinct from training data), and property optimization (achievement of target properties) [17]. Experimental validation through synthesis and characterization is ideal for promising candidates [17].

Diagram 2: Encoder-only model workflow for material property prediction. Molecular structures are converted to text representations, processed through bidirectional encoder layers, and used to predict target properties.

Case Study: Constrained Materials Generation with SCIGEN

A recent breakthrough in decoder-only models for materials discovery demonstrated the generation of quantum materials with specific geometric constraints [17]. Researchers developed SCIGEN (Structural Constraint Integration in GENerative model), a computer code that ensures diffusion models adhere to user-defined constraints at each iterative generation step [17].

Experimental Protocol:

- Model Setup: Applied SCIGEN to a popular AI materials generation model (DiffCSP) to generate materials with Archimedean lattices associated with quantum properties [17].

- Constraint Definition: Defined geometric constraints corresponding to Kagome and Lieb lattices known to host exotic quantum phenomena [17].

- Generation: Generated over 10 million material candidates with Archimedean lattices, with SCIGEN blocking generations that didn't align with structural rules [17].

- Screening: Applied stability screening to identify 1 million potentially stable structures from the generated candidates [17].

- Simulation: Performed detailed simulations on 26,000 materials to understand atomic behavior, identifying magnetic properties in 41% of structures [17].

- Synthesis and Validation: Synthesized two previously undiscovered compounds (TiPdBi and TiPbSb) with properties aligning with model predictions [17].

This case study illustrates how decoder-only models, when enhanced with domain-specific constraints, can accelerate the discovery of materials with exotic properties that might be overlooked by traditional design approaches [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Materials Foundation Models

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SMILES/SELFIES | Chemical Representation | Text-based representation of molecular structures for model input [1] [16] |

| SMIRK | Processing Tool | Improves how models process molecular structures, enabling learning from billions of molecules with greater precision [16] |

| SCIGEN | Constraint Tool | Ensures generative models adhere to user-defined geometric constraints during materials generation [17] |

| Open MatSci ML Toolkit | Software Framework | Standardizes graph-based materials learning workflows [15] |

| FORGE | Infrastructure Platform | Provides scalable pretraining utilities across scientific domains [15] |

| ALCF Supercomputers | Computing Infrastructure | Provides massive GPU resources needed for training foundation models on billions of molecules [16] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of foundation models for materials discovery is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends shaping future research directions. Hybrid architectures that combine encoder and decoder components show promise for tasks requiring both deep understanding and generation capabilities [1]. Similarly, multimodal foundation models that can process diverse data types (text, structure, spectra, images) are becoming increasingly important for comprehensive materials research [1] [15].

The integration of physical principles directly into model architectures represents a significant advancement. Physics-informed generative AI models embed crystallographic symmetry, periodicity, and other fundamental constraints directly into the learning process, ensuring generated materials are scientifically meaningful [14]. This approach moves beyond trial-and-error generation toward guided discovery aligned with materials science fundamentals.

Another promising direction is the development of generalist materials intelligence systems that function as autonomous research agents [14]. These systems, powered by large language models, can reason across chemical and structural domains, generate realistic materials, and model molecular behaviors with efficiency and precision [14].

As foundation models continue to evolve, addressing challenges in interpretability, data quality, and energy efficiency will be crucial for their widespread adoption in materials research [2]. The integration of uncertainty quantification and improved alignment with scientific principles will further enhance their utility as tools for accelerating materials discovery.

Encoder-only and decoder-only architectures offer complementary strengths for materials discovery applications. Encoder-only models provide powerful capabilities for property prediction and materials analysis through their bidirectional understanding of input data, while decoder-only models excel at generative tasks such as molecular design and synthesis planning through their autoregressive generation capabilities.

The optimal architectural choice depends on specific research objectives, data characteristics, and computational constraints. Emerging approaches that combine both architectures or integrate physical principles directly into models show significant promise for addressing the complex challenges of materials discovery. As foundation models continue to evolve, they are poised to transform materials research from a trial-and-error process to a data-driven, predictive science capable of accelerating the development of novel materials with tailored properties.

In the burgeoning field of materials discovery, the adage "data is the new oil" holds profound significance. The development and application of foundation models—AI systems trained on broad data that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks—are critically dependent on the volume, quality, and structure of the data on which they are built [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the imperative to efficiently source and extract information from both structured chemical databases and unstructured scientific literature is a fundamental prerequisite for progress. This technical guide examines the current state of data sourcing and extraction methodologies, framed within the context of advancing foundation models for materials discovery.

The challenge is substantial. Materials exhibit intricate dependencies where minute details can significantly influence their properties—a phenomenon known in the cheminformatics community as an "activity cliff" [1]. Models trained on insufficient or noisy data may miss these critical effects entirely, potentially leading research into non-productive avenues. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of available data sources, extraction protocols, and computational tools designed to transform disparate information into structured, AI-ready datasets.

Chemical and Materials Databases

Structured chemical databases provide a foundational resource for training foundation models. These repositories offer curated information on compounds, structures, and properties, though they vary significantly in scope, accessibility, and content focus.

Table 1: Major Chemical Databases for Materials Discovery

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Data Content | Access Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem [1] | Small molecules & bioactivities | Extensive repository of chemical structures, properties, and biological activities | Publicly accessible |

| ZINC [1] | Commercially available compounds | ~10^9 molecules for virtual screening | Publicly accessible |

| ChEMBL [1] | Bioactive drug-like molecules | Manually curated data on drug candidates and their properties | Publicly accessible |

| ICSD (Inorganic Crystal Structure Database) [3] | Inorganic crystal structures | Experimentally determined crystal structures | Licensed access required |

While these resources are invaluable, they present limitations including licensing restrictions (especially for proprietary databases), relatively small dataset sizes for niche applications, and biased data sourcing [1]. Furthermore, the most valuable insights often reside not in these structured repositories alone, but in the vast corpus of unstructured scientific literature.

Scientific Literature as a Data Source

A significant volume of materials knowledge exists within scientific publications, patents, and reports [1] [18]. This information is inherently multimodal, containing crucial data in text, tables, images, and molecular structures. For example, patent documents often represent key molecules in images, while the surrounding text may describe irrelevant structures [1]. This multimodality presents both a challenge and an opportunity for comprehensive data extraction.

The scale of published science is immense, with an estimated three million new papers published annually in Science, Technology, and Medicine alone [19]. This "embarrassment of riches" has made comprehensive manual curation impossible, creating a pressing need for automated, intelligent extraction systems.

Data Extraction Methodologies and Protocols

Foundational Extraction Techniques

Modern data extraction approaches typically focus on two interrelated problems: identifying materials themselves and associating described properties with these materials [1].

Named Entity Recognition (NER) represents a foundational approach for extracting material names and properties from text. Traditional NER systems have relied on pattern matching and dictionary-based approaches, but modern implementations increasingly leverage the capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) [1] [18].

For molecular structures embedded as images in documents, advanced computer vision algorithms are required. State-of-the-art approaches utilize Vision Transformers and Graph Neural Networks to identify and characterize molecular structures from graphical representations [1].

Schema-Based Extraction has been enhanced by recent advances in LLMs, enabling more accurate association of properties with specific materials according to predefined structured schemas [1]. This approach is particularly valuable for creating standardized datasets from heterogeneous document sources.

Integrated Extraction Pipelines: Protocol Examples

Protocol for the Librarian of Alexandria (LoA) Pipeline

The Librarian of Alexandria (LoA) is an open-source, extensible tool for automatic dataset generation via direct extraction from scientific literature using LLMs [20]. Its workflow consists of distinct, modular phases:

- Paper Collection and Preprocessing: The system automatically collects research papers from popular chemical journals that provide open access. These documents are converted to a consistent text format suitable for processing by LLMs.

- Relevance Checking: A designated LLM analyzes each research paper to determine its relevance to the target chemical domain or property of interest. This filtering step ensures computational resources are focused on pertinent literature.

- Data Extraction: A separate, specialized LLM (which can be independently specified by the user) performs the core extraction task. This model identifies and extracts specific chemical data points, such as compound names, properties, and experimental conditions, from the relevant papers.

- Output Generation: The extracted data is structured into a standardized format, creating an AI-ready dataset. The pipeline reports an accuracy of approximately 80% for these extraction tasks [20].

The modular design allows users to independently update the LLMs used for relevance checking and data extraction, facilitating the incorporation of newer, more powerful models as they become available.

Protocol for the LEADS Framework

The LEADS framework demonstrates a specialized approach for the medical and life sciences domain, focusing on systematic review tasks. Its methodology is built on a foundation of extensive, domain-specific training data [21]:

- Dataset Curation (LEADSInstruct): The model is instruction-tuned on a massive dataset of 633,759 samples curated from 21,335 systematic reviews, 453,625 clinical trial publications, and 27,015 clinical trial registries. This ensures the model learns domain-specific patterns and terminology.

- Task Decomposition: The literature mining process is decomposed into six specialized subtasks: search query generation, study eligibility assessment, and four distinct extraction subtasks (study characteristics, participant statistics, arm design, and trial results).

- Model Fine-Tuning: A pre-trained Mistral-7B model is fine-tuned on the LEADSInstruct dataset using instruction tuning. This process adapts the general-purpose LLM to the specific nuances of medical literature mining.

- Human-AI Collaboration: The system is designed to integrate into expert workflows, assisting with citation screening and data extraction rather than operating in a fully autonomous mode. In studies, this collaboration saved 20.8% of time in study selection and 26.9% in data extraction while improving accuracy [21].

Multimodal and Tool-Augmented Extraction

Advanced extraction pipelines are increasingly moving beyond pure text analysis. They employ multimodal strategies that combine LLMs with specialized algorithms to process diverse data forms [1].

For instance, Plot2Spectra is a specialized algorithm that extracts data points from spectroscopy plots in scientific literature, enabling large-scale analysis of material properties inaccessible to text-based models alone [1]. Similarly, DePlot converts visual representations like charts and plots into structured tabular data, which can then be interpreted by LLMs [1].

The ReactionSeek framework for organic synthesis data exemplifies this trend, synergistically combining LLMs with established cheminformatics tools to automate multi-modal mining of textual, graphical, and semantic chemical information [22]. This approach achieved over 95% precision and recall for key reaction parameters when validated on the Organic Syntheses collection.

Data Extraction Workflow: This diagram illustrates the generalized pipeline for extracting structured chemical data from multimodal scientific literature, incorporating relevance checking and parallel processing of text and images.

Building and applying effective data extraction systems requires a suite of computational tools and resources. The following table details key components of the modern data extraction toolkit.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Data Extraction

| Tool/Resource Name | Type/Function | Key Features & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Librarian of Alexandria (LoA) [20] | Extensible LLM Pipeline | Open-source tool for automatic dataset generation from scientific literature using modular, user-specifiable LLMs. |

| ReactionSeek [22] | Literature Mining Framework | Combines LLMs with cheminformatics tools to extract and standardize complex synthesis data from text and images. |

| Plot2Spectra [1] | Specialized Algorithm | Extracts data points from spectroscopy plots in scientific literature for large-scale property analysis. |

| DePlot [1] | Visualization Processing Tool | Converts plots and charts into structured tabular data that can be interpreted by LLMs. |

| SMILES/SELFIES [1] | Molecular Representation | Text-based representations of molecular structures that enable language models to understand and generate chemical entities. |

| SMIRK [16] | Molecular Processing Tool | Enhances how foundation models process SMILES structures, enabling learning from billions of molecules with greater precision. |

| ALCF Supercomputers (Polaris, Aurora) [16] | High-Performance Computing | Provides the massive computational power (thousands of GPUs) required to train large-scale foundation models on billions of molecules. |

Data Curation and Experimental Validation Protocols

Expert-Driven Data Curation

The ME-AI (Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence) framework demonstrates the critical role of human expertise in curating high-quality datasets for materials discovery [3]. Its protocol involves:

- Expert Curation: Materials experts compile a refined dataset using experimentally accessible primary features chosen based on intuition from literature, ab initio calculations, or chemical logic.

- Feature Selection: The experts select atomistic features (electron affinity, electronegativity, valence electron count) and structural features (crystallographic distances) that are chemically interpretable.

- Expert Labeling: For a dataset of 879 square-net compounds, experts label materials through visual comparison of available band structures to theoretical models, or use chemical logic for related compounds and alloys [3].

This approach "bottles" the insights latent in expert intuition, allowing machine learning models to articulate these insights through discoverable descriptors.

Validation and Benchmarking

Rigorous validation is essential for assessing the performance of extraction methodologies. The LEADS framework employs comprehensive benchmarking on thousands of systematic reviews [21]. Key validation metrics include:

- Recall: For search tasks, measuring the proportion of relevant studies successfully retrieved by the AI-generated search strategy.

- Accuracy: For data extraction tasks, comparing AI-extracted data against human-curated gold standards.

- Time Efficiency: Measuring the time savings achieved through human-AI collaboration compared to manual efforts.

In the LEADS user study, the Expert+AI collaborative approach achieved a recall of 0.81 (vs. 0.78 without AI) in study selection and 0.85 accuracy (vs. 0.80) in data extraction, while saving 20.8% and 26.9% of time respectively [21].

Data to Discovery Pipeline: This diagram outlines the logical relationship from diverse data sources through extraction, curation, and model training to final applications in materials discovery, highlighting the iterative nature of the process.

The imperative to effectively source and extract information from chemical databases and scientific literature represents a foundational challenge in the age of AI-driven materials discovery. As foundation models continue to evolve, their predictive power and generative capabilities will be directly proportional to the quality, breadth, and structure of their training data. Current methodologies, ranging from LLM-based extraction pipelines to expert-curated datasets and multimodal approaches, are rapidly maturing to meet this challenge.

The future trajectory points toward increasingly sophisticated human-AI collaboration, where researchers leverage these tools to navigate the vast chemical space more efficiently while embedding their domain expertise directly into the AI models. This synergistic relationship, combining human intuition with machine scalability, holds the promise of accelerating the discovery of novel materials for applications ranging from energy storage to pharmaceutical development. As these data extraction and curation protocols become more refined and accessible, they will fundamentally transform how scientific knowledge is aggregated, structured, and utilized for innovation.

The accelerating discovery of new materials and drug compounds is increasingly dependent on our ability to decode and utilize the vast scientific knowledge encoded in patents and research literature. Foundation models, trained on broad data and adaptable to diverse downstream tasks, represent a paradigm shift in materials informatics [1]. However, their potential is constrained by a critical bottleneck: the extraction of structured chemical information from the heterogeneous, multimodal formats prevalent in scientific documents [23] [24].

Crucial information about molecular structures, synthesis protocols, and material properties is distributed across text descriptions, data tables, and molecular images. Traditional data extraction approaches, which focus on a single modality, fail to capture the interconnected nature of this information [25]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to state-of-the-art multimodal data extraction pipelines, framing them within the broader context of building powerful foundation models for materials discovery. We detail the methodologies, benchmark the performance of current systems, and provide experimental protocols for implementing these techniques, providing researchers with the tools to construct high-quality, machine-actionable datasets from the complex tapestry of scientific documents.

The Multimodal Data Challenge in Science

In chemical and materials science patents and papers, information is not siloed but richly connected. A molecular image depicts a compound's structure, the accompanying text describes its properties and synthesis, and a table quantifies its performance [25]. Isolating these elements discards their semantic relationships. For instance, a Markush structure in a patent—a diagram representing a core scaffold with variable substituents—is often detailed textually in the "wherein" clauses of the document [23]. A foundation model trained only on images would miss the combinatorial chemical space defined by the text, and vice versa.

The scale of this challenge is immense. The PatCID dataset, for example, was created by processing documents from five major patent offices, ultimately indexing 80.7 million molecule images corresponding to 13.8 million unique chemical structures [24]. This volume necessitates robust, automated extraction pipelines. The ultimate goal of multimodal extraction is to move beyond retrieving documents to retrieving precise facts, relationships, and contexts, thereby creating a fertile, interconnected data landscape for training the next generation of scientific foundation models [1] [25].

Technical Architecture of a Multimodal Extraction Pipeline

A robust multimodal extraction system processes documents through parallel, specialized channels for text and images, followed by a critical fusion step that links entities across modalities. The workflow can be broken down into three core stages.

Document Segmentation and Image Classification

The first step is to identify and classify regions of interest within a document page. This is typically framed as an object detection problem.

- Methodology: A model like YOLOv8 (You Only Look Once) or DECIMER-Segmentation is trained to draw bounding boxes around all figures in a PDF [25] [24]. A subsequent image classifier, such as MolClassifier, then categorizes these detected images. Common classes include 'Molecular Structure,' 'Markush Structure,' 'Reaction Scheme,' 'Chart/Plot,' and 'Background' (for filtering out non-chemical images) [24].

- Experimental Protocol: To train and evaluate this stage, a dataset of patent pages must be manually annotated with bounding boxes and class labels. Performance is measured by standard computer vision metrics:

- Precision: The proportion of detected images that are correctly classified (e.g., true molecular structures / all images classified as molecular structures).

- Recall: The proportion of all true molecular images in the dataset that are successfully detected and correctly classified.

- State-of-the-art systems report precision and recall figures exceeding 80% on both random and uniformly distributed patent benchmarks [24].

Modality-Specific Parsing and Recognition

Once segmented, images and text are processed through specialized recognition modules.

Molecular Image Recognition via Optical Chemical Structure Recognition (OCSR) OCSR converts a graphical depiction of a molecule into a structured, machine-readable format like SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) or a molecular graph.

- Methodology: Modern OCSR tools like MolGrapher or ChemScraper use a multi-step process [25] [24]. They first parse the image into primitive graphical elements (lines, characters, shapes) using a combination of computer vision techniques—such as the Line Segment Detector (LSD) and watershed algorithms for raster images, or direct PDF command parsing for born-digital figures. These elements are then assembled into a visual graph, which is converted into a molecular graph using rules and neural networks. Implicit atoms (like carbon at bond intersections) are inferred, and the final graph is exported as a SMILES string.

- Performance: On a benchmark of randomly selected patent images, the MolGrapher module in the PatCID pipeline correctly recognized 63.0% of molecules, a significant challenge given the diversity of drawing styles and image quality [24].

Textual Information Extraction via Named Entity Recognition (NER) Textual passages are mined for chemical entities, properties, and reaction data.

- Methodology: This involves Named Entity Recognition (NER) systems trained to identify and classify chemical entities such as compound names, R-groups (e.g., R1, Ra), and substituent types (e.g., methyl, benzyl) [23]. Advanced pipelines like ReactionMiner use fine-tuned large language models (e.g., LLaMA) to not only identify entities but also extract structured reaction records, mapping reactants to products and associating conditions like temperature and yield [25]. Chemical names identified by NER are converted to SMILES using rule-based tools like OPSIN [25].

- Performance: On annotated patent snippets, modern systems can achieve high F1-scores, a measure of accuracy, in the range of 97-98% for recognizing chemical entities [23].

Cross-Modal Linking and Data Fusion

The final, and most critical, stage is to establish links between entities extracted from different modalities. For example, this step connects a molecule image labeled "34" in a figure to its textual description as "compound 34" in a paragraph [25].

- Methodology: A common approach is token-based text matching. The system uses regular expressions to find text mentions of diagram labels (e.g., "4b", "34") and then matches them with text labels extracted from within or near the molecular diagrams. A similarity metric like the normalized Levenshtein ratio is used to account for minor OCR or parsing errors [25]. This creates a unified index that allows a user to search for a molecule and find all associated patents, pages, and textual descriptions, and vice versa.

The following diagram illustrates the complete end-to-end workflow of a multimodal extraction pipeline.

Quantitative Performance of Extraction Tools

The effectiveness of data extraction pipelines is quantified through rigorous benchmarking against manually curated gold-standard datasets. The table below summarizes the performance and coverage of leading chemical patent databases, highlighting the trade-offs between manual curation and automated extraction.

Table 1: Performance and Coverage of Chemical Patent Databases [24]

| Database | Creation Method | Unique Molecules | Patent Documents | Key Metric: Molecule Recall | Notable Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PatCID | Automated Pipeline | 13.8 Million | ~1.06M Families (2010-2019) | 56.0% | High-quality automated extraction; broad document coverage. |

| Reaxys | Manual Curation | N/A | N/A | 53.5% | Considered the gold standard for data quality. |

| SciFinder | Manual Curation | N/A | N/A | 49.5% | High-quality manually curated data. |