Additive Manufacturing: A Foundational Guide for Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of additive manufacturing (AM), or 3D printing, and its transformative potential in pharmaceutical research and drug development.

Additive Manufacturing: A Foundational Guide for Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of additive manufacturing (AM), or 3D printing, and its transformative potential in pharmaceutical research and drug development. It covers foundational principles, from its core distinction as a layer-by-layer additive process versus traditional subtractive manufacturing. It delves into the specific AM methodologies most relevant to drug delivery, such as Binder Jetting (BJ-3DP) and material extrusion techniques, highlighting their application in creating personalized medicines, complex drug release profiles, and novel dosage forms. The article also addresses critical challenges including quality control, material limitations, and regulatory hurdles, while providing a comparative analysis of AM's value proposition against conventional methods. Finally, it explores future directions, including the integration of AI and the path toward decentralized, on-demand production of therapeutics.

What is Additive Manufacturing? Core Principles and the Pharmaceutical Revolution

Additive Manufacturing (AM), widely known as 3D printing, represents a transformative approach to industrial production that enables the creation of lighter, stronger parts and systems. As the industrial production name for 3D printing, AM is a computer-controlled process that builds three-dimensional objects from a digital file through a layer-by-layer deposition of material [1]. This fundamental paradigm distinguishes it from conventional manufacturing methods, which typically rely on subtractive processes or formative techniques. The layer-by-layer approach allows for unprecedented design freedom, minimal material waste, and the ability to create complex geometric structures that would be impossible or prohibitively expensive to produce using traditional methods.

The significance of AM within modern manufacturing research cannot be overstated. Since Chuck Hull invented stereolithography in 1983, the technology has evolved from rapid prototyping to full-scale industrial production across aerospace, medical, automotive, and consumer goods sectors [1]. Contemporary research focuses on expanding material options, improving process efficiency, enhancing part quality, and developing new applications that leverage the unique capabilities of additive approaches. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and research directions that define additive manufacturing as a disruptive force in production technologies.

The Fundamental Layer-by-Layer Process

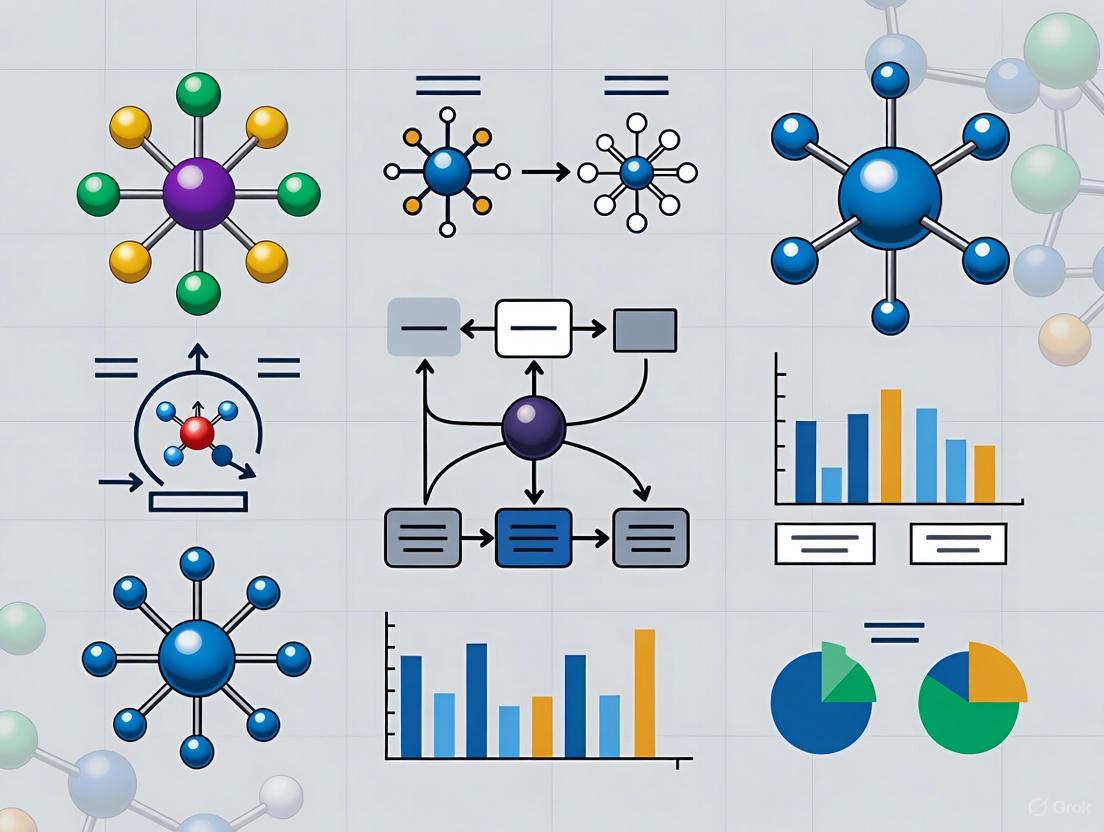

The additive manufacturing process follows a systematic workflow that translates digital designs into physical objects through sequential material deposition. The following diagram illustrates this fundamental process flow:

Fundamental AM Process Flow

Digital Design and Slicing

The AM process begins with creating a three-dimensional model using computer-aided design (CAD) software or 3D modeling programs. This digital file acts as a blueprint for the object to be manufactured [1]. The 3D model is then processed through slicing software, which digitally divides the model into thin horizontal layers, similar to slicing a loaf of bread [1]. Each layer represents a cross-section of the object at a specific height, and the slicing software generates the toolpath instructions that the AM equipment will follow to build each layer sequentially. This preparation stage is critical as it determines the resolution, structural integrity, and build time of the final part.

Material Selection and Deposition

Material selection depends on the desired properties and application of the final object, with common options including polymers, metals, ceramics, and even specialized materials like food substances [1]. The printing equipment follows instructions from the sliced model, meticulously depositing each layer of material on top of the previous one, gradually building the complete object [1]. Depending on the specific AM technology, the printing material may be in filament, powder, or liquid form. The layer-by-layer approach continues until the entire object is formed, with some technologies requiring temporary support structures for overhanging features that are removed during post-processing.

Post-Processing Requirements

Once printing is complete, most AM processes require some form of post-processing to achieve the desired finish and properties. This may include removal of support structures, sanding, polishing, heat treatment, or other surface treatments to achieve the required surface quality and mechanical properties [1]. Post-processing requirements vary significantly between different AM technologies and applications, with industrial applications often requiring more extensive post-processing to meet stringent quality standards for dimensional accuracy, surface finish, and material properties.

Key Additive Manufacturing Technologies and Methodologies

Established AM Processes

Multiple AM technologies have been developed, each with distinct mechanisms, materials, and applications. The table below summarizes the primary AM processes:

Table 1: Additive Manufacturing Processes and Characteristics

| Process | Materials | Key Advantages | Limitations | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) [1] | Thermoplastics (PLA, ABS, nylon) | Affordable, widely available, good for prototyping | Visible layer lines, limited material selection, may require support structures | Prototyping, simple to moderately complex objects [1] |

| Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) [1] | Metals (aluminum, titanium), plastics, ceramics | High accuracy, excellent for complex geometries, wide material range, strong parts | Expensive, limited build size, post-processing required | Functional metal parts, complex components [1] |

| Stereolithography (SLA) [1] | Photopolymer resins | High accuracy, smooth surface finish, detailed models | Expensive materials, limited selection, post-processing (washing/curing) | Detailed prototypes, models requiring high resolution [1] |

| Digital Light Processing (DLP) [1] | Photopolymer resins | Faster than SLA, larger objects | Similar limitations to SLA | Larger detailed objects, rapid production [1] |

| Electron Beam Melting (EBM) [1] | Metals (titanium, Inconel) | Strong, complex metal parts, high-quality finish | Extremely expensive, requires safety precautions | Aerospace components, medical implants [1] |

| Binder Jetting [1] | Sand, metal powders, food materials | Versatile material handling, relatively affordable | Lower strength/resolution, may require post-processing | Molds/cores for casting, specialty applications [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Process Optimization

Research in additive manufacturing extensively focuses on process parameter optimization to improve part quality, mechanical properties, and production efficiency. The following diagram illustrates a systematic experimental methodology for AM process optimization:

AM Process Optimization Methodology

A representative study on Selective Laser Melting (SLM) of AlSi10Mg alloy demonstrates rigorous experimental protocol design. Researchers employed an L9 orthogonal array from the Taguchi technique in their experimental development process [2]. The optimized parameters identified were 225 W laser power, 500 mm/s scanning speed, and 100 μm hatching distance, which yielded a high density value of 99.6% (2.66 g/cm³), defect-free components, and hardness of 126 ± 5 HV [2]. Samples were printed according to ASTM standards and analyzed using an Artec 3D scanner to ascertain geometric inaccuracies, with laser energy density calculated at 150 J/mm³ for the optimal process parameter [2].

Emerging research incorporates Artificial Intelligence (AI) for enhanced process optimization. Recent investigations utilize AI-based image segmentation in decision-making stages that employ quality-inspected training data from Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) methods [3]. AI-based Artificial Neural Network (ANN) models trained from NDT-assessed and AI-segmented data achieve 99.3% accuracy in automating the selection of optimized process parameters, significantly outperforming classical thresholding methods at 83.44% accuracy [3]. This methodology demonstrates a progressive shift toward intelligent, self-improving AM systems capable of predictive optimization without extensive iterative experimentation.

Materials in Additive Manufacturing

Material Categories and Properties

The material selection for AM processes has expanded significantly, enabling broader application across industries. The primary material categories include:

- Polymers: The most common materials used in FDM (Fused Deposition Modeling), available in various types offering durability, strength, and heat resistance. Resins are used in SLA (Stereolithography) and DLP (Digital Light Processing) for high-resolution and detailed prints [1].

- Metals: Metal powders employed in SLS (Selective Laser Sintering) and EBM (Electron Beam Melting) create strong, functional metallic parts. Common choices include titanium, aluminum, and stainless steel [1].

- Ceramics: Ceramic powders used in SLS for creating objects with high hardness, heat resistance, and wear resistance. Alumina (aluminum oxide) offers excellent thermal and chemical resistance, while zirconia provides high strength, biocompatibility, and wear resistance [1].

- Novel and Composite Materials: Emerging materials include sand for binder jetting applications creating molds and cores for metal casting, and various food materials for specialized applications [1]. Research continues to develop new material formulations and composite materials specifically tailored for AM processes [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Research Reagents in Additive Manufacturing

| Material/Reagent | Function | Compatible Processes | Research Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlSi10Mg Alloy [2] | Metal powder for high-strength components | Selective Laser Melting (SLM) | Optimized at 225W laser power, 500mm/s scan speed for 99.6% density [2] |

| Photopolymer Resins [1] | Liquid polymer that cures under light | SLA, DLP | Provide high resolution and smooth surface finish; require post-curing [1] |

| PLA (Polylactic Acid) [1] | Biodegradable thermoplastic filament | FDM | Common for prototyping; requires parameter optimization for mechanical properties [1] |

| Titanium Alloy Powders [1] | High-strength, lightweight metal components | SLS, EBM | Critical for aerospace and medical implants; processing requires precise parameter control [1] |

| Support Materials [1] | Temporary structures for overhangs | FDM, SLA | Water-soluble options preferred; removal process affects surface quality [1] |

Comparative Analysis: Additive vs. Conventional Manufacturing

Understanding the distinctions between additive and conventional manufacturing approaches illuminates the transformative potential of AM technologies. The fundamental differences include:

- Process Methodology: Additive manufacturing builds objects layer by layer, adding material until the desired shape is achieved, while conventional manufacturing typically removes material from a solid workpiece using techniques like machining, cutting, or carving [1].

- Design Complexity: AM excels at creating complex geometric shapes with intricate details, including internal features, due to the layer-by-layer approach. Conventional manufacturing faces limitations in creating highly complex geometries, especially with intricate internal features [1].

- Material Waste: AM generally produces less material waste as unused material is often recyclable or reusable, while conventional manufacturing can generate significant waste, particularly with intricate shapes or subtractive processes [1].

- Production Volume and Customization: AM suits low-volume production and enables greater customization through digital adjustments, while conventional manufacturing favors high-volume production through economies of scale and requires significant retooling for customization [1].

The comparative advantages explain AM's growing adoption across specialized applications while conventional methods maintain dominance in mass production of standardized components.

Research Applications and Future Directions

Current Research Applications

Additive manufacturing research spans diverse fields with several high-impact applications:

- Medical and Bio-printing: Medical AM includes customized implants, surgical guides, and bioprinting of tissues and organs, representing a rapidly advancing research frontier [4].

- Aerospace Components: The aerospace industry leverages AM for lightweight, complex geometries that reduce weight while maintaining strength, with specific focus on optimizing mechanical properties for flight conditions [2].

- Electromechanical Systems: Research explores 3D electronics, electromagnetics, and metamaterials through multi-material AM approaches that integrate functionality directly into components [4].

- Topology-Optimized Structures: AM enables manufacturing of complex shapes generated through computational optimization algorithms that maximize performance while minimizing material usage [4].

Emerging Research Frontiers

Future research directions focus on overcoming current limitations and expanding AM capabilities:

- Process Integration and Hybrid Systems: Development of multi-technology (hybrid) systems that combine AM with subtractive or other processes to leverage the advantages of each approach [4].

- Intelligent Process Control: Enhanced closed-loop control of AM systems using real-time monitoring and adaptive control strategies to improve consistency and quality [4].

- Advanced Material Development: New material formulations and composite materials specifically designed for AM processes, including functionally graded materials [4].

- AI-Driven Process Optimization: Implementation of artificial intelligence for predictive modeling, process parameter optimization, and quality assessment, as demonstrated by recent research achieving 99.3% accuracy in parameter prediction [3].

The continuous advancement of AM technologies promises to further expand applications while improving accessibility, reliability, and economic viability across industrial sectors.

Additive manufacturing represents a fundamental shift in production methodology, characterized by its layer-by-layer approach that enables unprecedented design freedom, material efficiency, and customization capabilities. As research addresses current challenges related to material selection, production speed, and quality consistency, AM continues to transform manufacturing paradigms across industries. The integration of artificial intelligence, advanced materials, and hybrid manufacturing approaches positions additive manufacturing as a cornerstone of future manufacturing ecosystems, particularly for applications requiring complexity, customization, and rapid iteration. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these core principles provides a foundation for leveraging AM technologies in specialized applications ranging from custom lab equipment to pharmaceutical development tools and medical devices.

Contrasting AM with Traditional Subtractive and Forming Manufacturing

Additive Manufacturing (AM), commonly known as 3D printing, represents a fundamental shift in production methodology, building objects layer-by-layer from digital models [5]. This approach stands in stark contrast to Traditional Subtractive Manufacturing (SM), which creates parts by removing material from a solid block, and Forming Manufacturing, which shapes materials through processes like bending or casting [6]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these manufacturing paradigms, examining their core principles, technical capabilities, and appropriate applications within industrial and research contexts. The evolution of AM from a prototyping tool to a viable production technology has catalyzed a reassessment of design and manufacturing strategies across aerospace, medical, automotive, and consumer goods industries [7]. This review, framed within broader additive manufacturing process research, delineates the distinct advantages, limitations, and implementation considerations for each methodology to inform researchers, scientists, and development professionals in selecting optimal manufacturing routes for their specific requirements.

Fundamental Manufacturing Paradigms

Additive Manufacturing (AM)

Additive Manufacturing constructs three-dimensional objects through sequential material deposition based on digital 3D model data [5]. This layer-wise approach enables unprecedented design freedom, allowing the creation of complex geometries, internal structures, and customized parts that are difficult or impossible to produce with traditional methods [8]. AM technologies have evolved to encompass a range of processes including material extrusion, vat photopolymerization, powder bed fusion, directed energy deposition, and binder jetting, each with distinct mechanisms, material compatibilities, and application suitability [5].

Subtractive Manufacturing (SM)

Subtractive Manufacturing encompasses technologies that remove material from a solid workpiece to achieve the desired geometry [9]. This category includes computer numerical control (CNC) machining, milling, turning, grinding, electrical discharge machining (EDM), and laser cutting [8]. SM processes are characterized by high dimensional accuracy, excellent surface finish, and proven reliability in industrial series production scenarios [8]. These methods are particularly valued for applications requiring tight tolerances, superior surface quality, and proven material properties [9].

Forming Manufacturing (FM)

Forming Manufacturing, also referred to as formative manufacturing, involves shaping materials through processes that deform rather than add or remove material [10]. This category includes metal injection molding, die casting, investment casting, and powder metallurgy, where material is shaped using molds, dies, or pressure [6]. These processes are typically characterized by high initial tooling costs but become economically advantageous at high production volumes, offering excellent reproducibility for complex parts at scale [6].

Technical Comparison and Quantitative Analysis

Process Characteristics and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Manufacturing Process Characteristics

| Parameter | Additive Manufacturing | Subtractive Manufacturing | Forming Manufacturing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Waste | Minimal (typically < 10%) [11] | Significant (can exceed 80% for complex parts) [9] | Low to moderate (includes sprues, runners) [6] |

| Production Speed | Slow for individual parts, faster for complex geometries [9] | Medium to fast for simple parts, slower for complex geometries [9] | Very fast once tooling is established (high volume) [6] |

| Design Freedom | Very high (complex geometries, lattices, internal channels) [8] | Limited by tool access and machining angles [9] | Limited by mold/die design and parting lines [6] |

| Surface Finish | Layering effects visible, often requires post-processing [9] | Excellent, high-quality finishes achievable directly [8] | Good, dependent on mold/die surface quality [6] |

| Tolerance Capability | Medium (±0.1-0.5mm typical) [9] | High (±0.025mm or better achievable) [9] | Medium to high (±0.1-0.3mm typical) [6] |

| Part Strength | Can be anisotropic (varies with build direction) [5] | Isotropic (consistent in all directions) [9] | Isotropic with proper process control [6] |

| Setup Complexity | Low (digital file preparation) | Medium to high (fixture design, toolpath generation) | Very high (custom mold/die creation required) |

| Economic Breakeven Volume | Low to medium volume (1-10,000 units) [6] | Low to high volume (1-100,000+ units) [9] | High volume (>10,000 units for economic viability) [6] |

Material Compatibility and Applications

Table 2: Material Compatibility and Industrial Applications

| Manufacturing Method | Compatible Materials | Typical Applications | Material Utilization Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additive Manufacturing | Photopolymers, thermoplastic filaments, metal powders (Ti, Al, Steel alloys), ceramic resins [5] | Prototypes, custom medical implants, aerospace components with complex geometries, jigs and fixtures [8] | High (typically 85-98%, only necessary material is used) [11] |

| Subtractive Manufacturing | Metals (aluminum, steel, titanium), plastics, wood, composites, glass [9] | Engine components, structural parts, molds, dies, high-tolerance mechanical components [8] | Low to medium (40-80% material removed and potentially wasted) [9] |

| Forming Manufacturing | Metals (aluminum, zinc, magnesium), plastics, powdered metals, composites [6] | High-volume consumer products, automotive components, electrical housings, fasteners [6] | Medium to high (60-95% depending on process and recycling) |

Sustainability and Environmental Impact

Table 3: Environmental Impact and Sustainability Metrics

| Environmental Factor | Additive Manufacturing | Subtractive Manufacturing | Forming Manufacturing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Waste | Can reduce waste by up to 90% compared to traditional methods [11] | High material removal generates significant waste (chips, shavings) [9] | Moderate waste (runners, sprues, flash) often recyclable |

| Energy Consumption | Varies by technology; can be high for metal AM (lasers, powder production) [7] | Moderate to high (power for material removal, coolant systems) | High for melting and maintaining material temperature |

| GHG Emissions | Potential to reduce emissions by up to 80% in construction applications [11] | Higher emissions due to increased material production needs | Process-dependent; high for energy-intensive operations |

| Supply Chain Impact | Enables localized production, reducing transportation emissions [7] | Typically centralized production with distributed parts | Economies of scale favor centralized mass production |

| Recyclability | Recycled materials gaining traction; challenges with support structures [12] | Metal chips often recyclable; cutting fluids require management | High recyclability of sprues and runners in some processes |

Experimental Methodologies and Research Protocols

Comparative Performance Analysis Protocol

Objective: Systematically evaluate mechanical properties, dimensional accuracy, and production efficiency of identical geometries produced via AM, SM, and FM processes.

Materials and Equipment:

- Test materials: AlSi10Mg aluminum alloy, 316L stainless steel, PA12 nylon

- AM systems: Laser Powder Bed Fusion (L-PBF) system, Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) printer

- SM systems: 3-axis CNC milling machine, CNC lathe

- FM systems: Injection molding machine, die casting equipment

- Characterization equipment: Coordinate measuring machine (CMM), universal testing machine, surface profilometer, scanning electron microscope

Methodology:

- Design Phase: Create standardized test specimens (tensile bars, compression samples, feature accuracy artifacts) with identical CAD models

- Process Optimization: Conduct preliminary trials to establish optimal parameters for each manufacturing method

- Production: Manufacture 20 replicates of each specimen type using each manufacturing technology

- Post-processing: Apply standard finishing procedures relevant to each manufacturing method

- Evaluation: Conduct dimensional metrology, mechanical testing, and microstructural analysis

Data Analysis:

- Compare dimensional deviation from CAD model using CMM data

- Statistically analyze mechanical properties (tensile strength, modulus, elongation)

- Correlate process parameters with resulting material properties and defects

- Conduct life cycle assessment for energy consumption and environmental impact

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials and Their Functions

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Powders (Ti-6Al-4V, AlSi10Mg) | Feedstock for powder bed fusion and directed energy deposition processes [5] | Aerospace, medical implant manufacturing |

| Photopolymer Resins | UV-curable polymers for vat photopolymerization (SLA, DLP) [5] | High-resolution prototypes, dental applications, microfluidics |

| CNC Cutting Tools | Material removal from solid workpieces (end mills, drills, inserts) | High-precision components, mold making, low-volume production |

| Metal Injection Molding Feedstock | Powder-binder mixture for forming small, complex metal parts [6] | High-volume production of small, complex geometries |

| Support Materials | Temporary structures to enable overhangs and complex geometries in AM | All AM processes requiring support during build |

| Die Lubricants | Facilitate part release and improve surface finish in forming processes | Die casting, injection molding |

| Cutting Fluids | Cool and lubricate machining interface, extend tool life | All subtractive machining operations |

Manufacturing Process Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental workflows for additive, subtractive, and forming manufacturing processes, highlighting their distinct approaches to part creation.

Diagram 1: Additive Manufacturing Workflow. The process begins with digital model creation, proceeds through layer preparation, sequential material deposition, and typically requires post-processing to achieve final part properties.

Diagram 2: Subtractive Manufacturing Workflow. This iterative process involves material removal from a solid workpiece, with in-process inspection guiding parameter adjustments to achieve final dimensions and tolerances.

Diagram 3: Forming Manufacturing Workflow. Characterized by significant upfront tooling investment, forming processes excel at high-volume production with minimal per-unit variation once established.

Applications and Industry Implementation

Industry-Specific Applications

- Aerospace: AM enables lightweight, complex components with consolidated assemblies; SM provides high-precision structural elements; FM produces standard high-volume components [7]

- Medical: AM facilitates patient-specific implants and surgical guides; SM creates precise surgical instruments; FM produces standard medical devices and components [5]

- Automotive: AM used for prototyping, custom tooling, and low-volume specialty parts; SM employed for engine and transmission components; FM dominates high-volume body panels and interior components [6]

- Construction: Emerging AM applications include building components with reduced material usage and complex geometries; SM used for precision structural elements; FM produces standard construction materials [11]

Hybrid Manufacturing Approaches

Increasingly, manufacturers are adopting hybrid approaches that combine multiple manufacturing methods to leverage their respective strengths [8]. Common hybrid strategies include:

- AM + SM: Using AM to create near-net-shape parts followed by SM for critical features requiring tight tolerances and superior surface finish [8]

- AM + FM: Employing AM to create conformal cooling channels in injection molds followed by traditional finishing processes [13]

- SM + FM: Using SM to create precision molds and dies for high-volume forming processes [6]

Future Trends and Research Directions

The manufacturing landscape continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping the future integration of AM, SM, and FM technologies:

- AI and Machine Learning Integration: Implementation of AI for process optimization, defect prediction, and parameter optimization across all manufacturing methods [5]

- Sustainability Advancements: Development of recycled materials, energy-efficient processes, and circular economy approaches [12]

- Digital Twins and Advanced Simulation: Creation of virtual manufacturing environments to predict outcomes and optimize processes before physical production [7]

- Multi-Material and Functionally Graded Materials: Advancements in processing multiple materials within single components to achieve localized properties [12]

- Standardization and Certification: Establishment of industry standards and certification protocols to enable broader adoption in regulated industries [7]

- Automation and Industry 4.0 Integration: Increased connectivity and automation across manufacturing systems for improved efficiency and quality control [12]

Additive, subtractive, and forming manufacturing technologies each offer distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different applications, production volumes, and performance requirements. AM provides unparalleled design freedom and customization with minimal material waste, particularly valuable for complex geometries, low-volume production, and customized components. SM delivers exceptional precision, surface quality, and material properties for components with tight tolerances. FM offers economic advantages at high production volumes with excellent reproducibility. Rather than existing in competition, these manufacturing paradigms increasingly complement each other in hybrid approaches that leverage their respective strengths. The optimal manufacturing strategy often involves thoughtful integration of multiple technologies throughout the product development and production lifecycle. Future advancements in materials, process monitoring, automation, and sustainability will further blur the boundaries between these methodologies, enabling more efficient, customized, and environmentally responsible manufacturing across industries.

The digital thread is a transformative communication framework that creates a seamless flow of data connecting every stage of a product's lifecycle. In the context of pharmaceutical additive manufacturing (AM), it provides a digital record that integrates and links all data generated from initial computer-aided design (CAD) models through to the final finished drug product. [14] [15] This represents a paradigm shift from traditional document-centric approaches to a data-centric methodology where information flows continuously across traditionally siloed systems, enabling unprecedented levels of traceability, quality control, and process optimization. For researchers and drug development professionals, implementing a robust digital thread strategy is critical for accelerating drug development, improving quality assurance, and responding more effectively to stringent regulatory requirements. [14]

The digital thread differs fundamentally from a digital twin, though the concepts are complementary. While the digital thread serves as the connective framework ensuring data continuity, a digital twin is a virtual representation of a physical product, system, or process that uses this data to simulate, analyze, and predict performance. [14] In pharmaceutical AM, digital twins rely on digital thread solutions to enhance accuracy and provide deeper operational insights into drug product behavior throughout its lifecycle.

Core Components of the Pharmaceutical Digital Thread

Fundamental Data Types

The digital thread in pharmaceutical AM is built upon structured data that provides a comprehensive view of the entire manufacturing process. The table below summarizes the critical data types required for an effective implementation. [15]

Table: Essential Data Types for Pharmaceutical Additive Manufacturing Digital Thread

| Data Category | Specific Elements | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Design Data | 3D models, CAD files, design specifications | Defines internal structure, surface area, and drug release characteristics of printed dosage forms |

| Material Data | Powder composition, particle size distribution, rheological properties, excipient compatibility | Critical for ensuring consistent print quality, drug stability, and dissolution performance |

| Build Parameters | Nozzle temperature, layer thickness, print speed, laser power (for sintering) | Directly impacts final product properties including porosity, strength, and drug release profile |

| Process Data | Real-time sensor data, environmental conditions, post-processing parameters | Enables root cause analysis of deviations and supports continuous process verification |

| Quality Data | In-line monitoring results, non-destructive testing (NDT) data, quality metrics | Ensures part integrity, compliance with regulatory standards, and final product quality |

Enabling Technologies and Infrastructure

A robust digital thread requires specialized technologies to maintain data integrity and accessibility across the pharmaceutical product lifecycle: [15]

- Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) Systems: Software platforms like Siemens Teamcenter centralize AM data, making it accessible to stakeholders across research, development, and manufacturing while maintaining version control and audit trails essential for regulatory compliance.

- Cloud Platforms: Provide flexible, scalable, and secure data access for geographically distributed research and manufacturing teams, facilitating collaboration while maintaining data integrity.

- Interoperability Standards: Open standards such as STEP AP242 and specialized APIs ensure seamless communication between different machines, software, and systems within the AM ecosystem, preventing data silos that can compromise product quality.

- Traceability Systems: Unique identifiers for each material batch and intermediate product enable full traceability throughout the pharmaceutical AM workflow, a critical requirement for regulated industries.

- Security Measures: Encryption, secure access controls, and potentially blockchain technologies protect sensitive intellectual property and patient data from unauthorized access throughout the digital thread.

Implementation Framework: Connecting CAD to Finished Product

Stage 1: Digital Design and Formulation

The digital thread begins with the creation of a 3D CAD model that defines the precise geometry of the drug delivery system. For pharmaceutical AM, this extends beyond traditional mechanical design to incorporate biopharmaceutical considerations:

- Model Creation: Utilizing specialized CAD software to design complex internal structures that control drug release kinetics, including gradient porosity, internal channels, and multi-reservoir systems.

- Material Selection: Digital formulation libraries containing excipient properties, compatibility data, and processing parameters to inform material selection based on the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) characteristics.

- Virtual Simulation: Using predictive modeling to simulate drug release profiles, structural integrity under stress conditions, and potential interactions between API and excipients during the printing process.

Stage 2: AM Process Execution and Monitoring

During the additive manufacturing process itself, the digital thread captures critical process parameters and quality metrics in real-time: [15]

- Build File Preparation: Conversion of CAD models into machine-specific instructions (e.g., G-code) while maintaining metadata linkages to original design specifications.

- In-process Monitoring: Integration of sensor data (thermal, optical, spectroscopic) to monitor critical quality attributes during printing, with automated flagging of deviations from established parameters.

- Environmental Conditions: Tracking of ambient temperature, humidity, and particulate levels that may impact product quality, particularly for hygroscopic or temperature-sensitive materials.

Stage 3: Post-Processing and Finishing

Post-processing operations are fully integrated within the digital thread to maintain data continuity:

- Cleaning Procedures: Documented removal of support structures and powder residues with parameters (methods, durations, inspection results) recorded in the digital thread.

- Surface Treatments: Tracking of any surface modification processes (polishing, coating) applied to the printed dosage forms and their impact on critical quality attributes.

- Curing Operations: For technologies requiring post-print curing, detailed records of time-temperature profiles and their relationship to final product performance.

Stage 4: Quality Verification and Release

The final stage integrates verification data to complete the digital product record:

- Non-Destructive Testing (NDT): Results from techniques such as micro-CT scanning that verify internal structure without destroying samples, with data linked back to specific build parameters.

- Dimensional Verification: Comparison of final product dimensions with original CAD specifications to identify potential print deviations.

- Chemical Analysis: Spectroscopic and chromatographic data confirming API content, distribution, and stability within the printed dosage form.

Digital Thread Pharmaceutical Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmaceutical AM

The implementation of digital thread methodologies in pharmaceutical additive manufacturing requires specialized materials and reagents with carefully documented properties. The table below details essential research reagents and their functions in AM drug product development. [16]

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Pharmaceutical Additive Manufacturing

| Reagent/Material | Function in Pharmaceutical AM | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Thermoplastic Polyurethanes (TPU) | Controlled release matrix for sustained drug delivery | Glass transition temperature, melt flow index, drug compatibility |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Sacrificial support material for complex geometries | Solubility rate, particle size distribution, residual solvent levels |

| Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC) | Bioerodible matrix for extended release formulations | Viscosity grade, gelling capacity, pH-dependent solubility |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Biodegradable filament for implantable dosage forms | Crystallinity, molecular weight distribution, degradation profile |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Plasticizer and pore-forming agent in printed dosage forms | Molecular weight, melting point, hygroscopicity |

| Eudragit Polymers | pH-dependent release matrices for targeted delivery | Functional group composition, film-forming properties, dissolution threshold |

Quantitative Analysis of Digital Thread Impact

The implementation of digital thread technologies in manufacturing environments has demonstrated significant quantitative benefits across multiple performance indicators. The table below summarizes documented improvements from industry implementations. [14]

Table: Documented Benefits of Digital Thread Implementation in Manufacturing

| Performance Metric | Improvement Percentage | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reduction in Unplanned Downtime | 50% | Overall manufacturing operations |

| Reduction in Maintenance Costs | 40% | Equipment and process maintenance |

| Improvement in Right-First-Time Quality | 90% | Production quality metrics |

| Reduction in Ramp-up Defects | 97% | New product introduction |

| Market Growth (CAGR 2024-2025) | 21.1% | Additive manufacturing sector |

| Projected Market Growth (2024-2029) | 21.2% CAGR | Additive manufacturing sector |

The additive manufacturing market, which serves as a key enabling technology for the digital thread in pharmaceuticals, has demonstrated substantial growth—increasing from $19.34 billion in 2024 to a projected $23.42 billion in 2025. [17] This growth is projected to continue, with the market expected to reach $50.49 billion by 2029, reflecting the increasing adoption of digital thread methodologies across pharmaceutical and other high-value industries. [17]

Experimental Protocol for Digital Thread Implementation

Protocol: Establishing a Digital Thread for Pharmaceutical AM Research

This experimental protocol provides a detailed methodology for implementing a basic digital thread framework in a pharmaceutical AM research setting, with specific focus on creating traceable connections between CAD models and final drug product characteristics. [16]

Sample, Instrument, Reagent, and Objective (SIRO) Model

- Sample: Immediate-release oral dosage form prototypes incorporating a model API (e.g., caffeine, metformin HCl)

- Instruments: Fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printer, CAD software, PLM system, HPLC system for analysis

- Reagents: Pharmaceutical-grade polymers (HPMC, PVA), model API, plasticizers (PEG)

- Objective: To establish and validate a digital thread framework that connects CAD design parameters to critical quality attributes of printed dosage forms

Step-by-Step Methodology

Digital Design Phase

- Create CAD models of dosage forms with systematically varied internal geometries (infill density: 20-80%, pattern type: grid, honeycomb, gyroid)

- Export design files in STL format with embedded metadata including designer identification, creation timestamp, and revision history

- Upload designs to PLM system with unique identifiers that will propagate through subsequent manufacturing stages

Material Preparation and Tracking

- Prepare filament using hot-melt extrusion with documented parameters (temperature profile, screw speed, torque)

- Assign unique material batch numbers linked to certificate of analysis in the digital thread

- Record environmental conditions (temperature, relative humidity) during material storage and handling

Additive Manufacturing Execution

- Program build files with embedded quality checkpoints at specified layer intervals

- Monitor and record real-time process parameters (nozzle temperature, build plate temperature, extrusion rate)

- Implement automated logging of any process deviations or interruptions with timestamps

Post-Processing Documentation

- Record support material removal methods and duration

- Document any surface treatments applied with corresponding parameters

- Capture images of finished dosage forms and link to digital product record

Quality Verification and Data Linking

- Perform dimensional analysis using digital calipers or micro-CT scanning

- Conduct dissolution testing according to USP standards with full methodology documentation

- Analyze API content using validated HPLC methods with results linked to specific build parameters

- Correlate all quality data with original CAD parameters through the digital thread identifiers

Data Integration and Analysis

- Consolidate all data streams within the PLM system using the unique identifiers established during the design phase

- Perform statistical analysis to identify correlations between CAD parameters, process conditions, and final product attributes

- Validate the digital thread by tracing any quality deviations back to specific process steps or design decisions

- Establish acceptance criteria for digital thread completeness and data integrity

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The continued evolution of digital thread technologies in pharmaceutical AM presents several promising research directions that will further enhance the connectivity between CAD models and finished drug products:

- AI-Enhanced Predictive Modeling: Integration of machine learning algorithms to predict drug release profiles and optimize CAD parameters based on historical performance data from the digital thread.

- Blockchain for Enhanced Security: Implementation of distributed ledger technologies to create immutable audit trails for regulatory submissions and intellectual property protection.

- Advanced Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Development of real-time spectroscopic methods for in-line quality verification with direct feedback to manufacturing parameters.

- Standardized Data Models: Creation of hierarchical object-oriented models (HOOM) as standard data structures for AM digital threads to promote consistency and interoperability across research institutions and manufacturing facilities. [15]

As the pharmaceutical industry continues to embrace additive manufacturing for personalized medicines and complex drug delivery systems, the digital thread will play an increasingly critical role in ensuring product quality, regulatory compliance, and manufacturing efficiency. By implementing the frameworks and methodologies outlined in this technical guide, researchers and drug development professionals can establish robust digital thread systems that seamlessly connect CAD models to finished drug products while generating the comprehensive data required for regulatory approval and continuous process improvement.

The pharmaceutical industry is undergoing a profound transformation driven by three powerful forces: the demand for personalized therapies, the increasing complexity of new drug modalities, and the relentless pressure to accelerate development speed. This whitepaper examines how these interconnected drivers are compelling the industry to adopt advanced technologies, with a special focus on the emerging role of additive manufacturing (AM) in enabling this shift. The convergence of AI, advanced manufacturing, and data-driven R&D is creating a new paradigm where treatments are not only developed faster but are also precisely tailored to individual patient needs and biological complexities. This analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed examination of the supporting data, underlying mechanisms, and experimental frameworks shaping the future of pharmaceutical innovation.

The Imperative for Personalization

Market Forces and Technological Enablers

The shift toward personalized medicine represents a fundamental redirection from the traditional blockbuster drug model to a more targeted, patient-centric approach. This transition is fueled by both market demand and technological capabilities.

Table 1.1: Personalized Medicine Market Drivers and Enablers

| Driver/Enabler | Impact Metric | Technology Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rising Consumer Demand | OTC market projected to reach $200 billion by 2025 [18] | Symptom tracking apps, medication adherence platforms |

| Precision Therapeutics | Oncology dominates as fastest-growing therapeutic area [18] | Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), mRNA-based therapies |

| Data-Driven Engagement | Email open/click rates improve by 40% with AI hyper-personalization [19] | Omnichannel next-best-action solutions, modular content |

| Regulatory Evolution | MLR approval cycles averaging 50 days for traditional content [19] | AI-powered MLR pre-screening, modular content libraries |

Advanced AI platforms now enable hyper-personalization by dynamically assembling content features based on individual healthcare professional preferences. This goes beyond basic messaging to customize elements such as message sentiment, visual aesthetics, and content format, resulting in dramatically improved engagement metrics [19].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing AI-Driven Hyper-Personalization

Objective: To significantly increase engagement with healthcare professionals (HCPs) through hyper-personalized marketing content.

Methodology:

- Content Modularization: Deconstruct composite marketing assets (e.g., full email templates) into reusable fragments (e.g., individual images, message paragraphs) [19].

- Comprehensive Tagging: Apply a detailed taxonomy to tag modules with attributes (key message, tone, aesthetics) using AI algorithms combined with human validation (70-80% accuracy achieved) [19].

- MLR Process Acceleration: Submit pre-approved modular components for streamlined regulatory review, leveraging AI to flag content with low approval probability [19].

- Dynamic Assembly & Testing: Use an omnichannel next-best-action platform to dynamically assemble modules based on individual HCP preferences and conduct A/B testing to refine personalization algorithms [19].

Expected Outcome: A measured sales lift of 15-30% and a 40% improvement in email open and click-through rates, as demonstrated in existing industry implementations [19].

Navigating Biological and Manufacturing Complexity

The Challenge of Advanced Therapeutics

The pharmaceutical landscape is increasingly characterized by complex biologics, biosimilars, and novel modalities that present significant manufacturing and supply chain challenges. These sophisticated therapies often require precise control over manufacturing parameters and specialized supply chain logistics.

Table 2.1: Complexity Drivers and Additive Manufacturing Applications in Pharma

| Complexity Driver | Impact on Traditional Manufacturing | Additive Manufacturing Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Complex Biologics & Biosimilars | Necessitates advanced quality control; increased production costs [20] | AI-driven analytics for quality control; personalized production runs |

| Supply Chain Vulnerabilities | Medicine shortages; logistics disruptions; human cost [21] | On-demand, localized production of parts or medications |

| Personalized Dosage Forms | Economically unviable with mass-production techniques [20] | 3D printing of patient-specific drug doses and delivery systems |

| Intricate Device Design | Limitations in creating complex geometries for drug delivery [17] | 3D printing of complex, customized medical devices and implants |

The growing prevalence of these complex therapies is a principal driver for adopting Industry 4.0 principles, collectively termed "Pharma 4.0." This framework integrates smart manufacturing, digitalized supply chains, and predictive analytics to enable real-time decision-making and greater agility in production processes [20].

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing a Pharmaceutical Powder Bed Fusion (PBF) Process

Objective: To establish a reliable and repeatable Additive Manufacturing process for producing a high-strength, patient-specific medical implant from a Ti-6Al-4V alloy.

Methodology:

- Material Characterization: Determine particle size distribution, flowability, and chemical composition of the Ti-6Al-4V powder.

- Machine Parameter Optimization: Utilize a machine learning approach (e.g., Pareto active learning framework) to explore hundreds of candidate parameter combinations (e.g., laser power, scan speed, hatch spacing, layer thickness) based on an initial training dataset [22].

- Build Process Monitoring: Implement in-situ monitoring systems (thermal cameras, melt pool sensors) for real-time defect detection (e.g., lack-of-fusion, keyholing, porosity) [23].

- Post-Processing & Validation: Subject finished parts to stress relief and hot isostatic pressing (HIP). Conduct mechanical testing (ultimate tensile strength, elongation) and microstructural analysis to validate performance against target metrics (e.g., UTS > 1150 MPa, elongation > 15%) [22].

Expected Outcome: Identification of an optimal parameter set that produces Ti-6Al-4V components with an ultimate tensile strength of 1,190 MPa and a total elongation of 16.5%, successfully balancing strength and ductility [22].

The Race for Speed in Drug Development

Accelerating from Discovery to Market

In an increasingly competitive landscape, speed-to-market has become a critical determinant of commercial success and patient impact. The industry faces pressure to compress development timelines while managing rising R&D costs.

Table 3.1: Quantitative Impact of AI and Advanced Technologies on Drug Development Timelines

| Technology Application | Reported Efficiency Gain | Global Market Context |

|---|---|---|

| AI in Drug Discovery | Reduces development timelines by up to 70% [18] | AI-driven discovery platform market expanding at a robust CAGR [24] |

| Pharma 4.0 Adoption | Global market projected to grow from $13.7B (2024) to $40.3B (2030) (CAGR 19.7%) [20] | Fueled by demand for personalized medicine, digital twins, AI & ML [20] |

| Streamlined Content Launch | Achieve "brief to deployment" in under 24 hours with AI-driven content systems [25] | Content output projected to increase five-fold over two years [25] |

| Additive Manufacturing | Market to grow from $23.42B (2025) to $50.49B (2029) (CAGR 21.2%) [17] | Driven by mass customization, healthcare bioprinting, and speed-to-market [17] |

Artificial intelligence is at the forefront of this acceleration. AI-driven drug discovery platforms leverage machine learning, deep learning, and generative models to significantly compress early-stage discovery timelines, potentially by 30-50%, through faster hypothesis generation, enhanced compound selection, and improved clinical candidate prediction [24].

Experimental Protocol: Deploying an End-to-End Digital Content Management System

Objective: To drastically reduce the time required to create, approve, and deploy compliant marketing and educational content.

Methodology:

- System Integration: Implement a consolidated technology stack (e.g., Adobe GenStudio) that spans the entire content lifecycle, integrated with workflow management (e.g., Workfront) [25].

- Claim Library & Templating: Create a centralized library of reusable, MLR-approved content blocks and product claims. Use templates that enforce fair balance requirements for compliant assembly [25].

- Automated MLR Review: Configure an AI agent to conduct initial, low-risk MLR checks. Use risk-based tiering to route medium and high-risk content to appropriate human reviewers, who provide strategic oversight and final sign-off [25].

- Integrated Regulatory Submission: Utilize the system's capability to automatically format and submit content to different regulatory bodies (e.g., FDA, MHLW) according to their specific requirements [25].

Expected Outcome: Transition from a manual process taking up to 50 days to a streamlined workflow enabling "brief to deployment" of market-ready content in less than 24 hours [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

Table 4: Essential Research Materials and Reagents for Pharmaceutical and AM Research

| Item | Function/Application | Relevance to Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Ti-6Al-4V Alloy Powder | Primary feedstock for laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) of high-strength, biocompatible implants [22] | Complexity: Enables production of patient-specific, complex geometric implants. |

| Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK) | High-performance thermoplastic for fused deposition modeling (FDM) of sterilizable medical devices and components [22] | Speed & Personalization: Allows rapid production of customized surgical guides and tools. |

| Biocompatible Resins | Photopolymer resins for stereolithography (SLA) used in creating anatomical models for surgical planning [23] | Personalization: Facilitates creation of patient-specific anatomical models. |

| Modular Content Tagging Algorithm | AI-based software for categorizing content fragments with attributes (message, tone, aesthetics) for dynamic assembly [19] | Speed: Automates and accelerates the generation of personalized HCP communications. |

| In-Silico Screening Platform | AI-driven software for virtual simulation of molecular interactions to identify promising drug candidates from large libraries [24] | Speed: Drastically reduces early-stage drug discovery timelines. |

Integrated Workflow and Strategic Implications

The interplay between personalization, complexity, and speed creates a self-reinforcing cycle of innovation. The demand for personalized treatments drives the development of more complex therapeutics, which in turn necessitates faster and more flexible R&D and manufacturing approaches. Additive manufacturing, digital twins, and AI-powered platforms are not isolated solutions but interconnected components of a new, agile pharmaceutical ecosystem.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow driven by these three core drivers, showcasing how data and technology create a continuous cycle of innovation from discovery to patient delivery.

Diagram 1: The Innovation Cycle Driven by Personalization, Complexity, and Speed. This workflow demonstrates how data from patient outcomes fuels a continuous cycle of innovation, enabled by integrated digital and manufacturing technologies.

The pharmaceutical industry's adoption of advanced technologies is no longer optional but imperative, driven by the powerful triad of personalization, complexity, and speed. Additive manufacturing emerges as a critical enabler within this triad, providing the flexibility needed for personalized therapies, the capability to manage complex designs and materials, and the agility to accelerate time-to-market. For researchers and drug development professionals, success in this new paradigm requires a multidisciplinary approach that embraces AI, digital workflows, and advanced manufacturing principles. The organizations that strategically integrate these capabilities will be best positioned to deliver innovative treatments that meet the evolving needs of patients and healthcare systems worldwide.

Additive Manufacturing (AM), commonly known as 3D printing, represents a fundamental shift in production methodology, moving from traditional subtractive or formative techniques to a layer-by-layer additive approach. For researchers and scientists, particularly those in structured fields like drug development, the reproducibility and standardization of manufacturing processes are paramount. The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) International plays a critical role in this ecosystem by providing a standardized framework for classifying AM processes. Established in 2012 by the ASTM F42 committee, this classification system groups the wide array of AM technologies into seven distinct families [26]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these seven families, detailing their operating principles, material considerations, and applications, with a specific focus on the needs of research professionals engaged in process development and validation.

The Seven Families of Additive Manufacturing

The ASTM classification system ensures clarity and consistency in communication and research across the global AM community. The seven categories are defined by the underlying method of layer creation and the material feedstock used [26] [27]. The following sections provide a detailed analysis of each family.

VAT Photopolymerization

Core Principle: Vat photopolymerization uses a vat of liquid photopolymer resin from which the model is constructed layer by layer. A light source—typically a laser or projector—selectively cures the resin, solidifying the cross-sections of the part [26].

Key Technologies: The primary technologies in this family include Stereolithography (SLA) and Digital Light Processing (DLP). SLA uses a laser to trace each layer, while DLP projects a single image of an entire layer at once, potentially reducing print time per layer.

Research Context and Experimental Considerations: For researchers, understanding the influence of process parameters on material properties is crucial. As demonstrated in an experimental characterization study for SLA materials, key parameters that significantly affect mechanical performance and anisotropy include printing orientation, layer height (e.g., 50 µm vs. 100 µm), and post-curing conditions (time, temperature, and UV intensity) [28]. A comprehensive experimental framework should include tensile and compression tests at different strain rates and build orientations to fully characterize the material's behavior [28].

Common Applications: Biocompatible resins make this process suitable for medical devices, microfluidics, and high-resolution prototyping. Its excellent surface finish is a key advantage.

Material Jetting

Core Principle: Material Jetting (MJ) operates in a manner similar to a two-dimensional inkjet printer. Material is jetted onto a build platform using a continuous or Drop on Demand (DOD) approach [26]. The liquid photopolymer droplets are immediately solidified by UV light [27].

Key Technologies: The common names for this process are simply Material Jetting (MJ) and Drop on Demand (DOD).

Research Context and Experimental Considerations: The ability to jet multiple materials simultaneously allows for the creation of multi-material parts and digital materials with graded properties. This is particularly relevant for drug development research involving complex, multi-component systems. Key process variables for experimental protocols include droplet size, jetting frequency, material viscosity, and the UV curing intensity between layers.

Common Applications: This technology is ideal for producing realistic prototypes, medical models, and parts with variable hardness or transparency.

Binder Jetting

Core Principle: The binder jetting process uses two materials: a powder-based build material and a liquid binder. A print head deposits the binder adhesive onto a thin layer of powder, selectively binding the particles together to form a layer. This process repeats until the part, known as a "green part," is complete [26].

Key Technologies: The process is universally referred to as Binder Jetting.

Research Context and Experimental Considerations: A major focus of research is on post-processing, which often includes curing and infiltration with another material (e.g., cyanacrylate, wax, or metal) to enhance mechanical properties and density. Experimental reports should document powder morphology, binder saturation levels, post-processing schedules, and the infiltrant type.

Common Applications: This family enables full-color prototypes, large-scale sand casting molds for metalworking, and the production of metal and ceramic parts.

Material Extrusion

Core Principle: In material extrusion, material is selectively dispensed through a nozzle or orifice. The material is typically drawn from a spool as a filament, heated in a nozzle, and then deposited as a semi-molten state onto the build platform [26] [27].

Key Technologies: The most prevalent technology is Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), which is a trademark of Stratasys. The equivalent term under ISO/ASTM standards is Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF).

Research Context and Experimental Considerations: Material extrusion is widely used in research due to its accessibility. However, parts exhibit inherent anisotropy, with mechanical strength being highly dependent on build orientation, raster angle, layer height, and the air gap between deposited roads [28]. Research into advanced composites, such as carbon-fiber-reinforced filaments, is driving its use in functional applications like unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), where strength-to-weight ratio is critical [13].

Common Applications: This includes prototyping, tooling, jigs and fixtures, and end-use parts with composite materials.

Powder Bed Fusion

Core Principle: Powder Bed Fusion (PBF) encompasses processes that use a thermal energy source (a laser or electron beam) to selectively fuse regions of a powder bed [26]. The process involves spreading a thin layer of powder, fusing the cross-section of the part, lowering the build platform, and repeating.

Key Technologies:

- Selective Laser Sintering (SLS): For polymers, using a laser to sinter powder.

- Selective Laser Melting (SLM) / Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS): For metals, fully melting the powder particles.

- Electron Beam Melting (EBM): For metals, using an electron beam in a high-vacuum environment [27].

Research Context and Experimental Considerations: PBF, particularly of metals, is a major focus of AM research. Key challenges involve managing thermal stress and preventing defects like porosity and lack-of-fusion. Research into process optimization includes in-situ monitoring and the development of new alloys, such as the exploration of Ti1Fe as a potential alternative to the industry-standard Ti6Al4V for laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) [13]. The AM-Bench program by NIST provides rigorous benchmark measurements for L-PBF of alloys like IN718 and IN625 to validate and guide predictive simulations [29].

Common Applications: PBF is used for functional metal components in aerospace (e.g., turbine blades), medical (implants), and automotive industries.

Sheet Lamination

Core Principle: Sheet lamination processes bond sheets of material together to form an object. The bonding methods can include ultrasonic welding, adhesive bonding, or brazing. Unneeded material is often removed after the build, either layer-by-layer or after the entire part is complete [26].

Key Technologies: This family includes Ultrasonic Additive Manufacturing (UAM) for metals and Laminated Object Manufacturing (LOM) for papers or plastics.

Research Context and Experimental Considerations: UAM is a low-temperature, solid-state process, making it suitable for embedding sensors and electronics into metal matrices. Research protocols often focus on bonding parameters (ultrasonic amplitude, force), material compatibility, and the post-processing machining strategy.

Common Applications: Applications include the creation of smart structures with embedded components, aesthetic prototypes, and low-cost modeling.

Directed Energy Deposition

Core Principle: Directed Energy Deposition (DED) is a more complex process where focused thermal energy (a laser or electron beam) is used to melt materials as they are being deposited. The material feedstock, typically in powder or wire form, is injected into the melt pool created on the substrate [26].

Key Technologies: DED is known by several terms, including Laser Engineered Net Shaping (LENS), Direct Metal Deposition (DMD), and 3D laser cladding.

Research Context and Experimental Considerations: DED is notable for its ability to repair existing components and add features to pre-formed parts. It is also capable of in-situ alloying. Recent research showcases its potential for sustainability, such as using recycled nickel-aluminum bronze (NAB) grinding chips from ship propellers as powder feedstock after processing via impact whirl milling [13]. Key research variables include deposition head path, powder flow rate, energy density, and the shielding gas environment.

Common Applications: DED is used for repairing and remanufacturing high-value components (e.g., turbine blades), building large-scale metal structures, and applying functional coatings.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of the Seven AM Families

| AM Family | Material Feedstock | Energy Source | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vat Photopolymerization | Liquid Photopolymer Resin | UV Laser / Light Projector | High Accuracy, Smooth Surface Finish | Limited Material Properties, Photopolymer Aging |

| Material Jetting | Liquid Photopolymer | Piezoelectric Jetting Head / UV Light | Multi-Material Capability, High Detail | Brittle Parts, Support Removal Can Be Difficult |

| Binder Jetting | Powder + Liquid Binder | None (Binder Activation) | Full Color, No Support Structures, Scalability | "Green" Parts Are Weak, Often Requires Post-Infiltration |

| Material Extrusion | Filament (Polymer, Composite) | Heated Nozzle | Low-Cost, Wide Material Variety, Multi-material | Layer Adhesion Issues, Anisotropy, Low Resolution |

| Powder Bed Fusion | Polymer or Metal Powder | Laser / Electron Beam | Functional Parts, Complex Geometries, Good Material Properties | High Equipment Cost, Powder Handling, Size Limitations |

| Sheet Lamination | Sheets of Material (Metal, Paper) | Ultrasonic Welding / Adhesive | Ability to Embed Components, Low-Temperature (UAM) | Limited Geometric Complexity, Post-Processing Often Required |

| Directed Energy Deposition | Powder or Wire | Laser / Electron Beam / Plasma Arc | Large Scale Parts, Repair & Hybrid Manufacturing, High Deposition Rates | Lower Resolution, Rough Surface Finish |

Experimental Characterization and Benchmarking in AM Research

For scientists, the transition from prototyping to functional part production requires a deep understanding of material behavior under different stress states and strain-rate regimes. A systematic experimental methodology is essential to characterize the performance of AM materials and validate manufacturing processes.

A Framework for Material Characterization

A proposed experimental framework for characterizing AM materials, as applied to SLA, involves testing the influence of key manufacturing parameters [28]:

- Printing Parameters: Systematically varying build orientation (θ = [0–90]°) and layer height (e.g., 50 µm vs. 100 µm) to quantify anisotropy and the effect of stair-stepping.

- Post-Processing: Studying the effects of curing time and temperature on the degree of polymerization and final mechanical properties.

- Mechanical Testing: Conducting tensile, compression, and load-unload cyclic tests at different strain rates to understand material behavior under various stress states and dynamic conditions.

This framework can be adapted to other AM families, with parameters specific to each process, such as laser power and scan speed for PBF, or nozzle temperature and print speed for material extrusion.

The Role of Benchmarking and Standards

Robust benchmarking is critical for advancing AM from an artisanal craft to a repeatable manufacturing process. Initiatives like the NIST-led AM-Bench provide a continuing series of highly controlled benchmark measurements and blind "challenge problems" that allow modelers to test their simulations against rigorous experimental data [29]. This is vital for closing the gap between prediction and reality in AM.

Furthermore, ASTM is continuously developing new standards to improve the efficiency of AM qualification. A key development is the work item WK81194, which aims to establish a specification for "Part Families-based Qualification" [30]. This approach allows for the qualification of groups of parts with similar geometric and load-bearing characteristics, moving away from the costly and time-consuming point-design qualification. This is highly relevant for research into scalable and economically viable AM production, such as for customized medical implants or drug delivery devices.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials in Additive Manufacturing

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in AM Research |

|---|---|

| AlSi10Mg Aluminum Alloy Powder | A common alloy for Laser Powder Bed Fusion (L-PBF) research; used in studies on process parameter optimization, thermal management, and mechanical property characterization [13]. |

| Ti6Al4V (Grade 5) & Ti1Fe Titanium Alloys | Benchmark and emerging titanium alloys for aerospace and biomedical AM; Ti1Fe is researched as a simpler, in-situ alloyable alternative to Ti6Al4V for L-PBF [13]. |

| IN718 & IN625 Nickel Superalloy Powders | High-performance materials used for rigorous benchmark measurements (e.g., AM-Bench) to study thermal processing, microstructure evolution, and mechanical performance under extreme conditions [29]. |

| Carbon-Fiber Reinforced Polymer Filaments | Composite materials (e.g., CFR-PLA, CFR-Nylon) used in Material Extrusion to enhance strength-to-weight ratio and structural durability for functional applications like drones [13]. |

| Photopolymer Resins (e.g., "Durable" Resin) | Standard material for VAT Polymerization research; used to establish experimental frameworks for analyzing the effect of printing orientation, layer height, and curing on mechanical properties [28]. |

| Polyamide 12 (PA12) Powder | The primary polymer for SLS process research; studied for its sintering behavior, recyclability, and mechanical properties in end-use parts. |

| Recycled Feedstock (e.g., NAB Chips) | Alternative material feedstock for Directed Energy Deposition (DED); researched for sustainable AM by recycling manufacturing waste into usable powder [13]. |

The ASTM classification of additive manufacturing into seven distinct families provides the foundational lexicon and technical framework necessary for rigorous scientific research and development. For researchers and scientists, understanding the principles, capabilities, and limitations of each family is the first step in selecting the appropriate technology for a given application, whether it be for creating bespoke laboratory equipment, developing novel drug delivery systems, or engineering load-bearing implants. The future of AM process research lies in the deep, quantitative characterization of materials and processes, the development of predictive models validated against rigorous benchmarks, and the creation of efficient qualification standards. These efforts, collectively, are crucial for unlocking the full potential of additive manufacturing as a reliable, industrial-grade production technology.

Pharmaceutical AM Technologies in Action: From Powder to Pill

Binder Jetting (BJ-3DP) is an additive manufacturing (AM) technology that builds three-dimensional objects through the selective deposition of a liquid binding agent onto thin layers of powdered material. Originally developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and patented in 1993, this technology adapts the fundamental principle of inkjet printing to three-dimensional fabrication [31] [32]. Unlike other AM processes that utilize thermal energy to fuse materials, binder jetting operates at or near room temperature, avoiding thermal stress and warping issues common in laser-based systems [32]. This characteristic makes it particularly suitable for processing temperature-sensitive materials, including many pharmaceutical compounds.

The versatility of binder jetting enables its application across diverse industries, including aerospace, biomedical, construction, and notably, pharmaceutical manufacturing [33] [31]. The technology's ability to produce complex geometries without support structures, combined with its relatively high build speeds and capacity for multi-material printing, positions it as a transformative approach in additive manufacturing research and industrial applications [32].

Fundamental Mechanism and Process Parameters

The Binder Jetting Process Workflow

The binder jetting process follows a systematic, layer-by-layer approach to transform digital designs into physical objects. The complete sequence can be visualized as follows:

The process initiates with the creation of a digital model using Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software, which is subsequently converted into a standard tessellation language (STL) file format [31]. This file is processed by slicing software that divides the model into two-dimensional cross-sectional layers and generates machine-readable instructions (G-code) for the printer [32]. The physical printing begins with the spreading of a thin layer of powder material across the build platform using a counter-rotating roller [31] [34]. A print head then moves across the powder bed, selectively depositing micro-droplets of liquid binder (typically 50-100 µm in diameter) onto specific regions corresponding to the cross-section of the part being built [31] [35].

Following binder deposition, the build platform descends by one layer thickness, and the process repeats until all layers are complete [32]. The printed part, known as a "green" part, remains embedded in the loose powder bed, which provides natural support during construction [32]. After printing, the part is carefully extracted from the powder bed, and loose powder is removed through depowdering—a process where unbound powder is collected for potential reuse, achieving material reuse rates of 95% or higher [32]. The final stage involves post-processing, which varies by material and application but typically includes curing to strengthen binder bonds and may involve sintering for metal parts or infiltration with secondary materials to enhance mechanical properties [32] [36].

Critical Process Parameters and Their Optimization

The quality and properties of binder-jetted components are influenced by numerous interdependent parameters that require careful optimization. Key parameters affecting printability and final part characteristics include:

Powder Characteristics: Powder properties significantly impact process success. Optimal powder materials exhibit good flowability to enable uniform spreading, appropriate particle size distribution (typically 10-100 µm) for sufficient resolution and packing density, and controlled wettability to facilitate proper binder penetration [34] [37]. Research has established that pharmaceutical powders suitable for binder jetting should achieve basic flow energy values between 150-250 mJ and specific energy values between 3.0-5.5 mJ/g as measured by powder rheometers [34].

Binder Formulation: The liquid binder must satisfy specific rheological properties for reliable jetting. Printability is characterized by the Ohnesorge number (Oh), a dimensionless parameter relating viscous forces to surface tension and inertia [31] [35]. Stable droplet formation typically occurs when 1 < Z < 10, where Z = 1/Oh [31]. Binder formulations may contain active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) dissolved or suspended in the liquid, necessitating careful control of viscosity and particle size to prevent nozzle clogging [35].