Accelerating Drug Discovery: A Guide to Gaussian Process Regression for Materials Synthesis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to materials synthesis.

Accelerating Drug Discovery: A Guide to Gaussian Process Regression for Materials Synthesis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to materials synthesis. We explore the foundational principles of GPR as a Bayesian machine learning framework for uncertainty quantification and design of experiments. The methodological section details practical implementation, including feature engineering, kernel selection, and active learning loops for autonomous experimentation. We address common challenges in troubleshooting GPR models and optimizing their performance for complex material systems. Finally, we validate GPR's efficacy by comparing it to traditional high-throughput experimentation and other machine learning models, demonstrating its power to drastically reduce the experimental burden and accelerate the discovery of novel pharmaceuticals, biomaterials, and drug delivery systems.

From Bayes to Biomaterials: The Foundational Principles of Gaussian Process Regression

Core Theoretical Framework for Materials Synthesis

Gaussian Processes (GPs) provide a non-parametric Bayesian framework for regression and classification, ideal for modeling complex, data-scarce phenomena common in materials science and drug development. A GP is fully defined by a mean function ( m(\mathbf{x}) ) and a covariance kernel function ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') ), which encodes prior assumptions about the function's smoothness and periodicity.

In the context of a thesis on materials synthesis, GPs enable the prediction of material properties (e.g., bandgap, yield, stability) from synthesis parameters (e.g., temperature, precursor concentration, time) while rigorously quantifying prediction uncertainty. This guides efficient experimental design, such as via Bayesian optimization, to navigate complex parameter spaces with fewer experiments.

Quantitative Comparison of Common Covariance Kernels

The choice of kernel critically influences GP model performance. Below is a summary of kernels relevant to materials synthesis modeling.

Table 1: Common GP Covariance Kernels and Their Application in Materials Science

| Kernel Name | Mathematical Form | Hyperparameters | Key Properties | Best For Materials Synthesis Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Basis Function (RBF) | ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') = \sigma_f^2 \exp\left(-\frac{|\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}'|^2}{2l^2}\right) ) | ( l ) (length-scale), ( \sigma_f^2 ) (variance) | Infinitely differentiable, stationary, isotropic. | Modeling smooth, continuous property landscapes (e.g., phase stability as a function of composition). |

| Matérn 3/2 | ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') = \sigma_f^2 \left(1 + \frac{\sqrt{3}|\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{x}'|}{l}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}|\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{x}'|}{l}\right) ) | ( l, \sigma_f^2 ) | Once differentiable, less smooth than RBF, stationary. | Modeling properties with possible abrupt changes or higher noise (e.g., catalytic activity thresholds). |

| Periodic | ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') = \sigma_f^2 \exp\left(-\frac{2\sin^2(\pi|\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{x}'|/p)}{l^2}\right) ) | ( l, \sigma_f^2, p ) (period) | Captures repeating patterns. | Modeling periodic trends (e.g., properties across periodic table groups or crystal structures). |

| Linear | ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') = \sigmab^2 + \sigmaf^2 (\mathbf{x} - c)(\mathbf{x}' - c) ) | ( \sigmab^2, \sigmaf^2, c ) | Results in linear regression models. | As a component in kernel sums for capturing global linear trends in processing-structure-property relationships. |

Protocol: Standard Workflow for GP Regression in Materials Discovery

This protocol outlines the steps to build and use a GP model for predicting material properties.

Protocol 1: Gaussian Process Regression for Predictive Materials Synthesis

Objective: To construct a probabilistic model that predicts a target material property from synthesis or compositional parameters and identifies the next optimal experiment.

Materials & Software:

- Dataset: Historical experimental data with input parameters (features) and measured output (target property).

- Software: Python with libraries:

scikit-learn,GPy,GPflow, orBoTorch.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Compile a dataset ( \mathcal{D} = {(\mathbf{x}i, yi)}{i=1}^n ), where ( \mathbf{x}i ) is a vector of synthesis conditions and ( y_i ) is the measured property.

- Standardize input features (zero mean, unit variance) and center target values.

- Split data into training (80-90%) and hold-out test (10-20%) sets.

Model Specification & Training:

- Select a Kernel: Choose a kernel (or sum/product of kernels) based on prior knowledge (see Table 1). An RBF + Noise kernel is a common starting point: ( k{\text{total}}(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') = k{\text{RBF}}(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') + \sigman^2 \delta{\mathbf{x}\mathbf{x}'} ).

- Initialize Hyperparameters: Set initial guesses for ( l, \sigmaf^2, \sigman^2 ).

- Optimize Hyperparameters: Maximize the log marginal likelihood ( \log p(\mathbf{y} | \mathbf{X}) ) using a conjugate gradient optimizer (e.g., L-BFGS-B). This automatically balances data fit and model complexity.

Prediction & Uncertainty Quantification:

- For a new test input ( \mathbf{x}* ), the GP provides a predictive posterior distribution: a mean ( \mu* ) and variance ( \sigma^2_* ).

- The mean ( \mu* ) is the predicted property value. The variance ( \sigma^2* ) quantifies the model's uncertainty, typically high in regions of the parameter space far from training data.

Model Validation:

- Use the hold-out test set to evaluate performance metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and the standardized negative log predictive probability.

- Visually inspect predictions vs. actual plots and uncertainty calibration.

Decision & Design Loop (Bayesian Optimization):

- Define an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement, Upper Confidence Bound) using the GP's predictive mean and variance.

- Propose the next synthesis experiment at ( \mathbf{x}_{\text{next}} = \arg\max \text{Acquisition}(\mathbf{x}) ).

- Run the experiment, obtain ( y_{\text{next}} ), append to the training dataset, and retrain the GP model. Iterate.

Key Considerations:

- Dimensionality: GP inference scales as ( O(n^3) ) with the number of data points ( n ). For large ( n ) (>10,000), use sparse GP approximations.

- Initial Data: A space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube) is recommended for initial dataset construction.

Application in Drug Development: ADMET Property Prediction

GP models are increasingly applied in early-stage drug discovery to predict Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties from molecular descriptors or fingerprints, providing uncertainty estimates crucial for risk assessment.

Table 2: Example GP Performance on ADMET Prediction Benchmarks (Recent Literature)

| Target Property | Dataset Size (Train/Test) | Kernel Used | Best Model RMSE (GP vs. Other) | Key Advantage of GP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility (logS) | ~10,000 / ~1,000 | Composite (Tanimoto + RBF) | GP: 0.68, Random Forest: 0.71 | Better calibration on novel chemical scaffolds. |

| hERG Inhibition (pIC50) | ~8,000 / ~500 | Matérn 3/2 | GP: 0.52, Neural Net: 0.50 | Reliable uncertainty estimates flagged false negatives in safety screening. |

| Hepatic Clearance | ~1,500 / ~150 | RBF | GP: 0.31, SVR: 0.33 | Effective in data-scarce regime; guided cost-effective data acquisition. |

Protocol: GP for Virtual Screening with Uncertainty

This protocol details using a GP model as a probabilistic filter in virtual screening.

Protocol 2: Uncertainty-Aware Virtual Screening for Lead Optimization

Objective: To prioritize compounds from a large virtual library for synthesis and testing based on predicted property and associated confidence.

Materials:

- Software:

RDKit(for fingerprinting),GPfloworBoTorch. - Data: A curated dataset of known actives/inactives or continuous property values for a target.

- Library: A virtual compound library in SMILES format.

Procedure:

- Feature Representation:

- Convert all molecules (training data and virtual library) to a fixed-length numerical representation. Morgan fingerprints (ECFP4) with 2048 bits are a robust standard.

- Model Training:

- Train a GP classification (for activity) or regression (for potency) model on the known data using a kernel suitable for molecular fingerprints (e.g., Tanimoto kernel for binary fingerprints).

- Optimize hyperparameters via marginal likelihood maximization.

- Library Prediction & Prioritization:

- Pass the entire virtual library through the trained GP model to obtain two vectors for each molecule: predictive mean (probability of activity or predicted potency) and predictive variance (uncertainty).

- Rank compounds not only by a high mean score but also by a high uncertainty-weighted score (e.g., Mean + κ × Standard Deviation). This balances exploitation (good predictions) and exploration (high uncertainty).

- Batch Selection:

- Use a batch Bayesian optimization algorithm (e.g., q-Expected Improvement) to select a diverse batch of 5-20 compounds that jointly maximize information gain and property improvement, considering molecular similarity to avoid redundancy.

Analysis:

- The selected batch of compounds is synthesized and tested.

- The new data is used to update the GP model, closing the iterative design-make-test-analyze cycle with improved probabilistic guidance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for GP-Driven Materials & Drug Discovery Research

| Item/Category | Example/Product | Function in GP Research |

|---|---|---|

| GP Software Framework | GPflow (TensorFlow), BoTorch (PyTorch), scikit-learn |

Provides core algorithms for building, training, and deploying GP models, including scalable variational inference and Bayesian optimization. |

| Chemistry Toolkits | RDKit, Open Babel |

Converts chemical structures (SMILES, SDF) into numerical descriptors or fingerprints required as input for GP models. |

| Automated Experimentation | Chemputer, Liquid Handling Robots |

Physically executes the synthesis or screening experiments proposed by the GP's Bayesian optimization loop, enabling closed-loop discovery. |

| High-Throughput Characterization | Plate readers, HPLC-MS, XRD robots | Rapidly generates the high-quality experimental data (target properties y) needed to train and validate GP models. |

| Benchmark Datasets | Materials Project, MoleculeNet, ChEMBL | Provides standardized public datasets for developing and benchmarking GP models against other machine learning methods. |

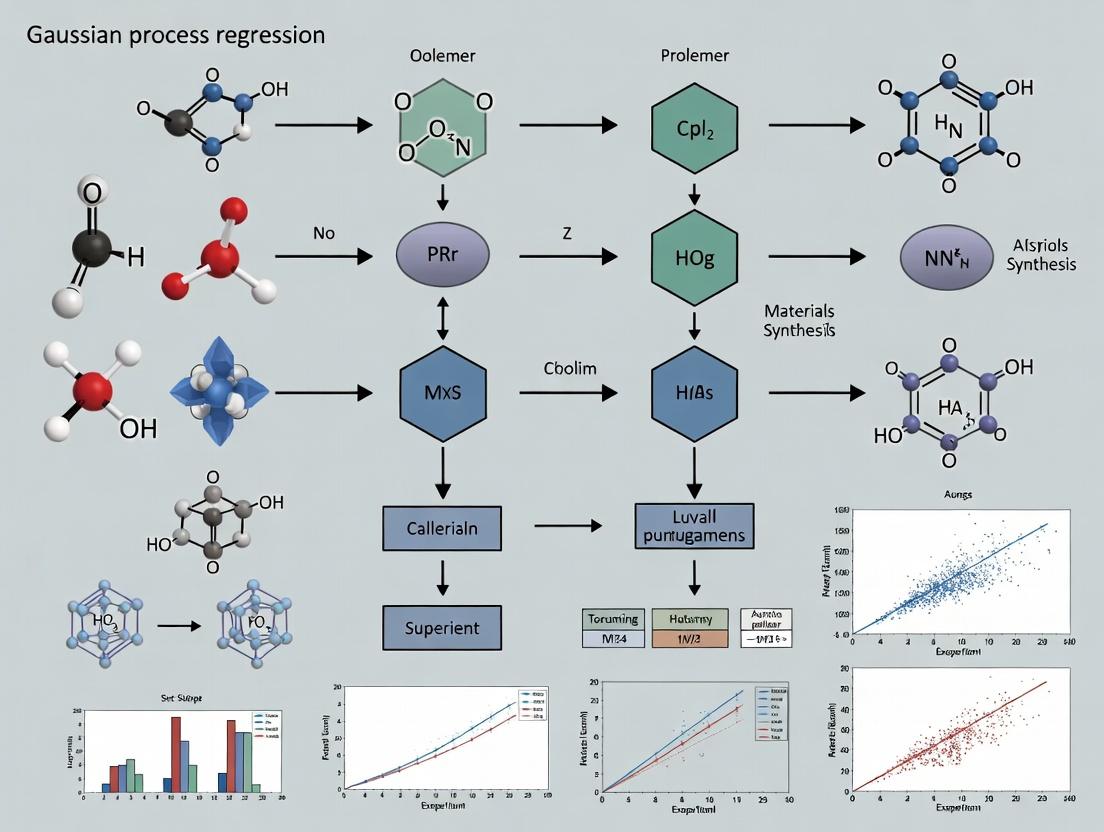

Visual Workflows

GP-Driven Materials Discovery Closed Loop

Uncertainty-Aware Virtual Screening with GP

Why GPR for Materials Synthesis? Addressing Complexity, Scarcity, and Cost of Experiments.

Within the broader thesis on the application of Gaussian process regression (GPR) in materials science, this document addresses a critical bottleneck: the experimental discovery and optimization of new materials. The synthesis of advanced materials—from porous frameworks and battery electrodes to pharmaceutical cocrystals—is plagued by high-dimensional parameter spaces, scarcity of key reagents (e.g., critical metals, specialized ligands), and the prohibitive cost of exhaustive experimentation. This article posits that GPR, a Bayesian non-parametric machine learning model, is uniquely suited to navigate these challenges. By building probabilistic models from limited data, GPR can predict optimal synthesis conditions and material properties, actively quantify uncertainty, and guide experimental campaigns towards the most informative trials, thereby dramatically reducing the required number of experiments.

Table 1: Quantitative Synthesis Challenges in Selected Material Classes

| Material Class | Key Cost Driver (per experiment) | Typical Parameter Space Dimensionality | Example Scarce/Critical Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Solvothermal reactor time, ligand cost | 5-8 (Temp, Time, Solvent Ratio, pH, Modulator Conc.) | Rare-earth metals, specialized organic linkers |

| Inorganic Perovskites (PVK) | High-temperature annealing, glovebox use | 4-6 (Precursor Ratios, Spin Speed, Anneal Temp/Time) | Indium, Lead (for some PVKs) |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts (e.g., Pt alloys) | Noble metal precursor cost, characterization | 6-10 (Metal Ratios, Support, Calcination Temp/Time) | Platinum, Palladium, Iridium |

| Pharmaceutical Cocrystals | API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) cost | 3-5 (API:Coformer Ratio, Solvent, Temp, Cooling Rate) | High-purity API (grams-scale early R&D) |

| Solid-State Battery Electrolytes | Dry room operation, lithium precursor cost | 5-7 (Composition, Sintering Temp/Time, Pressure) | Lithium metal, Germanium |

GPR Application Notes for Synthesis Optimization

Note 1: Active Learning with GPR for Expensive Experiments GPR excels in closed-loop, Bayesian optimization (BO) workflows. A GPR model, trained on an initial small dataset, predicts the performance (e.g., yield, surface area, conductivity) across the unexplored parameter space and simultaneously provides an uncertainty estimate (prediction variance). An acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) uses these predictions to propose the single next experiment that most likely improves the target or reduces global uncertainty. This iterative "experiment-propose-update" loop converges to optimal conditions in 3-5 times fewer experiments than grid or one-factor-at-a-time searches.

Note 2: Handling Multi-Objective and Constrained Problems Materials synthesis often requires balancing multiple, competing objectives (e.g., maximize porosity while minimizing cost). GPR can model multiple outputs (via co-kriging or independent GPRs) to construct a Pareto front of optimal trade-offs. Furthermore, knowledge-based constraints (e.g., "pH must be >7") can be integrated into the acquisition function to avoid proposing invalid or dangerous experiments.

Note 3: GPR with Sparse or Heterogeneous Data GPR can incorporate different data types (continuous, categorical) via appropriate kernel functions. For mixed parameter spaces (e.g., solvent type + temperature), composite kernels (e.g., Matern for continuous variables + symmetric for categorical) allow effective modeling from diverse data sources, including legacy literature data.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: GPR-Guided MOF Synthesis

Protocol Title: Bayesian Optimization of ZIF-8 Crystallinity using GPR.

Objective: To identify the optimal combination of synthesis temperature and modulator concentration to maximize the crystallinity (as measured by XRD peak intensity) of ZIF-8 in 10 or fewer experiments.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials:

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) | Metal ion source. |

| 2-Methylimidazole (HmIm) | Organic linker. |

| Methanol (MeOH) | Solvent for synthesis. |

| Sodium formate (HCOONa) | Modulator (competes with linker, affects crystallization kinetics). |

| Polypropylene vials (20 mL) | Reaction vessels. |

| Benchtop centrifuge | For product isolation. |

| X-ray Diffractometer (XRD) | For quantifying crystallinity (primary target metric). |

Procedure:

- Define Search Space: Temperature: 25°C - 85°C; Modulator (HCOONa) Concentration: 0 mM - 100 mM.

- Initial Design: Perform a space-filling initial design of 4 experiments (e.g., via Latin Hypercube Sampling).

- Synthesis Execution: a. For each condition, dissolve Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O (0.6 mmol) and HmIm (4.8 mmol) in 15 mL MeOH in separate vials. b. Dissolve the specified mass of HCOONa in the linker solution. c. Rapidly mix the two solutions. Place the vial in a pre-heated oven or heat block at the target temperature. d. React for 24 hours. e. Centrifuge the product, wash with fresh MeOH (3x), and dry at 60°C overnight.

- Characterization: Acquire XRD patterns for all samples. Calculate a crystallinity score (e.g., integrated intensity of the primary diffraction peak ~7.2° 2θ).

- GPR Modeling & Next Experiment Proposal: a. Train a GPR model (Matern 5/2 kernel) on the current dataset (parameters → crystallinity score). b. Use the model and an Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function to compute the (Temperature, Concentration) point that maximizes EI. c. Propose this condition as the next experiment.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 3-5 until a predefined crystallinity threshold is met or the experimental budget (10 runs) is exhausted. The model's predicted optimum should be validated with a final experiment.

Visualizing the GPR-Driven Synthesis Workflow

Diagram 1: GPR Bayesian Optimization Loop for Materials Synthesis

Diagram 2: GPR Model vs. High-Cost Experimental Grid Search

Application Notes for Gaussian Process Regression in Materials Synthesis

Within the broader thesis on accelerating materials discovery via Gaussian process (GP) regression, mastering its three core components is critical. These components provide the probabilistic framework for predicting material properties and guiding synthesis experiments.

1. Core Components in the Materials Context

- Mean Function (m(x)): Represents the prior expectation of the material property (e.g., bandgap, yield strength) before observing data. In materials science, this is often a simple constant (e.g., the average of known data) or a domain-informed physical model (e.g., a linear function of composition descriptors).

- Covariance Kernel (k(x, x')): Encodes assumptions about the smoothness, periodicity, and trends in the material property function. It defines the similarity between two synthesis conditions or material descriptors (x, x'), crucially determining the interpolation behavior of the GP.

- Hyperparameters (θ): Parameters of the kernel and mean function that are learned from data. They control the characteristic length scales, variance, and noise of the model, directly influencing prediction confidence.

2. Quantitative Comparison of Common Covariance Kernels Table 1: Kernel Functions and Their Influence on Material Property Predictions

| Kernel Name | Mathematical Form (Isotropic) | Key Hyperparameters | Material Science Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Squared Exponential (SE) | $k(r) = \sigma_f^2 \exp(-\frac{r^2}{2l^2})$ | $l$ (length-scale), $\sigma_f^2$ (signal variance) | Assumes very smooth, infinitely differentiable functions. Useful for modeling bulk properties that vary smoothly with composition. |

| Matérn (ν=3/2) | $k(r) = \sigma_f^2 (1 + \frac{\sqrt{3}r}{l}) \exp(-\frac{\sqrt{3}r}{l})$ | $l$, $\sigma_f^2$ | Models functions with less smoothness than SE. Effective for capturing properties that may change more abruptly near phase boundaries. |

| Periodic | $k(r) = \sigma_f^2 \exp(-\frac{2\sin^2(\pi r / p)}{l^2})$ | $p$ (period), $l$, $\sigma_f^2$ | Ideal for properties expected to exhibit periodic behavior, e.g., with layering thickness or in crystalline lattice parameters. |

| Linear | $k(x, x') = \sigmab^2 + \sigmaf^2 (x \cdot x')$ | $\sigmab^2$ (bias), $\sigmaf^2$ (variance) | Results in linear posterior mean. Can be used as part of a composite kernel to embed a known linear trend from a simple physical model. |

where $r = |x - x'|$.

3. Experimental Protocol: GP Model Construction and Active Learning Cycle

Protocol Title: Iterative Materials Optimization using Gaussian Process Regression with Active Learning

Objective: To synthesize a material (e.g., a perovskite semiconductor) with an optimized target property (e.g., photovoltaic efficiency) using a minimal number of experiments.

Materials & Computational Toolkit:

- High-Throughput Synthesis Robot: For automated, precise sample preparation.

- Characterization Suite (e.g., XRD, PL, IV Tester): For measuring target property.

- Computational Environment (Python with GPy, scikit-learn, or GPflow): For GP model implementation.

- Descriptor Generation Software: To compute material descriptors (e.g., atomic radii, electronegativity, valence).

Procedure:

- Initial Design of Experiments (DoE): Select an initial set of 10-20 synthesis conditions (e.g., precursor ratios, annealing temperatures) using a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube) across the defined parameter space.

- Synthesis & Characterization: Execute synthesis and characterize the target property for each condition in the initial set. Assemble dataset D = {(xi, yi)} for i = 1...N.

- GP Model Training:

a. Preprocessing: Standardize input descriptors (x) and property values (y).

b. Kernel Selection: Choose a composite kernel (e.g.,

Linear + Matern) based on domain knowledge from prior research. c. Hyperparameter Optimization: Maximize the log marginal likelihood $p(\mathbf{y}|X, \theta)$ with respect to hyperparameters θ using a gradient-based optimizer (e.g., L-BFGS-B). * Optimization Function: $\log p(\mathbf{y}|X, \theta) = -\frac{1}{2}\mathbf{y}^T(K + \sigman^2I)^{-1}\mathbf{y} - \frac{1}{2}\log|K + \sigman^2I| - \frac{n}{2}\log 2\pi$ * where $K$ is the covariance matrix and $\sigma_n^2$ is the noise variance. - Active Learning & Candidate Selection: a. Using the trained GP, predict the mean $\mu(x*)$ and variance $\sigma^2(x)$ for a large pool of candidate synthesis conditions. b. Select the next condition to synthesize by maximizing an *acquisition function, such as Expected Improvement (EI): * EI Equation: $EI(x*) = (\mu(x) - y_{best} - \xi)\Phi(Z) + \sigma(x_)\phi(Z)$ * where $Z = \frac{\mu(x*) - y{best} - \xi}{\sigma(x*)}$, $\Phi$ and $\phi$ are the CDF and PDF of the standard normal, and $y{best}$ is the current best-observed property. c. Synthesize and characterize the selected candidate.

- Iteration: Update dataset D with the new result. Retrain the GP model. Repeat steps 4-5 until a performance threshold or experimental budget is reached.

4. Visualizing the GP-Driven Materials Discovery Workflow

Diagram 1: Active learning cycle for materials synthesis.

5. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for GP-Guided Materials Research

| Item Name | Function/Application in GP-Driven Synthesis |

|---|---|

| Precursor Solution Libraries | High-purity, standardized stock solutions to enable rapid, automated formulation of diverse compositions (e.g., metal salts for perovskites). |

| Automated Spin Coater/Deposition | Ensures reproducible thin-film synthesis for high-throughput sample generation from liquid precursors. |

| Rapid Thermal Annealer (RTA) | Provides fast, controlled thermal processing with parameterized programs, a key variable in synthesis optimization. |

| X-ray Diffractometer (XRD) | For primary characterization of crystal structure and phase purity, a common descriptor or constraint in the GP model. |

| Photoluminescence (PL) Quantum Yield Setup | Measures optoelectronic property (e.g., bandgap, defect density) as a target for optimization. |

| J-V Characterization Station | Measures final device performance (efficiency, fill factor) as the ultimate target property for optimization loops. |

| Python GP Library (e.g., GPyTorch) | Provides flexible, scalable framework for building custom GP models with composite kernels and training on GPU. |

| Descriptor Calculation Library (e.g., pymatgen) | Computes material features (ionic radii, coordination numbers) from compositions to serve as informative model inputs (x). |

The Role of Uncertainty Quantification in Guiding Synthesis Experiments

In Gaussian process regression (GPR) based materials synthesis research, uncertainty quantification (UQ) is not merely a statistical metric but a critical decision-making guide. It allows researchers to distinguish between regions of chemical space that are well-explored versus those that are genuinely unpredictable, enabling targeted experimentation. This protocol details the application of UQ for directing the synthesis of novel materials, focusing on active learning cycles where predictive uncertainty directly informs the next set of experiments.

Core Principles: Uncertainty in GPR for Synthesis

A Gaussian process model provides both a predicted mean (μ) and a variance (σ²) for any point in the feature space (e.g., reaction conditions, precursor ratios). The variance represents the model's epistemic uncertainty—lack of knowledge due to sparse data. In synthesis campaigns, we exploit this by formulating an acquisition function that balances exploring high-uncertainty regions and exploiting high-performance predictions.

Table 1: Common Acquisition Functions for Synthesis Guidance

| Function Name | Mathematical Formula | Primary Use Case | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | μ + κ * σ | High-risk exploration for novel phases | κ (exploration weight) |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | E[max(0, f - fᵇᵉˢᵗ)] | Optimizing a target property (e.g., yield) | Incumbent fᵢᵇ |

| Predictive Entropy Search | Maximize mutual information | Global mapping of a synthesis landscape | Computationally intensive |

Table 2: Impact of UQ-Guided Synthesis on Experimental Efficiency

| Study System (Search) | Random Experimentation Yield (%) | UQ-Guided Yield (%) | Experiments Saved (%) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perovskite Oxide Discovery | 12 | 45 | ~60 | 2023 |

| Organic Photovoltaic Donor | 18 | 39 | ~50 | 2024 |

| Heterogeneous Catalyst (Alloy) | 22 | 57 | ~65 | 2023 |

Detailed Protocol: An Active Learning Cycle for Nanoparticle Synthesis

Protocol 1: Implementing a UQ-Guided Synthesis Workflow

Objective: To discover synthesis conditions for monodisperse metal-organic framework (MOF) nanoparticles with a target particle size.

Materials & Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MOF Synthesis Campaign

| Item/Chemical | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration for UQ |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salt Precursor (e.g., ZrCl₄) | Provides metal nodes for framework. | Concentration is a key feature variable. |

| Organic Linker (e.g., H₂BDC) | Connects metal nodes into porous framework. | Linker concentration and ratio to metal. |

| Modulating Acid (e.g., acetic acid) | Controls crystallization kinetics & size. | Critical continuous variable for UQ. |

| Solvent (e.g., DMF) | Reaction medium. | Fixed variable in this design. |

| Automated Synthesis Platform | Enables precise control and reproducibility. | Essential for high-fidelity data generation. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Initial Dataset Creation (Design of Experiments):

- Perform 10-15 initial syntheses using a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube) across your defined parameter space (e.g., [Precursor], [Linker], [Modulator], Temperature, Time).

- Characterize key output properties: Primary (Target Particle Size, nm), Secondary (Yield, Crystallinity).

GPR Model Training & UQ:

- Feature Standardization: Standardize all input parameters to zero mean and unit variance.

- Model Definition: Construct a GPR model with a Matérn kernel (ν=5/2). Use a composite kernel if categorical variables exist.

- Training: Optimize hyperparameters (length scales, noise) by maximizing the log marginal likelihood.

- Uncertainty Mapping: For the entire parameter space, compute the posterior predictive mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) for the target property.

Next-Experiment Selection via Acquisition Function:

- Calculate the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) for a dense grid of candidate conditions:

UCB(x) = μ(x) + 2σ(x). - Decision: Select the condition

x*with the maximum UCB score for the next experiment. This condition optimally balances predicted performance and model uncertainty.

- Calculate the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) for a dense grid of candidate conditions:

Execution, Characterization & Iteration:

- Synthesize MOF nanoparticles under condition

x*. - Characterize the output (Size, Yield).

- Critical Step: Append the new {

x*, result} pair to the training dataset. - Retrain the GPR model with the expanded dataset.

- Repeat from Step 2 for 5-10 cycles or until the target is met or uncertainty is sufficiently reduced.

- Synthesize MOF nanoparticles under condition

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Active Learning Cycle for Synthesis

Synthesis Decision Map Based on UQ

Application Notes

In Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) for materials synthesis and drug development, understanding key Bayesian optimization (BO) terminologies is critical for efficient experimental design. These concepts form the core of an iterative loop where computational models guide physical experimentation to discover novel materials or compounds with optimal properties.

Posterior Distributions represent the updated belief about the unknown objective function (e.g., material yield, drug potency) after observing experimental data. In GPR, the posterior is a Gaussian distribution defined by a mean function (the predicted property) and a covariance function (the uncertainty). This distribution encapsulates both the model's predictions and its confidence, enabling researchers to quantify the trustworthiness of model-guided suggestions for the next experiment.

Confidence Intervals (CIs), derived directly from the posterior distribution, provide a range of plausible values for the objective function at any given input point (e.g., synthesis temperature, reagent concentration). A 95% CI indicates a region where the true function value is expected to lie with 95% probability, given the model. In materials research, wide CIs highlight regions of the parameter space where the model is uncertain, often corresponding to unexplored experimental conditions.

Acquisition Functions are utility functions that leverage the posterior distribution to balance exploration (sampling in high-uncertainty regions) and exploitation (sampling where the predicted performance is high) to propose the next experiment. They quantifiably score all candidate experiments, with the optimum of the acquisition function becoming the next synthesis or test to perform. This automates the decision-making process in high-throughput experimentation.

The synergistic application of these terminologies creates a closed-loop, autonomous research system. A GPR model, built from initial data, provides a posterior distribution and CIs across the search space. An acquisition function analyzes this output to nominate a specific experimental condition. After the experiment is executed and its result measured, the new data point updates the GPR posterior, and the loop repeats, rapidly converging toward optimal material formulations or drug candidates.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bayesian Optimization Loop for Perovskite Synthesis Optimization

Objective: To autonomously discover annealing temperature and precursor ratio maximizing solar cell power conversion efficiency (PCE). Materials: Lead iodide, methylammonium iodide, dimethylformamide, substrates, spin coater, thermal annealer, PCE tester.

- Initial Design: Perform 10 initial experiments using a space-filling Latin Hypercube Design across the defined ranges (Temperature: 80-180°C, Ratio: 0.8-1.2).

- Data Collection: Synthesize perovskite film for each condition and measure PCE (%).

- Model Initialization: Construct a Gaussian Process model with a Matérn kernel. The model input is the 2D experimental conditions; the output is measured PCE.

- Posterior & CI Calculation: For the GP model, compute the posterior mean and variance for a fine grid of candidate conditions. Calculate the 95% CI as: Mean ± 1.96 * √(Variance).

- Acquisition: Evaluate the Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function across the candidate grid. Select the condition (Temperature, Ratio) that maximizes EI.

- Validation Experiment: Execute the synthesis and PCE measurement at the proposed condition.

- Model Update: Append the new (input, output) data pair to the training dataset.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 4-7 for a predetermined budget (e.g., 20 iterations) or until PCE convergence criterion is met (e.g., < 1% improvement over 5 iterations).

- Final Validation: Synthesize and test the top-3 predicted conditions in triplicate to confirm performance.

Protocol 2: GP-Guided Confirmation of Optimal Drug Formulation Stability

Objective: To identify and confirm the optimal pH and excipient concentration maximizing shelf-life stability of a biologic drug. Materials: Lyophilized drug protein, buffer solutions (pH 4.0-7.0), polysorbate excipient (0.01-0.1% w/v), HPLC system for aggregation analysis.

- Historical Data Compilation: Gather existing stability data (% monomer after 6 months at 25°C) for 15-20 historical formulations.

- GP Surrogate Model: Train a GP model on the historical data (inputs: pH, excipient concentration; output: % monomer).

- Define Target: Set a stability target (e.g., >95% monomer).

- Probability of Improvement Calculation: Use the GP posterior to compute the "Probability of Improvement" acquisition function over a fine grid of pH and concentration values. This function estimates the likelihood that a new formulation will exceed the 95% target.

- Candidate Selection: Identify the formulation parameters that maximize the Probability of Improvement.

- Confirmatory Experiment: Prepare the proposed formulation in triplicate. Place samples on accelerated stability study (40°C/75% RH) and monitor monomericity via HPLC at 0, 1, 3, and 6 months.

- Model Refinement & Decision: Update the GP model with confirmatory results. If target is met, proceed to scale-up. If not, iterate the BO loop with an expanded design space.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Common Acquisition Functions in Materials Synthesis BO

| Acquisition Function | Key Formula (Simplified) | Optimization Bias | Best Use Case in Materials Science |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | PI(x) = Φ( (μ(x) - f(x⁺) - ξ) / σ(x) ) | High Exploitation | Refining a known good synthesis near a local optimum. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | EI(x) = (μ(x)-f(x⁺)-ξ)Φ(Z) + σ(x)φ(Z) | Balanced | General-purpose optimization of yield or property. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | UCB(x) = μ(x) + κ * σ(x) | Tunable (via κ) | Forced exploration of unexplored processing conditions. |

| Thompson Sampling | Sample a function f̂ from posterior, optimize f̂. | Stochastic Balance | High-noise experiments or very large candidate sets. |

Key: μ(x): posterior mean; σ(x): posterior std. dev.; f(x⁺): current best observation; Φ, φ: CDF/PDF of std. normal; ξ, κ: tuning parameters.

Table 2: Example GP Posterior Output for a Candidate Polymer Synthesis

| Candidate Input (Catalyst mmol) | Posterior Mean (Predicted Yield %) | Posterior Std. Deviation (%) | 95% Confidence Interval (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 68.2 | 12.5 | [43.7, 92.7] |

| 2.0 | 85.7 | 5.1 | [75.7, 95.7] |

| 2.5 | 82.4 | 8.9 | [65.0, 99.8] |

| 3.0 | 70.5 | 14.3 | [42.5, 98.5] |

Interpretation: The model is most certain about its prediction at 2.0 mmol (narrowest CI). The highest lower bound of the CI is at 2.0 mmol, suggesting it is a low-risk, high-reward candidate for the next experiment.

Visualizations

Title: Bayesian Optimization Loop for Autonomous Materials Synthesis

Title: Relationship Between Prior, Data, Posterior, and Confidence Interval

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GP-Guided Materials Synthesis

| Item | Function in GP-BO Workflow | Example in Perovskite/Pharma Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Robotic Synthesizer | Automates the execution of proposed experiments from the BO loop, ensuring rapid, precise, and reproducible synthesis of candidate materials or formulations. | Dispensing precursors for 96 different perovskite compositions in a single run. |

| Automated Characterization Suite | Provides the quantitative output (y) for the GP model. Must be fast and reliable to keep pace with the BO cycle. | Parallel UV-Vis spectroscopy for bandgap measurement, or HPLC for drug purity/aggregation analysis. |

| Standardized Chemical Libraries | Well-defined, high-purity starting materials (precursors, solvents, excipients) that ensure experimental variance is due to chosen parameters, not reagent inconsistency. | Libraries of metal salts and organic cations for perovskites; graded buffers and stabilizers for biologics. |

| Data Management Platform (ELN/LIMS) | Curates and stores all (input, output) data pairs in a structured, accessible format for seamless model training and updating. Crucial for maintaining the experimental history. | Electronic Lab Notebook with structured forms for synthesis parameters and linked analytical results. |

| Bayesian Optimization Software | The computational engine that implements GP regression and acquisition function optimization. | Python libraries like scikit-learn, GPyTorch, or BoTorch. |

Building the Loop: A Step-by-Step Guide to Implementing GPR in Synthesis Workflows

Within Gaussian process regression (GPR) frameworks for materials synthesis, the quality of predictions is intrinsically linked to the quality and representation of the input data. Feature engineering transforms raw process parameters (e.g., temperature, time) and chemical compositions (e.g., molar ratios, dopant concentrations) into a structured, informative format that a GPR model can effectively learn from. This protocol details the systematic creation of descriptors critical for synthesis outcome prediction.

Core Feature Categories & Data Tables

Table 1: Primary Process Parameter Features

| Feature Category | Example Features | Data Type | Preprocessing Required | GPR Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic | Temperature (°C), Pressure (atm) | Continuous | Normalization, Log-transform | High; directly impacts kinetics |

| Temporal | Reaction time (hr), Ramp rate (°C/min) | Continuous | Scaling, Binning for regimes | High; governs reaction completion |

| Environment | Atmosphere (O₂, N₂, Ar), Flow rate (sccm) | Categorical/Continuous | One-hot encoding, Scaling | Medium-High; affects phase stability |

| Mechanical | Stirring speed (rpm), Ultrasound power (W) | Continuous | Standardization | Variable; influences mixing & nucleation |

Table 2: Compositional & Structural Descriptors

| Descriptor Type | Calculation/Origin | Example for Perovskite (ABO₃) | Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric | Raw molar ratios | Ratio of A:B, % of X-site vacancy | Continuous |

| Ionic Radii | Shannon radii databases | Tolerance factor, A-site cation radius (Å) | Continuous |

| Electronegativity | Pauling/Allen scales | Average χ of B-site, Δχ(A,B) | Continuous |

| Valence State | Known oxidation states | B-site charge, overall neutrality metric | Discrete/Continuous |

| Thermodynamic | Formation energy (DFT/experimental) | ΔH_f per atom (eV/atom) | Continuous |

Experimental Protocols for Feature Generation

Protocol 3.1: Calculating Tolerance Factor from Compositional Data

Objective: Derive the Goldschmidt tolerance factor (t) for perovskite precursors. Materials: Precursor composition list, Shannon ionic radii database. Procedure:

- For composition AₐBᵦXₓ, identify the ionic radii rA, rB, r_X for the specific coordination number.

- Calculate the tolerance factor using: t = (r_A + r_X) / [√2 * (r_B + r_X)]

- Log the value alongside the composition ID. Note: t > 1 indicates a tilted structure, t ~ 1 indicates a cubic perovskite.

Protocol 3.2: One-Hot Encoding for Categorical Process Parameters

Objective: Convert categorical parameters (e.g., "Atmosphere") into a numerical format. Procedure:

- List all unique categories for the parameter (e.g., O₂, N₂, Ar).

- Create new binary columns:

Atmosphere_O2,Atmosphere_N2,Atmosphere_Ar. - For each synthesis entry, set the corresponding column to 1 and others to 0.

Example Output Row:

Atmosphere_O2=1, Atmosphere_N2=0, Atmosphere_Ar=0

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Feature Engineering |

|---|---|

| Pymatgen | Python library for analyzing materials composition, generating structural descriptors (ionic radii, coordination numbers). |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics toolkit for generating molecular descriptors from organic precursors (e.g., molecular weight, polarity). |

| Thermodynamic Databases (FactSage, NIST-JANAF) | Provide reference data for calculating approximate formation energies or phase stability flags. |

| Shannon Ionic Radii Table | Standard reference for ionic radii used in calculating tolerance factors and other steric descriptors. |

| Scikit-learn | Provides robust scalers (StandardScaler, MinMaxScaler) and encoders (OneHotEncoder) for preprocessing features before GPR. |

Feature Engineering Workflow for GPR Synthesis Modeling

Feature Engineering Workflow for GPR

Logical Decision Tree for Feature Selection

Feature Selection Decision Tree

Data Integration and Validation Protocol

Protocol 7.1: Train-Test Split for Temporal Synthesis Data

Objective: Avoid data leakage in time-dependent synthesis campaigns. Procedure:

- Sort all synthesis experiments chronologically by date.

- Reserve the latest 20% of experiments as the test set.

- Use the earliest 80% for training/validation.

- Apply feature scaling: fit

StandardScaleron training set only, then transform both training and test sets.

Table 3: Example Engineered Feature Vector for a Synthesis Run

| Feature | Value | Engineered From |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 0.87 | Scaled raw value (850°C) |

| Time_log | 1.24 | log(Reaction time in hrs) |

| Atmosphere_N2 | 1 | Categorical "N2" |

| Tolerance_Factor | 0.98 | Calculated from A/B/X radii |

| AvgBsiteElectroneg | 1.65 | Mean Pauling χ of B-site cations |

Selecting and Customizing Kernels (RBF, Matern, Periodic) for Chemical & Physical Relationships

Within the broader thesis on Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) for materials synthesis research, the selection and customization of kernel functions is the critical step that encodes prior assumptions about chemical and physical relationships. This determines the model's ability to predict novel material properties, optimize synthesis parameters, and accelerate the discovery pipeline. These protocols provide actionable guidance for kernel engineering tailored to molecular and crystalline systems.

Kernel Functions: Quantitative Comparison & Selection Guide

The following table summarizes the mathematical forms, hyperparameters, and primary use cases for the three core kernels in materials informatics.

Table 1: Core Kernel Functions for Chemical & Physical GPR Models

| Kernel Name | Mathematical Form (k(x, x′)) | Key Hyperparameters | Typical Application in Materials Synthesis | Differentiability / Smoothness Assumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Basis Function (RBF) | σ² exp( -‖x - x′‖² / (2l²) ) | Length-scale (l), Variance (σ²) | Modeling bulk properties (e.g., band gap, formation energy) from composition; assumes smooth, continuous relationships. | Infinitely differentiable. Assumes very smooth functions. |

| Matérn (ν=3/2) | σ² (1 + √3 ‖x - x′‖ / l ) exp( -√3 ‖x - x′‖ / l ) | Length-scale (l), Variance (σ²) | Modeling properties with moderate roughness or noise (e.g., catalytic activity, ionic conductivity). | Once differentiable. Less smooth than RBF. |

| Matérn (ν=5/2) | σ² (1 + √5 ‖x - x′‖ / l + 5‖x - x′‖²/(3l²)) exp( -√5 ‖x - x′‖ / l ) | Length-scale (l), Variance (σ²) | Similar to ν=3/2, but for slightly smoother phenomena (e.g., adsorption energies). | Twice differentiable. |

| Periodic | σ² exp( -2 sin²(π‖x - x′‖ / p) / l² ) | Period (p), Length-scale (l), Variance (σ²) | Capturing periodic trends (e.g., properties across the periodic table, crystal structure angles, rotational barriers). | Infinitely differentiable, periodic. |

Experimental Protocols for Kernel Validation & Customization

Protocol 3.1: Systematic Kernel Selection Workflow

Objective: To empirically determine the optimal kernel for a given materials dataset. Materials: Feature matrix (e.g., composition descriptors, synthesis conditions), target property vector (e.g., yield, conductivity), GPR software (e.g., GPyTorch, scikit-learn). Procedure:

- Data Partitioning: Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets using stratified sampling based on target value ranges.

- Baseline Model Fitting: Fit three separate GPR models using RBF, Matérn (ν=3/2), and Periodic kernels independently to the training set.

- Hyperparameter Optimization: For each model, optimize hyperparameters (length-scales, variance, period) by maximizing the log marginal likelihood on the training set using the L-BFGS-B algorithm (max 1000 iterations).

- Validation & Selection: Calculate the Negative Log Predictive Probability (NLPP) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) on the validation set. The kernel with the lowest NLPP is preferred as it best explains unseen data.

- Final Assessment: Retrain the selected kernel model on the combined training+validation set. Report final RMSE and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) on the held-out test set.

Protocol 3.2: Crafting Custom Composite Kernels

Objective: To build a kernel that captures multiple physical effects (e.g., a smooth trend with periodic oscillations). Materials: As in Protocol 3.1. Procedure:

- Additive Structure: For properties believed to be a sum of independent effects (e.g., bulk formation energy (RBF) + periodic element contribution (Periodic)), construct:

k_add = k_RBF + k_Periodic. - Multiplicative Structure: For modeling interactions or amplitude modulation (e.g., a periodic trend whose amplitude decays smoothly), construct:

k_mult = k_RBF * k_Periodic. - Hyperparameter Initialization: Initialize composite kernel hyperparameters using values obtained from single-kernel fits (Protocol 3.1).

- Optimization & Validation: Optimize all hyperparameters simultaneously via log marginal likelihood maximization. Validate using the NLPP/validation set method as in Step 4 of Protocol 3.1.

Visualization of Kernel Selection & Impact

Diagram Title: GPR Kernel Selection & Validation Workflow for Materials Data (80 chars)

Diagram Title: How Kernel Choice Encodes Physical Assumptions in GPR (73 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for GPR Kernel Experimentation in Materials Science

| Item / Solution | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| GPyTorch Library (Python) | A flexible, GPU-accelerated GPR framework. Essential for implementing custom kernels and handling large materials datasets. |

| Dragonfly or Bayesian Optimization Software | For automated global hyperparameter optimization of kernel length-scales, periods, and variances. |

| Matminer or Mat2Vec Feature Sets | Pre-computed compositional and structural descriptors for inorganic materials. Serve as the input feature vector (x) for the kernel. |

| SOAP or ACSF Descriptors | Atomic-centered symmetry functions for molecular/nanocluster systems. Capture local environment for kernel similarity assessment. |

| Standardized Benchmark Datasets (e.g., MatBench) | Curated materials property datasets (e.g., formation energies, band gaps) for validating and comparing kernel performance. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster Access | Log-likelihood optimization and cross-validation are computationally intensive; HPC is necessary for rigorous protocol execution. |

This protocol details the integration of Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) with Active Learning (AL) within a Bayesian Optimization (BO) loop, a cornerstone methodology for autonomous discovery in materials synthesis and drug development. Framed within a broader thesis on data-driven research, this approach systematically reduces the number of experiments required to identify optimal compositions or conditions by iteratively selecting the most informative samples based on model uncertainty and predicted performance.

The Bayesian Optimization Loop: Core Workflow

The loop combines a probabilistic surrogate model (GPR) with an acquisition function to guide experimentation. It iterates through: (1) training a GPR model on existing data, (2) using the acquisition function to compute the utility of unexplored candidates, (3) selecting and performing the experiment with the highest utility, and (4) updating the dataset and model.

Workflow Diagram

Diagram Title: The Bayesian Optimization Autonomous Discovery Loop

Key Components: Detailed Protocols

Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) Model Training

Function: Provides a probabilistic surrogate model that predicts the objective function (e.g., material property, drug activity) and quantifies uncertainty (variance).

Protocol:

- Data Standardization: Normalize input features (e.g., composition %, temperature) and target variable to zero mean and unit variance.

- Kernel Selection: Choose a kernel function defining covariance.

- Common Choice: Matérn 5/2 kernel (

k(xi, xj)) for modeling physical processes. - Formula:

(1 + sqrt(5)*r/ℓ + 5*r²/(3ℓ²)) * exp(-sqrt(5)*r/ℓ), whereris Euclidean distance,ℓis length-scale.

- Common Choice: Matérn 5/2 kernel (

- Model Training: Optimize kernel hyperparameters (length-scales ℓ, noise variance σ²) by maximizing the log marginal likelihood using L-BFGS-B.

- Output: A trained GPR model capable of predictive mean

μ(x*)and varianceσ²(x*)for any new inputx*.

Acquisition Function Calculation

Function: Balances exploration (high uncertainty) and exploitation (high predicted performance) to recommend the next experiment.

Protocol for Expected Improvement (EI):

- Using the trained GPR, predict mean (

μ) and standard deviation (σ) for all candidates in the search space. - Let

f_bestbe the current best observed target value. - Calculate improvement

I = μ - f_best. - Compute the EI using the formula:

EI(x) = (μ(x) - f_best) * Φ(Z) + σ(x) * φ(Z)ifσ(x) > 0, else0. WhereZ = (μ(x) - f_best) / σ(x), andΦ,φare the CDF and PDF of the standard normal distribution. - Select the candidate

xthat maximizesEI(x).

Table 1: Comparison of Common Acquisition Functions

| Function | Formula | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) | EI(x) = (μ - f_best)*Φ(Z) + σ*φ(Z) |

General-purpose optimization |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | UCB(x) = μ(x) + κ * σ(x) |

Explicit exploration/exploitation trade-off via κ |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | PI(x) = Φ((μ(x) - f_best - ξ) / σ(x)) |

Pure exploitation (with tolerance ξ) |

Convergence Criteria

Protocol: The BO loop terminates when one or more criteria are met:

- Iteration Limit: Predefined number of cycles (e.g., 50-100) is reached.

- Performance Plateau: Improvement in

f_bestover the lastNiterations (e.g., N=10) is less than thresholdδ(e.g., 0.5% of target range). - Acquisition Value Threshold: Maximum acquisition function value falls below a minimum (e.g., EI < 0.01), indicating diminishing returns.

Application Protocol: Autonomous Catalyst Discovery

Objective: Maximize catalytic yield (Y) by optimizing two alloy composition variables (A%, B%).

Experimental Setup & Initialization

- Define Search Space:

A%∈ [0, 100],B%∈ [0, 100], withA% + B% ≤ 100. - Generate Initial Dataset: Perform 10 experiments using a Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) design to ensure space-filling coverage.

- Measure Response: Record yield

Yfor each initial composition.

Table 2: Example Initial Dataset (First 5 Points)

| Experiment | A% | B% | Yield Y (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.5 | 70.2 | 45.6 |

| 2 | 85.3 | 8.7 | 22.1 |

| 3 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 65.8 |

| 4 | 5.1 | 30.9 | 33.4 |

| 5 | 60.8 | 35.1 | 72.3 |

Iterative BO Loop Execution

- Standardize composition data and yield values.

- Train GPR model with Matérn 5/2 kernel on current dataset.

- Discretize search space into a 100x100 grid.

- Calculate EI across the entire grid using the protocol in 3.2.

- Select the grid point with the maximum EI as the next experiment.

- Synthesize and test the catalyst at the recommended composition.

- Measure and record the new yield.

- Append the new data point (

A%,B%,Y) to the dataset. - Check Convergence: Stop if 30 iterations completed OR max EI < 0.1% for 5 consecutive runs.

- Report the composition with the highest observed yield.

Data Flow Diagram

Diagram Title: BO Loop Data Flow for Catalyst Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials & Computational Tools for GPR-AL Implementation

| Item / Solution | Function / Role | Example Vendor / Library |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Synthesis Robot | Automates preparation of material/composition variants according to BO suggestions. | Chemspeed, Unchained Labs |

| Automated Characterization Suite | Rapidly measures target properties (e.g., yield, activity, conductivity) for feedback. | Built-in analytics (HP-LC, Raman), Formulatrix |

| BO Software Framework | Provides core algorithms for GPR modeling, acquisition functions, and loop management. | BoTorch (PyTorch), scikit-optimize (scikit-learn), GPyOpt |

| GPR Library | Implements robust Gaussian process regression with various kernels. | GPy, scikit-learn.gaussian_process, GPflow |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Centralized database for tracking all experimental conditions, results, and metadata. | Benchling, Labguru, self-hosted |

| Chemical Precursors & Substrates | High-purity starting materials for synthesis, formatted for automated dispensing. | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI, specific to target material class |

Within the broader thesis on Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) for materials synthesis, this study demonstrates the application of Bayesian optimization to the complex, multi-variable problem of pharmaceutical process development. The synthesis of the target API, a novel kinase inhibitor, presents challenges in yield and purity due to sensitive reaction parameters. Traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) optimization is inefficient for such high-dimensional spaces. This case study details the use of GPR to model the reaction landscape and intelligently select experimental conditions, aiming to maximize yield while controlling critical impurity levels.

Application Notes: GPR-Driven Optimization

Problem Definition

The key reaction is a Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig amination, a critical step in forming the API's core structure. Preliminary screening identified four continuous variables with significant, non-linear effects on yield and the formation of Impurity A (des-fluoro impurity).

Optimization Objectives:

- Maximize reaction yield (Goal: >85%).

- Minimize Impurity A (Goal: <0.15 area% by HPLC).

- Identify a robust operating region.

Gaussian Process Regression Model Setup

- Input Variables (X): Reaction temperature (°C), catalyst loading (mol%), reaction time (hours), and equivalents of base.

- Output/Target Variables (Y): Reaction yield (%) and Impurity A area (%).

- Kernel Function: A Matérn 5/2 kernel was chosen to model potentially rough, non-stationary response surfaces without over-smoothing.

- Acquisition Function: Expected Improvement (EI), balanced to favor both exploration and exploitation.

Experimental Design & Data

An initial space-filling design (Latin Hypercube) of 12 experiments was performed to seed the GPR model. The GPR algorithm then proposed 8 sequential experiments based on the EI acquisition function. Results from all 20 experiments are summarized below.

Table 1: Experimental Data from GPR-Guided Optimization Campaign

| Exp. | Temp. (°C) | Catalyst (mol%) | Time (h) | Base (eq.) | Yield (%) | Impurity A (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80 | 1.0 | 12 | 2.0 | 72.1 | 0.32 |

| 2 | 100 | 2.0 | 18 | 2.5 | 81.5 | 0.41 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 15* | 92 | 1.4 | 15 | 2.2 | 86.7 | 0.11 |

| 16 | 95 | 1.8 | 16 | 2.4 | 84.2 | 0.28 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 20 | 88 | 1.2 | 14 | 2.1 | 85.9 | 0.14 |

*Identified optimal condition.

Table 2: Comparison of Initial Baseline vs. GPR-Optimized Condition

| Condition | Temp. (°C) | Catalyst (mol%) | Time (h) | Base (eq.) | Yield (%) | Impurity A (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (OFAT) | 100 | 2.5 | 24 | 3.0 | 78.3 | 0.52 |

| GPR-Optimized | 92 | 1.4 | 15 | 2.2 | 86.7 | 0.11 |

Experimental Protocols

General Procedure for Buchwald-Hartwig Amination (GPR Experiment)

Materials: See The Scientist's Toolkit (Section 5). Safety: Perform all operations in a well-ventilated fume hood with appropriate PPE.

Procedure:

- Charge: In a nitrogen-flushed glovebox, charge a 10 mL microwave vial with a magnetic stir bar, palladium precatalyst (XPhos Pd G2, 1.4 mol%), and XPhos ligand (1.68 mol%).

- Add Reagents: To the vial, add aryl bromide substrate (1.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), amine coupling partner (1.05 equiv.), and sodium tert-butoxide (2.2 equiv.).

- Solvent Addition: Transfer the vial out of the glovebox. Under a positive nitrogen flow, add anhydrous 1,4-dioxane (4 mL) via syringe.

- Reaction: Seal the vial with a PTFE-lined cap. Place it in a pre-heated aluminum heating block at 92°C and stir vigorously for 15 hours.

- Sampling & Quenching: After cooling to room temperature, transfer a 50 µL aliquot to a 2 mL HPLC vial. Quench this aliquot with 1 mL of 1:1 v/v acetonitrile/water mixture containing 0.1% formic acid.

- Work-up (Scale-up): For isolation, dilute the main reaction mixture with 20 mL of ethyl acetate and wash with 10 mL of water. Separate the layers and back-extract the aqueous layer with 10 mL of ethyl acetate. Combine the organic layers, dry over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Analysis: Analyze the quenched aliquot by UPLC/MS to determine yield (by UV absorbance relative to an internal standard) and impurity profile.

Analytical Method for Yield and Purity Assessment (UPLC-UV/MS)

- Column: C18 reversed-phase (2.1 x 50 mm, 1.7 µm).

- Mobile Phase A: Water with 0.1% formic acid.

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid.

- Gradient: 5% B to 95% B over 3.5 minutes, hold for 1 minute.

- Flow Rate: 0.6 mL/min.

- Detection: UV at 254 nm and ESI-MS.

- Quantification: Yield determined via internal standard (IS) method using a structurally similar, non-interfering compound. Impurity A is reported as area percent relative to the main peak.

Visualizations

GPR Bayesian Optimization Workflow for API Synthesis

Catalytic Cycle and Impurity Formation Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Palladium Precatalyst (XPhos Pd G2) | Air-stable, highly active Pd source for C-N coupling. Pre-defined Pd/XPhos ligand system simplifies screening. |

| XPhos Ligand | Bulky, electron-rich biarylphosphine ligand that promotes reductive elimination and stabilizes the Pd(0) species. |

| Sodium tert-Butoxide (NaOtBu) | Strong, soluble base crucial for deprotonation of the amine nucleophile in the catalytic cycle. Concentration is a critical optimization parameter. |

| Anhydrous 1,4-Dioxane | Common, high-boiling solvent for Pd-catalyzed cross-couplings. Must be anhydrous to prevent base degradation and catalyst deactivation. |

| Internal Standard (for HPLC) | A chemically inert compound added in known quantity before analysis to enable precise quantitative yield determination via relative UV response. |

| UPLC/MS System with C18 Column | Enables rapid, high-resolution analysis of reaction crude mixtures for both conversion (yield) and impurity profiling in a single run. |

Within a broader thesis on Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) for materials synthesis, this case study focuses on the multivariate optimization of polymeric nanoparticle (NP) drug carriers. GPR is a powerful Bayesian machine learning tool ideal for modeling complex, non-linear relationships between synthesis parameters (e.g., polymer concentration, solvent ratio, mixing speed) and critical quality attributes (CQAs) like particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and drug loading efficiency (LE). By treating the synthesis process as a black-box function, GPR can predict optimal formulations with minimal experimentation, guiding researchers toward the design space that simultaneously meets stringent nanomedicine criteria.

Key Quality Attributes: Targets & Data

Successful drug carriers require precise control over physicochemical properties. The following table summarizes target ranges based on current literature for intravenous administration.

Table 1: Target Ranges for Nanoparticle Drug Carriers

| Quality Attribute | Ideal Target Range | Critical Threshold | Justification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic Size | 80 - 150 nm | < 200 nm | Avoids renal clearance (>10 nm) and enables EPR effect (<200 nm). | ||

| Polydispersity Index (PDI) | < 0.2 | < 0.3 | Indicates a monodisperse, homogeneous population for consistent biodistribution. | ||

| Loading Efficiency (LE) | > 80% | > 70% | Maximizes therapeutic payload, minimizes excipient and cost. | ||

| Zeta Potential | ±20 - ±30 mV | > | +30 | mV indicates colloidal stability; neutral or slightly negative reduces non-specific uptake. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Nanoparticle Synthesis via Single-Emulsion Solvent Evaporation

This is a standard method for encapsulating hydrophobic drugs.

I. Materials & Reagent Setup

- Polymer: PLGA (50:50, acid-terminated, MW 10-30 kDa). Dissolve in organic solvent to 20-50 mg/mL.

- Drug: Model hydrophobic drug (e.g., Paclitaxel, Curcumin). Add to polymer solution at 5-20% (w/w, drug:polymer).

- Organic Phase: Dichloromethane (DCM) or ethyl acetate.

- Aqueous Phase: 1-5% (w/v) Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA, MW 30-70 kDa) in DI water.

- Equipment: Probe sonicator, magnetic stirrer, rotary evaporator.

II. Procedure

- Dissolve the polymer and drug completely in the organic solvent (e.g., 2 mL DCM).

- Pour the organic phase into 10-20 mL of the aqueous PVA solution.

- Emulsify using a probe sonicator (70% amplitude, 60 seconds, pulse cycle 5s on/2s off) over an ice bath.

- Immediately transfer the primary emulsion to 50 mL of a 0.1-0.5% PVA solution under rapid magnetic stirring (500 rpm).

- Stir for 3-4 hours at room temperature to allow for complete solvent evaporation and nanoparticle hardening.

- Concentrate and purify nanoparticles by centrifugation (20,000 x g, 20 min, 4°C). Wash pellet 2-3 times with DI water.

- Re-suspend the final nanoparticle pellet in 5 mL PBS or sucrose solution (5% w/v) for lyophilization.

Protocol: Characterization of Size, PDI, and Zeta Potential via DLS

- Dilute 20 µL of the purified nanoparticle suspension in 1 mL of filtered (0.2 µm) DI water or 1 mM KCl.

- Load sample into a disposable folded capillary cell for zeta potential measurement or a clear sizing cuvette.

- Equilibrate at 25°C for 120 seconds in the Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) instrument.

- Perform size/PDI measurement: run minimum 3 sub-runs of 60 seconds each. Report Z-average diameter and PDI.

- For zeta potential: perform a minimum of 3 runs of 10-15 cycles each using the Smoluchowski model.

Protocol: Determination of Drug Loading and Encapsulation Efficiency

- Lyophilize a known volume (e.g., 1 mL) of purified nanoparticle suspension to obtain a precise weight of solid NP mass (W_np).

- Dissolve 1-2 mg of the dried nanoparticles in 1 mL of a compatible organic solvent (e.g., DMSO for PLGA/PTX).

- Sonicate for 5 minutes and vortex thoroughly to ensure complete dissolution and drug release.

- Dilute the solution appropriately and analyze drug concentration using a pre-validated HPLC-UV or fluorescence method against a standard calibration curve.

- Calculate:

- Drug Loading (DL %) = (Weight of drug in nanoparticles / Total weight of nanoparticles) x 100.

- Loading Efficiency (LE %) = (Actual drug loaded / Theoretical initial drug amount) x 100.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Nanoparticle Synthesis & Characterization

| Material/Reagent | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | Biodegradable, FDA-approved copolymer forming the nanoparticle matrix. Ratio (LA:GA) & MW control degradation rate. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | A surfactant that stabilizes the oil-water emulsion during formation, preventing nanoparticle aggregation. |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | A volatile organic solvent that dissolves polymers/drugs and is easily evaporated to solidify nanoparticles. |

| Dialysis Tubing (MWCO 10-14 kDa) | Used for alternative purification to remove free drug, surfactant, and solvents via diffusion. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | Core instrument for measuring hydrodynamic particle size distribution and PDI. |

| HPLC System with UV/Vis Detector | Gold-standard for quantifying drug concentration to determine loading and encapsulation efficiency. |

| Lyophilizer | Freeze-dries nanoparticle suspensions to a stable powder for long-term storage and accurate weighing. |

GPR-Driven Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

GPR-Guided Nanoparticle Optimization Loop

Single-Emulsion Nanoparticle Formation Pathway

Data Integration for GPR Modeling

Table 3: Example Experimental Dataset for GPR Training

| Run | Polymer Conc. (mg/mL) | Drug Load (% w/w) | Sonication Time (s) | PVA % (w/v) | Size (nm) | PDI | LE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | 5 | 60 | 1.0 | 165.2 | 0.21 | 65.1 |

| 2 | 50 | 5 | 90 | 2.0 | 128.5 | 0.15 | 78.4 |

| 3 | 25 | 15 | 90 | 2.0 | 182.7 | 0.28 | 85.2 |

| 4 | 50 | 15 | 60 | 1.0 | 145.3 | 0.19 | 72.8 |

| 5 | 37.5 | 10 | 75 | 1.5 | 151.8 | 0.17 | 81.5 |

| GPR Prediction | 42 | 12 | 82 | 1.8 | 135 | 0.12 | 88 |

The GPR model, trained on data like above, predicts an optimal formulation (bottom row) that improves all CQAs simultaneously.

Within a thesis on Gaussian Process (GP) regression for materials synthesis research, the core challenge is to build predictive models that map synthesis parameters (e.g., temperature, precursor concentration, time) to material properties (e.g., bandgap, porosity, conductivity). This requires software tools that are flexible, scalable, and integrated with optimization routines. GPyTorch, scikit-learn, and BoTorch form a complementary toolkit for this pipeline, enabling rapid prototyping (scikit-learn), custom, high-performance GP modeling (GPyTorch), and Bayesian optimization for autonomous synthesis guidance (BoTorch).

Table 1: Comparison of Key GP Implementation Tools

| Feature | scikit-learn GaussianProcessRegressor |

GPyTorch | BoTorch |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | General-purpose machine learning, including basic GPs. | Flexible, GPU-accelerated GP modeling via PyTorch. | Bayesian optimization & research built on GPyTorch. |

| Kernel Flexibility | Moderate. Predefined kernels, limited composition. | High. Easy custom kernel creation via PyTorch modules. | Very High. Inherits GPyTorch flexibility, adds acquisition kernels. |

| Scalability | Low to Moderate. Exact inference O(n³). | High. Supports variational inference & inducing points for large n. | High. Built for large-scale optimization loops. |

| Optimization Focus | Point estimates via log marginal likelihood. | Gradient-based (Adam, etc.) on marginal likelihood. | Gradient-based optimization of acquisition functions. |

| Best For (Materials Context) | Quick baseline models on small datasets (<1000 points). | Complex, non-standard GP models on larger experimental datasets. | Actively designing the next synthesis experiment via acquisition functions. |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity, integration with preprocessing. | Performance, customization, research-oriented. | State-of-the-art Bayesian optimization loops. |

| Latest Stable Version (as of 2024) | 1.4.0 | 1.11 | 0.9.0 |

Experimental Protocol: A Bayesian Optimization Cycle for Catalyst Synthesis

This protocol details one iterative cycle of using these tools to optimize a target material property.

Objective: Maximize the photocatalytic hydrogen evolution rate (HER) of a metal-organic framework (MOF) by tuning three synthesis parameters: ligand molarity (0.1-1.0 M), modulation acid concentration (0-100 mM), and solvothermal reaction time (12-72 h).

Step 1: Initial Data Collection & Preprocessing (scikit-learn)

- Procedure:

- Perform a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube) for 10 initial synthesis experiments.

- Characterize the resulting MOF samples for HER (μmol h⁻¹ g⁻¹).

- Assemble dataset

X(10x3 matrix of parameters) andy(10x1 vector of HER). - Use

sklearn.preprocessing.StandardScalerto standardizeXto zero mean and unit variance. Scaleysimilarly.

- Code Note:

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

Step 2: Construct a Custom GP Model (GPyTorch)

- Procedure:

- Define a GP model combining a

ScaleKernelwith aMaternKernel(nu=2.5) for smooth function approximation and aLinearKernelto capture potential linear trends. - Use an

ExactGPLikelihood(for small initial data) and aZeroMeanprior. - Train the model using Type-II MLE: Use Adam optimizer (lr=0.1) for 200 iterations to minimize the negative marginal log-likelihood (

mll).

- Define a GP model combining a

- Code Note:

import gpytorch; model = ExactGPModel(train_x, train_y, likelihood)

Step 3: Define & Optimize the Acquisition Function (BoTorch)

- Procedure:

- Using the trained GPyTorch model, define the Expected Improvement (

qEI) acquisition function to target the 90th percentile of observed HER as the incumbent. - Generate a set of 5000 random candidate points within the bounded synthesis parameter space.

- Optimize the acquisition function: Use sequential least-squares programming (SLSQP) from a multi-start initialization (10 random starts) to find the candidate point that maximizes

qEI.

- Using the trained GPyTorch model, define the Expected Improvement (

- Code Note:

from botorch.acquisition import qExpectedImprovement; from botorch.optim import optimize_acqf

Step 4: Validation & Iteration

- Procedure: Execute the synthesis and characterization protocol for the top recommended candidate from Step 3. Add this new data point to the training set. The cycle (Steps 1-4) repeats until a performance target is met or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Visualization of the Bayesian Optimization Workflow

Title: Bayesian Optimization Cycle for Materials Synthesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Parallelized MOF Synthesis & Testing (Example)

| Item | Function in Protocol | Example Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salt Precursor | Provides the metal clusters (nodes) for MOF formation. | Zirconium(IV) chloride (ZrCl₄), >99.5% purity. |

| Organic Ligand | Forms the linking structure of the MOF. | 2-Aminoterephthalic acid, 98% (for UiO-66-NH₂). |

| Modulation Acid | Controls crystallization kinetics & defect engineering. | Acetic acid, glacial, ACS reagent. |

| Polar Aprotic Solvent | Reaction medium for solvothermal synthesis. | N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), anhydrous. |

| Washing Solvents | Removes unreacted precursors from porous MOF. | Methanol (ACS grade) & Acetonitrile. |

| Electron Donor | Essential component for photocatalytic HER testing. | Triethanolamine (TEOA), 99%. |

| Co-catalyst | Enhances charge separation for HER. | 3 wt% Platinum nanoparticles (3 nm avg.). |

| Sealed Reactor Vials | Enables high-throughput, parallel solvothermal synthesis. | 20 mL glass vials with PTFE-lined caps. |

Beyond the Basics: Troubleshooting and Advanced Optimization of GPR Models

This document serves as an application note for a thesis investigating the application of Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to optimize the synthesis of novel perovskite materials for photovoltaics. A core challenge is building predictive GPR models from inherently noisy and limited high-throughput experimental data. Mischaracterizing model fit—through overfitting or underfitting—can derive false structure-property relationships, leading to costly misdirection in synthesis campaigns. These protocols address the identification, prevention, and remediation of these pitfalls.

The following table summarizes key metrics for diagnosing model fit, critical for evaluating GPR models in materials synthesis.

Table 1: Diagnostic Metrics for Model Fit Assessment

| Metric | Formula | Ideal Value (for Good Fit) | Indicates Overfitting | Indicates Underfitting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | MAE = (1/n) * Σ|yi - ŷi| |

Low on unseen data | Very low on training, high on test | High on both training and test |

| Root Mean Sq. Error (RMSE) | RMSE = √[(1/n) * Σ(yi - ŷi)²] |

Low on unseen data | Very low on training, high on test | High on both training and test |

| Coefficient of Determination (R²) | R² = 1 - [Σ(yi - ŷi)² / Σ(y_i - ȳ)²] |

Close to 1 on test data | ~1 on training, <<1 on test | Low on both training and test |

| NLL (Negative Log-Likelihood) | -log p(y|X,θ) |

Minimized | Very low (overconfident) | High (poor predictive distribution) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Generating a Robust Train-Validation-Test Split for Noisy Materials Data

Objective: To partition experimental datasets to reliably detect overfitting/underfitting. Materials: High-throughput experimental dataset (e.g., perovskite synthesis parameters: precursor ratios, annealing temps, resulting power conversion efficiency (PCE)). Procedure:

- Data Curation: Remove clear measurement errors (e.g., PCE > theoretical limit). Document all removals.

- Stratified Splitting: If data is clustered (e.g., by chemical family), use stratified sampling (

scikit-learnStratifiedShuffleSplit) to maintain class distribution across splits. - Split Ratios: For typical dataset sizes (<1000 points), use 70%/15%/15% for Training/Validation/Test sets. For very small datasets (<100), consider nested cross-validation.

- Noise Acknowledgment: Report the estimated experimental standard deviation for key measurements (e.g., PCE ± 0.5%) alongside split indices.

Protocol 3.2: Kernel Selection and Hyperparameter Tuning for GPR

Objective: To choose a GPR kernel that captures the underlying materials science trends without fitting noise. Materials: Training dataset, validation dataset, GPR software library (e.g., GPy, scikit-learn, GPflow). Procedure:

- Start Simple: Initialize with a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel. This is the default for modeling smooth, continuous variations (e.g., property change with temperature).

- Add Noise Model: Explicitly add a

WhiteKernelto model experimental noise. Its initial variance can be set to the square of the known measurement error. - Optimize Hyperparameters: Maximize the log-marginal likelihood on the training set.

- Validate Complexity: Compare performance (RMSE, NLL) on the validation set. If performance is poor, consider:

- For suspected underfitting: Add a

Maternkernel (less smooth than RBF) or combine RBF with aLinearkernel to capture trends. - For suspected overfitting: Increase the

alphaparameter (homoscedastic noise) or constrain the bounds of theWhiteKernel.

- For suspected underfitting: Add a

Protocol 3.3: Active Learning Loop to Mitigate Data Scarcity and Noise

Objective: To iteratively select the most informative next experiment, improving model efficiency and robustness. Materials: Initial GPR model, pool of candidate synthesis conditions, high-throughput synthesis capability. Procedure:

- Train Initial Model: Fit a GPR model with a proper noise kernel to the initial dataset (Protocol 3.2).

- Query Point Selection: Calculate the predictive variance (uncertainty) for all candidates in the unexperimented pool.

- Acquisition Function: Select the next synthesis condition using the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) acquisition function: