A Strategic Guide to Choosing Your NGS Method for Microbiome Analysis

Selecting the optimal Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) method is critical for successful microbiome research and clinical application.

A Strategic Guide to Choosing Your NGS Method for Microbiome Analysis

Abstract

Selecting the optimal Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) method is critical for successful microbiome research and clinical application. This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a structured framework for navigating the complex landscape of NGS methodologies. We cover foundational principles, compare the applications and performance of 16S rRNA sequencing, shotgun metagenomics (mNGS), and targeted NGS (tNGS), and delve into the emerging role of long-read sequencing. The article also addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies, supported by recent comparative data on diagnostic accuracy, turnaround time, and cost-effectiveness to empower informed, project-specific decision-making.

Understanding the Core NGS Technologies in Microbiome Science

Defining the Microbiome and the Need for Culture-Independent NGS

The human microbiome, comprising trillions of microorganisms inhabiting various body sites, plays crucial roles in health and disease. Traditional microbiology, reliant on culturing techniques, fails to characterize the vast majority of microbial diversity. This whitepaper defines the microbiome and establishes why culture-independent next-generation sequencing (NGS) is indispensable for its comprehensive analysis. We compare the fundamental NGS methodologies—16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics—detailing their experimental protocols, analytical pipelines, and applications. Framed within the broader context of selecting appropriate NGS methods for research, this guide provides a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate the technical landscape of microbiome science.

The term microbiome refers to the complex community of microorganisms—including bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, and other microbes—inhabiting a particular environment, along with their structural elements, genomes, and surrounding environmental conditions [1]. In humans, these microbiomes are essential for physiological processes, including nutrient metabolism, immune system modulation, and protection against pathogens. Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in this microbial community, has been linked to a wide array of diseases, from inflammatory bowel disease and diabetes to cancer and neurological disorders [2] [3].

For over a century, the study of microbes was dominated by culture-dependent techniques, pioneered by Robert Koch. While foundational, these methods are inherently biased, as they only capture microorganisms that can proliferate under specific laboratory conditions [4]. This approach has led to a significant knowledge gap known as the "great plate count anomaly," which describes the discrepancy where microscopic counts from environmental samples are orders of magnitude higher than the number of colonies that can be cultured on artificial media. It is estimated that only 0.01–1% of environmental microorganisms are culturable, leaving the vast majority of microbial diversity unexplored [4]. This uncultured majority is often referred to as microbial "dark matter" [1]. Causes for this anomaly include the lack of essential nutrients in growth media, dependence on symbiotic relationships with other species, and mismatches between laboratory growth conditions and an organism's natural habitat [4].

The Revolution of Culture-Independent NGS

The advent of culture-independent NGS has revolutionized microbial ecology by allowing researchers to sequence genetic material directly from environmental or clinical samples, bypassing the need for cultivation [3]. This paradigm shift has enabled the comprehensive sampling of all genes from all organisms present in a complex sample, providing unprecedented insights into the taxonomic composition and functional potential of microbiomes [5].

Two primary NGS methodologies are employed for microbiome analysis:

- Targeted Amplicon Sequencing (Metataxonomics): This approach involves PCR amplification and sequencing of specific phylogenetic marker genes, most commonly the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene [2] [1].

- Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing (Metagenomics): This method involves randomly shearing and sequencing all DNA fragments from a sample, enabling reconstruction of whole-genome sequences and functional profiling [5] [1].

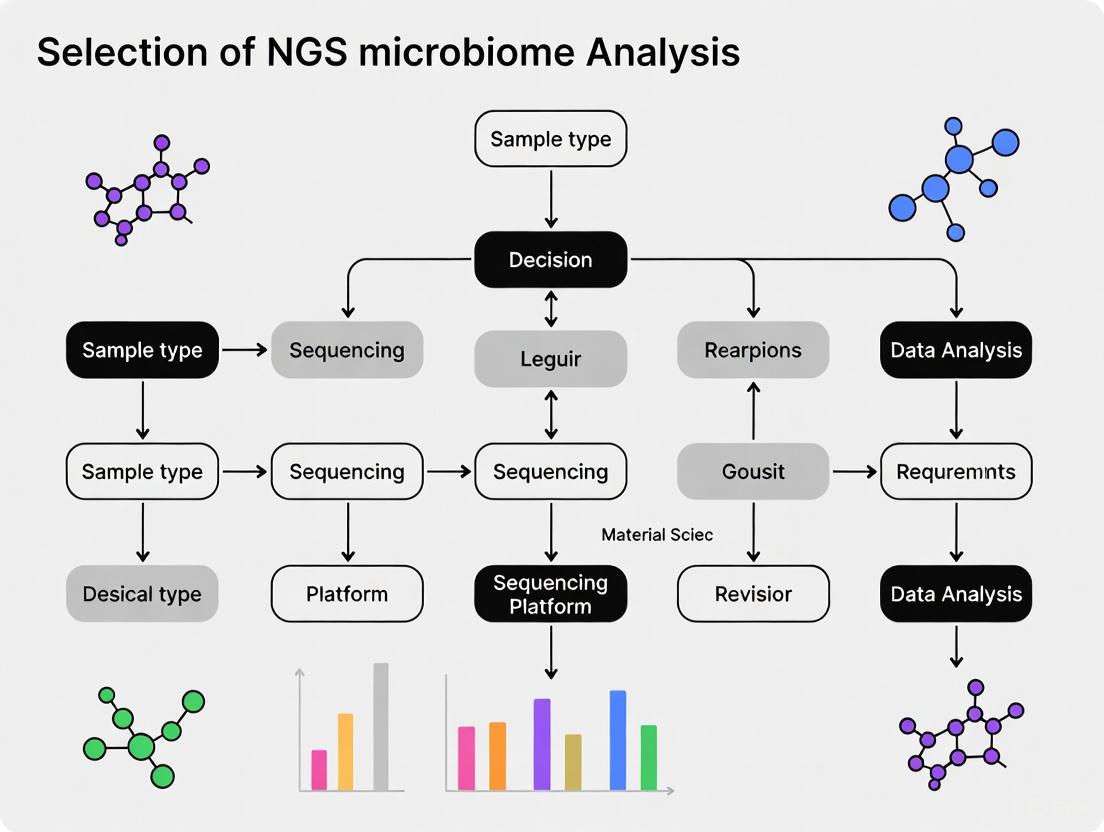

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making workflow for selecting an NGS methodology for microbiome analysis.

Comparative Analysis of NGS Methodologies

Choosing between 16S rRNA sequencing and shotgun metagenomics is a critical decision that depends on research objectives, budget, and desired analytical depth. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each method.

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison: 16S rRNA vs. Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

| Feature | 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Target | Specific hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene [2] | All genomic DNA in the sample [5] |

| Taxonomic Scope | Primarily Bacteria and Archaea [2] | All domains (Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, Fungi) and plasmids [2] [1] |

| Typical Taxonomic Resolution | Genus-level (species-level with full-length sequencing) [6] [2] | Species-level and strain-level resolution [2] [7] |

| Functional Insight | Indirectly inferred from taxonomy [7] | Direct assessment of functional genes and pathways [5] [7] |

| Relative Cost | Lower cost per sample [7] | Higher cost per sample [5] [3] |

| Computational Demand | Lower | High (data-intensive assembly and binning) [3] [1] |

| Primary Applications | Microbial community profiling, diversity studies, population-level surveys [1] | Functional potential discovery, strain tracking, gene cataloging, MAG recovery [5] [4] |

Beyond this foundational comparison, the performance of each method has been quantitatively evaluated in direct comparative studies. Key findings on detection power and abundance correlation are summarized below.

Table 2: Empirical Performance Metrics from Comparative Studies

| Performance Metric | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Power (Genera) | Identifies a subset of the community [7] | Detects more, less abundant taxa with sufficient reads (>500,000) [7] | In one study, shotgun sequencing identified 152 significant changes between conditions that 16S missed [7]. |

| Abundance Correlation | Good agreement for common taxa (avg. r = 0.69) [7] | Good agreement for common taxa [7] | Discrepancies often due to genera being near the detection limit of 16S sequencing [7]. |

| Error Rate | Low (Illumina: <0.1%) [6] | Low (Illumina: <0.1%) [6] | Higher error rates historically associated with long-read technologies (e.g., ONT: 5-15%), though improving [6]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Best Practices

Workflow for 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

The standard protocol for 16S rRNA sequencing involves sample collection, DNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatics analysis [6] [1].

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: Samples are collected (e.g., stool, saliva, skin swab) and immediately frozen, typically at -80°C. DNA is extracted using specialized kits, with the choice of kit significantly impacting yield and community representation [6]. DNA quality and concentration are assessed using spectrophotometry and fluorometry [6].

- Library Preparation: The 16S rRNA gene is amplified via PCR using primers that bind to conserved regions and flank hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4). Barcodes and sequencing adapters are added in a subsequent PCR step to allow for sample multiplexing [6]. The use of a positive control, such as a synthetic DNA standard, is recommended to monitor library construction [6].

- Sequencing: Amplified libraries are pooled and sequenced on a high-throughput platform like the Illumina NextSeq to generate paired-end reads (e.g., 2x300 bp) [6].

- Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Quality Control & Denoising: Raw reads are processed for quality using tools like FastQC and MultiQC. Primer sequences are trimmed, and low-quality reads are filtered. Denoising algorithms like DADA2 are used to correct errors and infer exact Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) [6] [2].

- Taxonomic Assignment: ASVs are classified by comparison to reference databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes) to assign taxonomic identities from phylum to genus or species level [6] [2].

- Downstream Analysis: Diversity metrics (alpha and beta diversity) are calculated using packages like

phyloseqandveganin R. Differential abundance analysis can be performed with tools like ANCOM-BC [6].

Workflow for Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

Shotgun metagenomics provides a more comprehensive but complex alternative [5] [1].

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: This step is similar but often requires higher-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA to facilitate robust library preparation and assembly [1].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: DNA is randomly fragmented (sheared), and adapters are ligated without target-specific amplification. Libraries are sequenced on platforms like the Illumina NovaSeq for high depth or long-read platforms like PacBio and Oxford Nanopore for enhanced resolution [6] [8].

- Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Quality Control and Host Depletion: Reads are quality-filtered, and reads originating from the host (e.g., human) are removed.

- Taxonomic Profiling: Reads can be directly aligned to reference databases (e.g., RefSeq) using tools like the DRAGEN Metagenomics pipeline for taxonomic classification [5] [2].

- Assembly and Binning: High-quality reads are assembled into contigs, which are then grouped into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) representing individual microbial populations [4] [8].

- Functional Annotation: Genes are predicted from contigs or MAGs and annotated against functional databases (e.g., KEGG, COG) to determine the metabolic capabilities of the community [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful microbiome sequencing relies on a suite of specialized reagents, kits, and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Microbiome NGS

| Item | Function | Example Products / Tools |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality, inhibitor-free microbial DNA from complex samples. | Sputum DNA Isolation Kit (Norgen Biotek) [6] |

| 16S Library Prep Kit | Amplification and barcoding of target hypervariable regions for multiplexed sequencing. | QIAseq 16S/ITS Region Panel (Qiagen) [6] |

| Shotgun Library Prep Kit | Fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification of total genomic DNA for untargeted sequencing. | Illumina DNA Prep kits [5] |

| Long-Read Library Prep Kit | Preparation of libraries for long-read sequencing platforms. | ONT 16S Barcoding Kit (Oxford Nanopore) [6] |

| Positive Control | Synthetic DNA standard to monitor efficiency and bias in library preparation and sequencing. | QIAseq 16S/ITS Smart Control (Qiagen) [6] |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Automated workflows for processing raw data into taxonomic and functional profiles. | nf-core/ampliseq [6], DRAGEN Metagenomics [5], EPI2ME [6] |

| Reference Databases | Curated collections of genomic or gene sequences for taxonomic and functional classification. | SILVA [6], RefSeq [2], GenBank [2] |

The definition and study of the microbiome are inextricably linked to the development of culture-independent NGS technologies. While 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing remains a powerful, cost-effective tool for large-scale taxonomic surveys, shotgun metagenomics provides a superior and comprehensive view of the microbiome's taxonomic and functional landscape. The choice between them should be dictated by the specific research question, with 16S suitable for broad ecological studies and shotgun metagenomics essential for mechanistic insights and discovering uncultured microorganisms.

The field continues to evolve rapidly, driven by technological advancements. Long-read sequencing from Oxford Nanopore and PacBio is overcoming previous limitations in accuracy, enabling full-length 16S sequencing and more complete metagenome assembly for superior resolution [6] [8]. Furthermore, the development of integrated, user-friendly bioinformatics platforms is making sophisticated data analysis more accessible, promoting reproducibility and collaboration [9]. As the global microbiome sequencing market expands, projected to reach $3.7 billion by 2029 [10], these innovations will undoubtedly deepen our understanding of microbial communities and unlock new diagnostic and therapeutic avenues in human health and beyond.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized microbiome research by enabling comprehensive, culture-independent analysis of microbial communities [11] [2]. The choice of sequencing method profoundly influences the depth, breadth, and clinical applicability of microbiome data, making method selection a critical first step in research design. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the three principal NGS approaches used in microbiome analysis: 16S rRNA gene sequencing, shotgun metagenomic sequencing (mNGS), and targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS). Framed within the context of how to choose an NGS method for microbiome research, this document synthesizes current methodologies, performance characteristics, and practical considerations to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge needed to align their technical approach with specific research objectives.

Core NGS Methodologies in Microbiome Research

16S Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) Gene Sequencing

The 16S rRNA gene is a cornerstone of microbial phylogenetics and taxonomy. This ~1500 bp gene contains nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) interspersed with conserved regions [11] [2]. The conserved regions allow for the design of universal PCR primers, while the hypervariable regions provide the sequence diversity necessary for taxonomic classification [3].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow:

- DNA Extraction: Microbial DNA is extracted from samples (e.g., stool, saliva, skin swabs). The extraction method, including the use of bead-beating for robust cell lysis, can significantly impact the microbial profile obtained [12] [13].

- PCR Amplification: Specific hypervariable regions (e.g., V1-V2, V3-V4, V4) are amplified using universal primers targeting the flanking conserved regions [11] [12]. The selection of the hypervariable region is a critical consideration, as it influences taxonomic resolution and can introduce biases; for instance, the V4 region may perform poorly for species-level classification compared to the V1-V3 region or full-length sequencing [12] [14].

- Library Preparation: Amplified products (amplicons) are prepared for sequencing with the addition of platform-specific adapters and sample barcodes (indexes) to enable multiplexing [12].

- Sequencing: Typically performed on Illumina platforms (e.g., MiSeq) [12] [15].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Filtering: Removal of low-quality reads, adapters, and chimeric sequences [12] [2].

- Clustering/Denoising: Sequences are clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) based on a sequence similarity threshold (e.g., 97% for species-level) or denoised into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) [11] [2].

- Taxonomic Assignment: OTUs/ASVs are classified by comparison to reference databases such as SILVA, Greengenes, or the RDP database [2].

Figure 1: 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Workflow. The process involves wet lab procedures from sample to sequencing, followed by bioinformatic analysis for taxonomic classification and community profiling.

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing (mNGS)

Shotgun metagenomics moves beyond a single gene to sequence the entire complement of DNA extracted from a microbial community [5] [3]. This approach allows for simultaneous assessment of taxonomic composition and the functional potential of the microbiome.

Experimental Protocol and Workflow:

- DNA Extraction: Similar to 16S, but with potential use of host DNA depletion kits (e.g., MolYsis) for samples with high host contamination, such as bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) [16].

- Library Preparation: Total DNA is randomly fragmented (sheared), and adapters are ligated without target-specific PCR amplification. This creates a library representing all genomic material in the sample [5] [2].

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Requires deeper sequencing (millions to billions of reads) to achieve adequate coverage of complex communities. Platforms like Illumina NovaSeq or BGISEQ are commonly used [16].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Host Depletion: Reads aligning to a host reference genome (e.g., hg38) are removed [16].

- Taxonomic Profiling: Non-host reads are aligned to comprehensive genomic databases (e.g., RefSeq, GenBank) to identify microorganisms from all domains of life (bacteria, archaea, viruses, fungi) and achieve species- or strain-level resolution [16] [2].

- Functional Profiling: Reads are assembled into contigs or mapped to functional databases (e.g., KEGG, COG) to identify genes and metabolic pathways [5].

Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing (tNGS)

tNGS is a hypothesis-driven approach that uses targeted enrichment techniques to sequence specific genomic regions or a pre-defined set of pathogens. It bridges the gap between 16S and shotgun mNGS [16] [17]. Two primary enrichment methods are used:

- Amplification-based tNGS: Utilizes multiple pairs of primers in a multiplex PCR to amplify targeted pathogen sequences [17].

- Capture-based tNGS: Uses labeled oligonucleotide probes (baits) to hybridize and capture genomic regions of interest from a total DNA library [17].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow (Amplification-based):

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: DNA and/or RNA can be co-extracted. RNA is reverse-transcribed to cDNA [16] [17].

- Target Enrichment: For amplification-based tNGS, a multiplex PCR with dozens to hundreds of pathogen-specific primers is performed to enrich target sequences [17].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: The amplified products are prepared for sequencing, often requiring fewer sequencing reads than mNGS [16] [17].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Processed reads are aligned to a curated database of target pathogens to determine presence and abundance [16] [17].

Comparative Analysis of NGS Approaches

The choice between 16S, shotgun mNGS, and tNGS involves trade-offs between resolution, scope, cost, and analytical complexity. The tables below summarize key comparative metrics and recent clinical performance data.

Table 1: Technical and Practical Comparison of Core NGS Methods

| Feature | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics (mNGS) | Targeted NGS (tNGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target | 16S rRNA gene hypervariable regions | Entire microbial DNA | Pre-defined pathogens/genomic regions |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus-level, limited species/strain [2] | Species- and strain-level possible [2] | Species- and strain-level [16] |

| Scope of Detection | Bacteria and Archaea | All domains (Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, Fungi, Parasites) [2] | Customizable panel (e.g., bacteria, viruses, fungi) [16] [17] |

| Functional Insights | Inferred from taxonomy | Direct assessment of genes and pathways [5] | Limited to targeted genes (e.g., AMR/virulence factors) [17] |

| Cost | Low | High | Moderate [17] |

| Turnaround Time | Shorter | Longer (~20 hours) [17] | Shorter than mNGS [17] |

| Bioinformatic Complexity | Moderate | High ("big data" challenges) [11] | Lower (simplified analysis) |

| Human Host Read Interference | Low (due to targeted amplification) | High (requires depletion steps) [16] | Low (enrichment reduces host background) [16] |

| Ideal Application | Microbial community profiling, diversity studies | Discovering novel organisms, functional metagenomics | Clinical diagnostics, pathogen detection, AMR profiling [16] [17] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison from Recent Clinical Studies (2024-2025)

| Study Context | mNGS Performance | tNGS Performance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 85 BALF specimens [16] | Detected 55 species. Similar performance for bacteria/fungi. | Detected 49 species. Higher detection rate for DNA viruses (e.g., HHV-4, -5, -6, -7). | Overall concordance was 86.75%. tNGS superior for DNA virus detection. |

| 205 LRTI patients [17] | Identified 80 species. High cost (\$840) and long TAT (20h). | Capture-based: 71 species, 93.17% accuracy.Amplification-based: 65 species, lower sensitivity for some bacteria. | Capture-based tNGS recommended for routine diagnostics; mNGS for rare pathogens; amplification-based for resource-limited settings. |

Figure 2: NGS Method Selection Decision Framework. A flowchart to guide the choice of NGS method based on research goals, required resolution, and practical constraints.

Successful microbiome research relies on a suite of carefully selected reagents, kits, and bioinformatic resources.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Resources

| Item | Function | Example Products/Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Host DNA Depletion Kit | Reduces human host background in samples rich in human cells (e.g., BALF, tissue). | MolYsis Basic5 [16] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Isolates total genomic DNA (and RNA) from complex samples. | DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) [12], Isolate II Genomic DNA Kit (Bioline) [15] |

| 16S rRNA PCR Primers | Amplifies specific hypervariable regions for 16S sequencing. | 27Fmod/338R (V1-V2) [12], 341F/805R (V3-V4) [12] |

| Library Prep Kit | Prepares amplicon or fragmented DNA for NGS sequencing. | NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit [15] |

| tNGS Enrichment Kit | Enriches for specific pathogen sequences via multiplex PCR or probe capture. | Respiratory Pathogen Detection Kit (KingCreate) [17] |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Processes raw sequencing data for quality control, taxonomic assignment, and diversity analysis. | QIIME2 [12] [15], DRAGEN Metagenomics [5] |

| Reference Databases | Essential for taxonomic classification and functional annotation. | Greengenes [12], SILVA [2], RefSeq [16] [2] |

The landscape of NGS-based microbiome analysis offers a powerful suite of tools, each with distinct strengths and optimal applications. 16S rRNA sequencing remains a cost-effective method for high-throughput microbial community profiling and diversity analysis. Shotgun metagenomics provides the most comprehensive view, enabling functional insights and high-resolution taxonomic assignment across all domains of life, albeit at a higher cost and computational burden. Targeted NGS is emerging as a robust, sensitive, and efficient solution for clinical diagnostics and specific hypothesis testing.

The decision on which methodology to employ should be guided by a clear alignment between the technical capabilities of each platform and the primary research question, whether it is broad ecological discovery, functional characterization, or precise pathogen detection. As databases expand and workflows become more standardized, the integration of these NGS approaches will continue to deepen our understanding of the microbiome's role in health and disease and advance drug development.

The choice of DNA sequencing technology is a foundational decision in microbiome research, directly impacting the resolution, accuracy, and depth of microbial community analysis. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies are broadly categorized into short-read and long-read platforms, each with distinct technical principles and performance characteristics [2] [18]. Short-read sequencing, dominated by Illumina platforms, generates massive volumes of reads typically 50-600 bases in length, offering high per-base accuracy at a low cost [19] [20]. Conversely, long-read sequencing, represented by Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), produces reads that can span thousands to tens of thousands of bases, which simplifies genome assembly and resolves complex genomic regions [21] [20].

The selection between these methodologies is crucial and must be aligned with the specific research objectives—whether the goal is to broadly profile microbial diversity, reconstruct whole genomes from complex samples, or understand functional potential [22]. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these platforms, framed within the context of choosing an NGS method for microbiome analysis, to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the information needed to design robust and informative microbiome studies.

Technology Comparison: Performance and Characteristics

The performance of short-read and long-read sequencing technologies differs across several key metrics that are critical for experimental design in microbiome research.

Sequencing Performance Metrics

| Performance Metric | Short-Read Sequencing (e.g., Illumina) | Long-Read Sequencing (PacBio) | Long-Read Sequencing (ONT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Read Length | 35–600 bases [18] [19] [20] | Several kilobases to >10 kb [23] [20] | Several kilobases to 10s of kb [21] [20] |

| Per-Base Raw Accuracy | >99.9% [19] | >99.9% (HiFi mode) [23] | ~99% (with latest R10.4.1 flow cells) [23] |

| Primary Advantage | High throughput, low per-base cost, high accuracy [2] [19] | High accuracy for long reads, excellent for assembly [24] [20] | Very long reads, fast turnaround, portability [19] [20] |

| Primary Limitation | Limited resolution in repetitive regions, fragmented assemblies [19] [20] | Higher DNA input requirements, higher cost [24] [20] | Historically higher error rate, though improving [23] [19] |

| Ideal Microbiome Application | High-density population profiling, 16S rRNA amplicon studies [2] [22] | High-quality metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) recovery [21] [24] | Rapid pathogen identification, full-length 16S sequencing, complex MAGs [23] [19] |

A Researcher's Guide to Sequencing Method Selection

Choosing the right sequencing method depends on the research question. The table below outlines the optimal technologies for common microbiome research goals.

| Research Goal | Recommended Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Diversity & Composition (Genus Level) | 16S Amplicon Sequencing (Short-read) [22] | Cost-effective for large sample sets, provides robust genus-level taxonomy [2] [22]. |

| Microbial Diversity & Composition (Species Level) | Full-Length 16S Amplicon Sequencing (Long-read) [23] [20] | Full-length 16S gene sequencing provides superior species-level resolution [23]. |

| Functional Potential (Gene Content) | Shotgun Metagenomics (Short-read or Long-read) [22] | Profiles all genes in a community. Short-read is cost-effective; long-read provides better genomic context [24] [20]. |

| Recovery of High-Quality Genomes (MAGs) | Shotgun Metagenomics (Long-read preferred) [21] [24] | Long reads span repetitive regions, enabling complete, uncontaminated genome assemblies [21]. |

| Rapid, On-Site Pathogen Detection | Shotgun Metagenomics (ONT) [19] [20] | Nanopore's portability and fast turnaround enable real-time analysis in field or clinical settings [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Microbiome Sequencing

Standardized protocols are essential for generating reproducible and reliable microbiome data. The following workflows are widely adopted in the field.

Workflow for 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

This protocol is used for taxonomic profiling of bacterial and archaeal communities [2].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Collect sample (e.g., soil, feces, water) using sterile techniques and immediately preserve it. Flash-freezing at -80°C or using a commercial microbiome preservation buffer is critical to maintain microbial composition integrity [25].

- DNA Extraction: Extract total genomic DNA using a kit designed for microbial lysis (e.g., Zymo Research Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep kit). This step often combines chemical and mechanical lysis to ensure efficient recovery from tough-to-lyse microorganisms like Gram-positive bacteria [23] [25].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene (e.g., V3-V4 for gut and general samples, V4 for environmental samples) using universal primers [23] [22]. The PCR conditions typically involve 25-30 cycles of denaturation (e.g., 95°C for 30s), annealing (e.g., 57°C for 30s), and extension (e.g., 72°C for 60s) [23].

- Library Preparation: Purify the PCR amplicons and ligate sample-specific barcodes (indices) to allow for multiplexing of multiple samples in a single sequencing run [23] [25].

- Sequencing: Pool the barcoded libraries and sequence on a short-read platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq or NovaSeq) to a depth of 50,000-100,000 reads per sample for complex communities [23] [2].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process raw sequences through a pipeline (e.g., QIIME 2, mothur) for quality filtering, chimera removal, and clustering into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) for taxonomic assignment and diversity analysis [2].

Workflow for Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

This protocol sequences all DNA in a sample, enabling functional profiling and genome reconstruction [22].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Identical to the 16S protocol, proper preservation is key [25].

- DNA Extraction: Extract high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA. For long-read sequencing, this is particularly critical as the protocol requires long, intact DNA fragments to leverage its advantages [20].

- Library Preparation (Platform-Specific):

- For Illumina (Short-read): Fragment the purified DNA mechanically, then repair ends, ligate adapters, and perform size selection [2] [25].

- For PacBio (Long-read): For HiFi sequencing, create SMRTbell libraries by ligating hairpin adapters to double-stranded DNA, creating a circular template. No PCR amplification is needed [23] [8].

- For ONT (Long-read): Use a native barcoding kit (e.g., SQK-NBD109) to ligate barcodes directly to the DNA fragments. The library preparation is often faster and requires no PCR [23] [20].

- Sequencing: Sequence the library on the chosen platform. Required depth varies significantly: 20-100 Gbp of data may be needed per sample for deep metagenomic analysis, especially with complex samples like soil [21] [24].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: This is a complex, multi-step process. For long-read data, specialized workflows like

mmlong2have been developed for complex environmental samples. The process generally involves quality control, de novo assembly of reads into contigs, binning of contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) using coverage and composition information, and finally, functional and taxonomic annotation of the assembled data [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Successful microbiome sequencing relies on a suite of specialized reagents and kits. The following table details essential solutions for key steps in the workflow.

| Item | Function/Application | Examples / Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Preservation Buffer | Stabilizes microbial community at point of collection; prevents shifts. | CosmosID collection kits; ZymoBIOMICS DNA/RNA Shield [25]. |

| Bead-Based Lysis Kit | Mechanical & chemical cell lysis; efficient for Gram-positive bacteria. | Kits with bead-beating step (e.g., Zymo Research Quick-DNA kits) [23] [25]. |

| 16S rRNA PCR Primers | Amplifies specific hypervariable regions for amplicon sequencing. | 27F/1492R for full-length; V3-V4 or V4-specific primers for short-read [23] [22]. |

| SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 | Prepares circularized DNA templates for PacBio HiFi sequencing. | Pacific Biosciences library prep kit [23]. |

| Native Barcoding Kit 96 | Adds barcodes to DNA for multiplexed ONT sequencing without PCR. | Oxford Nanopore kit (SQK-NBD109.24) [23]. |

| Metagenomic Assembly & Binning Tool | Assembles sequences and groups them into putative genomes (MAGs). | mmlong2 workflow for complex long-read datasets [21]. |

The choice between short-read and long-read sequencing is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather which is fit-for-purpose for a specific research question, budget, and sample type [24] [22].

Short-read sequencing remains the workhorse for large-scale, high-throughput profiling studies where the goal is to compare microbial community structures (beta-diversity) across hundreds of samples or to conduct genus-level association studies [2] [22]. Its high accuracy and low cost per sample make it ideal for this application.

Long-read sequencing is transformative for applications that require higher taxonomic resolution or complete genomic context. It is the preferred choice for: achieving species- and strain-level discrimination via full-length 16S sequencing [23] [20]; recovering high-quality, complete Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) from complex environments like soil [21]; resolving repetitive genomic elements and mobile genetic elements like plasmids [18] [20]; and providing rapid diagnostic results in clinical or outbreak settings due to its real-time sequencing capabilities [19] [20].

As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, the accuracy of long-read platforms is increasing while costs are decreasing, making them an increasingly accessible and powerful tool. For the most comprehensive insights, a hybrid approach, using both short- and long-read technologies, can sometimes offer the optimal balance of depth, accuracy, and genomic completeness [24]. Researchers are advised to base their final platform selection on a careful consideration of their primary objectives, required resolution, and available resources.

The Critical Role of Library Preparation in NGS Success

In next-generation sequencing (NGS) for microbiome analysis, library preparation is the critical bridge between a raw biological sample and actionable genomic insights. This process transforms extracted nucleic acids into a format compatible with sequencing platforms, directly determining the accuracy, reproducibility, and depth of microbial community characterization. Within the specific context of microbiome research, the choice between 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics is one of the earliest and most consequential decisions, guided by the research objectives [3]. 16S sequencing, targeting specific hypervariable regions, is a cost-effective method for taxonomic profiling and is widely used in bacterial population studies [3]. In contrast, shotgun metagenomics sequences all DNA in a sample, enabling functional analysis and the discovery of unculturable microorganisms but at a higher cost and computational expense [3]. The library preparation protocols for these two paths diverge significantly, and variations within each method—such as the choice of 16S hypervariable regions or the fragmentation technique for shotgun libraries—can introduce specific biases that impact downstream results [6] [26]. Therefore, a meticulously optimized library preparation protocol is not merely a preliminary step but a fundamental determinant of data integrity, influencing all subsequent biological interpretations in microbiome research.

Core Principles and Methodologies of NGS Library Preparation

The process of NGS library preparation consists of a series of standardized yet adaptable steps designed to fragment the genetic material and attach platform-specific oligonucleotide adapters. The general workflow involves nucleic acid extraction, fragmentation, adapter ligation, and library quantification [27].

Key Steps in Library Construction

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: The first step in every sample preparation protocol is isolating DNA or RNA from a variety of biological samples, such as blood, cultured cells, or tissue [27]. The quality and quantity of the extracted nucleic acids are crucial for the success of subsequent steps.

- Fragmentation: The targeted DNA sequences are fragmented to a desired length. This can be achieved through physical, enzymatic, or chemical methods. Enzymatic fragmentation continues to dominate due to its simplicity and compatibility with diverse sample types [28].

- Adapter Ligation: Specialized adapters are attached to the ends of the fragmented DNA. These adapters often include barcode sequences that permit sample multiplexing, allowing multiple libraries to be sequenced simultaneously in a single run [27].

- Amplification: This optional but common step uses polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to increase the amount of DNA library, which is essential for samples with small amounts of starting material [27].

- Purification and Quality Control: A final "clean-up" step removes unwanted material, such as adapter dimers or fragments that are too large or too small. Quality control confirms the quality and quantity of the final library before sequencing [27].

Common Challenges and Biases

Library preparation is prone to several challenges that can introduce bias and compromise data quality. A primary concern is amplification bias, where certain sequences are preferentially amplified over others during PCR, leading to an inaccurate representation of the original microbial community [27]. This is often reflected in a high PCR duplication rate. Inefficient library construction, characterized by a low percentage of fragments with correct adapters, can decrease data yield and increase the formation of chimeric reads [27]. Sample contamination is an inherent risk, particularly when many libraries are prepared in parallel. Finally, the large costs associated with laboratory equipment, trained personnel, and reagents can be a significant constraint [27].

Figure 1: Generalized NGS Library Preparation Workflow. The process transforms raw nucleic acids into a sequencer-ready format, with each stage being a potential source of bias.

Platform-Specific Considerations for Microbiome Analysis

The selection of a sequencing platform is a strategic decision that dictates the required library preparation approach and ultimately shapes the taxonomic resolution of a microbiome study. The choice often centers on the trade-off between read length, accuracy, throughput, and cost [18].

Short-Read vs. Long-Read Sequencing

Short-read platforms, such as Illumina, generate highly accurate reads (error rate < 0.1%) but are typically limited to a few hundred base pairs [6] [29]. This makes them suitable for sequencing specific hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene (e.g., V3-V4) for reliable genus-level classification [6]. However, their limited read length restricts the ability to resolve closely related bacterial species [6]. In contrast, long-read platforms from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) can generate reads spanning thousands of base pairs, enabling full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing (~1,500 bp) [6] [26]. This long-read capability provides higher taxonomic resolution, often enabling species-level and even strain-level identification [18]. Historically, long-read technologies were associated with higher error rates (5–15%), but recent advancements have significantly improved their accuracy [6].

Impact on Microbiome Characterization

Comparative studies highlight how these technical differences translate into varied biological outcomes. A 2025 comparative analysis of Illumina and ONT for respiratory microbiome profiling found that while Illumina captured greater species richness, ONT exhibited improved resolution for dominant bacterial species [6]. Another 2025 study on rabbit gut microbiota showed that ONT and PacBio offered superior species-level classification rates (76% and 63%, respectively) compared to Illumina (48%) [26]. However, it also noted that a significant portion of species-level assignments were labeled as "uncultured_bacterium," indicating a limitation of reference databases rather than the technology itself [26]. Furthermore, differential abundance analysis can reveal platform-specific biases; for example, ONT may overrepresent certain taxa (e.g., Enterococcus, Klebsiella) while underrepresenting others (e.g., Prevotella, Bacteroides) [6]. These findings emphasize that platform selection should align with study objectives: Illumina is ideal for broad microbial surveys, whereas ONT excels in applications requiring species-level resolution [6].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Sequencing Platforms for Microbiome Studies

| Platform | Read Length | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Ideal Microbiome Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina [6] [29] | Short-read (~300 bp) | High accuracy (error rate <0.1%), high throughput, low cost per gigabase | Limited species-level resolution | Large-scale population studies, genus-level profiling |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) [6] [26] | Long-read (~1,500 bp to >10,000 bp) | Species-level resolution, real-time data streaming, portability | Historically higher error rate, though improving | In-field sequencing, pathogen identification, haplotype resolution |

| PacBio [26] [29] | Long-read (average 10,000–25,000 bp) | High-fidelity (HiFi) reads with high accuracy | Higher cost, lower throughput | High-quality genome assembly, discovering novel microbes |

Best Practices for Optimal Library Preparation

Adhering to rigorous laboratory practices is essential for generating high-quality, reproducible NGS libraries, which is the foundation of robust microbiome data.

Technical Optimization and Quality Control

- Optimize Adapter Ligation: Use freshly prepared adapters and control ligation temperature and duration. Blunt-end ligations are typically performed at room temperature for 15–30 minutes, while ligations with cohesive ends are often performed at 12–16°C for longer durations [30].

- Handle Enzymes with Care: Maintain enzyme stability by avoiding repeated freeze-thaw cycles and storing them at recommended temperatures. Accurate pipetting is crucial to ensure consistent results [30].

- Normalize Libraries Accurately: Before pooling, ensure each library is normalized to contribute equally to the final sequencing pool. This prevents under- or over-representation of samples, which can bias sequencing depth and results [30].

- Implement Quality Control Checkpoints: Establish QC checkpoints at multiple stages: post-ligation, post-amplification, and post-normalization. Techniques like fragment analysis, qPCR, and fluorometry assess library quality and allow for early issue detection [30].

Automation and Contamination Prevention

Automation is a powerful strategy for mitigating the risks of manual library preparation. Automated systems standardize workflows, reduce human error and variability, and improve reproducibility, especially across large sample batches [28] [30]. They also provide traceability by logging every step of the workflow, which is vital for regulatory compliance and data reliability [30]. To minimize contamination, dedicate a pre-PCR room or area separate from post-amplification steps [27]. This reduces the risk of cross-contamination from amplified DNA products, a common pitfall in sensitive NGS workflows.

Figure 2: Essential Quality Control Checkpoints in the NGS workflow. Implementing QC at multiple stages ensures the integrity of the final library before sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful library preparation relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key components and their critical functions in the workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Library Preparation

| Reagent / Material | Function | Considerations for Microbiome Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit [6] [26] | Isolates DNA/RNA from complex biological samples. | Yield and purity are critical; protocols may need optimization for different sample types (e.g., soil vs. human gut). |

| DNA Library Prep Kit [31] [32] | Contains enzymes and buffers for fragmentation, end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation. | Platform-specific (e.g., Illumina, ONT); PCR-free kits are available to reduce amplification bias. |

| Index Adapters [27] [31] | Short, unique DNA sequences ligated to fragments; enable sample multiplexing. | Use unique dual indexes to improve demultiplexing accuracy and detect index hopping. |

| Bead-Based Cleanup Kits [28] [30] | Purify nucleic acids by size selection and remove enzymes, salts, and adapter dimers. | Crucial for removing primer dimers after 16S rRNA PCR amplification. |

| PCR Enzymes [27] | Amplify the adapter-ligated library to generate sufficient material for sequencing. | High-fidelity polymerases minimize amplification bias and errors. |

| Quality Control Assays [27] [30] | Quantify and qualify the final library (e.g., Fragment Analyzer, Qubit, qPCR). | qPCR provides the most accurate quantification of amplifiable libraries for loading onto the sequencer. |

In conclusion, library preparation is a critically dynamic and influential phase in the NGS workflow for microbiome analysis. There is no universal "best" protocol; instead, the optimal approach is dictated by a strategic alignment between the research question, the chosen sequencing technology, and the sample type. The decision to use 16S rRNA gene sequencing for cost-effective taxonomic census or shotgun metagenomics for functional potential and strain-level resolution will define the library construction path [3]. As sequencing technologies evolve, with long-read platforms closing the accuracy gap with short-read platforms, library preparation methods will continue to adapt [18]. Embracing automation, adhering to rigorous quality control, and understanding the inherent biases of each method are non-negotiable practices for generating reliable, reproducible data. By investing time and resources into optimizing this foundational step, researchers can ensure that their microbiome studies are built upon a solid experimental foundation, leading to more meaningful and trustworthy biological insights.

Essential Bioinformatic Considerations for Data Analysis

The selection of an appropriate Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) method serves as the foundational decision that dictates all subsequent bioinformatic workflows in microbiome analysis. This choice creates a cascade of technical requirements that span experimental design, computational infrastructure, and analytical methodologies. The growing diversity of available NGS platforms—from short-read Illumina systems to long-read PacBio and Oxford Nanopore technologies—has transformed microbiome research capabilities while introducing significant complexity to the bioinformatic landscape [33]. Within this context, bioinformatic considerations must evolve from secondary concerns to primary design criteria, as they directly determine the feasibility, accuracy, and biological relevance of research outcomes.

The critical importance of these bioinformatic considerations extends beyond technical implementation to impact the very scientific questions that can be addressed. As research transitions from descriptive catalogs of microbial communities to mechanistic investigations of ecosystem function, the integration of multi-omics data and advanced analytical approaches becomes essential [33] [34]. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for navigating the bioinformatic ecosystem surrounding NGS method selection, with particular emphasis on the computational strategies that underpin robust, reproducible, and biologically insightful microbiome research.

NGS Technology Landscape: Implications for Bioinformatic Workflows

The core sequencing technologies available for microbiome research present distinct advantages and limitations that directly shape subsequent bioinformatic requirements. Understanding these technical characteristics is essential for matching sequencing platforms to specific research objectives and ensuring that analytical workflows are appropriately designed.

Short-read technologies (e.g., Illumina) generate massive volumes of data (typically millions to billions of 35-700 bp reads) with low per-base error rates (~0.1-15%) but face limitations in taxonomic resolution, variant detection, and genome assembly contiguity due to their fragmentary nature [33]. These platforms produce data that excels for quantitative abundance measurements but struggles with resolving repetitive regions, structural variants, and complex genomic architectures.

Long-read technologies (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) address these limitations through read lengths that can span entire genes, operons, or even small genomes, enabling more complete genome assemblies and direct detection of structural variants [33]. The trade-offs historically included higher error rates and lower throughput, though these limitations have substantially improved in recent platform iterations. The bioinformatic implications include reduced assembly complexity but increased computational demands for error correction and base-calling.

The emerging field of targeted NGS approaches further expands this landscape, with capture-based and amplification-based methods enabling focused investigation of specific microbial groups or functional elements. Recent clinical comparisons demonstrate that capture-based tNGS achieves 93.17% accuracy and 99.43% sensitivity in pathogen identification, outperforming both mNGS and amplification-based approaches for routine diagnostics [17]. These methods reduce sequencing costs and computational burdens while introducing their own bioinformatic considerations around hybridization efficiency, amplification bias, and reference database completeness.

Table 1: Sequencing Platform Characteristics and Bioinformatic Implications

| Platform/Technology | Read Length | Accuracy | Throughput | Primary Bioinformatic Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | 35-700 bp | ~99.9% | 10GB-1.8TB | Genome assembly fragmentation; GC bias correction |

| PacBio | 10-25 kb | ~99.9% (HiFi) | 5-50 Gb | Computational resource requirements; data storage |

| Oxford Nanopore | Up to 2+ Mb | ~99% (duplex) | 10-50+ Gb | Basecalling optimization; error profile modeling |

| Capture-based tNGS | Varies | High | Targeted | Hybridization efficiency normalization; off-target analysis |

| Amplification-based tNGS | Varies | Variable | Targeted | PCR bias correction; primer dimers filtering |

Experimental Design and Data Generation Considerations

Robust bioinformatic analysis begins during experimental design, where choices about sample collection, library preparation, and sequencing depth establish fundamental parameters that either enable or constrain subsequent computational approaches. The integration of culturomics with metagenomics exemplifies how wet-laboratory and computational approaches can be synergistically combined to overcome the limitations of either method alone.

Culture-enriched metagenomic sequencing (CEMS) represents a powerful hybrid approach that leverages high-throughput culturing across diverse media conditions followed by metagenomic sequencing of the entire cultured community. This strategy recently demonstrated remarkably low overlap between culture-dependent and culture-independent methods, with CEMS and direct metagenomic sequencing (CIMS) identifying only 18% shared species, while 36.5% and 45.5% of species were unique to each method respectively [35]. This profound methodological complementarity highlights how experimental design directly shapes the observable biological reality in microbiome studies.

Library preparation protocols further dictate bioinformatic requirements through their influence on data structure and quality. For bacterial RIBO-seq analysis, which precisely maps ribosome positions on transcripts to monitor protein synthesis, critical experimental steps include rapid translation inhibition through flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen, mechanical cell disruption using mortar grinding with alumina to prevent RNA shearing, and careful buffer formulation with magnesium ions to preserve ribosomal integrity [36]. The resulting data enables transcriptome-wide measurement of translation dynamics but requires specialized preprocessing to isolate ribosome-protected mRNA fragments (28-30 nt) before alignment and quantification.

Sequencing depth requirements vary substantially across applications, with fundamental trade-offs between sample numbers, statistical power, and detection sensitivity. While 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing may require 10,000-50,000 reads per sample for community saturation, shotgun metagenomics typically demands 5-20 million reads per sample for adequate genome coverage, with precise requirements dependent on community complexity and target genome size [33]. These experimental parameters must be established during study design through power calculations and pilot studies to ensure that subsequent bioinformatic analyses can address the underlying biological questions.

Data Processing: From Raw Sequences to Biological Features

The transformation of raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful features represents a critical bioinformatic phase where analytical choices profoundly impact result interpretation. This process involves multiple computational steps, each with platform-specific considerations and quality control requirements.

Sequence Preprocessing and Quality Control

Initial data processing begins with quality assessment and adapter removal, with FastQC and fastp commonly employed for short-read data [34]. Long-read technologies require specialized quality control approaches focused on read length distribution and quality score calibration. For RIBO-seq data, size selection through polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) to isolate ribosome footprints (28-30 nt fragments) represents a critical experimental and computational step that must be carefully optimized [36]. Simultaneous RNA-seq data generation provides essential reference points for normalizing ribosome occupancy to transcript abundance, highlighting how multi-modal data integration strengthens analytical robustness.

Host DNA depletion presents particular challenges in clinical applications where microbial biomass may be low relative to host material. In respiratory infection diagnostics, methods combining Benzonase and Tween20 for human DNA removal have proven effective, though optimization is required to avoid simultaneous depletion of microbial sequences [17]. The bioinformatic validation of depletion efficiency through alignment to host reference genomes represents an essential quality control metric.

Sequence Alignment and Assembly Strategies

Alignment algorithm selection must be matched to both data type and research question. As detailed in Table 2, the alignment software landscape includes tools optimized for specific data types and applications, with choice impacting mapping efficiency, accuracy, and computational efficiency [37].

Table 2: Alignment Software Selection Guide

| Software | Primary Data Type | Key Strengths | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bowtie2 | DNA short reads | Ultra-fast; low memory usage; end-to-end/local modes | WGS/WES/ChIP-seq/ATAC-seq (short read DNA) |

| BWA-MEM | DNA short/medium reads | High accuracy (especially indels); supports >100bp reads | Resequencing; exome sequencing; PacBio CLR data |

| Minimap2 | Long reads universal | Extremely fast; low memory; optimized for ONT/PacBio | Long read alignment; cross-species comparison; quick short read analysis |

| STAR | RNA-seq | Accurate splice junction detection; supports chimeric alignment | RNA-seq transcript quantification; alternative splicing analysis |

| HISAT2 | RNA-seq | Lower memory usage than STAR; faster performance | Memory-constrained RNA-seq (e.g., single-cell RNA-seq) |

For metagenomic assembly, the choice between co-assembly and individual assembly strategies depends on project goals, with the former potentially providing better coverage for low-abundance community members but requiring substantial computational resources. Hybrid assembly approaches combining short and long reads have demonstrated particular promise for generating complete metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), leveraging the accuracy of short reads with the contiguity of long reads [33]. Assembly quality assessment through checkM and similar tools provides essential validation of reconstruction completeness and contamination levels.

Analytical Frameworks and Statistical Approaches

The transition from processed sequences to biological insights requires sophisticated statistical frameworks capable of addressing the high-dimensional, compositional, and sparse nature of microbiome data. These analytical approaches range from basic community profiling to complex multi-omics integration, each with specific implementation requirements and interpretive considerations.

Community Profiling and Differential Analysis

Taxonomic profiling forms the foundation of most microbiome analyses, with methods ranging from 16S rRNA amplicon sequence variant (ASV) analysis to metagenomic phylogenetic placement. The analysis of 16S data typically involves DADA2 or Deblur for ASV inference, followed by taxonomic assignment using reference databases such as SILVA or Greengenes [34]. For shotgun metagenomics, tools like Kraken2 provide fast taxonomic classification, while MetaPhlAn4 offers strain-level profiling with specifically curated marker gene databases [34].

Differential abundance analysis presents particular statistical challenges due to data compositionality, where changes in one taxon's abundance necessarily affect the relative proportions of others. Methods like DESeq2 (with appropriate modifications for compositional data), ANCOM-BC, and LinDA address these challenges through distinct statistical frameworks, with no single method outperforming others across all scenarios [34]. Experimental factors such as sample size, effect size, and sampling depth should guide tool selection, with simulation-based approaches increasingly employed for method benchmarking.

Multi-omics Integration and Functional Analysis

The integration of multiple data types represents both a major opportunity and significant challenge in modern microbiome bioinformatics. Metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, and metaproteomic data provide complementary perspectives on microbial community structure, functional potential, and actual activity, but their integration requires careful consideration of measurement scale, technical artifacts, and biological interpretation.

Functional analysis of metagenomic data typically involves pathway reconstruction using tools like HUMAnN3, which maps sequencing reads to protein families and metabolic pathways while accounting for taxonomic contributions [34]. For metatranscriptomic data, specialized tools like SAMSA2 and updated HUMAnN3 workflows enable identification of actively transcribed functions, though careful normalization to account for variation in ribosomal RNA depletion efficiency is essential.

Visualization represents a critical bridge between analytical outputs and biological interpretation, with platforms like MicrobiomeStatPlots providing comprehensive resources for creating publication-quality figures [38] [34]. This open-source platform offers over 80 distinct visualization templates spanning basic abundance plots to complex multi-omics integration displays, all implemented in R with fully reproducible code. The availability of such curated visualization resources substantially reduces the technical barrier between analytical results and biological insight.

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

The implementation of robust bioinformatic workflows depends on both computational tools and experimental reagents that ensure data quality and reproducibility. The following table details essential resources referenced throughout this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Extraction | QIAamp UCP Pathogen DNA Kit [17] | High-quality nucleic acid extraction with host depletion | Critical for low-biomass clinical samples; integrates Benzonase treatment |

| Library Preparation | Ovation RNA-Seq System [17] | cDNA synthesis and amplification for transcriptomics | Maintains representation of low-abundance transcripts |

| Ribosome Profiling | MagPure Pathogen DNA/RNA Kit [36] [17] | Simultaneous DNA/RNA extraction from limited samples | Enables parallel metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analysis |

| Sequence Alignment | Minimap2 [37] | Rapid long-read alignment | Essential for Nanopore/PacBio data; minimal resource requirements |

| Taxonomic Profiling | Kraken2 [34] | Fast metagenomic sequence classification | Custom database construction improves accuracy for specific environments |

| Pathway Analysis | HUMAnN3 [34] | Metabolic pathway reconstruction from metagenomes | Integrates taxonomic and functional analysis in unified pipeline |

| Visualization | MicrobiomeStatPlots [38] [34] | Comprehensive visualization gallery | 80+ reproducible templates; R-based implementation |

Integrated Workflow Visualization

The complex relationships between NGS method selection, bioinformatic workflows, and analytical outcomes are visualized below, highlighting key decision points and their implications throughout the analytical process.

NGS Bioinformatics Decision Workflow

A complementary visualization specifically details the data processing pipeline from raw sequences to analytical results, highlighting quality control checkpoints and methodological alternatives.

Bioinformatic Data Processing Pipeline

The rapidly evolving landscape of NGS technologies presents both unprecedented opportunities and significant analytical challenges for microbiome researchers. The selection of appropriate sequencing methods must be intimately connected with bioinformatic capabilities, as these computational considerations directly determine the biological insights that can be derived from complex microbial communities. As technological advances continue to transform the field—from long-read sequencing overcoming assembly fragmentation to targeted approaches enabling cost-effective clinical applications—bioinformatic strategies must similarly evolve to leverage these innovations while maintaining analytical rigor.

The integration of complementary methodologies represents a particularly promising direction, with hybrid approaches like CEMS demonstrating that combining cultivation with metagenomics can reveal substantially more microbial diversity than either method alone [35]. Similarly, the strategic combination of sequencing technologies—using short reads for quantitative accuracy and long reads for structural resolution—provides a powerful framework for comprehensive microbiome characterization. As these multi-modal approaches mature, the development of integrated bioinformatic platforms that streamline analytical workflows while maintaining flexibility for method-specific optimization will be essential for advancing microbiome research across diverse ecosystems and applications.

Matching NGS Methods to Your Research Goals: A Practical Framework

The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing has emerged as a cornerstone technique in microbial ecology, providing researchers with a powerful tool for cost-effective microbial community profiling. As a targeted amplicon sequencing approach, it enables the characterization of bacterial and archaeal populations by sequencing the 16S rRNA gene, a highly conserved genetic marker that contains both stable regions for primer binding and variable regions that serve as signatures for taxonomic classification [3] [2]. This method has revolutionized our ability to study complex microbial communities without the need for cultivation, overcoming a significant limitation of traditional microbiology since many environmental and host-associated microorganisms cannot be easily cultured in laboratory settings [39].

The technique's prominence in microbiome research stems from its balanced combination of practical accessibility and informative output. For researchers designing studies to investigate microbial diversity across various sample types—from human gut and skin to environmental samples like soil and water—16S rRNA sequencing offers a financially viable option for large-scale cohort studies where sample numbers may reach into the hundreds or thousands [40] [41]. While newer methods like shotgun metagenomics provide broader functional insights, 16S sequencing remains the preferred starting point for many investigations focused on establishing taxonomic composition and comparative diversity analyses across experimental conditions or treatment groups [22].

Technical Foundations of 16S rRNA Sequencing

The 16S rRNA Gene as a Phylogenetic Marker

The 16S rRNA gene is approximately 1,500 base pairs long and contains nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) interspersed between conserved regions [3] [2]. This genetic architecture makes it ideally suited for microbial phylogenetics and taxonomy. The conserved regions enable the design of universal PCR primers that can amplify this gene from a wide range of bacterial and archaeal species, while the hypervariable regions provide the sequence diversity necessary for differentiating between taxa [2]. The degree of sequence variation in these hypervariable regions correlates with taxonomic levels: closely related species share more similar V-region sequences than distantly related ones, allowing for phylogenetic placement and diversity assessments [3].

However, a significant technical consideration in 16S rRNA sequencing is the selection of which hypervariable region(s) to amplify and sequence. No single variable region can comprehensively differentiate all bacterial species, and different regions may yield varying taxonomic resolutions [2] [42]. For instance, the V4 region is often preferred for its taxonomic coverage and classification accuracy, while the V3-V4 regions are frequently used for intestinal specimens [22]. This choice impacts experimental design and can influence the resulting microbial community profiles, making it crucial to align the selected region with the specific research questions and expected microbial communities [42].

Experimental Workflow

The standard workflow for 16S rRNA sequencing involves multiple critical steps that can influence data quality and experimental outcomes.

Figure 1: 16S rRNA sequencing involves a structured workflow from sample collection to bioinformatic analysis, with quality control critical at each step.

Following sample collection and DNA extraction, the targeted amplification of specific hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene is performed using primer pairs designed for conserved flanking regions [25]. This PCR amplification step introduces both strengths and limitations to the method: it enables the detection of low-abundance taxa by amplifying the target gene, but may also introduce biases due to variations in primer binding efficiency across different taxonomic groups [42]. After amplification, the resulting amplicons are purified, quantified, and normalized before library preparation and sequencing on next-generation sequencing platforms [39] [25].

Comparative Analysis: 16S rRNA Sequencing vs. Alternative Methods

Key Methodological Differences

When selecting an appropriate sequencing method for microbiome research, understanding the fundamental differences between available approaches is crucial for making informed decisions aligned with research goals and resources.

Figure 2: 16S amplicon and shotgun metagenomic sequencing differ fundamentally in their approach, with targeted amplification enabling cost-effective taxonomy, while untargeted shotgun provides comprehensive functional insights.

Quantitative Comparison of Sequencing Methods

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of 16S rRNA sequencing against alternative microbiome profiling approaches

| Parameter | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics | Metatranscriptomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus level; species level with full-length sequencing [41] [42] | Species and strain level [41] | Species level (active community) |

| Functional Insights | Indirect inference via prediction tools [40] | Direct assessment of functional genes and pathways [41] | Direct measurement of gene expression |

| Coverage | Bacteria and Archaea only [41] | All domains (Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, Fungi) [41] | Transcriptionally active community |

| PCR Amplification | Required (targeted) [22] | Not required [22] | Required (after cDNA synthesis) |

| Host DNA Interference | Minimal (targeted amplification) [41] | Significant (requires host DNA depletion) [41] | Significant (requires host RNA depletion) |

| Cost per Sample | Low [41] [22] | High (standard) to Moderate (shallow) [41] | High |

| DNA Input Requirements | Low (can work with <1 ng DNA) [41] | Higher (typically ≥1 ng/μL) [41] | Variable (depends on RNA yield) |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Moderate | High | High |

| Ideal Application | Large-scale diversity studies, taxonomic profiling [40] [22] | Functional potential discovery, strain-level tracking [41] [22] | Assessment of active metabolic pathways |

Advantages and Limitations in Research Context

The primary advantage of 16S rRNA sequencing is its cost-effectiveness, particularly for studies requiring large sample sizes to achieve statistical power [40] [41]. The method's targeted nature means significantly less sequencing data is required per sample compared to shotgun metagenomics, reducing both sequencing costs and computational requirements for data storage and analysis [42]. This efficiency enables researchers to maximize sample size within budget constraints, a critical consideration for longitudinal studies or investigations requiring multiple experimental conditions.

However, the technique has several important limitations. The inference of functional capabilities from 16S data relies on computational prediction tools like PICRUSt2, Tax4Fun2, or PanFP, which predict gene families based on phylogenetic reference [40]. Recent systematic evaluations have raised concerns about these predictions, noting that they "generally do not have the necessary sensitivity to delineate health-related functional changes in the microbiome" [40]. Additionally, the variable copy number of the 16S rRNA gene among different bacterial species can confound abundance estimates, requiring normalization strategies for accurate quantitative interpretation [40].

Practical Implementation and Technical Considerations

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Materials

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for 16S rRNA sequencing workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preservation Media | Maintains nucleic acid integrity during storage/transport | Critical for preventing microbiome shifts post-collection [25] |

| Bead-Beating Lysis Kits | Mechanical and chemical disruption of cell walls | Essential for DNA extraction from Gram-positive bacteria [25] |

| Region-Specific Primer Panels | Amplification of target hypervariable regions | Choice impacts taxonomic resolution (e.g., V3-V4 for gut) [2] [22] |

| PCR Clean-up Kits | Purification of amplicons post-amplification | Removes primers, enzymes, and non-specific products [39] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Addition of adapters and barcodes for multiplexing | Enables pooling of multiple samples in one sequencing run [39] |

| Positive Control Standards | Mock microbial communities | Validates entire workflow and bioinformatic pipeline [43] |

| DNA Quantitation Kits | Accurate measurement of DNA concentration and quality | Critical for normalization before library preparation [39] |

Addressing Technical Challenges and Biases

Several technical challenges require careful consideration in 16S rRNA sequencing experiments. PCR amplification biases can occur due to variations in primer binding efficiency across different taxonomic groups, potentially leading to over- or under-representation of certain taxa [42]. This can be mitigated through careful primer selection and validation, and by using consistent PCR conditions across all samples in a study. The choice of hypervariable region significantly influences taxonomic resolution and community profiles, with different regions offering varying discriminative power for specific bacterial groups [2] [42].

Bioinformatic processing introduces additional considerations. The clustering method (OTUs vs. ASVs) impacts taxonomic granularity, with Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) providing higher resolution but potentially splitting single genomes due to intra-genomic 16S copy number variation [2]. The reference database selection (Greengenes, SILVA, or RDP) influences classification accuracy and coverage, as databases vary in curation quality and taxonomic breadth [2]. Recent computational advances, such as machine learning calibration tools like TaxaCal, show promise in reducing discrepancies between 16S and whole-genome sequencing data, improving species-level profiling accuracy [42].

Application in Research and Future Directions

16S rRNA sequencing has been successfully applied across diverse research domains, from investigating host-microbe interactions in human health to characterizing environmental microbial communities. In medical research, it has been instrumental in associating microbial dysbiosis with various conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, diabetes, and cancer [2] [42]. In environmental microbiology, the method enables monitoring of microbial community changes in response to pollutants, land use changes, or climate variations [22]. The technique's cost-effectiveness makes it particularly valuable for large-scale epidemiological studies and environmental monitoring programs where sample numbers are large, and budgets may be constrained.

The future of 16S rRNA sequencing is evolving alongside technological advancements. Full-length 16S sequencing using long-read technologies (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) improves species-level resolution, addressing a key limitation of short-read approaches that target limited hypervariable regions [43] [2]. Emerging methods like 16S-ITS-23S operon sequencing (~4,500 bp) provide even greater discriminatory power, potentially enabling strain-level differentiation for closely related taxa that cannot be resolved by standard 16S sequencing [43]. Additionally, integration with other data types through multi-omics approaches is expanding the utility of 16S data, while machine learning methods are enhancing the functional insights that can be reliably extracted from taxonomic profiles [42].

16S rRNA sequencing remains a powerful and accessible method for microbial community profiling, offering an optimal balance of cost-efficiency, technical robustness, and informative output for taxonomic characterization. While acknowledging its limitations in functional prediction and absolute quantification, researchers can strategically deploy this technology within a well-considered experimental framework that includes appropriate controls, validated bioinformatic pipelines, and careful interpretation of results. As the field advances, improvements in sequencing technologies, reference databases, and computational methods continue to expand the capabilities and applications of this foundational microbiome research tool, ensuring its continued relevance in advancing our understanding of microbial communities across diverse ecosystems.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing is a culture-independent approach that enables researchers to comprehensively sample all genes from all microorganisms present in a given complex sample. Unlike targeted methods such as 16S rRNA sequencing, shotgun metagenomics sequences the entire genomic content of a sample, providing not only taxonomic information but also insights into the functional potential of microbial communities [5]. This next-generation sequencing (NGS) method allows microbiologists to evaluate bacterial diversity and detect the abundance of microbes in various environments, making it particularly valuable for studying unculturable microorganisms that are otherwise difficult or impossible to analyze [5].

The fundamental advantage of shotgun metagenomics lies in its unbiased nature. By randomly shearing all DNA in a sample and sequencing the fragments, this approach allows for the detection and characterization of any microorganism—bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic—without prior knowledge or specific targeting [44] [45]. This capability is transformative for fields ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental microbiology, as it enables the discovery of novel pathogens and the comprehensive characterization of complex microbial ecosystems.

Core Principles and Comparative Advantages

Key Differentiators from Targeted Approaches