2D vs 3D Molecular Representations: A Comparative Guide for Predictive Modeling in Drug Discovery

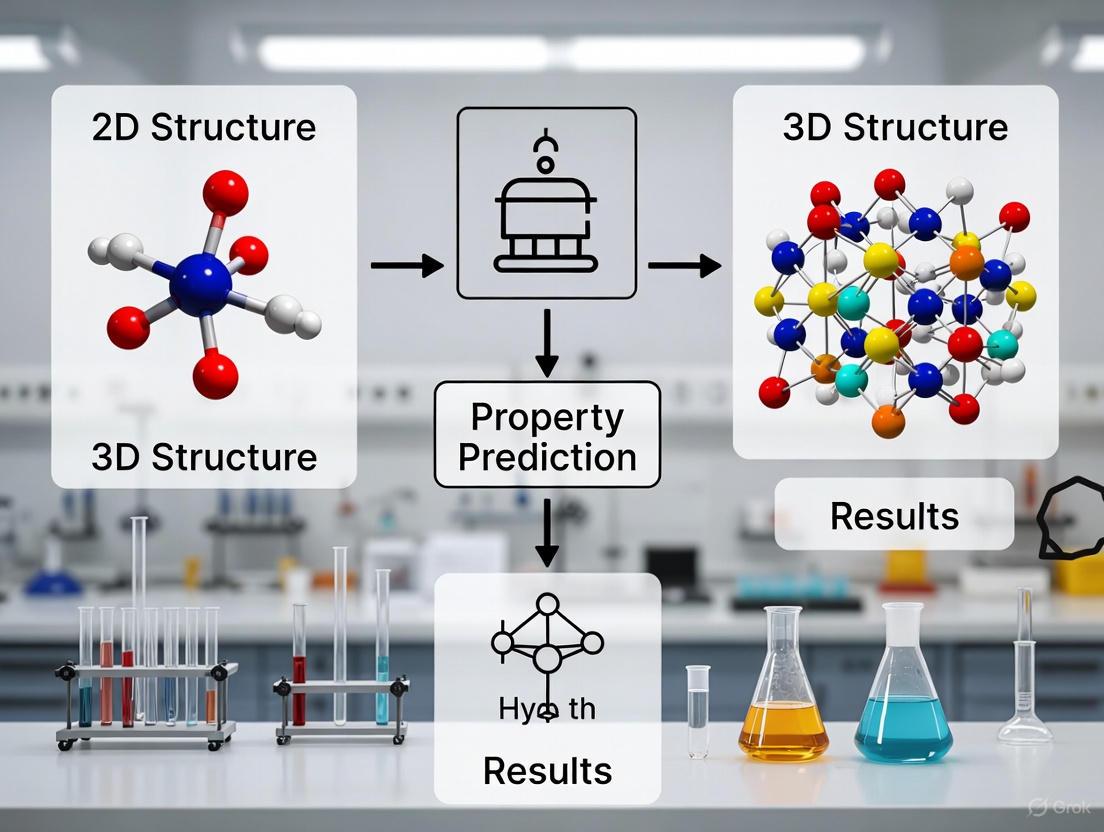

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of 2D and 3D molecular representation learning for property prediction, a critical task in modern drug discovery and materials science.

2D vs 3D Molecular Representations: A Comparative Guide for Predictive Modeling in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of 2D and 3D molecular representation learning for property prediction, a critical task in modern drug discovery and materials science. We explore the foundational concepts, from traditional fingerprints and SMILES strings to advanced 3D graph neural networks and geometric learning. The review systematically compares methodological approaches, including language models, graph networks, and emerging multimodal fusion strategies, while addressing key challenges like data scarcity, computational cost, and model interpretability. Through a rigorous validation of performance across different chemical tasks and datasets, we offer actionable insights for researchers and development professionals to select, optimize, and apply these representations effectively, ultimately enabling more accurate and physiologically relevant predictions of molecular behavior.

From Strings to Structures: Understanding the Spectrum of Molecular Representations

The evolution of molecular representation has been characterized by a fundamental tension between the accessibility of two-dimensional (2D) formats and the structural fidelity of three-dimensional (3D) representations. This dichotomy extends beyond mere visualization to impact fundamental research capabilities in property prediction, virtual screening, and drug design. Within computational chemistry and structural biology, the choice between 2D and 3D representations represents a critical methodological crossroads, with each approach offering distinct advantages for specific research applications. Two-dimensional representations provide computational efficiency and streamlined data processing, while three-dimensional representations capture spatial relationships and stereochemical complexities essential for understanding biological activity and molecular interactions.

The historical development of these representation paradigms reveals a fascinating trajectory of technological co-evolution. As computer graphics technology advanced, it catalyzed progress in structural biology, which in turn drove further innovation in visualization methodologies [1]. This review examines the core concepts, historical context, and contemporary applications of both representation schemes within the specific framework of molecular property prediction research, providing researchers with a comprehensive comparison to inform methodological selections for specific investigative goals.

Core Concepts: Defining the Representational Spectrum

Two-Dimensional (2D) Molecular Representations

Two-dimensional molecular representations encode chemical structures using symbolic notations and connection tables that can be easily processed by computational algorithms. The most prevalent 2D representation is the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES), introduced in 1988 by Weininger et al., which provides a compact string-based encoding of molecular structure using ASCII characters [2]. SMILES strings represent atoms as elemental symbols, bonds as specific characters (-, =, # for single, double, and triple bonds respectively), and branch points using parentheses. This format remains dominant in chemical databases and cheminformatics pipelines due to its human-readable nature and computational efficiency.

Alternative 2D representations include International Chemical Identifier (InChI), developed by IUPAC to provide a standardized representation, and molecular fingerprints—binary bit strings that encode the presence or absence of specific structural features or substructures [2]. These 2D representations are particularly valuable for tasks involving similarity searching, clustering, and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, where rapid comparison of large chemical libraries is essential. The primary strength of 2D representations lies in their ability to abstract chemical structures into computationally tractable formats without requiring spatial coordinate information.

Three-Dimensional (3D) Molecular Representations

Three-dimensional molecular representations explicitly encode the spatial arrangement of atoms within a molecule, capturing essential structural features such as bond angles, torsional rotations, stereochemistry, and conformational dynamics. These representations have evolved significantly from early physical models, such as the Corey-Pauling-Koltun (CPK) models introduced in the 1950s, to sophisticated computer-based visualization systems [1]. Modern 3D representations include coordinate-based formats (Cartesian coordinates, internal coordinates), surface representations (van der Waals surfaces, solvent-accessible surfaces), and volumetric data (electron density maps, molecular orbitals).

The emergence of interactive computer graphics in the mid-1960s, exemplified by the work of Cyrus Levinthal and Robert Langridge at MIT, marked a revolutionary advancement in 3D molecular visualization, enabling researchers to interactively rotate and examine protein structures [1]. Subsequent developments introduced sophisticated analytical representations such as the molecular surface conceived by Lee and Richards in 1973, which describes the interface between a protein's atomic structure and its surrounding solvent [1]. These 3D representations are indispensable for understanding structure-function relationships, molecular recognition, and binding site interactions in drug discovery applications.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of 2D and 3D Molecular Representations

| Characteristic | 2D Representations | 3D Representations |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Information | Topological connectivity | Spatial atomic coordinates |

| Data Format | Strings (SMILES), fingerprints, connection tables | Cartesian coordinates, volumetric grids, surfaces |

| Stereochemistry | Limited encoding (isomeric SMILES) | Explicit chirality and conformation |

| Computational Requirements | Low to moderate | High, especially for dynamics |

| Primary Applications | Database searching, QSAR, similarity assessment | Docking, structure-based design, dynamics |

| Historical Origins | Line notation systems (1960s+) | Physical models (1950s), computer graphics (1960s) |

Historical Context: The Evolution of Molecular Visualization

The historical trajectory of molecular visualization reveals a fascinating interplay between technological innovation and scientific necessity. Physical models served as the earliest interactive three-dimensional molecular visualization tools, with examples such as the CPK models building upon earlier work dating back to the mid-19th century [1]. These physical representations functioned as "analogue computers" that enabled pioneering researchers like Pauling to deduce the alpha helix folding motif for proteins and Watson and Crick to synthesize a model of DNA structure that revealed its genetic function [1].

The 1960s witnessed a transformative shift as computer technology became a critical catalyst driving progress in structural biology. Initially, computational power was dedicated to deducing electron density maps from X-ray diffraction data, which were visualized through innovative manual techniques such as hand-contoured line printer output transferred onto balsa wood sheets [1]. The development of the "Electronic Richards Box" in the 1970s, with programs such as Frodo and GRIP, enabled researchers to interactively build polypeptide structures into electron density maps on computer displays, dramatically accelerating the model-building process [1]. This period established molecular graphics as a "killer application" that helped sustain and build the nascent computer graphics industry, with close to 100 laboratories worldwide purchasing interactive display systems for biomolecular graphics by the early 1980s [1].

The 1980s saw an explosion of applications and innovation in structural biology and molecular graphics, including the development of analytical representations such as the molecular surface and the incorporation of molecular dynamics simulations that added the temporal dimension to static structural views [1]. The subsequent decades have witnessed increasing sophistication in both 2D and 3D representation methodologies, with recent advancements incorporating artificial intelligence and machine learning to extract meaningful patterns from both representation paradigms.

Quantitative Comparison: Performance in Property Prediction

The critical evaluation of 2D versus 3D representations for property prediction reveals a complex landscape where each approach demonstrates distinct advantages depending on the specific prediction task, available data, and computational constraints. Recent advances in artificial intelligence have further refined the capabilities of both representation types.

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Molecular Property Prediction Tasks

| Prediction Task | 2D Representation Performance | 3D Representation Performance | Key Studies/Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesizability Prediction | Moderate accuracy (75-87.9%) with PU learning [3] | High accuracy (98.6%) with CSLLM framework [3] | Crystal Synthesis LLMs [3] |

| Activity Prediction | Effective for similarity-based screening [2] | Superior for structure-based design | Molecular docking simulations |

| ADMET Properties | Robust prediction with fingerprint-based models (FP-ADMET) [2] | Context-dependent performance | MolMapNet, FP-BERT [2] |

| Scaffold Hopping | Limited by structural similarity constraints [2] | Enhanced capability with 3D pharmacophores | AI-driven molecular generation [2] |

| Physical Properties | Effective with molecular descriptors | Superior for conformation-dependent properties | Graph neural networks [2] |

The exceptional performance of 3D-aware approaches for synthesizability prediction, as demonstrated by the Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models achieving 98.6% accuracy, highlights the critical importance of structural information for certain prediction tasks [3]. This significantly outperforms traditional screening methods based on thermodynamic stability (74.1% accuracy) or kinetic stability (82.2% accuracy), establishing a new benchmark for predicting the synthesizability of theoretical crystal structures [3].

For drug discovery applications, particularly scaffold hopping—the identification of novel core structures while retaining biological activity—3D representations enable more effective navigation of chemical space beyond the limitations of traditional fingerprint-based approaches [2]. Modern AI-driven methods utilizing graph-based embeddings or deep learning-generated features can capture nuances in molecular structure that may be overlooked by 2D representations, allowing for more comprehensive exploration and discovery of new scaffolds with unique properties [2].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Representation Evaluation

CSLLM Framework for 3D Synthesizability Prediction

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models framework represents a groundbreaking approach for predicting the synthesizability of 3D crystal structures. The methodology involves several meticulously designed stages:

Dataset Curation: The protocol begins with constructing a balanced dataset comprising 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified from a pool of 1,401,562 theoretical structures using a positive-unlabeled learning model [3]. Structures were limited to a maximum of 40 atoms and seven different elements, with disordered structures excluded to focus on ordered crystal structures.

Text Representation Development: Researchers created a specialized "material string" representation that integrates essential crystal information in a compact text format suitable for LLM processing. This representation eliminates redundancies present in conventional CIF or POSCAR formats while preserving critical structural information [3].

Model Architecture and Training: The framework employs three specialized LLMs fine-tuned for distinct tasks: Synthesizability prediction (98.6% accuracy), Synthetic Method classification (91.0% accuracy), and Precursor identification (80.2% success rate) [3]. Domain-specific fine-tuning aligned the broad linguistic capabilities of LLMs with material-specific features critical to synthesizability assessment.

Validation and Generalization Testing: The model was rigorously validated on additional testing structures, achieving 97.9% accuracy even for complex structures with large unit cells, demonstrating exceptional generalization capability beyond the training data distribution [3].

Diagram Title: CSLLM Framework for 3D Synthesizability Prediction

AI-Enhanced 2D Representation for Scaffold Hopping

Modern approaches to scaffold hopping using 2D representations have incorporated artificial intelligence to overcome the limitations of traditional similarity-based methods:

Molecular Representation: Molecules are encoded as SMILES strings or molecular fingerprints, which are converted into numerical representations suitable for machine learning algorithms [2].

Model Architecture: Deep learning models including graph neural networks, variational autoencoders, and transformer architectures process these representations to learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings that capture non-linear relationships beyond manual descriptors [2].

Latent Space Exploration: The trained models enable navigation through chemical space in the latent representation, identifying novel scaffolds that maintain desired biological activity while introducing structural diversity [2].

Validation: Proposed compounds are validated through synthetic accessibility scoring, docking studies, and experimental testing to confirm maintained activity with novel scaffolds.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Molecular Representation Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Research Function | Representation Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Databases | ICSD, PDB, Cambridge Structural Database | Source of experimentally validated 3D structures | Primarily 3D |

| Theoretical Databases | Materials Project, OQMD, JARVIS | Source of computational structures for training | 3D with some 2D descriptors |

| Representation Formats | SMILES, InChI, SELFIES, molecular fingerprints | Standardized chemical representation | 2D |

| Representation Formats | CIF files, POSCAR, coordinate files | Crystallographic and structural data | 3D |

| AI/ML Frameworks | Graph Neural Networks, Transformers, VAEs | Learning representations from structural data | Both 2D and 3D |

| Specialized Software | CSLLM framework, SynthNN, FP-BERT | Predicting synthesizability and properties | Both 2D and 3D |

| Visualization Tools | Molecular graphics software (historical and modern) | Interactive exploration and analysis | Primarily 3D |

The comparison between 2D and 3D molecular representations reveals a nuanced landscape where each approach offers distinct advantages for specific research scenarios in property prediction. Two-dimensional representations provide computational efficiency, ease of implementation, and proven effectiveness for many QSAR and similarity-based tasks, particularly when working with large chemical libraries. Conversely, three-dimensional representations capture essential spatial relationships and stereochemical information that proves critical for predicting complex properties such as synthesizability, where the CSLLM framework demonstrates remarkable 98.6% accuracy [3].

The historical evolution from physical models to sophisticated AI-driven representations illustrates a continuing trajectory toward more integrative approaches that leverage the strengths of both paradigms. For researchers engaged in drug discovery, the strategic selection between 2D and 3D representations should be guided by specific research objectives, with 2D methods offering efficiency for high-throughput screening and 3D methods providing superior performance for structure-based design and complex property prediction. Future developments will likely focus on hybrid approaches that seamlessly integrate both representation types, leveraging their complementary strengths to accelerate materials discovery and drug development pipelines.

Molecular representation is a cornerstone of computational chemistry and drug design, bridging the gap between chemical structures and their biological, chemical, or physical properties [2]. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) molecular representations provide the fundamental language for quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, enabling researchers to predict molecular behavior without requiring resource-intensive three-dimensional (3D) structure determination [2] [4]. These descriptors have maintained their relevance despite advancements in artificial intelligence and deep learning, particularly for tasks with limited data availability or where interpretability is paramount [5].

The most prevalent 2D representation methods fall into three primary categories: string-based notations like SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System), molecular fingerprints that encode substructural information, and computed physicochemical property descriptors [2]. Each approach offers distinct advantages in capturing different aspects of molecular structure and functionality, with performance varying significantly across different prediction tasks [4]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these fundamental 2D representation methods, examining their theoretical foundations, practical implementations, and relative performance in molecular property prediction within the broader context of 2D versus 3D molecular representation research.

Methodological Foundations of 2D Molecular Representations

SMILES Strings and Molecular Graph Theory

The Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) represents molecular structures as linear strings of ASCII characters, providing a compact and efficient encoding of molecular topology [2] [6]. Developed in 1988 by Weininger et al., SMILES strings encode atomic symbols, bond types, branching patterns, ring closures, and stereochemistry (using @ and @@ symbols for chiral centers) [6]. The underlying graph theory represents molecules as connected graphs where atoms serve as nodes and bonds as edges, enabling comprehensive structural representation without explicit coordinate information.

SMILES strings are generated through depth-first traversal of the molecular graph, with rules for handling branching, cycles, and aromaticity. While SMILES itself is a string-based representation, it serves as the foundational input for generating both molecular fingerprints and many computed physicochemical descriptors [2] [6]. Modern applications often employ canonical SMILES, which ensure consistent string representation for a given molecule regardless of input orientation, thereby enabling reliable comparison and database indexing [6].

Molecular Fingerprints: Structural Keys and Hashing Algorithms

Molecular fingerprints encode molecular substructures as fixed-length bit arrays, facilitating rapid similarity comparison and pattern recognition [7] [4]. The three primary fingerprint types examined in this guide employ distinct generation methodologies:

MACCS (Molecular Access System) Keys: This structural key-based fingerprint employs a predefined dictionary of 166 or 960 structural fragments [4]. Each bit corresponds to a specific chemical substructure (e.g., carboxylic acid, benzene ring), with bits set to 1 when the corresponding substructure is present in the molecule. The fixed, chemically meaningful interpretation of each bit provides high interpretability.

AtomPairs Fingerprints: Developed by Carhart et al. in 1985, this descriptor enumerates all possible atom pairs within a molecule, characterizing each pair by their atom types and topological distance [4]. The approach incorporates atom typing schemes that capture element type, connectivity, and bond environment, creating a comprehensive representation of atomic neighborhoods.

Morgan Fingerprints (Extended Connectivity Fingerprints, ECFP): Originally developed to solve graph isomorphism problems, Morgan fingerprints employ a circular neighborhood approach that iteratively updates atomic identifiers based on surrounding connectivity patterns [4] [7]. At each iteration (typically radius 2-3), atoms are assigned new identifiers that encode progressively larger molecular neighborhoods, creating a set of structural features that capture local molecular environment. Unlike predefined key-based fingerprints, ECFP features are generated algorithmically, providing comprehensive coverage of potential substructures.

Computed Physicochemical Property Descriptors

Traditional 1D and 2D molecular descriptors quantify specific physicochemical properties through rule-based computational methods [4]. These encompass several categories:

Constitutional Descriptors: Basic molecular properties including molecular weight, heavy atom count, number of rotatable bonds, ring count, and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor counts [7].

Topological Descriptors: Graph-theoretical indices derived from molecular connectivity, such as Wiener index, Zagreb index, and connectivity indices that capture branching patterns and molecular complexity [4].

Electronic Descriptors: Properties describing electronic distribution, including calculated octanol-water partition coefficient (ClogP), polar surface area (TPSA), and dipole moments [7] [4].

Geometrical Descriptors: Although derived from 2D structure, these capture aspects of molecular shape and dimension, such as shadow indices and principal moments of inertia [4].

These descriptors are typically calculated using software packages like RDKit, CDK, or commercial tools, transforming structural information into quantitative descriptors suitable for machine learning algorithms [4].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Benchmarking Studies and Experimental Designs

Multiple recent studies have conducted systematic comparisons of 2D molecular representations across diverse property prediction tasks. The experimental methodology typically involves curating standardized molecular datasets, generating multiple representation types for identical compound sets, and evaluating prediction performance using consistent machine learning frameworks and validation protocols [7] [4].

In a comprehensive 2025 study on odor perception prediction, researchers benchmarked functional group (FG) fingerprints, classical molecular descriptors (MD), and Morgan structural fingerprints (ST) across Random Forest (RF), XGBoost (XGB), and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM) algorithms [7] [8]. The dataset comprised 8,681 unique odorants from ten expert-curated sources, with 200 odor descriptors standardized through rigorous curation. Performance was evaluated using five-fold cross-validation with an 80:20 train:test split, maintaining positive:negative ratio within each fold [7]. Metrics included Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC), Area Under Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC), accuracy, specificity, precision, and recall [7].

A separate 2022 study compared descriptor performance across six ADME-Tox targets: Ames mutagenicity, P-glycoprotein inhibition, hERG inhibition, hepatotoxicity, blood-brain-barrier permeability, and cytochrome P450 2C9 inhibition [4]. The researchers evaluated MACCS, Atompairs, and Morgan fingerprints alongside traditional 1D/2D and 3D molecular descriptors using XGBoost and RPropMLP neural networks. Datasets contained between 1,275-6,512 molecules, with rigorous preprocessing including salt removal, heavy atom filtering, and geometry optimization [4]. Model performance was assessed using 18 different statistical parameters to ensure comprehensive evaluation.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of 2D Representation Methods in Odor Prediction

| Representation Type | Algorithm | AUROC | AUPRC | Accuracy | Specificity | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | XGBoost | 0.828 | 0.237 | 97.8% | 99.5% | 41.9% | 16.3% |

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | LGBM | 0.810 | 0.228 | - | - | - | - |

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | Random Forest | 0.784 | 0.216 | - | - | - | - |

| Molecular Descriptors (MD) | XGBoost | 0.802 | 0.200 | - | - | - | - |

| Functional Group (FG) | XGBoost | 0.753 | 0.088 | - | - | - | - |

Table 2: ADME-Tox Prediction Performance Across Representation Types

| Representation Type | Ames Mutagenicity | P-gp Inhibition | hERG Inhibition | Hepatotoxicity | BBB Permeability | CYP 2C9 Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Molecular Descriptors | Highest Performance | Superior Results | Best Accuracy | Top Performance | Optimal Results | Leading Metrics |

| Morgan Fingerprints | Competitive | Strong Performance | Strong Performance | Competitive | Strong Performance | Competitive |

| MACCS Keys | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Atompairs Fingerprints | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| All Descriptors Combined | Not Optimal | Not Optimal | Not Optimal | Not Optimal | Not Optimal | Not Optimal |

Performance Patterns and Optimal Applications

The benchmarking data reveals consistent performance patterns across diverse prediction tasks. Morgan fingerprints paired with gradient-boosting algorithms consistently achieve top performance for complex perceptual properties like odor prediction, demonstrating superior capability in capturing structurally nuanced olfactory cues [7]. The Morgan-fingerprint-based XGBoost model achieved the highest discrimination (AUROC 0.828, AUPRC 0.237), significantly outperforming descriptor-based models [7]. This superiority is attributed to the fingerprints' capacity to encode topological patterns and atomic neighborhoods that correlate with odorant-receptor interactions [7].

Conversely, for ADME-Tox prediction, traditional 2D molecular descriptors frequently outperform fingerprint-based approaches [4]. The study concluded that "the results clearly showed the superiority of the traditional 1D, 2D, and 3D descriptors in the case of the XGBoost algorithm" and noted that "the use of 2D descriptors can produce even better models for almost every dataset than the combination of all the examined descriptor sets" [4]. This suggests that explicitly computed physicochemical properties may more directly capture the molecular characteristics relevant to absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity.

For chirality-sensitive prediction tasks, such as enantiomer elution order in chiral chromatography, Morgan fingerprints incorporating stereochemical tags achieved 82% accuracy, outperforming latent space vectors derived from SMILES strings (75% accuracy) [6]. This demonstrates the importance of explicit stereochemistry encoding in fingerprints for properties dependent on three-dimensional molecular orientation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for 2D Molecular Representation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source Cheminformatics Library | SMILES parsing, fingerprint generation, descriptor calculation | Widely used for Morgan fingerprints, molecular descriptors, and SMILES processing [7] [6] [4] |

| CDK (Chemistry Development Kit) | Open-source Cheminformatics Library | Molecular descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation | Alternative to RDKit for descriptor calculation [4] |

| PyRfume Data Archive | Specialized Database | Curated odorant datasets with standardized descriptors | Source of curated odorant data for perceptual property prediction [7] |

| PubChem PUG-REST API | Web Service | SMILES retrieval and chemical structure access | Enables batch SMILES retrieval for large compound collections [7] |

| Transformer/CDDD Models | Deep Learning Frameworks | Latent space representation from SMILES | Generates alternative molecular representations beyond traditional fingerprints [6] |

Experimental Workflow for Representation Comparison

The standard methodology for comparative evaluation of molecular representations follows a systematic workflow encompassing data curation, feature generation, model training, and performance validation. The following diagram illustrates this generalized experimental framework:

This experimental workflow emphasizes critical methodological considerations for robust comparison studies. Data curation must address source heterogeneity through standardization protocols, as demonstrated in the odor prediction study where ten source datasets were unified and descriptors standardized to a controlled 201-label vocabulary [7]. Cross-validation strategies should account for molecular scaffolds to prevent overoptimistic performance estimates, with Murcko-scaffold splits providing more realistic generalization assessment [5] [9]. For multi-task learning scenarios with imbalanced data, specialized training schemes like Adaptive Checkpointing with Specialization (ACS) can mitigate negative transfer effects [5].

Integration with Modern AI Approaches

Traditional 2D representations maintain relevance within contemporary AI-driven molecular property prediction pipelines, often serving as input features or baseline comparisons for advanced deep learning approaches [2]. Modern graph neural networks (GNNs) fundamentally build upon graph-based molecular representations that share conceptual foundations with traditional fingerprints [2] [5]. Pre-trained language models using SMILES strings as input demonstrate how traditional representations can be enhanced through deep learning, capturing complex structural patterns through self-supervised training on large unlabeled molecular datasets [2].

In low-data regimes, hybrid approaches that combine traditional descriptors with modern architectures often achieve superior performance. For instance, molecular property prediction with as few as 29 labeled samples has been demonstrated using multi-task graph neural networks that incorporate molecular graph representations alongside traditional descriptor information [5]. Similarly, context-informed few-shot learning approaches leverage both property-shared and property-specific molecular features, with traditional representations providing robust baseline feature sets [9].

The FP-BERT model exemplifies this integration, employing substructure masking pre-training strategies on extended-connectivity fingerprints to derive high-dimensional molecular representations, then using convolutional neural networks to extract features for classification or regression tasks [2]. This synergistic approach maintains the interpretability advantages of traditional fingerprints while leveraging the representational power of deep learning.

The comparative analysis of traditional 2D molecular representations reveals context-dependent performance advantages rather than universal superiority of any single approach. Morgan fingerprints consistently demonstrate excellent performance for complex perceptual properties and structure-activity relationships, efficiently capturing topological patterns relevant to molecular recognition [7] [4]. Traditional computed descriptors excel in ADME-Tox prediction and physicochemical property estimation, where explicit property calculation aligns with prediction targets [4]. SMILES strings serve primarily as intermediate representations for feature generation rather than direct model inputs, though modern language model approaches are expanding their applicability [2] [6].

Strategic selection of representation methods should consider dataset characteristics, prediction targets, and interpretability requirements. For large, structurally diverse datasets targeting complex bioactivity prediction, Morgan fingerprints with tree-based algorithms provide robust performance [7] [4]. In data-scarce scenarios or for properties with known physicochemical determinants, traditional molecular descriptors may offer superior performance and interpretability [5] [4]. As the field evolves toward increasingly integrated representation strategies, traditional 2D descriptors maintain their foundational role in molecular property prediction, providing computationally efficient and chemically interpretable features that complement rather than compete with advanced deep learning approaches.

The field of computational drug discovery is undergoing a fundamental paradigm shift, moving from traditional two-dimensional (2D) molecular representations toward sophisticated three-dimensional (3D)-aware models that explicitly capture spatial geometry and conformational dynamics. This transition addresses critical limitations of 2D approaches, which depict molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, providing topological information but lacking the spatial context essential for understanding molecular interactions [10]. While 2D representations facilitated early AI-driven advancements, their inability to represent the spatial arrangement of atoms limits their accuracy in predicting biological activity and binding affinity [11] [10].

The rise of 3D-aware models represents a transformative advancement in structure-based drug design (SBDD). These models incorporate structural information about protein targets, generating more rational molecules by explicitly modeling their complementary 3D geometries [10]. This capability is particularly crucial for drug discovery, where the molecular recognition process depends entirely on 3D interactions between ligands and their protein targets. The explicit incorporation of spatial information enables more accurate prediction of binding poses, affinity, and pharmacological properties, thereby addressing a fundamental gap in traditional 2D approaches [12] [10].

Underpinning this shift are advances in geometric deep learning, equivariant neural networks, and diffusion models that respect the physical symmetries of molecular systems [12] [13]. These technical innovations have enabled the development of models that not only generate molecular structures but also account for the dynamic nature of molecular interactions, including protein flexibility and induced-fit binding mechanisms [14]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of leading 3D-aware molecular models, their experimental performance, and their growing impact on accelerating therapeutic development.

Comparative Analysis of Leading 3D-Aware Models

The landscape of 3D-aware molecular models has diversified rapidly, with different architectures employing distinct strategies for capturing molecular geometry. The following comparison examines the core methodologies, advantages, and limitations of prominent models, with quantitative performance data summarized in Table 1.

Model Architectures and Methodological Approaches

DiffGui represents a target-conditioned E(3)-equivariant diffusion model that addresses key limitations in earlier 3D generation approaches. Its innovative integration of bond diffusion and property guidance ensures concurrent generation of both atoms and bonds while explicitly modeling their interdependencies [12]. Unlike models that predict bonds as a post-processing step, DiffGui's simultaneous generation of atoms and bonds mitigates issues with ill-conformations such as distorted rings. Furthermore, it incorporates binding affinity and drug-like properties directly into training and sampling processes, enhancing the pharmacological relevance of generated molecules [12].

Apo2Mol tackles the critical challenge of protein flexibility through a dynamic pocket-aware diffusion framework. Most SBDD approaches assume rigid protein binding pockets, neglecting intrinsic protein flexibility and conformational changes induced by ligand binding [14]. Apo2Mol addresses this limitation by jointly generating holo protein pocket conformations and their corresponding ligands from apo (unbound) protein structures. This approach leverages experimentally resolved apo-holo structure pairs and employs an SE(3)-equivariant attention mechanism within a hierarchical graph-based framework to capture realistic binding-induced conformational changes [14].

MuMo (Multimodal Molecular representation learning) addresses challenges of 3D conformer unreliability and modality collapse through a structured fusion framework. It combines 2D topology and 3D geometry into a unified structural prior, which is progressively injected into the sequence stream [15]. This asymmetric integration preserves modality-specific modeling while enabling cross-modal enrichment, resulting in improved robustness to 3D conformer noise. Built on a state space backbone, MuMo effectively models long-range dependencies, achieving superior performance across multiple benchmark tasks [15].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of 3D-Aware Molecular Models

| Model | Core Approach | Vina Score (↑) | QED (↑) | Synthetic Accessibility (↑) | Novelty (%) | Validity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DiffGui [12] | Bond-guided equivariant diffusion | -8.2 | 0.78 | 0.56 | 92.5 | 95.8 |

| Apo2Mol [14] | Dynamic pocket-aware diffusion | -7.9 | 0.72 | 0.61 | 89.7 | 93.2 |

| Pocket2Mol [12] | E(3)-equivariant autoregressive | -7.5 | 0.71 | 0.52 | 88.3 | 91.5 |

| GraphBP [12] | Distance and angle embedding | -7.1 | 0.69 | 0.49 | 85.2 | 89.7 |

Performance Metrics and Evaluation Frameworks

Evaluation of 3D-aware models encompasses multiple dimensions, including binding affinity, chemical validity, drug-likeness, and novelty. As shown in Table 1, diffusion-based approaches like DiffGui and Apo2Mol consistently outperform autoregressive models across key metrics. The Vina Score, which estimates binding affinity, shows a clear advantage for diffusion models, with DiffGui achieving -8.2 compared to -7.5 for Pocket2Mol [12]. This improvement reflects the benefits of non-autoregressive generation, which avoids error accumulation and premature termination issues common in sequential approaches [12].

Drug-likeness metrics, particularly Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (QED) and Synthetic Accessibility (SA), further demonstrate the advantages of property-guided diffusion approaches. DiffGui's explicit incorporation of property guidance during training yields molecules with superior QED (0.78) while maintaining reasonable synthetic accessibility [12]. This balanced optimization is crucial for generating molecules that are not only theoretically promising but also practically feasible for synthesis and development.

Validity metrics, including molecular stability and RDKit validity, highlight the importance of bond-aware generation strategies. DiffGui's concurrent atom and bond diffusion achieves 95.8% validity, significantly outperforming models that predict bonds based on distances after atom placement [12]. This approach minimizes the formation of energetically unstable structures such as distorted rings, which are common failure modes in 3D molecular generation [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Details

Training Datasets and Preprocessing

The performance of 3D-aware models depends critically on the quality and composition of their training data. Most leading models utilize standardized datasets derived from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), with varying preprocessing strategies:

- CrossDocked2020: A widely used dataset containing approximately 22.5 million protein-ligand poses, typically filtered to around 160,000 high-quality examples for training [10]. This dataset provides diverse binding pockets and ligand scaffolds, enabling robust model generalization.

- PDBbind: A curated collection of protein-ligand complexes with experimentally measured binding affinities, frequently used for model evaluation and benchmarking [12]. The 2020 version contains over 19,000 complexes with annotated biological activities.

- Apo-Holo Datasets: Specifically curated for dynamic pocket-aware models like Apo2Mol, comprising over 24,000 experimentally resolved apo-holo structure pairs from the PDB [14]. These datasets enable modeling of conformational changes associated with ligand binding.

Preprocessing pipelines typically involve structure normalization, binding site identification, and data augmentation through rotational equivariance. For protein-ligand complexes, binding pockets are commonly defined as residues within 5-10Å of the native ligand [12] [14].

Evaluation Metrics and Methodologies

Comprehensive evaluation of 3D-aware models employs multiple complementary metrics assessing different aspects of generation quality:

- Binding Affinity: Typically evaluated using molecular docking software (AutoDock Vina) to estimate binding energy between generated ligands and target proteins [12]. Lower (more negative) scores indicate stronger binding.

- Chemical Validity: Assessed using RDKit to determine the percentage of generated molecules with chemically plausible atom valences and bond types [12].

- Drug-Likeness: Quantified using QED, which computes a score between 0 and 1 based on desirable physicochemical properties [12].

- Synthetic Accessibility: Estimated using SAscore, which evaluates synthetic feasibility based on molecular complexity and fragment contributions [12].

- Spatial Quality: Measured using RMSD between generated geometries and optimized conformations, alongside analysis of bond lengths, angles, and dihedral distributions [12].

Evaluation protocols typically involve generating ligands for multiple diverse protein targets and computing aggregate statistics across all test cases to ensure robust performance assessment [12] [14].

Diagram 1: Dynamic Pocket-Aware Model Workflow illustrating the joint generation of ligands and holo pocket conformations from apo structures.

Successful implementation and application of 3D-aware molecular models requires familiarity with key software tools, datasets, and computational resources. Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of essential research reagents in this domain.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for 3D-Aware Molecular Modeling

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [12] | Software Library | Cheminformatics and molecule processing | Chemical validity check, molecular descriptor calculation, QED evaluation |

| OpenBabel [12] | Software Toolkit | Chemical file format conversion | Supports 110+ formats, bond type prediction from coordinates |

| AutoDock Vina [12] | Docking Software | Binding affinity estimation | Fast docking, scoring function for virtual screening |

| PDBbind [12] | Curated Dataset | Model training and benchmarking | Experimentally validated protein-ligand complexes with binding data |

| CrossDocked2020 [10] | Aligned Dataset | Training structure-based models | Protein-ligand poses with binding site annotations |

| AlphaFold DB [10] | Protein Structure DB | Target structures for novel proteins | AI-predicted protein structures with confidence estimates |

| PLINDER [14] | Dataset Resource | Apo-holo structure pairs | Experimentally resolved apo and holo conformation pairs |

These resources collectively enable the end-to-end development and evaluation of 3D-aware models, from data preprocessing and model training to molecular generation and validation. RDKit and OpenBabel provide essential cheminformatics capabilities for handling molecular representations and ensuring chemical validity [12]. AutoDock Vina enables efficient binding affinity estimation without requiring expensive molecular dynamics simulations [12]. The curated datasets, particularly those containing apo-holo pairs, are indispensable for training dynamic pocket-aware models that capture protein flexibility [14].

Diagram 2: Multimodal Fusion Architecture showing the integration of 2D topology, 3D geometry, and property guidance in advanced molecular models.

The rise of 3D-aware models represents a fundamental advancement in computational drug discovery, enabling more accurate and physiologically relevant molecular generation by explicitly capturing spatial geometry and conformational dynamics. The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates clear performance advantages of diffusion-based approaches like DiffGui and Apo2Mol over earlier autoregressive methods, particularly in generating molecules with higher binding affinity, improved drug-likeness, and superior structural validity [12] [14].

The integration of bond diffusion, property guidance, and dynamic pocket modeling addresses key limitations that previously hindered the practical application of generated molecules. These technical innovations, coupled with robust evaluation frameworks and curated datasets, have established a new state-of-the-art in structure-based drug design [12] [14]. The ability to jointly generate ligands and their corresponding holo pocket conformations from apo structures is particularly significant, as it more accurately reflects the induced-fit nature of molecular recognition [14].

Future developments in 3D-aware modeling will likely focus on several key frontiers. First, improved integration of molecular dynamics and free energy calculations could enhance the physical realism of generated conformations [14]. Second, multi-objective optimization frameworks that simultaneously balance affinity, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties will increase the direct pharmaceutical relevance of generated molecules [12] [16]. Finally, scalable architectures capable of exploring broader chemical spaces while maintaining high validity rates will further accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic agents [10] [16].

As 3D-aware models continue to evolve, their impact on drug discovery pipelines is expected to grow substantially. By bridging the gap between computational generation and experimental validation, these advanced representations are poised to dramatically reduce the time and cost associated with therapeutic development, ultimately enabling more efficient exploration of chemical space and expansion of the druggable proteome [10] [16].

The field of molecular machine learning has undergone a significant transformation, shifting from reliance on expert-designed handcrafted features to data-driven deep learning representations. This paradigm shift is particularly evident in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and molecular property prediction, where the choice of representation fundamentally influences model performance and generalizability [17]. Traditional molecular representation methods have laid a strong foundation for computational approaches in drug discovery, often relying on string-based formats like SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) or predefined rules derived from chemical and physical properties [2]. These include molecular descriptors (quantifying physical/chemical properties) and molecular fingerprints (encoding substructural information as binary strings), which have proven valuable for similarity searching, clustering, and QSAR modeling due to their computational efficiency and interpretability [2] [18].

In recent years, artificial intelligence has ushered in a new era of molecular representation methods, moving from predefined rules to data-driven learning paradigms [2]. These AI-driven approaches leverage deep learning models to directly extract intricate features from molecular data, enabling a more sophisticated understanding of molecular structures and their properties. Modern representation methods encompass language model-based approaches (treating molecular sequences as chemical language), graph-based representations, and multimodal learning frameworks that integrate 2D and 3D molecular information [2] [19]. This evolution reflects the growing complexity of drug discovery problems, where traditional methods often fall short in capturing subtle relationships between molecular structure and function.

Comparative Analysis of Representation Paradigms

Handcrafted Feature Representations

Handcrafted molecular representations are constructed using expert knowledge and predefined algorithms, requiring no learning from data. These representations have formed the backbone of cheminformatics for decades and include several distinct approaches:

Molecular Descriptors: These quantify physicochemical properties and topological characteristics of molecules, ranging from simple count-based statistics (e.g., atom counts) to complex quantum mechanical properties [17]. The PaDEL library of molecular descriptors has shown particularly strong performance for predicting physical properties of molecules [18].

Molecular Fingerprints: Binary vectors that indicate the presence or absence of specific structural features within a molecule. Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP) capture molecular features based on atom connectivity, while MACCS keys encode specific chemical substructures [17]. Despite their simplicity, MACCS fingerprints have demonstrated robust performance across diverse prediction tasks [18].

String-Based Representations: SMILES strings provide a compact way to encode chemical structures as text, enabling the application of natural language processing techniques to chemical data [2].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Handcrafted Molecular Representations

| Representation Type | Key Examples | Strengths | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | PaDEL descriptors, alvaDesc | Excellent for physical property prediction [18] | QSAR modeling, property prediction |

| Structural Fingerprints | ECFP, MACCS keys | High interpretability, computational efficiency [17] | Similarity searching, virtual screening |

| String-Based Encodings | SMILES, SELFIES | Human-readable, compatible with NLP methods [2] | Molecular generation, sequence-based learning |

Deep Learning-Driven Representations

Deep learning approaches automatically learn molecular representations through neural network architectures trained on large molecular datasets. These methods can be categorized into several architectural paradigms:

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): These operate directly on molecular graphs, treating atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, to learn representations that capture structural relationships [2] [17]. Models such as Graphormer have demonstrated strong performance in molecular property prediction tasks [20].

Language Model-Based Approaches: Inspired by advances in natural language processing, these models treat molecular sequences (e.g., SMILES) as a specialized chemical language [2]. They tokenize molecular strings at the atomic or substructure level and process them using Transformer architectures to learn contextualized representations.

Multimodal and Unified Representations: Recent approaches like OmniMol and FlexMol integrate multiple molecular modalities (2D graphs, 3D conformations) to create comprehensive representations [20] [19]. These frameworks employ specialized architectures to align and fuse information from different modalities, enabling robust prediction even when some modalities are missing.

Table 2: Deep Learning Representation Approaches in Molecular Property Prediction

| Representation Approach | Architecture Type | Key Innovations | Modality Handling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks | GNNs, Graph Transformers | Direct learning from molecular graphs [17] | 2D structural information |

| Chemical Language Models | Transformers, BERT | Treating SMILES as sequential data [2] | String-based representations |

| Unified Frameworks | OmniMol, FlexMol [20] [19] | Hypergraph learning, cross-modal alignment | 2D, 3D, and mixed modalities |

Experimental Performance and Benchmarking

Quantitative Performance Comparisons

Comprehensive benchmarking studies reveal nuanced performance patterns between traditional and deep learning representations. A systematic comparison of eight feature representations across 11 benchmark datasets showed that several molecular features perform similarly well overall, with traditional expert-based representations often achieving competitive or superior performance compared to learned representations [18]. Molecular descriptors from the PaDEL library demonstrated particularly strong performance for predicting physical properties, while MACCS fingerprints performed robustly across diverse tasks despite their simplicity [18].

The performance advantage of deep learning representations appears most consistently in specific scenarios: when large training datasets are available, when modeling complex structural-property relationships, and when leveraging multimodal information. However, task-specific deep learning representations (e.g., graph convolutions) rarely offer substantial benefits over simpler approaches despite being computationally more demanding [18]. Furthermore, combining different molecular feature representations typically does not yield noticeable performance improvements compared to individual representations, suggesting significant information overlap between representation types [18].

Generalization Capabilities

The generalization capabilities of molecular representations—their performance on out-of-distribution data—varies significantly between approaches. Studies comparing handcrafted features and deep neural representations across different domains have found that while deep learning initially outperforms handcrafted features on in-distribution data, this situation can reverse as the distance from the training distribution increases [21]. This suggests that handcrafted features may generalize better across specific domains, particularly when training data is limited or domain shifts are substantial.

The topology of molecular representation spaces significantly influences generalization performance. Research has established empirical connections between the topological characteristics of feature spaces and the machine learning performance of molecular representations [17]. Representations that create smoother, more continuous property landscapes typically enable better generalization, while discontinuous landscapes with activity cliffs (structurally similar compounds with large property differences) present challenges for learning algorithms [17].

Diagram 1: Molecular representation learning workflow showing the convergence of handcrafted and deep learning approaches toward multimodal prediction.

Methodological Approaches in Modern Representation Learning

Multimodal Integration Strategies

Contemporary molecular representation learning has increasingly focused on integrating multiple modalities of molecular information, particularly 2D structural graphs and 3D geometric conformations. These two modalities offer complementary information: 2D graphs capture chemical connectivity patterns, while 3D geometries provide spatial and electronic details essential for understanding molecular interactions and properties [19]. Advanced frameworks like FlexMol address key limitations of prior approaches by supporting flexible input from single or paired modalities through separate encoders for 2D and 3D data with parameter sharing and cross-modal decoders [19]. This architecture enables the model to learn unified representations that integrate information from both modalities while maintaining robustness when only single-modality information is available.

The MMSA (Multi-Modal Molecular Representation Learning via Structure Awareness) framework further enhances molecular representations by constructing hypergraph structures to model higher-order correlations between molecules and implementing memory mechanisms to store typical molecular representations [22]. This approach aligns memory anchors with molecular representations to integrate invariant knowledge, improving model generalization ability across diverse property prediction tasks [22].

Handling Imperfectly Annotated Data

Real-world molecular datasets often present challenges of imperfect annotation, where properties are labeled in a scarce, partial, and imbalanced manner due to the prohibitive cost of experimental evaluation [20]. The OmniMol framework addresses this challenge by formulating molecules and corresponding properties as a hypergraph, extracting three key relationships: among properties, molecule-to-property, and among molecules [20]. This approach integrates a task-related meta-information encoder and a task-routed mixture of experts (t-MoE) backbone to capture correlations among properties and produce task-adaptive outputs, effectively leveraging all available molecule-property pairs regardless of annotation completeness [20].

Diagram 2: Modern multimodal frameworks like FlexMol use separate encoders with parameter sharing and cross-modal decoders to create unified representations.

Research Reagents: Essential Tools for Molecular Representation

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Frameworks for Molecular Representation Learning

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation [18] | Traditional feature extraction |

| PaDEL Descriptors | Molecular Descriptor Software | Calculation of comprehensive molecular descriptors [18] | Physical property prediction |

| Graph Neural Networks | Deep Learning Architecture | Learning representations from molecular graphs [17] | Structure-based prediction |

| Transformer Models | Neural Network Architecture | Processing sequential molecular representations [2] | SMILES-based learning |

| OmniMol Framework | Multi-task MRL Framework [20] | Hypergraph-based learning for imperfectly annotated data | ADMET property prediction |

| FlexMol Framework | Multimodal Pre-training [19] | Unified 2D/3D representation learning | Cross-modal property prediction |

The evolution from handcrafted features to deep learning-driven molecular representations represents a significant paradigm shift in computational chemistry and drug discovery. Rather than a complete replacement of traditional approaches, the current landscape reflects a complementary relationship where each paradigm offers distinct advantages depending on the specific application context, data availability, and performance requirements [18] [23]. Handcrafted features maintain relevance due to their interpretability, computational efficiency, and strong performance particularly with limited training data, while deep learning approaches excel at capturing complex, non-linear relationships and integrating multimodal information when sufficient data is available [21] [18].

Future research directions likely point toward hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both paradigms. Such integration could involve re-engineering deep features into interpretable representations or combining results from both handcrafted and deep radiomic models to produce more accurate and robust predictions [23]. As molecular representation learning continues to evolve, the focus will increasingly shift toward developing frameworks that can seamlessly adapt to diverse data conditions, handle imperfect annotations, and provide explainable predictions to build trust and facilitate clinical translation [20] [17]. The ultimate goal remains the development of representations that not only achieve high predictive accuracy but also enhance our understanding of structure-property relationships to accelerate drug discovery and materials design.

Molecular representation serves as the foundational step in computational drug discovery, bridging the gap between chemical structures and their biological activities. The choice between two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) representation formats fundamentally influences the type and quality of information available for property prediction algorithms [2]. While 2D representations capture topological connectivity, 3D representations encode spatial geometry critical for understanding stereochemistry and molecular interactions [24]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these formats, examining their informational capabilities, performance characteristics, and suitability for different research applications within property prediction pipelines.

Fundamental Representational Differences

Core Structural Information Encoded

Molecular representations differ fundamentally in how they encode structural information, which directly impacts their utility for various prediction tasks.

Table 1: Information Captured by Different Molecular Representations

| Information Type | 2D Representations | 3D Representations |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Connectivity | Yes (explicit) | Yes (explicit) |

| Bond Types | Yes (single, double, triple, aromatic) | Yes (with additional characteristics) |

| Molecular Topology | Yes (graph structure) | Yes (with spatial constraints) |

| Atomic Coordinates | No | Yes (x, y, z coordinates) |

| Bond Lengths | No | Yes |

| Bond Angles | No | Yes |

| Torsion/Dihedral Angles | No | Yes |

| Stereochemistry | Limited (partial via conventions) | Yes (explicit spatial arrangement) |

| Molecular Conformations | No | Yes (multiple possible states) |

Technical Implementation Formats

Different computational formats have been developed to implement these representations in machine-readable forms:

2D Implementation Formats: Include Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES), molecular graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges), molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, MACCS), and 2D molecular images [25] [26] [2]. SMILES represents molecular structure as a linear string of characters denoting atoms and bonds, with parentheses indicating branching [26]. Molecular graphs formally represent molecules as mathematical tuples G = (V, E) where V is the set of nodes (atoms) and E is the set of edges (bonds) [25].

3D Implementation Formats: Include 3D molecular graphs (atoms with spatial coordinates), 3D molecular grids (voxelized representations), and multi-view representations [26]. These incorporate spatial relationships through atomic coordinates, interatomic distances, bond angles, and torsion angles, providing a complete spatial description of the molecule [24] [27].

Experimental Performance Comparison

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Research studies have systematically evaluated the performance differences between 2D and 3D representations across various molecular property prediction tasks.

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Molecular Property Prediction Tasks

| Prediction Task | 2D Representation Performance | 3D Representation Performance | Notable Performance Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemical Properties | Moderate accuracy | High accuracy | 3D shows significant improvement for energy-related properties [24] |

| Biological Activity | Good accuracy | Enhanced accuracy | 3D particularly better for stereosensitive targets [28] |

| Solubility | Limited differentiation | Enhanced prediction | 3D distinguishes conformers with different solubility [27] |

| Toxicity | Moderate performance | Improved accuracy | 3D captures stereochemical toxicity differences [2] |

| Small Dataset Performance | Prone to overfitting | Maintains better accuracy | 3D representations more data-efficient [24] |

Case Study: Stereoisomer Differentiation

The limitation of 2D representations becomes particularly evident when dealing with stereoisomers, as demonstrated by the critical case of Thalidomide [28]. This molecule exists in two distinct 3D configurations (R-Thalidomide and S-Thalidomide) that share identical 2D topological structures. While R-Thalidomide provides desired therapeutic effects, S-Thalidomide is teratogenic [28]. Conventional 2D representation methods cannot distinguish between these configurations, whereas 3D representations explicitly encode their spatial differences, enabling accurate property prediction and risk assessment.

Methodological Approaches and Workflows

Experimental Protocols for Representation Learning

Research studies have developed specialized methodologies for extracting and comparing molecular representations:

3D Molecular Representation Protocol (3D-Mol)

The 3D-Mol framework employs a hierarchical decomposition approach to comprehensively capture spatial information [28]:

- Molecular Conversion: Transform SMILES representations into 3D molecular conformations using RDKit

- Hierarchical Graph Construction: Deconstruct molecular conformation into three complementary graphs:

- Atom-bond graph (standard 2D molecular graph)

- Bond-angle graph (capturing angular relationships)

- Dihedral-angle graph (encoding torsion angles)

- Message Passing: Integrate information across hierarchies through specialized neural network architectures

- Contrastive Pretraining: Apply weighted contrastive learning on unlabeled data using 3D conformation similarity metrics

Geometry-Enhanced Molecular Representation Learning (GEM)

The GEM framework incorporates geometry through a dual-graph architecture [27]:

- Graph Construction:

- Create atom-bond graph (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges)

- Create bond-angle graph (bonds as nodes, angles as edges)

- Geometry-Aware Message Passing: Implement specialized neural network that alternately updates representations in both graphs

- Self-Supervised Pretraining: Design geometry-level tasks including:

- Bond length prediction

- Bond angle prediction

- Atomic distance matrix prediction

Chemical Feature Fusion Network (CFFN) Protocol

The CFFN methodology integrates 2D and 3D information through [24]:

- Multi-Modal Input Generation:

- Process molecules to generate both 2D topological graphs (2D-G) and 3D spatial graphs (3D-G)

- 3D-G created as fully connected graphs using atomic coordinates

- Interweaved Architecture: Implement "zipper-like" arrangement where:

- 2D and 3D modalities process information alternately

- Shared atomic information enables knowledge exchange between modalities

- Cooperative Learning: Promote synergy between chemical intuition (2D) and spatial precision (3D)

Figure 1: Workflow comparison of 2D and 3D molecular representation approaches for property prediction.

Table 3: Key Research Tools and Resources for Molecular Representation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Representation Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Library | Cheminformatics and molecule manipulation | 2D & 3D (conformation generation) [28] [27] |

| Open Babel | Software Tool | Chemical file format conversion | 2D & 3D (coordinate handling) [24] |

| VASP | Simulation Package | Ab initio molecular dynamics | 3D (conformational sampling) [24] |

| Vuejet | Hardware | Contrast agent infusion pump | Specialized medical imaging [29] |

| Vialmix | Hardware | Contrast agent activation | Specialized medical imaging [29] |

| PyMOL | Visualization | Molecular structure visualization | Primarily 3D [25] |

| MD17 Dataset | Data Resource | Molecular dynamics trajectories | 3D (multiple conformations) [24] |

| QM9 Dataset | Data Resource | Quantum chemical properties | 3D (stable conformers) [24] |

Research Implications and Applications

Impact on Drug Discovery Workflows

The choice between 2D and 3D representations significantly influences drug discovery outcomes:

Scaffold Hopping: 3D representations enable more effective scaffold hopping by identifying structurally diverse compounds with similar biological activities based on 3D pharmacophore similarity rather than 2D topological similarity [2]. Modern AI-driven methods using 3D representations can identify novel scaffolds absent from existing chemical libraries through data-driven exploration of chemical space [2].

Property Prediction Accuracy: For quantum chemical properties and biologically relevant characteristics, 3D representations consistently outperform 2D approaches, with the advantage becoming more pronounced for stereosensitive targets and conformational-dependent properties [24] [27]. The integration of 3D information has been shown to achieve state-of-the-art results on multiple molecular property prediction benchmarks [27].

Data Efficiency: Hybrid approaches that combine 2D and 3D information demonstrate particular strength in small-data scenarios, maintaining prediction accuracy even with limited training samples [24]. The chemical intuition provided by 2D representations serves as valuable prior knowledge that enhances learning efficiency.

Figure 2: Information flow from molecular structure to research applications through 2D and 3D representations.

The comparative analysis reveals that 2D and 3D molecular representations offer complementary strengths for property prediction in drug discovery. While 2D representations provide computational efficiency and strong performance for many baseline tasks, 3D representations capture essential spatial information critical for predicting stereosensitive properties and quantum chemical characteristics. The emerging trend toward hybrid approaches that integrate both modalities demonstrates promising potential, particularly for data-efficient learning and scaffold hopping applications. As molecular representation research continues to evolve, the strategic selection of appropriate representations based on specific prediction tasks remains crucial for advancing drug discovery efficiency and accuracy.

AI-Driven Modeling: Architectures and Real-World Applications for 2D and 3D Data

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) specifically designed for 2D topological graphs have become a foundational methodology in molecular representation learning, particularly for computational chemistry and drug discovery. These architectures treat molecules as graphs where atoms represent nodes and chemical bonds represent edges, creating a natural mathematical framework for capturing molecular structure without requiring 3D spatial coordinates [30] [31]. This approach has gained significant traction because 2D molecular graphs explicitly encode the connectivity patterns and structural relationships that determine fundamental chemical properties [31] [32].

The superiority of 2D-specialized GNNs lies in their ability to perform message passing and neighborhood aggregation operations that systematically capture the topological environment of each atom within the molecular structure [33]. Unlike traditional molecular fingerprints that rely on predefined rules, GNNs automatically learn meaningful feature representations directly from the graph structure through trainable neural network layers [31]. This capability makes them particularly valuable for molecular property prediction tasks where structural motifs and functional groups determine biological activity and physicochemical characteristics [2].

Within the broader context of 2D versus 3D molecular representation research, 2D topological graphs offer distinct practical advantages: they are computationally efficient to generate and process, abundantly available in chemical databases, and sufficient for predicting many key molecular properties where 3D conformational data provides diminishing returns [32]. This review systematically evaluates the architectural innovations, performance characteristics, and practical implementation considerations of specialized 2D GNNs through experimental comparisons and methodological analysis.

Fundamental Principles and Graph Convolution Operations

2D-specialized GNNs operate on the core principle of neural message passing, where each node's representation is iteratively updated by aggregating information from its neighboring nodes [33]. This process can be expressed through a general message passing framework:

$$ hi^{(l+1)} = \sigma \left( \text{AGGREGATE} \left( \left{ \left( hi^{(l)}, hj^{(l)}, e{ij} \right) : j \in \mathcal{N}(i) \right} \right) \right) $$

Where $hi^{(l)}$ is the feature vector of node $i$ at layer $l$, $e{ij}$ represents edge features between nodes $i$ and $j$, $\mathcal{N}(i)$ denotes the neighborhood of node $i$, and $\sigma$ is a nonlinear activation function [33]. This localized aggregation process enables each node to capture increasingly broader structural contexts with each successive GNN layer, effectively learning from the graph topology.

Table: Core Components of 2D Graph Neural Network Architectures

| Component | Function | Common Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Node Features | Initial representation of each atom | Atom type, degree, hybridization, valence |

| Edge Features | Representation of chemical bonds | Bond type, conjugation, stereo-configuration |

| Aggregation Function | Combines neighbor information | Sum, mean, max, attention-weighted |

| Update Function | Updates node representations | Linear layers, GRU, residual connections |

| Readout Function | Generates graph-level predictions | Global pooling, hierarchical pooling |

Key GNN Architectures for Molecular Graphs

Several specialized GNN architectures have been developed specifically for handling molecular graph data:

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) implement a simplified neighborhood aggregation approach using normalized adjacency matrices with self-connections. The layer-wise propagation rule follows:

$$ H^{(l+1)} = \sigma \left( \tilde{D}^{-\frac{1}{2}} \tilde{A} \tilde{D}^{-\frac{1}{2}} H^{(l)} W^{(l)} \right) $$

Where $\tilde{A} = A + I$ is the adjacency matrix with self-loops, $\tilde{D}$ is the corresponding degree matrix, and $W^{(l)}$ is a trainable weight matrix [33]. GCNs strike a balance between expressive power and computational efficiency, making them one of the most widely applied architectures for molecular property prediction.

Graph Attention Networks (GATs) incorporate attention mechanisms that assign learned importance weights to different neighbors during aggregation. The attention coefficients are computed as:

$$ \alpha{ij} = \frac{\exp\left(\text{LeakyReLU}\left(\vec{a}^T [W hi \| W hj]\right)\right)}{\sum{k \in \mathcal{N}(i)} \exp\left(\text{LeakyReLU}\left(\vec{a}^T [W hi \| W hk]\right)\right)} $$

This allows the model to focus on the most structurally relevant neighbors for each molecular prediction task [33].

Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) provide a generalized framework that unifies various GNN approaches through explicit message functions. In MPNNs, messages $m_{ij}$ are passed between connected nodes using a learned message function $M$, then aggregated and used to update node states:

$$ m{ij} = M(hi, hj, e{ij}) $$

$$ hi^{(l+1)} = U \left( hi^{(l)}, \sum{j \in \mathcal{N}(i)} m{ij} \right) $$

Where $U$ is an update function [33]. This flexible framework has been particularly successful for molecular property prediction as it can explicitly incorporate bond features and molecular substructure information.

Performance Comparison of 2D GNN Architectures

Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

Comprehensive evaluation of 2D GNN architectures typically follows standardized experimental protocols using benchmark molecular datasets. The most commonly used datasets include:

- Molecular property prediction benchmarks (e.g., QM9, ESOL, FreeSolv) containing thousands of molecules with associated properties [31]

- Drug-target interaction datasets that test the models' ability to predict binding affinities [34]

- Toxicity and ADMET prediction datasets relevant to pharmaceutical applications [2]

Standard evaluation metrics include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for regression tasks, Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC) for classification tasks, and Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) for conformational analyses when comparing to 3D methods [32]. Most studies employ k-fold cross-validation with standardized data splits to ensure comparable results across different architectures.

Training typically follows either full-graph or mini-batch approaches. Recent empirical evidence indicates that mini-batch training systems consistently converge faster than full-graph training across multiple datasets and GNN models, achieving similar or often higher accuracy values [35]. This advantage persists even though mini-batch sampling introduces additional stochasticity, as the more frequent parameter updates (multiple times per epoch versus once per epoch in full-graph training) lead to faster convergence in terms of time-to-accuracy [35].

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Table: Performance Comparison of 2D GNN Architectures on Molecular Property Prediction

| Architecture | QM9 (MAE) | ESOL (MAE) | FreeSolv (MAE) | Training Efficiency (Epochs to Converge) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) | 0.89 | 0.58 | 0.37 | 125 |

| Graph Attention Network (GAT) | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.34 | 115 |

| Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) | 0.68 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 140 |

| WeaveNet | 0.72 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 135 |

| Attentive FP | 0.64 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 110 |

Performance comparisons reveal that attention-based architectures (GAT, Attentive FP) generally achieve superior predictive accuracy across diverse molecular property prediction tasks, particularly for complex properties influenced by specific molecular substructures [33]. The attention mechanism enables these models to focus on the most chemically relevant atoms and bonds when making predictions.