Validating High-Throughput Screening of MOFs for Gas Adsorption: From Computational Prediction to Laboratory Reality

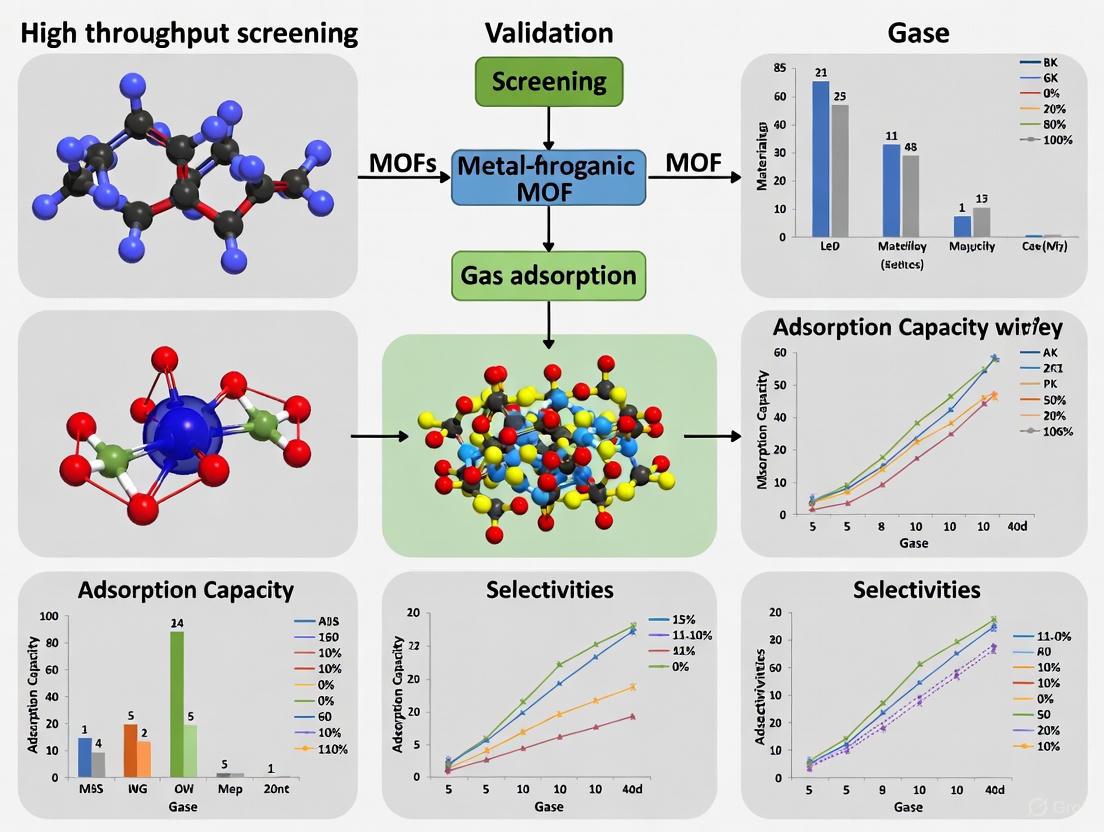

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of high-throughput computational screening (HTS) of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for gas adsorption, a critical process in carbon capture and hydrogen purification.

Validating High-Throughput Screening of MOFs for Gas Adsorption: From Computational Prediction to Laboratory Reality

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of high-throughput computational screening (HTS) of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for gas adsorption, a critical process in carbon capture and hydrogen purification. It explores the foundational principles of HTS, detailing the construction of hypothetical and experimental MOF databases. The piece critically examines the multi-stage HTS workflow, from structural characterization to molecular simulations, and introduces advanced machine learning models enhancing prediction accuracy. A significant focus is placed on troubleshooting common pitfalls, such as the trade-offs introduced by functionalization and the challenges of transitioning from in-silico to in-lab results. Finally, the article establishes robust methods for validating HTS outcomes through experimental synthesis, performance comparison, and the assessment of stability under practical conditions, offering researchers a validated pathway to discover high-performance MOFs.

The Foundation of MOF Screening: Understanding Databases and Core Principles

The Rationale for High-Throughput Screening in MOF Research

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) represent a class of porous materials with unprecedented structural tunability, formed through the coordination of metal clusters with organic ligands [1]. This versatility has positioned MOFs as promising candidates for applications ranging from gas storage and carbon capture to nuclear waste management [1] [2] [3]. However, the MOF chemical design space is immensely large, with over 90,000 structures already synthesized and over 500,000 predicted, creating an almost infinite number of potential materials [4]. This vastness presents a significant challenge for conventional discovery methods, making high-throughput computational screening (HTCS) an indispensable tool for accelerating the identification of promising MOF structures [5] [6].

The fundamental rationale for implementing HTCS in MOF research stems from the economic and practical infeasibility of experimentally testing all possible candidates for a given application [5]. HTCS enables researchers to rapidly establish quantitative structure-property relationships and identify top-performing MOFs computationally before committing resources to synthesis and experimental validation [5] [6]. This approach has evolved from small-scale studies of manually collected MOF data to the screening of hundreds of thousands of structures, ushering in a new research paradigm that combines data science with chemistry [1] [6].

Key Methodologies and Databases for MOF Screening

Primary MOF Databases for HTCS

HTCS studies rely on both experimental and hypothetical MOF databases, each with distinct characteristics and applications. The table below summarizes the key databases utilized in the field.

Table 1: Key Databases for High-Throughput Screening of MOFs

| Database Name | Type | Structures | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoRE MOF [5] [6] | Experimental | ~14,000 (2019) | Curated experimental structures from CSD with solvents removed | Gas separation, carbon capture, validation studies |

| CSD MOF Subset [6] | Experimental | ~100,000 (2020) | Quarterly-updated, automated cleaning possible | Large-scale diversity analysis, trend identification |

| hMOF [6] | Hypothetical | 137,953+ | "Bottom-up" or Tinkertoy approach with 102 SBUs | Methane storage, fundamental property studies |

| ToBaCCo [4] [6] | Hypothetical | 13,000-300,000 | "Top-down" approach focusing on topological diversity | Hydrogen storage, structure-property relationships |

| BW-DB [4] | Hypothetical | 300,000+ | Topology-based algorithm for structure generation | Chemical space exploration, adsorption studies |

| ARC-MOF [5] | Hypothetical | 15,219 | Includes computed adsorption data | CO₂ capture, stability-integrated screening |

Workflow and Geometrical Characterization

The standard HTCS workflow for MOFs follows a systematic multi-stage process as illustrated in the diagram below:

The initial stage involves structural data gathering and processing, where MOF structures are collected from databases and prepared for analysis [6]. This is followed by geometrical characterization, which computes essential structural descriptors including [6]:

- Pore Limiting Diameter (PLD): The minimum diameter through which a molecule must pass to diffuse through the framework, used to eliminate structures with insufficient pore size for target molecules [1] [6].

- Largest Cavity Diameter (LCD): The maximum cavity size within the framework, which influences adsorption capacity and selectivity [1].

- Surface Area: The internal surface area available for adsorption, typically calculated using geometric methods [1] [5].

- Pore Volume: The total volume of accessible pores within the structure [1] [5].

For gas adsorption applications, the PLD is particularly crucial for pre-screening structures, as it determines whether target molecules can access the internal pore space [1] [6]. For iodine capture, for instance, only MOFs with PLD > 3.34 Å (the kinetic diameter of I₂) are considered for further analysis [1].

Molecular Simulation and Machine Learning Approaches

Molecular simulations form the core of HTCS, with Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations being widely employed to study gas adsorption behaviors in MOFs [1]. These simulations predict adsorption uptake, selectivity, and other performance metrics under specific conditions [5] [6].

More recently, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful complement to molecular simulations [1] [2]. ML algorithms can predict MOF properties based on structural and chemical descriptors, significantly reducing computational costs [1] [3]. Key ML applications in MOF HTCS include:

- Regression models (Random Forest, CatBoost) for predicting gas adsorption capabilities [1]

- Feature importance assessment to identify critical factors governing adsorption performance [1]

- Molecular fingerprint techniques to capture comprehensive structural information [1]

- Synthesizability prediction to prioritize MOFs with higher likelihood of experimental realization [3]

In iodine capture studies, for example, ML models incorporate structural features (pore size, surface area), molecular features (metal and ligand atom types, bonding modes), and chemical features (heat of adsorption, Henry's coefficient) to achieve accurate predictions [1]. These models have revealed that Henry's coefficient and heat of adsorption are the most crucial chemical factors for iodine capture, while the presence of six-membered ring structures and nitrogen atoms in the MOF framework are key structural factors [1].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methods

Integrating Stability Metrics in Screening Protocols

A critical advancement in HTCS has been the integration of stability metrics to ensure identified MOFs are not only high-performing but also synthesizable and stable under operational conditions [5]. The diagram below illustrates a comprehensive stability-integrated screening protocol:

The four key stability metrics include:

- Thermodynamic Stability: Assessed through free energy calculations using the FL method, with an upper bound of ΔLMF ~4.2 kJ/mol relative to experimental MOFs serving as the criterion for synthetic likelihood [5].

- Mechanical Stability: Evaluated through molecular dynamics simulations to calculate elastic properties (bulk, shear, and Young's moduli), though low moduli alone do not necessarily disqualify flexible MOFs [5].

- Thermal and Activation Stabilities: Predicted using machine learning models trained on experimental data [5].

This integrated approach ensures that identified MOFs possess not only high performance but also practical viability for real-world applications [5].

Experimental Validation and Synthesis Protocols

Successful HTCS must ultimately lead to experimentally validated materials. The transition from computational prediction to synthesized MOF follows a structured protocol:

Computational Identification: Top-performing MOFs identified through HTCS are prioritized based on both performance metrics and stability considerations [5] [6]. For example, in hydrogen storage research, ML techniques can predict synthesizable MOF structures, as evidenced by the successful synthesis of a vanadium-based MOF (V₃(PET)) that exhibited excellent performance for cryogenic H₂ storage [3].

Synthesis Planning: Experimental protocols are developed based on analogous MOF structures with similar metal nodes and organic linkers [5]. The metal node chemistry significantly influences both performance and synthesizability, with certain metal nodes (e.g., V₃O₃) showing prevalence in top-performing MOFs for specific applications [5].

Characterization and Performance Validation: Synthesized MOFs undergo rigorous characterization to verify structural integrity and measure performance metrics [3] [6]. For the vanadium-based MOF identified through ML-assisted design, researchers confirmed exceptional hydrogen storage performance with total gravimetric and volumetric H₂ uptakes of 9.0 wt% and 50.0 g/L at 77 K and 150 bar, along with stability over 100 adsorption cycles [3].

Table 2: Experimental Validation Examples from HTCS Studies

| Application | Identified MOF | Performance Metrics | Validation Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Storage [3] | V₃(PET) (vanadium-based) | 9.0 wt%, 50.0 g/L at 77K/150 bar | Successfully synthesized, stable over 100 cycles |

| CO₂ Capture [5] | hMOFs with V₃O₃ nodes | CO₂ uptake ≥4 mmol/g, CO₂/N₂ selectivity ≥200 | Thermodynamically stable candidates identified |

| Methane Storage [6] | NOTT-107 | Not specified in source | Successfully synthesized and validated |

| Carbon Capture [6] | NOTT-101/Oet, VEXTUO | Not specified in source | Successfully synthesized and validated |

Implementation Guidelines and Research Toolkit

Essential Computational Tools and Reagents

The successful implementation of HTCS for MOFs requires a combination of specialized software, computational resources, and chemical building blocks. The table below details key components of the MOF researcher's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for MOF High-Throughput Screening

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software [1] | RASPA, GCMC simulations | Predict gas adsorption behaviors | Requires significant computational resources for large databases |

| Machine Learning Algorithms [1] [2] | Random Forest, CatBoost, Graph Neural Networks | Predict properties, assess feature importance | Enhanced accuracy with comprehensive feature sets |

| Structural Analysis Tools [6] | PLD/LCD calculators, surface area analysis | Characterize pore geometry and accessibility | Critical for pre-screening and structure-property relationships |

| Metal Node Chemistry [5] | V₃O₃, Zn₄O, Cu-paddlewheel, Zr₆O₆ | Determine framework stability and adsorption sites | V₃O₃ particularly effective for CO₂ adsorption |

| Organic Linkers [1] [4] | Nitrogen-containing rings, oxygen-functionalized | Provide complementary adsorption sites to metals | Six-membered ring structures enhance iodine adsorption |

| Stability Assessment Tools [5] | Molecular dynamics (MD) for elastic properties, ML models for thermal stability | Evaluate practical viability of MOFs | Essential for transitioning from hypothetical to experimental |

Best Practices for Effective HTCS Implementation

Based on successful case studies and methodological advances, several best practices emerge for implementing HTCS in MOF research:

Database Selection and Integration: Choose databases aligned with research objectives, considering that hypothetical databases (hMOF, ToBaCCo) offer greater structural diversity while experimental databases (CoRE, CSD) provide synthesizable structures with known protocols [6]. Combining multiple databases can mitigate individual biases and improve coverage of chemical space [4].

Multi-stage Screening Approach: Implement sequential screening filters to manage computational costs, beginning with geometric descriptors (PLD, LCD) to eliminate inaccessible structures, followed by molecular simulations for promising candidates, and finally stability assessments for top performers [5] [6].

Diversity-Conscious Sampling: Actively address biases in MOF databases by analyzing chemical diversity metrics, including variety, balance, and disparity [4]. This is particularly important for metal node diversity, as hypothetical databases often have surprisingly low variety in metal centers compared to experimental databases [4].

Hybrid AI-Simulation Framework: Combine molecular simulations with machine learning to maximize efficiency and insight [1] [2]. ML models can rapidly predict properties for large datasets, while simulations provide physical accuracy and detailed mechanistic understanding [1].

Stability-Performance Balance: Integrate stability metrics early in the screening process to avoid identifying high-performing but impractical MOFs [5]. The sequence of screening steps can be adjusted based on computational cost, with stability assessment following performance screening or vice versa [5].

These protocols and guidelines provide a robust foundation for leveraging HTCS to accelerate the discovery and development of MOF materials for gas adsorption and related applications, ultimately bridging the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization.

The discovery and development of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for gas adsorption applications have been significantly accelerated by the creation of large-scale databases. These collections generally fall into two categories: hypothetical databases (containing computationally generated structures) and experimentally-derived databases (containing structures confirmed through laboratory synthesis). Understanding the composition, strengths, and limitations of each type is crucial for validating high-throughput screening (HTS) in gas adsorption research, as the choice of database directly impacts the predictive accuracy and experimental relevance of computational findings [7] [1].

Database Classifications and Characteristics

Hypothetical MOF Databases

Hypothetical databases are constructed in silico using computational assembly methods. They are built by systematically combining known inorganic building blocks (metal clusters or secondary building units) and organic linkers according to established topological blueprints [7].

Construction Methodology: The process often employs topologically based crystal construction (ToBaCCo) software. This method uses two key inputs:

- Topological blueprints that define the coordination environment and symmetry of building blocks as periodic abstract nets.

- Molecular building blocks (MBBs) comprising functionalized organic linkers and metal nodes [7].

A prominent example from recent literature involves generating a database of 4,797 MOFs by integrating 10 metal centers with 144 functionalized ligands (18 ligands modified by –NH₂, –NO₂, –CH₃, –CF₃, –SH₂, –SO₂, –OH, and –OLi) across 36 topologies [7]. This approach allows for the systematic exploration of structure-property relationships across a vast chemical space.

Experimentally-Derived MOF Databases

Experimentally-derived databases curate structures that have been synthesized and characterized in laboratories. These databases serve as a critical benchmark for validating hypothetical screening results.

A widely used resource is the CoRE MOF (Computation-Ready, Experimental Metal-Organic Framework) database. For instance, a 2014 version of the CoRE MOF database was used in a study screening 1,816 structures for iodine capture, selected based on the criterion that their pore limiting diameter (PLD) was greater than 3.34 Å (the kinetic diameter of I₂) [1]. These databases provide a realistic representation of synthetically accessible and stable frameworks.

Table 1: Comparison of Hypothetical and Experimentally-Derived MOF Databases

| Feature | Hypothetical Databases | Experimentally-Derived Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Computationally generated via assembly algorithms [7] | Curated from experimentally synthesized and characterized structures (e.g., CoRE MOF 2014) [1] |

| Size & Diversity | Very large (e.g., 4,797+ structures); high chemical and topological diversity [7] | Smaller (e.g., 1,816 structures); limited to what has been successfully synthesized [1] |

| Primary Strength | Explores vast, untapped chemical space; ideal for identifying novel candidate materials with exceptional predicted performance [7] | High synthetic realism; provides direct validation of stability and properties under real-world conditions [1] |

| Main Limitation | May include structures that are synthetically inaccessible or unstable [7] | Covers a smaller fraction of the possible MOF chemical space [1] |

| Typical Use in HTS | Primary screening for identifying top-performing candidates and establishing structure-property relationships [7] | Validation of screening results and assessment of synthetic feasibility and stability [1] |

Experimental Protocols for High-Throughput Screening

The following protocols detail the standard computational methodologies used for high-throughput screening of MOF databases for gas adsorption.

Protocol 1: Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) Simulations for Gas Adsorption

Purpose: To predict the gas adsorption capacity and selectivity of MOF structures at equilibrium conditions.

Principle: GCMC simulations mimic an open system in equilibrium with a reservoir of particles at a given chemical potential, temperature, and volume, which is appropriate for modeling adsorption from a bulk gas phase [1].

Methodology:

- Structure Preparation: Obtain the MOF structure from the database. For experimentally-derived structures, remove solvent molecules from the pores to create a "computation-ready" model while preserving the framework atoms and connectivity [1].

- Energy Calculation: Define the interaction energies between the adsorbate molecules (e.g., CO₂, I₂, H₂O) and the MOF framework. This is typically done using a classical forcefield, where the total interaction energy is the sum of van der Waals (e.g., described by a Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic (e.g., described by Coulomb's law) interactions.

- Simulation Setup:

- Ensemble: Use the grand canonical (μVT) ensemble.

- Temperature: Set the simulation temperature (e.g., 298 K).

- Fugacity/Bulk Pressure: Set the fugacity of the adsorbing gas, which is derived from the specified bulk pressure.

- Steps: Perform a minimum of 2-3 million simulation steps to ensure proper equilibration, followed by an additional 2-3 million steps for production and data collection.

- Output Analysis: The primary output is the ensemble-averaged number of adsorbed molecules per unit cell or per gram of MOF at the specified conditions, giving the adsorption capacity. For gas mixtures (e.g., CO₂/N₂ or I₂/H₂O), the adsorption selectivity can be calculated from the ratio of the uptakes of the different components [1].

Protocol 2: Calculating Key Performance Metrics

Purpose: To evaluate and rank MOF materials based on multiple criteria relevant to practical application.

Methodology:

- Working Capacity (ΔN): The difference in adsorption capacity between the adsorption and desorption conditions. For a pressure-swing adsorption process, this is often calculated as ΔN = N(Pads) - N(Pdes), where N is the loading and P is pressure [7].

- Adsorption Selectivity (Sads): For a binary gas mixture (A and B), the selectivity of component A over B is defined as Sads(A/B) = (xA / xB) / (yA / yB), where xi is the mole fraction in the adsorbed phase and yi is the mole fraction in the bulk gas phase [7].

- Henry's Coefficient (KH): Calculated in the limit of zero pressure from GCMC simulations or via Widom's particle insertion method. A lower KH value for a competing gas (like H₂O) can indicate an advantage in selective adsorption of the target gas (like I₂) in humid environments [1].

- Heat of Adsorption (Q_st): The isosteric heat of adsorption is calculated from fluctuations in the number of adsorbed molecules and the system energy during the GCMC simulation. It quantifies the strength of the interaction between the framework and the adsorbate [7].

An Integrated Workflow for Database Navigation and Validation

The effective use of MOF databases requires a structured workflow that leverages the strengths of both hypothetical and experimental collections. The diagram below outlines this integrated process.

Integrated Workflow for MOF Database Navigation and Validation

Validation Through Interpretable Machine Learning

Machine learning (ML) bridges high-throughput computational screening and experimental validation by identifying key performance descriptors and extracting design principles from large datasets [1].

Workflow and Key Insights:

- Feature Engineering: A robust ML model requires comprehensive descriptors:

- Structural Features: Pore Limiting Diameter (PLD), Largest Cavity Diameter (LCD), void fraction (φ), surface area, pore volume, and density [1].

- Chemical Features: Henry's coefficient and isosteric heat of adsorption, which have been identified as crucial factors for predicting iodine adsorption performance [1].

- Molecular Features: Atom types (e.g., C, N, O, metal species), their hybridization states (e.g., C1, C2, C3, CR), and bonding modes within the MOF framework [1].

- Model Training and Interpretation: Algorithms like Random Forest and CatBoost are trained to predict adsorption performance. These models can then be interrogated to assess feature importance, revealing which structural or chemical properties most significantly influence adsorption. For example, in iodine capture, Henry's coefficient and heat of adsorption to iodine are identified as the two most critical chemical factors [1].

- Molecular Fingerprinting: This technique provides granular structural insights. For instance, screening studies have revealed that the presence of six-membered ring structures and nitrogen atoms in the MOF framework are key structural factors that enhance iodine adsorption, followed by the presence of oxygen atoms [1].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions - Essential Computational Tools and Databases

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to MOF Research |

|---|---|---|

| ToBaCCo Software | Topologically Based Crystal Construction; generates hypothetical MOF structures by assembling molecular building blocks into predefined network topologies [7]. | Enables the systematic construction of large, diverse hypothetical MOF databases for high-throughput screening. |

| RASPA Software | A powerful molecular simulation package for performing Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC), Molecular Dynamics, and other computational chemistry calculations [1]. | The standard tool for simulating gas adsorption equilibria and dynamics in porous materials like MOFs. |

| CoRE MOF Database | A curated collection of Computation-Ready, Experimental MOF structures, derived from the Cambridge Structural Database, with solvent molecules removed [1]. | Provides a reliable set of experimentally realized structures for screening validation and model training. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms (e.g., CatBoost, Random Forest) | Advanced regression algorithms used to predict material properties based on input features and to decipher complex structure-property relationships [1]. | Accelerates the discovery process by predicting performance and identifying critical descriptors from HTS data. |

Navigating the landscape of MOF databases requires a strategic approach that acknowledges the complementary roles of hypothetical and experimentally-derived collections. Hypothetical databases are powerful for mapping the outer limits of performance and discovering novel design principles, while experimental databases provide an essential anchor in synthetic reality. The validation of high-throughput screening outcomes hinges on a multi-faceted protocol that integrates computational predictions (via GCMC and performance metrics) with validation against known experimental structures and interpretable machine learning. This integrated workflow, which leverages the strengths of both database types, provides a robust and profound framework for accelerating the reliable discovery and targeted design of high-performance MOF adsorbents for gas separation and capture applications.

In metal-organic framework (MOF) research, high-throughput computational screening (HTCS) has become an indispensable technique for efficiently evaluating the gas adsorption performance of thousands of materials. This approach relies on well-established performance metrics that enable researchers to rank MOFs and identify promising candidates for specific separation processes. The integration of molecular simulations with performance metric evaluation allows for systematic assessment of MOFs before resource-intensive experimental synthesis and testing [8] [9].

The validation of HTCS methodologies depends critically on accurate quantification of key adsorbent properties, primarily gas uptake capacity, selectivity, and working capacity. These metrics provide the fundamental basis for comparing materials across different studies and predicting their performance in industrial applications such as carbon capture, hydrogen purification, and odorant removal [10] [9]. Recent research has emphasized that while these core metrics are essential, comprehensive screening must also consider additional factors including energy efficiency, framework stability, and performance under realistic process conditions [7] [5] [11].

Table 1: Core Performance Metrics for MOF Adsorbent Evaluation

| Metric | Definition | Significance | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Uptake | Amount of gas adsorbed at equilibrium conditions | Indicates maximum adsorption capacity | mmol/g or mol/kg |

| Selectivity | Ability to preferentially adsorb one gas over another | Determines separation efficiency | Dimensionless ratio |

| Working Capacity | Reversible adsorption capacity between adsorption and desorption conditions | Reflects regenerability and cyclic performance | mmol/g or mol/kg |

| Adsorbent Performance Score (APS) | Combined metric incorporating selectivity and working capacity | Provides balanced performance assessment | Dimensionless |

| Regenerability (R%) | Percentage of adsorbed gas that can be desorbed | Indicates ease of adsorbent regeneration | Percentage |

Fundamental Adsorption Metrics

Gas Uptake Capacity

Gas uptake capacity represents the fundamental measure of an adsorbent's ability to retain gas molecules within its porous structure. This metric is typically quantified through grand canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations, which calculate the equilibrium adsorption amount at specific temperature and pressure conditions [8] [1]. For carbon capture applications, high CO₂ uptake is particularly valuable, with top-performing MOFs demonstrating capacities up to 8.47 mmol/g under flue gas conditions [5].

The evaluation of gas uptake must consider the operational context. For example, in pre-combustion CO₂ capture where gas mixtures contain 15-40% CO₂ at elevated pressures (up to 40 bar), uptake capacity at these specific conditions becomes more relevant than single-component adsorption at standard temperature and pressure [9]. Studies screening over 10,000 MOFs have revealed that uptake capacity alone is insufficient for predicting overall process efficiency, as it does not account for the energy required for adsorbent regeneration [11].

Selectivity

Selectivity measures a material's ability to preferentially adsorb one component from a gas mixture, fundamentally determining its separation capability. Adsorption selectivity (Sₐdₛ) is typically calculated as the ratio of the adsorption capacities of two gases, often derived from IAST (Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory) predictions based on single-component isotherms [9]. For CO₂/N₂ separation in flue gas applications, selectivity values can range dramatically, with functionalized MOFs showing particularly significant enhancements—for instance, –NO₂, –SO₂, and –OLi functional groups increasing selectivity from 24.94/40.36 (pristine) to 121.11/176.87, 149.94/215.54, and 58.64/267.44, respectively [7].

Selectivity metrics must be interpreted within the context of the specific gas mixture and conditions. For CO₂/H₂ separation in pre-combustion capture, selectivity values above 60 are considered promising, while for post-combustion CO₂ capture from N₂, higher selectivity values are often required due to the lower concentration of CO₂ in the feed stream [9].

Working Capacity

Working capacity (ΔN), also termed reversible adsorption capacity, represents the cyclable adsorption amount between adsorption and desorption conditions. This metric crucially links molecular-level adsorption properties with process-level performance, as it quantifies the usable capacity during cyclic separation processes like pressure swing adsorption (PSA), vacuum swing adsorption (VSA), or temperature swing adsorption (TSA) [8].

Functionalization strategies can dramatically enhance working capacity. Recent high-throughput screening of 4,797 functionalized MOFs demonstrated that –NO₂, –SO₂, and –OLi functional groups increase CO₂ working capacity from 2.34 mmol/g (pristine) to 5.91-7.94 mmol/g [7]. The critical importance of working capacity lies in its direct impact on process economics—higher working capacities reduce the required adsorbent inventory, leading to more compact and cost-effective separation systems.

Integrated Performance Assessment

Composite Metrics

While individual metrics provide valuable insights, composite metrics that combine multiple performance aspects offer more comprehensive material assessments. The Adsorbent Performance Score (APS) integrates both selectivity and working capacity into a single value, enabling more balanced ranking of materials [8]. Similarly, the Sorbent Selection Parameter (Ssp) provides another combined metric that has shown strong correlation with process-level performance indicators [7].

Recent research has introduced more sophisticated evaluation frameworks, such as the energy efficiency (η) metric, which holistically evaluates both adsorption performance (Sₐdₛ, ΔN, APS, Ssp, and R) and energy inputs (desorption heat, pressure-swing energy, net loss) [7]. This approach resolves critical trade-offs between competing functional groups, identifying –SO₂ as the optimal functional group that balances exceptional CO₂ capture (η = 6.17/12.78 for CO₂ over CH₄/N₂) with reasonable energy requirements [7].

Stability Considerations

Comprehensive MOF validation must extend beyond adsorption metrics to include stability considerations. Integrating thermodynamic, mechanical, thermal, and activation stability metrics with high-throughput screening ensures identified materials are not only high-performing but also synthesizable and durable under process conditions [5]. Evaluation of 148 top-performing hypothetical MOFs revealed that 41 structures were thermodynamically unstable despite excellent adsorption properties, highlighting the critical importance of stability assessment [5].

Diagram 1: HTCS Validation Workflow for MOFs

Experimental Protocols for Metric Validation

High-Throughput Computational Screening Protocol

Objective: To systematically screen large MOF databases for gas adsorption performance using molecular simulations.

Materials and Methods:

- MOF Databases: Utilize computation-ready experimental MOF databases (CoRE MOF 2019, CSD non-disordered MOF subset) or hypothetical MOF databases [12] [5]

- Software Tools: Employ specialized software for structural analysis (Zeo++), molecular simulations (RASPA), and process modeling [1] [9]

- Simulation Parameters:

- Perform Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations for gas adsorption

- Use validated force fields (e.g., UFF, DREIDING) with appropriate partial charge assignment methods

- Simulate gas mixtures at relevant industrial conditions (temperature, pressure, composition)

Procedure:

- Database Curation: Remove solvent molecules, add missing hydrogen atoms, and treat charge-balancing ions appropriately [12]

- Structural Characterization: Calculate pore limiting diameter (PLD), largest cavity diameter (LCD), accessible surface area, and pore volume [5]

- Single-Component Adsorption: Simulate pure gas adsorption isotherms for all relevant gases

- Mixture Adsorption: Compute binary or ternary mixture adsorption using GCMC or IAST predictions

- Metric Calculation: Derive uptake, selectivity, working capacity, and composite metrics from simulation data

- Material Ranking: Rank materials based on selected performance metrics for the target application

Validation Steps:

- Compare IAST predictions with explicit mixture GCMC simulations for selected top performers [9]

- Verify mechanical stability through molecular dynamics simulations [5]

- Assess thermodynamic stability through free energy calculations [5]

Functionalized MOF Evaluation Protocol

Objective: To assess the impact of functional groups on MOF adsorption performance.

Materials:

- Base MOF Structures: Select MOFs with diverse topologies and metal centers

- Functional Groups: Include –NH₂, –NO₂, –CH₃, –CF₃, –SH₂, –SO₂, –OH, and –OLi for systematic comparison [7]

Procedure:

- Database Construction: Generate functionalized MOF structures through systematic modification of organic ligands [7]

- High-Throughput Screening: Perform GCMC simulations for all functionalized structures

- Performance Evaluation: Calculate key metrics including Sₐdₛ, ΔN, APS, Ssp, and R

- Energy Analysis: Compute isosteric heats of adsorption and energy efficiency metrics [7]

- Trade-off Assessment: Identify optimal functional groups that balance adsorption performance with energy requirements

Table 2: Performance of Functionalized MOFs for CO₂ Capture

| Functional Group | CO₂ Working Capacity (mmol/g) | CO₂/N₂ Selectivity | Isosteric Heat (kJ/mol) | Energy Efficiency (η) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine | 2.34 | 40.36 | - | 2.18 |

| –NO₂ | 5.91-7.94 | 176.87 | -29.15 | 8.80 |

| –SO₂ | 5.91-7.94 | 215.54 | -29.96 | 12.78 |

| –OLi | 5.91-7.94 | 267.44 | -30.09 | - |

| –CF₃ | 5.91-7.94 | - | - | 8.80 |

Advanced Considerations in Metric Validation

Process-Informed Performance Assessment

Traditional adsorption metrics increasingly show limitations in predicting actual process performance. Recent studies demonstrate that materials with exceptional uptake capacities may exhibit high energy penalties during regeneration [11]. Comprehensive validation requires process-informed assessments that translate molecular-level adsorption properties to system-level performance indicators.

The parasitic energy of separation has emerged as a crucial metric that correlates strongly with process economics [8] [11]. Screening studies incorporating process simulations reveal that rankings based on parasitic energy often differ significantly from those based solely on APS and regenerability, highlighting the importance of process-aware validation [8]. For CO₂ capture applications, materials must simultaneously achieve ≥95% CO₂ purity and ≥90% recovery while minimizing energy consumption [11].

Performance Under Realistic Conditions

Material validation must account for realistic operating environments, including the presence of water vapor and other contaminants. Performance metrics obtained under idealized dry conditions often overestimate actual separation capabilities [11]. Comprehensive screening should incorporate:

- Humidity Effects: Evaluate performance under relevant relative humidity conditions (e.g., 40% RH for flue gas) [11]

- Chemical Stability: Assess structural integrity and performance retention after exposure to acidic gases and water vapor

- Cyclic Stability: Verify consistent performance over multiple adsorption-desorption cycles

Studies examining CO₂ capture under humid conditions (40% relative humidity) have identified that MOFs with narrow, straight 1D channels often maintain superior performance, with hundreds of MOFs retaining 90% of their dry CO₂ capture capacity [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| MOF Databases | CoRE MOF 2019, CSD non-disordered MOF subset, ARC-MOF | Provide computation-ready MOF structures for screening studies [12] [5] |

| Simulation Software | RASPA, Zeo++, ToBaCCo | Perform molecular simulations, structural analysis, and database generation [7] [1] |

| Process Modeling Tools | MAPLE (Machine Learning-Accelerated Process Model) | Rapid optimization of adsorption process conditions and energy consumption [11] |

| Functional Groups | –NO₂, –SO₂, –OLi, –CF₃, –NH₂ | Enhance selective CO₂ adsorption via tailored host-guest interactions [7] |

| Performance Metrics | APS, Ssp, η, Parasitic Energy | Quantify and compare overall adsorbent performance from different perspectives [7] [8] |

| Stability Assessment Tools | Molecular dynamics simulations, ML stability predictors | Evaluate synthesizability and durability under process conditions [5] |

The validation of high-throughput screening for MOF-based gas adsorption research requires a multifaceted approach that integrates fundamental adsorption metrics with advanced process-aware evaluations. While gas uptake, selectivity, and working capacity form the essential foundation for initial material assessment, comprehensive validation must extend to include energy efficiency, stability under realistic conditions, and actual process performance. The development of sophisticated composite metrics and the integration of molecular simulations with process optimization represent significant advances in the field. As MOF databases continue to expand and computational methods improve, the validation frameworks outlined in this protocol will enable more reliable identification of promising adsorbents, ultimately accelerating the development of advanced separation materials for critical environmental and industrial applications.

In high-throughput computational screening (HTCS) of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for gas adsorption applications, structural descriptors provide the fundamental link between atomic-level architecture and macroscopic performance. Pore Limiting Diameter (PLD), Largest Cavity Diameter (LCD), and Surface Area have emerged as three critical parameters that efficiently predict adsorption behavior across diverse gas capture scenarios. These descriptors enable researchers to rapidly evaluate thousands of MOF structures by quantifying key aspects of their porous environments that govern host-guest interactions. The predictive power of these parameters extends across various applications, including carbon capture, hydrocarbon separation, and radioactive iodine removal, making them indispensable tools for accelerating adsorbent discovery and optimization [1] [7].

The integration of these structural descriptors with machine learning approaches has created a powerful paradigm for MOF research. By establishing quantitative structure-property relationships (QSPRs), scientists can navigate the vast chemical space of possible MOF structures with targeted precision. This approach moves beyond trial-and-error methodologies toward rational design principles, significantly reducing the time and resources required to identify promising candidates for specific gas separation challenges [1].

Defining the Key Structural Descriptors

Pore Limiting Diameter (PLD) and Largest Cavity Diameter (LCD)

Pore Limiting Diameter (PLD) represents the diameter of the largest sphere that can diffusive through the framework, defining the accessibility of the porous network. Largest Cavity Diameter (LCD) refers to the diameter of the largest sphere that can be accommodated within the pore cavities, determining the available space for guest molecule accommodation. These parameters are typically calculated using specialized software such as Zeo++ [13].

The relationship between PLD and kinetic diameter of probe molecules determines molecular accessibility. For example, in iodine capture applications, researchers typically select MOFs with PLD > 3.34 Å (the kinetic diameter of I₂) to ensure iodine molecules can enter the porous structure [1]. Similarly, for CO₂ capture applications (CO₂ kinetic diameter = 3.3 Å), MOF candidates with PLD below this threshold are often eliminated from consideration [7].

Surface Area

Surface Area quantifies the total available surface within a MOF that can interact with guest molecules, typically measured in m²/g. This parameter directly influences the capacity of a MOF to physisorb gas molecules, with higher surface areas generally correlating with greater potential adsorption capacity. Surface area calculations for MOFs are commonly derived from nitrogen adsorption isotherms at 77K using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method [14].

Quantitative Relationships Between Structural Descriptors and Adsorption Performance

Iodine Capture in Humid Environments

Recent research has established precise optimal ranges for structural descriptors in iodine capture applications. A comprehensive study screening 1,816 MOFs revealed clear relationships between structural parameters and iodine adsorption performance under humid conditions [1].

Table 1: Optimal Structural Descriptor Ranges for Iodine Capture

| Structural Descriptor | Optimal Range | Performance Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Largest Cavity Diameter (LCD) | 4.0 - 7.8 Å | Maximum capacity and selectivity observed between 4-5.5 Å; steric hindrance below 4 Å; diminished host-guest interaction above 7.8 Å |

| Pore Limiting Diameter (PLD) | 3.34 - 7.0 Å | Must exceed I₂ kinetic diameter (3.34 Å); optimal performance in narrower range |

| Void Fraction (φ) | 0 - 0.17 | Peak performance at φ = 0.09; decreasing performance up to φ = 0.6 |

| Density | ~0.9 g/cm³ | Increasing density promotes adsorption sites up to 0.9 g/cm³; steric hindrance dominates above this value |

| Surface Area | 0 - 540 m²/g | Higher values within this range generally improve performance |

| Pore Volume | 0 - 0.18 cm³/g | Moderate values optimize confinement effects |

The study demonstrated that MOFs with LCD between 4-5.5 Å provide ideal confinement for iodine molecules, balancing reduced steric hindrance with maintained strong host-guest interactions. When LCD exceeds 5.5 Å, the adsorption interaction diminishes, leading to increased I₂ desorption [1].

CO₂ Capture Applications

In CO₂ capture applications, structural descriptors help identify MOFs that balance high selectivity with efficient regeneration. Research screening 4,797 functionalized MOFs has revealed how strategic functionalization (–NO₂, –SO₂, –OLi) enhances CO₂ capture performance while maintaining structural integrity [7].

Table 2: Structural Descriptor Impact on CO₂ Capture Performance

| Performance Metric | Pristine MOFs | Functionalized MOFs | Key Structural Influences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Capacity (ΔN) | 2.34 mmol g⁻¹ | 5.91-7.94 mmol g⁻¹ | Optimized PLD (≥3.3 Å) combined with polar functional groups |

| CO₂/N₂ Selectivity | 40.36 | 58.64-267.44 | Surface chemistry and LCD balancing molecular sieving |

| Renewability (R) | Baseline | ~50% reduction | Stronger CO₂ affinity increases regeneration energy |

| Energy Efficiency (η) | 2.18 | 4.74-12.78 | Optimal balance of surface area, functional groups, and pore size |

The introduction of polar functional groups (–NO₂, –SO₂, –OLi) dramatically enhances CO₂ selectivity but comes with a trade-off in renewability due to stronger guest interactions that require more energy for desorption [7].

Experimental Protocols for Descriptor Determination

Computational Determination of PLD and LCD

Protocol Title: Calculating Pore Size Descriptors Using Zeo++ Software

Principle: Geometric analysis of the crystal structure to determine the maximum sphere diameters for cavity occupation (LCD) and framework diffusion (PLD).

Materials and Reagents:

- MOF crystal structure file (.cif format)

- Zeo++ software (version 0.3 or higher)

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation: Obtain high-quality crystal structures from databases (Cambridge Structural Database, CoRE MOF 2014) or DFT-optimized coordinates.

- File Conversion: Convert structure files to .cssr format if necessary using Zeo++ utilities.

- Probe Radius Setting: Define appropriate van der Waals radii for atoms (typically 1.2Å for C, 1.5Å for O, 1.8Å for metal atoms).

- PLD Calculation: Execute Zeo++ with -res flag to determine pore limiting diameter:

network -res MOF_structure.cssr - LCD Calculation: Execute Zeo++ with -ha flag for largest cavity diameter:

network -ha MOF_structure.cssr - Result Validation: Cross-check results with multiple probe sizes to ensure accuracy.

Notes: For MOFs with flexible frameworks, perform calculations on both experimental and DFT-optimized structures to account for structural changes during adsorption [15] [13].

Surface Area Determination Methods

Protocol Title: Surface Area Calculation from Gas Adsorption Isotherms

Principle: Physical adsorption of gas molecules (N₂ at 77K) on the MOF surface with subsequent application of BET theory to calculate specific surface area.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-purity MOF sample (≥50 mg)

- Nitrogen gas (99.999% purity)

- Surface area analyzer (e.g., Micromeritics, Quantachrome)

- Degassing station

Procedure:

- Sample Activation: Degas MOF sample under vacuum at 150°C for 12 hours to remove solvent molecules.

- Isotherm Measurement: Collect N₂ adsorption-desorption isotherm at 77K across relative pressure (P/P₀) range of 0.01-0.99.

- BET Range Selection: Identify linear region in P/P₀ range of 0.05-0.30 for BET plot.

- BET Calculation: Apply BET equation to determine monolayer capacity and calculate surface area using cross-sectional area of N₂ molecule (16.2 Ų).

- Pore Size Distribution: Apply DFT methods to low-pressure CO₂ adsorption isotherms (273K) to characterize micropore volume.

Notes: For absolute methane adsorption characterization, combine BET surface area with pore volume measurements to determine adsorbed phase volume [14].

Integration with Machine Learning and High-Throughput Screening

Machine Learning Workflow for MOF Screening

The combination of structural descriptors with machine learning algorithms has dramatically accelerated the discovery of high-performance MOFs. Research demonstrates that Random Forest and CatBoost regression algorithms can effectively predict gas adsorption performance when trained on comprehensive descriptor sets including PLD, LCD, and surface area [1].

Feature Importance Analysis reveals that while structural descriptors provide fundamental insights, chemical features such as Henry's coefficient and heat of adsorption often demonstrate higher predictive power for specific gas adsorption performance. Molecular fingerprints further enhance prediction accuracy by capturing complex structural motifs, with six-membered ring structures and nitrogen atoms in the MOF framework identified as key structural features enhancing iodine adsorption [1].

Advanced Screening Protocol

Protocol Title: High-Throughput Screening Integrating Force Fields and Machine-Learned Potentials

Principle: Hybrid screening strategy merging classical force fields (UFF) for initial efficiency with universal machine-learned interatomic potentials (PFP) for accuracy refinement.

Materials and Computational Resources:

- Curated MOF database (e.g., CoRE MOF 2014)

- Molecular simulation software (RASPA)

- Universal machine-learned interatomic potentials (PFP)

- High-performance computing cluster

Procedure:

- Initial Screening: Perform Widom insertion Monte Carlo simulations using Universal Force Field (UFF) for rapid evaluation of gas uptake.

- Candidate Selection: Identify top-performing MOF candidates (e.g., top 5-10%) based on UFF predictions.

- Refined Screening: Re-evaluate promising candidates using PreFerred Potential (PFP) u-MLIP for near-quantum accuracy.

- Framework Flexibility: Account for guest-induced structural changes through full unit cell relaxation.

- Performance Validation: Benchmark against DFT calculations to validate adsorption predictions.

- Multi-Metric Evaluation: Assess candidates using combined metrics (selectivity, working capacity, energy efficiency).

Notes: This approach has proven particularly valuable for identifying MOFs with optimal pore sizes and high target gas affinity while accounting for competitive adsorption in humid conditions [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for MOF Structural Characterization and Screening

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeo++ | Software | Pore structure analysis | PLD and LCD calculation from crystal structures |

| RASPA | Software | Molecular simulation | GCMC simulations for gas adsorption prediction |

| VASP | Software | Density functional theory | Electronic structure calculation and geometry optimization |

| ToBaCCo | Software | Database construction | Topology-based generation of hypothetical MOFs |

| Universal Force Field (UFF) | Computational Method | Classical molecular simulation | Rapid initial screening of gas adsorption |

| PreFerred Potential (PFP) | Computational Method | Machine-learned potential | High-accuracy adsorption energy calculation |

| Cambridge Structural Database | Database | Experimental crystal structures | Source of validated MOF structures for screening |

| CoRE MOF 2014 | Database | Curated MOF structures | Benchmark set for high-throughput screening studies |

Structural descriptors PLD, LCD, and surface area continue to serve as fundamental parameters in high-throughput screening of MOFs for gas adsorption applications. Their quantitative relationship with adsorption performance enables efficient navigation of the vast MOF design space, particularly when integrated with machine learning approaches. Future developments will likely focus on dynamic descriptor analysis that accounts for framework flexibility and guest-induced structural changes, moving beyond static crystal structures to more accurately represent operational conditions. The continued refinement of computational protocols, combining the efficiency of classical force fields with the accuracy of machine-learned potentials, promises to further accelerate the discovery of next-generation adsorbents for critical separation challenges.

Executing a Screening Workflow: From Simulation to AI-Driven Discovery

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) represents a paradigm shift in the discovery and development of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for gas adsorption applications. Faced with a virtually unlimited chemical design space—with approximately one million hypothesized and synthesized MOFs—traditional experimental methods are rendered infeasible due to time and cost constraints [16]. Computational HTS provides a systematic, rapid, and cost-effective alternative, enabling researchers to efficiently navigate this vast materials space by leveraging molecular simulations, data-driven modeling, and advanced computational algorithms. This protocol outlines the standard HTS workflow, detailing each critical step from database construction to the identification of top-performing MOF candidates, specifically within the context of validating MOFs for gas adsorption research.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools and Databases for HTS of MOFs.

| Item Name | Type | Description | Key Function in HTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoRE MOF Database [16] [1] | Database | A collection of experimentally synthesized MOF structures, curated for computational readiness. | Provides reliable, experimentally-validated structures for screening and model validation. |

| ToBaCCo [16] [7] [17] | Software/Database | Topologically Based Crystal Constructor; a code for generating hypothetical MOFs from building blocks and topological blueprints. | Enables systematic construction of vast hypothetical MOF databases for screening. |

| hMOF Database [16] | Database | A database of hypothetical MOFs generated via computational assembly of building blocks. | Expands the explorable materials space beyond experimentally synthesized MOFs. |

| UFF4MOF [18] | Classical Force Field | A universal force field parametrized for MOFs. | Models atomistic interactions and energies for rapid molecular simulations. |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) [18] | Computational Model | Force fields (e.g., CHGNet, MACE-MP-0) trained on quantum mechanical data using machine learning. | Provides higher accuracy modeling of framework flexibility and adsorbate interactions approaching DFT quality. |

| Uni-MOF Framework [17] | Deep Learning Model | A transformer-based model pre-trained on massive structural data for multi-task gas adsorption prediction. | Predicts adsorption capacities across diverse gases and conditions using only CIF files, bypassing expensive simulations. |

Methodology

The Standard HTS Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential, multi-stage process of a standard High-Throughput Screening campaign for MOFs.

Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Database Curation and Generation

Objective: To assemble a comprehensive and computationally-ready set of MOF structures for screening.

Procedure:

- Acquire Experimentally-Synthesized MOFs: Source structures from curated databases such as the Computation-Ready, Experimental (CoRE) MOF database [16] [1] or the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [16]. These provide Crystallographic Information Files (CIFs) containing atomic coordinates and unit cell dimensions.

- Generate Hypothetical MOFs: Use software like the Topologically Based Crystal Constructor (ToBaCCo) to systematically create hypothetical MOFs (hMOFs) [16] [7].

- Input: Define a library of:

- Output: A large database of structurally diverse MOFs. For example, one study generated 4,797 MOFs from 10 metal centers and 144 functionalized ligands across 36 topologies [7].

Step 2: Structural Pre-Screening

Objective: To filter out non-viable structures to reduce computational cost in subsequent, more expensive steps.

Procedure:

- Calculate key geometric descriptors for every MOF in the database:

- Pore Limiting Diameter (PLD): The diameter of the largest sphere that can diffuse through the framework.

- Largest Cavity Diameter (LCD): The diameter of the largest cavity in the framework.

- Void Fraction (φ) / Pore Volume: The fraction of the crystal volume not occupied by atoms.

- Surface Area (SA): Typically the Langmuir or Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area.

- Apply exclusion criteria. For a target gas with a known kinetic diameter (e.g., CO₂: ~3.3 Å, I₂: ~3.34 Å), remove all MOFs with a PLD smaller than this value, as the gas cannot access the pores [7] [1]. Also, remove structures with non-positive surface area [7].

Step 3: Molecular Simulation

Objective: To accurately predict the gas adsorption behavior of the pre-screened MOFs.

Procedure:

- Select a Simulation Method:

- Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC): The most common method for predicting gas adsorption equilibria (uptake capacity) in porous materials [1]. It is well-suited for calculating adsorption isotherms.

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): Used for calculating electronic properties and accurate adsorption energies, especially for chemisorption or open-metal site interactions [16] [19]. It is more computationally expensive than GCMC.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD): Used to study diffusion kinetics and framework flexibility.

- Define Force Fields: Model the interatomic interactions.

- Classical Force Fields (e.g., UFF4MOF): Are computationally efficient but may lack accuracy for modeling adsorbate-induced deformation [18].

- Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs): Such as CHGNet and MACE-MP-0, are emerging as more accurate alternatives for describing framework flexibility, bridging the gap between classical FFs and DFT [18].

- Run Simulations: Perform GCMC simulations for each MOF under conditions relevant to the application (e.g., for post-combustion CO₂ capture: 298 K, 1 bar for flue gas; 0.01-0.04 bar for direct air capture) [18].

Step 4: Performance Evaluation

Objective: To rank the MOFs based on application-specific performance metrics.

Procedure:

- Extract data from the simulation results (e.g., adsorption loadings from GCMC).

- Calculate a set of key performance indicators (KPIs). Table 2 defines and summarizes the common metrics used for gas adsorption and separation applications.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Evaluating MOFs in Gas Adsorption.

| Metric | Definition | Formula / Description | Significance in Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Selectivity (Sₐds) | The ability to preferentially adsorb one gas (A) over another (B) in a mixture. | ( S{ads}(A/B) = \frac{(xA / xB)}{(yA / y_B)} )Where x and y are mole fractions in adsorbed and bulk phases, respectively. | A primary metric for separation efficiency. High selectivity is crucial [16] [7]. |

| Working Capacity (ΔN) | The amount of adsorbate cycled between adsorption and desorption conditions. | The difference in uptake at adsorption pressure and desorption pressure. | Indicates regenerability and process efficiency. A higher value is preferred [16] [7]. |

| Adsorbent Performance Score (APS) | A composite metric combining selectivity and working capacity. | ( APS = S_{ads} \times \Delta N ) | Provides a balanced single-score for initial ranking [7]. |

| Heat of Adsorption (Qₛt) | The energy released upon adsorption. | Calculated from adsorption isotherms at different temperatures (e.g., via Clausius-Clapeyron equation). | Indicates strength of guest-host interaction. Moderate values are often desired for easy regenerability [16] [7]. |

| Sorbent Selection Parameter (Ssp) | A metric incorporating selectivity and capacity. | ( S{sp} = (S{ads} - 1) \times \Delta N ) | Another composite metric used for ranking [7]. |

| Energy Efficiency (η) | A holistic metric balancing adsorption performance with energy inputs for regeneration. | Incorporates Sₐds, ΔN, APS, Ssp, and energy costs (desorption heat, pressure-swing energy) [7]. | Resolves trade-offs between performance and energy penalty, guiding selection of practical materials [7]. |

Step 5: Machine Learning and Data Analysis

Objective: To accelerate the screening process, identify structure-property relationships, and build predictive models.

Procedure:

- Feature Engineering: Compile a feature set for each MOF, including:

- Model Training: Use the KPIs from Step 4 as target variables to train machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest, CatBoost, Graph Neural Networks) [1] [19]. For large datasets, transformer-based models like Uni-MOF can be pre-trained on hundreds of thousands of structures to predict adsorption capacities directly from CIF files across various conditions [17].

- Analysis and Interpretation:

- Identify Top Candidates: Select the MOFs ranking highest in the targeted KPIs.

- Extract Design Rules: Use feature importance analysis from the ML models to uncover key structural or chemical features that lead to high performance. For example, analysis may reveal that an LCD between 4-7.8 Å and specific functional groups like -SO₂ or -OLi dramatically enhance CO₂ selectivity [7] [1].

The standard HTS workflow presented here provides a robust, iterative framework for the rapid and efficient identification of optimal MOFs for gas adsorption. By moving systematically through database construction, structural filtering, molecular simulation, multi-metric performance evaluation, and machine-learning-driven analysis, researchers can effectively navigate the immense design space of MOFs. This process not only pinpoints high-performing candidates for experimental validation but also generates critical insights that feed back into the rational design of next-generation adsorbents, thereby accelerating the development of advanced materials for carbon capture, hydrogen purification, and other critical separation technologies.

Molecular Simulation Techniques for Predicting Gas Adsorption

The discovery and development of novel porous materials, particularly metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), have transformed approaches to gas storage and separation challenges in energy and environmental applications. With over 5000 new MOFs reported annually [20] and hundreds of thousands of hypothetical structures in databases [16], identifying optimal materials for specific gas adsorption applications presents a significant research challenge. Molecular simulation techniques, augmented by machine learning, have emerged as powerful tools for high-throughput computational screening of these materials, enabling researchers to predict adsorption performance and guide experimental synthesis efforts. These computational approaches have become essential for validating candidate materials within research workflows, significantly accelerating the discovery cycle for high-performance adsorbents targeting gases such as CO₂, H₂, iodine, and electronic specialty gases.

Fundamental Principles of Molecular Simulation for Gas Adsorption

Molecular simulation techniques for predicting gas adsorption in porous materials like MOFs rely on computational methods that model the interactions between gas molecules and the adsorbent framework at the atomic level. These approaches can be broadly categorized into forcefield-based molecular mechanics methods, which calculate potential energy based on classical physics, and first-principles electronic structure methods like density functional theory (DFT), which solve quantum mechanical equations to describe electron behavior [21].

The accuracy of these simulations depends critically on properly characterizing the host-guest interactions, which are governed by van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions, and potentially chemical bonding. For gas adsorption applications, key performance metrics include adsorption capacity (amount of gas adsorbed at equilibrium conditions), selectivity (preferential adsorption of one component over others in a mixture), and deliverable capacity (the usable amount of gas between adsorption and desorption conditions) [16]. These parameters provide crucial insights for evaluating materials for specific applications such as carbon capture, hydrogen storage, or radioactive iodine capture.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Gas Adsorption Evaluation

| Metric | Description | Calculation Method | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Capacity | Amount of gas adsorbed per mass/volume of adsorbent at equilibrium | GCMC simulations at specific T&P | Determines storage potential |

| Selectivity | Preference for one component over others in mixture | Ratio of component loadings adjusted by feed composition | Indicates separation capability |

| Deliverable Capacity | Usable gas between adsorption/desorption conditions | Difference between uptake at storage & delivery pressures | Measures practical utility |

| Heat of Adsorption | Energy released during adsorption process | Slope of adsorption isotherm via Clausius-Clapeyron | Indicates strength of adsorbent-adsorbate interaction |

| Henry's Coefficient | Adsorption affinity at infinite dilution | Limit of loading/pressure as pressure approaches zero | Measures low-pressure performance |

Computational Workflows and Machine Learning Integration

High-Throughput Screening Frameworks

High-throughput computational screening employs automated workflows to evaluate thousands of MOF structures for specific gas adsorption applications. This approach typically begins with structure curation from databases like CoRE MOF, ToBaCCo, or hMOF, followed by geometry optimization and property characterization [16] [1]. Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations are then performed to model gas adsorption behaviors under specific conditions, generating massive datasets that inform machine learning models. This workflow has been successfully applied to identify top-performing MOFs for carbon capture [16], hydrogen storage [3], and iodine capture [1].

For example, in screening MOFs for iodine capture under humid conditions, researchers evaluated 1816 structures with pore limiting diameters sufficient to accommodate iodine molecules (PLD > 3.34 Å) [1]. The GCMC simulations modeled competitive adsorption between iodine and water molecules, revealing optimal structural parameters for maximizing iodine capture efficiency in nuclear waste management applications.

Machine Learning-Enhanced Prediction

Machine learning has dramatically accelerated the screening process by learning complex relationships between material features and adsorption properties, bypassing computationally expensive simulations for new candidate materials. Recent advances include multimodal approaches that utilize data available immediately after MOF synthesis, such as powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns and chemical precursors (metal and linker information) [20]. These models achieve accuracy comparable to crystal structure-based models across geometric, chemical, and quantum-chemical property categories [20].

Different ML architectures excel for specific data types. Transformer models process text-based representations of MOF precursors, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) analyze PXRD patterns, and graph neural networks like Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (CGCNNs) model crystal structures [20]. For small datasets, self-supervised pretraining on large unlabeled MOF databases significantly improves prediction accuracy [20].

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening of MOFs for Carbon Capture

Application Objective: Identify top-performing MOFs for post-combustion CO₂ capture from flue gas mixtures (typically CO₂/N₂ at ~1 bar, 298-313K).

Materials and Computational Methods:

- MOF Database: Select structures from CoRE MOF 2019 or similar curated database

- Simulation Software: RASPA for GCMC simulations

- Forcefields: UFF or Dreiding for framework atoms, TraPPE for CO₂ and N₂ molecules

- Machine Learning: Scikit-learn for Random Forest or CatBoost implementations

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation:

- Obtain crystal structures in .cif format from database

- Remove solvent molecules using geometry optimization while preserving framework integrity

- Assign partial charges using DFT calculations or charge equilibration methods

Structural Characterization:

- Calculate geometric descriptors: pore limiting diameter (PLD), largest cavity diameter (LCD), void fraction, surface area, pore volume

- Use algorithms like Zeo++ for pore structure analysis

- Record chemical descriptors: metal types, organic linker functionality

GCMC Simulation Parameters:

- Equilibration: 50,000 cycles minimum

- Production: 50,000 cycles minimum

- Fugacity: Calculate from specified pressure using ideal gas law or equation of state

- Temperature: 298K for standard conditions

- CO₂/N₂ mixture: Typical flue gas composition (15% CO₂, 85% N₂)

Performance Metrics Calculation:

- CO₂ uptake (mol/kg or cm³/g) at 1 bar and 298K

- CO₂/N₂ selectivity using IAST theory at flue gas conditions

- Working capacity for pressure/vacuum swing processes

- Adsorbent performance score (combination of selectivity and working capacity)

Machine Learning Implementation:

- Feature set: 6 structural descriptors + 25 molecular features + 8 chemical features

- Training data: Minimum 1000 structures with GCMC results

- Model validation: 5-fold cross-validation with 20% holdout test set

- Performance targets: R² > 0.85 on test set for uptake prediction

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Poor model performance may indicate insufficient feature representation; add molecular fingerprint descriptors

- For humid conditions, include water adsorption isotherms to assess competitive adsorption

- Experimental validation requires synthesis of top-ranked MOFs with measured BET surface area and CO₂ adsorption isotherms

Protocol: Machine Learning-Assisted Design for Hydrogen Storage

Application Objective: Discover MOFs with high deliverable H₂ capacity at cryogenic temperatures (77K) for vehicular storage applications.

Materials and Computational Methods:

- Database: Hypothetical MOF databases (hMOF, ToBaCCo)

- ML Model: Random Forest or Graph Neural Network for synthesizability prediction

- Validation: High-pressure H₂ adsorption measurements up to 100 bar

Procedure:

- Virtual Database Construction:

- Generate hypothetical MOFs using topological blueprints and building blocks

- Apply geometric optimization using UFF forcefield

- Filter for synthetically accessible structures using ML synthesizability prediction

Hydrogen Uptake Prediction:

- Perform GCMC simulations at 77K across pressure range (0-100 bar)

- Use quantum-mechanically derived H₂-framework potentials for accuracy

- Calculate deliverable capacity between 5-100 bar or 100-5 bar

Feature Engineering for ML:

- Structural features: Surface area, pore volume, PLD, LCD

- Chemical features: Heat of adsorption, Henry's constant

- Material descriptors: Metal type, functional groups, linker length

Experimental Validation:

- Synthesize top-ranked MOF candidates (e.g., vanadium-based MOFs)

- Characterize using PXRD, BET surface area analysis

- Measure H₂ uptake at 77K using high-pressure gravimetric or volumetric apparatus

- Conduct cyclic stability tests (≥100 adsorption-desorption cycles)

Key Performance Metrics:

- Total gravimetric H₂ uptake: Target >9.0 wt% at 77K and 100 bar

- Volumetric capacity: Target >50 g/L at 77K and 100 bar

- Cyclic stability: <5% capacity loss over 100 cycles

Table 2: Optimal Structural Parameters for Different Gas Adsorption Applications

| Application | Optimal PLD (Å) | Optimal LCD (Å) | Optimal Void Fraction | Optimal Surface Area (m²/g) | Key Chemical Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iodine Capture [1] | 3.34-7.0 | 4.0-7.8 | 0.09-0.17 | 0-540 | N-containing rings, high polarizability |

| CO₂ Capture [16] | 3.0-5.0 | 5.0-10.0 | 0.3-0.5 | 1000-3000 | Open metal sites, amine functionalization |

| H₂ Storage [3] | 4.0-7.0 | 6.0-12.0 | 0.4-0.7 | 2000-5000 | Strong binding sites (≈15 kJ/mol) |

| CH₄ Storage [16] | 4.0-8.0 | 7.0-12.0 | 0.4-0.6 | 2000-4500 | Methyl-functionalization |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Function | Example Tools/Databases |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOF Databases | Data Resource | Source of experimental/theoretical MOF structures | CoRE MOF [16], ToBaCCo [16], hMOF [16], CSD [16] |

| Simulation Software | Computational Tool | Molecular modeling of adsorption behavior | RASPA [1], Gaussian [22], LAMMPS, LAMMPS |

| Quantum Chemistry Data | Dataset | High-accuracy reference calculations | OMol25 [21], ANI-x [21], SPICE [21] |

| Machine Learning Models | Algorithm | Predictive modeling of material properties | Random Forest [1], CatBoost [1], CGCNN [20], Transformer [20] |

| Structure Analysis | Computational Tool | Geometric characterization of porous materials | Zeo++ [16], PoreBlazer [16] |

| Neural Network Potentials | Model | Fast, accurate energy/force prediction | eSEN [21], UMA [21], MACE [21] |

Advanced Data Integration and Visualization

The integration of multimodal data sources represents a significant advancement in molecular simulation for gas adsorption. Recent approaches utilize information available immediately after MOF synthesis—specifically powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns and chemical precursors—to predict potential properties and applications [20]. This synthesis-to-application mapping enables researchers to rapidly identify promising materials without waiting for extensive characterization.

For experimental validation of computational predictions, researchers should focus on synthesizing top-ranked MOF candidates and characterizing them using standard techniques including PXRD for structure verification, BET analysis for surface area and porosity determination, and volumetric/gravimetric adsorption measurements for gas uptake quantification [3]. Advanced characterization such as in-situ spectroscopy can provide insights into gas-framework interactions and binding mechanisms.

Molecular simulation techniques, particularly when integrated with machine learning approaches, provide powerful tools for predicting gas adsorption performance in metal-organic frameworks. The protocols outlined here for carbon capture, hydrogen storage, and iodine capture demonstrate robust workflows for high-throughput screening and material design. As these computational methods continue to advance—especially through multimodal learning and improved neural network potentials—they offer increasingly accurate predictions that guide experimental efforts, accelerating the discovery and development of next-generation adsorbents for critical energy and environmental applications.

The validation of high-throughput screening (HTS) for metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) in gas adsorption research necessitates the development of integrated performance metrics that simultaneously balance selectivity with energy cost. Traditional materials discovery approaches have often prioritized single adsorption properties, such as uptake capacity or selectivity, in isolation. However, for industrial applications like hydrogen purification, carbon capture, and direct air capture, the energy penalty associated with sorbent regeneration critically determines practical viability [23] [24] [25]. This application note establishes standardized protocols for calculating multidimensional performance metrics that integrate separation efficiency with energy considerations, providing a validated framework for accelerating the discovery of high-performance MOFs within a thesis research context.

Performance Metrics for MOF Evaluation

Defining Integrated Performance Indicators

Comprehensive evaluation of MOF adsorbents requires moving beyond single-property assessment to integrated metrics that reflect actual process efficiency. The table below summarizes key performance indicators that bridge material properties with process economics.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for MOF Adsorbent Evaluation

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorbent Performance Score (APS) | Combines working capacity and selectivity into single metric [23] | Higher values indicate better balance of capacity and selectivity | Hydrogen purification from CH₄ [23] |

| Working Capacity | Δq = qₐds - qᵢes (difference between adsorbed and desorbed quantities) [23] [25] | Determines adsorbent amount needed; impacts equipment size | Pressure/Vacuum Swing Adsorption [23] [25] |

| Percent Regenerability | (1 - qᵢes/qₐds) × 100% [25] | Higher values reduce energy for desorption | Temperature Swing Adsorption [25] |

| Parasitic Energy | Total energy required per amount of gas captured [24] | Lower values indicate reduced operating costs | Direct Air Capture [26] |

| Separation Potential | Combines selectivity and capacity with process conditions [23] | Evaluates technical feasibility under realistic scenarios | Carbon capture from flue gas [24] |

Structure-Performance Relationships

The integration of performance metrics with MOF structural characteristics enables predictive screening. Analysis of the CoRE-MOF 2019 database reveals that optimal pore limiting diameters (PLD) for CH₄/H₂ separation fall between 4-7.8Å, while ideal largest cavity diameters (LCD) range from 4-5.5Å [23] [1]. MOFs with densities approximately 0.9 g/cm³ frequently exhibit enhanced performance due to balanced adsorption site density and transport kinetics [23] [1]. These structure-property correlations provide valuable screening criteria prior to molecular simulation.

Computational Protocols for High-Throughput Screening

Molecular Simulation Methods

Table 2: Computational Protocols for MOF Performance Evaluation

| Method | Key Parameters | Output Metrics | Software Tools |

|---|---|---|---|