T7E1 Assay vs. Next-Generation Sequencing: A Modern Researcher's Guide to CRISPR Indel Detection

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between the T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for detecting insertions and deletions (indels) in CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing.

T7E1 Assay vs. Next-Generation Sequencing: A Modern Researcher's Guide to CRISPR Indel Detection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between the T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for detecting insertions and deletions (indels) in CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of each method, detail their practical applications, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present a rigorous validation and comparative analysis based on recent benchmarking studies. The goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to select the most appropriate, accurate, and efficient indel detection method for their specific research needs, from initial screening to clinical-grade validation.

Understanding the Core Technologies: From T7E1 Cleavage to NGS Sequencing

The T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay is a widely adopted method for evaluating the efficiency of genome-editing tools, such as CRISPR-Cas9. Its utility stems from its ability to detect DNA heteroduplexes formed when edited and wild-type DNA strands hybridize. The core principle relies on the function of the T7 Endonuclease I enzyme, a structure-selective nuclease derived from Escherichia coli bacteriophage T7. This enzyme specifically recognizes and cleaves DNA at sites of structural deformity. When a heteroduplex DNA forms between a wild-type strand and an indel-containing mutant strand, the mispairing causes a physical distortion in the DNA duplex. T7E1 exploits these structural kinks and bulges, cleaving the DNA at or near the mismatch site [1] [2].

The assay is particularly effective at detecting insertion/deletion (indel) mutations because these create extrahelical loops that result in significant DNA distortion, making them optimal substrates for T7E1. While the enzyme can also cleave DNA containing single-base mismatches, its efficiency is generally greater for larger indels due to the more pronounced structural distortion they cause [2]. This biochemical property makes the T7E1 assay a cost-effective and technically straightforward choice for the initial validation of nuclease activity in edited cell pools.

T7E1 Experimental Workflow

The T7E1 assay follows a series of defined steps, from sample preparation to data visualization. The workflow ensures that heteroduplexes are formed and cleaved, with results that can be quickly interpreted.

Step-by-Step Protocol

A standard T7E1 assay protocol consists of the following key stages [3]:

- CRISPR Delivery and Genome Extraction: The first step involves introducing the genome-editing machinery (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9) into cells via methods like lentivirus transduction, plasmid transfection, or ribonucleoprotein delivery. After a suitable incubation period (typically 3-4 days), genomic DNA is harvested from the edited cells and control cells using a commercial extraction kit or direct PCR methods.

- PCR Amplification of Target Locus: The genomic region surrounding the nuclease target site is amplified by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). To enhance specificity, a nested PCR approach is often recommended. This involves a first-round PCR of 20 cycles to generate an 800-1000 bp product, followed by a second-round PCR of 30-40 cycles to generate a final amplicon of around 500 bp.

- DNA Denaturation and Annealing: The purified PCR products are subjected to a denaturation and reannealing process. This involves heating the PCR products to a high temperature (e.g., 95°C) to separate the DNA strands, followed by slow cooling. This slow cooling allows strands to randomly re-hybridize, forming homoduplexes (WT/WT or mutant/mutant) and heteroduplexes (WT/mutant).

- T7E1 Enzyme Digestion: The reannealed DNA is then incubated with the T7 Endonuclease I enzyme in an appropriate reaction buffer at 37°C for 30 minutes. The enzyme will cleave the heteroduplex DNA at the site of the mismatch.

- Gel Electrophoresis and Visualization: The digestion products are separated by agarose gel electrophoresis (using 1.2%-1.5% agarose gels). The gel is then imaged. In a non-edited control sample, only the intact, parental PCR band is visible. In a successfully edited sample, the cleavage of heteroduplexes produces two smaller, predictable bands. The ratio of the cleaved bands to the uncleaved band can be used for a semi-quantitative estimation of editing efficiency [1] [4].

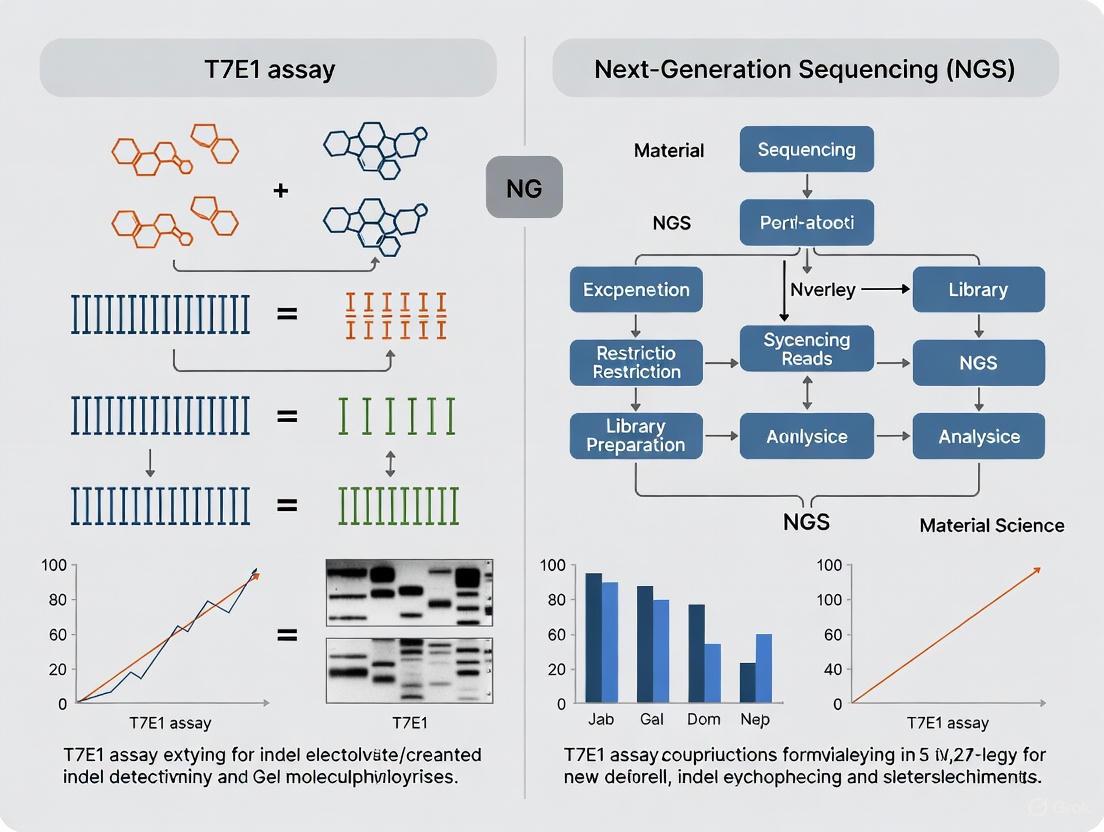

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of the T7E1 assay, from DNA hybridization to result interpretation:

Performance Comparison: T7E1 vs. Next-Generation Sequencing

While the T7E1 assay offers speed and cost benefits, its performance characteristics differ significantly from the gold-standard method, Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). A direct comparison reveals critical limitations in the T7E1 assay's accuracy and dynamic range.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of T7E1 and NGS Performance

| Performance Metric | T7E1 Assay | Targeted NGS | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Detected Indel Frequency | 22% | 68% | Analysis of 19 sgRNAs in human and mouse cells [1] |

| Detection of Low Activity (<10%) | Often appears inactive | Accurately detects | sgRNA H3 in human cells [1] |

| Detection of High Activity (>90%) | Appears modestly active (~41%) | Accurately detects (>90%) | sgRNAs M1 and M5 in mouse cells [1] |

| Dynamic Range | Limited, compresses values | High, linear correlation | Pools of edited mammalian cells [1] |

| Ability to Resolve sgRNAs with Similar Activity | Poor (e.g., both ~28%) | Excellent (40% vs. 92%) | sgRNAs M2 and M6 [1] |

| Quantitative Nature | Semi-quantitative | Fully quantitative | - |

| Information on Indel Sequences | No | Yes | - |

The data from a comprehensive survey highlights three major sources of T7E1 inaccuracy [1]:

- Poor Sensitivity at Extremes: The assay fails to reliably detect low editing frequencies (<10%) and significantly underestimates high editing frequencies (>90%).

- Low Dynamic Range: The T7E1 signal becomes saturated, causing it to report similar values for sgRNAs with vastly different actual efficiencies. For instance, two sgRNAs with ~28% activity by T7E1 showed a more than two-fold difference in actual efficiency (40% vs. 92%) when measured by NGS.

- Dependence on Heteroduplex Formation: The assay requires the formation of DNA heteroduplexes for cleavage. In a highly edited pool with a low proportion of wild-type alleles, heteroduplex formation is reduced, leading to an underestimation of efficiency [1].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful execution of the T7E1 assay requires a specific set of reagents and materials. The following table details the key components and their functions in the experimental protocol.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for the T7E1 Assay

| Reagent / Material | Function and Importance in the T7E1 Workflow |

|---|---|

| T7 Endonuclease I Enzyme | The core component; a structure-selective nuclease that cleaves distorted DNA at heteroduplex sites [1] [3]. |

| NEBuffer 2 (or equivalent) | Provides the optimal salt and pH conditions (e.g., 37°C incubation) for maximum T7E1 enzyme activity [4]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Used for PCR amplification of the target locus; high fidelity is critical to minimize PCR-introduced errors that could be falsely cleaved by T7E1 [4]. |

| Gel & PCR Clean-Up Kit | Essential for purifying PCR products prior to the heteroduplex formation and digestion steps, removing primers, salts, and enzymes that could interfere [4]. |

| Agarose | Used to prepare 1.2%-1.5% gels for electrophoresis, allowing for clear separation and visualization of cleaved and uncleaved DNA fragments [3]. |

The T7E1 assay operates on a straightforward biochemical principle: detecting structural distortions in heteroduplex DNA formed by indel mutations. Its primary advantages are low cost, technical simplicity, and rapid turnaround, making it a viable option for initial, qualitative checks of nuclease activity during CRISPR system optimization [5]. However, the experimental data unequivocally shows that the T7E1 assay is a semi-quantitative method with a limited dynamic range and poor accuracy, often failing to reflect the true editing efficiency revealed by NGS [1].

For researchers requiring precise quantification of indel frequencies or information on the specific spectrum of mutations, Targeted NGS remains the gold standard. For those seeking a middle ground between cost and information content, Sanger sequencing-based methods like TIDE or ICE provide a more quantitative and reliable alternative to T7E1 for many applications [1] [5]. The choice of method ultimately depends on the required balance between accuracy, cost, throughput, and the need for detailed sequence information in the context of the research project.

In the realm of genetic engineering and functional genomics, the precision of your indel discovery tools directly determines the reliability of your research outcomes. While the T7 Endonuclease 1 (T7E1) assay has served as a traditional method for preliminary screening of nuclease activity, Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has emerged as a transformative technology that provides unparalleled resolution for characterizing insertion and deletion mutations. The fundamental distinction between these methods lies in their core mechanisms: T7E1 relies on detecting structural deformities in heteroduplexed DNA, while NGS directly sequences millions of DNA fragments in parallel, providing base-pair resolution of editing outcomes [6] [7]. This comprehensive analysis objectively compares the performance of these methodologies, providing experimental data and protocols to guide researchers in selecting the optimal approach for their indel discovery projects, particularly within the context of CRISPR-Cas9 editing validation and cancer research applications.

The limitations of traditional methods have become increasingly apparent as precision medicine advances. One study demonstrated that T7E1 estimates of nuclease activity frequently fail to accurately reflect the activity observed in edited cells, with editing efficiencies of CRISPR-Cas9 complexes showing dramatically different results when validated by NGS [6]. In some cases, sgRNAs with greater than 90% editing efficiency detected by NGS appeared only modestly active in T7E1 assays, highlighting concerning discrepancies between methods [7]. This evidence positions NGS not merely as an alternative but as an essential tool for research requiring quantitative precision in indel characterization.

Fundamental Principles: How T7E1 and NGS Detect Indels

T7E1 Assay Mechanism

The T7 Endonuclease 1 assay operates as a structure-selective enzymatic method that identifies structural deformities in heteroduplexed DNA without providing nucleotide-level resolution [6]. The experimental workflow begins with PCR amplification of the target genomic region from edited cells. The resulting amplicons are then denatured and slowly reannealed, allowing heteroduplex formation between wild-type and mutant strands with indels. These heteroduplexes contain structural distortions—either mismatches or bulges—that are recognized and cleaved by the T7E1 enzyme [6] [2]. The cleavage products are separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and mutation frequencies are estimated through densitometric analysis of band intensities, comparing digested fragments to undigested parental bands [4].

This enzyme, derived from Escherichia coli bacteriophage, resolves branched phage DNA during capsid maturation and cuts DNA at the 5' base of cruciform structures in vitro [6]. Its performance depends heavily on the nature of the DNA distortion, with deletion mutations typically cleaved more efficiently than single nucleotide polymorphisms [2]. The requirement for heteroduplex formation means the assay cannot detect homozygous or bi-allelic edits efficiently, and its resolution is limited to inferring the presence of indels rather than characterizing their specific sequences or sizes.

NGS-Based Indel Discovery Mechanism

Next-Generation Sequencing operates on fundamentally different principles, employing massively parallel sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously to provide comprehensive, base-pair-resolution data on editing outcomes [8]. The standard workflow involves PCR amplification of the target locus, preparation of sequencing libraries with platform-specific adapters, and sequencing using one of several technologies—most commonly sequencing-by-synthesis approaches used in Illumina platforms [8] [9]. The resulting sequence reads are aligned to a reference genome, and indels are identified through specialized bioinformatics pipelines that detect misalignments and sequence variations against the wild-type sequence [10] [9].

The NGS approach captures the full spectrum of editing outcomes, including precise nucleotide changes, complex mutations, and multiple simultaneous edits in the same cell population. Unlike T7E1, NGS can accurately quantify the prevalence of each mutation type in a heterogeneous pool of cells and detect homozygous modifications [6]. The technology also provides information on the exact position, size, and sequence context of each indel, enabling researchers to predict functional consequences on protein coding potential, including frameshifts, premature stop codons, and in-frame deletions or insertions [10].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data Reveals Stark Contrasts

Sensitivity and Dynamic Range

Multiple studies have systematically compared the sensitivity and detection capabilities of T7E1 and NGS methods, revealing dramatic differences in performance, particularly in the accurate quantification of editing efficiencies [6] [7]. In one comprehensive survey evaluating 19 sgRNAs targeting human and mouse genes, the T7E1 assay detected an average mutation frequency of 22%, with the highest activity reported at 41% [6] [7]. Strikingly, when the same samples were analyzed by targeted NGS, the average editing efficiency jumped to 68%, with 9 individual sgRNAs yielding indel frequencies of 70% or greater [6]. This systematic underestimation by T7E1 demonstrates its limited dynamic range, particularly problematic when evaluating highly active sgRNAs.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of T7E1 vs. NGS for Editing Efficiency Assessment

| Metric | T7E1 Assay | NGS-Based Methods | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Editing Efficiency Detection | 22% | 68% | Analysis of 19 sgRNAs in human and mouse cells [6] |

| Maximum Detection Range | 41% | >90% | Same study showing T7E1 plateau effect [6] [7] |

| Detection of Low-Efficiency Editing | Poor (<10% NHEJ undetectable) | High sensitivity | sgRNAs with <10% editing by NGS appeared inactive by T7E1 [6] |

| Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) Detection Limit | Not applicable | 2.9% for SNVs and INDELs | Established through dilution series [9] |

| Ability to Detect Complex Indels | Limited to inference | Base-pair resolution | NGS identifies exact sequences and sizes [10] [9] |

The fundamental limitations of T7E1 become particularly evident when examining its performance across different editing efficiency ranges. For poorly performing sgRNAs with less than 10% editing efficiency by NGS, T7E1 frequently failed to detect any activity above background [6]. Conversely, for highly active sgRNAs with greater than 90% efficiency by NGS, T7E1 reported only modest activity around 30-40% [6] [7]. Perhaps most concerning was the finding that sgRNAs with apparently similar activity by T7E1 (~28% for both M2 and M6) proved dramatically different by NGS (92% vs. 40%, respectively) [6]. These discrepancies highlight the risks of relying solely on T7E1 for sgRNA selection, potentially leading researchers to discard highly effective guides or proceed with inefficient ones.

Accuracy and Resolution in Indel Characterization

Beyond quantitative assessment of editing efficiency, NGS provides superior capabilities in characterizing the precise nature and spectrum of induced mutations. While T7E1 can indicate the presence of indels, it cannot determine their exact sizes, sequences, or positions relative to the cut site [6]. In contrast, NGS delivers comprehensive information about the distribution of indel sizes, the specific nucleotide changes, and the proportion of frameshift versus in-frame mutations—critical data for predicting functional consequences of gene editing [10].

The advantage of NGS resolution becomes particularly important when analyzing complex editing outcomes. Research shows that CRISPR-Cas9 editing produces diverse mutations including single-base insertions/deletions, multi-base changes, and complex combinations [10]. In one extensive analysis of 516 manually curated indels, the size distribution varied considerably: 67% of insertions were 1 bp, 20% were 2-5 bp, 7% were 6-10 bp, and 6% were longer than 10 bp (up to 27 bp) [10]. For deletions, 71% were 1 bp, 17% were 2-5 bp, 5% were 6-10 bp, and 6% exceeded 10 bp (up to 54 bp) [10]. This diverse spectrum of mutations is largely invisible to T7E1 but fully characterized by NGS.

Table 2: Indel Characterization Capabilities: T7E1 vs. NGS

| Characterization Aspect | T7E1 Assay | NGS-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Indel Size Determination | Indirect inference only | Precise base-pair resolution |

| Sequence Identification | Not possible | Complete nucleotide-level detail |

| Frameshift vs. In-Frame Classification | Indirect inference | Direct determination from sequence |

| Detection of Multiple Simultaneous Edits | Limited | Comprehensive detection and quantification |

| Variant Allele Frequency Precision | Semi-quantitative (densitometry) | Highly quantitative (digital counting) |

| Homozygous/Biallelic Editing Detection | Challenging | Straightforward differentiation |

The application of these methodologies in clinical contexts further highlights the superiority of NGS. In cancer research, for example, accurate indel calling plays a crucial role in precision medicine, as indels can disrupt normal function of tumor suppressor genes or activate oncogenic pathways [10]. Targeted NGS panels have demonstrated exceptional performance in clinical settings, with one recently developed 61-gene oncopanel showing 99.99% repeatability and 99.98% reproducibility, while detecting mutations with 98.23% sensitivity and 99.99% specificity [9]. This level of precision is unattainable with T7E1-based approaches.

Experimental Protocols: From Bench to Data Analysis

Detailed T7E1 Mismatch Cleavage Assay Protocol

The T7E1 protocol requires specific reagents and careful execution to generate interpretable results. The following protocol has been adapted from multiple methodological descriptions in the surveyed literature [6] [4] [2]:

Materials and Reagents:

- T7 Endonuclease I (commercially available from suppliers such as New England Biolabs)

- NEBuffer 2 (or appropriate reaction buffer)

- PCR amplification system with high-fidelity DNA polymerase

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

- DNA purification kits (gel and PCR clean-up)

- Ethidium bromide or alternative DNA stain

Procedure:

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target genomic region from both edited and control samples using gene-specific primers. The amplicon size should ideally be 300-800 bp for optimal resolution.

- Purification: Purify PCR products using a commercial PCR clean-up kit to remove primers, enzymes, and contaminants.

- Heteroduplex Formation: Denature and reanneal the DNA by heating the purified PCR products to 95°C for 5-10 minutes, then slowly cool to room temperature (approximately 0.1-1.0°C per second) to allow formation of heteroduplexes between wild-type and mutant strands.

- T7E1 Digestion: Set up digestion reactions containing 8 μL of purified PCR product, 1 μL of NEBuffer 2, and 1 μL of T7 Endonuclease I. Incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Analysis: Separate digestion products by agarose gel electrophoresis (1-2% agarose). Include undigested control PCR product for comparison.

- Quantification: Visualize bands under UV light and calculate mutation frequency using densitometric analysis software such as ImageJ. The percentage of indels can be calculated using the formula: % indel = 100 × (1 - [1 - (a + b)/(c + a + b)]^{1/2}), where a and b represent the intensities of cleavage products and c represents the intensity of the undigested PCR product.

Critical Considerations:

- Include appropriate positive and negative controls in each experiment

- Optimize enzyme concentration and digestion time empirically

- Be aware that cleavage efficiency varies with mismatch type and sequence context

- Recognize that subjective bias in band selection for densitometry can introduce error [6]

Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Protocol for Indel Discovery

The NGS approach provides comprehensive data but requires more sophisticated instrumentation and bioinformatics capabilities. The following protocol outlines a standard targeted sequencing approach for indel discovery [6] [9]:

Materials and Reagents:

- High-fidelity PCR master mix (e.g., Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Master Mix)

- Library preparation kit (commercial platforms available from Illumina, Thermo Fisher, or MGI)

- Sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq, MGI DNBSEQ-G50RS)

- DNA quantification system (fluorometric methods preferred)

Procedure:

- PCR Amplification: Amplify target regions using gene-specific primers with overhang adapter sequences. Use high-fidelity polymerase to minimize PCR errors.

- Library Preparation: Purify PCR products and proceed with library preparation according to manufacturer's instructions. This typically includes:

- Fragmentation (if necessary)

- End repair and A-tailing

- Adapter ligation

- Library amplification with index primers

- Quality Control: Quantify libraries using fluorometric methods and assess size distribution with capillary electrophoresis.

- Sequencing: Pool libraries at appropriate molar ratios and load onto sequencing platform. For indel detection, aim for minimum coverage of 1000× per amplicon to reliably detect low-frequency variants [9].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Demultiplexing: Separate sequencing reads by sample using index sequences

- Quality Control: Assess read quality using tools like FastQC

- Alignment: Map reads to reference sequence using aligners such as BWA or Bowtie2

- Variant Calling: Identify indels using specialized algorithms (e.g., GATK HaplotypeCaller, LoFreq)

- Annotation: Predict functional consequences of identified indels

Critical Considerations:

- Ensure sufficient DNA input (≥50 ng) for reliable detection [9]

- Include control samples with known indel profiles to validate sensitivity

- Establish variant allele frequency threshold based on desired sensitivity/specificity balance (typically 2-5%)

- Implement duplicate marking to mitigate PCR amplification biases

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Indel Discovery

Selecting appropriate reagents and platforms is crucial for success in indel discovery workflows. The following table summarizes key solutions and their applications based on the surveyed literature:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Indel Discovery

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Key Features | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| T7 Endonuclease I | Mismatch cleavage enzyme | Recognizes and cleaves distorted heteroduplex DNA | More sensitive for deletions than single nucleotide changes [2] |

| Surveyor Nuclease | Alternative mismatch cleavage enzyme | Single-strand specific nuclease, better for single nucleotide changes | Commercial CEL I family enzyme [2] |

| Illumina Platforms | NGS sequencing | Sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible terminators | High accuracy, short reads (36-300 bp) [8] |

| PacBio SMRT Sequencing | NGS sequencing | Long-read sequencing without PCR amplification | Average read length 10,000-25,000 bp [8] |

| Oxford Nanopore | NGS sequencing | Long-read sequencing via electrical impedance detection | Average read length 10,000-30,000 bp, higher error rate [8] |

| Sophia DDM Software | NGS data analysis | Machine learning for variant analysis and visualization | Connects molecular profiles to clinical insights [9] |

| ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) | Indel analysis algorithm | Decomposes Sanger sequencing traces to estimate editing efficiency | Web-based tool for quick assessment [11] |

| TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Decomposition) | Indel analysis algorithm | Compares sequencing chromatograms from edited and control samples | Provides indel spectrum and frequency [11] |

The comprehensive comparison between T7E1 and NGS technologies reveals a clear trajectory for indel discovery methodologies. While T7E1 offers advantages in terms of cost, technical simplicity, and rapid results for preliminary screening, its limitations in dynamic range, accuracy, and resolution make it unsuitable for research requiring quantitative precision or complete characterization of editing outcomes [6] [7]. Next-Generation Sequencing, despite requiring more substantial infrastructure investment and bioinformatics expertise, provides unparalleled comprehensive data on the full spectrum of induced mutations with quantitative accuracy essential for rigorous scientific research and clinical applications [10] [9].

The strategic selection between these methodologies should be guided by research objectives, resources, and required precision. For initial sgRNA screening where relative activity ranking suffices, T7E1 may provide adequate information. However, for characterization of editing outcomes, quantification of editing efficiencies, clinical applications, or publication-quality data, NGS emerges as the unequivocal gold standard. As the costs of sequencing continue to decline and analytical pipelines become more accessible, NGS-based indel discovery is positioned to become the benchmark for rigorous genome editing research and clinical molecular diagnostics.

In genetic research, accurately identifying DNA variations such as insertions and deletions (indels) is fundamental for applications ranging from functional genomics to clinical diagnostics. The T7 Endonuclease 1 (T7E1) assay, a gel electrophoresis-based method, and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), which employs massively parallel sequencing, represent two distinct technological approaches for this purpose [7] [12]. The T7E1 assay is a classic, gel-based technique that detects mismatches in heteroduplexed DNA, while NGS determines the exact nucleotide sequence of millions of DNA fragments simultaneously [12] [13]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their workflows, performance metrics, and suitability for different research scenarios in indel detection.

Workflow and Core Principles

Gel Electrophoresis (Exemplified by the T7E1 Assay)

The T7E1 assay is a mismatch cleavage assay that indirectly detects indels by recognizing structural distortions in DNA heteroduplexes. Its workflow is relatively straightforward and does not require sophisticated sequencing instruments [7] [14].

Diagram 1: T7E1 Assay Workflow. The key steps involve forming heteroduplex DNA and cleaving mismatches with the T7E1 enzyme before gel-based visualization.

Experimental Protocol for T7E1 Assay [7]:

- PCR Amplification: The genomic region spanning the target site is amplified by PCR from treated and control samples.

- Heteroduplex Formation: The PCR products are denatured at 95°C and then slowly cooled to room temperature to allow reannealing. If indels are present, this process creates heteroduplexes—DNA duplexes with mismatched bases and bulges.

- T7E1 Digestion: The reannealed DNA is incubated with the T7E1 enzyme, which cleaves specifically at the sites of heteroduplex formation.

- Analysis: The digestion products are separated by agarose or polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The presence of indels is indicated by the appearance of additional, smaller bands. Editing efficiency is typically estimated by comparing the band intensities of cleaved and uncleaved products using densitometry.

Massively Parallel Sequencing (NGS)

NGS detects indels by directly determining the nucleotide sequence of amplified target regions across millions of clusters in parallel. This provides a comprehensive, base-by-base view of all mutations present in a sample [15] [12] [13].

Diagram 2: Targeted NGS Workflow for Indel Detection. The process involves preparing a library of DNA fragments that are simultaneously sequenced and computationally analyzed.

Experimental Protocol for Targeted NGS (Amplicon Sequencing) [7] [12]:

- Library Preparation: The target region is amplified by PCR. In contrast to the T7E1 assay, the primers used include platform-specific adapters and sample-specific barcodes, which allow multiple samples to be pooled and sequenced together in a single run (multiplexing) [15].

- Clonal Amplification: The adapter-ligated fragments are immobilized on a flow cell or within emulsion droplets and amplified into clusters to generate a strong enough signal for sequencing.

- Sequencing by Synthesis: The system sequentially adds fluorescently labeled nucleotides. As each nucleotide is incorporated into a growing DNA strand, a camera records the fluorescence, determining the sequence of each cluster.

- Data Analysis: The short sequence reads (e.g., 2x250 bp for MiSeq) are aligned to a reference genome. Specialized bioinformatics tools then identify and quantify the types and frequencies of indels at the target site with single-base resolution.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The fundamental differences in the principles of T7E1 and NGS lead to significant disparities in their analytical performance, as demonstrated by validation studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of T7E1 vs. NGS

| Performance Metric | T7E1 Assay | Massively Parallel Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Indirect, via heteroduplex cleavage [7] | Direct, base-by-base sequencing [12] |

| Sensitivity (Limit of Detection) | ~15-20% variant allele frequency [13] | As low as 1% variant allele frequency [13] |

| Dynamic Range | Limited; peaks at ~37-41% efficiency, struggles with higher efficiencies [7] | Broad and linear; accurately quantifies from very low to very high editing rates [7] |

| Accuracy in Editing Efficiency | Often inaccurate; frequently over- or under-estimates true efficiency compared to NGS [7] | High accuracy; considered a gold standard for benchmarking other methods [7] [16] |

| Mutation Resolution | Limited; smaller indels (<3 bp) can be missed [14] | High; can identify single-nucleotide changes and complex mutations [13] |

| Discovery Power | Low; can only detect the presence, not the exact identity, of indels [7] | High; can detect novel, unexpected, and complex variants [13] |

A direct comparative study highlighted these performance gaps. When analyzing the same pools of CRISPR-Cas9 edited cells, the T7E1 assay reported editing efficiencies for most sgRNAs in a narrow range of 17% to 29%, with a maximum of 41%. In contrast, targeted NGS revealed a much broader and more realistic spectrum of activities, demonstrating that T7E1 often incorrectly reports sgRNA activities due to its low dynamic range and dependence on DNA heteroduplex formation [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of these protocols requires specific kits and reagents. The following table outlines essential solutions for setting up T7E1 and NGS assays.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for T7E1 and NGS Workflows

| Item | Function in Workflow | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lysis & DNA Extraction | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA for PCR. | Extract-N-Amp Tissue PCR Kit (Sigma); HotSHOT method (NaOH & Tris-HCl) [14]. |

| PCR Reagents | Amplification of the target genomic locus. | DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and target-specific primers [7]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I | Cleaves heteroduplex DNA at mismatch sites. | Commercially available T7E1 enzyme [7]. |

| Gel Electrophoresis System | Separation and visualization of DNA fragments by size. | Agarose or polyacrylamide gels, electrophoresis tank, and power supply [7] [17]. |

| Library Prep Kits | Preparation of PCR amplicons for sequencing, including adapter ligation and barcoding. | Kits from Illumina, Thermo Fisher, etc., for amplicon library construction [15] [12]. |

| Sequencing Kits & Flow Cells | Execution of the sequencing reaction on the instrument. | Platform-specific sequencing kits (e.g., MiSeq Reagent Kits) and flow cells [12]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | Data analysis, including sequence alignment and variant calling. | Tools for processing FASTQ files, aligning to a reference (e.g., BWA), and identifying indels [7] [12]. |

The choice between gel electrophoresis-based T7E1 assay and massively parallel sequencing for indel detection is a trade-off between simplicity and comprehensiveness.

- Use the T7E1 assay for initial, low-cost screening when the goal is to quickly confirm the presence of nuclease activity and project resources or access to NGS is limited. Its lower sensitivity and accuracy make it less suitable for quantitative analyses or detecting subtle mutations [7] [13].

- Opt for targeted NGS when the research demands high sensitivity, precise quantification of editing efficiency, identification of the exact sequence of indels, or the discovery of complex and unexpected mutations. It is the unequivocal method for rigorous validation and for applications where quantitative accuracy is critical, such as in therapeutic development [7] [16] [13].

For researchers validating CRISPR-Cas9 editing, the evidence strongly suggests that NGS provides a more reliable and informative assessment of nuclease activity and outcomes than the T7E1 assay [7] [16].

The Critical Role of Indel Detection in Validating CRISPR-Cas9 Editing Efficiency

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 system has revolutionized genome editing by providing an efficient and programmable method for manipulating DNA sequences. The fundamental mechanism involves the Cas9 nuclease creating a site-specific double-strand break (DSB) in the genomic DNA, which is subsequently repaired by cellular mechanisms, predominantly the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway [18] [19]. This repair process frequently results in small insertions or deletions, collectively termed indels, at the target site. When these indels occur within protein-coding sequences and disrupt the reading frame, they can effectively achieve gene knockout, making indel efficiency a primary metric for evaluating CRISPR-Cas9 activity [18].

The accurate detection and quantification of these indels are not merely confirmatory but are critical for validating the success and precision of gene editing experiments. The spectrum of CRISPR-induced mutations is broad and unpredictable, encompassing various deletions, insertions, and combinations thereof [2]. Moreover, the editing outcome in a pool of cells is often a complex mosaic of multiple mutant alleles, each potentially present at different frequencies [2] [6]. This complexity underpins the necessity for robust, sensitive, and quantitative detection methods. The choice of detection assay profoundly influences the perceived editing efficiency, a critical factor when screening guide RNAs (gRNAs), optimizing delivery methods, or assessing therapeutic safety by evaluating off-target effects [19]. Within this landscape, the T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) have emerged as prominent techniques, each with distinct advantages and limitations. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods, grounded in experimental data, to inform researchers' selection of the most appropriate indel validation strategy.

Understanding Indels: Biology and Detection Challenges

Indels are the second most common form of genetic variation in humans after single nucleotide variants (SNVs) [18]. In the context of CRISPR-Cas9 editing, they arise predominantly from the repair of Cas9-induced DSBs via the NHEJ and microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) pathways [18]. The NHEJ pathway is active throughout the cell cycle and often results in small indels of a few base pairs, while MMEJ, active in S and G2 phases, exploits microhomologies of 2-20 nucleotides and typically produces deletions that remove one copy of the homologous sequence and the intervening DNA [18].

The intrinsic characteristics of indels pose significant detection challenges. The size and type of indels vary considerably; a comprehensive benchmarking study found that among 516 validated indels, 71% of deletions and 67% of insertions were single base pairs, while the remainder ranged from 2 to over 50 base pairs [10]. This variability complicates the development of a one-size-fits-all detection assay. Furthermore, in a pool of edited cells, the outcome is a heterogeneous mixture of wild-type and various mutant alleles, each with a different Variant Allele Frequency (VAF). The same study reported that 87% of indels had a VAF below 20%, with 62% in the challenging 1-5% range [10]. Accurately quantifying this complex mixture requires methods with high sensitivity and a broad dynamic range. Finally, the process of aligning sequencing reads to a reference genome is computationally demanding and prone to errors, especially for insertions and deletions located in repetitive genomic regions or those involving homopolymers [18] [20]. The accuracy of indel calling from NGS data is highly dependent on the choice of bioinformatics tools, with different algorithms exhibiting vastly different performance profiles [20].

Methodological Deep Dive: T7E1 Assay vs. NGS

T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay

The T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay is a mismatch cleavage method that leverages the ability of the T7E1 enzyme to recognize and cleave distorted DNA structures [2].

- Experimental Protocol: The genomic region flanking the CRISPR target site is first amplified by PCR from a heterogeneous population of edited and unedited cells. The resulting PCR products are then subjected to a denaturation and re-annealing process, which generates heteroduplex DNA when a mutated DNA strand pairs with a wild-type strand, creating a bulge or mismatch at the site of the indel. These heteroduplexes are incubated with the T7E1 enzyme, which cleaves at the mismatch site. The cleavage products are separated and visualized via agarose gel electrophoresis. The editing efficiency is typically estimated using densitometric analysis of the gel image, comparing the intensity of the cleaved bands to the total DNA (cleaved and uncleaved) [2] [4] [5].

- Strengths and Limitations: The primary advantages of the T7E1 assay are its speed, simplicity, and low cost, making it suitable for initial screening or gRNA validation when resources are limited [5]. It does not require specialized instrumentation beyond standard molecular biology equipment. However, the assay has significant drawbacks. It is only semi-quantitative and its accuracy is limited, particularly at high editing efficiencies where it tends to underestimate mutation rates [6] [21]. One study found that T7E1 failed to accurately reflect the activity observed by NGS, often reporting modest activity for sgRNAs that NGS showed had greater than 90% efficiency [6]. Furthermore, its sensitivity depends on the type of mutation; it is more efficient at detecting deletions than single nucleotide changes, and it provides no information on the specific sequences of the induced indels [2] [5].

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

Targeted NGS involves deep sequencing of PCR amplicons spanning the CRISPR target site, providing a base-by-base resolution of the editing outcomes.

- Experimental Protocol: The target locus is amplified from edited genomic DNA, and the resulting amplicons are prepared into a sequencing library. This library is then subjected to high-throughput sequencing, generating hundreds of thousands to millions of reads covering the target site. The raw sequencing data is processed through a bioinformatics pipeline that typically includes quality control, alignment of reads to a reference sequence, and variant calling to identify and quantify insertions and deletions [6] [20].

- Strengths and Limitations: The principal strength of NGS is its high accuracy, sensitivity, and comprehensive data output. It can detect low-frequency indels (with a VAF < 1%), precisely quantify editing efficiency across a wide dynamic range, and fully characterize the spectrum and distribution of all indel sequences present in the sample [6]. It is considered the gold standard for validation [5]. The limitations of NGS are its higher cost, longer turnaround time, and the requirement for sophisticated bioinformatics infrastructure and expertise [5]. The accuracy of the results is also contingent on the choice of indel-calling algorithm, as different tools show considerable variation in performance [20].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Direct comparisons between T7E1 and NGS reveal critical differences in their ability to quantify editing efficiency. A landmark study comparing these methods on 19 different sgRNAs in mammalian cells found stark discrepancies [6]. While T7E1 reported an average editing efficiency of 22%, targeted NGS revealed a much higher average efficiency of 68%. The study identified three major sources of T7E1 inaccuracy: it failed to detect activity for poorly performing sgRNAs (<10% by NGS), substantially underestimated the efficiency of highly active sgRNAs (>90% by NGS), and could not distinguish between sgRNAs with moderately similar T7E1 signals but dramatically different actual efficiencies by NGS [6].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of these two methods based on published data:

Table 1: Key Characteristics of T7E1 and NGS for Indel Detection

| Feature | T7E1 Assay | Targeted NGS |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Enzyme mismatch cleavage [2] | High-throughput sequencing [6] |

| Quantitation | Semi-quantitative [21] | Fully quantitative [6] |

| Reported Dynamic Range | Underestimates beyond ~30% efficiency [6] | Accurate across 0-100% efficiency [6] |

| Sensitivity | Lower; struggles with low-frequency and single-base mutations [2] [6] | High; can detect indels with VAF <1% [10] |

| Sequence Information | No | Yes; provides full spectrum of indel sequences [5] |

| Throughput | Low to medium | High |

| Cost & Accessibility | Low cost; accessible [5] | Higher cost; requires bioinformatics support [5] |

Other Notable Methods

While T7E1 and NGS are widely used, other methods offer a middle ground. Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) and Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) analyze Sanger sequencing chromatograms from edited samples using decomposition algorithms to quantify the spectrum and frequency of indels [4] [5]. These methods are more quantitative than T7E1 and less expensive than NGS, providing a good balance for many applications. However, their accuracy can be lower than NGS, and they may miscall alleles in complex edited clones [6] [4]. Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) offers extremely precise and quantitative measurement of specific edits using fluorescent probes but is generally limited to detecting pre-defined mutations rather than discovering novel indels [4].

Experimental Protocols for Core Methods

Detailed T7E1 Assay Protocol

- PCR Amplification: Design primers to amplify a 300-800 bp region surrounding the CRISPR-Cas9 target site. Perform PCR on purified genomic DNA from edited and wild-type control cells using a high-fidelity DNA polymerase.

- Product Purification: Purify the PCR products using a commercial PCR clean-up kit to remove enzymes, primers, and nucleotides. Quantify the DNA concentration.

- Heteroduplex Formation: In a thin-walled PCR tube, mix 200-400 ng of purified PCR product with an appropriate buffer. Denature the DNA at 95°C for 5-10 minutes and then re-anneal by slowly cooling the reaction from 95°C to 25°C at a rate of -0.1°C per second. This step facilitates the formation of heteroduplexes between wild-type and mutant strands.

- T7 Endonuclease I Digestion: To the re-annealed DNA, add NEBuffer 2 and 1 μL of T7 Endonuclease I enzyme. Incubate the reaction at 37°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Analysis by Gel Electrophoresis: Stop the reaction and resolve the digestion products on a 1.5-2% agarose gel. Include undigested PCR product as a control.

- Efficiency Calculation: Image the gel and use densitometry software to measure the band intensities. The indel frequency can be estimated using the formula: % Indel = 100 × (1 - √(1 - (b + c)/(a + b + c))), where a is the intensity of the undigested PCR product, and b and c are the intensities of the cleavage products [4].

Detailed NGS Workflow for Indel Detection

- Amplicon Library Preparation: Amplify the target region from genomic DNA with primers that include platform-specific adapter sequences. Use a high-fidelity polymerase and limit PCR cycles to minimize amplification bias.

- Library Purification and Quantification: Purify the amplicons and quantify them accurately using a method suitable for NGS library preparation.

- Sequencing: Pool equimolar amounts of libraries and sequence on an NGS platform.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Use tools to assess read quality.

- Read Alignment: Map sequencing reads to the reference genome using an aligner like BWA.

- Variant Calling: Identify insertions and deletions using a specialized indel caller. The choice of tool is critical, as performance varies significantly [20].

- Quantification: Calculate the frequency of each indel by dividing its count by the total number of reads at the target site.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural and logical steps involved in the T7E1 assay and Next-Generation Sequencing workflows, highlighting their fundamental differences.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Indel Detection

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| T7 Endonuclease I | Cleaves heteroduplex DNA at mismatch sites [2]. | Core enzyme for the T7E1 mismatch cleavage assay. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix | Amplifies target locus with minimal errors [4]. | Essential for both T7E1 and NGS amplicon library preparation. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Prepares amplicon libraries for sequencing. | Required for converting PCR products into sequencer-compatible format. |

| Variant Calling Software (e.g., GATK) | Identifies and quantifies indels from NGS data [20]. | Critical for bioinformatic analysis of NGS data. |

| ICE Analysis Tool | Decomposes Sanger traces to quantify editing [5]. | User-friendly alternative to NGS for indel characterization. |

The selection of an indel detection method is a critical determinant in the validation of CRISPR-Cas9 editing. The T7E1 assay serves as a rapid and economical tool for initial, qualitative assessments. However, its limitations in quantitation, sensitivity, and informational depth are significant. In contrast, targeted NGS provides a comprehensive, quantitative, and sensitive gold-standard analysis, albeit with higher resource requirements. The choice between them, or intermediate methods like ICE/TIDE, should be guided by the experimental context: the required precision, the number of samples, available budget, and technical expertise. As CRISPR applications advance toward clinical therapies, the demand for accurate and sensitive indel detection will only intensify, necessitating continued refinement of these methodologies and the development of even more robust and accessible validation tools.

Implementing T7E1 and NGS in the Lab: A Step-by-Step Workflow Guide

Within CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing research, accurately detecting insertion or deletion mutations (indels) is a critical step for validating editing efficiency. Among the various methods available, the T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay stands out for its cost-effectiveness and technical simplicity [5] [6]. This guide provides a standard protocol for the T7E1 assay and objectively compares its performance against next-generation sequencing (NGS) and other modern techniques for indel detection. The data demonstrates that while T7E1 is a valuable tool for initial screening, its limitations in accuracy and dynamic range make it less suitable for applications requiring precise, quantitative outcomes compared to sequencing-based methods [4] [6].

T7E1 Assay: Standard Step-by-Step Protocol

The T7E1 assay operates on the principle that the T7 Endonuclease I enzyme recognizes and cleaves heteroduplexed (mismatched) DNA at the sites of non-complementary base pairs [6] [22]. The following is a detailed protocol for assessing CRISPR-induced indel mutations.

The diagram below illustrates the complete T7E1 assay workflow.

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Step 1: CRISPR Delivery and Genomic DNA Extraction

- CRISPR Delivery: Introduce CRISPR-Cas9 components into your target cells using methods such as lentivirus transduction, plasmid transfection, or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery [3].

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 3 to 4 days post-transfection. Extract genomic DNA using a standard genomic extraction kit or a direct PCR kit [3] [6].

Step 2: PCR Amplification of Target Locus

- Primer Design: Design primers that flank the CRISPR target site to generate an amplicon of suitable length.

- Recommended Workflow: A nested PCR approach is often used for improved specificity and signal [3].

- First Round PCR: Perform 20 cycles to amplify an 800-1000 bp fragment encompassing the target site.

- Second Round PCR: Perform 30-40 cycles using primers internal to the first product to generate a final amplicon of approximately 500 bp.

- PCR Reaction: Use a high-fidelity PCR master mix. A sample 25 µL reaction volume can contain 1 µL of genomic DNA, 1 µL of each primer, 10.5 µL of nuclease-free water, and 12.5 µL of a 2X hot-start master mix [4].

Step 3: DNA Denaturation and Annealing

- Purification: Purify the final PCR product using a commercial gel and PCR clean-up kit [4].

- Heteroduplex Formation: Denature and re-anneal the purified DNA to form heteroduplexes between wild-type and indel-containing strands.

Step 4: T7E1 Digestion

- Enzymatic Digestion: Digest the heteroduplexed DNA with the T7E1 enzyme.

Step 5: Gel Electrophoresis and Analysis

- Visualization: Separate the digestion products by electrophoresis on a 1.2% to 1.5% agarose gel. Use a DNA stain such as ethidium bromide or GelRed for visualization [4] [3].

- Efficiency Calculation: Quantify the band intensities using software like ImageJ.

- Formula: The indel frequency can be estimated using the formula:

Indel % = [1 - (1 - (b + c)/(a + b + c))^{1/2}] × 100, where

ais the intensity of the undigested (parental) band, andbandcare the intensities of the cleaved products [23].

- Formula: The indel frequency can be estimated using the formula:

Indel % = [1 - (1 - (b + c)/(a + b + c))^{1/2}] × 100, where

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the key reagents and their functions required to perform a successful T7E1 assay.

Table 1: Key Reagents for the T7E1 Assay

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Description | Example Vendor/Product |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA Extraction Kit | Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from transfected cells. | Commercial kits (e.g., Macherey-Nagel Gel & PCR Clean-Up Kit) [4]. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix | Amplify the target genomic locus with high accuracy and yield. | Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (New England Biolabs) [4]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I Enzyme | The core enzyme that cleaves mismatched heteroduplex DNA. | T7 Endonuclease I (M0302, New England Biolabs) [4] [3]. |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis System | To separate and visualize cleaved and uncleaved DNA fragments. | Standard laboratory system with 1.2-1.5% agarose gel [3] [22]. |

| DNA Stain | For visualizing DNA bands under UV light. | Ethidium Bromide Solution or GelRed [4]. |

T7E1 vs. NGS and Other Methods: A Quantitative Comparison

Choosing the right validation method depends on the requirements for accuracy, throughput, and budget. The following diagram provides a logical framework for selecting the most appropriate indel detection method based on research goals.

The performance of the T7E1 assay is best understood when directly compared to other common indel detection methods. The following table summarizes key benchmarking data from comparative studies.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of CRISPR Indel Detection Methods

| Method | Reported Accuracy & Limitations | Quantitative Data vs. NGS (when available) | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| T7E1 Assay | Semi-quantitative. Tends to underestimate efficiency, especially above ~30% editing [6]. Poor detection of low-frequency indels (<10%) [6]. | In one study, T7E1 reported ~28% efficiency for two sgRNAs, while NGS revealed true efficiencies of 40% and 92% [6]. | Initial, low-cost screening during CRISPR optimization where sequence-level data is not required [5] [24]. |

| Sanger (ICE/TIDE) | Quantitative and sequence-specific. ICE shows high correlation with NGS (R² = 0.96) [5]. More accurate than T7E1 across a wider efficiency range [23]. | ICE provides an "ICE score" (indel frequency) comparable to NGS. In clone analysis, TIDE deviated by >10% from NGS in 50% of clones [6]. | Cost-effective validation providing a balance of sequence information and quantification without needing NGS [5]. |

| ddPCR / PCR-CE | Highly quantitative and sensitive. These methods are accurate when benchmarked against AmpSeq [24]. Excellent for detecting low-frequency edits and specific alleles. | In plant studies, both ddPCR and PCR-CE/IDAA methods showed high accuracy compared to the AmpSeq benchmark [24]. | Applications requiring absolute quantification, such as assessing allelic frequencies or low-abundance edits [4] [24]. |

| NGS (Amplicon Seq) | Gold standard. Highest accuracy and sensitivity for detecting a wide spectrum of indels and their sequences [5] [24]. | Used as the benchmark in comparative studies. Detects a broader range of indels and higher efficiencies missed by T7E1 [6]. | Final validation, characterization of heterogeneous editing outcomes, and when the fullest spectrum of data is required [5] [24]. |

The T7E1 assay remains a useful technique in the CRISPR toolkit due to its straightforward protocol and low cost. It provides a rapid means to confirm that genome editing has occurred, making it suitable for initial sgRNA screening or when resources are limited [5]. However, the experimental data clearly indicates that its semi-quantitative nature and limited dynamic range are significant drawbacks [6]. The assay systematically underestimates high editing efficiencies and can fail to detect low-frequency indels, potentially leading to the mischaracterization of sgRNA performance.

For robust, publication-quality validation of CRISPR editing efficiency, sequencing-based methods are superior. While Sanger sequencing coupled with decomposition algorithms like ICE offers a strong middle ground, targeted next-generation sequencing (Amplicon Seq) provides the most comprehensive and accurate picture of editing outcomes [5] [24]. The choice between T7E1, ICE/TIDE, and NGS should be a deliberate one, balancing the need for speed and cost against the critical requirements for quantitative accuracy and detailed sequence information in each specific research context.

Designing and Executing a Targeted Amplicon Sequencing (AmpSeq) Workflow for NGS

The accurate detection of insertion and deletion mutations (indels) is a cornerstone of genetic research, particularly in fields like CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing validation. For years, the T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay served as a widely adopted method for this purpose due to its cost-effectiveness and technical simplicity [6] [5]. This enzyme-based method recognizes and cleaves mismatched DNA heteroduplexes formed when wild-type and indel-containing strands hybridize, with the cleavage products visualized via gel electrophoresis [25].

However, a growing body of evidence reveals significant limitations in the T7E1 assay, including a low dynamic range, subjective quantification, and an inability to identify the exact sequence changes [24] [6]. Targeted Amplicon Sequencing (AmpSeq) using Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has emerged as a superior alternative, providing nucleotide-level resolution and superior sensitivity for quantifying genome editing outcomes [24] [26]. This guide objectively compares these methodologies and provides a detailed framework for implementing a robust AmpSeq workflow.

Performance Comparison: T7E1 Assay vs. Targeted Amplicon Sequencing

Direct benchmarking studies demonstrate critical performance differences between T7E1 and AmpSeq, influencing their suitability for indel detection research.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes key performance characteristics based on comparative studies:

| Feature | T7E1 Assay | Targeted Amplicon Sequencing (AmpSeq) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Cleavage of heteroduplex DNA [25] | High-throughput sequencing of target regions [26] [27] |

| Reported Accuracy | Often inaccurate; underestimates high efficiency edits [6] | High accuracy; considered the "gold standard" [24] [5] |

| Sensitivity | Low; fails to detect edits below ~5% or above ~30% efficiently [6] [5] | High; can detect low-frequency edits (<0.1% to >30%) [24] |

| Dynamic Range | Limited (~5-30% efficiency) [6] | Broad, capable of quantifying a wide range of editing efficiencies [24] |

| Information Output | Semi-quantitative indel frequency only [5] | Full spectrum of exact indel sequences and their frequencies [24] [5] |

| Throughput | Low to medium | High [27] |

| Best Application | Initial, low-cost screening during CRISPR optimization [5] | Final validation, sensitive quantification, and detailed characterization [24] [26] |

A 2018 study in Scientific Reports directly compared T7E1 with targeted NGS for 19 sgRNAs in mammalian cells [6]. The T7E1 assay reported an average editing efficiency of 22%, while NGS revealed a true average of 68%, with some sgRNAs achieving over 90% efficiency that T7E1 failed to accurately quantify [6]. A 2025 plant genomics study confirmed these findings, noting that different quantification methods, including T7E1, showed significant differences in quantified CRISPR edit frequencies compared to the AmpSeq benchmark [24].

Advantages and Drawbacks in Practice

- Advantages of T7E1: Its primary advantages are low cost per reaction and a fast, technically simple workflow that requires only standard laboratory equipment (PCR thermocycler and gel electrophoresis apparatus) [6] [5].

- Drawbacks of T7E1: Beyond its limited accuracy, the assay cannot determine the specific sequences of indels, which is critical for understanding the functional consequences of a mutation. Its performance is also impacted by DNA quality, the nature of the mismatch, and flanking sequence context [6].

- Advantages of AmpSeq: AmpSeq provides unparalleled detail and accuracy, detecting all mutation types (SNPs, indels) and their precise frequencies simultaneously. Its high sensitivity allows for the detection of rare variants and complex heterogeneous populations common in transient editing assays [24] [26] [27].

- Drawbacks of AmpSeq: The main constraints are higher cost, longer turnaround time, and the need for specialized equipment and bioinformatics expertise for data analysis [24] [5].

Designing a Targeted Amplicon Sequencing Workflow

A robust AmpSeq workflow consists of four core stages, from nucleic acid isolation to final data interpretation [27].

The Four-Step AmpSeq Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete end-to-end process for targeted amplicon sequencing.

Step 1: Sample Preparation

The process begins with the isolation of high-quality nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) from the sample source (e.g., edited cells, tissues, or microbes) [27]. The yield and purity of the extracted genetic material are critical for the success of all subsequent steps. For limited samples, specialized low-input protocols can be applied [27].

Step 2: Library Preparation

This is a crucial step where the target regions of interest are prepared for sequencing.

- Targeted PCR Amplification: Specific primers are designed to flank the genomic regions under investigation. These primers are used in a multiplex PCR to simultaneously amplify all target sequences, generating "amplicons" [27] [28].

- Adapter Ligation: The amplified products are then purified and "tagged" with sequencing adapters and sample-specific indices (barcodes) in a second PCR round [27]. This step allows the sequencer to recognize the fragments and enables the pooling of multiple libraries in a single sequencing run. Technologies like Paragon Genomics' CleanPlex can be used to purify libraries and reduce background noise [27].

Step 3: Sequencing

The pooled, adapter-ligated libraries are loaded onto a next-generation sequencer. Popular platforms include those from Illumina, Ion Torrent, or long-read technologies from PacBio or Oxford Nanopore [27] [29]. The choice of platform depends on the required read length, depth of coverage, and project budget.

Step 4: Data Analysis

The raw sequencing data (in FASTQ format) is processed using bioinformatics pipelines [27] [28].

- Read Alignment: Sequencing reads are aligned to a reference genome to determine their origin.

- Variant Calling: Specialized software compares the aligned sequences to the reference to identify genetic variants such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and indels [27].

- Genotyping: For each sample, the genotype at each marker is determined (e.g., homozygous reference, heterozygous, homozygous alternate) [28]. Tools like TASEQ can automate this process, outputting files ready for genetic analysis [28].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and reagents required to execute the AmpSeq workflow.

| Item | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Target-Specific Primers | Designed to flank genomic regions of interest; used in multiplex PCR for specific amplification [27] [28]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Ensures accurate amplification of target regions during PCR with minimal error rates. |

| NGS Library Preparation Kit | Contains enzymes and buffers for adapter ligation and index PCR (e.g., CleanPlex kits) [27]. |

| Solid-Phase Reversible Immobilization (SPRI) Beads | Used for size selection and purification of DNA fragments between workflow steps [27]. |

| Sequencing Adapters & Barcodes | Oligonucleotides ligated to amplicons, enabling sequencing platform recognition and sample multiplexing [27]. |

| Bioinformatics Tools (e.g., TASEQ, GATK) | Software for processing raw data, aligning reads, and calling variants [28]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing AmpSeq for CRISPR Validation

This protocol outlines the key steps for using AmpSeq to validate CRISPR-Cas9 editing, based on methodologies from recent literature [24].

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Cell/Tissue Collection: Harvest cells or tissue samples subjected to CRISPR-Cas9 editing and appropriate negative controls.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA using a standard spin-column or phenol-chloroform method. Quantify DNA concentration using a fluorometer and assess purity via spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8).

Primer Design and Library Construction

- Primer Design: Design primers to amplify a 200-300 bp region surrounding the CRISPR target site. Tools like MKDESIGNER can automate genome-wide primer design [28]. Ensure primers are specific and avoid secondary structures.

- Multiplex PCR: Perform the first PCR using target-specific primers to generate amplicons. The number of cycles should be optimized to avoid over-amplification.

- Library Indexing: Use a limited-cycle PCR to add platform-specific sequencing adapters and dual-index barcodes to the amplicons.

- Library QC: Pool the indexed libraries and purify them using SPRI beads. Quantify the final library pool using qPCR for accurate molarity and check the fragment size distribution on a bioanalyzer.

Sequencing and Data Analysis

- Sequencing: Dilute the library to the appropriate concentration and load it onto an NGS sequencer. Aim for a minimum of 50,000-100,000 reads per amplicon to ensure sufficient depth for detecting low-frequency indels [24].

- Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Demultiplexing: Assign sequences to individual samples based on their unique barcodes.

- Quality Control & Trimming: Use tools like Trimmomatic to remove low-quality reads and adapter sequences [28].

- Alignment: Map the quality-filtered reads to the reference genome using aligners like BWA [28].

- Variant Calling: Identify insertions and deletions using a variant caller like GATK HaplotypeCaller [28].

- Efficiency Calculation: Calculate the editing efficiency as the percentage of reads containing indels at the target site compared to the total aligned reads.

The choice between T7E1 and AmpSeq is fundamentally determined by the required level of analytical resolution. While T7E1 may suffice for initial, low-cost screening, Targeted Amplicon Sequencing provides the accuracy, sensitivity, and detailed sequence-level data essential for rigorous validation of genome editing experiments and other applications requiring precise variant detection [24] [6] [5]. By adopting the standardized AmpSeq workflow outlined in this guide, researchers can generate comparable, high-quality data that pushes the frontiers of genetic research and therapeutic development.

The success of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing experiments hinges on accurately assessing editing efficiency and outcomes. Among the various validation methods available, the T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) represent two fundamentally different approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The T7E1 assay serves as a rapid, cost-effective initial screening tool, while NGS provides comprehensive, nucleotide-level resolution of editing events. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods, supported by experimental data, to help researchers select the appropriate validation strategy based on their specific application needs, from rapid screening to in-depth analysis.

T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay

The T7E1 assay is an enzyme mismatch cleavage method that detects the presence of induced mutations without sequencing. The protocol begins with PCR amplification of the target genomic region from both edited and unedited (wild-type) control samples [30]. The amplified PCR products are then subjected to a denaturation and reannealing process, which involves heating and slow cooling. This step generates heteroduplex DNA molecules when indel-containing strands pair with wild-type strands, creating structural mismatches [6] [30]. These heteroduplexes are recognized and cleaved by the T7 Endonuclease I enzyme, which specifically targets and cuts at mismatch sites [6]. The reaction products are separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, where the cleavage products appear as smaller fragments. Editing efficiency is estimated by comparing the band intensities of cleaved versus uncleaved PCR products using densitometric analysis [30].

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

NGS-based validation, particularly targeted amplicon sequencing, involves high-throughput sequencing of PCR-amplified target regions to precisely identify mutations at nucleotide resolution [24] [31]. The process begins with genomic DNA extraction from edited cells, followed by PCR amplification of the target site using primers that incorporate partial Illumina sequencing adaptors [31]. A second PCR adds complete adaptors and sample-specific barcodes, enabling multiplexed sequencing [31]. The pooled libraries are then sequenced on platforms such as Illumina MiSeq, generating millions of reads that cover the target region with high depth [24] [31]. Bioinformatics tools like CRISPResso analyze the sequencing data, aligning reads to a reference sequence to precisely quantify the spectrum and frequency of indel mutations, including insertions, deletions, and complex rearrangements [31].

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows of T7E1 Assay and NGS-Based Validation. The T7E1 assay (top) follows a rapid biochemical process culminating in gel-based analysis, while NGS (bottom) involves extensive library preparation and bioinformatic processing for comprehensive mutation profiling.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data and Technical Specifications

Accuracy and Sensitivity Benchmarks

Multiple studies have systematically compared the performance of T7E1 and NGS for detecting CRISPR-induced mutations. When benchmarked against NGS—considered the "gold standard" due to its sensitivity and accuracy—the T7E1 assay shows significant limitations in quantitative accuracy [24] [6]. In a comprehensive 2025 benchmarking study, NGS demonstrated superior sensitivity capable of detecting editing efficiencies across a wide dynamic range, from less than 0.1% to over 30% across different sgRNA targets [24]. In contrast, the T7E1 assay consistently underestimated editing efficiency, particularly for highly active sgRNAs. For example, sgRNAs with greater than 90% editing efficiency by NGS appeared only moderately active (approximately 30-40%) by T7E1 analysis [6]. Furthermore, the T7E1 assay failed to detect editing entirely for poorly performing sgRNAs with less than 10% efficiency as measured by NGS [6].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of T7E1 vs. NGS for CRISPR Validation

| Parameter | T7E1 Assay | NGS-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Sensitivity | Limited; fails to detect edits <10% [6] | High; detects edits as low as <0.1% [24] |

| Dynamic Range | Limited; underestimates high efficiency edits (>30%) [6] | Broad; accurate quantification across full range (0-100%) [24] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Semi-quantitative; relative estimates only [21] | Highly quantitative; precise frequency measurements [24] |

| Indel Resolution | No sequence-level information [5] | Nucleotide-level resolution of all indel types [31] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Single target per reaction | Hundreds to thousands of targets simultaneously [32] |

| Reproducibility | Moderate; subjective band intensity measurement [6] | High; standardized bioinformatic pipelines [31] |

Information Content and Editing Outcomes

A critical difference between these methods lies in the type of information they provide about editing outcomes. The T7E1 assay only indicates the presence of mutations through cleavage efficiency but provides no information about the specific sequences of the indels [5] [30]. This is a significant limitation because different indel sequences can have varying functional consequences; for instance, in-frame deletions may preserve protein function while frameshift mutations typically result in gene knockouts [30]. In contrast, NGS provides comprehensive information about the exact sequences and frequencies of all indel types present in the sample [24] [31]. This includes the ability to detect complex mutations, multiple simultaneous edits, and precise quantification of frameshift versus in-frame mutations, which is essential for understanding the functional impact of editing experiments [31].

Experimental Protocols and Technical Considerations

Detailed T7E1 Assay Protocol

The T7E1 assay requires specific conditions for reliable results. Begin with PCR amplification of the target region using a high-fidelity DNA polymerase such as AccuTaq LA DNA Polymerase to prevent false positives from PCR errors [30]. The target amplicon should be approximately 500 bp, with the CRISPR target site positioned off-center to generate clearly distinguishable cleavage products [3]. Purify the PCR product and quantify using spectrophotometry. For heteroduplex formation, mix 200-400 ng of purified PCR product in an appropriate annealing buffer, denature at 95°C for 5-10 minutes, then cool slowly to room temperature (approximately 1-2 hours) or use a programmed thermal cycler with a gradual ramp from 95°C to 25°C [3] [30]. Digest the heteroduplex DNA with 1 μL T7 Endonuclease I in 1X NEBuffer 2 at 37°C for 30-90 minutes [3] [4]. Separate the digestion products on a 1.2-1.5% agarose gel and visualize with ethidium bromide or GelRed [3]. Calculate editing efficiency using the formula: % editing = [1 - (1 - (a + b)/(a + b + c))^0.5] × 100, where c is the intensity of the undigested PCR product band, and a and b are the intensities of the cleavage products [6].

Detailed NGS-Based Validation Protocol

For NGS-based validation, start by extracting high-quality genomic DNA from edited cells, including appropriate wild-type controls. Design primers to amplify 200-300 bp regions flanking the target site, incorporating Illumina adapter sequences (forward: 5'-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG-[locus-specific sequence]-3', reverse: 5'-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG-[locus-specific sequence]-3') [31]. Perform the first PCR with 30 ng genomic DNA using a high-fidelity polymerase under the following conditions: 98°C for 30 s, then 30 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72°C for 2 minutes [4]. Use a second PCR to add dual indices and complete adaptors with limited cycles (typically 8-10) to prevent excessive amplification bias [31]. Purify the libraries, quantify using fluorometry, and pool at equimolar ratios. Sequence on an Illumina MiSeq or similar platform with 2 × 250 bp paired-end reads to ensure sufficient overlap for accurate mutation calling [31]. Process the data through a bioinformatic pipeline such as CRISPResso2, which aligns reads to a reference sequence, quantifies indel frequencies, and characterizes mutation spectra [31].

Table 2: Practical Implementation Considerations for CRISPR Validation Methods

| Consideration | T7E1 Assay | NGS-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Hands-on Time | 1-2 days [5] | 3-7 days (including library prep and sequencing) [5] [31] |

| Technical Expertise | Basic molecular biology skills | Bioinformatics expertise required [5] |

| Equipment Needs | Standard molecular biology lab (thermocycler, gel electrophoresis) | NGS platform and computational resources [5] |

| Cost per Sample | Low [5] | High [5] |

| Sample Throughput | Low to moderate | High (multiplexing hundreds of samples) [32] |

| Controls Required | Wild-type DNA and no-enzyme control [30] | Wild-type DNA, negative control, and positive control if available [30] |

Matching Methods to Research Objectives

The choice between T7E1 and NGS should be guided by research goals, sample number, resources, and required data resolution. The T7E1 assay is ideal for initial gRNA screening during CRISPR system optimization when precise quantification is not critical [5]. Its low cost and rapid turnaround make it suitable for testing multiple gRNAs in parallel before committing to more resource-intensive validation methods [5] [30]. The assay works best for detecting moderate editing efficiencies (10-30%) in small sample sets where sequence-level information is unnecessary [6]. In contrast, NGS is essential for applications requiring precise mutation characterization, such as evaluating therapeutic editing accuracy, quantifying homozygous versus heterozygous editing, detecting complex mutations, and analyzing clonal populations [24] [31]. NGS is also the method of choice for large-scale studies where multiplexing provides cost efficiencies and for comprehensive off-target assessment when combined with specialized methods like GUIDE-seq or Digenome-seq [31].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for CRISPR Validation Methods

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| T7 Endonuclease I | Cleaves mismatched heteroduplex DNA | Commercial kits (Sigma-Aldrich T7E1 kit, NEB M0302) [30] [4] |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | PCR amplification without introducing errors | AccuTaq LA DNA Polymerase, Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Master Mix [30] [4] |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries | Illumina Nextera XT, customized amplicon kits [31] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Analysis of sequencing data | CRISPResso, CRISPResso2, custom pipelines [31] |

| Positive Control gRNA | Verification of experimental procedure | Pre-validated gRNA targeting housekeeping genes [30] |

| Negative Control gRNA | Distinguishing specific from non-specific effects | Non-targeting gRNA [30] |