Strategic Balance: Optimizing Cost and Accuracy in High-Throughput Screening Workflows

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on navigating the critical trade-off between computational/resource expenditure and data accuracy in High-Throughput Screening (HTS).

Strategic Balance: Optimizing Cost and Accuracy in High-Throughput Screening Workflows

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on navigating the critical trade-off between computational/resource expenditure and data accuracy in High-Throughput Screening (HTS). It covers foundational principles of Return on Computational Investment (ROCI), explores methodological advancements like automation and AI-driven screening, details troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls like false positives, and examines validation frameworks for new technologies such as 3D cell models and HT-ADME. The content synthesizes current industry practices and emerging trends to empower scientists in building more efficient, reliable, and cost-effective discovery pipelines.

The Fundamental Trade-Off: Understanding Cost vs. Accuracy in HTS

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Z'-factor and what value indicates an excellent assay? The Z'-factor is a key statistical parameter used to assess the quality and robustness of a High Throughput Screening (HTS) assay. It takes into account the dynamic range of the assay signal and the data variation from both positive and negative controls [1]. A Z'-factor between 0.5 and 1.0 is considered excellent [1]. This metric is distinct from the compressibility factor (Z-factor) used in thermodynamics [2] and the conversion factor (z-factor) used in geospatial data [3].

How can I identify "hits" reliably from my HTS data? Reliable hit identification requires a multi-step statistical and graphical review of the screening data to exclude results that fall outside quality control criteria [4]. The challenge is to distinguish true biologically active compounds from background assay variability, which can be introduced by automated compound handling, liquid transfers, and signal capture [4]. Systematic quality control procedures, like the Cluster Analysis by Subgroups using ANOVA (CASANOVA), can help identify and filter out compounds with multiple cluster response patterns to improve potency estimation [5].

What is ROCI and how does it optimize High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS)? ROCI stands for Return on Computational Investment. It is a central concept in a framework designed to optimally allocate computational resources in an HTVS pipeline that uses multi-fidelity models (models with varying costs and accuracy). The goal is to maximize the output—successful identification of molecular candidates with desired properties—relative to the computational cost invested, thereby balancing cost and accuracy effectively [6].

What are some common causes of inconsistent results in qHTS? In quantitative High Throughput Screening (qHTS), multiple concentration-response curves are typically obtained for each compound. Inconsistent results, where these curves fall into different clusters, can arise from several factors. These include systematic effects and artifacts, the chemical supplier, the institutional site preparing the chemical library, concentration-spacing, and the purity of the compound [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Z'-factor in HTS Assays

A low Z'-factor indicates that your assay may not be robust enough to reliably distinguish active compounds from inactive ones.

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High data variation | Inconsistent reagent dispensing, cell viability, or enzyme activity [4]. | Standardize reagent preparation and thawing procedures; ensure automated liquid handlers are calibrated [1]. |

| Small signal window | Suboptimal assay chemistry or reagent concentrations [1]. | Increase the difference between positive and negative control signals by optimizing detection chemistry (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence) [1]. |

| Systematic errors | Edge effects in microplates, drifts over time, or row/column effects [4]. | Use robust statistical methods during data processing to reduce the impact of these effects; inspect data graphically for patterns [4]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Z'-factor Calculation and Interpretation

- Run Control Wells: Include a sufficient number of positive control (e.g., a known activator/inhibitor) and negative control (e.g., no compound/vehicle) wells on every assay plate. A standard 384-well plate is often used for this purpose [1].

- Calculate Means and Standard Deviations: For each plate, calculate the average (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of the signal from both the positive and negative controls.

- Apply the Z'-factor Formula:

Z' = 1 - [ 3*(σ_positive + σ_negative) / |μ_positive - μ_negative| ] - Interpret the Result:

- Z' = 0.5 to 1.0: An excellent assay.

- Z' = 0.0 to 0.5: A marginal assay. It may be usable but likely requires optimization.

- Z' < 0.0: The assay is not reliable for screening, as the data distributions of the positive and negative controls overlap significantly [1].

Managing Computational Cost (ROCI) in Virtual Screening

High computational costs can bottleneck virtual screening campaigns, especially when using high-fidelity models on enormous molecular search spaces [6].

| Problem | Impact on ROCI | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Enormous search space | High-fidelity models are too slow/costly to run on all candidates [6]. | Implement a multi-fidelity pipeline: use fast, lower-cost models to filter the library before applying high-fidelity models [6]. |

| Suboptimal pipeline design | Resources are wasted on unpromising candidates [6]. | Formally apply an ROCI framework to optimally allocate computational budgets across different models, maximizing the number of true hits found per unit of computation [6]. |

| Inefficient data analysis | Slow processing delays iteration and decision-making. | Integrate automation, real-time data analytics, and cloud computing to process vast amounts of data more effectively [7]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Designing an Optimal HTVS Pipeline for ROCI

- Define the Screening Goal: Clearly state the target property or activity you are screening for.

- Assemble Model Inventory: List all available computational models (e.g., 2D QSAR, molecular docking, molecular dynamics). Note their relative computational cost and predictive accuracy.

- Formalize the ROCI Objective: Define what constitutes a "hit" and set the goal to maximize the number of confirmed hits given a fixed computational budget [6].

- Allocate Resources: Determine the optimal sequence of models and the number of compounds to process through each stage. The framework suggests this allocation is key to maximizing ROCI [6].

- Validate and Iterate: Use a small test set of compounds to validate the pipeline's performance and adjust the model sequence or allocation as needed.

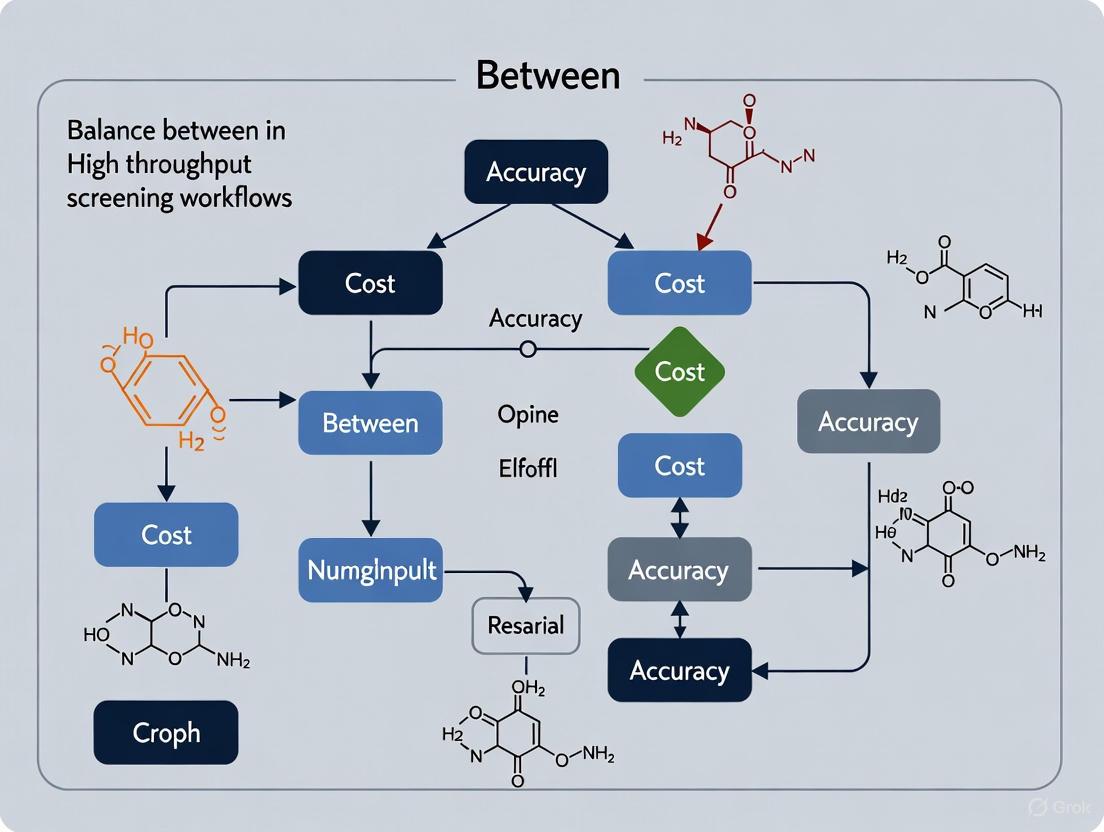

The following workflow visualizes the optimal decision-making process for a High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) pipeline designed to maximize Return on Computational Investment (ROCI).

Inconsistent Potency Estimates in qHTS

In qHTS, a single compound can yield multiple, highly variable concentration-response profiles (clusters), leading to unreliable potency estimates (e.g., AC50) [5].

| Problem | Evidence | QC Action |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple response clusters | A single compound's replicate curves show different shapes or potencies, like AC50 values varying by orders of magnitude [5]. | Apply a quality control procedure like CASANOVA to automatically identify and flag compounds with statistically significant multiple clusters [5]. |

| Confounded experimental factors | Clusters correlate with factors like the source of the compound library or the testing site [5]. | Document all known experimental metadata and test for associations with response patterns. |

| Unreliable potency (AC50) | Potency estimates for a flagged compound are untrustworthy for downstream analysis [5]. | Flag the compound for careful manual review or exclude its potency estimate from further analysis to improve overall data reliability [5]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Quality Control with CASANOVA

- Data Input: For each tested compound, collect all replicate concentration-response profiles from the qHTS experiment [5].

- Apply CASANOVA: Use the Cluster Analysis by Subgroups using ANOVA (CASANOVA) method. This procedure clusters the compound-specific response patterns into statistically supported subgroups [5].

- Identify Inconsistent Compounds: Compounds that are sorted into multiple, distinct clusters are classified as having "inconsistent" response patterns.

- Data Filtering: Sort out these inconsistent compounds. Proceed with potency estimation (e.g., AC50 calculation) only for compounds that display a single, consistent cluster of response patterns across repeats [5].

The diagram below outlines the key steps for performing quality control (QC) on quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS) data to ensure reliable potency estimation, using methods like CASANOVA.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key solutions and materials essential for developing and running robust HTS assays.

| Reagent / Material | Function in HTS |

|---|---|

| Chemical Compound Libraries | Collections of thousands to millions of small molecules used to screen for potential active compounds ("hits") against a biological target. They can be general or tailored to specific target families [1]. |

| Assay Kits (e.g., Transcreener) | Biochemical assay platforms that provide sensitive, mix-and-read detection for enzymes like kinases, GTPases, and PARPs. They are designed for simplicity and robustness in high-content campaigns [1]. |

| Microplates (96 to 3456 wells) | The miniaturized format that enables high-throughput testing. They allow for automated handling of thousands of samples simultaneously, drastically reducing reagent volumes and costs [1]. |

| Detection Reagents | Chemistries (e.g., for fluorescence, luminescence, TR-FRET, FP) that generate a measurable signal indicating biological activity or binding. The choice depends on the assay design and required sensitivity [1]. |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Reference compounds used to validate each assay plate. They define the maximum and minimum possible signals, enabling the calculation of quality metrics like the Z'-factor [1]. |

In the relentless pace of modern drug discovery, High-Throughput Screening (HTS) stands as a critical gatekeeper, capable of accelerating the path to new therapeutics or becoming a multi-million-dollar bottleneck. The pursuit of speed and cost-efficiency in processing vast compound libraries is perpetually balanced against the imperative for data accuracy. False positives, variability, and human error introduce costly delays, misleading research directions, and contribute to the high attrition rates in pharmaceutical development [8] [9]. This technical support center is designed to help researchers troubleshoot these pervasive challenges, providing actionable strategies to safeguard their workflows against errors that compromise both timelines and budgets.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High Rates of False Positives

Issue: A high number of false positives in primary screening is consuming resources and delaying the progression of true hits.

Background: False positives occur when compounds are incorrectly identified as "active" due to assay interference rather than genuine biological activity. Common causes include chemical reactivity, assay technology artifacts, autofluorescence, and colloidal aggregation [9].

Solution: A systematic, tiered approach is required to triage false positives.

Initial Triage with In-Silico Filters:

- Action: Apply computational filters, such as Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) filters, to your primary hit list [9].

- Methodology: Use cheminformatics software to flag compounds containing substructures known to cause frequent interference.

- Expected Outcome: Rapid elimination of a significant portion of promiscuous, non-lead-like compounds.

Orthogonal Assay Confirmation:

- Action: Re-test all remaining hits using a secondary assay based on a different detection technology (e.g., switch from a fluorescence intensity assay to a luminescence or mass spectrometry-based readout) [9].

- Methodology: Develop a low-throughput, mechanistically similar but technologically distinct assay for hit confirmation.

- Expected Outcome: Identification of compounds whose activity is technology-dependent versus those with genuine biological effects.

Counter-Screen and Dose-Response:

- Action: Perform a counter-screen against an unrelated target to identify non-selective compounds. Then, characterize confirmed hits with a dose-response curve to determine potency (IC₅₀/EC₅₀) [9] [10].

- Methodology: Use a 10-point, 1:3 serial dilution series to generate robust concentration-response data.

- Expected Outcome: Further refinement of the hit list to selective, potent compounds with quantifiable efficacy.

Preventative Measures:

- Optimize Assay Sensitivity: Implement high-sensitivity assays that provide a strong signal-to-background ratio (e.g., >6:1) and a high Z'-factor (>0.7), which improves the distinction between true actives and background noise [10].

- Use Lower Reagent Concentrations: High-sensitivity assays enable the use of lower enzyme concentrations (e.g., 10 nM instead of 100 nM), which not only reduces costs but also provides more accurate measurements of potent inhibitor IC₅₀ values, preventing the masking of weak but genuine inhibitors [10].

Guide 2: Managing High Inter- and Intra-User Variability

Issue: Screening results are inconsistent between different users or when the same user repeats the assay on different days.

Background: Manual processes in HTS are inherently variable. Even minor deviations in liquid handling, incubation times, or reagent preparation can lead to significant discrepancies in results, undermining reproducibility [8].

Solution:

- Automate Critical Steps:

- Action: Integrate automation for liquid handling, plate washing, and reagent dispensing.

- Methodology: Employ non-contact liquid handlers with integrated verification technology (e.g., DropDetection) to ensure dispensing accuracy and document any errors [8].

- Expected Outcome: Standardized liquid handling, drastically reduced human error, and enhanced reproducibility across users and sites.

- Implement Robust Process Controls:

- Action: Standardize all protocols with detailed, step-by-step instructions. Include clear quality control (QC) checkpoints.

- Methodology: On each plate, include control wells for both high (e.g., no inhibitor) and low (e.g., full inhibition) signals. Calculate the Z'-factor for each plate to statistically monitor assay performance [10].

- Expected Outcome: Real-time monitoring of assay robustness and early detection of procedural drift or failure.

The following workflow diagram outlines a standardized protocol to minimize variability and its impact on data interpretation.

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Data Management and Analysis Bottlenecks

Issue: The vast volume of multiparametric data generated by HTS is difficult to manage, store, and analyze effectively, slowing down the time to insight [8].

Background: Modern HTS, especially with high-content imaging, can produce terabytes of data. Without a structured plan for data management, researchers struggle to extract meaningful biological insights.

Solution:

- Automate Data Processing:

- Action: Implement automated data analysis pipelines for primary screening data.

- Methodology: Use built-in software from plate readers or specialized HTS data analysis platforms to automatically calculate percent activity, Z-scores, and perform normalization immediately after data acquisition [8].

- Leverage AI and Machine Learning:

- Action: Integrate AI-driven tools for advanced pattern recognition and hit triage.

- Methodology: Apply machine learning models trained on historical HTS data to prioritize compounds with a higher probability of success, flag potential false positives, and analyze complex high-content imaging data for subtle phenotypic changes [11] [12] [13].

- Expected Outcome: Faster, more accurate hit identification and a significant reduction in the data analysis burden on scientists.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common sources of false positives in HTS, and how can I quickly identify them?

The most common sources are assay technology artifacts (e.g., compound interference with fluorescence signals), chemical reactivity (e.g., covalent modification of protein targets), and colloidal aggregation (where compounds form aggregates that non-specifically inhibit enzymes) [9]. Quick identification strategies include:

- Visual Inspection: Review the raw data for unusually high signals or patterns that align with specific compound plates.

- Structural Alerts: Use in-silico tools to scan for known nuisance compounds (PAINS) [9].

- Dose-Response Behavior: Genuine inhibitors typically show a clean sigmoidal dose-response curve. Compounds that show a "flat" or irregular curve may be acting through interference.

FAQ 2: How can I improve the reproducibility of my cell-based HTS assays when moving from 2D to 3D models?

The transition to more physiologically relevant 3D models (like spheroids and organoids) introduces complexity, which can challenge reproducibility. Key strategies include:

- Standardize Culture Conditions: Use commercial, standardized extracellular matrices and ensure consistent cell seeding densities.

- Quality Control 3D Structures: Before screening, use imaging to confirm uniform size and morphology of spheroids or organoids.

- Automate Assay Steps: As with biochemical assays, automate the dispensing of compounds and reagents to 3D cultures to minimize handling variability [11].

- Tiered Workflows: Start with simpler, viability-based readouts for primary screening in 3D models, reserving more complex, high-content phenotyping for confirmed hits to manage data complexity [11].

FAQ 3: What are the cost implications of poor assay sensitivity, and how can better sensitivity save money?

Poor assay sensitivity has a direct and significant impact on research budgets. Low-sensitivity assays require the use of more enzyme and other reagents to generate a detectable signal. As illustrated in the table below, a high-sensitivity assay can reduce enzyme consumption by up to 10-fold, leading to substantial cost savings, especially when screening large compound libraries [10].

Table: Cost and Performance Impact of Assay Sensitivity

| Factor | Low-Sensitivity Assay | High-Sensitivity Assay (e.g., Transcreener) |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Required | 10 mg | 1 mg |

| Cost per 100,000 wells | Very High | Up to 10x lower |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio | Marginal | Excellent (>6:1) |

| IC₅₀ Accuracy | Moderate (enzyme concentration too high) | High (enzyme concentration near inhibitor IC₅₀) |

| Ability to run under Km (initial-velocity conditions) | Limited | Fully enabled [10] |

FAQ 4: How is AI transforming the management of HTS errors and data?

AI and machine learning are revolutionizing HTS by shifting from purely experimental to more predictive workflows. Key transformations include:

- In-Silico Triage: AI can predict drug-target interactions with high fidelity, shrinking the size of physical compound libraries that need to be screened by up to 80%. This concentrates resources on the most promising candidates and reduces reagent costs [12].

- Error Reduction: AI-driven pattern recognition can analyze complex, multi-parametric data from high-content screens to identify subtle phenotypes and flag potential outliers or artifacts that the human eye might miss [11] [13].

- Predictive Modeling: AI models can predict ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties early, helping to eliminate compounds likely to fail later in development due to toxicity or poor pharmacokinetics [14] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Robust HTS Assays

| Item | Function in HTS | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Handling Systems | Automated, precise dispensing of nanoliter to microliter volumes of compounds and reagents. | Key for reproducibility. Look for non-contact dispensers with drop-detection technology to verify dispensing accuracy [8]. |

| High-Sensitivity Assay Kits (e.g., Transcreener) | Detect minimal product formation in enzymatic assays (e.g., ADP, GDP). | Enables use of low enzyme/substrate concentrations, saving costs and providing more accurate kinetic data under initial-velocity conditions [10]. |

| 3D Cell Culture Scaffolds | Provide a structural support for cells to form physiologically relevant 3D structures like spheroids. | Crucial for developing more predictive disease models. Ensure compatibility with automation and imaging systems [11]. |

| Fluorescent Probes & Reporters | Enable detection of biological activity (e.g., calcium flux, gene expression, apoptosis). | Choose probes with high brightness and minimal spectral overlap for multiplexing. Be aware of compound autofluorescence interference [9]. |

| Quality Control Reagents | Compounds for high (100% activity) and low (0% activity) control wells on every plate. | Essential for calculating the Z'-factor and statistically validating the performance of each assay plate in real-time [10]. |

The following diagram maps the strategic approach to mitigating HTS errors, connecting specific problems with their modern, technology-driven solutions.

In modern drug discovery, High Throughput Screening (HTS) serves as a critical engine for identifying potential therapeutic candidates. The core challenge for researchers lies in optimizing a fundamental trade-off: maximizing the accuracy and physiological relevance of data while minimizing the substantial costs inherent to the process. A typical HTS workflow is governed by four primary cost drivers: infrastructure (capital equipment), reagents and consumables, data management, and specialized personnel. Understanding and managing these drivers is essential for the financial and scientific success of any screening program. This guide provides troubleshooting and strategic insights to help researchers navigate these complex cost-accuracy dynamics.

HTS Cost Drivers: Quantitative Analysis

The financial footprint of an HTS operation can be broken down into initial capital expenditure and recurring operational costs. The tables below summarize key cost components and market data.

Table 1: HTS Infrastructure and Service Cost Examples

| Cost Category | Specific Item/Service | Cost Example | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure | Acoustic Liquid Handler (e.g., Beckman Echo) | $189/hour [15] | For-profit external rate at Stanford's core facility. |

| Screening Robot | $220.50/hour [15] | For-profit external rate at Stanford's core facility. | |

| Automated Liquid Handler (e.g., Agilent Bravo) | $150/hour [15] | For-profit external rate at Stanford's core facility. | |

| High-Throughput Cytometer (e.g., iQue 5) | N/A [16] | Capital investment; launched in 2025 to increase speed. | |

| Full Screening Service | HTS Service (14,400 compounds) | $10,837.24 [17] | Academic rate from University of Colorado (2015). Includes assay optimization, screening, and cherry-picking. |

| Pilot Screen (1,000 compounds) | $1,354.66 [17] | Academic rate from University of Colorado (2015). | |

| Personnel | Lead Scientist (Consulting) | $225/hour [15] | For-profit external rate for database consulting. |

| Automation Tech Screening Fee | $6,000/screen [15] | Flat fee for screen setup and operation. |

Table 2: HTS Market Context and Financial Drivers

| Aspect | Market Data & Impact on Cost Drivers |

|---|---|

| Global Market Size | The market was estimated at \$28.8 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 11.8% to reach \$50.2 billion by 2029 [18]. |

| Leading Cost Segment | Instruments (liquid handling systems, detectors) are the largest product segment, accounting for 49.3% of the market in 2025 [16]. |

| Consumables Segment | Reagents and kits are a major recurring cost driver, holding a 36.5% share of the products and services market [19]. |

| Key Growth Technology | Cell-based assays are a leading technology segment (39.4% share), reflecting a driver of cost due to their complexity and higher physiological relevance [19]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Infrastructure and Capital Costs

Problem: High upfront investment in automated equipment is a major barrier, especially for smaller labs.

Solution: Consider a phased approach and leverage core facilities.

- Start Small: Begin with a pilot screen using 384-well plates, which are widely supported and easier to optimize, before transitioning to higher-density formats like 1536-well plates [20].

- Utilize Core Facilities: For sporadic screening needs, using a university or commercial core facility is far more cost-effective than maintaining in-house equipment. The hourly rates for specialized instruments provide access to cutting-edge technology without the capital outlay [17] [15].

FAQ: How can I justify the high capital cost of an HTS instrument to my department? Build a business case that focuses on long-term throughput and efficiency. Highlight how automation reduces manual labor, increases reproducibility, and lowers the cost-per-data point over time. Citing the dominant market share of instruments (49.3%) can reinforce that this is a standard, essential investment for competitive drug discovery [16].

Reagents and Consumables

Problem: Reagent costs are prohibitively high, especially for complex cell-based assays.

Solution: Implement miniaturization and careful plate selection.

- Adopt Low-Volume Assays: Transitioning assays to 384-well or 1536-well low-volume plates can drastically reduce reagent consumption. Acoustic liquid handling technology can accurately dispense volumes as low as 2.5 nL, leading to a 10-fold reduction in compound and reagent use [20].

- Optimize Plate Selection: The choice of microplate is a critical cost and accuracy factor. Use the following checklist [21]:

- Color: Use black plates for fluorescence (reduces crosstalk) and white for luminescence (enhances signal).

- Well Bottom: Use flat bottoms for microscopy and bottom-reading; round bottoms for easier mixing and retrieval.

- Surface Treatment: Ensure proper treatment (e.g., tissue-culture treated for adherent cells) to support cell health and assay performance, avoiding costly failed runs.

FAQ: I need to run a fluorescence-based cell assay for high-content imaging. What microplate should I use? For this application, a black microplate with a clear, film-bottom (e.g., µClear) is often ideal. The black walls minimize background fluorescence and well-to-well crosstalk, while the clear film bottom is optimized for high-resolution microscopy [21].

Data Management and Analysis

Problem: HTS generates massive datasets that are difficult to manage and analyze, leading to potential false positives/negatives.

Solution: Integrate AI/ML tools and focus on statistical quality.

- Leverage Artificial Intelligence: AI is rapidly being adopted to analyze massive HTS datasets with unprecedented speed and accuracy. It helps optimize compound libraries, predict molecular interactions, and reduce time to identify hits [16].

- Use the Z' Factor: Routinely calculate the Z' factor as a key metric for assay quality. A high Z' factor (≥0.5) indicates a robust assay with a good signal-to-noise window, which reduces the rate of false positives and negatives and saves resources spent on validating poor leads [20].

FAQ: We keep getting false positives that waste our validation resources. How can we improve our assay quality? This is a classic problem often stemming from poor assay design. Focus on the "Magic Triangle of HTS": the interconnectedness of Time, Cost, and Quality [20]. Investing more time in upfront assay development and optimization (Quality) will reduce costly follow-up on false leads (Cost) later. Use statistical measures like the Z' factor during development to ensure you have a robust assay before committing to a full screen [20].

Personnel and Expertise

Problem: Lack of in-house expertise leads to inefficient screen design and operation.

Solution: Invest in training and strategic collaboration.

- Engage Early: Consult with HTS specialists during the project's experimental design phase, not just at the execution stage. Their expertise in assay automation and optimization is crucial for a successful and cost-effective screen [17].

- Understand True Costs: Personnel costs are not just salaries. When calculating project budgets, factor in the time scientists spend on data analysis, hit validation, and follow-up screens, which can be more time-consuming than the primary screen itself [20].

FAQ: Our screening project is taking much longer than anticipated, but the actual screening was fast. Why? This is a common oversight. The actual screen runtime is often a minor part of the total project timeline. The most time-consuming steps are typically assay development and adaptation, data analysis and interpretation, and hit validation [20]. When planning, create a timeline that accounts for these critical pre- and post-screening activities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for HTS Assays

| Item | Function in HTS | Key Selection Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assay Kits | Provide physiologically relevant data for target identification and toxicity profiling; the leading technology segment [19]. | Pre-optimized for specific targets (e.g., Melanocortin Receptor family kits [16]); choose kits that maximize predictive accuracy for clinical outcomes. |

| Microtiter Plates | The physical platform that hosts the miniaturized biochemical or cell-based reactions. | Color (clear, white, black), well density (384, 1536), well bottom shape (F, U, V), and surface treatment (TC-treated, non-binding) must be matched to the assay and detector [21]. |

| Liquid Handling Reagents | Buffers, diluents, and detection chemicals required for assay execution. | A major recurring cost; demand high-quality, reproducible reagents to ensure data reliability across thousands of reactions [19]. |

| CRISPR-based Screening Systems (e.g., CIBER) | Enable genome-wide functional studies, such as identifying regulators of vesicle release, with high efficiency [16]. | Used for target identification and validation; select based on editing efficiency and application-specific design (e.g., barcoding for complex phenotypes). |

Workflow and Strategic Diagrams

HTS Cost-Accuracy Optimization

HTS Assay Development Pathway

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common HTS Challenges

This guide provides targeted solutions for frequent issues encountered in High-Throughput Screening (HTS) workflows, framed within the critical balance of cost and accuracy in drug discovery.

FAQ: Assay Performance and Validation

1. How can I reduce false positives and negatives in my HTS assays?

False positives (inactive compounds identified as active) and false negatives (active compounds missed) waste resources and overlook potential therapeutics [22]. Key strategies include:

- Improved Assay Design: Incorporate robust controls and counterscreens to identify compounds that interact non-specifically with assay components rather than the target [22].

- Optimized Signal-to-Noise: During development, test multiple variables to find parameters that maximize the difference between positive and negative controls, reducing the chance of misclassification [23].

- Data Analysis Refinement: Employ analytical pipelines that can normalize for systematic errors and identify patterns indicative of interference [22].

2. My assay results are variable between users and runs. How can I improve reproducibility?

Variability arises from biological differences, reagent inconsistency, and human error [22].

- Standardize Protocols: Create highly detailed, step-by-step protocols to minimize inter-user variability [8].

- Implement Automation: Automated liquid handling standardizes workflows, reduces human error, and enhances reproducibility across users, assays, and sites [8]. Systems with in-built verification, like DropDetection technology, further ensure dispensing accuracy [8].

- Rigorous Quality Control: Establish strict quality control for reagents and instrument calibration [24]. A key metric is the Z'-factor, which assesses the quality of an assay based on the separation between positive and negative controls. A Z'-factor > 0.5 is generally desirable for a robust assay [23].

3. What are the critical parameters to validate for a new HTS assay?

Assay validation confirms that an assay is reliable for its intended purpose. Essential parameters to validate include [25] [22]:

- Specificity: The assay accurately measures only the intended target.

- Accuracy and Precision: The closeness of measurements to the true value and their consistency, respectively.

- Linearity and Range: The assay provides accurate results across a defined range of concentrations.

- Detection and Quantitation Limits: The lowest amount of analyte that can be detected or reliably quantified.

- Robustness: The assay's performance is unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters.

FAQ: Data Management and Analysis

4. How should I handle heteroscedasticity (dose-dependent variance) in my qHTS data?

In quantitative HTS (qHTS), the variability in the observed response may increase with the dose [26]. Ignoring this can bias results.

- Diagnose the Issue: Perform a simple linear regression of the log of the sample variance on the dose. A significant slope indicates heteroscedasticity [26].

- Use Robust Estimation: Instead of standard Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), use estimation methods robust to variance structure and outliers. Preliminary Test Estimation (PTE) methodology can automatically adapt to the underlying variance, providing better control of false discovery rates while maintaining statistical power [26].

- Weighted Fitting: Consider using Iterated Weighted Least Squares (IWLS) by modeling the variance as a function of dose, though this may perform poorly when variances are nearly constant [26].

5. Our HTS data analysis is a bottleneck. How can we accelerate it?

HTS generates terabytes to petabytes of data, creating computational pressure [24].

- Leverage GPU Acceleration: GPUs use parallel processing to handle thousands of calculations simultaneously, accelerating tasks like genomic sequence alignment by up to 50x compared to CPU-only methods [24].

- Automate Data Pipelines: Use specialized software to manage the complete data lifecycle, from collection and processing to analysis [24].

- Implement AI and Machine Learning: AI algorithms can detect patterns and correlations in massive datasets, prioritize experiments, and optimize conditions, turning raw data into actionable predictions faster [24].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Assay Development

Protocol 1: Plate Uniformity Assessment for HTS Assay Validation

This protocol evaluates signal variability and separation across assay plates, a cornerstone for ensuring reproducible and high-quality data [25].

1. Objective: To assess the uniformity and adequacy of the signal window for detecting active compounds.

2. Key Signals to Measure:

- "Max" Signal: The maximum possible signal in the assay design (e.g., uninhibited enzyme activity, maximal cellular response to an agonist).

- "Min" Signal: The background or minimum signal (e.g., fully inhibited enzyme, basal cellular signal).

- "Mid" Signal: A signal midway between Max and Min, typically induced by an EC~50~ or IC~50~ concentration of a control compound [25].

3. Procedure (Interleaved-Signal Format):

- Plate Layout: Use a predefined plate layout where "Max," "Min," and "Mid" signals are systematically interleaved across the entire plate (e.g., in a repeating H, M, L pattern across columns). Use the same layout on all days of the test.

- Replicates and Duration: For a new assay, run the study over 3 days using independently prepared reagents. For transferring a validated assay, a 2-day study may suffice [25].

- Execution: Run the assay under standard screening conditions, including the DMSO concentration that will be used in production screening.

4. Data Analysis:

- Calculate the Z'-factor for each plate to statistically quantify the assay's robustness and separation window.

- Analyze the data for spatial patterns or drifts across the plate that might indicate non-uniformity.

Protocol 2: Assessing Reagent Stability for Robust HTS

Unstable reagents are a major source of assay failure and wasted resources [25].

1. Reaction Stability Over Time:

- Conduct time-course experiments for each incubation step to determine the range of acceptable times.

- This helps define a flexible and robust protocol that can tolerate minor logistical delays [25].

2. Reagent Storage Stability:

- Test the stability of all critical reagents (commercial and in-house) under their proposed storage conditions (e.g., frozen, refrigerated).

- If reagents will undergo multiple freeze-thaw cycles, test their stability after a similar number of cycles [25].

3. DMSO Compatibility:

- Run the validated assay with a concentration range of DMSO (e.g., 0% to 10%).

- Perform this test early, as all subsequent validation experiments should use the chosen DMSO concentration [25]. For cell-based assays, it is recommended to keep the final DMSO concentration under 1% unless higher tolerance is specifically validated [25].

Table 1: Key Statistical Metrics for HTS Assay Validation and Analysis

| Metric | Target Value | Purpose & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Z'-factor | > 0.5 [23] | Assesses the quality and separation band of an assay. A higher score indicates a more robust assay with a larger window for detecting activity. |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | < 10% [23] | Measures the dispersion of data points (e.g., among replicate wells). A low CV indicates high precision and low well-to-well variability. |

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) | Controlled via robust statistical methods (e.g., PTE) [26] | The proportion of false positives among all declared active compounds. Controlling FDR is critical for prioritizing high-quality hits without being overwhelmed by false signals. |

Table 2: Cost-Benefit Analysis of Technologies for Improving HTS Accuracy

| Technology | Impact on Accuracy & Reproducibility | Impact on Cost & Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handling | Reduces human error and inter-user variability; provides in-process verification (e.g., drop detection) [8]. | Enables miniaturization, reducing reagent consumption and costs by up to 90% [8]. Increases throughput. |

| GPU-Accelerated Computing | Enables more complex, accurate data analysis and modeling; reduces analytical bottlenecks [24]. | Speeds up data analysis from days to minutes; allows exploration of larger experimental datasets [24]. |

| AI & Machine Learning | Improves predictive modeling for hit identification; optimizes experimental design [24]. | Reduces late-stage attrition by improving early candidate selection; streamlines experimental design [24] [22]. |

Workflow Visualization

HTS Assay Validation Workflow

Robust HTS Data Analysis Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for HTS Assay Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in HTS | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Control Compounds (Agonists/Antagonists) | Generate "Max," "Min," and "Mid" signals for assay validation and plate controls [25]. | Must be pharmacologically well-characterized and highly pure. Stability under assay conditions must be confirmed. |

| Enzymes / Cell Lines | The primary biological target of the screening campaign. | For enzymes: understand kinetics and substrate specificity [23]. For cells: use relevant, stable, and reproducible models [23]. |

| Detection Reagents (Fluorescent, Luminescent) | Generate the measurable signal corresponding to target activity [23]. | Choose based on sensitivity, signal-to-noise ratio, and compatibility with detectors and other reagents (e.g., avoid spectral overlap). |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | Universal solvent for storing and dispensing compound libraries [25]. | Final concentration in the assay must be validated for biological compatibility (e.g., <1% for cell-based assays) to avoid solvent-induced toxicity [25]. |

Strategic Levers for Efficiency: Methodologies that Enhance Accuracy While Containing Costs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why might my primary uHTS data show high signal variability across assay plates? High signal variability in uHTS often stems from inadequate plate uniformity assessment or reagent instability. To ensure robustness, perform a 3-day plate uniformity study using an interleaved-signal format that systematically measures "Max," "Min," and "Mid" signals across all plates [25]. This validates the assay's signal window and identifies inconsistencies in liquid handling or reagent performance. Additionally, confirm the stability of all reagents under storage and assay conditions, including testing their durability through multiple freeze-thaw cycles if applicable [25].

Q2: Our workflow uses acoustic droplet ejection (ADE). How can we ensure data quality during compound transfer? Acoustic droplet ejection promotes screening quality by minimizing compound carryover and waste while providing non-contact, precise liquid transfer [27]. To ensure data quality, implement regular calibration and validation of your ADE instruments. Furthermore, integrate custom software to harness the information generated by the ADE instrumentation, allowing for meticulous tracking of transfer operations and early detection of deviations [27].

Q3: How can we balance computational cost and accuracy in our high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) pipeline? Balancing this trade-off requires an optimal decision-making framework for your HTVS pipeline. You can maximize the return on computational investment (ROCI) by constructing a pipeline that intelligently allocates resources to multi-fidelity models—using faster, less accurate models for initial filtering and reserving high-fidelity, costly calculations for the most promising candidates [6]. Data-driven approaches, including machine learning models trained on affordable density functional theory (DFT) descriptors, can also overcome this cost-accuracy trade-off [28] [29].

Q4: What is a key consideration when transferring a validated HTS assay to a new laboratory? A key requirement for assay transfer is to conduct a abbreviated plate uniformity study. Unlike the 3-day study for a new assay, a validated assay being transferred to a new lab requires a 2-day plate uniformity assessment to confirm that the transfer is complete and reproducible [25]. This should be followed by a replicate-experiment study to verify consistent performance in the new environment [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common uHTS Workflow Problems and Solutions

Problem 1: Inconsistent Triggering of Automated Workflow Steps

- Symptoms: Workflow steps sometimes run and sometimes don't, or external data source changes fail to trigger the workflow.

- Causes: This can be caused by field validation errors, insufficient user permissions, or workflow conditions not being met [30]. Changes made directly in an external data source (like Airtable) may not propagate triggers to your workflow automation platform [30].

- Solutions:

- Use the platform's "workflow history" or "run history" feature to compare successful and failed runs, looking for patterns in the trigger data [30] [31].

- Review all "Only continue if" or conditional logic statements in your workflow to ensure they are correctly configured [30].

- Make changes through your application's interface instead of directly in the external data source, or use the data source's native automation to trigger a webhook [30].

Problem 2: Workflow Starts but Does Not Complete

- Symptoms: The workflow initiates but halts before finishing all actions.

- Causes: Common causes include missing data for required fields, permission errors accessing referenced records, or external service issues (e.g., webhook timeouts) [30].

- Solutions:

- Use the workflow history to identify the last successful action and the error message of the failed action [30].

- Verify that all required fields are populated before the action that fails [30].

- Check the configuration of webhook endpoints or other external service connections for accuracy and responsiveness [31].

Problem 3: Poor Data Quality in Primary uHTS

- Symptoms: High intra-plate or inter-plate variability, leading to an inability to reliably identify active compounds.

- Causes: Inadequate assay validation, reagent instability, or DMSO incompatibility.

- Solutions:

- Conduct a full plate uniformity and signal variability assessment as outlined in the table of performance metrics below [25].

- Determine reagent stability under both storage and daily operating conditions [25].

- Perform a DMSO compatibility test early in assay development, typically testing concentrations from 0% to 10%, though for cell-based assays, it is recommended to keep the final concentration under 1% unless higher tolerance is proven [25].

Step-by-Step Debugging Process for HTS Workflows

Follow this systematic approach to isolate and resolve issues in your screening workflow [30] [31]:

- Use History as Your Primary Tool: Access your workflow's run history. Examine recent runs for error messages, failed actions, or missing runs where execution was expected.

- Test Manually with Simple Data: For on-demand workflows, use action buttons with known test data. For automatic workflows, create test records designed to trigger the process and monitor the history immediately.

- Isolate the Problem Area: Identify the specific step where the failure occurs. Temporarily disable subsequent actions to isolate the issue and test individual components with minimal data.

- Review Logic and Configuration: Check all trigger conditions and field mappings. Verify that dynamic data references are valid and that external service configurations (e.g., for webhooks or emails) are correct.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Key Experimental Protocol: Plate Uniformity Assessment

This protocol is essential for validating the performance of a new uHTS assay prior to a full screening campaign [25].

Methodology:

- Plate Format: Use an Interleaved-Signal Format for 96- or 384-well plates.

- Signals:

- Max Signal: Represents the maximum assay response (e.g., uninhibited enzyme activity for a binding assay, or maximal agonist response).

- Min Signal: Represents the background or minimum response (e.g., signal in the absence of enzyme substrate, or basal signal for an agonist assay).

- Mid Signal: An intermediate response, typically generated using an EC~50~ concentration of a control agonist/inhibitor.

- Procedure: Independently prepare reagents and run the assay over three separate days. On each day, use plates with a pre-defined layout where "Max," "Min," and "Mid" signals are systematically interleaved across the entire plate. The same plate format and concentrations must be used on all days.

- Data Analysis: Calculate key performance metrics, such as the Z'-factor, for each day and across all days to assess the robustness and separation power of the assay.

HTS Performance Metrics Table

The following table summarizes key quantitative metrics used to validate assay performance for uHTS, derived from plate uniformity studies [25].

| Metric | Description | Target Value for uHTS | Calculation / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z'-Factor | A measure of assay quality and separation power between Max and Min signals. | ≥ 0.5 | Z' = 1 - (3*(SD~max~ + SD~min~) / |Mean~max~ - Mean~min~| ) |

| Signal Window | The dynamic range between the Max and Min signals. | ≥ 2 | Also known as Assay Window. |

| Coefficient of Variation | Measures intra-plate variability for control signals. | < 10% | CV = (Standard Deviation / Mean) * 100 |

| % Recovery of Correlation Energy (%E~corr~) | In virtual screening, predicts when multi-reference methods are needed; a key metric for accuracy [28]. | Varies by system | Used to evaluate the performance of computational diagnostics. |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and their functions in a typical uHTS workflow.

| Item | Function in uHTS Workflow |

|---|---|

| Assay Plates (96-, 384-, 1536-well) | The standardized microtiter formats that enable highly parallel processing of reactions using automated liquid handlers [25]. |

| Acoustic Droplet Ejection (ADE) Liquid Handler | Enables precise, non-contact transfer of library compounds in the nanoliter range to create "assay-ready" plates, minimizing waste and carryover [27]. |

| DMSO-Compatible Reagents | Assay components must maintain stability and function at the final DMSO concentration used for compound delivery (typically recommended to be under 1% for cell-based assays) [25]. |

| Validated Chemical Promoters | In catalyst screening, these are used to diversify the chemical space and modify the properties of a benchmark catalyst system (e.g., In~2~O~3~/ZrO~2~) to identify performance enhancements [29]. |

| Multi-fidelity Computational Models | In virtual screening, these are models with varying costs and accuracy used in a tiered pipeline to optimally allocate computational resources and maximize return on investment [6]. |

Workflow Visualization

Tiered HTS Workflow from Primary to Confirmation

Systematic Troubleshooting Methodology

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting High Throughput Screening (HTS) Assay Variability

Problem: Inconsistent or irreproducible results in high-throughput screening assays.

| Step | Action & Purpose | Underlying Cause & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify liquid handler precision [8] | Cause: Sub-microliter dispensing inaccuracies. Solution: Use instruments with integrated volume verification (e.g., DropDetection technology). |

| 2 | Audit environmental factors [32] | Cause: Electrical noise from equipment. Solution: Isolate sensitive electronics from welders/heavy machinery; use power conditioners. |

| 3 | Inspect consumables & reagents | Cause: Lot-to-lot reagent variability or degraded reagents. Solution: Implement strict reagent QC; use single, large lot for entire screen. |

| 4 | Standardize protocols [8] | Cause: Inter-operator variability from manual processes. Solution: Automate all workflow steps; document standardized protocols. |

This systematic approach isolates common variables, moving from instrumentation to environmental factors and reagents. Automation is a key solution to eliminate user-induced variability at its root [8].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Robotic System Stoppages

Problem: Industrial or laboratory robot stops unexpectedly or will not initiate a cycle.

| Step | Action & Purpose | Documentation & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check teach pendant for error codes [32] [33] | Record all fault codes and history. Essential first step for diagnosis. |

| 2 | Confirm all safety mechanisms [32] | Ensure gates, guards, and emergency stops are disengaged/closed. |

| 3 | Inspect end-effector (gripper/tool) [32] | Check for wear (e.g., split suction cups), air pressure, or electrical failure. |

| 4 | Perform a power cycle [33] | Turn the system off and on to clear registers and reset flags. |

| 5 | Run diagnostic cycles [33] | Execute 50+ cycles to observe for intermittent faults and repeatability issues. |

This logical sequence prioritizes simple, common solutions before escalating to complex diagnostics, minimizing downtime [32] [33].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our automated HTS system is generating vast amounts of data. How can we manage and analyze it effectively?

A: Automated data management and analytics are crucial. Integrate software that automates data capture, processing, and storage [34] [8]. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms can analyze these massive datasets for pattern recognition and predictive analytics, significantly accelerating the time to insight [16] [35].

Q2: What is the most overlooked factor when implementing lab automation?

A: Beyond technical and cost challenges, a critical yet overlooked factor is health equity and ethical implications. It is vital to ensure that these technological advancements benefit all sections of society equitably and do not exacerbate disparities for disadvantaged populations [34]. Proactively addressing these concerns builds trust and facilitates successful implementation.

Q3: How can we justify the high initial investment in laboratory robotics and automation?

A: Justification is based on the long-term Return on Investment (ROI). Key financial benefits include [34] [36] [35]:

- Major Cost Reduction: Automation enables miniaturization, reducing reagent consumption by up to 90% [8].

- Throughput & Labor: 24/7 operation increases output and optimizes labor costs.

- Error Reduction: Minimizing costly errors and rework improves overall operational efficiency.

Q4: Our robotic system has an intermittent fault that is difficult to replicate. How should we proceed?

A: Intermittent faults require a methodical approach [32]:

- Extended Observation: Allow for a period of prolonged system monitoring.

- Check for Noise: Investigate electrical noise spikes from nearby factory equipment.

- Inspect Cables: Examine high-flex cables for broken wires or internal damage that may only occur in specific positions.

- Document Everything: Keep a detailed log of when the fault occurs and under what conditions to identify patterns.

Q5: What is the difference between a closed and open TLA (Total Laboratory Automation) system?

A: The key difference is connectivity and vendor flexibility [35]:

- Closed Systems (e.g., Roche CCM) can only connect to specific devices, typically from the same manufacturer.

- Open Systems (e.g., Abbott GLP, Siemens Aptio) can connect various heterogeneous instruments from multiple companies, offering greater flexibility.

Experimental Protocol: Validating a Miniaturized HTS Assay

Purpose: To establish a robust, automated, and miniaturized High-Throughput Screening assay in a 1536-well plate format, reducing reagent use and operational expenses while maintaining data accuracy.

Methodology:

Assay Development & Reagent Preparation:

- Prepare all reagents according to standard protocols. Centrifuge briefly to ensure homogeneity.

- Key Control: Include positive (e.g., known agonist) and negative (e.g., buffer only) controls on every assay plate.

Automated Liquid Handling:

- Use a non-contact liquid handler (e.g., I.DOT Liquid Handler) to dispense sub-microliter volumes (1-2 µL) of assay buffer and compounds into 1536-well plates [8] [37].

- Critical Step: Utilize the instrument's built-in volume verification (e.g., DropDetection) to confirm dispensing accuracy for each run [8].

Initiation & Incubation:

- Using the liquid handler, add the biological target (e.g., cells, enzyme) to initiate the reaction.

- Seal the plates and incubate under defined conditions (temperature, CO₂, humidity) for the required time.

Detection & Readout:

- Feed plates to an automated detector/reader (e.g., a high-content imager or plate spectrophotometer) integrated into the workflow [16].

Data Acquisition & Automated Analysis:

- Collect raw data and process it using an automated data pipeline.

- Apply algorithms for hit identification (e.g., values >3 standard deviations from the negative control mean) [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS

| Item | Function in HTS |

|---|---|

| Liquid Handling Systems | Automates precise dispensing and mixing of small sample volumes (down to nanoliters) for consistent assay setup [16] [8]. |

| Non-Contact Dispenser | Uses positive displacement or ink-jet technology to dispense sub-microliter volumes without cross-contamination, crucial for miniaturization [8] [37]. |

| Cell-Based Assays | Provides physiologically relevant screening models that replicate complex biological systems for more predictive drug discovery [16]. |

| Detectors & Readers | Automated instruments (e.g., spectrophotometers, cytometers) that capture biological signals from assays in high-density plates [16]. |

| CRISPR-based Screening System | Enables genome-wide functional studies to identify genes or regulators involved in disease mechanisms [16]. |

Supporting Data for Strategic Planning

High Throughput Screening Market Growth & Cost Drivers

| Segment | 2025 Estimate (USD) | 2032 Projection (USD) | CAGR | Primary Growth Driver |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global HTS Market [16] | 26.12 Billion | 53.21 Billion | 10.7% | Need for faster drug discovery & automation tech advances. |

| HTS Instruments Segment [16] | 12.88 Billion (49.3% share) | - | - | Advancements in automation & precision in drug discovery. |

| Cell-Based Assays Segment [16] | 8.73 Billion (33.4% share) | - | - | Focus on physiologically relevant screening models. |

This data underscores the significant and growing investment in HTS technologies, validating the focus on automation.

Cost-Benefit Analysis of Automation Implementation

| Factor | Manual / Pre-Automation | Post-Automation | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reagent Consumption | High (e.g., 10+ µL/well) | Low (e.g., 1-2 µL/well), up to 90% reduction [8] | Major cost savings; enables miniaturization. |

| Administrative Task Time | High (e.g., 8+ hours/week) | Low (e.g., 70% reduction) [38] | Frees skilled staff for strategic work. |

| Data Reproducibility | Low (<30% unable to reproduce others' work [8]) | High (standardized workflows) | Increases trust in data & reduces rework. |

| Error Rate | Higher (human error in repetitive tasks) | Lower (minimized manual intervention) [35] | Reduces false positives/negatives & wasted resources. |

Leveraging AI and Machine Learning for Smarter, More Targeted Screening Campaigns

High Throughput Screening (HTS) remains a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, yet researchers continually face the fundamental challenge of balancing escalating costs against the imperative for greater predictive accuracy [11]. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is transforming this landscape, enabling smarter, more focused screening campaigns. This technical support center provides practical guidance for scientists navigating the implementation of these advanced technologies, with a constant focus on optimizing the cost-accuracy equation in your HTS workflows.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can AI realistically reduce the cost of my high-throughput screening campaigns?

AI drives cost reduction through several concrete mechanisms. It enables virtual screening, allowing you to prioritize the most promising compounds from vast libraries for physical testing, drastically reducing reagent and consumable use [39] [40]. Furthermore, AI optimizes experimental design, helping to predict the minimal number of data points and replicates needed for statistically robust results, thereby avoiding wasted resources [41]. By improving hit quality, AI reduces the downstream costs associated with validating false positives and optimizing poor-quality leads [42].

Q2: What are the most common data-related challenges when integrating ML into an existing HTS workflow, and how can I overcome them?

The most frequent challenges involve data quality, quantity, and integration. Key issues and their solutions include:

- Challenge: Inconsistent or Noisy Data. HTS data can suffer from high variability, which confuses ML models.

- Solution: Implement rigorous quality control (QC) metrics at the point of data generation. For cell-based assays, the Z'-factor is a widely adopted statistical parameter for assessing assay quality and suitability for HTS; a Z'-factor > 0.5 is generally acceptable [43].

- Challenge: Insufficient Data for Training. Some ML models, particularly deep learning, require very large datasets.

- Solution: Leverage techniques like transfer learning, where a model pre-trained on a large, public dataset is fine-tuned with your smaller, specific dataset [41].

- Challenge: Siloed and Incompatible Data. HTS data, imaging data, and chemical data are often stored in separate systems with inconsistent metadata.

- Solution: Invest in a unified data management platform that enforces the use of standardized metadata schemas (e.g., defining cell line, passage number, assay conditions in a consistent format) to ensure data from different experiments can be integrated and understood by AI models [44].

Q3: My AI model for predicting compound activity performed well in validation but fails in the lab. What could be wrong?

This classic "generalization" problem often stems from a mismatch between the training data and real-world biological complexity.

- Cause 1: Over-reliance on Biochemical Assay Data. If your model was trained solely on simplified biochemical target data, it may fail to predict activity in a more physiologically relevant cellular environment [11].

- Cause 2: The "Black Box" Problem. Many complex AI models are not interpretable, so you cannot understand the reasoning behind their predictions, making it hard to diagnose failure.

- Solution: Prioritize the use of interpretable ML models (e.g., Random Forest, which can provide feature importance scores) or employ explainable AI (XAI) techniques to uncover which molecular features the model is using for its predictions [45] [40]. This can reveal if the model is learning biologically relevant patterns or spurious correlations.

Q4: Are there specific AI techniques for HTS when I have very limited labeled data for a new target?

Yes, several ML paradigms are designed for such data-scarce scenarios.

- Few-Shot Learning: These algorithms are specifically designed to learn effectively from a very small number of examples by leveraging prior knowledge [41].

- Transfer Learning: As mentioned above, this involves taking a model already trained on a large, general-purpose chemical library (e.g., ChEMBL) and fine-tuning it with your small, target-specific dataset [41] [40].

- Utilizing Pre-Trained Models: Several companies and research groups offer cloud-based AI platforms with pre-trained models for tasks like binding affinity prediction or ADMET property forecasting (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity). You can input your novel compounds directly into these platforms to get predictions without building a model from scratch [42].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Correlation Between AI-Predicted Hits and Experimental Validation

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Resolution Steps |

|---|---|---|

| High false positive rate from AI virtual screen. | Training data does not reflect the biological complexity of the validation assay (e.g., trained on 2D cell data, validated in 3D). | 1. Re-train model using data from more physiologically relevant 3D cell models or primary cells [11].2. Apply multi-task learning, training the model on multiple assay types simultaneously to improve robustness [41]. |

| High false negative rate; AI misses known active compounds. | Algorithmic bias or imbalanced training data where active compounds are underrepresented. | 1. Curate training data to ensure a balanced representation of active and inactive compounds.2. Use synthetic minority over-sampling technique (SMOTE) or similar to address class imbalance.3. Experiment with different ML algorithms less prone to bias from imbalanced data. |

| Model performance degrades over time as new data is added. | Model Drift: The underlying patterns in the new experimental data have shifted from the original training set. | 1. Implement a continuous learning pipeline where model performance is monitored against new data.2. Establish a schedule for periodic model re-training with the most recent, consolidated data [40]. |

Issue: Inefficient Integration of AI into an Automated HTS Workflow

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Resolution Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Data transfer bottlenecks between automated liquid handlers, imagers, and the AI analysis server. | Lack of interoperability and standardized data formats between different hardware and software systems. | 1. Implement a centralized, cloud-based data lakehouse to ingest data from multiple sources in near real-time [44] [40].2. Use API-based integrations for instrument control and data transfer instead of manual file exports.3. Adopt ISA (Investigation, Study, Assay) framework standards for metadata to ensure consistency. |

| AI/ML predictions are too slow to inform real-time screening decisions. | Model is too computationally complex or computational resources are inadequate. | 1. For real-time needs, develop a simplified, surrogate model that approximates the larger model's predictions faster.2. Utilize high-performance computing (HPC) clusters or cloud GPU instances for model inference.3. Implement a batch processing strategy where predictions are run on queued compounds overnight. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and tools are critical for developing and validating AI-enhanced screening campaigns.

| Reagent/Tool | Function in AI-Driven HTS | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 3D Cell Models (Spheroids, Organoids) | Provides physiologically relevant data for training AI models, improving clinical translatability and reducing late-stage attrition [11]. | Throughput vs. Complexity: Balance the higher biological relevance of organoids with the practical throughput needs of primary screens. |

| CRISPR-Based Screening Tools | Enables genome-wide functional genomics screens, generating massive, high-quality datasets on gene function and drug mechanism of action for AI analysis [16]. | Use barcoded systems (e.g., CIBER) to allow for highly multiplexed tracking of cellular responses, enriching data dimensionality for ML [16]. |

| High-Content Imaging Reagents | Generate multi-parametric data on cell morphology and signaling, providing a rich feature set for phenotypic screening and training deep learning models [11]. | Opt for multiplexed and label-free technologies where possible to maximize data content while minimizing perturbation. |

| AI-Driven Design Software | Platforms from companies like Schrödinger, Insilico Medicine, and Exscientia use AI for de novo molecular design and optimization, creating novel compounds to test [42]. | Ensure the platform's molecular generation rules align with your synthetic chemistry capabilities to ensure proposed compounds are feasible. |

| Unified Lab Data Platform | Software (e.g., Labguru, Mosaic) that connects instruments, manages samples, and structures metadata, creating the clean, integrated data foundation required for effective AI [44]. | Prioritize platforms with embedded AI assistants for smarter search, experiment comparison, and workflow generation. |

Experimental Workflows & Protocols

Protocol 1: A Tiered AI-HTS Workflow for Balanced Cost and Accuracy

This protocol outlines a strategic approach to integrate AI at multiple stages, maximizing output while controlling resource expenditure.

Workflow for Balanced Cost and Accuracy

Detailed Methodology:

AI-Powered Virtual Screening:

- Objective: Drastically reduce the physical screening library size.

- Procedure: Utilize pre-trained or in-house ML models (e.g., Random Forest, Graph Neural Networks) to score and rank all compounds in your virtual library (1M+ compounds) based on predicted activity against your target [39] [41].

- Cost-Accuracy Balance: Select only the top 1-5% of predicted hits for physical screening. This step yields the highest cost savings by minimizing wet-lab expenses [40].

Focused Experimental Primary Screening:

- Objective: Experimentally confirm AI predictions.

- Procedure: Perform the primary HTS assay on the AI-prioritized compound subset. Use highly miniaturized formats (e.g., 1536-well plates) and automated liquid handling to maximize efficiency [16] [11].

- Data Capture: Ensure robust data capture with standardized metadata for every well.

AI-Enhanced Hit Triage:

- Objective: Filter out promiscuous or undesirable hits and cluster remaining hits by chemical structure.

- Procedure: Input the primary screening hit data into an AI clustering algorithm (e.g., using t-SNE or UMAP). Integrate results with historical data on compound toxicity and pan-assay interference (PAINS) filters to prioritize the most promising chemical series [41].

In-Depth Secondary Profiling:

- Objective: Assess selectivity and initial functional activity.

- Procedure: Subject the triaged hit clusters to a panel of secondary assays, which may include counter-screens against related targets, cytotoxicity assays, and high-content imaging to capture phenotypic data [11].

Generative AI for Lead Optimization:

- Objective: Improve the potency and drug-like properties of confirmed hits.

- Procedure: Feed the chemical structures and associated secondary assay data of your hits into a generative AI model (e.g., a Generative Adversarial Network or a Transformer-based model). The AI will propose novel, optimized molecular structures with improved predicted properties (e.g., binding affinity, solubility, metabolic stability) [42] [40].

- Synthesis & Testing: Synthesize a focused set of these AI-designed compounds for testing.

Validation in Translational Models:

- Objective: Confirm efficacy in models with high clinical predictive value.

- Procedure: Test the optimized lead compounds in complex, biologically relevant systems such as patient-derived organoids or 3D tissue models [11]. This step, while more expensive, is crucial for de-risking projects before committing to costly in vivo studies and is supported by regulatory shifts favoring human-relevant models [16].

Protocol 2: Implementing a QC Metric for HTS Data Quality for ML Readiness

Robust data quality is non-negotiable for reliable AI models. This protocol details the calculation of the Z'-factor, a key QC metric.

HTS Data QC for AI Workflow

Detailed Methodology:

Assay Plate Design:

- On each assay plate, include a sufficient number of wells (e.g., n≥16) for both a positive control (signal with maximum response) and a negative control (signal with minimum or baseline response) [43].

Data Collection:

- Run the HTS assay according to your established protocol.

- Record the raw signal data for all control wells.

Z'-Factor Calculation:

- For the positive control wells, calculate the mean (μpositive) and standard deviation (σpositive).

- For the negative control wells, calculate the mean (μnegative) and standard deviation (σnegative).

- Apply the Z'-factor formula: Z' = 1 - [ 3*(σpositive + σnegative) / |μpositive - μnegative| ] [43].

Interpretation:

- Z' > 0.5: An excellent assay robust enough for HTS and AI model training.

- 0 < Z' ≤ 0.5: A marginal assay that may introduce noise into AI models.

- Z' < 0: An unacceptable assay. The screen should not proceed, and the assay must be re-optimized before generating data for AI.

Systematically applying this QC step ensures the foundational data used to train and validate your AI models is of high quality, directly impacting the reliability and accuracy of your screening outcomes.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Common Liquid Handling and Evaporation Issues

Problem: High well-to-well variability, particularly edge-well effects ("edge effect"), and inconsistent data.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Evaporation | Inspect plate for higher signal in perimeter wells; measure volume loss in edge wells over time. | Use microplates with lids or seals; employ low-evaporation lids; adjust incubation times; consider humidity-controlled environments [46]. |

| Liquid Handling Inaccuracy | Visually inspect wells for inconsistent menisci; use a colored dye to test volume dispensing accuracy. | Calibrate automated liquid handlers regularly; use anti-clogging tips; optimize pipetting speed and mixing steps; account for reagent dead volume [46]. |

| Cell Seeding Irregularity | Check cell distribution under a microscope; measure coefficient of variation (CV) in a control assay. | Gently stir cell suspension during plating to prevent settling; use automated dispensers designed for cell suspensions [47]. |

Guide 2: Mitigating Biological and Assay Performance Problems

Problem: Poor cell health, low signal-to-noise ratio, or high false-positive rates in miniaturized cell-based assays.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Cell Number / Reagent Concentration | Perform a titration experiment for cells and key reagents to establish a dose-response curve. | Optimize cell seeding density and reagent concentration for the smaller well volume; ensure the final assay volume is scaled down appropriately (e.g., 35 µL for 384-well, 8 µL for 1536-well) [47]. |

| Assay Interference (False Positives) | Run a counter-screen with a different readout technology (e.g., luminescence if primary screen was fluorescence) [48]. | Include controls to identify compound aggregation, autofluorescence, or quenching; use assay reagents designed to reduce nonspecific interference (e.g., adding BSA or detergents) [48]. |

| Loss of Phenotype in Miniaturized Format | Compare key assay parameters (Z' factor, signal window) between 96-well and miniaturized formats. | Re-optimize critical steps like transfection time and reagent-to-DNA ratios specifically for the higher-density plate [47]. Validate with a known control compound. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary cost benefits of moving from a 96-well to a 384- or 1536-well format?

The savings are substantial and multi-faceted. Miniaturization directly reduces consumption of expensive reagents, compounds, and precious cells. For example, a screen using iPSC-derived cells (costing ~$1,000 per 2 million cells) would require 23 million cells in a 96-well format for 3,000 data points. The same screen in a 384-well format uses only 4.6 million cells, saving nearly $9,000 on cells alone, not including associated savings on media and other reagents [46]. Furthermore, it increases throughput, allowing more experiments to be run in the same amount of time [49].

Q2: How do I validate that my miniaturized assay is robust enough for high-throughput screening (HTS)?

A key metric for validation is the Z' factor, a statistical measure of assay robustness. A Z' factor > 0.5 is generally considered excellent for HTS. For instance, an optimized luciferase transfection assay in a 384-well plate achieved a Z' factor of 0.53, deeming it acceptable for HTS [47]. Other critical validation steps include demonstrating a linear response for the readout (e.g., with a luciferase calibration curve), establishing a sufficient signal-to-background ratio, and ensuring high intra- and inter-plate reproducibility [47] [48].

Q3: My assay uses primary cells, which are low-yield and sensitive. Can I still miniaturize it effectively?

Yes, and this is one of the most powerful applications of miniaturization. Research has successfully demonstrated the transfection of primary mouse hepatocytes in 384-well plates, achieving optimal transfection with as few as 250 cells per well [47]. This makes studies with rare or patient-derived primary cells far more feasible by drastically reducing the cell burden.

Q4: What are the biggest pitfalls when scaling down an assay, and how can I avoid them?

The most common pitfalls are evaporation, liquid handling inaccuracies, and failure to re-optimize biology [46].

- For evaporation: Use sealed plates and consider environmental controls.

- For liquid handling: Invest time in calibrating and validating your automated systems for very low volumes.