Reproducibility vs Replicability in Science: A Clear Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article clarifies the critical distinction between reproducibility (obtaining consistent results using the same data and code) and replicability (obtaining consistent results across studies with new data) in scientific research.

Reproducibility vs Replicability in Science: A Clear Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article clarifies the critical distinction between reproducibility (obtaining consistent results using the same data and code) and replicability (obtaining consistent results across studies with new data) in scientific research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the historical context and terminology confusion, provides actionable methodologies for implementing rigorous practices, analyzes the causes and costs of the reproducibility crisis, and offers frameworks for validating research through synthesis. The guide concludes with essential takeaways for enhancing research transparency and reliability in biomedical and clinical fields.

Defining the Pillars: Unraveling Reproducibility and Replicability in Modern Science

The terms "reproducibility" and "replicability" represent distinct but interconnected concepts in the scientific method, though their definitions have historically caused confusion across different disciplines. A 2019 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report specifically addressed this terminology problem to establish clearer standards for scientific research. This whitepaper adopts the precise framework advanced by NASEM, defining reproducibility as "obtaining consistent computational results using the same input data, computational steps, methods, code, and conditions of analysis" and replicability as "obtaining consistent results across studies aimed at answering the same scientific question, each of which has obtained its own data" [1] [2] [3]. The essential distinction is that reproducibility involves the same data and code, while replicability requires new data collection [3].

These concepts are fundamental to building a cumulative body of reliable scientific knowledge. When scientific results are frequently cited in textbooks and inform policy or health decisions, the stakes for validity are exceptionally high [1]. This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a technical framework for understanding and implementing these core principles, complete with methodologies, visualizations, and practical toolkits to enhance research rigor.

Core Concepts and Terminology

Distinguishing Between Reproducibility and Replicability

The terminology in this field has been characterized by inconsistent usage across scientific communities. As identified by Barba (2018), there are three predominant patterns of usage for these terms [2]:

- Category A: The terms "reproducibility" and "replicability" are used with no distinction between them.

- Category B1: "Reproducibility" refers to using the original researcher's data and computer codes to regenerate results, while "replicability" refers to a researcher collecting new data to arrive at the same scientific findings.

- Category B2: "Reproducibility" refers to independent researchers arriving at the same results using their own data and methods, while "replicability" refers to a different team arriving at the same results using the original author's artifacts.

The National Academies report deliberately selected the B1 definitions to bring clarity to the field, establishing a consistent framework that researchers across disciplines can adopt [2]. This framework aligns with the definitions used by Wellcome Open Research, which further introduces a third related term: repeatability, defined as when "the original researchers perform the same analysis on the same dataset and consistently produce the same findings" [4].

Conceptual Relationship

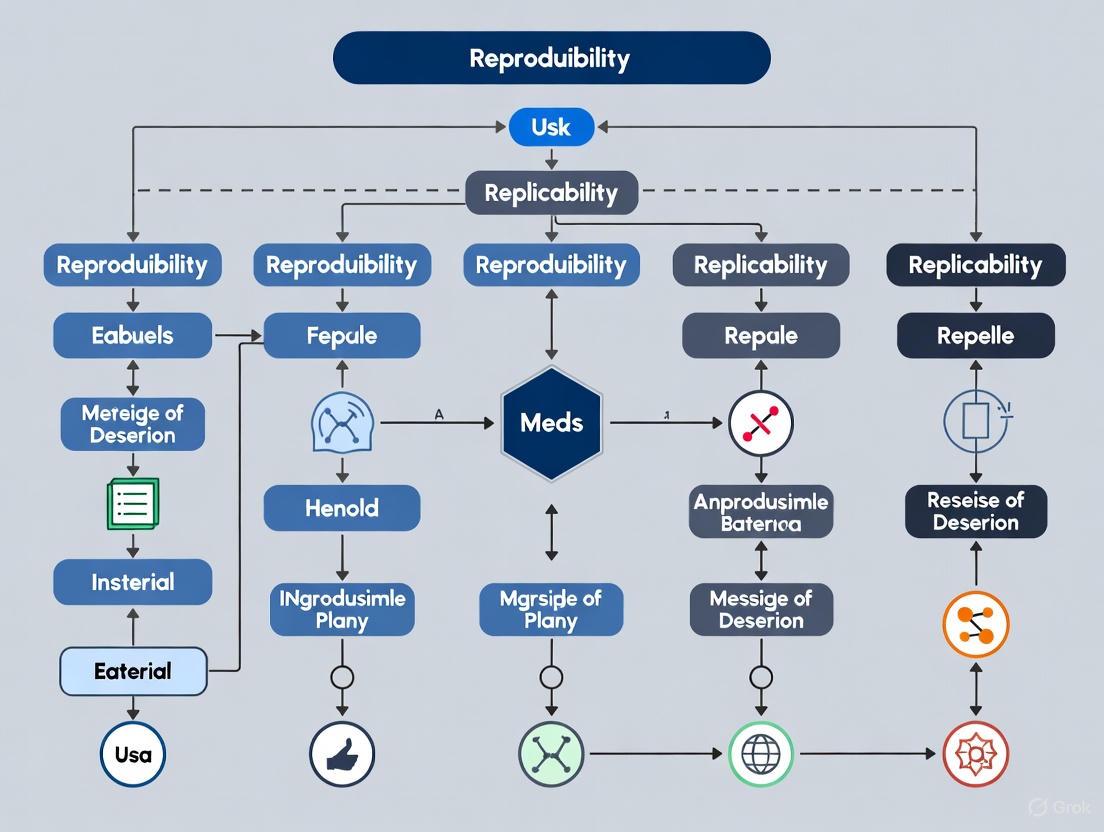

The relationship between these verification processes in scientific research can be visualized as a progression of independent confirmation:

This conceptual framework illustrates how scientific findings gain credibility through increasingly independent verification processes. It's important to note that a successful replication does not guarantee that the original scientific results were correct, nor does a single failed replication conclusively refute the original claims [5]. Multiple factors can contribute to non-replicability, including the discovery of unknown effects, inherent variability in systems, inability to control complex variables, or simply chance [5].

The Reproducibility and Replicability Landscape: Quantitative Evidence

Evidence from Large-Scale Assessments

Several systematic efforts have assessed the rates of reproducibility and replicability across scientific fields. The following table summarizes key findings from major replication initiatives:

Table 1: Replication Rates Across Scientific Disciplines

| Field | Replication Rate | Assessment Methodology | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychology | 36-39% | Replication of 100 experimental and correlational studies | Open Science Collaboration (2015) [5] |

| Biomedical Science (Preclinical Cancer Research) | 11-20% | Replication of landmark findings | Begley & Ellis (2012) [5] |

| Economics | 61% | Replication of 18 studies from top journals | Camerer et al. (2016) [6] |

| Social Sciences | 62% | Replication of 21 systematic social science experiments | Camerer et al. (2018) [5] |

A 2016 survey published in Nature provided additional context, reporting that more than 70% of researchers have attempted and failed to reproduce other scientists' experiments, and more than half have been unable to reproduce their own [6]. The same survey found that 52% of researchers believe there is a significant 'crisis' of reproducibility in science [6].

Contemporary Researcher Perspectives

A 2025 survey of 452 professors from universities across the USA and India provides insight into current researcher perspectives on these issues [6]. The findings reveal both national and disciplinary gaps in attention to reproducibility and transparency in science, aggravated by incentive misalignment and resource constraints.

Table 2: Researcher Perspectives on Reproducibility and Replicability (2025 Survey)

| Survey Dimension | Key Findings | Regional/Domain Variations |

|---|---|---|

| Familiarity with Concepts | Varying levels of familiarity with reproducibility crisis and open science practices | Differences observed between USA and India researchers, and between social science and engineering disciplines [6] |

| Institutional Factors | Misaligned incentives and resource constraints identified as significant barriers | Compound inequalities identified that haven't been fully appreciated by open science community [6] |

| Confidence in Published Literature | Mixed confidence in work published within their fields | Cultural and disciplinary differences affect perceived reliability of research [6] |

| Proposed Solutions | Need for culturally-centered solutions | Definitions of culture should include both regional and domain-specific elements [6] |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Computational Reproducibility Verification Protocol

For computational reproducibility, the following methodological protocol ensures that results can be consistently regenerated:

Objective: To verify that the same computational results can be obtained using the same input data, code, and conditions of analysis.

Materials and Reagents:

- Original dataset(s) with complete metadata

- Analysis code (preferably version-controlled)

- Computational environment specifications

- Documentation of all analytical steps

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain the original research data from repositories or supplementary materials.

- Environment Setup: Recreate the computational environment using containerization (Docker, Singularity) or virtual environments.

- Code Execution: Run the analysis code in the recreated environment.

- Result Comparison: Compare the obtained results with the originally reported results.

- Discrepancy Documentation: Note any variations and attempt to identify their sources.

Validation Metrics: Bitwise agreement can sometimes be expected for computational reproducibility, though some numerical precision variations may be acceptable depending on the field standards [5].

Experimental Replicability Assessment Protocol

For experimental replicability, a different approach is required:

Objective: To determine whether consistent results can be obtained across studies aimed at answering the same scientific question using new data.

Materials and Reagents:

- Detailed experimental protocol from original study

- Necessary laboratory equipment and reagents

- Appropriate sample size calculations for statistical power

Procedure:

- Protocol Review: Carefully study the original methods and materials.

- Power Analysis: Conduct sample size calculations to ensure adequate statistical power.

- Independent Data Collection: Execute the experimental procedure without reliance on original data.

- Analysis Implementation: Apply similar analytical methods to the new dataset.

- Consistency Assessment: Evaluate consistency between original and new results using appropriate statistical measures.

Validation Metrics: Unlike reproducibility, replicability does not expect identical results but rather consistent results accounting for uncertainty. Assessment should consider both proximity (closeness of effect sizes) and uncertainty (variability in measures) [5].

Statistical Framework for Assessing Replicability

The National Academies report emphasizes that determining replication requires more than simply checking for repeated statistical significance [5]. A restrictive and unreliable approach would accept replication only when the results in both studies have attained "statistical significance" at a selected threshold [5]. Rather, in determining replication, it is important to consider the distributions of observations and to examine how similar these distributions are, including summary measures such as proportions, means, standard deviations (uncertainties), and additional metrics tailored to the subject matter [5].

The relationship between statistical measures in replication studies can be visualized as follows:

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Implementing reproducible and replicable research requires specific tools and practices. The following table details key solutions across the research workflow:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Reproducible and Replicable Science

| Solution Category | Specific Tools/Practices | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Management | Data management plans; File naming conventions; Metadata standards | Ensures data organization, preservation, and reusable structure | FAIR Principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) [3] |

| Computational Environment | Containerization (Docker); Virtual environments; Workflow systems | Preserves exact computational conditions for reproducibility | Version-controlled container specifications; Jupyter notebooks with kernel specifications |

| Code and Analysis | Version control (Git); Open source software; Scripted analyses | Documents analytical steps precisely for verification | Public code repositories (GitHub, GitLab); R/Python scripts with comprehensive commenting |

| Protocol Documentation | Electronic lab notebooks; Detailed methods sections; Protocol sharing platforms | Enables exact repetition of experimental procedures | Protocols.io; Detailed materials and methods in publications; Step-by-step protocols |

| Statistical Practices | Preregistration; Power analysis; Appropriate statistical methods | Reduces flexibility in analysis and selective reporting | Open Science Framework preregistration; Sample size calculations before data collection |

Implications for Scientific Fields

Discipline-Specific Considerations

The challenges and solutions for reproducibility and replicability vary across scientific domains. In biomedical research, concerns have focused on preclinical studies and clinical trials, with emphasis on randomized experiments with masking, proper sizing and power of experiments, and trial registration [2]. In psychology and social sciences, attention has centered on questionable research practices such as p-hacking and HARKing (hypothesizing after results are known) [6]. Computational fields have led the reproducible research movement, emphasizing sharing of data and code so results can be reproduced [2].

The emergence of new digital methods across disciplines, including topic modeling, network analysis, knowledge graphs, and various visualizations, has created new challenges for reproducibility and verifiability [7]. These methods create a need for thorough documentation and publication of different layers of digital research: digital and digitized collections, descriptive metadata, the software used for analysis and visualizations, and the various settings and configurations [7].

Institutional and Funding Agency Responses

Major research funders have implemented policies to address these challenges. The National Science Foundation (NSF) has reaffirmed its commitment to advancing reproducibility and replicability in science, encouraging proposals that address [8]:

- Advancing the science of reproducibility and replicability: Understanding current practices, ways to measure reproducibility and replicability, and reasons why studies may fail to replicate.

- Research infrastructure: Developing cyberinfrastructure tools that enable reproducible and replicable practices across scientific communities.

- Educational efforts: Enabling training to identify and encourage best practices for reproducibility and replicability.

Academic institutions, journals, conference organizers, funders of research, and policymakers all play roles in improving reproducibility and replicability, though this responsibility begins with researchers themselves, who should operate with "the highest standards of integrity, care, and methodological excellence" [1].

The distinction between reproducibility as computational verification and replicability as independent confirmation provides a crucial framework for assessing scientific validity. While the National Academies report does not necessarily agree with characterizations of a "crisis" in science, it unequivocally states that improvements are needed—including more transparency of code and data, more rigorous training in statistics and computational skills, and cultural shifts that reward reproducible and replicable practices [1].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, embracing these concepts requires both technical solutions and cultural changes. Making work reproducible offers additional benefits to authors themselves, including potentially greater impact through higher citation rates, facilitated collaboration, and more efficient peer review [4]. By implementing the protocols, tools, and frameworks outlined in this whitepaper, the scientific community can strengthen the foundation of reliable knowledge that informs future discovery and application.

The pursuit of scientific knowledge has always been inextricably linked to the tools and methodologies available for investigation. From Robert Boyle's 17th-century air pump to today's sophisticated computational models, the evolution of experimental science reveals a continuous thread: the quest for reliable, verifiable knowledge. This journey is framed by an ongoing dialogue between reproducibility (obtaining consistent results using the same data and methods) and replicability (obtaining consistent results across studies asking the same scientific question) [9]. Boyle's air pump, the expensive centerpiece of the new Royal Society of London, created a vacuum chamber for experimentation on air's nature and its effects [10]. His work, documented in New Experiments Physico-Mechanical (1660), insisted on the importance of sensory experience and witnessed experimentation, establishing a foundation for verification that would echo through centuries [10]. Today, we stand in the midst of a computational revolution equally transformative, where data-intensive research and artificial intelligence are reshaping the scientific landscape, presenting new challenges and opportunities for ensuring the robustness of scientific findings [11] [12] [13].

This article traces this historical arc, examining how the core principles of scientific demonstration and verification established in the 17th century have adapted to the rise of computation. We will explore how modern frameworks for reproducibility and replicability address the complexities of computational science, and provide a practical guide to the methodologies and tools that underpin rigorous, data-driven research today [2] [9].

Boyle’s Air Pump and the Foundation of Experimental Verification

In the mid-17th century, Robert Boyle, with the assistance of Robert Hooke, engineered the first air pump, establishing a new paradigm for experimental natural philosophy [10]. This device was not merely a tool but a platform for creating a new space for scientific inquiry—the vacuum chamber—which allowed for systematic experimentation on the properties and effects of air [10]. The air pump was the expensive centerpiece of the Royal Society of London, symbolizing a commitment to experimental evidence over pure reason [10].

Boyle’s methodology, as detailed in his 1660 work New Experiments Physico-Mechanical, Touching the Spring of the Air and Its Effects, was groundbreaking in its insistence on witnessing and sensory experience [10]. His writings provided painstakingly detailed accounts of his experiments, allowing those who were not present to understand and, in principle, verify his work [10]. This practice laid the groundwork for the modern concept of methodological transparency. However, the demonstrations were performed for a small audience of like-minded natural philosophers, and the ability to independently verify results was limited to those with access to similar sophisticated and costly apparatus [10].

Table: The Evolution of Scientific Demonstration from Boyle to the 19th Century

| Era | Primary Instrument | Audience | Purpose | Mode of Verification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid-17th Century (Boyle) | Air Pump / Vacuum Chamber | Small group of natural philosophers | Experimental natural philosophy | Witnessing, detailed written accounts |

| 19th Century | Improved Air Pumps (e.g., Franklin Educational Co.) | Large public audiences | Education and spectacle | Public demonstration of predictable results |

By the 19th century, the role of the air pump had evolved from a tool for primary research to an instrument for public education and spectacle [10]. At events like the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, manufacturers exhibited air pumps alongside other instruments like Leyden jars and magic lanterns for thrilling public displays [10]. Scientists like Humphry Davy and Michael Faraday cultivated their skills as entertainers, enchanting crowds while demonstrating scientific principles [10]. The air pump was now used to show predictable results, such as the silencing of a bell in a vacuum, for an audience's entertainment rather than to test new knowledge [10]. This shift marked a democratization of scientific witnessing, extending the sensory experience of science to broader audiences, yet the core principle of verification through demonstration remained central [10].

Defining the Framework: Reproducibility vs. Replicability

As science has grown in complexity and scope, the need for precise terminology to describe the verification of scientific findings has become paramount. The terms "reproducibility" and "replicability" are often used interchangeably in common parlance, but within the scientific community, particularly in the context of modern computational research, they have distinct and critical meanings. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine provide clear, authoritative definitions to resolve this confusion [9].

Reproducibility refers to obtaining consistent computational results using the same input data, computational steps, methods, code, and conditions of analysis. It is fundamentally about verifying that the same analytical process, applied to the same data, yields the same result. Reproducibility is a cornerstone of computational science, as it allows other researchers to verify the building blocks of a study before attempting to extend its findings [9].

Replicability refers to obtaining consistent results across studies that are aimed at answering the same scientific question, each of which has obtained its own data. Replication involves new data collection and the application of similar, but not identical, methods. A successful replication does not guarantee the original result was universally correct, nor does a single failure conclusively refute it. Instead, replication tests the robustness and generalizability of a scientific inference [9].

The confusion surrounding these terms is long-standing. As noted by the National Academies, different scientific disciplines and institutions have used these words in inconsistent or even contradictory ways [2]. For instance, in computer science, "reproducibility" often relates to the availability of data and code to regenerate results, while "replicability" might refer to a different team achieving the same results with their own artifacts [2]. The framework adopted here provides a consistent standard for discussion.

Table: Key Definitions in Scientific Verification

| Term | Core Question | Required Components | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reproducibility | Can I obtain the same results from the same data and code? | Original data, software, code, computational environment | Verification of the computational analysis |

| Replicability | Do I obtain consistent results when I ask the same question with new data? | New data, independent study, similar methods | Validation of the scientific claim's generality |

Failures in reproducibility often stem from a lack of transparency in reporting data, code, and computational workflow [9]. In contrast, failures in replicability can arise from both helpful and unhelpful sources. Helpful sources include inherent but uncharacterized uncertainties in the system being studied, which can lead to the discovery of new phenomena [9]. Unhelpful sources include shortcomings in study design, conduct, or communication, often driven by perverse incentives, sloppiness, or bias, which reduce the efficiency of scientific progress [9].

The Computational Revolution in Science

The latter part of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st have witnessed a profound shift in scientific practice, driven by the explosion of computational power and data availability. This "computational revolution" has transformed fields as diverse as astronomy, genetics, geoscience, and social science [2]. The democratization of data and computation has created entirely new ways to conduct research, enabling scientists to tackle problems of a scale and complexity that were previously impossible [2].

A key driver of this revolution is the shift to a data-centric research model. In the past, scientists in wet labs generated the data, and computational researchers played a supporting role in analysis [12]. Today, computational researchers are increasingly taking leadership roles, leveraging the vast amounts of publicly available data to drive discovery independently [12]. The challenge has moved from data generation to data analysis and interpretation [12]. This is exemplified by initiatives like the COBRE Center for Computational Biology of Human Disease at Brown University, which aims to help researchers convert massive datasets into useful information, a task that now confronts even those working primarily in wet labs or clinics [11].

Underpinning this revolution is the advent of accelerated computing. Unlike the mainframe and desktop eras that preceded it, accelerated computing relies on specialized hardware, such as graphical processing units (GPUs), to speed up the execution of specific tasks [13]. These GPUs, housed in massive data centers and used in parallel, provide the computational power required for complex artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and real-time data analytics [13]. The public introduction of models like ChatGPT was a striking demonstration of this power, but the implications extend to every sector, from drug discovery to climate modeling [13].

However, this new power is not without cost. The infrastructure of the computational revolution is energy-intensive, with large data centers consuming significant electricity [13]. This has prompted concerns about environmental impact and grid management. Yet, the relevant tradeoff is the social cost of not leveraging this technology—the delays in drug discoveries, the inferior climate models, and the foregone economic growth and productivity gains [13]. The policy challenge, therefore, is not to pause progress but to optimize AI for energy efficiency and to use AI itself to create a smarter, more efficient power grid [13].

Modern Computational Protocols and Reproducible Workflows

The rise of computational science has necessitated the development of rigorous protocols and platforms to ensure that research remains transparent, reproducible, and collaborative. Unlike the methods section of a traditional scientific paper, which is often insufficient to convey the complexity of a computational analysis, modern reproducible research requires the sharing of a complete digital compendium of data, code, and environment specifications [9].

Key Strategies for Integrating Computation and Experimentation

The integration of experimental data with computational methods is now a cornerstone of fields like structural biology and drug discovery. This integration can be achieved through several distinct strategies, each with its own advantages [14]:

- Independent Approach: Computational and experimental protocols are performed separately, and their results are compared post-hoc. This approach can reveal "unexpected" conformations but may struggle to sample rare biological events [14].

- Guided Simulation (Restrained) Approach: Experimental data are incorporated as external energy terms ("restraints") that directly guide the computational sampling of molecular conformations during the simulation. This efficiently limits the conformational space explored but requires deeper computational expertise to implement [14].

- Search and Select (Reweighting) Approach: A large pool of molecular conformations is first generated computationally. The experimental data are then used to filter and select the conformations that best match the data. This allows for easy integration of multiple data sources but requires that the initial pool contains the correct conformations [14].

- Guided Docking: Experimental data are used to define binding sites and assist in predicting the structure of biomolecular complexes, either during the sampling of binding poses or the scoring of their quality [14].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of these core strategies.

Essential Tools and Platforms for Reproducible Research

The practical implementation of these strategies relies on a robust toolkit. The following table details key computational reagents and platforms essential for modern, reproducible scientific research.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Computational Science

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| ColabFold [15] | Structure Prediction | Fast and accurate protein structure prediction using deep learning. | Predicting 3D structures of monomeric proteins and protein complexes from amino acid sequences. |

| Rosetta [15] | Software Suite | A comprehensive platform for macromolecular modeling, docking, and design. | Antibody structure prediction (RosettaAntibody) and docking to antigens (SnugDock). |

| HADDOCK [15] | Docking Server | Integrative modeling of biomolecular complexes guided by experimental data. | Determining the 3D structure of a protein-protein complex using NMR or cross-linking data. |

| AutoDock Suite [15] | Docking & Screening | Computational docking and virtual screening of ligand libraries against protein targets. | Identifying potential drug candidates by predicting how small molecules bind to a target protein. |

| ClusPro [15] | Docking Server | Performing rigid-body docking and clustering of protein-protein complexes. | Generating initial models of how two proteins might interact. |

| CryoDRGN [15] | Cryo-EM Analysis | A machine learning approach to reconstruct heterogeneous ensembles from cryo-EM data. | Uncovering continuous conformational changes and structural heterogeneity in macromolecular complexes. |

| protocols.io [16] | Protocol Platform | A platform for creating, sharing, and preserving updated research protocols with version control. | Sharing detailed, step-by-step computational workflows beyond abbreviated journal methods sections. |

| GPUs (Graphical Processing Units) [13] | Hardware | Specialized hardware that accelerates parallel computations, essential for training AI models. | Dramatically speeding up molecular dynamics simulations or deep learning-based structure prediction. |

Platforms like protocols.io directly address the reproducibility crisis by providing a structured environment for documenting methods. This facilitates collaboration and allows researchers to preserve and update their protocols with built-in version control, ensuring that the exact steps used in an experiment are known and reproducible [16]. As noted by a user from UCSF, this versioning "is especially powerful so that we can identify the exact version of a protocol used in an experiment, which increases reproducibility" [16].

The journey from Boyle's air pump to the modern computational revolution reveals a continuous evolution in the practice of science, yet a remarkable consistency in its core ideals. Boyle’s insistence on detailed documentation and witnessed experimentation finds its modern equivalent in the push for transparent data and code sharing [10] [9]. The 19th-century public demonstrations, which made scientific phenomena accessible to a broader audience, parallel today's efforts to democratize data and computational tools, moving research from exclusive, expensive endeavors to more collaborative and open practices [10] [11].

The computational revolution, powered by accelerated computing and AI, has introduced unprecedented capabilities for discovery [13]. However, it has also heightened the critical importance of the distinction between reproducibility and replicability [9]. Ensuring computational reproducibility—by sharing data, code, and workflows—is the necessary first step in building a reliable foundation for scientific knowledge. It is the modern implementation of Boyle's detailed record-keeping. Replicability, the process of confirming findings through independent studies and new data, remains the ultimate test of a scientific claim's validity and generalizability.

As we continue to navigate this data-centric world, the lessons of history are clear. The tools have changed, from brass pumps to GPU clusters, but the principles of rigor, transparency, and skepticism remain the bedrock of scientific progress. By embracing the frameworks, protocols, and tools designed to uphold these principles, researchers can ensure that the computational revolution delivers on its promise to advance human knowledge and address the complex challenges of our time.

The validity of scientific discovery rests upon a foundational principle: the ability to confirm results through independent verification. This process, however, is severely complicated by a pervasive issue known as terminology chaos, where key terms—most notably "reproducibility" and "replicability"—are defined and used in conflicting ways across different scientific disciplines. This inconsistency is not merely semantic; it directly impacts how research is conducted, evaluated, and trusted. Within the context of a broader thesis on scientific rigor, this terminology confusion creates significant obstacles for collaboration, peer review, and the assessment of research quality, ultimately muddying our understanding of what constitutes a verified scientific finding [1] [17].

The challenge is amplified when research spans traditional disciplinary boundaries, as is increasingly common. A computational biologist, a clinical trialist, and a meta-analyst may all use the words "reproducible" and "replicable" while intending fundamentally different concepts. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the origins and extent of this terminology chaos, presents a structured comparison of prevailing definitions, and offers concrete methodologies and tools to foster greater clarity and consistency in scientific communication.

The State of Terminology Chaos

The Core of the Confusion

At the heart of the terminology chaos is a fundamental reversal in how "reproducibility" and "replicability" are defined across scientific traditions. This is not a matter of minor variations but of directly opposing interpretations [17].

Claerbout Terminology (Computational Sciences): Pioneered by geophysicist Jon Claerbout, this tradition equates reproducibility with the exact recalculation of results using the same data and the same code. It is often seen as a minimal, almost mechanical standard. In contrast, replicability (or "reproduction") in this context refers to the more substantial achievement of reimplementing a method from its description to obtain consistent results with a new dataset [17].

ACM Terminology (Experimental & Metrology Sciences): The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) and international standards bodies like the International Vocabulary of Metrology define the terms almost inversely. Here, replicability refers to a different team obtaining consistent results using the same experimental setup and methods. Reproducibility represents the highest standard, where a different team, using a completely independent experimental setup (different methods, tools, etc.), confirms the original findings [17].

This divergence means that a computational scientist declaring a study "reproducible" and an analytical chemist describing an experiment's "reproducibility" are often referring to different levels of scientific validation, leading to potential miscommunication and misplaced confidence.

Quantitative Evidence of the Problem

A 2025 survey of 452 professors across universities in the USA and India highlights how terminology confusion and associated practices vary by national and disciplinary culture [18].

Table 1: Cultural and Disciplinary Gaps in Reproducibility and Transparency (Survey Findings)

| Aspect | Findings from the Survey |

|---|---|

| Familiarity with "Crisis" | Varying levels of familiarity with concerns about reproducibility, with significant gaps in attention aggravated by incentive misalignment and resource constraints. |

| Confidence in Literature | Researchers reported differing levels of confidence in work published within their own fields. |

| Institutional Factors | Key factors contributing to (non-)reproducibility included a lack of training, institutional barriers, and the availability of resources. |

| Recommended Solution | Solutions must be culturally-centered, where definitions of culture include both regional and domain-specific elements. |

The survey concluded that a one-size-fits-all approach is ineffective, and that enhancing scientific integrity requires solutions that are sensitive to both regional and disciplinary contexts [18].

A Structured Comparison of Conflicting Definitions

To navigate the terminology chaos, it is essential to have a clear, side-by-side comparison of the major definitional frameworks. The following table synthesizes the key terminologies discussed in the literature.

Table 2: Comparison of Major Definitional Frameworks for Reproducibility and Replicability

| Terminology Framework | Repeatability | Replicability | Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Claerbout (Computational) | (Not explicitly defined) | Writing new software based on the method description to obtain similar results on (potentially) new data. | Running the same software on the same input data to obtain the same results. [17] |

| ACM & Metrology Standards | Same team, same experimental setup. | Different team, same experimental setup. | Different team, different experimental setup. [17] |

| Goodman et al. Lexicon | (Focused on different aspects) | Results Reproducibility: Obtain the same results from an independent study with closely matched procedures. | Methods Reproducibility: Provide sufficient detail for procedures and data to be exactly repeated. [17] |

| Analytical Chemistry | Within-run precision (same operator, setup, short period). | (Often used interchangeably with reproducibility) | Between-run precision (different operators, laboratories, equipment, over time). [17] |

The Goodman Lexicon: A Potential Path Forward

In response to the confusion, Goodman, Fanelli, and Ioannidis proposed a new lexicon designed to sidestep the ambiguous common-language meanings of "reproduce" and "replicate." Their framework defines three distinct levels [17]:

- Methods Reproducibility: The provision of sufficient detail about procedures and data so that the same procedures could be exactly repeated.

- Results Reproducibility: The attainment of the same results from an independent study with procedures as closely matched to the original study as possible.

- Inferential Reproducibility: The drawing of qualitatively similar conclusions from either an independent replication of a study or a reanalysis of the original study.

This approach reframes the discussion around the specific aspect of the research process being evaluated, offering a more precise and less contentious vocabulary.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Terminology and Inconsistency

Protocol 1: Hierarchical Terminology Technique (HTT) for Terminology Mapping

The Hierarchical Terminology Technique (HTT) is a qualitative content analysis process developed to address terminology inconsistency in research fields. It structures a hierarchy of terms to expose the relationships between them, thereby improving clarity and consistency of use [19].

Objective: To systematically identify, analyze, and present the terminology of a research field to expose inconsistencies and structure a clear hierarchy of terms and their relationships.

Materials and Reagents:

- Primary Literature Corpus: A representative sample of research papers, review articles, and seminal texts from the field under study.

- Qualitative Data Analysis Software: Tools like NVivo or ATLAS.ti can facilitate coding, but the process can be managed with spreadsheets.

- HTT-Specific Codebook: A structured document for defining terms and recording their relationships (e.g., "is a type of," "is a part of," "is a property of").

Methodology:

- Terminology Identification: Systematically review the literature corpus to extract key terms and their definitions. Record the source and context of each definition.

- Terminology Analysis: a. Coding: Code each instance of a term's use and its associated definition. b. Comparison: Compare all definitions for a given term to identify conflicts, overlaps, and nuances. c. Relationship Mapping: For each term, determine its relationship to other terms in the field (e.g., Is "replicability" a broader category than "reproducibility," or are they distinct concepts?).

- Hierarchy Construction: Build a visual hierarchy (a tree diagram or a concept map) that positions terms according to their relationships. This exposes the scope of the research field and clarifies how terms should logically interact.

- Validation: Present the derived hierarchy to domain experts for feedback and refinement to ensure it accurately reflects the conceptual structure of the field.

Workflow Diagram: The following diagram illustrates the HTT methodology as a sequential workflow.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Assessment of Inconsistency in Meta-Analysis

In evidence synthesis, "inconsistency" refers to heterogeneity—the degree of variation in effect sizes across primary studies included in a meta-analysis. Traditional measures like I² and Cochran's Q have limitations, particularly with few studies or studies with very precise estimates. The following protocol outlines the use of two new indices based on Decision Thresholds (DTs) [20].

Objective: To quantitatively assess the inconsistency of effect sizes in a meta-analysis using Decision Thresholds (DTs) via the Decision Inconsistency (DI) and Across-Studies Inconsistency (ASI) indices.

Materials and Reagents:

- Dataset: A dataset containing the effect size and variance for each primary study in the meta-analysis.

- Statistical Software: R statistical environment with the

metaincpackage (https://metainc.med.up.pt/) or access to the companion web tool. - Defined Decision Thresholds (DTs): Pre-specified effect size values that demarcate boundaries between interpretation categories (e.g., trivial, small, moderate, and large effects).

Methodology:

- Model Fitting: Perform a Bayesian or frequentist random-effects meta-analysis on the dataset to obtain the posterior distributions (or best linear unbiased predictions) of the effect size for each primary study.

- Categorization by DT: For each sample from the posterior distribution of each study's effect size, assign it to an interpretation category based on the pre-defined DTs.

- Index Calculation: a. Decision Inconsistency (DI) Index: Calculate the percentage of studies for which at least one of their posterior effect size samples falls into a different interpretation category than the study's mean effect size. A DI ≥ 50% suggests important overall inconsistency. b. Across-Studies Inconsistency (ASI) Index: For each pair of studies, calculate the percentage of interpretation categories that are unique to one study or the other. Average this across all study pairs. An ASI ≥ 25% suggests important between-studies inconsistency.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Assess the impact of uncertainty in the DTs and the model on the DI and ASI values.

Workflow Diagram: The process for calculating and interpreting the DI and ASI indices is shown below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Terminology and Inconsistency Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Terminology and Inconsistency Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Literature Corpus | Serves as the primary source data for identifying terms, definitions, and their usage patterns. | A systematically gathered collection of PDFs from key journals and conference proceedings in the target field. |

| Qualitative Analysis Software | Facilitates the coding and organization of textual data, allowing for efficient analysis of terms and their relationships. | NVivo, ATLAS.ti, or even a structured spreadsheet (e.g., Excel or Google Sheets). |

| HTT Codebook | Provides a standardized structure for defining terms and mapping their hierarchical relationships, ensuring analytical consistency. | A document with fields for Term, Definition, Source, Related Terms, and Relationship Type. |

| R Statistical Environment | The computational engine for performing meta-analysis and calculating quantitative inconsistency indices. | R version 4.0.0 or higher. |

metainc R Package |

A specialized software tool for computing the Decision Inconsistency (DI) and Across-Studies Inconsistency (ASI) indices. | Available via the comprehensive R archive network (CRAN) or from the project's repository. |

| Web Tool for DI/ASI | Provides a user-friendly interface for researchers to compute the DI and ASI indices without requiring deep programming knowledge. | Accessible at https://metainc.med.up.pt/. |

| Decision Thresholds (DTs) | Act as pre-defined benchmarks to contextualize effect sizes, enabling the assessment of clinical or practical inconsistency beyond statistical heterogeneity. | e.g., Thresholds for "small," "moderate," and "large" effect sizes, determined a priori through expert consensus or literature review. |

Visualization and Reporting Standards

Principles for Effective Visual Communication

When creating diagrams and figures to illustrate terminology hierarchies or analytical results, adherence to established data visualization principles is crucial for effective communication [21].

- Use Position and Length over Area and Angle: Bar charts are generally superior to pie charts for comparing quantities, as the human brain is better at judging linear distances than areas or angles [21].

- Include Zero in Bar Plots: When using bar plots to represent quantities, the bar must start at zero to avoid visually distorting the differences between values [21].

- Do Not Distort Quantities: Ensure that visual cues like the area of circles (bubbles) are proportional to the quantities they represent. Using radius instead of area can misleadingly exaggerate differences [21].

- Show the Data: Instead of relying solely on summary statistics like dynamite plots, use plots that show the underlying data distribution, such as jittered points with alpha blending, boxplots, or histograms [21].

- Ease Comparisons: When comparing groups, use common axes for plots and align them to facilitate direct visual comparison [21].

Adherence to Color and Contrast Guidelines

All diagrams, including those generated with Graphviz, must comply with accessibility standards to be legible to all users, including those with color vision deficiencies. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) require a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 for normal text and 3:1 for large-scale text against the background [22]. The color palette specified for this document has been tested for effective contrast combinations.

Table 4: Color Palette and Application for Scientific Diagrams

| Color Name | HEX Code | Recommended Use | Contrast against White (~21:1) | Contrast against #F1F3F4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue | #4285F4 |

Primary nodes, positive flows | Pass | Pass |

| Red | #EA4335 |

Warning nodes, negative flows, termination points | Pass | Pass |

| Yellow | #FBBC05 |

Highlight nodes, cautionary elements | Pass (Best for large text) | Pass (Best for large text) |

| Green | #34A853 |

Success nodes, completion states, data inputs | Pass | Pass |

| Dark Gray | #5F6368 |

Text, borders, and lines | Pass | Pass |

| Off-White | #F1F3F4 |

Diagram background | N/A | N/A |

| White | #FFFFFF |

Node fill, text background | N/A | Pass (Text on it) |

| Near Black | #202124 |

Primary text color | Pass | Pass |

Scientific research has undergone a fundamental transformation from an activity mainly undertaken by individuals operating in a few locations to a complex global enterprise involving large teams and complex organizations. This evolution, characterized by three key driving forces—data abundance, computational power, and publication pressures—has introduced significant challenges to research reproducibility and replicability. Within the context of scientific research, reproducibility (obtaining consistent results using the original data and methods) and replicability (obtaining consistent results using new data or methodologies to verify findings) remain central to the development of reliable knowledge [2]. This paper examines how these driving forces interact within the specific context of drug development and biomedical research, where the stakes for reproducible and replicable findings are exceptionally high.

Quantitative Analysis of Evolving Research Practices

The scale and scope of scientific research have expanded dramatically. The following table summarizes key quantitative shifts that define the modern research environment.

Table 1: The Evolving Scale of Scientific Research

| Aspect of Research | Historical Context (17th Century) | Modern Context (2016) | Quantitative Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Output | Individual scientists communicating via letters | 2,295,000+ scientific/engineering articles published annually [2] | Massive increase in volume and specialization |

| Scientific Fields | A few emerging major disciplines | 230+ distinct fields and subfields [2] | High degree of specialization and interdisciplinarity |

| Data & Computation | Limited, manually analyzed data | Explosion of large datasets and widely available computing resources [2] | Shift to data-intensive and computationally driven science |

The Three Driving Forces

Data Abundance and Availability

The recent explosion in data availability has transformed research disciplines. Fields such as genetics, public health, and social science now routinely mine large databases and social media streams to identify patterns that were previously undetectable [2]. This data-rich environment enables powerful new forms of inquiry but also introduces challenges for reproducibility. The management, curation, and sharing of these massive datasets are non-trivial tasks, and without proper protocols, the ability to reproduce analyses diminishes significantly.

Computational Power and New Methodologies

The democratization of data and computation has created entirely new ways to conduct research. Large-scale computation allows researchers in fields from astronomy to drug discovery to run massive simulations of complex systems, offering insights into past events and predictions for future ones [2]. Earth scientists, for instance, use these simulations to model climate change, while biomedical researchers model protein folding and drug interactions. This reliance on complex computational workflows, often involving custom code, introduces a new vulnerability: minor mistakes in code can lead to serious errors in interpretation and reported results, a concern that launched the "reproducible research movement" in the 1990s [2].

Publication Pressures and Institutional Incentives

An increased pressure to publish new scientific discoveries in prestigious, high-impact journals is felt worldwide by researchers at all career stages [2]. This pressure is particularly acute for early-career researchers seeking academic tenure and grant funding. Traditional tenure decisions and grant competitions often give added weight to publications in prestigious journals, creating incentives for researchers to overstate the importance of their results and increasing the risk of bias—either conscious or unconscious—in data collection, analysis, and reporting [2]. These incentives can favor the publication of novel, positive results over negative or confirmatory results, which is detrimental to a balanced scientific discourse.

Experimental Protocols for Reproducible Research

To counter the threats to validity and robustness in this new environment, the scientific community, particularly in biomedicine, has developed rigorous experimental protocols. The following methodology outlines a standardized approach for a pre-clinical drug efficacy study designed for maximum reproducibility and replicability.

Detailed Experimental Methodology

1. Hypothesis and Pre-registration:

- Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of a novel compound (Drug X) on a specific disease model.

- Pre-registration: The complete experimental design, including primary and secondary endpoints, sample size justification, and statistical analysis plan, is registered on a public repository (e.g., Open Science Framework, ClinicalTrials.gov for clinical studies) before commencing the experiment.

2. Experimental Design:

- Type: Randomized, controlled experiment.

- Blinding (Masking): Both the researchers administering the treatment and assessing the outcomes, as well as the data analysts, are blinded to the group allocations (treatment vs. control) to prevent conscious or unconscious bias.

- Control Group: A vehicle control group is included to account for any effects of the administration method.

3. Sample Sizing and Power:

- Power Analysis: The sample size per group is determined using a statistical power analysis (e.g., 80% power, α = 0.05) based on a pre-specified, biologically relevant effect size derived from pilot data or previous literature. This ensures the experiment is adequately sized to detect a true effect.

4. Data Collection and Management:

- Standardized Protocols: All procedures (e.g., drug administration, sample collection) follow a detailed, written Standard Operating Procedure (SOP).

- Electronic Lab Notebook: All raw data, including any outliers or unexpected observations, is recorded in real-time using an electronic lab notebook with an immutable audit trail.

- Data Dictionary: A comprehensive data dictionary is created to define all variables, units, and measurement techniques.

5. Computational Analysis:

- Version Control: All analysis code (e.g., R, Python scripts) is managed using a version control system (e.g., Git).

- Containerization: The computational environment (operating system, software versions, library dependencies) is captured using a container platform (e.g., Docker, Singularity) to ensure the analysis can be executed identically in the future.

- Research Compendium: A complete digital compendium, containing the raw data, code, and environment specifications, is prepared for public sharing upon manuscript submission.

Visualizing the Research Workflow and Challenges

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz, illustrate the core concepts and workflows described in this paper.

Diagram 1: Interaction of driving forces and mitigation strategies in modern research.

Diagram 2: Workflow for a reproducible and replicable research study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Robust Research

The following table details key solutions, both methodological and technical, that are essential for conducting research that is resilient to the challenges posed by the modern research environment.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Reproducible Science

| Tool Category | Specific Solution / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Methodological Framework | Pre-registration of Studies | Mitigates publication bias and HARKing (Hypothesizing After the Results are Known) by specifying the research plan before data collection. |

| Methodological Framework | Blinding (Masking) & Randomization | Reduces conscious and unconscious bias during data collection and outcome assessment, ensuring the validity of results [2]. |

| Methodological Framework | Statistical Power Analysis | Determines the appropriate sample size before an experiment begins, reducing the likelihood of false negatives and underpowered studies. |

| Data & Code Management | Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELN) | Provides a secure, time-stamped, and immutable record of all raw data and experimental procedures. |

| Data & Code Management | Version Control Systems (e.g., Git) | Tracks all changes to analysis code, facilitating collaboration and allowing the recreation of any past analytical state. |

| Data & Code Management | Containerization (e.g., Docker) | Captures the complete computational environment (OS, software, libraries) to guarantee that analyses can be run identically in the future [2]. |

| Data & Code Management | Digital Research Compendium | A complete package of data, code, and documentation that allows other researchers to reproduce the reported results exactly. |

Reproducibility and replicability form the bedrock of the scientific method, serving as essential mechanisms for verifying research findings and ensuring the self-correcting nature of scientific progress. While these terms are often used interchangeably in casual discourse, understanding their precise definitions and distinct roles is critical for researchers, particularly in fields like drug development where scientific claims have direct implications for human health and therapeutic innovation.

According to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, reproducibility refers to "obtaining consistent results using the same data and code as the original study," often termed computational reproducibility [1]. In contrast, replicability means "obtaining consistent results across studies aimed at answering the same scientific question using new data or other new computational methods" [1]. This terminology, however, varies across disciplines, with some fields reversing these definitions [2] [17]. The Claerbout terminology, for instance, defines reproducing as running the same software on the same input data, while replicating involves writing new software based on methodological descriptions [17].

This semantic confusion underscores the importance of precise terminology when examining how these processes contribute to science's self-correcting nature. As this technical guide will demonstrate, both concepts play complementary but distinct roles in validating scientific claims, identifying errors, and building a reliable body of knowledge that can confidently inform drug development and other critical research domains.

The Theoretical Framework: How Science Self-Corrects

The fundamental principle underlying all scientific progress is that knowledge accumulates through continuous validation and refinement. The self-correcting nature of science depends on the community's ability to verify, challenge, and extend reported findings. In this framework, reproducibility and replicability serve as crucial checkpoints at different stages of knowledge validation.

The Epistemological Roles

Philosophically, science advances through a process of conjecture and refutation, where reproducibility and replicability provide the mechanisms for critical assessment [23]. Direct replications primarily serve to assess the reliability of an experiment by evaluating its precision and the presence of random error, while conceptual replications assess the validity of an experiment by evaluating its accuracy and systematic uncertainties [23]. This distinction is crucial for understanding how different types of replication efforts contribute to scientific progress.

When a result proves non-reproducible, it typically indicates issues with the original analysis, code, or data handling. When a result proves non-replicable, it may indicate limitations in the original methods, undisclosed analytical flexibility, context-dependent effects, or in rare cases, fundamental flaws in the underlying theory [5]. This process of identifying and investigating discrepancies drives scientific refinement, as noted by the National Academies report: "The goal of science is not to compare or replicate [studies], but to understand the overall effect of a group of studies and the body of knowledge that emerges from them" [1].

The Knowledge Building Cycle

The relationship between reproducibility, replicability, and scientific progress can be visualized as an iterative cycle where each stage provides distinct forms of validation:

Figure 1: The Self-Correcting Scientific Process - This diagram illustrates how reproducibility and replicability interact in an iterative cycle of knowledge validation and refinement.

Quantitative Evidence: Assessing the State of Reproducibility and Replicability

Empirical assessments of reproducibility and replicability rates across scientific disciplines provide critical insight into the health of the research ecosystem. Large-scale replication efforts and researcher surveys reveal substantial challenges across multiple fields.

Large-Scale Replication Projects

Several systematic efforts to assess replicability have been conducted over the past decade, with sobering results:

Table 1: Replication Rates Across Scientific Disciplines

| Field | Replication Rate | Study/Project | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychology | 36-39% | Open Science Collaboration (2015) [24] | Only 36% of replications had statistically significant results; 39% subjectively successful [5] [24] |

| Economics | 61% | Camerer et al. (2018) [5] | 61% of replications successful, but effect sizes averaged 66% of original [5] |

| Cancer Biology | 11-25% | Begley & Ellis (2012) [5] | Amgen and Bayer Healthcare reported 11-25% replication rates in preclinical studies [5] [24] |

| Social Sciences | 62% | Camerer et al. (2018) [5] | Average replication rate of 62% across social science experiments [5] |

Researcher Perspectives and Practices

A 2025 survey of 452 professors from universities across the USA and India provides insight into current researcher perspectives and practices regarding reproducibility and replicability [6]:

Table 2: Researcher Perspectives on Reproducibility and Replicability (2025 Survey)

| Survey Category | USA Researchers | India Researchers | Overall Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Familiarity with "reproducibility crisis" | High in social sciences | Variable across disciplines | Significant disciplinary and national gaps in awareness [6] |

| Confidence in field's published literature | Mixed | Mixed | Varies by discipline and methodology [6] |

| Institutional support for reproducible practices | Limited | Resource-constrained | Misaligned incentives and resource limitations major barriers [6] |

| Data/sharing practices | Increasing but not mainstream | Emerging | Transparency practices not yet widespread [6] |

This survey highlights how issues of scientific integrity are deeply social and contextual, with significant variations across disciplines and national research cultures [6]. The findings underscore the need for culturally-centered solutions that address both regional and domain-specific factors.

Methodological Protocols: Ensuring Reproducibility and Replicability

Implementing robust methodological practices is essential for enhancing reproducibility and replicability. The following protocols provide frameworks for different aspects of the research lifecycle.

Computational Reproducibility Protocol

For research involving computational analysis, the following workflow ensures reproducibility:

Figure 2: Computational Reproducibility Workflow - This protocol outlines key steps and practices for ensuring computational analyses can be reproduced.

The reproducible research method requires that "scientific results should be documented in such a way that their deduction is fully transparent" [25]. This requires detailed description of methods, making full datasets and code accessible, and designing workflows as sequences of smaller, automated steps [25]. Tools like R Markdown, Jupyter notebooks, and the Open Science Framework facilitate this documentation [25].

Direct vs. Conceptual Replication Protocols

Different replication designs serve distinct epistemic functions in assessing reliability and validity:

Table 3: Replication Typologies and Methodological Requirements

| Replication Type | Primary Function | Methodological Requirements | Assessment Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Replication | Assess reliability/precision by evaluating random error [23] | Same methods, similar equipment, identical procedures as original study [24] [23] | Proximity of results within margins of statistical uncertainty [5] |

| Systematic Replication | Evaluate robustness across minor variations | Intentional changes to specific parameters while maintaining core methods [24] | Consistency of directional effects and significance patterns |

| Conceptual Replication | Assess validity/accuracy by evaluating systematic error [23] | Different procedures testing same underlying hypothesis or construct [24] [23] | Convergence of conclusions despite methodological differences |

Determining replication success requires careful consideration of multiple criteria beyond simple statistical significance. The National Academies report emphasizes that "a restrictive and unreliable approach would accept replication only when the results in both studies have attained 'statistical significance'" [5]. Instead, researchers should "consider the distributions of observations and to examine how similar these distributions are," including summary measures and subject-matter specific metrics [5].

Conducting reproducible and replicable research requires both conceptual understanding and practical tools. The following toolkit outlines essential resources and their functions in supporting robust science.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Reproducible Science

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Research Process | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Version Control Systems | Git, SVN, Mercurial | Track changes to code, manuscripts, and documentation | Create reproducible workflows; enable collaboration; maintain history |

| Computational Environment Tools | Docker, Singularity, Conda | Containerize computational environments | Ensure consistency across systems; capture dependency versions |

| Data & Code Repositories | OSF, Zenodo, Dataverse | Preserve and share research artifacts | Assign persistent identifiers; use standard formats; provide metadata |

| Electronic Lab Notebooks | Benchling, RSpace, eLabJournal | Document protocols and experimental details | Implement structured templates; ensure integration with other systems |

| Workflow Management Systems | Nextflow, Snakemake, Galaxy | Automate multi-step computational analyses | Create reproducible, scalable, and portable data analysis pipelines |

| Statistical Analysis Tools | R, Python, Julia | Implement transparent statistical analyses | Use scripted analyses; avoid point-and-click; document random seeds |

These tools collectively address what Goodman et al. (2016) term "methods reproducibility" (providing sufficient detail about procedures and data), "results reproducibility" (obtaining the same results from an independent study), and "inferential reproducibility" (drawing the same conclusions from either replication or reanalysis) [17].

Case Study: The Hubble Constant Controversy

The ongoing controversy surrounding measurements of the Hubble constant (H₀) provides an instructive case study of how reproducibility and replicability function in a mature scientific field with strong methodological standards.

Astronomers currently face a significant discrepancy in measurements of the Hubble constant, which quantifies the rate of expansion of the universe. Three major experimental approaches have yielded inconsistent results:

- Cosmic Distance Ladder measurements using Cepheid variable stars and supernovae

- Cosmic Microwave Background measurements from the Planck satellite

- Gravitational Lensing measurements using time-delay distances

This discordance represents a localized replicability failure in a field with normally strong replicability standards [23]. In response, astronomers have employed both direct replications (assessing reliability through precision) and conceptual replications (assessing validity through accuracy) to identify the source of the discrepancy [23].

The Hubble constant case illustrates how the epistemic functions of replication map onto different types of experimental error. Direct replications serve to assess statistical uncertainty/random error, while conceptual replications serve to assess systematic uncertainty [23]. This case demonstrates how a well-functioning scientific community responds to replicability challenges through methodological refinement and continued investigation.

Reproducibility and replicability are not merely abstract scientific ideals but practical necessities for the self-correcting nature of science. They function as complementary processes that together validate scientific claims, identify errors and biases, and build a reliable body of knowledge. As the National Academies report emphasizes, while there may not be a full-blown "crisis" in science, there is certainly no time for complacency [1].

For researchers in drug development and other applied sciences, embracing reproducibility and replicability is particularly crucial. The transition from basic research to clinical applications depends on the reliability of preliminary findings. Enhancing these practices requires addressing not only methodological factors but also the incentive structures and cultural norms that shape scientific behavior [1] [6].

Ultimately, the collective responsibility for improving reproducibility and replicability lies with all stakeholders in the scientific ecosystem—researchers, institutions, funders, journals, and publishers. By working to align incentives with best practices, supporting appropriate training and education, and developing more robust methodological standards, the scientific community can strengthen its self-correcting mechanisms and accelerate the accumulation of reliable knowledge.

Implementing Rigor: Practical Strategies for Reproducible and Replicable Research

The evolving practices of modern science, characterized by an explosion in data volume and computational analysis, have brought issues of reproducibility and replicability to the forefront of scientific discourse [2]. In this context, a Research Compendium emerges as a practical and powerful solution for making computational research reproducible. A research compendium is a collection of all digital parts of a research project, created in such a way that reproducing all results is straightforward [26].

Understanding the distinction between reproducibility and replicability is crucial, though terminology varies across disciplines [2]. For this guide, we adopt the following operational definitions:

Reproducibility refers to reanalyzing the existing data using the same research methods and yielding the same results, demonstrating that the original analysis was conducted fairly and correctly [27]. This involves using the original author's digital artifacts (data and code) to regenerate the results [2].

Replicability (sometimes called repeatability) refers to reconducting the entire research process using the same methods but new data, and still yielding the same results, demonstrating that the original results are reliable [27]. This involves independent researchers collecting new data to arrive at the same scientific findings [2].

The research compendium primarily addresses reproducibility by providing all digital components needed to verify and build upon existing analyses. This is particularly critical in fields like drug development, where computational analyses inform costly clinical decisions.

The Anatomy of a Research Compendium

Core Components and Structure

A research compendium combines all elements of a project, allowing others to reproduce your work, and should be the final product of your research project [26]. Three principles guide its construction [26]:

- Conventional Organization: Files should be organized in a conventional folder structure

- Clear Separation: Data, methods, and output should be clearly separated

- Environment Specification: The computational environment should be specified

Table 1: Core Components of a Research Compendium

| Component Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Read-only | Raw data and metadata that should not be modified | data_raw/, datapackage.json, CITATION file |

| Human-generated | Code, documentation, and manuscripts created by researchers | Analysis scripts (clean_data.R), paper (paper.Rmd), README.md |

| Project-generated | Outputs created by executing the code | Clean data (data_clean/), figures (figures/), other results |

Basic vs. Executable Compendia

The implementation of a research compendium can range from basic to fully executable:

Basic Compendium follows the three core principles with a simple structure [26]:

Executable Compendium contains all digital parts plus complete information on how to obtain results [26]:

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and workflow between these components:

Creating a Research Compendium: Methodologies and Protocols

Step-by-Step Creation Protocol

Creating a research compendium involves a systematic approach that can be integrated throughout the research lifecycle [26]:

- Design Phase: Plan folder structure early in the research process

- Implementation Phase: Create directory structure (main directory and subdirectories)

- Development Phase: Add all files needed for reproduction

- Validation Phase: Have a peer check the compendium for functionality

- Publication Phase: Publish the compendium on appropriate platforms

For drug development professionals, this process ensures that computational analyses supporting regulatory decisions can be independently verified.

Computational Environment Specification

A critical challenge in computational reproducibility is reconstructing the software environment. The R package rang provides a solution by generating declarative descriptions to reconstruct computational environments at specific time points [28]. The reconstruction process addresses four key components [28]:

- Component A: Operating system

- Component B: System components (e.g., libxml2)

- Component C: Exact R version

- Component D: Specific versions of installed R packages

The basic protocol for using rang involves two main functions [28]:

This approach has been tested for R code as old as 2001, significantly extending the reproducibility horizon compared to solutions dependent on limited-time archival services [28].

Implementation Toolkit for Researchers

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Creating Reproducible Research Compendia

| Tool/Category | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Version Control | Track changes to code and documentation | Git, GitHub, GitLab |

| Environment Management | Specify and recreate software environments | Docker, Rocker images, rang package [28] |

| Automation Tools | Automate analysis workflows | Make, Snakemake, targets (R package) |

| Documentation | Provide human-readable guidance | README.md, LICENSE, CITATION files |

| Data Management | Organize and describe data | datapackage.json, codebook.Rmd |

| Publication Platforms | Share and archive compendia | Zenodo, OSF, GitHub (with Binder integration) |

Publishing and Review Protocols

Research compendia can be published through several channels [26]:

- Versioning platforms (GitHub, GitLab) often with Binder integration for executable environments

- Research archives (Zenodo, Open Science Framework) for long-term preservation

- Supplementary materials of journal publications

The AGILE conference exemplifies how reproducibility reviews can be integrated into scientific evaluation [29]. Their protocol includes:

- Reviewer Assignment through shared spreadsheets

- Package Access via shared cloud folders

- Author Communication using standardized templates

- Scope Limitation to prevent excessive reviewer burden

- Report Publication on platforms like OSF or ResearchEquals

This structured approach ensures that reproducibility assessments are consistent and comprehensive.

Impact on Scientific Practice

Applications Across Research Contexts

Research compendia serve multiple functions in the scientific ecosystem [26]:

- Peer Review Enhancement: Enable thorough verification of analyses

- Research Understanding: Provide complete context for interpreting results

- Teaching Resources: Serve as exemplars for computational methods

- Reproducibility Studies: Support formal reproducibility assessments

In drug development, where computational analyses increasingly inform regulatory decisions, research compendia provide traceability and verification mechanisms that enhance decision quality and patient safety.

Quantitative Assessment of Adoption

The 2025 AGILE conference reproducibility review provides insights into current adoption practices [29]. Analysis of 23 full papers revealed:

Table 3: Reproducibility Section Implementation in AGILE 2025 Submissions

| Submission Type | Total Submissions | With Data & Software Availability Section | Implementation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Paper | 23 | 22 | 95.7% |

Word frequency analysis of these submissions highlighted key methodological focus areas, with "data" (884 occurrences), "model" (679), "spatial" (571), and "analysis" (400) appearing most frequently across all papers [29].

Visualizing the Research Compendium Ecosystem

The following diagram maps the relationships between compendium components, tools, and outcomes in the reproducible research ecosystem: