Full-Length vs. Partial 16S rRNA Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide for Microbial Research and Diagnostics

This article provides a definitive comparison between full-length and partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing for researchers and drug development professionals.

Full-Length vs. Partial 16S rRNA Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide for Microbial Research and Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a definitive comparison between full-length and partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of the 16S rRNA gene and its variable regions, detailing how third-generation long-read sequencing technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore are overcoming the limitations of short-read platforms. The content delivers actionable methodological protocols, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization points such as primer selection and PCR bias, and presents rigorous validation data from mock communities and human microbiome samples. Synthesizing current evidence, this guide concludes that full-length sequencing offers superior species-level resolution, which is crucial for discovering biomarkers and developing targeted therapies, while also providing pragmatic advice on when partial sequencing remains a viable option.

The 16S rRNA Gene: Unlocking Taxonomic Resolution from Variable Regions to Full-Length Sequences

The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene is a foundational molecular marker in microbiology, serving critical roles in phylogenetic studies, bacterial identification, and microbiome analysis. This gene, approximately 1,500 base pairs (bp) in length, possesses a characteristic structure comprising nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) flanked by conserved sequences [1]. The conserved regions enable the design of universal PCR primers that can amplify this gene from a vast range of bacteria, while the hypervariable regions accumulate mutations at different rates, providing signature sequences that can differentiate taxonomic groups from the domain level down to the species and strain level [2] [3]. The advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies has fundamentally transformed how researchers utilize this gene. This guide objectively compares the performance of two primary sequencing approaches: full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing using third-generation long-read platforms (e.g., PacBio) and partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing targeting specific hypervariable regions with second-generation short-read platforms (e.g., Illumina). The central thesis is that while targeting sub-regions was a necessary historical compromise due to technological limitations, full-length sequencing delivers superior taxonomic resolution, albeit with different cost and logistical considerations [4].

The 16S rRNA gene is a component of the 30S small subunit of the prokaryotic ribosome [3]. Its structure is key to its dual function in protein synthesis and its utility as a molecular clock. The gene's architecture consists of:

- Conserved Regions: These stretches of sequence are highly similar across most bacterial domains. They primarily serve structural and functional roles within the ribosome, such as defining ribosomal protein positions and aiding in the initiation of protein synthesis [2]. From a practical standpoint, these conserved segments provide reliable binding sites for "universal" PCR primers, allowing for the amplification of the 16S gene from a wide spectrum of bacterial species without prior knowledge of the specific sequences present [1].

- Hypervariable Regions (V1-V9): Interspersed between the conserved areas are nine hypervariable regions (V1 through V9), which range from approximately 30 to 100 base pairs in length [3]. These regions demonstrate considerable sequence diversity among different bacterial species due to a higher tolerance for evolutionary change. The variable regions contain species-specific signature sequences that are the primary basis for bacterial identification and phylogenetic discrimination [5] [1]. It is crucial to note that the degree of conservation and the power to discriminate between taxa vary significantly across the different hypervariable regions [4].

The following diagram illustrates the relative positions of these regions within the linear sequence of the 16S rRNA gene.

Comparative Analysis of Hypervariable Regions

Not all hypervariable regions are equally effective for differentiating bacterial taxa. The discriminatory power of each region varies considerably, making the choice of target region a critical decision in experimental design [5] [4].

Diagnostic Resolution of Individual Hypervariable Regions

A systematic analysis of hypervariable regions in 110 bacterial species, including common pathogens and CDC-defined select agents, revealed distinct strengths and weaknesses for each region [5]. The table below summarizes the key findings regarding the suitability of individual variable regions for differentiating specific bacterial groups.

Table 1: Suitability of 16S rRNA Hypervariable Regions for Differentiating Bacterial Taxa

| Hypervariable Region | Recommended Taxonomic Level | Notable Strengths and Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| V1 | Genus/Species | Best differentiation of Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species [5]. |

| V2 & V3 | Genus | Suitable for distinguishing most bacteria to the genus level, except for closely related Enterobacteriaceae. V2 best for Mycobacterium; V3 best for Haemophilus [5]. |

| V6 | Species | A short region (∼58 bp) that could distinguish among most bacterial species except Enterobacteriaceae. Noteworthy for differentiating all CDC-defined select agents [5]. |

| V4, V5, V7, V8 | Higher Levels (e.g., Phylum) | Less useful targets for genus or species-specific probes; more appropriate for broader phylogenetic analyses [5] [3]. |

Performance of Region Combinations in Metagenomic Studies

In practice, many studies sequence multiple adjacent variable regions to increase the amount of informative data. However, in silico experiments demonstrate that even combinations of regions cannot match the taxonomic resolution provided by the full-length gene [4]. The following table compares common region combinations used with short-read platforms against full-length sequencing.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Common 16S rRNA Amplicon Strategies

| Targeted Region(s) | Approximate Length | Species-Level Classification Efficiency | Taxonomic Biases and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| V4 | ~250 bp | Lowest performance; 56% of in silico amplicons failed to be confidently matched to their correct species [4]. | Provides adequate phylum-level resolution but struggles with species-level discrimination [4]. |

| V1-V3 | ~510 bp | A reasonable approximation of 16S diversity; performance varies by taxon [6] [4]. | Poor at classifying Proteobacteria; good for Escherichia/Shigella [4]. |

| V3-V5 | ~428 bp | Moderate performance [4]. | Poor at classifying Actinobacteria; good for Klebsiella [4]. |

| V6-V9 | ~548 bp | Moderate performance [4]. | The best sub-region for classifying Clostridium and Staphylococcus [4]. |

| Full-Length (V1-V9) | ~1500 bp | Highest performance; nearly all sequences correctly classified at the species level [4]. | Consistently provides the best results across diverse taxa with minimal bias [4] [7]. |

Experimental Comparisons: Full-Length vs. Partial Gene Sequencing

Direct experimental comparisons between full-length and partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing methodologies highlight critical differences in their outputs and applications.

Experimental Protocol for Method Comparison

A standard protocol for a head-to-head performance comparison, as used in recent studies, involves [7]:

- Sample Collection: DNA is extracted from relevant samples (e.g., human fecal samples, saliva, subgingival plaque, or environmental samples).

- Parallel Amplification:

- Partial Gene Approach: Amplify a specific hypervariable region (e.g., V3-V4) using primers such as 347F/803R [7] and sequence the amplicons on an Illumina MiSeq platform.

- Full-Length Approach: Amplify the entire V1-V9 region using universal primers (e.g., 27F/1492R) [8] [7] and sequence the amplicons on a long-read platform like PacBio Sequel II or Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) MinION.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process raw reads from both platforms using standardized pipelines (e.g., QIIME 2, DADA2) for quality filtering, denoising, and Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) generation. Taxonomic assignment is performed against reference databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes).

- Comparison Metrics: Evaluate outcomes based on the percentage of reads assigned to genus and species levels, alpha and beta diversity measures, and accuracy in classifying taxa from mock communities of known composition.

Key Comparative Data

Recent studies yield the following performance data:

- Taxonomic Resolution: A 2024 study on human microbiome samples found that while both Illumina (V3-V4) and PacBio (V1-V9) assigned a similar percentage of reads to the genus level (~95%), PacBio assigned a significantly higher proportion of reads to the species level (74.14% vs. 55.23%) [7]. This confirms that full-length sequencing provides a substantial improvement in species-level classification.

- Community Composition: Despite differences in resolution, both platforms generally recapitulate similar broad-scale community profiles, with samples clustering by body site (niche) rather than by sequencing platform [7].

- Quantitative Accuracy: Both methods demonstrate high accuracy for quantifying most microbial genera. However, specific biases can occur; for instance, the genus Streptococcus has been observed at a higher relative abundance in PacBio data compared to Illumina data in oral samples, though such differences are not always statistically significant after multiple-testing corrections [7].

- Utility in Clinical Diagnostics: A 2024 clinical study found that 16S NGS (targeting the V3 region) demonstrated enhanced detection in 40% of confirmed infection cases compared to culture methods, and was particularly useful for identifying pathogens in patients who had already received antibiotic therapy [9].

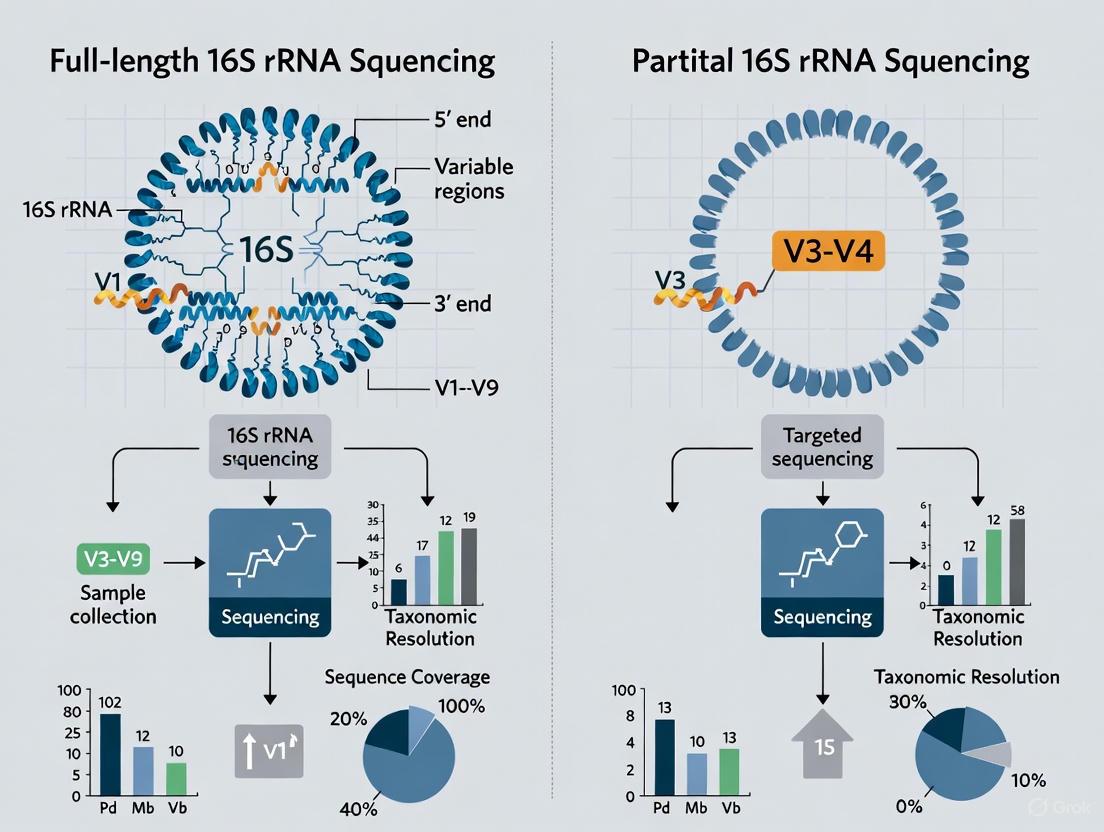

The relationship between sequencing strategy and taxonomic outcomes is summarized below.

Successful 16S rRNA gene sequencing, whether full-length or partial, relies on a set of key reagents and bioinformatic resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

| Category | Item | Specific Example(s) | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Universal PCR Primers | 27F (AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG) & 1492R (CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT) for full-length [8] [7]. 347F/803R or other pairs for V3-V4 [7]. | Amplify target regions of the 16S rRNA gene from complex DNA mixtures. |

| DNA Polymerase for Amplicon Generation | LongAmp Taq Master Mix [8]. | Robust amplification of target regions, especially for full-length amplicons. | |

| Library Prep Kit | SQK-16S Barcoding Kit (ONT) [8]. SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit (PacBio) [6]. | Prepare amplified DNA for sequencing on a specific platform. | |

| Sequencing Platforms | Long-Read Sequencer | PacBio Sequel II System [6] [7], Oxford Nanopore MinION [8]. | Generates long reads (>1,000 bp) necessary for full-length 16S sequencing. |

| Short-Read Sequencer | Illumina MiSeq [7] [9]. | Generates high-throughput, short reads (≤600 bp) for partial gene sequencing. | |

| Bioinformatic Resources | Reference Databases | SILVA [1], Greengenes [4] [1], EzBioCloud [1]. | Curated collections of 16S rRNA sequences for taxonomic assignment. |

| Analysis Pipelines | DADA2 [4] [7], QIIME 2 [3], mothur [3]. | Process raw sequencing data, perform quality control, and conduct diversity analyses. |

The structure of the 16S rRNA gene, with its mosaic of conserved and hypervariable regions, makes it an powerful tool for microbial ecology and clinical diagnostics. The choice between full-length and partial gene sequencing is a fundamental one, with a clear trade-off between taxonomic resolution and practical considerations like cost and throughput. Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing via long-read technologies provides the highest possible taxonomic resolution, enabling reliable species-level classification and the detection of intragenomic copy variants, which can be critical for distinguishing closely related strains [4] [7]. In contrast, partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing with short-read platforms remains a robust and cost-effective method for characterizing microbial communities at the genus level and for studying broad ecological patterns [7] [9]. The decision must be guided by the specific research question, with full-length sequencing being indispensable for studies requiring species- or strain-level discrimination, and partial sequencing being sufficient for broader compositional surveys. As long-read technologies continue to decline in cost and improve in accuracy, they are poised to become the new gold standard for high-resolution amplicon-based microbial community analysis.

For decades, the sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene has been the cornerstone of microbial ecology and clinical bacteriology, enabling the identification and phylogenetic analysis of bacterial communities. The ~1,550 bp gene comprises nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) that provide the sequence diversity necessary for taxonomic discrimination, interspersed with conserved regions. While the value of the full-length 16S rRNA gene for achieving maximum taxonomic resolution has long been recognized, the majority of high-throughput microbiome studies conducted since the advent of next-generation sequencing have, by necessity, focused on analyzing only one or a few of these sub-regions. This article explores the technological constraints—specifically those imposed by the dominant short-read sequencing platforms—that forced this widespread methodological compromise and evaluates the performance implications when compared to emerging full-length sequencing technologies.

The Technological Imperative: How Platform Capabilities Shaped Methodology

The historical focus on 16S sub-regions represents a direct adaptation to the technical limitations of second-generation sequencing platforms, most notably those from Illumina.

The Short-Read Sequencing Constraint: Illumina platforms, which became the workhorses of high-throughput sequencing, typically produce read lengths of 300-600 bp (2x150 bp or 2x300 bp paired-end). This physical limitation made it impossible to sequence the entire ~1,500 bp 16S rRNA gene in a single read [4] [7]. Consequently, researchers were forced to select specific variable regions that could be amplified and sequenced within these length constraints.

The Primer Selection Compromise: This technological limitation shifted the experimental design question from "What provides the best taxonomic resolution?" to "Which sub-region provides the best resolution within our technical constraints?" Common choices included [6] [4]:

- V4: Often selected for its relatively short length and good coverage across many bacterial phyla.

- V3-V4: A popular combination providing more taxonomic information than V4 alone.

- V1-V3: A longer region that offers broader diversity coverage but may require more sequencing resources.

The selection of these sub-regions involved careful trade-offs between phylogenetic resolution, cost-effectiveness, and the specific bacterial taxa being targeted [6]. This compromise was widely accepted because short-read platforms offered tremendous advantages in throughput, cost, and accessibility compared to first-generation Sanger sequencing, which could sequence the full gene but at a scale insufficient for complex microbiome studies.

Performance Implications: The Taxonomic Cost of Compromise

The decision to target sub-regions of the 16S rRNA gene came with significant limitations in taxonomic resolution, particularly at the species level. Comparative studies have consistently demonstrated that full-length 16S sequencing provides superior discriminatory power.

Table 1: Comparative Taxonomic Resolution of 16S Sub-Regions vs. Full-Length

| Target Region | Species-Level Classification Rate | Remarks on Taxonomic Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Full-Length (V1-V9) | Nearly 100% [4] | Provides the most accurate and comprehensive taxonomic resolution across all phyla |

| V1-V3 | Moderate to high [6] [4] | Resolution comparable to full-length for some applications; poor for Proteobacteria [4] |

| V3-V5 | Moderate [4] | Performs poorly for Actinobacteria [4] |

| V4 | Low (44% success rate) [4] | 56% of amplicons failed to confidently match their sequence of origin at species level [4] |

| V6-V9 | Varies by taxon [4] | Best sub-region for Clostridium and Staphylococcus [4] |

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Short-Read vs. Long-Read 16S Sequencing

| Parameter | Short-Read (Illumina) | Long-Read (PacBio) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Target | V3-V4 or other sub-regions [7] | Full-length V1-V9 [7] |

| Read Length | ≤300 bp (2x250-300 bp paired-end) [10] [7] | ~1,500 bp (entire gene) [7] |

| Species-Level Assignment | 55.23% of reads [7] | 74.14% of reads [7] |

| Genus-Level Assignment | 94.79% of reads [7] | 95.06% of reads [7] |

| Limitations | Limited resolution for closely related species; regional bias [4] [7] | Higher initial cost per read; potential indel errors in homopolymers [4] |

The fundamental issue with sub-region sequencing is that discriminating polymorphisms between closely related species may be restricted to specific variable regions not captured in the sequenced fragment [4]. For example, while the V1-V3 region offers resolution comparable to full-length sequencing for some applications [6], the V4 region—one of the most commonly targeted regions—fails to provide confident species-level classification for more than half of all sequences [4].

Experimental Evidence: Methodologies for Comparison

Recent studies have directly compared the performance of short-read sub-region sequencing versus long-read full-length 16S sequencing using standardized experimental approaches.

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: In a typical comparative study, samples are collected from various habitats (e.g., human saliva, subgingival plaque, and feces), and DNA is extracted using commercial kits such as the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit [6]. The integrity and concentration of extracted DNA are verified using fluorometry and spectrophotometry [10].

PCR Amplification and Sequencing: The same DNA extracts are subjected to two parallel amplification and sequencing workflows [7]:

- Short-read approach: Amplification of the V3-V4 regions (approximately 460 bp) using primers such as 341F/806R, followed by sequencing on Illumina MiSeq.

- Long-read approach: Amplification of the full-length 16S gene (V1-V9, approximately 1,500 bp) using primers 27F/1492R, followed by sequencing on PacBio Sequel II system.

Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequences are processed using standardized pipelines (e.g., DADA2 for Amplicon Sequence Variants) and classified against reference databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes) to determine taxonomic assignments at various phylogenetic levels [4] [7].

Experimental Workflow for Comparing 16S Sequencing Approaches

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for 16S rRNA Sequencing

| Item | Function | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Primers | Amplify 16S rRNA gene from diverse bacteria | 27F (AGRGTTTGATYNTGGCTCAG) and 1492R (TASGGHTACCTTGTTASGACTT) for full-length [6] |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolate high-quality microbial DNA from complex samples | PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit [6]; Quick-DNA HMW MagBead Kit [10] |

| Short-Read Sequencer | High-throughput sequencing of sub-regions | Illumina MiSeq (2×300 bp) [7] |

| Long-Read Sequencer | Full-length 16S sequencing | PacBio Sequel II (CCS mode) [6] [7]; Oxford Nanopore MinION [10] |

| Reference Database | Taxonomic classification of sequences | SILVA, Greengenes, RDP [4] |

The Paradigm Shift: Third-Generation Sequencing and the Return to Full-Length Analysis

The development of third-generation sequencing platforms has fundamentally altered the calculus of 16S sequencing by removing the technical constraints that necessitated the sub-region compromise.

Long-Read Technologies: Platforms such as Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) now routinely produce reads in excess of 1,500 bp, making it feasible to sequence the entire 16S rRNA gene in a single read [4]. While early versions of these technologies suffered from higher error rates, improvements in chemistry and computational methods have substantially improved accuracy. PacBio's Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) generates HiFi reads with accuracies exceeding 99% [4] [7].

Resolution of Intragenomic Variation: Full-length 16S sequencing reveals another layer of microbial diversity that was largely inaccessible with sub-region approaches: intragenomic variation between multiple copies of the 16S gene within a single bacterium [4]. This variation, when properly resolved, can provide strain-level discrimination that was previously only possible with whole-genome sequencing.

The historical focus on 16S sub-regions was a necessary compromise driven by the technological limitations of short-read sequencing platforms. While this approach enabled the rapid expansion of microbiome science by providing cost-effective, high-throughput taxonomic profiling at the genus level, it came at the cost of species-level resolution and introduced regional biases. The emergence of viable long-read sequencing technologies now makes full-length 16S sequencing increasingly accessible, providing superior taxonomic resolution and enabling more precise microbial characterization. As these technologies continue to evolve and become more cost-effective, they promise to overcome the historical compromise, ushering in a new era of precision in microbiome research.

For decades, 16S rRNA gene sequencing has been a cornerstone of microbial ecology, yet its application has been constrained by technological limitations. The historical compromise of sequencing short, hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4) provided cost-effective but low-resolution data, primarily enabling genus-level identification. The advent of third-generation, long-read sequencing platforms from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) has broken this compromise, making high-throughput sequencing of the full-length (~1500 bp) 16S rRNA gene a practical reality. This guide objectively compares the performance of full-length 16S sequencing against traditional short-read and Sanger sequencing alternatives. Supported by recent experimental data, it demonstrates that full-length sequencing delivers superior species and strain-level discrimination, which is critically enhancing biomarker discovery, clinical diagnostics, and drug development research.

Performance Benchmarking: Full-Length vs. Partial 16S Sequencing

Empirical studies consistently show that full-length 16S rRNA sequencing outperforms short-read approaches in taxonomic resolution, accuracy, and the ability to discover specific biomarkers.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Sequencing Approaches

| Metric | Short-Read (e.g., Illumina V3-V4) | Full-Length (e.g., ONT V1-V9) | Supporting Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species-Level Identification | Limited; primarily genus-level [11] [12] | High; enables precise species-level resolution [11] [12] | In CRC biomarker discovery, ONT identified specific pathogens like Fusobacterium nucleatum; Illumina could not [11]. |

| Taxonomic Accuracy/ Bias | Variable and region-dependent; prone to amplification bias [4] | More consistent and balanced representation [10] [4] | An in-silico experiment showed the V4 region failed to classify 56% of sequences to the correct species, unlike the full-length gene [4]. |

| Alpha Diversity Estimates | Can be underestimated [10] | Yields significantly higher diversity metrics [10] | In oropharyngeal swabs, a degenerate full-length primer set increased Shannon diversity from 1.85 to 2.68 (p<0.001) [10]. |

| Resolution of Strain-Level Variation | Limited | Potential to resolve intragenomic 16S copy variants [4] | PacBio CCS sequencing accurately resolved single-nucleotide polymorphisms between 16S gene copies within a single genome [4]. |

| Cost & Turnaround Time | Lower cost per sample in batches; longer wait times for batch completion [13] | Higher cost per sample but faster time-to-result for individual samples [13] [14] | A clinical workflow reduced time-to-result to 24 hours. Cost per test was ~$25.30 for ONT vs. $74 for Sanger [13] [14]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols from Key Studies

The following section details the methodologies from recent, influential studies that generated the comparative data cited above.

- Sample Collection: Oropharyngeal swabs were systematically collected from 80 human donors with no history of oral inflammation. Swabs were applied to teeth, tongue, and buccal mucosa before insertion into the pharynx.

- DNA Extraction: Nucleic acids were extracted using the Quick-DNA HMW MagBead kit (Zymo Research). Purity and concentration were assessed via NanoDrop spectrophotometry and Quantus Fluorometry.

- PCR Amplification: Two separate sequencing libraries were prepared from each sample using different forward primers (27F-I, the ONT standard; and 27F-II, a more degenerate variant) with the same reverse primer.

- Sequencing: Full-length 16S amplification was performed, and libraries were sequenced on ONT's MinION Mk1C platform.

- Data Analysis: Alpha diversity (Shannon index) and taxonomic profiles were statistically compared between primer sets. Results were benchmarked against a large-scale salivary microbiome reference dataset (n=1,989).

- Sample Type: Tracheal aspirates from patients with chronic critical illness.

- DNA Extraction Kits Compared: QIAamp BiOstic Bacteremia Kit (Qiagen), MagMAX Microbiome Ultra Kit (Thermo Fisher), and HostZero Kit (Zymo Research). The Zymo kit included a host DNA depletion step.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing:

- Illumina (V3-V4): Amplification of the V3-V4 hypervariable region.

- ONT (FL-16S): Amplification of the full-length 16S gene using 27F-1492R primers.

- Bioinformatics:

- Illumina reads were processed using the standard QIIME2 pipeline.

- ONT reads were processed using the Emu pipeline, which is specifically designed for error-prone long reads.

- Validation: Both methods were first applied to a standardized mock microbial community of known composition to assess accuracy and bias.

- Bacterial Isolates: 153 clinical isolates that could not be identified by MALDI-TOF MS.

- DNA Extraction: For ONT, DNA was extracted using the Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep kit (Zymo).

- Sequencing Methods:

- Sanger Sequencing: The first ~500 bp (V1-V3 region) was sequenced using the MicroSEQ 500 kit on an Applied Biosystems 3500 genetic analyzer.

- ONT Sequencing: Library preparation used the 16S Barcoding Kit (SQK-16S024) on FLO-MIN111 (R10.3) flow cells. Sequencing was performed on a GridION sequencer.

- Data Analysis: Sequences from both methods were classified using the SmartGene IDNS software and its 16S Centroid database. Discrepancies were resolved by whole-genome sequencing.

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a standardized workflow for a comparative full-length versus short-read 16S sequencing study, integrating key steps from the cited protocols.

Successful implementation of a full-length 16S sequencing workflow depends on careful selection of reagents, kits, and computational tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Full-Length 16S Sequencing

| Item | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized DNA Extraction Kits | To efficiently lyse diverse cell types (esp. Gram-positive) and minimize host DNA in low-biomass samples. | Quick-DNA HMW MagBead Kit [10], Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep Kit [14], MagMAX Microbiome Ultra Kit [12]. |

| Degenerate PCR Primers | To reduce amplification bias by accounting for sequence variation in conserved regions, improving taxonomic coverage. | Degenerate 27F-II primer showed superior diversity capture vs. standard 27F [10]. |

| Long-Range PCR Master Mix | To ensure efficient and accurate amplification of the full ~1500 bp 16S rRNA gene. | LongAmp Taq 2x MasterMix was used for full-length amplicon generation [13]. |

| ONT 16S Barcoding Kit | A streamlined, end-to-end kit for library preparation and barcoding of full-length 16S amplicons for multiplexing. | SQK-16S024 and SQK-16S114.24 kits were used in multiple studies [13] [14]. |

| R10.4.1 Flow Cells | ONT flow cells with updated chemistry that provides ~99% read accuracy, crucial for resolving single-nucleotide differences. | The use of R10.4.1 chemistry was key to achieving high species-level resolution [11] [12]. |

| Specialized Bioinformatics Pipelines | Software specifically designed to handle the higher error rate of long reads and provide accurate taxonomic assignment. | Emu [11] [12], NanoClust, and BugSeq 16S [12] pipelines are recommended over short-read tools. |

| Curated Reference Databases | High-quality, non-redundant databases essential for reliable species-level classification of full-length sequences. | Emu's default database [11], SILVA [11], and SmartGene's 16S Centroid database [14]. |

Discussion and Future Outlook

The accumulated evidence firmly establishes full-length 16S sequencing as a powerful tool for microbial discrimination. Its superior resolution is directly fueling advances in personalized medicine and drug discovery. In oncology, for example, the ability to identify specific cancer-associated species like Parvimonas micra and Bacteroides fragilis from patient microbiomes provides novel diagnostic biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets [11]. The technology's rapidly declining cost and faster turnaround time are making it increasingly accessible for clinical trial stratification and companion diagnostic development [15].

Future advancements will likely focus on overcoming remaining challenges, such as the need for standardized bioinformatic protocols and even more accurate reference databases. Furthermore, the integration of full-length 16S data with other omics layers (metagenomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics) through AI and cloud computing platforms promises a more holistic understanding of microbial function in health and disease [16]. As these technologies and analyses mature, full-length 16S sequencing is poised to become the new gold standard for high-resolution microbial community profiling.

The analysis of microbial communities through 16S rRNA gene sequencing has been a cornerstone of microbiome research for decades. Traditional approaches, primarily using short-read sequencing platforms like Illumina, sequence only specific hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4) due to read length limitations. This practice often restricts taxonomic resolution to the genus level and can introduce biases based on the variable region chosen [17] [18]. The advent of third-generation, long-read sequencing technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) has enabled the routine sequencing of the full-length 16S rRNA gene (~1,500 bp). This approach captures all nine variable regions within a single read, promising enhanced resolution down to the species and even strain level, thereby facilitating a deeper and more accurate understanding of gut microbiota composition and function [18]. This guide objectively compares the workflows, performance, and applications of PacBio HiFi and ONT platforms within the context of full-length 16S rRNA sequencing research.

Technology and Principle Comparison

The core technologies underpinning PacBio and ONT platforms are fundamentally different, leading to distinct operational characteristics and data output profiles.

PacBio HiFi Sequencing: This technology utilizes Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing. The process occurs within tiny wells called Zero-Mode Waveguides (ZMWs). A DNA polymerase enzyme incorporates fluorescently-labeled nucleotides into the DNA template strand. As each nucleotide is incorporated, it emits a flash of light that is detected in real-time, identifying the base. The key to HiFi (High-Fidelity) reads is Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS), where the same DNA molecule is sequenced repeatedly over its length. This multi-pass process generates a highly accurate consensus read with a typical accuracy exceeding 99.9% (Q30) [19] [20].

Oxford Nanopore Sequencing: ONT technology is based on the electrophoretic movement of DNA or RNA molecules through protein nanopores embedded in a membrane. An applied voltage drives the nucleic acids through the pores. As each nucleotide passes through, it causes a characteristic disruption in the ionic current. This change in current is measured and decoded in real-time to determine the DNA or RNA sequence. A significant advantage is its ability to sequence native DNA, allowing for direct detection of base modifications [19] [20].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental operational principles of each technology.

Performance and Experimental Data Comparison

Direct comparative studies and technical specifications reveal critical differences in the performance of these platforms for 16S rRNA sequencing. A 2025 study comparing Illumina (V3-V4), PacBio HiFi (full-length), and ONT (full-length) for rabbit gut microbiota analysis provides key experimental insights [18].

Taxonomic Resolution

A primary motivation for using full-length 16S sequencing is to achieve superior taxonomic resolution.

Table 1: Comparative Taxonomic Classification Resolution [18]

| Taxonomic Level | PacBio HiFi | Oxford Nanopore | Illumina (V3-V4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Level | ~99% | ~99% | ~99% |

| Genus Level | 85% | 91% | 80% |

| Species Level | 63% | 76% | 47% |

The study concluded that while both long-read platforms offered improved species-level resolution compared to Illumina, a significant portion of species-level assignments were labeled as "uncultured_bacterium," highlighting a limitation imposed by current reference databases rather than sequencing technology itself [18].

Technical and Operational Specifications

Beyond resolution, workflow and data output specifications are crucial for platform selection.

Table 2: Platform Technical Specifications for 16S Sequencing [19] [20] [18]

| Parameter | PacBio HiFi | Oxford Nanopore |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Principle | Fluorescent detection (SMRT) | Nanopore current sensing |

| Typical Read Length | 10 - 20 kb (HiFi reads) | 20 kb - >1 Mb |

| Raw Read Accuracy | ~85% (pre-CCS) | ~93.8% (R10.4.1 chip) |

| Consensus Accuracy | >99.9% (Q30) | ~99.996% (Q44) at 50x coverage |

| Typical 16S Run Time | ~24 hours | Up to 72 hours |

| Data Output per Run | 60 - 120 Gb (Revio/Vega) | 50 - 100 Gb (PromethION) |

| Throughput Booster | Kinnex 16S kits (12x increase) | Barcoding kits (SQK-16S024) |

| Primary Error Type | Random Indels | Systematic Indels in homopolymers |

| Basecalling | On-instrument, included | Off-instrument, may require GPU server |

| Portability | Benchtop systems | Portable (MinION) to benchtop |

Workflow Protocols and Experimental Design

A standardized experimental workflow for full-length 16S sequencing involves several key stages, from sample preparation to data analysis, with platform-specific nuances.

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

The initial steps are largely consistent across platforms, with critical attention to the PCR amplification step.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: High-quality, intact genomic DNA is extracted from samples (e.g., fecal material) using commercial kits like the DNeasy PowerSoil kit (QIAGEN). DNA quantity and quality must be assessed [18].

- Full-Length 16S Amplification: The nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene is amplified using universal primers 27F and 1492R, producing ~1,500 bp fragments.

- PacBio Protocol: PCR amplification is performed with a high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., KAPA HiFi Hot Start) over ~27 cycles. The primers are tailed with PacBio barcode sequences for multiplexing [18] [21].

- ONT Protocol: PCR amplification uses the 16S Barcoding Kit (e.g., SQK-RAB204 or SQK-16S024) over ~40 cycles, which also attaches barcodes [18].

- Library Preparation: The amplified DNA is purified, quantified, and pooled in equimolar concentrations.

Sequencing and Data Processing

Post-library preparation, the workflows diverge significantly based on the sequencing principle.

Bioinformatic Analysis: The high accuracy of PacBio HiFi reads allows them to be processed with the DADA2 pipeline, which models and corrects errors to generate high-resolution Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) [18]. In contrast, ONT reads, despite recent accuracy improvements, often retain a higher error rate that complicates ASV calling with DADA2. Consequently, a common approach for ONT data is to use pipelines like Spaghetti that cluster sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at a defined similarity threshold (e.g., 99%) [18]. For both platforms, the final high-quality sequences are imported into tools like QIIME2 for taxonomic assignment against reference databases (e.g., SILVA) and subsequent diversity analysis [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of a full-length 16S sequencing project requires a suite of specialized reagents and kits.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Full-Length 16S Sequencing

| Item | Function | Example Products & Kits |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolate high-quality microbial genomic DNA from complex samples. | DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) [18] |

| High-Fidelity PCR Mix | Amplify the full-length 16S gene with minimal errors for accurate sequencing. | KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (PacBio) [18] |

| Platform-Specific Library Prep Kit | Prepare amplicons for sequencing by adding platform-specific adapters and barcodes. | SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (PacBio) [18]; 16S Barcoding Kit (SQK-16S024, ONT) [18] |

| Throughput Enhancement Kit | Dramatically increase sample multiplexing and data yield for cost-effective studies. | Kinnex 16S rRNA Kit (PacBio) [21] |

| Sequencing Chemistry & Flow Cell | The consumables required to perform the sequencing reaction on the instrument. | Sequel II/Revio SMRT Cell & Chemistry (PacBio); Flongle/MinION/PromethION Flow Cell (ONT) [19] [18] |

| Bioinformatics Software/Pipeline | Process raw data, perform denoising/clustering, and conduct taxonomic & diversity analysis. | SMRT Link (PacBio), DADA2 (PacBio), Spaghetti (ONT), QIIME2 [18] |

The choice between PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore Technologies for full-length 16S rRNA sequencing is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather which is optimal for a given research context.

- Choose PacBio HiFi when the research question demands the highest possible single-read accuracy (Q30+) for confident base-calling and Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) generation, particularly in clinical or diagnostic settings where precision is paramount. Its recent Kinnex kits make large-scale studies highly cost-effective [21].

- Choose Oxford Nanopore when the application requires real-time data streaming, extreme portability for field-based sequencing, or access to the longest possible reads (megabase range). It is ideal for rapid pathogen identification or when rapid, on-site results are critical [19] [20].

Both technologies represent a significant advancement over short-read partial 16S sequencing, providing a more complete and resolved view of microbial communities. The decision should be guided by weighing the priorities of accuracy, speed, portability, and cost within the specific framework of the research project.

From Theory to Bench: Implementing Full-Length and Partial 16S Sequencing in Your Research

The analysis of the 16S rRNA gene has long been the cornerstone of microbial ecology, providing insights into the composition and dynamics of microbial communities across human health, environmental, and clinical settings. For years, standard practice relied on sequencing short, hypervariable regions (∼300-500 bp) using second-generation platforms like Illumina. However, a significant limitation of this approach is its restricted taxonomic resolution, often unable to differentiate between highly similar species—a critical shortcoming given that species from the same genus can have vastly different functional roles and clinical implications [7]. The emergence of third-generation, long-read sequencing technologies from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) has revolutionized this field by enabling the sequencing of the full-length ∼1,500 bp 16S rRNA gene. This comprehensive approach unlocks superior taxonomic resolution, allowing researchers to achieve species- and even strain-level identification [7] [22]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of PacBio's Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS)/HiFi technology and ONT's nanopore chemistry, framing their performance within the pivotal context of full-length versus partial 16S rRNA sequencing research.

Technology Principles and Sequencing Mechanisms

The fundamental difference between PacBio and ONT lies in their underlying sequencing biochemistry and signal detection methods. Understanding these mechanisms is key to interpreting their performance data.

PacBio CCS/HiFi Sequencing

PacBio's Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing takes place within tiny nanostructures called Zero-Mode Waveguides (ZMWs). A single DNA polymerase molecule is immobilized at the bottom of each ZMW, where it synthesizes a complementary strand to a single-stranded DNA template. The process uses fluorescently labeled nucleotides; each time a nucleotide is incorporated, a characteristic light pulse is emitted. These pulses are detected in real-time to determine the DNA sequence [20] [19]. The key to PacBio's high accuracy is the Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) approach. The same DNA molecule is sequenced repeatedly in a loop, generating multiple subreads for a single fragment. These subreads are then computationally combined to produce one highly accurate HiFi (High-Fidelity) read, which effectively corrects for random errors inherent in single-molecule sequencing [19].

Oxford Nanopore Sequencing

Oxford Nanopore technology is based on a fundamentally different principle: nanopore-based electrical signal detection. A protein nanopore is embedded in an electrically resistant membrane. An ionic current is passed through the pore, and as a single molecule of DNA or RNA is threaded through the nanopore, each nucleotide base causes a characteristic disruption in the current. This unique electrical signal is measured and decoded in real-time to determine the sequence [20] [23]. Unlike PacBio, this process does not require polymerase-driven synthesis or fluorescent labels. The technology also allows for direct sequencing of native DNA and RNA, facilitating the direct detection of epigenetic modifications [20] [23]. Recent advancements, such as the R10 and R10.4 nanopores with a dual-reader head design, have improved accuracy, particularly in resolving homopolymer regions [23].

The following diagram illustrates the core biochemical principles of each technology.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data Analysis

Direct comparisons of key performance metrics are essential for platform selection. The following table summarizes the core characteristics of PacBio HiFi and ONT sequencing, particularly in the context of 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing.

Table 1: Core Performance Metrics for PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore Sequencing

| Performance Metric | PacBio HiFi Sequencing | Oxford Nanopore Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Principle | Fluorescently labeled dNTPs + ZMWs [20] | Nanopore current sensing [20] |

| Typical Read Length (16S) | Full-length 16S (∼1.5 kb) [7] | Full-length 16S (∼1.5 kb) to ultra-long reads [22] |

| Raw Read Accuracy | ~85% (single pass) [20] | ~93.8% (R10 chip) [20] |

| Final Read Accuracy | >99.9% (HiFi read after CCS) [20] [19] | ~99.996% (consensus sequence, 50X depth) [20] |

| Typical Throughput | 120 Gb/run (Sequel IIe) [20] | Up to 1.9 Tb/run (PromethION) [20] |

| Run Time | ~24 hours [19] | ~24-72 hours [22] [19] |

| Relative Equipment Cost | High [20] | Lower (portable MinION available) [20] [24] |

The impact of these technical metrics is clearly demonstrated in taxonomic resolution. A 2024 study directly compared full-length 16S sequencing with PacBio to short-read Illumina sequencing of the V3-V4 regions. The results were striking: while both platforms assigned a similar percentage of reads to the genus level (∼95%), PacBio enabled a significantly higher proportion of reads to be assigned to the species level (74.14% for PacBio vs. 55.23% for Illumina) [7]. This demonstrates the tangible benefit of full-length 16S reads for achieving the species-level taxonomy that is often required for meaningful biological interpretation.

Application in 16S rRNA Sequencing: Experimental Protocols and Outcomes

Both platforms have established, optimized workflows for full-length 16S rRNA sequencing. Below is a generalized experimental pipeline, with platform-specific nuances noted.

Generalized Full-Length 16S rRNA Sequencing Workflow

Key Methodological Insights from Recent Studies

- PacBio Protocol (from BMC Genomics, 2024): The full-length 16S rRNA gene (V1-V9 regions) is amplified from isolated DNA using primers such as 27F and 1492R. The amplicons are used to construct a SMRTbell library, which is then sequenced on a platform like the Sequel II to generate HiFi reads. The high accuracy of HiFi reads allows for direct amplicon sequence variant (ASV) classification using standard tools like DADA2, providing single-nucleotide resolution for distinguishing between highly similar species [7].

- ONT Protocol (from Nanopore Workflow Overview): ONT also uses PCR to amplify the full-length 16S gene from gDNA, typically employing a barcoded kit (e.g., the 16S Barcoding Kit) to multiplex up to 24 samples. The amplified library is prepared with a sequencing adapter and loaded onto a flow cell (e.g., MinION). Sequencing occurs in real-time, and for optimal species-level resolution, it is recommended to sequence to 20x coverage per microbe using the high-accuracy (HAC) basecaller in the MinKNOW software [22].

- Throughput Innovations (PacBio Kinnex Kits): A significant recent development for PacBio is the introduction of Kinnex kits for full-length 16S rRNA sequencing. These kits concatenate multiple amplicons into a single molecule for sequencing, leading to a massive throughput increase of 8 to 12-fold. This makes large-scale studies vastly more economical, allowing, for example, 1,536 samples to be multiplexed on a Revio system [21].

- ONT in Clinical Diagnostics (Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol., 2025): ONT is being actively validated for clinical 16S diagnostics. Studies highlight its speed, scalability, and sensitivity compared to Sanger sequencing. Its ability to resolve polymicrobial infections—a known weakness of Sanger sequencing—and its lower cost compared to PacBio make it an appealing choice for routine clinical microbiology laboratories aiming to implement in-house, long-read 16S services [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful full-length 16S sequencing requires careful selection of laboratory reagents and materials. The following table outlines key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Full-Length 16S rRNA Sequencing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | To obtain high-quality, inhibitor-free microbial DNA from complex samples. | Recommended: ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit (water), QIAGEN DNeasy PowerMax Soil Kit (soil), QIAmp PowerFecal DNA Kit (stool) [22]. Bead beating often required for full lysis [24]. |

| Full-Length 16S PCR Primers | To amplify the entire ∼1.5 kb 16S rRNA gene from extracted gDNA. | Primers 27F (5'-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3') and 1492R (5'-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3') are commonly used [7]. |

| Library Prep Kit | To prepare amplicons for sequencing on the respective platform. | PacBio: SMRTbell Prep Kit [21].ONT: 16S Barcoding Kit (for multiplexing) [22]. |

| Barcodes/Indices | To tag individual samples, enabling multiplexing of multiple libraries in a single run. | Available from both PacBio and ONT. Crucial for cost-effectiveness in large-scale studies [22] [21]. |

| Sequencing Platform | The instrument used to generate sequence data. | PacBio: Sequel II/IIe, Revio systems [20] [21].ONT: MinION (portable), GridION, PromethION (high-throughput) [20] [22]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipeline | For data processing, demultiplexing, error-correction, and taxonomic assignment. | PacBio: SMRT Link software with HiFi-16S-workflow [21].ONT: EPI2ME wf-16s pipeline or custom tools (e.g., DADA2 for HiFi reads) [7] [22]. |

The choice between PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore sequencing is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather which technology is best suited to the specific research objectives, budget, and operational constraints.

- Choose PacBio HiFi sequencing when your research priority is achieving the highest possible accuracy for species-level taxonomic resolution. Its HiFi reads provide unparalleled single-molecule accuracy, which is critical for differentiating between closely related bacterial species or strains, as demonstrated in human microbiome studies [7]. This makes it ideal for clinical research, genome assembly, and any application where base-level precision is paramount. Furthermore, with the advent of Kinnex kits, PacBio now offers a highly scalable solution for large-scale 16S studies [21].

- Choose Oxford Nanopore sequencing when your application benefits from real-time data streaming, portability, or the lowest upfront equipment cost. ONT's unique advantages make it the platform of choice for rapid pathogen monitoring in outbreak settings, field sequencing in remote locations, and clinical point-of-care testing where quick turnaround is essential [20] [24]. Its ability to generate ultra-long reads can also be beneficial for spanning multiple conserved regions in complex microbial communities.

In the broader thesis of full-length versus partial 16S sequencing, the evidence is clear: sequencing the entire gene provides a definitive increase in taxonomic resolution over short-read approaches [7] [22]. Both PacBio and ONT effectively overcome the limitations of partial gene sequencing, enabling researchers to move beyond genus-level classifications and uncover the true diversity and composition of microbiomes at the species level. The decision, therefore, hinges on which long-read technology's performance profile best aligns with the goals of your specific research program.

In the field of microbiome research, the choice between standard and degenerate primers for full-length 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene amplification represents a critical methodological crossroads with profound implications for taxonomic accuracy and diversity assessment. Targeted amplicon sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene remains a cornerstone approach for investigating microbial communities, with its accuracy strongly dependent on the primer pairs selected for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification [25]. While standard primers consist of a single defined nucleotide sequence, degenerate primers incorporate mixtures of oligonucleotides with variability at specific positions, enabling broader matching across diverse bacterial taxa [25]. The expanding knowledge of unculturable bacterial sequences, coupled with advances in third-generation sequencing technologies capable of reading the entire ~1,500 bp 16S rRNA gene, has intensified the need to optimize primer design strategies [25] [8]. This guide objectively compares the performance of standard versus degenerate primer systems for full-length 16S rRNA amplification, providing researchers with evidence-based insights to inform experimental design in microbial community studies.

Primer Design Fundamentals: Balancing Specificity and Coverage

Effective primer design for full-length 16S rRNA amplification requires balancing multiple competing objectives: maximizing amplification efficiency and specificity, achieving comprehensive coverage of target microbial communities, and minimizing amplification bias [25]. The 16S rRNA gene contains nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) interspersed with conserved regions that serve as binding sites for PCR primers [26]. While standard primers with fixed sequences offer predictable melting temperatures and minimal synthesis complexity, their rigid structure may fail to accommodate natural sequence variation in conserved regions, potentially missing important taxonomic groups [8].

Degenerate primers address this limitation by incorporating nucleotide variability at specific positions, effectively representing multiple primer sequences in a single mixture [25]. This strategy expands potential binding sites across diverse bacterial lineages but introduces new challenges in maintaining experimental efficiency and specificity. The degree of degeneracy must be carefully optimized, as excessive variability can reduce effective primer concentration for any specific sequence and increase the likelihood of off-target amplification [27]. Computational approaches like multi-objective optimization simultaneously maximize efficiency, coverage, and minimize primer matching-bias, demonstrating that primer sets outperforming literature standards can be identified through systematic analysis [25].

Table 1: Fundamental Design Parameters for 16S rRNA Primers

| Parameter | Standard Primer Guidelines | Degenerate Primer Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 18-30 nucleotides [28] | Similar range, with degenerate positions strategically placed |

| GC Content | 40-60% [28] [27] | Maintained within range, considering all possible sequence combinations |

| Melting Temperature (Tₘ) | 50-65°C; primers in pair should have Tₘ within 2°C [28] [27] | Calculated based on all possible sequences in degenerate mixture |

| 3' End Stability | Avoid complementarity in 2-3 bases at 3' end; avoid T as ultimate base [28] | Particularly critical to maintain strong binding at 3' end despite degeneracy |

| Specificity Checking | BLAST analysis against target genome [27] | Must account for all possible sequences represented in degenerate mixture |

Comparative Performance Analysis: Standard vs. Degenerate Primers in Experimental Settings

Biodiversity Assessment in Complex Communities

Direct experimental comparisons reveal striking differences in taxonomic recovery between standard and degenerate primers. A comprehensive study of human fecal samples using nanopore sequencing compared the conventional 27F primer (27F-I) included in the Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) 16S Barcoding Kit with a more degenerate 27F primer (27F-II) [8]. The results demonstrated that the standard 27F-I primer revealed significantly lower biodiversity and an unusually high Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio compared to the degenerate primer set. When contextualized against gut microbiome profiles commonly reported in Western industrial societies (e.g., the American Gut Project), the more degenerate primer set (27F-II) better reflected expected composition and diversity [8].

These findings highlight how standard primers designed from limited datasets, primarily derived from culturable bacteria, may fail to capture the full spectrum of microbial diversity in complex samples. The inclusion of degeneracy at key variable positions enables primers to accommodate sequence divergence in unculturable taxa, thereby providing a more comprehensive community profile [8]. This enhanced coverage comes with the trade-off of potentially increased amplification of non-target sequences, necessitating rigorous in silico validation.

Impact on Taxonomic Resolution and Classification Accuracy

Full-length 16S rRNA sequencing fundamentally enhances taxonomic resolution compared to partial gene sequencing, regardless of primer type. Comparative analyses demonstrate that sequencing the entire 16S rRNA gene provides superior taxonomic resolution at the species level compared to targeting specific variable regions like V3-V4 or V4 alone [6] [29] [30]. However, primer choice significantly influences the efficacy of this approach.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Standard vs. Degenerate Primers in Experimental Studies

| Performance Metric | Standard Primers | Degenerate Primers | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Richness | Significantly lower biodiversity [8] | Higher observed biodiversity [8] | Human fecal microbiome (n=73 samples) |

| Community Composition Accuracy | Skewed composition (e.g., high Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio) [8] | Better reflection of expected community structure [8] | Comparison against American Gut Project benchmarks |

| Amplification Efficiency | Potentially reduced for taxa with primer binding site mismatches [26] | Broader coverage across diverse taxa [25] | In silico analysis of 57 primer sets against SILVA database |

| Species-Level Classification | Limited by primer-template mismatches [26] | Enhanced species-level resolution [25] | Mock community validation |

| Off-Target Amplification | Generally lower when well-designed [31] | Potentially higher without proper optimization [25] | Human gastrointestinal biopsy samples |

Research indicates that even with full-length 16S gene sequencing, limitations persist in achieving complete taxonomic resolution at the species level for complex samples like human skin [6]. However, carefully designed degenerate primers can improve resolution by reducing primer-template mismatches that compromise amplification efficiency for certain taxa [26]. Notably, computational evaluation of 57 commonly used 16S rRNA primer sets identified significant limitations in widely used "universal" primers, which often fail to capture extant microbial diversity due to unexpected variability in traditionally conserved regions [26].

Primer Binding Efficiency and Amplification Bias

The thermodynamic properties of primer-template binding differ substantially between standard and degenerate primers. Standard primers exhibit predictable melting behavior and uniform amplification efficiency across matched templates, while degenerate primers demonstrate variable binding strength depending on the specific sequence combination [25]. This variability can introduce amplification biases, where templates perfectly matching highly represented sequences in the degenerate mixture amplify more efficiently than those matching less represented sequences [25].

Intergenomic variation within the 16S rRNA gene further complicates primer binding efficiency. Shannon entropy analysis reveals substantial sequence variation even within traditionally conserved regions of the 16S rRNA gene [26]. This variation impacts primer performance differently across taxonomic groups, potentially introducing systematic biases in microbial community profiles. Optimal primer design must therefore account for the binding efficiency across the entire target community, not just for individual reference sequences [25].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

In Silico Primer Evaluation and Optimization

Computational methods provide essential tools for evaluating and optimizing primer performance before experimental validation. The mopo16S software tool (Multi-Objective Primer Optimization for 16S experiments) implements an algorithm that simultaneously maximizes three key objectives: (1) efficiency and specificity of target amplification; (2) coverage of different bacterial 16S sequences; and (3) minimization of differences in primer matching across sequences [25]. This approach can be applied to any desired amplicon length without affecting computational performance.

A comprehensive in silico evaluation protocol should include:

- Specificity Analysis: Use tools like Primer-BLAST to assess potential off-target amplification against relevant genome databases [27].

- Coverage Assessment: Evaluate primer matches against comprehensive 16S databases (e.g., SILVA, GreenGenes) using tools like TestPrime [26].

- Degeneracy Optimization: Balance the degree of degeneracy to maximize coverage while maintaining practical primer synthesis quality and effective concentration [25].

- Thermodynamic Properties: Calculate melting temperatures for all possible sequences in degenerate mixtures to ensure uniform amplification behavior [27].

Experimental Validation Workflows

Robust experimental validation of primer performance should include both mock communities and representative biological samples:

Mock Community Validation:

- Utilize defined mixtures of bacterial strains with known abundances [26] [30]

- Amplify with both standard and degenerate primer sets

- Sequence using appropriate long-read platforms (PacBio SMRT or Nanopore)

- Compare observed composition to expected abundances to quantify amplification bias [30]

Biological Sample Analysis:

- Process identical aliquots of representative samples with different primer sets

- Include technical replicates to assess reproducibility

- Evaluate alpha-diversity metrics, community composition, and taxonomic resolution [8]

- Compare results to established benchmarks when available (e.g., American Gut Project) [8]

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for evaluation and validation of 16S rRNA primers for full-length amplification, incorporating both in silico and experimental assessment stages.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Full-Length 16S rRNA Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Considerations for Primer Type Selection |

|---|---|---|

| 16S Reference Databases (SILVA, GreenGenes, RDP) | In silico primer evaluation and coverage assessment | Essential for designing and validating both standard and degenerate primers; critical for identifying regions of conservation for primer binding [25] [26] |

| PCR Optimization Kits (e.g., additive systems with DMSO or betaine) | Enhance amplification efficiency of complex templates | Particularly important for degenerate primers to maintain efficiency across different sequence variants; helps overcome secondary structure issues [27] |

| Long-Range Polymerase Systems (e.g., LongAMP Taq) | Amplify full-length ~1,500 bp 16S rRNA gene | Required for full-length amplification regardless of primer type; selection should consider fidelity and processivity [8] |

| Mock Microbial Communities (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS standards) | Experimental validation of primer performance | Critical for quantifying amplification bias and sensitivity of both standard and degenerate primer sets [26] [30] |

| Third-Generation Sequencing Platforms (PacBio SMRT, Oxford Nanopore) | Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing | Platform choice may influence optimal primer design; Nanopore enables direct PCR sequencing while PacBio offers higher single-read accuracy [6] [8] [29] |

The choice between standard and degenerate primers for full-length 16S rRNA amplification involves nuanced trade-offs that must be aligned with research objectives. Standard primers offer advantages in experimental consistency, predictable behavior, and minimal off-target amplification, making them suitable for well-characterized systems or when targeting specific taxonomic groups [28] [31]. Conversely, degenerate primers provide superior coverage of diverse microbial communities, particularly for exploratory studies aiming to capture the full extent of microbial diversity in complex samples [25] [8].

Evidence from comparative studies suggests that optimized degenerate primers generally outperform standard primers in comprehensive microbiome profiling, delivering more accurate representations of community structure and diversity [8]. However, this enhanced coverage requires careful optimization to minimize potential drawbacks including amplification bias, reduced efficiency, and increased computational complexity in design [25]. Researchers should prioritize degenerate primers when studying complex, poorly characterized microbial communities, while considering standard primers for targeted applications or when working with samples prone to off-target amplification [31].

As sequencing technologies continue to evolve and our knowledge of microbial diversity expands, primer design strategies must similarly advance. The development of novel computational approaches for multi-objective primer optimization represents a promising direction for maximizing coverage, efficiency, and specificity simultaneously [25]. Regardless of the approach selected, rigorous validation using both mock communities and biological samples remains essential for generating reliable, reproducible results in microbiome research.

The establishment of a robust wet-lab workflow for 16S rRNA sequencing is a critical foundation for reliable microbiome research. This process involves a series of carefully optimized steps from DNA extraction to library preparation, each introducing potential biases that can impact downstream results. The central challenge for researchers lies in selecting methodologies that accurately capture microbial community composition while balancing practical constraints. The choice between full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing and partial region sequencing represents a fundamental decision point with significant implications for taxonomic resolution, cost, and technical feasibility [6] [17].

Third-generation sequencing (TGS) technologies, pioneered by Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), have enabled high-throughput sequencing of the complete ~1,500 bp 16S rRNA gene, overcoming the read length limitations of earlier platforms [6] [4]. This technological advancement has sparked renewed investigation into whether the superior discriminatory power of full-length sequencing justifies its implementation compared to the well-established, more accessible partial gene approaches [4] [32]. This guide objectively compares these approaches through experimental data to inform researchers' workflow decisions.

Wet-Lab Workflow Fundamentals

DNA Extraction: The Critical First Step

The initial step of DNA extraction profoundly influences all subsequent results, as different protocols vary significantly in their efficiency for recovering genomic material from diverse bacterial species. A 2023 systematic comparison of four commercial DNA extraction methods demonstrated that protocol choice affects DNA yield, quality, and observed microbial diversity [33].

Key Considerations for DNA Extraction:

- Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative recovery: Protocols incorporating mechanical lysis (bead-beating) more effectively disrupt the thick peptidoglycan layer of Gram-positive bacteria [33].

- Sample homogenization: In gut microbiome studies, using a stool preprocessing device (SPD) upstream of DNA extraction improved standardization and increased DNA yield for three of four tested protocols [33].

- Yield and purity: The QIAGEN DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil kit combined with SPD preprocessing demonstrated the best overall performance for gut microbiota samples, balancing high DNA concentration, appropriate fragment size, and purity [33].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods with SPD Preprocessing

| Extraction Method | DNA Yield | Fragment Size | Purity (A260/280) | Gram-positive Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-DQ (SPD + DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil) | High | ~18,000 bp | 1.8 (optimal) | High |

| S-MN (SPD + NucleoSpin Soil) | Low | ~21,000 bp | <1.8 (low) | Moderate |

| S-QQ (SPD + QIAamp Fast DNA Stool) | Moderate | ~15,000 bp | ~2.0 (potential RNA) | Moderate |

| S-Z (SPD + ZymoBIOMICS DNA Mini) | High | ~18,000 bp | <1.8 (low) | High |

For specific sample types, optimized protocols are available. The ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit is recommended for environmental water samples, while the QIAGEN DNeasy PowerMax Soil Kit performs well with soil samples, and the QIAamp PowerFecal DNA Kit is optimized for stool samples [22].

Library Preparation Strategies

Library preparation approaches differ significantly between full-length and partial 16S rRNA sequencing, with each requiring specific primer designs and amplification conditions.

Full-Length 16S rRNA Amplification: The ONT 16S Barcoding Kit 24 V14 enables amplification of the complete ~1.5 kb 16S rRNA gene using barcoded primers, allowing multiplexing of up to 24 samples [34]. The protocol requires 10 ng of high molecular weight genomic DNA per barcode and uses LongAmp Hot Start Taq 2X Master Mix for amplification [34]. The cycling conditions consist of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (98°C for 10 seconds), annealing (55°C for 30 seconds), and extension (72°C for 90 seconds), with a final extension at 72°C for 2 minutes [6].

Partial 16S rRNA Amplification: For Illumina platforms targeting the V4 region, a common approach uses primers 515F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) [32]. The PCR conditions typically involve an initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 minutes, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 45 seconds), annealing (50°C for 60 seconds), and extension (72°C for 5 minutes), with a final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes [32].

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data

Taxonomic Resolution Across Platforms

Comparative studies consistently demonstrate that full-length 16S rRNA sequencing provides superior taxonomic resolution compared to single variable region approaches. A 2024 analysis of 141 skin microbiota samples revealed that while full-length sequencing cannot achieve 100% species-level resolution for complex communities, it significantly outperforms sub-region sequencing [6].

Table 2: Taxonomic Resolution Comparison Between Sequencing Approaches

| Sequencing Approach | Species-Level Resolution | Genus-Level Resolution | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-length 16S (PacBio) | Superior (near-complete) | Excellent | Enables discrimination of closely related species |

| V1-V3 region | Moderate | Excellent | Best performing sub-region for skin microbiota |

| V3-V4 region | Limited | Good | Preferred for Illumina platforms |

| V4 region | Poor | Good | Most limited species discrimination [4] |

| V5-V9 region | Variable | Good | Effective for Clostridium and Staphylococcus |

The limitation of partial gene sequencing stems from the distribution of discriminatory sequence variations across the entire 16S rRNA gene. Johnson et al. (2019) demonstrated that only 56% of V4 region sequences could be confidently classified to species level compared to nearly 100% with full-length sequences [4]. Different variable regions also exhibit taxonomic biases; V1-V2 performs poorly for Proteobacteria, while V3-V5 shows limited resolution for Actinobacteria [4].

Diversity Metrics and Quantitative Comparisons

Experimental comparisons of full-length versus V4-region 16S rRNA sequencing reveal notable differences in diversity assessments and bacterial abundance measurements. A 2022 mouse study comparing these approaches found that while V4 region data generated by Illumina MiSeq and in silico extracted from full-length PacBio data showed similar patterns, both differed significantly from the full-length analyses in relative bacterial abundances and α- and β-diversity metrics [32].

In this controlled experiment, mice fed a Western-type diet without or with inulin supplementation showed consistent platform-dependent variations:

- OTU counts: Full-length sequencing detected proportionally more OTUs, though a higher percentage of reads were discarded as singletons or due to alignment issues [32].

- Rarefaction analysis: Full-length sequencing approaches revealed greater microbial diversity at equivalent sequencing depths [4].

- Community composition: While broad taxonomic patterns were consistent, significant differences emerged at finer taxonomic levels [32].

These findings suggest that the sequence length of the 16S rRNA gene affects results and may lead to different biological interpretations, particularly for interventions that subtly affect microbiota composition [32].

Technology-Specific Workflows

Oxford Nanopore Full-Length 16S Protocol

The ONT 16S Barcoding Kit provides a streamlined workflow for full-length 16S rRNA sequencing [22] [34]:

Library Preparation Timeline:

- 16S barcoded PCR amplification: 10 minutes setup + PCR runtime (approximately 2 hours)

- Barcoded sample pooling and bead clean-up: 15 minutes

- Rapid adapter attachment: 5 minutes

- Priming and loading the flow cell: 10 minutes

This protocol requires specific equipment compatibility, including R10.4.1 flow cells and the MinION or GridION sequencing devices [34]. For optimal results, ONT recommends sequencing amplified libraries to 20x coverage per microbe using the high accuracy (HAC) basecaller on MinKNOW software for 24-72 hours, depending on microbial sample complexity [22].

Illumina Partial 16S Sequencing

Illumina platforms typically target one or two hypervariable regions, with V3-V4 and V4 being the most common choices [17]. The workflow involves:

- Platform selection: MiSeq for lower throughput, NovaSeq for larger studies

- Dual-indexing approach: Enables multiplexing of hundreds of samples

- Paired-end sequencing: 2×250 bp or 2×300 bp reads

- Automation compatibility: Liquid handling systems can streamline library prep

The Illumina approach benefits from established protocols, extensive reference databases, and higher throughput per run, but sacrifices the taxonomic resolution afforded by full-length gene sequencing [17] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 16S rRNA Sequencing Workflows

| Reagent/Kits | Manufacturer | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit | QIAGEN | DNA extraction from soil, stool, environmental samples | Optimal performance with SPD preprocessing [33] |

| ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit | ZymoResearch | DNA extraction from various sample types | Recommended for environmental water samples [22] |

| 16S Barcoding Kit 24 V14 | Oxford Nanopore | Full-length 16S amplification and barcoding | Enables multiplexing of 24 samples [34] |

| LongAmp Hot Start Taq 2X Master Mix | NEB | PCR amplification of full-length 16S | Used in ONT protocol for long amplicon generation [34] |

| AMPure XP Beads | Beckman Coulter | PCR clean-up and size selection | Standard for library purification in both platforms |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Invitrogen | DNA quantification | Essential for quality control pre-sequencing |

The establishment of a robust wet-lab workflow for 16S rRNA sequencing requires careful consideration of research objectives, technical constraints, and desired taxonomic resolution. Based on current experimental evidence:

- For maximum taxonomic resolution, particularly for species-level discrimination, full-length 16S rRNA sequencing using third-generation platforms provides superior performance [6] [4].

- For large-scale studies where cost-effectiveness and higher throughput are prioritized, partial 16S rRNA sequencing targeting the V1-V3 or V3-V4 regions represents a practical compromise [6] [17].

- DNA extraction methodology should be standardized within studies and optimized for specific sample types, with bead-beating incorporation essential for Gram-positive bacteria recovery [33].

The choice between full-length and partial 16S rRNA sequencing ultimately depends on the specific research question, with full-length approaches enabling more precise taxonomic assignment and partial methods providing cost-effective community profiling. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve and costs decrease, full-length 16S rRNA sequencing is increasingly becoming the gold standard for comprehensive microbial community characterization.

The choice between full-length and partial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing represents a critical methodological crossroads in microbiome research. For years, short-read sequencing of hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4) has been the standard approach for profiling complex microbial communities [35]. However, third-generation sequencing technologies from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and PacBio now enable researchers to sequence the entire ~1,500 bp 16S rRNA gene, spanning all nine variable regions (V1-V9) in a single read [11] [4]. This technological advancement offers a fundamental shift in the taxonomic resolution achievable for gut microbiome development studies, disease surveillance programs, and drug discovery pipelines.