From Simulation to Synthesis: A Practical Guide to Validating Computed Bimetallic Catalysts

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and scientists navigating the integrated process of computational prediction and experimental validation of bimetallic catalysts.

From Simulation to Synthesis: A Practical Guide to Validating Computed Bimetallic Catalysts

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and scientists navigating the integrated process of computational prediction and experimental validation of bimetallic catalysts. Covering the full spectrum from foundational screening descriptors like electronic density of states and d-band center to advanced synthesis strategies, characterization techniques, and stability optimization, it addresses critical challenges in catalyst development. By presenting validated high-throughput protocols, machine-learning-assisted modeling, and direct performance comparisons between predicted and synthesized catalysts, this guide serves as a strategic resource for accelerating the discovery of high-performance, cost-effective catalytic materials for advanced applications, including biomedical and chemical synthesis.

The Computational Blueprint: Screening and Descriptors for Bimetallic Catalyst Discovery

High-Throughput Computational Screening Protocols

High-throughput computational screening (HTCS) has emerged as a transformative approach in materials science and drug discovery, enabling the rapid identification of promising candidates from vast chemical spaces before resource-intensive experimental validation. This paradigm shift from traditional "trial-and-error" methods to computationally-driven research is particularly valuable in fields like bimetallic catalyst development, where experimental testing of all possible elemental combinations and structures remains practically impossible. The core principle involves leveraging computational models, primarily density functional theory (DFT) and molecular docking, to predict material properties and biological activities, thereby prioritizing the most promising candidates for experimental synthesis and testing [1] [2]. This protocol document details established methodologies for HTCS, framed within the context of validating computed bimetallic catalysts for experimental synthesis. The integrated computational-experimental workflow described herein aims to accelerate the discovery of novel materials while reducing associated costs and development timelines.

Computational Screening Methodologies

Density Functional Theory (DFT) for Catalytic Properties

DFT calculations form the backbone of HTCS for inorganic materials and catalysts. The protocol involves a multi-stage process to screen thousands of potential structures efficiently.

Initial Structure Generation and Thermodynamic Stability Screening: The process begins by defining the exploration space. For bimetallic catalysts, this typically involves selecting a set of transition metals (e.g., 30 metals from periods IV, V, and VI) and generating all possible binary combinations. For each binary system, multiple ordered crystal phases (e.g., B1, B2, L10) at specific compositions (e.g., 1:1) are constructed, easily amounting to thousands of initial structures [1]. The primary screening criterion is thermodynamic stability, assessed via the formation energy (ΔEf). Structures with ΔEf < 0.1 eV/atom are typically retained, as this indicates miscibility and potential synthetic feasibility, even for non-equilibrium phases that might be stabilized by nanosize effects [1].

Electronic Structure Analysis and Descriptor-Based Screening: The stable candidates undergo electronic structure calculation to determine properties that serve as proxies for catalytic activity. A common approach is to compute the projected density of states (DOS) on surface atoms and compare it to a known reference catalyst using a quantitative similarity metric [1].

The DOS similarity between a candidate alloy (DOS₂) and a reference catalyst like Pd (DOS₁) can be quantified as:

ΔDOS₂₋₁ = { ∫ [ DOS₂(E) - DOS₁(E) ]² g(E;σ) dE }^{1/2}

where g(E;σ) is a Gaussian distribution function centered at the Fermi energy (EF) that assigns higher weight to electronic states near EF, typically with σ = 7 eV [1]. This metric identifies materials with electronic structures analogous to high-performing catalysts, suggesting similar surface reactivity. It is crucial to include both d-states and sp-states in the DOS analysis, as sp-states can dominate interactions with certain adsorbates, such as O₂ in H₂O₂ synthesis [1].

Table 1: Key Descriptors for High-Throughput Screening of Catalysts

| Descriptor | Calculation Method | Predictive Value | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy (ΔEf) | DFT total energy difference between compound and constituent elements | Thermodynamic stability and miscibility | Initial filter for 4350 bimetallic alloys [1] |

| DOS Similarity | Integral of squared difference in DOS patterns, weighted near Fermi level | Similarity to known catalyst's electronic structure | Discovery of Pd-like Ni61Pt39 [1] |

| d-band Center | First moment of d-projected DOS | Adsorption energy of intermediates | Universal descriptor for transition metal surface reactivity [1] |

| Limiting Potential (UL) | Free energy difference along reaction coordinate | Activity volcano plots | Screening TM-Pc catalysts for CNRR [3] |

Diversity-Based High-Throughput Virtual Screening (D-HTVS) for Drug Discovery

For biomolecular targets, a common HTCS protocol is Diversity-Based High-Throughput Virtual Screening (D-HTVS). This method efficiently navigates large chemical libraries by initially screening a diverse subset of molecular scaffolds. The workflow proceeds as follows [4]:

- Diverse Scaffold Selection: A computationally manageable set of structurally diverse molecules (representing different scaffolds) is selected from a large compound library (e.g., the ChemBridge library).

- Stage I Docking: This diverse set is docked against the target protein(s) using high-throughput modes of docking algorithms like AutoDock Vina (e.g., with reduced exhaustiveness).

- Hit Scaffold Identification: The top 10 scaffolds based on docking scores are selected.

- Stage II Docking: All structurally related molecules in the full library with a Tanimoto similarity score >0.6 to the top scaffolds are retrieved and docked using more rigorous parameters.

This two-tiered approach balances broad exploration of chemical space with focused assessment of promising regions, optimizing computational resources [4].

Validation with Molecular Dynamics and Free Energy Calculations

Post-screening, top hits should undergo more rigorous validation via molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and binding free energy calculations. A standard protocol involves [4]:

- System Preparation: The protein-ligand complex is solvated in an explicit solvent model (e.g., SPC water) within a periodic boundary box. Ions are added to neutralize the system and mimic physiological concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl).

- Energy Minimization and Equilibration: The system is energy-minimized (e.g., using the Steepest Descent method for 5000 steps) and subsequently equilibrated under NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) and NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) ensembles.

- Production MD Run: A simulation is performed for a sufficient timeframe (e.g., 100 ns) using an integrator like leap-frog.

- Free Energy Calculation: The binding free energy (ΔG_binding) is computed using methods like MM-PBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) on multiple trajectory frames (e.g., from the last 30 ns of a 100 ns simulation) to ensure statistical reliability [4].

Integrated Experimental Validation Protocols

Computational predictions require rigorous experimental validation to confirm their real-world performance. The following protocols outline standard methods for testing computationally identified catalysts and drug candidates.

Experimental Synthesis and Catalytic Testing of Bimetallic Catalysts

For bimetallic catalysts predicted via HTCS, the experimental validation pipeline involves synthesis, characterization, and performance evaluation.

Synthesis: Nanoparticles of the predicted bimetallic compositions (e.g., Ni61Pt39) can be synthesized using wet chemical methods like co-reduction of metal precursors or impregnation methods. The specific conditions (temperature, pressure, solvent, reducing agents) must be optimized for each system.

Catalytic Performance Testing (e.g., H₂O₂ Direct Synthesis): A standard protocol for evaluating catalytic performance for reactions like H₂O₂ synthesis involves [1]:

- Reactor Setup: Use a fixed-bed or batch reactor system equipped with mass flow controllers for gases (H₂ and O₂) and temperature control.

- Reaction Conditions: Typically conducted under mild temperatures and pressures. The catalyst is exposed to a reactant gas mixture.

- Product Analysis: The reaction products are quantified using techniques like titration (e.g., with KMnO₄) or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to determine the yield and selectivity of H₂O₂.

- Control Experiments: Performance is benchmarked against a reference catalyst (e.g., pure Pd) under identical conditions.

- Cost-Normalized Productivity (CNP) Calculation: To assess economic potential, the catalyst's productivity is normalized by its cost, providing a metric like the 9.5-fold enhancement in CNP reported for Ni61Pt39 over Pd [1].

In Vitro Bioactivity and Potency Assays

For drug candidates identified through HTCS, a cascade of in vitro assays is used for validation.

Kinase Inhibition Assay (For EGFR/HER2):

- Objective: To determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) of the hit compound against the target kinase.

- Protocol: A commercial kinase assay kit is used. The reaction mixture contains the kinase enzyme, ATP, substrate, and the test compound at varying concentrations. After incubation, the amount of phosphorylated product is measured, often via luminescence or fluorescence. The IC₅₀ value is calculated from the dose-response curve, with promising candidates showing values in the nanomolar range (e.g., 37.24 nM for EGFR) [4].

Cell-Based Viability Assay (For Gastric Cancer Cells):

- Objective: To assess the compound's ability to inhibit the growth of relevant cell lines (e.g., KATOIII, Snu-5 gastric cancer cells).

- Protocol: Cells are seeded in 96-well plates and treated with a range of compound concentrations. After an incubation period (e.g., 72 hours), cell viability is measured using reagents like MTT or Alamar Blue. The half-maximal growth inhibitory concentration (GI₅₀) is determined, with effective compounds showing low nanomolar GI₅₀ (e.g., 48.26 nM) [4].

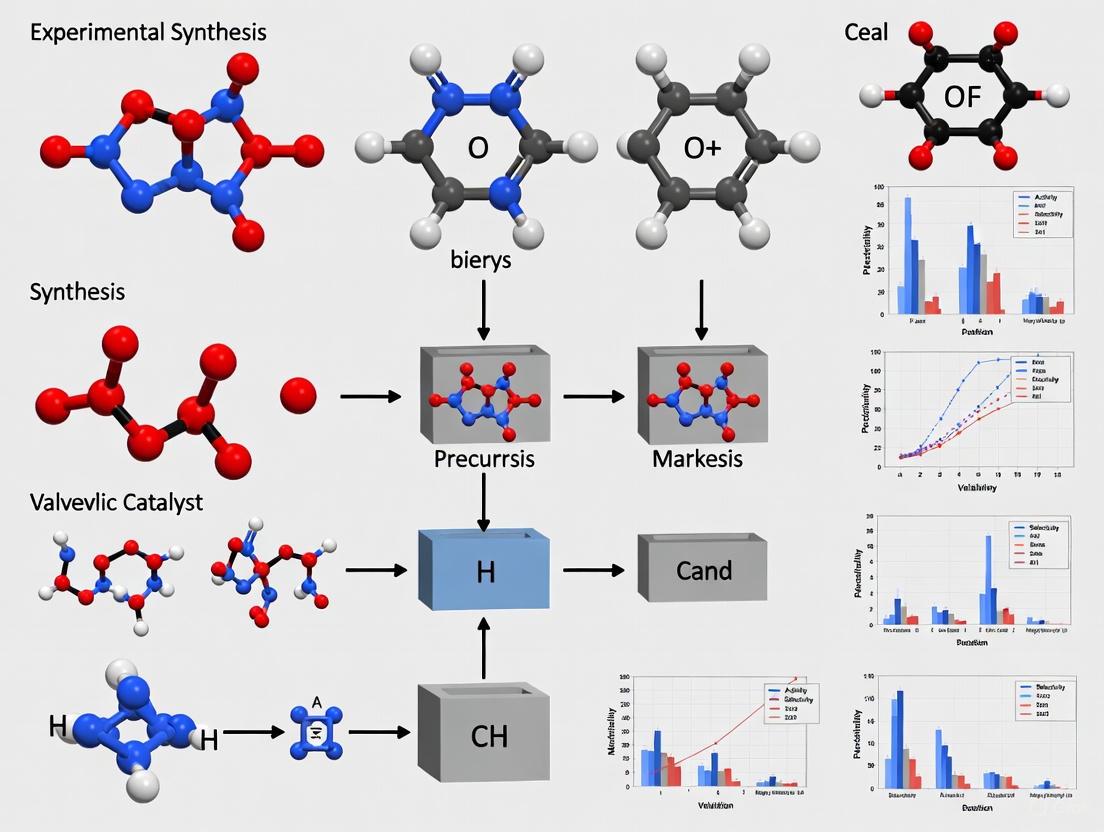

Diagram 1: Integrated high-throughput screening workflow, showing the parallel paths for material and drug discovery.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of HTCS and its experimental validation relies on a suite of computational software, chemical libraries, and experimental reagents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTCS and Validation

| Category | Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Software | Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) | First-principles DFT calculations for materials | Screening 4350 bimetallic structures [1] [3] |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking for drug-target interaction | D-HTVS of ChemBridge library [4] | |

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulations and trajectory analysis | Protein-ligand complex stability [4] | |

| Schrödinger AutoRW | Automated reaction workflow for high-throughput catalyst screening | Enterprise-scale catalyst screening [5] | |

| Compound & Material Libraries | ChemBridge Library | Small molecule library for virtual and HTS screening | >650,000 compounds for drug discovery [4] |

| Evotec Screening Collection | Curated compound library for experimental HTS | >850,000 diverse, drug-like compounds [6] | |

| Transition Metal Binary Alloys | Search space for bimetallic catalyst discovery | 435 binary systems, 10 phases each [1] | |

| Experimental Assay Kits | Kinase Assay Kits (e.g., EGFR, HER2) | In vitro enzymatic activity measurement | IC₅₀ determination for hit validation [4] |

| Cell Viability Assays (e.g., Alamar Blue) | Measurement of cell growth inhibition | GI₅₀ determination in cell lines [4] |

The high-throughput computational screening protocols detailed herein provide a robust framework for accelerating the discovery of novel bimetallic catalysts and therapeutic agents. The critical pathway involves a tightly integrated loop of computational prediction followed by rigorous experimental validation. As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, the role of HTCS is poised to expand further, becoming an indispensable component of modern materials science and drug discovery research. Future developments will likely focus on better integrating machine learning, automating experimental workflows, and improving the descriptors that bridge computational predictions with experimental outcomes, ultimately leading to a more efficient and predictive discovery paradigm.

The rational design of bimetallic catalysts is pivotal for advancing sustainable chemical processes and renewable energy technologies. A cornerstone of this design process is the use of computational descriptors that bridge a material's electronic structure with its catalytic properties, thereby guiding experimental synthesis and validation. For decades, the d-band center has served as a fundamental electronic descriptor for predicting adsorption energies and catalytic activity on transition metal surfaces.

Modern high-throughput computational studies, however, are increasingly moving beyond this single-value metric. The full Density of States (DOS) pattern provides a more comprehensive representation of the electronic environment, capturing shape characteristics and sp-band contributions that are crucial for understanding catalytic behavior [7] [1]. This article details the application of these electronic structure descriptors within an integrated workflow for discovering and validating bimetallic catalysts, providing the experimental protocols necessary to bridge computation and synthesis.

Key Electronic Structure Descriptors and Their Computation

The Fundamental d-Band Center

The d-band center (( \varepsilon_d )) is defined as the first moment of the d-band projected density of states. It represents the average energy of the d-states relative to the Fermi level and serves as a primary descriptor for surface reactivity [8].

Calculation Protocol:

- Perform a DFT calculation on your catalyst surface model until convergence.

- Locate the

DOSCARoutput file in your calculation directory. - Extract the projected DOS (PDOS) for the relevant surface atoms using processing scripts (e.g.,

split_dos). - The d-band center is calculated using the formula: [ \varepsilond = \frac{\int \rhod(E) E \, dE}{\int \rhod(E) \, dE} ] where ( \rhod(E) ) is the d-band density at energy ( E ) [9].

- Input the energy and d-DOS columns into a spreadsheet or script for numerical integration. For a Pd(111) surface, this yields a d-band center of approximately -1.59 eV [9].

Advanced d-Band Metrics

The d-band center alone does not capture the full shape of the DOS. Higher moments of the d-band provide additional insight [7]:

- d-band width (( d_w )): The second moment, indicating the degree of delocalization.

- d-band skewness (( d_s )): The third moment, measuring the asymmetry of the DOS spectrum.

- d-band kurtosis (( d_k )): The fourth moment, describing the "peakedness" of the distribution.

- Upper d-band edge (( d_u )): The position of the highest peak in the Hilbert-transformed DOS, which dictates the anti-bonding state location [7].

Full DOS Pattern Similarity

The full DOS pattern, incorporating both d- and sp-states, offers the most comprehensive electronic structure description. Its similarity to a reference catalyst's DOS can be a powerful screening descriptor [1].

Quantification Protocol: The similarity between two DOS patterns (e.g., an candidate alloy and Pd(111)) is quantified using a Gaussian-weighted difference: [ \Delta DOS{2-1} = \left{ \int \left[ DOS2(E) - DOS1(E) \right]^2 g(E; \sigma) dE \right}^{1/2} ] where ( g(E; \sigma) ) is a Gaussian function centered at the Fermi energy ( EF ) with a standard deviation ( \sigma ) (often set to 7 eV to cover the relevant energy range). A lower ( \Delta DOS ) value indicates higher similarity [1].

Table 1: Key Electronic Structure Descriptors for Catalytic Screening

| Descriptor | Definition | Physical Significance | Computational Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| d-Band Center | First moment of d-DOS | Average d-state energy; correlates with adsorption strength | Single value (eV) |

| d-Band Width | Second moment of d-DOS | Degree of orbital delocalization | Single value (eV) |

| d-Band Skurtosis | Fourth moment of d-DOS | Peakedness of the d-band distribution | Single value (unitless) |

| Upper d-Band Edge | Highest Hilbert peak | Position of anti-bonding states | Single value (eV) |

| Full DOS Similarity | Gaussian-weighted ΔDOS | Overall electronic structure match to a reference | Single value (a.u.) |

Integrated Workflow for Catalyst Discovery

The application of these descriptors follows a logical, sequential workflow from high-throughput computational screening to experimental synthesis and validation.

Computational Screening Protocol

Objective: To screen thousands of potential bimetallic compositions and identify promising candidates with electronic structures similar to high-performance noble metal catalysts.

Methodology:

- Define Chemical Space: Select constituent transition metals (e.g., 31 common 3d, 4d, and 5d metals) and generate binary/ternary intermetallic compounds from databases (e.g., the Materials Project) [7].

- Filter for Stability: Retain only synthetically accessible phases, typically those with an energy above the hull (Ehull) < 0.05 eV/atom [7].

- Generate Surface Models: Create low-Miller-index surfaces (e.g., (111), (110), (100)) from the stable bulk phases. Ensure slab models have sufficient vacuum (≥15 Å) and size (≥8 Å in periodic dimensions) [7].

- DFT Calculations: Perform high-throughput DFT calculations using software like VASP.

- Descriptor Analysis: Calculate the d-band center, higher moments, and full DOS similarity for all surface sites. For DOS similarity, use a Gaussian function with σ = 7 eV centered at the Fermi level to compare with the reference catalyst [1].

- Stability Assessment: Construct Pourbaix diagrams to evaluate the aqueous stability of top candidates under relevant electrochemical conditions [7].

Output: A shortlist of candidate materials with promising electronic descriptors and predicted stability.

Experimental Synthesis and Characterization Protocol

Objective: To synthesize the computationally predicted bimetallic catalysts and confirm their phase, structure, and reducibility.

Synthesis Protocol (Wet Impregnation for CuFe/Al₂O₃ Catalyst):

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve metal precursors (e.g., copper(II) chloride dihydrate and iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate) in deionized water to achieve the desired mass ratio (e.g., Cu:Fe = 3:1). Mix the solutions thoroughly [10].

- Support Impregnation: Add the support material (e.g., γ-Al₂O₃) to the mixed metal solution. Stir the suspension for 24 hours at room temperature to ensure uniform interaction [10].

- Drying: Pre-heat the mixture with stirring to evaporate the solvent, followed by drying in an oven at 120°C for 3 hours to obtain the catalyst precursor [10].

- Calcination: Homogenize the dried precursor and calcine in air at a defined temperature (e.g., 200-600°C) for 1 hour using a controlled heating ramp (e.g., 1°C/min) to form the oxide phases. The resulting material is denoted as

CuFe/Al2O3-cT, where T is the calcination temperature [10]. - Reduction: Activate the calcined catalyst under a flowing H₂/N₂ mixture (e.g., 30/70) with a heating ramp (e.g., 2°C/min) to a target temperature (200-600°C) for 1 hour to form the metallic phase. The resulting material is denoted as

CuFe/Al2O3-rT[10].

Characterization Protocol:

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Analyze the thermal decomposition profile and oxidative/reductive stability from room temperature to 600°C under air or H₂/N₂ [10].

- Temperature-Programmed Reduction (TPR): Evaluate the reducibility of metal oxide phases. Pre-treat the sample, then heat under a H₂/Ar flow while monitoring H₂ consumption with a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) [10].

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Identify crystalline phases present after calcination and reduction. Track the emergence of alloy phases and particle size [10].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Material / Reagent | Example Specification | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | Copper(II) chloride dihydrate (≥99.0%), Iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate (≥99.95%) | Precursors for active metal components |

| Catalyst Support | γ-Al₂O₃ (e.g., SASOL CATALOX SBa-200) | High-surface-area support to disperse metal particles |

| Reduction Gas | H₂/N₂ mixture (e.g., 30/70 or 6/94) | Reduces metal oxide precursors to active metallic state |

| Calcination Gas | Dry Air | Converts metal precursors to stable oxide phases |

| Probe Molecules | H₂, CO, NH₃ | For TPR, chemisorption, and catalytic activity tests |

Case Studies and Validation

Discovery of Pd-like Bimetallic Catalysts

In a landmark study, researchers screened 4350 bimetallic alloy structures using full DOS similarity to Pd(111) as the primary descriptor [1]. The screening identified eight promising candidates, including Ni₆₁Pt₃₉. Experimental synthesis and testing for H₂O₂ direct synthesis confirmed that four of these, including Ni₆₁Pt₃₉, exhibited catalytic performance comparable to Pd. Notably, the Pd-free Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ catalyst achieved a 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity, validating the predictive power of the DOS similarity descriptor [1].

Screening for Low-Cost Intermetallic HER/ORR Catalysts

A high-throughput study screened 2358 binary and ternary intermetallics, employing seven electronic structure descriptors (d-band center, width, skewness, kurtosis, upper edge, and two DOS-similarity descriptors) to find affordable alternatives to Pt and Ir for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) and Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) [7]. The workflow involved generating 12,057 surfaces from 462 stable bulk compositions. This multi-descriptor approach successfully pinpointed several new intermetallic catalysts with good predicted activity and aqueous stability, demonstrating the utility of moving beyond the d-band center alone [7].

Ru-Ni Alloys for Ammonia Decomposition

Combining computational screening with experimental validation, researchers identified Ru-Ni alloys as cost-effective catalysts for CO₂-free hydrogen production from ammonia. Computational analysis revealed a volcano-type relationship between NH₃ dissociation and N₂ adsorption energies, with Ru-Ni alloys exhibiting balanced energetics. Reactor tests confirmed that these bimetallic catalysts offered a viable, cheaper alternative to pure Ru, highlighting the role of electronic descriptors in optimizing bimetallic synergies [11].

The journey from the d-band center to full DOS patterns marks a significant evolution in the descriptor-based design of bimetallic catalysts. While the d-band center remains a foundational metric, the use of higher moments and especially the full DOS pattern provides a more nuanced and powerful tool for predicting catalytic behavior. The integrated workflow presented—combining high-throughput computation, multi-faceted electronic structure analysis, rigorous experimental synthesis, and thorough characterization—provides a robust protocol for discovering and validating new catalysts. This approach effectively bridges the gap between computational prediction and experimental reality, accelerating the development of high-performance, cost-effective bimetallic catalysts for a sustainable energy future.

Thermodynamic Stability Assessment of Alloy Structures

The rational design of bimetallic catalysts hinges on the precise assessment of their thermodynamic stability. Within the broader context of experimental synthesis validation for computed bimetallic catalysts, confirming thermodynamic stability is a critical gateway that determines whether a predicted alloy structure can be synthesized and persist under operational conditions, rather than undergoing phase separation or degradation [1] [12]. This protocol provides a detailed framework for integrating computational screening with experimental validation, ensuring that promising in silico predictions transition successfully into viable, stable catalysts. The core philosophy is to use computational efficiency to narrow the vast field of potential alloys, followed by rigorous experimental verification of their stability, thereby accelerating the discovery of novel catalytic materials [1].

Computational Screening for Thermodynamic Stability

High-throughput first-principles calculations serve as the first filter to identify thermodynamically feasible bimetallic alloy structures from a vast combinatorial space.

The computational screening process follows a staged workflow to efficiently identify promising candidates. The diagram below illustrates the key stages from initial candidate generation to final selection.

Key Computational Metrics and Protocols

Formation Energy Calculation

Protocol:

- Structure Selection: For a binary system A-B, enumerate all potential ordered phases at a 1:1 composition (e.g., B1, B2, L10, L11). A representative study screened 435 binary systems across 10 crystal structures each, totaling 4350 initial candidates [1].

- DFT Calculations: Perform first-principles calculations using Density Functional Theory (DFT) to compute the total energy of the alloy structure, ( E{total}(A-B) ), and the total energies of the pure elemental constituents, ( E{total}(A) ) and ( E_{total}(B) ).

- Energy Formulation: Calculate the formation energy (( \Delta Ef )) using the formula: ( \Delta Ef = E{total}(A-B) - \frac{1}{2}[E{total}(A) + E{total}(B)] ) A negative ( \Delta Ef ) indicates a stable compound, while a positive value signifies a tendency for phase separation [1].

- Stability Threshold: Apply a practical stability threshold. For instance, alloys with ( \Delta E_f < 0.1 ) eV may be considered for further study, acknowledging that non-equilibrium synthesis routes can sometimes stabilize metastable structures [1].

Electronic Structure Similarity Analysis

Protocol:

- DOS Projection: Calculate the projected electronic Density of States (DOS) for the closest-packed surface of the thermodynamically screened alloy.

- Reference Comparison: Compare this DOS to the DOS of a reference catalyst surface (e.g., Pd(111) for hydrogen peroxide synthesis) [1].

- Quantitative Similarity Score: Quantify the similarity using a defined metric. For example, the following equation incorporates a Gaussian weighting function to emphasize states near the Fermi level (( EF )), which are critical for catalysis: ( \Delta DOS{2-1} = \left{ {\int} {\left[ {DOS}2\left( E \right) - {DOS}1\left( E \right) \right]^2} {g}\left( {E;{\sigma}} \right) {{d}}E \right}^{\frac{1}{2}} ) where ( {g}\left( {E;\sigma } \right) = \frac{1}{{\sigma \sqrt {2\pi } }}{{e}}^{ - \frac{{\left( {E - E_{{{\mathrm{F}}}}} \right)^2}}{{2\sigma ^2}}} ) and ( \sigma ) is typically set to 7 eV [1].

- Candidate Selection: Alloys with a low ( \Delta DOS ) score (e.g., < 2.0) are prioritized as electronic analogs of the reference catalyst and proposed for experimental synthesis [1].

Quantitative Data from High-Throughput Screening

The following table summarizes key quantitative data and descriptors used in a representative high-throughput screening study for Pd-like bimetallic catalysts [1].

Table 1: Key Metrics from a High-Throughput Screening of Bimetallic Catalysts [1]

| Screening Metric | Description | Value or Criterion | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Candidates | Binary combinations of 30 transition metals (Periods IV-VI) | 435 binary systems | Define the search space |

| Crystal Structures | Ordered phases considered per binary system | 10 structures (e.g., B1, B2, L10) | Account for polymorphic possibilities |

| Total Structures Screened | Total number of DFT calculations | 4,350 structures | Initial computational load |

| Formation Energy (ΔEf) | Thermodynamic stability filter | ΔEf < 0.1 eV | Shortlist miscible/meta-stable alloys |

| DOS Similarity (ΔDOS) | Electronic similarity to Pd(111) | ΔDOS < 2.0 | Identify electronic analogs |

| Final Proposed Candidates | Alloys passing all filters | 8 candidates | Targets for experimental validation |

Experimental Validation of Stability and Synthesis

The computationally proposed candidates must undergo experimental validation to confirm their stability and assess their synthetic feasibility.

The experimental validation process involves synthesizing the proposed candidates and using multiple characterization techniques to confirm their structure and stability. The diagram below outlines this multi-technique approach.

Key Experimental Protocols

Synthesis via Wet Impregnation and Thermal Treatment

Protocol (Adapted from CuFe Bimetallic Catalyst Synthesis) [10]:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve metal precursors (e.g., copper(II) chloride dihydrate and iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate) in deionized water to achieve the desired molar ratio (e.g., Cu:Fe mass ratio of 3:1). Mix the solutions thoroughly for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Impregnation and Drying: For supported catalysts, add the support material (e.g., Al₂O₃) to the mixed solution and stir for 24 hours. Pre-heat the resulting mixture with stirring, gradually increasing temperature from room temperature to 40°C, 60°C, 80°C, and finally 100°C until complete evaporation of the solvent.

- Calcination: Air-treat the dried precursor at 120°C for 3 hours. Subsequently, homogenize the material and calcine it in air at a defined heating ramp (e.g., 1°C/min) to a target temperature (e.g., 200–600°C) and hold for 1 hour to form the oxide phases. The sample can be labeled as

CuFe-cT, whereTis the calcination temperature. - Reduction: Reduce the calcined sample under a flowing H₂/inert gas mixture (e.g., H₂/N₂ 30/70) at a specific flow rate (e.g., 30 mL/min) using a defined heating ramp (e.g., 2°C/min) to a target temperature (e.g., 200–600°C) and hold for 1 hour to obtain the metallic phase. The sample can be labeled as

CuFe-rT.

Tracking Structural Evolution and Stability

Protocol (Using Combined Analytical Techniques) [10]:

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA):

- Purpose: To monitor mass changes during oxidation and reduction, identifying temperature ranges of precursor decomposition, oxide formation, and reduction.

- Method: Heat the sample from room temperature to 600°C at a ramp of 10°C/min under a dry air (for oxidation) or H₂/N₂ (for reduction) atmosphere.

- Hydrogen Temperature-Programmed Reduction (H₂-TPR):

- Purpose: To probe the reducibility of oxide phases and identify metal-support interactions.

- Method: Pre-treat the catalyst at 600°C in N₂. Then, pass a H₂/Ar (10/90) stream over the sample while heating at 10°C/min to 600°C. Monitor H₂ consumption with a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD).

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD):

- Purpose: To identify crystalline phases present after calcination and reduction, confirming the formation of the desired alloy and detecting phase segregation.

- Method: Perform XRD on samples treated at different temperatures. Use Rietveld refinement to quantify phase compositions and track the emergence of new phases, such as a Cu₄Fe alloy [10].

- Textural Characterization (N₂ Physisorption):

- Purpose: To determine surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution, which can indicate metal dispersion and stability against sintering.

- Method: Analyze the catalyst after synthesis and after reaction. A significant drop in surface area may indicate sintering or pore blockage [13].

Application Notes: Validation via Catalytic Testing

The ultimate validation of a catalyst's stability is its performance under relevant reaction conditions.

- Procedure: Test the synthesized bimetallic catalysts in the target reaction (e.g., hydrogen peroxide direct synthesis [1] or furfural hydrogenation [10]). Compare activity, selectivity, and stability against the reference catalyst (e.g., Pd) and monometallic counterparts.

- Success Metric: A successful outcome is a catalyst that not only shows comparable or superior activity but also maintains its performance over time, indicating resistance to deactivation via sintering, leaching, or phase separation. For example, the discovery and validation of Ni61Pt39, which outperformed Pd with a 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity, exemplifies a successful outcome of this protocol [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for executing the thermodynamic stability assessment and synthesis protocols outlined above.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bimetallic Catalyst Assessment

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Source of active metals for catalyst synthesis. | Metal salts (e.g., CuCl₂·2H₂O, Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O [10]); choice affects dispersibility and decomposition temperature. |

| Catalyst Support | High-surface-area material to disperse and stabilize metal nanoparticles. | Al₂O₃ [10] [13], SiO₂, TiO₂ [14], or magnetic Fe₃O₄ [14]; influences metal-support interaction and acidity. |

| Reducing Agents | To convert metal precursors or oxides into active metallic states. | H₂ gas (for TPR and in-situ reduction) [10], NaBH₄ (for chemical reduction) [15]. |

| Calcination Atmosphere | To decompose precursors and form stable oxide phases. | Dry air or O₂ stream; temperature and flow rate must be controlled [10]. |

| Reference Catalysts | Benchmark for catalytic performance and electronic structure. | Pure metal catalysts (e.g., Pd) [1]; essential for validating predictions and performance comparisons. |

| DFT Software & Databases | For high-throughput calculation of formation energies and electronic structures. | First-principles codes (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO); crystallographic databases for structure enumeration [1]. |

The integrated computational-experimental protocol detailed herein provides a robust roadmap for assessing the thermodynamic stability of alloy structures within bimetallic catalyst research. By sequentially applying high-throughput DFT screening for formation energy and electronic similarity, followed by rigorous experimental synthesis and multi-technique characterization, researchers can efficiently bridge the gap between theoretical prediction and experimental validation. This approach mitigates the high cost and time investment associated with purely experimental trial-and-error, as demonstrated by the successful discovery of novel, stable, and highly productive catalysts such as Ni61Pt39 [1]. Adherence to this structured protocol enables the targeted development of thermodynamically stable bimetallic catalysts, accelerating their deployment in energy and chemical conversion processes.

Leveraging Machine Learning for Initial Candidate Selection

The discovery of high-performance bimetallic catalysts is pivotal for advancing sustainable energy and environmental technologies. Traditional experimental methods, which often rely on systematic trial-and-error, are time-consuming and resource-intensive [16]. The integration of machine learning (ML) with computational and experimental workflows has emerged as a powerful paradigm to accelerate this discovery process. By leveraging ML for initial candidate selection, researchers can efficiently navigate vast compositional and structural spaces to identify promising bimetallic systems for targeted applications, thereby reducing the reliance on serendipity and intuition-based approaches. This Application Note details structured protocols for employing ML-driven screening, validated through experimental synthesis and testing, within the broader context of bimetallic catalyst research.

Machine Learning Screening Workflows and Data Presentation

The initial screening of bimetallic catalysts using machine learning involves several sophisticated computational strategies. The core objective is to predict key catalytic properties, such as adsorption energies of reaction intermediates, which serve as proxies for catalytic activity and selectivity.

Key Screening Descriptors and Models

The table below summarizes the primary ML models, descriptors, and applications identified from recent literature for screening bimetallic catalysts.

Table 1: Machine Learning Models and Descriptors for Bimetallic Catalyst Screening

| ML Model / Framework | Key Descriptor(s) | Catalytic Application | Key Findings / Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOS Similarity Screening [1] | Full electronic Density of States (DOS) pattern | H₂O₂ direct synthesis | Discovered Ni₆₁Pt₃₉; 9.5-fold cost-normalized productivity gain over Pd. |

| CatBoost Model [17] | Composition, support, preparation & reaction conditions | Methane Dry Reforming | High accuracy (R² = 0.918); guided design of Ni-Ru/MgAl₂O₄ (90% CH₄ conversion). |

| XGBoost Regressor [18] | Pauling electronegativity, d-orbital electron count | Ethane Direct Dehydrogenation | Identified Nb₃Pt and V₃Rh as promising catalysts. |

| Lattice Distortion-Guided ML [19] | Lattice distortion, strain sensitivity | Photo-Fenton CIP degradation | Screened 400 Fe-Ni combinations; 5Fe-20Ni@SC achieved 99.6% CIP degradation. |

| Cost-Effective Workflow [20] | Geometry-based (GLaSS) descriptor | Ammonia Decomposition | Predicted adsorption energies for H, N, NHx on CoMoFeNiCu HEA with low computational cost. |

Workflow for ML-Guided Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the generalized, iterative workflow for machine learning-guided discovery of bimetallic catalysts, integrating computational screening with experimental validation.

Experimental Synthesis and Validation Protocols

The candidates identified through computational screening must be rigorously validated experimentally. This section provides a detailed protocol for the synthesis, characterization, and performance testing of selected bimetallic catalysts, using successful examples from the literature as a guide.

Synthesis of Supported Bimetallic Nanoparticles

Objective: To synthesize bimetallic nanoparticles dispersed on a high-surface-area support. Example: Synthesis of Ni-Ru/MgAl₂O₄ for methane dry reforming [17].

Materials:

- Metal Precursors: Nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) and Ruthenium chloride (RuCl₃).

- Support: MgAl₂O₄ spinel.

- Reductant: Hydrogen gas (H₂).

- Solvent: Deionized water.

Procedure:

- Impregnation: Dissolve the calculated amounts of Ni and Ru precursors in deionized water to achieve the target metal loading (e.g., 5-10 wt.% total metal). Add the MgAl₂O₄ support to the solution and stir vigorously for 4-6 hours at room temperature to ensure homogeneous adsorption of metal ions.

- Drying: Remove the water by evaporation using a rotary evaporator or by heating in an oven at 100-120 °C for 12 hours.

- Calcination: Heat the dried powder in a muffle furnace under a static air atmosphere. The temperature is typically raised to 400-500 °C at a ramp rate of 2-5 °C/min and held for 4 hours. This step converts the metal salts into their corresponding oxides.

- Reduction: Activate the catalyst by reducing the metal oxides to their metallic state. Place the calcined material in a quartz tube reactor and expose it to a flowing H₂/Ar gas mixture (e.g., 10% H₂) while raising the temperature to 500-700 °C (as determined by ML-guided reduction temperature) for 2-4 hours.

Catalyst Characterization Protocol

Objective: To determine the physical and chemical properties of the synthesized bimetallic catalyst.

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): To confirm the formation of alloyed phases and identify crystal structures. The absence of separate monometallic peaks and the shift in diffraction angles indicate alloy formation [1] [17].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): To analyze the surface composition and electronic states (oxidation states) of the bimetallic components, providing evidence for electronic synergy [17] [19].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): To determine the particle size, size distribution, and morphology of the bimetallic nanoparticles. High-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) can further reveal lattice fringes and core-shell structures [17].

- Temperature-Programmed Reduction (TPR): To study the reducibility of the metal oxides and understand the metal-support interactions.

Catalytic Performance Testing

Objective: To evaluate the activity, selectivity, and stability of the catalyst under relevant reaction conditions. Example: Testing for H₂O₂ direct synthesis [1] or methane dry reforming [17].

- Reactor Setup: A fixed-bed continuous-flow reactor system equipped with mass flow controllers for gases, a temperature-controlled furnace, and an on-line gas chromatograph (GC) for product analysis.

- Standard Testing Procedure:

- Catalyst Loading: A known mass of the reduced catalyst (e.g., 100 mg) is loaded into the reactor tube.

- Reaction Conditions:

- Temperature: Set as guided by ML models (e.g., 850 °C for DRM [17]).

- Pressure: Typically atmospheric pressure or as required.

- Feed Composition: e.g., H₂ and O₂ for H₂O₂ synthesis; CH₄ and CO₂ for DRM.

- Gas Hourly Space Velocity (GHSV): Controlled to vary reactant contact time.

- Product Analysis: Effluent gases are analyzed periodically by GC to determine reactant conversion and product selectivity.

- Key Performance Metrics:

- Conversion: (%) of the key reactant (e.g., CH₄).

- Selectivity: (%) towards the desired product (e.g., H₂/CO ratio for syngas, H₂O₂ for synthesis).

- Stability: Measured by monitoring conversion over an extended time-on-stream (e.g., 24-100 hours).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Bimetallic Catalyst Research

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Salts | Precursors for active bimetallic phases (e.g., Ni, Pt, Ru, Fe). | Nitrates (Ni, Fe), chlorides (Ru, Pt) for impregnation [17] [19]. |

| Porous Support Materials | High-surface-area carriers to stabilize and disperse metal nanoparticles. | MgAl₂O₄, Al₂O₃, sludge-derived carbon (SC) [17] [19]. |

| Reducing Agents | To convert metal precursors into active metallic states. | H₂ gas, sodium borohydride (NaBH₄) [15]. |

| Gaseous Reactants | Feedstock for catalytic reactions. | H₂, O₂, CH₄, CO₂, C₂H₆ [1] [17] [18]. |

| Structure-Directing Agents | To control nanoparticle morphology during synthesis. | Surfactants (e.g., CTAB), polymers (e.g., PVP) [15]. |

The integration of machine learning for the initial selection of bimetallic catalyst candidates represents a transformative approach in materials science. The protocols outlined herein—from the use of advanced ML models and descriptors to detailed experimental validation—provide a robust framework for accelerating the discovery of next-generation catalysts. This structured, data-driven methodology significantly shortens the development cycle, enhances the likelihood of success, and paves the way for more sustainable and economical catalytic processes. The continuous feedback between prediction, synthesis, and testing, as illustrated in the workflow, is crucial for iterative improvement and fundamental understanding, ultimately enriching the broader thesis of computed-experimental catalyst research.

Bridging Theory and Experiment: Synthesis and Characterization Techniques

The development of high-performance bimetallic catalysts is a cornerstone of advanced materials research, particularly for sustainable energy and environmental applications. The integration of computational screening with experimental synthesis has emerged as a powerful paradigm for accelerating catalyst discovery. As computational predictions identify promising bimetallic compositions with tailored electronic structures, the imperative falls upon experimentalists to fabricate these materials with precise control over structure-property relationships [1]. The selection of synthesis method—sol-gel, impregnation, or co-precipitation—profoundly influences critical catalyst attributes including metal dispersion, particle size, metal-support interactions, and ultimately, catalytic performance [21].

This Application Note provides detailed protocols for these three fundamental synthesis techniques, contextualized within a framework of experimental validation for computationally predicted bimetallic catalysts. We present standardized methodologies, comparative performance data, and practical guidance to enable researchers to bridge the gap between theoretical prediction and experimental realization.

Synthesis Methods and Comparative Analysis

The journey from a computed bimetallic formulation to a physically realized catalyst requires careful selection of an appropriate synthesis pathway. Sol-gel methods excel in creating highly homogeneous materials with fine microstructural control through inorganic polymerization reactions [22]. Impregnation techniques, particularly sequential approaches, offer straightforward manipulation of metal-metal and metal-support interactions by controlling the order of precursor deposition [23]. Co-precipitation facilitates the simultaneous formation of active phases and support matrix, often yielding enhanced structural stability and synergistic effects in bimetallic systems [24].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Advanced Synthesis Methods for Bimetallic Catalysts

| Synthesis Method | Key Advantages | Structural Characteristics | Validated Bimetallic Systems | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sol-Gel | High compositional homogeneity; Tailorable porosity; Low-temperature processing | High surface area; Uniform metal dispersion; Controlled nanoparticle size | Pt-Co/Al₂O₃ [25]; Ni/Al₂O₃ [21] | 62.26 mmol H₂ g⁻¹ plastic from polystyrene steam reforming [21]; 97.6% acetic acid conversion in steam reforming [25] |

| Impregnation | Simple methodology; Wide applicability; Independent control of support properties | Dependent on impregnation sequence; Variable metal dispersion | Ni-Zn/ZrO₂ [26]; Pt-Ni/C [27] | Smaller NiO crystallite size in sequential (14.79 nm) vs. co-impregnation (19.45 nm) [26]; Intimate metal alloying with co-ED [27] |

| Co-Precipitation | Strong metal-support interaction; Thermal stability; Synergistic effects | Formation of defined crystalline phases; High metal dispersion | Ni-Co hydrotalcites [24]; Ni/Al₂O₃ [21] | 72% increase in photo-catalytic CO₂ methanation under UV/vis vs. thermal [24]; Lower performance vs. sol-gel for plastic reforming [21] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The selection of synthesis methodology directly correlates with catalytic performance metrics across various reactions. Quantitative comparisons reveal method-dependent outcomes in activity, selectivity, and stability.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics by Synthesis Method

| Catalytic System | Synthesis Method | Reaction Application | Key Performance Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni/Al₂O₃ | Sol-Gel | Pyrolysis-steam reforming of waste plastics | 62.26 mmol H₂ g⁻¹ plastic; Surface area: 305.21 m²/g; Ni particle size: 15.40 nm | [21] |

| Ni/Al₂O₃ | Co-Precipitation | Pyrolysis-steam reforming of waste plastics | Lower H₂ production; Amorphous coke deposits | [21] |

| Ni/Al₂O₃ | Impregnation | Pyrolysis-steam reforming of waste plastics | Intermediate performance between sol-gel and co-precipitation | [21] |

| Pt-Co/Al₂O₃ | Sol-Gel Auto-combustion | Acetic acid steam reforming | 97.6% acetic acid conversion; 96.6% H₂ yield at 650°C | [25] |

| Monometallic Ni (Hydrotalcite) | Co-Precipitation | CO₂ Methanation (Photocatalytic) | 72% activity increase under UV/vis light at >100 K lower temperature | [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Bimetallic Catalyst Synthesis

Sol-Gel Auto-Combustion Synthesis

Application Note: This protocol describes the synthesis of bimetallic Pt-Co/Al₂O₃ catalysts using citric acid (CA) and ethylene glycol (EG) assisted sol-gel auto-combustion, optimized for hydrogen production via acetic acid steam reforming [25].

Materials and Equipment:

- Precursor salts: Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, H₂PtCl₆

- Solvents and chelating agents: Deionized water, citric acid (CA), ethylene glycol (EG)

- Support material: gamma-Al₂O₃

- Equipment: Heating mantle or hot plate, magnetic stirrer, muffle furnace, ceramic crucible

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve 2.3 g Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O and 1.0 g H₂PtCl₆ in 18 g deionized water.

- Chelating Agent Addition: Add stoichiometric quantities of CA and EG to the solution at a molar ratio of EG:CA:Metal ions = 6:3:1, based on optimization studies [25].

- Support Incorporation: Introduce gamma-Al₂O₃ support to the solution mixture.

- Gel Formation: Stir continuously while gradually heating to 80°C until a viscous gel forms.

- Auto-Combustion: Transfer the gel to a muffle furnace preheated to 300°C. The gel will undergo self-ignition, resulting in a voluminous solid.

- Calcination: Calcine the resulting powder at 600°C for 3 hours to remove residual organics and crystallize the metal oxide phases.

Critical Parameters for Validation:

- EG/CA/Metal ions ratio significantly influences textural properties, reducibility, basic sites, and metal dispersion [25].

- The optimal ratio of 6:3:1 yielded the highest acetic acid conversion (97.6%) and H₂ yield (96.6%) in steam reforming at 650°C.

Sol-Gel Auto-Combustion Workflow for Pt-Co/Al₂O₃ Catalyst Synthesis

Sequential Impregnation Synthesis

Application Note: This protocol details the sequential impregnation method for bimetallic Ni-Zn/ZrO₂ catalysts, highlighting the significant influence of impregnation order on catalyst structure and performance [26].

Materials and Equipment:

- Precursor salts: Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O

- Support material: ZrO₂

- Solvent: Deionized water

- Equipment: Rotary evaporator, drying oven, muffle furnace

Step-by-Step Procedure (Sequential Impregnation - Cat-2):

- First Metal Impregnation: Dissolve the first metal precursor (e.g., Zn(NO₃)₂) in deionized water. Add ZrO₂ support to the solution and mix thoroughly.

- Drying and Calcination: Remove solvent using rotary evaporation. Dry at 120°C for 12 hours followed by calcination at 500°C for 4 hours.

- Second Metal Impregnation: Dissolve the second metal precursor (e.g., Ni(NO₃)₂) in deionized water. Impregnate the previously modified support from step 2.

- Final Drying and Calcination: Repeat drying at 120°C for 12 hours and calcination at 500°C for 4 hours.

Co-Impregnation Alternative (Cat-1): For comparison, prepare a catalyst via co-impregnation by simultaneously dissolving both metal precursors before support incorporation, followed by identical drying and calcination steps.

Critical Parameters for Validation:

- Impregnation sequence dramatically affects crystallite size: sequential impregnation yielded smaller NiO crystallites (14.79 nm) compared to co-impregnation (19.45 nm) [26].

- Sequential impregnation resulted in lower overall crystallinity but more homogeneous metal distribution [26].

Co-Precipitation Synthesis

Application Note: This protocol describes the preparation of Ni-Co bimetallic catalysts derived from hydrotalcite-like materials (HTlcs) for CO₂ methanation under thermal and photocatalytic conditions [24].

Materials and Equipment:

- Precursor salts: Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Mg(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Al(NO₃)₃·9H₂O

- Precipitation agents: NaOH, Na₂CO₃

- Equipment: pH meter, pressure filter, drying oven, muffle furnace

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a 1 M mixed metal salt solution in Milli-Q water with M²⁺/M³⁺ molar ratio of 3:1 (M³⁺/(M²⁺+M³⁺) = 0.25). Maintain nominal metal content according to desired composition (e.g., 8Co-19Ni, 6Co-21Ni, 27Ni) [24].

- Precipitation: Simultaneously add freshly prepared 2 M NaOH and 0.125 M Na₂CO₃ solutions to the metal salt solution under constant stirring until pH reaches 10.0 ± 0.2.

- Aging and Crystallization: Maintain the slurry at the final pH with continuous stirring for 24 hours at room temperature.

- Filtration and Washing: Separate the precipitate by pressure filtration and wash thoroughly with deionized water to remove Na⁺ and NO₃⁻ ions.

- Drying: Dry the filter cake overnight at 373 K (100°C).

- Calcination: Calcine the dried material at 773 K (500°C) for 5 hours using a heating ramp of 5 K/min.

Critical Parameters for Validation:

- The Ni-Co ratio determines catalytic performance: monometallic Ni demonstrated higher activity than bimetallic Co-Ni, which outperformed monometallic Co [24].

- Photocatalytic testing showed a 72% activity increase for monometallic Ni under UV and visible light irradiation at temperatures >100 K lower than conventional thermal reactions [24].

Computational-Experimental Validation Framework

High-Throughput Screening Protocol

The integration of computational screening with experimental validation represents a powerful approach for accelerated catalyst development, as demonstrated for bimetallic catalysts targeting Pd replacement [1].

Computational Screening Phase:

- Descriptor Selection: Utilize the full electronic density of states (DOS) pattern as a key descriptor for catalytic properties, providing more comprehensive information than d-band center alone [1].

- Similarity Quantification: Calculate ΔDOS between candidate bimetallic alloys and reference catalyst using Gaussian-weighted integration:

[ \Delta DOS{2-1} = \left{ \int \left[ DOS2(E) - DOS_1(E) \right]^2 g(E;\sigma) dE \right}^{1/2} ]

where ( g(E;\sigma) = \frac{1}{\sigma\sqrt{2\pi}} e^{-\frac{(E-E_F)^2}{2\sigma^2}} ) with σ = 7 eV [1].

- Thermodynamic Stability Assessment: Evaluate formation energies (ΔEf) of 4350 possible bimetallic structures, applying a margin of ΔEf < 0.1 eV for synthetic feasibility [1].

Experimental Validation Phase:

- Synthesis of Top Candidates: Prepare computationally identified candidates (e.g., Ni₆₁Pt₃₉, Au₅₁Pd₄₉, Pt₅₂Pd₄₈, Pd₅₂Ni₄₈) using appropriate methods.

- Catalytic Testing: Evaluate performance for target reactions (e.g., H₂O₂ direct synthesis).

- Validation Metrics: Four of eight predicted candidates exhibited catalytic properties comparable to Pd, with Pd-free Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ showing 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity [1].

Computational-Experimental Validation Workflow for Bimetallic Catalysts

Advanced Characterization for Validation

Comprehensive characterization is essential for validating whether synthesized catalysts achieve the predicted structural features. Key techniques include:

- H₂ Temperature-Programmed Reduction (H₂-TPR): Evaluates reducibility of oxide phases and metal-support interactions [10].

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Tracks evolution of crystalline phases during synthesis and identifies alloy formation [10].

- N₂ Physisorption: Determines textural properties (surface area, pore volume, pore size distribution) [25].

- In-situ DRIFTS: Probes surface reactions and reaction mechanisms [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bimetallic Catalyst Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Synthesis | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, H₂PtCl₆ | Source of active metallic components | Aqueous solubility enables impregnation; decomposition temperature affects metal dispersion |

| Chelating Agents | Citric Acid (CA), Ethylene Glycol (EG) | Complex metal ions; control gelation; prevent premature precipitation | EG:CA:Metal ratios critical in sol-gel auto-combustion; optimal ratio 6:3:1 for Pt-Co/Al₂O₃ [25] |

| Support Materials | γ-Al₂O₃, ZrO₂, Hydrotalcite | High surface area foundation; structural stability; electronic promotion | ZrO₂ provides low Lewis acidity and basic sites; Al₂O₃ offers high surface area and stability |

| Precipitation Agents | NaOH, Na₂CO₃ | Control pH for hydroxide/carbonate precipitation | Concentration and addition rate critical for hydrotalcite formation [24] |

| Structure Directing Agents | Various surfactants/templates | Control pore architecture and particle morphology | Not used in basic protocols but enable advanced morphological control |

The experimental validation of computationally predicted bimetallic catalysts demands meticulous attention to synthesis methodology. As demonstrated across multiple catalytic systems, the selection between sol-gel, impregnation, and co-precipitation methods directly governs critical structural parameters that dictate catalytic performance. The sol-gel method emerges as particularly effective for achieving high metal dispersion and controlled nanostructures, while impregnation offers practical advantages for sequential metal deposition. Co-precipitation facilitates strong metal-support interactions beneficial for thermal stability.

The integration of standardized synthesis protocols with high-throughput computational screening creates a powerful feedback loop for catalyst development. By adopting the detailed application notes and experimental protocols provided herein, researchers can systematically bridge the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization, accelerating the discovery and optimization of next-generation bimetallic catalysts for sustainable energy and environmental applications.

Influence of Preparation Methods on Metal Dispersion and Alloy Formation

The performance of bimetallic catalysts in applications ranging from hydrogen production to greenhouse gas conversion is critically governed by their structural properties, specifically metal dispersion and the extent of alloy formation. These characteristics are not inherent to the material composition alone but are predominantly determined by the chosen catalyst preparation method. Within the broader context of experimental synthesis validation for computed bimetallic catalysts, this protocol details how specific synthesis pathways directly influence these critical structural parameters, thereby determining the catalyst's ultimate activity, stability, and resistance to deactivation. A controlled synthesis process is the essential bridge that transforms a theoretically predicted bimetallic composition into a functionally validated catalyst.

Quantitative Comparison of Preparation Methods and Outcomes

The table below summarizes the performance of bimetallic catalysts prepared via different methods, highlighting the direct impact of synthesis protocol on key metrics such as alloy formation, stability, and conversion efficiency.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Bimetallic Catalysts Based on Preparation Method

| Catalyst System | Preparation Method | Key Outcome (Alloy Formation & Dispersion) | Catalytic Performance | Stability & Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt-Ru/CGO [28] | Incipient Wetness Impregnation (IWI) | Separate crystallization of Pt and Ru; no alloy formation. | — | Lower stability and coke resistance. |

| Pt-Ru/CGO [28] | Combustion Synthesis (GNP) | Exsolution and formation of PtRu alloy nanoparticles. | — | Higher stability and coke resistance. |

| Pt-Ni/MgO [29] | One-Pot Sol-Gel | Formation of a Pt-Ni alloy; enhanced metal-support interaction. | CH4 conversion: 97.2%; CO2 conversion: 61.4% | Stable for 220 h; strong resistance to sintering and carbon deposition. |

| Ni-Pt [1] [30] | High-Throughput Screening & Synthesis | Successful formation of Ni-Pt alloy. | Outperformed Pd prototype; 9.5-fold cost-normalized productivity for H₂O₂ synthesis. | — |

| xCu-Ni/SiO₂ [31] | Stepwise Method from Phyllosilicates | Formation of Cu-Ni alloy; inhibited Ni particle mobility. | CH4 conversion: 88.8%; CO2 conversion: 94.0% | Stable for 50 h; enhanced resistance to sintering and coking. |

| Rh1Co3/CoO [32] | Controlled Oxidation/Reduction | Formation of singly dispersed bimetallic sites (Rh1Co3). | 100% selectivity for NO reduction to N₂ at 110 °C. | — |

Experimental Protocols for Key Preparation Methods

This protocol is designed to achieve strong metal-support interaction and homogeneous alloy formation.

- Reagents: Platinum nitrate solution (Pt(NO₃)₂, 15 wt% Pt), Nickel(Ⅱ) nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, ≥99%), Magnesium nitrate hexahydrate (Mg(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, ≥99%), β-cyclodextrin (≥98%), Citric acid (≥99.5%), Deionized water.

- Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve stoichiometric amounts of platinum nitrate, nickel nitrate hexahydrate, and magnesium nitrate hexahydrate in deionized water in a beaker.

- Complexation: Add β-cyclodextrin and citric acid to the metal nitrate solution. Stir the mixture thoroughly until a homogeneous solution is obtained.

- Gelation: Heat the solution at 80°C under continuous stirring until it transforms into a viscous gel.

- Drying: Transfer the gel to an oven and dry at 120°C for 12 hours to remove residual water.

- Calcination: Calcinate the dried solid in a muffle furnace at 800°C for 5 hours to form the metal oxide support with incorporated metals.

- Reduction: Reduce the calcined catalyst under a hydrogen atmosphere at 800°C for 2 hours to form the active Pt-Ni alloy nanoparticles.

This method utilizes an exothermic reaction to create a homogeneous solid solution, facilitating subsequent metal exsolution and alloy formation.

- Reagents: Glycine (NH₂CH₂COOH), Cerium(III) nitrate hexahydrate (Ce(NO₃)₃·6H₂O), Gadolinium(III) nitrate hexahydrate (Gd(NO₃)₃·6H₂O), Platinum tetraamine nitrate (Pt(NH₃)₄(NO₃)₂), Ruthenium(III) nitrosyl nitrate (Ru(NO)(NO₃)₃).

- Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve glycine and the nitrate precursors of Ce, Gd, Pt, and Ru in deionized water. The total molar ratio of metal nitrates to glycine is maintained at 1:2.

- Combustion Reaction: Heat the solution on a hot plate at approximately 300°C. The mixture will dehydrate, ignite, and undergo a self-sustaining combustion reaction, resulting in a fluffy solid product.

- Calcination: Calcinate the resulting powder in air at 800°C for 2 hours to ensure the formation of a crystalline Gd-doped CeO₂ (CGO) support with Pt and Ru incorporated into the lattice.

- In-situ Reduction during Reaction: Under the reducing environment of the catalytic reaction (diesel reforming), the Pt and Ru ions exsolve from the oxide lattice, migrating to the surface to form firmly anchored PtRu alloy nanoparticles.

This advanced protocol focuses on creating atomically dispersed bimetallic sites on a non-metallic support.

- Reagents: Cobalt oxide (Co₃O₄) nanorods, Rhodium(III) salt (e.g., RhCl₃), Oxygen gas, Hydrogen gas (5% in balance).

- Procedure:

- Support Preparation: Synthesize Co₃O₄ nanorods via a colloidal method.

- Precipitation of Rh: Introduce Rh³⁺ ions to the surface of the Co₃O₄ nanorods in an aqueous solution, leading to the precipitation of Rh(OH)ₓ species.

- Oxidative Anchoring: Calcinate the material at 150°C in O₂. This step forms Rh–O–Co bonds, anchoring the rhodium to the support surface as isolated Rh1On species.

- Controlled Reduction: Reduce the catalyst in 5% H₂ at 300°C. This critical step partially removes oxygen atoms, forming direct Rh–Co bonds and creating the isolated Rh1Co3 bimetallic sites. Over-reduction at higher temperatures must be avoided to prevent the formation of bimetallic nanoparticles.

Workflow for Catalyst Design and Validation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental workflow for discovering and validating bimetallic catalysts, from initial screening to performance evaluation.

Diagram: Integrated computational-experimental workflow for bimetallic catalyst development, highlighting the central role of preparation method selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key reagents and their functions in the preparation of bimetallic catalysts, as cited in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bimetallic Catalyst Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Nitrate Precursors (e.g., Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Mg(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) | Source of active metal and support cations; nitrates facilitate decomposition during calcination. | One-pot sol-gel synthesis of Pt-Ni/MgO [29]. |

| Glycine | Fuel in combustion synthesis; complexing agent to achieve homogeneous mixing of metal cations. | Combustion synthesis of PtRu/CGO catalyst [28]. |

| β-Cyclodextrin & Citric Acid | Chelating and complexing agents in sol-gel method; prevent premature phase segregation, ensuring atomic-level mixing. | One-pot sol-gel synthesis [29]. |

| Hydroxyapatite (HAP) Support | High-surface-area support with specific surface properties that influence metal dispersion and reactivity. | Support for VPt bimetallic catalysts in amide hydrogenation [33]. |

| Palladium (Pd) Reference | Benchmark/prototypical catalyst for performance comparison in screening studies. | Reference for discovering Ni-Pt catalysts for H₂O₂ synthesis [1]. |

| Cobalt Oxide (Co₃O₄) Nanorods | Reducible oxide support that enables the formation of singly dispersed bimetallic sites via controlled redox processes. | Support for Rh1Co3 bimetallic sites [32]. |

In the experimental validation of computed bimetallic catalysts, the choice of support material is not merely a structural consideration but a critical determinant of catalytic performance. Support materials including alumina, silica, and mixed metal oxides provide far more than just a high surface area for dispersing active metal sites; they participate actively in catalytic cycles through metal-support interactions, dictate catalyst stability under operational conditions, and influence reaction pathways through their intrinsic acid-base properties. The integration of computational predictions with experimental synthesis requires a deep understanding of how support characteristics govern the dispersion, reducibility, and electronic structure of bimetallic nanoparticles. This application note provides a systematic framework for selecting, synthesizing, and characterizing support materials to effectively bridge computational predictions with experimental validation in bimetallic catalyst research.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Bimetallic Catalysts on Different Supports

| Catalyst System | Support Material | Application | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-Fe (10 wt% Fe) | Alumina (γ-Al₂O₃) | CO₂ Methanation | Highest activity at 220°C; declined performance above 300°C | [34] |

| Ni-Fe (2 wt% Fe) | Alumina (γ-Al₂O₃) | CO₂ Methanation | Superior performance at 320°C | [34] |

| Fe-Mg | Alumina (γ-Al₂O₃) | EPS Pyrolysis | 96% liquid yield at 400°C; 45% reduction in reaction time | [13] |

| Ni (5%) | 10Si+90Al | Methane Partial Oxidation | 54% H₂ yield; H₂/CO ratio of 3.4 at 600°C | [35] |

| CoFe/Fe₃O₄ | Defect-rich carbon | CO₂ Hydrogenation | 30% CO₂ conversion; 99% CO selectivity at 450°C | [36] |

Support Material Properties and Selection Criteria

Structural and Textural Properties

The structural integrity and textural properties of support materials directly influence the dispersion and stability of bimetallic nanoparticles. Alumina supports typically exhibit surface areas ranging from 50-500 m²/g with pore volumes of 0.2-0.76 cm³/g, providing excellent anchoring sites for metal particles [37]. The incorporation of silica into alumina frameworks creates mixed oxides with tunable acidity and surface characteristics, though this often reduces overall surface area and pore volume as silica content increases [35]. For instance, increasing silicon content in Ni/Al₂O₃+SiO₂ catalysts from 5% to 50% progressively decreases surface area while maintaining consistent pore diameter around 11.3-11.4 nm [35].

Acid-Base Characteristics

The surface acidity of support materials plays a pivotal role in reactions requiring acid-base catalysis. Silica-alumina materials possess medium-strong tunable acidity with both Brønsted and Lewis acid sites, making them versatile for various catalytic applications [37]. The acid strength can be optimized to balance activity against deactivation rates, particularly in hydrocarbon processing where strong acid sites often lead to rapid coking. The genesis of acidity in amorphous silica-aluminas has been attributed to the "Al-stuffed silica model" where tetrahedral Al ions incorporate into the silica framework, generating protonic acidity [37].

Metal-Support Interactions

Strong metal-support interactions (SMSI) significantly influence catalytic performance by affecting reduction kinetics, metal dispersion, and electronic properties of active sites. In alumina-supported NiFe catalysts, iron enhances catalyst reducibility at low temperatures while decreasing hydrogen chemisorption and strengthening CO₂ adsorption sites [34]. The oxidation state of iron in these systems can change under reaction conditions, demonstrating the dynamic nature of metal-support interactions during catalysis [34]. Similarly, in Ni/SiO₂+Al₂O₃ systems for methane partial oxidation, the interaction between NiO and the support governs nickel particle size and catalytic activity [35].

Experimental Protocols for Support Synthesis and Modification

Sol-Gel Synthesis of Modified Alumina Supports

The sol-gel method enables precise control over support morphology and composition at relatively low processing temperatures. For synthesis of NiO-Fe₂O₃-SiO₂/Al₂O₃ catalysts:

- Precursor Preparation: Combine aluminum isopropoxide (Al(O-iPr)₃) as the alumina precursor with tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) as the silica source in ethanol solvent. Add nickel and iron nitrate salts to achieve desired Ni/Fe ratio (typically 1:1 for optimal homogeneity).

- Hydrolysis and Polycondensation: Conduct controlled hydrolysis by adding acidified water (pH 3-4) dropwise under vigorous stirring. The hydrolysis ratio (moles H₂O/moles alkoxide) should be maintained at 4:1 to ensure complete reaction.

- Aging and Drying: Age the resulting gel for 24 hours at 60°C, then dry at 110°C for 12 hours to remove solvent.

- Thermal Treatment: Calcine the dried material with precise heating rate control (optimal: 5°C/min) to a final temperature of 400-500°C for 4 hours. Avoid heating rates exceeding 6°C/min to prevent microcrack formation and phase separation [38].

This method produces catalysts with specific surface areas up to 134.79 m²/g and particle sizes of approximately 44 nm, while avoiding the formation of difficult-to-reduce NiAl₂O₄ spinel phases that commonly occur with conventional impregnation methods [38].

Mechanochemical Synthesis for Metal Oxide Incorporation

Mechanochemical synthesis offers an environmentally benign alternative for preparing metal-incorporated alumina supports with controlled porosity:

- Grinding Procedure: Combine boehmite (γ-AlOOH) precursor with appropriate metal salts (e.g., Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O, Cu(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) and Pluronic P123 as a pore-generating agent in a ball mill apparatus.

- Optimized Milling Parameters: Process for 3 hours at 350 rpm using a ball-to-powder ratio of 10:1. This duration maximizes surface area development without excessive energy consumption.

- Thermal Processing: Calcine the resulting powder at 450°C for 2 hours to remove the template and crystallize the γ-alumina phase.

This method produces γ-alumina with incorporated metal oxides (Fe, Cu, Zn, Bi, Ga) with surface areas up to 320 m²/g, significantly higher than commercial γ-alumina (96 m²/g) [39]. The incorporated metal oxides enhance functionality for specific applications, with Fe₂O₃-incorporated alumina achieving 70% NO conversion in selective catalytic reduction at 450°C [39].

Support Modification with Sulfated Metal Oxides

Sulfated metal oxides create strong Brønsted and Lewis acid sites for applications requiring superacidic properties:

- Impregnation Method: Prepare a 0.5M H₂SO₄ solution and slowly add to the metal oxide support (ZrO₂, TiO₂, or SnO₂) with continuous stirring for 2 hours.

- Drying and Calcination: Dry the impregnated material at 110°C for 12 hours, then calcine at 550°C for 4 hours to stabilize the sulfate groups on the support surface.

- Characterization: Confirm successful functionalization through FTIR analysis (characteristic S=O stretching vibrations at 1350-1380 cm⁻¹) and temperature-programmed desorption of ammonia to quantify acid site strength and distribution.

Sulfated zirconia on SBA-15 (S-ZrO₂/SBA-15) catalysts prepared using this method achieve 96.4% biodiesel yield in just 10 minutes under subcritical methanol conditions (140°C, 2.0% catalyst, 10:1 methanol-to-oil ratio) and maintain 90% yield after five reaction cycles [40].

Table 2: Characterization Data for Supported Bimetallic Catalysts

| Characterization Technique | Key Parameters Measured | Representative Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| N₂ Physisorption | Surface area, pore volume, pore size distribution | FeMg/Al₂O₃: 40% decrease in surface area after metal impregnation | [13] |

| XRD | Crystalline phases, particle size | γ-Al₂O₃ with characteristic (311), (400), (440) reflections; NiO, Fe₂O₃ phases | [38] [35] |

| H₂-TPR | Reducibility, metal-support interaction | Fe enhanced NiFe/Al₂O₃ reducibility at low temperatures | [34] |

| TEM/STEM | Particle size, distribution, core-shell structures | CoFe/Fe₃O₄ core-shell: ~15nm core, ~2nm shell thickness | [36] |

| XPS | Surface composition, oxidation states | Fe oxidation state changes under reaction conditions in NiFe/Al₂O₃ | [34] |

| NH₃/CO₂-TPD | Acidity/basicity strength and distribution | Silica-aluminas with tunable Brønsted/Lewis acid sites | [37] |

Advanced Support Architectures for Bimetallic Catalysts

Core-Shell Structures for Enhanced Stability

Core-shell architectures represent advanced support designs that provide exceptional stability under demanding reaction conditions. The synthesis of CoFe/Fe₃O₄ core-shell structures involves thermal reduction of CoFe₂O₄ nanoparticles supported on layered g-C₃N₄ nanosheets at 450°C in a mixed gas atmosphere (25% H₂, 25% CO₂, 50% Ar) [36]. This process generates bimetallic CoFe alloy cores (~10 nm) surrounded by Fe₃O₄ shells (~2 nm) dispersed on defect-rich amorphous carbon. These structures exhibit remarkable performance in reverse water gas shift reactions with 30% CO₂ conversion, 99% CO selectivity, and no performance decay over 90 hours of continuous operation [36].

Computational-Experimental Screening Protocols

Integrating computational screening with experimental validation accelerates the discovery of optimal support-catalyst combinations. A high-throughput protocol using density functional theory (DFT) calculations screened 4350 bimetallic alloy structures based on similarity of their electronic density of states (DOS) patterns to reference catalysts like palladium [1]. The similarity metric ΔDOS₂₋₁ quantitatively compares DOS patterns near the Fermi energy, giving higher weight to this critical region. This computational screening identified eight promising candidates, four of which (Ni₆₁Pt₃₉, Au₅₁Pd₄₉, Pt₅₂Pd₄₈, and Pd₅₂Ni₄₈) demonstrated catalytic properties comparable to Pd when experimentally tested for H₂O₂ direct synthesis [1]. Notably, the Pd-free Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ catalyst exhibited a 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity compared to prototypical Pd catalysts [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Supported Catalyst Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| γ-Alumina (γ-Al₂O₃) | High-surface-area support | CO₂ methanation, methane partial oxidation | Thermal stability to 700°C; acid-base bifunctionality |

| Tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) | Silica source; binding agent | Sol-gel synthesis of mixed oxides | Hydrolysis rate control critical for homogeneous distribution |

| Pluronic P123/PF127 | Structure-directing agent | Mesoporous alumina synthesis | Template removal at 400-500°C |

| Aluminum isopropoxide | Alumina precursor | Sol-gel catalyst preparation | Controls hydrolysis kinetics and pore structure |

| Metal nitrate salts | Metal oxide precursors | Incorporation of Fe, Ni, Co, Cu | Decomposition temperature affects metal dispersion |

| Sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) | Sulfating agent | Superacid catalyst preparation | Concentration controls sulfate loading and acid strength |