Ensuring Reproducibility in High-Throughput Screening: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Validation Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive guide to reproducibility assessment in high-throughput screening (HTS) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Ensuring Reproducibility in High-Throughput Screening: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Validation Strategies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to reproducibility assessment in high-throughput screening (HTS) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It addresses four critical needs: understanding the fundamental importance and challenges of HTS reproducibility; implementing advanced methodological frameworks and computational tools; identifying and troubleshooting common sources of variability; and establishing rigorous validation protocols for cross-study comparisons. Drawing on current literature and best practices, we synthesize practical strategies to enhance data quality, reduce irreproducibility costs, and build confidence in screening results throughout the drug discovery pipeline.

The Reproducibility Crisis in HTS: Understanding Core Concepts and Critical Challenges

Defining Reproducibility in High-Throughput Contexts

In modern biological and biomedical research, high-throughput technologies are an essential part of the discovery process, enabling the rapid testing of hundreds of thousands to millions of biological or chemical entities [1] [2]. However, outputs from these experiments are often noisy due to numerous sources of variation in experimental and analytic pipelines, making reproducibility assessment a critical concern for establishing confidence in measurements and evaluating workflow performance [3]. The reproducibility of research is of significant concern for researchers, policy makers, clinical practitioners, and the public, with recent high-profile disputes highlighting issues with reliability and verifiability across scientific disciplines including biomedical sciences [4]. In high-throughput screening (HTS) specifically, the use of large quantities of biological reagents, extensive compound libraries, and expensive equipment makes the evaluation of reproducibility essential before embarking on full HTS campaigns due to the substantial resources required [2].

Defining Reproducibility in High-Throughput Environments

Key Concepts and Terminology

In the context of high-throughput research, reproducibility must be precisely defined and distinguished from related concepts:

- Empirical Reproducibility: There is enough information available to re-run the experiment exactly as it was originally conducted [4].

- Computational Reproducibility: The ability to calculate quantitative scientific results by independent scientists using the original datasets and methods [4].

- Replicability: The ability to obtain consistent results across studies investigating the same scientific question, each with their own data and methods.

The fundamental challenge in high-throughput contexts arises from the complex intersection of several factors: the emergence of larger data resources, greater reliance on research computing and software, and increasing methodological complexity that combines multiple data resources and tools [4]. This landscape complicates the execution and traceability of reproducible research while simultaneously demonstrating the critical need for accessible and transparent science.

Special Challenges in High-Throughput Data

High-throughput experiments present unique challenges for reproducibility assessment. The outcomes often contain substantial missing observations due to signals falling below detection levels [3]. For example, most single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) protocols experience high levels of dropout, where a gene is observed at low or moderate expression in one cell but not detected in another cell of the same type, leading to a majority of reported expression levels being zero [3]. These dropouts occur due to the low amounts of mRNA in individual cells, inefficient mRNA capture, and the stochastic nature of gene expression [3]. When a large number of measurements are missing, standard reproducibility assessments that exclude these missing values can generate misleading conclusions, as missing data contain valuable information about reproducibility [3].

Frameworks and Methods for Assessing Reproducibility

Statistical Methodologies

Several specialized statistical approaches have been developed to address the unique challenges of reproducibility assessment in high-throughput contexts:

Correspondence Curve Regression (CCR): A cumulative link regression model that assesses how covariates affect the reproducibility of high-throughput experiments by modeling the probability that a candidate consistently passes selection thresholds in different replicates [3]. CCR evaluates this probability at a series of rank-based selection thresholds, allowing effects on reproducibility to be assessed concisely and interpretably through regression coefficients. Recent extensions incorporate missing values through latent variable approaches, providing more accurate assessments when significant data are missing due to under-detection [3].

Extended CCR for Missing Data: This approach uses a latent variable framework to incorporate candidates with unobserved measurements, properly accounting for missing data when assessing the impact of operational factors on reproducibility [3]. Simulation studies demonstrate this method is more accurate in detecting reproducibility differences than existing measures that exclude missing values [3].

Reproducibility Indexes for HTS Validation: Various statistical indexes have been adapted from generic medical diagnostic screening strategies or developed specifically for HTS to evaluate process reproducibility and the ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds in vast sample collections [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Reproducibility Assessment Methods

| Method | Primary Approach | Handles Missing Data | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correspondence Curve Regression (CCR) | Models probability of consistent candidate selection across thresholds | No (standard version) | General high-throughput experiments |

| Extended CCR with Latent Variables | Incorporates missing data through latent variable approach | Yes | High-throughput experiments with significant missing data |

| Spearman/Pearson Correlation | Measures correlation between scores on replicate samples | No (requires complete cases) | General high-throughput experiments |

| RepeAT Framework | Comprehensive assessment across research lifecycle | Not specified | Biomedical secondary data analysis using EHR |

Comprehensive Assessment Frameworks

The RepeAT (Repeatability Assessment Tool) framework operationalizes key concepts of research transparency specifically for secondary biomedical data research using electronic health record data [4]. Developed through a multi-phase process that involved coding recommendations and best practices from publications across biomedical and statistical sciences, RepeAT includes 119 unique variables grouped into five categories:

- Research design and aim

- Database and data collection methods

- Data mining and data cleaning

- Data analysis

- Data sharing and documentation [4]

This framework emphasizes that practices for true reproducibility must extend beyond the methods section of a journal article to include the full spectrum of the research lifecycle: analytic code, scientific workflows, computational infrastructure, supporting documentation, research protocols, metadata, and more [4].

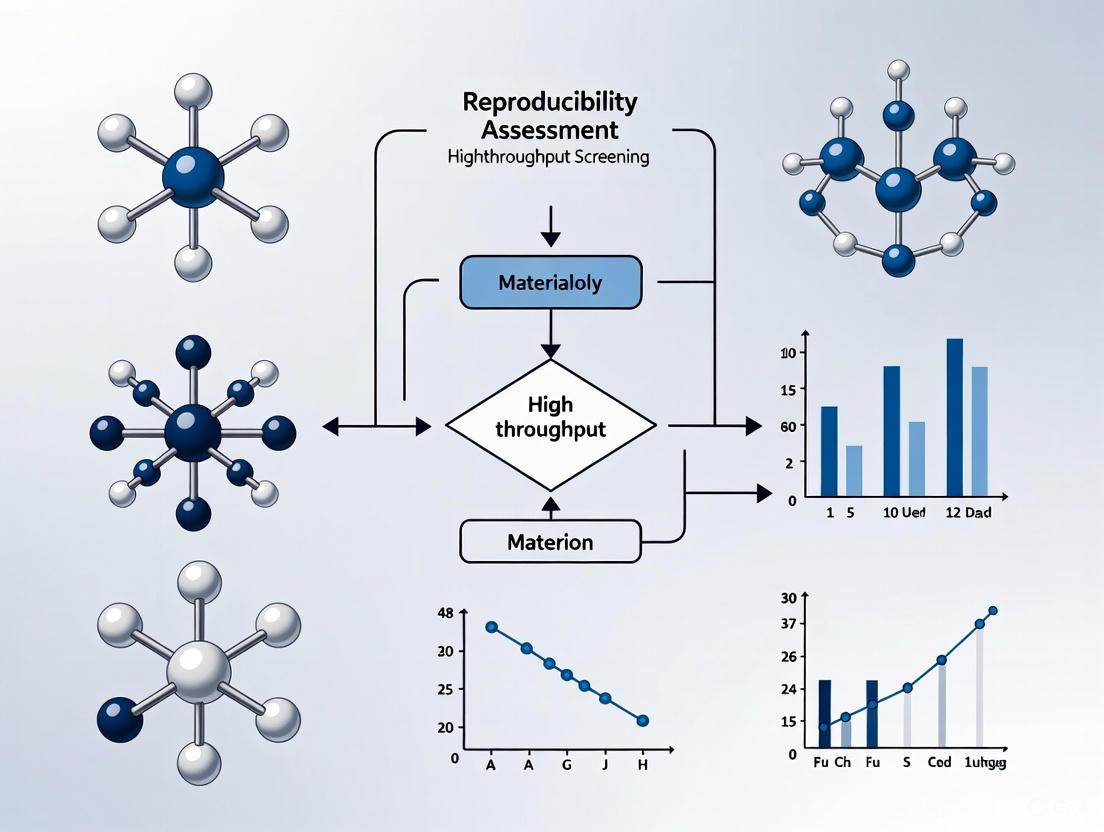

Diagram 1: High-Throughput Research Workflow with Reproducibility Assessment

Experimental Protocols for Reproducibility Assessment

Protocol 1: Assessing Reproducibility with Missing Data Using Extended CCR

Objective: To evaluate how the reproducibility of high-throughput experiments is affected by operational factors (e.g., platform, sequencing depth) when a large number of measurements are missing.

Methodology Summary (adapted from PMC9039958) [3]:

- Input Data Preparation: Collect significance scores for n candidates from two replicate samples generated by workflow s. Include all observations, noting missing values resulting from under-detection.

- Model Specification: Using a latent variable approach, model the probability that a candidate passes specific threshold t on both replicates: Ψ(t) = P(Y1 ≤ F1^(-1)(t), Y2 ≤ F2^(-1)(t)).

- Parameter Estimation: Estimate model parameters using appropriate statistical estimation techniques for latent variable models.

- Interpretation: Evaluate regression coefficients to quantify how operational factors affect reproducibility across different significance thresholds.

Key Advantages: This method properly accounts for missing data that typically contain valuable information about reproducibility, providing more accurate assessments than approaches limited to complete cases.

Protocol 2: HTS Process Validation and Screen Reproducibility

Objective: To validate the HTS process before full implementation and statistically evaluate screen reproducibility and the ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds.

Methodology Summary (adapted from ScienceDirect) [2]:

- HTS Workflow Optimization: Optimize and validate the HTS workflow as a quality process, addressing potential issues related to reproducibility and result quality before full implementation.

- Statistical Evaluation: Apply specialized reproducibility indexes adapted from medical diagnostic screening strategies or developed specifically for HTS.

- Implementation Case Studies: Implement validation tools across multiple case studies to demonstrate practical application.

- Decision Point: Use reproducibility assessments to determine whether the HTS process meets quality thresholds for full implementation.

Applications: This approach has been implemented in pharmaceutical industry settings (e.g., GlaxoSmithKline) to validate HTS processes before costly full-scale campaigns [2].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTS Reproducibility

| Reagent/Instrument | Function in HTS Reproducibility | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| Multimode Microplate Reader | Detection for UV-Vis absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence in 6- to 384-well formats | Agilent BioTek Synergy HTX [5] |

| Automated Workstations | Liquid handling precision and processing speed with minimal manual intervention | Tecan Freedom EVO with Dual Liquid Handling Arms [5] |

| Assay Analysis Software | Data management, analysis, and standardization across screening campaigns | Genedata Screener [5] |

| Specialized Microplates | Treated surfaces for immunological assays (ELISA, RIA, FIA) in 96-, 384-, 1536-well formats | BRANDplates Immunology Microplates [5] |

| Universal Kinase Assays | HTS kinase screening with reduced false hits and robust performance metrics | Kinase Glo Assay [5] |

Benchmarking and Comparative Evaluation

Benchmarking Frameworks for Computational Methods

The SummarizedBenchmark framework provides a structured approach for designing, executing, and evaluating benchmark comparisons of computational methods used in high-throughput data analysis [6]. This R package implements a grammar for benchmarking that integrates both design and execution, tracking important metadata such as software versions and parameters that are crucial for reproducibility as methods continually evolve [6].

Key Features:

- BenchDesign Object: Stores methods to be benchmarked and optional datasets without immediate execution.

- Parallel Execution: Implements parallel processing for efficient method evaluation.

- Error Handling: Prevents single method failures from terminating entire benchmarking processes.

- Performance Metrics: Provides functions to evaluate and visualize method performance using relevant metrics [6].

Diagram 2: Benchmarking Process for Method Comparison

Case Study: scRNA-seq Platform Comparison

A practical application of reproducibility assessment demonstrates how different approaches can lead to varying conclusions:

Experimental Context: Comparison of single-cell RNA-seq libraries prepared using TransPlex Kit and SMARTer Ultra Low RNA Kit on HCT116 cells [3].

Contrasting Results:

- When transcripts with zero counts were included (24,933 transcripts), Spearman correlation was lower for TransPlex (0.648) than for SMARTer (0.734).

- When only transcripts expressed in both cells were included, the pattern reversed (TransPlex: 0.501 for 8,859 non-zero transcripts vs. SMARTer: 0.460 for 6,292 non-zero transcripts) [3].

- Using Pearson correlation instead of Spearman suggested TransPlex was more reproducible regardless of zero inclusion [3].

Interpretation: This case highlights how excluding missing values (zeros) versus including them, along with choice of correlation metric, can substantially impact conclusions about platform reproducibility, emphasizing the need for principled approaches that properly account for missing data.

Defining and assessing reproducibility in high-throughput contexts requires specialized statistical methods and comprehensive frameworks that address the unique challenges of these data-rich environments. Approaches such as correspondence curve regression with missing data capabilities, structured assessment tools like RepeAT, and benchmarking frameworks like SummarizedBenchmark provide principled methodologies for evaluating reproducibility amid the complexities of high-throughput data. As the field continues to evolve with larger data resources and more complex methodologies, robust reproducibility assessment will remain crucial for ensuring the reliability and verifiability of high-throughput research outcomes with significant implications for drug discovery and biomedical science.

Reproducibility is a fundamental principle of the scientific method, serving as the cornerstone for validating findings and building cumulative knowledge. However, in the realm of high-throughput screening (HTS) and preclinical research, this principle faces significant challenges. The inability to reproduce research findings has evolved from an academic concern to a critical problem with profound scientific and economic implications [7]. Estimates indicate that more than 50% of preclinical research is irreproducible, creating a domino effect that misdirects research trajectories, delays therapeutic development, and wastes substantial resources [7] [8]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the stakes and implementing solutions for irreproducibility is no longer optional—it is an economic and ethical imperative. This guide examines the multifaceted impacts of irreproducible screening and objectively compares approaches to enhance reproducibility, providing actionable methodologies and frameworks for the research community.

The Economic Burden of Irreproducibility

Quantifying the Direct and Indirect Costs

The financial impact of irreproducible research extends far beyond wasted experiment costs, affecting the entire drug development pipeline. A seminal analysis by Freedman et al. estimated that the cumulative prevalence of irreproducible preclinical research exceeds 50%, resulting in approximately $28 billion spent annually in the United States alone on preclinical research that cannot be replicated [7] [9]. This staggering figure represents nearly half of the estimated $56.4 billion spent annually on preclinical research in the U.S. [7].

Table 1: Economic Impact of Irreproducible Preclinical Research

| Cost Category | Estimated Financial Impact | Scope/Context |

|---|---|---|

| Direct costs of irreproducible preclinical research | $28 billion annually | U.S. alone [7] |

| Pharmaceutical industry replication studies | $500,000 - $2,000,000 per study | Requires 3-24 months per study [7] |

| Potential savings through open practices | Up to $1.4 billion annually | Across preclinical research [9] |

| Indirect "house of cards" effects | $13.5 - $270 billion yearly | Future work built on incorrect findings [9] |

The downstream impacts are equally concerning. When academic research with potential clinical applications is identified, pharmaceutical companies typically conduct replication studies before beginning clinical trials. Each of these replication efforts requires 3-24 months and between $500,000-$2,000,000 in investment [7]. These figures represent only the direct replication costs and do not account for the opportunity costs of pursuing false leads or the delayed availability of effective treatments.

Beyond these direct costs, indirect effects create what has been termed a "house of cards" phenomenon, where future research builds upon incorrect findings. One analysis suggests these indirect costs could inflate the total economic impact to between $13.5 billion and $270 billion annually [9]. Historical cases like high-dose chemotherapy plus bone marrow transplants (HDC/ABMT) for breast cancer in the 1980s and 90s underscore this problem. Initial speculative studies led to $1.75 billion in flawed trials and 35,000 failed treatments at a minimum $60 million cost, despite early critiques of the data [9].

Broader Scientific and Societal Costs

The economic consequences represent only one dimension of the problem. Irreproducible research creates significant scientific and societal costs:

- Misguided research directions: False findings misdirect research resources and intellectual capital toward dead ends [9].

- Therapeutic development delays: Each false lead delays the discovery and development of genuinely effective treatments [7].

- Erosion of public trust: As irreproducible findings are publicized and later debunked, public confidence in scientific research diminishes [8].

- Patient risk and harm: Irreproducible preclinical studies that progress to human trials potentially endanger patients who participate in studies based on spurious research [9].

Root Causes: Why Screening Research Fails to Reproduce

Categories of Irreproducibility

Analysis of irreproducibility in preclinical research reveals that errors fall into four primary categories, each contributing significantly to the overall problem [7]:

Table 2: Primary Categories of Irreproducibility in Preclinical Research

| Category | Primary Issues | Contribution to Irreproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Inadequate blinding, improper randomization, insufficient sample size, failure to control for biases | 10-30% of irreproducible studies [7] |

| Biological Reagents and Reference Materials | Misidentified cell lines, cross-contamination, over-passaging, improper authentication | 15-40% of irreproducible studies [7] |

| Laboratory Protocols | Insufficient methodological detail, protocol modifications, lack of standardization | 15-30% of irreproducible studies [7] |

| Data Analysis and Reporting | Inappropriate statistical analysis, selective reporting, lack of access to raw data | 25-60% of irreproducible studies [7] |

The cumulative impact of these categories results in an estimated irreproducibility rate between 18% and 88.5%, with a natural point estimate of 53.3% [7]. This analysis employed a conservative probability bounds approach to account for uncertainties in the data.

Systemic and Cognitive Factors

Beyond technical errors, several systemic and cognitive factors exacerbate the reproducibility problem:

- Competitive academic culture: The research reward system emphasizes novel findings over replication studies and negative results [8]. University hiring and promotion criteria often prioritize high-impact publications, which rarely include replication studies or null results [8].

- Cognitive biases: Confirmation bias (interpreting evidence to confirm existing beliefs), selection bias (non-random sampling), and reporting bias (suppressing negative results) subconsciously influence research practices [8].

- Inadequate training: Many researchers lack sufficient training in experimental design, statistical methods, and data management, particularly as technologies generate increasingly complex datasets [8].

- Insufficient methodological detail: Published methods sections often lack the comprehensive details necessary for other researchers to exactly replicate experiments [8].

Root Causes of Irreproducibility

Assessing Reproducibility: Frameworks and Definitions

Defining Reproducibility

The term "reproducibility" encompasses several distinct concepts. The American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB) has proposed a multi-tiered framework for defining reproducibility [8]:

- Direct replication: Efforts to reproduce a previously observed result using the same experimental design and conditions as the original study.

- Analytic replication: Reproducing a series of scientific findings through reanalysis of the original dataset.

- Systemic replication: Attempting to reproduce a published finding under different experimental conditions (e.g., in a different culture system or animal model).

- Conceptual replication: Evaluating the validity of a phenomenon using a different set of experimental conditions or methods.

For this guide, we adopt an inclusive definition of irreproducibility that encompasses the existence and propagation of one or more errors, flaws, inadequacies, or omissions that prevent replication of results [7]. It is important to note that perfect reproducibility across all research is neither possible nor desirable, as attempting to achieve it would dramatically increase costs and reduce the volume of research conducted [7].

Data Reproducibility: A Critical Dimension

A recent replication study using electronic health record (EHR) data proposed "data reproducibility" as a fourth aspect of replication, distinct from methods, results, and inferential reproducibility [10]. Data reproducibility concerns the ability to prepare, extract, and clean data from a different database for a replication study [10]. This concept has particular relevance for HTS, where data complexity and preprocessing significantly impact outcomes.

The challenge of data reproducibility was highlighted in a replication study attempting to reproduce a study examining hospitalization risk following COVID-19 in individuals with diabetes [10]. Despite having the same data engineers and analysts working with the original code, differences in data sources and environments created significant barriers to reproducibility [10].

Solutions and Best Practices for Enhanced Reproducibility

Community-Developed Standards and Best Practices

Addressing the reproducibility crisis requires systematic implementation of best practices and standards across the research lifecycle. Drawing parallels from other industries, such as the information and communication technology sector where standard development organizations like the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) successfully established universal standards, the life sciences must engage all stakeholders in dynamic, collaborative efforts to standardize common scientific processes [7].

Table 3: Best Practices for Improving Reproducibility in Screening Research

| Practice Category | Specific Recommendations | Expected Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Data & Material Sharing | Share all raw data, protocols, and key research materials via public repositories; use authenticated, low-passage biological materials | Reduces reinvention; enables validation; improves biological consistency [8] |

| Experimental Design | Implement blinding; ensure proper randomization; calculate statistical power; pre-register studies | Reduces biases; improves robustness; discourages suppression of negative results [8] |

| Methodological Reporting | Provide thorough methodological details; report negative results; document all experimental parameters | Enables direct replication; provides context for failures [8] |

| Statistical Training | Educate researchers on proper statistical methods; implement robust data preprocessing; use appropriate hit-detection methods | Reduces analytical errors; improves data interpretation [11] |

| Validation Metrics | Implement rigorous assay validation; use Z'-factor (target: 0.5-1.0); calculate signal-to-noise; assess coefficient of variation | Ensures assay robustness; improves screening accuracy [2] [12] |

Multifidelity Approaches in High-Throughput Screening

A promising development in HTS is the adoption of multifidelity screening approaches that leverage multiple data modalities present in real-world HTS projects [13]. Traditional HTS follows a multitiered approach consisting of successive screens of drastically varying size and fidelity: a low-fidelity primary screen (up to 2 million molecules in industrial settings) followed by a high-fidelity confirmatory screen (up to 10,000 compounds) [13].

The MF-PCBA (Multifidelity PubChem BioAssay) dataset represents an important innovation in this space—a curated collection of 60 datasets that includes two data modalities for each dataset, corresponding to primary and confirmatory screening [13]. This approach more accurately reflects real-world HTS conventions and presents new opportunities for machine learning models to integrate low- and high-fidelity measurements through molecular representation learning [13]. By leveraging all available HTS data modalities, researchers can potentially improve drug potency predictions, guide experimental design more effectively, save costs associated with multiple expensive experiments, and ultimately enhance the identification of new drugs [13].

HTS Multifidelity Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Reproducible Screening

Protocol 1: HTS Process Validation and Reproducibility Assessment

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) has developed a comprehensive approach to validate the HTS process before embarking on full HTS campaigns [2]. This protocol addresses two critical aspects: (1) optimization and validation of the HTS workflow as a quality process, and (2) statistical evaluation of the HTS, focusing on the reproducibility of results and the ability to distinguish active from nonactive compounds [2].

Key Steps:

- Assay Optimization: Systematically optimize assay conditions using design of experiments (DoE) approaches to identify critical factors and their optimal ranges.

- Robustness Testing: Evaluate assay performance under slightly modified conditions (e.g., reagent incubation times, temperature variations) to establish operational boundaries.

- Reproducibility Assessment: Conduct intra-plate, inter-plate, and inter-day reproducibility studies using statistical measures including Z'-factor, signal-to-noise ratio, and coefficient of variation.

- Implementation of Reproducibility Indexes: Adapt and apply statistical indexes from medical diagnostic screening strategies to quantify HTS reproducibility [2].

Protocol 2: Improved Hit Detection Through Experimental Design and Statistical Methods

Identification of active compounds in HTS can be substantially improved by applying classical experimental design and statistical inference principles [11]. This protocol maximizes true-positive rates without increasing false-positive rates through a multi-step analytical process:

Methodology:

- Robust Data Preprocessing: Apply trimmed-mean polish methods to remove row, column, and plate biases from HTS data [11].

- Replicate Measurements: Incorporate replicate measurements to estimate the magnitude of random error and enable formal statistical modeling.

- Statistical Modeling: Use formal statistical models (e.g., RVM t-test) to benchmark putative hits relative to what is expected by chance [11].

- Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Analysis: Evaluate hit detection performance using ROC analysis, which has demonstrated superior power for data preprocessed by trimmed-mean polish methods combined with the RVM t-test, particularly for small- to moderate-sized biological hits [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Reproducible Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function | Reproducibility Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Authenticated Cell Lines | Provide consistent biological context for screening | Use low-passage, regularly authenticated stocks to prevent genotypic and phenotypic drift [8] |

| Characterized Chemical Libraries | Source of compounds for screening | Well-annotated libraries reduce false positives from PAINS (pan-assay interference compounds) [12] |

| Validated Assay Kits | Enable standardized measurement of biological activities | Use kits with established Z'-factors (0.5-1.0 indicates excellent assay) [12] |

| Reference Standards | Serve as positive/negative controls for assay performance | Include in every experiment to monitor assay stability over time [8] |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor technical performance of instruments and protocols | Regular QC checks identify technical variations before they affect experimental outcomes [2] |

The scientific and economic impacts of irreproducible screening research represent a critical challenge for the research community. With an estimated $28 billion annually spent on irreproducible preclinical research in the U.S. alone, and the potential for even greater costs through misdirected research and delayed therapies, addressing this problem requires concerted effort across multiple fronts [7]. The solutions—including robust data sharing, improved experimental design, standardized protocols, and multifidelity approaches—require cultural shifts in how research is conducted, evaluated, and published.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, implementing the frameworks and best practices outlined in this guide offers a path toward more efficient, reliable, and impactful screening research. By embracing these approaches, the scientific community can enhance the reproducibility of screening efforts, accelerate therapeutic development, and ensure that limited research resources are deployed as effectively as possible. The stakes are indeed high, but with systematic attention to reproducibility, the research community can turn this challenge into an opportunity for scientific advancement.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) has become a cornerstone technology in modern drug discovery and biomedical research, enabling the rapid testing of thousands to millions of compounds against biological targets [14]. However, the massive scale and complexity of HTS workflows introduce numerous potential sources of variability that can compromise data quality and experimental reproducibility. Understanding and controlling these variability sources is crucial for researchers seeking to generate reliable, reproducible data that accelerates the path from concept to candidate. This guide examines the common sources of variability in HTS workflows and provides frameworks for their quantification and control, with direct implications for reproducibility assessment in high-throughput screening research.

Liquid Handling and Automation

Robotic liquid handlers are fundamental to HTS operations, but they represent a significant source of technical variability. Pipetting errors, whether due to calibration drift, tip wear, or fluidic system inconsistencies, can lead to false positives or negatives, ultimately wasting resources [14]. This variability is particularly problematic in miniaturized assay formats (384- or 1536-well plates) where volumetric errors are magnified. The consistency of hardware calibration directly impacts overall system reliability, making regular maintenance and validation essential.

Sample Processing and Reagent Variation

The method of sample processing introduces another layer of variability. As demonstrated in virome detection studies, the RNA extraction protocol itself—specifically whether it includes acidic phenol phase separations and precipitation—can determine pathogen detection sensitivity [15]. This highlights how seemingly minor methodological choices can significantly impact results. Additionally, reagent lot variations, preparation inconsistencies, and stability issues contribute to inter-assay variability that must be controlled through careful standardization.

Detection Instrumentation and Signal Acquisition

Microplate readers and other detection systems exhibit performance variations that affect data quality. Differences in optical path length, detector sensitivity, and calibration can introduce systematic biases between instruments or even across different areas of the same plate. Environmental factors such as temperature fluctuations and evaporation during extended run times further compound these technical variations, particularly in sensitive enzymatic or binding assays.

Biological and Analytical Variability

Reproducibility Assessment Frameworks

The INTRIGUE (quantIfy and coNTRol reproducIbility in hiGh-throUghput Experiments) computational framework provides a robust methodology for evaluating reproducibility in high-throughput experiments [16]. This approach introduces the concept of directional consistency (DC), which emphasizes that reproducible signals should maintain consistent effect directions (positive or negative) across repeated measurements.

The framework classifies experimental units into three distinct categories:

- Null signals: Consistent zero effects across all experiments

- Reproducible signals: Consistent non-zero effects across all experiments

- Irreproducible signals: Effect size heterogeneity exceeding DC criteria [16]

This classification enables researchers to calculate informative metrics such as πNull (proportion of null signals), πR (proportion of reproducible signals), πIR (proportion of irreproducible signals), and ρIR (relative proportion of irreproducible findings in non-null signals) [16].

Sensitivity and Limit of Detection

The sensitivity of HTS assays and their limits of detection are profoundly influenced by multiple factors, including pathogen concentration (in the case of pathogen detection), sample processing method, and sequencing depth [15]. Time-course experiments comparing HTS to RT-PCR assays have demonstrated that HTS detection can be equivalent to or more sensitive than established molecular methods, but this sensitivity depends on controlling these variability sources [15].

Quantitative Assessment of HTS Reproducibility

Table 1: Key Metrics for Quantifying Reproducibility in High-Throughput Experiments

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| πNull | Proportion of null signals | Measures prevalence of true negative findings | Estimated via empirical Bayes procedure [16] |

| πR | Proportion of reproducible signals | Indicates rate of consistently detected true effects | Estimated via EM algorithm [16] |

| πIR | Proportion of irreproducible signals | Quantifies rate of inconsistent findings | πIR = 1 - πNull - πR [16] |

| ρIR | Relative proportion of irreproducible non-null signals | Measures severity of reproducibility issues | ρIR = πIR / (πIR + πR) [16] |

| Directional Consistency (DC) | Probability that underlying effects have same sign | Fundamental criterion for reproducible signals | Adaptive to underlying effect size [16] |

Table 2: Comparison of HTS vs. RT-PCR Detection Sensitivity in Time-Course Experiment

| Time Point | HTS Detection (de novo assembly) | HTS Detection (read mapping) | RT-PCR Detection | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time point 0 | No viruses or viroids detected | No viruses or viroids detected | No viruses or viroids detected | Baseline established [15] |

| Time point 1 (30 days) | CTV detected | CTV + CEVd (in 2 samples) | CTV detected | HTS showed additional sensitivity [15] |

| Later time points | Full virome profile | Full virome profile with >99% genome coverage | Full virome profile | Convergence of methods with pathogen accumulation [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Reproducibility Assessment

INTRIGUE Statistical Implementation

The INTRIGUE framework employs two Bayesian hierarchical models for reproducibility assessment:

- CEFN Model: Features adaptive expected heterogeneity where tolerable heterogeneity levels adjust based on underlying effect size

- META Model: Maintains invariant expected heterogeneity regardless of effect magnitude [16]

Both models utilize an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm that treats latent class status as missing data, enabling estimation of the proportions of null, reproducible, and irreproducible signals. The resulting posterior probabilities facilitate false discovery rate (FDR) control procedures to identify reproducible and irreproducible signals [16].

HTS Virome Detection Protocol

A comprehensive approach for assessing HTS reproducibility includes:

- Sample Preparation: Process biological replicates in triplicate using standardized extraction protocols (e.g., CTAB method)

- Sequencing: Illumina HTS generating approximately 25 million paired-end reads per sample

- Quality Control: Stringent quality trimming retaining >96% of data

- Assembly: De novo assembly using SPAdes generating ~74,000 scaffolds with N50 of ~1,831 nt

- Analysis: BLASTn analysis and read mapping to reference genomes with >99% genome coverage target

- Quantification: Transcripts per million (TPM) values to compare pathogen read proportions across samples [15]

Visualization of HTS Reproducibility Assessment

HTS Reproducibility Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function in HTS Workflow | Variability Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Robotic Liquid Handlers | Automated sample and reagent dispensing | Calibration drift, tip wear, and fluidic inconsistencies cause volumetric errors [14] |

| Microplate Readers | High-throughput signal detection | Optical path differences, detector sensitivity variations affect signal acquisition [14] |

| Standardized Assay Kits | Consistent reagent formulation | Lot-to-lot variation requires rigorous quality control and validation |

| CTAB Extraction Reagents | Nucleic acid isolation for sequencing | Protocol variations (e.g., phenol phase separation) affect detection sensitivity [15] |

| Reference Standards | Inter-assay normalization and QC | Essential for distinguishing technical from biological variation |

| Automation-Compatible Plates | Miniaturized reaction vessels | 384- or 1536-well formats maximize throughput but magnify volumetric errors [14] |

| Quality Control Libraries | Sequencing process validation | Standardized controls for assessing sequencing depth and detection limits [15] |

Addressing variability in HTS workflows requires a multifaceted approach encompassing both technical and analytical solutions. The integration of robust reproducibility assessment frameworks like INTRIGUE provides powerful tools for quantifying and controlling variability, while standardized experimental protocols help minimize technical noise. As HTS technologies continue to evolve toward greater automation and miniaturization, maintaining awareness of these variability sources and implementing rigorous quality control measures will be essential for generating biologically meaningful, reproducible results. The future of HTS reproducibility will likely involve even tighter integration of automated workflows with computational quality control frameworks, enabling real-time monitoring and correction of variability sources throughout the screening process.

In high-throughput screening research, the pervasive challenge of missing data—termed dropouts or underdetection—directly threatens the validity and reproducibility of scientific findings. Modern biological and biomedical research relies heavily on high-throughput technologies, yet their outputs are notoriously noisy due to numerous sources of variation in experimental and analytic workflows [3]. The reproducibility of outcomes across replicated experiments provides crucial information for establishing confidence in measurements and evaluating workflow performance [3]. However, when a substantial proportion of data is missing, conventional reproducibility assessments can yield misleading conclusions, potentially undermining downstream analysis and drug development decisions.

This challenge is particularly acute in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) experiments, where technological limitations and biological stochasticity combine to create exceptionally sparse datasets. In a typical scRNA-seq gene-cell count matrix, >90% of elements are zeros [17]. While some zeros represent genuine biological absence of expression, many result from technical failures where expressed genes fall below detection limits—a phenomenon specifically problematic when comparing reproducibility across different experimental platforms [3]. The field lacks consensus on best practices for handling these missing observations, with different approaches sometimes yielding contradictory conclusions about which methods perform best [3].

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies

Methodological Approaches for Handling Missing Data

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Handling Missing Data in High-Throughput Experiments

| Method | Underlying Principle | Missing Data Mechanism | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete Case Analysis | Excludes subjects with any missing data | MCAR | Simple implementation; Unbiased if data MCAR | Reduced statistical power; Potentially biased if not MCAR [18] |

| Mean Imputation | Replaces missing values with variable mean | MCAR | Preserves sample size; Simple computation | Artificially reduces variance; Ignores multivariate relationships [18] |

| Correspondence Curve Regression (CCR) with Missing Data | Models reproducibility across rank thresholds incorporating missing values | MAR/MNAR | Specifically designed for reproducibility assessment; Accounts for missing data informatively | Complex implementation; Computational intensity [3] |

| Multiple Imputation (MICE) | Creates multiple complete datasets with plausible values | MAR | Accounts for imputation uncertainty; Preserves multivariate relationships | Computationally intensive; Complex implementation [18] |

| Retrieved Dropout Imputation | Uses off-treatment completers to inform imputation | MNAR | Aligns with treatment policy estimand; Clinically plausible assumption | Requires sufficient retrieved dropout sample [19] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Missing Data Methods Across Experimental Contexts

| Method | Reproducibility Accuracy | Computational Intensity | Bias Reduction | Recommended Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete Case Analysis | Variable (highly context-dependent) | Low | Poor for non-MCAR | Initial exploratory analysis only [18] |

| Standard CCR (excluding missing data) | Inaccurate with high missingness [3] | Medium | Poor with informative missingness | Low missingness scenarios (<5%) |

| Extended CCR (incorporating missing data) | High (accurate in simulations) [3] | High | Significant improvement | High-throughput experiments with >10% missingness [3] |

| Multiple Imputation (MICE) | Medium-High | High | Good under MAR | General clinical research with moderate missingness [18] |

| Retrieved Dropout Method | High for clinical trials | Medium | Good for MNAR scenarios | Clinical trials with treatment discontinuation [19] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Extended Correspondence Curve Regression Protocol

The extended Correspondence Curve Regression (CCR) methodology represents a significant advancement for assessing reproducibility in high-throughput experiments with substantial missing data. The protocol involves these critical steps:

Data Structure Setup: For each workflow ( s ) with operational factors ( xs ), consider significance scores ( (Y1^s, Y2^s) = {(y{11}^s, y{12}^s), (y{21}^s, y{22}^s), \ldots, (y{n1}^s, y{n2}^s)} ) from two replicates, where some ( y{ij}^s ) are missing [3].

Model Specification: The method models the probability that a candidate passes selection threshold ( t ) on both replicates:

( Ψ(t) = P(Y1 ≤ F1^{-1}(t), Y2 ≤ F2^{-1}(t)) ) [3]

where ( F1 ) and ( F2 ) are the marginal distributions of the significance scores on the two replicates.

Latent Variable Framework: Incorporating missing data through a latent variable approach that accounts for candidates with unobserved measurements, properly accounting for their contribution to reproducibility assessment [3].

Parameter Estimation: Using maximum likelihood estimation to fit the regression model that assesses how operational factors affect reproducibility across different significance thresholds.

Validation studies demonstrate that this approach more accurately detects reproducibility differences than conventional measures when missing data are prevalent [3]. In simulation studies, the extended CCR method correctly identified true differences in reproducibility with greater accuracy than methods that exclude missing observations.

Retrieved Dropout Imputation Protocol

For clinical research settings with participant discontinuation, the retrieved dropout method offers a pragmatic approach:

Population Definition: Identify retrieved dropouts (RDs)—subjects who remain in the study despite treatment discontinuation and have primary endpoint data available [19].

Dataset Segmentation: Partition the dataset into three subsets: subjects with missing primary visit data (( M )), retrieved dropouts (( R )), and on-treatment completers (( C )) [19].

Imputation Model Development: Develop regression models using RDs as the basis for imputation, including baseline characteristics and last on-treatment visit as predictors [19].

Multiple Imputation: Create a minimum of 100 imputed datasets to prevent power falloff for small effect sizes [19].

Analysis Pooling: Analyze each complete dataset using standard methods (e.g., ANCOVA) and pool results across imputations [19].

This approach aligns with the treatment policy estimand outlined in ICH E9(R1), incorporating data collected after the occurrence of intercurrent events like treatment discontinuation [19].

Visualization of Methodological Workflows

Figure 1: Workflow for Extended Correspondence Curve Regression with Missing Data Incorporation

Figure 2: Multiple Imputation Workflow for Handling Missing Data

Table 3: Essential Resources for Addressing Missing Data Challenges

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms | 10X Chromium, SMART-seq2, Drop-seq | Generate single-cell transcriptomic data | Experimental data generation with inherent missingness [17] |

| Statistical Software | R (mice package), SAS, Stata | Implement multiple imputation procedures | General missing data handling across research domains [18] |

| Specialized Reproducibility Tools | Custom CCR implementation, IDR, MaRR | Assess reproducibility incorporating missing data | High-throughput experiment quality control [3] |

| Data Visualization Platforms | ggplot2, ComplexHeatmaps, Seurat | Visualize missing data patterns and distributions | Exploratory data analysis and quality assessment |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Seurat, SCANPY, Monocle | Process high-dimensional data with inherent sparsity | Single-cell genomics analysis [17] |

The challenge of missing data in high-throughput screening research necessitates sophisticated methodological approaches that explicitly account for dropouts and underdetection. Traditional methods that exclude missing observations or employ simplistic imputation techniques produce biased reproducibility assessments, particularly in technologies like scRNA-seq where missingness exceeds 90% [17]. The extended Correspondence Curve Regression method represents a significant advancement by incorporating missing data through a latent variable framework, thereby providing more accurate assessments of how operational factors affect reproducibility [3].

For clinical research settings, the retrieved dropout method offers a principled approach for handling missing data not at random, aligning with treatment policy estimands while maintaining statistical robustness [19]. Multiple imputation continues to serve as a versatile tool, particularly when data are missing at random, though its implementation requires careful attention to model specification and the creation of sufficient imputed datasets [18].

As high-throughput technologies continue to evolve, generating increasingly complex and sparse datasets, the development and adoption of statistically rigorous methods for handling missing data will remain crucial for ensuring reproducible and translatable research findings. The methodologies compared in this guide provide researchers with evidence-based approaches for maintaining scientific validity despite the inevitable challenge of missing observations.

Advanced Methodologies and Computational Tools for Reproducibility Assessment

High-throughput screening (HTS) technologies are essential tools in modern biological research and drug discovery, enabling the simultaneous analysis of thousands of compounds, genes, or proteins for biological activity [20]. The reliability of these experiments hinges on the reproducibility of their outcomes across replicated experiments, which can be significantly influenced by variations in experimental and data-analytic procedures [21] [3]. Establishing robust statistical frameworks to quantify reproducibility is therefore critical for designing reliable HTS workflows and obtaining trustworthy results. Traditional methods for assessing reproducibility, such as Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients, often fail to provide a comprehensive picture, particularly when dealing with missing data or when reproducibility differs between strong and weak candidates [3]. This review focuses on the evolution, application, and comparative performance of correspondence curve regression (CCR) and related statistical frameworks, providing researchers with a structured analysis of methodologies for quantifying reproducibility in high-throughput experiments.

The pressing need for advanced reproducibility assessment is underscored by what many term a "reproducibility crisis" in life sciences. In stem-cell based research, for instance, studies frequently cannot be replicated due to issues like misidentified cell lines, protocol inaccuracies, and laboratory-specific quirks [22]. Similarly, in quantitative high-throughput screening (qHTS), parameter estimates from commonly used models like the Hill equation can show poor repeatability when experimental designs fail to establish proper asymptotes or when responses are heteroscedastic [23]. These challenges highlight the necessity for sophisticated statistical frameworks that can not only quantify reproducibility more accurately but also identify how operational factors influence it, thereby guiding the optimization of experimental workflows.

Methodological Foundations of Correspondence Curve Regression

Core Principles and Mathematical Formulation

Correspondence Curve Regression (CCR) is a cumulative link regression model specifically designed to assess how covariates affect the reproducibility of high-throughput experiments [3]. Unlike simple correlation measures that provide a single summary statistic, CCR evaluates reproducibility across a sequence of selection thresholds, which is crucial because top-ranked candidates are often the primary targets in downstream analyses. The fundamental quantity that CCR models is the probability that a candidate passes a specific rank-based threshold t on both replicates:

Ψ(t) = P(Y₁ ≤ F₁⁻¹(t), Y₂ ≤ F₂⁻¹(t)) [3]

In this equation, Y₁ and Y₂ represent the significance scores from two replicates, and F₁⁻¹(t) and F₂⁻¹(t) are the quantile functions of their respective distributions. By evaluating this probability across a series of thresholds t, CCR captures how consistency in candidate selection changes with statistical stringency. The model then incorporates operational factors as covariates to quantify their effects on reproducibility across the entire spectrum of candidate significance [3]. This approach provides a more comprehensive assessment than single-threshold methods, as it accounts for the fact that operational factors may differentially affect candidates of varying strengths.

Methodological Extensions for Enhanced Performance

Segmented Correspondence Curve Regression

A significant advancement in the CCR framework is the development of Segmented Correspondence Curve Regression (SCCR), which addresses the challenge that operational factors may exert differential effects on strong versus weak candidates [21] [24]. This heterogeneity complicates the selection of optimal parameter settings for HTS workflows. The segmented model incorporates a change point that dissects these varying effects, providing a principled approach to identify where in the significance spectrum the impact of operational factors changes. A grid search method is employed to identify the change point, and a sup-likelihood-ratio-type test is developed to test its existence [24]. Simulation studies demonstrate that this approach yields well-calibrated type I errors and achieves better model fitting than standard CCR, particularly when the effects of operational factors differ between high-signal and low-signal candidates [21].

CCR with Missing Data Integration

Another critical extension addresses the pervasive issue of missing data in high-throughput experiments. In technologies like single-cell RNA-seq, a majority of reported expression levels can be zero due to dropout events, creating challenges for reproducibility assessment [3]. Standard methods typically exclude these missing values, potentially generating misleading assessments. The extended CCR framework incorporates a latent variable approach to account for candidates with unobserved measurements, allowing missing data to be properly incorporated into reproducibility assessments [3]. This approach recognizes that missing values contain valuable information about reproducibility; for example, a candidate observed only in one replicate but not another indicates discordance that should contribute to irreproducibility measures. Simulations confirm that this method is more accurate in detecting true differences in reproducibility than approaches that exclude missing values [3].

Table 1: Key Methodological Variations of Correspondence Curve Regression

| Method | Core Innovation | Primary Application Context | Advantages Over Basic CCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard CCR | Models reproducibility across rank thresholds | General HTS with complete data | More comprehensive than single-threshold methods |

| Segmented CCR | Incorporates change points for heterogeneous effects | HTS where factors affect strong/weak candidates differently | Detects differential effects; better model fit |

| CCR with Missing Data | Latent variable approach for unobserved measurements | scRNA-seq, other assays with high dropout rates | Incorporates all available information; reduces bias |

Comparative Analysis of Reproducibility Assessment Frameworks

Statistical Frameworks for Reproducibility Quantification

While CCR and its variants offer powerful approaches for reproducibility assessment, they exist within a broader ecosystem of statistical methods designed to address similar challenges. The Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) method and Maximum Rank Reproducibility (MaRR) represent alternative approaches that also profile how consistently candidates are ranked and selected across replicate experiments [3]. These methods, like CCR, focus on the consistency of rankings across a sequence of thresholds rather than providing a single summary statistic. However, CCR distinguishes itself through its regression framework that directly quantifies how operational factors influence reproducibility, enabling more straightforward interpretation of covariate effects and facilitating workflow optimization.

Beyond reproducibility-specific methods, general statistical approaches for comparing nonlinear curves and surfaces offer complementary capabilities. These include nonparametric analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) [25], kernel-based methods [25], and spline-based comparative procedures [25]. While these methods are more general in scope, they share with CCR the fundamental challenge of determining whether functions derived from different experimental conditions are equivalent. Recent computational implementations have made these curve comparison techniques more accessible, with R packages and even Shiny applications now available for analysts who may not be statistical experts [25].

Performance Comparison Across Methodologies

Simulation studies provide critical insights into the relative performance of different reproducibility assessment frameworks. Segmented CCR demonstrates a well-calibrated type I error rate and substantially higher power in detecting and locating reproducibility differences across workflows compared to standard CCR [21] [24]. This power advantage is particularly pronounced when the effects of operational factors differ between strong and weak candidates, as the segmented model specifically accounts for this heterogeneity.

When dealing with missing data, the extended CCR framework that incorporates latent variables shows superior accuracy in detecting true reproducibility differences compared to approaches that exclude missing observations [3]. In practical applications to single-cell RNA-seq data, this approach has resolved contradictory conclusions that arose when different missing data handling methods were applied to the same dataset [3].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Reproducibility Assessment Methods

| Method | Type I Error Control | Power to Detect Differences | Handling of Missing Data | Ease of Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coefficients | Good | Moderate to low | Poor (usually excludes missing) | Excellent |

| Standard CCR | Good | Good | Poor (requires complete data) | Good |

| Segmented CCR | Good (well-calibrated) | Excellent | Poor (requires complete data) | Moderate |

| CCR with Missing Data | Good | Good for complete and missing data patterns | Excellent | Moderate |

| Nonparametric ANCOVA | Good with equal designs | Variable with different designs | Not specified | Good |

The comparison of nonlinear curves faces distinct challenges. Methods like nonparametric ANCOVA demonstrate good performance when comparison groups have similar design points, but power decreases substantially when explanatory variables take different values across groups [25]. Kernel-based methods offer greater flexibility but can be sensitive to bandwidth selection, while spline-based approaches provide a compromise between flexibility and stability [25].

Experimental Applications and Protocols

Case Study: Determining Cost-Effective Sequencing Depth in ChIP-seq

Segmented CCR has been successfully applied to address a fundamental design question in ChIP-seq experiments: How many reads should be sequenced to obtain reliable results in a cost-effective manner? [21] [24]. The experimental protocol for this application involves:

- Experimental Design: Multiple ChIP-seq experiments are conducted at varying sequencing depths, with replicates at each depth level.

- Data Processing: Sequencing reads are aligned to the reference genome, and significance scores (such as p-values or peak calls) are generated for genomic regions.

- Reproducibility Assessment: Segmented CCR is applied to model how sequencing depth affects reproducibility across different significance thresholds, specifically testing whether the effect of depth differs for strong versus weak binding sites.

- Change Point Detection: The algorithm identifies the significance threshold at which the effect of sequencing depth on reproducibility changes.

- Optimization: Results guide the selection of a sequencing depth that provides sufficient reproducibility for the study goals while minimizing costs.

Application of this protocol has revealed new insights into how sequencing depth impacts binding-site identification reproducibility, demonstrating that the effect of additional sequencing on reproducibility diminishes beyond certain thresholds, particularly for highly significant binding sites [21]. This allows researchers to determine the most cost-effective sequencing depth for their specific reproducibility requirements.

Case Study: Platform Comparison in Single-Cell RNA-seq

The CCR framework with missing data integration has been applied to evaluate different library preparation platforms in single-cell RNA-seq studies [3]. The experimental protocol includes:

- Sample Preparation: HCT116 cells are processed using different library preparation kits (e.g., TransPlex Kit and SMARTer Ultra Low RNA Kit).

- Data Collection: Gene expression measurements are obtained with multiple technical replicates for each platform.

- Missing Data Handling: The latent variable CCR approach incorporates both observed expression values and dropout events (zero counts) in reproducibility assessment.

- Model Fitting: CCR models are fit to quantify how the choice of platform affects reproducibility, properly accounting for the high proportion of missing observations typical in scRNA-seq data.

- Comparative Assessment: Reproducibility estimates from different platforms are compared to guide selection of the most reliable experimental system.

This application resolved contradictory conclusions that emerged when traditional correlation measures were applied with different missing data handling strategies [3]. Specifically, when only non-zero transcripts were considered, TransPlex showed higher Spearman correlation (0.501) than SMARTer (0.460), but the pattern reversed when zeros were included [3]. The CCR framework with proper missing data handling provided a principled resolution to this discrepancy.

Visualization of Method Workflows

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for selecting appropriate CCR variants based on data characteristics.

Diagram 2: Method evolution and comparative advantages of CCR frameworks over traditional approaches.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reproducibility Assessment

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in Reproducibility Research |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R packages for CCR and segmented CCR | Implement core reproducibility assessment algorithms |

| Data QC Tools | plateQC R package (NRFE metric) [26] | Detect systematic spatial artifacts in screening data |

| Cell Culture Systems | bit.bio's ioCells with opti-ox technology [22] | Provide consistent, defined human cell models |

| Library Prep Kits | TransPlex Kit, SMARTer Ultra Low RNA Kit [3] | Compare platform effects on technical reproducibility |

| Standard Reference Materials | ISO standardized protocols [22] | Establish baseline performance metrics |

| Experimental Design Tools | Custom scripts for sequencing depth simulation [21] | Optimize resource allocation for target reproducibility |

The plateQC R package represents a significant recent advancement in quality control for drug screening experiments [26]. This tool uses a normalized residual fit error (NRFE) metric to identify systematic spatial artifacts that conventional quality control methods based solely on plate controls often miss. Implementation studies demonstrate that NRFE-flagged experiments show three-fold lower reproducibility among technical replicates, and integrating NRFE with existing QC methods improved cross-dataset correlation from 0.66 to 0.76 in matched drug-cell line pairs from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer project [26].

For cell-based screening, technologies like bit.bio's ioCells with opti-ox deterministic programming provide highly consistent iPSC-derived human cells that address fundamental sources of variability in traditional differentiation methods [22]. These standardized cellular models, coupled with rigorous quality control processes that include immunocytochemistry, qPCR, and RNA sequencing verification, establish a more reliable foundation for reproducible screening experiments [22].

The evolution of correspondence curve regression and related statistical frameworks represents significant progress in addressing the complex challenge of reproducibility assessment in high-throughput screening. The standard CCR model advanced beyond simple correlation coefficients by evaluating reproducibility across multiple thresholds, while segmented CCR addressed the critical issue of heterogeneous effects across candidate strengths. The incorporation of missing data handling through latent variables further extended CCR's applicability to modern technologies like single-cell RNA-seq with high dropout rates.

Future methodology development will likely focus on integrating spatial artifact detection with reproducibility assessment [26], creating multi-dimensional frameworks that simultaneously address multiple sources of variability, and developing standardized reference materials and protocols that establish community-wide benchmarks [22]. As high-throughput technologies continue to evolve, with increasing scale and complexity, the parallel advancement of robust statistical frameworks for reproducibility assessment will remain essential for generating trustworthy scientific insights and accelerating drug discovery.

For practical implementation, researchers should select reproducibility assessment methods based on their specific data characteristics: standard CCR for complete data without heterogeneous effects, segmented CCR when operational factors differentially affect strong versus weak candidates, and CCR with missing data integration for experiments with substantial dropout events. Coupling these statistical approaches with robust quality control measures like the NRFE metric and standardized cellular models will provide the most comprehensive approach to ensuring reproducible high-throughput screening research.

Workflow Management Systems for Robust HTS Data Analysis

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) generates massive datasets critical for drug discovery, making robust workflow management systems (WMS) essential for ensuring data reproducibility and analytical consistency. This guide compares leading WMS solutions, evaluates their performance against reproducibility criteria, and provides experimental protocols for assessing system performance. With concerns about reproducibility affecting over 70% of researchers and documented inconsistencies in HTS data analysis, selecting appropriate informatics infrastructure has become paramount for reliable drug discovery pipelines. Our analysis identifies uap as the top-performing system meeting all defined reproducibility criteria, while other solutions offer specialized capabilities for different research environments and technical requirements.

High-Throughput Screening generates complex, multi-step data analyses particularly prone to reproducibility issues due to the multitude of available tools, parameters, and analytical decisions required [27]. The complexity of HTS data analysis creates a "reproducibility crisis" where less than one-third of published HTS-based genotyping studies provide sufficient information to reproduce the mapping step [27]. Workflow management systems address this challenge by providing structured environments that maintain analytical provenance, tool versioning, and parameter logging throughout complex analytical pipelines.

Comparative Analysis of HTS Workflow Management Systems

Evaluation Methodology

We established four minimal criteria for reproducible HTS data analysis based on published standards [27]:

- Dependency Management: Correct maintenance of dependencies between analysis steps and intermediate results

- Execution Control: Ensuring analysis steps successfully complete before subsequent steps execute

- Comprehensive Logging: Recording all tools, their versions, and complete parameter sets

- Code-Result Consistency: Maintaining consistency between analysis definition code and generated results

We evaluated systems across these criteria plus additional features including platform support, usability, and specialized HTS capabilities.

System Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of HTS Workflow Management Systems

| System | Reproducibility Features | Platform Support | HTS Specialization | Usability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| uap | ●●●●● | Cluster, Local | Optimized for omics data | YAML configuration |

| Galaxy | ●●●◐○ | Cloud, Server, Local | General purpose | Graphical interface |

| Snakemake | ●●●◐○ | Cluster, Cloud, Local | Flexible via programming | Domain-specific language |

| Nextflow | ●●●◐○ | Cluster, Cloud, Local | General bioinformatics | DSL with Java-like syntax |

| Bpipe | ●●◐○○ | Cluster, Local | General purpose | Simplified scripting |

| Ruffus | ●●◐○○ | Local | General purpose | Python library |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics in HTS Applications

| System | Analysis Consistency | Tool Version Logging | Error Recovery | Parallel Execution | Data Provenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| uap | Fully automated | Comprehensive | Built-in | Supported | Complete |

| Galaxy | User-dependent | Manual selection | Limited | Supported | Complete |

| Snakemake | Rule-based | Environment-dependent | Customizable | Extensive | Customizable |

| Nextflow | Container-based | Container-level | Robust | Extensive | Extensive |

| Bpipe | Stage-based | Partial | Basic | Basic | Basic |

| Ruffus | Python-dependent | Limited | Manual | Basic | Limited |

Key Differentiators and Selection Guidelines

uap uniquely satisfies all four minimal reproducibility criteria through its directed acyclic graph (DAG) architecture that tightly links analysis code with produced data [27]. The system is implemented in Python and uses YAML configuration files for complete analytical specification.

Galaxy provides the most accessible interface for non-programmers but offers less flexibility for customized HTS pipelines compared to code-based systems [27].

Snakemake and Nextflow balance reproducibility with flexibility through domain-specific languages that maintain readability while enabling complex pipeline definitions [27].

Specialized HTS systems like iRAP, RseqFlow, and MAP-RSeq implement specific analysis types but lack generalizability across different HTS applications [27].

Experimental Protocols for Reproducibility Assessment

Standardized HTS Data Analysis Workflow

Table 3: HTS Screening Stages and Replication Requirements

| Screening Phase | Replicates | Concentrations | Typical Sample Volume | Primary Quality Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot | 2-3 | 1 | 10³-10⁴ | Z-prime, CV |

| Primary | 1 | 1 | 10⁵-1.5×10⁶ | Hit rate, Z-prime |

| Confirmation (Replicates) | 2-4 | 1 | 10³-5×10⁴ | Reproducibility rate |

| Confirmation (Concentration) | 1 | 2-4 | 10³-5×10⁴ | Dose-response fit |

| Validation | 1-4 | 8-12 | 10³-5×10⁴ | IC₅₀, AUC precision |

Figure 1: Standardized HTS data analysis workflow with quality checkpoints.

Protocol: Cross-Platform Reproducibility Assessment

Objective: Quantify analytical reproducibility across different WMS platforms using standardized HTS datasets.

Materials:

- Reference HTS dataset with known positive/negative controls

- Multiple WMS installations (uap, Snakemake, Nextflow, Galaxy)

- Computational infrastructure with consistent specifications

Methodology:

- Data Distribution: Implement identical analytical workflows across all systems using a standardized RNA-seq dataset

- Process Execution: Run complete analyses from raw data to hit identification

- Result Collection: Capture all intermediate files, final results, and system metadata

- Comparison Analysis: Calculate concordance metrics between system outputs

Quality Control Measures:

- Implement normalized residual fit error (NRFE) to detect spatial artifacts [28]

- Apply traditional metrics (Z-prime, SSMD) for baseline quality assessment

- Compare coefficient of variation between technical replicates across systems

Protocol: Robustness to Analytical Variability

Objective: Evaluate system performance when introducing common analytical variations.

Methodology:

- Parameter Variation: Systematically alter key parameters (normalization method, hit threshold)

- Tool Substitution: Replace individual components with equivalent functionality

- Data Perturbation: Introduce controlled noise to input data

- Version Testing: Compare results across different tool versions

Assessment Metrics:

- Result concordance measured by Pearson correlation

- False positive/negative rates using known reference standards

- Computational efficiency and resource utilization

Advanced Quality Control: NRFE for Spatial Artifact Detection

Traditional quality control metrics like Z-prime and SSMD rely solely on control wells, failing to detect systematic spatial artifacts in drug-containing wells [28]. The Normalized Residual Fit Error (NRFE) metric addresses this limitation by evaluating plate quality directly from drug-treated wells.

Implementation Protocol:

- Calculate deviations between observed and fitted dose-response values

- Apply binomial scaling factor to account for response-dependent variance

- Establish quality thresholds: NRFE <10 (acceptable), 10-15 (borderline), >15 (unacceptable)

- Integrate with traditional metrics for comprehensive quality assessment

Experimental Validation: Analysis of 110,327 drug-cell line pairs demonstrated that plates with NRFE >15 exhibited 3-fold lower reproducibility in technical replicates [28]. Integration of NRFE with control-based methods improved cross-dataset correlation from 0.66 to 0.76 in matched drug-cell line pairs from GDSC project data [28].

Figure 2: Integrated quality control workflow combining traditional and spatial artifact detection.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for HTS Workflow Implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| uap WMS | Reproducible HTS data analysis pipeline management | Complete workflow control with dependency tracking [27] |

| PlateQC R Package | Spatial artifact detection in HTS plates | NRFE calculation and quality reporting [28] |

| I.DOT Liquid Handler | Automated non-contact dispensing | Minimizes variability in reagent distribution [29] |

| Cell-Based Assays | Physiologically relevant screening | 3D culture systems for improved predictive accuracy [30] |

| CRISPR Screening Systems | Genome-wide functional genomics | CIBER platform for extracellular vesicle studies [30] |

| AI/ML Integration Tools | Predictive compound triage | Hypergraph neural networks for target interaction prediction [31] |

Based on comprehensive evaluation against reproducibility criteria and experimental performance assessment:

For Maximum Reproducibility: uap provides the most robust solution meeting all minimal reproducibility criteria, making it ideal for regulated environments and cross-institutional collaborations where analytical provenance is critical [27].

For Flexible Pipeline Development: Snakemake and Nextflow offer the best balance of reproducibility and customization capability, suitable for research environments requiring frequent methodological innovation [27].

For Accessible Implementation: Galaxy remains the optimal choice for laboratories with limited programming expertise, though with potential compromises in flexibility for complex HTS applications [27].

Critical Implementation Consideration: Integration of advanced quality control measures like NRFE spatial artifact detection is essential regardless of platform selection, as traditional control-based metrics fail to detect significant sources of experimental error [28].

The increasing adoption of AI and machine learning in HTS, coupled with advanced workflow management systems, provides a pathway to address the reproducibility challenges that have historically plagued high-throughput screening data analysis. As HTS continues to evolve toward more complex 3D cell models and larger-scale genomic applications, robust informatics infrastructure will become increasingly critical for generating reliable, translatable drug discovery outcomes.

INTRIGUE and Other Computational Approaches for Directional Consistency