Closed-Loop Materials Discovery: The AI-Powered Automated Labs Revolutionizing Research

This article explores the paradigm shift in materials science and drug development driven by closed-loop discovery systems.

Closed-Loop Materials Discovery: The AI-Powered Automated Labs Revolutionizing Research

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm shift in materials science and drug development driven by closed-loop discovery systems. We examine the foundational technologies—from AI and robotics to FAIR data principles—that enable these self-driving laboratories. The content provides a methodological guide for implementing autonomous workflows, addresses key optimization and troubleshooting challenges, and validates the approach through comparative case studies demonstrating accelerated timelines from discovery to application. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource offers actionable insights for integrating automation into the research lifecycle.

The Core Technologies Powering Autonomous Materials Discovery

The process of materials discovery has traditionally been a slow, labor-intensive endeavor, characterized by manual experimentation, intuitive design, and lengthy cycles between synthesis and analysis. The closed-loop discovery paradigm represents a fundamental shift from this manual approach to an autonomous, intelligent, and accelerated research methodology. This paradigm integrates artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and high-throughput experimentation into a seamless workflow where each experiment informs the next in real-time, dramatically compressing the timeline from years to days. At its core, closed-loop discovery creates a self-driving laboratory where machine learning algorithms preside over decision-making processes, controlling robotic equipment for synthesis and characterization, and using experimental results to plan subsequent investigations autonomously [1]. This transformative approach is poised to revolutionize how scientists discover new materials for applications ranging from clean energy and electronics to pharmaceuticals and sustainable chemicals.

The significance of this paradigm is underscored by quantitative demonstrations of its efficiency. Recent benchmarks indicate that fully-automated closed-loop frameworks driven by sequential learning can accelerate materials discovery by 10-25x (representing a 90-95% reduction in design time) compared to traditional approaches [2]. Furthermore, specific implementations have achieved record-breaking results, such as the discovery of a catalyst material that delivered a 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar over pure palladium for fuel cells [3]. These advances are not merely about speed; they also substantially reduce resource consumption and waste generation, advancing more sustainable research practices [4].

Core Architecture of a Closed-Loop System

The architecture of a closed-loop discovery system represents a fundamental reengineering of the scientific method for autonomous operation. These systems integrate three critical components: AI-driven decision-making, robotic experimentation, and real-time characterization into a continuous, iterative workflow. The AI component serves as the "brain" of the operation, employing sophisticated machine learning models to select optimal experiments. The robotic systems function as the "hands," executing physical tasks such as materials synthesis and preparation. Finally, characterization instruments act as the "senses," measuring material properties and feeding data back to the AI system [3] [1].

This architectural framework operates through a tightly integrated cycle with four key phases:

- Design Phase: Machine learning models, typically based on Bayesian optimization or related active learning strategies, propose candidate materials or synthesis conditions predicted to advance specific research goals [5] [1].

- Make Phase: Robotic systems automatically synthesize proposed candidates using techniques such as combinatorial sputtering, flow chemistry, or automated liquid handling [6] [7] [4].

- Test Phase: High-throughput characterization systems rapidly measure desired properties, employing techniques including automated electrochemical testing, electron microscopy, or custom biochemical assays [6] [3].

- Learn Phase: Results are automatically analyzed and fed back to update the AI models, which then refine their understanding and design improved subsequent experiments [3] [1].

This create-measure-learn cycle continues autonomously, with each iteration enhancing the system's knowledge and focusing investigation on increasingly promising regions of the experimental space. The resulting system exemplifies a new era of robot science that enables science-over-the-network, reducing the economic impact of scientists being physically separated from their labs [1].

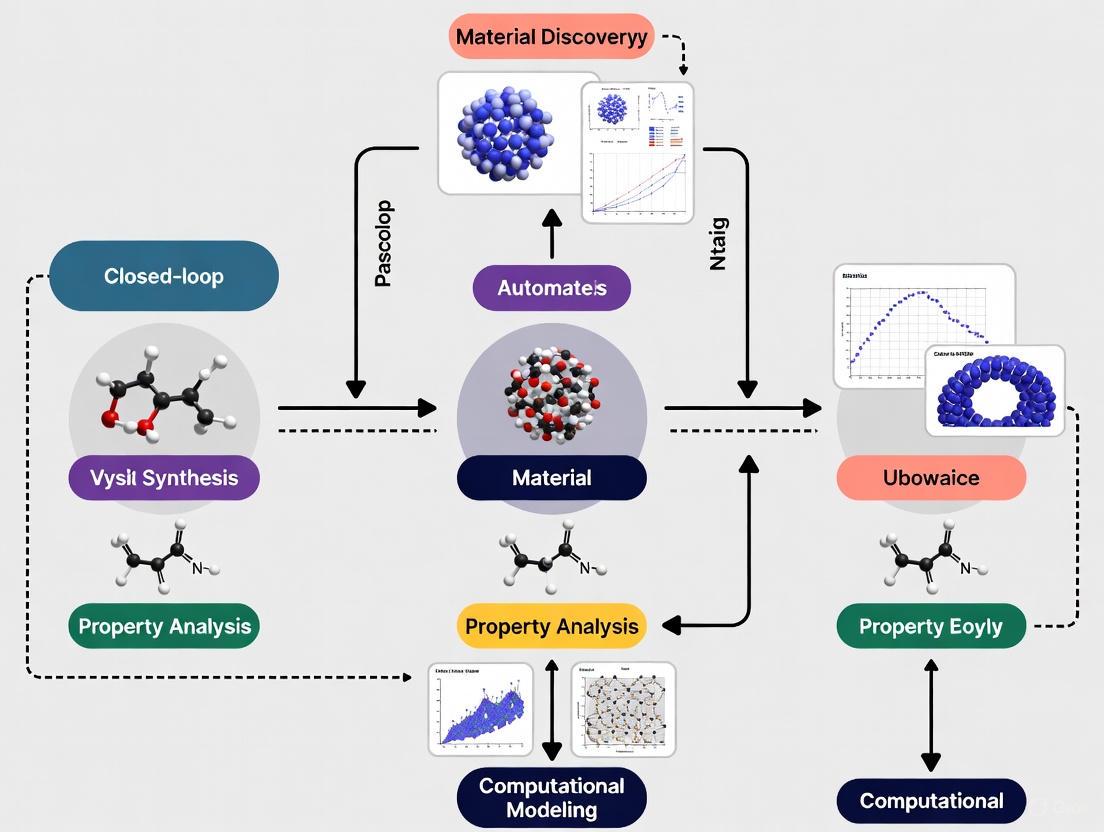

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core operational workflow of a closed-loop discovery system:

Closed-Loop Discovery Workflow

Key Algorithmic Engines: Bayesian Optimization and Active Learning

The intellectual core of any closed-loop discovery system resides in its algorithmic engines for experimental planning. While various machine learning approaches can be employed, Bayesian optimization (BO) has emerged as a particularly powerful framework for guiding autonomous materials discovery. Bayesian optimization efficiently navigates complex experimental spaces by balancing exploration (probing uncertain regions) and exploitation (refining promising candidates) [5] [1]. As one researcher explains, "Bayesian optimization is like Netflix recommending the next movie to watch based on your viewing history, except instead it recommends the next experiment to do" [3].

The fundamental BO process involves maintaining a probabilistic model, typically a Gaussian process, that predicts the objective function (e.g., material performance) and its uncertainty across the parameter space. An acquisition function then uses these predictions to quantify the utility of performing an experiment at any given point. Common acquisition functions include Expected Improvement (EI), Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), and Probability of Improvement (PI) [5]. However, standard BO approaches are often limited to single-objective optimization and can struggle with the complex, multi-faceted goals typical of real materials discovery campaigns.

Recent algorithmic advances have substantially expanded these capabilities. The Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) framework enables researchers to target specific experimental goals through straightforward user-defined filtering algorithms, which are automatically translated into intelligent data collection strategies [5]. This approach allows systems to target specific regions of interest rather than simply finding global optima. Similarly, the CAMEO algorithm implements a materials-specific active learning campaign that combines the joint objectives of maximizing knowledge of phase maps while hunting for materials with extreme properties [1]. These sophisticated algorithms can incorporate physical knowledge (e.g., Gibbs phase rule) and prior experimental data to focus searches on regions where significant property changes are likely, such as phase boundaries [1].

Algorithmic Framework Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process of a Bayesian optimization algorithm within a closed-loop system:

Bayesian Optimization Loop

Implementation Frameworks and Experimental Methodologies

The theoretical framework of closed-loop discovery is implemented through specific software and hardware architectures that enable autonomous experimentation. One notable software platform is NIMO (NIMS orchestration system), an orchestration software designed to support autonomous closed-loop exploration and made publicly available on GitHub [6]. NIMO incorporates Bayesian optimization methods specifically designed for composition-spread films, enabling the selection of promising composition-spread films and identifying which elements should be compositionally graded. This implementation includes specialized functions like "nimo.selection" in "COMBI" mode for managing combinatorial experiments [6].

Another sophisticated platform is CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists), which advances beyond standard Bayesian optimization by incorporating information from diverse sources including scientific literature, chemical compositions, microstructural images, and human feedback [3]. CRESt uses multimodal data to create knowledge embeddings of material recipes before experimentation, then performs principal component analysis to identify a reduced search space that captures most performance variability. Bayesian optimization in this refined space, augmented by newly acquired experimental data and human feedback, provides a significant boost in active learning efficiency [3].

From a hardware perspective, two primary experimental methodologies have emerged for autonomous materials discovery:

High-Throughput Combinatorial Experimentation

This approach utilizes combinatorial techniques to fabricate large numbers of compounds with varying compositions on a single substrate. For example, in one implementation, composition-spread films are deposited using combinatorial sputtering, followed by photoresist-free device fabrication via laser patterning and simultaneous measurement using customized multichannel probes [6]. This methodology enables the efficient exploration of complex multi-element systems, such as the optimization of five-element alloy systems consisting of three 3d ferromagnetic elements (Fe, Co, Ni) and two 5d heavy elements (Ta, W, or Ir) to maximize the anomalous Hall effect [6].

Continuous Flow Platforms

An alternative methodology employs continuous flow reactors where chemical mixtures are varied dynamically and monitored in real-time. Recent advances have shifted from steady-state flow experiments to dynamic flow experiments, where chemical mixtures are continuously varied through the system and monitored in real-time [4]. This "streaming-data" approach allows systems to capture data every half-second throughout reactions, transforming materials discovery from a series of snapshots to a continuous movie of reaction dynamics. This intensifies data collection by at least 10x compared to previous methods and enables machine learning algorithms to make smarter, faster decisions [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents commonly used in closed-loop materials discovery experiments:

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Closed-Loop Discovery

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| 3d Ferromagnetic Elements | Fe (Iron), Co (Cobalt), Ni (Nickel) | Primary ferromagnetic components for magnetic materials discovery [6] |

| 5d Heavy Elements | Ta (Tantalum), W (Tungsten), Ir (Iridium) | Additives to enhance spin-orbit coupling in Hall effect studies [6] |

| Catalyst Precursors | Palladium, Platinum, Multielement catalysts | Electrode materials for fuel cell optimization [3] |

| Phase-Change Materials | Ge–Sb–Te (Germanium-Antimony-Tellurium) | Base system for phase-change memory material discovery [1] |

| Flow Chemistry Solvents | Various organic solvents | Reaction medium for continuous flow synthesis platforms [7] [4] |

Case Studies in Autonomous Materials Discovery

Case Study 1: Accelerated Discovery of Phase-Change Memory Materials

The CAMEO (closed-loop autonomous system for materials exploration and optimization) algorithm was implemented at a synchrotron beamline to accelerate the discovery of phase-change memory materials within the Ge-Sb-Te ternary system [1]. The research goal was to identify compositions with the largest difference in optical bandgap (ΔEg) between amorphous and crystalline states, which correlates with optical contrast for photonic switching devices. The methodology integrated high-throughput synthesis of composition spreads with real-time X-ray diffraction for structural characterization and ellipsometry for optical property measurement.

CAMEO employed a unique active learning strategy that combined phase mapping with property optimization. The algorithm used Bayesian graph-based predictions combined with risk minimization-based decision making, ensuring that each measurement maximized phase map knowledge while simultaneously hunting for optimal properties [1]. This physics-informed approach recognized that property extrema often occur at phase boundaries, allowing it to focus searches on these scientifically strategic regions. The implementation featured a human-in-the-loop component where human experts could provide guidance while machine learning presided over decision making.

This closed-loop discovery campaign resulted in the identification of a novel epitaxial nanocomposite phase-change material at a phase boundary between the distorted face-centered cubic Ge-Sb-Te structure and a phase-coexisting region of GST and Sb-Te [1]. The discovered material demonstrated optical contrast superior to the well-known Ge₂Sb₂Te₅ (GST225) compound, and devices fabricated from this material significantly outperformed GST225-based devices. This discovery was achieved with a reported 10-fold reduction in required experiments compared to conventional approaches, with each autonomous cycle taking merely seconds to minutes [1].

Case Study 2: Autonomous Optimization of the Anomalous Hall Effect

Researchers demonstrated an autonomous closed-loop exploration of composition-spread films to enhance the anomalous Hall effect (AHE) in a five-element alloy system [6]. The experimental goal was to maximize the anomalous Hall resistivity (ρ_yxA) in a system comprising three 3d ferromagnetic elements (Fe, Co, Ni) and two 5d heavy elements selected from Ta, W, or Ir. The closed-loop system integrated combinatorial sputtering deposition, laser patterning for device fabrication, and simultaneous AHE measurement using a customized multichannel probe.

The methodology employed Bayesian optimization specifically designed for composition-spread films, implemented within the NIMO orchestration system [6]. This specialized algorithm could select which elements to compositionally grade and identify promising composition ranges. The autonomous system required minimal human intervention—only for sample transfer between instruments—with all other processes including recipe generation, data analysis, and experimental planning operating automatically.

Through this autonomous exploration, the system discovered an optimal composition of Fe₄₄.₉Co₂₇.₉Ni₁₂.₁Ta₃.₃Ir₁₁.₇ in amorphous thin film form, which achieved a maximum anomalous Hall resistivity of 10.9 µΩ cm [6]. This performance is comparable to Fe-Sn, which exhibits one of the largest anomalous Hall resistivities among room-temperature-deposited magnetic thin films. The successful optimization demonstrated the efficacy of closed-loop approaches for navigating complex multi-element parameter spaces and identifying optimal compositions with minimal human intervention.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table compares the performance metrics reported in recent closed-loop materials discovery studies:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Closed-Loop Discovery Systems

| Study Focus | Acceleration Factor | Key Performance Metric | Experimental Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Framework [2] | 10-25x acceleration | 90-95% reduction in design time | Not specified |

| Phase-Change Memory [1] | 10x reduction in experiments | Discovered novel nanocomposite | Cycles: seconds to minutes |

| Fuel Cell Catalysts [3] | 9.3x improvement in power density/$ | Record power density in fuel cell | 3,500 tests over 3 months |

| Dynamic Flow System [4] | 10x more data collection | Identification on first try after training | Continuous real-time monitoring |

| Anomalous Hall Effect [6] | Not specified | 10.9 µΩ cm Hall resistivity | ≈1-2h synthesis, 0.2h measurement |

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

As closed-loop discovery matures, several emerging trends and future directions are shaping its development. There is growing emphasis on multimodal learning systems that incorporate diverse data types including scientific literature, experimental results, imaging data, and structural analysis [3]. The CRESt platform exemplifies this direction, using literature knowledge to create preliminary embeddings of material recipes before any experimentation occurs [3]. Similarly, there is increasing interest in explainable AI approaches that improve model transparency and physical interpretability, building trust in autonomous systems among scientists [8].

Significant progress is being made in addressing reproducibility challenges through integrated monitoring systems. For instance, some platforms now couple computer vision and vision language models with domain knowledge to automatically detect experimental anomalies and suggest corrections [3]. These systems can identify issues such as millimeter-sized deviations in sample shape or pipette misplacements, enabling more consistent experimental outcomes. Furthermore, the development of standardized data formats and open-access datasets including negative results is crucial for advancing the field and improving model generalizability [8].

Despite rapid progress, several challenges remain for widespread adoption. Current systems still face limitations in model generalizability across different materials systems and experimental conditions [8]. The integration of physical knowledge with data-driven models represents a promising approach to address this limitation. Additionally, as closed-loop systems become more complex, ensuring robust system integration and developing effective human-AI collaboration frameworks becomes increasingly important [1]. Most implementations still require some human intervention for complex troubleshooting, indicating that fully autonomous labs remain an aspirational goal rather than an immediate reality [3]. Nevertheless, the accelerating pace of innovation in closed-loop discovery systems continues to transform them from specialized research tools into powerful, general-purpose platforms for scientific advancement.

The discovery of novel materials is a fundamental driver of industrial innovation, yet its traditional pace is slow, often relying on serendipitous discoveries. The closed-loop material discovery process represents a transformative approach, seamlessly integrating artificial intelligence (AI) with high-throughput experimentation to create an iterative, self-improving system. This paradigm leverages a variety of machine learning (ML) engines—from deep learning to Bayesian optimization—to rapidly explore vast chemical spaces, predict promising candidates, and refine models based on experimental outcomes. By framing this process within the context of accelerated electrochemical materials discovery, such as for energy storage, generation, and chemical production, we see its critical role in overcoming material bottlenecks related to cost, durability, and scalability that currently limit the progress of sustainable technologies [9]. The core of this closed-loop system is the continuous feedback between computational prediction and experimental validation, which actively addresses the common machine learning challenge of poor performance on out-of-distribution data, thereby significantly accelerating the intentional discovery of new functional materials [10].

Core AI and ML Engines in Material Discovery

Deep Learning and Representation Learning

Deep learning architectures, particularly graph neural networks (GNNs), have become a cornerstone for molecular and material property prediction. These models excel because they can naturally represent atomic structures as attributed graphs where nodes correspond to atoms and edges to bonds. Advanced GNNs utilize hierarchical message passing and multilevel interaction schemes to aggregate information from atom-wise, pair-wise, and many-body interactions, thereby capturing complex quantum mechanical effects essential for accurate property prediction [11]. For instance, models like GEM-2 efficiently model full-range many-body interactions using axial attention mechanisms, reducing computational complexity while boosting accuracy [11].

Representation learning from stoichiometry (RooSt) is another powerful approach that predicts material properties using only chemical composition, without requiring structural information. This is particularly valuable in early discovery stages where crystal structures may be unknown. RooSt enables greater predictive sensitivity across diverse material spaces, facilitating the identification of novel compounds [10]. Furthermore, geometric graph contrastive learning (GeomGCL) aligns two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) molecular representations, encouraging robustness to input modalities and addressing data scarcity challenges [11].

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI)

Generative AI models have emerged as a transformative tool for designing structurally diverse, chemically valid, and functionally relevant molecules and materials. Key architectures include:

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs): Encode input data into a lower-dimensional latent representation and reconstruct it from sampled points, ensuring a smooth latent space for realistic data generation. GraphVAEs are particularly valuable for molecular generation, enabling efficient exploration and interpolation in continuous chemical space [12].

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): Employ two competing networks—a generator creating synthetic data and a discriminator distinguishing real from generated data—in an iterative training process that progressively improves output quality [12].

- Transformer-based Models: Originally developed for natural language processing (NLP), these models process data with long-range dependencies using self-attention mechanisms. In molecular design, they operate on textual representations like SMILES or SELFIES, learning subtle dependencies in structural data [11] [12].

- Diffusion Models: Generate data by progressively adding noise to a clean sample and learning to reverse this process through denoising. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) have demonstrated exceptional performance in high-quality molecular generation [12].

Bayesian Optimization and Active Learning

Bayesian optimization (BO) is a powerful strategy for navigating high-dimensional chemical or latent spaces, particularly when dealing with expensive-to-evaluate objective functions such as docking simulations or quantum chemical calculations. BO develops a probabilistic model of the objective function, typically using Gaussian processes, to make informed decisions about which candidate molecules to evaluate next. In generative models, BO often operates in the latent space of architectures like VAEs, proposing latent vectors that are likely to decode into desirable molecular structures [12].

Active learning is closely related to BO and is fundamental to the closed-loop discovery process. It iteratively selects the most informative data points to be added to the training set, focusing experimental resources on materials that are both predicted to have high performance and are sufficiently distinct from known materials. This approach maximizes the efficiency of the discovery process by prioritizing experiments that will most improve the model [10].

Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning (RL) frames molecular design as a sequential decision-making process where an agent learns to navigate chemical space by taking actions (e.g., adding atoms or bonds) and receiving rewards based on the resulting molecular properties. The Graph Convolutional Policy Network (GCPN) uses RL to sequentially add atoms and bonds, constructing novel molecules with targeted properties [12]. RL approaches can be enhanced by multi-objective reward functions that simultaneously optimize for multiple characteristics such as binding affinity, synthetic accessibility, and drug-likeness.

Table 1: Key AI/ML Engines and Their Applications in Material Discovery

| ML Engine | Primary Function | Typical Architectures/Variants | Application in Material Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning | Property prediction from structure | GNNs, RooSt, CNNs, GeomGCL | Predicting Tc of superconductors, electronic properties, stability [11] [10] |

| Generative AI | De novo molecular design | VAEs, GANs, Transformers, Diffusion Models | Generating novel drug candidates, electrolytes, catalyst materials [12] |

| Bayesian Optimization | Global optimization of black-box functions | Gaussian Processes, Tree-structured Parzen Estimators | Optimizing molecular structures for target properties in latent space [12] |

| Reinforcement Learning | Sequential decision making in chemical space | GCPN, MolDQN, GraphAF | Optimizing synthetic pathways, multi-property molecular design [12] |

The Closed-Loop Workflow: Integration of Methods

The true power of these AI and ML engines is realized when they are integrated into a cohesive, automated workflow. The closed-loop process connects computational prediction, experimental synthesis, and characterization with model refinement in a continuous cycle.

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a closed-loop material discovery system, showing how different AI/ML engines integrate with experimental processes:

This workflow demonstrates how the system becomes more intelligent with each iteration. As experimental data—both positive and negative results—are fed back into the ML models, their predictive accuracy for previously unexplored regions of chemical space improves dramatically. In a landmark study on superconducting materials, this closed-loop approach more than doubled the success rate for superconductor discovery compared to initial predictions [10].

Quantitative Performance and Benchmarking

To effectively evaluate and compare different AI/ML approaches, standardized benchmarking on established datasets is crucial. The performance of property prediction models is typically assessed using metrics such as mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and coefficient of determination (R²).

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of AI/ML Models on Standard Material Datasets

| Model/Architecture | Dataset | Key Properties Predicted | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEM-2 | PCQM4Mv2 | Molecular properties | ~7.5% improvement in MAE vs. prior methods | [11] |

| MGCN | QM9 | Atomization energy, frontier orbital energies, etc. | MAE below chemical accuracy | [11] |

| Mol-TDL | Polymer datasets | Polymer density, refractive index | Enhanced R² and reduced RMSE vs. traditional GNNs | [11] |

| RooSt | SuperCon, MP, OQMD | Superconducting transition temperature (Tₕ) | Doubled success rate in experimental validation after closed-loop cycles | [10] |

| GaUDI | Organic electronic molecules | Electronic properties | 100% validity in generated structures for single/multi-objective optimization | [12] |

Beyond these quantitative metrics, the ultimate validation of these models comes from experimental confirmation of their predictions. In the closed-loop superconducting materials discovery project, the iterative process led to the discovery of a previously unreported superconductor in the Zr-In-Ni system, re-discovery of five superconductors unknown in the training datasets, and identification of two additional phase diagrams of interest [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

High-Throughput Computational Screening Protocol

A typical workflow for high-throughput computational screening of materials involves the following detailed methodology [9]:

- Data Curation and Featurization: Compile initial training data from existing materials databases (e.g., SuperCon for superconductors, QM9 for molecular properties). Represent each material using feature vectors derived from composition and/or structure. Magpie features are commonly used for compositional representations, while graph-based representations are used for structured data [10].

- Model Training and Validation: Train an ensemble of ML models (e.g., RooSt for composition, GNNs for structures) using supervised learning. Employ Leave-One-Cluster-Out Cross-Validation (LOCO-CV) to assess model performance on chemically distinct materials, simulating real-world discovery scenarios [10].

- Candidate Prediction and Filtering: Apply trained models to large candidate databases (e.g., Materials Project, OQMD). Filter predictions based on:

- Predicted property values (e.g., high Tₕ for superconductors).

- Stability metrics (e.g., energy above hull < 0.05 eV/atom).

- Distance in feature space from known materials to ensure exploration of novel chemistries [10].

- Prioritization for Experimental Validation: Rank filtered candidates using multi-factorial prioritization that considers synthetic feasibility, safety, and potential for doping or modification [10].

Closed-Loop Experimental Validation Protocol

The experimental arm of the closed-loop process follows this methodology [10]:

- Synthesis Planning: For each prioritized candidate, explore nearby compositions and similar structures to account for sensitivity to stoichiometry and processing conditions. Consider isostructural compounds with promising band structures.

- High-Throughput Synthesis: Utilize automated synthesis platforms capable of parallel processing of multiple compositions. Techniques may include solid-state reaction, thin-film deposition, or solution-based synthesis depending on the material system.

- Structural Characterization: Employ powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) to verify phase formation and purity. Compare experimental patterns with computational predictions where available.

- Property Measurement: Conduct temperature-dependent AC magnetic susceptibility measurements to screen for superconductivity (perfect diamagnetism below Tₕ). For other material properties, relevant high-throughput characterization techniques (e.g., electrochemical testing for battery materials) are employed.

- Data Integration: Format experimental results (both positive and negative) consistently for feedback into the computational models. This includes precise synthesis conditions, characterization data, and measured properties.

Generative Molecular Design Protocol

For generative AI-driven molecular design, a representative protocol based on reinforcement learning includes [12]:

- Environment Setup: Define the chemical space and action space (e.g., available atoms, bonds, functional groups).

- Agent Training: Initialize the RL agent (e.g., GCPN) and train through multiple episodes where:

- The agent starts with a simple molecular fragment.

- At each step, the agent selects an action (add atom, form bond, etc.) based on its current policy.

- The episode terminates when a valid molecule is formed or a maximum step count is reached.

- The agent receives a reward based on the properties of the final molecule.

- Reward Shaping: Design multi-objective reward functions that incorporate target properties (e.g., binding affinity, solubility, synthetic accessibility). Potential-based reward shaping can improve learning efficiency.

- Validation and Iteration: Validate generated molecules using independent property predictors or docking simulations. Iterate the training process with refined reward functions based on validation results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental validation of AI-predicted materials requires specific reagents, instrumentation, and computational resources. The following table details key components of the research toolkit for closed-loop material discovery.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Closed-Loop Discovery

| Tool/Reagent | Specification/Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Materials | High-purity elements (e.g., Zr, In, Ni powders >99.9% purity) | Synthesis of predicted ternary compounds (e.g., Zr-In-Ni system) [10] |

| Computational Databases | SuperCon, Materials Project (MP), Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) | Sources of training data and candidate materials for screening [10] |

| High-Throughput Synthesis Platform | Automated solid-state reactor or sputtering system | Parallel synthesis of multiple candidate compositions [9] |

| Powder X-ray Diffractometer | Phase identification and purity assessment | Verification of successful synthesis of target compounds [10] |

| Physical Property Measurement System | AC magnetic susceptibility measurement | Screening for superconductivity (diamagnetic response below Tₕ) [10] |

| Generative AI Software | GCPN, GraphAF, GaUDI frameworks | De novo molecular design with targeted properties [12] |

| Bayesian Optimization Library | Gaussian Process implementation with acquisition functions | Optimization in latent chemical space for multi-property design [12] |

The integration of AI and machine learning engines—from deep learning to Bayesian optimization—into a closed-loop material discovery framework represents a paradigm shift in how we approach the development of new functional materials. This synergistic combination of computational prediction and experimental validation creates an accelerated, iterative process that actively learns from both successes and failures. As these technologies continue to mature, addressing challenges related to data quality, model interpretability, and reliable out-of-distribution prediction, they hold the potential to dramatically shorten the timeline from conceptual design to realized material, ultimately accelerating the development of technologies critical for addressing global challenges in energy, sustainability, and healthcare.

Robotic Automation and High-Throughput Experimentation

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) represents a paradigm shift in materials and drug discovery, moving away from traditional sequential experimentation toward massively parallel testing and synthesis. When integrated with robotic automation and artificial intelligence, HTE forms the core of self-driving laboratories (SDLs)—closed-loop systems that autonomously propose, execute, and analyze experiments to accelerate discovery. These systems are revolutionizing the development of advanced materials, from energy storage solutions to pharmaceutical compounds, by reducing discovery timelines from years to days while significantly cutting costs and resource consumption [13].

The fundamental principle of closed-loop material discovery involves creating an iterative, autonomous cycle where computational models propose candidate materials, robotic systems synthesize and test them, and machine learning algorithms analyze the results to inform the next round of experiments. This creates a continuous feedback loop that rapidly converges toward optimal solutions. Current advancements in 2025 focus on evolving these systems from isolated, lab-centric tools into shared, community-driven experimental platforms that leverage collective intelligence across institutions [14].

Current State of Robotic Automation in HTE

Key Technological Trends

The field of laboratory automation is undergoing rapid transformation, with several key trends emerging in 2025:

Modular System Integration: Laboratories are moving away from isolated "islands of automation" toward integrated systems connected through modular software architectures with well-defined APIs. This approach allows scientists to automate entire workflows seamlessly and reduces friction in data exchange between different instruments and platforms [15].

Advanced Motion Control: Magnetic levitation decks and vehicles have emerged as a transformative technology for material handling. These systems use contactless magnetic fields to move labware and reagents between stations without mechanical rails, reducing maintenance downtime and enabling dynamic rerouting to avoid workflow bottlenecks [15].

Specialized AI Copilots: The initial enthusiasm for generic generative AI in research settings has evolved toward specialized "copilots"—AI assistants focused on specific domains such as experiment design or software configuration. These systems help scientists encode complex processes into executable protocols while leaving scientific reasoning to human experts [15].

Scientist-Coder Hybrids: A new breed of researchers who can both design experiments and write code is emerging. With robust APIs and user-friendly programming libraries, scientists can now directly automate their workflows without depending on specialized software teams, significantly shortening the feedback loop from hypothesis to results [15].

Enabling Technologies

Table 1: Key Enabling Technologies for Modern HTE

| Technology | Function | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Flow Reactors | Enable continuous variation of chemical mixtures through microfluidic systems | Allows real-time monitoring and data collection every 0.5 seconds versus hourly measurements [16] |

| Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs) | Combine robotics, AI, and autonomous experimentation | Can conduct over 25,000 experiments with minimal human oversight [14] |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithms | Guide experimental decision-making in autonomous systems | Demonstrated ability to discover materials with unprecedented properties (e.g., doubling energy absorption benchmarks) [14] |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) | Helps users navigate experimental datasets and propose new experiments | Makes research more accessible through natural language interfaces [14] |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Dynamic Flow Experimentation for Inorganic Materials Synthesis

Traditional self-driving labs utilizing continuous flow reactors have relied on steady-state flow experiments, where reactions proceed to completion before characterization. A groundbreaking advancement in 2025 is the implementation of dynamic flow experiments that continuously vary chemical mixtures and monitor them in real-time.

Protocol: Dynamic Flow-Driven Materials Discovery

System Setup: Implement a continuous flow microreactor system with in-line spectroscopic characterization (e.g., UV-Vis, fluorescence). The system should include precisely controlled syringe pumps for reagent delivery, a temperature-controlled reaction microchannel, and real-time monitoring capabilities [16].

Precursor Formulation: Prepare precursor solutions with systematically varied compositions. For quantum dot synthesis, this may include cadmium and selenium precursors with different ligand concentrations and reaction modifiers.

Dynamic Flow Configuration: Program the fluidic system to continuously vary reactant ratios and flow rates according to a predefined experimental space, rather than operating at fixed steady-state conditions.

Real-Time Characterization: Implement in-line monitoring to capture material properties at regular intervals (e.g., every 0.5 seconds). For nanocrystal synthesis, this typically includes absorbance and photoluminescence spectra to determine particle size and quality.

Data Streaming and Machine Learning: Feed characterization data continuously to machine learning algorithms that map transient reaction conditions to steady-state equivalents, enabling the system to make predictive decisions about promising parameter spaces.

Autonomous Optimization: The machine learning algorithm uses acquired data to refine its model and select subsequent experimental conditions that maximize the probability of discovering materials with target properties [16].

This approach has demonstrated at least an order-of-magnitude improvement in data acquisition efficiency compared to state-of-the-art steady-state systems, while simultaneously reducing chemical consumption and experimental time [16].

Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflows

The most powerful HTE implementations combine computational screening with experimental validation in a tightly coupled loop:

Protocol: Closed-Loop Material Discovery

Computational Prescreening: Use density functional theory (DFT) and machine learning models to screen thousands of potential material compositions in silico, identifying the most promising candidates for experimental testing [17].

Automated Synthesis: Transfer top candidate compositions to robotic synthesis platforms. For battery materials, this may include automated pipetting systems that prepare precise stoichiometric ratios of precursor materials.

High-Throughput Characterization: Implement parallel testing capabilities for critical performance metrics. In electrochemical materials discovery, this includes automated systems for measuring energy density, cycle life, and safety parameters.

Data Integration and Model Refinement: Feed experimental results back into computational models to refine their predictive accuracy, creating a virtuous cycle of improvement with each iteration.

Studies show that over 80% of current high-throughput research focuses on catalytic materials, revealing significant opportunities for expanding these methodologies to other material classes such as ionomers, membranes, and electrolytes [17].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The implementation of robotic automation and HTE has yielded dramatic improvements in research efficiency across multiple domains.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of High-Throughput Experimentation Systems

| Metric Category | Traditional Methods | HTE with Automation | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Acquisition Efficiency | Single data points per experiment | 20+ data points per experiment (every 0.5s) | 10x increase [16] |

| Materials Discovery Timeline | Months to years | Days to weeks | 70% reduction [13] |

| Experimental Costs | Baseline | 50% reduction | Half the cost [13] |

| Chemical Consumption | Baseline | Significantly reduced | Less waste [16] |

| Energy Absorption Discovery | 26 J/g (previous benchmark) | 55 J/g (new benchmark) | Double the performance [14] |

Implementation Framework

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of HTE requires carefully selected reagents and materials that enable automated, parallel experimentation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HTE in Materials Discovery

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| FCF Brilliant Blue | Model compound for method validation | Spectroscopic standardization and protocol development [18] |

| CdSe Precursor Solutions | Quantum dot synthesis | Nanocrystal optimization using dynamic flow reactors [16] |

| Lithium-Ion Battery Cathode Materials | Energy storage research | High-throughput screening of Ni-Mn-Co ratios for optimal performance [13] |

| Agilent SureSelect Max DNA Library Prep Kits | Automated genomic workflows | Target enrichment protocols for sequencing applications [19] |

| 3D Cell Culture Matrices | Biological relevance enhancement | Automated organoid production for drug screening [19] |

System Architecture and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core closed-loop workflow of a modern self-driving laboratory:

Data Management and AI Integration

Effective data management is critical for HTE success. Modern systems must address:

- Metadata Capture: Comprehensive recording of all experimental conditions and instrument states to provide context for AI models [19].

- FAIR Data Practices: Ensuring data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable across research communities [14].

- Specialized AI Tools: Implementation of domain-specific AI assistants that help researchers navigate experimental datasets, ask technical questions, and propose new experiments through techniques like retrieval-augmented generation [14].

Leading organizations are converging on unified data platforms rather than maintaining disparate departmental systems, enabling consistent data models and streamlined governance while still allowing specialization through robust APIs [15].

Future Directions and Community Adoption

The next evolution of HTE and robotic automation focuses on transforming these systems from isolated resources into community-driven platforms. Initiatives like the AI Materials Science Ecosystem (AIMS-EC) aim to create open, cloud-based portals that couple science-ready large language models with experimental data streams, enabling broader collaboration [14].

The integration of human expertise with autonomous systems remains crucial. As noted by researchers, "Self-driving labs can operate autonomously, but when people contribute their knowledge and intuition, their potential increases dramatically" [14]. This human-AI collaboration represents the most promising path forward for accelerating materials discovery while maintaining scientific rigor and creativity.

The future will also see increased emphasis on sustainable research practices, with HTE systems designed to minimize chemical consumption, reduce waste generation, and optimize energy usage throughout the discovery process [16]. As these technologies become more accessible and community-driven, they hold the potential to democratize materials discovery and accelerate solutions to global challenges in energy, healthcare, and sustainability.

In modern materials science and drug development, the closed-loop discovery process represents a paradigm shift towards autonomous, AI-driven research. These systems integrate robotics, artificial intelligence, and high-throughput experimentation to dramatically accelerate the design and synthesis of novel materials [8]. Central to the success of this innovative framework is the effective management of the vast, complex data generated throughout the research lifecycle. The FAIR data principles—Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—provide the essential foundation that enables these autonomous laboratories to function efficiently and scale effectively [20]. This technical guide examines the critical intersection of FAIR data principles with specialized data platforms, framing their role within the context of accelerating closed-loop material discovery for research scientists and drug development professionals.

The FAIR Data Principles in Scientific Research

The FAIR principles establish a systematic framework for scientific data management and stewardship, specifically designed to optimize data reuse by both computational systems and human researchers [20]. In the context of closed-loop material discovery, where automated systems must rapidly access and interpret diverse datasets, adherence to these principles transitions from best practice to operational necessity.

The Four Principles Explained

- Findable: Data and metadata must be easily locatable by humans and computer systems through persistent identifiers and rich, searchable descriptions. This typically involves assigning Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) and registering data in indexed repositories [20].

- Accessible: Data should be retrievable using standardized, open protocols. Importantly, FAIR emphasizes "accessible under well-defined conditions," which may include appropriate authentication and authorization rather than complete open access, thus protecting intellectual property and patient privacy [20].

- Interoperable: Data must be structured using shared languages and standardized vocabularies to enable integration across diverse platforms and applications. This is particularly crucial when combining data from multiple sources such as genomic research, clinical trials, and materials characterization [20].

- Reusable: Data must be thoroughly described with clear usage licenses and detailed provenance information, meeting domain-specific community standards to ensure reliable replication and repurposing in new research contexts [20].

Distinguishing FAIR from Open Data

A critical conceptual distinction exists between FAIR data and open data, particularly relevant for pharmaceutical and biotech industries balancing collaboration with proprietary interests:

Table: FAIR Data vs. Open Data

| Aspect | FAIR Data | Open Data |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | Can be open or restricted based on use case | Always freely accessible to all |

| Primary Focus | Machine-readability and reusable data integration | Unrestricted sharing and transparency |

| Metadata Requirements | Rich metadata and documentation are mandatory | Metadata is beneficial but not strictly required |

| Licensing | Varies—can include access restrictions for proprietary data | Typically utilizes permissive licenses (e.g., Creative Commons) |

| Primary Application | Structured data integration in R&D workflows | Democratizing access to large public datasets |

While open data initiatives have accelerated research in areas like public health emergencies by providing unrestricted access to crucial datasets, FAIR principles offer a more nuanced approach suitable for proprietary research environments where data protection remains essential [20].

FAIR Data in Closed-Loop Material Discovery

Closed-loop material discovery systems represent the cutting edge of autonomous research, combining computational prediction, robotic experimentation, and AI-driven decision-making in integrated workflows. The effectiveness of these systems depends fundamentally on their ability to leverage high-quality, well-structured data at every process stage.

Recent advancements in autonomous laboratories demonstrate the transformative potential of integrated AI and robotics systems:

- The A-Lab: An autonomous laboratory for solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders that successfully realized 41 novel compounds from 58 targets over 17 days of continuous operation. The system uses computations, historical data, machine learning, and active learning to plan and interpret experiments performed entirely by robotics [21].

- Self-Driving PVD System: Researchers at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering developed an automated system that grows thin metal films for electronics using robotics and AI. The system "automates the entire loop—running experiments, measuring the results and then feeding those results back into a machine-learning model that guides the next attempt" [22].

- CAMEO Algorithm: The Closed-Loop Autonomous System for Materials Exploration and Optimization implements active learning to guide synchrotron beamline experiments, accelerating both phase mapping and property optimization with each cycle taking seconds to minutes [1].

Quantitative Acceleration from Automated Frameworks

Benchmarking studies demonstrate the significant efficiency gains enabled by closed-loop frameworks driven by sequential learning:

Table: Closed-Loop Framework Performance Benchmarks

| Metric | Traditional Approaches | Closed-Loop Framework | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Time | Baseline | 10-25x acceleration | 90-95% reduction |

| Researcher Productivity | Baseline | Significant improvement | Not quantified |

| Project Costs | Baseline | Overall reduction | Not quantified |

| Experiment Iteration Time | Days for manual PVD synthesis [22] | Dozens of runs in days [22] | Weeks of work reduced to days |

| Target Achievement | Months of manual optimization | Average of 2.3 attempts for optical properties [22] | Orders of magnitude faster |

The Citrine collaboration with Carnegie Mellon University, MIT, and Julia Computing demonstrated that fully automated closed-loop frameworks driven by sequential learning can accelerate materials discovery by 10-25x compared to traditional approaches [2].

Experimental Protocols in Closed-Loop Systems

Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) Automation

The self-driving PVD system developed at UChicago PME exemplifies the integration of FAIR principles within an automated materials synthesis workflow:

- Sample Handling: Robotic system assembles and handles samples for each PVD process step [22]

- Calibration Layer: System creates a thin calibration layer before each experiment to account for unpredictable variables like substrate differences or trace gases, systematically capturing variations that would otherwise introduce noise in training data [22]

- ML-Guided Optimization: Machine learning algorithm predicts parameters needed for specific thin film properties, synthesizes and analyzes the product, then tweaks parameters iteratively [22]

- Result Validation: The system successfully grew silver films with specific optical properties, hitting desired targets in an average of 2.3 attempts and exploring full experimental conditions in dozens of runs versus weeks of manual work [22]

Autonomous Solid-State Synthesis (A-Lab Protocol)

The A-Lab implements a comprehensive autonomous workflow for inorganic powder synthesis:

- Target Identification: Compounds screened using large-scale ab initio phase-stability data from Materials Project and Google DeepMind, considering only air-stable targets [21]

- Recipe Generation: Initial synthesis recipes proposed by natural-language models trained on historical literature data, assessing target similarity through natural-language processing [21]

- Temperature Optimization: Synthesis temperature proposed by secondary ML model trained on heating data from literature [21]

- Robotic Execution:

- Station 1: Precursor powders dispensed, mixed, and transferred to alumina crucibles

- Station 2: Robotic arm loads crucibles into one of four box furnaces for heating

- Station 3: After cooling, samples ground into fine powder and characterized by XRD [21]

- Phase Analysis: XRD patterns analyzed by probabilistic ML models trained on experimental structures from ICSD, with patterns for novel targets simulated from computed structures and corrected for DFT errors [21]

- Active Learning: Failed recipes trigger ARROWS³ algorithm that integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed outcomes to predict improved solid-state reaction pathways [21]

CAMEO Bayesian Active Learning

The Closed-Loop Autonomous System for Materials Exploration and Optimization implements a specialized approach for functional materials discovery:

- Algorithm Core: Bayesian active learning techniques balance exploration of unknown functions with exploitation of prior knowledge to identify optima [1]

- Phase Mapping: Subsequent measurements driven by Bayesian graph-based predictions combined with risk minimization-based decision making [1]

- Human-in-the-Loop: Embodiment of human-machine interaction where human expertise contributes within each cycle, with live visualization of data analysis and decision making providing interpretability [1]

- Application Example: Successful discovery of novel epitaxial nanocomposite phase-change memory material in Ge-Sb-Te ternary system with optical contrast superior to well-known Ge₂Sb₂Te₅ [1]

Visualization of Closed-Loop Workflows

Generalized Closed-Loop Materials Discovery Workflow

FAIR Data Integration in Research Workflow

Essential Research Tools and Platforms

Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Discovery

Table: Key Research Resources for Closed-Loop Materials Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Databases | Materials Project [21], Google DeepMind stability data [21] | Provides ab initio phase-stability data for target identification and validation |

| Synthesis Robotics | Automated powder handling systems [21], Robotic arms for furnace loading [21] | Executes physical synthesis experiments with minimal human intervention |

| Characterization Instruments | X-ray diffraction (XRD) [21], Scanning ellipsometry [1] | Provides structural and property data for synthesized materials |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Natural language processing for literature [21], Bayesian optimization [1], Probabilistic phase analysis [21] | Interprets data, plans experiments, and identifies optimal synthesis pathways |

| Data Management Platforms | Specialized bioinformatics services [20], FAIR data curation platforms [20] | Ensures data interoperability, reusability, and compliance with regulatory standards |

The integration of FAIR data principles with specialized platforms creates the essential foundation enabling the revolutionary potential of closed-loop material discovery systems. These autonomous laboratories—demonstrating 10-25x acceleration in discovery timelines and successfully synthesizing dozens of novel compounds through continuous operation—represent the future of materials and pharmaceutical research [2] [21]. The implementation of robust data management strategies adhering to FAIR principles ensures that the vast quantities of data generated by these systems remain findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable, thereby maximizing research investment and enabling cumulative scientific progress. As these technologies continue to evolve, the organizations that strategically implement integrated FAIR data frameworks will maintain a decisive competitive advantage in the rapidly advancing landscape of AI-driven scientific discovery.

The integration of computational modeling and Digital Twins is revolutionizing material discovery and drug development by creating a closed-loop, automated research environment. These enablers facilitate the rapid exploration of chemical and biological spaces, predict material performance and drug efficacy with high precision, and systematically optimize development protocols. By bridging multiscale data with physical experiments through continuous feedback, they dramatically accelerate the transition from initial discovery to deployed therapeutic solutions, offering unprecedented efficiency and insight in pharmaceutical research.

The traditional paradigms of material discovery and drug development are characterized by high costs, extensive timelines, and significant attrition rates. The emergence of sophisticated computational methods and the novel framework of Digital Twins (DTs) are poised to disrupt these paradigms. Computational modeling provides the foundational tools for in-silico analysis and prediction, while Digital Twins offer a dynamic, virtual representation of a physical entity or process that evolves throughout its lifecycle. In the context of closed-loop material discovery, these technologies work in concert: computational models simulate and predict behaviors at various scales, and Digital Twins integrate these models with real-world data from experiments and sensors, enabling continuous validation, refinement, and autonomous guidance of the research process [23] [24]. This synergy creates a powerful engine for innovation, allowing researchers to explore vast design spaces virtually, identify the most promising candidates for synthesis, and validate complex process-structure-property relationships with greater speed and accuracy than ever before.

Core Computational Methods and Workflows

Computational methods form the backbone of modern in-silico discovery, enabling researchers to model, simulate, and optimize complex biological and material systems across multiple scales.

Key Computational Techniques

Table 1: Core Computational Methods in Drug and Material Discovery

| Method Category | Key Techniques | Primary Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomolecular Simulation [25] | Molecular Dynamics (MD), Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM), Monte Carlo (MC) | Elucidating drug action mechanisms, identifying binding sites, calculating binding free energies. | Provides atomic-level insight into structural dynamics and thermodynamic properties. |

| Structure-Based Drug Design [25] | Molecular Docking, Homology Modeling | Predicting interaction patterns between a target protein and small molecule ligands. | Leverages 3D structural information for rational drug design. |

| Ligand-Based Drug Design [25] | Pharmacophore Modeling, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) | Designing novel drug candidates based on known active compounds. | Effective when the 3D structure of the target is unavailable. |

| Virtual Screening [26] [25] | High-Throughput Docking, Pharmacophore Screening | Rapidly searching ultra-large libraries (billions of compounds) for hit identification. | Dramatically reduces the experimental cost and time of lead discovery. |

| AI & Machine Learning [27] [28] | Deep Learning (e.g., CNNs, RNNs), Sparrow Search Algorithm, Active Learning | Predicting ligand properties, accelerating virtual screening, de novo molecular generation. | Learns complex patterns from large datasets to make rapid, accurate predictions. |

Experimental Protocol: An Integrated Virtual Screening Workflow

A typical protocol for ultra-large virtual screening, a cornerstone of computational drug discovery, involves a multi-step, iterative process [26]:

- Target Preparation: Obtain or predict the high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., via cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, or homology modeling). Prepare the structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states, and defining binding sites.

- Library Curation: Select a gigascale chemical library for screening (e.g., ZINC20, Enamine REAL). These on-demand libraries can contain billions of synthesizable compounds.

- Iterative Screening:

- Step 1 (Fast Filtering): Employ rapid, low-resolution methods like 2D fingerprint similarity or pharmacophore searches to reduce the library size from billions to millions.

- Step 2 (Molecular Docking): Perform molecular docking on the reduced set to predict binding poses and scores for millions of compounds.

- Step 3 (Advanced Scoring & ML): Apply more computationally expensive methods like free-energy perturbation or machine learning models trained on docking results to re-score and rank the top thousands of hits. This active learning loop iteratively improves the selection of candidates.

- Hit Validation: The top-ranked compounds (typically a few hundred) are synthesized or acquired and subjected to in vitro biochemical assays to confirm biological activity.

Digital Twins: The Bridge to a Closed-Loop Discovery Process

Digital Twins represent a transformative leap beyond standalone simulations. A Digital Twin is a high-fidelity, dynamic, in-silico representation of a unique physical twin—be it a specific material sample, a drug candidate, or a manufacturing process—that is continuously updated with data from its physical counterpart throughout its lifecycle [23] [24].

The Architecture of a Material Digital Twin

For materials, the Digital Twin must capture both its form and function across scales [24]. The form is the material's hierarchical structure, from atomic arrangement to microstructural features, often captured using frameworks like n-point spatial correlations. The function is the material's response to external stimuli (e.g., stress, temperature), captured by homogenization and localization models that link structure to properties. The Digital Twin is not static; it evolves by assimilating new data from experiments (e.g., microscopy, mechanical testing) and physics-based simulations, refining its predictive models to more accurately mirror the physical twin's past, present, and future states.

Workflow: The Digital Twin in a Closed Loop

The power of the Digital Twin is fully realized within a closed-loop material discovery setup, where it acts as the central decision-making engine.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effective implementation of computational modeling and Digital Twins relies on a suite of software tools, data resources, and computational platforms.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Computational Discovery

| Category | Item | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Platforms | Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD) [25] | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. |

| Docking & Virtual Screening Suites (e.g., AutoDock, Schrödinger) [26] [25] | Predicts how small molecules bind to a target protein and screens large libraries. | |

| AI/ML Libraries (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow) [28] | Provides frameworks for building and training custom machine learning models for property prediction. | |

| Data Resources | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [25] | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, essential for structure-based design. |

| Ultralarge Chemical Libraries (e.g., ZINC20, Enamine REAL) [26] | Provides access to billions of purchasable or synthesizable compounds for virtual screening. | |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-Performance Computing (HPC) [28] | Provides the parallel processing power required for large-scale simulations and AI model training. |

| GPU Accelerators [26] | Dramatically speeds up computationally intensive tasks like MD simulations and deep learning. |

Quantitative Data Analysis and Model Validation

The reliability of computational predictions is paramount. Model validation ensures that in-silico outputs are trustworthy and can guide real-world decisions.

Criteria for Model Evaluation

Evaluating computational models involves balancing multiple criteria [29]:

- Descriptive Adequacy (Goodness-of-Fit): Measures how well the model fits a specific set of observed data (e.g., using Sum of Squared Errors).

- Complexity: Reflects the model's flexibility, which can lead to overfitting—where a model learns noise in the training data instead of the underlying pattern, harming its predictive power.

- Generalizability: The most critical criterion, it assesses how well the model predicts new, unseen data. It represents a trade-off between goodness-of-fit and complexity.

Model Selection Methods

Formal methods have been developed to estimate generalizability by penalizing model complexity [29]:

- Akaike Information Criterion (AIC): An estimate of the information loss when a model is used to represent the true data-generating process. The model with the lowest AIC is preferred.

- Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC): Similar to AIC but with a stronger penalty for model complexity, often favoring simpler models.

Table 3: Quantitative Metrics for Model Validation

| Metric | Formula / Principle | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [29] | AIC = 2k - 2ln(L) (where k is parameters, L is max likelihood) | Lower AIC indicates better model, balancing fit and parsimony. |

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) [29] | BIC = k ln(n) - 2ln(L) (where n is sample size) | Stronger complexity penalty than AIC; lower BIC is better. |

| Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) [28] | RMSE = √(Σ(Pᵢ - Oᵢ)²/n) | Lower RMSE indicates higher predictive accuracy. |

| Contrast Ratio (for Visualizations) [30] | (L₁ + 0.05) / (L₂ + 0.05) (L is relative luminance) | WCAG AA requires ≥ 4.5:1 for normal text [30]. |

Building and Implementing Your Closed-Loop Workflow

The Predict-Make-Test-Analyze (PMTA) cycle represents a transformative, closed-loop paradigm for accelerating discovery in fields ranging from medicinal chemistry to materials science. This iterative process leverages computational prediction, automated synthesis and testing, and intelligent data analysis to dramatically reduce the time and cost associated with traditional research and development. By architecting a seamless, integrated workflow, researchers can transition from a linear, human-paced sequence of experiments to a rapid, data-rich cycle of continuous learning and optimization. This technical guide details the core components, methodologies, and infrastructure required to implement an effective PMTA cycle, framed within the context of automated material discovery research.

Core Components of the PMTA Cycle

The PMTA cycle is built upon four interconnected pillars. Each component must be robust and capable of integration with the others to create a truly closed-loop system.

Predict: This initial phase uses computational models to propose new candidate molecules or materials with desired properties. Modern approaches heavily leverage Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). Techniques include computer-assisted synthesis planning (CASP), which uses retrosynthetic analysis and reaction condition prediction to design feasible synthetic routes [31]. For materials science, high-throughput computational screening, often using density functional theory (DFT), is used to scan vast chemical spaces [17]. The output is a set of candidate structures with high predicted performance and a plan for their synthesis.

Make: The "Make" phase involves the physical synthesis of the predicted candidates. To achieve the required speed and reliability, this stage is highly automated. In medicinal chemistry, this often involves automated flow synthesis platforms, where reagents are pumped through reaction tubes or microfluidic chips, allowing for precise control of reaction parameters and seamless integration with purification systems like HPLC [7]. In materials science, high-throughput combinatorial methods are employed to create libraries of material samples, such as thin-film libraries, on a single substrate [32]. The key is the co-location of a wide array of building blocks and automated systems to remove delays in sourcing and manual handling [31] [33].

Test: This phase involves the high-throughput experimental evaluation of the synthesized candidates for the target properties. In drug discovery, this could mean biochemical assays to determine a compound's potency (e.g., IC50). These assays have been adapted to run in flow-based systems, complementing the flow chemistry in the "Make" phase and providing rich, rapid data sets [7]. For electrochemical materials, high-throughput testing might involve automated characterization of properties like catalytic activity or ionic conductivity across a combinatorial library [17]. The throughput of this stage must match the output of the "Make" phase to prevent bottlenecks.

Analyze: Here, the experimental data from the "Test" phase is processed and used to refine the predictive models, thus "closing the loop." This involves rigorous quantitative data analysis, including statistical analysis and machine learning, to extract meaningful structure-activity or structure-property relationships [34]. The creation of a Research Data Infrastructure (RDI) is crucial for the automated curation, storage, and management of the resulting experimental data and metadata, ensuring it is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) [32]. The insights gained directly inform the next "Predict" cycle, leading to the design of more promising candidates.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated, cyclical nature of this process.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

A well-architected PMTA cycle delivers transformative gains in speed and efficiency. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics reported from implemented systems.

Table 1: Reported Performance Metrics of Integrated PMTA Systems

| Metric | Traditional Workflow | Integrated PMTA Cycle | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle Time | "Weeks" [7] | "Less than 24 hours" for 14 compounds [7] | Medicinal Chemistry: Synthesis to assay |

| Synthesis Scale | Flask/round-bottom flask (10s-100s mL) | Microfluidic (μL volumes, <1mm tubing) [7] | Reaction volume |

| Automated Reagent Capacity | N/A | ~300 reagents [7] | Enumerating large chemical spaces |

| Data Point Sampling | Single endpoint measurement | "Rapidly sampled read out" providing "rich data set" [7] | Biochemical assay resolution |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Implementing a PMTA cycle requires robust, reproducible experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for two critical phases: automated synthesis and biochemical testing.

Protocol: Automated Flow Synthesis and Purification of Small Molecules

This protocol is adapted from integrated "Make" platforms used in medicinal chemistry [7].

Principle: To automatically synthesize and purify target molecules from a digital design using a continuous flow chemistry platform coupled with in-line purification.

Materials and Reagents:

- Reagent Deck: Automated carousel or liquid handler stocked with building blocks (e.g., carboxylic acids, amines, boronic acids, halides), catalysts, solvents, and reagents.

- Synthesis Platform: Commercial flow chemistry system with modules for pumping, mixing, and heated/cooled reactor coils (tube-based, with variable internal volume).

- Purification System: In-line High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system with an Evaporative Light-Scattering Detector (ELSD) or Mass Spectrometry (MS) for detection.

- Dilution Assembly: A system for post-purification dilution to prepare samples for assay.

Procedure:

- Platform Setup: The "Predict" phase outputs a list of target molecules and a reaction sequence. The automated reagent deck is loaded with the required starting materials and solvents.

- Reagent Delivery: The liquid handler precisely aspirates and loads the specified reagents into the injection loops or directly into the solvent streams of the flow synthesis system.

- Flow Synthesis: Reagents are pumped at defined flow rates into a mixing point and then through a temperature-controlled reactor coil. The residence time in the reactor is determined by the flow rate and the coil volume. For multi-step syntheses, reagent streams can be introduced sequentially at different points along the flow path.

- In-line Analysis and Purification: The reaction mixture is directly injected into the HPLC system. The ELSD detector identifies the peak corresponding to the desired product.

- Heart-Cutting: At the apex of the target HPLC peak, a fraction collector or valve is triggered to isolate the product ("heart-cutting"), ensuring the highest purity and concentration.

- Automated Dilution: The purified product stream is mixed with a diluent stream (e.g., assay buffer) at a controlled ratio to achieve the required concentration for biological testing.

- Output: The diluted, assay-ready sample is collected in a formatted plate for direct transfer to the "Test" phase.

Protocol: Flow-Based Biochemical Assay for Kinase Inhibition

This protocol details the "Test" component for determining inhibitory activity (IC50) in a continuous flow environment [7].

Principle: To measure the dose-response (IC50) of a synthesized compound against a kinase target (e.g., ABL1 kinase) by monitoring the inhibition of a biochemical reaction in a capillary flow system.

Materials and Reagents:

- Assay Platform: A nano-HPLC pump capable of generating precise, low-flow-rate gradients at high pressure.

- Reaction Capillary: Fused silica capillary tubing (e.g., 75 μm internal diameter).

- Assay Reagents: Purified kinase enzyme, fluorescently-labeled peptide substrate, ATP, and detection reagents.

- Detector: A fluorometer or other suitable detector with a flow cell.

Procedure:

- Gradient Formation: The nano-HPLC pump generates a gradient of the test compound. The compound is serially diluted in the capillary by mixing a concentrated stream of the compound with a buffer stream.

- Reagent Mixing: The compound gradient stream is merged with streams containing the enzyme, substrate, and ATP to initiate the kinase reaction.

- Incubation: The combined mixture flows through a reaction capillary of a specific length and internal volume, which serves as an incubation loop. The flow rate determines the reaction time.

- Detection: The reaction mixture passes through the detector, which measures the product formation (e.g., fluorescence). The signal is recorded as a continuous trace.

- Data Acquisition: The detector samples the signal at a high frequency at a single point in the flow path. As the compound concentration gradient passes through, the system records a full dose-response curve, with the inflection point corresponding to the IC50 value.

- Data Output: The rich, continuous data set is processed by analysis software to extract the IC50 value, which is then fed into the "Analyze" phase.

The following architecture diagram shows how these protocols are integrated into a full, automated platform.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful operation of a PMTA cycle depends on a carefully curated toolkit of chemical and software resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for the PMTA Cycle

| Tool Category | Specific Item / Solution | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Building Blocks | Enamine REAL Space, eMolecules, Sigma-Aldrich [31] [33] | Provides rapid access to a vast virtual and physical catalog of diverse starting materials (e.g., acids, amines, boronic esters) for automated synthesis. |

| Pre-validated Chemistry Kits | Suzuki-Miyaura Screening Plates, Buchwald-Hartwig Kits [31] | Pre-formatted sets of catalysts, ligands, and bases for high-throughput reaction scouting and optimization, reducing setup time. |

| Flow Synthesis Hardware | Vapourtec, Uniqsis, Chemtrix [7] | Commercial flow chemistry systems offering modular pumps, reactors, and temperature controls for robust and flexible "Make" automation. |

| Automated Purification | In-line Prep-HPLC with ELSD/MS [7] | Provides real-time purification and quantitation of synthesized compounds, essential for delivering high-quality, assay-ready material. |