Closed-Loop Autonomous Laboratories: Accelerating Novel Materials Discovery from AI to Reality

This article explores the transformative potential of closed-loop autonomous laboratories, or self-driving labs (SDLs), for researchers and professionals in materials science and drug development.

Closed-Loop Autonomous Laboratories: Accelerating Novel Materials Discovery from AI to Reality

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of closed-loop autonomous laboratories, or self-driving labs (SDLs), for researchers and professionals in materials science and drug development. It covers the foundational principles of SDLs, which integrate robotics, artificial intelligence, and advanced data analytics to automate the entire research cycle. The piece delves into the core methodology—the Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) loop—and showcases real-world applications, including the discovery of inorganic materials and organic molecules. It also addresses critical troubleshooting strategies for overcoming synthesis barriers and provides a comparative analysis of different SDL architectures and their validation through national initiatives. The conclusion synthesizes key takeaways and outlines the future impact of this technology on the pace and efficiency of biomedical and clinical research.

What Are Closed-Loop Autonomous Labs? The Foundation of Next-Gen Materials Discovery

The field of scientific research is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from simple automation to full autonomy. This paradigm shift represents a fundamental change in the role of the researcher and the capabilities of the laboratory. While automation focuses on executing predefined, repetitive tasks without human intervention, full autonomy introduces systems capable of intelligent decision-making, adaptive learning, and self-directed experimentation. This evolution is particularly transformative within the context of closed-loop autonomous laboratories for novel materials research, where the integration of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and data science is creating a new generation of "self-driving labs" that can hypothesize, experiment, and discover at unprecedented speeds [1].

The core of this shift lies in the transition from tools that extend human physical capabilities to systems that augment and, in specific domains, replace human cognitive functions. Where automated systems follow predetermined protocols, autonomous systems generate and refine these protocols based on real-time experimental outcomes. This creates a continuous, closed-loop cycle of learning and discovery that operates at a scale and pace impossible for human researchers alone. The implications for materials science and drug development are staggering, promising to compress discovery timelines that traditionally span decades into years or even months [1] [2].

Deconstructing the Spectrum: From Automation to Autonomy

Understanding the continuum from automation to full autonomy is critical to appreciating the current paradigm shift. These terms are often used interchangeably but represent fundamentally different levels of capability and intelligence.

Defining the Terms

Automation involves using technology to perform predefined, repetitive tasks with high efficiency and precision. In a research context, this includes robotic liquid handlers, automated high-throughput screening systems, and programmable instrumentation. The key limitation is that automated systems lack decision-making capacity; they execute a human-designed protocol without deviation or interpretation [3]. For example, an automated testing platform can run surveys at high volumes but relies on humans to design the experiments and interpret the results [3].

Full Autonomy describes systems that can independently perform the complete research cycle: generating hypotheses, planning and executing experiments, analyzing results, and using those insights to determine subsequent actions. These systems operate within a defined goal but are not constrained to a fixed path, allowing them to explore complex, multi-dimensional problem spaces and discover novel solutions that might elude human intuition [4] [1]. The definition of autonomy itself is "the system's ability to select an intermediate goal and/or course of action for achieving that goal, as well as approve or disapprove any previous and future choices while achieving its overall goal" [5].

The Five-Layer Architecture of Self-Driving Labs

Fully autonomous research systems, or Self-Driving Labs (SDLs), are built upon an integrated architecture consisting of five distinct layers [1]:

- Actuation Layer: Robotic systems that perform physical tasks such as dispensing, heating, mixing, and synthesizing materials.

- Sensing Layer: Sensors and analytical instruments that capture real-time data on process and product properties.

- Control Layer: Software that orchestrates experimental sequences, ensuring synchronization, safety, and precision.

- Autonomy Layer: AI agents that plan experiments, interpret results, and update experimental strategies. This is the "cognitive" core of the system.

- Data Layer: Infrastructure for storing, managing, and sharing data, including metadata, uncertainty estimates, and provenance.

This architecture enables a system where, for instance, a materials SDL can autonomously explore composition-spread films to enhance properties like the anomalous Hall effect, making decisions about which elements to compositionally grade and which experimental conditions to explore next [4].

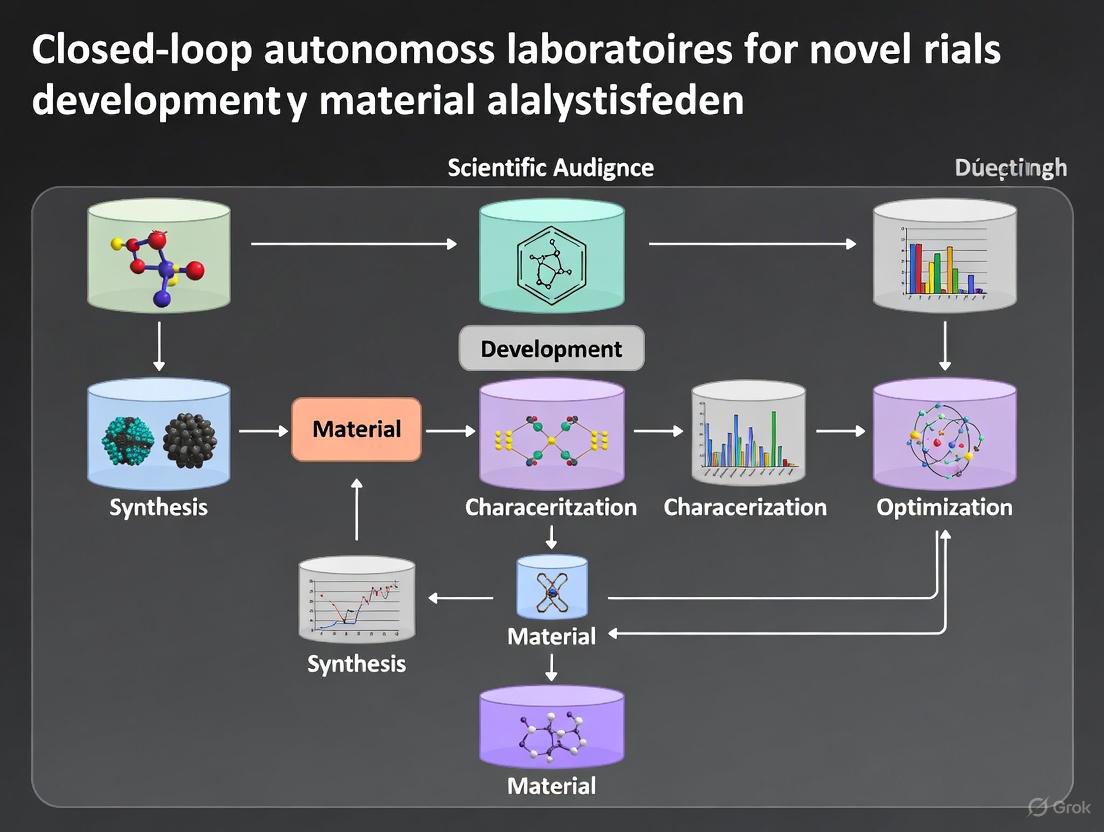

Visualizing the Autonomous Research Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core closed-loop workflow that defines an autonomous research system, integrating the five architectural layers into a continuous cycle of learning and discovery.

Core Components of the Autonomous Research Laboratory

The implementation of full autonomy relies on the seamless integration of several advanced technological components. Each plays a distinct and critical role in the closed-loop system.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

AI and machine learning form the cognitive engine of autonomous laboratories. These systems are responsible for the higher-order decision-making that distinguishes autonomy from simple automation.

Bayesian Optimization: This is a powerful machine learning approach for optimizing expensive-to-evaluate functions. In materials research, it is used to efficiently navigate complex compositional spaces with minimal experiments. For instance, researchers have developed Bayesian optimization methods specifically for composition-spread films, enabling the selection of promising compositions and identifying which elements should be compositionally graded to maximize target properties like the anomalous Hall effect [4]. The algorithm balances exploration of unknown regions with exploitation of known promising areas.

Multi-Objective Optimization and Generative Models: Advanced AI frameworks can balance multiple, often competing objectives simultaneously (e.g., performance, cost, and safety). Generative AI models can also propose entirely novel molecular structures or material compositions that are predicted to possess desired properties, effectively acting as a co-inventor in the discovery process [1] [2].

Robotic Platforms and Automated Instrumentation

The physical layer of the autonomous laboratory consists of robotic platforms that translate digital decisions into physical experiments. These systems provide the precision, reproducibility, and high-throughput capability essential for autonomous operation. Key advancements include:

- Combinatorial Sputtering Systems: These allow for the fabrication of a large number of compounds with varying compositions on a single substrate in a single experiment. This high-throughput approach is critical for rapidly exploring material spaces [4].

- Laser Patterning and Multichannel Probes: These enable rapid, photoresist-free device fabrication and simultaneous measurement of multiple samples, drastically reducing the time between synthesis and characterization [4].

- Modular Robotic Chemistries: Systems that can be reconfigured for different synthesis and processing tasks, providing the flexibility needed for a general-purpose discovery platform [1].

Data Infrastructure and Provenance

The data layer is the foundational memory of the autonomous laboratory. It must capture not only the final results but the complete context of each experiment—the full digital provenance. This includes:

- All reagent identities, volumes, and lot numbers.

- Equipment settings, calibration records, and environmental conditions.

- The chain of decisions made by the AI and the rationale behind them [1]. This comprehensive data capture is essential for reproducibility, model retraining, and extracting maximum knowledge from every experiment.

Quantitative Frameworks for Measuring Autonomy

To move beyond qualitative descriptions, researchers have developed frameworks for quantifying autonomy. One such framework proposes a two-part measure distinguishing between the level of autonomy and the degree of autonomy [5].

Key Autonomy Metrics

This quantitative approach is based on metrics derived from robot task characteristics, recognizing that autonomy is purposive and domain-specific [5].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Quantifying Autonomy

| Metric | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Requisite Capability Set | The set of core capabilities (e.g., perception, planning, manipulation) required to complete a task without external intervention. | Determines the Level of Autonomy – what the system is capable of doing. |

| Reliability | The probability that a system will perform its required function under stated conditions for a specified period of time. | A measure of how trustworthy the system's capabilities are. |

| Responsiveness | The system's ability to complete tasks within a required timeframe, particularly in dynamic environments. | Measures performance quality and suitability for time-critical applications. |

The Level of Autonomy is a binary measure of whether a specific capability exists within the system, while the Degree of Autonomy is a continuous measure (from 0 to 1) of how well that capability performs, based on reliability and responsiveness [5]. This framework provides a more nuanced tool for assessing and comparing autonomous systems beyond the simpler, discrete-level charts used in some domains like automotive driving.

Case Study: Autonomous Discovery of Materials with Enhanced Anomalous Hall Effect

A landmark demonstration of full autonomy in materials research is the closed-loop exploration of composition-spread films for the anomalous Hall effect (AHE) [4]. This case study exemplifies the entire paradigm in action.

Experimental Objective and Setup

The goal was to optimize the composition of a five-element alloy system (Fe, Co, Ni, and two from Ta, W, or Ir) to maximize the anomalous Hall resistivity (({\rho}_{{yx}}^{A})), with a target of over 10 µΩ cm [4]. The autonomous system integrated combinatorial sputtering, laser patterning, and a multichannel measurement probe.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for AHE Experiment

| Material/Reagent | Function/Description | Role in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Fe, Co, Ni (3d elements) | Room-temperature ferromagnetic elements | Form the base ferromagnetic matrix of the alloy system. |

| Ta, W, Ir (5d elements) | Heavy metals with strong spin-orbit coupling | Key additives to enhance the Anomalous Hall Effect by introducing spin-dependent scattering. |

| SiO2/Si Substrate | Thermally oxidized silicon wafer | Amorphous substrate for depositing thin films at room temperature, relevant for practical applications. |

| Custom Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | AI for selecting experimental conditions | The "brain" of the experiment, deciding which composition-spread films to fabricate and measure next. |

Detailed Autonomous Protocol and Workflow

The closed-loop operation followed a precise, iterative protocol with minimal human intervention:

- Initialization: A search space of 18,594 candidate compositions was defined and loaded into the system's "candidates.csv" file [4].

- AI-Driven Proposal: A custom Bayesian optimization algorithm (using the PHYSBO library) selected the most promising two elements to be compositionally graded and proposed L compositions with different mixing ratios [4].

- Automated Fabrication: The system automatically generated an input recipe file for the combinatorial sputtering system to deposit the composition-spread film (1-2 hours) [4].

- Sample Transfer (Human Role): A human transferred the sample from the sputtering system to the laser patterning system. This was one of the only manual steps [4].

- Device Fabrication: The laser patterning system automatically fabricated 13 devices on the film without photoresist (≈1.5 hours) [4].

- Sample Transfer (Human Role): A human transferred the patterned sample to the AHE measurement system [4].

- High-Throughput Characterization: A customized multichannel probe performed simultaneous AHE measurements on all 13 devices at room temperature (≈0.2 hours) [4].

- Automated Data Analysis: A Python program automatically analyzed the raw AHE data and calculated the anomalous Hall resistivity [4].

- Loop Closure: The results were fed back into the Bayesian optimization model, which updated its internal state and generated the next set of proposals, restarting the cycle at step 2 [4].

Outcome and Significance

Through this autonomous closed-loop exploration, the system discovered and validated a novel composition, Fe44.9Co27.9Ni12.1Ta3.3Ir11.7, which achieved a high anomalous Hall resistivity of 10.9 µΩ cm when deposited at room temperature on an SiO2/Si substrate [4]. This success was achieved with a dramatically accelerated experimental pace, demonstrating the power of full autonomy to not only execute tasks but to intelligently guide a research campaign to a successful outcome.

Implications and Future Outlook

The shift to full autonomy in research laboratories promises to fundamentally reshape the scientific enterprise. The implications are profound:

- Radical Acceleration of Discovery: SDLs can reduce time-to-solution by 100 to 1,000 times compared to the status quo, particularly for challenges in decarbonization, next-generation batteries, and sustainable polymers [1].

- Enhanced Reproducibility and Data Quality: The digital provenance and automated recording of every experimental parameter eliminate human error and variability, leading to more robust and reproducible results [1].

- Democratization of Advanced Research: Centralized "SDL Foundries" and distributed modular networks could provide researchers worldwide with access to state-of-the-art experimentation through a cloud-like interface, lowering barriers to entry [1].

- Evolution of the Researcher's Role: As autonomous systems handle routine discovery and optimization, human researchers will be freed to focus on higher-level tasks: asking profound questions, formulating complex problems, designing novel AI architectures, and interpreting the most surprising discoveries generated by the machines [2].

The vision of a "Material Intelligence" is emerging, where AI and robotics are so deeply integrated that they form a new, persistent substrate for discovery—a system that can "read" existing literature, "do" experiments, and "think" of new directions, potentially operating across the globe or even on distant planets [2]. This represents the ultimate expression of the paradigm shift from automation to full autonomy, heralding a new era in research and development.

The field of materials science is undergoing a profound transformation driven by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and robust data infrastructure. These core components form the foundation of closed-loop autonomous laboratories, which aim to bridge the critical gap between computational materials prediction and experimental realization [6]. The traditional approach to materials discovery, often characterized by slow, sequential, and human-intensive experimentation, struggles to keep pace with the vast design spaces identified by high-throughput computational screening. Autonomous laboratories represent a paradigm shift, leveraging intelligent automation to accelerate the synthesis and characterization of novel materials. This whitepaper details the core technical components and methodologies that underpin these self-driving labs, providing a framework for researchers in both materials science and drug development to understand and implement these advanced systems.

Core Architectural Components

The operational efficacy of an autonomous laboratory hinges on the seamless interaction of three core technological pillars: Artificial Intelligence for decision-making, robotics for physical execution, and a unified data infrastructure for knowledge integration.

Artificial Intelligence: The Cognitive Core

AI serves as the cognitive center of the autonomous laboratory, responsible for planning experiments, interpreting results, and guiding the research trajectory without human intervention. Key AI functionalities include:

Experimental Planning and Precursor Selection: Machine learning models, particularly those trained on vast historical datasets extracted from scientific literature using natural-language processing, can propose initial synthesis recipes by assessing target "similarity." This mimics the human approach of basing new experiments on analogies to known materials [6]. For example, the A-Lab utilized such models to generate initial synthesis recipes for novel inorganic powders, achieving a high success rate for targets deemed similar to previously documented compounds.

Active Learning and Bayesian Optimization: When initial recipes fail, active learning algorithms close the loop by proposing improved follow-up experiments. The ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) algorithm, used in the A-Lab, integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed experimental outcomes to predict optimal solid-state reaction pathways [6]. Similarly, specialized Bayesian optimization methods have been developed for high-throughput combinatorial experimentation. One implementation for composition-spread films uses a physics-based Bayesian optimization (PHYSBO) to select which elements to compositionally grade and identifies promising compositions to maximize a target property, such as the anomalous Hall effect [4].

Data Interpretation and Analysis: AI is critical for the rapid analysis of complex characterization data. In the A-Lab, probabilistic machine learning models were employed to extract phase and weight fractions of synthesis products from their X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns. The identified phases were then confirmed with automated Rietveld refinement, allowing for near-real-time assessment of experimental success [6].

Robotics: The Physical Executor

Robotics translate AI-derived decisions into physical actions, handling tasks from sample preparation to characterization. This automation enables continuous, high-throughput operation and manages the physical challenges of handling solid powders, which can vary widely in density, flow behavior, and particle size [6].

- Integrated Robotic Stations: A fully autonomous lab, such as the A-Lab, typically integrates multiple robotic stations. These include a station for dispensing and mixing precursor powders, a second station with robotic arms to load crucibles into box furnaces for heating, and a third station for grinding synthesized samples into fine powders and preparing them for characterization like XRD [6].

- Combinatorial and High-Throughput Systems: Specialized robotic systems enable high-throughput experimentation. For instance, autonomous exploration of composition-spread films involves combinatorial sputtering for deposition, laser patterning for photoresist-free device fabrication, and customized multichannel probes for simultaneous property measurements [4]. This system allowed for the optimization of a five-element alloy for the anomalous Hall effect with minimal human intervention, requiring only sample transfer between systems.

Data Infrastructure: The Unifying Backbone

A unified data infrastructure is the central nervous system that connects AI and robotics, enabling the closed-loop functionality. It manages the vast streams of data generated and ensures that information flows seamlessly between computational and experimental components.

- Orchestration Software: Software platforms like NIMO (NIMS orchestration system) are crucial for supporting autonomous closed-loop exploration [4]. These systems orchestrate a series of programs that control the entire experimental cycle: predicting next experimental conditions from raw measurement data, generating input files for deposition systems, and analyzing results.

- Computational Databases and Knowledge Integration: Successful autonomous platforms leverage large-scale ab initio phase-stability databases, such as the Materials Project and data from Google DeepMind, to identify viable target materials [6]. The integration of this computational data with historical knowledge from text-mined literature and the lab's own growing database of observed pairwise reactions creates a powerful, self-improving knowledge base that informs subsequent experimental iterations.

Table 1: Core Components of an Autonomous Laboratory

| Component | Key Functions | Examples & Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) | Experimental planning, data analysis, active learning optimization | Bayesian optimization (PHYSBO [4]), natural-language processing for precursor selection, probabilistic ML for XRD analysis [6] |

| Robotics & Automation | Sample synthesis, handling, transfer, and preparation | Robotic arms for furnace loading [6], combinatorial sputtering systems [4], automated grinding and characterization stations [6] |

| Data Infrastructure | Data orchestration, knowledge integration, closed-loop control | NIMO orchestration software [4], ab initio databases (Materials Project), literature-derived knowledge graphs [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments that demonstrate the implementation of closed-loop autonomy in materials research.

Protocol 1: Closed-Loop Optimization of Composition-Spread Films

This protocol details the procedure for autonomous discovery of materials with enhanced functional properties, such as the anomalous Hall effect (AHE), using combinatorial thin-film deposition and Bayesian optimization [4].

1. Objective: To autonomously optimize the composition of a five-element alloy system (Fe, Co, Ni, and two from Ta, W, Ir) to maximize the anomalous Hall resistivity (({\rho }_{yx}^{A})).

2. Experimental Workflow:

- Step 1 - Candidate Definition: Define the search space of possible compositions. For example, set concentration ranges for Fe, Co, Ni (10-70 at.%) and the heavy metals (1-29 at.%), resulting in thousands of candidate compositions stored in a "candidates.csv" file.

- Step 2 - AI-Driven Proposal: The orchestration software (NIMO) runs a Bayesian optimization function ("nimo.selection" in "COMBI" mode). This algorithm selects two elements to be compositionally graded and proposes L compositions with different mixing ratios of these two elements at equal intervals, while fixing the others.

- Step 3 - Automated Synthesis: An input recipe file for the combinatorial sputtering system is automatically generated from the AI's proposal. The composition-spread film is deposited on a substrate (e.g., SiO2/Si) at room temperature.

- Step 4 - Automated Characterization & Measurement: The sample is transferred (manually or by robot) to a laser patterning system for photoresist-free device fabrication, and then to a customized multichannel probe for simultaneous AHE measurement of multiple devices at room temperature.

- Step 5 - Automated Data Analysis: A Python program automatically analyzes the raw AHE measurement data and calculates the anomalous Hall resistivity (({\rho }_{yx}^{A})).

- Step 6 - Closed-Loop Feedback: The results are fed back into the "candidates.csv" file, and the process repeats from Step 2. The AI algorithm uses the new data to update its model and propose the next most informative experiment.

3. Key Outcome: Using this protocol, researchers achieved a maximum anomalous Hall resistivity of 10.9 µΩ cm in a Fe44.9Co27.9Ni12.1Ta3.3Ir11.7 amorphous thin film, demonstrating the effectiveness of the closed-loop system for optimizing complex multi-element compositions [4].

Diagram 1: Closed-loop optimization for composition-spread films.

Protocol 2: Autonomous Synthesis of Novel Inorganic Powders

This protocol outlines the workflow used by the A-Lab for the solid-state synthesis of novel inorganic compounds, integrating diverse data sources and active learning [6].

1. Objective: To synthesize target inorganic powder materials identified from computational databases (e.g., Materials Project) as air-stable and on or near the thermodynamic convex hull.

2. Experimental Workflow:

- Step 1 - Target Identification: Select target materials predicted to be stable using large-scale ab initio phase-stability data. Filter for compounds that are not expected to react with O2, CO2, and H2O to ensure compatibility with open-air handling.

- Step 2 - Literature-Inspired Recipe Generation: Generate up to five initial synthesis recipes using a machine learning model that assesses target "similarity" through natural-language processing of a large database of literature syntheses. A second ML model proposes a synthesis temperature based on historical heating data.

- Step 3 - Robotic Synthesis Execution: A robotic arm dispenses and mixes precursor powders into an alumina crucible. Another robotic arm loads the crucible into a box furnace for heating.

- Step 4 - Robotic Characterization and Analysis: After cooling, a robot transfers the sample to a station where it is ground into a fine powder and measured by XRD. Probabilistic ML models analyze the XRD pattern to identify phases and estimate weight fractions, which are confirmed via automated Rietveld refinement.

- Step 5 - Active Learning Optimization: If the target yield is below a threshold (e.g., 50%), the active learning algorithm (ARROWS3) takes over. It uses the lab's growing database of observed pairwise reactions and computed reaction energies from the Materials Project to propose a new synthesis route with a higher probability of success, avoiding intermediates with low driving forces to form the target.

- Step 6 - Iteration: Steps 3-5 are repeated until the target is obtained as the majority phase or all possible recipes are exhausted.

3. Key Outcome: In a 17-day continuous run, the A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 out of 58 novel target compounds, a 71% success rate, demonstrating the power of integrating computation, historical knowledge, and robotics [6].

Diagram 2: Autonomous synthesis workflow for inorganic powders.

Quantitative Performance Data

The performance of autonomous laboratories is quantifiable through metrics such as success rates, acceleration factors, and optimization efficiency. The data below, derived from operational systems, underscores the transformative impact of this integrated approach.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Autonomous Experimentation Systems

| System / Platform | Key Performance Metric | Result / Outcome | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| A-Lab [6] | Success Rate in Novel Material Synthesis | 71% (41/58 compounds synthesized) | 17-day continuous operation targeting novel oxides and phosphates. |

| A-Lab [6] | Potential Improved Success Rate | 78% (with improved computations) | Analysis of failure modes suggested achievable improvements. |

| Combinatorial AHE Optimization [4] | Optimized Property (Anomalous Hall Resistivity) | 10.9 µΩ cm | Achieved in a FeCoNiTaIr amorphous thin film via closed-loop Bayesian optimization. |

| Closed-Loop System [4] | Experiment Cycle Time | Synthesis: 1-2 hrs, Patterning: 1.5 hrs, Measurement: 0.2 hrs | Timeline for one cycle in the autonomous exploration of composition-spread films. |

| Data Center Robotics Market [7] | Projected Global Market Growth (CAGR 2024-2030) | 21.6% | Reflects broader adoption and investment in automated infrastructure. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The implementation of the experimental protocols described relies on a suite of specific reagents, software, and hardware.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Autonomous Materials Research

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | Chemical Reagent | High-purity starting materials for solid-state synthesis of target inorganic compounds [6]. |

| Alumina Crucibles | Laboratory Consumable | Containment vessels for powder samples during high-temperature reactions in box furnaces [6]. |

| SiO2/Si Substrates | Substrate | Thermally oxidized silicon wafers used as substrates for the deposition of composition-spread thin films [4]. |

| NIMO (NIMS Orchestration System) | Software | Orchestration software for managing autonomous closed-loop exploration, including AI proposal generation and data analysis [4]. |

| PHYSBO | Software / Algorithm | Optimization tools for physics-based Bayesian optimization, used for selecting experimental conditions [4]. |

| Combinatorial Sputtering System | Hardware / Instrument | Deposition system for fabricating composition-spread films with graded elemental compositions [4]. |

| Automated XRD System | Hardware / Instrument | Integrated with robotic sample handling for high-throughput phase identification and analysis of synthesis products [6]. |

The field of materials science and chemistry is undergoing a profound transformation with the advent of Self-Driving Labs (SDLs). These autonomous systems represent the integration of automated experimental workflows in the physical world with algorithm-selected experimental parameters in the digital world [8]. The core value proposition of SDLs lies in their ability to navigate complex and exponentially expanding reaction spaces with an efficiency unachievable through human-led manual experimentation, thereby enabling researchers to explore larger and more complicated experimental systems [8]. This technological evolution mirrors similar advancements in other scientific domains, such as the Human-AI Collaborative Refinement Process used for categorizing surgical feedback, which demonstrates how artificial intelligence can enhance pattern discovery and prediction beyond human capabilities alone [9].

The classification of autonomy levels in SDLs is not merely an academic exercise but a critical framework for comparing systems, guiding development priorities, and understanding the operational requirements for different research applications. Just as performance metrics are essential for evaluating clinical decision support systems in healthcare [10], a standardized approach to classifying SDL autonomy provides researchers with the necessary tools to select appropriate systems for their specific experimental challenges. This classification system becomes increasingly important as SDLs evolve from simple automated tools toward partners in scientific discovery, capable of defining and pursuing novel research objectives without direct human intervention.

A Framework for Classifying SDL Autonomy Levels

Defining the Spectrum of Autonomy

The autonomy of self-driving labs can be systematically categorized into four distinct levels, each representing a different degree of human involvement and AI-driven decision-making. This classification is fundamental to understanding both the current capabilities and future trajectory of autonomous experimentation systems [8].

Piecewise Systems (Algorithm-Guided Studies) represent the foundational level of SDL autonomy. In these systems, a complete separation exists between the physical platform and the experimental selection algorithm. A human scientist must manually collect experimental data and transfer it to the algorithm, which then selects the next experimental conditions. These selected conditions must subsequently be transferred back to the physical platform by the researcher for testing [8]. This level of autonomy is particularly useful for informatics-based studies, high-cost experiments, and systems with low operational lifetimes, as human scientists can manually filter out erroneous conditions and correct system issues as they arise [8]. However, this approach is typically impractical for studies requiring dense data spaces, such as high-dimensional Bayesian optimization or reinforcement learning.

Semi-Closed-Loop Systems represent an intermediate stage where human intervention is still required for certain steps in the experimental process, but direct communication exists between the physical platform and the experiment-selection algorithm. Typically, researchers must either collect measurements after the experiment or reset aspects of the experimental system before studies can continue [8]. This approach is most applicable to batch or parallel processing of experimental conditions, studies requiring detailed offline measurement techniques, and highly complex systems that cannot conduct experiments continuously in series. Semi-closed-loop systems generally offer higher efficiency than piecewise strategies while still accommodating measurement techniques not amenable to inline integration, though they often remain ineffective for generating very large datasets [8].

Closed-Loop Systems represent a significant advancement in autonomy, requiring no human interference to carry out experiments. In these systems, the entirety of experimental conduction, system resetting, data collection and analysis, and experiment selection occurs without any human intervention or interfacing [8]. Although challenging to implement, closed-loop systems offer extremely high data generation rates and enable otherwise inaccessible data-greedy algorithms such as reinforcement learning and Bayesian optimization [8]. A prominent example is the A-Lab for solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders, which integrates robotics with computations, historical data, machine learning, and active learning to plan and interpret experiments autonomously [6].

Self-Motivated Experimental Systems represent the highest conceptual level of autonomy, where platforms define and pursue novel scientific objectives without user direction. These systems merge closed-loop capabilities with autonomous identification of novel synthetic goals, thereby completely removing human influence from the research direction-setting process [8]. While no platform has yet achieved this level of autonomy, it represents the theoretical endpoint for replacing human-guided scientific discovery with AI-driven research entities.

Quantitative Metrics for Comparing SDL Performance

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Self-Driving Labs

| Metric Category | Specific Measures | Description | Application Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of Autonomy | Piecewise, Semi-Closed Loop, Closed-Loop, Self-Motivated | Classification based on required human intervention level | Higher autonomy enables data-greedy algorithms but increases implementation complexity |

| Operational Lifetime | Demonstrated Unassisted/Assisted, Theoretical Unassisted/Assisted | Duration of continuous operation without human intervention | Critical for budgeting data, labor, and platform generation; reported values should specify chemical source limitations [8] |

| Throughput | Theoretical vs. Demonstrated Samples/Hour | Rate of experimental iteration and data generation | Highly dependent on reaction times and characterization methods; non-destructive characterization enables higher effective throughput [8] |

| Experimental Precision | Standard Deviation of Replicates | Reproducibility of experimental results under identical conditions | High precision is essential for effective optimization; imprecise data generation cannot be compensated for by high throughput alone [8] |

| Material Usage | Total Quantity, High-Value Materials, Hazardous Materials | Consumption of chemical resources per experiment | Lower volumes expand explorable parameter space and reduce costs; particularly important for expensive or environmentally harmful materials [8] |

Table 2: Autonomy Level Comparison with Implementation Requirements

| Autonomy Level | Human Role | Data Transfer Mechanism | Suitable Experiment Types | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piecewise | Manually transfers data and conditions between platform and algorithm | Manual human intervention | Informatics studies, high-cost experiments, low-lifetime systems | Impractical for dense data spaces, limited scalability [8] |

| Semi-Closed-Loop | Interferes with specific steps (measurement collection or system resetting) | Direct platform-algorithm communication with human gaps | Batch processing, offline measurements, non-continuous systems | Limited very large dataset generation [8] |

| Closed-Loop | No intervention required during operation | Fully automated data and instruction transfer | Continuous experimentation, data-greedy algorithms (BO, RL) | Challenging to create, requires robust automation [8] |

| Self-Motivated | Defines overarching research goals | Fully autonomous goal-setting and experimentation | Novel scientific discovery without human direction | Theoretical stage, not yet demonstrated [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Autonomous Materials Research

The A-Lab Workflow for Novel Materials Synthesis

The A-Lab represents a state-of-the-art implementation of a highly autonomous materials research platform, specifically designed for the solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders. Its operational workflow provides a template for how autonomous systems can integrate various AI components and robotic systems to accelerate materials discovery [6].

The process begins with Target Identification and Validation. The A-Lab receives target materials predicted to be stable through large-scale ab initio phase-stability data from computational resources like the Materials Project and Google DeepMind. To ensure practical synthesizability, the system only considers targets predicted to be air-stable, meaning they will not react with O₂, CO₂, or H₂O during handling in open air [6]. This integration of computational screening with practical constraints demonstrates how autonomous systems can balance theoretical predictions with experimental realities.

The second stage involves AI-Driven Synthesis Planning. For each proposed compound, the A-Lab generates up to five initial synthesis recipes using a machine learning model that assesses target "similarity" through natural-language processing of a large database of syntheses extracted from the literature [6]. This approach mimics how human researchers base initial synthesis attempts on analogies to known related materials. A synthesis temperature is then proposed by a second ML model trained on heating data from the literature [6]. This dual-model approach reflects the complex, multi-factor decision-making typically associated with expert human researchers.

The Robotic Execution Phase utilizes three integrated stations for sample preparation, heating, and characterization. The preparation station dispenses and mixes precursor powders before transferring them into alumina crucibles. A robotic arm then loads these crucibles into one of four available box furnaces for heating. After cooling, another robotic arm transfers samples to the characterization station, where they are ground into fine powder and measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD) [6]. This physical automation enables continuous operation over extended periods—17 days in the reported study—far exceeding typical human endurance.

The Analysis and Active Learning Cycle represents the most advanced aspect of the autonomy. Synthesis products are characterized by XRD, with two ML models working together to analyze patterns. The phase and weight fractions of synthesis products are extracted using probabilistic ML models trained on experimental structures, with patterns for novel materials simulated from computed structures and corrected to reduce density functional theory errors [6]. When initial recipes fail to produce >50% yield, the system employs an active learning algorithm called ARROWS³ (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) that integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed synthesis outcomes to predict improved solid-state reaction pathways [6].

Implementation of Human-AI Collaboration

The A-Lab exemplifies how human expertise can be encoded into autonomous systems while still leveraging AI's pattern recognition capabilities. This approach mirrors the Human-AI Collaborative Refinement Process demonstrated in surgical feedback analysis, which uses unsupervised machine learning with human refinement to discover meaningful categories from complex datasets [9]. In the A-Lab context, this collaboration manifests in several ways:

The system uses Historical Knowledge Integration through natural language processing of existing literature, effectively distilling decades of human research experience into actionable synthesis strategies [6]. This allows the autonomous system to benefit from the collective knowledge of the materials science community without requiring direct human consultation for each decision.

The Active Learning with Thermodynamic Grounding demonstrates how AI can extend beyond human capabilities. The ARROWS³ algorithm uses two key hypotheses: (1) solid-state reactions tend to occur between two phases at a time (pairwise), and (2) intermediate phases that leave only a small driving force to form the target material should be avoided [6]. These principles, while grounded in materials science theory, are systematically applied by the AI across a much broader range of reactions than would be practical for human researchers.

The system continuously builds a Database of Pairwise Reactions observed in its experiments—88 unique pairwise reactions were identified during its initial operation [6]. This growing knowledge base allows the system to progressively improve its predictions and avoid repeating unsuccessful pathways, demonstrating how autonomous systems can build on their experience in ways that transcend individual human memory and recall limitations.

Visualization of SDL Architectures and Workflows

The Autonomous Research Loop

Diagram 1: The closed-loop autonomous research workflow as implemented in systems like the A-Lab, showing the iterative cycle of planning, execution, analysis, and learning that enables continuous materials discovery without human intervention.

SDL Autonomy Classification Framework

Diagram 2: The spectrum of SDL autonomy levels, illustrating the decreasing human involvement and increasing integration between digital algorithms and physical platforms as systems progress from piecewise to self-motivated operation.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Autonomous Materials Synthesis

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Materials Synthesis

| Reagent/Material Category | Specific Examples | Function in Autonomous Workflow | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Materials | Oxide and phosphate powders (e.g., Fe₂O₃, Ca₃(PO₄)₂) | Source compounds for solid-state reactions | Must exhibit appropriate reactivity, purity, and handling characteristics for robotic dispensing [6] |

| Sample Containers | Alumina crucibles | Hold precursor mixtures during high-temperature processing | Must withstand repeated heating cycles and be compatible with robotic handling systems [6] |

| Characterization Standards | Silicon standard for XRD calibration | Ensure accurate phase identification and quantification | Critical for maintaining data quality across extended autonomous operation [6] |

| Robotic System Components | Robotic arms, powder dispensers, milling apparatus | Enable automated sample preparation and transfer | Reliability and maintenance requirements directly impact operational lifetime metrics [6] |

| Heating Systems | Box furnaces with robotic loading/unloading | Provide controlled thermal environments for reactions | Multiple units enable parallel processing; temperature uniformity is critical for reproducibility [6] |

| Analysis Instruments | X-ray diffractometers with automated sample changers | Characterize synthesis products and quantify yields | Throughput must align with synthesis capacity to avoid bottlenecks [6] |

The classification of Self-Driving Labs across the autonomy spectrum from assisted operation to AI researchers provides an essential framework for understanding and advancing this transformative technology. As demonstrated by systems like the A-Lab, which successfully synthesized 41 of 58 novel target compounds through continuous autonomous operation [6], the integration of computational screening, historical knowledge, machine learning, and robotics represents a paradigm shift in materials research methodology. The progression from piecewise to closed-loop systems highlights both the current capabilities and future potential of SDLs to dramatically accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel materials.

The critical importance of standardized performance metrics—including degree of autonomy, operational lifetime, throughput, experimental precision, and material usage [8]—cannot be overstated for meaningful comparison and selection of SDL platforms. These metrics enable researchers to match system capabilities with experimental requirements, ensuring that the unique challenges of different research questions are addressed with appropriate technological solutions. As the field continues to evolve toward fully self-motivated research systems, this classification framework will serve as both a roadmap for development and a benchmark for assessing progress in the ongoing integration of artificial intelligence with scientific discovery.

The Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycle serves as the fundamental operational engine driving modern scientific discovery, particularly in fields such as drug development and novel materials research. This iterative process involves designing new molecular entities or materials, synthesizing them, testing their properties, and analyzing the results to inform the next design iteration [11] [12]. Within the context of autonomous laboratories for novel materials research, the DMTA cycle transforms from a human-driven process to a fully automated, closed-loop system capable of continuous, unsupervised operation and learning [6] [13]. This evolution represents a paradigm shift in research methodology, enabling unprecedented acceleration of discovery timelines through the integration of artificial intelligence, robotics, and data science.

The transition toward autonomous experimentation addresses significant bottlenecks in traditional research approaches. While computational methods can identify promising new materials at scale, their experimental realization has traditionally been challenging and time-consuming [6]. Autonomous laboratories bridge this gap by combining automated physical hardware for sample handling and synthesis with intelligent software that plans experiments and interprets results. This convergence creates a virtuous cycle where digital tools enhance physical processes, and feedback from these improved processes informs further digital advancements [12].

Core Principles of the DMTA Cycle

The DMTA framework provides a structured approach to research and development, breaking down the complex process of optimization into manageable, iterative phases. Each phase addresses specific aspects of the discovery process, from conceptual design through experimental validation to data interpretation.

Table: The Four Phases of the DMTA Cycle

| Phase | Core Objective | Key Activities | Primary Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Define what to make and how to make it | Generative AI, retrosynthetic analysis, building block identification [11] [12] | Target compound structures, synthetic routes [12] |

| Make | Execute physical synthesis | Reaction setup, purification, characterization, sample preparation [11] | Synthesized compounds, analytical data [12] |

| Test | Evaluate compound properties | Biological assays, physicochemical measurements, analytical characterization [12] [13] | Experimental data on properties and performance [13] |

| Analyze | Derive insights from data | Data interpretation, pattern recognition, statistical analysis [12] [13] | Actionable insights, next-step hypotheses [13] |

In traditional research environments, the DMTA cycle faces significant implementation challenges that limit its effectiveness. These include sequential rather than parallel execution of phases, creating significant delays; data integration barriers between different specialized teams; and resource coordination inefficiencies that result in suboptimal utilization of both human expertise and analytical capabilities [14] [13]. The transition to autonomous laboratories addresses these limitations through digital integration and automation.

DMTA in Autonomous Materials Research

The application of the DMTA cycle within autonomous laboratories represents the cutting edge of materials research methodology. These systems combine robotics, artificial intelligence, and extensive data integration to create self-driving laboratories that can operate continuously with minimal human intervention.

The A-Lab Platform for Inorganic Materials

The A-Lab, an autonomous laboratory for solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders, exemplifies the implementation of closed-loop DMTA for novel materials discovery. This platform uses computations, historical data, machine learning, and active learning to plan and interpret experiments performed using robotics [6]. Over 17 days of continuous operation, the A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 of 58 novel target compounds identified using large-scale ab initio phase-stability data from the Materials Project and Google DeepMind [6].

The autonomous discovery pipeline followed by the A-Lab integrates multiple advanced technologies:

The A-Lab's workflow begins with target materials screened for stability and air compatibility. For each compound, the system generates up to five initial synthesis recipes using machine learning models trained through natural-language processing of a large database of syntheses extracted from literature [6]. This mimics the human approach of basing initial synthesis attempts on analogy to known related materials. If these literature-inspired recipes fail to produce the target with sufficient yield, the system employs an active learning algorithm called ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) that integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed synthesis outcomes to predict improved solid-state reaction pathways [6].

The physical implementation of the A-Lab consists of three integrated stations for sample preparation, heating, and characterization, with robotic arms transferring samples and labware between them. The preparation station dispenses and mixes precursor powders before transferring them into crucibles. A robotic arm from the heating station loads these crucibles into one of four available box furnaces. After cooling, another robotic arm transfers samples to the characterization station, where they are ground into fine powder and measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD) [6]. This integrated hardware system enables continuous 24/7 operation without human intervention.

Multi-Agent AI Systems for Drug Discovery

In pharmaceutical research, agentic AI systems represent another approach to DMTA automation. The Tippy framework employs five specialized AI agents that work collaboratively to automate the drug discovery process [13]:

This multi-agent architecture enables parallel execution of DMTA phases that would traditionally be performed sequentially. The Molecule Agent generates molecular structures and converts chemical descriptions into standardized formats. The Lab Agent manages HPLC analysis workflows, synthesis procedures, and laboratory job execution. The Analysis Agent processes job performance data and extracts statistical insights, while the Report Agent generates documentation. The Safety Guardrail Agent provides critical oversight, validating all requests for potential safety violations before execution [13]. This specialized approach allows each agent to develop deep expertise in its domain while maintaining seamless coordination across the entire DMTA cycle.

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

AI-Enhanced Synthesis Planning

Computer-Assisted Synthesis Planning (CASP) has evolved from early rule-based expert systems to data-driven machine learning models [11]. Modern CASP methodologies involve both single-step retrosynthesis prediction, which proposes individual disconnections, and multi-step synthesis planning, which chains these steps into complete routes using search algorithms like Monte Carlo Tree Search or A* Search [11].

For the "Make" phase, automated synthesis platforms require precise experimental protocols. The A-Lab employs the following general methodology for solid-state synthesis:

Precursor Preparation: Precursors are dispensed by an automated system according to stoichiometric calculations and mixed thoroughly using a ball mill or similar automated mixing system.

Reaction Execution: Mixed powders are transferred to alumina crucibles and loaded into box furnaces using robotic arms. Heating profiles are applied according to predicted optimal temperatures from ML models trained on literature data [6].

Product Characterization: Synthesized materials are ground into fine powders and analyzed by X-ray diffraction. Phase and weight fractions of synthesis products are extracted from XRD patterns by probabilistic ML models trained on experimental structures [6].

Iterative Optimization: When initial synthesis recipes fail to produce >50% yield, active learning algorithms propose improved follow-up recipes based on observed reaction pathways and thermodynamic calculations [6].

Active Learning and Bayesian Optimization

Closed-loop autonomous systems employ sophisticated active learning approaches to optimize experimental outcomes. The ARROWS3 algorithm used in the A-Lab operates on two key hypotheses: (1) solid-state reactions tend to occur between two phases at a time (pairwise), and (2) intermediate phases that leave only a small driving force to form the target material should be avoided [6].

The CAMEO (Autonomous System for Materials Exploration and Optimization) platform implements on-the-fly closed-loop autonomous materials discovery using Bayesian active learning [15]. This approach enables the system to simultaneously address phase mapping and property optimization, with each cycle taking seconds to minutes. The methodology involves:

Hypothesis Definition: The AI defines testable hypotheses based on existing data and theoretical predictions.

Experiment Selection: Using Bayesian optimization, the system selects experiments that maximize information gain while minimizing resource consumption.

Rapid Characterization: High-throughput techniques like synchrotron XRD provide immediate feedback on experimental outcomes.

Model Updating: Results inform updates to the AI's predictive models, creating an increasingly accurate representation of the materials landscape [15].

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Autonomous Materials Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Oxides | Binary and ternary metal oxides (e.g., Li₂O, Fe₂O₃, P₂O₅) | Provide elemental components for solid-state reactions of oxide materials [6] |

| Phosphate Precursors | NH₄H₂PO₄, (NH₄)₂HPO₄, metal phosphates | Source of phosphorus for phosphate compound synthesis [6] |

| Building Blocks for Organic Synthesis | Carboxylic acids, amines, boronic acids, halides [11] | Provide functional handles for carbon-carbon bond formation and scaffold diversification [11] |

| Catalysts | Palladium catalysts for cross-coupling (e.g., Suzuki, Buchwald-Hartwig) [11] | Enable key bond-forming reactions in complex molecule synthesis [11] |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Autonomous DMTA implementations have demonstrated significant improvements in research efficiency and success rates. The A-Lab achieved a 71% success rate (41 of 58 compounds) in synthesizing novel inorganic materials over 17 days of continuous operation [6]. Analysis revealed this success rate could be improved to 74% with minor modifications to the decision-making algorithm, and further to 78% with enhanced computational techniques [6].

The efficiency gains stem from multiple factors:

Table: Efficiency Metrics in Autonomous DMTA Cycles

| Metric | Traditional DMTA | Autonomous DMTA | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle Time | Weeks to months [13] | Continuous operation with cycles of "seconds to minutes" [15] | 10-100x acceleration [15] |

| Success Rate for Novel Materials | Highly variable, often <50% for first attempts | 71% for first attempts on novel compounds [6] | ~40% improvement for challenging targets [6] |

| Experimental Throughput | Limited by human capacity | 355 recipes tested in 17 days [6] | 20+ experiments per day [6] |

| Resource Utilization | Sequential use of instruments | Parallel operation of multiple furnaces and characterization tools [6] | 3-4x better equipment utilization [6] |

For the 17 targets not obtained by the A-Lab, analysis revealed specific failure modes: sluggish reaction kinetics (11 targets), precursor volatility (2 targets), amorphization (2 targets), and computational inaccuracy (2 targets) [6]. This detailed failure analysis provides actionable insights for improving both computational predictions and experimental approaches in future iterations.

Implementation Challenges and Future Directions

While autonomous DMTA cycles offer tremendous potential, several challenges remain in their widespread implementation. Effective autonomous systems require high-quality, FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles to build robust predictive models [11]. The "analysis gap" between single-step model performance metrics and overall route-finding success represents another significant challenge [11].

Future developments in autonomous DMTA cycles will likely focus on several key areas:

Enhanced Human-AI Collaboration: Systems will evolve toward more natural interfaces, potentially including "Chemical ChatBots" that allow researchers to interact with AI systems through conversational dialogue [11].

Cross-Domain Knowledge Transfer: Techniques that enable learning across different materials classes and synthesis methodologies will reduce the need for extensive training data in new domains.

Integrated Multi-Scale Modeling: Combining quantum calculations, molecular dynamics, and macro-scale process modeling will improve prediction accuracy across different length and time scales.

Adaptive Experimentation: Systems that can dynamically adjust their hypothesis-testing strategies based on real-time results and changing research priorities.

The evolution toward fully autonomous research systems represents a fundamental transformation in scientific methodology. By closing the DMTA loop through integrated AI and robotics, these systems enable a virtuous cycle of continuous learning and optimization that dramatically accelerates the pace of discovery while potentially increasing reproducibility and reducing costs [6] [12] [13]. As these technologies mature, they promise to redefine the roles of human researchers, freeing them from routine experimental tasks to focus on higher-level scientific questions and strategic direction.

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI), launched in 2011, is a multi-agency U.S. initiative with a bold vision: to discover, manufacture, and deploy advanced materials at twice the speed and a fraction of the cost of traditional methods [1] [16]. While substantial progress has been made through computational tools and data infrastructures, a critical barrier remains: empirical validation. Physical experimentation, often reliant on manual, low-throughput processes, has become the primary bottleneck, hampering the overall pace of materials innovation [1].

Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs) represent a transformative pathway to overcome this limitation. These systems integrate robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and autonomous experimentation into a closed-loop, capable of rapid hypothesis generation, execution, and refinement without human intervention [1]. This technical guide explores the strategic imperative of aligning SDL development with the MGI framework, detailing how this synergy is essential for creating a national Autonomous Materials Innovation Infrastructure that can secure U.S. leadership in critical technology sectors [1].

The MGI Strategic Framework: Creating a Conducive Environment for SDLs

The MGI has evolved to explicitly recognize and address the experimental gap. Its 2021 strategic plan outlines three core goals that create a conducive policy and technical environment for SDLs [16]:

- Unify the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII): The MII is a framework that integrates advanced modeling, computational and experimental tools, and quantitative data. SDLs are poised to become the experimental pillar of this infrastructure [1] [16] [17].

- Harness the power of materials data: SDLs inherently generate vast amounts of high-quality, machine-readable data, including detailed digital provenance (metadata), which is crucial for building robust, reusable data resources [1] [16].

- Educate, train, and connect the materials R&D workforce: The operation and management of SDLs require a new skill set, fostering a workforce proficient in data science, robotics, and AI, alongside traditional materials science [16].

Furthermore, the MGI has spurred flagship funding programs that directly support the SDL ecosystem, including the NSF's Designing Materials to Revolutionize and Engineer our Future (DMREF) and Materials Innovation Platforms (MIP), which provide large-scale scientific ecosystems for accelerated discovery [17].

The Technical Architecture of Self-Driving Labs

At its core, an SDL is a closed-loop system that automates the entire Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycle [18]. Its technical architecture can be decomposed into five interlocking layers, each with distinct components and functions essential for autonomous operation.

Table 1: The Five-Layer Architecture of a Self-Driving Lab

| Layer | Key Components | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Actuation Layer | Robotic arms, powder dispensers, syringe pumps, box furnaces, milling modules | Executes physical tasks for synthesis and processing [1] [6]. |

| Sensing Layer | X-ray diffraction (XRD), spectrometers, microscopes, environmental sensors | Captures real-time data on material properties and process conditions [1] [6]. |

| Control Layer | Laboratory Operating System, schedulers, safety interlocks, device drivers | Orchestrates and synchronizes hardware operations for precise experimental sequences [1]. |

| Autonomy Layer | Bayesian optimization, reinforcement learning, active learning, large language models (LLMs) | Plans experiments, interprets outcomes, and updates the research strategy adaptively [1] [6]. |

| Data Layer | Cloud databases, data lakes, metadata schemas, ontologies, APIs | Manages, stores, and provides access to experimental data, models, and provenance information [1]. |

The autonomy layer is what distinguishes an SDL from simple automation. Rather than executing a fixed script, the AI in this layer uses algorithms like Bayesian optimization and reinforcement learning to decide which experiment to perform next based on all prior results, efficiently navigating complex, multidimensional design spaces [1]. The integration of large language models (LLMs) further enhances this by allowing researchers to interact with the SDL using natural language or by enabling the system to parse scientific literature to inform its initial experimental plans [1].

Exemplar SDL Implementation: The A-Lab for Novel Inorganic Materials

The A-Lab, developed and reported in Nature in 2023, serves as a premier case study for a fully autonomous solid-state synthesis laboratory [6]. Its workflow and performance metrics provide a concrete template for how SDLs align with and advance the goals of the MGI.

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

The A-Lab's operation exemplifies a complete MGI approach, integrating computation, data, and autonomous experimentation into a seamless, iterative workflow [6]:

- Target Identification: Targets are novel, air-stable inorganic powders identified through large-scale ab initio phase-stability calculations from databases like the Materials Project and Google DeepMind.

- Literature-Inspired Recipe Generation: A natural-language processing model, trained on a vast corpus of historical synthesis literature, proposes initial precursor combinations and a heating temperature.

- Robotic Execution:

- Preparation: Precursor powders are automatically dispensed and mixed by a robotic arm and transferred to an alumina crucible.

- Heating: The crucible is loaded into one of four box furnaces for firing.

- Characterization: After cooling, the sample is ground and analyzed by X-ray Diffraction (XRD).

- Autonomous Data Analysis: The XRD pattern is analyzed by machine learning models to identify phases and quantify yield via automated Rietveld refinement.

- Active Learning Optimization: If the target yield is below a threshold (e.g., 50%), the ARROWS³ active learning algorithm proposes a new recipe. This algorithm uses a growing database of observed solid-state reactions and thermodynamic data from the Materials Project to avoid intermediates with low driving forces and prioritize more favorable reaction pathways.

Performance and Quantitative Outcomes

Over 17 days of continuous operation, the A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 out of 58 novel target compounds, demonstrating a 71% success rate in realizing computationally predicted materials [6]. This result validates the effectiveness of AI-driven platforms and high-throughput ab initio calculations for identifying synthesizable materials.

Table 2: A-Lab Experimental Outcomes and Failure Analysis

| Metric | Value | Context / Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Operation Duration | 17 days | Continuous, unattended operation [6]. |

| Novel Targets Attempted | 58 | Compounds with no prior synthesis reports [6]. |

| Successfully Synthesized | 41 | Demonstrates high fidelity of computational predictions [6]. |

| Success Rate | 71% | Could be improved to 78% with enhanced algorithms [6]. |

| Primary Failure Mode | Slow kinetics (11/17 failures) | Reactions with low driving force (<50 meV/atom) [6]. |

| Other Failure Modes | Precursor volatility, amorphization, computational inaccuracy | Highlights areas for improvement in SDL design [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The operation of an SDL like the A-Lab relies on a suite of integrated hardware and software "reagents" that enable its autonomous function.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for an SDL

| Item / Solution | Function | Role in the Autonomous Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Robotic Arm | Sample and labware transfer between stations. | Physically connects the synthesis, heating, and characterization modules [6]. |

| Precursor Powder Library | Raw chemical ingredients for solid-state reactions. | The "chemical space" the SDL can explore; must be compatible with automated dispensing [6]. |

| Automated Box Furnaces | Provide controlled high-temperature environments for reactions. | Enable unattended heating and cooling cycles for solid-state synthesis [6]. |

| X-ray Diffractometer (XRD) | Provides crystal structure and phase composition data. | The primary sensor for characterizing synthesis output; data is fed directly to AI for analysis [6]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | AI for navigating complex parameter spaces. | The core of the autonomy layer; decides the next best experiment to maximize learning or performance [1]. |

| ARROWS³ Active Learning | Plans optimized solid-state reaction pathways. | Uses thermodynamic data and observed reactions to avoid kinetic traps and improve yield [6]. |

Strategic Deployment Models for National Impact

To fully integrate SDLs into the MGI and achieve national-scale impact, several deployment models are being advanced [1]:

- Centralized SDL Foundries: These facilities, housed in national laboratories or large consortia, would concentrate high-end, specialized, or hazardous experimentation capabilities. They would function as national user facilities, allowing researchers to submit digital workflows for remote execution, thus providing broad access to cutting-edge tools [1].

- Distributed Modular Networks: This model involves deploying lower-cost, modular SDL platforms in individual university or industrial labs. These distributed systems offer flexibility and local ownership. When connected via cloud platforms and shared metadata standards, they can function as a "virtual foundry," pooling data and accelerating collective progress across the community [1].

- Hybrid Approach: A layered model, analogous to cloud computing, where preliminary research is conducted on local distributed SDLs, and more complex, resource-intensive tasks are escalated to centralized foundries. This maximizes both accessibility and overall efficiency [1].

The alignment of Self-Driving Labs with the Materials Genome Initiative represents a paradigm shift in materials science. SDLs provide the missing experimental pillar to the MGI vision, transforming physical experimentation from a manual, low-throughput art into a programmable, scalable, and data-rich infrastructure [1]. The demonstrated success of platforms like the A-Lab in rapidly realizing novel materials proves the viability of this approach.

Fully realizing this potential requires continued investment in the Materials Innovation Infrastructure, including the development of open data standards, shared software APIs, and a trained workforce capable of operating at the intersection of materials science, robotics, and AI [1] [17]. By strategically deploying SDLs through centralized and distributed models, the MGI can achieve its foundational goal: dramatically accelerating the discovery and deployment of advanced materials to address pressing challenges in energy, security, and economic competitiveness.

How Autonomous Labs Work: The DMTA Cycle and Breakthrough Applications

In the pursuit of accelerated materials discovery, closed-loop autonomous laboratories represent a paradigm shift. These self-driving labs iteratively plan, execute, and analyze experiments with minimal human intervention. The Spatial Data Lab (SDL) project provides a powerful, spatiotemporal-data-driven architectural blueprint for such systems [19]. This whitepaper details a five-layer architecture for an SDL, deconstructing its core components from physical actuation to data-driven intelligence, specifically contextualized for novel materials research.

The Spatial Data Lab (SDL) is a collaborative initiative aimed at advancing applied research through an open-source infrastructure for data linkage, analysis, and collaboration [19]. When applied to autonomous materials research, an SDL transcends being a mere data repository; it becomes an active, reasoning system. It integrates experimental synthesis, high-throughput characterization, and multiscale simulation data to guide the discovery of materials with targeted properties.

The core challenge lies in harmonizing diverse, complex data streams—from atomistic simulations to panoramic electron microscopy images [20]—into a coherent, actionable knowledge graph. The five-layer architecture proposed herein addresses this by creating a reproducible, replicable, and expandable (RRE) framework [19], essential for establishing a robust foundation for autonomous scientific discovery.

The Five-Layer Architecture: A Detailed Breakdown

The architecture of an SDL for materials design is stratified into five distinct yet interconnected layers, each serving a specific function in the journey from a research hypothesis to empirical data and insight.

Layer 1: Perception & Actuation Layer

This is the physical interface of the SDL, where the digital world interacts with the material environment. It consists of sensors that collect raw data from experiments and actuators that perform physical tasks.

- Function: To observe the material world and execute physical actions based on decisions from higher layers.

- Key Components:

- Sensors: Advanced characterization tools such as Scanning Electron Microscopes (SEM) and Atom Probe Tomography (APT) that generate high-resolution, panoramic images and near-atomic-scale chemical composition data [20].

- Actuators: Robotic arms for sample handling, automated pipetting systems for solution-based synthesis, and stage controllers that position samples for characterization or processing.

- Data Output: Raw, unstructured data from sensors (e.g., micrograph images, spectral data) and status logs from actuators.

Layer 2: Network & Connectivity Layer

This layer is the central nervous system, responsible for the secure and reliable transmission of data and commands.

- Function: To facilitate bidirectional communication between the Perception Layer, data processing units, and control systems.

- Key Components & Protocols:

- Communication Protocols: Depending on latency, bandwidth, and distance requirements, a mix of protocols is used. For device-level communication, MQTT is ideal for its lightweight nature. For reliable message queuing in industrial settings, AMQP may be employed [21].

- Edge Gateways: Devices that perform initial data preprocessing and aggregation at the source, reducing latency and bandwidth usage by transmitting only critical information [21].

Layer 3: Data Processing & Middleware Layer

This is the computational brain of the SDL, where raw data is transformed into structured information. It employs advanced deep learning for automated analysis and simulation.

- Function: To store, process, and analyze spatiotemporal data, enabling automated feature extraction and initial insight generation.

- Key Technologies & Methodologies:

- Deep Learning Models: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are used for tasks like semantic segmentation, object detection, and classification of microstructures from SEM images [20]. Spatio-Temporal Deep Learning (SDL) models, such as ConvLSTM networks, can simulate physical phenomena like ultrasonic wave propagation faster than traditional finite element solvers [22].

- Data Storage: A centralized, highly reliable data store, akin to a Shared Data Layer, which consolidates subscription, session, and results data, making it accessible to all other layers and functions [23]. This aligns with the SDL's commitment to building comprehensive spatiotemporal data services [19].

Table 1: Deep Learning Applications in the Data Processing Layer for Materials Science

| Deep Learning Model | Application in Materials Research | Function | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Microstructural analysis of SEM images [20] | Semantic segmentation, damage site detection | Labeled images identifying phases and defects |

| 3D Convolutional Model | Analysis of 3D Atom Probe Tomography (APT) data [20] | 3D segmentation and classification | 3D maps of phase transformations at atomic scale |

| Spatio-Temporal Deep Learning (SDL/ConvLSTM) | Modelling wave propagation for non-destructive testing [22] | Predicting spatiotemporal sequence of wave dynamics | Simulated wave interaction with material defects |

Layer 4: Application & Workflow Layer

This layer translates processed data into executable scientific workflows and user-facing applications. It is where the "autonomous" logic is codified.

- Function: To host the tools that control the experimental workflow, enable data visualization, and facilitate human-SDL interaction.

- Key Components:

- Workflow-Driven Platforms: KNIME is a pivotal no-code/low-code platform used to construct reproducible, scalable, and workflow-driven methodologies [24] [19]. For example, a workflow can automatically take segmented SEM images from Layer 3, use them to generate a Finite Element (FE) mesh, and launch a simulation to evaluate elastoplastic behavior [20].

- Data Visualization Tools: Dashboards and interfaces for monitoring experiment progress and results.

Layer 5: Business & Intelligence Layer

This is the strategic apex of the SDL, responsible for project governance, resource allocation, and high-level decision-making to ensure research efficacy and return on investment.

- Function: To oversee the entire SDL operation, analyze outcomes, and make strategic decisions about future research directions.

- Key Processes:

- Governance: Enforcing data management policies and ensuring compliance with scientific and ethical standards [21].