Bridging the Gap: A Researcher's Guide to Handling Discrepancies Between Computational and Experimental Results

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to systematically identify, analyze, and resolve discrepancies between computational models and experimental data.

Bridging the Gap: A Researcher's Guide to Handling Discrepancies Between Computational and Experimental Results

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to systematically identify, analyze, and resolve discrepancies between computational models and experimental data. Covering foundational principles, methodological applications, troubleshooting strategies, and validation protocols, it synthesizes current best practices to enhance research integrity, improve model reliability, and accelerate the translation of in silico findings into robust biomedical applications. The guide emphasizes a collaborative, iterative approach to error management, crucial for ensuring the credibility and reproducibility of scientific discoveries.

Understanding the Divide: Why Computational and Experimental Results Diverge

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the first step I should take when I notice a significant discrepancy between my computational model and experimental results? Begin by systematically classifying the discrepancy. Determine if it is quantitative (a difference in magnitude) or qualitative (a difference in expected behavior or trend). This initial categorization will guide your subsequent investigation, helping you decide whether to focus on model parameters, algorithmic implementation, or the experimental setup itself.

Q2: How can I determine if a numerical error in my simulation is significant enough to invalidate my model's predictions? Perform a sensitivity analysis. Introduce small, controlled variations to your model's input parameters and initial conditions. If the resulting changes in output are of a similar or larger magnitude than the observed discrepancy, numerical errors and model instability are likely contributing factors. A robust model should be relatively insensitive to minor perturbations.

Q3: What are the common sources of error in the experimental data that can lead to apparent discrepancies? Common sources include:

- Calibration Errors: Instruments used for measurement may be improperly calibrated.

- Systematic Bias: The experimental design or procedure may consistently skew results in one direction.

- Sample Contamination: Impurities in reagents or samples can alter outcomes.

- Human Error: Mistakes in protocol execution or data recording can introduce noise and inaccuracies.

Q4: When should a discrepancy lead to model invalidation versus model refinement? A model should be considered for invalidation if discrepancies are fundamental and cannot be reconciled by adjusting parameters within physically or biologically plausible ranges. If the core principles of the model are contradicted, it may be invalid. However, if the discrepancy can be resolved by refining a sub-process or adding a new mechanism, then model refinement is the appropriate path.

Q5: What tools or methodologies can help automate the detection and analysis of discrepancies? Implementing automated validation frameworks is highly effective. These systems can continuously compare incoming experimental data against computational predictions using predefined statistical metrics (e.g., Chi-square tests, R-squared). Setting thresholds for automatic alerts can help researchers identify issues in near-real-time. Several software libraries for scientific computing offer built-in functions for such statistical comparisons.

Troubleshooting Guide: A Systematic Workflow

Follow this structured workflow to diagnose and address discrepancies between computational and experimental results.

Step 1: Classify the Discrepancy

First, characterize the nature of the mismatch.

- Quantitative Discrepancy: The model predicts values that are consistently higher or lower than experimental results, but the overall trends match.

- Qualitative Discrepancy: The model fails to capture a fundamental behavior observed in the experiment, such as a different response curve shape or the presence/absence of an expected peak.

Step 2: Verify the Experimental Data

Before altering your model, rule out errors in your experimental data.

- Action: Re-examine raw data and metadata. Check for instrument calibration logs, reagent batch numbers, and environmental conditions during the experiment. Repeat the experiment if possible.

- Outcome: Confirms the reliability of your benchmark data.

Step 3: Audit the Computational Model

Scrutinize the model's implementation and assumptions.

- Action:

- Code Review: Check for programming errors, incorrect unit conversions, or improper implementation of equations.

- Parameter Sensitivity: Analyze how sensitive the model is to its input parameters.

- Numerical Stability: Ensure that the solvers and algorithms used (e.g., for differential equations) are stable and appropriate for your problem.

- Outcome: Identifies coding bugs, inappropriate numerical methods, or overly sensitive parameters.

Step 4: Reconcile and Refine

Use the insights from the previous steps to resolve the discrepancy.

- Action: If the model structure is sound, refine its parameters by fitting them to the new, verified experimental data. If a fundamental process is missing, you may need to extend the model's structure.

- Outcome: A refined model with improved predictive power or a decision to invalidate the current model framework.

Step 5: Document and Report

Maintain a clear record of the entire process.

- Action: Document the initial discrepancy, all investigative steps taken, data from repeated experiments, code changes, and the final resolution.

- Outcome: Creates an audit trail that is crucial for research integrity, publication, and future model development.

Key Experimental Protocols for Discrepancy Investigation

Protocol 1: Sensitivity Analysis for Computational Models

This protocol tests how uncertainty in a model's output can be attributed to different sources of uncertainty in its inputs [1] [2].

- Select Parameters: Identify key input parameters for testing.

- Define Range: For each parameter, define a plausible range of values based on literature or experimental uncertainty.

- Perturb and Run: Systematically vary each parameter within its defined range while holding others constant. Run the simulation for each variation.

- Analyze Output: Record the change in the model's output. Calculate sensitivity measures, such as the normalized difference in output relative to the baseline.

- Interpret Results: Parameters that induce large output changes are high-sensitivity and prime candidates for causing discrepancies.

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation and Reproducibility Check

This protocol ensures the reliability of the experimental data used for model comparison.

- Intra-assay Validation: Repeat the experimental measurement multiple times within the same experiment to calculate the standard deviation and coefficient of variation.

- Inter-assay Validation: Perform the same experiment on different days, or with different batches of reagents, to assess reproducibility.

- Positive/Negative Controls: Include known controls to ensure the experimental system is functioning as expected.

- Blinded Analysis: Where possible, have a researcher blind to the expected outcomes perform the data analysis to prevent confirmation bias.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions in computational-experimental research, particularly in biomedical sciences.

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | Provides essential nutrients to maintain cells ex vivo for experiments. | Batch-to-batch variability can significantly affect experimental outcomes; always use a consistent source. |

| Specific Chemical Inhibitors/Agonists | Modulates the activity of specific signaling pathways or protein targets. | Verify selectivity for the intended target; off-target effects are a common source of discrepancy. |

| Validation Antibodies | Detects the presence, modification, or quantity of specific proteins (e.g., via Western Blot). | Antibody specificity must be rigorously validated; non-specific binding can lead to false positives. |

| Fluorescent Dyes/Reporters | Visualizes and quantifies biological processes in real-time (e.g., calcium flux, gene expression). | Photobleaching and signal-to-noise ratio must be optimized for accurate quantification. |

| Standardized Reference Compounds | Serves as a known benchmark for calibrating instruments and validating assays. | Using a traceable and pure standard is critical for inter-laboratory reproducibility. |

The following table outlines the minimum color contrast ratios required by WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) for text and graphical elements to ensure readability for users with low vision or color blindness [1] [3] [4]. Adhering to these standards is critical when creating diagrams, presentations, and dashboards for inclusive research collaboration.

| Content Type | WCAG Level AA | WCAG Level AAA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Text | 4.5:1 | 7:1 | Applies to most text content. |

| Large Text | 3:1 | 4.5:1 | Text that is 18pt+ or 14pt+ and bold [3]. |

| User Interface Components | 3:1 | - | For visual information used to indicate states (e.g., form input borders) [3]. |

| Incidental/Decorative Text | Exempt | Exempt | Text that is part of a logo or is purely decorative [1]. |

Example of a Contrast Check:

- Failed Example: Light gray (

#666) text on a white (#FFFFFF) background has a contrast ratio of 5.7:1, which fails the enhanced (AAA) requirement for normal text [1] [2]. - Passed Example: Dark gray (

#333) text on a white (#FFFFFF) background has a contrast ratio of 12.6:1, which passes all levels [1] [2]. - Color Values: White is defined in hexadecimal as

#FFFFFFwith RGB values of (255,255,255) [5] [6]. A light gray like#F1F3F4has RGB values of (241,243,244) [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Common Modeling Errors

This guide addresses frequent sources of discrepancy between computational models and experimental results, providing solutions to improve simulation accuracy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. My computational model fails to replicate physical test results. Where should I start investigating? Begin by systematically examining the three most common error sources: geometric inaccuracies in your model, improperly defined boundary conditions, and inaccurate material properties. A grid convergence study can help quantify discretization error, while sensitivity analysis can identify which parameters most significantly impact your results [8].

2. How can I determine if my geometric model is sufficiently accurate? Perform a sensitivity analysis on your geometry. If working with scanned data, account for potential distortions. One study on heart valve modeling found that a 30% geometric adjustment (elongation in the z-direction) was required to achieve realistic closure in fluid-structure interaction simulations, counterbalancing uncertainties from the imaging process [9].

3. Why do my stress results show significant errors even with a refined mesh? This often stems from incorrect boundary conditions or material definitions rather than discretization error. Ensure your supports and loads accurately reflect physical conditions. Critically, verify that your material model accounts for nonlinear behavior beyond the yield point; continuing with a linear assumption in this region produces "mathematically correct but completely wrong" results [10].

4. How can I manage uncertainties when experimental data is limited? In sparse data environments, combinatorial algorithms can help reduce epistemic uncertainty. These methods generate all possible geometric configurations (e.g., triangles from borehole data) to systematically analyze potential fault orientations or other geometric features, providing a statistical basis for interpretation [11].

5. What is the most common user error in Finite Element Analysis? Over-reliance on software output without understanding the underlying mechanics and numerics. Many users can operate the software but lack expertise to correctly interpret results, making them susceptible to accepting plausible-looking yet physically incorrect solutions [10].

Quantitative Error Classification

Table 1: Classification of Computational Modeling Errors and Mitigation Strategies

| Error Category | Specific Error Type | Potential Impact | Recommended Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry | "Bunching" effect from tissue preparation [9] | Prevents proper valve closure in FSI simulations | Use appropriate fixation techniques; computational adjustment via inverse FSI analysis [9] |

| Geometry | Geometric simplifications (small radii, holes) [10] | Missed local stress concentrations | Preserve critical geometric details; perform mesh sensitivity analysis [10] |

| Boundary Conditions | Unrealistic supports or loads [10] | Significant deviation from real-world behavior | Validate against simple physical tests; use measured operational data [10] |

| Material Properties | Linear assumption beyond yield point [10] | Non-conservative failure prediction | Implement appropriate nonlinear material models; verify against material tests [10] |

| Material Properties | Inaccurate material data (anisotropic, nonlinear) [10] | Erroneous stress-strain predictions | Conduct comprehensive material testing; use validated material libraries [10] |

| Numerical | Discretization error [8] | Inaccurate solution approximation | Perform grid convergence studies; refine mesh in critical regions [8] |

| Numerical | Iterative convergence error [8] | Prematurely terminated solution | Monitor multiple convergence metrics; use tighter convergence criteria [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Error Reduction

Protocol 1: Grid Convergence Study for Discretization Error Estimation

- Base Simulation: Begin with a computationally feasible mesh and obtain your solution.

- Systematic Refinement: Refine your mesh globally (or in regions of high gradient) by a factor (e.g., 2x elements) and recompute the solution.

- Key Variable Tracking: Monitor key output variables (e.g., max stress, displacement, temperature).

- Asymptotic Behavior: Continue refinement until these key variables show asymptotic behavior, indicating diminishing returns from further refinement.

- Error Estimation: Use the difference between successive solutions to estimate discretization error [8].

Protocol 2: Inverse FSI for Geometric Validation

- Image Acquisition: Obtain 3D geometry via μCT scanning or similar modality.

- Model Reconstruction: Develop a 3D computational model from image data.

- Initial FSI Simulation: Perform fluid-structure interaction analysis to assess closure.

- Closure Assessment: Determine if the model achieves physiologically realistic closure (e.g., for heart valves).

- Geometric Adjustment: If closure is inadequate, systematically adjust the geometry (e.g., elongation) and repeat FSI simulations until realistic behavior is achieved [9].

Workflow: Managing Geometric Uncertainty

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Computational and Experimental Materials for Model Validation

| Item | Function/Purpose | Field Application |

|---|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde Solution | Tissue fixation to counteract geometric "bunching" effect during imaging [9] | Biomedical FSI (e.g., heart valve modeling) |

| Combinatorial Algorithm | Generates all possible geometric configurations to reduce epistemic uncertainty in sparse data [11] | Subsurface geology; any data-sparse environment |

| MaxEnt/MaxPars Principles | Statistical reweighting strategies to refine conformational ensembles from simulation data [12] | Molecular dynamics; structural biology |

| GPU Parallel Processing | Enables high-resolution FSI simulations with practical runtime on standard workstations [9] | Complex FSI problems (e.g., SPH-FEM coupling) |

| Triangulated Surface Data | Connects points sampled from surfaces to analyze orientation data via triangle normal vectors [11] | Geological modeling; surface characterization |

FAQs: Addressing Common Experimental Uncertainties

FAQ 1: What are the primary sources of measurement noise in sensitive instrumentation like flow cytometry, and how can they be mitigated? Measurement noise originates from several sources, each requiring specific mitigation strategies. Thermal noise (Johnson noise), caused by random electron motion in conductors, is ubiquitous and temperature-dependent. Shot noise arises from the discrete quantum nature of light and electric charge. Optical noise, including stray light and sample autofluorescence, and reagent noise from non-specific antibody binding or dye aggregates also contribute significantly [13]. Mitigation involves a multi-pronged approach: using high-quality reagents with proper titration, employing optical filters and shielding to block stray light, cooling electronic components where practical, and optimizing instrument settings like detector voltage and laser power [14] [13].

FAQ 2: How can 'bunching' effects in biological samples impact the agreement between computational and experimental results? 'Bunching' effects describe physical distortions, such as the shrinking and thickening of delicate tissues when exposed to air. For example, in heart valve research, this effect causes leaflets to appear smaller and thicker in micro-CT scans, and chordae tendineae to appear bulky with minimal branching [9]. When this distorted geometry is used for computational fluid-structure interaction (FSI) simulations, the model may fail to replicate experimentally observed behavior, such as proper valve closure. This geometric error is a significant source of discrepancy, as the computational model's starting point does not accurately represent the original, functional physiology [9].

FAQ 3: What sample preparation protocols help minimize geometric uncertainties for ex-vivo tissue imaging? To counter 'bunching,' specialized preparation methods are critical. For heart valves, a key protocol involves fixing the tissue under physiological conditions. This is achieved by mounting the excised valve in a flow simulator that opens the leaflets and spreads the chordae, followed by perfusion with a glutaraldehyde solution to fix the tissue in this open state. This process counteracts the surface tension-induced distortions that occur when the tissue is exposed to air, helping to preserve a more life-like geometry for subsequent imaging and 3D model development [9].

FAQ 4: What strategies can be used computationally to counterbalance unresolved experimental uncertainties? When preparation methods are insufficient to fully eliminate geometric errors, computational counterbalancing can be employed. This involves an iterative in-silico validation process. If a geometry derived from medical images fails to achieve a known experimental outcome (e.g., valve closure), the model is systematically adjusted. For instance, elongating the model along its central axis and re-running FSI simulations can establish a relationship between the adjustment and the functional outcome. The model is iteratively refined until it reproduces the expected experimental behavior, thereby compensating for the unaccounted experimental uncertainties [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Measurement Noise in Flow Cytometry

The table below outlines common noise-related issues, their causes, and solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Flow Cytometry Noise

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Noise | High detector voltage, stray light, autofluorescence, non-specific reagent binding [13]. | Reduce detector voltage; use optical baffles; include blocking reagents; titrate antibodies; use viability dyes to exclude dead cells [14] [13]. |

| Weak Signal | Low laser power, misaligned optics, low detector voltage, or excessive noise masking the signal [13]. | Check and align optics; increase laser power; optimize detector voltage (balancing with noise); use bright fluorophores for low-abundance targets [14]. |

| High Fluorescence Intensity | Inappropriate instrument settings or over-staining [14]. | Decrease laser power or detector gain; titrate antibody reagents to optimal concentration [14]. |

| Unusual Scatter Properties | Poor sample quality, cellular debris, or contamination [14]. | Handle samples with care to avoid damage; use proper aseptic technique; avoid harsh vortexing [14]. |

| Erratic Signals | Electronic interference, air bubbles in fluidics, or fluctuating laser power [13]. | Use shielded cables and proper grounding; eliminate air bubbles from fluidics system; check laser stability [13]. |

Troubleshooting Discrepancies from Sample Preparation & Geometry

This guide addresses issues arising from sample handling and geometric inaccuracies.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Sample Preparation and Geometric Errors

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Leaflet 'Bunching' in Tissue | Surface tension from residual moisture upon exposure to air [9]. | Fix tissue under physiological flow conditions to preserve functional geometry; ensure tissue remains submerged in liquid to prevent dehydration [9]. |

| Computational Model Fails Experimental Validation | 3D model from medical images retains geometric errors (e.g., from 'bunching'); unknown uncertainties in the experimental-computational pipeline [9]. | Perform iterative in-silico testing; computationally adjust the model (e.g., elongation) until it validates against a known experimental outcome [9]. |

| Variability in Results Day-to-Day | Uncontrolled environmental factors; inconsistencies in reagent preparation or sample handling [15]. | Standardize protocols; use calibrated equipment; run appropriate controls with each experiment [15]. |

Workflow Diagrams

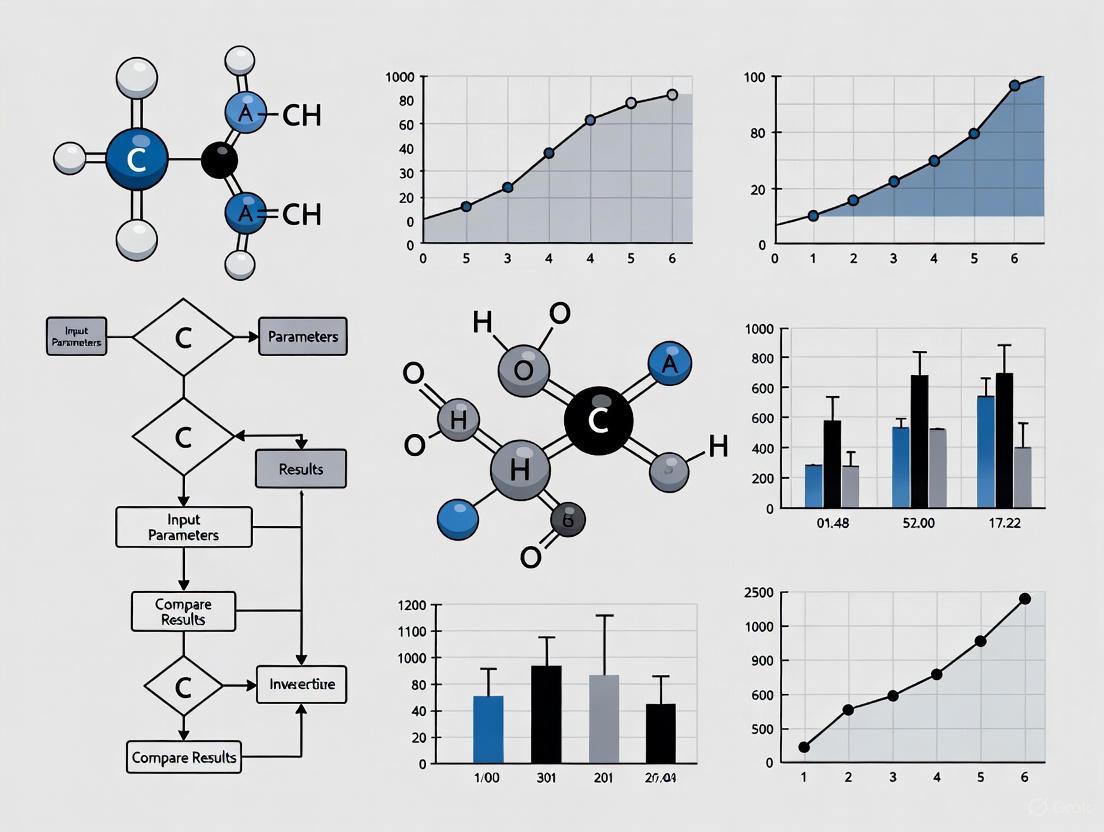

Diagram 1: Computational-Experimental Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: Noise Source Identification and Mitigation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Managing Experimental Uncertainties

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde Solution | A fixative used to cross-link and stabilize biological tissues, preserving their structure in a specific state (e.g., an open valve configuration) during imaging [9]. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent | Reduces non-specific binding of antibodies to immune cells, thereby lowering background noise (reagent noise) in flow cytometry [14] [13]. |

| Viability Dye | Distinguishes live cells from dead cells. Dead cells exhibit high autofluorescence and non-specific binding, so excluding them during analysis reduces background noise [14]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | A balanced salt solution used to maintain pH and osmolarity, providing a stable environment for cells and tissues during preparation and analysis [16]. |

| Optical Filters & Baffles | Hardware components that block stray light and unwanted wavelengths from reaching the detectors, minimizing optical noise [13]. |

| Fluorophore-Conjugated Antibodies | Antibodies labeled with fluorescent dyes for detecting specific cellular markers. High-quality, titrated, and properly conjugated antibodies are crucial for minimizing reagent noise [14] [17]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Discrepancies Between Computational and Experimental Results

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP) reports low average errors, but my molecular dynamics simulations show incorrect physical properties. What is wrong?

- Problem: The model fails to accurately simulate atomic dynamics and rare events, even when standard metrics like root-mean-square error (RMSE) for energies and forces appear excellent [18].

- Solution: Do not rely solely on average error metrics. Develop and use evaluation metrics specifically designed for the dynamic properties you want to predict, such as force errors on migrating atoms during rare events. Augment your training dataset with configurations that include these rare events to improve the model's predictive power for dynamics [18].

FAQ 2: I cannot install or run the computational tool from a published paper. What should I do?

- Problem: The software's URL is broken, the installation instructions are unclear, or dependencies are missing [19].

- Solution:

- Check if the journal or authors have provided a software capsule on a platform like Code Ocean or a container like Docker, which can simplify setup [20].

- Look for the software on alternative repositories like GitHub or GitLab.

- Use a tool like SciConv, which uses a conversational interface to automatically infer dependencies and build the computational environment from provided code [20].

FAQ 3: My computational predictions and experimental validation data disagree. How do I determine the source of the discrepancy?

- Problem: It is unclear whether the error originates from the computational model, the experimental data, or both.

- Solution: Implement a structured benchmarking and validation workflow.

- For the computational model: Ensure it has been rigorously benchmarked against standardized datasets with known ground truths. Use the guidelines in the table below on benchmarking [21].

- For the experiment: Document all protocols meticulously to ensure experimental reproducibility. Transparently report what was tried and did not work [22].

- Collaborate: Improve communication between computational and experimental team members to clarify expectations, methods, and potential misunderstandings [23].

FAQ 4: How can I improve the long-term reproducibility of my computational research?

- Problem: Shared code and data become unusable within a few years due to changing software environments and link rot [19].

- Solution: Adopt best practices for computational research:

- Use containers: Package your entire computational environment using tools like Docker to ensure consistency [20] [24].

- Follow FAIR principles: Make your data and code Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [24].

- Archive code and data: Use stable, long-term repositories with persistent digital object identifiers (DOIs), not just personal or lab websites [19].

Diagnostic Tables for Common Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Discrepancies in Computational Modeling

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incorrect dynamics in simulation (e.g., diffusion) despite low average force errors [18] | Model failure on rare events or transition states | Check model performance on a dedicated rare-event test set; quantify force errors on migrating atoms [18] | Augment training data with rare-event configurations; develop dynamics-specific evaluation metrics [18] |

| Inability to reproduce a published computational analysis | Missing dependencies, broken software links, or incomplete documentation [19] | Attempt to install and run the software in a clean environment; check if provided URLs are active | Use a reproducibility tool like SciConv [20]; contact the corresponding author for code and data |

| Computational predictions do not match experimental results ("ground truth") | Flaws in the computational model, experimental noise, or an invalid "ground truth" [21] | Benchmark the computational method on a simulated dataset with a known ground truth; validate experimental protocols | Use a systematic benchmarking framework to test computational methods under controlled conditions [21] |

| Successful local analysis fails in a collaborator's environment | Differences in software versions, operating systems, or package dependencies | Document all software versions (e.g., with a requirements.txt file or an environment configuration file) |

Use containerization (e.g., Docker) to create a portable and consistent computational environment [20] [24] |

Table 2: Quantitative Evaluation of Reproducibility in Scientific Software

This table summarizes an empirical evaluation of the archival stability and installability of bioinformatics software, highlighting the scale of the technical reproducibility problem [19].

| Evaluation Metric | Time Period | Result | Implication for Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|

| URL Accessibility | 2005-2017 | 28% of resources were not accessible via their published URLs [19] | Published URLs are unreliable; authors must use permanent archives. |

| Installability Success | 2019 | 51% of tools were "easy to install"; 28% failed to install [19] | Even with available code, installation is a major hurdle for reproducibility. |

| Effect of Easy Installation | 2019 | Tools with easy installation processes received significantly more citations [19] | Investing in reproducible software distribution increases research impact. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking a New Computational Method

Purpose: To rigorously compare the performance of a new computational method against existing state-of-the-art methods using well-characterized datasets [21].

Workflow Diagram: Benchmarking a Computational Method

- Define Purpose and Scope: Clearly state the goal of the benchmark. Is it a "neutral" comparison or for demonstrating a new method's advantages? This dictates the comprehensiveness [21].

- Select Methods: For a neutral benchmark, include all available methods that meet predefined criteria (e.g., working software, available documentation). Justify the exclusion of any major methods. When introducing a new method, compare it against a representative set of current best-performing and baseline methods [21].

- Select or Design Datasets: Use a variety of datasets to evaluate methods under different conditions.

- Define Performance Metrics: Choose metrics that accurately reflect the method's performance for the intended task (e.g., accuracy, speed, stability) [21].

- Execute Benchmark Runs: Run all methods on the selected datasets. To ensure fairness, avoid extensively tuning your new method while using defaults for others. Use consistent computational environments for all tests [21].

- Analyze and Interpret Results: Summarize results in the context of the benchmark's purpose. Use rankings and visualization to identify a set of high-performing methods and discuss their different strengths and trade-offs [21].

Protocol 2: Developing a Robust Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP)

Purpose: To create an MLIP that not only achieves low average errors but also accurately reproduces atomic dynamics and physical properties in molecular simulations [18].

Workflow Diagram: MLIP Development and Discrepancy Analysis

- Initial Training: Train the MLIP on a diverse set of atomic configurations (bulk, defected, liquid, etc.) using energies and forces from ab initio (DFT) calculations as the target [18].

- Conventional Testing: Evaluate the model using standard metrics like root-mean-square error (RMSE) or mean-absolute error (MAE) of energies and forces on a standard testing dataset. A low error is necessary but not sufficient [18].

- Dynamics and Rare-Event Testing: Construct a specialized testing set of atomic configurations involving rare events (RE), such as a migrating vacancy or interstitial, from ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations. Quantify the model's force errors specifically on these migrating atoms [18].

- Identify Discrepancies: Compare the atomic dynamics and physical properties (e.g., diffusion energy barriers) predicted by the MLIP in MD simulations against AIMD results. Discrepancies here indicate a model failure not captured by average errors [18].

- Model Improvement: Augment the original training dataset with configurations from the rare-event test set. Use the RE-based force error metrics, rather than just average errors, to guide model selection and optimization [18].

- Validation: Re-test the improved MLIP on the rare-event testing set and in full MD simulations to confirm improved accuracy in predicting dynamics and physical properties [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Reproducible Computational-Experimental Research

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Containerization Software (e.g., Docker) | Packages code, dependencies, and the operating system into a single, portable unit (container) that runs consistently on any machine, solving "it works on my machine" problems [20] [24]. |

| Version Control Systems (e.g., Git, GitHub) | Tracks changes to code and documents, enabling collaboration and allowing researchers to revert to previous working states. Essential for managing both computational and experimental protocols. |

| Persistent Data Repositories (e.g., Zenodo, Dataverse) | Provides a permanent, citable home for research data and code, combating "link rot" and ensuring long-term accessibility [19]. |

| Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs) | Digitally documents experimental procedures, observations, and data in a structured, searchable format, enhancing transparency and reproducibility for the wet-lab components. |

| Rare-Event (RE) Testing Datasets | Specialized collections of atomic configurations that test a model's ability to simulate infrequent but critical dynamic processes, moving beyond static error metrics [18]. |

| Benchmarking Datasets with Ground Truth | Curated datasets (simulated or experimental) with known outcomes, allowing for the quantitative evaluation and comparison of computational methods [21]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Numerical Errors and Artifacts

Q: Our simulation aborts due to volumetric locking or produces unrealistic, overly stiff behavior in cardiac tissue. What is the cause and how can we resolve it?

- Problem: Volumetric locking is a common numerical issue when modeling nearly incompressible materials, such as cardiac tissue, with standard linear finite elements, particularly tetrahedral (T4) elements. This occurs because the element cannot simultaneously satisfy incompressibility constraints and represent the required deformation modes, leading to an over-stiff solution and inaccurate stresses [25].

- Solution: Implement advanced numerical techniques designed for near-incompressibility:

- Smoothed Finite Element Methods (S-FEM): S-FEM, such as the node-based (NS-FEM) or selective NS-/FS-FEM methods, are less sensitive to mesh distortion and are volumetric locking-free. They achieve this by smoothing strains over specially designed smoothing domains, avoiding the need for isoparametric mapping that can fail with distorted elements [25].

- Isogeometric Analysis (IGA): IGA uses smooth spline functions (e.g., NURBS) for both geometry representation and solution approximation. This higher-order continuity can provide more accurate results for curved geometries like heart valves without requiring excessive mesh refinement, thus avoiding locking issues [26].

- Hexahedral Elements: Where possible, use hexahedral (brick) elements, which are less prone to locking than tetrahedral elements. However, their generation for complex cardiac geometries is often difficult and not automatic [25].

Q: The simulated transcatheter valve does not deploy correctly in the patient-specific aortic root, or the results are highly sensitive to the mesh. What steps should we take?

- Problem: Complex, patient-specific geometries often include features like calcifications, thin leaflets, and stent struts. Standard simulations may fail to capture the intense mechanical interactions during device deployment, leading to non-convergence or physically implausible results like extreme tissue damage or device perforation [27].

- Solution: Adopt a robust numerical framework and ensure mesh quality:

- Enhanced Numerical Framework: Utilize frameworks capable of simulating the full crimping and deployment process, explicitly including all device components (stent, fabric, leaflets) and patient-specific anatomy (native leaflets, calcifications). This often requires dynamic non-linear Finite Element Analysis (FEA) [27].

- Mesh Independence Study: A critical step in any CFD or FEA study. Refine the mesh globally or in regions of high stress (e.g., near calcifications, device edges) until the key output parameters (e.g., contact pressure, flow area, stress maxima) change by less than a predefined tolerance (e.g., 2-5%). The solution should not depend on the number of elements or their size [28].

- Balloon Pressure Optimization: Computational studies show that the applied balloon pressure during valve deployment is a critical parameter. Simulations at different pressures (e.g., 3–5 atm) can identify an optimal range that ensures sufficient flow area and anchorage while minimizing tissue damage and paravalvular leak risk [27].

Geometry and Model Creation

Q: How can we manage geometric distortions introduced during the model creation process from medical images?

- Problem: The process of converting medical images (CT, MRI) into a 3D computational model can introduce simplifications, spikes, or gaps. Furthermore, automatic meshing of these complex geometries often results in poorly shaped or distorted elements, which degrade solution accuracy and can cause solver failures [28] [25].

- Solution: Implement a rigorous geometry cleaning and meshing pipeline:

- Image Segmentation: Use commercial (Mimics, 3mensio) or open-source (SimVascular, VMTK) software to create an initial 3D blood volume or tissue geometry from DICOM images [28] [29].

- Geometry Repair and Smoothing: Utilize software packages like AngioLab, MeshLab, or CAD tools to repair protrusions, fill internal gaps, and smooth surfaces. This step is crucial for generating a "watertight" geometry suitable for high-quality meshing [28].

- High-Quality Meshing: For valves and stents, strive for structured or swept meshes with hexahedral elements where possible. For complex anatomies, use adaptive meshing techniques to refine critical regions. Consider S-FEM or IGA, which are more tolerant of automatically generated tetrahedral meshes and complex geometries [25] [26].

Q: Our simulated valve kinematics and hemodynamics do not match experimental observations from pulse duplicator systems. What should we validate?

- Problem: Discrepancies between simulation and experiment often arise from incomplete modeling of the physical system, including boundary conditions, material properties, and device-tissue interaction [30].

- Solution: Establish a comprehensive validation protocol against in vitro data:

- Benchmarking with a Pulse Duplicator: Test the physical valve prototype under standardized conditions (e.g., ISO 5840) in a pulse duplicator system to measure key performance indicators (see Table 1 for metrics) [30].

- Compare Quantitative Hemodynamics: Calibrate the computational model until it reproduces the experimental values for Transvalvular Pressure Gradient (TPG), Effective Orifice Area (EOA), and Regurgitation Fraction (RF) within an acceptable margin of error.

- Compare Qualitative Behavior: Ensure the simulation captures observed phenomena like pinwheeling (leaflet entanglement), coaptation area, and leaflet opening shape. Using a semi-closed valve design in simulation and experiment can reduce pinwheeling and improve agreement [30].

Table 1: Key Performance Indicators for Valve Model Validation

| Parameter | Description | Function | Target/Experimental Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transvalvular Pressure Gradient (TPG) | Pressure difference across the open valve | Measures stenosis (flow obstruction) | Lower values indicate better performance (e.g., < 10 mmHg) [30] |

| Effective Orifice Area (EOA) | Functional cross-sectional area of blood flow | Assesses hemodynamic efficiency | Larger values indicate better performance [30] |

| Regurgitation Fraction (RF) | Percentage of blood that leaks back through the closed valve | Quantifies valve closure competence | Lower values indicate better sealing (e.g., < 10%) [30] |

| Pinwheeling Index (PI) | Measure of leaflet tissue entanglement | Predicts long-term structural durability | Minimized in semi-closed designs [30] |

| Area Cover Index | Measures how well the device covers the implantation zone | Predicts risk of Paravalvular Leak (PVL) | Higher values indicate better seal (e.g., ~100%) [31] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the most common sources of discrepancy between computational models and experimental results in heart valve studies?

- A: The primary sources are:

- Inadequate Mesh Resolution: A model that is not mesh-independent will produce different results upon refinement. Always perform a mesh sensitivity study [28].

- Oversimplified Material Models: Using linear or non-physiological material laws for tissues and device components fails to capture non-linear, hyperelastic, and anisotropic behaviors.

- Incorrect Boundary Conditions: Applying unrealistic constraints or loads (e.g., fixed boundaries where movement occurs) dramatically alters the mechanical outcome.

- Neglecting Patient-Specific Anatomy: Using idealized geometries instead of patient-specific models with critical features like calcifications misses key interactions that drive complications like paravalvular leak [27] [31].

- Ignoring Fluid-Structure Interaction (FSI): For accurate hemodynamics, it is often necessary to couple the structural deformation of the valve with the surrounding blood flow [28].

Q: How can we efficiently predict clinical outcomes like paravalvular leak (PVL) without running a full, computationally expensive FSI simulation?

- A: Leverage specialized, kinematically-driven simulation tools that trade high-fidelity physics for speed and clinical workflow integration. For example:

- The Virtual TAVR (VTAVR) framework uses patient-specific CT data and a kinematic simulator to optimize device placement, sizing, and implantation depth. It rapidly tests deployment scenarios to predict the "Area Cover Index," which correlates with PVL risk, and has shown strong agreement with post-operative CT scans (median surface error ~0.63 mm) [31].

- These tools provide excellent initial planning and device selection, identifying high-risk anatomies. Full FEA/FSI can then be used for a deeper mechanical analysis of the optimally positioned device [29] [31].

Q: Our simulation of a device in the aortic root predicts high stress on the tissue. How do we know if this indicates a risk of rupture in a patient?

- A: Correlate simulation results with clinical validation studies. Research has begun to establish quantitative thresholds from patient-specific models:

- The PRECISE-TAVI study found that a simulated contact pressure index greater than 11.5 could predict the need for a permanent pacemaker after TAVR with high accuracy (AUC 0.83) [29].

- While specific thresholds for root rupture are still being defined, simulations can identify relative risk by comparing stress and contact pressure distributions across different device sizes and deployment positions. High stresses concentrated near calcified nodules are a particular warning sign [29] [27].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Coupled Experimental-Computational Valve Validation

Objective: To validate a computational model of a transcatheter heart valve against in vitro performance data.

Materials:

- Pulse duplicator system (e.g., ViVitro Labs)

- Physiological saline test fluid

- Fabricated valve prototypes (e.g., porcine pericardium leaflets on nitinol stent)

- High-speed camera for leaflet kinematics

- Pressure and flow sensors

Methodology:

- Prototype Fabrication: Manufacture valves with both traditional closed geometries and novel semi-closed geometries with varying Opening Degrees and Free-Edge Shapes [30].

- In Vitro Testing: Mount each prototype in the pulse duplicator. Under controlled physiological conditions (e.g., right heart pressure for pulmonary valves), measure:

- Transvalvular Pressure Gradient (TPG)

- Effective Orifice Area (EOA)

- Regurgitation Fraction (RF)

- Record high-speed video to quantify pinwheeling and coaptation.

- Computational Model Setup: Create a digital twin of the valve geometry and the test environment.

- Use FEA to simulate valve deployment and closure under the same pressure loads.

- Use CFD or FSI to simulate fluid dynamics and compute TPG, EOA, and RF.

- Validation and Calibration: Iteratively calibrate the computational model's material properties and boundary conditions until the simulated TPG, EOA, and RF fall within one standard deviation of the in vitro measurements. Use the calibrated model to explore parameter spaces beyond experimental limits.

Workflow Diagram: Patient-Specific Valve Simulation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for creating and validating a patient-specific computational model, from medical imaging to clinical prediction.

Diagram Title: Patient-Specific Valve Simulation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Computational and Experimental Heart Valve Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| SimVascular | Software (Open-Source) | Image-based modeling, blood flow simulation (CFD) | Creating patient-specific models from clinical CT scans for pre-surgical planning [28] |

| FEops HEARTguide | Software Platform | Pre-procedural planning simulation (FEA) | Simulating TAVI device deployment in a patient's aortic root to predict paravalvular leak and conduction disturbances [29] |

| ViVitro Pulse Duplicator | Hardware/Test System | In vitro hydrodynamic performance testing | Benchmarking the regurgitation fraction and pressure gradient of a new transcatheter valve design under physiological conditions [30] |

| Porcine Pericardium | Biological Material | Leaflet material for valve prototypes | Fabricating test valves for in vitro studies to assess durability and hemodynamics [30] |

| Smoothed FEM (S-FEM) | Numerical Method | Volumetric locking-free structural mechanics | Simulating large deformations of cardiac tissue with automatically generated tetrahedral meshes without locking artifacts [25] |

| Isogeometric Analysis (IGA) | Numerical Method | High-fidelity analysis using smooth spline geometries | Efficiently simulating ventricular mechanics with high accuracy using a template NURBS geometry derived from echocardiogram data [26] |

| CircAdapt | Software Model | Lumped-parameter model of cardiovascular system | Simulating beat-to-beat hemodynamic effects of arrhythmias like Premature Ventricular Complexes (PVCs) [32] |

Systematic Workflows for Integrating and Aligning Computational and Experimental Data

A robust data integrity strategy is fundamental for ensuring the accuracy, consistency, and reliability of research data throughout its entire lifecycle, from initial collection to final analysis and reporting. In the context of research investigating discrepancies between computational and experimental results, maintaining data integrity is not just a best practice but a critical necessity. Compromised data can lead to flawed conclusions, loss of trust in scientific findings, and in fields like drug development, can pose significant ethical and legal risks [33].

This technical support center provides actionable guides and FAQs to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals implement strong data integrity practices. The guidance is structured to help you prevent, identify, and resolve common data issues that can lead to conflicts between your experimental and computational outcomes.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Resolving Data Collection Errors

Problem: Inaccurate or inconsistent data at the point of collection creates a flawed foundation for all subsequent analysis and computational modeling.

Symptoms:

- Unexplained outliers in experimental measurements.

- Inconsistent results between technical replicates.

- Computational models that fail to validate against experimental controls.

Resolution Steps:

- Verify Instrument Calibration: Check and recalibrate all measurement equipment according to manufacturer specifications. Document the calibration date and standards used.

- Review Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs): Ensure all personnel are trained on and are adhering to documented SOPs for data collection. Ambiguous procedures are a common source of human error [33].

- Implement Real-time Data Validation: Where possible, use automated systems to check data at the point of entry. Configure these systems to flag values that fall outside pre-defined, plausible ranges [33].

- Cross-check Raw Data: Regularly compare electronically captured data against manual source records (e.g., lab notebooks) to catch transcription errors early.

Prevention Best Practices:

- Automate Data Capture: Use direct electronic data transfer from instruments to databases to minimize manual entry errors [33].

- Create a Data Dictionary Before Collection: Define all variables, their units, allowed values, and formats in a data dictionary prior to starting experiments. This ensures consistency from the outset [34].

Guide: Addressing Computational-Experimental Discrepancies

Problem: A computational model, based on experimentally derived geometry or data, fails to replicate the observed experimental behavior.

Symptoms:

- A fluid-structure interaction (FSI) simulation of a heart valve does not achieve proper closure, unlike the physical specimen [9].

- Computational predictions consistently deviate from experimental measurements in a dose-response study.

Resolution Steps:

- Interrogate the Input Geometry/Data: Scrutinize the 3D models or data inputs used for the simulation. In experimental work, specimens can undergo changes (e.g., a "bunching" effect in heart valve leaflets when exposed to air) that alter their geometry from the native state [9].

- Perform Sensitivity Analysis: Systematically vary key input parameters within their uncertainty range in your computational model to identify which factors have the largest impact on the discrepancy.

- Confirm Boundary Conditions and Material Properties: Ensure that the constraints and material models applied in the simulation accurately reflect the experimental setup. Incorrect boundary conditions are a frequent source of error.

- Iterative Model Adjustment: As a diagnostic method, adjust the input model to see if the computational results can converge with experimental observations. For example, one study elongated a heart valve geometry by 30% in the Z-direction to achieve closure in silico that matched experimental findings, highlighting the impact of geometric uncertainty [9].

Prevention Best Practices:

- Thoroughly Document Experimental Conditions: Record all metadata about the experimental setup, including environmental conditions (temperature, humidity) and sample preparation methods (e.g., fixation techniques) that could influence the results [9] [34].

- Preserve Raw Data: Always save the original, unprocessed data. This allows you to revisit and re-process data if the initial computational analysis reveals unexpected discrepancies [34].

Guide: Managing Data Discrepancies with a Discrepancy Database

Problem: How to systematically track, manage, and resolve the numerous data issues that inevitably arise during a large-scale research project, such as a clinical trial.

Symptoms:

- Invalid data points that fall outside defined ranges.

- Inconsistent data (e.g., diastolic blood pressure recorded as higher than systolic).

- Missing mandatory data points.

Resolution Steps:

- Define Discrepancy Types: Classify discrepancies to streamline handling [35]:

- Univariate: A single response violates its defined format, type, or range.

- Multivariate: A response violates a validation rule involving other data points (e.g., diastolic > systolic pressure).

- Indicator: A follow-up question is missing when it should be present, or vice versa.

- Manual: Issues identified by users, such as illegible source data.

- Query the Discrepancy Database: Use a centralized system (e.g., Oracle Clinical's Discrepancy Database) to query for all outstanding issues based on type, status, or site [35].

- Investigate the Root Cause: Trace the discrepancy back to its source. This may involve checking original Clinical Report Forms (CRFs) or instrument logs.

- Execute Corrective Actions: Correct the data in the system, mark the discrepancy as irresolvable (with justification), or generate a Data Clarification Form (DCF) to send to the original investigator for resolution [35].

- Re-validate Data: Run Batch Validation processes after corrections to ensure discrepancies are resolved and no new ones are introduced [35].

Prevention Best Practices:

- Implement Automated Batch Validation: Schedule regular checks where the system validates all new or changed data against defined rules and procedures, providing a report of new and obsolete discrepancies [35].

- Establish Clear Review Workflows: Define clear roles and responsibilities for who reviews, investigates, and resolves each type of discrepancy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most important thing I can do to improve data integrity at the start of a project? A: Develop a comprehensive data dictionary before data collection begins. This document defines every variable, its meaning, format, allowed values, and units. It serves as a single source of truth, ensuring all team members collect and interpret data consistently, which is a cornerstone of data quality management [36] [34].

Q2: Our computational models often use geometries from medical images. Why is there still a discrepancy with experimental behavior? A: Medical imaging and subsequent model preparation introduce numerous uncertainties. The imaging process itself has limitations in resolution, and excised biological specimens can change shape due to factors like surface tension or fixation (e.g., the "bunching" effect). Your computational model's boundary conditions might also not perfectly replicate the in-vivo or in-vitro experimental environment [9]. It is critical to account for these potential geometric errors in your analysis.

Q3: What are the key principles we should follow for handling research data? A: The Guidelines for Research Data Integrity (GRDI) propose six key principles [34]:

- Accuracy: Data must correctly represent what was observed.

- Completeness: All relevant information must be captured.

- Reproducibility: The data collection and processing steps must be repeatable.

- Understandability: The data should be comprehensible to others.

- Interpretability: The correct conclusions can be drawn from the data.

- Transferability: Data can be read correctly using different software systems.

Q4: How can we effectively track and resolve data issues in a large team? A: Implement a formal discrepancy management process supported by a dedicated database. This allows you to log, categorize, and assign issues; track their status (e.g., new, under review, resolved); and maintain an audit trail of all investigations and corrective actions [35]. This is a standard practice in clinical data management.

Q5: Why is it so critical to keep the raw data file? A: Raw data is the most unaltered form of your data and serves as the definitive record of your experiment. If errors are discovered in your processing pipeline, or if you need to re-analyze the data with a different method, the raw data is your only source of truth. Always preserve raw data in a read-only format and perform all processing on copies [34].

Data Presentation

Data Integrity Principles and Specifications

Table 1: Key Data Integrity Principles and Their Application. This table summarizes the core principles for maintaining data integrity throughout the research lifecycle.

| Principle | Description | Practical Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy [34] | Data correctly represents the observed phenomena. | Implementing automated data validation rules to flag out-of-range values during entry [33]. |

| Completeness [34] | The dataset contains all relevant information. | Collecting key confounders and metadata (e.g., time, instrument ID) in addition to primary variables. |

| Reproducibility [34] | Data collection and processing can be repeated. | Using version control for scripts and documenting all data processing steps in a workflow. |

| Understandability [34] | Data is comprehensible without specialized domain knowledge. | Creating a clear data dictionary that explains variable names, codes, and units [36] [34]. |

| Interpretability [34] | The correct conclusions can be drawn from the data. | Providing context and business rules in the data dictionary to prevent misinterpretation [36]. |

| Transferability [34] | Data can be read by different software without error. | Saving data in open, non-proprietary file formats (e.g., CSV, XML) [34]. |

Table 2: Common Data Discrepancy Types and Resolution Methods. This table categorizes common data issues and recommends methods for their resolution, based on clinical data management practices.

| Discrepancy Type | Description | Common Resolution Method |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate [35] | A single data point violates its defined format, type, or range (e.g., a letter entered in a numeric field). | Correct the data point to conform to the defined specifications after verifying the intended value. |

| Multivariate [35] | A data point violates a logical rule involving other data (e.g., discharge date is before admission date). | Investigate all related data points and correct the inconsistent values. May require source verification. |

| Indicator [35] | Follow-up questions are incorrectly presented based on a prior response (e.g., "smoking frequency" is missing when "Do you smoke?"=Yes). | Correct the branching logic in the data collection form or ensure the missing follow-up data is entered. |

| Manual [35] | A user identifies an issue, such as illegible source data or a suspected transcription error. | Investigate the source document or original data. If irresolvable, document the reason and mark as such. |

Experimental Workflow and Data Relationships

Diagram 1: Integrated Data Integrity and Discrepancy Resolution Workflow. This diagram outlines the key stages in a robust data management strategy, highlighting the cyclical process of validation, discrepancy logging, resolution, and iterative model adjustment.

Research Reagent and Tool Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Data Integrity. This table lists key tools and reagents that support data integrity in computational-experimental research.

| Item / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Supporting Data Integrity |

|---|---|---|

| Data Dictionary [36] [34] | Documentation Tool | Serves as a central repository of metadata, defining data elements, meanings, formats, and relationships to ensure consistent use and interpretation. |

| Discrepancy Database [35] | Data Management System | Provides a structured system to log, track, assign, and resolve data issues, ensuring they are not overlooked and are handled systematically. |

| Glutaraldehyde Fixative [9] | Laboratory Reagent | Used in sample preparation (e.g., for heart valves) to help preserve native tissue geometry and counteract distortion ("bunching" effect) for more accurate imaging. |

| Automated Validation Scripts [33] | Software Tool | Programs that automatically check incoming data against predefined rules (e.g., range checks, consistency checks), reducing human error in data screening. |

| Version Control System (e.g., Git) | Software Tool | Tracks changes to code and scripts, ensuring the computational analysis process is reproducible and all modifications are documented. |

| Open File Formats (e.g., CSV, XML) [34] | Data Standard | Ensures long-term accessibility and transferability of data by avoiding dependency on proprietary, potentially obsolete, software. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Workflow Inconsistencies During Model Creation

Problem: Team members performing the same modeling task (e.g., parameter optimization) in different ways, leading to irreproducible results and failed validation.

Solution: Follow a structured process to identify and align on a single, standardized workflow [37].

- Step 1: Map the Most Frequent Path Document the workflow steps as they are most frequently performed, not an idealized version. This establishes a shared operational baseline [37].

- Step 2: Explicitly Document Variants Catalog all existing variations in the process. For example, note if some researchers use different feature extraction tools or optimization algorithms [37].

- Step 3: Interview at the Role Level Conduct interviews with researchers in the same role to uncover subtle differences in methodology that department-level discussions might miss [37].

- Step 4: Eliminate "Phantom Steps" Identify and document steps that depend on a specific person ("Ask Maria for her custom script") or a local, unofficial tool. Decide to formally integrate, standardize, or eliminate these steps [37].

- Step 5: Establish Clear Ownership Assign a single owner for the workflow who is responsible for defining exceptions and approving changes [37].

Guide 2: Fixing Model Validation Errors

Problem: A model fails validation when its output does not match additional experimental data not used during the initial optimization phase.

Solution: Implement a rigorous, multi-stage validation and generalization protocol [38] [39].

- Step 1: Return to Feature Extraction Re-examine the electrophysiological features extracted from the experimental data. Ensure they are robust and accurately represent the biological behavior you are trying to capture [38] [39].

- Step 2: Re-run Optimization with Adjusted Parameters Use an evolutionary algorithm to optimize model parameters again, but with a focus on the features that failed validation. This may involve adjusting the weighting of certain features in the cost function [38] [39].

- Step 3: Test Generalizability on a Morphological Population Validate the optimized model against a population of similar neuronal morphologies to assess its robustness and ensure it is not over-fitted to a single cell reconstruction [38] [39]. A 5-fold improvement in generalizability has been demonstrated with this approach [38] [39].

- Step 4: Continuous Workflow Improvement Treat this process as a cycle. Use the insights from validation failures to refine the creation workflow, leading to more robust models in the future [40].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our team has developed multiple successful models, but the creation process is different each time. How can we establish a universal workflow?

A1: A universal workflow integrates specific, compatible tools into a standardized pipeline. The key is to support numerous input and output formats to ensure flexibility. For neuronal models, this involves using a structured process where each model is based on a 3D morphological reconstruction and a set of ionic mechanisms, with an evolutionary algorithm optimizing parameters to match experimental features [38] [39].

Q2: What are the most common causes of discrepancies between computational models and experimental results?

A2: The primary causes are often workflow inconsistencies and model over-fitting. When team members use different methods for the same task, it introduces variability that is hard to trace [37]. Furthermore, if a model is only optimized for a specific dataset and not validated against a broader range of stimuli or morphologies, it will fail to generalize [38] [39].

Q3: How can we ensure our computational workflow produces validated and generalizable models?

A3: By adhering to a workflow that includes distinct creation, validation, and generalization phases. The model must be validated against additional experimental stimuli after its initial creation. Its generalizability is then assessed by testing it on a population of similar morphologies, which is a key indicator of a robust model [38] [39].

Q4: What should we do if our model fails the validation step?

A4: Do not consider it a failure but a diagnostic step. Return to the optimization phase with the new validation data. Use an evolutionary algorithm to adjust parameters to better match the full range of experimental observations, then re-validate [38] [39].

Workflow Data and Protocols

This table outlines the core phases of a universal workflow for model creation, detailing the objective and primary outcome of each stage.

| Phase | Objective | Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Creation | Build a model using 3D morphology and ionic mechanisms. | A model that replicates specific experimental features. |

| 2. Optimization | Adjust parameters to match target experimental data. | A parameter set that minimizes the difference from experimental data. |

| 3. Validation | Test the optimized model against new, unused stimuli. | A quantitative measure of model performance beyond training data. |

| 4. Generalization | Assess model on a population of similar morphologies. | A robustness score (e.g., 5-fold improvement). |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential tools and their functions for building and simulating detailed neuronal models.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| 3D Morphological Reconstruction (SWC, Neurolucida formats) | Provides the physical structure and geometry of the neuron for the model [38]. |

| Electrophysiological Data (NWB, Igor, axon formats) | Serves as the experimental benchmark for feature extraction and validation [38]. |

| Evolutionary Algorithm | Optimizes model parameters to fit electrophysiological features [38] [39]. |

| Feature Extraction Tool (e.g., BluePyEfel) | Automates the calculation of key electrophysiological features from data [38]. |

| Simulator (e.g., Neuron, Arbor) | The computational engine that runs the mathematical model of the neuron [38]. |

Workflow Visualization

Model Creation & Validation Workflow

Inconsistent Workflow Identification

Leveraging FAIR Principles for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable Data

In research investigating discrepancies between computational and experimental results, robust data management is not an administrative task but a critical scientific competency. The FAIR Guiding Principles—making data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—provide a powerful framework to enhance the integrity, traceability, and ultimate utility of research data [41] [42]. Originally conceived to improve the infrastructure supporting the reuse of scholarly data, these principles emphasize machine-actionability, ensuring computational systems can autonomously and meaningfully process data with minimal human intervention [42]. This is particularly vital in fields like biomedical engineering and drug development, where the integration of complex, multi-modal datasets (e.g., from genomics, medical imaging, and clinical trials) is essential for discovery [43] [44].

Adopting FAIR practices directly addresses common pain points in computational-experimental research. For instance, a study on heart valve mechanics highlighted how uncertainties in experimental geometry acquisition (e.g., a "bunching" effect on valve leaflets during micro-CT scanning) can lead to significant errors in subsequent fluid-structure interaction simulations [45]. FAIR-aligned data management, with its rigorous provenance tracking and metadata requirements, creates a reliable chain of evidence from raw experimental data through to computational models, helping to identify, diagnose, and reconcile such discrepancies [43]. This guide provides actionable troubleshooting advice and FAQs to help researchers implement these principles effectively.

FAIR Principles Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses specific, common challenges researchers face when trying to align their data practices with the FAIR principles.

Findability

Findability is the foundational step: data cannot be reused if it cannot be found. This requires machine-readable metadata, persistent identifiers, and indexing in searchable resources [41].

- Problem: "My team cannot locate existing datasets, leading to repeated experiments and wasted resources."

- Solution: Implement a centralized data catalog. Assign every dataset a Globally Unique and Persistent Identifier (PID) such as a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) [43] [46]. Ensure all datasets are described with rich, machine-readable metadata and registered in a searchable institutional or domain-specific repository [41] [44].

- Problem: "We have data, but it's stored on personal laptops, lab servers, or cloud drives with inconsistent naming, making it unfindable by others."

Accessibility

Accessibility ensures that once a user finds the required data and metadata, they understand how to access them. This often involves authentication and authorization, but the metadata should remain accessible even if the data itself is restricted [41] [43].

- Problem: "A reviewer requests access to our underlying data, but it's trapped behind an institutional firewall with no clear access procedure."

- Problem: "We lost access to a critical legacy dataset after a postdoctoral researcher left the lab."

- Solution: Deposit data in a sustainable, trusted repository—not on personal or individual lab storage. These repositories are funded for long-term preservation and provide resilience against personnel changes [46]. Ensure data is accessible via a standardized communication protocol like an API [44].

Interoperability

Interoperable data can be integrated with other data and used with applications or workflows for analysis, storage, and processing. This requires the use of shared languages and standards [41].

- Problem: "We cannot integrate our new genomic data with existing clinical trial data because they use different formats and vocabularies."

- Problem: "Our in-house data analysis scripts break every time we receive data from a collaborator because their file structure is inconsistent."

- Solution: Agree upon and use common, machine-readable data models and file formats (e.g., Allotrope Simple Model for lab data) for data exchange. Implement an automated data validation step in your workflow to check for format compliance before processing [43].

Reusability

Reusability is the ultimate goal of FAIR, optimizing the reuse of data by ensuring it is well-described, has clear provenance, and is governed by a transparent license [41].

- Problem: "We found a promising dataset, but we can't tell if we're allowed to use it for our commercial drug development project."

- Problem: "We are unable to reproduce the computational results from our own experiment six months later because we didn't record all data processing steps."

- Solution: Document comprehensive provenance information: who generated the data, how, when, and with what parameters and software versions [43]. Use workflow management systems to automatically capture this history. Provide rich metadata that describes the experimental context and methodology at a level of detail that would allow a peer to replicate the study [41] [48].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Is FAIR data the same as open data? No. FAIR data does not have to be open. FAIR focuses on the usability of data by both humans and machines, even under access restrictions. For example, sensitive clinical trial data can be highly FAIR—with rich metadata, clear access protocols, and standard formats—while remaining securely stored and accessible only to authorized researchers [43] [44]. Open data is focused on making data freely available to all, which is a separate consideration.

Q2: How do I select an appropriate repository for my data to ensure it is FAIR? A good repository will help make your data more valuable for current and future research. Key criteria to look for include [46]:

- Provides Persistent Identifiers (e.g., DOIs).

- Has a sustainable funding model for long-term preservation.

- Offers clear data license information.

- Provides curation services and helps with metadata creation.

- Is aligned with your research domain (a domain repository is often best). Tools like the "Repository Finder" (powered by re3data.org) can help you identify a suitable FAIR-aligned repository for your discipline [46].

Q3: What is the minimum required to make my data FAIR compliant? FAIR compliance requires more than good file naming. At a minimum, you should [43] [44]:

- Assign a Persistent Identifier (PID) to your dataset.

- Describe it with rich metadata using community standards.

- Use standardized vocabularies/ontologies for key concepts.

- Document provenance (how the data was created).

- Define clear access rights and licensing.

Q4: How can FAIR principles help with regulatory compliance? While FAIR is not a regulatory framework, it strongly supports compliance with standards like GLP, GMP, and FDA data integrity guidelines. By ensuring data is traceable, well-documented, and auditable, FAIR practices naturally create an environment conducive to passing regulatory audits [43]. The emphasis on provenance and reproducibility directly addresses core tenets of regulatory science.

Q5: We have decades of legacy data. How can we possibly make it FAIR? Start with new data generated by ongoing and future projects, ensuring it is FAIR from the point of creation. For legacy data, prioritize based on high-value or frequently used datasets. Develop automated pipelines where possible to retroactively assign metadata and standardize formats. A phased, prioritized approach is more feasible than attempting to "FAIRify" everything at once [43] [44].

Implementing FAIR: Protocols and Visual Guides

Experimental Protocol: Mitigating Geometric Discrepancies in Heart Valve Imaging

This protocol, derived from published research, outlines a methodology to minimize discrepancies between experimental and computational geometries, a common issue in biomechanics [45].

1. Tissue Preparation and Fixation:

- Obtain fresh ovine mitral valve tissue.

- Mount the valve in a pulsatile cylindrical left heart simulator (CLHS).

- Perfuse the system with a glutaraldehyde solution under physiological flow conditions to fix the tissue in an open, loaded state. This counteracts the "bunching" effect of leaflets and chordae that occurs due to surface tension when exposed to air [45].

2. Micro-Computed Tomography (μCT) Imaging:

- Dismount the fixed CLHS chamber, drain and rinse it.

- Image the fixed valve assembly using μCT to obtain a high-resolution 3D dataset.

3. Image Processing and Mesh Generation:

- Process the μCT image stack using segmentation software to develop a preliminary 3D geometry of the heart valve.

- Generate a high-quality, robust computational mesh suitable for finite element analysis.

4. In Silico Validation via Fluid-Structure Interaction (FSI):

- Set up an FSI simulation using a method like Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) for the fluid domain and a finite element method for the solid valve structure [45].

- Simulate diastolic valve closure. A model with geometric errors from fixation or imaging will fail to close completely, showing a large Regurgitant Orifice Area (ROA).

5. Iterative Geometry Adjustment:

- If closure is not achieved, systematically adjust the 3D model (e.g., by elongating the valve apparatus in the z-direction) to compensate for suspected shrinkage or distortion.

- Re-run the FSI simulation iteratively until a healthy coaptation (closure) is observed, validated against the coaptation lines seen during the initial experimental setup [45].

This workflow demonstrates an iterative approach to resolving discrepancies between experimental imaging and computational models, core to the thesis context.

Data FAIRification Workflow

This diagram outlines a general process for making research data FAIR, from creation to deposition and reuse.

Research Reagent and Infrastructure Solutions

The following table details key materials and infrastructure components essential for implementing FAIR principles in a research environment focused on computational-experimental studies.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for FAIR-Compliant Research

| Item | Function in FAIR Context |

|---|---|