Bridging Accuracy and Efficiency: Integrating DFT and Machine Learning for Next-Generation Material Validation

This article explores the transformative integration of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Machine Learning (ML) for validating material properties, a critical step in accelerating materials discovery and drug development.

Bridging Accuracy and Efficiency: Integrating DFT and Machine Learning for Next-Generation Material Validation

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Machine Learning (ML) for validating material properties, a critical step in accelerating materials discovery and drug development. We first establish the foundational synergy between DFT's accuracy and ML's scalability. The piece then delves into cutting-edge methodological frameworks, from specialized force fields to modular learning, and provides crucial troubleshooting strategies for overcoming data scarcity and generalization challenges. Finally, we present a rigorous comparative analysis of ML model performance and validation protocols, offering researchers and scientists a comprehensive guide to confidently deploying these hybrid computational approaches for reliable material property prediction.

The Computational Synergy: How DFT and Machine Learning Are Revolutionizing Materials Science

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as a cornerstone of modern computational materials science, enabling the prediction of electronic structures and material properties from first principles. Despite its widespread adoption, DFT is fundamentally constrained by its high computational cost, which typically scales as the cube of the system size (~O(N³)). This cubic scaling limits routine calculations to systems comprising only a few hundred atoms, creating a significant bottleneck for researching experimentally relevant systems that often involve hundreds of thousands of atoms or more [1]. The core of this computational challenge lies in the solution of the Kohn-Sham equations, which requires iterative diagonalization of large Hamiltonian matrices—a process whose cost grows prohibitively with system size [2] [3].

Recent advancements in machine learning (ML) are now circumventing this long-standing limitation, enabling electronic structure predictions at unprecedented scales. By developing ML surrogates that emulate key aspects of DFT calculations, researchers have demonstrated up to three orders of magnitude speedup on systems where DFT is tractable and, more importantly, have enabled predictions on scales where DFT calculations are fundamentally infeasible [1]. This article examines the computational bottlenecks of traditional DFT and presents detailed protocols for implementing machine learning approaches that maintain quantum accuracy while achieving linear scaling.

Quantitative Analysis of DFT Bottlenecks and ML Solutions

Table 1: Computational Scaling and Performance Comparison of Traditional DFT vs. Machine Learning Approaches

| Method | Computational Scaling | Maximum Practical System Size | Speedup Factor | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional DFT | O(N³) | Few hundred atoms | Reference | Cubic scaling from matrix diagonalization [1] |

| Linear-Scaling DFT | O(N) to O(N²) | Thousands of atoms | 10-100x | Limited generality, implementation complexity [1] |

| MALA (ML-LDOS) | O(N) | 100,000+ atoms | Up to 1000x | Training data requirements, transferability [1] [4] |

| ML-DFT Framework | O(N) with small prefactor | 10,000+ atoms | Orders of magnitude | Chemical space coverage [3] |

| SPHNet | O(N) with reduced TP operations | Extended molecular systems | 7x faster than prior ML models | Basis set limitations [2] |

Table 2: Accuracy Benchmarks of ML-DFT Methods Across Material Systems

| Method | Material System | Property Predicted | Error Metric | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MALA | Beryllium with stacking faults | Formation energy | N⁻¹/³ scaling | Correct physical behavior [1] |

| ML-DFT Framework | Organic molecules (C, H, N, O) | Total energy | Chemical accuracy | ~1 kcal/mol [3] |

| ML-DFT Framework | Polymer chains & crystals | Atomic forces | MAE | Suitable for MD simulations [3] |

| Neural Network Correction | Al-Ni-Pd, Al-Ni-Ti alloys | Formation enthalpy | Improved agreement with experiment | Enhanced phase stability prediction [5] |

| DNN Model | Battery cathode materials | Average voltage | MAE | ~0.3-0.4 V vs DFT [6] |

Machine Learning Approaches to DFT Acceleration

Key Methodological Frameworks

3.1.1 Local Density of States Learning (MALA) The Materials Learning Algorithms (MALA) package addresses DFT scalability by training neural networks to predict the local density of states (LDOS) directly from atomic environments. This approach leverages the "nearsightedness" principle of electronic matter, which states that local electronic properties depend primarily on nearby atomic arrangements. MALA employs bispectrum coefficients as descriptors that encode the positions of atoms relative to every point in real space, enabling a feed-forward neural network to map these descriptors to the LDOS [1] [4]. Since this mapping is performed individually for each point in real space, the resulting workflow is highly parallelizable and scales linearly with system size.

3.1.2 Direct Hamiltonian Prediction (SPHNet) SPHNet represents an alternative approach that focuses on directly predicting the Hamiltonian matrix using SE(3)-equivariant graph neural networks. This method incorporates adaptive sparsity through two innovative gates: the Sparse Pair Gate filters out unimportant node pairs to reduce tensor product computations, while the Sparse TP Gate prunes less significant interactions across different orders in tensor products. A Three-phase Sparsity Scheduler ensures stable convergence, allowing SPHNet to achieve up to 70% sparsity while maintaining accuracy, resulting in a 7x speedup over previous models and reduced memory usage by up to 75% [2].

3.1.3 Charge Density Emulation A third paradigm involves end-to-end ML models that emulate the essence of DFT by mapping atomic structures directly to electronic charge densities, from which other properties are derived. These frameworks use atom-centered fingerprints to represent chemical environments and predict charge density descriptors, which then serve as inputs for predicting additional electronic and atomic properties. This strategy maintains consistency with the fundamental DFT principle that the electronic charge density determines all system properties [3].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: ML-DFT Workflow for Large-Scale Electronic Structure Prediction

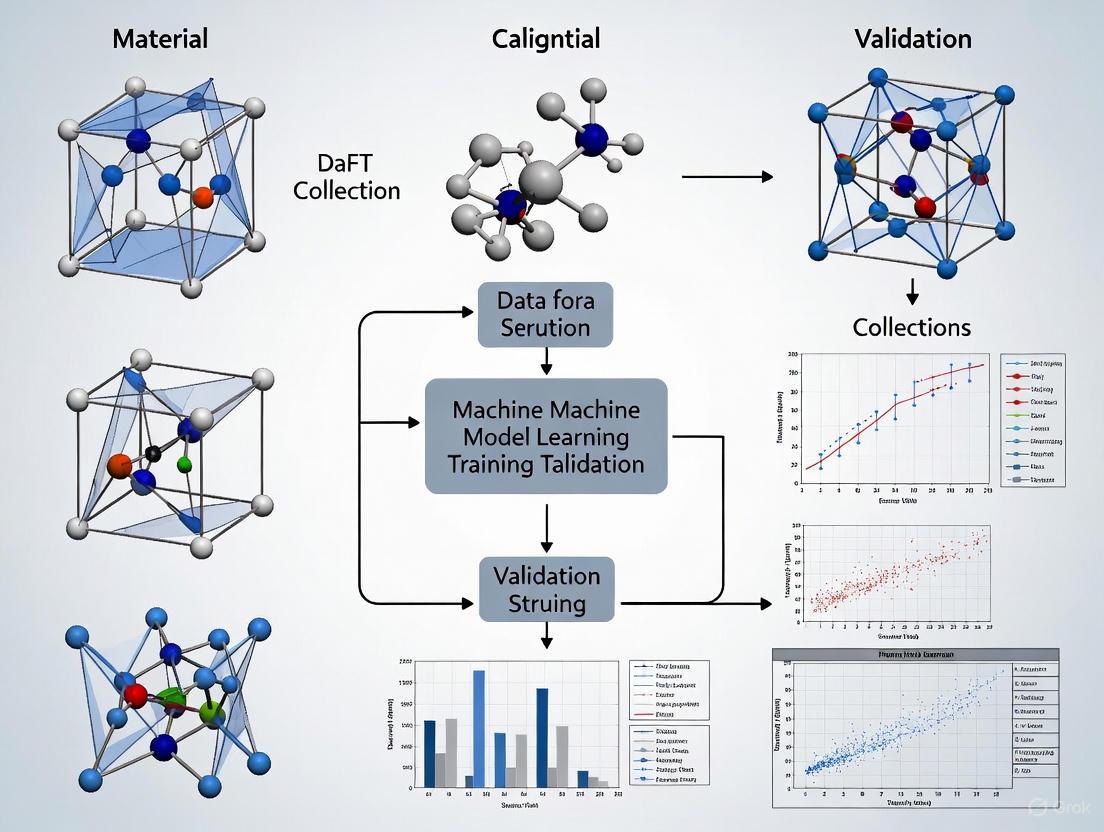

Figure 1: ML-DFT workflow for electronic structure calculation

Training Data Generation

- Perform DFT calculations on diverse small systems (typically 100-500 atoms) using standard packages (Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP).

- Calculate and store the local density of states (LDOS) or charge density on real-space grids.

- Extract atomic positions and convert to descriptors (bispectrum coefficients) using LAMMPS integration.

Model Training

- Implement feed-forward neural networks using PyTorch or TensorFlow.

- Train models to map bispectrum descriptors to LDOS values.

- Validate against held-out DFT calculations to ensure transferability.

Inference on Large Systems

- Deploy trained model to predict LDOS for large atomic configurations (>100,000 atoms).

- Post-process LDOS to compute electronic density, density of states, and total energy.

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations using predicted forces.

This protocol has demonstrated accurate energy calculations for beryllium systems with 131,072 atoms in just 48 minutes on 150 standard CPUs—orders of magnitude faster than conventional DFT [1] [4].

Protocol 2: Hamiltonian Prediction for Molecular Systems

Figure 2: SPHNet workflow for Hamiltonian prediction

Data Preparation

- Generate Hamiltonian matrices for diverse molecular configurations using DFT.

- Utilize datasets such as QH9 or PubchemQH containing quantum chemical properties.

Model Implementation

- Construct SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network with tensor product operations.

- Implement two sparse gates: Sparse Pair Gate for node pairs and Sparse TP Gate for tensor product interactions.

- Apply Three-phase Sparsity Scheduler (random → adaptive → fixed) to gradually increase sparsity to 70%.

Training and Validation

- Train model to predict Hamiltonian matrices from atomic structures.

- Evaluate on test molecules for accuracy in derived properties (energy, HOMO-LUMO gap).

- Benchmark computational performance against traditional DFT and other ML models.

This approach has demonstrated state-of-the-art accuracy on QH9 and PubchemQH datasets while providing up to 7x speedup over existing models [2].

Table 3: Key Software Packages and Datasets for ML-DFT Research

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| MALA | Software package | ML-driven electronic structure prediction | Large-scale materials simulation [1] [4] |

| SPHNet | Efficient neural network | Hamiltonian prediction with adaptive sparsity | Molecular systems with large basis sets [2] |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | DFT code | Generate training data & benchmarks | General electronic structure calculations [4] |

| LAMMPS | Molecular dynamics | Descriptor calculation & dynamics | Atomic-scale simulation [1] [4] |

| OMol25 | Dataset | 100M+ DFT molecular snapshots | Training generalizable ML potentials [7] [8] |

| Materials Project | Database | DFT-calculated material properties | Battery materials validation [6] |

Application Notes

Stacking Fault Energetics in Beryllium

The application of MALA to beryllium systems with stacking faults demonstrates the capability of ML-DFT to capture subtle energetic differences in extended defects. By introducing a stacking fault (shifting three atomic layers to change local crystal structure from hcp to fcc), researchers used ML predictions to compute the energetic differences between faulted and pristine systems. The results correctly followed the expected ~N⁻¹/³ scaling with system size, validating that ML-derived energies exhibit correct physical behavior even for systems of 131,072 atoms—far beyond conventional DFT capabilities [1].

Battery Voltage Prediction

Machine learning models trained on DFT data from the Materials Project have successfully predicted average voltages for alkali-metal-ion battery materials. Using deep neural networks with comprehensive feature sets (structural, physical, chemical, electronic, thermodynamic, and battery descriptors), researchers achieved close alignment with DFT calculations (MAE ~0.3-0.4 V). This approach enabled rapid screening of novel Na-ion battery compositions, with subsequent DFT validation confirming predicted voltages, demonstrating a viable hybrid ML-DFT workflow for accelerated materials discovery [6].

Alloy Phase Stability

For ternary alloy systems (Al-Ni-Pd and Al-Ni-Ti) relevant to high-temperature applications, neural network models have been employed to correct systematic errors in DFT-calculated formation enthalpies. By learning the discrepancy between DFT and experimental values using elemental concentrations, atomic numbers, and interaction terms as features, ML corrections significantly improved the accuracy of phase stability predictions, enabling more reliable determination of ternary phase diagrams [5].

The integration of machine learning with density functional theory represents a paradigm shift in computational materials research, effectively addressing the fundamental scalability limitations of traditional DFT. Through approaches ranging from local density of states prediction to direct Hamiltonian learning, ML-enabled methods now provide quantum-accurate electronic structure calculations for systems comprising hundreds of thousands of atoms with orders of magnitude speedup. The protocols and resources outlined in this article provide researchers with practical pathways to implement these advanced techniques, opening new frontiers for simulating complex materials at experimentally relevant scales. As benchmark datasets continue to expand and algorithms become more sophisticated, the integration of ML and DFT promises to unlock previously intractable problems in materials design and discovery.

The integration of Machine Learning (ML) with Density Functional Theory (DFT) represents a transformative advancement in computational materials research and drug development. This synergy addresses a critical bottleneck: the prohibitive computational cost of solving the Kohn-Sham equations, which has long constrained dynamical studies of complex phenomena at scale [3]. ML serves as a powerful force multiplier, augmenting the capabilities of researchers by providing orders-of-magnitude speedup while maintaining chemical accuracy, thereby freeing scientists to focus on higher-level analysis and strategic innovation [9] [10]. This paradigm shift is particularly impactful for applications requiring high-throughput screening, such as designing new catalysts, materials for energy storage, and pharmaceutical compounds, where traditional DFT approaches are computationally limited [3].

The core of this transformation lies in treating the Kohn-Sham equation as an input-output problem. Instead of performing explicit, costly DFT calculations, end-to-end ML models learn to map atomic structures directly to electronic properties and thermodynamic quantities [3]. This approach successfully bypasses the traditional computational hurdles, achieving linear scaling with system size with a small prefactor, making previously inaccessible studies of thousands of atoms over nanoseconds feasible [3]. For research professionals, this translates to accelerated discovery cycles and the ability to explore vast chemical spaces with unprecedented efficiency.

Core ML Methodologies and Quantitative Benchmarks

Architectural Frameworks for ML-DFT

Several sophisticated ML architectures have been developed to emulate and augment traditional DFT workflows, each with distinct advantages for specific research applications.

Deep Learning for Charge Density Prediction: A groundbreaking approach uses an end-to-end deep learning model that maps atomic structure directly to electronic charge density, which then serves as a descriptor for predicting other properties [3]. This method employs Atom-Centered AGNI Fingerprints to represent the structural and chemical environment of each atom in a translation, permutation, and rotation-invariant manner [3]. The model predicts the decomposition of atomic charge density in terms of Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs), with the model learning the optimal basis set from data rather than using predefined basis functions [3].

Electronic Charge Density as Universal Descriptor: A universal framework utilizes electronic charge density as the sole input descriptor for predicting multiple material properties [11]. This approach leverages the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem, which establishes a one-to-one correspondence between ground-state wavefunctions and real-space electronic charge density [11]. The methodology converts 3D charge density data into image representations and employs Multi-Scale Attention-Based 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (MSA-3DCNN) to extract features and establish mappings to target properties [11].

Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (CGCNN): For crystalline materials, CGCNNs create a crystal graph representation where atoms serve as nodes and chemical bonds as edges, enabling accurate prediction of formation energies, band gaps, and elastic moduli [12].

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of ML-DFT Models for Property Prediction

| Model Architecture | Target Properties | Accuracy Metrics | Computational Speedup | Applicable Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning Charge Density Framework [3] | Charge density, DOS, potential energy, atomic forces, stress tensor | Chemical accuracy maintained | Orders of magnitude (linear scaling) | Organic molecules, polymer chains, crystals (C, H, N, O) |

| Universal Density-based MSA-3DCNN [11] | 8 different ground-state properties | Avg. R²: 0.66 (single-task), 0.78 (multi-task) | Not specified | Diverse crystalline materials |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [12] | Formation energy, band gaps, elastic moduli | Better than DFT accuracy reported | Hundreds of times faster than DFT | Crystalline materials |

Addressing Dataset Redundancy with MD-HIT

A critical challenge in ML for materials science is dataset redundancy, where highly similar materials in training sets lead to overestimated model performance and poor generalization [12]. The MD-HIT algorithm addresses this by controlling redundancy in material datasets, similar to CD-HIT in bioinformatics [12]. When applied to composition- and structure-based prediction problems, models trained on MD-HIT-processed datasets show relatively lower performance on standard test sets but better reflect true prediction capability for novel materials [12]. This is particularly important for real-world applications where discovering new functional materials requires extrapolation rather than interpolation [12].

Table 2: ML Model Performance with and without Redundancy Control

| Evaluation Scenario | Reported Formation Energy MAE (eV/atom) | Generalization Capability | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random splitting (high redundancy) [12] | 0.064-0.07 | Overestimated, poor OOD performance | Preliminary screening |

| With redundancy control (MD-HIT) [12] | Relatively higher MAE | Better reflects true capability | Discovery of novel materials |

| K-fold Forward Cross-Validation [12] | Significantly higher MAE | Reveals weak extrapolation | Critical applications requiring robustness |

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol: ML-DFT for Organic Materials

This protocol outlines the procedure for implementing a deep learning framework to emulate DFT calculations for organic materials containing C, H, N, and O, based on established methodologies [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Software Requirements: Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP) for reference DFT calculations [3]

- Fingerprinting Tool: Atom-centered AGNI fingerprints for structure representation [3]

- ML Framework: Deep neural network implementation (Python with TensorFlow/PyTorch)

- Data Availability: Over 118,000 structures for training and testing [3]

Step-by-Step Procedure

Reference Data Generation:

- Perform DFT-based molecular dynamics (MD) runs at high temperatures (300K for molecules and polymer chains, 100-2500K for polymer crystals) to procure random snapshots with configurational diversity [3].

- Compute reference electronic properties (charge density, density of states, band properties) and atomic quantities (potential energy, atomic forces, stress tensor) using DFT [3].

Data Segmentation:

Atomic Fingerprinting:

Model Architecture Implementation:

- Implement a two-step learning procedure:

Reference System Transformation:

- Define an internal reference system using the two nearest neighbors of each atom [3].

- Calculate transformation matrices to convert from internal orthonormal reference systems to the global Cartesian system [3].

- Apply these transformations to rotation-variant properties like electron density and atomic forces [3].

Model Training and Validation:

- Train models using the preprocessed datasets.

- Validate prediction accuracy against DFT-calculated properties.

- Evaluate performance on independent test sets not used during training.

Protocol: Universal Property Prediction from Electronic Density

This protocol describes a methodology for predicting multiple material properties using electronic charge density as a universal descriptor [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Data Source: Materials Project CHGCAR files containing 3D charge density matrices [11]

- DL Architecture: Multi-Scale Attention-Based 3DCNN (MSA-3DCNN) [11]

- Preprocessing Tools: Data standardization and image representation pipelines [11]

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Curation:

- Acquire CHGCAR files from Materials Project containing 3D charge density matrices [11].

- Collect corresponding target properties for training.

Data Standardization:

Model Configuration:

Training Approach:

Performance Validation:

Workflow Visualization

ML-DFT Two-Step Prediction Workflow

Implementation Considerations for Research Applications

Data Quality and Model Generalization

The performance of ML-DFT models heavily depends on data quality and diversity. Researchers must address several critical considerations:

Redundancy Control: Implement MD-HIT or similar algorithms to eliminate highly similar structures from training sets, ensuring models generalize to novel materials rather than merely interpolating between similar examples [12]. This is particularly crucial for applications in drug development where novel molecular entities are the target.

Multi-Task Learning: Leverage multi-task learning frameworks where possible, as they demonstrate improved accuracy (average R² increasing from 0.66 to 0.78 in universal density models) compared to single-task approaches [11]. This enhancement stems from the physical correlations between different material properties that the model can exploit.

Transferability Challenges: Recognize that excellent performance on benchmark datasets with random splitting does not guarantee success for out-of-distribution samples [12]. Employ leave-one-cluster-out cross-validation or forward cross-validation for more realistic performance assessment [12].

Force Multiplication in Research Teams

The integration of ML-DFT approaches serves as a true force multiplier for research teams in several dimensions:

Accelerated Discovery Cycles: By reducing computation time from hours/days to seconds/minutes for property prediction, ML-DFT enables rapid screening of candidate materials or molecular compounds [3] [10]. This allows research teams to explore significantly larger chemical spaces with the same resources.

Augmented Expertise: ML tools handle repetitive prediction tasks, freeing researchers to focus on higher-value activities such as experimental design, result interpretation, and hypothesis generation [9] [10]. This effectively extends the capabilities of each team member without requiring expansion of team size.

Democratization of Computational Tools: The speed and accessibility of ML-based property prediction make advanced computational screening available to smaller research groups that may lack resources for extensive DFT calculations [9].

Machine learning has unequivocally established itself as a force multiplier in computational materials research and drug development, transforming the traditional DFT workflow from a computational bottleneck to an efficient discovery engine. The frameworks described herein—from charge density-based prediction to universal property models—demonstrate that ML can achieve chemical accuracy with orders-of-magnitude speedup [3] [11]. However, critical challenges remain in ensuring model generalizability beyond benchmark datasets, particularly for novel material classes with limited training data [12].

Future advancements will likely focus on improving extrapolation capabilities, developing better uncertainty quantification methods, and creating more sophisticated multi-task learning architectures that capture the fundamental physics underlying material properties [12] [11]. As these technologies mature, the integration of ML-DFT will become increasingly central to materials validation research, enabling accelerated discovery and development across pharmaceuticals, energy storage, catalysis, and beyond. For research professionals, embracing these tools represents not merely an adoption of new technology, but a strategic transformation of the research paradigm itself.

The integration of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Machine Learning (ML) is transforming the landscape of materials research by creating a powerful, iterative discovery loop. While DFT provides foundational quantum-mechanical calculations of material properties, it often faces challenges related to computational cost and accuracy for complex systems [5] [13]. Machine learning addresses these limitations by learning from existing DFT and experimental data to build predictive models, which in turn guide new DFT calculations and experimental validation [14] [15]. This synergistic integration significantly accelerates the discovery and optimization of electronic, mechanical, and catalytic materials, enabling researchers to navigate vast chemical spaces with unprecedented efficiency.

Application Notes and Protocols

The integration of DFT and ML has yielded significant advancements across various sub-disciplines of materials science. The table below summarizes key protocols, their technological impacts, and specific material systems targeted by these approaches.

Table 1: Key Application Areas of Integrated DFT and ML for Materials Discovery

| Application Area | DFT Contribution | ML Methodology | Key Outcome/Impact | Example Material Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Materials Band gap prediction [13] | High-fidelity band gap & lattice parameter calculations (DFT+U) as training data. | Supervised regression models (e.g., MLP) using Ud/f and Up as features. | Accurate, low-cost prediction of electronic properties; guides high-throughput screening. | Metal oxides (TiO₂, ZnO, CeO₂, ZrO₂) [13] |

| Mechanical/Structural Materials Phase stability [5] | Calculation of formation enthalpies (Hf) for alloys. | Neural network (MLP) to predict error between DFT and experimental enthalpies. | Improved reliability of phase diagram predictions for alloy design. | High-temp alloys (Al-Ni-Pd, Al-Ni-Ti) [5] |

| Catalytic Materials Acid-stability screening [16] | Evaluation of Pourbaix decomposition free energy (ΔGpbxOER) using HSE06. | SISSO-based symbolic regression to identify analytical descriptors. | Efficient identification of acid-stable oxides for electrocatalysis. | Water-splitting oxides [16] |

| High-Throughput Discovery General crystal stability [17] | Energetics of ~48,000 known crystals for model training and verification. | Scalable graph neural networks (GNoME) with active learning. | Order-of-magnitude expansion of known stable crystals. | Diverse inorganic crystals [17] |

Protocol for Electronic Materials: Band Gap Prediction in Metal Oxides

1. Objective: To accurately and efficiently predict the band gaps and lattice parameters of strongly correlated metal oxides by integrating DFT+U calculations with supervised machine learning [13].

2. Background: Standard DFT functionals (e.g., PBE) systematically underestimate the band gaps of metal oxides. The DFT+U method, which adds Hubbard corrections for on-site electron-electron interactions, improves accuracy but requires computationally expensive benchmarking to find optimal U parameters. A hybrid DFT+U+ML workflow overcomes this bottleneck [13].

3. Experimental Workflow:

- Step 1: High-Parameter DFT+U Calculations. Perform high-throughput DFT+U calculations for target metal oxides (e.g., rutile/anatase TiO₂, ZnO, CeO₂). The Hubbard U parameters are applied to both the metal d/f orbitals (U({d/f})) and the oxygen p orbitals (U(p)). A wide grid of integer (U(p), U({d/f})) pairs is explored to generate a comprehensive dataset of band gaps and lattice parameters [13].

- Step 2: Dataset Curation. The input features for the ML model are the U(p) and U({d/f}) values. The target outputs are the resulting band gaps and lattice parameters from the DFT+U calculations [13].

- Step 3: Model Training and Validation. Train relatively simple supervised ML regression models (e.g., Multi-layer Perceptrons/MLPs) on the generated dataset. The model learns to map the input (U(p), U({d/f})) values to the output structural and electronic properties. Model performance is evaluated using standard cross-validation techniques [13].

- Step 4: Prediction and Workflow Integration. The trained ML model can rapidly predict band gaps and lattice parameters for any given (U(p), U({d/f})) pair at a fraction of the computational cost of a full DFT+U calculation. This allows for rapid identification of optimal U parameters and pre-screening of materials before final, validation-level DFT calculations [13].

Protocol for Mechanical & Structural Materials: Alloy Phase Stability

1. Objective: To correct systematic errors in DFT-calculated formation enthalpies of alloys, thereby enabling reliable prediction of phase stability in binary and ternary systems [5].

2. Background: The predictive accuracy of DFT for alloy formation enthalpies is limited by intrinsic errors of exchange-correlation functionals. These errors are particularly detrimental for calculating ternary phase diagrams, where small energy differences determine stable phases. An ML-based correction model significantly improves agreement with experimental data [5].

3. Experimental Workflow:

- Step 1: Data Curation. Assemble a dataset containing both DFT-calculated and experimentally measured formation enthalpies (H(_f)) for a set of binary and ternary alloys. The dataset must be rigorously filtered to include only reliable experimental values [5].

- Step 2: Feature Engineering. Represent each material with a structured feature vector designed to capture chemical trends. This includes [5]:

- Elemental concentrations ((xA, xB, ...)).

- Weighted atomic numbers ((xA ZA, xB ZB, ...)).

- Interaction terms (e.g., (xA xB, xA xB x_C, ...)) to capture multi-element effects.

- Step 3: Error Learning and Model Training. Define the target variable as the discrepancy, ( \Delta Hf = Hf^{\text{exp}} - Hf^{\text{DFT}} ). Train a neural network model (e.g., a Multi-Layer Perceptron with three hidden layers) to learn the mapping from the feature vector to ( \Delta Hf ) [5].

- Step 4: Model Validation and Application. Validate the model using leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) and k-fold cross-validation to ensure robustness and prevent overfitting. For a new material, the predicted ( \Delta Hf ) is added to its DFT-calculated ( Hf ) to obtain a corrected, more accurate formation enthalpy for phase stability assessment [5].

Protocol for Catalytic Materials: Identifying Acid-Stable Electrocatalysts

1. Objective: To efficiently identify oxide materials that are thermodynamically stable under acidic oxygen evolution reaction (OER) conditions using an active learning workflow guided by symbolic regression [16].

2. Background: Discovering earth-abundant, acid-stable oxides for water splitting is crucial for sustainable hydrogen production. Directly evaluating stability via Pourbaix decomposition free energy ((\Delta G_{pbx}^{OER})) using high-quality DFT-HSE06 calculations is computationally prohibitive for large material spaces. The SISSO (Sure-Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) method identifies analytical descriptors from a large feature space, making it ideal for capturing complex materials properties [16].

3. Experimental Workflow:

- Step 1: Initial Sampling and Feature Compilation. Start with an initial training set of ~250 oxides with HSE06-calculated (\Delta G_{pbx}^{OER}) values. For all materials in the search space, compile a wide range of primary features (e.g., elemental properties, composition-averaged orbital radii, standard deviation of oxidation states) [16].

- Step 2: Ensemble SISSO Model Training. Train an ensemble of SISSO models to obtain both predictions and uncertainty estimates. This involves [16]:

- Bagging with Monte-Carlo Dropout: Create multiple bootstrapped training datasets. For each set, randomly drop a subset (e.g., 20%) of the primary features before training a SISSO model.

- The ensemble's mean prediction and standard deviation provide the property value and associated uncertainty.

- Step 3: Active Learning for Data Acquisition. Use the ensemble model to screen a large pool of candidate oxides. Select materials for the next HSE06 calculation based on a criterion that balances exploitation (predicted (\Delta G_{pbx}^{OER}) is low/stable) and exploration (high prediction uncertainty). This efficiently targets the most promising and informative regions of the materials space [16].

- Step 4: Iteration and Discovery. Iterate the process by adding the new HSE06 data to the training set and retraining the ensemble SISSO model. This workflow identified 12 acid-stable oxides from a pool of 1470 in only 30 active learning iterations [16].

Successful implementation of integrated DFT+ML workflows relies on a suite of computational tools and data resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for DFT and ML Materials Discovery

| Tool/Resource Category | Name/Example | Function/Purpose | Key Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Databases | Materials Project (MP) [17] [15], OQMD [17] [15], AFLOW [17], ICSD [17] [15] | Sources of crystal structures and pre-computed properties for training and benchmarking. | Provides initial data for model training; source of candidate structures. |

| DFT Calculation Software | VASP [17] [13], FHI-aims [16] | Performs first-principles quantum mechanical calculations to determine energy, structure, and properties. | Generates high-quality training data and validates final candidate materials. |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Graph Neural Networks [17], SISSO [16], Multi-layer Perceptrons [5] [13] | Learns complex patterns and structure-property relationships from data. | Core engine for predictive modeling and guiding active learning. |

| Validation & Benchmarking Tools | MatFold [18], k-fold & Leave-One-Out CV [5] | Provides standardized protocols to assess model generalizability and prevent over-optimistic performance estimates. | Critical for evaluating model robustness, especially for materials discovery tasks. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical flow of the key integrated DFT and ML protocols described in this document.

DFT+ML Workflow for Electronic Materials

ML Correction Protocol for Alloy Phase Stability

Active Learning Workflow for Stable Catalysts

The integration of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Machine Learning (ML) is revolutionizing materials science, enabling the rapid discovery and design of novel functional materials. This paradigm establishes a closed-loop workflow where computationally generated data trains ML models that predict material properties, design new candidates, and ultimately require experimental validation to confirm real-world utility. This framework is particularly vital in fields like battery research, catalyst design, and nanomaterial development, where traditional methods are often time-consuming and resource-intensive [14] [19] [20]. This document outlines the detailed protocols and application notes for implementing this workflow, providing researchers with a structured approach to accelerate materials validation research.

The Integrated DFT-ML Workflow: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

The general process for integrating DFT and machine learning in materials science involves several key stages, from initial data generation to the final experimental validation of predictions. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive workflow and the logical relationships between its components:

Stage 1: DFT-Generated Training Data

Objective: To generate a reliable and comprehensive dataset of material properties for subsequent machine learning tasks.

Protocol 1.1: Performing High-Throughput DFT Calculations

- System Selection: Define the chemical space of interest (e.g., ternary alloys, perovskite oxides). For example, in studying alloys for high-temperature applications, focus on systems like Al-Ni-Pd and Al-Ni-Ti [5].

- Computational Setup: Utilize standardized settings to ensure consistency.

- Software: Employ plane-wave codes (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) or the Exact Muffin-Tin Orbital (EMTO) method [5].

- Exchange-Correlation Functional: Select an appropriate functional (e.g., Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) GGA) [5].

- k-point Mesh: Use a dense mesh (e.g., (17 \times 17 \times 17) for cubic systems) for Brillouin zone integration [5].

- Convergence Parameters: Strictly enforce convergence criteria for energy, force, and stress to ensure result reliability.

- Property Calculation: Calculate target properties such as:

- Formation enthalpy ((H_f)) using Equation 1 [5].

- Electronic band structure and density of states.

- Elastic constants and bulk modulus.

- Data Curation: Store calculated properties in structured databases (e.g., Materials Project, OQMD, AFLOW, NOMAD) with consistent metadata [19].

Stage 2: Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

Objective: To transform raw DFT data into a clean, well-characterized dataset suitable for machine learning.

Protocol 2.1: Data Preprocessing and Redundancy Control

- Handling Missing Data: Identify and address missing values, either by imputation or removal, depending on the dataset size and context.

- Data Transformation and Standardization: Apply normalization or standardization to feature sets to ensure uniform scaling, which improves the stability and convergence of many ML models [21].

- Redundancy Control with MD-HIT: To avoid over-optimistic performance estimates and ensure model generalizability, apply redundancy control algorithms.

- Rationale: Materials databases contain many highly similar structures due to historical "tinkering" in material design. Random splitting of data can lead to data leakage [12].

- Method: Use the MD-HIT algorithm to cluster materials based on composition or structural similarity. Ensure that no two highly similar materials are in both the training and test sets [12].

- Outcome: This provides a more realistic evaluation of a model's extrapolation capability and its potential to discover truly novel materials [12].

Protocol 2.2: Feature Engineering and Selection

- Descriptor Generation:

- Compositional Descriptors: Use tools like Mendeleev, Matminer, or Magpie to generate features from elemental properties (e.g., atomic number, electronegativity, ionic radii) and their statistical summaries (mean, range, standard deviation) [21].

- Structural Descriptors: For inorganic crystals, use universal descriptors [21]. For organic molecules, employ molecular fingerprints or descriptors from RDKit or PaDEL [21].

- Domain Knowledge Descriptors: Incorporate known physical descriptors, such as the tolerance factor for perovskites [21] or features for high-entropy alloy phase parameters [21].

- Text-Based Descriptors: As an innovative approach, automatically generate human-readable text descriptions of crystal structures (e.g., using Robocrystallographer) and use language models to process them [22].

- Feature Selection:

- Objective: Reduce overfitting and model complexity by identifying the most relevant feature subset.

- Methods: Employ a combination of:

Stage 3: Machine Learning Model Development

Objective: To train, evaluate, and select ML models that accurately map material features to target properties.

Protocol 3.1: Model Training and Evaluation with Robust Validation

- Model Selection: Choose from a diverse set of algorithms, which may include:

- Random Forests: For robust, interpretable models with good performance on small datasets [22].

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): For structure-based property prediction, as they naturally handle crystal graphs [19] [22].

- Transformer Models: For text-based representations of materials, which can offer high accuracy and interpretability [22].

- Neural Networks: Multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) for learning complex, non-linear relationships in high-dimensional data [5].

- Robust Data Splitting: Avoid simple random splitting. Instead, use:

- Model Interpretation:

Table 1: Summary of Key ML Models and Their Applications in Materials Science

| Model Type | Best Suited For | Key Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest [22] | Small datasets, compositional trends | High interpretability, less prone to overfitting | Limited performance for complex structural dependencies |

| Graph Neural Networks [19] [22] | Structure-property relationships | State-of-the-art accuracy, natural for crystals | "Black-box" nature, requires large data, computationally intensive |

| Transformers (Text-Based) [22] | Small-data regimes, interpretability needs | High accuracy with text descriptions, explanations align with human rationale | Dependent on quality of text description |

| Multi-layer Perceptron [5] | Correcting DFT errors, non-linear mappings | Can learn complex patterns from diverse features | Can be prone to overfitting without careful regularization |

Stage 4: Prediction, Design, and Experimental Validation

Objective: To use trained ML models for the prediction of new materials and to validate these predictions experimentally.

Protocol 4.1: ML-Driven Material Design and Prediction

- Virtual Screening: Generate a large library of hypothetical material compositions and/or structures. Use the trained ML model to rapidly screen this library for candidates with desired properties [19].

- Inverse Design: Employ generative models like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) or Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) to directly generate novel material structures that satisfy target property constraints [19].

Protocol 4.2: Experimental Validation of Predictions

- Synthesis: Synthesize the top candidate materials predicted by the ML model using appropriate techniques (e.g., solid-state reaction, sol-gel, chemical vapor deposition).

- Characterization: Characterize the synthesized materials to confirm their structure, composition, and target properties using techniques such as:

- X-ray diffraction (XRD) for crystal structure.

- Electron microscopy (SEM/TEM) for morphology.

- X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) for elemental composition.

- Performance Testing: Test the material in its intended application (e.g., as a battery cathode, catalyst, or photovoltaic cell) to verify that its performance matches predictions [23] [20].

- Collaboration: For computational groups, collaboration with experimentalists is often essential for this step [23].

- Use of Reference Materials: For nanomaterial characterization, use nanoscale Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) or Reference Test Materials (RTMs) to validate measurement instruments and protocols, ensuring reliability and supporting regulatory approval [24].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DFT-ML Workflows

| Item Name | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Software | First-principles calculation of material properties. | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, EMTO-CPA [5] |

| Materials Databases | Source of training data (computational and experimental). | Materials Project [12], OQMD [12], JARVIS-DFT [22], PubChem [23] |

| Feature Extraction Tools | Generation of numerical descriptors from material composition/structure. | Matminer [21], RDKit [21], Mendeleev [21] |

| Text Description Generator | Creates human-readable crystal structure descriptions for ML. | Robocrystallographer [22] |

| Redundancy Control Tool | Clusters materials by similarity to prevent data leakage in model evaluation. | MD-HIT algorithm [12] |

| ML/AI Frameworks | Platform for building and training machine learning models. | TensorFlow, PyTorch, AutoGluon/TPOT for AutoML [19] |

| Nanoscale Reference Materials | Validation of characterization methods for nanomaterials. | NIST Gold Nanoparticles (e.g., NIST RM 8011, 8012, 8013) [24] |

Case Study: Correcting DFT Formation Enthalpies with Machine Learning

Background: A significant challenge in using DFT for predicting phase diagrams is the intrinsic error in formation enthalpy ((H_f)) calculations, which limits predictive accuracy for ternary systems [5].

Protocol: ML-based DFT Error Correction

- Data Collection:

- Compile a dataset of DFT-calculated formation enthalpies ((Hf^{DFT})) for a set of binary and ternary alloys (e.g., Al-Ni-Pd system).

- Assemble a corresponding set of experimentally measured formation enthalpies ((Hf^{Exp})) from reliable literature or databases. This serves as the ground truth [5].

- Target Variable Definition: The machine learning model is not trained to predict the formation enthalpy directly. Instead, it is trained to predict the error or discrepancy: (\Delta Hf = Hf^{Exp} - H_f^{DFT}) [5].

- Feature Engineering:

- Model Training and Implementation:

- Train a neural network (e.g., a Multi-layer Perceptron) as a regressor to learn the mapping:

Input Features ->(\Delta Hf) [5]. - Apply rigorous cross-validation (e.g., Leave-One-Out CV) to prevent overfitting [5].

- The corrected, more accurate formation enthalpy is then obtained as: (Hf^{Corrected} = Hf^{DFT} + \Delta Hf^{ML}).

- Train a neural network (e.g., a Multi-layer Perceptron) as a regressor to learn the mapping:

- Outcome: This approach significantly improves the accuracy of phase stability predictions, making DFT-based calculations more reliable for guiding the discovery of new alloys [5].

The workflow from DFT-generated data to ML-driven prediction and experimental validation represents a powerful, iterative engine for modern materials discovery. Success hinges on the meticulous execution of each stage: generating high-quality data, rigorously controlling for dataset redundancy, selecting appropriate models and features, and—most critically—closing the loop with experimental synthesis and validation. By adhering to the detailed protocols and utilizing the toolkit outlined in this document, researchers can robustly integrate computational and experimental efforts, thereby accelerating the development of next-generation functional materials.

Frameworks in Action: Implementing ML Force Fields and Predictive Models for Material Properties

In the study of two-dimensional twisted moiré materials, such as twisted bilayer graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), lattice relaxation profoundly influences electronic properties, including the emergence of strongly correlated states, unconventional superconductivity, and Mott insulating states [25]. However, accurately modeling these relaxation effects presents a significant computational challenge. Traditional density functional theory (DFT) calculations, while accurate, scale cubically with the number of atoms, making them prohibitively expensive for moiré superlattices containing thousands of atoms, especially at small twist angles where the supercell size becomes enormous [25]. While empirical force fields and parameterized continuum models offer alternatives, they often lack the accuracy or transferability required for predictive simulations [25].

Machine learning force fields (MLFFs) have emerged as a powerful solution to this computational bottleneck, capable of predicting energies and forces with near-DFT accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost. The DPmoire software package represents a specialized tool designed specifically for constructing accurate MLFFs in moiré systems [25] [26]. This application note details the implementation, validation, and application of DPmoire within a broader research framework integrating DFT and machine learning for material validation, providing researchers with comprehensive protocols for deploying this tool in the study of complex moiré materials.

Scientific Rationale: Why Specialized MLFFs for Moiré Systems?

Moiré structures exhibit unique characteristics that necessitate specialized approaches for force field development. In twisted bilayers, the varying local atomic registries create a complex potential energy landscape where different regions (AA, MX, XM in TMDs) correspond to distinct stacking configurations with different energy states [25]. The energy scales of electronic bands in these systems are often on the order of millielectronvolts (meV), comparable to the accuracy limits of universal MLFFs [25]. This precision requirement demands MLFFs specifically tailored to individual material systems rather than relying on general-purpose models.

The DPmoire methodology leverages the physical insight that at minimal twist angles, local atomic configurations in moiré structures closely resemble those in non-twisted systems with different stacking registries [25]. By comprehensively sampling the potential energy surfaces of these non-twisted configurations, DPmoire effectively reconstructs the potential energy landscape of twisted structures, enabling accurate and efficient relaxation of moiré superlattices.

Table: Comparison of Computational Methods for Moiré System Relaxation

| Method | Computational Scaling | Accuracy | Applicability to Small Twist Angles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard DFT | O(N³) | High | Limited |

| Continuum Models | O(1) | Moderate | Excellent |

| Empirical Force Fields | O(N) | Variable | Good |

| Universal MLFFs | O(N) | Moderate-High | Good |

| DPmoire (Specialized MLFF) | O(N) | High | Excellent |

DPmoire Architecture and Workflow

DPmoire is structured into four functional modules that streamline the process of generating, training, and validating MLFFs for moiré systems [26]:

DPmoire.preprocess: Automatically combines layer structures and generates shifted structures of a 2×2 supercell, prepares twisted structures for test sets, and manages VASP input files based on provided templates.DPmoire.dft: Submits VASP calculation jobs through the Slurm workload manager.DPmoire.data: Collects DFT-calculated data fromML_ABandOUTCARfiles, then generates training and test set files inextxyzformat compatible with Allegro and NequIP packages.DPmoire.train: Modifies system-dependent settings in configuration files and submits training jobs for Allegro or NequIP MLFFs.

The software utilizes advanced E(3)-equivariant graph neural network algorithms, specifically NequIP and Allegro, which ensure covariance among inputs, outputs, and hidden layers, leading to enhanced data efficiency and model accuracy [25]. For systems where robust empirical potentials are scarce, DPmoire provides a systematic approach to generating accurate MLFFs.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Moiré MLFF Development

Table: Essential Software Tools for DPmoire Implementation

| Tool Name | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DPmoire | Core package for generating and training MLFFs for moiré systems | Requires pre-installation of NequIP or Allegro for training [26] |

| VASP | Ab initio electronic structure calculations for dataset generation | Must be properly licensed and configured [26] |

| NequIP | E(3)-equivariant graph neural network for MLFF training | Provides high data efficiency [25] |

| Allegro | E(3)-equivariant MLFF algorithm optimized for large structures | Suitable for parallel computing [25] |

| Slurm | Workload manager for job submission and management | Essential for HPC environments [26] |

Application Notes: MX₂ Moiré Systems

DPmoire has been successfully applied to develop MLFFs for MX₂ materials (M = Mo, W; X = S, Se, Te), demonstrating robust performance in replicating electronic and structural properties obtained from DFT relaxations [25]. The MLFFs were rigorously validated against standard DFT results, confirming their efficacy in capturing complex atomic interactions within these layered materials [25].

For twisted TMD systems, the lattice relaxation significantly modulates the moiré potential, which in turn affects the electronic band structures. Experimental studies using scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) have documented relaxation patterns in TMDs resulting from lattice reconstruction [25], providing validation for computational approaches. DPmoire-generated MLFFs enable researchers to efficiently explore these relaxation effects across different twist angles without the computational burden of direct DFT calculations.

Table: Performance Metrics of DPmoire-Generated MLFFs for MX₂ Materials

| Material System | Energy RMSE (eV/atom) | Force RMSE (eV/Å) | Stress RMSE (kBar) | Twist Angle Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoS₂ | 1.21×10⁻⁴ | 8.13×10⁻³ | 6.08×10⁻¹ | 3.89° and smaller [25] |

| WS₂ | Data not specified in sources | Similar performance expected | Similar performance expected | 3.89° and smaller |

| MoSe₂ | Data not specified in sources | Similar performance expected | Similar performance expected | 3.89° and smaller |

| WSe₂ | Data not specified in sources | Similar performance expected | Similar performance expected | 3.89° and smaller |

Experimental Protocols

Dataset Generation Protocol

Initial Setup: Prepare

top_layer.poscarandbot_layer.poscarfiles ensuring the c-axis is sufficiently large. Create INCAR templates (init_INCAR,rlx_INCAR,MD_INCAR,MD_monolayer_INCAR,val_INCAR) with appropriate van der Waals correction settings [26].Configuration File Preparation: Set up

config.yamlwith key parameters including:n_sectors: Number of grid points for in-plane shifts (typically 9×9 structures before symmetry reduction)symm_reduce: True (to reduce computational cost by leveraging crystal symmetry)twist_val: True (to generate twisted structures for validation)min_val_nandmax_val_n: Define range of twist angles (n=1: 21.97°, n=2: 13.17°, n=3: 9.43°, etc.)d: Initial interlayer distance [26]

Structure Generation: Execute

DPmoire.preprocessto generate shifted and twisted structures. The module automatically creates a 2×2 supercell with various stacking configurations and prepares twisted structures for validation sets.DFT Calculations: Run

DPmoire.dftto submit VASP calculations through Slurm. EnableVASP_ML=Truein configuration to use VASP's on-the-fly MLFF for efficient data generation [26].

MLFF Training and Validation Protocol

Data Collection: Use

DPmoire.datato compile DFT data fromML_ABandOUTCARfiles intoextxyzformat for Allegro/NequIP training.Model Training: Execute

DPmoire.trainto train the MLFF using NequIP or Allegro. Critical training parameters include:validation_dataset_file_name: Location of validation datasetn_val: Number of validation structures- Training iterations until F_{rmse} reaches below 1×10⁻² eV/Å [26]

Error Analysis: Perform rigorous training-set and test-set error analysis following VASP MLFF protocols [27]. Compare:

- Training-set error: RMSE between DFT reference and MLFF prediction on training data

- Test-set error: RMSE on external test set not used during training

- Ideal scenario: Both errors are similarly low [27]

Hyperparameter Optimization: Adjust MLFF parameters based on error analysis:

- If overfitting occurs (low training error, high test error), increase training structures or tune hyperparameters

- For high training and test errors, expand dataset diversity or adjust model architecture [27]

Performance Optimization and Troubleshooting

Incongruent Data Issues: If training loss decreases slowly or F_{rmse} struggles to reach below 1×10⁻² eV/Å:

- Verify consistent INCAR template settings (e.g., avoid using different vdW corrections for relaxation and MD simulations)

- Check temperature stability during MD simulations as VASP MLFF can become unstable with strange structures [26]

Computational Efficiency:

Species Handling: For atoms in different environments (e.g., surface vs bulk), consider treating them as separate species in POSCAR to improve accuracy, despite increased computational cost [28].

DPmoire represents a specialized computational tool that effectively addresses the unique challenges of modeling moiré materials by combining the accuracy of DFT with the efficiency of machine learning force fields. Its structured workflow—from dataset generation through model training to validation—provides researchers with a robust framework for investigating relaxation effects in twisted two-dimensional materials. The integration of E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks ensures high data efficiency and accuracy, making it possible to explore complex moiré systems with minimal computational overhead. As research in quantum materials continues to emphasize the importance of moiré engineering, tools like DPmoire will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating the discovery and understanding of novel material properties in these systems.

The integration of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and machine learning (ML) has ushered in a new paradigm in computational materials science, extending predictive capabilities beyond traditional calculations of energies and forces. While DFT provides a quantum mechanical foundation for understanding materials at the atomic scale, its computational demands and systematic errors have limited its effectiveness for predicting critical functional properties like band gaps and elastic moduli. These properties are essential for designing materials for specific applications in electronics, energy storage, and drug development, where accurate prediction of electronic and mechanical behavior is crucial. The emergence of ML approaches has created opportunities to overcome these limitations, enabling high-accuracy prediction of complex properties while significantly reducing computational costs.

This integration represents a fundamental shift from purely physics-based modeling to hybrid approaches that leverage data-driven insights. Where DFT calculations provide the foundational data, ML models learn the complex relationships between material composition, structure, and properties, allowing for rapid screening and discovery of novel materials. This partnership has proven particularly valuable for properties that are computationally expensive to calculate directly or that suffer from systematic errors in DFT approximations. As research in this field accelerates, standardized protocols and application notes are needed to guide researchers in implementing these powerful methods effectively.

Quantitative Performance of DFT-ML Methods for Critical Property Prediction

Table 1: Performance Metrics of ML Models for Band Gap Prediction

| Material System | ML Method | Prediction Target | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spinel Oxides (AyB1-y[AxB2-x]O4) | Composition-based ML | Band Gap | Accurate predictions based solely on compositions | [29] |

| Organic Molecules | Random Forest | HOMO/LUMO Energies | MAE: 0.15 eV (HOMO), 0.16 eV (LUMO) | [30] |

| Diverse Crystals | Universal ML Framework (Electronic Density) | Multiple Properties | R² up to 0.94 for various properties | [11] |

| RbCdF3 under stress | DFT Analysis | Band Gap Changes | Increase from 3.128 eV to 3.533 eV under stress (12% rise) | [31] |

Table 2: Performance in Predicting Elastic Properties

| Material System | ML Method | Prediction Target | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystals | ElaTBot-DFT (LLM) | Elastic Constant Tensor | 33.1% error reduction vs. domain-specific LLM | [32] |

| 2D Elastic Metamaterials | XGBoost | Band Gap Position & Bandwidth | MAE: 339.06 (position), 116.45 (bandwidth) | [33] |

| Binary/Ternary Alloys | Neural Network (MLP) | Formation Enthalpy | Improved accuracy over standard DFT | [34] |

| Diverse Materials | Multi-Scale Attention-Based 3DCNN | 8 Different Properties | R²: 0.66 (single-task), 0.78 (multi-task) | [11] |

Methodological Protocols for Property Prediction

Protocol 1: Band Gap Prediction for Spinel Oxides Using Composition-Based ML

Objective: To predict electronic conductivity and band gaps of spinel oxides (AyB1−y[AxB2−x]O4) using machine learning based solely on material composition.

Materials and Computational Requirements:

- Dataset: 190 different ternary spinel oxides with varied stoichiometries

- DFT Methods: Geometry optimization and band structure calculations

- ML Algorithms: Models trained on compositional features

- Validation: Comparison with experimental trends for manganese cobalt spinels

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Database Construction: Perform DFT calculations on diverse spinel oxide compositions to generate a comprehensive dataset including band structure and conductivity properties [29].

Feature Engineering: Develop compositional descriptors based solely on element types and stoichiometries without structural information.

Model Training: Train machine learning algorithms to predict electronic conductivity and band gaps using the DFT-calculated database as training data.

Band Structure Fitting: Fit DFT-calculated band structures to tight-binding Hamiltonians for efficient electronic transport calculations.

Current Calculation: Compute current under 1V bias for each composition using Non-Equilibrium Green's Function (NEGF) and Landauer formalism.

Model Validation: Validate predictions against experimental trends, particularly for systems with high nickel content and manganese cobalt spinels.

Prediction: Deploy trained models to predict band gaps and conductivity for new spinel compositions not included in the original dataset.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Magnetic moment anomalies may require re-running DFT optimization with new initial magnetic moments

- For wide bands that are difficult to fit to tight-binding Hamiltonians, consider alternative fitting approaches

- Ensure dataset diversity to cover a representative portion of possible compositional combinations

Protocol 2: Elastic Constant Tensor Prediction Using Large Language Models

Objective: To predict full elastic constant tensors of materials using domain-specific Large Language Models (LLMs) fine-tuned on computational and experimental data.

Materials and Computational Requirements:

- Base LLM: Llama2-7b model

- Training Data: Elastic constant data from Materials Project and other sources

- Structural Descriptors: robocrystallographer for text-based structural descriptions

- Compositional Information: Pymatgen for extracting compositional features

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Curation: Collect and preprocess elastic constant tensor data from available databases, noting the scarcity of complete tensor data compared to other material properties [32].

Textual Representation: Convert crystal structures into text descriptions using robocrystallographer to create natural language representations suitable for LLM processing.

Feature Integration: Combine structural text descriptions with compositional information from Pymatgen to create comprehensive input prompts.

Model Fine-Tuning: Fine-tune the base Llama2-7b model on the formatted material property data to create the specialized ElaTBot-DFT model.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): Implement RAG capabilities to enhance predictions without retraining by leveraging external tools and databases.

Validation: Evaluate model performance using hold-out test sets and compare against traditional ML approaches and other domain-specific LLMs.

Prediction: Deploy the fine-tuned model for elastic constant tensor prediction, bulk modulus calculation, and generation of new materials with targeted elastic properties.

Key Advantages:

- Reduces prediction errors by 33.1% compared to domain-specific materials science LLMs

- Enables direct prediction of full elastic constant tensors, not just individual components

- Supports multi-task learning for simultaneous prediction of multiple properties

- Allows natural language interaction, lowering barriers for non-specialists

Protocol 3: Universal Material Property Prediction Using Electronic Charge Density

Objective: To predict eight different material properties using a unified machine learning framework based solely on electronic charge density as a universal descriptor.

Materials and Computational Requirements:

- Descriptor: Electronic charge density from DFT calculations

- Deep Learning Model: Multi-Scale Attention-Based 3D Convolutional Neural Network (MSA-3DCNN)

- Dataset: CHGCAR files from Materials Project database

- Computational Framework: Python with deep learning libraries (PyTorch/TensorFlow)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Curate electronic charge density data from the Materials Project database, representing results as three-dimensional matrices in CHGCAR files [11].

Data Standardization: Address dimensional variations in charge density data across different materials using interpolation schemes to create unified representations.

Image Representation: Convert 3D charge density matrices into 2D image snapshots along different crystal directions while preserving spatial relationships.

Model Architecture: Implement MSA-3DCNN with attention mechanisms to extract relevant features from charge density representations.

Training Strategy: Employ both single-task and multi-task learning approaches, comparing their relative performance for different properties.

Feature Extraction: Leverage the model's ability to capture subtle local variations in electron density, including accumulation near chemical bonds.

Validation: Evaluate transferability across different material classes and property types, assessing true extrapolation capability.

Key Insights:

- Electronic charge density serves as a physically grounded universal descriptor according to the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem

- Multi-task learning significantly enhances prediction accuracy compared to single-task approaches (R²: 0.78 vs 0.66)

- The method demonstrates excellent transferability across different property types

- Model captures complex structure-property relationships without explicit feature engineering

Workflow Visualization: Integrating DFT and ML for Property Prediction

DFT-ML Integration Workflow for Property Prediction

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for DFT-ML Integration

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP | DFT Software | Electronic structure calculations | Charge density calculation for ML descriptors [11] |

| Pymatgen | Python Library | Materials analysis | Compositional feature extraction [32] |

| robocrystallographer | Text Generation Tool | Structural description | Converting crystal structures to text for LLMs [32] |

| Materials Project | Database | Curated material properties | Source of training data for ML models [12] [11] |

| ElaTBot-DFT | Specialized LLM | Elastic property prediction | Predicting full elastic constant tensors [32] |

| MSA-3DCNN | Deep Learning Model | Charge density analysis | Universal property prediction [11] |

| XGBoost | ML Algorithm | Regression & Classification | Band gap prediction in metamaterials [33] |

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in the integration of DFT and ML for predicting critical material properties. Dataset redundancy represents a fundamental issue that can lead to overestimated model performance. Recent studies have shown that materials datasets often contain many highly similar materials due to historical tinkering approaches in material design [12]. This redundancy causes random splitting in ML model evaluation to fail, leading to over-optimistic performance metrics that don't reflect true predictive capability for novel materials. The MD-HIT algorithm has been developed to address this issue by reducing dataset redundancy, providing more realistic assessment of model performance.

The transferability of ML models across different material classes and properties remains another significant challenge. While traditional ML approaches have focused on predicting specific properties, recent advances in universal frameworks using electronic charge density show promise for multi-property prediction [11]. The electronic charge density serves as a physically grounded descriptor that contains comprehensive information about material behavior, enabling prediction of multiple properties within a unified framework.

Future developments will likely focus on improving model interpretability, addressing data scarcity for certain property types, and enhancing generalization to truly novel materials not represented in training data. The integration of large language models presents an exciting direction for materials science, offering natural language interfaces that lower barriers for non-specialists while providing powerful predictive capabilities [32]. As these methods mature, standardized protocols and benchmarking datasets will be essential for comparing different approaches and driving the field forward.

The synergy between DFT and machine learning continues to redefine the landscape of materials property prediction, moving beyond traditional limitations of energy and force calculations to enable accurate prediction of functionally critical properties like band gaps and elastic moduli. By combining physical principles with data-driven insights, this integrated approach promises to accelerate materials discovery and design across diverse applications from electronics to drug development.

The integration of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and machine learning (ML) has ushered in a transformative era for computational materials science, enabling the rapid prediction of material properties and the discovery of novel compounds. Traditional DFT calculations, while invaluable, are often hampered by high computational costs and systematic errors, particularly in complex systems with strong electron correlations [5] [13]. Machine learning, especially models utilizing Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), addresses these limitations by learning directly from the atomic structure of materials, offering a powerful, data-driven approach to complement first-principles calculations [35] [36]. The inherent graph-like nature of crystalline materials, where atoms naturally represent nodes and bonds represent edges, makes GNNs an exceptionally suitable architecture for modeling materials [35] [37].

Recent advancements have pushed beyond simple atom-bond representations by incorporating higher-order interactions. The inclusion of four-body interactions, such as dihedral angles, represents a significant leap in capturing the complex, multi-scale physics that govern material behavior [38]. These interactions are crucial for accurately describing the potential energy surface and for predicting sophisticated properties that depend on the precise spatial arrangement of atoms. Models like CrysGNN and CrysCo are at the forefront of this innovation, leveraging these advanced architectural principles to achieve state-of-the-art accuracy in property prediction [38]. This application note details the protocols for implementing these advanced GNN architectures, positioning them within a broader research framework for the validation of materials, particularly for applications in drug development and nanotechnology.

Table 1: Core Descriptors for Advanced GNN Models in Materials Science

| Descriptor Type | Specific Examples | Physical/Chemical Information Captured | Role in Model Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Features | Group number, period number, electronegativity, atomic radius [35] | Element-specific chemical identity and properties | Node feature initialization |

| Two-Body Interactions | Interatomic bond lengths, bond types [35] | Pairwise atomic interactions, bond strength | Basic edge construction in atom graph |

| Three-Body Interactions | Bond angles (θ) [35] | Local atomic geometry, orbital hybridization | Enhanced edge features, local curvature |

| Four-Body Interactions | Dihedral angles (φ), torsional potentials [38] | Out-of-plane torsion, complex conformational energies | Critical for capturing periodicity and long-range interactions |

Advanced GNN Architectures and Quantitative Performance

The evolution of GNNs for crystal materials has progressed from capturing basic connectivity to modeling intricate geometric relationships. Initial models like CGCNN (Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network) laid the groundwork by representing crystals as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [38]. Subsequent models like ALIGNN (Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network) improved accuracy by explicitly incorporating bond angles (three-body interactions) by constructing an additional graph from the bonds of the original atom graph [35] [38]. The latest generation of models, including CrysCo, now integrates four-body interactions, allowing them to capture an even more complete picture of the atomic environment, which is vital for predicting properties sensitive to complex structural deformations [38].

Quantitative benchmarking on large-scale public databases such as the Materials Project and JARVIS-DFT demonstrates the superior performance of these advanced architectures. For instance, the CGGAT (Crystal Gated Graph Attention Network) model, which combines a gated mechanism with an attention mechanism to weight the importance of different atomic neighbors, has been shown to outperform other GNN algorithms across a range of prediction tasks [35]. The following table summarizes the performance of several leading models, illustrating the gains achieved by incorporating more complex geometric information.

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance of Advanced GNN Models on Materials Project Data

| Model Architecture | Key Interactions Captured | Formation Energy (MAE in meV/atom) | Band Gap (MAE in eV) | Bulk Modulus (MAE in GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGCNN [38] | Two-body | ~28 | ~0.39 | ~0.078 |

| ALIGNN [38] | Two-body, Three-body | ~22 | ~0.32 | ~0.066 |

| MEGNet [38] | Two-body, Global state | ~21 | ~0.31 | ~0.068 |

| CGGAT [35] | Two-body, Three-body, Attention | ~19 | ~0.29 | ~0.063 |

| CrysCo [38] | Two-, Three-, and Four-body | ~17 | ~0.27 | ~0.059 |

The integration of DFT and ML is not limited to property prediction. Frameworks like GNoME (Graph Networks for Materials Exploration) from Google DeepMind use GNNs to discover new materials on an unprecedented scale, actively learning from DFT calculations to predict material stability and propose novel, synthesizable crystals [37]. This demonstrates a powerful闭环 (closed-loop) workflow where ML massively accelerates the discovery process, which is then validated by high-fidelity DFT.

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: DFT Data Generation for Training and Validation

Objective: To generate a high-quality, consistent dataset of crystal structures and their corresponding properties using DFT, which will serve as the ground truth for training and validating the GNN models.

- System Selection: Define the scope of the study (e.g., binary/ternary alloys, metal-organic frameworks, specific metal oxides). For example, studies may focus on systems like Al-Ni-Pd or Al-Ni-Ti for high-temperature applications, or metal oxides like TiO2 and ZnO for electronic properties [5] [13].

- Structure Acquisition & Preparation: Obtain crystal structures from databases like the Materials Project [35], OQMD [36], or COD. Standardize structures by refining atomic coordinates and lattice parameters.

- DFT Calculation Setup:

- Software: Employ plane-wave codes such as VASP [13] or EMTO [5].

- Exchange-Correlation Functional: Select an appropriate functional (e.g., PBE-GGA [5] [13]). For strongly correlated systems (e.g., metal oxides), apply the DFT+U method with Hubbard parameters (Ud/f, Up) to correct for self-interaction error [13].

- Computational Parameters: Ensure convergence of key parameters:

- Plane-wave kinetic energy cutoff: ≥ 520 eV.

- k-point mesh: Use a Γ-centered grid with a density of at least 1000/Å⁻³ per atom [5].

- Energy and force convergence criteria: Set to 10⁻⁶ eV and 0.01 eV/Å, respectively.

- Property Calculation: Calculate target properties for each structure. Key properties include:

- Formation Energy: Using Equation (1) from the background, comparing the total energy of the compound to its constituent elements in their standard states [5].

- Electronic Band Gap.

- Elastic Constants (for bulk and shear moduli).

- Data Curation: Filter the results to exclude calculations with poor convergence or missing data. Compile a final dataset of

(crystal structure, target property)pairs.

Protocol 2: Implementing a GNN with Four-Body Interactions

Objective: To construct, train, and evaluate a GNN model capable of learning from the atomic structure and multi-body interactions to predict material properties.

- Graph Representation Construction:

- Atom Graph: Represent the crystal structure as a graph

G = (V, E), where nodesv_i ∈ Vrepresent atoms, and edgese_ij ∈ Erepresent bonds between atoms within a specified cutoff radius (e.g., 5-8 Å). Node features include atomic number, group, period, etc. Edge features include bond length and bond type [35]. - Edge Graph (for higher-order interactions): To model three- and four-body interactions, create a line graph

L(G)where nodes correspond to the edges inG(i.e., bonds), and edges inL(G)connect two bonds that share an atom (for angles) or form a dihedral (for four-body terms). The features of nodes inL(G)can be the original bond features, while edges inL(G)can be parameterized by the bond angle or dihedral angle [35] [38].