Benchmarking DFT for Material Properties: A Practical Guide from Fundamentals to AI-Enhanced Predictions

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a cornerstone of computational materials science and drug development, but its predictive power is inherently tied to the choice of exchange-correlation functionals and validation against...

Benchmarking DFT for Material Properties: A Practical Guide from Fundamentals to AI-Enhanced Predictions

Abstract

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a cornerstone of computational materials science and drug development, but its predictive power is inherently tied to the choice of exchange-correlation functionals and validation against experimental data. This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking DFT predictions, moving from foundational principles and methodological selection to advanced troubleshooting and validation strategies. We explore common failure modes, such as for charge-transfer and strongly correlated systems, and detail how the integration of machine learning and multi-scale computational paradigms is revolutionizing accuracy. Tailored for researchers and pharmaceutical professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices to enhance the reliability of in silico material property prediction, ultimately aiming to accelerate the design of novel materials and therapeutics.

The Foundation of DFT: Understanding Its Strengths and Inherent Limitations

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as a cornerstone of modern computational materials science and drug development, providing a powerful framework for predicting the electronic structure of atoms, molecules, and solids. Unlike traditional quantum chemical methods that deal with complex many-electron wavefunctions, DFT simplifies the problem by using the electron density as its fundamental variable. This paradigm shift, formally established by the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, makes accurate calculations on complex systems computationally feasible. For researchers engaged in benchmarking DFT predictions for material properties and drug development, a deep understanding of these core principles is essential for selecting appropriate functionals, interpreting results, and assessing the reliability of computational data against experimental measurements. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems and the Kohn-Sham equations, framing them within the practical context of benchmarking studies critical for pharmaceutical and materials research.

The Theoretical Foundation: Hohenberg-Kohn Theorems

The First Hohenberg-Kohn Theorem

The first theorem establishes the foundational principle that makes DFT possible: the external potential ( V(\mathbf{r}) ) is uniquely determined by the ground state electron density ( n_0(\mathbf{r}) ) [1] [2]. This leads to the remarkable conclusion that all properties of a many-electron system in its ground state are uniquely determined by its ground state electron density.

For a system with N electrons moving under an external potential ( V(\mathbf{r}) ) (typically the nuclear potential), the Hamiltonian is expressed as: [ \hat{H}V = - \frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \sum{i=1}^N \nablai^2 + \sum{i=1}^N V(\mathbf{r}i) + \sum{i=1}^N \sum{j=i+1}^N U(\mathbf{r}i, \mathbf{r}j) ] where ( U(\mathbf{r}i, \mathbf{r}_j) ) represents the electron-electron interaction potential [2].

The ground state electron density ( n0(\mathbf{r}) ) is obtained from the ground state wavefunction ( \psi0 ) through: [ n0(\mathbf{r}) = \int d^3 \mathbf{r}1 \dots d^3 \mathbf{r}N \ \left( \sum{i=1}^N \delta^3 (\mathbf{r}i - \mathbf{r}) \right) \left| \psi0(\mathbf{r}1, \dots, \mathbf{r}N) \right|^2 ] This theorem proves that there exists a bijective mapping between the external potential ( V(\mathbf{r}) ) and the ground state density ( n_0(\mathbf{r}) ) [2]. Consequently, the ground state density completely determines all system properties, including the total energy.

The Second Hohenberg-Kohn Theorem

The second theorem provides the variational principle essential for practical calculations. It states that for a given external potential ( V(\mathbf{r}) ), the total energy functional ( EV[n] ) is minimized by the ground state electron density ( n0(\mathbf{r}) ) [1].

The universal energy functional ( F[n] ) can be defined for any electron density ( n(\mathbf{r}) ) (associated with some external potential) as: [ F[n] = \min{\psi \to n} \langle \psi | \hat{T} + \hat{U}{ee} | \psi \rangle ] where the minimization is over all wavefunctions ψ that yield the given density n [1] [2].

For any trial density ( n'(\mathbf{r}) ) that is v-representable (associated with some external potential), the total energy functional is: [ EV[n'] = F[n'] + \int V(\mathbf{r}) n'(\mathbf{r}) d\mathbf{r} ] The second theorem guarantees that: [ EV[n'] \geq EV[n0] ] where ( n_0 ) is the true ground state density for the system with external potential ( V(\mathbf{r}) ) [1]. This variational principle enables the practical determination of ground state properties by minimizing the energy functional with respect to the electron density.

Table 1: Core Components of the Hohenberg-Kohn Formulation

| Concept | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| External Potential | ( V(\mathbf{r}) ) | Potential from nuclear framework; unique for each system |

| Universal Functional | ( F[n] = T[n] + U_{ee}[n] ) | Contains kinetic and electron-electron interaction energies |

| Energy Functional | ( E_V[n] = F[n] + \int V(\mathbf{r})n(\mathbf{r})d\mathbf{r} ) | Total energy as a functional of density |

| Variational Principle | ( EV[n'] \geq EV[n_0] ) | Provides minimization approach to find ground state |

Bridging Theory and Practice: The Kohn-Sham Equations

The Kohn-Sham Ansatz

While the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems establish the theoretical foundation, they do not provide a practical method for computing the ground state energy and density. The key challenge lies in the unknown form of the universal functional F[n], particularly the kinetic energy component which is difficult to express as a functional of the density [1].

Kohn and Sham addressed this problem by introducing a revolutionary approach: they considered an auxiliary system of N non-interacting electrons that experience an effective potential ( V_{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) ) designed to yield the same ground state density as the real, interacting system [1]. For this non-interacting system, the ground state wavefunction is a single Slater determinant composed of the N lowest-energy orbitals φᵢ.

The Kohn-Sham approach separates the universal functional into computationally tractable components: [ F[n] = Ts[n] + EH[n] + E_{xc}[n] ] where:

- ( T_s[n] ) is the kinetic energy of the non-interacting reference system

- ( E_H[n] ) is the classical Hartree (electrostatic) energy

- ( E_{xc}[n] ) is the exchange-correlation energy functional that captures all remaining many-body effects [1]

The Kohn-Sham Equations

Through functional differentiation, Kohn and Sham derived a set of self-consistent equations that determine the orbitals and density of the auxiliary system:

The electron density is constructed from the Kohn-Sham orbitals: [ n(\mathbf{r}) = \sum{i=1}^N |\phii(\mathbf{r})|^2 ]

The effective potential is defined as: [ V{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) = V(\mathbf{r}) + VH(\mathbf{r}) + V{xc}(\mathbf{r}) ] where ( VH(\mathbf{r}) = \frac{\delta EH}{\delta n(\mathbf{r})} ) is the Hartree potential and ( V{xc}(\mathbf{r}) = \frac{\delta E_{xc}}{\delta n(\mathbf{r})} ) is the exchange-correlation potential [1].

The Kohn-Sham orbitals satisfy the one-electron Schrödinger-like equations: [ \left[ -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 + V{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) \right] \phii(\mathbf{r}) = \varepsiloni \phii(\mathbf{r}) ] [1]

These equations must be solved self-consistently because the effective potential depends on the density, which itself is constructed from the orbitals. The total energy can then be expressed as: [ E = Ts[n] + \int V(\mathbf{r})n(\mathbf{r})d\mathbf{r} + EH[n] + E_{xc}[n] ]

Table 2: Components of the Kohn-Sham Energy Functional

| Energy Component | Mathematical Form | Description | Treatment in KS-DFT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-interacting Kinetic Energy | ( Ts[n] = \sum{i=1}^N \langle \phi_i | -\frac{1}{2} \nabla^2 | \phi_i \rangle ) | Kinetic energy of reference system | Exact via orbitals |

| External Potential Energy | ( E_{\text{ext}}[n] = \int V(\mathbf{r})n(\mathbf{r})d\mathbf{r} ) | Electron-nuclear attraction | Exact | ||

| Hartree Energy | ( E_H[n] = \frac{1}{2} \int \frac{n(\mathbf{r})n(\mathbf{r}')}{ | \mathbf{r}-\mathbf{r}' | } d\mathbf{r}d\mathbf{r}' ) | Classical electron repulsion | Exact |

| Exchange-Correlation Energy | ( E_{xc}[n] ) | All many-body effects | Approximated |

Approximations and Benchmarking in Practical Applications

Exchange-Correlation Functionals

The accuracy of DFT calculations critically depends on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation functional ( E_{xc}[n] ), which remains unknown [1]. The development of increasingly sophisticated functionals represents an ongoing research area, with each approximation offering different trade-offs between accuracy and computational cost.

Local Density Approximation (LDA) assumes the exchange-correlation energy per electron at point r equals that of a uniform electron gas with the same density: [ E{xc}^{\text{LDA}}[n] = \int n(\mathbf{r}) \varepsilon{xc}^{\text{unif}}(n(\mathbf{r})) d\mathbf{r} ] where ( \varepsilon_{xc}^{\text{unif}}(n) ) is the exchange-correlation energy per particle of a homogeneous electron gas of density n [1]. While LDA works reasonably well for systems with slowly varying densities, such as simple metals, it has significant limitations for molecular systems and strongly correlated materials [1].

Generalized Gradient Approximations (GGA) improve upon LDA by including the density gradient as an additional variable: [ E{xc}^{\text{GGA}}[n] = \int n(\mathbf{r}) \varepsilon{xc}(n(\mathbf{r}), \nabla n(\mathbf{r})) d\mathbf{r} ] This allows GGA functionals to better describe inhomogeneous electron densities, making them suitable for hydrogen bonding systems and surface studies [1] [3].

Hybrid functionals incorporate a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange into the DFT exchange-correlation functional. For example, the B3LYP functional, widely used in molecular calculations, combines DFT and HF exchange in a specific parameterized ratio [4] [5]. These functionals generally provide improved accuracy for molecular properties, reaction mechanisms, and spectroscopy [3].

Table 3: Common Exchange-Correlation Functionals in Materials and Drug Research

| Functional Type | Examples | Strengths | Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | SVWN | Simple, robust for metals | Poor for weak interactions | Bulk metals, structural properties |

| GGA | PBE, BLYP | Good for geometries, hydrogen bonding | Underestimates band gaps | Surface studies, molecular properties |

| Meta-GGA | SCAN | Accurate for diverse bonding | Higher computational cost | Complex molecular systems |

| Hybrid | B3LYP, PBE0 | Improved molecular properties | Computationally expensive | Reaction mechanisms, spectroscopy |

| Double Hybrid | DSD-PBEP86 | High accuracy for energies | Very expensive | Excited states, barrier calculations |

Benchmarking Methodologies for Material Properties

Benchmarking DFT predictions against experimental data or high-level theoretical calculations is essential for establishing the reliability of computational methods in materials and pharmaceutical research. Recent studies have demonstrated systematic approaches for evaluating the performance of different DFT methodologies.

Elastic Property Prediction: A comprehensive benchmark study evaluated universal machine learning interatomic potentials (uMLIPs) against DFT data for nearly 11,000 elastically stable materials from the Materials Project database [6]. Such large-scale comparisons help establish the accuracy limits of computational methods for predicting mechanical properties like bulk modulus, shear modulus, and Poisson's ratio, which are critical for materials design applications [6].

Pharmaceutical Applications: In drug development, DFT benchmarking often focuses on predicting electronic properties relevant to biological activity. For instance, studies compare DFT-optimized geometries with experimental X-ray crystal structures, with typical deviations of 0.01-0.03 Å in bond lengths, demonstrating the method's reliability for molecular structure prediction [4]. Additional benchmarking involves comparing calculated vibrational frequencies with experimental IR spectra, where good correlation (R² = 0.998) has been demonstrated for organic molecules like 5-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole [4].

Redox Properties and Electronic Structure: Benchmarking studies assess the accuracy of DFT for predicting charge-related properties such as reduction potentials and electron affinities. Recent work has shown that neural network potentials trained on large DFT datasets can achieve accuracy comparable to or exceeding low-cost DFT methods for these properties, despite not explicitly incorporating charge-based physics [7]. For organometallic species, some machine learning models have demonstrated particularly promising performance, with mean absolute errors as low as 0.262 V for reduction potential prediction [7].

Experimental Protocols for DFT Validation

Structural Validation Protocol

Validating DFT-predicted molecular structures against experimental crystallographic data follows a standardized protocol:

Molecular Synthesis and Crystallization: The target compound is synthesized and crystallized for X-ray diffraction analysis. For example, 5-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole can be synthesized by reacting 4-chlorobenzoic acid with thiosemicarbazide using phosphorous oxychloride as an activating agent, followed by reflux and recrystallization from ethanol [4].

X-ray Crystallography: Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data collection is performed to determine precise molecular geometry. The crystal structure (e.g., orthorhombic space group Pna2₁ with Z = 8 molecules per unit cell) provides reference values for bond lengths, bond angles, and torsion angles [4].

Computational Optimization: The molecular structure is optimized using DFT with selected functionals (e.g., B3LYP) and basis sets (e.g., 6-31+G(d,p) or 6-311+G(d,p)) [4].

Statistical Comparison: Calculated geometrical parameters are statistically compared with experimental values. Typical successful benchmarks show average bond length deviations of 0.01-0.03 Å and good agreement for key torsion angles [4].

Electronic Property Validation

Validating electronic properties requires comparison with spectroscopic data:

Vibrational Frequency Analysis:

- Experimental FT-IR spectrum is collected

- DFT vibrational frequencies are calculated using the same functional and basis set

- Frequencies are typically scaled by an empirical factor (e.g., 0.96-0.98) to account for anharmonicity and basis set limitations

- Linear regression analysis (calculated vs observed frequencies) establishes correlation coefficient (successful when R² > 0.99) [4]

Frontier Orbital Analysis:

- HOMO-LUMO energies are calculated from DFT

- Experimental comparison through UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy

- Time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations for excited states

- Comparison of predicted vs observed absorption maxima [4]

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for DFT Benchmarking

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for DFT Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Software Packages | Materials Studio [5], BIOVIA DMol³ [5], Psi4 [7] | Electronic structure calculations | Drug design, material properties |

| Wavefunction Analysis | Multiwfn, Bader Analysis | Electron density analysis | Bonding analysis, reactive sites |

| Crystallographic Software | ORTEP, Olex2 | Crystal structure visualization | Structural validation |

| Force Field Packages | GFN2-xTB [7], g-xTB [7] | Semiempirical calculations | Pre-optimization, molecular dynamics |

| Benchmarking Databases | Materials Project [6], OMol25 [7] | Reference data sources | Method validation, training sets |

The Hohenberg-Kohn theorems and Kohn-Sham equations together provide the rigorous theoretical foundation and practical computational framework that make modern DFT calculations possible. For researchers benchmarking DFT predictions in materials science and pharmaceutical development, understanding these core principles is essential for selecting appropriate methodologies, interpreting computational results, and assessing reliability against experimental data. While the fundamental theory is formally exact, practical applications require careful selection of exchange-correlation functionals and thorough validation against experimental benchmarks. The ongoing development of more sophisticated functionals, coupled with large-scale benchmarking studies and integration with machine learning approaches, continues to expand the capabilities of DFT for predicting material properties and optimizing drug candidates with increasing accuracy and efficiency.

Diagram: Logical Flow from Hohenberg-Kohn to Kohn-Sham

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as the most widely used electronic structure method for predicting the properties of molecules and materials. [8] In principle, DFT offers an exact reformulation of the many-body Schrödinger equation by focusing on the electron density rather than the complex many-body wavefunction. However, this theoretical elegance meets a formidable practical obstacle: the exchange-correlation (XC) functional, which encapsulates all quantum mechanical many-body effects, is unknown and must be approximated. [8] [9] The accuracy of any DFT calculation hinges entirely on the quality of this approximation, making the quest for better XC functionals the central challenge in the field.

This guide examines the current landscape of XC functional development, with particular emphasis on benchmarking methodologies essential for materials property research. We explore traditional approaches rooted in physical constraints and empirical parameterization, as well as emerging paradigms leveraging machine learning and hybrid methodologies. For researchers in materials science and drug development, understanding these advancements is crucial for selecting appropriate computational tools and interpreting results with appropriate caution.

Theoretical Framework: The Jacob's Ladder of Approximations

The Hierarchy of XC Functionals

XC functionals are broadly categorized using a conceptual framework known as Jacob's ladder, introduced by Perdew, which classifies functionals according to the physical information they incorporate. [9] As one ascends the rungs, functionals theoretically become more accurate by including more sophisticated physical ingredients:

- Local Spin Density Approximations (LSDA): The first rung, relying only on the local electron density at each point in space.

- Generalized Gradient Approximations (GGA): Incorporate both the local electron density and its gradient, providing improved accuracy for molecular properties. The PBE (Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof) functional is a widely used example. [10] [11]

- Meta-GGAs: Include the kinetic energy density in addition to the electron density and its gradient, offering better description of transition metal complexes and reaction barriers.

- Hybrid Functionals: Mix a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange, significantly improving accuracy for band gaps and reaction energies. The HSE06 functional is particularly notable for solid-state systems. [10] [11]

- Double Hybrids: Incorporate both exact exchange and perturbative correlation corrections, representing the current pinnacle of traditional functional development.

The Fundamental Trade-off: Accuracy vs. Computational Cost

A persistent challenge in functional development lies in the inherent trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency. Traditional semi-local functionals (LDA, GGA, meta-GGA) offer favorable computational scaling but suffer from systematic errors, particularly for materials with strongly correlated electrons or complex bonding environments. [10] [9] Hybrid functionals like HSE06 provide improved accuracy but at significantly higher computational cost—often 2-3 orders of magnitude greater than semi-local approximations—limiting their application to large systems or high-throughput screening. [10]

Table 1: Classification of Exchange-Correlation Functionals by Rung on Jacob's Ladder

| Rung | Functional Type | Key Ingredients | Representative Examples | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local Density Approximation (LDA) | Local electron density | SVWN | Homogeneous electron gas, simple metals |

| 2 | Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) | Electron density + its gradient | PBE, PBEsol | General purpose materials simulation |

| 3 | Meta-GGA | Electron density, gradient, kinetic energy density | SCAN, TPSS | Complex materials, reaction barriers |

| 4 | Hybrid | Mix of DFT + exact Hartree-Fock exchange | HSE06, PBE0 | Band gaps, excited states, molecular energetics |

| 5 | Double Hybrid | Hybrid + perturbative correlation | B2PLYP | High-accuracy thermochemistry |

Current State-of-the-Art: Beyond Traditional Approximations

Machine Learning-Enabled Functionals

A paradigm shift in functional development has emerged with the integration of deep learning techniques. Microsoft Research's Skala functional exemplifies this approach, bypassing hand-designed features by learning representations directly from data. [8] Skala achieves chemical accuracy (errors below 1 kcal/mol) for atomization energies of small molecules while retaining the computational efficiency typical of semi-local DFT. [8] This performance is enabled by training on an unprecedented volume of high-accuracy reference data generated using computationally intensive wavefunction-based methods. Notably, Skala systematically improves with additional training data covering diverse chemistry, suggesting a path toward increasingly accurate and transferable functionals. [8]

Hybrid Approaches for Strong Correlation

Strongly correlated systems present particular challenges for conventional DFT approximations. Recent methodological innovations combine DFT with other theoretical frameworks to address these limitations:

DFA 1-RDMFT: This hybrid approach combines Kohn-Sham DFT with 1-electron Reduced Density Matrix Functional Theory (1-RDMFT) to capture strong correlation effects at mean-field computational cost. [9] The methodology uses the 1-RDM to describe strong correlation through fractional occupation numbers while employing traditional XC functionals to capture remaining dynamical correlation effects. [9]

Hubbard U Corrections: For systems with localized d- or f-electrons, the DFT+U approach incorporates an on-site Coulomb interaction parameter (U) to improve description of electron localization. Studies on materials like MoS₂ show that while PBE+U can improve lattice parameters, it may have minimal impact on band gap prediction without additional corrections. [10]

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Select XC Functionals for Material Properties

| Functional | Type | Band Gap Error (eV) | Lattice Constant Error (%) | Computational Cost Relative to PBE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE | GGA | ~100% underestimation | 0.5-2% overestimation [10] | 1.0x |

| PBE+U | GGA+U | Varies significantly | 1-3% underestimation [10] | 1.1-1.3x |

| HSE06 | Hybrid | ~50% improvement over PBE [11] | <1% error [10] | 10-1000x |

| SCAN | Meta-GGA | ~30% improvement over PBE | Improved over PBE [11] | 2-5x |

| Skala | Machine Learning | Competitive with best hybrids [8] | Not specified | Similar to semi-local [8] |

Benchmarking Methodologies: Protocols for Validation

Reference Data and Validation Metrics

Robust benchmarking requires carefully curated datasets and appropriate validation metrics:

High-Accuracy Reference Data: As demonstrated by the Skala functional, training and validation against extensive wavefunction-based reference data (e.g., coupled cluster theory) or experimental measurements is essential. [8] The Microsoft Research Accurate Chemistry Collection (MSR-ACC) represents one such effort, comprising the largest high-accuracy dataset ever built for training deep-learning DFT models. [8]

Error Metrics: Key metrics include Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD), and systematic error analysis across different chemical domains. For band gaps of binary systems, HSE06 reduces the MAE from 1.35 eV (PBE) to 0.62 eV compared to experimental data. [11]

Materials-Specific Benchmarking Protocols

Different material classes require tailored benchmarking approaches:

Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (e.g., MoS₂): Benchmarking should assess lattice parameters, band gaps, and electronic properties. For MoS₂, HSE06 significantly improves band gap accuracy compared to PBE, though careful attention to magnetic ordering and spin configurations is necessary. [10] [11]

Oxides for Catalysis and Energy: Evaluation should include formation energies, thermodynamic stability (via convex hull analysis), and electronic properties. Hybrid functionals like HSE06 provide more reliable phase stability predictions and improved band gaps for transition metal oxides. [11]

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for DFT and XC Functional Development

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Codes | Quantum ESPRESSO [10], FHI-aims [11] | Software packages implementing DFT with various XC functionals | Geometry optimization, electronic structure calculation |

| Reference Databases | Materials Project [11], MSR-ACC [8] | Collections of calculated and experimental material properties | Training ML functionals, benchmarking new methods |

| XC Functional Libraries | LibXC [9] | Comprehensive libraries of XC functionals | Systematic testing of different approximations |

| Wavefunction Methods | Coupled Cluster, GW [10] | High-accuracy reference methods | Generating training data, benchmarking DFT results |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Skala training infrastructure [8] | Platforms for developing ML-enhanced functionals | Creating next-generation XC functionals |

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The field of XC functional development continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising research directions:

Task-Specific Functionals: Rather than seeking a universal functional, developing specialized functionals optimized for particular material classes or properties. The DFA 1-RDMFT approach represents progress in this direction for strongly correlated systems. [9]

Improved Hybrid Methodologies: Reducing the computational cost of hybrid functionals through improved algorithms or approximations, making them more accessible for high-throughput screening and large systems.

Integration of Machine Learning: Expanding beyond functional development to using machine learning for predicting materials properties directly, potentially bypassing traditional DFT calculations altogether in some applications.

Approximating the exchange-correlation functional remains the central challenge in density functional theory, determining the practical utility of DFT simulations across chemistry, materials science, and drug development. While traditional approaches based on physical constraints and empirical parameterization continue to provide valuable tools, emerging methodologies leveraging machine learning and hybrid theories offer promising paths toward more accurate and computationally efficient approximations.

For researchers engaged in materials property prediction, rigorous benchmarking against high-accuracy reference data and critical assessment of functional limitations for specific material classes are essential practices. The ongoing development of comprehensive materials databases, sophisticated benchmarking protocols, and novel functional forms ensures that DFT will continue to evolve as an indispensable tool for predictive materials modeling.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as a cornerstone computational method in material properties research, enabling the prediction and analysis of electronic structures, reaction mechanisms, and material characteristics. Despite decades of advancements and thousands of successful applications contributing to its general reliability, particularly in main group chemistry, the method possesses well-documented systematic limitations that can significantly impact predictive accuracy if unrecognized [12]. Within the critical context of benchmarking DFT predictions for material properties, understanding these limitations transitions from academic exercise to practical necessity. The reliability of computational models depends fundamentally on recognizing where they fail, enabling researchers to make informed decisions about functional selection, error anticipation, and results interpretation. This technical guide examines three pervasive sources of DFT error—Self-Interaction Error, charge-transfer state inaccuracies, and strong correlation problems—providing a structured framework for their identification, quantification, and mitigation within rigorous benchmarking protocols.

The challenge is particularly acute because multiple error sources can intertwine within a single reaction or material system. Recent studies highlight that even for synthetically relevant organic reactions, unexpected functional disagreements of 8–13 kcal/mol can persist among modern, hybrid, higher-rung functionals, confounding conventional consensus-based model selection strategies [12]. Such discrepancies underscore the need for deeper, more systematic error analysis beyond statistical benchmarking alone. By framing these systematic errors within a benchmarking paradigm, this guide aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the diagnostic tools needed to enhance the predictive power of their computational materials research.

Theoretical Foundations of Systematic Errors in DFT

The Self-Interaction Error (SIE)

Fundamental Definition and Physical Origin

The Self-Interaction Error (SIE) originates from the imperfect cancellation in approximate Density Functional Approximations (DFAs) between the Coulomb energy of an electron density interacting with itself and the corresponding exchange term. In exact DFT, these components would perfectly cancel for a one-electron system, but practical functionals exhibit a nonphysical residual interaction of an electron with itself [12]. This intrinsic error leads to overly delocalized electron densities, as the approximate functional fails to sufficiently penalize this unphysical self-repulsion.

The formal consequence is a delocalization error that manifests across diverse chemical phenomena. SIE affects predicted bond dissociation energies, reaction barriers, σ-hole interactions, and the stability of radical and ionic complexes [12]. The error is particularly pronounced in systems where electron localization is energetically favorable, as standard DFAs tend to artificially stabilize delocalized electronic states.

Quantitative Impact and Diagnostic Approaches

The energetic implications of SIE can be systematically decomposed through modern error analysis techniques. The total DFT error with respect to the exact electronic energy can be separated into density-driven (ΔEdens) and functional (ΔEfunc) components according to the equation:

| Error Component | Mathematical Definition | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Total Error (ΔE) | ΔE = EDFT[ρDFT] − E[ρ] | Total deviation from exact energy |

| Density-Driven Error (ΔEdens) | ΔEdens = EDFT[ρDFT] − EDFT[ρ] | Energy error due to inaccurate self-consistent density |

| Functional Error (ΔEfunc) | ΔEfunc = EDFT[ρ] − E[ρ] | Energy error due to imperfect functional with exact density |

This decomposition, pioneered by Burke and coworkers, provides a critical diagnostic tool [12]. The density-driven component specifically quantifies the energy penalty arising from SIE-induced density delocalization. A practical approach to estimate this error involves comparing results from self-consistent DFT calculations with those obtained using the SIE-free Hartree-Fock density in a method termed HF-DFT [12]. The sensitivity of the energy to this density substitution serves as an operational indicator of SIE significance.

Charge-Transfer States

The Challenge of Long-Range Electron Transfer

Charge-transfer (CT) states involve the electronic transition between spatially separated donor and acceptor orbitals, a situation common in photochemical processes, catalytic systems, and organic semiconductors. Standard semi-local and hybrid density functionals with insufficient non-local exchange dramatically underestimate the energies of these states due to the inherent self-interaction error that artificially stabilizes the charge-separated state [12].

The failure is particularly severe when the donor and acceptor fragments are well-separated, as the approximate functional cannot correctly describe the ( \frac{1}{r} ) dependence of the electron-hole interaction. This leads to inaccurate predictions in key material properties including optical absorption spectra, excited-state energy landscapes, and charge separation efficiencies in photovoltaic materials.

Characterization and Identification

Diagnosing CT state inaccuracies typically involves analyzing the spatial overlap between occupied and virtual orbitals involved in electronic transitions. A characteristic signature of problematic CT states is minimal orbital overlap combined with an underestimated excitation energy. Range-separated hybrid functionals, which incorporate increasing exact exchange at long range, have proven effective in mitigating these errors, though they require careful parameter tuning for different chemical systems [7].

Benchmarking against high-level wavefunction methods like CCSD(T) or experimental UV-Vis and emission spectroscopy provides the most reliable validation for CT state predictions. For charge-related properties like electron affinity and reduction potential, modern neural network potentials trained on large datasets like OMol25 have shown promising accuracy, sometimes surpassing standard DFT functionals despite not explicitly modeling Coulombic physics [7].

Strong Correlation

The Multi-Reference Character Challenge

Strong electron correlation arises in systems where a single Slater determinant provides an inadequate description of the electronic ground state, necessitating a multi-reference treatment. This occurs in molecular systems with degenerate or near-degenerate orbitals, including transition metal complexes (particularly those with open d- or f-shells), bond dissociation regions, diradicals, and extended π-systems [12].

Standard DFT approximations, rooted in single-reference formalism, struggle with strongly correlated systems because they cannot accurately represent the static correlation energy essential for correct wavefunction description. The functional development that successfully addresses dynamic correlation often fails for static correlation, leading to significant errors in predicted reaction energies, spin-state ordering, and electronic properties.

Manifestations in Material Properties

The practical consequences include incorrect predictions of magnetic coupling in coordination polymers, inaccurate band gaps in correlated electron materials, and erroneous reaction mechanisms for catalytic processes involving transition metals. For instance, in high-energy materials (HEMs) composed of C, H, N, and O elements—a critical class for aerospace and defense applications—strong correlation effects can impact the prediction of mechanical stability and decomposition pathways [13].

Diagnosing strong correlation requires careful electronic structure analysis. Indicators include symmetry-broken solutions, unphysically low reaction barriers, and incorrect spin densities. Wavefunction stability analysis and comparison with multi-reference methods like CASSCF provide definitive identification, though these approaches are computationally demanding for the large systems typical in materials research.

Quantitative Analysis of DFT Error Magnitudes

Comparative Error Metrics Across Chemical Systems

Systematic benchmarking reveals significant variations in DFT error magnitudes depending on the chemical system, property of interest, and functional employed. The following table summarizes representative error ranges for the discussed systematic errors across different chemical contexts:

Table 2: Quantitative Error Ranges for Systematic DFT Limitations

| Error Type | Affected System/Property | Representative Error Magnitude | High-Accuracy Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Interaction Error | Organic reaction barriers | 8-13 kcal/mol functional spread [12] | LNO-CCSD(T)/CBS |

| Bond dissociation energies | Up to 20-30 kcal/mol for stretched bonds | CCSD(T) | |

| Charge-Transfer Errors | CT excitation energies | Up to 1-2 eV underestimation | EOM-CCSD |

| Electron Affinities (Main-Group) | MAE: 0.26-0.51 eV (DFT) vs 0.26-0.41 eV (NNPs) [7] | Experimental gas-phase values | |

| Reduction Potentials (Organometallic) | MAE: 0.26-0.41 V (DFT/NNPs) [7] | Experimental electrochemical data | |

| Strong Correlation | Transition metal spin-state energies | Often 5-15 kcal/mol errors | CASPT2/DMRG |

| Reaction energies in open-shell systems | 10-20 kcal/mol for challenging cases | CCSD(T) |

Performance Variation Across Functional Types

The sensitivity to these systematic errors varies considerably across the DFT functional landscape. Modern hybrid functionals with significant exact exchange admixture (e.g., ωB97X-D, M06-2X) generally mitigate SIE and CT errors but may exacerbate problems for strongly correlated systems. Conversely, semi-local functionals often better describe strong correlation but fail dramatically for CT excitations and barrier predictions.

Unexpected performance variations can occur even within functional classes. For example, in a study of C–C and C–O bond formation reactions, a spread of 8–13 kcal/mol persisted among advanced hybrid and higher-rung functionals like ωB97X-D, B3LYP-D3, and M06-2X, complicating simple consensus-based model selection [12]. This underscores the necessity for system-specific benchmarking rather than reliance on generalized functional rankings.

Methodological Protocols for Error Diagnosis and Mitigation

Diagnostic Workflow for Systematic Error Identification

Implementing a systematic diagnostic protocol is essential for reliable DFT applications in materials research. The following workflow provides a structured approach for identifying potential error sources:

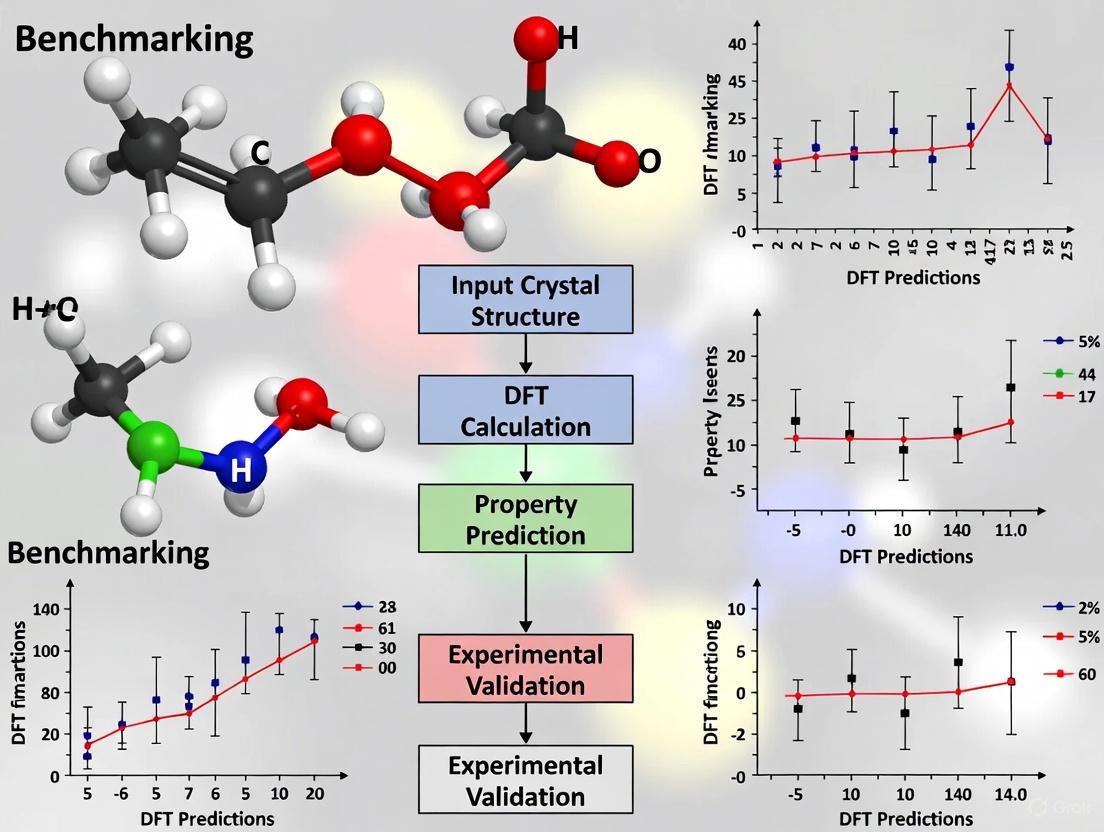

Figure 1: DFT Error Diagnostic Workflow. A systematic approach for identifying and addressing common DFT limitations in materials research.

Advanced Reference Methods for Benchmarking

Gold-Standard Wavefunction Theory

Coupled cluster theory with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations [CCSD(T)] remains the gold standard for benchmarking DFT predictions, offering ~1 kcal/mol chemical accuracy within its applicability domain [12]. Recent methodological advances, particularly local correlation approaches like local natural orbital (LNO) CCSD(T), have dramatically expanded the accessible system size while maintaining rigorous error control.

These methods enable robust benchmarking for systems with dozens of atoms, providing reliable reference data for functional assessment. For example, in diagnosing unexpected functional disagreements for organic reactions, LNO-CCSD(T) references with complete basis set (CBS) extrapolation provided definitive benchmarks with 0.1–0.3 kcal/mol uncertainty, enabling clear identification of problematic DFT performance [12].

Machine Learning Potentials as Complementary Tools

Neural network potentials (NNPs) trained on large quantum chemical datasets are emerging as valuable complementary tools for DFT benchmarking. The recently developed EMFF-2025 model provides DFT-level accuracy for predicting structures, mechanical properties, and decomposition characteristics of high-energy materials containing C, H, N, and O elements [13]. Similarly, OMol25-trained NNPs have demonstrated competitive performance for charge-related properties like electron affinity and reduction potential, sometimes surpassing standard DFT functionals despite not explicitly modeling Coulombic interactions [7].

These ML-based approaches offer rapid property prediction across diverse chemical spaces, enabling broader functional validation than feasible with direct wavefunction methods alone. However, their transferability requires careful assessment, particularly for systems far from the training data distribution.

Table 3: Computational Tools for DFT Error Diagnosis and Mitigation

| Tool Category | Specific Methods/Functionals | Primary Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIE Diagnostics | HF-DFT [12], Density sensitivity analysis | Quantifying density-driven errors | Particularly valuable for delocalization-prone systems |

| CT-State Mitigation | Range-separated hybrids (ωB97X-D, LC-ωPBE) [7], Tuned functionals | Charge-transfer excitations, Long-range interactions | Range-separation parameter may need system-specific tuning |

| Strong Correlation | Hybrid DFT with moderate exact exchange, DFT+U, Multi-reference methods | Transition metal complexes, Diradicals, Bond breaking | Balance between static and dynamic correlation treatment |

| Reference Methods | LNO-CCSD(T)/CBS [12], DLPNO-CCSD(T), CASSCF/PT2 | Benchmarking, Validation | Computational cost vs. accuracy trade-offs |

| Machine Learning Potentials | EMFF-2025 [13], OMol25 NNPs [7] | Rapid screening, Large-scale validation | Training data representation and transferability |

Systematic errors in Density Functional Theory present significant but manageable challenges in computational materials research. The self-interaction error, charge-transfer state inaccuracies, and strong correlation problems each demand specific diagnostic approaches and mitigation strategies. Through rigorous benchmarking protocols incorporating modern error decomposition techniques and gold-standard reference methods, researchers can not only identify functional limitations but also select more reliable models for specific material systems and properties.

The evolving toolkit for addressing these challenges—from density-sensitivity analysis and range-separated hybrids to neural network potentials trained on extensive quantum chemical datasets—provides a pathway toward more predictive materials modeling. By systematically recognizing, diagnosing, and accounting for these common DFT failures, researchers and drug development professionals can enhance the reliability of computational predictions, ultimately accelerating the discovery and optimization of novel materials with tailored properties.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as a cornerstone computational method for investigating the electronic structure of atoms, molecules, and materials. Its foundational principle is both powerful and exact: all ground-state properties of a many-electron system can be uniquely determined by its electron density, ρ(r), a function of only three spatial coordinates. This represents an extraordinary simplification over the intractable many-electron wavefunction. The theoretical exactness of DFT is rigorously established by the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems [14]. The first theorem proves a one-to-one correspondence between the ground-state electron density and the external potential, thereby uniquely defining the Hamiltonian and all system properties. The second theorem provides a variational principle, stating that the correct ground-state density minimizes the total energy functional of the system [14].

However, this exact theoretical framework contains a critical, unknown component: the exchange-correlation (XC) energy functional, which encapsulates all complex many-body electron interactions. In practical computation, this exact functional must be replaced by explicit, approximate Density Functional Approximations (DFAs). This substitution is the origin of the fundamental dichotomy: while DFT itself is exact, its practical application is inherently approximate. DFAs thus serve as the essential, yet imperfect, bridge that enables the widespread use of DFT across chemistry and materials science, but they also introduce varying degrees of error that must be carefully managed [14] [15].

The Unavoidable Approximation: Exchange-Correlation Functionals

The Jacob's Ladder of DFAs

The development of DFAs is often conceptualized as a climb up "Jacob's Ladder," a hierarchy of approximations that progressively incorporate more sophisticated descriptions of the electron density in the pursuit of "chemical accuracy." [15].

| Rung | Functional Type | Description | Key Inputs | Representative Examples | Typical Computational Cost | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local Density Approximation (LDA) | Treats the electron density as a uniform electron gas. | Local electron density, ρ | SVWN5 | Low | ||

| 2 | Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) | Accounts for the gradient of the density for inhomogeneity. | ρ, | ∇ρ | PBE, PBEsol, BLYP | Low to Medium | |

| 3 | Meta-GGA | Incorporates the kinetic energy density for orbital localization. | ρ, | ∇ρ | , τ | SCAN, TPSS | Medium |

| 4 | Hybrid | Mixes a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFA exchange. | ρ, | ∇ρ | , τ, Exact Exchange | PBE0, HSE06, B3LYP | High |

| 5 | Double Hybrid & Machine-Learned | Combines hybrid functional with perturbative correlation or uses ML models. | ρ, | ∇ρ | , Exact Exchange, MP2 correlation / Learned features | DSDPBEP86, Skala | Very High |

The ascent up this ladder generally yields improved accuracy for properties like atomization energies and band gaps but comes at a significantly increased computational cost [10] [15]. For instance, the hybrid functional HSE06, which mixes a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange, is well-documented for providing more accurate electronic properties, such as band gaps, compared to GGA functionals like PBE [10] [11].

The Grand Challenge: Accuracy vs. Generality

The central challenge in DFA development lies in the trade-off between accuracy and computational cost, compounded by the lack of a universal functional that performs well across all regions of chemical space. As one expert notes, despite being used by thousands of scientists yearly, DFT's limited accuracy means it is "still mostly used to interpret experimental results rather than predict them" [15].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Select DFAs for Different Material Properties

| Material / Property | PBE (GGA) | PBE+U | HSE06 (Hybrid) | Experimental Reference | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoS₂ Band Gap (eV) | ~1.7 eV (Underestimated) | Minimal impact on gap | ~2.0 eV (Improved accuracy) | ~2.1 eV (Experimental) | GGA underestimates band gaps due to self-interaction error [10]. |

| MoS₂ Lattice Parameters | Slight Overestimation | Slight Underestimation (electron localization) | Improved Accuracy (vs. PBE) | Varies with measurement | Different DFAs optimize different properties; no single winner [10]. |

| Formation Energies (General Oxides) | Baseline | - | Lower than PBE/PBEsol (MAD: 0.15 eV/atom) | Limited experimental data | Challenging to benchmark comprehensively [11]. |

| Supramolecular Dimers Dispersion Energy | Poor without a posteriori correction | - | - | SAPT-DFT Benchmark | Standard dispersion corrections (e.g., D3) may underestimate true dispersion energy [16]. |

A critical limitation of many DFAs is their inaccurate treatment of noncovalent interactions, such as van der Waals (vdW) dispersion forces. These interactions are crucial in supramolecular chemistry and biomolecular systems. As highlighted in recent research, "Most of the popular vdW methods... treat vdW dispersion as a posteriori energy correction without accounting for the resulting vdW polarization of ρ(r)" [16]. This means that while energy corrections can be added, the underlying electron density—and thus properties derived from it like electrostatic potentials—remains uncorrected, limiting the predictive power for such systems.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking DFT Predictions

To assess the accuracy of different DFAs, researchers rely on rigorous benchmarking against highly accurate reference data, typically from experimental results or advanced, computationally expensive wavefunction methods.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Electronic and Structural Properties of Solids

This protocol is standard in materials science for evaluating a DFA's ability to predict structural and electronic properties.

- Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the performance of various DFAs (e.g., PBE, PBE+U, HSE06) in predicting the lattice constants and electronic band gaps of crystalline solids like MoS₂ [10].

- Methodology:

- Structure Selection: Obtain an initial crystal structure from a database like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD).

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a full geometry optimization (atomic positions and lattice vectors) using a baseline functional (e.g., PBEsol, which provides good lattice constants). A force convergence criterion of, for example, 10⁻³ eV/Å is typically used [11].

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: Using the optimized geometry, perform a single-point energy and electronic structure calculation with the target higher-level functional (e.g., HSE06).

- Property Calculation: Extract the target properties: the final lattice parameters and the electronic band gap from the computed electronic density of states or band structure.

- Benchmarking: Compare the computed values against reliable experimental data or high-level theoretical benchmarks. Key metrics include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) or Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD).

Protocol 2: Assessing Thermochemical Accuracy for Molecules

This approach is crucial for molecular chemistry and drug design, where predicting reaction energies correctly is paramount.

- Objective: To determine the error in a DFA's prediction of molecular atomization energies—the energy required to separate a molecule into its constituent atoms—against a benchmark dataset like W4-17 [15].

- Methodology:

- Reference Data Generation: Generate a large, diverse set of molecular structures. Compute their reference atomization energies using highly accurate (but expensive) wavefunction methods like CCSD(T) or related benchmarks. This requires substantial computational resources and expertise [15].

- DFA Computation: For each molecule in the dataset, compute the atomization energy using the DFA under investigation.

- Error Analysis: Calculate the error for each molecule as: Error = EDFA - EReference. Statistical analysis across the entire dataset (e.g., MAE, root-mean-square error) reveals the functional's overall accuracy and its "chemical accuracy," typically defined as an error of ~1 kcal/mol.

- Generalization Test: The most robust tests train the DFA on one set of molecules and evaluate its performance on a completely unseen set to confirm its generalizability [15].

Diagram 1: Workflow for benchmarking DFAs on solid-state materials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Computational "Reagents" for DFT Research

| Tool Name / Category | Primary Function | Key Features / Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Plane-wave DFT code | Uses pseudopotentials; popular for solid-state physics; used for MoS₂ studies [10]. |

| FHI-aims | All-electron DFT code | Uses numeric atom-centered orbitals; high accuracy for materials; used for hybrid-functional database generation [11]. |

| PySCF | Python-based chemistry framework | Flexible for molecular systems; used for implementing and testing new functionals like DM21 [14]. |

| VASP | Plane-wave DFT code | Widely used for materials modeling; supports many DFAs and perturbation theory. |

| DFT-D3 | Empirical dispersion correction | A posteriori energy correction for vdW forces; improves binding energies but not electron density [16]. |

| SISSO | AI for materials modeling | Sure-Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator; creates interpretable AI models for material properties from DFT data [11]. |

Emerging Frontiers: Machine-Learned and Data-Driven DFAs

A paradigm shift is underway with the introduction of machine learning (ML) to directly learn the XC functional from large volumes of high-accuracy data. This approach aims to overcome the limitations of hand-designed analytical approximations.

Deep learning models, such as the Skala functional developed by Microsoft Research, leverage scalable architectures to learn meaningful representations from electron densities. Trained on a dataset "two orders of magnitude larger than previous efforts," Skala has demonstrated accuracy "required to reliably predict experimental outcomes" for main group molecules, a significant milestone [15]. Similarly, neural network potentials (NNPs) like EMFF-2025 are being developed to achieve DFT-level accuracy in molecular dynamics simulations at a fraction of the computational cost, creating a powerful link between electronic structure and macroscopic properties [13].

However, these ML-based functionals face their own challenges. Neural network functionals can exhibit non-smooth behavior and oscillations, particularly when calculating derivatives critical for geometry optimization [14]. Their "black box" nature also raises concerns about interpretability and transferability to systems outside their training data. As one study notes, "the reliability of these functionals in practical scenarios with geometry optimization remains an open question" [14].

Diagram 2: The workflow and challenges of developing machine-learned density functionals.

The distinction between the exact theoretical framework of DFT and the approximate nature of its practical implementations via DFAs is fundamental. This dichotomy arises from the unavoidable need to approximate the universal exchange-correlation functional. While the progressive climb up Jacob's Ladder and the strategic application of DFAs like HSE06 have steadily improved accuracy for specific properties, no single functional is universally superior. The emergence of machine-learned functionals trained on extensive, high-fidelity data represents a promising frontier, potentially overcoming long-standing accuracy plateaus. For researchers in material science and drug development, a rigorous and critical approach to selecting, applying, and benchmarking DFAs—with a clear understanding of their inherent limitations—remains the key to harnessing the full predictive power of Density Functional Theory.

Selecting and Applying Density Functionals: A Guide for Material and Drug Properties

Density-functional theory (DFT) serves as a cornerstone of modern computational quantum chemistry and materials science, providing a balance between computational efficiency and accuracy for predicting molecular and material properties. Unlike wavefunction-based methods that explicitly solve for the electronic wavefunction, DFT focuses on the electron density, ρ(r), as the fundamental variable. The success of DFT hinges entirely on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation (XC) functional, Exc[ρ], which incorporates all quantum many-body effects. The development of these functionals has followed a systematic path of increasing complexity and accuracy, often visualized as climbing "Jacob's Ladder" from simple to more sophisticated approximations. This progression from the Local Density Approximation (LDA) to Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA), meta-GGA, hybrid, and double-hybrid functionals represents a journey of incorporating more physical information into the functional form, each step addressing limitations of its predecessor while introducing new capabilities and, often, computational demands.

Theoretical Foundation

The Kohn-Sham Framework

The theoretical foundation of DFT rests on the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, which establish that the ground-state energy of an interacting electron system is uniquely determined by its electron density. Kohn and Sham extended this framework by introducing a system of non-interacting electrons that reproduce the same density as the true interacting system. The total energy functional in Kohn-Sham DFT is expressed as:

E[ρ] = Tₛ[ρ] + Vₑₓₜ[ρ] + J[ρ] + Eₓ꜀[ρ]

where Tₛ[ρ] is the kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons, Vₑₓₜ[ρ] is the external potential energy, J[ρ] is the classical Coulomb energy, and Eₓ꜀[ρ] is the exchange-correlation energy that encapsulates all quantum many-body effects. The critical challenge in DFT is that the exact form of Eₓ꜀[ρ] is unknown and must be approximated, leading to the diverse "zoo" of functionals discussed in this guide [17].

Key Concepts: Exchange and Correlation

Electron exchange represents the quantum mechanical effect enforcing the Pauli exclusion principle, describing the reduction in Coulomb repulsion between electrons with parallel spins due to the antisymmetry of the wavefunction. Electron correlation accounts for the interaction between electrons beyond the mean-field approximation of Hartree-Fock theory, reflecting individual electron-electron interactions. Different density functional approximations handle these effects with varying degrees of sophistication, leading to their characteristic strengths and limitations [17].

The Functional Zoo: Classification and Evolution

Local Density Approximation (LDA)

The Local Density Approximation represents the simplest and historically first practical exchange-correlation functional. LDA evaluates each point in space as if it were part of a homogeneous electron gas, with the functional depending only on the local electron density at each point [18] [17]:

Eₓ꜀ᴸᴰᴬ[ρ] = ∫ ρ(r) εₓ꜀ᴸᴰᴬ(ρ(r)) dr

Common LDA functionals include VWN (Vosko-Wilk-Nusair), PW92 (Perdew-Wang 1992), and Xalpha [18]. While computationally efficient and yielding reasonable lattice constants, LDA suffers from systematic errors including overbinding, prediction of bond lengths that are too short, and significant underestimation of exchange energy [17]. Despite these limitations, LDA remains important as a component in more advanced functionals and for certain systems where its deficiencies are less pronounced.

Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA)

GGAs introduce sensitivity to the inhomogeneity of the electron density by incorporating the density gradient (∇ρ) as an additional variable [18] [17]:

Eₓ꜀ᴳᴳᴬ[ρ] = ∫ ρ(r) εₓ꜀ᴳᴳᴬ(ρ(r), ∇ρ(r)) dr

This inclusion allows GGAs to correct LDA's overbinding tendency, generally yielding improved molecular geometries. GGA functionals can be categorized by their exchange and correlation components:

Table 1: Common GGA Functionals and Their Components

| Functional | Exchange | Correlation | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLYP | Becke (1988) | LYP | General purpose molecular calculations |

| PBE | PBEx | PBEc | Solid-state systems, materials science |

| PBEsol | PBEsolx | PBEsolc | Solids, accurate lattice constants |

| BP86 | Becke | Perdew (1986) | Molecular geometries |

| revPBE | revPBEx | PBEc | Surface chemistry |

GGAs represent a workhorse functional class in many computational domains, offering improved accuracy over LDA with minimal additional computational cost. However, they often perform poorly for energetics and systematically underestimate band gaps in semiconductors and insulators [19] [17].

Meta-Generalized Gradient Approximation (meta-GGA)

Meta-GGAs further enhance the functional form by incorporating the kinetic energy density (τ) or occasionally the Laplacian of the density (∇²ρ) [18] [17]:

Eₓ꜀ᵐᴳᴳᴬ[ρ] = ∫ ρ(r) εₓ꜀ᵐᴳᴳᴬ(ρ(r), ∇ρ(r), τ(r)) dr

where τ(r) = ½∑ᵢ|∇ψᵢ(r)|² is the kinetic energy density. This additional dependence provides information about the local character of chemical bonding and enables more accurate treatment of diverse systems.

Table 2: Select Meta-GGA Functionals and Applications

| Functional | Key Features | Applications | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCAN | Strongly constrained | General purpose, solids | Accurate for diverse bonding environments |

| TPSS | Non-empirical | Molecular systems | Good thermochemistry |

| M06-L | Empirical parameterization | Organometallics, catalysis | Good for transition metals |

| MS2 | Non-empirical | Complex oxides | Correct ground states for BiMO₃ polymorphs [20] |

| ωB97M-V | Range-separated meta-GGA | High-accuracy datasets | Used in OMol25 dataset generation [21] |

Meta-GGAs provide significantly more accurate energetics than GGAs with only slightly increased computational cost, though they can be more sensitive to integration grid quality [17]. Their improved description of electronic properties makes them particularly valuable for materials with complex electronic structures, such as transition-metal oxides [20].

Hybrid Functionals

Hybrid functionals address a key limitation of pure density functionals—self-interaction error (SIE) and incorrect asymptotic behavior—by incorporating a fraction of exact Hartree-Fock (HF) exchange [17]:

Eₓ꜀ᴴʸᵇʳⁱᵈ[ρ] = aEₓᴴᶠ[ρ] + (1-a)Eₓᴰᶠᵀ[ρ] + E꜀ᴰᶠᵀ[ρ]

where a is the mixing parameter for HF exchange (e.g., 0.2 in B3LYP). This hybrid approach provides error cancellation, as HF tends to overestimate bond lengths while pure DFT underestimates them.

Table 3: Hybrid Functional Types and Representatives

| Functional Type | Representatives | HF Mixing | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Hybrid | B3LYP, PBE0, B97-3 | Constant (e.g., 20-25%) | General purpose, good thermochemistry |

| Range-Separated Hybrid (RSH) | CAM-B3LYP, ωB97X, ωB97M | Short-range: DFT, Long-range: HF | Charge-transfer, excited states, band gaps [21] [17] |

| Screened Hybrid | HSE06 | Screened HF exchange in short-range | Solids, band structures, computationally efficient [19] [22] |

The HSE06 functional, in particular, has proven valuable for materials databases, providing more accurate electronic properties than GGA for systems with localized electronic states like transition-metal oxides, with a mean absolute error of 0.62 eV for experimental band gaps compared to 1.35 eV for PBEsol [19].

Double-Hybrid Functionals

Double-hybrid functionals represent the fifth rung of Jacob's Ladder, combining hybrid functional elements with a perturbative correlation contribution, typically from second-order Møller-Plesset (MP2) theory [18] [23]. Only the hybrid part is evaluated self-consistently, while the MP2 component is added post-SCF to the total energy [18].

Recent developments include the PBE-DH-INVEST and SOS1-PBE-DH-INVEST functionals, which show excellent performance for systems with very low singlet-triplet energy gaps (ΔEST), critical for OLED applications [23]. The ωDH25-D4 double hybrid achieves a remarkable WTMAD-2 value of 2.13 kcal/mol on the GMTKN55 test suite, among the lowest values reported for a general double-hybrid [24].

Benchmarking Methodologies and Protocols

Standard Test Sets and Validation Metrics

Rigorous benchmarking of density functionals requires well-curated datasets with high-quality reference data. Key benchmark sets include:

- GMTKN55: A diverse collection of 55 datasets for general main-group thermochemistry, kinetics, and non-covalent interactions. The WTMAD-2 (weighted mean absolute deviation) serves as a key composite metric [24].

- NAH159: Specialized dataset for organic molecules with very low (positive or negative) singlet-triplet energy gaps (ΔEST) [23].

- Wiggle150: A benchmark for conformer energies [21].

Experimental Protocol: High-Accuracy Database Construction

The creation of the OMol25 dataset exemplifies a comprehensive approach to generating reference-quality computational data [21]:

- System Selection: Curate structures from diverse chemical spaces including biomolecules (from RCSB PDB and BioLiP2), electrolytes, metal complexes (generated combinatorially with Architector package), and existing datasets (SPICE, Transition-1x, ANI-2x).

- Level of Theory: Employ a consistently high-level method (ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD) throughout for accuracy and uniformity.

- Integration Grid: Use large pruned (99,590) grids to ensure accurate gradients and non-covalent interactions.

- Sampling: Employ extensive conformational sampling (Schrödinger tools for protonation states and tautomers, smina for docked poses, restrained MD for different poses).

- Validation: Benchmark against experimental data and higher-level theories where available.

This protocol resulted in over 100 million quantum chemical calculations consuming over 6 billion CPU-hours [21].

Experimental Protocol: Materials Database with Hybrid Functionals

For solid-state materials, the protocol used in creating the all-electron hybrid functional database demonstrates appropriate methodology [19] [22]:

- Structure Selection: Query initial crystal structures from ICSD, filtering duplicates and polymorphs based on lowest energy/atom from Materials Project.

- Geometry Optimization: Perform initial optimization with PBEsol functional, which provides accurate lattice constants.

- Single-Point Energy: Calculate high-level energy and electronic properties with HSE06 functional on PBEsol-optimized structures.

- Basis Set: Use "light" numerically atom-centered orbital (NAO) basis sets in FHI-aims for optimal accuracy/efficiency balance.

- Magnetic Treatment: Perform spin-polarized calculations for potentially magnetic structures.

- Convergence: Apply force convergence criterion of 10⁻³ eV/Å.

This approach yielded a database of 7,024 inorganic materials with HSE06 properties, showing significant improvement in band gap accuracy over GGA (MAE of 0.62 eV vs. 1.35 eV) [19].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Accuracy Across Chemical Systems

Different functional classes exhibit distinct performance characteristics across various chemical systems and properties:

- Complex Oxides: For BiMO₃ (M = Al, Ga, In) polymorphs, meta-GGAs (MS2, SCAN) correctly describe crystallographic ground states where LDA, GGA, and some hybrids fail [20].

- Band Gaps: HSE06 reduces the band gap error by over 50% compared to PBEsol (MAE 0.62 eV vs. 1.35 eV) for binary systems [19].

- Singlet-Triplet Gaps: Double-hybrids like PBE-DH-INVEST provide accurate ΔEST values for challenging organic systems with very low energy gaps [23].

- Non-covalent Interactions: Range-separated meta-GGAs like ωB97M-V offer excellent performance across diverse interaction types [21].

Neural Network Potentials as Benchmarking Tools

The Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset has enabled training of neural network potentials (NNPs) like eSEN and UMA that approach the accuracy of the underlying ωB97M-V functional at dramatically reduced computational cost [21]. These models now serve as benchmarking tools themselves, with the small conservative-force eSEN model achieving "essentially perfect performance on all benchmarks" [21], potentially revolutionizing functional validation for large systems.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for DFT Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset | Reference dataset of 100M+ calculations at ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD | Training NNPs, benchmarking functional performance [21] |

| Hybrid Materials Database | 7,024 inorganic materials with HSE06 and PBEsol properties | Solid-state benchmarking, AI model training [19] [22] |

| FHI-aims | All-electron DFT code with NAO basis sets | High-accuracy materials calculations [19] [22] |

| ADF | DFT code supporting comprehensive functional range | Molecular calculations, double-hybrid functionals [18] |

| SISSO | Sure-Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator | Interpretable AI model development from materials data [19] [22] |

Decision Framework and Future Directions

Functional Selection Workflow

The following diagram provides a systematic approach for selecting density functionals based on target properties and system characteristics:

Future Perspectives

The field of density functional development is evolving toward more specialized functionals targeting specific chemical problems, while simultaneously benefiting from integration with machine learning approaches. Key trends include:

- Local Double Hybrids: Emerging range-separated local double hybrids (RSLDH) with neural network-optimized local mixing functions promise to extend the accuracy of double-hybrids while potentially improving computational efficiency [24].

- Universal Models: The Universal Models for Atoms (UMA) architecture enables knowledge transfer across disparate datasets, improving generalization [21].

- Dataset Curation: Focus is shifting from massive dataset creation to targeted curation, fine-tuning, and distillation strategies to make advanced models accessible to broader research communities [21].

As these trends continue, the functional zoo will likely expand to include more problem-specific approximations while simultaneously developing more universally accurate functionals through machine-learning enhancement and improved physical constraints.

The accuracy of Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations is critically dependent on the choice of the exchange-correlation functional, a fact that poses a significant challenge for computational researchers across chemistry and materials science. Different molecular and solid-state properties exhibit varying sensitivities to the approximations inherent in these functionals. Without careful benchmarking, computational predictions may yield quantitatively inaccurate or even qualitatively incorrect results, potentially misdirecting experimental efforts. This guide synthesizes recent benchmark studies to provide a structured framework for selecting the most appropriate functional based on the target property: electronic band gaps, thermodynamic reaction energies, or non-covalent interaction energies. By framing these findings within the broader context of methodological benchmarking for materials research, we aim to equip scientists with the knowledge to make informed, reliable computational choices that enhance the predictive power of their research.

Benchmarking for Electronic Band Gaps

The accurate prediction of band gaps is crucial for developing materials for photovoltaics, optoelectronics, and catalysis. Standard semi-local functionals are known to underestimate this property, but the degree of error and performance of corrected functionals can vary significantly across material classes.

Key Benchmarking Studies and Findings

Recent large-scale benchmarking efforts have quantified the performance of various functionals. A study on metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) found that the widely used PBE generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functional severely underpredicts band gaps compared to more accurate hybrid functionals [25]. The median band gap for MOFs calculated with PBE was significantly lower than those obtained with HSE06 (a hybrid functional containing 25% Hartree-Fock exchange) [25]. The discrepancy was particularly pronounced for MOFs with open-shell 3d transition metal cations, where PBE not only quantitatively underestimated gaps but also produced qualitatively incorrect band gap distributions compared to hybrid references [25].

Similar trends were observed in organic-inorganic metal halide perovskites. A systematic study of 24 exchange-correlation functionals found that while many standard functionals could approximately reproduce experimental band gaps (around 1.6 eV for CH₃NH₃PbI₃), their performance varied considerably [26]. The study reported that some GGA functionals, including PBE and RPBE, offered a reasonable compromise between accuracy and computational cost for these materials [26]. Furthermore, the choice of basis set also influenced accuracy, with numerical atomic orbitals (NAO) sometimes providing better agreement with experiment than plane-wave approaches [26].

For low-dimensional organic metal halide hybrids (LD-OMHHs), an unexpected finding emerged: standard GGA functionals performed similarly or even better than more sophisticated meta-GGA methods when compared to experimental band gaps [27]. This counterintuitive result was attributed to large excitonic effects in these materials, which cause a deviation between the computed fundamental gap and the experimental optical bandgap [27]. This highlights the critical importance of understanding the specific material system and the nature of the experimental data being compared.

Table 1: Performance of Select DFT Functionals for Band Gap Prediction Across Material Classes

| Material Class | Recommended Functional(s) | Typical Performance | Special Considerations | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | HSE06, HSE06*, HLE17 | PBE severely underpredicts gaps; Hybrids (HSE06) are more accurate. | Errors are larger and less predictable for open-shell 3d transition metals. | [25] |

| 3D Perovskites (e.g., CH₃NH₃PbI₃) | PBE, RPBE | Good compromise between accuracy and computational cost. | NAO basis sets can improve agreement with experiment. | [26] |

| Low-Dimensional OMHHs | GGA (e.g., PBE) | GGA aligns similarly or better vs. experiment than meta-GGAs. | Likely due to excitonic effects; SOC has limited influence. | [27] |

Experimental Protocol for Band Gap Benchmarking

To systematically benchmark functionals for band gap predictions, the following protocol, derived from the cited literature, is recommended:

- Structure Selection and Preparation: Choose a set of well-characterized materials with experimentally determined crystal structures and reliably measured band gaps. For the studies cited, this included cubic CH₃NH₃PbI₃ and FAPI perovskites [26] and a diverse subset of MOFs from the QMOF database [25].

- Computational Methodology:

- Code and Basis Set: Select a electronic structure code (e.g., CASTEP for plane waves, DMol³ for numerical atomic orbitals) and a consistent, high-quality basis set [26].

- Structure Optimization: Perform a full geometry optimization of the unit cell and atomic positions for each material, using a consistent, standard functional like PBE. Alternatively, use the experimental crystal structure directly, but this must be applied consistently across the benchmark [26].

- Single-Point Energy Calculations: Conduct single-point energy calculations with a wide range of functionals on the optimized/experimental structures. This should include LDA, GGA (e.g., PBE), meta-GGA (e.g., HLE17, SCAN), and hybrid (e.g., HSE06, PBE0) functionals [26] [25].

- Band Structure Calculation: Extract the band gap from the electronic band structure calculation for each functional. For materials with heavy elements (like Pb), calculations should be performed both with and without spin-orbit coupling (SOC) to evaluate its impact [26].

- Data Analysis: Compare the computed band gaps against the experimental reference set. Calculate the mean absolute error (MAE), mean signed error (MSE), and root-mean-square error (RMSE) for each functional to quantitatively assess its performance [25].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

Benchmarking for Thermodynamic Reaction Energies

Predicting accurate reaction energies and equilibrium compositions is fundamental to process design in catalysis and synthesis. The performance of DFT functionals for thermodynamics depends on a balance between describing electronic energies and vibrational contributions to Gibbs free energy.

Performance of Functionals for Reaction Equilibria

A comprehensive benchmark study evaluated the accuracy of six exchange-correlation functionals (PWLDA, PBE, B3-LYP, PBE0, M06, TPSS) with three basis sets (SVP, TZVP, QZVPP) for predicting the temperature-dependent equilibrium compositions of 2648 gas-phase reactions [28]. The study found that with a triple-zeta quality basis set (TZVP), all tested functionals except LDA correctly predicted the equilibrium composition for over 94% of reactions that had a constant composition below 1000 K [28]. The PBE0 and B3-LYP hybrid functionals achieved the highest accuracy at 94.8% and 94.7%, respectively, though this was only a marginal improvement over the 94.2% accuracy of the GGA functional PBE [28].

The errors in Gibbs free energy were found to originate equally from inaccuracies in the vibrational spectrum and the DFT electronic ground state energy [28]. The harmonic approximation used for vibrational contributions introduced significant errors at high temperatures (e.g., 1500 K), but these errors largely canceled out when considering energy differences between reactants and products [28].

Table 2: Accuracy of DFT Functionals for Predicting Constant Equilibrium Compositions (TZVP Basis Set) [28]

| Functional | Type | Percentage of Reactions Correctly Described (%) |

|---|---|---|

| TPSS | meta-GGA | 95.1 |

| PBE0 | Hybrid | 94.8 |