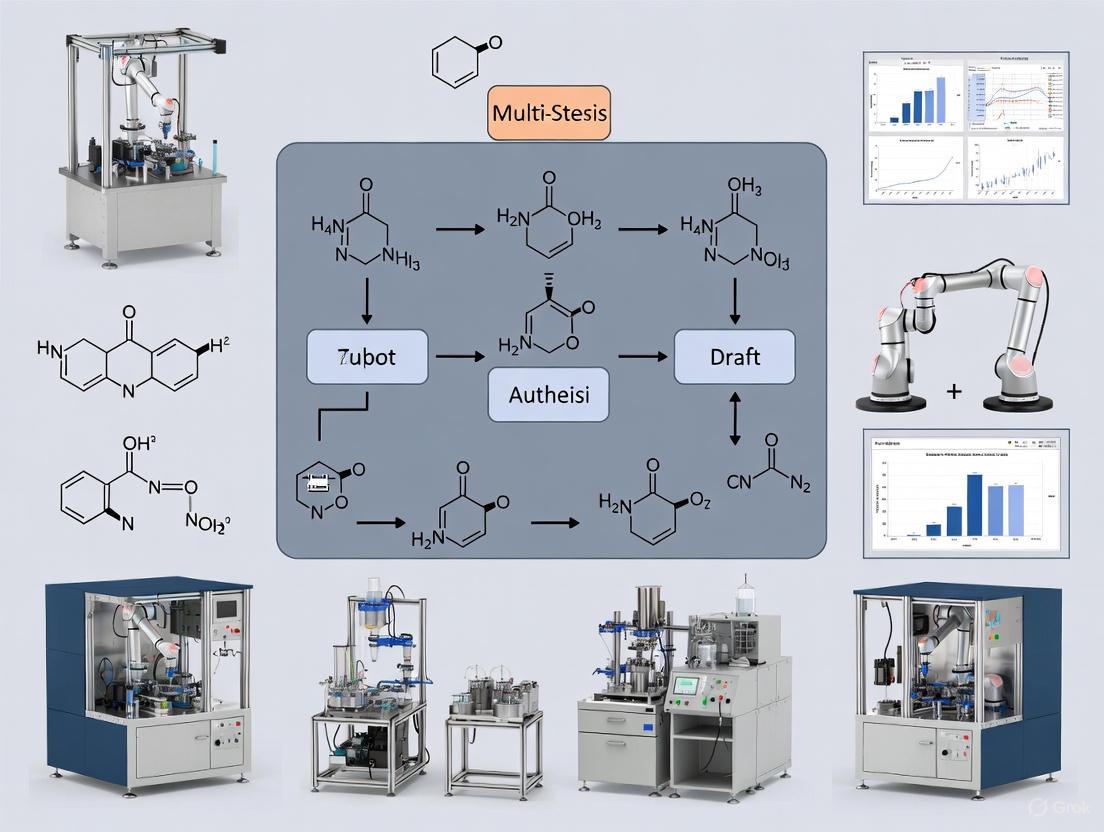

Autonomous Multi-Step Synthesis: How Robotic Platforms and AI Are Accelerating Drug Discovery and Materials Science

This article explores the transformative impact of autonomous laboratories, or self-driving labs, which integrate robotic platforms with artificial intelligence (AI) to execute multi-step chemical synthesis.

Autonomous Multi-Step Synthesis: How Robotic Platforms and AI Are Accelerating Drug Discovery and Materials Science

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of autonomous laboratories, or self-driving labs, which integrate robotic platforms with artificial intelligence (AI) to execute multi-step chemical synthesis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of these closed-loop systems that shift research from traditional trial-and-error to AI-driven, automated experimentation. The scope includes methodological insights into platform architectures, from liquid handling to mobile robots, and their application in synthesizing nanomaterials and organic molecules. It further addresses key challenges in optimization and troubleshooting, such as data quality and hardware modularity, and provides a comparative validation of the performance and efficiency of different AI algorithms. By synthesizing these facets, the article outlines how autonomous synthesis is poised to accelerate discovery in biomedicine and clinical research.

The New Paradigm: Foundations of Autonomous Labs and Closed-Loop Discovery

Autonomous laboratories, often termed self-driving labs, represent a transformative paradigm in scientific research, fundamentally accelerating the discovery and development of novel materials and molecules. These systems integrate artificial intelligence (AI), robotic experimentation, and automation technologies into a continuous, closed-loop cycle to conduct scientific experiments with minimal human intervention [1]. This shift moves research from traditional, often intuitive, trial-and-error approaches to a data-driven, iterative process where AI plans experiments, robotics execute them, and data is automatically analyzed to inform the next cycle. The core value proposition lies in dramatically compressed discovery timelines; processes that once required months of manual effort can now be condensed into high-throughput, automated workflows [1]. This transformation is particularly impactful in fields like inorganic materials synthesis [2] and organic chemistry [3], where the exploration space is vast and the experimental burden is high.

Core Architecture of an Autonomous Laboratory

The operational backbone of an autonomous laboratory is a tightly integrated, closed-loop cycle. This architecture seamlessly connects computational design with physical experimentation and learning, creating a self-optimizing system.

The Autonomous Workflow Cycle

The following diagram illustrates the continuous, closed-loop process that defines a self-driving lab:

Diagram 1: The core closed-loop workflow of an autonomous laboratory.

This workflow consists of four critical, interconnected stages:

- AI-Driven Experimental Planning: Given a target molecule or material, an AI model, trained on vast literature data and prior knowledge, generates initial synthesis schemes. This includes selecting precursors, defining intermediates for each reaction step, and proposing optimal reaction conditions [1]. In advanced systems, Large Language Models (LLMs) can perform this planning, using natural language processing to interpret scientific literature and design feasible experiments [1] [3].

- Robotic Execution: Robotic systems automatically execute the synthesis recipe. This involves precise liquid handling, solid dispensing, reaction control (e.g., temperature, stirring), and sample collection [1]. Platforms can range from modular systems with mobile robots transporting samples between fixed instruments [1] to integrated robotic arms that handle existing laboratory equipment [4].

- Automated Analysis and Characterization: The products are automatically transferred to analytical instruments. Software algorithms or machine learning models then analyze the characterization data (e.g., from XRD, UPLC-MS, NMR) for substance identification and yield estimation [1] [4].

- Data Interpretation and AI Learning: The analyzed results are fed back to the AI system. Using techniques like active learning and Bayesian optimization, the AI interprets the data and proposes improved synthetic routes or refined conditions for the next experiment, thus closing the loop [1] [2].

System Architecture and Control Layers

Implementing the autonomous workflow requires a structured control system. Drawing parallels from robot-aided rehabilitation, a effective control architecture can be conceptualized in three layers [5]:

- Deliberative Layer: This is the "brain" of the operation, where high-level planning occurs. It uses AI for long-term strategy, such as planning a multi-step synthesis campaign or optimizing a therapeutic trajectory over multiple cycles. This layer is implemented using automated planning and scheduling methodologies [5].

- Reactive Layer: This layer processes real-time data from the physical instruments and dynamically adjusts the robot's behavior during an experiment. It can respond to immediate feedback, such as adjusting assistance levels in a physical system or modifying task difficulty, ensuring stability and adaptability during execution [5].

- Physical Layer: This encompasses the direct interaction with the physical world, including both monitoring (sensors, cameras, analytical instruments that collect data on the experiment) and effectors (robotic arms, liquid handlers, and other actuators that carry out the physical tasks) [5].

Quantitative Performance of Pioneering Platforms

The efficacy of autonomous laboratories is demonstrated by several pioneering platforms that have achieved significant milestones in materials and chemical synthesis. The table below summarizes the performance metrics of key implementations.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Select Autonomous Laboratory Platforms

| Platform Name | Primary Focus | Reported Performance | Key Technologies Integrated | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-Lab | Solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders | Synthesized 41 of 58 target compounds (71% success rate) over 17 days of continuous operation. | AI-powered recipe generation, robotic solid-state synthesis, ML-based XRD phase analysis, ARROWS3 active learning. | [1] [2] |

| Modular Platform (Dai et al.) | Exploratory synthetic chemistry | Autonomously performed screening, replication, scale-up, and functional assays over multi-day campaigns. | Mobile robots, Chemspeed synthesizer, UPLC-MS, benchtop NMR, heuristic reaction planner. | [1] |

| Coscientist | Automated chemical synthesis | Successfully optimized palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. | LLM agent with web search, document retrieval, and robotic control capabilities. | [1] |

| Camera Detection System | Robotic-arm-based lab automation | Achieved digital display recognition with an error rate of 1.69%, comparable to manual reading. | Low-cost Raspberry Pi camera, fiducial (ArUco) markers, deep learning neural network, OpenCV. | [4] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Basic Autonomous Workflow for Material Synthesis

This protocol outlines the key steps for establishing an autonomous synthesis and characterization cycle, based on the operational principles of platforms like A-Lab [1] [2].

Reagents and Hardware Configuration

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Hardware for an Autonomous Materials Lab

| Item Category | Specific Examples / Requirements | Primary Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Materials | High-purity solid powders (e.g., metal oxides, carbonates, phosphates). | Raw materials for solid-state synthesis of target compounds. |

| Robotic Platform | Robotic arm (e.g., Horst600) or integrated synthesis station (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth). | Automated weighing, mixing, and sample handling. |

| High-Temperature Furnace | Programmable furnace with robotic loading/unloading capability. | Performing solid-state reactions at specified temperatures and atmospheres. |

| Characterization Instrument | X-ray Diffractometer (XRD) with an automated sample changer. | Phase identification and quantification of synthesis products. |

| Fiducial Markers | Augmented Reality University of Cordoba (ArUco) markers. | Object detection and spatial localization for robotic cameras [4]. |

| Software & AI Models | Natural-language models for recipe generation, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for XRD analysis, Active Learning algorithms (e.g., Bayesian optimization). | Experimental planning, data analysis, and iterative optimization. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Target Selection and Initialization:

- Input: Provide the target material's composition or structure, often identified from computational databases (e.g., the Materials Project) [1] [2].

- AI Planning: The AI system, trained on historical literature, generates an initial synthesis recipe, including precursor selection and mixing ratios, and a proposed reaction temperature profile.

Robotic Synthesis Execution:

- Dispensing: The robotic arm precisely weighs and dispenses the required precursor powders into a reaction vessel (e.g., a ceramic mortar or ball mill vial). Fiducial markers on lab equipment aid the robot in accurate navigation and operation [4].

- Mixing: The system performs mixing or grinding according to the planned protocol.

- Reaction: The robotic arm transfers the sample to a furnace, which is heated according to the AI-defined temperature profile.

Automated Product Characterization:

- Transfer: After the reaction, the robot moves the synthesized powder to an XRD sample holder.

- Measurement: The XRD instrument automatically collects a diffraction pattern.

- Phase Analysis: A machine learning model (e.g., a CNN) analyzes the XRD pattern in real-time to identify the crystalline phases present and estimate the yield of the target material [1].

Data Analysis and Decision Making:

- Learning: The outcome (success/failure and yield) is fed to an active learning algorithm.

- Optimization: If the synthesis fails or the yield is low, the AI uses this data to refine the synthesis parameters (e.g., temperature, precursor ratio, or even a completely new precursor set).

- Iteration: The system automatically initiates the next experiment with the updated recipe, continuing the closed-loop cycle.

The following diagram details the system architecture that enables this protocol:

Diagram 2: The layered control architecture connecting AI planning to physical hardware.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Enabling Technologies

The functionality of autonomous labs is enabled by a suite of advanced software and hardware tools.

Table 3: Key Enabling Technologies for Autonomous Laboratories

| Technology | Specific Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Recipe generation from literature, planning multi-step syntheses, operating robotic systems via natural language commands. | ChemCrow, Coscientist, ChemAgents [1] [3]. |

| Computer Vision | Robotic navigation, sample identification, and automated readout of instrument displays. | ArUco markers with OpenCV, deep learning neural networks for digit recognition [4]. |

| Active Learning & Bayesian Optimization | Intelligently selecting the most informative experiments to perform next, maximizing learning and optimization efficiency. | ARROWS3 algorithm used in A-Lab for iterative route improvement [1] [2]. |

| Mobile Manipulators | Transporting samples between different, non-integrated laboratory instruments, enabling modular automation. | TIAGo mobile manipulator operating with LAPP (Laboratory Automation Plug & Play) concept [6]. |

| Standardized Communication Protocols | Ensuring interoperability between different instruments and software from various manufacturers. | SiLA (Standardization in Lab Automation) and ROS (Robot Operating System) frameworks [6]. |

Current Constraints and Future Directions

Despite their promise, autonomous laboratories face several constraints that limit widespread deployment. Key challenges include:

- Data Dependency: AI model performance is heavily reliant on high-quality, diverse data. Data scarcity, noise, and inconsistency can hinder accurate characterization and planning [1].

- Lack of Generalization: Most systems are specialized for specific reaction types or materials. AI models struggle to transfer knowledge to new scientific domains [1].

- Hardware Rigidity: Current platforms often lack modular hardware architectures that can seamlessly accommodate the diverse requirements of different chemical tasks (e.g., solid-phase vs. liquid-phase synthesis) [1] [6].

- LLM Reliability: LLMs can occasionally generate plausible but incorrect chemical information or confident-sounding answers without indicating uncertainty, which could lead to failed experiments or safety hazards [1].

Future development will focus on overcoming these hurdles by training foundation models across different domains, developing standardized interfaces for hardware, embedding targeted human oversight, and employing advanced techniques like transfer learning to adapt models to new data-poor domains [1]. The continued integration of more advanced AI, coupled with robust and modular robotic systems, promises to further enhance the intelligence, capacity, and reliability of autonomous laboratories, solidifying their role as a cornerstone of modern scientific discovery.

Application Notes

The implementation of closed-loop systems for autonomous multi-step synthesis represents a paradigm shift in materials science and drug development. These systems integrate robotic experimentation, artificial intelligence (AI), and continuous data management to accelerate discovery and optimization processes. By creating a continuous cycle of experimentation, analysis, and decision-making, researchers can navigate complex parameter spaces with unprecedented efficiency and reproducibility.

Core Architectural Components

A robust closed-loop system for autonomous synthesis requires tight integration of several key components that work in concert to enable fully automated discovery workflows.

Robotic Synthesis Platforms: Automated platforms such as the Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer form the physical core of the system, enabling precise and reproducible handling of reagents and execution of synthetic procedures without human intervention [7]. These systems must accommodate a wide range of chemical transformations and process conditions required for multi-step synthesis.

Multi-Modal Analytical Integration: Orthogonal characterization techniques are essential for comprehensive reaction monitoring. Successful implementations combine instruments such as ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) for separation and mass analysis and benchtop nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy for structural elucidation [7]. This multi-technique approach mirrors the decision-making process of human researchers who rarely rely on single analytical methods.

Mobile Robotic Sample Transfer: Free-roaming mobile robots provide the physical connectivity between modular system components, transporting samples between synthesis platforms and analytical instruments [7]. This modular approach allows existing laboratory equipment to be integrated without extensive redesign or monopolization of instruments, making the system highly flexible and scalable.

AI-Driven Decision-Making: The intelligence of the closed-loop system resides in algorithmic decision-makers that process analytical data to determine subsequent experimental steps. Heuristic approaches designed by domain experts can evaluate results from multiple analytical techniques and provide binary pass/fail decisions for each reaction, determining which pathways to pursue in subsequent synthetic steps [7].

System Performance and Validation

Quantitative assessment of closed-loop system performance demonstrates significant acceleration of research workflows compared to traditional manual approaches.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Closed-Loop Synthesis Systems

| Performance Metric | Manual Synthesis | Closed-Loop System | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Throughput | 1-10 experiments/day | 10-100 experiments/day | 10×−100× acceleration [8] |

| Discovery Timelines | Months to years | Days to weeks | Years reduced to days [9] |

| Data Generation Volume | Limited by human capacity | Continuous, automated collection | Massive dataset generation [8] |

| Reproducibility | Batch-to-batch variation | High reproducibility | Standardized protocols [10] |

The "Rainbow" system for metal halide perovskite (MHP) nanocrystal synthesis exemplifies these performance improvements, autonomously navigating a 6-dimensional input and 3-dimensional output parameter space to optimize optical properties including photoluminescence quantum yield and emission linewidth [8]. Similarly, modular robotic workflows have demonstrated capability in supramolecular host-guest chemistry and photochemical synthesis, autonomously identifying successful reactions and checking reproducibility of screening hits before scale-up [7].

Data Management Infrastructure

Effective data management forms the foundation of successful closed-loop operation, particularly given the massive datasets generated by continuous experimentation.

Centralized Data Repository: All analytical data and experimental parameters are saved in a central database that serves as the system's memory, enabling pattern recognition and trend analysis across multiple experimental cycles [7].

Standardized Data Formats: Adoption of standardized data formats and protocols, such as ROS 2 in robotics applications, ensures interoperability and efficient data exchange between system components [11].

Real-Time Processing Architecture: Edge computing approaches allow data pre-processing closer to the source, reducing latency in control loops and enabling immediate feedback for time-sensitive processes [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Autonomous Multi-Step Synthesis Using Modular Robotic Workflow

This protocol describes the procedure for conducting autonomous multi-step synthesis using a modular system of mobile robots, automated synthesizers, and analytical instruments.

Preparation and System Configuration

Equipment Setup: Configure the synthesis module (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth), UPLC-MS system, benchtop NMR spectrometer, and mobile robots in physically separated but accessible locations. Install electric actuators on synthesizer doors to enable automated access by mobile robots [7].

Reagent Preparation: Stock the synthesizer with all required starting materials, solvents, and catalysts. Ensure adequate supplies for extended unmanned operation, considering potential scale-up steps for promising synthetic pathways.

Method Programming: Develop synthesis routines using platform-specific control software. For the Chemputer platform, implement procedures using the chemical description language (XDL) to ensure synthetic reproducibility [10].

Analytical Calibration: Calibrate all analytical instruments (UPLC-MS, NMR) using standard references. Establish pass/fail criteria for each analytical technique based on domain expertise and specific research objectives [7].

Synthesis Execution and Analysis

Initial Reaction Array: Program the synthesizer to execute the first set of reactions based on experimental design parameters. For divergent syntheses, this typically involves preparing common precursor molecules [7].

Automated Sampling: Upon reaction completion, the synthesizer takes aliquots of each reaction mixture and reformats them separately for MS and NMR analysis.

Robotic Sample Transfer: Mobile robots retrieve samples from the synthesizer and transport them to the appropriate analytical instruments. A single robot with a multipurpose gripper can perform all transfer tasks, though multiple task-specific robots increase throughput [7].

Orthogonal Analysis: Conduct UPLC-MS analysis to monitor reaction conversion and identify major products. Perform benchtop NMR spectroscopy for structural verification. Data acquisition occurs autonomously through customizable Python scripts [7].

Decision-Making and Iteration

Data Integration: Analytical results are saved in the central database and processed by the heuristic decision-maker. The algorithm evaluates data from both analytical techniques according to predefined criteria.

Pathway Selection: Reactions that meet pass criteria for both NMR and UPLC-MS analyses proceed to the next synthetic step. Failed reactions are documented but not pursued further in the autonomous workflow [7].

Scale-Up and Elaboration: Successful precursors are automatically scaled up and subjected to divergent synthesis steps, creating a library of structurally related compounds for further evaluation.

Iterative Cycling: The synthesis-analysis-decision cycle continues without human intervention until predefined objectives are met or the experimental space is sufficiently explored.

Protocol: Closed-Loop Optimization of Nanocrystal Synthesis

This protocol details the procedure for autonomous optimization of metal halide perovskite (MHP) nanocrystal optical properties using the Rainbow platform.

System Initialization

Hardware Configuration: The Rainbow platform integrates a liquid handling robot for precursor preparation and multi-step synthesis, a characterization robot for spectroscopic measurements, a robotic plate feeder for labware replenishment, and a robotic arm for sample transfer [8].

Parameter Space Definition: Define the 6-dimensional input parameter space including ligand structures, precursor concentrations, reaction times, and temperature parameters. Establish output objectives targeting photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), emission linewidth (FWHM), and peak emission energy [8].

AI Agent Configuration: Implement machine learning algorithms for experimental planning. Bayesian optimization approaches are particularly effective for navigating high-dimensional parameter spaces with multiple objectives [8].

Autonomous Optimization Cycle

Parallelized Synthesis: The liquid handling robot prepares NC precursors and conducts parallelized, miniaturized batch synthesis reactions using multiple reactor stations.

Real-Time Characterization: Automated sampling transfers reaction products to spectroscopic instrumentation for continuous measurement of UV-Vis absorption and emission properties.

Performance Evaluation: The AI agent calculates performance metrics based on target objectives, comparing current results to previous experiments and established benchmarks.

Experimental Planning: Based on all accumulated data, the AI agent selects the next set of experimental conditions, balancing exploration of unknown regions of parameter space with exploitation of promising areas [8].

Continuous Operation: The system operates autonomously until reaching target performance thresholds or completing a predefined number of experimental cycles.

Knowledge Extraction and Validation

Pareto-Front Mapping: The system identifies Pareto-optimal formulations that represent the best possible trade-offs between multiple competing objectives, such as PLQY versus FWHM at target emission energies [8].

Retrosynthesis Analysis: Data mining of successful synthetic pathways enables derivation of structure-property relationships and development of retrosynthetic principles for specific material properties.

Scale-Up Validation: Transfer optimal synthesis conditions identified in miniaturized batch reactors to larger-scale production to verify scalability and practical applicability.

Visualization

Core Architecture of Closed-Loop System

Autonomous Synthesis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Autonomous Synthesis Platforms

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Acid/Base Ligands | Control nanocrystal growth and stabilization via acid-base equilibrium reactions; tune optical properties [8]. | MHP NC surface ligation |

| Metal Halide Precursors | Provide metal and halide components for perovskite crystal formation; determine composition and bandgap [8]. | CsPbX₃ (X=Cl, Br, I) NC synthesis |

| Post-Synthesis Halide Exchange Reagents | Fine-tune bandgap through anion exchange; precisely control optical properties in the UV-visible spectral region [8]. | MHP NC bandgap engineering |

| Molecular Machine Building Blocks | Structurally diverse components for complex molecular assembly; enable construction of architectures with specific functions [10]. | [2]Rotaxane synthesis |

| Supramolecular Host-Guest Components | Form self-assembled structures with specific binding properties; enable creation of complex molecular recognition systems [7]. | Host-guest chemistry studies |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography Media | Purify reaction products based on molecular size; separate desired products from starting materials and byproducts [10]. | Purification of molecular machines |

| Silica Gel Chromatography Media | Standard stationary phase for purification; separate compounds based on polarity differences [10]. | Routine reaction purification |

The pursuit of new functional molecules, whether for drug discovery or advanced materials, requires navigating vast chemical spaces—theoretical spaces encompassing all possible molecules and compounds. These spaces are inherently high-dimensional, meaning each molecular descriptor (e.g., molecular weight, lipophilicity, presence of functional groups) constitutes a separate dimension. For a researcher, this high-dimensionality presents a fundamental challenge: the combinatorial explosion of possible experiments makes exhaustive exploration through traditional, manual "one-parameter-at-a-time" methods entirely infeasible [12] [13].

This inefficiency of manual experimentation is a critical bottleneck. In fields like metal halide perovskite (MHP) nanocrystal synthesis, this complex synthesis space limits the full exploitation of the material's extraordinary tunable optical properties [12]. Similarly, in drug discovery, virtual screening methods generate high-dimensional mathematical models that are difficult to interpret and analyze without specialized computational resources [13]. Autonomous multi-step synthesis using robotic platforms emerges as a powerful solution to this challenge, integrating automation, real-time characterization, and intelligent decision-making to navigate this complexity efficiently and reproducibly.

Autonomous Robotic Platforms as a Solution

Autonomous laboratories represent a paradigm shift, moving beyond simple automation to systems where agents, algorithms, or artificial intelligence (AI) not only execute experiments but also record and interpret analytical data to make subsequent decisions [14]. This closed-loop functionality is key to tackling high-dimensional spaces. These self-driving labs (SDLs) can accelerate the discovery of novel materials and synthesis strategies by a factor of 10 to 100 times compared to the status quo in traditional experimental labs [12].

Two prominent architectural philosophies have emerged for these platforms:

- Modular Mobile Robot Systems: These systems use free-roaming mobile robots to physically connect otherwise independent laboratory instruments, such as an automated synthesizer, a liquid chromatography–mass spectrometer (UPLC-MS), and a benchtop nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer [14]. This approach leverages existing laboratory equipment without requiring extensive, bespoke redesign, allowing robots and human researchers to share infrastructure.

- Integrated Multi-Robot Platforms: Systems like the "Rainbow" platform for MHP nanocrystals are designed as integrated units, featuring multiple dedicated robots for tasks like liquid handling, sample transfer, and characterization [12]. This design is optimized for intensified, high-throughput exploration of a specific class of materials.

The core of these platforms' effectiveness lies in their AI-driven decision-making. An AI agent is provided with a human-defined goal and, by emulating existing experimental data, iteratively proposes the next set of experiments, effectively balancing the exploration of the unknown chemical space with the exploitation of promising leads [12].

Application Notes & Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing autonomous platforms to navigate complex chemical spaces.

Protocol 1: Modular Mobile Robotics for Exploratory Organic Synthesis

This protocol outlines the procedure for using a modular system with mobile robots to perform exploratory synthesis, as demonstrated for the structural diversification of ureas and thioureas, and supramolecular chemistry [14].

- Primary Objective: To autonomously synthesize and characterize a library of organic molecules, identifying successful reactions for further elaboration without human intervention.

- Experimental Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the closed-loop, decision-making workflow.

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Synthesis Module Setup: Load the automated synthesis platform (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth) with the required starting materials and solvents.

- Parallel Synthesis Execution: The platform autonomously performs the combinatorial condensation reactions according to a pre-defined set of starting conditions.

- Sample Reformating and Aliquoting: Upon reaction completion, the synthesizer takes an aliquot of each reaction mixture and reformats it into standard vials for UPLC-MS and NMR analysis.

- Mobile Robot Transport: A mobile robot retrieves the sample vials and transports them across the laboratory to the UPLC-MS and benchtop NMR spectrometers.

- Orthogonal Analysis: The analytical instruments autonomously run their characterization methods. Python scripts control data acquisition, and the results are saved to a central database.

- Heuristic Decision-Making: A decision-maker algorithm processes the orthogonal UPLC-MS and

H NMRdata. For each reaction, it provides a binary "pass" or "fail" grade based on experiment-specific criteria defined by a domain expert. - Data Fusion and Action: The binary results from both analytical techniques are combined. In the demonstrated workflow, a reaction must pass both analyses to proceed.

- Closed-Loop Execution: Reactions that pass are automatically selected for scale-up or further elaboration in a subsequent synthetic step. Failed reactions are not pursued.

Protocol 2: AI-Driven Optimization of Nanocrystal Synthesis

This protocol details the operation of an integrated multi-robot platform, like the "Rainbow" system, for autonomously optimizing the optical properties of metal halide perovskite (MHP) nanocrystals (NCs) [12].

- Primary Objective: To efficiently navigate a high-dimensional, mixed-variable parameter space and identify Pareto-optimal synthesis conditions for target photoluminescence properties.

- Experimental Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the continuous feedback loop of the AI-driven optimization process.

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Goal Definition: The user defines the optimization objective, which is typically a multi-objective function combining target peak emission energy (

E_P), maximized photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), and minimized emission linewidth (FWHM). - AI Experimental Proposal: Based on initial data or a prior, the AI agent (e.g., using a Bayesian Optimization algorithm) selects a set of promising experimental conditions from the 6-dimensional input space (e.g., involving ligand structure, precursor concentrations, halide exchange parameters).

- Robotic Synthesis and Characterization: A liquid-handling robot prepares NC precursors and executes a multi-step, room-temperature synthesis in parallelized, miniaturized batch reactors. A characterization robot then transfers samples to a benchtop spectrometer to acquire UV-Vis absorption and photoluminescence emission spectra.

- Data Processing: The spectral data is automatically processed to extract the key performance metrics: PLQY, FWHM, and

E_P. - AI Model Update: The new experimental results (both successful and failed) are added to the dataset, and the AI model is updated to refine its understanding of the synthesis landscape.

- Closed-Loop Iteration: The updated AI agent proposes the next batch of experiments, balancing exploration of uncertain regions of the parameter space with exploitation of known high-performance areas.

- Completion and Knowledge Extraction: The loop continues until a target is reached or a user-defined stopping point is met. The system then outputs the Pareto-optimal formulations and provides retrosynthesis knowledge that can be directly transferred to scaled-up production.

- Goal Definition: The user defines the optimization objective, which is typically a multi-objective function combining target peak emission energy (

Data Presentation & Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Autonomous Platforms

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Featured Autonomous Robotic Platforms

| Feature | Modular Mobile Robot System [14] | Integrated Multi-Robot Platform (Rainbow) [12] |

|---|---|---|

| System Architecture | Distributed, instruments linked by mobile robots | Integrated, dedicated robots for specific tasks |

| Primary Application | Exploratory organic & supramolecular synthesis | Optimization of nanocrystal optical properties |

| Key Analytical Techniques | UPLC-MS, Benchtop NMR | UV-Vis, Photoluminescence spectroscopy |

| Decision-Making Engine | Heuristic, rule-based algorithm | AI-driven (e.g., Bayesian Optimization) |

| Handled Data Dimensions | Multimodal, orthogonal data fusion | 6-dimensional input, 3-dimensional output space |

| Throughput Advantage | Enables sharing of lab equipment with humans | Highly parallelized, intensified research framework |

| Reported Acceleration | Mimics human decision-making protocols | 10× to 100× acceleration vs. manual methods |

Key Reagent Solutions for Featured Experiments

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in the Protocol | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Alkyne Amines | Building blocks for combinatorial library synthesis (Protocol 1) [14] | e.g., Compounds 1-3 for urea/thiourea formation |

| Isothiocyanates / Isocyanates | Electrophilic coupling partners for diversification [14] | e.g., Compounds 4 and 5 |

| Organic Acid/Base Ligands | Control growth & optical properties of nanocrystals [12] | Critical discrete variable in MHP NC optimization |

| Cesium Lead Halide Precursors | Starting materials for metal halide perovskite synthesis [12] | e.g., CsPbBr3 for post-synthesis halide exchange |

| Morgan Fingerprints | Molecular descriptor for chemical space analysis [15] | 1024-bit, radius 2 used for dimensionality reduction |

| PCA (Principal Component Analysis) | Statistical method for prioritizing molecular descriptors [13] | Reduces dimensionality, eliminates redundant descriptors |

Essential Methodologies for Data Handling

A critical component of managing high-dimensional chemical spaces is the use of dimensionality reduction (DR) techniques, which transform high-dimensional descriptor data into human-interpretable 2D or 3D maps, a process known as chemography [15].

- Technique Selection: Common DR techniques include:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): A linear method that finds the axes of greatest variance in the data. It is widely used to reduce the number of dimensions by selecting the most influential molecular descriptors, potentially reducing original dimensions to one-twelfth of their size [13].

- t-SNE and UMAP: Non-linear methods that are particularly effective at preserving local neighborhood structures within the data in the low-dimensional embedding, often providing superior visual cluster separation [15].

- Protocol for Neighborhood Preservation Analysis:

- Descriptor Calculation: Generate high-dimensional molecular descriptors (e.g., Morgan fingerprints, MACCS keys) for the entire compound set.

- Apply Dimensionality Reduction: Project the data into 2D space using PCA, t-SNE, UMAP, or other algorithms.

- Define Neighbors: In both the original high-dimensional space and the reduced latent space, define the k-nearest neighbors for each compound using an appropriate distance metric (e.g., Euclidean distance, Tanimoto similarity).

- Calculate Preservation Metrics: Quantify the quality of the DR using metrics like the percentage of preserved nearest neighbors (

PNNk), which calculates the average number of shared k-nearest neighbors between the original and latent spaces [15]. Other metrics like trustworthiness and continuity further assess the embedding's quality. - Hyperparameter Optimization: Perform a grid-based search of the DR algorithm's hyperparameters (e.g., perplexity for t-SNE, number of neighbors for UMAP) to maximize the neighborhood preservation metrics.

The integration of Large Language Models (LLMs), Bayesian Optimization, and Robotic Arms is creating a paradigm shift in autonomous research laboratories. These technologies collectively enable self-driving labs (SDLs) that can autonomously design, execute, and optimize complex multi-step synthesis processes with minimal human intervention. This technological triad functions as an interconnected system where LLMs provide high-level reasoning and protocol generation, Bayesian Optimization enables efficient experimental space exploration, and robotic arms deliver precise physical execution capabilities.

The significance of this integration lies in its ability to address fundamental challenges in experimental science: overcoming human cognitive limitations in high-dimensional parameter spaces, dramatically accelerating discovery timelines, and enhancing reproducibility. These systems are particularly transformative for fields requiring extensive experimental iteration, including drug development, materials science, and catalyst research, where they enable systematic exploration of complex synthesis landscapes that were previously intractable through manual approaches.

Technology-Specific Roles and Implementation

Large Language Models (LLMs) in Autonomous Experimentation

Large Language Models serve as the cognitive center of autonomous research platforms, providing natural language understanding, reasoning capabilities, and procedural knowledge. In advanced implementations, LLMs are deployed within specialized multi-agent architectures where different LLM instances assume distinct roles mirroring human research teams:

- Biologist Agent: Specializes in experimental design and protocol synthesis using retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to incorporate current scientific literature. This agent converts research objectives into structured experimental procedures while accounting for laboratory constraints [16].

- Technician Agent: Translates natural language protocols into executable robotic commands through pseudo-code generation. This agent bridges the semantic gap between experimental intent and physical implementation [16].

- Inspector Agent: Utilizes vision-language models (VLMs) for real-time quality control, anomaly detection, and procedural validation during experiment execution [16].

The implementation of LLMs in systems like BioMARS demonstrates the hierarchical specialization essential for handling complex research workflows. In this architecture, the Biologist Agent first generates biologically valid protocols, the Technician Agent then decomposes these into precise robotic instructions, and the Inspector Agent continuously monitors execution fidelity through multimodal perception [16]. This division of labor enables robust handling of the entire experimental lifecycle from design to execution.

Bayesian Optimization for Experimental Design

Bayesian Optimization provides the mathematical framework for efficient exploration of high-dimensional experimental spaces. This machine learning approach employs probabilistic surrogate models to balance exploration of unknown regions with exploitation of promising areas, dramatically reducing the number of experiments required to identify optimal conditions.

In advanced materials research, Bayesian Optimization has demonstrated particular efficacy in navigating mixed-variable parameter spaces containing both continuous and discrete parameters. The Rainbow SDL exemplifies this application in optimizing metal halide perovskite nanocrystals, where the algorithm simultaneously manipulates ligand structures, precursor concentrations, and reaction conditions to maximize target optical properties [8].

The implementation typically follows an iterative cycle:

- Initial experimental design based on prior knowledge or space-filling sampling

- Surrogate model training on accumulated experimental data

- Acquisition function calculation to identify the most promising next experiment

- Automated execution of selected experiment

- Model updating with new results

- Repeat until convergence to optimal conditions or exhaustion of experimental budget

This approach has achieved 10×-100× acceleration in materials discovery compared to traditional one-variable-at-a-time experimentation, making it particularly valuable for optimizing complex, nonlinear synthesis processes with multiple interacting parameters [8].

Robotic Arms for Physical Automation

Robotic arms provide the physical embodiment necessary to transform computational designs into tangible experiments. Modern implementations range from single-arm systems for straightforward liquid handling to complex dual-arm platforms that mimic human dexterity for intricate manipulation tasks.

In biological applications, systems like BioMARS employ dual-arm robotic platforms that enable sophisticated coordination for cell culture procedures including passaging, medium exchange, and viability assessment [16]. These systems achieve performance matching or exceeding manual techniques in consistency, viability, and morphological integrity while operating continuously without fatigue.

Alternative automation architectures include roll-to-roll systems that eliminate the need for robotic arms in specific applications. The CatBot platform for electrocatalyst development exemplifies this approach, using continuous substrate transfer through sequential processing stations for cleaning, synthesis, and electrochemical testing [17]. This design enables fabrication and testing of up to 100 catalyst-coated samples daily without manual intervention.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Robotic Automation Architectures

| Architecture | Key Features | Throughput | Application Examples | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Arm Systems | Basic liquid handling, simpler programming | Moderate | Routine liquid transfer, sample preparation | Limited dexterity for complex tasks |

| Dual-Arm Platforms | Human-like coordination, complex manipulation | High | Cell culture, intricate synthesis procedures | Higher cost, complex programming |

| Roll-to-Roll Systems | Continuous processing, minimal moving parts | Very High | Catalyst coating, film deposition | Limited to substrate-based processes |

| Multi-Robot Cells | Parallel processing, specialized stations | Highest | Perovskite nanocrystal synthesis [8] | Highest complexity and cost |

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Autonomous Cell Culture and Maintenance

System: BioMARS (Biological Multi-Agent Robotic System) [16]

Objective: Fully automated passage and maintenance of mammalian cell lines, achieving viability and consistency comparable to manual techniques.

Experimental Workflow:

Protocol Generation Phase:

- The Biologist Agent processes natural language queries (e.g., "Passage HeLa cells at 80% confluency") using retrieval-augmented generation from scientific literature and internal databases [16].

- Generated protocols undergo validation through Knowledge Checker and Workflow Checker modules to ensure biological accuracy and logical coherence.

- Output includes detailed step-by-step procedures with specific reagent volumes, environmental conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂), and timing parameters.

Code Translation Phase:

- The Technician Agent converts natural language protocols into executable robotic pseudo-code using a CodeGenerator module.

- A CodeChecker module validates instructions against laboratory constraints (container availability, pipette volume limits) [16].

- Output includes primitives such as

aspirate_medium,wash_with_PBS,add_trypsin,incubate,neutralize,seed_new_flask.

Execution Phase:

- Dual robotic arms coordinate to execute the translated protocol with one arm handling container positioning and the other performing liquid transfer operations.

- The Inspector Agent employs real-time vision monitoring to confirm procedural steps including confluency assessment, detachment verification, and morphological inspection [16].

- Anomalies such as misaligned containers or pipetting errors trigger automatic pausing and corrective protocols.

Data Recording and Optimization:

- All experimental parameters and outcomes are logged with timestamps for reproducibility analysis.

- Cell viability and confluency metrics are recorded to inform future protocol adjustments.

Diagram 1: BioMARS Cell Culture Workflow

Protocol 2: Autonomous Optimization of Metal Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals

System: Rainbow Multi-Robot Self-Driving Laboratory [8]

Objective: Autonomous navigation of a 6-dimensional parameter space to optimize photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and emission linewidth at target emission energies.

Experimental Workflow:

Objective Definition Phase:

- Researchers specify target optical properties through a web interface, typically defining a multi-objective function combining PLQY, FWHM (full-width-at-half-maximum), and target peak emission energy.

- The AI agent initializes with prior knowledge or begins with space-filling experimental design.

Parallel Experiment Planning Phase:

- Bayesian Optimization algorithm selects the most informative next set of experiments based on current belief of the synthesis landscape.

- The system generates specific formulations varying ligand structures, precursor ratios, and reaction conditions.

- Liquid handling robot prepares precursor solutions in miniaturized batch reactors according to generated formulations [8].

Synthesis and Characterization Phase:

- Robotic systems transfer reaction vessels through temperature-controlled zones with precise timing.

- Characterization robot performs automated UV-Vis absorption and photoluminescence spectroscopy on synthesized nanocrystals.

- Optical properties (PLQY, FWHM, peak emission) are automatically extracted and quantified.

Learning and Iteration Phase:

- New experimental results update the Bayesian Optimization surrogate model.

- The acquisition function identifies the most promising region for subsequent experimentation, balancing exploration of uncertain regions with exploitation of promising formulations.

- Cycle continues until Pareto-optimal formulations are identified or experimental budget is exhausted [8].

Table 2: Key Optimization Parameters in Perovskite Nanocrystal Synthesis

| Parameter Category | Specific Variables | Optimization Range | Impact on Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Structure | Organic acid chain length, binding group | 6 different organic acids | Crystal growth kinetics, surface passivation |

| Precursor Chemistry | Cesium concentration, Halide ratios (Br/Cl/I) | 0.05-0.2M Cs, various Br:I ratios | Emission energy, phase purity |

| Reaction Conditions | Temperature, Reaction time, Stirring rate | 25-100°C, 1-60 minutes | NC size, size distribution, defect density |

| Post-Synthesis Processing | Purification methods, Ligand exchange | Various solvent systems | Quantum yield, colloidal stability |

Diagram 2: Rainbow SDL Optimization Workflow

Protocol 3: High-Throughput Electrocatalyst Synthesis and Testing

System: CatBot Roll-to-Roll Automation Platform [17]

Objective: Fully automated synthesis and electrochemical characterization of up to 100 catalyst variants daily under industrially relevant conditions.

Experimental Workflow:

Substrate Preparation Phase:

- Continuous substrate (e.g., Ni wire) is fed from spool through sequential cleaning stations.

- Acid cleaning station (3M HCl) removes surface oxides and contaminants.

- Rinse station eliminates residual acid using deionized water [17].

Electrodeposition Phase:

- Cleaned substrate enters synthesis station containing metal salt electrolyte.

- Custom liquid distribution system with 7 syringe pumps enables precise multi-element catalyst deposition.

- Potentiostat applies programmed potential/current sequences to drive electrodeposition.

- System accommodates temperatures up to 100°C in highly alkaline (>30 wt% KOH) or acidic (3M HCl) media [17].

Electrochemical Testing Phase:

- Coated substrate transfers directly to testing station for performance evaluation.

- Three-electrode configuration enables accurate measurement of catalyst activity for target reactions (HER, OER, CO2RR).

- Automated system records polarization curves, impedance spectra, and stability metrics.

Sample Management Phase:

- Tested catalyst samples are collected on take-up drum for potential post-mortem characterization.

- System recycles to initial state for next experimental segment.

- All synthesis parameters and performance data are automatically correlated and stored.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in Autonomous Synthesis Platforms

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialized Cell Culture Media | Support cell growth and maintenance | Mammalian cell culture (HeLa, HUVECs) [16] | Serum-free formulations, defined components, temperature stability |

| Ligand Libraries | Control nanocrystal growth and surface passivation | Perovskite NC optimization [8] | Variable alkyl chain lengths, binding groups, purity >95% |

| Metal Salt Precursors | Source of catalytic or structural metals | Electrocatalyst electrodeposition [17] | High purity (>99.9%), solubility in deposition solvents |

| Electrolyte Formulations | Enable electrochemical synthesis and testing | Catalyst performance evaluation [17] | Acidic/alkaline stability, temperature resistance, oxygen-free |

| Functionalized Substrates | Support material for catalyst deposition | Roll-to-roll catalyst synthesis [17] | Controlled surface chemistry, electrical conductivity, mechanical stability |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 4: Comparative Performance Metrics of Autonomous Research Platforms

| Performance Metric | Manual Research | BioMARS (Biology) [16] | Rainbow (Materials) [8] | CatBot (Catalysis) [17] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Throughput | 1-10 experiments/day | Comparable to skilled technician | 10-100× acceleration vs. manual | Up to 100 catalysts/day |

| Parameter Space Dimensionality | Typically 2-3 variables | 5+ simultaneous parameters | 6-dimensional optimization | 4+ continuous variables |

| Reproducibility (Variance) | 15-30% inter-operator | <5% batch-to-batch variance | <10% property deviation | 4-13 mV overpotential uncertainty |

| Optimization Efficiency | Sequential one-variable | Multi-parameter parallel optimization | Identifies Pareto-optimal formulations in <50 cycles | Full activity-stability mapping |

| Operational Duration | 8-hour shifts | 24-hour continuous operation | Continuous until objective achieved | 24-hour continuous operation |

Inside the Self-Driving Lab: Architectures, Workflows, and Real-World Applications

Multi-robot systems (MRS) represent a paradigm shift in automated laboratories, enabling collaborative task execution that surpasses the capabilities of single-robot units [18]. In the context of autonomous multi-step synthesis, these systems provide the foundational infrastructure for parallel experimentation, distributed sensing, and coordinated material handling. The integration of MRS with modular hardware architecture creates a scalable framework that accelerates discovery cycles in pharmaceutical development and materials science.

The significance of MRS lies in their inherent robustness through redundancy, where the failure of a single unit does not compromise entire experimental campaigns [19] [18]. Furthermore, these systems enable specialized role allocation, where different robots can be optimized for specific tasks such as synthesis, sampling, analysis, or reagent replenishment. This specialization, combined with coordination, mirrors the sophisticated workflows of human research teams while operating with machine precision and endurance.

Architectural Framework and Core Components

Multi-Robot System Architectures

Multi-robot systems employ various control architectures, each with distinct implications for autonomous synthesis applications [19]:

- Centralized Control: A single controller makes decisions and issues commands to all robots. While this provides global coordination, it creates a single point of failure and limited scalability.

- Decentralized Control: Decision-making is distributed among the robots, enabling local autonomy and adaptability but requiring more complex coordination mechanisms.

- Hybrid Approaches: These combine elements of both centralized and decentralized control, striking a balance between global coordination and local flexibility through hierarchical structures.

For synthetic chemistry applications, a hybrid approach often proves most effective, with centralized oversight of experimental objectives and decentralized execution of physical operations.

Modular Hardware Design Principles

Modular hardware architecture implements electronic systems as reusable, interchangeable blocks or modules, each with functional independence and well-defined interfaces [20]. This approach is characterized by several key advantages for research environments:

- Shorter time-to-market cycles for new experimental capabilities

- Shared platform strategy across multiple product families or experimental setups

- Specialization of hardware teams working in parallel on different modules

- Resilience to supply chain volatility through swappable modules

- Hardware-software separation allowing firmware reuse across configurations [20]

A well-structured modular system for robotic synthesis typically implements these architectural layers:

- Core processing module containing SoC, FPGA, or MCU with processing power and memory

- Interface layer with I/O expansion, ADCs, DACs, USB, Ethernet, CAN, PCIe, or LVDS

- Power management module with swappable power supplies, PMICs, or battery management systems

- Application-specific daughterboards for sensors, display drivers, RF modules, or motor drivers

- Mechanical enclosures with standardized dimensions accommodating various combinations [20]

Communication Protocols for Coordinated Operations

Protocol Classification and Characteristics

Effective communication is the cornerstone of functional multi-robot systems. Protocols can be categorized by their physical implementation and performance characteristics [21]:

Wired Communication Protocols

- EtherNet/IP: Built on standard TCP/IP, using existing network infrastructure; supports both implicit (time-sensitive I/O) and explicit messaging (configuration, monitoring) [22] [23].

- PROFINET: Designed for deterministic, high-speed data transfer with sub-millisecond cycle times; ideal for motion-heavy environments [23].

- EtherCAT: Ethernet-based protocol providing real-time communication; can control up to 65,535 nodes [22].

- CAN (Controller Area Network): Efficient data exchange between multiple microcontrollers without a host computer; commonly used in automotive and industrial robotics [21].

Wireless Communication Protocols

- Wi-Fi: Enables remote operation and real-time data transfer for autonomous robots [21].

- Zigbee: Low-power, mesh-network protocol used in swarm robotics and home automation systems [21].

- LoRa (Long Range): Designed for low-power, long-range communication, suitable for environmental monitoring robots [21].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Robotic Communication Protocols

| Protocol | Data Rate | Range | Topology | Use Case in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EtherNet/IP | 10 Mbps - 1 Gbps+ | Up to 100m per segment | Star | Integration of synthesis modules with enterprise network |

| PROFINET | 100 Mbps - 1 Gbps | Up to 100m | Star, Ring, Line | Precision motion control in liquid handling |

| EtherCAT | 100 Mbps | Up to 1000m (copper) | Line, Star, Tree | Synchronization of multiple analysis instruments |

| CAN | 20 Kbps - 1 Mbps | Up to 1200m | Bus | Intra-module sensor networks |

| Wi-Fi | 54 Mbps - 1 Gbps+ | Up to 100m | Star | Mobile robot coordination |

| Zigbee | 250 Kbps | 10-100m | Mesh | Environmental monitoring sensors |

| Modbus TCP | 10/100 Mbps | Network dependent | Star | Basic instrument control (heating, stirring) |

Protocol Selection Framework

Selecting the appropriate communication protocol depends on several application-specific factors [21] [23]:

- Data Transfer Speed: Real-time applications such as autonomous synthesis require low-latency, high-speed communication.

- Wired vs. Wireless: Wired protocols provide stable and secure connections, while wireless protocols offer greater flexibility for mobile robots.

- Security Requirements: Protocols should include encryption and authentication mechanisms, particularly for IP-sensitive research.

- Scalability: The protocol should support seamless communication among numerous devices without significant data congestion.

- Compatibility: The selected protocol must integrate with existing laboratory equipment and control systems.

For pharmaceutical research environments with existing PLC infrastructure, the native protocol of the installed PLC platform (EtherNet/IP for Rockwell Automation or PROFINET for Siemens) often provides the most straightforward integration path [23].

Experimental Protocols for Autonomous Multi-Step Synthesis

Workflow Architecture for Chemical Synthesis

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for autonomous multi-step synthesis using a multi-robot platform:

This workflow implements a closed-loop experimentation cycle where analytical results directly inform subsequent synthetic steps without human intervention, dramatically accelerating the design-make-test-analyze cycle [7].

Platform Integration and Robot Coordination

The modular laboratory architecture enables flexible integration of specialized instruments through mobile robot coordination:

This distributed architecture allows instruments to be shared between automated workflows and human researchers, maximizing utilization of expensive analytical equipment [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Autonomous Perovskite Nanocrystal Optimization

Objective: Autonomous optimization of metal halide perovskite (MHP) nanocrystal optical properties including photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and emission linewidth at targeted emission energies [8].

Platform Configuration:

- Synthesis Module: Parallelized, miniaturized batch reactors for room-temperature NC synthesis

- Robotic Handling: Liquid handling robot for precursor preparation and multi-step NC synthesis

- Analysis Module: Characterization robot for UV-Vis absorption and emission spectra

- Feeding System: Robotic plate feeder for labware replenishment

- AI Integration: Machine learning-driven decision-making for closed-loop experimentation [8]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Precursor Preparation:

- Liquid handling robot prepares precursor solutions according to initial experimental design or AI-generated parameters

- Systematic variation of ligand structures and precursor conditions in 6-dimensional parameter space

Nanocrystal Synthesis:

- Parallel synthesis in miniaturized batch reactors with precise temperature control

- Robotic sampling at predetermined time points for growth kinetics analysis

Real-Time Characterization:

- Automated transfer of reaction aliquots to spectroscopic analysis

- Measurement of photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), emission linewidth (FWHM), and peak emission energy

- Continuous spectroscopic feedback for reaction monitoring

Data Analysis and Decision Making:

- Machine learning algorithm processes analytical data to evaluate performance against objectives

- Bayesian optimization identifies promising regions of parameter space for subsequent experiments

- Selection of next experimental conditions balancing exploration and exploitation

Iterative Optimization:

- Closed-loop experimentation continues until target optical properties are achieved

- Pareto-optimal front identification for multiple competing objectives

- Elucidation of structure-property relationships through systematic exploration

Validation and Scale-Up:

- Automated reproduction of optimal formulations to verify reproducibility

- Scalable synthesis conditions transferred to larger production formats [8]

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Nanocrystal Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Halide Salts (e.g., CsPbBr₃) | Primary nanocrystal precursors | Metal halide perovskite NC synthesis [8] |

| Organic Acid/Base Ligands | Surface stabilization & property tuning | Control of NC growth kinetics & optical properties [8] |

| Coordinating Solvents | Reaction medium & surface ligation | Solubilization of precursors & stabilization of NCs [8] |

| Halide Exchange Reagents | Post-synthesis bandgap tuning | Fine-tuning emission energy across UV-vis spectrum [8] |

| Stabilization Additives | Enhanced colloidal stability | Improved shelf-life & processability of NC formulations [8] |

Implementation Considerations and Future Directions

Engineering Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

Implementing modular multi-robot systems for autonomous synthesis presents several engineering challenges:

- Signal Integrity: High-speed interfaces (USB 3.1, HDMI, PCIe) require careful impedance matching, simulation, and shielding when using modular connectors [20].

- Power Management: Swappable modules can introduce voltage mismatches, necessitating well-designed PMIC and hot-swap protection circuits [20].

- Thermal Management: Modular enclosures may constrain airflow, requiring optimized heat sinks and thermal simulation [20].

- Firmware Abstraction: Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL) development is essential to isolate firmware logic from hardware dependencies [20].

Emerging Trends and Future Capabilities

The field of autonomous multi-robot synthesis platforms is rapidly evolving with several promising directions:

- Edge Computing Integration: Reducing latency by processing data closer to the source [21]

- AI-Driven Protocol Optimization: Enhancing efficiency using machine learning algorithms [21]

- 5G-Powered Robotics: Enabling ultra-fast and reliable robot communication in distributed laboratory environments [21]

- Blockchain for Secure Communication: Improving data integrity and security in robotic networks [21]

- Hybrid Communication Models: Combining wired and wireless protocols for seamless connectivity [21]

These advancements will further enhance the capabilities of autonomous research platforms, accelerating the discovery and development of novel materials and pharmaceutical compounds through highly parallelized, intelligent experimentation.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and advanced analytics has given rise to autonomous laboratories, fundamentally transforming the research and development landscape for chemical synthesis and drug development. These end-to-end workflows encapsulate the entire experimental cycle: from the initial AI-driven design of a target molecule to the automated physical synthesis, real-time characterization, and data-driven decision-making for subsequent iterations. This closed-loop paradigm minimizes human intervention, eliminates subjective decision points, and dramatically accelerates the exploration of novel chemical spaces. By turning processes that once took months of manual trial and error into routine, high-throughput workflows, autonomous labs are poised to accelerate discovery in pharmaceuticals and materials science [1].

At the core of these platforms is a continuous cycle. It begins with an AI model that generates synthetic routes and reaction conditions for a given target. Robotic systems then execute these recipes, handling tasks from reagent dispensing to reaction control. The resulting products are characterized using integrated analytical instruments, and the data is fed back to the AI. This AI analyzes the outcomes, learns from the results, and proposes improved experiments, creating a self-optimizing system [1] [24]. This approach is particularly powerful for multi-step synthesis and exploratory chemistry, where the goal may not simply be to maximize the yield of a known compound, but to navigate complex reaction landscapes and identify new functional molecules or supramolecular assemblies [14].

Several pioneering platforms exemplify the implementation of end-to-end autonomous workflows. The "Chemputer" standardizes and autonomously executes complex syntheses, such as the multi-step synthesis of [2]rotaxanes, by using a chemical description language (XDL) and integrating online feedback from NMR and liquid chromatography. This automation of time-consuming procedures enhances reproducibility and efficiency, averaging 800 base steps over 60 hours with minimal human intervention [10].

Another system, the "AI-driven robotic chemist" (Synbot), features a distinct three-layer architecture: an AI software layer for planning and optimization, a robot software layer for translating recipes into commands, and a robot layer for physical execution. Synbot has demonstrated the ability to autonomously determine synthetic recipes for organic compounds, achieving conversion rates that outperform existing references through iterative refinement using feedback from the experimental robot [24].

A modular approach, leveraging mobile robots, offers a highly flexible alternative. In one demonstrated workflow, free-roaming mobile robots transport samples between a Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer, a UPLC–MS, and a benchtop NMR spectrometer. This setup allows robots to share existing laboratory equipment with human researchers without monopolizing it or requiring extensive redesign. A key feature of this platform is its heuristic decision-maker, which processes orthogonal analytical data (NMR and MS) to autonomously select successful reactions for further study, mimicking human judgment [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Autonomous Synthesis Platforms

| Platform Name | Core Architecture | Key Analytical Techniques | Reported Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemputer [10] | Universal robotic platform controlled by XDL language | On-line NMR, Liquid Chromatography | Multi-step synthesis of [2]rotaxanes |

| Synbot [24] | Three-layer AI/robot software/hardware | LC-MS | Optimization of organic compound synthesis |

| Modular Mobile Robot Platform [14] | Mobile robots coordinating modular instruments | Benchtop NMR, UPLC-MS | Exploratory synthesis, supramolecular chemistry, photochemical synthesis |

| A-Lab [1] | AI-driven solid-state synthesis platform | X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Synthesis of inorganic materials |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Autonomous Multi-Step Synthesis on a Modular Mobile Robot Platform

This protocol describes the procedure for conducting exploratory organic synthesis and supramolecular assembly using a platform where mobile robots coordinate standalone instruments [14].

- Step 1: Experimental Planning & Recipe Input. A domain expert defines the initial set of target reactions and the specific chemical building blocks. The heuristic decision-maker's pass/fail criteria for the subsequent NMR and MS analysis are also established at this stage and programmed into the system.

- Step 2: Automated Synthesis. The Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer prepares reaction mixtures in parallel according to the inputted recipe. It handles all dispensing of reagents and solvents into reaction vials and controls reaction conditions (temperature, stirring).

- Step 3: Sample Preparation & Transportation. Upon reaction completion, the ISynth unit automatically takes aliquots from each reaction mixture and reformats them into appropriate vials for MS and NMR analysis. A mobile robot collects these sample vials and transports them to the respective analytical instruments.

- Step 4: Orthogonal Analysis.

- UPLC-MS Analysis: The mobile robot loads the sample into the UPLC-MS. The system acquires chromatographic and mass spectrometric data.

- NMR Analysis: The robot then transports a separate aliquot to a benchtop NMR spectrometer, which acquires a 1H NMR spectrum.

- Step 5: Heuristic Decision-Making. The control software processes the acquired MS and NMR data. The pre-defined heuristic rules are applied to assign a binary "pass" or "fail" grade for each technique per reaction. A reaction must pass both analyses to be considered a "hit."

- Step 6: Autonomous Workflow Progression. Based on the decision-making outcome:

- For "pass" reactions: The system automatically proceeds to the next programmed step, which may include scale-up, further functionalization, or an autonomous function assay (e.g., testing host-guest binding properties).

- For "fail" reactions: The system may withdraw the recipe from further investigation or, in an optimization context, propose new conditions.

- Step 7: Iteration and Scale-up. The cycle (synthesis → analysis → decision) repeats autonomously. Successful intermediates from a screening phase are automatically scaled up for use in subsequent synthetic steps, enabling fully autonomous multi-step synthesis campaigns [14].

Protocol: Closed-Loop Optimization with an AI-Driven Robotic Chemist (Synbot)

This protocol outlines the workflow for the goal-specific dynamic optimization of molecular synthesis recipes using the Synbot platform [24].

- Step 1: Target and Task Definition. The user inputs the target molecule and the objective of the experiment (e.g., "maximize reaction yield").

- Step 2: AI-Driven Synthesis Planning.

- The retrosynthesis module proposes viable synthetic pathways.

- The Design of Experiments (DoE) and optimization module suggests initial reaction conditions. For known chemical spaces, a Message-Passing Neural Network (MPNN) provides informed starting points. For unfamiliar tasks, a Bayesian Optimization (BO) algorithm drives exploration.

- Step 3: Recipe Translation and Scheduling. The abstract recipe is converted into quantified action sequences and then into specific hardware control commands by the robot software layer. An online scheduling module dispatches these commands when the necessary robots and modules are available.

- Step 4: Robotic Execution and Monitoring. The robot layer executes the commands:

- The pantry and dispensing modules prepare the reaction vial.

- The reaction module carries out the synthesis under controlled conditions.

- The system periodically samples the reaction mixture (20-25 μL).

- Step 5: Automated Analysis and Feedback. Sampled solutions are transported to the sample-prep module for dilution/filtration and are then injected into an LC-MS for analysis. The conversion rate or yield is calculated and fed back to the AI's database.

- Step 6: AI Decision and Iteration. The decision-making module assesses the result. It may decide to:

- Continue the current reaction for more time.

- Withdraw the current condition and start a new one.

- Issue a "Sweep" signal to abandon the current synthetic path entirely.

- The DoE and optimization module updates its AI model and revises the recipe repository. The system then requests a new, optimized recipe, and the loop continues until the objective is satisfied [24].

Workflow Visualization and System Architecture

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core logical workflows and technical architectures of autonomous synthesis platforms.

Diagram 1: Generic Closed-Loop Autonomous Synthesis Workflow. This diagram depicts the continuous cycle of planning, execution, analysis, and learning that is fundamental to self-driving laboratories [1] [24] [14].

Diagram 2: Technical Architecture of an AI-Driven Robotic Chemist. This diagram shows the three-layer architecture (AI, Robot Software, Hardware) and the flow of information and commands between them, as exemplified by platforms like Synbot [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The operation of autonomous synthesis platforms requires both chemical and hardware components. The table below details key research reagent solutions and essential materials used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for Autonomous Synthesis

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkyne Amines [14] | Chemical Reagent | Building blocks for the synthesis of ureas and thioureas via condensation reactions. | Used in parallel synthesis for structural diversification. |

| Isothiocyanates & Isocyanates [14] | Chemical Reagent | Electrophilic partners for condensation with amines to form thiourea and urea products, respectively. | Reacted with alkyne amines to create a library of compounds. |

| Palladium Catalysts [1] | Chemical Reagent | Facilitates cross-coupling reactions, a key transformation in pharmaceutical synthesis. | Autonomously optimized in LLM-driven systems like Coscientist. |

| Chemspeed ISynth Synthesizer [14] | Automated Hardware | An automated synthesis platform for precise dispensing, reaction control, and aliquot sampling. | Core synthesis module in the mobile robot workflow. |

| Benchtop NMR Spectrometer [14] | Analytical Instrument | Provides structural information for molecular identification and reaction monitoring. | Used for orthogonal analysis alongside UPLC-MS. |

| UPLC-MS (Ultraperformance Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry) [14] | Analytical Instrument | Separates reaction mixtures (chromatography) and provides molecular weight and fragmentation data (mass spectrometry). | Primary tool for analyzing reaction outcomes and purity. |

| Mobile Robots with Multipurpose Grippers [14] | Robotic Hardware | Free-roaming agents that transport samples between different fixed modules (synthesizer, NMR, LC-MS). | Enable a flexible, modular lab architecture by linking instruments. |

Metal halide perovskite (MHP) nanocrystals (NCs) represent a highly promising class of semiconducting materials with exceptional optoelectronic properties, including near-unity photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY), narrow emission linewidths, and widely tunable bandgaps [8]. These characteristics make them ideal candidates for numerous photonic applications such as displays, solar cells, light-emitting diodes, and quantum information technologies [8]. However, fully exploiting this potential has been fundamentally challenged by the vast, complex, and high-dimensional synthesis parameter space, where traditional one-parameter-at-a-time manual experimentation techniques suffer from low throughput, batch-to-batch variation, and critical time gaps between synthesis, characterization, and decision-making [8].

To address these challenges, we present a case study of "Rainbow," a multi-robot self-driving laboratory (SDL) that autonomously navigates the mixed-variable synthesis landscape of MHP NCs [8] [25]. Rainbow integrates automated NC synthesis, real-time characterization, and machine learning (ML)-driven decision-making within a closed-loop experimentation framework [8]. This platform systematically explores critical parameters—including ligand structures and precursor conditions—to elucidate structure-property relationships and identify Pareto-optimal formulations for targeted spectral outputs, thereby accelerating the discovery and retrosynthesis of high-performance MHP NCs [8] [26].

Platform Architecture & Workflow